User login

Family violence patterns change during pandemic

Among adolescents treated for injuries caused by family-member violence, the proportion of incidents that involved illegal drugs or weapons more than doubled during the pandemic, and incidents that involved alcohol nearly doubled, according to data presented October 10 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“The COVID-19 pandemic amplified risk factors known to increase family interpersonal violence, such as increased need for parental supervision, parental stress, financial hardship, poor mental health, and isolation,” said investigator Mattea Miller, an MD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

To examine the issue, she and her colleagues “sought to characterize the prevalence and circumstances of adolescent injuries resulting from family interpersonal violence,” Ms. Miller told this news organization.

Their retrospective analysis involved children 10 to 15 years of age seen before or during the pandemic in the emergency department at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center for injuries that resulted from a violent incident with a family member.

Of the 819 incidents of violence-related injuries seen during the study period – the prepandemic ran from Jan. 1, 2019 to March 29, 2020, and the pandemic period ran from March 30, 2020, the date a stay-at-home order was first issued in Maryland, to Dec. 31, 2020 – 448 (54.7%) involved a family member. The proportion of such injuries was similar before and during the pandemic (54.6% vs. 54.9%; P = .99).

Most (83.9%) of these incidents occurred at home, 76.6% involved a parent or guardian, and 66.7% involved the youth being transported to the hospital by police.

It is surprising that families accounted for such a high level of violence involving adolescents, said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“The most common source of child physical abuse in younger children – infants and toddlers – [is the] parents,” who account for about 75% of cases, “but to see that amount of violence in adolescents was unexpected,” he told this news organization.

Patients in the study cohort were more likely to be Black than the hospital’s overall emergency-department population (84.4% vs. 60.0%), and more likely to be covered by public insurance (71.2% vs. 60.0%).

In the study cohort, 54.0% of the patients were female.

“We were surprised to see that 8% of visits did not have a referral to a social worker” – 92% of patients in the study cohort received a social work consult during their visit to the emergency department – and that number “did not vary during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Miller said. The pandemic exacerbated the types of stresses that social workers can help address, so “this potentially represents a gap in care that is important to address,” she added.

Increase in use of alcohol, drugs, weapons

The most significant increases from the prepandemic period to the pandemic period were in incidents that involved alcohol (10.0% vs. 18.8%; P ≤ .001), illegal drugs (6.5% vs. 14.9%; P ≤ .001), and weapons, most often a knife (10.7% vs. 23.8%; P ≤ .001).

“An obvious potential explanation for the increase in alcohol, drug, and weapons [involvement] would be the mental health impact of the pandemic in conjunction with the economic stressors that some families may be feeling,” Dr. Greeley said. Teachers are the most common reporters of child abuse, so it’s possible that reports of violence decreased when schools switched to remote learning. But with most schools back to in-person learning, data have not yet shown a surge in reporting, he noted.

The “epidemiology of family violence may be impacted by increased time at home, disruptions in school and family routines, exacerbations in mental health conditions, and financial stresses common during the pandemic,” said senior study investigator Leticia Ryan, MD, MPH, director of research in pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

And research has shown increases in the use of alcohol and illegal drugs during the pandemic, she noted.

“As we transition to postpandemic life, it will be important to identify at-risk adolescents and families and provide supports,” Dr. Ryan told this news organization. “The emergency department is an appropriate setting to intervene with youth who have experienced family violence and initiate preventive strategies to avoid future violence.”

Among the strategies to identify and intervene for at-risk patients is the CRAFFT substance use screening tool. Furthermore, “case management, involvement of child protection services, and linkage with relevant support services may all be appropriate, depending on circumstances,” Ms. Miller added.

“Exposure to family violence at a young age increases the likelihood that a child will be exposed to additional violence or become a perpetrator of violence in the future, continuing a cycle of violence,” Ms. Miller explained. “Given that studies of adolescent violence often focus on peer violence, a better understanding of the epidemiology of violence-related injuries resulting from family violence is needed to better inform the development of more comprehensive prevention strategies.”

This study did not note any external funding. Ms. Miller, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Ryan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adolescents treated for injuries caused by family-member violence, the proportion of incidents that involved illegal drugs or weapons more than doubled during the pandemic, and incidents that involved alcohol nearly doubled, according to data presented October 10 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“The COVID-19 pandemic amplified risk factors known to increase family interpersonal violence, such as increased need for parental supervision, parental stress, financial hardship, poor mental health, and isolation,” said investigator Mattea Miller, an MD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

To examine the issue, she and her colleagues “sought to characterize the prevalence and circumstances of adolescent injuries resulting from family interpersonal violence,” Ms. Miller told this news organization.

