User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Complete blood count scoring can predict COVID-19 severity

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

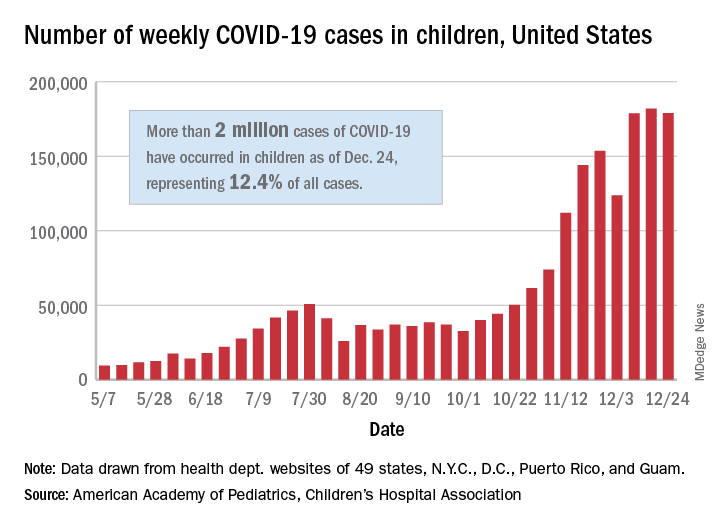

New pediatric cases down as U.S. tops 2 million children with COVID-19

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

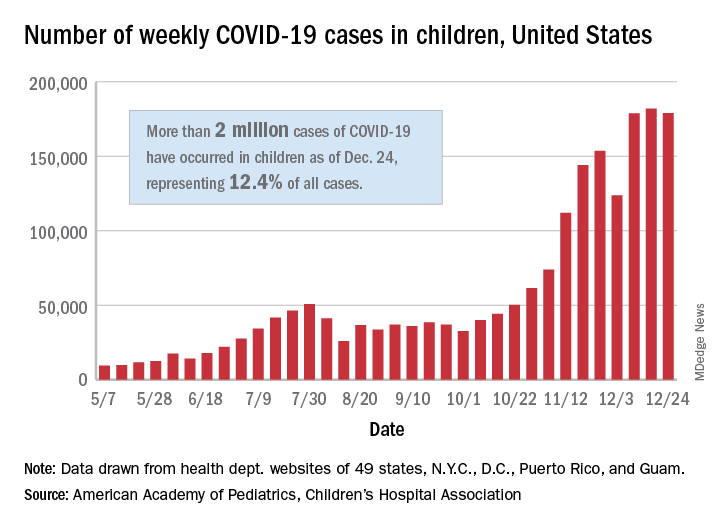

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

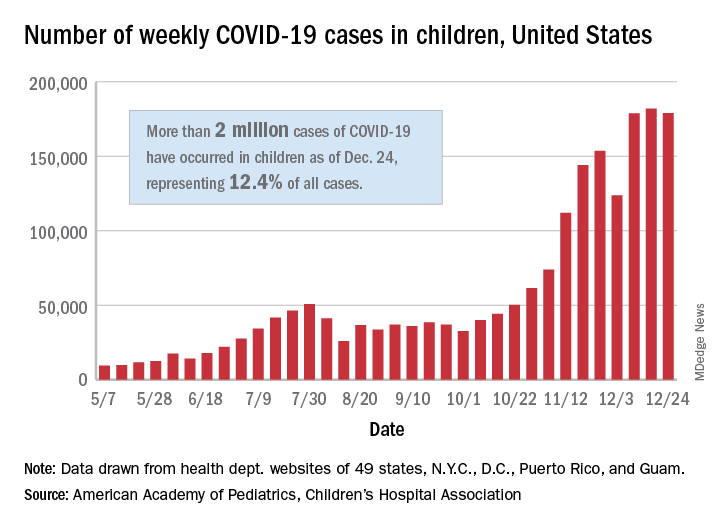

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

2.1 Million COVID Vaccine Doses Given in U.S.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

CDC issues COVID-19 vaccine guidance for underlying conditions

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.

“Adults of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC said in the guidance, posted on Dec. 26. “mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may be administered to people with underlying medical conditions provided they have not had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients in the vaccine.”

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA, or messenger RNA.

The CDC guidance had specific information for people with HIV, weakened immune systems, and autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and Bell’s palsy who are thinking of getting the vaccine.

People with HIV and weakened immune systems “may receive a COVID-19 vaccine. However, they should be aware of the limited safety data,” the CDC said.

There’s no information available yet about the safety of the vaccines for people with weakened immune systems. People with HIV were included in clinical trials, but “safety data specific to this group are not yet available at this time,” the CDC said.

