User login

What happens when newer weight loss meds are stopped?

Some of these medicines are approved for treating obesity (Wegovy), whereas others are approved for type 2 diabetes (Ozempic and Mounjaro). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has been fast-tracked for approval for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration this year, and in the first of the series of studies looking at its effect on obesity, the SURMOUNT-1 trial, tirzepatide demonstrated a mean weight loss of around 22% in people without diabetes, spurring significant off-label use.

Our offices are full of patients who have taken these medications, with unprecedented improvements in their weight, cardiometabolic health, and quality of life. What happens when patients stop taking these medications? Or more importantly, why stop them?

Although these drugs are very effective for weight loss and treating diabetes, there can be adverse effects, primarily gastrointestinal, that limit treatment continuation. Nausea is the most common side effect and usually diminishes over time. Slow dose titration and dietary modification can minimize unwanted gastrointestinal side effects.

Drug-induced acute pancreatitis, a rare adverse event requiring patients to stop therapy, was seen in approximately 0.2% of people in clinical trials.

Medications effective but cost prohibitive?

Beyond adverse effects, patients may be forced to stop treatment because of medication cost, changes in insurance coverage, or issues with drug availability.

Two incretin therapies currently approved for treating obesity – liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy) – cost around $1,400 per month. Insurance coverage and manufacturer discounts can make treatment affordable, but anti-obesity medicines aren’t covered by Medicare or by many employer-sponsored commercial plans.

Changes in employment or insurance coverage, or expiration of manufacturer copay cards, may require patients to stop or change therapies. The increased prescribing and overall expense of these drugs have prompted insurance plans and self-insured groups to consider whether providing coverage for these medications is sustainable.

Limited coverage has led to significant off-label prescribing of incretin therapies that aren’t approved for treating obesity (for instance, Ozempic and Mounjaro) and compounding pharmacies selling peptides that allegedly contain the active pharmaceutical ingredients. High demand for these medications has created significant supply shortages over the past year, causing many people to be without treatment for significant periods of time, as reported by this news organization.

Recently, I saw a patient who lost more than 30 pounds with semaglutide (Wegovy). She then changed employers and the medication was no longer covered. She gained back almost 10 pounds over 3 months and was prescribed tirzepatide (Mounjaro) off-label for weight loss by another provider, using a manufacturer discount card to make the medication affordable. The patient did well with the new regimen and lost about 20 pounds, but the pharmacy stopped filling the prescription when changes were made to the discount card. Afraid of regaining the weight, she came to see us as a new patient to discuss her options with her lack of coverage for anti-obesity medications.

Stopping equals weight regain

Obesity is a chronic disease like hypertension. It responds to treatment and when people stop taking these anti-obesity medications, this is generally associated with increased appetite and less satiety, and there is subsequent weight regain and a recurrence in excess weight-related complications.

The STEP-1 trial extension showed an initial mean body weight reduction of 17.3% with weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg over 1 year. On average, two-thirds of the weight lost was regained by participants within 1 year of stopping semaglutide and the study’s lifestyle intervention. Many of the improvements seen in cardiometabolic variables, like blood glucose and blood pressure, similarly reverted to baseline.

There are also 2-year data from the STEP-5 trial with semaglutide; 3-year data from the SCALE trial with liraglutide; and 5-year nonrandomized data with multiple agents that show durable, clinically significant weight loss from medical therapies for obesity.

These data together demonstrate that medications are effective for durable weight loss if they are continued. However, this is not how obesity is currently treated. Anti-obesity medications are prescribed to less than 3% of eligible people in the United States, and the average duration of therapy is less than 90 days. This treatment length isn’t sufficient to see the full benefits most medications offer and certainly doesn’t support long-term weight maintenance.

A recent study showed that, in addition to maintaining weight loss from medical therapies, incretin-containing anti-obesity medication regimens were effective for treating weight regain and facilitating healthier weight after bariatric surgery.

Chronic therapy is needed for weight maintenance because several neurohormonal changes occur owing to weight loss. Metabolic adaptation is the relative reduction in energy expenditure, below what would be expected, in people after weight loss. When this is combined with physiologic changes that increase appetite and decrease satiety, many people create a positive energy balance that results in weight regain. This has been observed in reality TV shows such as “The Biggest Loser”: It’s biology, not willpower.

Unfortunately, many people – including health care providers – don’t understand how these changes promote weight regain and patients are too often blamed when their weight goes back up after medications are stopped. This blame is greatly misinformed by weight-biased beliefs that people with obesity are lazy and lack self-control for weight loss or maintenance. Nobody would be surprised if someone’s blood pressure went up if their antihypertensive medications were stopped. Why do we think so differently when treating obesity?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States is over 40% and growing. We are fortunate to have new medications that on average lead to 15% or greater weight loss when combined with lifestyle modification.

However, these medications are expensive and the limited insurance coverage currently available may not improve. From a patient experience perspective, it’s distressing to have to discontinue treatments that have helped to achieve a healthier weight and then experience regain.

People need better access to evidence-based treatments for obesity, which include lifestyle interventions, anti-obesity medications, and bariatric procedures. Successful treatment of obesity should include a personalized, patient-centered approach that may require a combination of therapies, such as medications and surgery, for lasting weight control.

