User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

2023 GOLD update: Changes in COPD nomenclature and initial therapy

Airways Disorders Network

Asthma & COPD Section

The 2023 GOLD committee proposed changes in nomenclature and therapy for various subgroups of patients with COPD.

The mainstay of initial treatment for symptomatic COPD should include combination LABA/LAMA bronchodilators in a single inhaler. For patients with features of concomitant asthma or eosinophils greater than or equal to 300 cells/microliter, an ICS/LABA/LAMA combination inhaler is recommended.

People with “young COPD” develop respiratory symptoms and meet spirometric criteria for COPD between the ages of 25 and 50 years old. Other terminology changes center around those with functional and/or structural changes suggesting COPD, but who do not meet the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria to confirm the COPD diagnosis.

Those with “pre-COPD” have normal spirometry, including the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio, but have functional and/or structural changes concerning for COPD. Functional changes include air trapping and/or hyperinflation on PFTs, low diffusion capacity, and/or decline in FEV1 of > 40 mL per year.

Structural changes include emphysematous changes and/or bronchial wall changes on CT scans. “PRISm” stands for preserved ratio with impaired spirometry, where the postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC is greater than or equal to 0.70, but FEV1 is < 80% predicted with similar functional and/or structural changes to those with “pre-COPD.” People with PRISm have increased all-cause mortality. Not all people with pre-COPD or PRISm progress clinically and spirometrically to COPD; however, they should be treated because they have symptoms as well as functional and/or structural abnormalities. Despite increasing data regarding pre-COPD and PRISm, many gaps remain regarding optimal management.

Maria Ashar, MD, MBBS

Airways Disorders Network

Asthma & COPD Section

The 2023 GOLD committee proposed changes in nomenclature and therapy for various subgroups of patients with COPD.

The mainstay of initial treatment for symptomatic COPD should include combination LABA/LAMA bronchodilators in a single inhaler. For patients with features of concomitant asthma or eosinophils greater than or equal to 300 cells/microliter, an ICS/LABA/LAMA combination inhaler is recommended.

People with “young COPD” develop respiratory symptoms and meet spirometric criteria for COPD between the ages of 25 and 50 years old. Other terminology changes center around those with functional and/or structural changes suggesting COPD, but who do not meet the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria to confirm the COPD diagnosis.

Those with “pre-COPD” have normal spirometry, including the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio, but have functional and/or structural changes concerning for COPD. Functional changes include air trapping and/or hyperinflation on PFTs, low diffusion capacity, and/or decline in FEV1 of > 40 mL per year.

Structural changes include emphysematous changes and/or bronchial wall changes on CT scans. “PRISm” stands for preserved ratio with impaired spirometry, where the postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC is greater than or equal to 0.70, but FEV1 is < 80% predicted with similar functional and/or structural changes to those with “pre-COPD.” People with PRISm have increased all-cause mortality. Not all people with pre-COPD or PRISm progress clinically and spirometrically to COPD; however, they should be treated because they have symptoms as well as functional and/or structural abnormalities. Despite increasing data regarding pre-COPD and PRISm, many gaps remain regarding optimal management.

Maria Ashar, MD, MBBS

Airways Disorders Network

Asthma & COPD Section

The 2023 GOLD committee proposed changes in nomenclature and therapy for various subgroups of patients with COPD.

The mainstay of initial treatment for symptomatic COPD should include combination LABA/LAMA bronchodilators in a single inhaler. For patients with features of concomitant asthma or eosinophils greater than or equal to 300 cells/microliter, an ICS/LABA/LAMA combination inhaler is recommended.

People with “young COPD” develop respiratory symptoms and meet spirometric criteria for COPD between the ages of 25 and 50 years old. Other terminology changes center around those with functional and/or structural changes suggesting COPD, but who do not meet the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria to confirm the COPD diagnosis.

Those with “pre-COPD” have normal spirometry, including the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio, but have functional and/or structural changes concerning for COPD. Functional changes include air trapping and/or hyperinflation on PFTs, low diffusion capacity, and/or decline in FEV1 of > 40 mL per year.

Structural changes include emphysematous changes and/or bronchial wall changes on CT scans. “PRISm” stands for preserved ratio with impaired spirometry, where the postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC is greater than or equal to 0.70, but FEV1 is < 80% predicted with similar functional and/or structural changes to those with “pre-COPD.” People with PRISm have increased all-cause mortality. Not all people with pre-COPD or PRISm progress clinically and spirometrically to COPD; however, they should be treated because they have symptoms as well as functional and/or structural abnormalities. Despite increasing data regarding pre-COPD and PRISm, many gaps remain regarding optimal management.

Maria Ashar, MD, MBBS

In metastatic NSCLC, better QoL outcomes tied to better outcomes

The authors, including Fabio Salomone of the University of Naples Federico II, department of clinical medicine and surgery, also observed trends toward an association between QoL improvement and PFS among patients treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

The new research was presented during a poster session at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“The findings of the study support the thesis that QoL and survival in patients with NSCLC are linked. Although this is documented in the literature, this study sums up the evidence of a large number of RCTs, and provides detail in the QoL/survival relationship by treatment type. The subgroup analysis by treatment type is a key strength of the study showing that the QoL/survival link is stronger and more reliable in target(ed) therapies,” George Kypriotakis, PhD, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

Combining efficacy and quality of life improvement is an important consideration in clinical practice. “It is important that clinicians provide therapies that are also palliative and improve QoL,” said Dr. Kypriotakis, assistant professor of behavioral sciences at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. He noted that the finding of a PFS benefit is a good indicator of overall benefit, which is important since OS outcomes require a larger number of patients and longer follow-up to determine.

“PFS can still be a valid surrogate for OS, especially when it is positively associated with QoL,” noted Dr. Kypriotakis.

The study included 81 trials. Sixteen of the studies investigated immunotherapy, 50 investigated targeted therapy, and 17 investigated chemotherapy regimens. Thirty-seven percent of the trials found an improvement in QoL in the treatment arm compared with the control arm, 59.3% found no difference between arms, and 3.7% found a worse QoL in the treatment arm. There was no statistically significant association between an improvement in OS and QoL among the trials (P = .368).

Improved QoL tied to improved PFS

The researchers found an association between improved QoL and improved PFS. Among 60 trials that showed improved PFS, 43.3% found a superior QoL in the treatment arm, 53.3% showed no difference, and 3.3% showed reduced QoL. Among 20 trials that found no improvement in PFS, 20% demonstrated an improved QoL, 75% found no change, and 5% showed worse QoL (P = .0473).