Their retrospective analysis involved children 10 to 15 years of age seen before or during the pandemic in the emergency department at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center for injuries that resulted from a violent incident with a family member.

Of the 819 incidents of violence-related injuries seen during the study period – the prepandemic ran from Jan. 1, 2019 to March 29, 2020, and the pandemic period ran from March 30, 2020, the date a stay-at-home order was first issued in Maryland, to Dec. 31, 2020 – 448 (54.7%) involved a family member. The proportion of such injuries was similar before and during the pandemic (54.6% vs. 54.9%; P = .99).

Most (83.9%) of these incidents occurred at home, 76.6% involved a parent or guardian, and 66.7% involved the youth being transported to the hospital by police.

It is surprising that families accounted for such a high level of violence involving adolescents, said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“The most common source of child physical abuse in younger children – infants and toddlers – [is the] parents,” who account for about 75% of cases, “but to see that amount of violence in adolescents was unexpected,” he told this news organization.

Patients in the study cohort were more likely to be Black than the hospital’s overall emergency-department population (84.4% vs. 60.0%), and more likely to be covered by public insurance (71.2% vs. 60.0%).

In the study cohort, 54.0% of the patients were female.

“We were surprised to see that 8% of visits did not have a referral to a social worker” – 92% of patients in the study cohort received a social work consult during their visit to the emergency department – and that number “did not vary during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Miller said. The pandemic exacerbated the types of stresses that social workers can help address, so “this potentially represents a gap in care that is important to address,” she added.

Increase in use of alcohol, drugs, weapons

The most significant increases from the prepandemic period to the pandemic period were in incidents that involved alcohol (10.0% vs. 18.8%; P ≤ .001), illegal drugs (6.5% vs. 14.9%; P ≤ .001), and weapons, most often a knife (10.7% vs. 23.8%; P ≤ .001).

“An obvious potential explanation for the increase in alcohol, drug, and weapons [involvement] would be the mental health impact of the pandemic in conjunction with the economic stressors that some families may be feeling,” Dr. Greeley said. Teachers are the most common reporters of child abuse, so it’s possible that reports of violence decreased when schools switched to remote learning. But with most schools back to in-person learning, data have not yet shown a surge in reporting, he noted.

The “epidemiology of family violence may be impacted by increased time at home, disruptions in school and family routines, exacerbations in mental health conditions, and financial stresses common during the pandemic,” said senior study investigator Leticia Ryan, MD, MPH, director of research in pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

And research has shown increases in the use of alcohol and illegal drugs during the pandemic, she noted.

“As we transition to postpandemic life, it will be important to identify at-risk adolescents and families and provide supports,” Dr. Ryan told this news organization. “The emergency department is an appropriate setting to intervene with youth who have experienced family violence and initiate preventive strategies to avoid future violence.”

Among the strategies to identify and intervene for at-risk patients is the CRAFFT substance use screening tool. Furthermore, “case management, involvement of child protection services, and linkage with relevant support services may all be appropriate, depending on circumstances,” Ms. Miller added.

“Exposure to family violence at a young age increases the likelihood that a child will be exposed to additional violence or become a perpetrator of violence in the future, continuing a cycle of violence,” Ms. Miller explained. “Given that studies of adolescent violence often focus on peer violence, a better understanding of the epidemiology of violence-related injuries resulting from family violence is needed to better inform the development of more comprehensive prevention strategies.”

This study did not note any external funding. Ms. Miller, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Ryan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among adolescents treated for injuries caused by family-member violence, the proportion of incidents that involved illegal drugs or weapons more than doubled during the pandemic, and incidents that involved alcohol nearly doubled, according to data presented October 10 at the American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 National Conference.

“The COVID-19 pandemic amplified risk factors known to increase family interpersonal violence, such as increased need for parental supervision, parental stress, financial hardship, poor mental health, and isolation,” said investigator Mattea Miller, an MD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

To examine the issue, she and her colleagues “sought to characterize the prevalence and circumstances of adolescent injuries resulting from family interpersonal violence,” Ms. Miller told this news organization.

Their retrospective analysis involved children 10 to 15 years of age seen before or during the pandemic in the emergency department at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center for injuries that resulted from a violent incident with a family member.

