User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Children and COVID: New cases increase for third straight week

There were almost 142,000 new cases reported during the week of Nov. 12-18, marking an increase of 16% over the previous week and the 15th straight week with a weekly total over 100,000, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said.

Regional data show that the Midwest has experienced the largest share of this latest surge, followed by the Northeast. Cases increased in the South during the week of Nov. 12-18 after holding steady over the previous 2 weeks, while new cases in the West dropped in the last week. At the state level, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont again reported the largest percent increases, with Michigan, Minnesota, and New Mexico also above average, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show similar trends for both emergency department visits and hospital admissions, as both have risen in November after declines that began in late August and early September.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is 6.77 million since the pandemic began, based on the AAP/CHA accounting of state cases, although Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer, suggesting the actual number is higher. The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 5.96 million, but there are age discrepancies between the CDC and the AAP/CHA’s state-based data.

The vaccine gap is closing

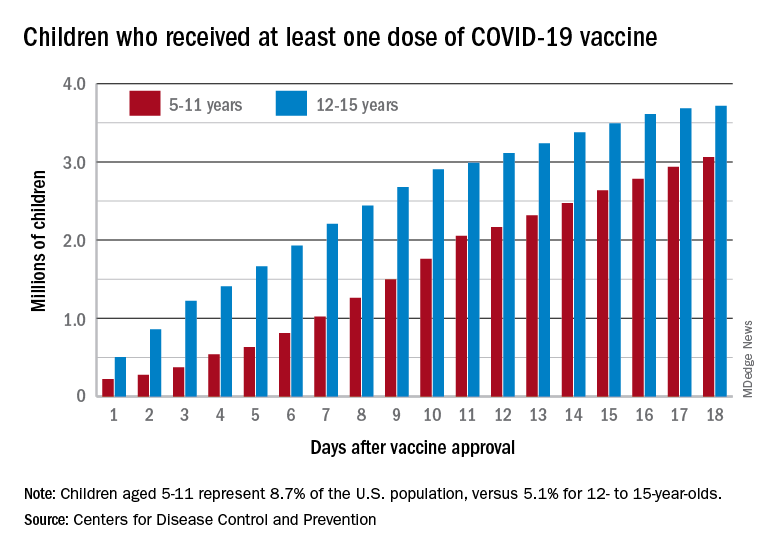

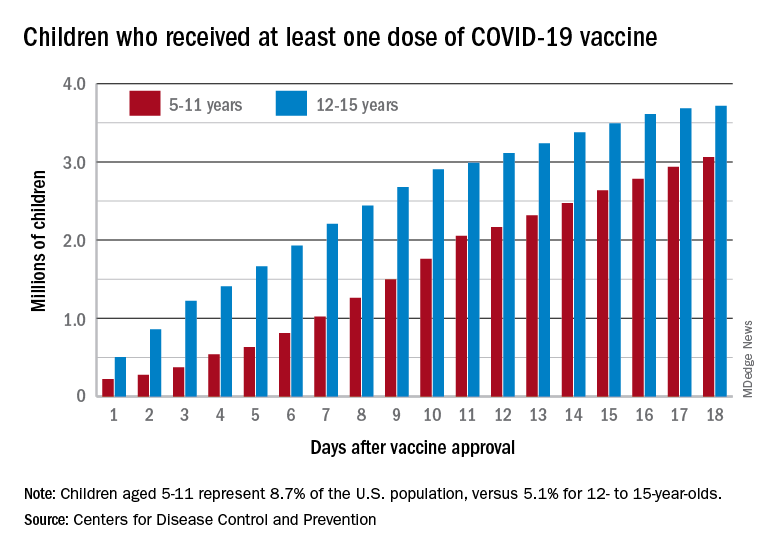

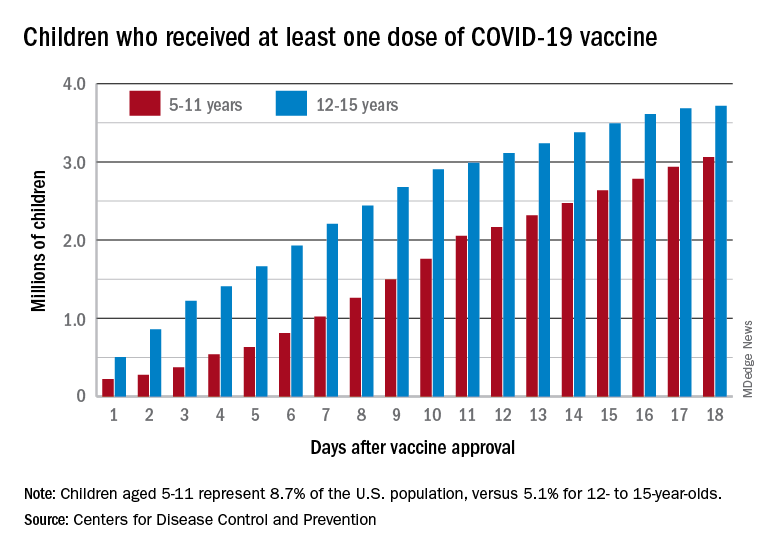

Vaccinations among the recently eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have steadily increased following a somewhat slow start. The initial pace was behind that of the 12- to 15-years-olds through the first postapproval week but has since closed the gap, based on data from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The tally of children who received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine among the 5- to 11-year-olds was behind the older group by almost 1.2 million on day 7 after the CDC’s Nov. 2 approval, but by day 18 the deficit was down to about 650,000, the CDC reported.

Altogether, just over 3 million children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, which is 10.7% of that age group’s total population. Among children aged 12-17, the proportions are 60.7% with at least one dose and 51.1% at full vaccination. Children aged 5-11, who make up 8.7% of the total U.S. population, represented 42.8% of all vaccinations initiated over the 2 weeks ending Nov. 21, compared with 4.2% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

There were almost 142,000 new cases reported during the week of Nov. 12-18, marking an increase of 16% over the previous week and the 15th straight week with a weekly total over 100,000, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said.

Regional data show that the Midwest has experienced the largest share of this latest surge, followed by the Northeast. Cases increased in the South during the week of Nov. 12-18 after holding steady over the previous 2 weeks, while new cases in the West dropped in the last week. At the state level, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont again reported the largest percent increases, with Michigan, Minnesota, and New Mexico also above average, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show similar trends for both emergency department visits and hospital admissions, as both have risen in November after declines that began in late August and early September.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is 6.77 million since the pandemic began, based on the AAP/CHA accounting of state cases, although Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer, suggesting the actual number is higher. The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 5.96 million, but there are age discrepancies between the CDC and the AAP/CHA’s state-based data.

The vaccine gap is closing

Vaccinations among the recently eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have steadily increased following a somewhat slow start. The initial pace was behind that of the 12- to 15-years-olds through the first postapproval week but has since closed the gap, based on data from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The tally of children who received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine among the 5- to 11-year-olds was behind the older group by almost 1.2 million on day 7 after the CDC’s Nov. 2 approval, but by day 18 the deficit was down to about 650,000, the CDC reported.

Altogether, just over 3 million children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, which is 10.7% of that age group’s total population. Among children aged 12-17, the proportions are 60.7% with at least one dose and 51.1% at full vaccination. Children aged 5-11, who make up 8.7% of the total U.S. population, represented 42.8% of all vaccinations initiated over the 2 weeks ending Nov. 21, compared with 4.2% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

There were almost 142,000 new cases reported during the week of Nov. 12-18, marking an increase of 16% over the previous week and the 15th straight week with a weekly total over 100,000, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said.