A subanalysis of 48 targeted therapy trials found a correlation between PFS and QoL improvement (P = .0196). Among 25 trials involving patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors showing an improved PFS, 60% showed improved QoL, 36% showed no difference, and 4% showed worsening (P = .0077). Seven of these trials showed no PFS benefit and no change in QoL.

Industry sponsorship may affect QOL results

The researchers found potential evidence that industry sponsorship may lead to a spin on QoL outcomes. Among 51 trials that showed no QoL benefit associated with treatment, the description of the QoL outcome in 37 industry-sponsored was judged to be neutral and coherent with the study findings in 26 cases, but unjustifiably favorable in 11 cases. Among 14 with nonprofit support, descriptions of QoL results were found to be neutral in all cases (P = .0232).

“Obviously, industry may be motivated to overemphasize treatment benefits, especially in measures that also have a qualitative/subjective dimension such as QoL. Assuming that the authors used a reliable criterion to evaluate “inappropriateness,” industry may be more likely to emphasize QoL improvements as a surrogate for OS, especially when seeking drug approval,” Dr. Kypriotakis said.

The study is retrospective and cannot prove causation.

Dr. Salomone and Dr. Kypriotakis have no relevant financial disclosures.

The authors, including Fabio Salomone of the University of Naples Federico II, department of clinical medicine and surgery, also observed trends toward an association between QoL improvement and PFS among patients treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

The new research was presented during a poster session at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“The findings of the study support the thesis that QoL and survival in patients with NSCLC are linked. Although this is documented in the literature, this study sums up the evidence of a large number of RCTs, and provides detail in the QoL/survival relationship by treatment type. The subgroup analysis by treatment type is a key strength of the study showing that the QoL/survival link is stronger and more reliable in target(ed) therapies,” George Kypriotakis, PhD, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

Combining efficacy and quality of life improvement is an important consideration in clinical practice. “It is important that clinicians provide therapies that are also palliative and improve QoL,” said Dr. Kypriotakis, assistant professor of behavioral sciences at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. He noted that the finding of a PFS benefit is a good indicator of overall benefit, which is important since OS outcomes require a larger number of patients and longer follow-up to determine.

“PFS can still be a valid surrogate for OS, especially when it is positively associated with QoL,” noted Dr. Kypriotakis.

The study included 81 trials. Sixteen of the studies investigated immunotherapy, 50 investigated targeted therapy, and 17 investigated chemotherapy regimens. Thirty-seven percent of the trials found an improvement in QoL in the treatment arm compared with the control arm, 59.3% found no difference between arms, and 3.7% found a worse QoL in the treatment arm. There was no statistically significant association between an improvement in OS and QoL among the trials (P = .368).

Improved QoL tied to improved PFS

The researchers found an association between improved QoL and improved PFS. Among 60 trials that showed improved PFS, 43.3% found a superior QoL in the treatment arm, 53.3% showed no difference, and 3.3% showed reduced QoL. Among 20 trials that found no improvement in PFS, 20% demonstrated an improved QoL, 75% found no change, and 5% showed worse QoL (P = .0473).

A subanalysis of 48 targeted therapy trials found a correlation between PFS and QoL improvement (P = .0196). Among 25 trials involving patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors showing an improved PFS, 60% showed improved QoL, 36% showed no difference, and 4% showed worsening (P = .0077). Seven of these trials showed no PFS benefit and no change in QoL.

Industry sponsorship may affect QOL results

The researchers found potential evidence that industry sponsorship may lead to a spin on QoL outcomes. Among 51 trials that showed no QoL benefit associated with treatment, the description of the QoL outcome in 37 industry-sponsored was judged to be neutral and coherent with the study findings in 26 cases, but unjustifiably favorable in 11 cases. Among 14 with nonprofit support, descriptions of QoL results were found to be neutral in all cases (P = .0232).

“Obviously, industry may be motivated to overemphasize treatment benefits, especially in measures that also have a qualitative/subjective dimension such as QoL. Assuming that the authors used a reliable criterion to evaluate “inappropriateness,” industry may be more likely to emphasize QoL improvements as a surrogate for OS, especially when seeking drug approval,” Dr. Kypriotakis said.

The study is retrospective and cannot prove causation.

Dr. Salomone and Dr. Kypriotakis have no relevant financial disclosures.

The authors, including Fabio Salomone of the University of Naples Federico II, department of clinical medicine and surgery, also observed trends toward an association between QoL improvement and PFS among patients treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

The new research was presented during a poster session at European Lung Cancer Congress 2023.

“The findings of the study support the thesis that QoL and survival in patients with NSCLC are linked. Although this is documented in the literature, this study sums up the evidence of a large number of RCTs, and provides detail in the QoL/survival relationship by treatment type. The subgroup analysis by treatment type is a key strength of the study showing that the QoL/survival link is stronger and more reliable in target(ed) therapies,” George Kypriotakis, PhD, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview.

Combining efficacy and quality of life improvement is an important consideration in clinical practice. “It is important that clinicians provide therapies that are also palliative and improve QoL,” said Dr. Kypriotakis, assistant professor of behavioral sciences at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. He noted that the finding of a PFS benefit is a good indicator of overall benefit, which is important since OS outcomes require a larger number of patients and longer follow-up to determine.

“PFS can still be a valid surrogate for OS, especially when it is positively associated with QoL,” noted Dr. Kypriotakis.

The study included 81 trials. Sixteen of the studies investigated immunotherapy, 50 investigated targeted therapy, and 17 investigated chemotherapy regimens. Thirty-seven percent of the trials found an improvement in QoL in the treatment arm compared with the control arm, 59.3% found no difference between arms, and 3.7% found a worse QoL in the treatment arm. There was no statistically significant association between an improvement in OS and QoL among the trials (P = .368).

Improved QoL tied to improved PFS

The researchers found an association between improved QoL and improved PFS. Among 60 trials that showed improved PFS, 43.3% found a superior QoL in the treatment arm, 53.3% showed no difference, and 3.3% showed reduced QoL. Among 20 trials that found no improvement in PFS, 20% demonstrated an improved QoL, 75% found no change, and 5% showed worse QoL (P = .0473).

A subanalysis of 48 targeted therapy trials found a correlation between PFS and QoL improvement (P = .0196). Among 25 trials involving patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors showing an improved PFS, 60% showed improved QoL, 36% showed no difference, and 4% showed worsening (P = .0077). Seven of these trials showed no PFS benefit and no change in QoL.

Industry sponsorship may affect QOL results

The researchers found potential evidence that industry sponsorship may lead to a spin on QoL outcomes. Among 51 trials that showed no QoL benefit associated with treatment, the description of the QoL outcome in 37 industry-sponsored was judged to be neutral and coherent with the study findings in 26 cases, but unjustifiably favorable in 11 cases. Among 14 with nonprofit support, descriptions of QoL results were found to be neutral in all cases (P = .0232).

