User login

Achieving a ‘new sexual-health paradigm’ means expanding STI care

A vital aspect of expanding access and care for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States is broadening responsibility for this care across the health care system and other community resources, according to an article published online July 6 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. This expansion and decentralization of care are central to adopting the “new sexual health paradigm” recommended by a National Academies report that was published in March.

“STIs represent a sizable, longstanding, and growing public health challenge,” write Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, PhD, MPH, dean and professor at the Duke University School of Nursing and director of the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health (CLAFH) at Duke University, both in Durham, N.C., and his colleagues. Yet the limitations on the current STI workforce and limited federal funding and support for STI prevention and care mean it will take clinicians of all types from across the health care spectrum to meet the challenge, they explain.

“For too long, STI prevention and treatment has been perceived as the sole responsibility of a narrow workforce of specialized STI and HIV service providers,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthor, Marco Thimm-Kaiser, MPH, associate in research at Duke University and epidemiologist at CLAFH, wrote in an email.

“However, the resources allocated to this STI specialty workforce have diminished over time, along with decreasing investments in the broader U.S. public health infrastructure,” they continued. “At the same time – and in part due to this underinvestment – STI rates have soared, reaching a record high for the sixth year in a row in 2019.”

Those factors led to the National Academies report, which recommends moving “away from the traditional, disease-focused perspective on STIs in favor of a holistic perspective of sexual health as an integral component of overall health and well-being,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote to this news organization.

In their article, the authors review the limitations in the STI workforce, the implications of those limitations for the broader health care industry, and what it will take for STI and HIV specialists as well as regulators to ensure it’s possible to achieve the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies.

Currently, the biggest limitation is access to care, said Laura Mercer, MD, MBA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the ob.gyn. clerkship director at the University of Arizona, Phoenix. Dr. Mercer, who was not involved with the National Academies report or the analysis of it, said in an interview that it’s essential to emphasize “sexual health as a core element of routine primary and preventative care” to ensure it becomes more accessible to patients without the need to seek out specialty care.

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his colleagues drive home the importance of such a shift by noting that more than 200 million Americans live in counties with no practicing infectious disease physicians. The disparities are greatest in Southern states, which account for 40% of all reported STIs. The workforce shortage has continued to worsen alongside the deterioration of the clinical infrastructure supporting STI specialty services, the authors write.

Hence the need to expand accountability for care not only to primary-care physicians but also to nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and behavioral health practitioners. Doing so also requires normalizing sexual health services across health care professions.

“Prevention is a crucial first step” to this, Dr. Mercer said. “This is particularly important as we recall that almost half of new sexually transmitted infections occur in teenagers. Destigmatizing sexual health and sexual health education will also help encourage patients of all ages to request and accept testing.”

Further, with primary care practitioners managing most STI testing and treatment, subspecialists can focus primarily on complex or refractory cases, she added. Ways to help broaden care include developing point-of-care testing for STIs and improving the accuracy of existing testing, she said.

“The goal is to make routine sexual health services accessible in a wide range of settings, such as in primary care, at pharmacies, and in community-based settings, and to draw on a broader workforce for delivery of sexual health services,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview.

Kevin Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of clinical and translational research at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that many medical organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have long advocated incorporating sexual health into routine preventive care. He also noted that pharmacists have already become proactive in preventing STIs and could continue to do so.

“Vaccines for hepatitis and human papillomavirus are commonly available at pharmacies,” Dr. Ault said. He was not involved in the article by Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and colleagues or the original report. “Pharmacists could also fill a gap by administering injectable medications such as penicillin. States would have to approve changes in policy, but many states have already done this for expedited partner therapy.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser noted similar barriers that must be removed to broaden delivery of STI services.

“Unfortunately, too many highly trained health care providers who are well-positioned for the delivery of sexual health services face regulatory or administrative barriers to practice to the full scope of their training,” they wrote. “These barriers can have a particularly negative impact in medically underserved communities, where physician shortages are common and where novel, decentralized health care service delivery models that draw on nonphysician providers may hold the greatest promise.”

As more diverse health care practitioners take on these roles, ID and HIV specialists can provide their expertise in developing training and technical assistance to support generalists, Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They can also aid in aligning “clinical training curricula, licensing criteria, and practice guidelines with routine delivery of sexual health services.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthors offer specific recommendations for professional training, licensing, and practice guidelines to help overcome the “insufficient knowledge, inadequate training, and absence of explicit protocols” that currently impede delivery of STI services in general practice settings.

Although the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies is ambitious, it’s also necessary, and “none of the recommendations are out of reach,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview. They pointed out how the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how underresourced the health care workforce and infrastructure are and how great health care disparities are.

“There is momentum toward rebuilding the nation’s health and public health system in a more effective and efficient way,” they said, and many of the STI report’s recommendations “overlap with priorities for the broader health and public health system moving forward.”

Dr. Mercer also believes the recommendations are realistic, “but only the beginning,” she told this news organization. “Comprehensive sexual education to expand knowledge about STI prevention and public health campaigns to help destigmatize sexual health care in general will remain crucial,” she said.

Sexual education, expanded access, and destigmatizing sexual care are particularly important for reaching the populations most in need of care, such as adolescents and young adults, as well as ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender-minority youth.

“It cannot be overstated how important of a priority population adolescents and young adults are,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They noted that those aged 15-24 account for half of all STIs each year but represent only a quarter of the sexually active population. “Targeted efforts for STI prevention and treatment among adolescents and young adults are therefore essential for an overall successful strategy to address STIs and sexual health in the United States.”

The National Academies report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Dr. Mercer, Dr. Ault, and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Guilamo-Ramos has received grants and personal fees from ViiV Health care.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A vital aspect of expanding access and care for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States is broadening responsibility for this care across the health care system and other community resources, according to an article published online July 6 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. This expansion and decentralization of care are central to adopting the “new sexual health paradigm” recommended by a National Academies report that was published in March.