Regional data show that the Midwest has experienced the largest share of this latest surge, followed by the Northeast. Cases increased in the South during the week of Nov. 12-18 after holding steady over the previous 2 weeks, while new cases in the West dropped in the last week. At the state level, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont again reported the largest percent increases, with Michigan, Minnesota, and New Mexico also above average, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show similar trends for both emergency department visits and hospital admissions, as both have risen in November after declines that began in late August and early September.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is 6.77 million since the pandemic began, based on the AAP/CHA accounting of state cases, although Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer, suggesting the actual number is higher. The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 5.96 million, but there are age discrepancies between the CDC and the AAP/CHA’s state-based data.

The vaccine gap is closing

Vaccinations among the recently eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have steadily increased following a somewhat slow start. The initial pace was behind that of the 12- to 15-years-olds through the first postapproval week but has since closed the gap, based on data from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The tally of children who received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine among the 5- to 11-year-olds was behind the older group by almost 1.2 million on day 7 after the CDC’s Nov. 2 approval, but by day 18 the deficit was down to about 650,000, the CDC reported.

Altogether, just over 3 million children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, which is 10.7% of that age group’s total population. Among children aged 12-17, the proportions are 60.7% with at least one dose and 51.1% at full vaccination. Children aged 5-11, who make up 8.7% of the total U.S. population, represented 42.8% of all vaccinations initiated over the 2 weeks ending Nov. 21, compared with 4.2% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said.

Predicting cardiac shock mortality in the ICU

Addition of echocardiogram measurement of biventricular dysfunction improved the accuracy of prognosis among patients with cardiac shock (CS) in the cardiac intensive care unit.

In patients in the cardiac ICU with CS, biventricular dysfunction (BVD), as assessed using transthoracic echocardiography, improves clinical risk stratification when combined with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions shock stage.

No improvements in risk stratification was seen with patients with left or right ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD or RVSD) alone, according to an article published in the journal Chest.

Ventricular systolic dysfunction is commonly seen in patients who have suffered cardiac shock, most often on the left side. Although echocardiography is often performed on these patients during diagnosis, previous studies looking at ventricular dysfunction used invasive hemodynamic parameters, which made it challenging to incorporate their findings into general cardiac ICU practice.

Pinning down cardiac shock

Although treatment of acute MI and heart failure has improved greatly, particularly with the implementation of percutaneous coronary intervention (primary PCI) for ST-segment elevation MI. This has reduced the rate of future heart failure, but cardiac shock can occur before or after the procedure, with a 30-day mortality of 30%-40%. This outcome hasn’t improved in the last 20 years.

Efforts to improve cardiac shock outcomes through percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices have been hindered by the fact that CS patients are heterogeneous, and prognosis may depend on a range of factors.

SCAI was developed as a five-stage classification system for CS to improve communication of patient status, as well as to improve differentiation among patients participation in clinical trials. It does not include measures of ventricular dysfunction.

Simple measure boosts prognosis accuracy

The new work adds an additional layer to the SCAI shock stage. “Adding echocardiography allows discrimination between levels of risk for each SCAI stage,” said David Baran, MD, who was asked for comment. Dr. Baran was the lead author on the original SCAI study and is system director of advanced heart failure at Sentara Heart Hospital, as well as a professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School, both in Norfolk.

The work also underscores the value of repeated measures of prognosis during a patient’s stay in the ICU. “If a patient is not improving, it may prompt a consideration of whether transfer or consultation with a tertiary center may be of value. Conversely, if a patient doesn’t have high-risk features and is responding to therapy, it is reassuring to have data supporting low mortality with that care plan,” said Dr. Baran.

The study may be biased, since not every patient undergoes an echocardiogram. Still, “the authors make a convincing case that biventricular dysfunction is a powerful negative marker across the spectrum of SCAI stages,” said Dr. Baran.

Echocardiography is simple and generally available, and some are even portable and used with a smartphone. But patient body size interferes with echocardiography, as can the presence of a ventilator or multiple surgical dressings. “The key advantage of echo is that it is completely noninvasive and can be brought to the patient in the ICU, unlike other testing which involves moving the patient to the testing environment,” said Dr. Baran.

The researchers analyzed data from 3,158 patients admitted to the cardiac ICU at the Mayo Clinic Hospital St. Mary’s Campus in Rochester, Minn., 51.8% of whom had acute coronary syndromes. They defined LVSD as a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, and RVSD as at least moderate systolic dysfunction determined by semiquantitative measurement. BVD constituted the presence of both LVSD and RVSD. They examined the association of in-hospital mortality with these parameters combined with SCAI stage.

BVD a risk factor

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%. A total of 22.3% of patients had LVSD and 11.8% had RVSD; 16.4% had moderate or greater BVD. There was no association between LVSD or RVSD and in-hospital mortality after adjustment for SCAI stage, but there was a significant association for BVD (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.815; P = .0023). When combined with SCAI, BVC led to an improved ability to predict hospital mortality (area under the curve, 0.784 vs. 0.766; P < .001). Adding semiquantitative RVSD and LVSD led to more improvement (AUC, 0.794; P < .01 vs. both).

RVSD was associated with higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 1.421; P = .02), and there was a trend toward greater mortality with LVSD (aOR, 1.336; P = .06). There was little change when SCAI shock stage A patients were excluded (aOR, 1.840; P < .001).

Patients with BVD had greater in-hospital mortality than those without ventricular dysfunction (aOR, 1.815; P = .0023), but other between-group comparisons were not significant.

The researchers performed a classification and regression tree analysis using left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and semiquantitative RVSD. It found that RVSD was a better predictor of in-hospital mortality than LVSD, and the best cutoff for LVSD was different among patients with RVSD and patients without RVSD.

Patients with mild or greater RVD and LVEF greater than 24% were considered high risk; those with borderline or low RVSD and LVEF less than 33%, or mild or greater RVSD with LVEF of at least 24%, were considered intermediate risk. Patients with borderline or no RVSD and LVEF of at least 33% were considered low risk. Hospital mortality was 22% in the high-risk group, 12.2% in the intermediate group, and 3.3% in the low-risk group (aOR vs. intermediate, 0.493; P = .0006; aOR vs. high risk, 0.357; P < .0001).

The study authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Addition of echocardiogram measurement of biventricular dysfunction improved the accuracy of prognosis among patients with cardiac shock (CS) in the cardiac intensive care unit.

In patients in the cardiac ICU with CS, biventricular dysfunction (BVD), as assessed using transthoracic echocardiography, improves clinical risk stratification when combined with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions shock stage.

No improvements in risk stratification was seen with patients with left or right ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD or RVSD) alone, according to an article published in the journal Chest.

Ventricular systolic dysfunction is commonly seen in patients who have suffered cardiac shock, most often on the left side. Although echocardiography is often performed on these patients during diagnosis, previous studies looking at ventricular dysfunction used invasive hemodynamic parameters, which made it challenging to incorporate their findings into general cardiac ICU practice.

Pinning down cardiac shock

Although treatment of acute MI and heart failure has improved greatly, particularly with the implementation of percutaneous coronary intervention (primary PCI) for ST-segment elevation MI. This has reduced the rate of future heart failure, but cardiac shock can occur before or after the procedure, with a 30-day mortality of 30%-40%. This outcome hasn’t improved in the last 20 years.

Efforts to improve cardiac shock outcomes through percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices have been hindered by the fact that CS patients are heterogeneous, and prognosis may depend on a range of factors.

SCAI was developed as a five-stage classification system for CS to improve communication of patient status, as well as to improve differentiation among patients participation in clinical trials. It does not include measures of ventricular dysfunction.

Simple measure boosts prognosis accuracy

The new work adds an additional layer to the SCAI shock stage. “Adding echocardiography allows discrimination between levels of risk for each SCAI stage,” said David Baran, MD, who was asked for comment. Dr. Baran was the lead author on the original SCAI study and is system director of advanced heart failure at Sentara Heart Hospital, as well as a professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School, both in Norfolk.