Dr. Almandoz is associate professor, department of internal medicine, division of endocrinology; medical director, weight wellness program, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas. He disclosed ties with Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Follow Dr. Almandoz on Twitter: @JaimeAlmandoz.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some of these medicines are approved for treating obesity (Wegovy), whereas others are approved for type 2 diabetes (Ozempic and Mounjaro). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has been fast-tracked for approval for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration this year, and in the first of the series of studies looking at its effect on obesity, the SURMOUNT-1 trial, tirzepatide demonstrated a mean weight loss of around 22% in people without diabetes, spurring significant off-label use.

Our offices are full of patients who have taken these medications, with unprecedented improvements in their weight, cardiometabolic health, and quality of life. What happens when patients stop taking these medications? Or more importantly, why stop them?

Although these drugs are very effective for weight loss and treating diabetes, there can be adverse effects, primarily gastrointestinal, that limit treatment continuation. Nausea is the most common side effect and usually diminishes over time. Slow dose titration and dietary modification can minimize unwanted gastrointestinal side effects.

Drug-induced acute pancreatitis, a rare adverse event requiring patients to stop therapy, was seen in approximately 0.2% of people in clinical trials.

Medications effective but cost prohibitive?

Beyond adverse effects, patients may be forced to stop treatment because of medication cost, changes in insurance coverage, or issues with drug availability.

Two incretin therapies currently approved for treating obesity – liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy) – cost around $1,400 per month. Insurance coverage and manufacturer discounts can make treatment affordable, but anti-obesity medicines aren’t covered by Medicare or by many employer-sponsored commercial plans.

Changes in employment or insurance coverage, or expiration of manufacturer copay cards, may require patients to stop or change therapies. The increased prescribing and overall expense of these drugs have prompted insurance plans and self-insured groups to consider whether providing coverage for these medications is sustainable.

Limited coverage has led to significant off-label prescribing of incretin therapies that aren’t approved for treating obesity (for instance, Ozempic and Mounjaro) and compounding pharmacies selling peptides that allegedly contain the active pharmaceutical ingredients. High demand for these medications has created significant supply shortages over the past year, causing many people to be without treatment for significant periods of time, as reported by this news organization.

Recently, I saw a patient who lost more than 30 pounds with semaglutide (Wegovy). She then changed employers and the medication was no longer covered. She gained back almost 10 pounds over 3 months and was prescribed tirzepatide (Mounjaro) off-label for weight loss by another provider, using a manufacturer discount card to make the medication affordable. The patient did well with the new regimen and lost about 20 pounds, but the pharmacy stopped filling the prescription when changes were made to the discount card. Afraid of regaining the weight, she came to see us as a new patient to discuss her options with her lack of coverage for anti-obesity medications.

Stopping equals weight regain

Obesity is a chronic disease like hypertension. It responds to treatment and when people stop taking these anti-obesity medications, this is generally associated with increased appetite and less satiety, and there is subsequent weight regain and a recurrence in excess weight-related complications.

The STEP-1 trial extension showed an initial mean body weight reduction of 17.3% with weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg over 1 year. On average, two-thirds of the weight lost was regained by participants within 1 year of stopping semaglutide and the study’s lifestyle intervention. Many of the improvements seen in cardiometabolic variables, like blood glucose and blood pressure, similarly reverted to baseline.

There are also 2-year data from the STEP-5 trial with semaglutide; 3-year data from the SCALE trial with liraglutide; and 5-year nonrandomized data with multiple agents that show durable, clinically significant weight loss from medical therapies for obesity.

These data together demonstrate that medications are effective for durable weight loss if they are continued. However, this is not how obesity is currently treated. Anti-obesity medications are prescribed to less than 3% of eligible people in the United States, and the average duration of therapy is less than 90 days. This treatment length isn’t sufficient to see the full benefits most medications offer and certainly doesn’t support long-term weight maintenance.

A recent study showed that, in addition to maintaining weight loss from medical therapies, incretin-containing anti-obesity medication regimens were effective for treating weight regain and facilitating healthier weight after bariatric surgery.

Chronic therapy is needed for weight maintenance because several neurohormonal changes occur owing to weight loss. Metabolic adaptation is the relative reduction in energy expenditure, below what would be expected, in people after weight loss. When this is combined with physiologic changes that increase appetite and decrease satiety, many people create a positive energy balance that results in weight regain. This has been observed in reality TV shows such as “The Biggest Loser”: It’s biology, not willpower.

Unfortunately, many people – including health care providers – don’t understand how these changes promote weight regain and patients are too often blamed when their weight goes back up after medications are stopped. This blame is greatly misinformed by weight-biased beliefs that people with obesity are lazy and lack self-control for weight loss or maintenance. Nobody would be surprised if someone’s blood pressure went up if their antihypertensive medications were stopped. Why do we think so differently when treating obesity?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States is over 40% and growing. We are fortunate to have new medications that on average lead to 15% or greater weight loss when combined with lifestyle modification.

However, these medications are expensive and the limited insurance coverage currently available may not improve. From a patient experience perspective, it’s distressing to have to discontinue treatments that have helped to achieve a healthier weight and then experience regain.