“STIs represent a sizable, longstanding, and growing public health challenge,” write Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, PhD, MPH, dean and professor at the Duke University School of Nursing and director of the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health (CLAFH) at Duke University, both in Durham, N.C., and his colleagues. Yet the limitations on the current STI workforce and limited federal funding and support for STI prevention and care mean it will take clinicians of all types from across the health care spectrum to meet the challenge, they explain.

“For too long, STI prevention and treatment has been perceived as the sole responsibility of a narrow workforce of specialized STI and HIV service providers,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthor, Marco Thimm-Kaiser, MPH, associate in research at Duke University and epidemiologist at CLAFH, wrote in an email.

“However, the resources allocated to this STI specialty workforce have diminished over time, along with decreasing investments in the broader U.S. public health infrastructure,” they continued. “At the same time – and in part due to this underinvestment – STI rates have soared, reaching a record high for the sixth year in a row in 2019.”

Those factors led to the National Academies report, which recommends moving “away from the traditional, disease-focused perspective on STIs in favor of a holistic perspective of sexual health as an integral component of overall health and well-being,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote to this news organization.

In their article, the authors review the limitations in the STI workforce, the implications of those limitations for the broader health care industry, and what it will take for STI and HIV specialists as well as regulators to ensure it’s possible to achieve the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies.

Currently, the biggest limitation is access to care, said Laura Mercer, MD, MBA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the ob.gyn. clerkship director at the University of Arizona, Phoenix. Dr. Mercer, who was not involved with the National Academies report or the analysis of it, said in an interview that it’s essential to emphasize “sexual health as a core element of routine primary and preventative care” to ensure it becomes more accessible to patients without the need to seek out specialty care.

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his colleagues drive home the importance of such a shift by noting that more than 200 million Americans live in counties with no practicing infectious disease physicians. The disparities are greatest in Southern states, which account for 40% of all reported STIs. The workforce shortage has continued to worsen alongside the deterioration of the clinical infrastructure supporting STI specialty services, the authors write.

Hence the need to expand accountability for care not only to primary-care physicians but also to nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and behavioral health practitioners. Doing so also requires normalizing sexual health services across health care professions.

“Prevention is a crucial first step” to this, Dr. Mercer said. “This is particularly important as we recall that almost half of new sexually transmitted infections occur in teenagers. Destigmatizing sexual health and sexual health education will also help encourage patients of all ages to request and accept testing.”

Further, with primary care practitioners managing most STI testing and treatment, subspecialists can focus primarily on complex or refractory cases, she added. Ways to help broaden care include developing point-of-care testing for STIs and improving the accuracy of existing testing, she said.

“The goal is to make routine sexual health services accessible in a wide range of settings, such as in primary care, at pharmacies, and in community-based settings, and to draw on a broader workforce for delivery of sexual health services,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview.

Kevin Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of clinical and translational research at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that many medical organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have long advocated incorporating sexual health into routine preventive care. He also noted that pharmacists have already become proactive in preventing STIs and could continue to do so.

“Vaccines for hepatitis and human papillomavirus are commonly available at pharmacies,” Dr. Ault said. He was not involved in the article by Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and colleagues or the original report. “Pharmacists could also fill a gap by administering injectable medications such as penicillin. States would have to approve changes in policy, but many states have already done this for expedited partner therapy.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser noted similar barriers that must be removed to broaden delivery of STI services.

“Unfortunately, too many highly trained health care providers who are well-positioned for the delivery of sexual health services face regulatory or administrative barriers to practice to the full scope of their training,” they wrote. “These barriers can have a particularly negative impact in medically underserved communities, where physician shortages are common and where novel, decentralized health care service delivery models that draw on nonphysician providers may hold the greatest promise.”

As more diverse health care practitioners take on these roles, ID and HIV specialists can provide their expertise in developing training and technical assistance to support generalists, Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They can also aid in aligning “clinical training curricula, licensing criteria, and practice guidelines with routine delivery of sexual health services.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthors offer specific recommendations for professional training, licensing, and practice guidelines to help overcome the “insufficient knowledge, inadequate training, and absence of explicit protocols” that currently impede delivery of STI services in general practice settings.

Although the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies is ambitious, it’s also necessary, and “none of the recommendations are out of reach,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview. They pointed out how the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how underresourced the health care workforce and infrastructure are and how great health care disparities are.

“There is momentum toward rebuilding the nation’s health and public health system in a more effective and efficient way,” they said, and many of the STI report’s recommendations “overlap with priorities for the broader health and public health system moving forward.”

Dr. Mercer also believes the recommendations are realistic, “but only the beginning,” she told this news organization. “Comprehensive sexual education to expand knowledge about STI prevention and public health campaigns to help destigmatize sexual health care in general will remain crucial,” she said.

Sexual education, expanded access, and destigmatizing sexual care are particularly important for reaching the populations most in need of care, such as adolescents and young adults, as well as ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender-minority youth.

“It cannot be overstated how important of a priority population adolescents and young adults are,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They noted that those aged 15-24 account for half of all STIs each year but represent only a quarter of the sexually active population. “Targeted efforts for STI prevention and treatment among adolescents and young adults are therefore essential for an overall successful strategy to address STIs and sexual health in the United States.”

The National Academies report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Dr. Mercer, Dr. Ault, and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Guilamo-Ramos has received grants and personal fees from ViiV Health care.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A vital aspect of expanding access and care for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the United States is broadening responsibility for this care across the health care system and other community resources, according to an article published online July 6 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. This expansion and decentralization of care are central to adopting the “new sexual health paradigm” recommended by a National Academies report that was published in March.