The work also underscores the value of repeated measures of prognosis during a patient’s stay in the ICU. “If a patient is not improving, it may prompt a consideration of whether transfer or consultation with a tertiary center may be of value. Conversely, if a patient doesn’t have high-risk features and is responding to therapy, it is reassuring to have data supporting low mortality with that care plan,” said Dr. Baran.

The study may be biased, since not every patient undergoes an echocardiogram. Still, “the authors make a convincing case that biventricular dysfunction is a powerful negative marker across the spectrum of SCAI stages,” said Dr. Baran.

Echocardiography is simple and generally available, and some are even portable and used with a smartphone. But patient body size interferes with echocardiography, as can the presence of a ventilator or multiple surgical dressings. “The key advantage of echo is that it is completely noninvasive and can be brought to the patient in the ICU, unlike other testing which involves moving the patient to the testing environment,” said Dr. Baran.

The researchers analyzed data from 3,158 patients admitted to the cardiac ICU at the Mayo Clinic Hospital St. Mary’s Campus in Rochester, Minn., 51.8% of whom had acute coronary syndromes. They defined LVSD as a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, and RVSD as at least moderate systolic dysfunction determined by semiquantitative measurement. BVD constituted the presence of both LVSD and RVSD. They examined the association of in-hospital mortality with these parameters combined with SCAI stage.

BVD a risk factor

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%. A total of 22.3% of patients had LVSD and 11.8% had RVSD; 16.4% had moderate or greater BVD. There was no association between LVSD or RVSD and in-hospital mortality after adjustment for SCAI stage, but there was a significant association for BVD (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.815; P = .0023). When combined with SCAI, BVC led to an improved ability to predict hospital mortality (area under the curve, 0.784 vs. 0.766; P < .001). Adding semiquantitative RVSD and LVSD led to more improvement (AUC, 0.794; P < .01 vs. both).

RVSD was associated with higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 1.421; P = .02), and there was a trend toward greater mortality with LVSD (aOR, 1.336; P = .06). There was little change when SCAI shock stage A patients were excluded (aOR, 1.840; P < .001).

Patients with BVD had greater in-hospital mortality than those without ventricular dysfunction (aOR, 1.815; P = .0023), but other between-group comparisons were not significant.

The researchers performed a classification and regression tree analysis using left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and semiquantitative RVSD. It found that RVSD was a better predictor of in-hospital mortality than LVSD, and the best cutoff for LVSD was different among patients with RVSD and patients without RVSD.

Patients with mild or greater RVD and LVEF greater than 24% were considered high risk; those with borderline or low RVSD and LVEF less than 33%, or mild or greater RVSD with LVEF of at least 24%, were considered intermediate risk. Patients with borderline or no RVSD and LVEF of at least 33% were considered low risk. Hospital mortality was 22% in the high-risk group, 12.2% in the intermediate group, and 3.3% in the low-risk group (aOR vs. intermediate, 0.493; P = .0006; aOR vs. high risk, 0.357; P < .0001).

The study authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Addition of echocardiogram measurement of biventricular dysfunction improved the accuracy of prognosis among patients with cardiac shock (CS) in the cardiac intensive care unit.

In patients in the cardiac ICU with CS, biventricular dysfunction (BVD), as assessed using transthoracic echocardiography, improves clinical risk stratification when combined with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions shock stage.

No improvements in risk stratification was seen with patients with left or right ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD or RVSD) alone, according to an article published in the journal Chest.

Ventricular systolic dysfunction is commonly seen in patients who have suffered cardiac shock, most often on the left side. Although echocardiography is often performed on these patients during diagnosis, previous studies looking at ventricular dysfunction used invasive hemodynamic parameters, which made it challenging to incorporate their findings into general cardiac ICU practice.

Pinning down cardiac shock

Although treatment of acute MI and heart failure has improved greatly, particularly with the implementation of percutaneous coronary intervention (primary PCI) for ST-segment elevation MI. This has reduced the rate of future heart failure, but cardiac shock can occur before or after the procedure, with a 30-day mortality of 30%-40%. This outcome hasn’t improved in the last 20 years.

Efforts to improve cardiac shock outcomes through percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices have been hindered by the fact that CS patients are heterogeneous, and prognosis may depend on a range of factors.

SCAI was developed as a five-stage classification system for CS to improve communication of patient status, as well as to improve differentiation among patients participation in clinical trials. It does not include measures of ventricular dysfunction.

Simple measure boosts prognosis accuracy

The new work adds an additional layer to the SCAI shock stage. “Adding echocardiography allows discrimination between levels of risk for each SCAI stage,” said David Baran, MD, who was asked for comment. Dr. Baran was the lead author on the original SCAI study and is system director of advanced heart failure at Sentara Heart Hospital, as well as a professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School, both in Norfolk.

The work also underscores the value of repeated measures of prognosis during a patient’s stay in the ICU. “If a patient is not improving, it may prompt a consideration of whether transfer or consultation with a tertiary center may be of value. Conversely, if a patient doesn’t have high-risk features and is responding to therapy, it is reassuring to have data supporting low mortality with that care plan,” said Dr. Baran.

The study may be biased, since not every patient undergoes an echocardiogram. Still, “the authors make a convincing case that biventricular dysfunction is a powerful negative marker across the spectrum of SCAI stages,” said Dr. Baran.

Echocardiography is simple and generally available, and some are even portable and used with a smartphone. But patient body size interferes with echocardiography, as can the presence of a ventilator or multiple surgical dressings. “The key advantage of echo is that it is completely noninvasive and can be brought to the patient in the ICU, unlike other testing which involves moving the patient to the testing environment,” said Dr. Baran.

The researchers analyzed data from 3,158 patients admitted to the cardiac ICU at the Mayo Clinic Hospital St. Mary’s Campus in Rochester, Minn., 51.8% of whom had acute coronary syndromes. They defined LVSD as a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, and RVSD as at least moderate systolic dysfunction determined by semiquantitative measurement. BVD constituted the presence of both LVSD and RVSD. They examined the association of in-hospital mortality with these parameters combined with SCAI stage.

BVD a risk factor

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%. A total of 22.3% of patients had LVSD and 11.8% had RVSD; 16.4% had moderate or greater BVD. There was no association between LVSD or RVSD and in-hospital mortality after adjustment for SCAI stage, but there was a significant association for BVD (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.815; P = .0023). When combined with SCAI, BVC led to an improved ability to predict hospital mortality (area under the curve, 0.784 vs. 0.766; P < .001). Adding semiquantitative RVSD and LVSD led to more improvement (AUC, 0.794; P < .01 vs. both).

RVSD was associated with higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 1.421; P = .02), and there was a trend toward greater mortality with LVSD (aOR, 1.336; P = .06). There was little change when SCAI shock stage A patients were excluded (aOR, 1.840; P < .001).

Patients with BVD had greater in-hospital mortality than those without ventricular dysfunction (aOR, 1.815; P = .0023), but other between-group comparisons were not significant.

The researchers performed a classification and regression tree analysis using left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and semiquantitative RVSD. It found that RVSD was a better predictor of in-hospital mortality than LVSD, and the best cutoff for LVSD was different among patients with RVSD and patients without RVSD.

Patients with mild or greater RVD and LVEF greater than 24% were considered high risk; those with borderline or low RVSD and LVEF less than 33%, or mild or greater RVSD with LVEF of at least 24%, were considered intermediate risk. Patients with borderline or no RVSD and LVEF of at least 33% were considered low risk. Hospital mortality was 22% in the high-risk group, 12.2% in the intermediate group, and 3.3% in the low-risk group (aOR vs. intermediate, 0.493; P = .0006; aOR vs. high risk, 0.357; P < .0001).