Cases of Bell’s palsy, a temporary facial paralysis, were reported in people receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration said Dec. 17.

But the new CDC guidance said that the FDA “does not consider these to be above the rate expected in the general population. They have not concluded these cases were caused by vaccination. Therefore, persons who have previously had Bell’s palsy may receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.”

Researchers have determined the vaccines are safe for people with GBS, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks nerves just as they leave the spinal cord, the CDC said.

“To date, no cases of GBS have been reported following vaccination among participants in the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials,” the CDC guidance said. “With few exceptions, the independent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices general best practice guidelines for immunization do not include a history of GBS as a precaution to vaccination with other vaccines.”

For months, the CDC and other health authorities have said that people with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe cases of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.

“Adults of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC said in the guidance, posted on Dec. 26. “mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may be administered to people with underlying medical conditions provided they have not had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients in the vaccine.”

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA, or messenger RNA.

The CDC guidance had specific information for people with HIV, weakened immune systems, and autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and Bell’s palsy who are thinking of getting the vaccine.

People with HIV and weakened immune systems “may receive a COVID-19 vaccine. However, they should be aware of the limited safety data,” the CDC said.

There’s no information available yet about the safety of the vaccines for people with weakened immune systems. People with HIV were included in clinical trials, but “safety data specific to this group are not yet available at this time,” the CDC said.

Cases of Bell’s palsy, a temporary facial paralysis, were reported in people receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration said Dec. 17.

But the new CDC guidance said that the FDA “does not consider these to be above the rate expected in the general population. They have not concluded these cases were caused by vaccination. Therefore, persons who have previously had Bell’s palsy may receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.”

Researchers have determined the vaccines are safe for people with GBS, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks nerves just as they leave the spinal cord, the CDC said.

“To date, no cases of GBS have been reported following vaccination among participants in the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials,” the CDC guidance said. “With few exceptions, the independent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices general best practice guidelines for immunization do not include a history of GBS as a precaution to vaccination with other vaccines.”

For months, the CDC and other health authorities have said that people with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe cases of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued updated guidance for people with underlying medical conditions who are considering getting the coronavirus vaccine.

“Adults of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC said in the guidance, posted on Dec. 26. “mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may be administered to people with underlying medical conditions provided they have not had a severe allergic reaction to any of the ingredients in the vaccine.”

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use mRNA, or messenger RNA.

The CDC guidance had specific information for people with HIV, weakened immune systems, and autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and Bell’s palsy who are thinking of getting the vaccine.

People with HIV and weakened immune systems “may receive a COVID-19 vaccine. However, they should be aware of the limited safety data,” the CDC said.

There’s no information available yet about the safety of the vaccines for people with weakened immune systems. People with HIV were included in clinical trials, but “safety data specific to this group are not yet available at this time,” the CDC said.

Cases of Bell’s palsy, a temporary facial paralysis, were reported in people receiving the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration said Dec. 17.

But the new CDC guidance said that the FDA “does not consider these to be above the rate expected in the general population. They have not concluded these cases were caused by vaccination. Therefore, persons who have previously had Bell’s palsy may receive an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.”

Researchers have determined the vaccines are safe for people with GBS, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks nerves just as they leave the spinal cord, the CDC said.

“To date, no cases of GBS have been reported following vaccination among participants in the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials,” the CDC guidance said. “With few exceptions, the independent Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices general best practice guidelines for immunization do not include a history of GBS as a precaution to vaccination with other vaccines.”

For months, the CDC and other health authorities have said that people with certain medical conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe cases of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer treatment delays are deadly: 5- and 10-year data

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant delays in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment — and a new study shows just how deadly delaying cancer treatment can be.

The study found evidence that longer time to starting treatment after diagnosis was generally associated with higher mortality across several common cancers, most notably for colon and early-stage lung cancer.

“There is a limit to how long we can safely defer treatment for cancer therapies, pandemic or not, which may be shorter than we think,” lead author Eugene Cone, MD, Combined Harvard Program in Urologic Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“When you consider that cancer screening may have been delayed during the pandemic, which would further increase the period between developing a disease and getting therapy, timely treatment for cancer has never been more important,” Cone added.

The study was published online December 14 in JAMA Network Open.

The sooner the better

Using the National Cancer Database, Cone and colleagues identified roughly 2.24 million patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast (52%), prostate (38%), colon (4%) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, 6%) between 2004 and 2015. Treatment and outcome data were analyzed from January to March 2020.

The time-to-treatment initiation (TTI) – the interval between cancer diagnosis and receipt of curative-intent therapy – was categorized as 8 to 60 days (reference), 61 to 120 days, 121 to 180 days, and 181 to 365 days. Median TTI was 32 days for breast, 79 days for prostate, 41 days for NSCLC, and 26 days for colon cancer.