Of the 819 incidents of violence-related injuries seen during the study period – the prepandemic ran from Jan. 1, 2019 to March 29, 2020, and the pandemic period ran from March 30, 2020, the date a stay-at-home order was first issued in Maryland, to Dec. 31, 2020 – 448 (54.7%) involved a family member. The proportion of such injuries was similar before and during the pandemic (54.6% vs. 54.9%; P = .99).

Most (83.9%) of these incidents occurred at home, 76.6% involved a parent or guardian, and 66.7% involved the youth being transported to the hospital by police.

It is surprising that families accounted for such a high level of violence involving adolescents, said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“The most common source of child physical abuse in younger children – infants and toddlers – [is the] parents,” who account for about 75% of cases, “but to see that amount of violence in adolescents was unexpected,” he told this news organization.

Patients in the study cohort were more likely to be Black than the hospital’s overall emergency-department population (84.4% vs. 60.0%), and more likely to be covered by public insurance (71.2% vs. 60.0%).

In the study cohort, 54.0% of the patients were female.

“We were surprised to see that 8% of visits did not have a referral to a social worker” – 92% of patients in the study cohort received a social work consult during their visit to the emergency department – and that number “did not vary during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Miller said. The pandemic exacerbated the types of stresses that social workers can help address, so “this potentially represents a gap in care that is important to address,” she added.

Increase in use of alcohol, drugs, weapons

The most significant increases from the prepandemic period to the pandemic period were in incidents that involved alcohol (10.0% vs. 18.8%; P ≤ .001), illegal drugs (6.5% vs. 14.9%; P ≤ .001), and weapons, most often a knife (10.7% vs. 23.8%; P ≤ .001).

“An obvious potential explanation for the increase in alcohol, drug, and weapons [involvement] would be the mental health impact of the pandemic in conjunction with the economic stressors that some families may be feeling,” Dr. Greeley said. Teachers are the most common reporters of child abuse, so it’s possible that reports of violence decreased when schools switched to remote learning. But with most schools back to in-person learning, data have not yet shown a surge in reporting, he noted.

The “epidemiology of family violence may be impacted by increased time at home, disruptions in school and family routines, exacerbations in mental health conditions, and financial stresses common during the pandemic,” said senior study investigator Leticia Ryan, MD, MPH, director of research in pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

And research has shown increases in the use of alcohol and illegal drugs during the pandemic, she noted.

“As we transition to postpandemic life, it will be important to identify at-risk adolescents and families and provide supports,” Dr. Ryan told this news organization. “The emergency department is an appropriate setting to intervene with youth who have experienced family violence and initiate preventive strategies to avoid future violence.”

Among the strategies to identify and intervene for at-risk patients is the CRAFFT substance use screening tool. Furthermore, “case management, involvement of child protection services, and linkage with relevant support services may all be appropriate, depending on circumstances,” Ms. Miller added.

“Exposure to family violence at a young age increases the likelihood that a child will be exposed to additional violence or become a perpetrator of violence in the future, continuing a cycle of violence,” Ms. Miller explained. “Given that studies of adolescent violence often focus on peer violence, a better understanding of the epidemiology of violence-related injuries resulting from family violence is needed to better inform the development of more comprehensive prevention strategies.”

This study did not note any external funding. Ms. Miller, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Ryan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abaloparatide significantly reduced fractures, increased BMD in women at high fracture risk

