User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

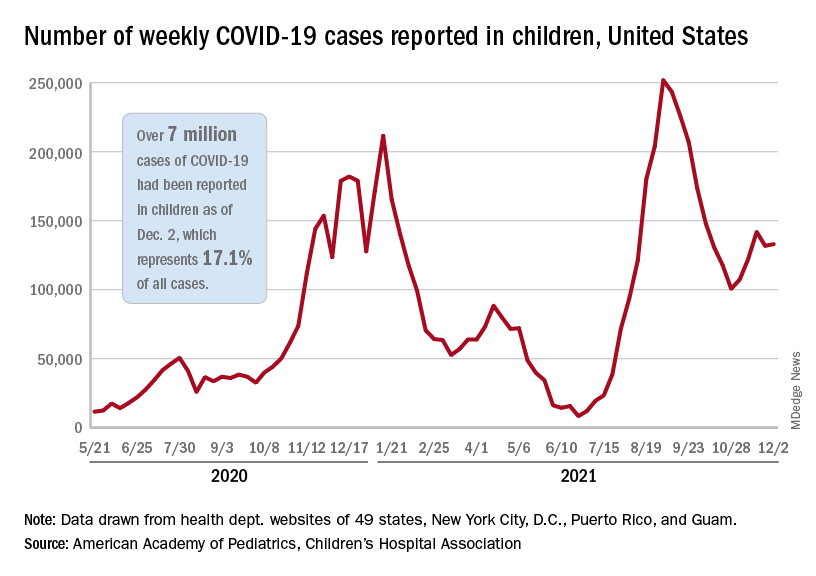

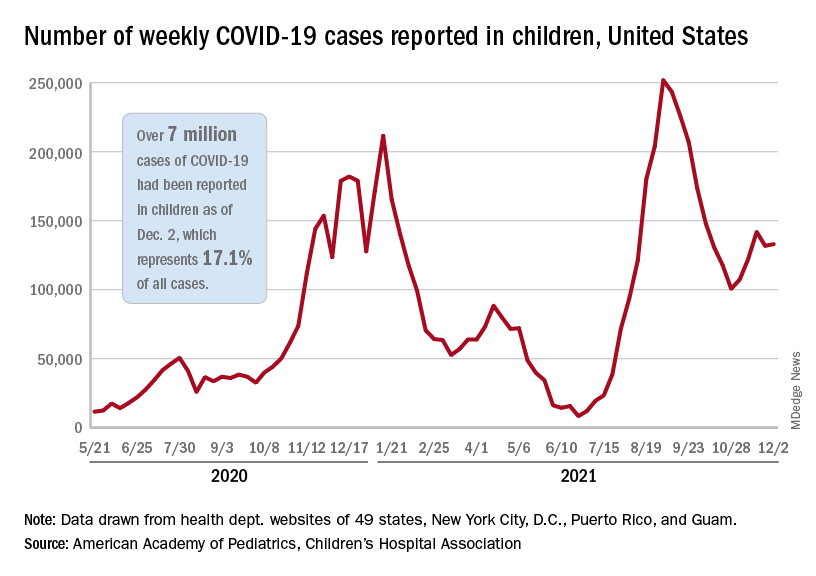

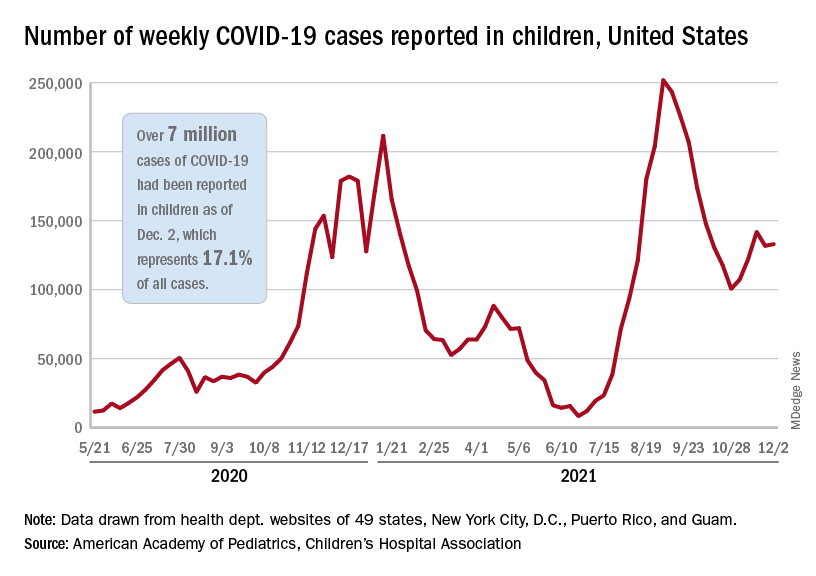

Children and COVID-19: 7 million cases and still counting

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Specialists think it’s up to the PCP to recommend flu vaccines. But many patients don’t see a PCP every year

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Online reviews most important factor in choosing a doctor: Survey

from Press Ganey, a provider of patient satisfaction surveys. According to the data, this online information is more important to consumers in selecting a physician than another doctor’s referral and is more than twice as important when choosing a primary care physician.

In fact, 83% of respondents said they went online to read reviews of a physician after receiving a referral from another provider.

The online research trend reflects not only the increased familiarity of all generations with the internet but also the growing consumerization of health care, Thomas Jeffrey, president of the Sullivan/Luallin Group, a patient experience consulting firm, told this news organization.

“According to patient satisfaction surveys, people are becoming health care consumers more than in the past,” he noted. “Historically, we didn’t look at health care as a consumer product. But, with high deductibles and copays, doctor visits can represent a pretty significant out-of-pocket expense. As it begins to hit folks’ pocketbooks, they become more savvy shoppers.”

