User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Can we get to ‘COVID zero’? Experts predict the next 8 months

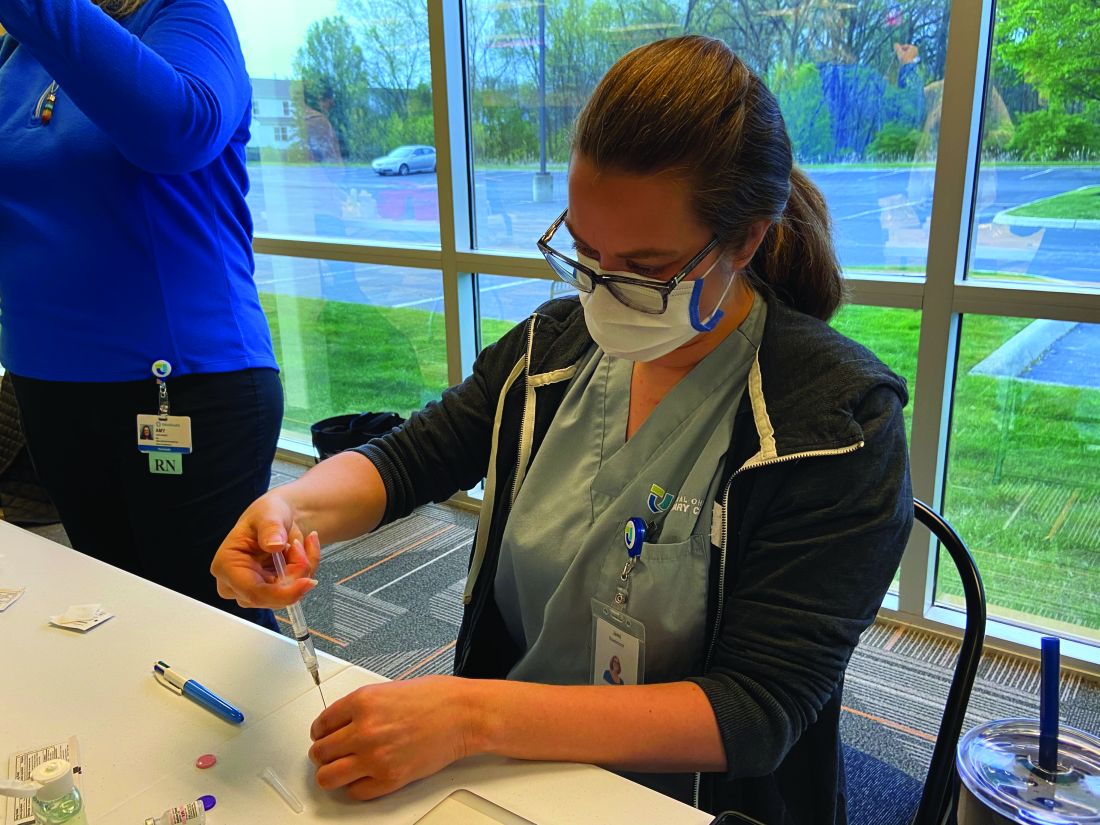

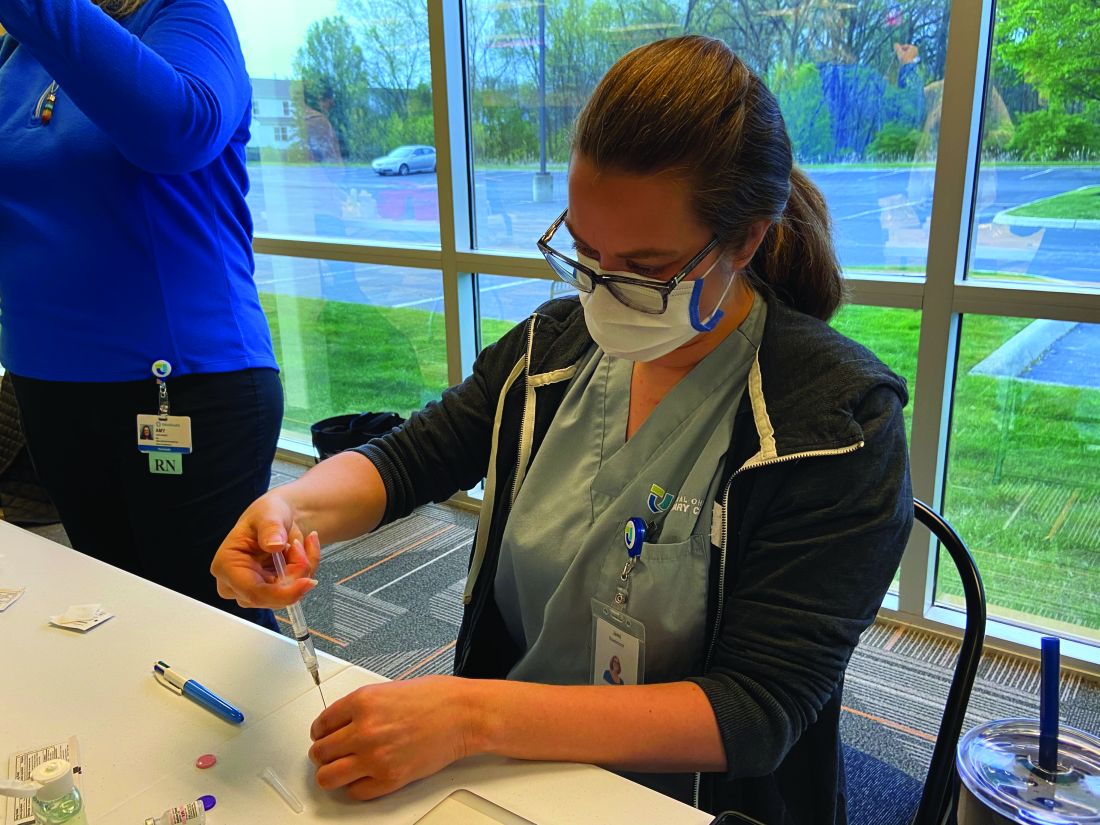

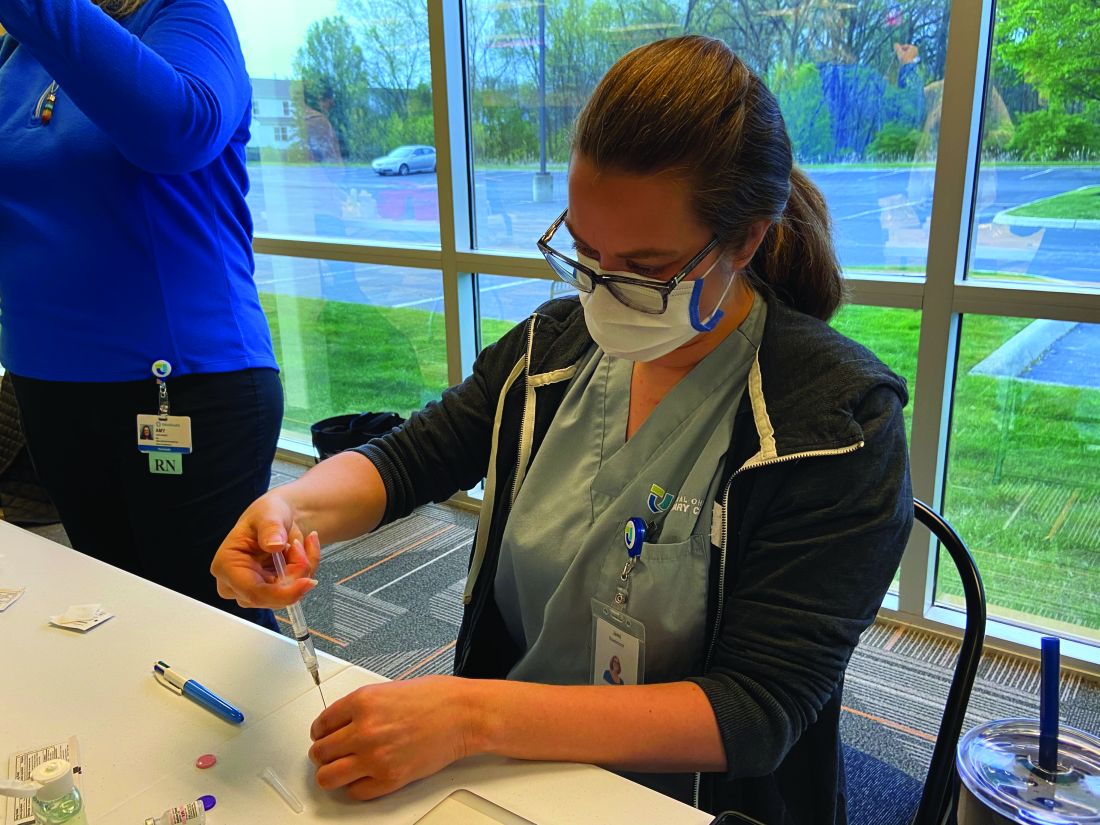

COVID-19 is likely to follow a seasonal pattern – similar to some other respiratory viruses – with fewer cases come summer 2021 followed by a jump next winter, experts predicted in a Thursday briefing.