People need better access to evidence-based treatments for obesity, which include lifestyle interventions, anti-obesity medications, and bariatric procedures. Successful treatment of obesity should include a personalized, patient-centered approach that may require a combination of therapies, such as medications and surgery, for lasting weight control.

Dr. Almandoz is associate professor, department of internal medicine, division of endocrinology; medical director, weight wellness program, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas. He disclosed ties with Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Follow Dr. Almandoz on Twitter: @JaimeAlmandoz.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Some of these medicines are approved for treating obesity (Wegovy), whereas others are approved for type 2 diabetes (Ozempic and Mounjaro). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has been fast-tracked for approval for weight loss by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration this year, and in the first of the series of studies looking at its effect on obesity, the SURMOUNT-1 trial, tirzepatide demonstrated a mean weight loss of around 22% in people without diabetes, spurring significant off-label use.

Our offices are full of patients who have taken these medications, with unprecedented improvements in their weight, cardiometabolic health, and quality of life. What happens when patients stop taking these medications? Or more importantly, why stop them?

Although these drugs are very effective for weight loss and treating diabetes, there can be adverse effects, primarily gastrointestinal, that limit treatment continuation. Nausea is the most common side effect and usually diminishes over time. Slow dose titration and dietary modification can minimize unwanted gastrointestinal side effects.

Drug-induced acute pancreatitis, a rare adverse event requiring patients to stop therapy, was seen in approximately 0.2% of people in clinical trials.

Medications effective but cost prohibitive?

Beyond adverse effects, patients may be forced to stop treatment because of medication cost, changes in insurance coverage, or issues with drug availability.

Two incretin therapies currently approved for treating obesity – liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy) – cost around $1,400 per month. Insurance coverage and manufacturer discounts can make treatment affordable, but anti-obesity medicines aren’t covered by Medicare or by many employer-sponsored commercial plans.

Changes in employment or insurance coverage, or expiration of manufacturer copay cards, may require patients to stop or change therapies. The increased prescribing and overall expense of these drugs have prompted insurance plans and self-insured groups to consider whether providing coverage for these medications is sustainable.

Limited coverage has led to significant off-label prescribing of incretin therapies that aren’t approved for treating obesity (for instance, Ozempic and Mounjaro) and compounding pharmacies selling peptides that allegedly contain the active pharmaceutical ingredients. High demand for these medications has created significant supply shortages over the past year, causing many people to be without treatment for significant periods of time, as reported by this news organization.

Recently, I saw a patient who lost more than 30 pounds with semaglutide (Wegovy). She then changed employers and the medication was no longer covered. She gained back almost 10 pounds over 3 months and was prescribed tirzepatide (Mounjaro) off-label for weight loss by another provider, using a manufacturer discount card to make the medication affordable. The patient did well with the new regimen and lost about 20 pounds, but the pharmacy stopped filling the prescription when changes were made to the discount card. Afraid of regaining the weight, she came to see us as a new patient to discuss her options with her lack of coverage for anti-obesity medications.

Stopping equals weight regain

Obesity is a chronic disease like hypertension. It responds to treatment and when people stop taking these anti-obesity medications, this is generally associated with increased appetite and less satiety, and there is subsequent weight regain and a recurrence in excess weight-related complications.

The STEP-1 trial extension showed an initial mean body weight reduction of 17.3% with weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg over 1 year. On average, two-thirds of the weight lost was regained by participants within 1 year of stopping semaglutide and the study’s lifestyle intervention. Many of the improvements seen in cardiometabolic variables, like blood glucose and blood pressure, similarly reverted to baseline.

There are also 2-year data from the STEP-5 trial with semaglutide; 3-year data from the SCALE trial with liraglutide; and 5-year nonrandomized data with multiple agents that show durable, clinically significant weight loss from medical therapies for obesity.

These data together demonstrate that medications are effective for durable weight loss if they are continued. However, this is not how obesity is currently treated. Anti-obesity medications are prescribed to less than 3% of eligible people in the United States, and the average duration of therapy is less than 90 days. This treatment length isn’t sufficient to see the full benefits most medications offer and certainly doesn’t support long-term weight maintenance.

A recent study showed that, in addition to maintaining weight loss from medical therapies, incretin-containing anti-obesity medication regimens were effective for treating weight regain and facilitating healthier weight after bariatric surgery.

Chronic therapy is needed for weight maintenance because several neurohormonal changes occur owing to weight loss. Metabolic adaptation is the relative reduction in energy expenditure, below what would be expected, in people after weight loss. When this is combined with physiologic changes that increase appetite and decrease satiety, many people create a positive energy balance that results in weight regain. This has been observed in reality TV shows such as “The Biggest Loser”: It’s biology, not willpower.

Unfortunately, many people – including health care providers – don’t understand how these changes promote weight regain and patients are too often blamed when their weight goes back up after medications are stopped. This blame is greatly misinformed by weight-biased beliefs that people with obesity are lazy and lack self-control for weight loss or maintenance. Nobody would be surprised if someone’s blood pressure went up if their antihypertensive medications were stopped. Why do we think so differently when treating obesity?

The prevalence of obesity in the United States is over 40% and growing. We are fortunate to have new medications that on average lead to 15% or greater weight loss when combined with lifestyle modification.