“Obviously, industry may be motivated to overemphasize treatment benefits, especially in measures that also have a qualitative/subjective dimension such as QoL. Assuming that the authors used a reliable criterion to evaluate “inappropriateness,” industry may be more likely to emphasize QoL improvements as a surrogate for OS, especially when seeking drug approval,” Dr. Kypriotakis said.

The study is retrospective and cannot prove causation.

Dr. Salomone and Dr. Kypriotakis have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ELCC 2023

Malpractice risks for docs who oversee NPs or PAs

Even in states that have abolished requirements that NPs be physician-supervised, physicians may still be liable by virtue of employing the NP, according to William P. Sullivan, DO, an attorney and emergency physician in Frankfort, Ill.

Indeed, the vast majority of lawsuits against NPs and PAs name the supervising physician. According to a study of claims against NPs from 2011 to 2016, 82% of the cases also named the supervising physician.

Employed or contracted physicians assigned to supervise NPs or PAs are also affected, Dr. Sullivan said. “The employed physicians’ contract with a hospital or staffing company may require them to assist in the selection, supervision, and/or training of NPs or PAs,” he said. He added that supervisory duties may also be assigned through hospital bylaws.

“The physician is usually not paid anything extra for this work and may not be given extra time to perform it,” Dr. Sullivan said. But still, he said, that physician could be named in a lawsuit and wind up bearing some responsibility for an NP’s or PA’s mistake.

In addition to facing medical malpractice suits, Dr. Sullivan said, doctors are often sanctioned by state licensure boards for improperly supervising NPs and PAs. Licensure boards often require extensive protocols for supervision of NPs and PAs.

Yet more states are removing supervision requirements

With the addition of Kansas and New York in 2022 and California in 2023, 27 states no longer require supervision for all or most NPs. Sixteen of those states, including New York and California, have instituted progressive practice authority that requires temporary supervision of new NPs but then removes supervision after a period of 6 months to 4 years, depending on the state, for the rest of their career.

“When it comes to NP independence, the horse is already out of the barn,” Dr. Sullivan said. “It’s unlikely that states will repeal laws granting NPs independence, and in fact, more states are likely to pass them.”

*PAs, in contrast, are well behind NPs in achieving independence, but the American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA) is calling to eliminate a mandated relationship with a specific physician. So far, Utah, North Dakota and Wyoming have ended physician supervision of PAs, while California and Hawaii have eliminated mandated chart review. Other states are considering eliminating physician supervision of PAs, according to the AAPA.

In states that have abolished oversight requirements for NPs, “liability can then shift to the NP when the NP is fully independent,” Cathy Klein, an advanced practice registered nurse who helped found the NP profession 50 years ago, told this news organization. “More NPs are starting their own practices, and in many cases, patients actually prefer to see an NP.”

As more NPs became more autonomous, the average payment that NPs incurred in professional liability lawsuits rose by 10.5% from 2017 to 2022, to $332,187, according to the Nurses Service Organization (NSO), a nursing malpractice insurer.

The number of malpractice judgments against autonomous NPs alone has also been rising. From 2012 to 2017, autonomous NPs’ share of all NP cases rose from 7% to 16.4%, the NSO reported.

The good news for physicians is that states’ removal of restrictions on NPs has reduced physicians’ liability to some extent. A 2017 study found that enacting less restrictive scope-of-practice laws for NPs decreased the number of payments made by physicians in NP cases by as much as 31%.

However, the top location for NP payouts remains the physician’s office, not the autonomous NP’s practice, according to the latter NSO report. Plaintiffs sue NPs’ and PAs’ supervising physicians on the basis of legal concepts, such as vicarious liability and respondeat superior. Even if the physician-employer never saw the patient, he or she can be held liable.

Court cases in which supervising physician was found liable

There are plenty of judgments against supervising or collaborating physicians when the NP or PA made the error. Typically, the doctor was faulted for paying little attention to the NP or PA he or she was supposed to supervise.

Dr. Sullivan points to a 2016 case in which a New York jury held a physician 40% liable for a $7 million judgment in a malpractice case involving a PA’s care of a patient in the emergency department. The case is Shajan v. South Nassau Community Hospital in New York.

“The patient presented with nontraumatic leg pain to his lower leg, was diagnosed by the PA with a muscle strain, and discharged without a physician evaluation,” Dr. Sullivan said. The next day, the patient visited an orthopedist who immediately diagnosed compartment syndrome, an emergent condition in which pressure builds up in an affected extremity, damaging the muscles and nerves. “The patient developed irreversible nerve damage and chronic regional pain syndrome,” he said.

A malpractice lawsuit named the PA and the emergency physician he was supposed to be reporting to. Even though the physician had never seen the patient, he had signed off on the PA’s note from a patient’s ED visit. “Testimony during the trial focused on hospital protocols that the supervising physician was supposed to take,” Dr. Sullivan said.

When doctors share fault, they frequently failed to follow the collaborative agreement with the NP or PA. In Collip v. Ratts, a 2015 Indiana case in which the patient died from a drug interaction, the doctor’s certified public accountant stated that the doctor was required to review at least 5% of the NP’s charts every week to evaluate her prescriptive practices.

The doctor admitted that he never reviewed the NP’s charts on a weekly basis. He did conduct some cursory reviews of some of the NP’s notes, and in them he noted concerns for her prescribing practices and suggested she attend a narcotics-prescribing seminar, but he did not follow up to make sure she had done this.

Sometimes the NP or PA who made the mistake may actually be dropped from the lawsuit, leaving the supervising physician fully liable. In these cases, courts reason that a fully engaged supervisor could have prevented the error. In the 2006 case of Husak v. Siegal, the Florida Supreme Court dropped the NP from the case, ruling that the NP had provided the supervising doctor all the information he needed in order to tell her what to do for the patient.

The court noted the physician had failed to look at the chart, even though he was required to do so under his supervisory agreement with the NP. The doctor “could have made the correct diagnosis or referral had he been attentive,” the court said. Therefore, there was “no evidence of independent negligence” by the NP, even though she was the one who had made the incorrect diagnosis that harmed the patient.

When states require an autonomous NP to have a supervisory relationship with a doctor, the supervisor may be unavailable and may fail to designate a substitute. In Texas in January 2019, a 7-year-old girl died of pneumonia after being treated by an NP in an urgent care clinic. The NP had told the parents that the child could safely go home and only needed ibuprofen. The parents brought the girl back home, and she died 15 hours later. The Wattenbargers sued the NP, and the doctor’s supervision was a topic in the trial.