“STIs represent a sizable, longstanding, and growing public health challenge,” write Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, PhD, MPH, dean and professor at the Duke University School of Nursing and director of the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health (CLAFH) at Duke University, both in Durham, N.C., and his colleagues. Yet the limitations on the current STI workforce and limited federal funding and support for STI prevention and care mean it will take clinicians of all types from across the health care spectrum to meet the challenge, they explain.

“For too long, STI prevention and treatment has been perceived as the sole responsibility of a narrow workforce of specialized STI and HIV service providers,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthor, Marco Thimm-Kaiser, MPH, associate in research at Duke University and epidemiologist at CLAFH, wrote in an email.

“However, the resources allocated to this STI specialty workforce have diminished over time, along with decreasing investments in the broader U.S. public health infrastructure,” they continued. “At the same time – and in part due to this underinvestment – STI rates have soared, reaching a record high for the sixth year in a row in 2019.”

Those factors led to the National Academies report, which recommends moving “away from the traditional, disease-focused perspective on STIs in favor of a holistic perspective of sexual health as an integral component of overall health and well-being,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote to this news organization.

In their article, the authors review the limitations in the STI workforce, the implications of those limitations for the broader health care industry, and what it will take for STI and HIV specialists as well as regulators to ensure it’s possible to achieve the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies.

Currently, the biggest limitation is access to care, said Laura Mercer, MD, MBA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the ob.gyn. clerkship director at the University of Arizona, Phoenix. Dr. Mercer, who was not involved with the National Academies report or the analysis of it, said in an interview that it’s essential to emphasize “sexual health as a core element of routine primary and preventative care” to ensure it becomes more accessible to patients without the need to seek out specialty care.

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his colleagues drive home the importance of such a shift by noting that more than 200 million Americans live in counties with no practicing infectious disease physicians. The disparities are greatest in Southern states, which account for 40% of all reported STIs. The workforce shortage has continued to worsen alongside the deterioration of the clinical infrastructure supporting STI specialty services, the authors write.

Hence the need to expand accountability for care not only to primary-care physicians but also to nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and behavioral health practitioners. Doing so also requires normalizing sexual health services across health care professions.

“Prevention is a crucial first step” to this, Dr. Mercer said. “This is particularly important as we recall that almost half of new sexually transmitted infections occur in teenagers. Destigmatizing sexual health and sexual health education will also help encourage patients of all ages to request and accept testing.”

Further, with primary care practitioners managing most STI testing and treatment, subspecialists can focus primarily on complex or refractory cases, she added. Ways to help broaden care include developing point-of-care testing for STIs and improving the accuracy of existing testing, she said.

“The goal is to make routine sexual health services accessible in a wide range of settings, such as in primary care, at pharmacies, and in community-based settings, and to draw on a broader workforce for delivery of sexual health services,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview.

Kevin Ault, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and director of clinical and translational research at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, said that many medical organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have long advocated incorporating sexual health into routine preventive care. He also noted that pharmacists have already become proactive in preventing STIs and could continue to do so.

“Vaccines for hepatitis and human papillomavirus are commonly available at pharmacies,” Dr. Ault said. He was not involved in the article by Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and colleagues or the original report. “Pharmacists could also fill a gap by administering injectable medications such as penicillin. States would have to approve changes in policy, but many states have already done this for expedited partner therapy.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser noted similar barriers that must be removed to broaden delivery of STI services.

“Unfortunately, too many highly trained health care providers who are well-positioned for the delivery of sexual health services face regulatory or administrative barriers to practice to the full scope of their training,” they wrote. “These barriers can have a particularly negative impact in medically underserved communities, where physician shortages are common and where novel, decentralized health care service delivery models that draw on nonphysician providers may hold the greatest promise.”

As more diverse health care practitioners take on these roles, ID and HIV specialists can provide their expertise in developing training and technical assistance to support generalists, Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They can also aid in aligning “clinical training curricula, licensing criteria, and practice guidelines with routine delivery of sexual health services.”

Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and his coauthors offer specific recommendations for professional training, licensing, and practice guidelines to help overcome the “insufficient knowledge, inadequate training, and absence of explicit protocols” that currently impede delivery of STI services in general practice settings.

Although the paradigm shift recommended by the National Academies is ambitious, it’s also necessary, and “none of the recommendations are out of reach,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser said in an interview. They pointed out how the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how underresourced the health care workforce and infrastructure are and how great health care disparities are.

“There is momentum toward rebuilding the nation’s health and public health system in a more effective and efficient way,” they said, and many of the STI report’s recommendations “overlap with priorities for the broader health and public health system moving forward.”

Dr. Mercer also believes the recommendations are realistic, “but only the beginning,” she told this news organization. “Comprehensive sexual education to expand knowledge about STI prevention and public health campaigns to help destigmatize sexual health care in general will remain crucial,” she said.

Sexual education, expanded access, and destigmatizing sexual care are particularly important for reaching the populations most in need of care, such as adolescents and young adults, as well as ethnic, racial, sexual, and gender-minority youth.

“It cannot be overstated how important of a priority population adolescents and young adults are,” Dr. Guilamo-Ramos and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser wrote. They noted that those aged 15-24 account for half of all STIs each year but represent only a quarter of the sexually active population. “Targeted efforts for STI prevention and treatment among adolescents and young adults are therefore essential for an overall successful strategy to address STIs and sexual health in the United States.”