However, these medications are expensive and the limited insurance coverage currently available may not improve. From a patient experience perspective, it’s distressing to have to discontinue treatments that have helped to achieve a healthier weight and then experience regain.

People need better access to evidence-based treatments for obesity, which include lifestyle interventions, anti-obesity medications, and bariatric procedures. Successful treatment of obesity should include a personalized, patient-centered approach that may require a combination of therapies, such as medications and surgery, for lasting weight control.

Dr. Almandoz is associate professor, department of internal medicine, division of endocrinology; medical director, weight wellness program, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas. He disclosed ties with Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Follow Dr. Almandoz on Twitter: @JaimeAlmandoz.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The desk

Recently, Dr. Jeffrey Benabio (I don’t believe we’ve ever met), wrote an enjoyable commentary mourning the loss of letters – the wonderful paper-and-pen documents that were, for the vast majority of human history, the main method of long distance communication. Even today, he notes, there’s something special about a letter, with the time and human effort required to sit down and put pen to paper, seal it into an envelope, and entrust it to the post office.

In his piece, Dr. Benabio describes his work desk as “a small surface, perhaps just enough for the monitor and a mug ... it has no drawers. It is lean and immaculate, but it has no soul.”

With all due respect, I can’t do that. I need a desk to function. A REAL one.

I was 9 when I got my first desk, far more than a 4th-grader needed. My dad was an attorney and had an extra desk from a partner who’d retired. It was big and heavy and made of wood. It had three drawers on each side, one in the middle, and pull-outs on each side in case you needed even more writing space. I loved it. As the years went by I did homework, wrote short stories, and built models on it. I covered the pull-outs with stickers for starship controls, so on a whim I could jump to hyperspace. In 1984 a brand-new Apple Macintosh, with 128K of RAM showed up on it. I began using the computer to write college papers, but most of my work at the desk still involved books and handwriting.

My current home desk has been with me through college, medical school, residency, and fellowship, and it continues with me today.

At my office, though, is my main desk. Before 2013 I was in a small back office, with only room for a tiny three-drawer college desk.

But in 2013 I moved into my own office, for the first time in my career. Now it was time to bring in my real desk, waiting in storage since my Dad had retired.

This is my desk now. It’s huge. It’s heavy. My dad bought it when he started his law practice in 1968. It has eight drawers, and my Dad’s original leather blotter is on top. It came with his chrome and brass letter opener in the top drawer. It has space for my computer, writing pads, exam tools (for people who can’t get on the exam table across the hall), business cards, a few baubles from my kids, stapler, tape dispenser, pen cup, phone, coffee mug, and a million other things.

It takes up a lot of space, but I don’t mind. There’s a human comfort to it and the organized disorder on top of it.

Everyone practices medicine differently. What works for me isn’t going to work for another doctor, and definitely not for another specialty.

But here, the big desk is part of my personal style. Sitting there gets me into “doctor mode” each day. I hope the more casual surroundings make it comfortable for patients, too.

It’s part of the soul of my practice, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, Dr. Jeffrey Benabio (I don’t believe we’ve ever met), wrote an enjoyable commentary mourning the loss of letters – the wonderful paper-and-pen documents that were, for the vast majority of human history, the main method of long distance communication. Even today, he notes, there’s something special about a letter, with the time and human effort required to sit down and put pen to paper, seal it into an envelope, and entrust it to the post office.

In his piece, Dr. Benabio describes his work desk as “a small surface, perhaps just enough for the monitor and a mug ... it has no drawers. It is lean and immaculate, but it has no soul.”

With all due respect, I can’t do that. I need a desk to function. A REAL one.

I was 9 when I got my first desk, far more than a 4th-grader needed. My dad was an attorney and had an extra desk from a partner who’d retired. It was big and heavy and made of wood. It had three drawers on each side, one in the middle, and pull-outs on each side in case you needed even more writing space. I loved it. As the years went by I did homework, wrote short stories, and built models on it. I covered the pull-outs with stickers for starship controls, so on a whim I could jump to hyperspace. In 1984 a brand-new Apple Macintosh, with 128K of RAM showed up on it. I began using the computer to write college papers, but most of my work at the desk still involved books and handwriting.

My current home desk has been with me through college, medical school, residency, and fellowship, and it continues with me today.

At my office, though, is my main desk. Before 2013 I was in a small back office, with only room for a tiny three-drawer college desk.

But in 2013 I moved into my own office, for the first time in my career. Now it was time to bring in my real desk, waiting in storage since my Dad had retired.

This is my desk now. It’s huge. It’s heavy. My dad bought it when he started his law practice in 1968. It has eight drawers, and my Dad’s original leather blotter is on top. It came with his chrome and brass letter opener in the top drawer. It has space for my computer, writing pads, exam tools (for people who can’t get on the exam table across the hall), business cards, a few baubles from my kids, stapler, tape dispenser, pen cup, phone, coffee mug, and a million other things.

It takes up a lot of space, but I don’t mind. There’s a human comfort to it and the organized disorder on top of it.

Everyone practices medicine differently. What works for me isn’t going to work for another doctor, and definitely not for another specialty.

But here, the big desk is part of my personal style. Sitting there gets me into “doctor mode” each day. I hope the more casual surroundings make it comfortable for patients, too.