The supervising physician for the NP was out of the country at the time. He said that he had found a substitute, but the substitute doctor testified she had no idea she was designated to be the substitute, according to Niran Al-Agba, MD, a family physician in Silverdale, Wash., who has written on the Texas case. Dr. Al-Agba told this news organization the case appears to have been settled confidentially.

Different standards for expert witnesses

In many states, courts do not allow physicians to testify as expert witnesses in malpractice cases against NPs, arguing that nurses have a different set of standards than doctors have, Dr. Sullivan reported.

These states include Arkansas, Illinois, North Carolina, and New York, according to a report by SEAK Inc., an expert witness training program. The report said most other states allow physician experts in these cases, but they may still require that they have experience with the nursing standard of care.

Dr. Sullivan said some courts are whittling away at the ban on physician experts, and the ban may eventually disappear. He reported that in Oklahoma, which normally upholds the ban, a judge recently allowed a physician-expert to testify in a case involving the death of a 19-year-old woman, Alexus Ochoa, in an ED staffed by an NP. The judge reasoned that Ms. Ochoa’s parents assumed the ED was staffed by physicians and would adhere to medical standards.

Supervision pointers from a physician

Physicians who supervise NPs or PAs say it is important to keep track of their skills and help them sharpen their expertise. Their scope of practice and physicians’ supervisory responsibilities are included in the collaborative agreement.

Arthur Apolinario, MD, a family physician in Clinton, N.C., says his 10-physician practice, which employs six NPs and one PA, works under a collaborative agreement. “The agreement defines each person’s scope of practice. They can’t do certain procedures, such as surgery, and they need extra training before doing certain tasks alone, such as joint injection.

“You have to always figure that if there is a lawsuit against one of them, you as the supervising physician would be named,” said Dr. Apolinario, who is also president of the North Carolina Medical Society. “We try to avert mistakes by meeting regularly with our NPs and PAs and making sure they keep up to date.”

Collaborating with autonomous NPs

Even when NPs operate independently in states that have abolished supervision, physicians may still have some liability if they give NPs advice, Dr. Al-Agba said.

At her Washington state practice, Dr. Al-Agba shares an office with an autonomous NP. “We share overhead and a front desk, but we have separate patients,” Dr. Al-Agba said. “This arrangement works very well for both of us.”

The NP sometimes asks her for advice. When this occurs, Dr. Al-Agba said she always makes sure to see the patient first. “If you don’t actually see the patient, there could be a misunderstanding that could lead to an error,” she said.

Conclusion

Even though NPs now have autonomy in most states, supervising physicians may still be liable for NP malpractice by virtue of being their employers, and physicians in the remaining states are liable for NPs through state law and for PAs in virtually all the states. To determine the supervising physician’s fault, courts often study whether the physician has met the terms of the collaborative agreement.

Physicians can reduce collaborating NPs’ and PAs’ liability by properly training them, by verifying their scope of practice, by making themselves easily available for consultation, and by occasionally seeing their patients. If their NPs and PAs do commit malpractice, supervising physicians may be able to protect themselves from liability by adhering to all requirements of the collaborative agreement.

*Correction, 4/19/2023: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the AAPA and the states that have ended physician supervision of PAs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even in states that have abolished requirements that NPs be physician-supervised, physicians may still be liable by virtue of employing the NP, according to William P. Sullivan, DO, an attorney and emergency physician in Frankfort, Ill.

Indeed, the vast majority of lawsuits against NPs and PAs name the supervising physician. According to a study of claims against NPs from 2011 to 2016, 82% of the cases also named the supervising physician.

Employed or contracted physicians assigned to supervise NPs or PAs are also affected, Dr. Sullivan said. “The employed physicians’ contract with a hospital or staffing company may require them to assist in the selection, supervision, and/or training of NPs or PAs,” he said. He added that supervisory duties may also be assigned through hospital bylaws.

“The physician is usually not paid anything extra for this work and may not be given extra time to perform it,” Dr. Sullivan said. But still, he said, that physician could be named in a lawsuit and wind up bearing some responsibility for an NP’s or PA’s mistake.

In addition to facing medical malpractice suits, Dr. Sullivan said, doctors are often sanctioned by state licensure boards for improperly supervising NPs and PAs. Licensure boards often require extensive protocols for supervision of NPs and PAs.

Yet more states are removing supervision requirements

With the addition of Kansas and New York in 2022 and California in 2023, 27 states no longer require supervision for all or most NPs. Sixteen of those states, including New York and California, have instituted progressive practice authority that requires temporary supervision of new NPs but then removes supervision after a period of 6 months to 4 years, depending on the state, for the rest of their career.

“When it comes to NP independence, the horse is already out of the barn,” Dr. Sullivan said. “It’s unlikely that states will repeal laws granting NPs independence, and in fact, more states are likely to pass them.”

*PAs, in contrast, are well behind NPs in achieving independence, but the American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA) is calling to eliminate a mandated relationship with a specific physician. So far, Utah, North Dakota and Wyoming have ended physician supervision of PAs, while California and Hawaii have eliminated mandated chart review. Other states are considering eliminating physician supervision of PAs, according to the AAPA.

In states that have abolished oversight requirements for NPs, “liability can then shift to the NP when the NP is fully independent,” Cathy Klein, an advanced practice registered nurse who helped found the NP profession 50 years ago, told this news organization. “More NPs are starting their own practices, and in many cases, patients actually prefer to see an NP.”

As more NPs became more autonomous, the average payment that NPs incurred in professional liability lawsuits rose by 10.5% from 2017 to 2022, to $332,187, according to the Nurses Service Organization (NSO), a nursing malpractice insurer.

The number of malpractice judgments against autonomous NPs alone has also been rising. From 2012 to 2017, autonomous NPs’ share of all NP cases rose from 7% to 16.4%, the NSO reported.

The good news for physicians is that states’ removal of restrictions on NPs has reduced physicians’ liability to some extent. A 2017 study found that enacting less restrictive scope-of-practice laws for NPs decreased the number of payments made by physicians in NP cases by as much as 31%.

However, the top location for NP payouts remains the physician’s office, not the autonomous NP’s practice, according to the latter NSO report. Plaintiffs sue NPs’ and PAs’ supervising physicians on the basis of legal concepts, such as vicarious liability and respondeat superior. Even if the physician-employer never saw the patient, he or she can be held liable.

Court cases in which supervising physician was found liable

There are plenty of judgments against supervising or collaborating physicians when the NP or PA made the error. Typically, the doctor was faulted for paying little attention to the NP or PA he or she was supposed to supervise.

Dr. Sullivan points to a 2016 case in which a New York jury held a physician 40% liable for a $7 million judgment in a malpractice case involving a PA’s care of a patient in the emergency department. The case is Shajan v. South Nassau Community Hospital in New York.