All four cancers benefitted to some degree from a short interval between diagnosis and therapy, the researchers found.

Across all four cancers, increasing TTI was generally associated with higher predicted mortality at 5 and 10 years, although the degree varied by cancer type and stage. The most pronounced association between increasing TTI and mortality was observed for colon and lung cancer.

For example, for stage III colon cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 38.9% and 54%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days, and increased to 47.8% and 63.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

Each additional 60-day delay was associated with a 3.2% to 6% increase in 5-year mortality for stage III colon cancer and a 0.9% to 4.6% increase for stage I colon cancer, with a longer 10-year time horizon showing larger effect sizes with increasing TTI.

For stage I NSCLC, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 47.4% and 72.6%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days compared with 47.6% and 72.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

For stage I NSCLC, there was a 4% to 6.2% absolute increase in 5-year mortality for increased TTI groups compared with the 8- to 60-day reference group, with larger effect sizes on 10-year mortality. The data precluded conclusions about stage II NSCLC.

“For prostate cancer, deferral of treatment by even a few months was associated with a significant impact on mortality,” Cone told Medscape Medical News.

For high-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 12.8% and 31.2%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days increasing to 14.1% and 33.8%, respectively with TTI at 181-365 days.

For intermediate-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 7.4% and 20.4% with TTI of 61-120 days vs 8.3% and 22.6% with TTI at 181-365 days.

The data show all-cause mortality differences of 2.2% at 5 years and 4.6% at 10 years between high-risk prostate cancer patients who were treated expeditiously vs those waiting 4 to 6 months and differences of 0.9% at 5 years and 2.4% at 10 years for similar intermediate-risk patients.

No surprises

Turning to breast cancer, increased TTI was associated with the most negative survival effects for stage II and III breast cancer.

For stage II breast cancer, for example, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 17.7% and 30.5%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days vs 21.7% and 36.5% with TTI at 181-365 days.

Even for stage I breast cancer patients, there were significant differences in all-cause mortality with delayed definitive therapy, although the effect size is clinically small, the researchers report.

Patients with stage IA or IB breast cancer who were not treated until 61 to 120 days after diagnosis had 1.3% and 2.3% increased mortality at 5 years and 10 years, respectively, and those waiting longer suffered even greater increases in mortality. “As such, our analysis underscores the importance of timely definitive treatment, even for stage I breast cancer,” the authors write.

Charles Shapiro, MD, director of translational breast cancer research for the Mount Sinai Health System, New York City, was not surprised by the data.

The observation that delays in initiating cancer treatment are associated with worse survival is “not new, as delays in primary surgical treatments and chemotherapy for early-stage disease is an adverse prognostic factor for clinical outcomes,” Shapiro told Medscape Medical News.

“The bottom line is primary surgery and the start of chemotherapy should probably occur as soon as clinically feasible,” said Shapiro, who was not involved in the study.

The authors of an accompanying editorial agree.

This study supports avoiding unnecessary treatment delays and prioritizing timely cancer care, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, write Laura Van Metre Baum, MD, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues.

They note, however, that primary care, “the most important conduit for cancer screening and initial evaluation of new symptoms, has been the hardest hit economically and the most subject to profound disruption and restructuring during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“In many centers, cancer care delivery has been disrupted and nonstandard therapies offered in an effort to minimize exposure of this high-risk group to the virus. The implications in appropriately balancing the urgency of cancer care and the threat of COVID-19 exposure in the pandemic are more complex,” the editorialists conclude.

Cone, Shapiro, and Van Metre Baum have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. This work won first prize in the Commission on Cancer 2020 Cancer Research Paper Competition and was virtually presented at the Commission on Cancer Plenary Session on October 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant delays in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment — and a new study shows just how deadly delaying cancer treatment can be.

The study found evidence that longer time to starting treatment after diagnosis was generally associated with higher mortality across several common cancers, most notably for colon and early-stage lung cancer.

“There is a limit to how long we can safely defer treatment for cancer therapies, pandemic or not, which may be shorter than we think,” lead author Eugene Cone, MD, Combined Harvard Program in Urologic Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“When you consider that cancer screening may have been delayed during the pandemic, which would further increase the period between developing a disease and getting therapy, timely treatment for cancer has never been more important,” Cone added.

The study was published online December 14 in JAMA Network Open.

The sooner the better

Using the National Cancer Database, Cone and colleagues identified roughly 2.24 million patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast (52%), prostate (38%), colon (4%) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, 6%) between 2004 and 2015. Treatment and outcome data were analyzed from January to March 2020.