It’s part of the soul of my practice, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, Dr. Jeffrey Benabio (I don’t believe we’ve ever met), wrote an enjoyable commentary mourning the loss of letters – the wonderful paper-and-pen documents that were, for the vast majority of human history, the main method of long distance communication. Even today, he notes, there’s something special about a letter, with the time and human effort required to sit down and put pen to paper, seal it into an envelope, and entrust it to the post office.

In his piece, Dr. Benabio describes his work desk as “a small surface, perhaps just enough for the monitor and a mug ... it has no drawers. It is lean and immaculate, but it has no soul.”

With all due respect, I can’t do that. I need a desk to function. A REAL one.

I was 9 when I got my first desk, far more than a 4th-grader needed. My dad was an attorney and had an extra desk from a partner who’d retired. It was big and heavy and made of wood. It had three drawers on each side, one in the middle, and pull-outs on each side in case you needed even more writing space. I loved it. As the years went by I did homework, wrote short stories, and built models on it. I covered the pull-outs with stickers for starship controls, so on a whim I could jump to hyperspace. In 1984 a brand-new Apple Macintosh, with 128K of RAM showed up on it. I began using the computer to write college papers, but most of my work at the desk still involved books and handwriting.

My current home desk has been with me through college, medical school, residency, and fellowship, and it continues with me today.

At my office, though, is my main desk. Before 2013 I was in a small back office, with only room for a tiny three-drawer college desk.

But in 2013 I moved into my own office, for the first time in my career. Now it was time to bring in my real desk, waiting in storage since my Dad had retired.

This is my desk now. It’s huge. It’s heavy. My dad bought it when he started his law practice in 1968. It has eight drawers, and my Dad’s original leather blotter is on top. It came with his chrome and brass letter opener in the top drawer. It has space for my computer, writing pads, exam tools (for people who can’t get on the exam table across the hall), business cards, a few baubles from my kids, stapler, tape dispenser, pen cup, phone, coffee mug, and a million other things.

It takes up a lot of space, but I don’t mind. There’s a human comfort to it and the organized disorder on top of it.

Everyone practices medicine differently. What works for me isn’t going to work for another doctor, and definitely not for another specialty.

But here, the big desk is part of my personal style. Sitting there gets me into “doctor mode” each day. I hope the more casual surroundings make it comfortable for patients, too.

It’s part of the soul of my practice, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Hydroxyurea underused in youth with sickle cell anemia

Even after endorsement in updated guidelines, hydroxyurea is substantially underused in youth with sickle cell anemia (SCA), new research indicates.

SCA can lead to pain crises, stroke, and early death. Hydroxyurea, an oral disease-modifying medication, can reduce the complications.

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute published revised guidelines that hydroxyurea should be offered as the primary therapy to all patients who were at least 9 months old and living with SCA, regardless of disease severity.

Low uptake even after guideline revision

Yet, a research team led by Sarah L. Reeves, PhD, MPH, with the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, found in their study of use in two sample states – Michigan and New York – that hydroxyurea use was low in children and adolescents enrolled in Medicaid and increased only slightly in Michigan and not at all in New York after the guideline revision.

After the guidelines were updated, the researchers observed that, on average, children and adolescents were getting the medication less than a third of the days in a year (32% maximum in the year with the highest uptake). The data were gathered from a study population that included 4,302 youths aged 1-17 years with SCA.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘A national issue’

Russell Ware, MD, PhD, chair of hematology translational research at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was not part of the research, says that though data were gathered from Michigan and New York, “this is a national issue.”

Dr. Ware says the main problem is the way the health system describes the importance of hydroxyurea.

“There needs to be a realization that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for children with sickle cell anemia. It’s not just something they should take when they’re sick,” Dr. Ware said.

He added, “If you have diabetes, should you only take insulin if you’re really sick and hospitalized with a diabetic coma? Of course not.”

He said often providers aren’t giving a clear and consistent message to families.

“They’re not all sure they want to recommend it. They might offer it,” Dr. Ware said, which jeopardizes uptake. “Providers need to be more committed to it. They need to know how to dose it.”

Bad rap from past indications

Dr. Ware says hydroxyurea also gets a bad rap from use decades ago as a chemotherapeutic agent for cancer and then as an anti-HIV medication.

Now it’s used in a completely different way with SCA, but the fear of the association lingers.

“This label as a chemotherapeutic agent has really dogged hydroxyurea,” he said. “It’s a completely different mechanism. It’s a different dose. It’s a different purpose.”

The message to families should be more direct, he says: “Your child has sickle cell anemia and needs to be on disease-modifying therapy because this is a life-threatening disease.”

The underuse of this drug is particularly ironic, he says, as each capsule, taken daily, “costs about fifty cents.”

Medicaid support critical

Authors conclude that multifaceted interventions may be necessary to increase the number of filled prescriptions and use. They also point out that the interventions rely on states’ Medicaid support regarding hydroxyurea use. From 70% to 90% of young people with SCA are covered by Medicaid at some point, the researchers write.

“Variation may exist across states, as well as within states, in the coverage of hydroxyurea, outpatient visits, and associated lab monitoring,” they note.

The authors point to interventions in clinical trials that have had some success in hydroxyurea use.