Digital preferences for providers were gaining “positive momentum” even before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis “drove upticks in some consumer digital behaviors,” the Press Ganey report pointed out.

Mr. Jeffrey agreed, noting that this finding matches what Sullivan/Luallin has discovered in its research. “I think the pandemic pushed people to engage more online,” he said. “The highest net promoter score [likelihood to recommend in market surveys] for a pharmacy is the Amazon pharmacy, which is an online-based delivery service. Then you have telehealth visits, which are more convenient in many ways.”

How patients search online

In choosing a new primary care doctor, 51.1% go on the web first, 23.8% seek a referral from another health care provider, and 4.4% get information from an insurer or a benefits manager, according to the survey.

The factors that matter most to consumers when they pick any provider, in order, are online ratings and reviews of the physician, referral from a current doctor, ratings and reviews of the facility, and the quality and completeness of a doctor’s profile on a website or online directory. The doctor’s online presence and the quality of their website are also important.

According to Press Ganey, search engines like Google are the most used digital resources, with 65.4% of consumers employing them to find a doctor. However, consumers now use an average of 2.7 sites in their search. The leading destinations are a hospital or a clinic site, WebMD, Healthgrades, and Facebook. (This news organization is owned by WebMD.)

Compared with 2019, the report said, there has been a 22.8% decline in the use of search engines for seeking a doctor and a 53.7% increase in the use of health care review sites such as Healthgrades and Vitals.

When reading provider reviews, consumers look for more recent reviews and want the reviews to be “authentic and informative.” They also value the star ratings. About 84%of respondents said they wouldn’t book an appointment with a referred provider that had a rating of less than four stars.

Overall, the top reasons why people are deterred from making an appointment are difficulty contacting the office, the poor quality of online reviews, and an average online rating of less than four stars.

The vast majority of respondents (77%) said they believe internet reviews reflect their own experience with a provider organization, and only 2.6% said the reviews were inaccurate. Another finding of the survey indicates that this attention of patients to reviews of their own provider doesn’t represent idle curiosity: About 57% of Baby Boomers and 45% of millennials/Gen Z’ers said they’d written online reviews of a doctor or a hospital.

Factors in patient loyalty

The Press Ganey survey asked which of several factors, besides excellent care, patients weighed when giving a five-star review to a health care provider.

Quality of customer service was rated first by 70.8% of respondents, followed by cleanliness of facilities (67.5%), communication (63.4%), the provider’s bedside manner (63%), ease of appointment booking (58.8%), ease of patient intake/registration (52.3%), quality and accuracy of information (40.1%), availability of telehealth services (21.7%), and waiting room amenities (21.8%).

The report explained that “quality of customer service” means “demeanor, attentiveness, and helpfulness of staff and practitioners.” “Communication” refers to things like follow-up appointment reminders and annual checkup reminders.

According to Mr. Jeffrey, these factors were considered more important than a doctor’s bedside manner because of the team care approach in most physician offices. “We see a lot more folks derive their notion of quality from continuity of care. And if they feel the physician they love is being supported by a less than competent team, that can impact significantly their sense of the quality of care,” he said.

Online appointment booking is a must

To win over the online consumer, Press Ganey emphasized, practices should ensure that provider listings are accurate and complete. In addition, offering online appointment booking can avoid the top challenge in making a new appointment, which is getting through to the office.

Mr. Jeffrey concurred, although he notes that practices have to be careful about how they enable patients to select appointment slots online. He suggests that an appointment request form on a patient portal first ask what the purpose of the visit is and that it offer five or so options. If the request fits into a routine visit category, the provider’s calendar pops up and the patient can select a convenient time slot. If it’s something else, an appointment scheduler calls the patient back.

“There needs to be greater access to standard appointments online,” he said. “While privacy is an issue, you can use the patient portal that most EHRs have to provide online booking. If you want to succeed going forward, that’s going to be a major plus.”

Of course, to do any of this, including reading provider reviews, a consumer needs a good internet connection and a mobile or desktop device. While broadband internet access is still not available in some communities, the breakdown of the survey respondents by demographics shows that low-income people were included.

Mr. Jeffrey doesn’t believe that a lack of internet access or digital devices prevents many Americans from going online today. “Even in poor communities, most people have internet access through their smartphones. Even baby boomers are familiar with smartphones. I haven’t seen internet access be a big barrier for low-income households, because they all have access to phones.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from Press Ganey, a provider of patient satisfaction surveys. According to the data, this online information is more important to consumers in selecting a physician than another doctor’s referral and is more than twice as important when choosing a primary care physician.

In fact, 83% of respondents said they went online to read reviews of a physician after receiving a referral from another provider.

The online research trend reflects not only the increased familiarity of all generations with the internet but also the growing consumerization of health care, Thomas Jeffrey, president of the Sullivan/Luallin Group, a patient experience consulting firm, told this news organization.

“According to patient satisfaction surveys, people are becoming health care consumers more than in the past,” he noted. “Historically, we didn’t look at health care as a consumer product. But, with high deductibles and copays, doctor visits can represent a pretty significant out-of-pocket expense. As it begins to hit folks’ pocketbooks, they become more savvy shoppers.”

Digital preferences for providers were gaining “positive momentum” even before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis “drove upticks in some consumer digital behaviors,” the Press Ganey report pointed out.

Mr. Jeffrey agreed, noting that this finding matches what Sullivan/Luallin has discovered in its research. “I think the pandemic pushed people to engage more online,” he said. “The highest net promoter score [likelihood to recommend in market surveys] for a pharmacy is the Amazon pharmacy, which is an online-based delivery service. Then you have telehealth visits, which are more convenient in many ways.”