The study authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps lowers QoL in COPD

Concomitant rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (RSsNP) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with a poorer, disease-specific, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a Norwegian study is showing.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis has an impact on patients’ HRQoL,” lead author Marte Rystad Øie, Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“We found that RSsNP in COPD was associated with more psychological issues, higher COPD symptom burden, and overall COPD-related HRQoL after adjusting for lung function, so RSsNP does have clinical relevance and [our findings] support previous studies that have suggested that rhinosinusitis should be recognized as a comorbidity in COPD,” she emphasized.

The study was published in the Nov. 1 issue of Respiratory Medicine.

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 90 patients with COPD and 93 control subjects, all age 40-80 years. “Generic HRQoL was measured with the Norwegian version of the SF-36v2 Health Survey Standard questionnaire,” the authors wrote, and responses were compared between patients with COPD and controls as well as between subgroups of patients who had COPD both with and without RSsNP.

Disease-specific HRQoL was assessed by the Sinonasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22); the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), and responses were again compared between patients who had COPD with and without RSsNP. In the COPD group, “severe” and “very severe” airflow obstruction was present in 56.5% of patients with RSsNP compared with 38.6% of patients without RSsNP, as Ms. Øie reported.

Furthermore, total SNOT-22 along with psychological subscale scores were both significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without RSsNP. Among those with RSsNP, the mean value of the total SNOT-22 score was 36.8 whereas the mean value of the psychological subscale score was 22.6. Comparable mean values among patients who had COPD without RSsNP were 9.5 and 6.5, respectively (P < .05).

Total scores on the SGRQ were again significantly greater in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 43.3 compared with a mean of 34 in those without RSsNP, investigators observe. Similarly, scores for the symptom and activity domains again on the SGRQ were significantly greater for patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without nasal polyps. As for the total CAT score, once again it was significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 18.8 compared with a mean of 13.5 in those without RSsNP (P < .05).

Indeed, patients with RSsNP were four times more likely to have CAT scores indicating the condition was having a high or very high impact on their HRQoL compared with patients without RSsNP (P < .001). As the authors pointed out, having a high impact on HRQoL translates into patients having to stop their desired activities and having no good days in the week.

“This suggests that having RSsNP substantially adds to the activity limitation experienced by patients with COPD,” they emphasized. The authors also found that RSsNP was significantly associated with poorer physical functioning after adjusting for COPD as reflected by SF-36v2 findings, again suggesting that patients who had COPD with concomitant RSsNP have an additional limitation in activity and a heavier symptom burden.

As Ms. Øie explained, rhinosinusitis has two clinical phenotypes: that with nasal polyps and that without nasal polyps, the latter being twice as prevalent. In fact, rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is associated with asthma, as she pointed out. Given, however, that rhinosinusitis without polyps is amenable to treatment with daily use of nasal steroids, it is possible to reduce the burden of symptoms and psychological stress associated with RSsNP in COPD.

Limitations of the study include the fact that investigators did not assess patients for the presence of any comorbidities that could contribute to poorer HRQoL in this patient population.

The study was funded by Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Concomitant rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (RSsNP) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with a poorer, disease-specific, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a Norwegian study is showing.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis has an impact on patients’ HRQoL,” lead author Marte Rystad Øie, Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“We found that RSsNP in COPD was associated with more psychological issues, higher COPD symptom burden, and overall COPD-related HRQoL after adjusting for lung function, so RSsNP does have clinical relevance and [our findings] support previous studies that have suggested that rhinosinusitis should be recognized as a comorbidity in COPD,” she emphasized.

The study was published in the Nov. 1 issue of Respiratory Medicine.

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 90 patients with COPD and 93 control subjects, all age 40-80 years. “Generic HRQoL was measured with the Norwegian version of the SF-36v2 Health Survey Standard questionnaire,” the authors wrote, and responses were compared between patients with COPD and controls as well as between subgroups of patients who had COPD both with and without RSsNP.

Disease-specific HRQoL was assessed by the Sinonasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22); the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), and responses were again compared between patients who had COPD with and without RSsNP. In the COPD group, “severe” and “very severe” airflow obstruction was present in 56.5% of patients with RSsNP compared with 38.6% of patients without RSsNP, as Ms. Øie reported.

Furthermore, total SNOT-22 along with psychological subscale scores were both significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without RSsNP. Among those with RSsNP, the mean value of the total SNOT-22 score was 36.8 whereas the mean value of the psychological subscale score was 22.6. Comparable mean values among patients who had COPD without RSsNP were 9.5 and 6.5, respectively (P < .05).

Total scores on the SGRQ were again significantly greater in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 43.3 compared with a mean of 34 in those without RSsNP, investigators observe. Similarly, scores for the symptom and activity domains again on the SGRQ were significantly greater for patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without nasal polyps. As for the total CAT score, once again it was significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 18.8 compared with a mean of 13.5 in those without RSsNP (P < .05).

Indeed, patients with RSsNP were four times more likely to have CAT scores indicating the condition was having a high or very high impact on their HRQoL compared with patients without RSsNP (P < .001). As the authors pointed out, having a high impact on HRQoL translates into patients having to stop their desired activities and having no good days in the week.

“This suggests that having RSsNP substantially adds to the activity limitation experienced by patients with COPD,” they emphasized. The authors also found that RSsNP was significantly associated with poorer physical functioning after adjusting for COPD as reflected by SF-36v2 findings, again suggesting that patients who had COPD with concomitant RSsNP have an additional limitation in activity and a heavier symptom burden.

As Ms. Øie explained, rhinosinusitis has two clinical phenotypes: that with nasal polyps and that without nasal polyps, the latter being twice as prevalent. In fact, rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is associated with asthma, as she pointed out. Given, however, that rhinosinusitis without polyps is amenable to treatment with daily use of nasal steroids, it is possible to reduce the burden of symptoms and psychological stress associated with RSsNP in COPD.

Limitations of the study include the fact that investigators did not assess patients for the presence of any comorbidities that could contribute to poorer HRQoL in this patient population.

The study was funded by Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Concomitant rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps (RSsNP) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with a poorer, disease-specific, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), a Norwegian study is showing.

“Chronic rhinosinusitis has an impact on patients’ HRQoL,” lead author Marte Rystad Øie, Trondheim (Norway) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“We found that RSsNP in COPD was associated with more psychological issues, higher COPD symptom burden, and overall COPD-related HRQoL after adjusting for lung function, so RSsNP does have clinical relevance and [our findings] support previous studies that have suggested that rhinosinusitis should be recognized as a comorbidity in COPD,” she emphasized.

The study was published in the Nov. 1 issue of Respiratory Medicine.

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 90 patients with COPD and 93 control subjects, all age 40-80 years. “Generic HRQoL was measured with the Norwegian version of the SF-36v2 Health Survey Standard questionnaire,” the authors wrote, and responses were compared between patients with COPD and controls as well as between subgroups of patients who had COPD both with and without RSsNP.

Disease-specific HRQoL was assessed by the Sinonasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22); the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), and responses were again compared between patients who had COPD with and without RSsNP. In the COPD group, “severe” and “very severe” airflow obstruction was present in 56.5% of patients with RSsNP compared with 38.6% of patients without RSsNP, as Ms. Øie reported.

Furthermore, total SNOT-22 along with psychological subscale scores were both significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without RSsNP. Among those with RSsNP, the mean value of the total SNOT-22 score was 36.8 whereas the mean value of the psychological subscale score was 22.6. Comparable mean values among patients who had COPD without RSsNP were 9.5 and 6.5, respectively (P < .05).