The time-to-treatment initiation (TTI) – the interval between cancer diagnosis and receipt of curative-intent therapy – was categorized as 8 to 60 days (reference), 61 to 120 days, 121 to 180 days, and 181 to 365 days. Median TTI was 32 days for breast, 79 days for prostate, 41 days for NSCLC, and 26 days for colon cancer.

All four cancers benefitted to some degree from a short interval between diagnosis and therapy, the researchers found.

Across all four cancers, increasing TTI was generally associated with higher predicted mortality at 5 and 10 years, although the degree varied by cancer type and stage. The most pronounced association between increasing TTI and mortality was observed for colon and lung cancer.

For example, for stage III colon cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 38.9% and 54%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days, and increased to 47.8% and 63.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

Each additional 60-day delay was associated with a 3.2% to 6% increase in 5-year mortality for stage III colon cancer and a 0.9% to 4.6% increase for stage I colon cancer, with a longer 10-year time horizon showing larger effect sizes with increasing TTI.

For stage I NSCLC, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 47.4% and 72.6%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days compared with 47.6% and 72.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

For stage I NSCLC, there was a 4% to 6.2% absolute increase in 5-year mortality for increased TTI groups compared with the 8- to 60-day reference group, with larger effect sizes on 10-year mortality. The data precluded conclusions about stage II NSCLC.

“For prostate cancer, deferral of treatment by even a few months was associated with a significant impact on mortality,” Cone told Medscape Medical News.

For high-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 12.8% and 31.2%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days increasing to 14.1% and 33.8%, respectively with TTI at 181-365 days.

For intermediate-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 7.4% and 20.4% with TTI of 61-120 days vs 8.3% and 22.6% with TTI at 181-365 days.

The data show all-cause mortality differences of 2.2% at 5 years and 4.6% at 10 years between high-risk prostate cancer patients who were treated expeditiously vs those waiting 4 to 6 months and differences of 0.9% at 5 years and 2.4% at 10 years for similar intermediate-risk patients.

No surprises

Turning to breast cancer, increased TTI was associated with the most negative survival effects for stage II and III breast cancer.

For stage II breast cancer, for example, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 17.7% and 30.5%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days vs 21.7% and 36.5% with TTI at 181-365 days.

Even for stage I breast cancer patients, there were significant differences in all-cause mortality with delayed definitive therapy, although the effect size is clinically small, the researchers report.

Patients with stage IA or IB breast cancer who were not treated until 61 to 120 days after diagnosis had 1.3% and 2.3% increased mortality at 5 years and 10 years, respectively, and those waiting longer suffered even greater increases in mortality. “As such, our analysis underscores the importance of timely definitive treatment, even for stage I breast cancer,” the authors write.

Charles Shapiro, MD, director of translational breast cancer research for the Mount Sinai Health System, New York City, was not surprised by the data.

The observation that delays in initiating cancer treatment are associated with worse survival is “not new, as delays in primary surgical treatments and chemotherapy for early-stage disease is an adverse prognostic factor for clinical outcomes,” Shapiro told Medscape Medical News.

“The bottom line is primary surgery and the start of chemotherapy should probably occur as soon as clinically feasible,” said Shapiro, who was not involved in the study.

The authors of an accompanying editorial agree.

This study supports avoiding unnecessary treatment delays and prioritizing timely cancer care, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, write Laura Van Metre Baum, MD, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues.

They note, however, that primary care, “the most important conduit for cancer screening and initial evaluation of new symptoms, has been the hardest hit economically and the most subject to profound disruption and restructuring during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“In many centers, cancer care delivery has been disrupted and nonstandard therapies offered in an effort to minimize exposure of this high-risk group to the virus. The implications in appropriately balancing the urgency of cancer care and the threat of COVID-19 exposure in the pandemic are more complex,” the editorialists conclude.

Cone, Shapiro, and Van Metre Baum have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. This work won first prize in the Commission on Cancer 2020 Cancer Research Paper Competition and was virtually presented at the Commission on Cancer Plenary Session on October 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant delays in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment — and a new study shows just how deadly delaying cancer treatment can be.

The study found evidence that longer time to starting treatment after diagnosis was generally associated with higher mortality across several common cancers, most notably for colon and early-stage lung cancer.

“There is a limit to how long we can safely defer treatment for cancer therapies, pandemic or not, which may be shorter than we think,” lead author Eugene Cone, MD, Combined Harvard Program in Urologic Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, told Medscape Medical News.

“When you consider that cancer screening may have been delayed during the pandemic, which would further increase the period between developing a disease and getting therapy, timely treatment for cancer has never been more important,” Cone added.

The study was published online December 14 in JAMA Network Open.