How patients search online

In choosing a new primary care doctor, 51.1% go on the web first, 23.8% seek a referral from another health care provider, and 4.4% get information from an insurer or a benefits manager, according to the survey.

The factors that matter most to consumers when they pick any provider, in order, are online ratings and reviews of the physician, referral from a current doctor, ratings and reviews of the facility, and the quality and completeness of a doctor’s profile on a website or online directory. The doctor’s online presence and the quality of their website are also important.

According to Press Ganey, search engines like Google are the most used digital resources, with 65.4% of consumers employing them to find a doctor. However, consumers now use an average of 2.7 sites in their search. The leading destinations are a hospital or a clinic site, WebMD, Healthgrades, and Facebook. (This news organization is owned by WebMD.)

Compared with 2019, the report said, there has been a 22.8% decline in the use of search engines for seeking a doctor and a 53.7% increase in the use of health care review sites such as Healthgrades and Vitals.

When reading provider reviews, consumers look for more recent reviews and want the reviews to be “authentic and informative.” They also value the star ratings. About 84%of respondents said they wouldn’t book an appointment with a referred provider that had a rating of less than four stars.

Overall, the top reasons why people are deterred from making an appointment are difficulty contacting the office, the poor quality of online reviews, and an average online rating of less than four stars.

The vast majority of respondents (77%) said they believe internet reviews reflect their own experience with a provider organization, and only 2.6% said the reviews were inaccurate. Another finding of the survey indicates that this attention of patients to reviews of their own provider doesn’t represent idle curiosity: About 57% of Baby Boomers and 45% of millennials/Gen Z’ers said they’d written online reviews of a doctor or a hospital.

Factors in patient loyalty

The Press Ganey survey asked which of several factors, besides excellent care, patients weighed when giving a five-star review to a health care provider.

Quality of customer service was rated first by 70.8% of respondents, followed by cleanliness of facilities (67.5%), communication (63.4%), the provider’s bedside manner (63%), ease of appointment booking (58.8%), ease of patient intake/registration (52.3%), quality and accuracy of information (40.1%), availability of telehealth services (21.7%), and waiting room amenities (21.8%).

The report explained that “quality of customer service” means “demeanor, attentiveness, and helpfulness of staff and practitioners.” “Communication” refers to things like follow-up appointment reminders and annual checkup reminders.

According to Mr. Jeffrey, these factors were considered more important than a doctor’s bedside manner because of the team care approach in most physician offices. “We see a lot more folks derive their notion of quality from continuity of care. And if they feel the physician they love is being supported by a less than competent team, that can impact significantly their sense of the quality of care,” he said.

Online appointment booking is a must

To win over the online consumer, Press Ganey emphasized, practices should ensure that provider listings are accurate and complete. In addition, offering online appointment booking can avoid the top challenge in making a new appointment, which is getting through to the office.

Mr. Jeffrey concurred, although he notes that practices have to be careful about how they enable patients to select appointment slots online. He suggests that an appointment request form on a patient portal first ask what the purpose of the visit is and that it offer five or so options. If the request fits into a routine visit category, the provider’s calendar pops up and the patient can select a convenient time slot. If it’s something else, an appointment scheduler calls the patient back.

“There needs to be greater access to standard appointments online,” he said. “While privacy is an issue, you can use the patient portal that most EHRs have to provide online booking. If you want to succeed going forward, that’s going to be a major plus.”

Of course, to do any of this, including reading provider reviews, a consumer needs a good internet connection and a mobile or desktop device. While broadband internet access is still not available in some communities, the breakdown of the survey respondents by demographics shows that low-income people were included.

Mr. Jeffrey doesn’t believe that a lack of internet access or digital devices prevents many Americans from going online today. “Even in poor communities, most people have internet access through their smartphones. Even baby boomers are familiar with smartphones. I haven’t seen internet access be a big barrier for low-income households, because they all have access to phones.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from Press Ganey, a provider of patient satisfaction surveys. According to the data, this online information is more important to consumers in selecting a physician than another doctor’s referral and is more than twice as important when choosing a primary care physician.

In fact, 83% of respondents said they went online to read reviews of a physician after receiving a referral from another provider.

The online research trend reflects not only the increased familiarity of all generations with the internet but also the growing consumerization of health care, Thomas Jeffrey, president of the Sullivan/Luallin Group, a patient experience consulting firm, told this news organization.

“According to patient satisfaction surveys, people are becoming health care consumers more than in the past,” he noted. “Historically, we didn’t look at health care as a consumer product. But, with high deductibles and copays, doctor visits can represent a pretty significant out-of-pocket expense. As it begins to hit folks’ pocketbooks, they become more savvy shoppers.”

Digital preferences for providers were gaining “positive momentum” even before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis “drove upticks in some consumer digital behaviors,” the Press Ganey report pointed out.

Mr. Jeffrey agreed, noting that this finding matches what Sullivan/Luallin has discovered in its research. “I think the pandemic pushed people to engage more online,” he said. “The highest net promoter score [likelihood to recommend in market surveys] for a pharmacy is the Amazon pharmacy, which is an online-based delivery service. Then you have telehealth visits, which are more convenient in many ways.”

How patients search online

In choosing a new primary care doctor, 51.1% go on the web first, 23.8% seek a referral from another health care provider, and 4.4% get information from an insurer or a benefits manager, according to the survey.

The factors that matter most to consumers when they pick any provider, in order, are online ratings and reviews of the physician, referral from a current doctor, ratings and reviews of the facility, and the quality and completeness of a doctor’s profile on a website or online directory. The doctor’s online presence and the quality of their website are also important.