“The patient presented with nontraumatic leg pain to his lower leg, was diagnosed by the PA with a muscle strain, and discharged without a physician evaluation,” Dr. Sullivan said. The next day, the patient visited an orthopedist who immediately diagnosed compartment syndrome, an emergent condition in which pressure builds up in an affected extremity, damaging the muscles and nerves. “The patient developed irreversible nerve damage and chronic regional pain syndrome,” he said.

A malpractice lawsuit named the PA and the emergency physician he was supposed to be reporting to. Even though the physician had never seen the patient, he had signed off on the PA’s note from a patient’s ED visit. “Testimony during the trial focused on hospital protocols that the supervising physician was supposed to take,” Dr. Sullivan said.

When doctors share fault, they frequently failed to follow the collaborative agreement with the NP or PA. In Collip v. Ratts, a 2015 Indiana case in which the patient died from a drug interaction, the doctor’s certified public accountant stated that the doctor was required to review at least 5% of the NP’s charts every week to evaluate her prescriptive practices.

The doctor admitted that he never reviewed the NP’s charts on a weekly basis. He did conduct some cursory reviews of some of the NP’s notes, and in them he noted concerns for her prescribing practices and suggested she attend a narcotics-prescribing seminar, but he did not follow up to make sure she had done this.

Sometimes the NP or PA who made the mistake may actually be dropped from the lawsuit, leaving the supervising physician fully liable. In these cases, courts reason that a fully engaged supervisor could have prevented the error. In the 2006 case of Husak v. Siegal, the Florida Supreme Court dropped the NP from the case, ruling that the NP had provided the supervising doctor all the information he needed in order to tell her what to do for the patient.

The court noted the physician had failed to look at the chart, even though he was required to do so under his supervisory agreement with the NP. The doctor “could have made the correct diagnosis or referral had he been attentive,” the court said. Therefore, there was “no evidence of independent negligence” by the NP, even though she was the one who had made the incorrect diagnosis that harmed the patient.

When states require an autonomous NP to have a supervisory relationship with a doctor, the supervisor may be unavailable and may fail to designate a substitute. In Texas in January 2019, a 7-year-old girl died of pneumonia after being treated by an NP in an urgent care clinic. The NP had told the parents that the child could safely go home and only needed ibuprofen. The parents brought the girl back home, and she died 15 hours later. The Wattenbargers sued the NP, and the doctor’s supervision was a topic in the trial.

The supervising physician for the NP was out of the country at the time. He said that he had found a substitute, but the substitute doctor testified she had no idea she was designated to be the substitute, according to Niran Al-Agba, MD, a family physician in Silverdale, Wash., who has written on the Texas case. Dr. Al-Agba told this news organization the case appears to have been settled confidentially.

Different standards for expert witnesses

In many states, courts do not allow physicians to testify as expert witnesses in malpractice cases against NPs, arguing that nurses have a different set of standards than doctors have, Dr. Sullivan reported.

These states include Arkansas, Illinois, North Carolina, and New York, according to a report by SEAK Inc., an expert witness training program. The report said most other states allow physician experts in these cases, but they may still require that they have experience with the nursing standard of care.

Dr. Sullivan said some courts are whittling away at the ban on physician experts, and the ban may eventually disappear. He reported that in Oklahoma, which normally upholds the ban, a judge recently allowed a physician-expert to testify in a case involving the death of a 19-year-old woman, Alexus Ochoa, in an ED staffed by an NP. The judge reasoned that Ms. Ochoa’s parents assumed the ED was staffed by physicians and would adhere to medical standards.

Supervision pointers from a physician

Physicians who supervise NPs or PAs say it is important to keep track of their skills and help them sharpen their expertise. Their scope of practice and physicians’ supervisory responsibilities are included in the collaborative agreement.

Arthur Apolinario, MD, a family physician in Clinton, N.C., says his 10-physician practice, which employs six NPs and one PA, works under a collaborative agreement. “The agreement defines each person’s scope of practice. They can’t do certain procedures, such as surgery, and they need extra training before doing certain tasks alone, such as joint injection.

“You have to always figure that if there is a lawsuit against one of them, you as the supervising physician would be named,” said Dr. Apolinario, who is also president of the North Carolina Medical Society. “We try to avert mistakes by meeting regularly with our NPs and PAs and making sure they keep up to date.”

Collaborating with autonomous NPs

Even when NPs operate independently in states that have abolished supervision, physicians may still have some liability if they give NPs advice, Dr. Al-Agba said.

At her Washington state practice, Dr. Al-Agba shares an office with an autonomous NP. “We share overhead and a front desk, but we have separate patients,” Dr. Al-Agba said. “This arrangement works very well for both of us.”

The NP sometimes asks her for advice. When this occurs, Dr. Al-Agba said she always makes sure to see the patient first. “If you don’t actually see the patient, there could be a misunderstanding that could lead to an error,” she said.

Conclusion

Even though NPs now have autonomy in most states, supervising physicians may still be liable for NP malpractice by virtue of being their employers, and physicians in the remaining states are liable for NPs through state law and for PAs in virtually all the states. To determine the supervising physician’s fault, courts often study whether the physician has met the terms of the collaborative agreement.

Physicians can reduce collaborating NPs’ and PAs’ liability by properly training them, by verifying their scope of practice, by making themselves easily available for consultation, and by occasionally seeing their patients. If their NPs and PAs do commit malpractice, supervising physicians may be able to protect themselves from liability by adhering to all requirements of the collaborative agreement.

*Correction, 4/19/2023: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the AAPA and the states that have ended physician supervision of PAs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even in states that have abolished requirements that NPs be physician-supervised, physicians may still be liable by virtue of employing the NP, according to William P. Sullivan, DO, an attorney and emergency physician in Frankfort, Ill.

Indeed, the vast majority of lawsuits against NPs and PAs name the supervising physician. According to a study of claims against NPs from 2011 to 2016, 82% of the cases also named the supervising physician.

Employed or contracted physicians assigned to supervise NPs or PAs are also affected, Dr. Sullivan said. “The employed physicians’ contract with a hospital or staffing company may require them to assist in the selection, supervision, and/or training of NPs or PAs,” he said. He added that supervisory duties may also be assigned through hospital bylaws.

“The physician is usually not paid anything extra for this work and may not be given extra time to perform it,” Dr. Sullivan said. But still, he said, that physician could be named in a lawsuit and wind up bearing some responsibility for an NP’s or PA’s mistake.

In addition to facing medical malpractice suits, Dr. Sullivan said, doctors are often sanctioned by state licensure boards for improperly supervising NPs and PAs. Licensure boards often require extensive protocols for supervision of NPs and PAs.