The sooner the better

Using the National Cancer Database, Cone and colleagues identified roughly 2.24 million patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic breast (52%), prostate (38%), colon (4%) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, 6%) between 2004 and 2015. Treatment and outcome data were analyzed from January to March 2020.

The time-to-treatment initiation (TTI) – the interval between cancer diagnosis and receipt of curative-intent therapy – was categorized as 8 to 60 days (reference), 61 to 120 days, 121 to 180 days, and 181 to 365 days. Median TTI was 32 days for breast, 79 days for prostate, 41 days for NSCLC, and 26 days for colon cancer.

All four cancers benefitted to some degree from a short interval between diagnosis and therapy, the researchers found.

Across all four cancers, increasing TTI was generally associated with higher predicted mortality at 5 and 10 years, although the degree varied by cancer type and stage. The most pronounced association between increasing TTI and mortality was observed for colon and lung cancer.

For example, for stage III colon cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 38.9% and 54%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days, and increased to 47.8% and 63.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

Each additional 60-day delay was associated with a 3.2% to 6% increase in 5-year mortality for stage III colon cancer and a 0.9% to 4.6% increase for stage I colon cancer, with a longer 10-year time horizon showing larger effect sizes with increasing TTI.

For stage I NSCLC, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 47.4% and 72.6%, respectively, with TTI of 61 to 120 days compared with 47.6% and 72.8%, respectively, with TTI of 181 to 365 days.

For stage I NSCLC, there was a 4% to 6.2% absolute increase in 5-year mortality for increased TTI groups compared with the 8- to 60-day reference group, with larger effect sizes on 10-year mortality. The data precluded conclusions about stage II NSCLC.

“For prostate cancer, deferral of treatment by even a few months was associated with a significant impact on mortality,” Cone told Medscape Medical News.

For high-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 12.8% and 31.2%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days increasing to 14.1% and 33.8%, respectively with TTI at 181-365 days.

For intermediate-risk prostate cancer, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 7.4% and 20.4% with TTI of 61-120 days vs 8.3% and 22.6% with TTI at 181-365 days.

The data show all-cause mortality differences of 2.2% at 5 years and 4.6% at 10 years between high-risk prostate cancer patients who were treated expeditiously vs those waiting 4 to 6 months and differences of 0.9% at 5 years and 2.4% at 10 years for similar intermediate-risk patients.

No surprises

Turning to breast cancer, increased TTI was associated with the most negative survival effects for stage II and III breast cancer.

For stage II breast cancer, for example, 5- and 10-year predicted mortality was 17.7% and 30.5%, respectively, with TTI of 61-120 days vs 21.7% and 36.5% with TTI at 181-365 days.

Even for stage I breast cancer patients, there were significant differences in all-cause mortality with delayed definitive therapy, although the effect size is clinically small, the researchers report.

Patients with stage IA or IB breast cancer who were not treated until 61 to 120 days after diagnosis had 1.3% and 2.3% increased mortality at 5 years and 10 years, respectively, and those waiting longer suffered even greater increases in mortality. “As such, our analysis underscores the importance of timely definitive treatment, even for stage I breast cancer,” the authors write.

Charles Shapiro, MD, director of translational breast cancer research for the Mount Sinai Health System, New York City, was not surprised by the data.

The observation that delays in initiating cancer treatment are associated with worse survival is “not new, as delays in primary surgical treatments and chemotherapy for early-stage disease is an adverse prognostic factor for clinical outcomes,” Shapiro told Medscape Medical News.

“The bottom line is primary surgery and the start of chemotherapy should probably occur as soon as clinically feasible,” said Shapiro, who was not involved in the study.

The authors of an accompanying editorial agree.

This study supports avoiding unnecessary treatment delays and prioritizing timely cancer care, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, write Laura Van Metre Baum, MD, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues.

They note, however, that primary care, “the most important conduit for cancer screening and initial evaluation of new symptoms, has been the hardest hit economically and the most subject to profound disruption and restructuring during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“In many centers, cancer care delivery has been disrupted and nonstandard therapies offered in an effort to minimize exposure of this high-risk group to the virus. The implications in appropriately balancing the urgency of cancer care and the threat of COVID-19 exposure in the pandemic are more complex,” the editorialists conclude.

Cone, Shapiro, and Van Metre Baum have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. This work won first prize in the Commission on Cancer 2020 Cancer Research Paper Competition and was virtually presented at the Commission on Cancer Plenary Session on October 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scant risk for SARS-CoV-2 from hospital air

Everywhere they look within hospitals, researchers find RNA from SARS-CoV-2 in the air. But viable viruses typically are found only close to patients, according to a review of published studies.