According to Press Ganey, search engines like Google are the most used digital resources, with 65.4% of consumers employing them to find a doctor. However, consumers now use an average of 2.7 sites in their search. The leading destinations are a hospital or a clinic site, WebMD, Healthgrades, and Facebook. (This news organization is owned by WebMD.)

Compared with 2019, the report said, there has been a 22.8% decline in the use of search engines for seeking a doctor and a 53.7% increase in the use of health care review sites such as Healthgrades and Vitals.

When reading provider reviews, consumers look for more recent reviews and want the reviews to be “authentic and informative.” They also value the star ratings. About 84%of respondents said they wouldn’t book an appointment with a referred provider that had a rating of less than four stars.

Overall, the top reasons why people are deterred from making an appointment are difficulty contacting the office, the poor quality of online reviews, and an average online rating of less than four stars.

The vast majority of respondents (77%) said they believe internet reviews reflect their own experience with a provider organization, and only 2.6% said the reviews were inaccurate. Another finding of the survey indicates that this attention of patients to reviews of their own provider doesn’t represent idle curiosity: About 57% of Baby Boomers and 45% of millennials/Gen Z’ers said they’d written online reviews of a doctor or a hospital.

Factors in patient loyalty

The Press Ganey survey asked which of several factors, besides excellent care, patients weighed when giving a five-star review to a health care provider.

Quality of customer service was rated first by 70.8% of respondents, followed by cleanliness of facilities (67.5%), communication (63.4%), the provider’s bedside manner (63%), ease of appointment booking (58.8%), ease of patient intake/registration (52.3%), quality and accuracy of information (40.1%), availability of telehealth services (21.7%), and waiting room amenities (21.8%).

The report explained that “quality of customer service” means “demeanor, attentiveness, and helpfulness of staff and practitioners.” “Communication” refers to things like follow-up appointment reminders and annual checkup reminders.

According to Mr. Jeffrey, these factors were considered more important than a doctor’s bedside manner because of the team care approach in most physician offices. “We see a lot more folks derive their notion of quality from continuity of care. And if they feel the physician they love is being supported by a less than competent team, that can impact significantly their sense of the quality of care,” he said.

Online appointment booking is a must

To win over the online consumer, Press Ganey emphasized, practices should ensure that provider listings are accurate and complete. In addition, offering online appointment booking can avoid the top challenge in making a new appointment, which is getting through to the office.

Mr. Jeffrey concurred, although he notes that practices have to be careful about how they enable patients to select appointment slots online. He suggests that an appointment request form on a patient portal first ask what the purpose of the visit is and that it offer five or so options. If the request fits into a routine visit category, the provider’s calendar pops up and the patient can select a convenient time slot. If it’s something else, an appointment scheduler calls the patient back.

“There needs to be greater access to standard appointments online,” he said. “While privacy is an issue, you can use the patient portal that most EHRs have to provide online booking. If you want to succeed going forward, that’s going to be a major plus.”

Of course, to do any of this, including reading provider reviews, a consumer needs a good internet connection and a mobile or desktop device. While broadband internet access is still not available in some communities, the breakdown of the survey respondents by demographics shows that low-income people were included.

Mr. Jeffrey doesn’t believe that a lack of internet access or digital devices prevents many Americans from going online today. “Even in poor communities, most people have internet access through their smartphones. Even baby boomers are familiar with smartphones. I haven’t seen internet access be a big barrier for low-income households, because they all have access to phones.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Apixaban outmatches rivaroxaban for VTE in study

Recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) – a composite of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis – was the primary effectiveness outcome in the retrospective analysis of new-user data from almost 40,000 patients, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Safety was evaluated through a composite of intracranial and gastrointestinal bleeding.

After a median follow-up of 102 days in the apixaban group and 105 days in the rivaroxaban group, apixaban demonstrated superiority for both primary outcomes.

These real-world findings may guide selection of initial anticoagulant therapy, reported lead author Ghadeer K. Dawwas, PhD, MSc, MBA, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“Randomized clinical trials comparing apixaban with rivaroxaban in patients with VTE are under way (for example, COBRRA (NCT03266783),” the investigators wrote. “Until the results from these trials become available (The estimated completion date for COBRRA is December 2023.), observational studies that use existing data can provide evidence on the effectiveness and safety of these alternatives to inform clinical practice.”

In the new research, apixaban was associated with a 23% lower rate of recurrent VTE (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87), including a 15% lower rate of deep vein thrombosis and a 41% lower rate of pulmonary embolism. Apixaban was associated with 40% fewer bleeding events (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53-0.69]), including a 40% lower rate of GI bleeding and a 46% lower rate of intracranial bleeding.

The study involved 37,236 patients with VTE, all of whom were diagnosed in at least one inpatient encounter and initiated direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy within 30 days, according to Optum’s deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart Database. Patients were evenly split into apixaban and rivaroxaban groups, with 18,618 individuals in each. Propensity score matching was used to minimize differences in baseline characteristics.

Apixaban was associated with an absolute reduction in recurrent VTE of 0.6% and 1.1% over 2 and 6 months, respectively, as well as reductions in bleeding of 1.1% and 1.5% over the same respective time periods.

The investigators noted that these findings were maintained in various sensitivity and subgroup analyses, including a model in which patients with VTE who had transient risk factors were compared with VTE patients exhibiting chronic risk factors.

“These findings suggest that apixaban has superior effectiveness and safety, compared with rivaroxaban and may provide guidance to clinicians and patients regarding selection of an anticoagulant for treatment of VTE,” Dr. Dawwas and colleagues concluded.