The National Academies report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Dr. Mercer, Dr. Ault, and Mr. Thimm-Kaiser have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Guilamo-Ramos has received grants and personal fees from ViiV Health care.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

C. diff eradication not necessary for clinical cure of recurrent infections with fecal transplant

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

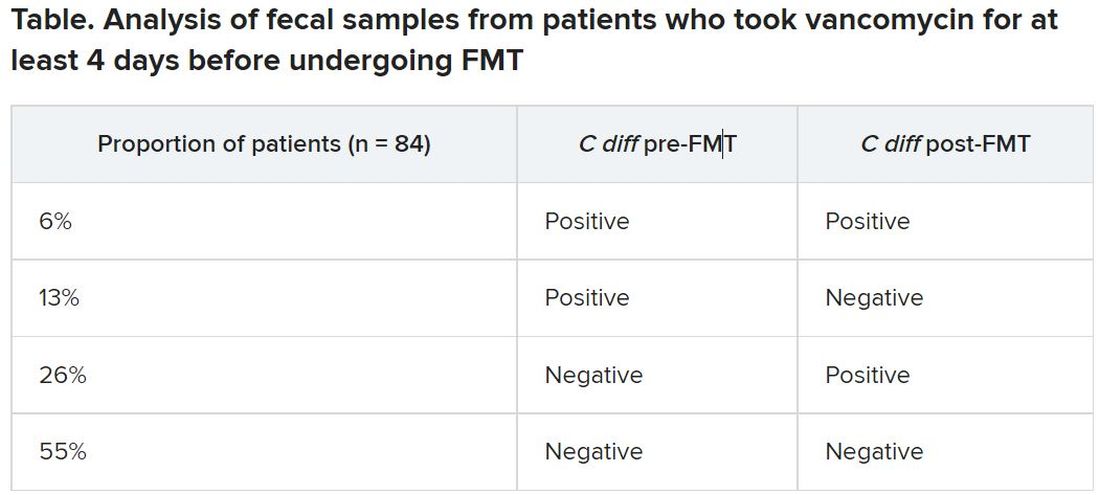

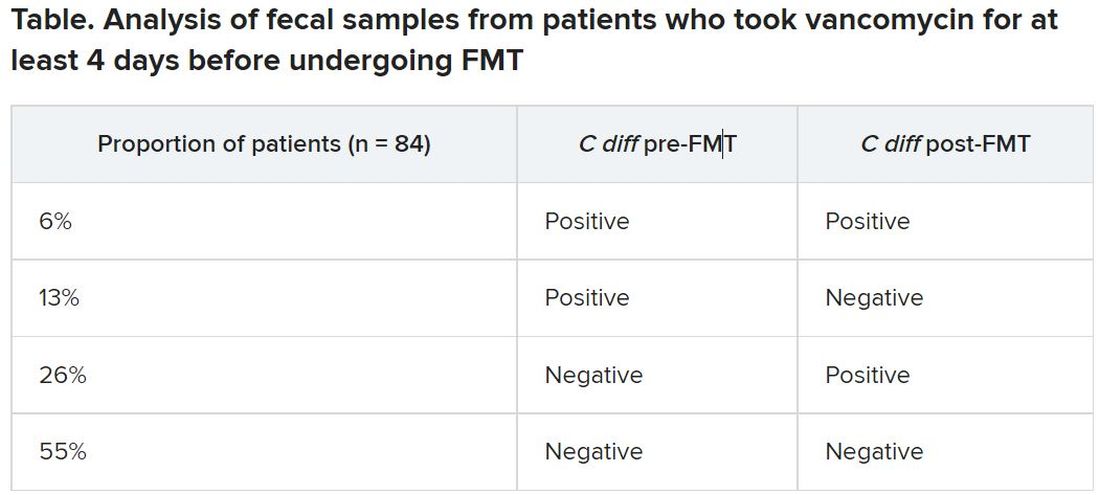

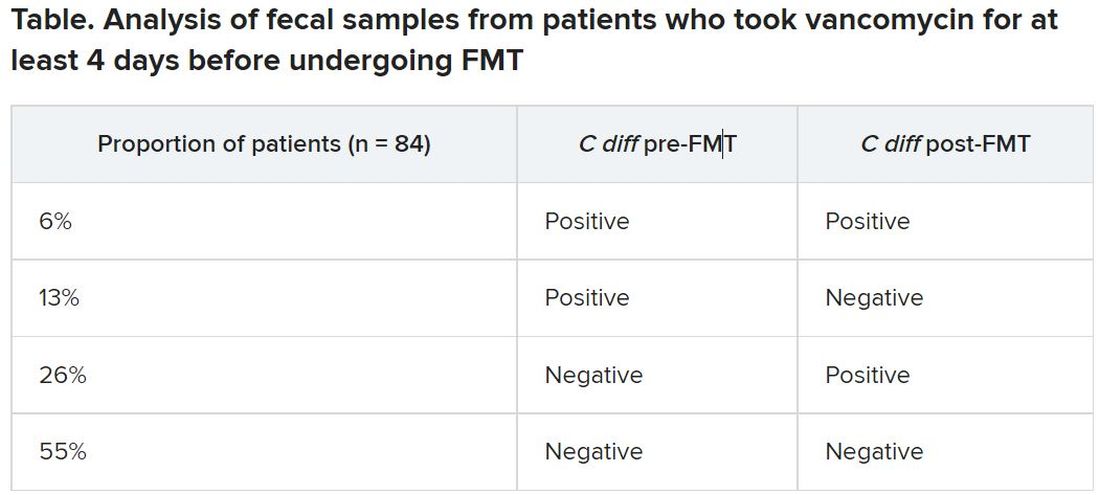

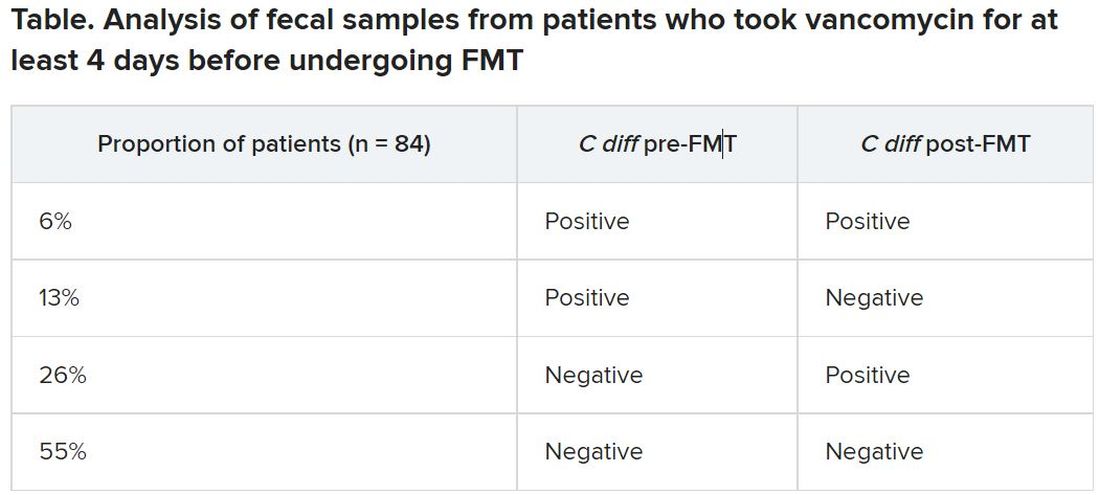

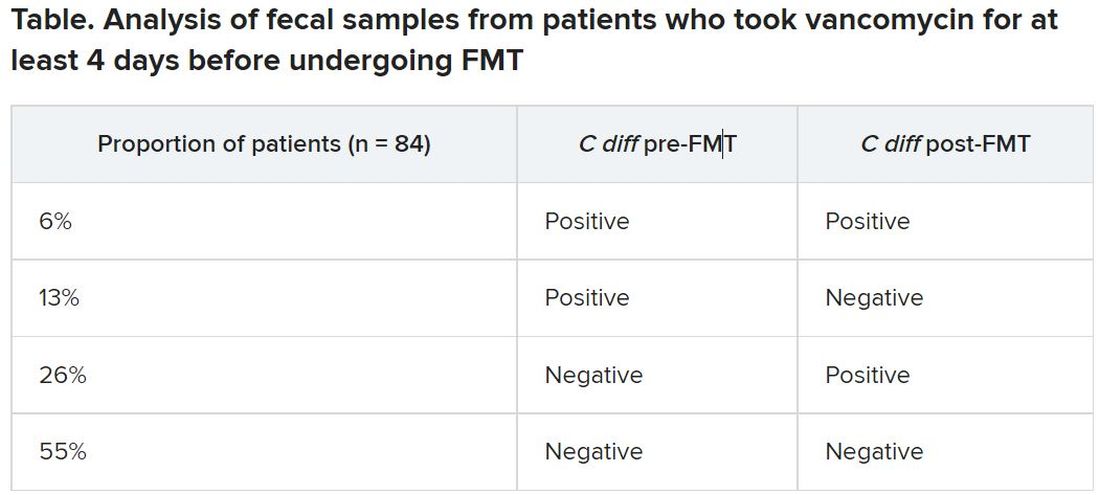

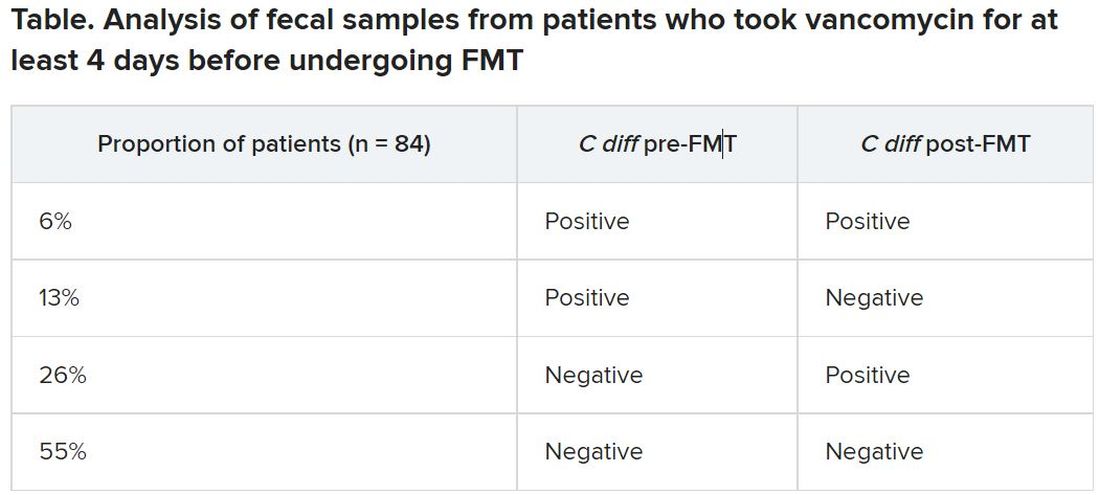

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hyperimmune globulin fails to prevent congenital CMV infection

Administering hyperimmune globulin to pregnant women who tested positive for cytomegalovirus did not reduce CMV infections or deaths among their fetuses or newborns, according to a randomized controlled trial published online July 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Up to 40,000 infants a year have congenital CMV infections, which can lead to stillbirth, neonatal death, deafness, and cognitive and motor delay. An estimated 35%-40% of fetuses of women with a primary CMV infection will develop an infection, write Brenna Hughes, MD, an associate professor of ob/gyn and chief of the division of maternal fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

Previous trials and observational studies have shown mixed results with hyperimmune globulin for the prevention of congenital CMV infection.

“It was surprising to us that none of the outcomes in this trial were in the direction of potential benefit,” Dr. Hughes told this news organization. “However, this is why it is important to do large trials in a diverse population.”