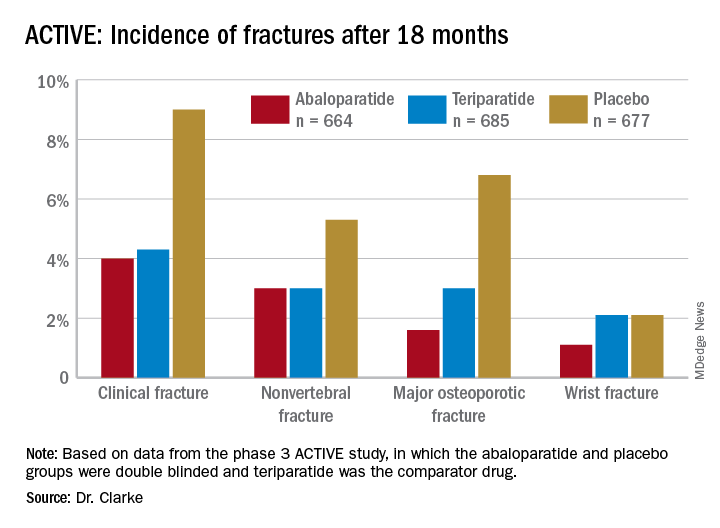

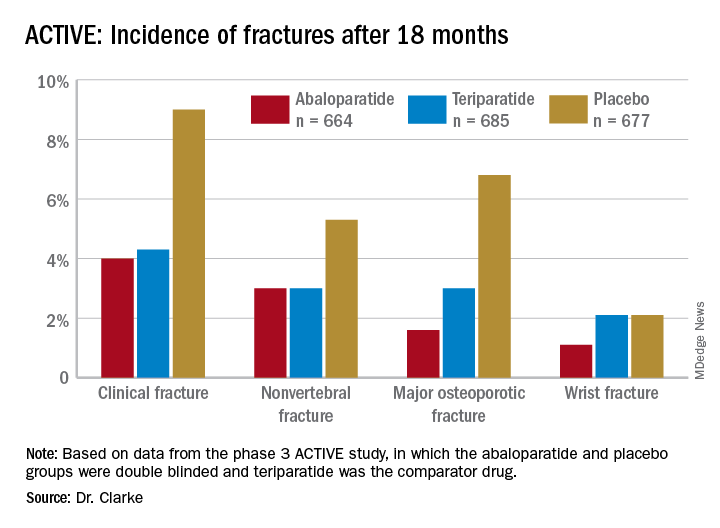

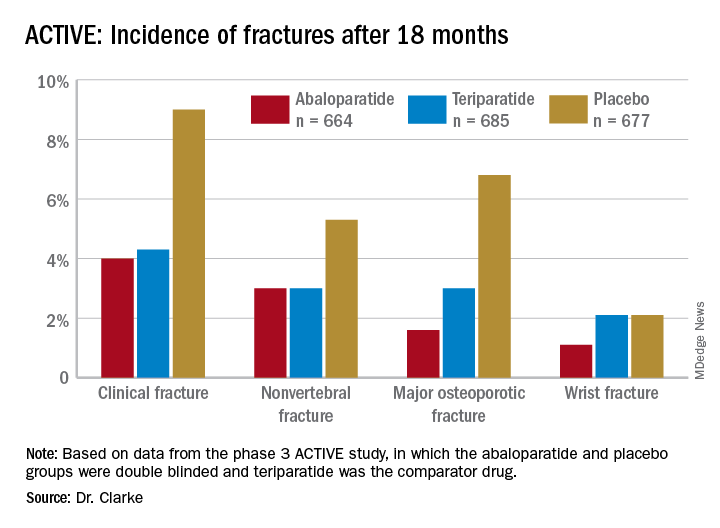

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

Postmenopausal women at high or very high risk of fracture gained significantly more bone mineral density and were significantly less likely to experience a fracture when taking abaloparatide for 18 months, according to new research presented at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

“The findings showed that abaloparatide was better than teriparatide in a number of parameters important in osteoporosis treatment, and similar in others, in high-risk and very-high-risk postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,” Bart Clarke, MD, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview. “Abaloparatide is safe and effective for use in high-risk or very-high-risk postmenopausal women,” as defined by the new American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology osteoporosis guidelines.

Ricardo R. Correa, MD, of the department of endocrinology and director of diversity for graduate medical education at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, said that the study demonstrates that abaloparatide and teriparatide have a very similar effect with abaloparatide providing a slightly better absolute risk reduction in fracture. Dr. Correa was not involved in the research.

“What will drive my decision in what to prescribe will be the cost and insurance coverage,” Dr. Correa said. “At the Veterans Administration hospital, the option that we have is abaloparatide, so this is the option that we use.”

Among women at least 65 years old who have already had one fracture, 1 in 10 will experience another fracture within the next year, and 30% will have another fracture within the next 5 years, the authors noted in their background material. Since phase 3 ACTIVE study data in 2016 showed that abaloparatide reduces fracture risk while increasing bone mineral density, compared with placebo, the researchers reanalyzed that data to assess the drug’s efficacy in patients at high or very high risk for fracture.

The study involved 2,463 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received one of three interventions: 80 mcg abaloparatide daily, placebo, or 20 mcg subcutaneous teriparatide daily. Only the abaloparatide and placebo groups were double blinded.

“Teriparatide was used as the comparator drug because teriparatide was previously approved as the first anabolic drug for osteoporosis,” Dr. Clarke said in an interview. “The hope was to show that abaloparatide was a better anabolic drug.”