The finding supports recommendations to use surgical masks in most parts of the hospital, reserving respirators (such as N95 or FFP2) for aerosol-generating procedures on patients’ respiratory tracts, said Gabriel Birgand, PhD, an infectious disease researcher at Imperial College London.

“When the virus is spreading a lot in the community, it’s probably more likely for you to be contaminated in your friends’ areas or in your building than in your work area, where you are well equipped and compliant with all the measures,” he said in an interview. “So it’s pretty good news.”

The systematic review by Dr. Birgand and colleagues was published in JAMA Network Open.

Recommended precautions to protect health care workers from SARS-CoV-2 infections remain controversial. Most authorities believe droplets are the primary route of transmission, which would mean surgical masks may be sufficient protection. But some research has suggested transmission by aerosols as well, making N95 respirators seem necessary. There is even disagreement about the definitions of the words “aerosol” and “droplet.”

To better understand where traces of the virus can be found in the air in hospitals, Dr. Birgand and colleagues analyzed all the studies they could find on the subject in English.

They identified 24 articles with original data. All of the studies used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to identify SARS-CoV-2 RNA. In five studies, attempts were also made to culture viable viruses. Three studies assessed the particle size relative to RNA concentration or viral titer.

Of 893 air samples across the 24 studies, 52.7% were taken from areas close to patients, 26.5% were taken in clinical areas, 13.7% in staff areas, 4.7% in public areas, and 2.4% in toilets or bathrooms.

Among those studies that quantified RNA, the median interquartile range of concentrations varied from 1.0 x 103 copies/m3 in clinical areas to 9.7 x 103 copies/m3 in toilets or bathrooms.

One study found an RNA concentration of 2.0 x 103 copies for particle sizes >4 mcm and 1.3 x 103 copies/m3 for particle sizes ≤4 mcm, both in patients’ rooms.

Three studies included viral cultures; of those, two resulted in positive cultures, both in a non-ICU setting. In one study, 3 of 39 samples were positive, and in the other, 4 of 4 were positive. Viral cultures in toilets, clinical areas, staff areas, and public areas were negative.

One of these studies assessed viral concentration and found that the median interquartile range was 4.8 tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/m3 for particles <1 mcm, 4.27 TCID50/m3 for particles 1-4 mcm, and 1.82 TCID50/m3 for particles >4 mcm.

Although viable viruses weren’t found in staff areas, the presence of viral RNA in places such as dining rooms and meeting rooms raises a concern, Dr. Birgand said.

“All of these staff areas are probably playing an important role in contamination,” he said. “It’s pretty easy to see when you are dining, you are not wearing a face mask, and it’s associated with a strong risk when there is a strong dissemination of the virus in the community.”

Studies on contact tracing among health care workers have also identified meeting rooms and dining rooms as the second most common source of infection after community contact, he said.

In general, the findings of the review correspond to epidemiologic studies, said Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist with the Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security, Washington, who was not involved in the review. “Absent aerosol-generating procedures, health care workers are largely not getting infected when they take droplet precautions.”

One reason may be that patients shed the most infectious viruses a couple of days before and after symptoms begin. By the time they’re hospitalized, they’re less likely to be contagious but may continue to shed viral RNA.

“We don’t really know the basis for the persistence of RNA being produced long after people have been infected and have recovered from the acute infection,” she said, “but it has been observed quite frequently.”

Although the virus cannot remain viable for very long in the air, remnants may still be detected in the form of RNA, Dr. Rasmussen said. In addition, hospitals often do a good job of ventilation.

She pointed out that it can be difficult to cultivate viruses in air samples because of contaminants such as bacteria and fungi. “That’s one of the limitations of a study like this. You’re not really sure if it’s because there’s no viable virus there or because you just aren’t able to collect samples that would allow you to determine that.”

Dr. Birgand and colleagues acknowledged other limitations. The studies they reviewed used different approaches to sampling. Different procedures may have been underway in the rooms being sampled, and factors such as temperature and humidity could have affected the results. In addition, the studies used different cycle thresholds for PCR positivity.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everywhere they look within hospitals, researchers find RNA from SARS-CoV-2 in the air. But viable viruses typically are found only close to patients, according to a review of published studies.

The finding supports recommendations to use surgical masks in most parts of the hospital, reserving respirators (such as N95 or FFP2) for aerosol-generating procedures on patients’ respiratory tracts, said Gabriel Birgand, PhD, an infectious disease researcher at Imperial College London.

“When the virus is spreading a lot in the community, it’s probably more likely for you to be contaminated in your friends’ areas or in your building than in your work area, where you are well equipped and compliant with all the measures,” he said in an interview. “So it’s pretty good news.”

The systematic review by Dr. Birgand and colleagues was published in JAMA Network Open.