Yet more states are removing supervision requirements

With the addition of Kansas and New York in 2022 and California in 2023, 27 states no longer require supervision for all or most NPs. Sixteen of those states, including New York and California, have instituted progressive practice authority that requires temporary supervision of new NPs but then removes supervision after a period of 6 months to 4 years, depending on the state, for the rest of their career.

“When it comes to NP independence, the horse is already out of the barn,” Dr. Sullivan said. “It’s unlikely that states will repeal laws granting NPs independence, and in fact, more states are likely to pass them.”

*PAs, in contrast, are well behind NPs in achieving independence, but the American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA) is calling to eliminate a mandated relationship with a specific physician. So far, Utah, North Dakota and Wyoming have ended physician supervision of PAs, while California and Hawaii have eliminated mandated chart review. Other states are considering eliminating physician supervision of PAs, according to the AAPA.

In states that have abolished oversight requirements for NPs, “liability can then shift to the NP when the NP is fully independent,” Cathy Klein, an advanced practice registered nurse who helped found the NP profession 50 years ago, told this news organization. “More NPs are starting their own practices, and in many cases, patients actually prefer to see an NP.”

As more NPs became more autonomous, the average payment that NPs incurred in professional liability lawsuits rose by 10.5% from 2017 to 2022, to $332,187, according to the Nurses Service Organization (NSO), a nursing malpractice insurer.

The number of malpractice judgments against autonomous NPs alone has also been rising. From 2012 to 2017, autonomous NPs’ share of all NP cases rose from 7% to 16.4%, the NSO reported.

The good news for physicians is that states’ removal of restrictions on NPs has reduced physicians’ liability to some extent. A 2017 study found that enacting less restrictive scope-of-practice laws for NPs decreased the number of payments made by physicians in NP cases by as much as 31%.

However, the top location for NP payouts remains the physician’s office, not the autonomous NP’s practice, according to the latter NSO report. Plaintiffs sue NPs’ and PAs’ supervising physicians on the basis of legal concepts, such as vicarious liability and respondeat superior. Even if the physician-employer never saw the patient, he or she can be held liable.

Court cases in which supervising physician was found liable

There are plenty of judgments against supervising or collaborating physicians when the NP or PA made the error. Typically, the doctor was faulted for paying little attention to the NP or PA he or she was supposed to supervise.

Dr. Sullivan points to a 2016 case in which a New York jury held a physician 40% liable for a $7 million judgment in a malpractice case involving a PA’s care of a patient in the emergency department. The case is Shajan v. South Nassau Community Hospital in New York.

“The patient presented with nontraumatic leg pain to his lower leg, was diagnosed by the PA with a muscle strain, and discharged without a physician evaluation,” Dr. Sullivan said. The next day, the patient visited an orthopedist who immediately diagnosed compartment syndrome, an emergent condition in which pressure builds up in an affected extremity, damaging the muscles and nerves. “The patient developed irreversible nerve damage and chronic regional pain syndrome,” he said.

A malpractice lawsuit named the PA and the emergency physician he was supposed to be reporting to. Even though the physician had never seen the patient, he had signed off on the PA’s note from a patient’s ED visit. “Testimony during the trial focused on hospital protocols that the supervising physician was supposed to take,” Dr. Sullivan said.

When doctors share fault, they frequently failed to follow the collaborative agreement with the NP or PA. In Collip v. Ratts, a 2015 Indiana case in which the patient died from a drug interaction, the doctor’s certified public accountant stated that the doctor was required to review at least 5% of the NP’s charts every week to evaluate her prescriptive practices.

The doctor admitted that he never reviewed the NP’s charts on a weekly basis. He did conduct some cursory reviews of some of the NP’s notes, and in them he noted concerns for her prescribing practices and suggested she attend a narcotics-prescribing seminar, but he did not follow up to make sure she had done this.

Sometimes the NP or PA who made the mistake may actually be dropped from the lawsuit, leaving the supervising physician fully liable. In these cases, courts reason that a fully engaged supervisor could have prevented the error. In the 2006 case of Husak v. Siegal, the Florida Supreme Court dropped the NP from the case, ruling that the NP had provided the supervising doctor all the information he needed in order to tell her what to do for the patient.

The court noted the physician had failed to look at the chart, even though he was required to do so under his supervisory agreement with the NP. The doctor “could have made the correct diagnosis or referral had he been attentive,” the court said. Therefore, there was “no evidence of independent negligence” by the NP, even though she was the one who had made the incorrect diagnosis that harmed the patient.

When states require an autonomous NP to have a supervisory relationship with a doctor, the supervisor may be unavailable and may fail to designate a substitute. In Texas in January 2019, a 7-year-old girl died of pneumonia after being treated by an NP in an urgent care clinic. The NP had told the parents that the child could safely go home and only needed ibuprofen. The parents brought the girl back home, and she died 15 hours later. The Wattenbargers sued the NP, and the doctor’s supervision was a topic in the trial.

The supervising physician for the NP was out of the country at the time. He said that he had found a substitute, but the substitute doctor testified she had no idea she was designated to be the substitute, according to Niran Al-Agba, MD, a family physician in Silverdale, Wash., who has written on the Texas case. Dr. Al-Agba told this news organization the case appears to have been settled confidentially.

Different standards for expert witnesses

In many states, courts do not allow physicians to testify as expert witnesses in malpractice cases against NPs, arguing that nurses have a different set of standards than doctors have, Dr. Sullivan reported.

These states include Arkansas, Illinois, North Carolina, and New York, according to a report by SEAK Inc., an expert witness training program. The report said most other states allow physician experts in these cases, but they may still require that they have experience with the nursing standard of care.

Dr. Sullivan said some courts are whittling away at the ban on physician experts, and the ban may eventually disappear. He reported that in Oklahoma, which normally upholds the ban, a judge recently allowed a physician-expert to testify in a case involving the death of a 19-year-old woman, Alexus Ochoa, in an ED staffed by an NP. The judge reasoned that Ms. Ochoa’s parents assumed the ED was staffed by physicians and would adhere to medical standards.

Supervision pointers from a physician

Physicians who supervise NPs or PAs say it is important to keep track of their skills and help them sharpen their expertise. Their scope of practice and physicians’ supervisory responsibilities are included in the collaborative agreement.

Arthur Apolinario, MD, a family physician in Clinton, N.C., says his 10-physician practice, which employs six NPs and one PA, works under a collaborative agreement. “The agreement defines each person’s scope of practice. They can’t do certain procedures, such as surgery, and they need extra training before doing certain tasks alone, such as joint injection.