Women were considered at high or very high risk of fracture if they met at least one of the following four criteria from the 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology guidelines:

- Fracture within the past 12 months or prevalent vertebral fracture.

- Very low T-score (less than –3.0) at baseline at any site.

- Multiple fractures at baseline since age 45.

- Very high fracture risk based on the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (at least 30% for major osteoporotic fracture or at least 4.5% for hip fracture).

Among the 2,026 patients who met at least one of these criteria, 664 received abaloparatide, 685 received teriparatide, and 677 received placebo. Both the abaloparatide and teriparatide significantly reduced new vertebral fracture risk, compared with placebo. In the abaloparatide group, 0.72% of women had a new vertebral fracture, compared with 0.99% in the teriparatide group and 4.77% in the placebo group (P < .0001).

Abaloparatide and teriparatide also led to significant increases in lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density, compared with placebo (P < .0001).

The study was limited by its duration of 18 months and the Food and Drug Administration’s restriction on using abaloparatide for more than 2 years because of the theoretical risk of increasing osteosarcoma, although that risk has never been demonstrated in humans, Dr. Correa said. ”We need more data with abaloparitide in more than 2 years,” he added.

In determining which medication clinicians should first prescribe to manage osteoporosis, Dr. Correa said practitioners should consider the type of osteoporosis women have, their preferences, and their labs on kidney function.

With mild to moderate osteoporosis, bisphosphonates will be the first option while denosumab will be preferred for moderate to severe osteoporosis. Teriparatide and abaloparitide are the first-line options for severe osteoporosis, he said.

“If the glomerular filtration rate is low, we cannot use bisphosphonate and we will have to limit our use to denosumab,” he said. Route and frequency of delivery plays a role in patient preferences.

“If the patient prefers an infusion once a year or a pill, then bisphosphonate,” he said, but “if the patient is fine with an injection every 6 months, then denosumab.” Patients who need and can do an injection every day can take abaloparitide or teriparatide.

Failure of previous treatments also guide clinical decisions, he added. ”If the patient has been on one medication and has a fracture or the bone mineral density decreases, then we need to switch to another medication, usually teriparatide or abaloparitide, to build new bone.”

Contraindications for abaloparatide include a high serum calcium before therapy or prior allergic reactions to components in abaloparatide, Dr. Clarke said. No new safety signals showed up in the data analysis.

The research was funded by Radius Health. Dr. Clarke is an advisory board member of Amgen, and another author consults and speaks for Amgen and is a Radius Health Advisory Board member. Two other authors are Radius Health employees who own stock in the company. Dr Correa has no disclosures.

FROM NAMS 2021

New nonhormonal therapies for hot flashes on the horizon

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

Hot flashes affect three out of four women and can last 7-10 years, but the current standard of care treatment isn’t necessarily appropriate for all women who experience vasomotor symptoms, according to Stephanie Faubion, MD, MBA, director of the Mayo Clinic Women’s Health Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

For the majority of women under age 60 who are within 10 years of menopause, hormone therapy currently remains the most effective management option for hot flashes where the benefits outweigh the risks, Dr. Faubion told attendees Sept. 25 during a plenary at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. “But really, individualizing treatment is the goal, and there are some women who are going to need some other options.”

Contraindications for hormone therapy include having a history of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, active liver disease, unexplained vaginal bleeding, high-risk endometrial cancer, transient ischemic attack, and a previous venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

“Fortunately, we have things in development,” Dr. Faubion said. She reviewed a wide range of therapies that are not currently Food and Drug Administration approved for vasomotor symptoms but are either available off label or are in clinical trials.

One of these is oxybutynin, an antimuscarinic, anticholinergic agent currently used to treat overactive bladder and overactive sweating. In a 2016 trial, 73% of women taking 15 mg extended-release oxybutynin once daily rated their symptoms as “much better,” compared with 26% who received placebo. The women experienced reduced frequency and severity of hot flashes and better sleep.

Subsequent research found a 60% reduction in hot flash frequency with 2.5 mg twice a day and a 77% reduction with 5 mg twice a day, compared with a 27% reduction with placebo. The only reported side effect that occurred more often with oxybutynin was dry mouth, but there were no significant differences in reasons for discontinuation between the treatment and placebo groups.

There are, however, some potential long-term cognitive effects from oxybutynin, Dr. Faubion said. Some research has shown an increased risk of dementia from oxybutynin and from an overall higher cumulative use of anticholinergics.