Recommended precautions to protect health care workers from SARS-CoV-2 infections remain controversial. Most authorities believe droplets are the primary route of transmission, which would mean surgical masks may be sufficient protection. But some research has suggested transmission by aerosols as well, making N95 respirators seem necessary. There is even disagreement about the definitions of the words “aerosol” and “droplet.”

To better understand where traces of the virus can be found in the air in hospitals, Dr. Birgand and colleagues analyzed all the studies they could find on the subject in English.

They identified 24 articles with original data. All of the studies used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to identify SARS-CoV-2 RNA. In five studies, attempts were also made to culture viable viruses. Three studies assessed the particle size relative to RNA concentration or viral titer.

Of 893 air samples across the 24 studies, 52.7% were taken from areas close to patients, 26.5% were taken in clinical areas, 13.7% in staff areas, 4.7% in public areas, and 2.4% in toilets or bathrooms.

Among those studies that quantified RNA, the median interquartile range of concentrations varied from 1.0 x 103 copies/m3 in clinical areas to 9.7 x 103 copies/m3 in toilets or bathrooms.

One study found an RNA concentration of 2.0 x 103 copies for particle sizes >4 mcm and 1.3 x 103 copies/m3 for particle sizes ≤4 mcm, both in patients’ rooms.

Three studies included viral cultures; of those, two resulted in positive cultures, both in a non-ICU setting. In one study, 3 of 39 samples were positive, and in the other, 4 of 4 were positive. Viral cultures in toilets, clinical areas, staff areas, and public areas were negative.

One of these studies assessed viral concentration and found that the median interquartile range was 4.8 tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/m3 for particles <1 mcm, 4.27 TCID50/m3 for particles 1-4 mcm, and 1.82 TCID50/m3 for particles >4 mcm.

Although viable viruses weren’t found in staff areas, the presence of viral RNA in places such as dining rooms and meeting rooms raises a concern, Dr. Birgand said.

“All of these staff areas are probably playing an important role in contamination,” he said. “It’s pretty easy to see when you are dining, you are not wearing a face mask, and it’s associated with a strong risk when there is a strong dissemination of the virus in the community.”

Studies on contact tracing among health care workers have also identified meeting rooms and dining rooms as the second most common source of infection after community contact, he said.

In general, the findings of the review correspond to epidemiologic studies, said Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist with the Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security, Washington, who was not involved in the review. “Absent aerosol-generating procedures, health care workers are largely not getting infected when they take droplet precautions.”

One reason may be that patients shed the most infectious viruses a couple of days before and after symptoms begin. By the time they’re hospitalized, they’re less likely to be contagious but may continue to shed viral RNA.

“We don’t really know the basis for the persistence of RNA being produced long after people have been infected and have recovered from the acute infection,” she said, “but it has been observed quite frequently.”

Although the virus cannot remain viable for very long in the air, remnants may still be detected in the form of RNA, Dr. Rasmussen said. In addition, hospitals often do a good job of ventilation.

She pointed out that it can be difficult to cultivate viruses in air samples because of contaminants such as bacteria and fungi. “That’s one of the limitations of a study like this. You’re not really sure if it’s because there’s no viable virus there or because you just aren’t able to collect samples that would allow you to determine that.”

Dr. Birgand and colleagues acknowledged other limitations. The studies they reviewed used different approaches to sampling. Different procedures may have been underway in the rooms being sampled, and factors such as temperature and humidity could have affected the results. In addition, the studies used different cycle thresholds for PCR positivity.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Everywhere they look within hospitals, researchers find RNA from SARS-CoV-2 in the air. But viable viruses typically are found only close to patients, according to a review of published studies.

The finding supports recommendations to use surgical masks in most parts of the hospital, reserving respirators (such as N95 or FFP2) for aerosol-generating procedures on patients’ respiratory tracts, said Gabriel Birgand, PhD, an infectious disease researcher at Imperial College London.

“When the virus is spreading a lot in the community, it’s probably more likely for you to be contaminated in your friends’ areas or in your building than in your work area, where you are well equipped and compliant with all the measures,” he said in an interview. “So it’s pretty good news.”

The systematic review by Dr. Birgand and colleagues was published in JAMA Network Open.

Recommended precautions to protect health care workers from SARS-CoV-2 infections remain controversial. Most authorities believe droplets are the primary route of transmission, which would mean surgical masks may be sufficient protection. But some research has suggested transmission by aerosols as well, making N95 respirators seem necessary. There is even disagreement about the definitions of the words “aerosol” and “droplet.”

To better understand where traces of the virus can be found in the air in hospitals, Dr. Birgand and colleagues analyzed all the studies they could find on the subject in English.

They identified 24 articles with original data. All of the studies used reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to identify SARS-CoV-2 RNA. In five studies, attempts were also made to culture viable viruses. Three studies assessed the particle size relative to RNA concentration or viral titer.