Study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes, according to vascular surgeon

Thomas Wakefield, MD, a vascular surgeon and a professor of surgery at the University of Michigan Health Frankel Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor, generally agreed with the investigators’ conclusion, although he noted that DOAC selection may also be influenced by other considerations.

“The results of this study suggest that, when choosing an agent for an individual patient, apixaban does appear to have an advantage over rivaroxaban related to recurrent VTE and bleeding,” Dr. Wakefield said in an interview. “One must keep in mind that these are not the only factors that are considered when choosing an agent and these are not the only two DOACs available. For example, rivaroxaban is given once per day while apixaban is given twice per day, and rivaroxaban has been shown to be successful in the treatment of other thrombotic disorders.”

Dr. Wakefield also pointed out that the study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes.

“The current study looked at severe outcomes that resulted in inpatient hospitalization, so the generalization to strictly outpatient treatment and less severe outcomes cannot be inferred,” he said.

Damon E. Houghton, MD, of the department of medicine and a consultant in the department of vascular medicine and hematology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., called the study a “very nice analysis,” highlighting the large sample size.

“The results are not a reason to abandon rivaroxaban altogether, but do suggest that, when otherwise appropriate for a patient, apixaban should be the first choice,” Dr. Houghton said in a written comment. “Hopefully this analysis will encourage more payers to create financial incentives that facilitate the use of apixaban in more patients.”

Randomized trial needed, says hematologist

Colleen Edwards, MD, of the departments of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, had a more guarded view of the findings than Dr. Wakefield and Dr. Houghton.

“[The investigators] certainly seem to be doing a lot of statistical gymnastics in this paper,” Dr. Edwards said in an interview. “They used all kinds of surrogates in place of real data that you would get from a randomized trial.”

For example, Dr. Edwards noted the use of prescription refills as a surrogate for medication adherence, and emphasized that inpatient observational data may not reflect outpatient therapy.

“Inpatients are constantly missing their medicines all the time,” she said. “They’re holding it for procedures, they’re NPO, they’re off the floor, so they missed their medicine. So it’s just a very different patient population than the outpatient population, which is where venous thromboembolism is treated now, by and large.”

Although Dr. Edwards suggested that the findings might guide treatment selection “a little bit,” she noted that insurance constraints and costs play a greater role, and ultimately concluded that a randomized trial is needed to materially alter clinical decision-making.

“I think we really have to wait for randomized trial before we abandon our other choices,” she said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Merck, Celgene, UCB, and others. Dr. Wakefield reported awaiting disclosures. Dr. Houghton and Dr. Edwards reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) – a composite of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis – was the primary effectiveness outcome in the retrospective analysis of new-user data from almost 40,000 patients, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Safety was evaluated through a composite of intracranial and gastrointestinal bleeding.

After a median follow-up of 102 days in the apixaban group and 105 days in the rivaroxaban group, apixaban demonstrated superiority for both primary outcomes.

These real-world findings may guide selection of initial anticoagulant therapy, reported lead author Ghadeer K. Dawwas, PhD, MSc, MBA, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“Randomized clinical trials comparing apixaban with rivaroxaban in patients with VTE are under way (for example, COBRRA (NCT03266783),” the investigators wrote. “Until the results from these trials become available (The estimated completion date for COBRRA is December 2023.), observational studies that use existing data can provide evidence on the effectiveness and safety of these alternatives to inform clinical practice.”

In the new research, apixaban was associated with a 23% lower rate of recurrent VTE (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87), including a 15% lower rate of deep vein thrombosis and a 41% lower rate of pulmonary embolism. Apixaban was associated with 40% fewer bleeding events (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53-0.69]), including a 40% lower rate of GI bleeding and a 46% lower rate of intracranial bleeding.

The study involved 37,236 patients with VTE, all of whom were diagnosed in at least one inpatient encounter and initiated direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy within 30 days, according to Optum’s deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart Database. Patients were evenly split into apixaban and rivaroxaban groups, with 18,618 individuals in each. Propensity score matching was used to minimize differences in baseline characteristics.

Apixaban was associated with an absolute reduction in recurrent VTE of 0.6% and 1.1% over 2 and 6 months, respectively, as well as reductions in bleeding of 1.1% and 1.5% over the same respective time periods.

The investigators noted that these findings were maintained in various sensitivity and subgroup analyses, including a model in which patients with VTE who had transient risk factors were compared with VTE patients exhibiting chronic risk factors.

“These findings suggest that apixaban has superior effectiveness and safety, compared with rivaroxaban and may provide guidance to clinicians and patients regarding selection of an anticoagulant for treatment of VTE,” Dr. Dawwas and colleagues concluded.

Study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes, according to vascular surgeon

Thomas Wakefield, MD, a vascular surgeon and a professor of surgery at the University of Michigan Health Frankel Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor, generally agreed with the investigators’ conclusion, although he noted that DOAC selection may also be influenced by other considerations.

“The results of this study suggest that, when choosing an agent for an individual patient, apixaban does appear to have an advantage over rivaroxaban related to recurrent VTE and bleeding,” Dr. Wakefield said in an interview. “One must keep in mind that these are not the only factors that are considered when choosing an agent and these are not the only two DOACs available. For example, rivaroxaban is given once per day while apixaban is given twice per day, and rivaroxaban has been shown to be successful in the treatment of other thrombotic disorders.”

Dr. Wakefield also pointed out that the study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes.

“The current study looked at severe outcomes that resulted in inpatient hospitalization, so the generalization to strictly outpatient treatment and less severe outcomes cannot be inferred,” he said.

Damon E. Houghton, MD, of the department of medicine and a consultant in the department of vascular medicine and hematology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., called the study a “very nice analysis,” highlighting the large sample size.