“There’s some concern about that for long-term use,” she said, but it’s effective, it’s “probably not harmful [when] used short term in women with significant, bothersome hot flashes who are unwilling or unable to use hormone therapy, and the adverse effects are tolerable for most women.” Women with bladder symptoms would be especially ideal candidates since the drug already treats those.

Dr. Faubion then discussed a new estrogen called estetrol (E4), a naturally occurring estrogen with selection action in tissues that is produced by the fetal liver and crosses the placenta. It has a long half-life of 28-32 hours, and its potential mechanism may give it a different safety profile than estradiol (E2). “There may be a lower risk of drug-drug interactions; lower breast stimulation, pain or carcinogenic impact; lower impact on triglycerides; and a neutral impact on markers of coagulation,” she said.

Though estetrol was recently approved as an oral contraceptive under the name Estelle, it’s also under investigation as a postmenopausal regimen. Preliminary findings suggest it reduces vasomotor symptom severity by 44%, compared with 30% with placebo, at 15 mg, the apparent minimum effective dose. The safety profile showed no endometrial hyperplasia and no unexpected adverse events. In those taking 15 mg of estetrol, mean endometrial thickness increased from 2 to 6 mm but returned to baseline after progestin therapy.

“The 15-mg dose also positively influenced markers of bone turnover, increased HDL [cholesterol], improved glucose tolerance,” and had no effects on coagulation parameters or triglycerides, Dr. Faubion added.

Another group of potential agents being studied for hot flashes are NK3 antagonists, which aim to exploit the recent discovery that kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy) neurons may play an important role in the etiology of vasomotor symptoms. Development of one of these, MLE 4901, was halted despite a 45% reduction in hot flashes because 3 of 28 women developed transiently elevated liver function tests, about four to six times the upper limit of normal.

Two others, fezolinetant and NT-814, are in phase 2 trials and have shown a significant reduction in symptoms, compared with placebo. The most commonly reported adverse effect in the phase 2a trial was gastrointestinal effects, but none of the participants stopped the drug because of these, and no elevated liver tests occurred. In the larger phase 2b trial, the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events included nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, urinary tract infection, sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, headache, and cough. Five women discontinued the drug because of elevated liver enzymes.

“Overall, NK3 inhibitors appear to be generally well tolerated,” Dr. Faubion said. “There does seem to be mild transaminase elevation,” though it’s not yet known if this is an effect from this class of drugs as a whole. She noted that follicle-stimulating hormone does not significantly increase, which is important because elevated FSH is associated with poor bone health, nor does estradiol significantly increase, which is clinically relevant for women at high risk of breast cancer.

“We don’t know the effects on the heart, the brain, the bone, mood, weight, or sexual health, so there’s a lot that is still not known,” Dr. Faubion said. “We still don’t know about long-term safety and efficacy with these chemical compounds,” but clinical trials of them are ongoing.

They “would be a welcome alternative to hormone therapy for those who can’t or prefer not to use a hormonal option,” Dr. Faubion said. “However, we may need broad education of clinicians to caution against widespread abandonment of hormone therapy, particularly in women with premature or early menopause.”

Donna Klassen, LCSW, the cofounder of Let’s Talk Menopause, asked whether any of these new therapies were being tested in women with breast cancer and whether anything was known about taking oxybutynin at the same time as letrozole.

“I suspect that most women with chronic diseases would have been excluded from these initial studies, but I can’t speak to that,” Dr. Faubion said, and she wasn’t aware of any data related to taking oxybutynin and letrozole concurrently.

James Simon, MD, medical director and founder of IntimMedicine and one of those who led the research on oxybutynin, responded that his trials excluded breast cancer survivors and anyone taking aromatase inhibitors.

“It will be unlikely that, in the very near future, that data will be available because all the clinical developments on these NK3s or KNDy neuron-modulating drugs exclude cancer patients,” Dr. Simon said.

However, another attendee, Lisa Larkin, MD, of Cincinnati, introduced herself as a breast cancer survivor who takes tamoxifen and said she feels “completely comfortable” prescribing oxybutynin to breast cancer survivors.

“In terms of side effects and effectiveness in patients on tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, I’ve had incredibly good luck with it, and I think it’s underutilized,” Dr. Larkin said. “The clinical pearl I would tell you is you can start really low, and the dry mouth really seems to improve with time.” She added that patients should be informed that it takes 2 weeks before it begins working, but the side effects eventually go away. “It becomes very tolerable, so I just encourage all of you to consider it as another great option.”