Creary et al., for example, found that electronic directly observed therapy was associated with high adherence. That involved sending daily texts to patients to take hydroxyurea and patients recording and sending daily videos that show they took the medication.

The authors add that incorporating clinical pharmacists into the care team to provide education and support for families has been shown to be associated with successful outcomes for other chronic conditions – this approach may be particularly well suited to hydroxyurea given that this medication requires significant dosage monitoring.

Dr. Ware, however, says that solutions should focus on the health system more clearly communicating that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for all kids with SCA.

“We need to dispel these myths and these labels that are unfairly attributed to it. Then we’d probably do a lot better,” he said.

He added that children with SCA, “are a marginalized, neglected population of patients historically,” and addressing social determinants of health is also important in getting better uptake.

“Our pharmacy, for example, ships the drug to the families if they’re just getting a refill rather than making them drive all the way in,” Dr. Ware says.

Dr. Ware said given the interruption in doctor/patient relationships in the pandemic, the poor uptake of hydroxyurea could be even worse now.

The work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Coauthor Dr. Green was the principal investigator of an NIH-funded trial of hydroxyurea in Uganda with a study drug provided by Siklos. No other author disclosures were reported. In addition to receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Ware receives research donations from Bristol Myers Squibb, Addmedica, and Hemex Health. He is a medical adviser for Nova Laboratories and Octapharma, and serves on Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Novartis and Editas.

Even after endorsement in updated guidelines, hydroxyurea is substantially underused in youth with sickle cell anemia (SCA), new research indicates.

SCA can lead to pain crises, stroke, and early death. Hydroxyurea, an oral disease-modifying medication, can reduce the complications.

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute published revised guidelines that hydroxyurea should be offered as the primary therapy to all patients who were at least 9 months old and living with SCA, regardless of disease severity.

Low uptake even after guideline revision

Yet, a research team led by Sarah L. Reeves, PhD, MPH, with the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, found in their study of use in two sample states – Michigan and New York – that hydroxyurea use was low in children and adolescents enrolled in Medicaid and increased only slightly in Michigan and not at all in New York after the guideline revision.

After the guidelines were updated, the researchers observed that, on average, children and adolescents were getting the medication less than a third of the days in a year (32% maximum in the year with the highest uptake). The data were gathered from a study population that included 4,302 youths aged 1-17 years with SCA.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘A national issue’

Russell Ware, MD, PhD, chair of hematology translational research at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was not part of the research, says that though data were gathered from Michigan and New York, “this is a national issue.”

Dr. Ware says the main problem is the way the health system describes the importance of hydroxyurea.

“There needs to be a realization that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for children with sickle cell anemia. It’s not just something they should take when they’re sick,” Dr. Ware said.

He added, “If you have diabetes, should you only take insulin if you’re really sick and hospitalized with a diabetic coma? Of course not.”

He said often providers aren’t giving a clear and consistent message to families.

“They’re not all sure they want to recommend it. They might offer it,” Dr. Ware said, which jeopardizes uptake. “Providers need to be more committed to it. They need to know how to dose it.”

Bad rap from past indications

Dr. Ware says hydroxyurea also gets a bad rap from use decades ago as a chemotherapeutic agent for cancer and then as an anti-HIV medication.

Now it’s used in a completely different way with SCA, but the fear of the association lingers.

“This label as a chemotherapeutic agent has really dogged hydroxyurea,” he said. “It’s a completely different mechanism. It’s a different dose. It’s a different purpose.”

The message to families should be more direct, he says: “Your child has sickle cell anemia and needs to be on disease-modifying therapy because this is a life-threatening disease.”

The underuse of this drug is particularly ironic, he says, as each capsule, taken daily, “costs about fifty cents.”

Medicaid support critical

Authors conclude that multifaceted interventions may be necessary to increase the number of filled prescriptions and use. They also point out that the interventions rely on states’ Medicaid support regarding hydroxyurea use. From 70% to 90% of young people with SCA are covered by Medicaid at some point, the researchers write.

“Variation may exist across states, as well as within states, in the coverage of hydroxyurea, outpatient visits, and associated lab monitoring,” they note.

The authors point to interventions in clinical trials that have had some success in hydroxyurea use.

Creary et al., for example, found that electronic directly observed therapy was associated with high adherence. That involved sending daily texts to patients to take hydroxyurea and patients recording and sending daily videos that show they took the medication.

The authors add that incorporating clinical pharmacists into the care team to provide education and support for families has been shown to be associated with successful outcomes for other chronic conditions – this approach may be particularly well suited to hydroxyurea given that this medication requires significant dosage monitoring.

Dr. Ware, however, says that solutions should focus on the health system more clearly communicating that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for all kids with SCA.

“We need to dispel these myths and these labels that are unfairly attributed to it. Then we’d probably do a lot better,” he said.

He added that children with SCA, “are a marginalized, neglected population of patients historically,” and addressing social determinants of health is also important in getting better uptake.

“Our pharmacy, for example, ships the drug to the families if they’re just getting a refill rather than making them drive all the way in,” Dr. Ware says.

Dr. Ware said given the interruption in doctor/patient relationships in the pandemic, the poor uptake of hydroxyurea could be even worse now.