If that pattern holds, it could mean a need to reinforce the mask-wearing message as the weather gets colder and people once again congregate indoors.

“Right now, we are projecting the United States all the way to Aug. 1 [will have] 619,000 deaths from COVID-19, with 4.7 million globally,” said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, professor of health metrics sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, during today’s media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and IHME.

The encouraging news is the vaccines appear to be working, and more Americans are getting them. “If you look at the data for these vaccines, they are extremely safe, they are extremely efficacious, and they make you basically impervious – for the most part – to getting serious disease, hospitalization, or death,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

“These vaccines do what they were meant to do: defang this virus,” said Dr. Adalja, who is an IDSA Fellow and adjunct assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Emerging data out of Israel and other countries suggest a vaccinated person is less likely to transmit the virus as well, he added.

Still aiming for herd immunity

Furthermore, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is likely to approve emergency use authorization (EUA) among teenagers 12-15 years old “imminently,” thereby expanding the pool of people potentially protected by vaccines.

Such authorization could help with overall public health efforts. “That’s simply a mathematical formula,” Dr. Adalja said. “The more people that are vaccinated, including children, the quicker we’ll get to herd immunity.”

In addition, with lower case numbers expected this summer, herd immunity might become more achievable, said Dr. Mokdad, who is also chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington.

As important as herd immunity is, so-called decoupling is “more important to me,” Dr. Adalja said. Decoupling refers to separating infections from the more severe outcomes, so people who get COVID-19 are less likely to need hospitalization or die from it.

Vaccines get the credit here, he added, including with the variants. “Even if you get a breakthrough infection with a variant, it’s not likely to land you in the hospital or cause serious disease or death,” Dr. Adalja said.

Masks and the uncommon cold

Wearing a mask until we reach herd immunity is important because it’s not possible to tell who is vaccinated and who isn’t, Dr. Mokdad said. “Remember, as many people are waiting to get a vaccine, all of us have access to a mask,” he said.

Dr. Adalja agreed, adding that public health guidance on masks will likely stay in place until we cross that herd immunity threshold and community circulation of the virus goes down.

“People are probably going to want to continue wearing masks, at least some proportion, because they see the benefit for other respiratory viruses,” Dr. Adalja said. “How many of you had a common cold this year?”

Variants: Some good news?

Experts are monitoring the spread of variants of concern in the United States and abroad. On a positive note, the B.1.1.7 variant first identified in the United Kingdom appears to be dominant in the United States at this time, which is potentially good for two reasons. One is that the available COVID-19 vaccines show sufficient efficacy against the strain, Dr. Mokdad said.

Second, a predominance of B.1.1.7 makes it more difficult for other emerging variants of concern like P1 [Brazil] or B.1.351 [South Africa] to gain control, Dr. Adalja said.

“B.1.1.7 is such an efficient transmitter,” he said. “That’s kind of an advantage … because the more B.1.1.7, you have the less opportunity B.1.351 and P1 have to set up shop.”

Hesitancy from misinformation

Vaccine hesitancy remains a concern, particularly at a time when some predict a drop in the number of Americans seeking vaccination. Although needle phobia plays a role in dissuading some from vaccination, the bigger issue is vaccine misinformation, Dr. Adalja said.

“Some people are just terrified when they see the needle. That’s a small part of the proportion of people who don’t want to get vaccinated,” Dr. Adalja said. In contrast, he attributed most hesitancy to misinformation about the vaccine, including reports that the vaccines are fake.

Even celebrities are getting drawn into the misinformation.

“I just had to answer something about Mariah Carey’s vaccination,” he said. Someone believed “that it was done with a retractable needle that didn’t really go into her arm.”

Vaccine hesitancy is more about people not understanding the risk-benefit analysis, taking side effects out of out of context if there are side effects, or being influenced by “arbitrary statements about microchips, infertility, or whatever it might be,” Dr. Adalja said.

The future is subject to change

“We’re expecting another rise in cases and more mortality in our winter season here in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said, adding that the efficacy of the vaccines is likely to attenuate the mortality rate in particular.

However, as the epidemiology of the pandemic evolves, so too will the long-term predictions. Factors that could influence future numbers include the expansion of vaccination to teens 12-15 years old and (eventually) younger children, a need for booster vaccines, emerging variants, and the changing proportion of the population who are fully vaccinated or were previously infected.

Again, getting people to adhere to mask wearing come winter could be challenging if the scenario over the summer is “close to normal with less than 200 deaths a day in the United States,” he added. Asking people to wear masks again will be like “swimming upstream.”

“I think it’s a mistake to think that we’re going to get to ‘COVID zero,’ ” Dr. Adalja said. “This is not an eradicable disease. There’s only been one human infectious disease eradicated from the planet, and that’s smallpox, and it had very different characteristics.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 is likely to follow a seasonal pattern – similar to some other respiratory viruses – with fewer cases come summer 2021 followed by a jump next winter, experts predicted in a Thursday briefing.

If that pattern holds, it could mean a need to reinforce the mask-wearing message as the weather gets colder and people once again congregate indoors.

“Right now, we are projecting the United States all the way to Aug. 1 [will have] 619,000 deaths from COVID-19, with 4.7 million globally,” said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, professor of health metrics sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, during today’s media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and IHME.

The encouraging news is the vaccines appear to be working, and more Americans are getting them. “If you look at the data for these vaccines, they are extremely safe, they are extremely efficacious, and they make you basically impervious – for the most part – to getting serious disease, hospitalization, or death,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

“These vaccines do what they were meant to do: defang this virus,” said Dr. Adalja, who is an IDSA Fellow and adjunct assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Emerging data out of Israel and other countries suggest a vaccinated person is less likely to transmit the virus as well, he added.

Still aiming for herd immunity

Furthermore, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is likely to approve emergency use authorization (EUA) among teenagers 12-15 years old “imminently,” thereby expanding the pool of people potentially protected by vaccines.

Such authorization could help with overall public health efforts. “That’s simply a mathematical formula,” Dr. Adalja said. “The more people that are vaccinated, including children, the quicker we’ll get to herd immunity.”

In addition, with lower case numbers expected this summer, herd immunity might become more achievable, said Dr. Mokdad, who is also chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington.

As important as herd immunity is, so-called decoupling is “more important to me,” Dr. Adalja said. Decoupling refers to separating infections from the more severe outcomes, so people who get COVID-19 are less likely to need hospitalization or die from it.

Vaccines get the credit here, he added, including with the variants. “Even if you get a breakthrough infection with a variant, it’s not likely to land you in the hospital or cause serious disease or death,” Dr. Adalja said.

Masks and the uncommon cold

Wearing a mask until we reach herd immunity is important because it’s not possible to tell who is vaccinated and who isn’t, Dr. Mokdad said. “Remember, as many people are waiting to get a vaccine, all of us have access to a mask,” he said.

Dr. Adalja agreed, adding that public health guidance on masks will likely stay in place until we cross that herd immunity threshold and community circulation of the virus goes down.

“People are probably going to want to continue wearing masks, at least some proportion, because they see the benefit for other respiratory viruses,” Dr. Adalja said. “How many of you had a common cold this year?”

Variants: Some good news?