Total scores on the SGRQ were again significantly greater in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 43.3 compared with a mean of 34 in those without RSsNP, investigators observe. Similarly, scores for the symptom and activity domains again on the SGRQ were significantly greater for patients who had COPD with RSsNP than those without nasal polyps. As for the total CAT score, once again it was significantly higher in patients who had COPD with RSsNP at a mean of 18.8 compared with a mean of 13.5 in those without RSsNP (P < .05).

Indeed, patients with RSsNP were four times more likely to have CAT scores indicating the condition was having a high or very high impact on their HRQoL compared with patients without RSsNP (P < .001). As the authors pointed out, having a high impact on HRQoL translates into patients having to stop their desired activities and having no good days in the week.

“This suggests that having RSsNP substantially adds to the activity limitation experienced by patients with COPD,” they emphasized. The authors also found that RSsNP was significantly associated with poorer physical functioning after adjusting for COPD as reflected by SF-36v2 findings, again suggesting that patients who had COPD with concomitant RSsNP have an additional limitation in activity and a heavier symptom burden.

As Ms. Øie explained, rhinosinusitis has two clinical phenotypes: that with nasal polyps and that without nasal polyps, the latter being twice as prevalent. In fact, rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is associated with asthma, as she pointed out. Given, however, that rhinosinusitis without polyps is amenable to treatment with daily use of nasal steroids, it is possible to reduce the burden of symptoms and psychological stress associated with RSsNP in COPD.

Limitations of the study include the fact that investigators did not assess patients for the presence of any comorbidities that could contribute to poorer HRQoL in this patient population.

The study was funded by Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID surge in Europe: A preview of what’s ahead for the U.S.?

Health experts are warning the United States could be headed for another COVID-19 surge just as we enter the holiday season, following a massive new wave of infections in Europe – a troubling pattern seen throughout the pandemic.

Eighteen months into the global health crisis that has killed 5.1 million people worldwide including more than 767,000 Americans, Europe has become the epicenter of the global health crisis once again.

And some infectious disease specialists say the United States may be next.

“It’s déjà vu, yet again,” says Eric Topol, M.D., founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. In a new analysis published in The Guardian, the professor of molecular medicine argues that it’s “wishful thinking” for U.S. authorities to believe the nation is “immune” to what’s happening in Europe.

Dr. Topol is also editor-in-chief of Medscape, MDedge’s sister site for medical professionals.

Three times over the past 18 months coronavirus surges in the United States followed similar spikes in Europe, where COVID-19 deaths grew by 10% this month.

Dr. Topol argues another wave may be in store for the states, as European countries implement new lockdowns. COVID-19 spikes are hitting some regions of the continent hard, including areas with high vaccination rates and strict control measures.

Eastern Europe and Russia, where vaccination rates are low, have experienced the worst of it. But even western countries, such as Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom, are reporting some of the highest daily infection figures in the world today.

Countries are responding in increasingly drastic ways.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin ordered tens of thousands of workers to stay home earlier this month.

In the Dutch city of Utrecht, traditional Christmas celebrations have been canceled as the country is headed for a partial lockdown.

Austria announced a 20-day lockdown beginning Nov. 22 and on Nov. 19 leaders there announced that all 9 million residents will be required to be vaccinated by February. Leaders there are telling unvaccinated individuals to stay at home and out of restaurants, cafes, and other shops in hard-hit regions of the country.

And in Germany, where daily new-infection rates now stand at 50,000, officials have introduced stricter mask mandates and made proof of vaccination or past infection mandatory for entry to many venues. Berlin is also eyeing proposals to shut down the city’s traditional Christmas markets while authorities in Cologne have already called off holiday celebrations, after the ceremonial head of festivities tested positive for COVID-19. Bavaria canceled its popular Christmas markets and will order lockdowns in particularly vulnerable districts, while unvaccinated people will face serious restrictions on where they can go.

Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, says what’s happening across the European continent is troubling.

But he also believes it’s possible the United States may be better prepared to head off a similar surge this time around, with increased testing, vaccination and new therapies such as monoclonal antibodies, and antiviral therapeutics.

“Germany’s challenges are [a] caution to [the] world, the COVID pandemic isn’t over globally, won’t be for long time,” he says. “But [the] U.S. is further along than many other countries, in part because we already suffered more spread, in part because we’re making progress on vaccines, therapeutics, testing.”

Other experts agree the United States may not be as vulnerable to another wave of COVID-19 in coming weeks but have stopped short of suggesting we’re out of the woods.

“I don’t think that what we’re seeing in Europe necessarily means that we’re in for a huge surge of serious illness and death the way that we saw last year here in the states,” says David Dowdy, MD, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a general internist with Baltimore Medical Services.

“But I think anyone who says that they can predict the course of the pandemic for the next few months or few years has been proven wrong in the past and will probably be proven wrong in the future,” Dr. Dowdy says. “None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness.”

Looking back, and forward

What’s happening in Europe today mirrors past COVID-19 spikes that presaged big upticks in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States.

When the pandemic first hit Europe in March 2020, then-President Donald Trump downplayed the threat of the virus despite the warnings of his own advisors and independent public health experts who said COVID-19 could have dire impacts without an aggressive federal action plan.

By late spring the United States had become the epicenter of the pandemic, when case totals eclipsed those of other countries and New York City became a hot zone, according to data compiled by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Over the summer, spread of the disease slowed in New York, after tough control measures were instituted, but steadily increased in other states.

Then, later in the year, the Alpha variant of the virus took hold in the United Kingdom and the United States was again unprepared. By winter, the number of cases accelerated in every state in a major second surge that kept millions of Americans from traveling and gathering for the winter holidays.

With the rollout of COVID vaccines last December, cases in the United States – and in many parts of the world – began to fall. Some experts even suggested we’d turned a corner on the pandemic.

But then, last spring and summer, the Delta variant popped up in India and spread to the United Kingdom in a third major wave of COVID. Once again, the United States was unprepared, with 4 in 10 Americans refusing the vaccine and even some vaccinated individuals succumbing to breakthrough Delta infections.

The resulting Delta surge swept the country, preventing many businesses and schools from fully reopening and stressing hospitals in some areas of the country – particularly southern states – with new influxes of COVID-19 patients.

Now, Europe is facing another rise in COVID, with about 350 cases per 100,000 people and many countries hitting new record highs.

What’s driving the European resurgence?

So, what’s behind the new COVID-19 wave in Europe and what might it mean for the United States?

Shaun Truelove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and faculty member of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, says experts are examining several likely factors:

Waning immunity from the vaccines. Data from Johns Hopkins shows infections rising in nations with lower vaccination rates.

The impact of the Delta variant, which is three times more transmissible than the original virus and can even sicken some vaccinated individuals.

The spread of COVID-19 among teens and children; the easing of precautions (such as masking and social distancing); differences in the types of vaccines used in European nations and the United States.

“These are all possibilities,” says Dr. Truelove. “There are so many factors and so it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what’s driving it and what effect each of those things might be having.”

As a result, it’s difficult to predict and prepare for what might lie ahead for the United States, he says.

“There’s a ton of uncertainty and we’re trying to understand what’s going to happen here over the next 6 months,” he says.

Even so, Dr. Truelove adds that what’s happening overseas might not be “super predictive” of a new wave of COVID in the United States.

For one thing, he says, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the two mRNA vaccines used predominantly in the United States, are far more effective – 94-95% – than the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID shot (63%) widely administered across Europe.

Secondly, European countries have imposed much stronger and stricter control measures throughout the pandemic than the United States. That might actually be driving the new surges because fewer unvaccinated people have been exposed to the virus, which means they have lower “natural immunity” from prior COVID infection.

Dr. Truelove explains: “Stronger and stricter control measures … have the consequence of leaving a lot more susceptible individuals in the population, [because] the stronger the controls, the fewer people get infected. And so, you have more individuals remaining in the population who are more susceptible and at risk of getting infected in the future.”