The work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Coauthor Dr. Green was the principal investigator of an NIH-funded trial of hydroxyurea in Uganda with a study drug provided by Siklos. No other author disclosures were reported. In addition to receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Ware receives research donations from Bristol Myers Squibb, Addmedica, and Hemex Health. He is a medical adviser for Nova Laboratories and Octapharma, and serves on Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Novartis and Editas.

Even after endorsement in updated guidelines, hydroxyurea is substantially underused in youth with sickle cell anemia (SCA), new research indicates.

SCA can lead to pain crises, stroke, and early death. Hydroxyurea, an oral disease-modifying medication, can reduce the complications.

In 2014, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute published revised guidelines that hydroxyurea should be offered as the primary therapy to all patients who were at least 9 months old and living with SCA, regardless of disease severity.

Low uptake even after guideline revision

Yet, a research team led by Sarah L. Reeves, PhD, MPH, with the Child Health Evaluation and Research Center at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, found in their study of use in two sample states – Michigan and New York – that hydroxyurea use was low in children and adolescents enrolled in Medicaid and increased only slightly in Michigan and not at all in New York after the guideline revision.

After the guidelines were updated, the researchers observed that, on average, children and adolescents were getting the medication less than a third of the days in a year (32% maximum in the year with the highest uptake). The data were gathered from a study population that included 4,302 youths aged 1-17 years with SCA.

Findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

‘A national issue’

Russell Ware, MD, PhD, chair of hematology translational research at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was not part of the research, says that though data were gathered from Michigan and New York, “this is a national issue.”

Dr. Ware says the main problem is the way the health system describes the importance of hydroxyurea.

“There needs to be a realization that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for children with sickle cell anemia. It’s not just something they should take when they’re sick,” Dr. Ware said.

He added, “If you have diabetes, should you only take insulin if you’re really sick and hospitalized with a diabetic coma? Of course not.”

He said often providers aren’t giving a clear and consistent message to families.

“They’re not all sure they want to recommend it. They might offer it,” Dr. Ware said, which jeopardizes uptake. “Providers need to be more committed to it. They need to know how to dose it.”

Bad rap from past indications

Dr. Ware says hydroxyurea also gets a bad rap from use decades ago as a chemotherapeutic agent for cancer and then as an anti-HIV medication.

Now it’s used in a completely different way with SCA, but the fear of the association lingers.

“This label as a chemotherapeutic agent has really dogged hydroxyurea,” he said. “It’s a completely different mechanism. It’s a different dose. It’s a different purpose.”

The message to families should be more direct, he says: “Your child has sickle cell anemia and needs to be on disease-modifying therapy because this is a life-threatening disease.”

The underuse of this drug is particularly ironic, he says, as each capsule, taken daily, “costs about fifty cents.”

Medicaid support critical

Authors conclude that multifaceted interventions may be necessary to increase the number of filled prescriptions and use. They also point out that the interventions rely on states’ Medicaid support regarding hydroxyurea use. From 70% to 90% of young people with SCA are covered by Medicaid at some point, the researchers write.

“Variation may exist across states, as well as within states, in the coverage of hydroxyurea, outpatient visits, and associated lab monitoring,” they note.

The authors point to interventions in clinical trials that have had some success in hydroxyurea use.

Creary et al., for example, found that electronic directly observed therapy was associated with high adherence. That involved sending daily texts to patients to take hydroxyurea and patients recording and sending daily videos that show they took the medication.

The authors add that incorporating clinical pharmacists into the care team to provide education and support for families has been shown to be associated with successful outcomes for other chronic conditions – this approach may be particularly well suited to hydroxyurea given that this medication requires significant dosage monitoring.

Dr. Ware, however, says that solutions should focus on the health system more clearly communicating that hydroxyurea is the standard of care for all kids with SCA.

“We need to dispel these myths and these labels that are unfairly attributed to it. Then we’d probably do a lot better,” he said.

He added that children with SCA, “are a marginalized, neglected population of patients historically,” and addressing social determinants of health is also important in getting better uptake.

“Our pharmacy, for example, ships the drug to the families if they’re just getting a refill rather than making them drive all the way in,” Dr. Ware says.

Dr. Ware said given the interruption in doctor/patient relationships in the pandemic, the poor uptake of hydroxyurea could be even worse now.

The work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Coauthor Dr. Green was the principal investigator of an NIH-funded trial of hydroxyurea in Uganda with a study drug provided by Siklos. No other author disclosures were reported. In addition to receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Ware receives research donations from Bristol Myers Squibb, Addmedica, and Hemex Health. He is a medical adviser for Nova Laboratories and Octapharma, and serves on Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Novartis and Editas.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Celebrity death finally solved – with locks of hair

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to open this week with a case.

A 56-year-old musician presents with diffuse abdominal pain, cramping, and jaundice. His medical history is notable for years of diffuse abdominal complaints, characterized by disabling bouts of diarrhea.

In addition to the jaundice, this acute illness was accompanied by fever as well as diffuse edema and ascites. The patient underwent several abdominal paracenteses to drain excess fluid. One consulting physician administered alcohol to relieve pain, to little avail.