Experts are monitoring the spread of variants of concern in the United States and abroad. On a positive note, the B.1.1.7 variant first identified in the United Kingdom appears to be dominant in the United States at this time, which is potentially good for two reasons. One is that the available COVID-19 vaccines show sufficient efficacy against the strain, Dr. Mokdad said.

Second, a predominance of B.1.1.7 makes it more difficult for other emerging variants of concern like P1 [Brazil] or B.1.351 [South Africa] to gain control, Dr. Adalja said.

“B.1.1.7 is such an efficient transmitter,” he said. “That’s kind of an advantage … because the more B.1.1.7, you have the less opportunity B.1.351 and P1 have to set up shop.”

Hesitancy from misinformation

Vaccine hesitancy remains a concern, particularly at a time when some predict a drop in the number of Americans seeking vaccination. Although needle phobia plays a role in dissuading some from vaccination, the bigger issue is vaccine misinformation, Dr. Adalja said.

“Some people are just terrified when they see the needle. That’s a small part of the proportion of people who don’t want to get vaccinated,” Dr. Adalja said. In contrast, he attributed most hesitancy to misinformation about the vaccine, including reports that the vaccines are fake.

Even celebrities are getting drawn into the misinformation.

“I just had to answer something about Mariah Carey’s vaccination,” he said. Someone believed “that it was done with a retractable needle that didn’t really go into her arm.”

Vaccine hesitancy is more about people not understanding the risk-benefit analysis, taking side effects out of out of context if there are side effects, or being influenced by “arbitrary statements about microchips, infertility, or whatever it might be,” Dr. Adalja said.

The future is subject to change

“We’re expecting another rise in cases and more mortality in our winter season here in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said, adding that the efficacy of the vaccines is likely to attenuate the mortality rate in particular.

However, as the epidemiology of the pandemic evolves, so too will the long-term predictions. Factors that could influence future numbers include the expansion of vaccination to teens 12-15 years old and (eventually) younger children, a need for booster vaccines, emerging variants, and the changing proportion of the population who are fully vaccinated or were previously infected.

Again, getting people to adhere to mask wearing come winter could be challenging if the scenario over the summer is “close to normal with less than 200 deaths a day in the United States,” he added. Asking people to wear masks again will be like “swimming upstream.”

“I think it’s a mistake to think that we’re going to get to ‘COVID zero,’ ” Dr. Adalja said. “This is not an eradicable disease. There’s only been one human infectious disease eradicated from the planet, and that’s smallpox, and it had very different characteristics.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 is likely to follow a seasonal pattern – similar to some other respiratory viruses – with fewer cases come summer 2021 followed by a jump next winter, experts predicted in a Thursday briefing.

If that pattern holds, it could mean a need to reinforce the mask-wearing message as the weather gets colder and people once again congregate indoors.

“Right now, we are projecting the United States all the way to Aug. 1 [will have] 619,000 deaths from COVID-19, with 4.7 million globally,” said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, professor of health metrics sciences at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, during today’s media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and IHME.

The encouraging news is the vaccines appear to be working, and more Americans are getting them. “If you look at the data for these vaccines, they are extremely safe, they are extremely efficacious, and they make you basically impervious – for the most part – to getting serious disease, hospitalization, or death,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

“These vaccines do what they were meant to do: defang this virus,” said Dr. Adalja, who is an IDSA Fellow and adjunct assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Emerging data out of Israel and other countries suggest a vaccinated person is less likely to transmit the virus as well, he added.

Still aiming for herd immunity

Furthermore, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is likely to approve emergency use authorization (EUA) among teenagers 12-15 years old “imminently,” thereby expanding the pool of people potentially protected by vaccines.

Such authorization could help with overall public health efforts. “That’s simply a mathematical formula,” Dr. Adalja said. “The more people that are vaccinated, including children, the quicker we’ll get to herd immunity.”

In addition, with lower case numbers expected this summer, herd immunity might become more achievable, said Dr. Mokdad, who is also chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington.

As important as herd immunity is, so-called decoupling is “more important to me,” Dr. Adalja said. Decoupling refers to separating infections from the more severe outcomes, so people who get COVID-19 are less likely to need hospitalization or die from it.

Vaccines get the credit here, he added, including with the variants. “Even if you get a breakthrough infection with a variant, it’s not likely to land you in the hospital or cause serious disease or death,” Dr. Adalja said.

Masks and the uncommon cold

Wearing a mask until we reach herd immunity is important because it’s not possible to tell who is vaccinated and who isn’t, Dr. Mokdad said. “Remember, as many people are waiting to get a vaccine, all of us have access to a mask,” he said.

Dr. Adalja agreed, adding that public health guidance on masks will likely stay in place until we cross that herd immunity threshold and community circulation of the virus goes down.

“People are probably going to want to continue wearing masks, at least some proportion, because they see the benefit for other respiratory viruses,” Dr. Adalja said. “How many of you had a common cold this year?”

Variants: Some good news?

Experts are monitoring the spread of variants of concern in the United States and abroad. On a positive note, the B.1.1.7 variant first identified in the United Kingdom appears to be dominant in the United States at this time, which is potentially good for two reasons. One is that the available COVID-19 vaccines show sufficient efficacy against the strain, Dr. Mokdad said.

Second, a predominance of B.1.1.7 makes it more difficult for other emerging variants of concern like P1 [Brazil] or B.1.351 [South Africa] to gain control, Dr. Adalja said.

“B.1.1.7 is such an efficient transmitter,” he said. “That’s kind of an advantage … because the more B.1.1.7, you have the less opportunity B.1.351 and P1 have to set up shop.”

Hesitancy from misinformation

Vaccine hesitancy remains a concern, particularly at a time when some predict a drop in the number of Americans seeking vaccination. Although needle phobia plays a role in dissuading some from vaccination, the bigger issue is vaccine misinformation, Dr. Adalja said.

“Some people are just terrified when they see the needle. That’s a small part of the proportion of people who don’t want to get vaccinated,” Dr. Adalja said. In contrast, he attributed most hesitancy to misinformation about the vaccine, including reports that the vaccines are fake.

Even celebrities are getting drawn into the misinformation.

“I just had to answer something about Mariah Carey’s vaccination,” he said. Someone believed “that it was done with a retractable needle that didn’t really go into her arm.”

Vaccine hesitancy is more about people not understanding the risk-benefit analysis, taking side effects out of out of context if there are side effects, or being influenced by “arbitrary statements about microchips, infertility, or whatever it might be,” Dr. Adalja said.

The future is subject to change

“We’re expecting another rise in cases and more mortality in our winter season here in the United States,” Dr. Mokdad said, adding that the efficacy of the vaccines is likely to attenuate the mortality rate in particular.

However, as the epidemiology of the pandemic evolves, so too will the long-term predictions. Factors that could influence future numbers include the expansion of vaccination to teens 12-15 years old and (eventually) younger children, a need for booster vaccines, emerging variants, and the changing proportion of the population who are fully vaccinated or were previously infected.

Again, getting people to adhere to mask wearing come winter could be challenging if the scenario over the summer is “close to normal with less than 200 deaths a day in the United States,” he added. Asking people to wear masks again will be like “swimming upstream.”

“I think it’s a mistake to think that we’re going to get to ‘COVID zero,’ ” Dr. Adalja said. “This is not an eradicable disease. There’s only been one human infectious disease eradicated from the planet, and that’s smallpox, and it had very different characteristics.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Percentage of doctors who are Black barely changed in 120 years

according to a new study.

In 1900, 1.3% of physicians were Black. In 1940, 2.8% of physicians were Black, and by 2018 – when almost 13% of the population was Black – 5.4% of doctors were Black, reports Dan Ly, MD, PhD, MPP, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a study published online April 19, 2021, in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

The proportion of male Black physicians was 2.7% in 1940 and 2.6% in 2018.

Dr. Ly also found a significant wage gap. The median income earned by White doctors was $50,000 more than the median income of Black physicians in 2018. Dr. Ly based his findings on the U.S. Census Decennial Census long form, accessed via IPUMS, a free database funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations.

“If we care about the health of the population, particularly the health of Black patients, we should care about how small the proportion of our physicians who are Black is and the extremely slow progress we have made as a medical system in increasing that proportion,” Dr. Ly said in an interview.