By contrast, he notes, a “large chunk” of the United States has not put strict lockdowns in place.

“So, what we’ve seen over the past couple months with the Delta wave is that in a lot of those states with lower vaccination coverage and lower controls this virus has really burned through a lot of the susceptible population. As a result, we’re seeing the curves coming down and what really looks like a lot of the built-up immunity in these states, especially southern states.”

But whether these differences will be enough for the United States to dodge another COVID-19 bullet this winter is uncertain.

“I don’t want to say that the [Europe] surge is NOT a predictor of what might come in the U.S., because I think that it very well could be,” Dr. Truelove says. “And so, people need to be aware of that, and be cautious and be sure get their vaccines and everything else.

“But I’m hopeful that because of some of the differences that maybe we’ll have a little bit of a different situation.”

The takeaway: How best to prepare?

Dr. Dowdy agrees that Europe’s current troubles might not necessarily mean a major new winter surge in the United States.

But he also points out that cases are beginning to head up again in New England, the Midwest, and other regions of the country that are just experiencing the first chill of winter.

“After reaching a low point about 3 weeks ago, cases due to COVID-19 have started to rise again in the United States,” he says. “Cases were falling consistently until mid-October, but over the last 3 weeks, cases have started to rise again in most states.

“Cases in Eastern and Central Europe have more than doubled during that time, meaning that the possibility of a winter surge here is very real.”

Even so, Dr. Dowdy believes the rising rates of vaccination could limit the number of Americans who will be hospitalized with severe disease or die this winter.

Still, he warns against being too optimistic, as Americans travel and get together for the winter holidays.

None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness, Dr. Dowdy says.”

The upshot?

“People need to realize that it’s not quite over,” Dr. Truelove says. “We still have a substantial amount of infection in our country. We’re still above 200 cases per million [and] 500,000 incident cases per week or so. That’s a lot of death and a lot of hospitalizations. So, we still have to be concerned and do our best to reduce transmission … by wearing masks, getting vaccinated, getting a booster shot, and getting your children vaccinated.”

Johns Hopkins social and behavioral scientist Rupali Limaye, PhD, MPH, adds that while COVID vaccines have been a “game changer” in the pandemic, more than a third of Americans have yet to receive one.

“That’s really what we need to be messaging around -- that people can still get COVID, there can still be breakthrough infections,” says Dr. Limaye, a health communications scholar. “But the great news is if you have been vaccinated, you are very much less likely, I think it’s 12 times, to be hospitalized or have severe COVID compared to those that are un-vaccinated.”

Dr. Topol agrees, adding: “Now is the time for the U.S. to heed the European signal for the first time, to pull out all the stops. Promote primary vaccination and boosters like there’s no tomorrow. Aggressively counter the pervasive misinformation and disinformation. Accelerate and expand the vaccine mandates ...

“Instead of succumbing to yet another major rise in cases and their sequelae, this is a chance for America to finally rise to the occasion, showing an ability to lead and execute.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Health experts are warning the United States could be headed for another COVID-19 surge just as we enter the holiday season, following a massive new wave of infections in Europe – a troubling pattern seen throughout the pandemic.

Eighteen months into the global health crisis that has killed 5.1 million people worldwide including more than 767,000 Americans, Europe has become the epicenter of the global health crisis once again.

And some infectious disease specialists say the United States may be next.

“It’s déjà vu, yet again,” says Eric Topol, M.D., founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. In a new analysis published in The Guardian, the professor of molecular medicine argues that it’s “wishful thinking” for U.S. authorities to believe the nation is “immune” to what’s happening in Europe.

Dr. Topol is also editor-in-chief of Medscape, MDedge’s sister site for medical professionals.

Three times over the past 18 months coronavirus surges in the United States followed similar spikes in Europe, where COVID-19 deaths grew by 10% this month.

Dr. Topol argues another wave may be in store for the states, as European countries implement new lockdowns. COVID-19 spikes are hitting some regions of the continent hard, including areas with high vaccination rates and strict control measures.

Eastern Europe and Russia, where vaccination rates are low, have experienced the worst of it. But even western countries, such as Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom, are reporting some of the highest daily infection figures in the world today.

Countries are responding in increasingly drastic ways.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin ordered tens of thousands of workers to stay home earlier this month.

In the Dutch city of Utrecht, traditional Christmas celebrations have been canceled as the country is headed for a partial lockdown.

Austria announced a 20-day lockdown beginning Nov. 22 and on Nov. 19 leaders there announced that all 9 million residents will be required to be vaccinated by February. Leaders there are telling unvaccinated individuals to stay at home and out of restaurants, cafes, and other shops in hard-hit regions of the country.

And in Germany, where daily new-infection rates now stand at 50,000, officials have introduced stricter mask mandates and made proof of vaccination or past infection mandatory for entry to many venues. Berlin is also eyeing proposals to shut down the city’s traditional Christmas markets while authorities in Cologne have already called off holiday celebrations, after the ceremonial head of festivities tested positive for COVID-19. Bavaria canceled its popular Christmas markets and will order lockdowns in particularly vulnerable districts, while unvaccinated people will face serious restrictions on where they can go.

Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, says what’s happening across the European continent is troubling.

But he also believes it’s possible the United States may be better prepared to head off a similar surge this time around, with increased testing, vaccination and new therapies such as monoclonal antibodies, and antiviral therapeutics.

“Germany’s challenges are [a] caution to [the] world, the COVID pandemic isn’t over globally, won’t be for long time,” he says. “But [the] U.S. is further along than many other countries, in part because we already suffered more spread, in part because we’re making progress on vaccines, therapeutics, testing.”

Other experts agree the United States may not be as vulnerable to another wave of COVID-19 in coming weeks but have stopped short of suggesting we’re out of the woods.

“I don’t think that what we’re seeing in Europe necessarily means that we’re in for a huge surge of serious illness and death the way that we saw last year here in the states,” says David Dowdy, MD, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a general internist with Baltimore Medical Services.

“But I think anyone who says that they can predict the course of the pandemic for the next few months or few years has been proven wrong in the past and will probably be proven wrong in the future,” Dr. Dowdy says. “None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness.”

Looking back, and forward

What’s happening in Europe today mirrors past COVID-19 spikes that presaged big upticks in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States.

When the pandemic first hit Europe in March 2020, then-President Donald Trump downplayed the threat of the virus despite the warnings of his own advisors and independent public health experts who said COVID-19 could have dire impacts without an aggressive federal action plan.

By late spring the United States had become the epicenter of the pandemic, when case totals eclipsed those of other countries and New York City became a hot zone, according to data compiled by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Over the summer, spread of the disease slowed in New York, after tough control measures were instituted, but steadily increased in other states.

Then, later in the year, the Alpha variant of the virus took hold in the United Kingdom and the United States was again unprepared. By winter, the number of cases accelerated in every state in a major second surge that kept millions of Americans from traveling and gathering for the winter holidays.

With the rollout of COVID vaccines last December, cases in the United States – and in many parts of the world – began to fall. Some experts even suggested we’d turned a corner on the pandemic.

But then, last spring and summer, the Delta variant popped up in India and spread to the United Kingdom in a third major wave of COVID. Once again, the United States was unprepared, with 4 in 10 Americans refusing the vaccine and even some vaccinated individuals succumbing to breakthrough Delta infections.

The resulting Delta surge swept the country, preventing many businesses and schools from fully reopening and stressing hospitals in some areas of the country – particularly southern states – with new influxes of COVID-19 patients.

Now, Europe is facing another rise in COVID, with about 350 cases per 100,000 people and many countries hitting new record highs.

What’s driving the European resurgence?

So, what’s behind the new COVID-19 wave in Europe and what might it mean for the United States?