Dr. Faubion had no disclosures. Disclosure information was unavailable for Dr. Simon, Dr. Larkin, and Ms. Klassen.

FROM NAMS 2021

Migraine history linked to more severe hot flashes in postmenopausal women

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of migraine are more likely to experience severe or very severe hot flashes than women without migraines, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. An estimated one in five women experience migraine, and women tend to have greater migraine symptoms and disability, the authors note in their background information. Since migraines are also linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the authors sought to learn whether migraines were associated with vasomotor symptoms, another cardiovascular risk factor.

“The question in my mind is, can we do better at predicting cardiovascular risk in women because the risk prediction models that we have really don’t work all that well in women because they were designed for use in men,” Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, Penny and Bill George Director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health said in an interview. “My ultimate goal is to see if we can somehow use big data, artificial intelligence to figure out how to weight some of these female-specific or female-predominant factors to come up with a better model for cardiovascular risk prediction.”

The researchers analyzed cross-sectional data from 3,308 women who participated in the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) study through Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minn.; Scottsdale, Ariz.; and Jacksonville, Fla.. The women ranged in age from 45 to 60 years old, with an average age of 53, and the vast majority of them were white (95%) and had at least some college (93%). Most were also in a long-term relationship (85%), and a majority were employed (69%) and postmenopausal (67%).

The data, collected between May 2015 and December 2019, included a self-reported history of migraine and questionnaires that included the Menopause Rating Scale of menopause-related symptoms.

The researchers adjusted their findings to account for body mass index (BMI), menopause status, smoking status, depression, anxiety, current use of hormone therapy, and presence of low back pain within the past year. ”The diagnosis of low back pain, another pain disorder, was used to test the specificity of the association of migraine and vasomotor symptoms,” the authors write.

Just over a quarter of the women (27%) reported a history of migraine, and these women’s Menopause Rating Scale scores were an average 1.36 points greater than women without a history of migraines (P < .001). Women with self-reported migraine were also 40% more likely than women without migraines to report severe or very severe flashes versus reporting no hot flashes at all (odds ratio, 1.4; P = .02).

“The odds of reporting more severe hot flashes increased monotonically in women with a history of migraine,” the authors report. “In addition, women with low back pain had higher Menopause Rating Scale scores, but were no more likely to have severe/very severe hot flashes than those without back pain, confirming the specificity of the link between vasomotor symptoms and migraine.”

It’s not clear if migraine or hot flashes are risk factors that add to a woman’s existing cardiovascular risk profile or whether they are simply biomarkers of a shared pathway, Dr Faubion said in an interview. She speculates that the common link between migraine and vasomotor symptoms could be neurovascular dysregulation.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, of the department of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona, Phoenix, was not involved in the research but found that hypothesis plausible as well.

“Our neurologic and vascular systems are coordinated physiologic processes working together for basic brain and body function,” Dr. Smith said in an interview. Some of the symptoms of migraines and menopause are similar and both are often explained by the dysfunction of these systems. The association between history of migraines and severity of vasomotor symptoms is very likely to be explained by this dysregulation between the neurologic and vascular systems.”

Dr. Smith also pointed out, however, that the largely homogeneous study population, all from the same national clinic system, makes it difficult to know how generalizable these findings are.

The primary clinical implications of these findings are that women’s providers need to be sure they’re asking their patients about migraine history and symptoms.

“The counseling we provide on menopausal symptoms should be better tailored to our patients’ medical history, specifically inquiring about history of migraines and how this may impact their symptoms,” Dr. Smith said.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Faubion and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

FROM NAMS 2021

PCOS linked to menopausal urogenital symptoms but not hot flashes

Women with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are more likely to experience somatic and urogenital symptoms post menopause, but they were no more likely to experience severe hot flashes than were other women with similar characteristics, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are each risk factors for cardiovascular disease, so researchers wanted to find out whether they were linked to one another, which might indicate that they are markers for the same underlying mechanisms that increase heart disease risk. The lack of an association, however, raises questions about how much each of these conditions might independently increase cardiovascular risk.

“Should we take a little more time to truly risk-assess these patients not just with their ASCVD risk score, but take into account that they have PCOS and they’re going through menopause, and how severe their hot flashes are?” asked Angie S. Lobo, MD, an internal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., when she discussed her findings in an interview.