Dr. Ly said he took on this research in part because previous studies have shown that Black patients are more likely to seek preventive care from Black doctors. Thus, increasing the numbers of Black physicians could narrow gaps in life expectancy between Whites and Blacks.

He also wanted to see whether progress had been made as a result of various medical organizations and the Association of American Medical Colleges undertaking initiatives to increase workforce diversity. There has been “very, very little” progress, he said.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, the AAMC’s senior director of workforce diversity, said Dr. Ly’s report “was not surprising at all.”

The AAMC reported in 2014 that the number of Black men who apply to and matriculate into medical schools has been declining since 1978. That year, there were 1,410 Black male applicants and 542 Black enrollees. In 2014, there were 1,337 applicants and 515 enrollees.

Since 2014, Black male enrollment has increased slightly, rising from 2.4% in the 2014-2015 school year to 2.9% in the 2019-2020 year, the AAMC reported last year.

In addition, among other historically underrepresented minorities, “we really have seen very small progress” despite the increase in the number of medical schools, Dr. Poll-Hunter said in an interview.

The AAMC and the National Medical Association consider the lack of Black male applicants and matriculants to be a national crisis. The two groups started an alliance in 2020 aimed at finding ways to amplify and support Black men’s interest in medicine and the biomedical sciences and to “develop systems-based solutions to address exclusionary practices that create barriers for Black men and prevent them from having equitable opportunities to successfully enroll in medical school.”

Solutions include requiring medical school admissions committees and application screeners to undergo implicit bias awareness and mitigation training, adopting holistic admissions reviews, and incentivizing institutions of higher learning to partner with Black communities in urban and rural school systems to establish K-12 health sciences academies, said NMA President Leon McDougle, MD, MPH.

“There are the systems factors, and racism is a big one that we have to tackle,” said Dr. Poll-Hunter.

Diversity isn’t just about numbers, said Dr. McDougle, a professor of family medicine and associate dean for diversity and inclusion at Ohio State University, Columbus. “We know that medical school graduates who are African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native are more likely to serve those communities as practicing physicians.

“The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for more African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native physicians,” he said. “Inadequate access to culturally competent care has exacerbated existing health disparities, resulting in death and hospitalization rates up to three to four times the rates of European American or White people.”

Dr. Poll-Hunter also said that studies have shown that diversity in the classroom creates a more enriched learning environment and increases civic mindedness and cognitive complexity, “as well as helps us understand people who are different than ourselves.”

The diversity goal “is not about quotas, it’s about excellence,” she said. “We know that there’s talent that exists, and we want to make sure that everyone has an opportunity to be successful.”

Dr. Ly has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study.

In 1900, 1.3% of physicians were Black. In 1940, 2.8% of physicians were Black, and by 2018 – when almost 13% of the population was Black – 5.4% of doctors were Black, reports Dan Ly, MD, PhD, MPP, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a study published online April 19, 2021, in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

The proportion of male Black physicians was 2.7% in 1940 and 2.6% in 2018.

Dr. Ly also found a significant wage gap. The median income earned by White doctors was $50,000 more than the median income of Black physicians in 2018. Dr. Ly based his findings on the U.S. Census Decennial Census long form, accessed via IPUMS, a free database funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations.

“If we care about the health of the population, particularly the health of Black patients, we should care about how small the proportion of our physicians who are Black is and the extremely slow progress we have made as a medical system in increasing that proportion,” Dr. Ly said in an interview.

Dr. Ly said he took on this research in part because previous studies have shown that Black patients are more likely to seek preventive care from Black doctors. Thus, increasing the numbers of Black physicians could narrow gaps in life expectancy between Whites and Blacks.

He also wanted to see whether progress had been made as a result of various medical organizations and the Association of American Medical Colleges undertaking initiatives to increase workforce diversity. There has been “very, very little” progress, he said.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, the AAMC’s senior director of workforce diversity, said Dr. Ly’s report “was not surprising at all.”

The AAMC reported in 2014 that the number of Black men who apply to and matriculate into medical schools has been declining since 1978. That year, there were 1,410 Black male applicants and 542 Black enrollees. In 2014, there were 1,337 applicants and 515 enrollees.

Since 2014, Black male enrollment has increased slightly, rising from 2.4% in the 2014-2015 school year to 2.9% in the 2019-2020 year, the AAMC reported last year.

In addition, among other historically underrepresented minorities, “we really have seen very small progress” despite the increase in the number of medical schools, Dr. Poll-Hunter said in an interview.

The AAMC and the National Medical Association consider the lack of Black male applicants and matriculants to be a national crisis. The two groups started an alliance in 2020 aimed at finding ways to amplify and support Black men’s interest in medicine and the biomedical sciences and to “develop systems-based solutions to address exclusionary practices that create barriers for Black men and prevent them from having equitable opportunities to successfully enroll in medical school.”

Solutions include requiring medical school admissions committees and application screeners to undergo implicit bias awareness and mitigation training, adopting holistic admissions reviews, and incentivizing institutions of higher learning to partner with Black communities in urban and rural school systems to establish K-12 health sciences academies, said NMA President Leon McDougle, MD, MPH.

“There are the systems factors, and racism is a big one that we have to tackle,” said Dr. Poll-Hunter.

Diversity isn’t just about numbers, said Dr. McDougle, a professor of family medicine and associate dean for diversity and inclusion at Ohio State University, Columbus. “We know that medical school graduates who are African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native are more likely to serve those communities as practicing physicians.

“The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for more African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native physicians,” he said. “Inadequate access to culturally competent care has exacerbated existing health disparities, resulting in death and hospitalization rates up to three to four times the rates of European American or White people.”

Dr. Poll-Hunter also said that studies have shown that diversity in the classroom creates a more enriched learning environment and increases civic mindedness and cognitive complexity, “as well as helps us understand people who are different than ourselves.”

The diversity goal “is not about quotas, it’s about excellence,” she said. “We know that there’s talent that exists, and we want to make sure that everyone has an opportunity to be successful.”

Dr. Ly has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study.

In 1900, 1.3% of physicians were Black. In 1940, 2.8% of physicians were Black, and by 2018 – when almost 13% of the population was Black – 5.4% of doctors were Black, reports Dan Ly, MD, PhD, MPP, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a study published online April 19, 2021, in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

The proportion of male Black physicians was 2.7% in 1940 and 2.6% in 2018.

Dr. Ly also found a significant wage gap. The median income earned by White doctors was $50,000 more than the median income of Black physicians in 2018. Dr. Ly based his findings on the U.S. Census Decennial Census long form, accessed via IPUMS, a free database funded by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations.

“If we care about the health of the population, particularly the health of Black patients, we should care about how small the proportion of our physicians who are Black is and the extremely slow progress we have made as a medical system in increasing that proportion,” Dr. Ly said in an interview.

Dr. Ly said he took on this research in part because previous studies have shown that Black patients are more likely to seek preventive care from Black doctors. Thus, increasing the numbers of Black physicians could narrow gaps in life expectancy between Whites and Blacks.

He also wanted to see whether progress had been made as a result of various medical organizations and the Association of American Medical Colleges undertaking initiatives to increase workforce diversity. There has been “very, very little” progress, he said.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, the AAMC’s senior director of workforce diversity, said Dr. Ly’s report “was not surprising at all.”

The AAMC reported in 2014 that the number of Black men who apply to and matriculate into medical schools has been declining since 1978. That year, there were 1,410 Black male applicants and 542 Black enrollees. In 2014, there were 1,337 applicants and 515 enrollees.

Since 2014, Black male enrollment has increased slightly, rising from 2.4% in the 2014-2015 school year to 2.9% in the 2019-2020 year, the AAMC reported last year.

In addition, among other historically underrepresented minorities, “we really have seen very small progress” despite the increase in the number of medical schools, Dr. Poll-Hunter said in an interview.

The AAMC and the National Medical Association consider the lack of Black male applicants and matriculants to be a national crisis. The two groups started an alliance in 2020 aimed at finding ways to amplify and support Black men’s interest in medicine and the biomedical sciences and to “develop systems-based solutions to address exclusionary practices that create barriers for Black men and prevent them from having equitable opportunities to successfully enroll in medical school.”