Shaun Truelove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and faculty member of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, says experts are examining several likely factors:

Waning immunity from the vaccines. Data from Johns Hopkins shows infections rising in nations with lower vaccination rates.

The impact of the Delta variant, which is three times more transmissible than the original virus and can even sicken some vaccinated individuals.

The spread of COVID-19 among teens and children; the easing of precautions (such as masking and social distancing); differences in the types of vaccines used in European nations and the United States.

“These are all possibilities,” says Dr. Truelove. “There are so many factors and so it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what’s driving it and what effect each of those things might be having.”

As a result, it’s difficult to predict and prepare for what might lie ahead for the United States, he says.

“There’s a ton of uncertainty and we’re trying to understand what’s going to happen here over the next 6 months,” he says.

Even so, Dr. Truelove adds that what’s happening overseas might not be “super predictive” of a new wave of COVID in the United States.

For one thing, he says, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the two mRNA vaccines used predominantly in the United States, are far more effective – 94-95% – than the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID shot (63%) widely administered across Europe.

Secondly, European countries have imposed much stronger and stricter control measures throughout the pandemic than the United States. That might actually be driving the new surges because fewer unvaccinated people have been exposed to the virus, which means they have lower “natural immunity” from prior COVID infection.

Dr. Truelove explains: “Stronger and stricter control measures … have the consequence of leaving a lot more susceptible individuals in the population, [because] the stronger the controls, the fewer people get infected. And so, you have more individuals remaining in the population who are more susceptible and at risk of getting infected in the future.”

By contrast, he notes, a “large chunk” of the United States has not put strict lockdowns in place.

“So, what we’ve seen over the past couple months with the Delta wave is that in a lot of those states with lower vaccination coverage and lower controls this virus has really burned through a lot of the susceptible population. As a result, we’re seeing the curves coming down and what really looks like a lot of the built-up immunity in these states, especially southern states.”

But whether these differences will be enough for the United States to dodge another COVID-19 bullet this winter is uncertain.

“I don’t want to say that the [Europe] surge is NOT a predictor of what might come in the U.S., because I think that it very well could be,” Dr. Truelove says. “And so, people need to be aware of that, and be cautious and be sure get their vaccines and everything else.

“But I’m hopeful that because of some of the differences that maybe we’ll have a little bit of a different situation.”

The takeaway: How best to prepare?

Dr. Dowdy agrees that Europe’s current troubles might not necessarily mean a major new winter surge in the United States.

But he also points out that cases are beginning to head up again in New England, the Midwest, and other regions of the country that are just experiencing the first chill of winter.

“After reaching a low point about 3 weeks ago, cases due to COVID-19 have started to rise again in the United States,” he says. “Cases were falling consistently until mid-October, but over the last 3 weeks, cases have started to rise again in most states.

“Cases in Eastern and Central Europe have more than doubled during that time, meaning that the possibility of a winter surge here is very real.”

Even so, Dr. Dowdy believes the rising rates of vaccination could limit the number of Americans who will be hospitalized with severe disease or die this winter.

Still, he warns against being too optimistic, as Americans travel and get together for the winter holidays.

None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness, Dr. Dowdy says.”

The upshot?

“People need to realize that it’s not quite over,” Dr. Truelove says. “We still have a substantial amount of infection in our country. We’re still above 200 cases per million [and] 500,000 incident cases per week or so. That’s a lot of death and a lot of hospitalizations. So, we still have to be concerned and do our best to reduce transmission … by wearing masks, getting vaccinated, getting a booster shot, and getting your children vaccinated.”

Johns Hopkins social and behavioral scientist Rupali Limaye, PhD, MPH, adds that while COVID vaccines have been a “game changer” in the pandemic, more than a third of Americans have yet to receive one.

“That’s really what we need to be messaging around -- that people can still get COVID, there can still be breakthrough infections,” says Dr. Limaye, a health communications scholar. “But the great news is if you have been vaccinated, you are very much less likely, I think it’s 12 times, to be hospitalized or have severe COVID compared to those that are un-vaccinated.”

Dr. Topol agrees, adding: “Now is the time for the U.S. to heed the European signal for the first time, to pull out all the stops. Promote primary vaccination and boosters like there’s no tomorrow. Aggressively counter the pervasive misinformation and disinformation. Accelerate and expand the vaccine mandates ...

“Instead of succumbing to yet another major rise in cases and their sequelae, this is a chance for America to finally rise to the occasion, showing an ability to lead and execute.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Health experts are warning the United States could be headed for another COVID-19 surge just as we enter the holiday season, following a massive new wave of infections in Europe – a troubling pattern seen throughout the pandemic.

Eighteen months into the global health crisis that has killed 5.1 million people worldwide including more than 767,000 Americans, Europe has become the epicenter of the global health crisis once again.

And some infectious disease specialists say the United States may be next.

“It’s déjà vu, yet again,” says Eric Topol, M.D., founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. In a new analysis published in The Guardian, the professor of molecular medicine argues that it’s “wishful thinking” for U.S. authorities to believe the nation is “immune” to what’s happening in Europe.

Dr. Topol is also editor-in-chief of Medscape, MDedge’s sister site for medical professionals.

Three times over the past 18 months coronavirus surges in the United States followed similar spikes in Europe, where COVID-19 deaths grew by 10% this month.

Dr. Topol argues another wave may be in store for the states, as European countries implement new lockdowns. COVID-19 spikes are hitting some regions of the continent hard, including areas with high vaccination rates and strict control measures.

Eastern Europe and Russia, where vaccination rates are low, have experienced the worst of it. But even western countries, such as Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom, are reporting some of the highest daily infection figures in the world today.

Countries are responding in increasingly drastic ways.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin ordered tens of thousands of workers to stay home earlier this month.

In the Dutch city of Utrecht, traditional Christmas celebrations have been canceled as the country is headed for a partial lockdown.

Austria announced a 20-day lockdown beginning Nov. 22 and on Nov. 19 leaders there announced that all 9 million residents will be required to be vaccinated by February. Leaders there are telling unvaccinated individuals to stay at home and out of restaurants, cafes, and other shops in hard-hit regions of the country.

And in Germany, where daily new-infection rates now stand at 50,000, officials have introduced stricter mask mandates and made proof of vaccination or past infection mandatory for entry to many venues. Berlin is also eyeing proposals to shut down the city’s traditional Christmas markets while authorities in Cologne have already called off holiday celebrations, after the ceremonial head of festivities tested positive for COVID-19. Bavaria canceled its popular Christmas markets and will order lockdowns in particularly vulnerable districts, while unvaccinated people will face serious restrictions on where they can go.

Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, says what’s happening across the European continent is troubling.

But he also believes it’s possible the United States may be better prepared to head off a similar surge this time around, with increased testing, vaccination and new therapies such as monoclonal antibodies, and antiviral therapeutics.

“Germany’s challenges are [a] caution to [the] world, the COVID pandemic isn’t over globally, won’t be for long time,” he says. “But [the] U.S. is further along than many other countries, in part because we already suffered more spread, in part because we’re making progress on vaccines, therapeutics, testing.”

Other experts agree the United States may not be as vulnerable to another wave of COVID-19 in coming weeks but have stopped short of suggesting we’re out of the woods.

“I don’t think that what we’re seeing in Europe necessarily means that we’re in for a huge surge of serious illness and death the way that we saw last year here in the states,” says David Dowdy, MD, PhD, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a general internist with Baltimore Medical Services.

“But I think anyone who says that they can predict the course of the pandemic for the next few months or few years has been proven wrong in the past and will probably be proven wrong in the future,” Dr. Dowdy says. “None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness.”

Looking back, and forward

What’s happening in Europe today mirrors past COVID-19 spikes that presaged big upticks in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States.