The study cohort comprised 206,082 pregnant women who were screened for CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation. Of those women, 712 (0.35%) tested positive for CMV. The researchers enrolled 399 women who had tested positive and randomly assigned them to receive either a monthly infusion of CMV hyperimmune globulin (100 mg/kg) or placebo until delivery. The researchers used a composite of CMV infection or, if no testing occurred, fetal/neonatal death as the primary endpoint.

The trial was stopped early for futility when data from 394 participants revealed that 22.7% of offspring in the hyperimmune globulin group and 19.4% of those in the placebo group had had a CMV infection or had died (relative risk = 1.17; P = .42).

When individual endpoints were examined, trends were detected in favor of the placebo, but they did not reach statistical significance. The incidence of death was higher in the hyperimmune globulin group (4.9%) than in the placebo group (2.6%). The rate of preterm birth was also higher in the intervention group (12.2%) than in the group that received placebo (8.3%). The incidence of birth weight below the fifth percentile was 10.3% in the intervention group and 5.4% in the placebo group.

One woman who received hyperimmune globulin experienced a severe allergic reaction to the first infusion. Additionally, more women in the hyperimmune globulin group experienced headaches and shaking chills during infusions than did those who received placebo. There were no differences in maternal outcomes between the groups. There were no thromboembolic or ischemic events in either group.

“These findings suggest CMV hyperimmune globulin should not be used for the prevention of congenital CMV in pregnant patients with primary CMV during pregnancy,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

“A CMV vaccine is likely to be the most effective public health measure that we can offer, and that should be at the forefront of research investments,” she said. “But some of the other medications that work against CMV should be tested on a large scale as well,” she said. For example, a small trial in Israel showed that high-dose valacyclovir in early pregnancy decreased congenital CMV, and thus the drug merits study in a larger trial, she said.

Other experts agree that developing a vaccine should be the priority.

“The ultimate goal for preventing the brain damage and birth defects caused by congenital CMV infection is a vaccine that is as effective as the rubella vaccine has been for eliminating congenital rubella syndrome and that can be given well before pregnancy,” said Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and the New York–Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital in New York.

“While trials of vaccines are ongoing, there is a need to have a therapeutic option, especially for the high-risk setting of a mother acquiring the virus for the first time during pregnancy,” Dr. Permar said in an interview.

Dr. Permar was not involved in this study but is involved in follow-up studies of this cohort and is conducting research on CMV maternal vaccines. She noted the need for safe, effective antiviral treatments and for research into newer immunoglobulin products, such as monoclonal antibodies.

Both Dr. Permar and Dr. Hughes highlighted the challenge of raising awareness about the danger of CMV infections during pregnancy.

“Pregnant women, and especially those who have or work with young children, who are frequently carriers of the infection, should be informed of this risk,” Dr. Permar said. She hopes universal testing of newborns will be implemented and that it enables people to recognize the frequency and burden of these infections. She remains optimistic about a vaccine.

“After 60 years of research into a CMV vaccine, I believe we are currently in a ‘golden age’ of CMV vaccine development,” she said. She noted that Moderna is about to launch a phase 3 mRNA vaccine trial for CMV. “Moreover, immune correlates of protection against CMV have been identified from previous partially effective vaccines, and animal models have improved for preclinical studies. Therefore, I believe we will have an effective and safe vaccine against this most common congenital infection in the coming years.”

The research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Hughes has served on Merck’s scientific advisory board. Various coauthors have received personal fees from Medela and nonfinancial support from Hologic; personal fees from Moderna and VBI vaccines, and grants from Novavax. Dr. Permar consults for Pfizer, Moderna, Merck, Sanofi, and Dynavax on their CMV vaccine programs, and she has a sponsored research program with Merck and Moderna on CMV vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Administering hyperimmune globulin to pregnant women who tested positive for cytomegalovirus did not reduce CMV infections or deaths among their fetuses or newborns, according to a randomized controlled trial published online July 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Up to 40,000 infants a year have congenital CMV infections, which can lead to stillbirth, neonatal death, deafness, and cognitive and motor delay. An estimated 35%-40% of fetuses of women with a primary CMV infection will develop an infection, write Brenna Hughes, MD, an associate professor of ob/gyn and chief of the division of maternal fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

Previous trials and observational studies have shown mixed results with hyperimmune globulin for the prevention of congenital CMV infection.

“It was surprising to us that none of the outcomes in this trial were in the direction of potential benefit,” Dr. Hughes told this news organization. “However, this is why it is important to do large trials in a diverse population.”

The study cohort comprised 206,082 pregnant women who were screened for CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation. Of those women, 712 (0.35%) tested positive for CMV. The researchers enrolled 399 women who had tested positive and randomly assigned them to receive either a monthly infusion of CMV hyperimmune globulin (100 mg/kg) or placebo until delivery. The researchers used a composite of CMV infection or, if no testing occurred, fetal/neonatal death as the primary endpoint.

The trial was stopped early for futility when data from 394 participants revealed that 22.7% of offspring in the hyperimmune globulin group and 19.4% of those in the placebo group had had a CMV infection or had died (relative risk = 1.17; P = .42).

When individual endpoints were examined, trends were detected in favor of the placebo, but they did not reach statistical significance. The incidence of death was higher in the hyperimmune globulin group (4.9%) than in the placebo group (2.6%). The rate of preterm birth was also higher in the intervention group (12.2%) than in the group that received placebo (8.3%). The incidence of birth weight below the fifth percentile was 10.3% in the intervention group and 5.4% in the placebo group.

One woman who received hyperimmune globulin experienced a severe allergic reaction to the first infusion. Additionally, more women in the hyperimmune globulin group experienced headaches and shaking chills during infusions than did those who received placebo. There were no differences in maternal outcomes between the groups. There were no thromboembolic or ischemic events in either group.