Solutions include requiring medical school admissions committees and application screeners to undergo implicit bias awareness and mitigation training, adopting holistic admissions reviews, and incentivizing institutions of higher learning to partner with Black communities in urban and rural school systems to establish K-12 health sciences academies, said NMA President Leon McDougle, MD, MPH.

“There are the systems factors, and racism is a big one that we have to tackle,” said Dr. Poll-Hunter.

Diversity isn’t just about numbers, said Dr. McDougle, a professor of family medicine and associate dean for diversity and inclusion at Ohio State University, Columbus. “We know that medical school graduates who are African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native are more likely to serve those communities as practicing physicians.

“The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for more African American or Black, Hispanic or Latinx, or American Indian or Alaskan Native physicians,” he said. “Inadequate access to culturally competent care has exacerbated existing health disparities, resulting in death and hospitalization rates up to three to four times the rates of European American or White people.”

Dr. Poll-Hunter also said that studies have shown that diversity in the classroom creates a more enriched learning environment and increases civic mindedness and cognitive complexity, “as well as helps us understand people who are different than ourselves.”

The diversity goal “is not about quotas, it’s about excellence,” she said. “We know that there’s talent that exists, and we want to make sure that everyone has an opportunity to be successful.”

Dr. Ly has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 infection conveys imperfect immunity in young adults

Do your patients think that getting COVID-19 is fully protective against subsequent reinfection? Tell it to the Marines.

A study of U.S. Marine recruits on their way to boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., showed that those who were seropositive at baseline, indicating prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2, remained at some risk for reinfection. They had about one-fifth the risk of subsequent infection, compared with seronegative recruits during basic training, but reinfections did occur.

The study, by Stuart C. Sealfon, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

“Although antibodies induced by initial infection are largely protective, they do not guarantee effective SARS-CoV-2 neutralization activity or immunity against subsequent infection,” they wrote.

An infectious disease specialist who was not involved in the study said that the findings provide further evidence about the level of immunity acquired after an infection.

“It’s quite clear that reinfections do occur, they are of public health importance, and they’re something we need to be mindful of in terms of advising patients about whether a prior infection protects them from reinfection,” Mark Siedner, MD, MPH, a clinician and researcher in the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study results reinforce that “not all antibodies are the same,” said Sachin Gupta, MD, an attending physician in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “We’re seeing still that 10% of folks who have antibodies can get infected again,” he said in an interview.

CHARM initiative

Dr. Sealfon and colleagues presented an analysis of data from the ironically named CHARM (COVID-19 Health Action Response for Marines) prospective study.

CHARM included U.S. Marine recruits, most of them male, aged 18-20 years, who were instructed to follow a 2-week unsupervised quarantine at home, after which they reported to a Marine-supervised facility for an additional 2-week quarantine.

At baseline, participants were tested for SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) seropositivity, defined as a dilution of 1:150 or more on receptor-binding domain and full-length spike protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

The recruits filled out questionnaires asking them to report any of 14 specific COVID-19–related symptoms or any other unspecified symptom, as well as demographic information, risk factors, and a brief medical history.

Investigators tested recruits for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay at weeks 0, 1, and 2 of quarantine, and any who had positive PCR results during quarantine were excluded.

Participants who had three negative swab PCR results during quarantine and a baseline serology test at the beginning of the supervised quarantine period – either seronegative or seropositive – then went on to enjoy their basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, S.C.

The participants were followed prospectively with PCR tests at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in both the seropositive and seronegative groups, and sera were obtained at the same time.

Holes in immunologic armor

Full data were available for a total of 189 participants who were seropositive and 2,247 who were seronegative at enrollment.

In all, 19 of 189 seropositive recruits (10%) had at least one PCR test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection during the 6-week follow-up period. This translated into an incidence of 1.1 cases per person-year.

Of the 2,247 participants seronegative at baseline, 1,079 tested positive (6.2 cases per person-year; incidence rate ratio 0.18).

It appeared that antibodies provided some protection for seropositive recruits, as evidenced by a higher likelihood of infection among those with lower baseline full-length spike protein IgG titers than in those with higher baseline titers (hazard ratio 0.4, P < .001).

Among the seropositive participants who did acquire a second SARS-CoV-2 infection, viral loads in mid-turbinate nasal swabs were about 10-fold lower than in seronegative recruits who acquired infections during follow-up.

“This finding suggests that some reinfected individuals could have a similar capacity to transmit infection as those who are infected for the first time. The rate at which reinfection occurs after vaccines and natural immunity is important for estimating the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to suppress the pandemic,” the investigators wrote.

Baseline neutralizing antibody titers were detected in 45 of the first 54 seropositive recruits who remained PCR negative throughout follow-up, but also in 6 of 19 seropositive participants who became infected during the 6 weeks of observation.

Lessons

Both Dr. Siedner and Dr. Gupta agreed with the authors that the risks for reinfection that were observed in young, physically fit people may differ for other populations, such as women (only 10% of seropositive recruits and 8% of seronegative recruits were female), older patients, or those who are immunocompromised.

Given that the adjusted odds ratio for reinfection in this study was nearly identical to that of a recent British study comparing infection rates between seropositive and seronegative health care workers, the risk of reinfection for other young adults and for the general population may be similar, Dr. Sealfon and colleagues wrote.

Adding to the challenge of reaching herd immunity is the observation that some patients who have recovered from COVID-19 are skeptical about the need for further protection.

“There are patients who feel like vaccination is of low benefit to them, and I think these are the same people who would be hesitant to get the vaccine anyway,” Dr. Gupta said.

Although no vaccine is perfect – the vaccine failure rate from the mRNA-based vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer/Biontech is about 5% – the protections they afford are unmistakable, Dr. Siedner said.

“I think it’s important to make the distinction that most postvaccination infections by and large have been very mild,” he said. “In people with normal immune systems, we have not seen an onslaught of postvaccination infections requiring hospitalization. Even if people do get infected after vaccination, the vaccines protect people from severe infection, and that’s what we want them to do.”

The investigators stated, “Young adults, of whom a high proportion are asymptomatically infected and become seropositive in the absence of known infection, can be an important source of transmission to more vulnerable populations. Evaluating the protection against subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by seropositivity in young adults is important for determining the need for vaccinating previously infected individuals in this age group.”

The study was funded by the Defense Health Agency and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Dr. Sealfon, Dr. Siedner, and Dr. Gupta have no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Gupta is a member of the editorial advisory board for this publication.

Do your patients think that getting COVID-19 is fully protective against subsequent reinfection? Tell it to the Marines.

A study of U.S. Marine recruits on their way to boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., showed that those who were seropositive at baseline, indicating prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2, remained at some risk for reinfection. They had about one-fifth the risk of subsequent infection, compared with seronegative recruits during basic training, but reinfections did occur.

The study, by Stuart C. Sealfon, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

“Although antibodies induced by initial infection are largely protective, they do not guarantee effective SARS-CoV-2 neutralization activity or immunity against subsequent infection,” they wrote.

An infectious disease specialist who was not involved in the study said that the findings provide further evidence about the level of immunity acquired after an infection.

“It’s quite clear that reinfections do occur, they are of public health importance, and they’re something we need to be mindful of in terms of advising patients about whether a prior infection protects them from reinfection,” Mark Siedner, MD, MPH, a clinician and researcher in the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study results reinforce that “not all antibodies are the same,” said Sachin Gupta, MD, an attending physician in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “We’re seeing still that 10% of folks who have antibodies can get infected again,” he said in an interview.

CHARM initiative

Dr. Sealfon and colleagues presented an analysis of data from the ironically named CHARM (COVID-19 Health Action Response for Marines) prospective study.

CHARM included U.S. Marine recruits, most of them male, aged 18-20 years, who were instructed to follow a 2-week unsupervised quarantine at home, after which they reported to a Marine-supervised facility for an additional 2-week quarantine.

At baseline, participants were tested for SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) seropositivity, defined as a dilution of 1:150 or more on receptor-binding domain and full-length spike protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

The recruits filled out questionnaires asking them to report any of 14 specific COVID-19–related symptoms or any other unspecified symptom, as well as demographic information, risk factors, and a brief medical history.