“The results are not a reason to abandon rivaroxaban altogether, but do suggest that, when otherwise appropriate for a patient, apixaban should be the first choice,” Dr. Houghton said in a written comment. “Hopefully this analysis will encourage more payers to create financial incentives that facilitate the use of apixaban in more patients.”

Randomized trial needed, says hematologist

Colleen Edwards, MD, of the departments of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, had a more guarded view of the findings than Dr. Wakefield and Dr. Houghton.

“[The investigators] certainly seem to be doing a lot of statistical gymnastics in this paper,” Dr. Edwards said in an interview. “They used all kinds of surrogates in place of real data that you would get from a randomized trial.”

For example, Dr. Edwards noted the use of prescription refills as a surrogate for medication adherence, and emphasized that inpatient observational data may not reflect outpatient therapy.

“Inpatients are constantly missing their medicines all the time,” she said. “They’re holding it for procedures, they’re NPO, they’re off the floor, so they missed their medicine. So it’s just a very different patient population than the outpatient population, which is where venous thromboembolism is treated now, by and large.”

Although Dr. Edwards suggested that the findings might guide treatment selection “a little bit,” she noted that insurance constraints and costs play a greater role, and ultimately concluded that a randomized trial is needed to materially alter clinical decision-making.

“I think we really have to wait for randomized trial before we abandon our other choices,” she said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Merck, Celgene, UCB, and others. Dr. Wakefield reported awaiting disclosures. Dr. Houghton and Dr. Edwards reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) – a composite of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis – was the primary effectiveness outcome in the retrospective analysis of new-user data from almost 40,000 patients, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Safety was evaluated through a composite of intracranial and gastrointestinal bleeding.

After a median follow-up of 102 days in the apixaban group and 105 days in the rivaroxaban group, apixaban demonstrated superiority for both primary outcomes.

These real-world findings may guide selection of initial anticoagulant therapy, reported lead author Ghadeer K. Dawwas, PhD, MSc, MBA, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“Randomized clinical trials comparing apixaban with rivaroxaban in patients with VTE are under way (for example, COBRRA (NCT03266783),” the investigators wrote. “Until the results from these trials become available (The estimated completion date for COBRRA is December 2023.), observational studies that use existing data can provide evidence on the effectiveness and safety of these alternatives to inform clinical practice.”

In the new research, apixaban was associated with a 23% lower rate of recurrent VTE (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87), including a 15% lower rate of deep vein thrombosis and a 41% lower rate of pulmonary embolism. Apixaban was associated with 40% fewer bleeding events (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53-0.69]), including a 40% lower rate of GI bleeding and a 46% lower rate of intracranial bleeding.

The study involved 37,236 patients with VTE, all of whom were diagnosed in at least one inpatient encounter and initiated direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy within 30 days, according to Optum’s deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart Database. Patients were evenly split into apixaban and rivaroxaban groups, with 18,618 individuals in each. Propensity score matching was used to minimize differences in baseline characteristics.

Apixaban was associated with an absolute reduction in recurrent VTE of 0.6% and 1.1% over 2 and 6 months, respectively, as well as reductions in bleeding of 1.1% and 1.5% over the same respective time periods.

The investigators noted that these findings were maintained in various sensitivity and subgroup analyses, including a model in which patients with VTE who had transient risk factors were compared with VTE patients exhibiting chronic risk factors.

“These findings suggest that apixaban has superior effectiveness and safety, compared with rivaroxaban and may provide guidance to clinicians and patients regarding selection of an anticoagulant for treatment of VTE,” Dr. Dawwas and colleagues concluded.

Study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes, according to vascular surgeon

Thomas Wakefield, MD, a vascular surgeon and a professor of surgery at the University of Michigan Health Frankel Cardiovascular Center, Ann Arbor, generally agreed with the investigators’ conclusion, although he noted that DOAC selection may also be influenced by other considerations.

“The results of this study suggest that, when choosing an agent for an individual patient, apixaban does appear to have an advantage over rivaroxaban related to recurrent VTE and bleeding,” Dr. Wakefield said in an interview. “One must keep in mind that these are not the only factors that are considered when choosing an agent and these are not the only two DOACs available. For example, rivaroxaban is given once per day while apixaban is given twice per day, and rivaroxaban has been shown to be successful in the treatment of other thrombotic disorders.”

Dr. Wakefield also pointed out that the study may have missed some nuance in possible outcomes.

“The current study looked at severe outcomes that resulted in inpatient hospitalization, so the generalization to strictly outpatient treatment and less severe outcomes cannot be inferred,” he said.

Damon E. Houghton, MD, of the department of medicine and a consultant in the department of vascular medicine and hematology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., called the study a “very nice analysis,” highlighting the large sample size.

“The results are not a reason to abandon rivaroxaban altogether, but do suggest that, when otherwise appropriate for a patient, apixaban should be the first choice,” Dr. Houghton said in a written comment. “Hopefully this analysis will encourage more payers to create financial incentives that facilitate the use of apixaban in more patients.”

Randomized trial needed, says hematologist

Colleen Edwards, MD, of the departments of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, had a more guarded view of the findings than Dr. Wakefield and Dr. Houghton.

“[The investigators] certainly seem to be doing a lot of statistical gymnastics in this paper,” Dr. Edwards said in an interview. “They used all kinds of surrogates in place of real data that you would get from a randomized trial.”

For example, Dr. Edwards noted the use of prescription refills as a surrogate for medication adherence, and emphasized that inpatient observational data may not reflect outpatient therapy.