“These findings suggest CMV hyperimmune globulin should not be used for the prevention of congenital CMV in pregnant patients with primary CMV during pregnancy,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

“A CMV vaccine is likely to be the most effective public health measure that we can offer, and that should be at the forefront of research investments,” she said. “But some of the other medications that work against CMV should be tested on a large scale as well,” she said. For example, a small trial in Israel showed that high-dose valacyclovir in early pregnancy decreased congenital CMV, and thus the drug merits study in a larger trial, she said.

Other experts agree that developing a vaccine should be the priority.

“The ultimate goal for preventing the brain damage and birth defects caused by congenital CMV infection is a vaccine that is as effective as the rubella vaccine has been for eliminating congenital rubella syndrome and that can be given well before pregnancy,” said Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and the New York–Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital in New York.

“While trials of vaccines are ongoing, there is a need to have a therapeutic option, especially for the high-risk setting of a mother acquiring the virus for the first time during pregnancy,” Dr. Permar said in an interview.

Dr. Permar was not involved in this study but is involved in follow-up studies of this cohort and is conducting research on CMV maternal vaccines. She noted the need for safe, effective antiviral treatments and for research into newer immunoglobulin products, such as monoclonal antibodies.

Both Dr. Permar and Dr. Hughes highlighted the challenge of raising awareness about the danger of CMV infections during pregnancy.

“Pregnant women, and especially those who have or work with young children, who are frequently carriers of the infection, should be informed of this risk,” Dr. Permar said. She hopes universal testing of newborns will be implemented and that it enables people to recognize the frequency and burden of these infections. She remains optimistic about a vaccine.

“After 60 years of research into a CMV vaccine, I believe we are currently in a ‘golden age’ of CMV vaccine development,” she said. She noted that Moderna is about to launch a phase 3 mRNA vaccine trial for CMV. “Moreover, immune correlates of protection against CMV have been identified from previous partially effective vaccines, and animal models have improved for preclinical studies. Therefore, I believe we will have an effective and safe vaccine against this most common congenital infection in the coming years.”

The research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Hughes has served on Merck’s scientific advisory board. Various coauthors have received personal fees from Medela and nonfinancial support from Hologic; personal fees from Moderna and VBI vaccines, and grants from Novavax. Dr. Permar consults for Pfizer, Moderna, Merck, Sanofi, and Dynavax on their CMV vaccine programs, and she has a sponsored research program with Merck and Moderna on CMV vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Administering hyperimmune globulin to pregnant women who tested positive for cytomegalovirus did not reduce CMV infections or deaths among their fetuses or newborns, according to a randomized controlled trial published online July 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Up to 40,000 infants a year have congenital CMV infections, which can lead to stillbirth, neonatal death, deafness, and cognitive and motor delay. An estimated 35%-40% of fetuses of women with a primary CMV infection will develop an infection, write Brenna Hughes, MD, an associate professor of ob/gyn and chief of the division of maternal fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

Previous trials and observational studies have shown mixed results with hyperimmune globulin for the prevention of congenital CMV infection.

“It was surprising to us that none of the outcomes in this trial were in the direction of potential benefit,” Dr. Hughes told this news organization. “However, this is why it is important to do large trials in a diverse population.”

The study cohort comprised 206,082 pregnant women who were screened for CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation. Of those women, 712 (0.35%) tested positive for CMV. The researchers enrolled 399 women who had tested positive and randomly assigned them to receive either a monthly infusion of CMV hyperimmune globulin (100 mg/kg) or placebo until delivery. The researchers used a composite of CMV infection or, if no testing occurred, fetal/neonatal death as the primary endpoint.

The trial was stopped early for futility when data from 394 participants revealed that 22.7% of offspring in the hyperimmune globulin group and 19.4% of those in the placebo group had had a CMV infection or had died (relative risk = 1.17; P = .42).

When individual endpoints were examined, trends were detected in favor of the placebo, but they did not reach statistical significance. The incidence of death was higher in the hyperimmune globulin group (4.9%) than in the placebo group (2.6%). The rate of preterm birth was also higher in the intervention group (12.2%) than in the group that received placebo (8.3%). The incidence of birth weight below the fifth percentile was 10.3% in the intervention group and 5.4% in the placebo group.

One woman who received hyperimmune globulin experienced a severe allergic reaction to the first infusion. Additionally, more women in the hyperimmune globulin group experienced headaches and shaking chills during infusions than did those who received placebo. There were no differences in maternal outcomes between the groups. There were no thromboembolic or ischemic events in either group.

“These findings suggest CMV hyperimmune globulin should not be used for the prevention of congenital CMV in pregnant patients with primary CMV during pregnancy,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

“A CMV vaccine is likely to be the most effective public health measure that we can offer, and that should be at the forefront of research investments,” she said. “But some of the other medications that work against CMV should be tested on a large scale as well,” she said. For example, a small trial in Israel showed that high-dose valacyclovir in early pregnancy decreased congenital CMV, and thus the drug merits study in a larger trial, she said.

Other experts agree that developing a vaccine should be the priority.

“The ultimate goal for preventing the brain damage and birth defects caused by congenital CMV infection is a vaccine that is as effective as the rubella vaccine has been for eliminating congenital rubella syndrome and that can be given well before pregnancy,” said Sallie Permar, MD, PhD, chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and the New York–Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital in New York.

“While trials of vaccines are ongoing, there is a need to have a therapeutic option, especially for the high-risk setting of a mother acquiring the virus for the first time during pregnancy,” Dr. Permar said in an interview.

Dr. Permar was not involved in this study but is involved in follow-up studies of this cohort and is conducting research on CMV maternal vaccines. She noted the need for safe, effective antiviral treatments and for research into newer immunoglobulin products, such as monoclonal antibodies.

Both Dr. Permar and Dr. Hughes highlighted the challenge of raising awareness about the danger of CMV infections during pregnancy.