Investigators tested recruits for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay at weeks 0, 1, and 2 of quarantine, and any who had positive PCR results during quarantine were excluded.

Participants who had three negative swab PCR results during quarantine and a baseline serology test at the beginning of the supervised quarantine period – either seronegative or seropositive – then went on to enjoy their basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, S.C.

The participants were followed prospectively with PCR tests at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in both the seropositive and seronegative groups, and sera were obtained at the same time.

Holes in immunologic armor

Full data were available for a total of 189 participants who were seropositive and 2,247 who were seronegative at enrollment.

In all, 19 of 189 seropositive recruits (10%) had at least one PCR test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection during the 6-week follow-up period. This translated into an incidence of 1.1 cases per person-year.

Of the 2,247 participants seronegative at baseline, 1,079 tested positive (6.2 cases per person-year; incidence rate ratio 0.18).

It appeared that antibodies provided some protection for seropositive recruits, as evidenced by a higher likelihood of infection among those with lower baseline full-length spike protein IgG titers than in those with higher baseline titers (hazard ratio 0.4, P < .001).

Among the seropositive participants who did acquire a second SARS-CoV-2 infection, viral loads in mid-turbinate nasal swabs were about 10-fold lower than in seronegative recruits who acquired infections during follow-up.

“This finding suggests that some reinfected individuals could have a similar capacity to transmit infection as those who are infected for the first time. The rate at which reinfection occurs after vaccines and natural immunity is important for estimating the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to suppress the pandemic,” the investigators wrote.

Baseline neutralizing antibody titers were detected in 45 of the first 54 seropositive recruits who remained PCR negative throughout follow-up, but also in 6 of 19 seropositive participants who became infected during the 6 weeks of observation.

Lessons

Both Dr. Siedner and Dr. Gupta agreed with the authors that the risks for reinfection that were observed in young, physically fit people may differ for other populations, such as women (only 10% of seropositive recruits and 8% of seronegative recruits were female), older patients, or those who are immunocompromised.

Given that the adjusted odds ratio for reinfection in this study was nearly identical to that of a recent British study comparing infection rates between seropositive and seronegative health care workers, the risk of reinfection for other young adults and for the general population may be similar, Dr. Sealfon and colleagues wrote.

Adding to the challenge of reaching herd immunity is the observation that some patients who have recovered from COVID-19 are skeptical about the need for further protection.

“There are patients who feel like vaccination is of low benefit to them, and I think these are the same people who would be hesitant to get the vaccine anyway,” Dr. Gupta said.

Although no vaccine is perfect – the vaccine failure rate from the mRNA-based vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer/Biontech is about 5% – the protections they afford are unmistakable, Dr. Siedner said.

“I think it’s important to make the distinction that most postvaccination infections by and large have been very mild,” he said. “In people with normal immune systems, we have not seen an onslaught of postvaccination infections requiring hospitalization. Even if people do get infected after vaccination, the vaccines protect people from severe infection, and that’s what we want them to do.”

The investigators stated, “Young adults, of whom a high proportion are asymptomatically infected and become seropositive in the absence of known infection, can be an important source of transmission to more vulnerable populations. Evaluating the protection against subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by seropositivity in young adults is important for determining the need for vaccinating previously infected individuals in this age group.”

The study was funded by the Defense Health Agency and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Dr. Sealfon, Dr. Siedner, and Dr. Gupta have no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Gupta is a member of the editorial advisory board for this publication.

Do your patients think that getting COVID-19 is fully protective against subsequent reinfection? Tell it to the Marines.

A study of U.S. Marine recruits on their way to boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., showed that those who were seropositive at baseline, indicating prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2, remained at some risk for reinfection. They had about one-fifth the risk of subsequent infection, compared with seronegative recruits during basic training, but reinfections did occur.

The study, by Stuart C. Sealfon, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and colleagues, was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

“Although antibodies induced by initial infection are largely protective, they do not guarantee effective SARS-CoV-2 neutralization activity or immunity against subsequent infection,” they wrote.

An infectious disease specialist who was not involved in the study said that the findings provide further evidence about the level of immunity acquired after an infection.

“It’s quite clear that reinfections do occur, they are of public health importance, and they’re something we need to be mindful of in terms of advising patients about whether a prior infection protects them from reinfection,” Mark Siedner, MD, MPH, a clinician and researcher in the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study results reinforce that “not all antibodies are the same,” said Sachin Gupta, MD, an attending physician in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “We’re seeing still that 10% of folks who have antibodies can get infected again,” he said in an interview.

CHARM initiative

Dr. Sealfon and colleagues presented an analysis of data from the ironically named CHARM (COVID-19 Health Action Response for Marines) prospective study.

CHARM included U.S. Marine recruits, most of them male, aged 18-20 years, who were instructed to follow a 2-week unsupervised quarantine at home, after which they reported to a Marine-supervised facility for an additional 2-week quarantine.

At baseline, participants were tested for SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) seropositivity, defined as a dilution of 1:150 or more on receptor-binding domain and full-length spike protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

The recruits filled out questionnaires asking them to report any of 14 specific COVID-19–related symptoms or any other unspecified symptom, as well as demographic information, risk factors, and a brief medical history.

Investigators tested recruits for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay at weeks 0, 1, and 2 of quarantine, and any who had positive PCR results during quarantine were excluded.

Participants who had three negative swab PCR results during quarantine and a baseline serology test at the beginning of the supervised quarantine period – either seronegative or seropositive – then went on to enjoy their basic training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, S.C.

The participants were followed prospectively with PCR tests at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in both the seropositive and seronegative groups, and sera were obtained at the same time.

Holes in immunologic armor

Full data were available for a total of 189 participants who were seropositive and 2,247 who were seronegative at enrollment.

In all, 19 of 189 seropositive recruits (10%) had at least one PCR test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection during the 6-week follow-up period. This translated into an incidence of 1.1 cases per person-year.

Of the 2,247 participants seronegative at baseline, 1,079 tested positive (6.2 cases per person-year; incidence rate ratio 0.18).

It appeared that antibodies provided some protection for seropositive recruits, as evidenced by a higher likelihood of infection among those with lower baseline full-length spike protein IgG titers than in those with higher baseline titers (hazard ratio 0.4, P < .001).

Among the seropositive participants who did acquire a second SARS-CoV-2 infection, viral loads in mid-turbinate nasal swabs were about 10-fold lower than in seronegative recruits who acquired infections during follow-up.

“This finding suggests that some reinfected individuals could have a similar capacity to transmit infection as those who are infected for the first time. The rate at which reinfection occurs after vaccines and natural immunity is important for estimating the proportion of the population that needs to be vaccinated to suppress the pandemic,” the investigators wrote.

Baseline neutralizing antibody titers were detected in 45 of the first 54 seropositive recruits who remained PCR negative throughout follow-up, but also in 6 of 19 seropositive participants who became infected during the 6 weeks of observation.

Lessons

Both Dr. Siedner and Dr. Gupta agreed with the authors that the risks for reinfection that were observed in young, physically fit people may differ for other populations, such as women (only 10% of seropositive recruits and 8% of seronegative recruits were female), older patients, or those who are immunocompromised.

Given that the adjusted odds ratio for reinfection in this study was nearly identical to that of a recent British study comparing infection rates between seropositive and seronegative health care workers, the risk of reinfection for other young adults and for the general population may be similar, Dr. Sealfon and colleagues wrote.

Adding to the challenge of reaching herd immunity is the observation that some patients who have recovered from COVID-19 are skeptical about the need for further protection.

“There are patients who feel like vaccination is of low benefit to them, and I think these are the same people who would be hesitant to get the vaccine anyway,” Dr. Gupta said.

Although no vaccine is perfect – the vaccine failure rate from the mRNA-based vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer/Biontech is about 5% – the protections they afford are unmistakable, Dr. Siedner said.

“I think it’s important to make the distinction that most postvaccination infections by and large have been very mild,” he said. “In people with normal immune systems, we have not seen an onslaught of postvaccination infections requiring hospitalization. Even if people do get infected after vaccination, the vaccines protect people from severe infection, and that’s what we want them to do.”