“You have to always figure that if there is a lawsuit against one of them, you as the supervising physician would be named,” said Dr. Apolinario, who is also president of the North Carolina Medical Society. “We try to avert mistakes by meeting regularly with our NPs and PAs and making sure they keep up to date.”

Collaborating with autonomous NPs

Even when NPs operate independently in states that have abolished supervision, physicians may still have some liability if they give NPs advice, Dr. Al-Agba said.

At her Washington state practice, Dr. Al-Agba shares an office with an autonomous NP. “We share overhead and a front desk, but we have separate patients,” Dr. Al-Agba said. “This arrangement works very well for both of us.”

The NP sometimes asks her for advice. When this occurs, Dr. Al-Agba said she always makes sure to see the patient first. “If you don’t actually see the patient, there could be a misunderstanding that could lead to an error,” she said.

Conclusion

Even though NPs now have autonomy in most states, supervising physicians may still be liable for NP malpractice by virtue of being their employers, and physicians in the remaining states are liable for NPs through state law and for PAs in virtually all the states. To determine the supervising physician’s fault, courts often study whether the physician has met the terms of the collaborative agreement.

Physicians can reduce collaborating NPs’ and PAs’ liability by properly training them, by verifying their scope of practice, by making themselves easily available for consultation, and by occasionally seeing their patients. If their NPs and PAs do commit malpractice, supervising physicians may be able to protect themselves from liability by adhering to all requirements of the collaborative agreement.

*Correction, 4/19/2023: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the AAPA and the states that have ended physician supervision of PAs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

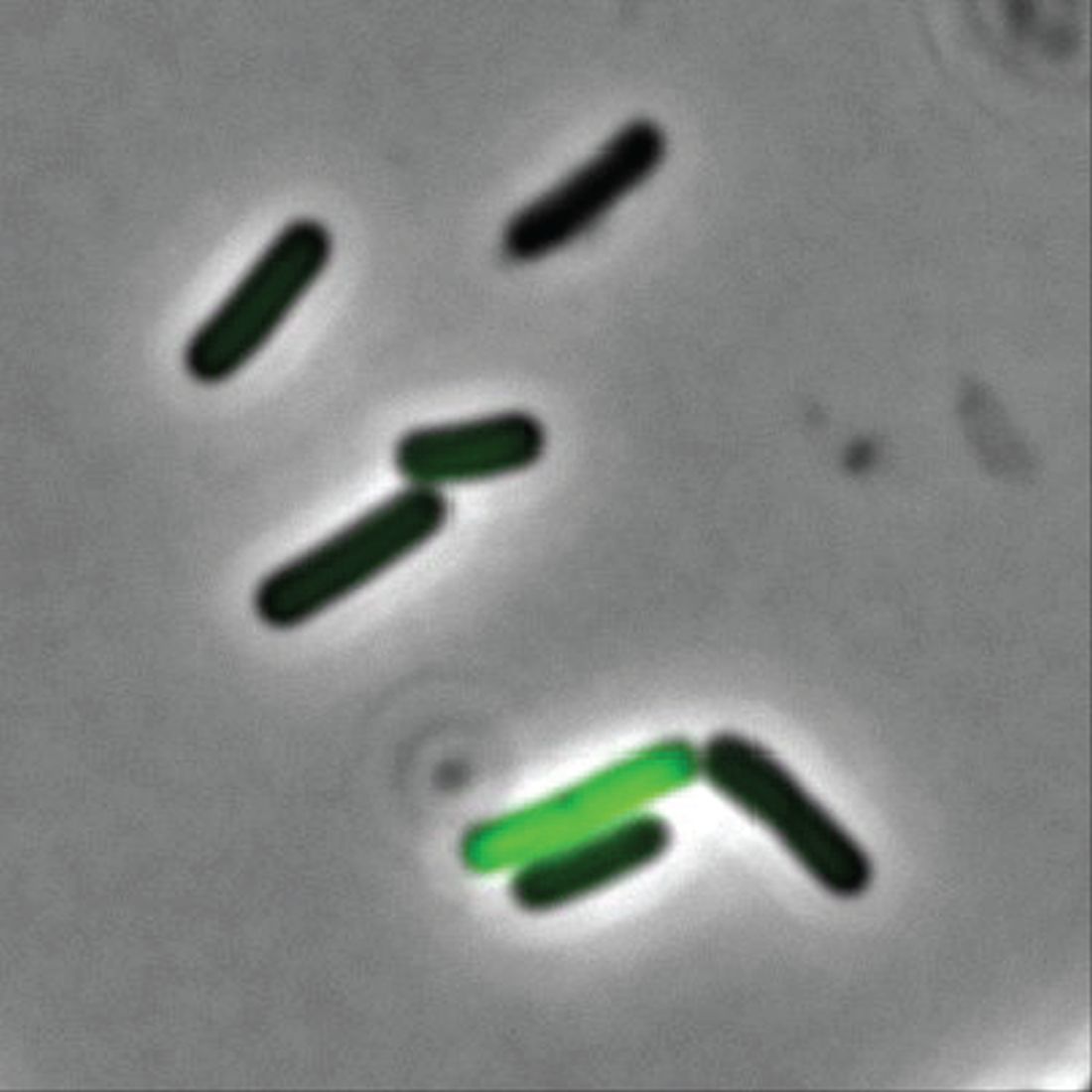

Lack of food for thought: Starve a bacterium, feed an infection

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

Genetic analysis shows causal link of GERD, other comorbidities to IPF

Relationships between 22 unique comorbidities and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) were assessed by a bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) approach in a retrospective study. Three of the comorbidities that were examined appeared causally associated with an increased risk of IPF.

Researchers used summary statistics of large-scale genomewide association studies (GWAS) obtained from the IPF Genetics Consortium. For replication, they used data from the Global Biobank Meta-Analysis Initiative.

Pulmonary or extrapulmonary illnesses are regularly observed to be comorbidities associated with IPF. Although randomized control trials can provide strong deductive evidence of causal relationships between diseases, they are also often subject to inherent practical and ethical limitations. MR is an alternative approach that exploits genetic variants of genes with known function as a means to infer a causal effect of a modifiable exposure on disease and minimizes possible confounding issues from unrelated environmental factors and reverse causation. Bidirectional MR extends the exposure-outcome association analysis of MR to both directions, producing a higher level of evidence for causality, Jiahao Zhu, of the Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Hangzhou, China, and colleagues wrote.

Study details

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reported on direction and causal associations between IPF and comorbidities, as determined by bidirectional MR analysis of GWAS summary statistics from five studies included in the IPF Genetics Consortium (4,125 patients and 20,464 control participants). For replication, they extracted IPF GWAS summary statistics from the nine biobanks from the GBMI (6,257 patients and 947,616 control participants). All individuals were of European ancestry.