“Pregnant women, and especially those who have or work with young children, who are frequently carriers of the infection, should be informed of this risk,” Dr. Permar said. She hopes universal testing of newborns will be implemented and that it enables people to recognize the frequency and burden of these infections. She remains optimistic about a vaccine.

“After 60 years of research into a CMV vaccine, I believe we are currently in a ‘golden age’ of CMV vaccine development,” she said. She noted that Moderna is about to launch a phase 3 mRNA vaccine trial for CMV. “Moreover, immune correlates of protection against CMV have been identified from previous partially effective vaccines, and animal models have improved for preclinical studies. Therefore, I believe we will have an effective and safe vaccine against this most common congenital infection in the coming years.”

The research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Hughes has served on Merck’s scientific advisory board. Various coauthors have received personal fees from Medela and nonfinancial support from Hologic; personal fees from Moderna and VBI vaccines, and grants from Novavax. Dr. Permar consults for Pfizer, Moderna, Merck, Sanofi, and Dynavax on their CMV vaccine programs, and she has a sponsored research program with Merck and Moderna on CMV vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

C. Diff eradication not necessary for clinical cure of recurrent infections with fecal transplant

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID seen in patients with severe and mild disease

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

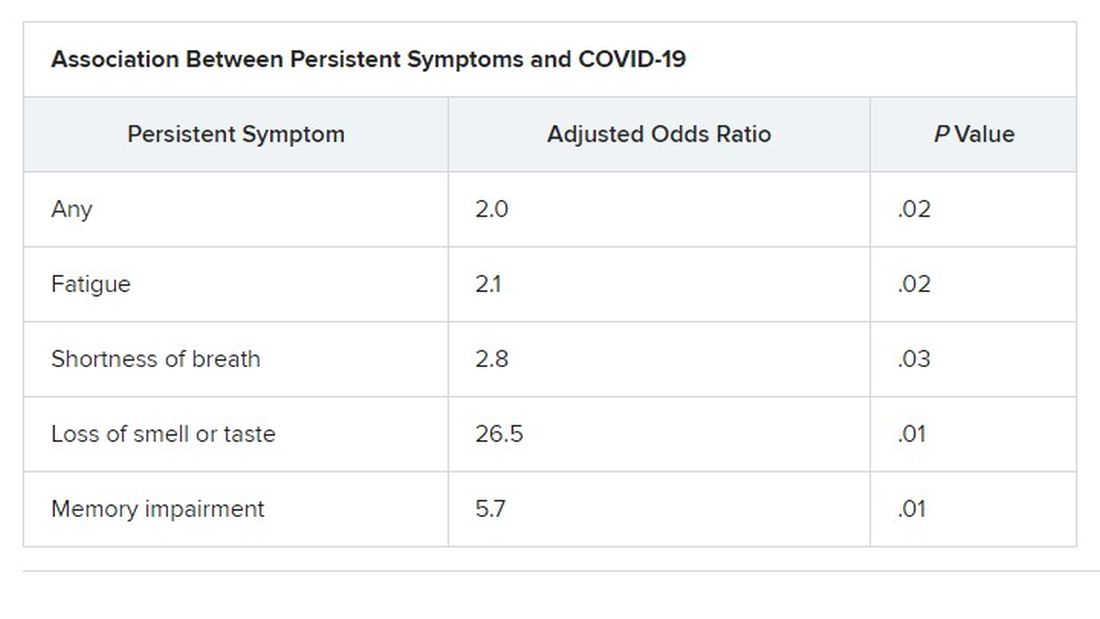

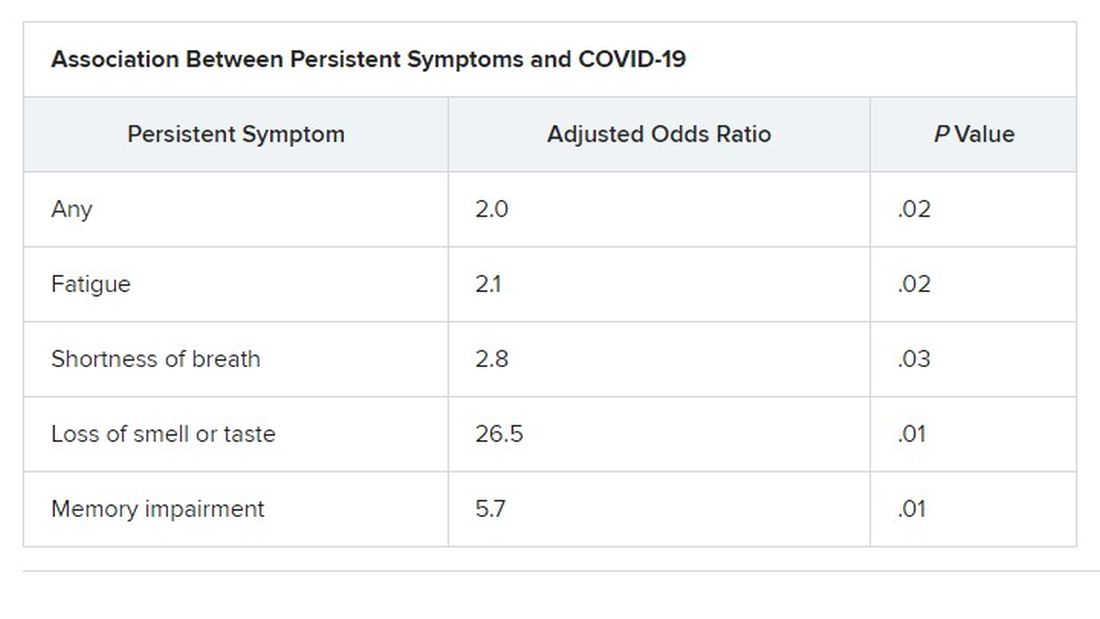

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.