When the pandemic first hit Europe in March 2020, then-President Donald Trump downplayed the threat of the virus despite the warnings of his own advisors and independent public health experts who said COVID-19 could have dire impacts without an aggressive federal action plan.

By late spring the United States had become the epicenter of the pandemic, when case totals eclipsed those of other countries and New York City became a hot zone, according to data compiled by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Over the summer, spread of the disease slowed in New York, after tough control measures were instituted, but steadily increased in other states.

Then, later in the year, the Alpha variant of the virus took hold in the United Kingdom and the United States was again unprepared. By winter, the number of cases accelerated in every state in a major second surge that kept millions of Americans from traveling and gathering for the winter holidays.

With the rollout of COVID vaccines last December, cases in the United States – and in many parts of the world – began to fall. Some experts even suggested we’d turned a corner on the pandemic.

But then, last spring and summer, the Delta variant popped up in India and spread to the United Kingdom in a third major wave of COVID. Once again, the United States was unprepared, with 4 in 10 Americans refusing the vaccine and even some vaccinated individuals succumbing to breakthrough Delta infections.

The resulting Delta surge swept the country, preventing many businesses and schools from fully reopening and stressing hospitals in some areas of the country – particularly southern states – with new influxes of COVID-19 patients.

Now, Europe is facing another rise in COVID, with about 350 cases per 100,000 people and many countries hitting new record highs.

What’s driving the European resurgence?

So, what’s behind the new COVID-19 wave in Europe and what might it mean for the United States?

Shaun Truelove, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist and faculty member of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, says experts are examining several likely factors:

Waning immunity from the vaccines. Data from Johns Hopkins shows infections rising in nations with lower vaccination rates.

The impact of the Delta variant, which is three times more transmissible than the original virus and can even sicken some vaccinated individuals.

The spread of COVID-19 among teens and children; the easing of precautions (such as masking and social distancing); differences in the types of vaccines used in European nations and the United States.

“These are all possibilities,” says Dr. Truelove. “There are so many factors and so it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what’s driving it and what effect each of those things might be having.”

As a result, it’s difficult to predict and prepare for what might lie ahead for the United States, he says.

“There’s a ton of uncertainty and we’re trying to understand what’s going to happen here over the next 6 months,” he says.

Even so, Dr. Truelove adds that what’s happening overseas might not be “super predictive” of a new wave of COVID in the United States.

For one thing, he says, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the two mRNA vaccines used predominantly in the United States, are far more effective – 94-95% – than the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID shot (63%) widely administered across Europe.

Secondly, European countries have imposed much stronger and stricter control measures throughout the pandemic than the United States. That might actually be driving the new surges because fewer unvaccinated people have been exposed to the virus, which means they have lower “natural immunity” from prior COVID infection.

Dr. Truelove explains: “Stronger and stricter control measures … have the consequence of leaving a lot more susceptible individuals in the population, [because] the stronger the controls, the fewer people get infected. And so, you have more individuals remaining in the population who are more susceptible and at risk of getting infected in the future.”

By contrast, he notes, a “large chunk” of the United States has not put strict lockdowns in place.

“So, what we’ve seen over the past couple months with the Delta wave is that in a lot of those states with lower vaccination coverage and lower controls this virus has really burned through a lot of the susceptible population. As a result, we’re seeing the curves coming down and what really looks like a lot of the built-up immunity in these states, especially southern states.”

But whether these differences will be enough for the United States to dodge another COVID-19 bullet this winter is uncertain.

“I don’t want to say that the [Europe] surge is NOT a predictor of what might come in the U.S., because I think that it very well could be,” Dr. Truelove says. “And so, people need to be aware of that, and be cautious and be sure get their vaccines and everything else.

“But I’m hopeful that because of some of the differences that maybe we’ll have a little bit of a different situation.”

The takeaway: How best to prepare?

Dr. Dowdy agrees that Europe’s current troubles might not necessarily mean a major new winter surge in the United States.

But he also points out that cases are beginning to head up again in New England, the Midwest, and other regions of the country that are just experiencing the first chill of winter.

“After reaching a low point about 3 weeks ago, cases due to COVID-19 have started to rise again in the United States,” he says. “Cases were falling consistently until mid-October, but over the last 3 weeks, cases have started to rise again in most states.

“Cases in Eastern and Central Europe have more than doubled during that time, meaning that the possibility of a winter surge here is very real.”

Even so, Dr. Dowdy believes the rising rates of vaccination could limit the number of Americans who will be hospitalized with severe disease or die this winter.

Still, he warns against being too optimistic, as Americans travel and get together for the winter holidays.

None of us knows the future of this pandemic, but I do think that we are in for an increase of cases, not necessarily of deaths and serious illness, Dr. Dowdy says.”

The upshot?

“People need to realize that it’s not quite over,” Dr. Truelove says. “We still have a substantial amount of infection in our country. We’re still above 200 cases per million [and] 500,000 incident cases per week or so. That’s a lot of death and a lot of hospitalizations. So, we still have to be concerned and do our best to reduce transmission … by wearing masks, getting vaccinated, getting a booster shot, and getting your children vaccinated.”

Johns Hopkins social and behavioral scientist Rupali Limaye, PhD, MPH, adds that while COVID vaccines have been a “game changer” in the pandemic, more than a third of Americans have yet to receive one.

“That’s really what we need to be messaging around -- that people can still get COVID, there can still be breakthrough infections,” says Dr. Limaye, a health communications scholar. “But the great news is if you have been vaccinated, you are very much less likely, I think it’s 12 times, to be hospitalized or have severe COVID compared to those that are un-vaccinated.”

Dr. Topol agrees, adding: “Now is the time for the U.S. to heed the European signal for the first time, to pull out all the stops. Promote primary vaccination and boosters like there’s no tomorrow. Aggressively counter the pervasive misinformation and disinformation. Accelerate and expand the vaccine mandates ...

“Instead of succumbing to yet another major rise in cases and their sequelae, this is a chance for America to finally rise to the occasion, showing an ability to lead and execute.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Patient whips out smartphone and starts recording: Trouble ahead?

Joe Lindsey, a 48-year old Colorado-based journalist, has dealt with complex hearing loss for about 15 years. which has led to countless doctor’s visits, treatments, and even surgery in hopes of finding improvement. As time went on and Mr. Lindsey’s hearing deteriorated, he began recording his appointments in order to retain important information.

Mr. Lindsey had positive intentions, but not every patient does.

With smartphones everywhere, recording medical appointments can be fraught with downsides too. While there are clear-cut reasons for recording doctor visits, patients’ goals and how they carry out the taping are key. Audio only? Or also video? With the physician’s knowledge and permission, or without?

These are the legal and ethical weeds doctors find themselves in today, so it’s important to understand all sides of the issue.

The medical world is divided on its sentiments about patients recording their visits. The American Medical Association, in fact, failed to make progress on a recent policy (resolution 007) proposal to encourage that any “audio or video recording made during a medical encounter should require both physician and patient notification and consent.” Rather than voting on the resolution, the AMA house of delegates tabled it and chose to gather more information on the issue.

In most cases, patients are recording their visits in good faith, says Jeffrey Segal, MD, JD, the CEO and founder of Medical Justice, a risk mitigation and reputation management firm for healthcare clinicians. “When it comes to ‘Team, let’s record this,’ I’m a fan,” he says. “The most common reason patients record visits is that there’s a lot of information transferred from the doctor to the patient, and there’s just not enough time to absorb it all.”

While the option is there for patients to take notes, in the give-and-take nature of conversation, this can get difficult. “If they record the visit, they can then digest it all down the road,” says Dr. Segal. “A compliant patient is one who understands what’s expected. That’s the charitable explanation for recording, and I support it.”