“Inpatients are constantly missing their medicines all the time,” she said. “They’re holding it for procedures, they’re NPO, they’re off the floor, so they missed their medicine. So it’s just a very different patient population than the outpatient population, which is where venous thromboembolism is treated now, by and large.”

Although Dr. Edwards suggested that the findings might guide treatment selection “a little bit,” she noted that insurance constraints and costs play a greater role, and ultimately concluded that a randomized trial is needed to materially alter clinical decision-making.

“I think we really have to wait for randomized trial before we abandon our other choices,” she said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Merck, Celgene, UCB, and others. Dr. Wakefield reported awaiting disclosures. Dr. Houghton and Dr. Edwards reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Care via video teleconferencing can be as effective as in-person for some conditions

This was a finding of a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine involving a review of literature on video teleconferencing (VTC) visits, which was authored by Jordan Albritton, PhD, MPH and his colleagues.

The authors found generally comparable patient outcomes as well as no differences in health care use, patient satisfaction, and quality of life when visits conducted using VTC were compared with usual care.

While VTC may work best for monitoring patients with chronic conditions, it can also be effective for acute care, said Dr. Albritton, who is a research public health analyst at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C., in an interview.

The investigators analyzed 20 randomized controlled trials of at least 50 patients and acceptable risk of bias in which VTC was used either for main or adjunct care delivery. Published from 2013 to 2019, these studies looked at care for diabetes and pain management, as well as some respiratory, neurologic, and cardiovascular conditions. Studies comparing VTC with usual care that did not involve any added in-person care were more likely to favor the VTC group, the investigators found.

“We excluded conditions such as substance use disorders, maternal care, and weight management for which there was sufficient prior evidence of the benefit of VTC,” Dr. Albritton said in an interview. “But I don’t think our results would have been substantially different if we had included these other diseases. We found general evidence in the literature that VTC is effective for a broader range of conditions.”

In some cases, such as if changes in a patient’s condition triggered an automatic virtual visit, the author said he thinks VTC may lead to even greater effectiveness.

“The doctor and patient could figure out on the spot what’s going on and perhaps change the medication,” Dr. Albritton explained.

In general agreement is Julia L. Frydman, MD, assistant professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who was not involved in the RTI research.

“Telemedicine has promise across many medical subspecialties, and what we need now are more studies to understand the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians as well as the impact of telemedicine on health outcomes and healthcare utilization.”

In acknowledgment of their utility, video visits are on the rise in the United States. A 2020 survey found that 22% of patients and 80% of physicians reported having participated in a video visit, three times the rate of the previous year. The authors noted that policy changes enacted to support telehealth strategies during the pandemic are expected to remain in place, and although patients are returning to in-person care, the virtual visit market will likely continue growing.

Increased telemedicine use by older adults

“We’ve seen an exciting expansion of telemedicine use among older adults, and we need to focus on continuing to meet their needs,” Dr. Frydman said.

In a recent study of televisits during the pandemic, Dr. Frydman’s group found a fivefold greater uptake of remote consultations by seniors – from 5% to 25%. Although in-person visits were far more common among older adults.

A specific advantage of video-based over audio-only telehealth, noted Dr. Albritton, is that physicians can directly observe patients in their home environment. Sharing that view is Deepa Iyengar, MBBS/MD,MPH, professor of family medicine at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, where, she said, “the pandemic has put VTC use into overdrive.”

According to Dr. Iyengar, who was not involved in the RTI research, the video component definitely represents value-added over phone calls. “You can pick up visual cues on video that you might not see if the patient came in and you can see what the home environment is like – whether there are a lot of loose rugs on the floor or broken or missing light bulbs,” she said in an interview.

‘VTC is here to stay’

In other parts of the country, doctors are finding virtual care useful – and more common. “VTC is here to stay, for sure – the horse is out of the barn,” said Cheryl L. Wilkes, MD, an internist at Northwestern Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “The RTI study shows no harm from VTC and also shows it may even improve clinical outcomes.”

Video visits can also save patients high parking fees at clinics and spare the sick or elderly from having to hire caregivers to bring them into the office or from having to walk blocks in dangerous weather conditions, she added. “And I can do a virtual visit on the fly or at night when a relative or caregiver is home from work to be there with the patient.”

In addition to being beneficial for following up with patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension or diabetes, VTC may be able to replace some visits that have traditionally required hands-on care, said Dr. Wilkes.

She said she knows a cardiologist who has refined a process whereby a patient – say, one who may have edema – is asked to perform a maneuver via VTC and then display the result to the doctor: The doctor says, “put your leg up and press on it hard for 10 seconds and then show me what it looks like,” according to Dr. Wilkes.

The key now is to identify the best persons across specialties from neurology to rheumatology to videotape ways they’ve created to help their patients participate virtually in consults traditionally done at the office, Dr. Wilkes noted.

But some conditions will always require palpation and the use of a stethoscope, according Dr. Iyengar.

“If someone has an ulcer, I have to be able to feel it,” she said.

And while some maternity care can be given virtually – for instance, if a mother-to be develops a bad cold – hands-on obstetrical care to check the position and health of the baby obviously has to be done in person. “So VTC is definitely going to be a welcome addition but not a replacement,” Dr. Iyengar said.

Gaps in research on VTC visits

Many questions remain regarding the overall usefulness of VTC visits for certain patient groups, according to the authors.

They highlighted, for example, the dearth of data on subgroups or on underserved and vulnerable populations, with no head-to-head studies identified in their review. In addition, they found no studies examining VTC versus usual care for patients with concurrent conditions or on its effect on health equity and disparities.