The association between PCOS and urogenital symptoms was surprising, Dr. Lobo said, but she said she suspects the reason for the finding may be the self-reported nature of the study.

“If you ask the question, you get the answer,” Dr. Lobo said. ”Are we just not asking the right questions to our patients? And should we be doing this more often? This is an exciting finding because there’s so much room to improve the clinical care of our patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from 3,308 women, ages 45-60, in a cross-sectional study from the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause, and Sexuality (DREAMS). The study occurred at Mayo Clinic locations between May 2015 and December 2019 in Rochester, Minn., in Scottsdale, Ariz., and in Jacksonville, Fla.

The women were an average 53 years old and were primarily White, educated, and postmenopausal. Among the 4.6% of women with a self-reported history of PCOS, 56% of them reported depression symptoms, compared to 42% of women without PCOS. Those with PCOS also had nearly twice the prevalence of obesity – 42% versus 22.5% among women without PCOS – and had a higher average overall score on the Menopause Rating Scale (17.7 vs. 14.7; P < .001).

Although women with PCOS initially had a greater burden of psychological symptoms on the same scale, that association disappeared after adjustment for menopause status, body mass index, depression, anxiety, and current use of hormone therapy. Even after adjustment, however, women with PCOS had higher average scores for somatic symptoms (6.7 vs. 5.6) and urogenital symptoms (5.2 vs. 4.3) than those of women without PCOS (P < .001).

Severe or very severe hot flashes were no more likely in women with a history of PCOS than in the other women in the study.

”The mechanisms underlying the correlation between PCOS and menopause symptoms in the psychological and urogenital symptom domains requires further study, although the well-known association between PCOS and mood disorders may explain the high psychological symptom burden in these women during the menopause transition,” the authors concluded.

Rachael B. Smith, DO, clinical assistant professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Arizona in Phoenix, said she was not surprised to see an association between PCOS and menopause symptoms overall, but she was surprised that PCOS did not correlate with severity of vasomotor symptoms. But Dr. Smith pointed out that the sample size of women with PCOS is fairly small (n = 151).

“Given that PCOS prevalence is about 6%-10%, I feel this association should be further studied to improve our counseling and treatment for this PCOS population,” Dr. Smith, who was not involved in the research, said in an interview. “The take-home message for physicians is improved patient-tailored counseling that takes into account patients’ prior medical history of PCOS.”

Although it will require more research to find out, Dr. Smith said she suspects that PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are additive risk factors for cardiovascular disease. She also noted that the study is limited by the homogeneity of the study population.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lobo and Dr. Smith had no disclosures.

Women with a history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are more likely to experience somatic and urogenital symptoms post menopause, but they were no more likely to experience severe hot flashes than were other women with similar characteristics, according to research presented Sept. 24 at the hybrid annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

PCOS and vasomotor symptoms are each risk factors for cardiovascular disease, so researchers wanted to find out whether they were linked to one another, which might indicate that they are markers for the same underlying mechanisms that increase heart disease risk. The lack of an association, however, raises questions about how much each of these conditions might independently increase cardiovascular risk.

“Should we take a little more time to truly risk-assess these patients not just with their ASCVD risk score, but take into account that they have PCOS and they’re going through menopause, and how severe their hot flashes are?” asked Angie S. Lobo, MD, an internal medicine specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., when she discussed her findings in an interview.

The association between PCOS and urogenital symptoms was surprising, Dr. Lobo said, but she said she suspects the reason for the finding may be the self-reported nature of the study.

“If you ask the question, you get the answer,” Dr. Lobo said. ”Are we just not asking the right questions to our patients? And should we be doing this more often? This is an exciting finding because there’s so much room to improve the clinical care of our patients.”

The researchers analyzed data from 3,308 women, ages 45-60, in a cross-sectional study from the Data Registry on the Experiences of Aging, Menopause, and Sexuality (DREAMS). The study occurred at Mayo Clinic locations between May 2015 and December 2019 in Rochester, Minn., in Scottsdale, Ariz., and in Jacksonville, Fla.

The women were an average 53 years old and were primarily White, educated, and postmenopausal. Among the 4.6% of women with a self-reported history of PCOS, 56% of them reported depression symptoms, compared to 42% of women without PCOS. Those with PCOS also had nearly twice the prevalence of obesity – 42% versus 22.5% among women without PCOS – and had a higher average overall score on the Menopause Rating Scale (17.7 vs. 14.7; P < .001).