User login

C. diff eradication not necessary for clinical cure of recurrent infections with fecal transplant

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

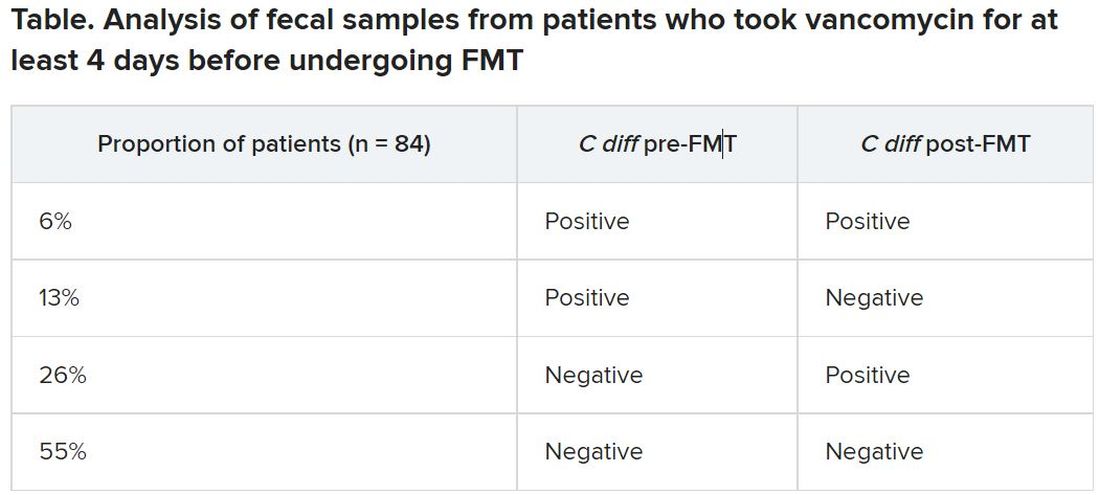

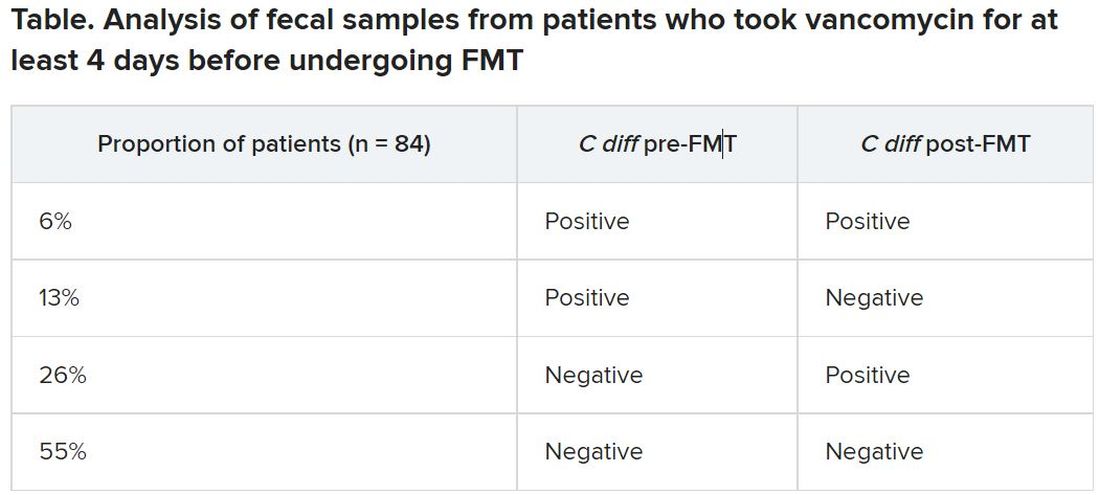

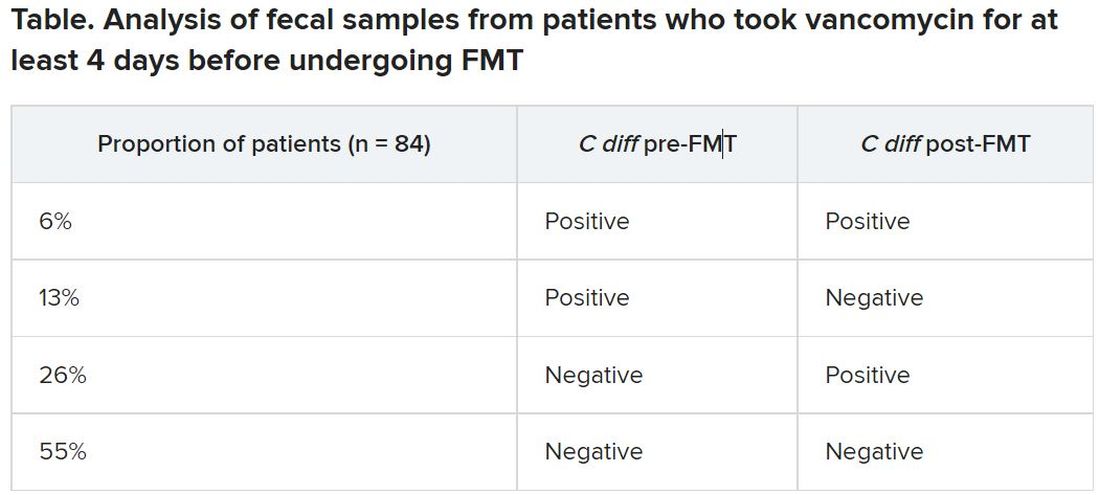

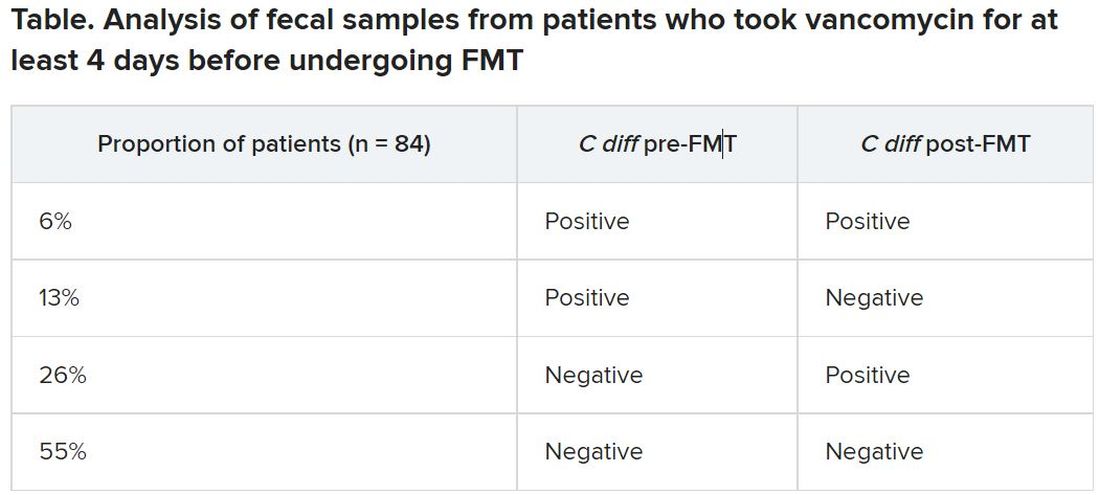

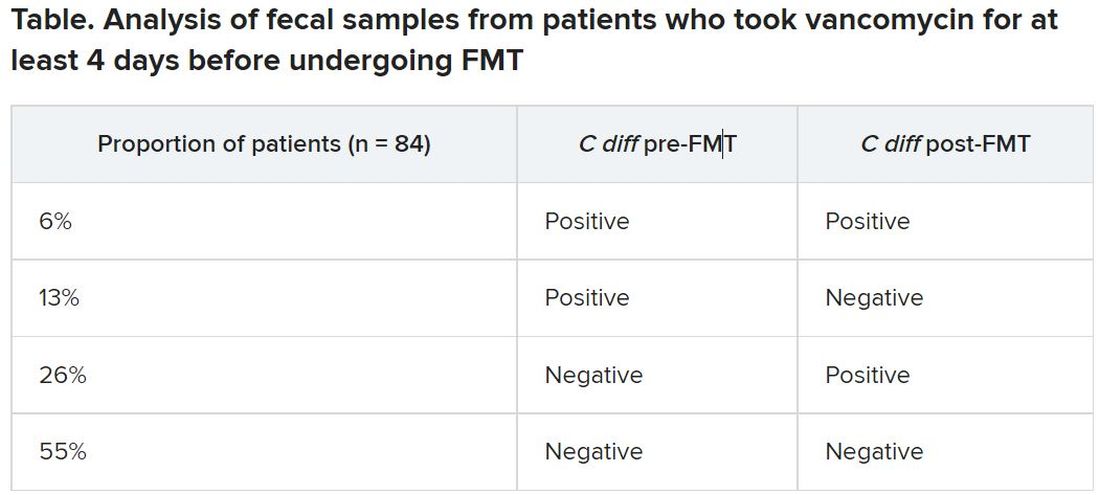

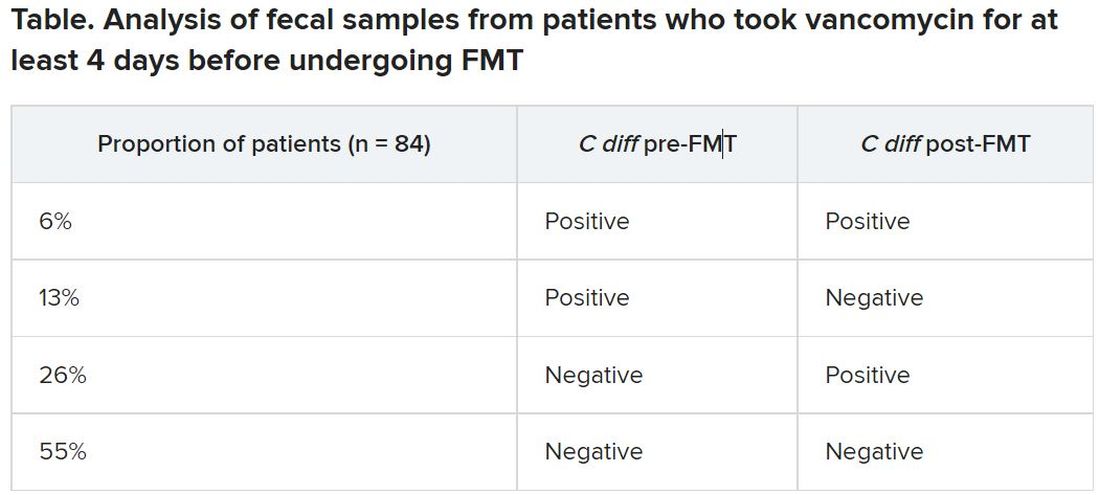

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

Help your patients understand their C. difficile diagnosis by sharing patient education from the AGA GI Patient Center: www.gastro.org/Cdiff.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

C. Diff eradication not necessary for clinical cure of recurrent infections with fecal transplant

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not necessary to completely eradicate all Clostridioides difficile to successfully treat recurrent C. difficile infections with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), according to a study presented online July 12 at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

C. difficile colonization persisted for 3 weeks after FMT in about one-quarter of patients, but it’s not clear whether this is a persistent infection, a newly acquired infection, or partial persistence of a mixed infection, said Elisabeth Terveer, MD, a medical microbiologist at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center. In addition, “82% of patients with detectable C. diff do not relapse, so it’s absolutely not necessary for a cure,” she said.