“It’s now our job to understand the ongoing barriers to telemedicine access, including the digital divide and the usability of telemedicine platforms, and design interventions that overcome them,” Dr. Frydman said. “At the same time, we need to make sure we’re understanding and respecting the preferences of older adults in terms of how they access health care.”

This study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Dr. Albritton is employed by RTI International, the contractor responsible for conducting the research and developing the manuscript. Several coauthors disclosed support from or contracts with PCORI. One coauthor’s spouse holds stock in private health companies. Dr. Frydman, Dr. Iyengar, and Dr. Wilkes disclosed no competing interests relevant to their comments.

This was a finding of a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine involving a review of literature on video teleconferencing (VTC) visits, which was authored by Jordan Albritton, PhD, MPH and his colleagues.

The authors found generally comparable patient outcomes as well as no differences in health care use, patient satisfaction, and quality of life when visits conducted using VTC were compared with usual care.

While VTC may work best for monitoring patients with chronic conditions, it can also be effective for acute care, said Dr. Albritton, who is a research public health analyst at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C., in an interview.

The investigators analyzed 20 randomized controlled trials of at least 50 patients and acceptable risk of bias in which VTC was used either for main or adjunct care delivery. Published from 2013 to 2019, these studies looked at care for diabetes and pain management, as well as some respiratory, neurologic, and cardiovascular conditions. Studies comparing VTC with usual care that did not involve any added in-person care were more likely to favor the VTC group, the investigators found.

“We excluded conditions such as substance use disorders, maternal care, and weight management for which there was sufficient prior evidence of the benefit of VTC,” Dr. Albritton said in an interview. “But I don’t think our results would have been substantially different if we had included these other diseases. We found general evidence in the literature that VTC is effective for a broader range of conditions.”

In some cases, such as if changes in a patient’s condition triggered an automatic virtual visit, the author said he thinks VTC may lead to even greater effectiveness.

“The doctor and patient could figure out on the spot what’s going on and perhaps change the medication,” Dr. Albritton explained.

In general agreement is Julia L. Frydman, MD, assistant professor in the Brookdale Department of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who was not involved in the RTI research.

“Telemedicine has promise across many medical subspecialties, and what we need now are more studies to understand the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians as well as the impact of telemedicine on health outcomes and healthcare utilization.”

In acknowledgment of their utility, video visits are on the rise in the United States. A 2020 survey found that 22% of patients and 80% of physicians reported having participated in a video visit, three times the rate of the previous year. The authors noted that policy changes enacted to support telehealth strategies during the pandemic are expected to remain in place, and although patients are returning to in-person care, the virtual visit market will likely continue growing.

Increased telemedicine use by older adults

“We’ve seen an exciting expansion of telemedicine use among older adults, and we need to focus on continuing to meet their needs,” Dr. Frydman said.

In a recent study of televisits during the pandemic, Dr. Frydman’s group found a fivefold greater uptake of remote consultations by seniors – from 5% to 25%. Although in-person visits were far more common among older adults.

A specific advantage of video-based over audio-only telehealth, noted Dr. Albritton, is that physicians can directly observe patients in their home environment. Sharing that view is Deepa Iyengar, MBBS/MD,MPH, professor of family medicine at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, where, she said, “the pandemic has put VTC use into overdrive.”

According to Dr. Iyengar, who was not involved in the RTI research, the video component definitely represents value-added over phone calls. “You can pick up visual cues on video that you might not see if the patient came in and you can see what the home environment is like – whether there are a lot of loose rugs on the floor or broken or missing light bulbs,” she said in an interview.

‘VTC is here to stay’

In other parts of the country, doctors are finding virtual care useful – and more common. “VTC is here to stay, for sure – the horse is out of the barn,” said Cheryl L. Wilkes, MD, an internist at Northwestern Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “The RTI study shows no harm from VTC and also shows it may even improve clinical outcomes.”

Video visits can also save patients high parking fees at clinics and spare the sick or elderly from having to hire caregivers to bring them into the office or from having to walk blocks in dangerous weather conditions, she added. “And I can do a virtual visit on the fly or at night when a relative or caregiver is home from work to be there with the patient.”

In addition to being beneficial for following up with patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension or diabetes, VTC may be able to replace some visits that have traditionally required hands-on care, said Dr. Wilkes.

She said she knows a cardiologist who has refined a process whereby a patient – say, one who may have edema – is asked to perform a maneuver via VTC and then display the result to the doctor: The doctor says, “put your leg up and press on it hard for 10 seconds and then show me what it looks like,” according to Dr. Wilkes.

The key now is to identify the best persons across specialties from neurology to rheumatology to videotape ways they’ve created to help their patients participate virtually in consults traditionally done at the office, Dr. Wilkes noted.

But some conditions will always require palpation and the use of a stethoscope, according Dr. Iyengar.

“If someone has an ulcer, I have to be able to feel it,” she said.

And while some maternity care can be given virtually – for instance, if a mother-to be develops a bad cold – hands-on obstetrical care to check the position and health of the baby obviously has to be done in person. “So VTC is definitely going to be a welcome addition but not a replacement,” Dr. Iyengar said.

Gaps in research on VTC visits

Many questions remain regarding the overall usefulness of VTC visits for certain patient groups, according to the authors.

They highlighted, for example, the dearth of data on subgroups or on underserved and vulnerable populations, with no head-to-head studies identified in their review. In addition, they found no studies examining VTC versus usual care for patients with concurrent conditions or on its effect on health equity and disparities.

“It’s now our job to understand the ongoing barriers to telemedicine access, including the digital divide and the usability of telemedicine platforms, and design interventions that overcome them,” Dr. Frydman said. “At the same time, we need to make sure we’re understanding and respecting the preferences of older adults in terms of how they access health care.”