Of 893 air samples across the 24 studies, 52.7% were taken from areas close to patients, 26.5% were taken in clinical areas, 13.7% in staff areas, 4.7% in public areas, and 2.4% in toilets or bathrooms.

Among those studies that quantified RNA, the median interquartile range of concentrations varied from 1.0 x 103 copies/m3 in clinical areas to 9.7 x 103 copies/m3 in toilets or bathrooms.

One study found an RNA concentration of 2.0 x 103 copies for particle sizes >4 mcm and 1.3 x 103 copies/m3 for particle sizes ≤4 mcm, both in patients’ rooms.

Three studies included viral cultures; of those, two resulted in positive cultures, both in a non-ICU setting. In one study, 3 of 39 samples were positive, and in the other, 4 of 4 were positive. Viral cultures in toilets, clinical areas, staff areas, and public areas were negative.

One of these studies assessed viral concentration and found that the median interquartile range was 4.8 tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)/m3 for particles <1 mcm, 4.27 TCID50/m3 for particles 1-4 mcm, and 1.82 TCID50/m3 for particles >4 mcm.

Although viable viruses weren’t found in staff areas, the presence of viral RNA in places such as dining rooms and meeting rooms raises a concern, Dr. Birgand said.

“All of these staff areas are probably playing an important role in contamination,” he said. “It’s pretty easy to see when you are dining, you are not wearing a face mask, and it’s associated with a strong risk when there is a strong dissemination of the virus in the community.”

Studies on contact tracing among health care workers have also identified meeting rooms and dining rooms as the second most common source of infection after community contact, he said.

In general, the findings of the review correspond to epidemiologic studies, said Angela Rasmussen, PhD, a virologist with the Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security, Washington, who was not involved in the review. “Absent aerosol-generating procedures, health care workers are largely not getting infected when they take droplet precautions.”

One reason may be that patients shed the most infectious viruses a couple of days before and after symptoms begin. By the time they’re hospitalized, they’re less likely to be contagious but may continue to shed viral RNA.

“We don’t really know the basis for the persistence of RNA being produced long after people have been infected and have recovered from the acute infection,” she said, “but it has been observed quite frequently.”

Although the virus cannot remain viable for very long in the air, remnants may still be detected in the form of RNA, Dr. Rasmussen said. In addition, hospitals often do a good job of ventilation.

She pointed out that it can be difficult to cultivate viruses in air samples because of contaminants such as bacteria and fungi. “That’s one of the limitations of a study like this. You’re not really sure if it’s because there’s no viable virus there or because you just aren’t able to collect samples that would allow you to determine that.”

Dr. Birgand and colleagues acknowledged other limitations. The studies they reviewed used different approaches to sampling. Different procedures may have been underway in the rooms being sampled, and factors such as temperature and humidity could have affected the results. In addition, the studies used different cycle thresholds for PCR positivity.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New resilience center targets traumatized health care workers

A physician assistant participating in a virtual workshop began to cry, confessing that she felt overwhelmed with guilt because New Yorkers were hailing her as a frontline hero in the pandemic. That was when Joe Ciavarro knew he was in the right place.

“She was saying all the things I could not verbalize because I, too, didn’t feel like I deserved all this praise and thousands of people cheering for us every evening when people were losing jobs, didn’t have money for food, and their loved ones were dying without family at their side,” says Mr. Ciavarro, a PA at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York.

Mr. Ciavarro, who also manages 170 other PAs on two of Mount Sinai’s campuses in Manhattan, has been on the front lines since COVID-19 first hit; he lost a colleague and friend to suicide in September.

The mental anguish from his job prompted him to sign up for the resilience workshop offered by Mount Sinai’s Center for Stress, Resilience, and Personal Growth. The center – the first of its kind in North America – was launched in June to help health care workers like him cope with the intense psychological pressures they were facing. The weekly workshops became a safe place where Mr. Ciavarro and other staff members could share their darkest fears and learn ways to help them deal with their situation.

“It’s been grueling but we learned how to take care of ourselves so we can take care of our patients,” said Mr. Ciavarro. “This has become like a guided group therapy session on ways to manage and develop resilience. And I feel like my emotions are validated, knowing that others feel the same way.”

Caring for their own

Medical professionals treating patients with COVID-19 are in similar predicaments, and the psychological fallout is enormous: They’re exhausted by the seemingly never-ending patient load and staffing shortages, and haunted by fears for their own safety and that of their families. Studies in China, Canada, and Italy have revealed that a significant number of doctors and nurses in the early days of the pandemic experienced high levels of distress, depression, anxiety, nightmares, and insomnia.