Several mechanisms explain why FMT is a highly effective therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections, including restoration of bacterial metabolism in the gut, immune modulation, and direct competition between bacteria, Dr. Terveer said, but it’s less clear whether eradication of C. difficile spores is among these mechanisms.

Between May 2016 and April 2020, the researchers analyzed fecal samples from 84 patients who took vancomycin for at least 4 days before undergoing FMT. The researchers took fecal samples from patients before FMT and 3 weeks after FMT to culture them and the donor samples for presence of C. difficile, and they assessed clinical outcomes at 3 weeks and 6 months after FMT.

After antibiotic treatment but prior to FMT, 19% of patients (n = 16) still had a toxigenic C. difficile culture while the other 81% had a negative culture. None of the donor samples had a positive C. difficile culture. After FMT treatment, five patients who had a positive pre-FMT culture remained positive, and the other 11 were negative. Among the 81% of patients (n = 68) who had a negative culture just before FMT, 22 had a positive culture and 46 had a negative culture after FMT. Overall, 26% of patients post FMT had a positive C. difficile culture, a finding that was 10-fold higher than another study that assessed C. difficile with PCR testing, Dr. Terveer said.

The clinical cure rate after FMT was 94%, and five patients had relapses within 2 months of their FMT. These relapses were more prevalent in patients with a positive C. difficile culture prior to FMT (odds ratio [OR], 7.6; P = .045) and a positive C. difficile culture after FMT (OR, 13.6; P = .016). Still, 82% of patients who had a positive C. difficile culture post FMT remained clinically cured 2 months later.

It’s unclear why 19% of patients had a positive culture after their antibiotic pretreatment prior to FMT, Dr. Terveer said, but it may be because the pretreatment was of such a short duration.

“I think the advice should be: Give a full anti–C. diff antibiotic course to treat the C. diff infection, and then give FMT afterward to restore the microbiota and prevent further relapses,” Dr. Terveer told attendees.

Dimitri Drekonja, MD, chief of the Minneapolis VA Infectious Disease Section, said the findings were not necessarily surprising, but it would have been interesting for the researchers to have conducted DNA sequencing of the patients’ fecal samples post FMT to see what the biological diversity looked like.

“One school of thought has been that you have to repopulate the normal diverse microbiota of the colon” with FMT, and the other “is that you need to get rid of the C. diff that›s there,” Dr. Drekonja, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “I think more people think it’s the diverse microbiota because if it’s just getting rid of C. diff, we can get do that with antibiotics – but that gets rid of the other organisms.”

As long as you have a diverse microbiota post FMT, Dr. Drekonja said, then “having a few residual organisms, even if they get magnified in the culture process, is probably not that big a deal.”

But there’s a third school of thought that Dr. Drekonja said he himself falls into: “I don’t really care how it works, just that in well-done trials, it does work.” As long as large, robust, well-blinded trials show that FMT works, “I’m open to all sorts of ideas of what the mechanism is,” he said. “The main thing is that it does or doesn’t work.”

These findings basically reinforce current guidance not to test patients’ stools if they are asymptomatic, Dr. Drekonja said. In the past, clinicians sometimes tested patients’ stool after therapy to ensure the C. difficile was eradicated, regardless of whether the patient had symptoms of infection, he said.

“We’ve since become much more attuned that there are lots of people who have detectable C. diff in their stool without any symptoms,” whether detectable by culture or PCR, Dr. Drekonja said. “Generally, if you’re doing well and you’re not having diarrhea, don’t test, and if someone does test and finds it, pretend you didn’t see the test,” he advised. “This is a big part of diagnostic stewardship, which is: You don’t go testing people who are doing well.”

The Netherlands Donor Feces Bank used in the research is funded by a grant from Vedanta Biosciences. Dr. Drekonja had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID symptoms reported by 6% of pediatric patients

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.