The investigators stated, “Young adults, of whom a high proportion are asymptomatically infected and become seropositive in the absence of known infection, can be an important source of transmission to more vulnerable populations. Evaluating the protection against subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by seropositivity in young adults is important for determining the need for vaccinating previously infected individuals in this age group.”

The study was funded by the Defense Health Agency and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Dr. Sealfon, Dr. Siedner, and Dr. Gupta have no conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Gupta is a member of the editorial advisory board for this publication.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Asian children less likely to receive ADHD treatment

A study of U.S. children across ethnic and racial groups found that Asians were least likely to receive therapy for ADHD, compared with White children – who had the highest odds of getting some kind of treatment over other groups.

Other studies have identified disparity problems in ADHD diagnosis, although results have varied on inequality metrics. Few studies have looked at Asians separately, according to the study’s lead author, Yu Shi, MD, MPH. “They were usually just classified as ‘other’ or as non-White,” Dr. Shi, a consultant with the Mayo Clinic’s division of pediatric anesthesia in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

, and the way in which clinicians interpret behavior and apply diagnostic criteria.

“Further understanding of how treatment patterns for ADHD may differ based on race, at the time of initial diagnosis and in the early stages of treatment, may help all children receive appropriate evidence-based care,” Dr. Shi and colleagues reported in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers develop large birth cohort

Dr. Shi and colleagues hypothesized that non-Hispanic White children had a greater chance of getting diagnosed and treated within the first year of diagnosis than that of other ethnic and racial cohorts. Using administrative claims data with socioeconomic status information from a national commercial insurance warehouse, they constructed a retrospective birth cohort of children born between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2012. The children had continuous insurance coverage for at least 4 years, and represented non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Self-reporting identified the race/ethnicity groups.

Investigators analyzed ADHD diagnosis and treatment data on 238,011 children between October 2019 and December 2020, using a multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for sex, region, and household income. Primary and secondary outcomes included ADHD diagnosis as defined by recent ICD codes, ADHD behavior, and medication therapies in the clinical setting after initial diagnosis, respectively.

Whites made up most of the cohort (72.7%), followed by Hispanics (9.8%), Asians (6.7%), and Blacks (6.2%). Nearly half the population was female (48.8%). During the follow-up period with these children, 11,401, or 4.8%, had received an ADHD diagnosis. Mean age of diagnosis was 6.5 years, and overall incidence of ADHD was 69 per 10,000 person years (95% confidence interval, 68-70).

Pediatricians were most likely to make an ADHD diagnosis, although the study cited other clinicians, such as psychiatrists, neurologists, psychologists, and family practice clinicians, as responsible for these decisions.

Children diagnosed with ADHD had more years of coverage in the data set, and were more likely to be White and male. The Southern census region had a higher representation of diagnoses (50.6%) than did the Northeast region (11.8%).

Asians at highest odds for no treatment

Taking a closer look at race and ethnicity, Whites had the highest cumulative incidence of ADHD (14.19%), versus Asian children, who had lowest incidence (6.08%). “The curves for Black and Hispanic children were similar in shape and slightly lower than that for White children,” reported the investigators.

White children had higher odds of receiving some kind of treatment, compared with the other groups.

Incidence of medication treatment was lower among Asians and Hispanics. In a striking finding, Asians were most likely to receive no treatment at all (odds ratio compared with White children, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.70). “However, the percentage of Asian children receiving psychotherapy was not significantly lower than other groups, which is different than a 2013 study finding that Asian children with ADHD were less likely to use mental health services,” they noted.

Most of the patients received medication (32.4%) in the first year after diagnosis, whereas (19.4%) received behavioral therapy only. Nineteen percent had both. More than 29% of these cases had no claims associated with either treatment. Among school-aged children, 65.5% were prescribed medications, compared with just 14.4% who received therapy. Twenty percent had no treatment.

Diagnosis with another disorder often preceded ADHD diagnosis. Results varied among racial groups. White children were more likely than were Black children to be diagnosed with an anxiety or adjustment disorder. Relative to White children, Asians were more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, speech sound disorders, or unspecified neurodevelopmental disorders. Even after an ADHD diagnosis, clinicians were more likely to diagnose Asian children with autism.

Parents may influence treatment decisions

Parental views and preferences may explain some of the variations in diagnosis and treatment among the racial/ethnic groups.

“In order for a diagnosis of ADHD to happen, a parent has first to recognize a problem and bring a child for clinical evaluation,” said Dr. Shi. “A certain behavior could be viewed as normal or a problem depending on a person’s cultural or racial background.” It’s unclear whether clinicians played any role in diagnosis disparities, he added. Patients’ concerns about racism might also influence the desire to get treated in health care systems.

Overall, the findings underscore the presence of racial and ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment. Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms, Dr. Shi suggested. While he and his colleagues have no immediate plans to do another ADHD study, “we’re planning on research to understand disparities in surgery in children,” he said.

The authors cited numerous limitations with their study. Use of ICD codes to identify cases might not have represented true clinical diagnosis, since the data were collected for billing, not research purposes. Investigators drew participants from a commercial insurance database, which did not necessarily reflect all U.S. children. The results might not represent a large number of children covered by Medicaid, for example, noted Dr. Shi. “It is more difficult to work with Medicaid data because there’s no national-level Medicaid data for research. Only state-level data is available.”

Because of other data gaps, Dr. Shi and colleagues might have underestimated the number of children in therapy.

A need for ‘culturally sensitive care’

The findings “ultimately demonstrate the need for culturally sensitive care in the diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents,” said Tiffani L. Bell, MD, a psychiatrist in Winston-Salem, N.C., who was not involved with the study. She specializes in child and adolescent psychiatry.

The exact cause for racial disparity in diagnosis and treatment of ADHD is unknown and likely multifaceted, she continued. “It may be due to differences in the way that disruptive behaviors are interrupted based on factors such as race. This study found that Asian parents often brought their children in for evaluation for reasons other than ADHD. Concerns surrounding the stigma of mental health treatment and racism also could contribute to the disparity in diagnosis and treatment,” she said.

Dr. Bell said she hopes to see future studies that address the impact of social determinants of health on mental illness and investigate underlying causes that contribute to disparities in treatment and diagnosis.

The Mayo Clinic supported the study but had no role in its design or research methods. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A study of U.S. children across ethnic and racial groups found that Asians were least likely to receive therapy for ADHD, compared with White children – who had the highest odds of getting some kind of treatment over other groups.

Other studies have identified disparity problems in ADHD diagnosis, although results have varied on inequality metrics. Few studies have looked at Asians separately, according to the study’s lead author, Yu Shi, MD, MPH. “They were usually just classified as ‘other’ or as non-White,” Dr. Shi, a consultant with the Mayo Clinic’s division of pediatric anesthesia in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

, and the way in which clinicians interpret behavior and apply diagnostic criteria.

“Further understanding of how treatment patterns for ADHD may differ based on race, at the time of initial diagnosis and in the early stages of treatment, may help all children receive appropriate evidence-based care,” Dr. Shi and colleagues reported in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers develop large birth cohort

Dr. Shi and colleagues hypothesized that non-Hispanic White children had a greater chance of getting diagnosed and treated within the first year of diagnosis than that of other ethnic and racial cohorts. Using administrative claims data with socioeconomic status information from a national commercial insurance warehouse, they constructed a retrospective birth cohort of children born between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2012. The children had continuous insurance coverage for at least 4 years, and represented non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Self-reporting identified the race/ethnicity groups.

Investigators analyzed ADHD diagnosis and treatment data on 238,011 children between October 2019 and December 2020, using a multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for sex, region, and household income. Primary and secondary outcomes included ADHD diagnosis as defined by recent ICD codes, ADHD behavior, and medication therapies in the clinical setting after initial diagnosis, respectively.

Whites made up most of the cohort (72.7%), followed by Hispanics (9.8%), Asians (6.7%), and Blacks (6.2%). Nearly half the population was female (48.8%). During the follow-up period with these children, 11,401, or 4.8%, had received an ADHD diagnosis. Mean age of diagnosis was 6.5 years, and overall incidence of ADHD was 69 per 10,000 person years (95% confidence interval, 68-70).