The 22 comorbidities examined for a relationship to IPF were identified through a combination of a PubMed database literature search limited to English-language articles concerning IPF as either an exposure or an outcome and having an available full GWAS summary statistic. The number of patients in these studies ranged from a minimum of 3,203 for osteoporosis to a maximum of 246,363 for major depressive disorder.

To estimate causal relationships, single-nucleotide polymorphism selection for IPF and each comorbidity genetic instrument were based on a genomewide significance value (P < 5x10–8) and were clumped by linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kB clumping distance). Evidence from analysis associating each comorbidity with IPF was categorized as either convincing, suggestive, or weak. Follow-up studies examined the causal effects of measured lung and thyroid variables on IPF and IPF effects on blood pressure variables.

Convincing evidence

The bidirectional MR and follow-up analysis revealed “convincing evidence” of causal relationships between IPF and 2 of the evaluated 22 comorbidities. A higher risk of IPF was associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Importantly, a multivariable MR analysis conditioning for smoking continued to show the causal linkage between GERD and a higher risk of IPF. In contrast, the genetic liability of COPD appeared to confer a protective role, as indicated by an associated decrease in risk for IPF. The researchers suggest that this negative relationship may be caused by their distinct genetic architecture.

Suggestive evidence

“Suggestive evidence” of underlying relationships between IPF and lung cancer or blood pressure phenotype comorbidities was also found with this study. The MR results give support to existing evidence that IPF has a causal effect for a higher lung cancer risk. In contrast, IPF appeared to have a protective effect on hypertension and BP phenotypes. This contrasted with VTE: Evidence suggestive that genetic liability to hypothyroidism could lead to IPF was also found (International IPF Genetics Consortium, P < .040; MR PRESSO method; and GBMI, P < .002; IVW method).

Limitations

The primary strengths of the study was the ability of MR design to enhance causal inference, particularly when large cohorts for perspective investigations would be inherently difficult to obtain. Several noted limitations include the fact that causal estimates may not be well matched to observational or interventional studies and there was a low number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms available as genetic instruments for some diseases. In addition, there was a potential bias because of some sample overlap among the utilized databases, and it is unknown whether the results are applicable to ethnicities other than those of European ancestry.

Conclusion

Overall, this study showed that a bidirectional MR analysis approach could leverage genetic information from large databases to reveal causative associations between IPF and several different comorbidities. This included an apparent causal relationship of GERD, venous thromboembolism, and hypothyroidism with IPF, according to the researchers. These provide the basis to obtain “a deeper understanding of the pathways underlying these diverse associations” that may have valuable “implications for enhanced prevention and treatment strategies for comorbidities.”

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Relationships between 22 unique comorbidities and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) were assessed by a bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) approach in a retrospective study. Three of the comorbidities that were examined appeared causally associated with an increased risk of IPF.

Researchers used summary statistics of large-scale genomewide association studies (GWAS) obtained from the IPF Genetics Consortium. For replication, they used data from the Global Biobank Meta-Analysis Initiative.

Pulmonary or extrapulmonary illnesses are regularly observed to be comorbidities associated with IPF. Although randomized control trials can provide strong deductive evidence of causal relationships between diseases, they are also often subject to inherent practical and ethical limitations. MR is an alternative approach that exploits genetic variants of genes with known function as a means to infer a causal effect of a modifiable exposure on disease and minimizes possible confounding issues from unrelated environmental factors and reverse causation. Bidirectional MR extends the exposure-outcome association analysis of MR to both directions, producing a higher level of evidence for causality, Jiahao Zhu, of the Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Hangzhou, China, and colleagues wrote.

Study details

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reported on direction and causal associations between IPF and comorbidities, as determined by bidirectional MR analysis of GWAS summary statistics from five studies included in the IPF Genetics Consortium (4,125 patients and 20,464 control participants). For replication, they extracted IPF GWAS summary statistics from the nine biobanks from the GBMI (6,257 patients and 947,616 control participants). All individuals were of European ancestry.

The 22 comorbidities examined for a relationship to IPF were identified through a combination of a PubMed database literature search limited to English-language articles concerning IPF as either an exposure or an outcome and having an available full GWAS summary statistic. The number of patients in these studies ranged from a minimum of 3,203 for osteoporosis to a maximum of 246,363 for major depressive disorder.

To estimate causal relationships, single-nucleotide polymorphism selection for IPF and each comorbidity genetic instrument were based on a genomewide significance value (P < 5x10–8) and were clumped by linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kB clumping distance). Evidence from analysis associating each comorbidity with IPF was categorized as either convincing, suggestive, or weak. Follow-up studies examined the causal effects of measured lung and thyroid variables on IPF and IPF effects on blood pressure variables.

Convincing evidence

The bidirectional MR and follow-up analysis revealed “convincing evidence” of causal relationships between IPF and 2 of the evaluated 22 comorbidities. A higher risk of IPF was associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Importantly, a multivariable MR analysis conditioning for smoking continued to show the causal linkage between GERD and a higher risk of IPF. In contrast, the genetic liability of COPD appeared to confer a protective role, as indicated by an associated decrease in risk for IPF. The researchers suggest that this negative relationship may be caused by their distinct genetic architecture.

Suggestive evidence

“Suggestive evidence” of underlying relationships between IPF and lung cancer or blood pressure phenotype comorbidities was also found with this study. The MR results give support to existing evidence that IPF has a causal effect for a higher lung cancer risk. In contrast, IPF appeared to have a protective effect on hypertension and BP phenotypes. This contrasted with VTE: Evidence suggestive that genetic liability to hypothyroidism could lead to IPF was also found (International IPF Genetics Consortium, P < .040; MR PRESSO method; and GBMI, P < .002; IVW method).

Limitations

The primary strengths of the study was the ability of MR design to enhance causal inference, particularly when large cohorts for perspective investigations would be inherently difficult to obtain. Several noted limitations include the fact that causal estimates may not be well matched to observational or interventional studies and there was a low number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms available as genetic instruments for some diseases. In addition, there was a potential bias because of some sample overlap among the utilized databases, and it is unknown whether the results are applicable to ethnicities other than those of European ancestry.

Conclusion

Overall, this study showed that a bidirectional MR analysis approach could leverage genetic information from large databases to reveal causative associations between IPF and several different comorbidities. This included an apparent causal relationship of GERD, venous thromboembolism, and hypothyroidism with IPF, according to the researchers. These provide the basis to obtain “a deeper understanding of the pathways underlying these diverse associations” that may have valuable “implications for enhanced prevention and treatment strategies for comorbidities.”

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.