Pediatricians were most likely to make an ADHD diagnosis, although the study cited other clinicians, such as psychiatrists, neurologists, psychologists, and family practice clinicians, as responsible for these decisions.

Children diagnosed with ADHD had more years of coverage in the data set, and were more likely to be White and male. The Southern census region had a higher representation of diagnoses (50.6%) than did the Northeast region (11.8%).

Asians at highest odds for no treatment

Taking a closer look at race and ethnicity, Whites had the highest cumulative incidence of ADHD (14.19%), versus Asian children, who had lowest incidence (6.08%). “The curves for Black and Hispanic children were similar in shape and slightly lower than that for White children,” reported the investigators.

White children had higher odds of receiving some kind of treatment, compared with the other groups.

Incidence of medication treatment was lower among Asians and Hispanics. In a striking finding, Asians were most likely to receive no treatment at all (odds ratio compared with White children, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.70). “However, the percentage of Asian children receiving psychotherapy was not significantly lower than other groups, which is different than a 2013 study finding that Asian children with ADHD were less likely to use mental health services,” they noted.

Most of the patients received medication (32.4%) in the first year after diagnosis, whereas (19.4%) received behavioral therapy only. Nineteen percent had both. More than 29% of these cases had no claims associated with either treatment. Among school-aged children, 65.5% were prescribed medications, compared with just 14.4% who received therapy. Twenty percent had no treatment.

Diagnosis with another disorder often preceded ADHD diagnosis. Results varied among racial groups. White children were more likely than were Black children to be diagnosed with an anxiety or adjustment disorder. Relative to White children, Asians were more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, speech sound disorders, or unspecified neurodevelopmental disorders. Even after an ADHD diagnosis, clinicians were more likely to diagnose Asian children with autism.

Parents may influence treatment decisions

Parental views and preferences may explain some of the variations in diagnosis and treatment among the racial/ethnic groups.

“In order for a diagnosis of ADHD to happen, a parent has first to recognize a problem and bring a child for clinical evaluation,” said Dr. Shi. “A certain behavior could be viewed as normal or a problem depending on a person’s cultural or racial background.” It’s unclear whether clinicians played any role in diagnosis disparities, he added. Patients’ concerns about racism might also influence the desire to get treated in health care systems.

Overall, the findings underscore the presence of racial and ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment. Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms, Dr. Shi suggested. While he and his colleagues have no immediate plans to do another ADHD study, “we’re planning on research to understand disparities in surgery in children,” he said.

The authors cited numerous limitations with their study. Use of ICD codes to identify cases might not have represented true clinical diagnosis, since the data were collected for billing, not research purposes. Investigators drew participants from a commercial insurance database, which did not necessarily reflect all U.S. children. The results might not represent a large number of children covered by Medicaid, for example, noted Dr. Shi. “It is more difficult to work with Medicaid data because there’s no national-level Medicaid data for research. Only state-level data is available.”

Because of other data gaps, Dr. Shi and colleagues might have underestimated the number of children in therapy.

A need for ‘culturally sensitive care’

The findings “ultimately demonstrate the need for culturally sensitive care in the diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents,” said Tiffani L. Bell, MD, a psychiatrist in Winston-Salem, N.C., who was not involved with the study. She specializes in child and adolescent psychiatry.

The exact cause for racial disparity in diagnosis and treatment of ADHD is unknown and likely multifaceted, she continued. “It may be due to differences in the way that disruptive behaviors are interrupted based on factors such as race. This study found that Asian parents often brought their children in for evaluation for reasons other than ADHD. Concerns surrounding the stigma of mental health treatment and racism also could contribute to the disparity in diagnosis and treatment,” she said.

Dr. Bell said she hopes to see future studies that address the impact of social determinants of health on mental illness and investigate underlying causes that contribute to disparities in treatment and diagnosis.

The Mayo Clinic supported the study but had no role in its design or research methods. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A study of U.S. children across ethnic and racial groups found that Asians were least likely to receive therapy for ADHD, compared with White children – who had the highest odds of getting some kind of treatment over other groups.

Other studies have identified disparity problems in ADHD diagnosis, although results have varied on inequality metrics. Few studies have looked at Asians separately, according to the study’s lead author, Yu Shi, MD, MPH. “They were usually just classified as ‘other’ or as non-White,” Dr. Shi, a consultant with the Mayo Clinic’s division of pediatric anesthesia in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

, and the way in which clinicians interpret behavior and apply diagnostic criteria.

“Further understanding of how treatment patterns for ADHD may differ based on race, at the time of initial diagnosis and in the early stages of treatment, may help all children receive appropriate evidence-based care,” Dr. Shi and colleagues reported in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers develop large birth cohort

Dr. Shi and colleagues hypothesized that non-Hispanic White children had a greater chance of getting diagnosed and treated within the first year of diagnosis than that of other ethnic and racial cohorts. Using administrative claims data with socioeconomic status information from a national commercial insurance warehouse, they constructed a retrospective birth cohort of children born between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2012. The children had continuous insurance coverage for at least 4 years, and represented non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Self-reporting identified the race/ethnicity groups.

Investigators analyzed ADHD diagnosis and treatment data on 238,011 children between October 2019 and December 2020, using a multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for sex, region, and household income. Primary and secondary outcomes included ADHD diagnosis as defined by recent ICD codes, ADHD behavior, and medication therapies in the clinical setting after initial diagnosis, respectively.

Whites made up most of the cohort (72.7%), followed by Hispanics (9.8%), Asians (6.7%), and Blacks (6.2%). Nearly half the population was female (48.8%). During the follow-up period with these children, 11,401, or 4.8%, had received an ADHD diagnosis. Mean age of diagnosis was 6.5 years, and overall incidence of ADHD was 69 per 10,000 person years (95% confidence interval, 68-70).

Pediatricians were most likely to make an ADHD diagnosis, although the study cited other clinicians, such as psychiatrists, neurologists, psychologists, and family practice clinicians, as responsible for these decisions.

Children diagnosed with ADHD had more years of coverage in the data set, and were more likely to be White and male. The Southern census region had a higher representation of diagnoses (50.6%) than did the Northeast region (11.8%).

Asians at highest odds for no treatment

Taking a closer look at race and ethnicity, Whites had the highest cumulative incidence of ADHD (14.19%), versus Asian children, who had lowest incidence (6.08%). “The curves for Black and Hispanic children were similar in shape and slightly lower than that for White children,” reported the investigators.

White children had higher odds of receiving some kind of treatment, compared with the other groups.

Incidence of medication treatment was lower among Asians and Hispanics. In a striking finding, Asians were most likely to receive no treatment at all (odds ratio compared with White children, 0.54; 95% confidence interval, 0.42-0.70). “However, the percentage of Asian children receiving psychotherapy was not significantly lower than other groups, which is different than a 2013 study finding that Asian children with ADHD were less likely to use mental health services,” they noted.

Most of the patients received medication (32.4%) in the first year after diagnosis, whereas (19.4%) received behavioral therapy only. Nineteen percent had both. More than 29% of these cases had no claims associated with either treatment. Among school-aged children, 65.5% were prescribed medications, compared with just 14.4% who received therapy. Twenty percent had no treatment.

Diagnosis with another disorder often preceded ADHD diagnosis. Results varied among racial groups. White children were more likely than were Black children to be diagnosed with an anxiety or adjustment disorder. Relative to White children, Asians were more likely to be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, speech sound disorders, or unspecified neurodevelopmental disorders. Even after an ADHD diagnosis, clinicians were more likely to diagnose Asian children with autism.

Parents may influence treatment decisions

Parental views and preferences may explain some of the variations in diagnosis and treatment among the racial/ethnic groups.

“In order for a diagnosis of ADHD to happen, a parent has first to recognize a problem and bring a child for clinical evaluation,” said Dr. Shi. “A certain behavior could be viewed as normal or a problem depending on a person’s cultural or racial background.” It’s unclear whether clinicians played any role in diagnosis disparities, he added. Patients’ concerns about racism might also influence the desire to get treated in health care systems.

Overall, the findings underscore the presence of racial and ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis and treatment. Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms, Dr. Shi suggested. While he and his colleagues have no immediate plans to do another ADHD study, “we’re planning on research to understand disparities in surgery in children,” he said.