The patient succumbed to his illness. An autopsy showed diffuse liver injury, as well as papillary necrosis of the kidneys. Notably, the nerves of his auditory canal were noted to be thickened, along with the bony part of the skull, consistent with Paget disease of the bone and explaining, potentially, why the talented musician had gone deaf at such a young age.

An interesting note on social history: The patient had apparently developed some feelings for the niece of that doctor who prescribed alcohol. Her name was Therese, perhaps mistranscribed as Elise, and it seems that he may have written this song for her.

We’re talking about this paper in Current Biology, by Tristan Begg and colleagues, which gives us a look into the very genome of what some would argue is the world’s greatest composer.

The ability to extract DNA from older specimens has transformed the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and history, and now, perhaps, musicology as well.

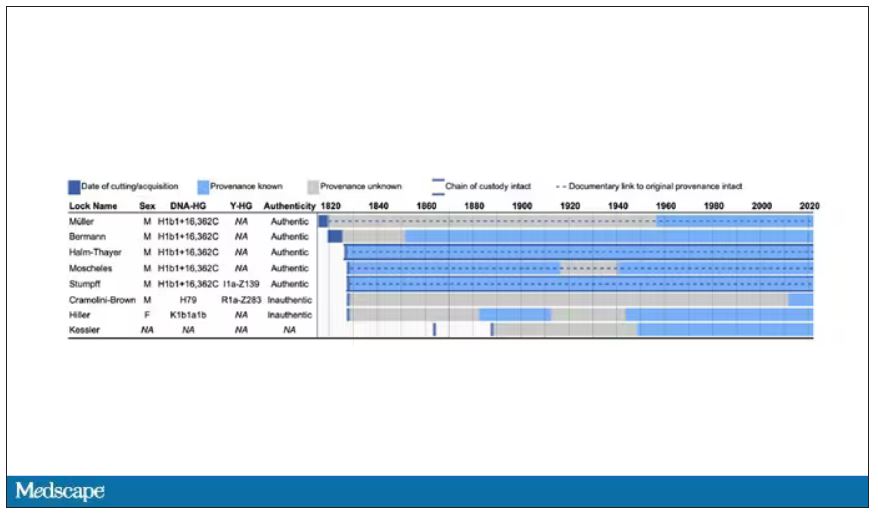

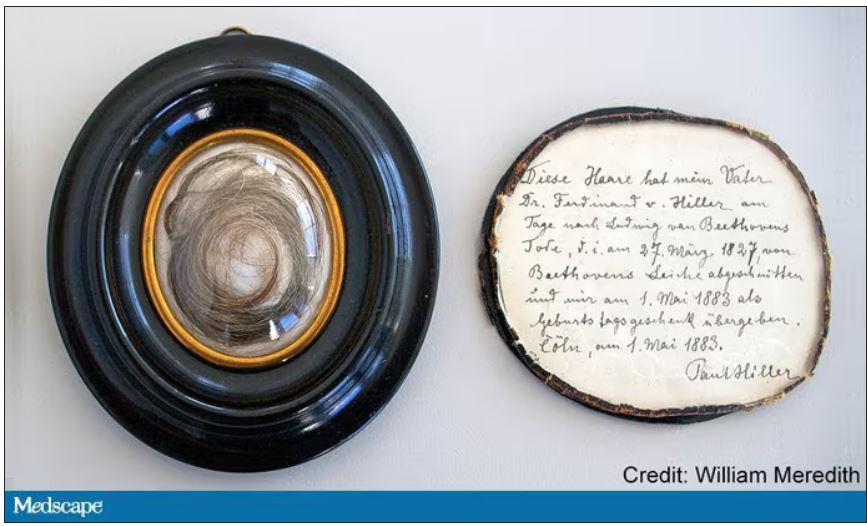

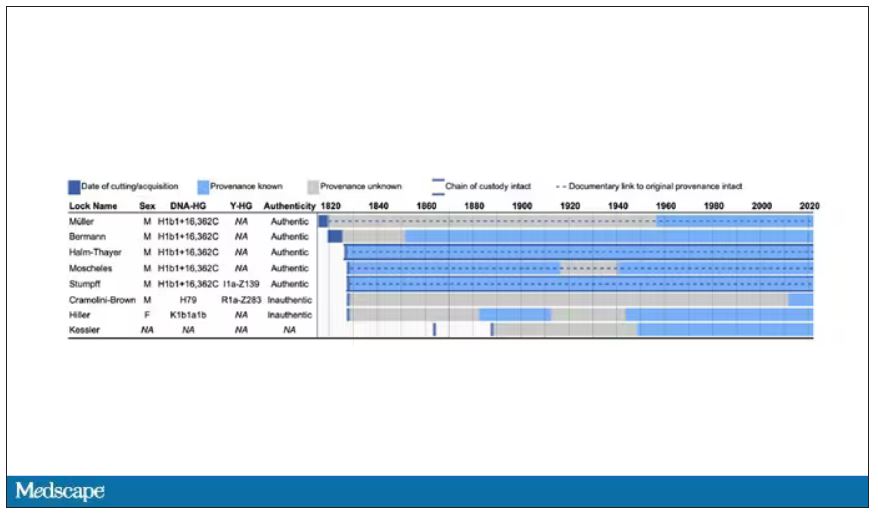

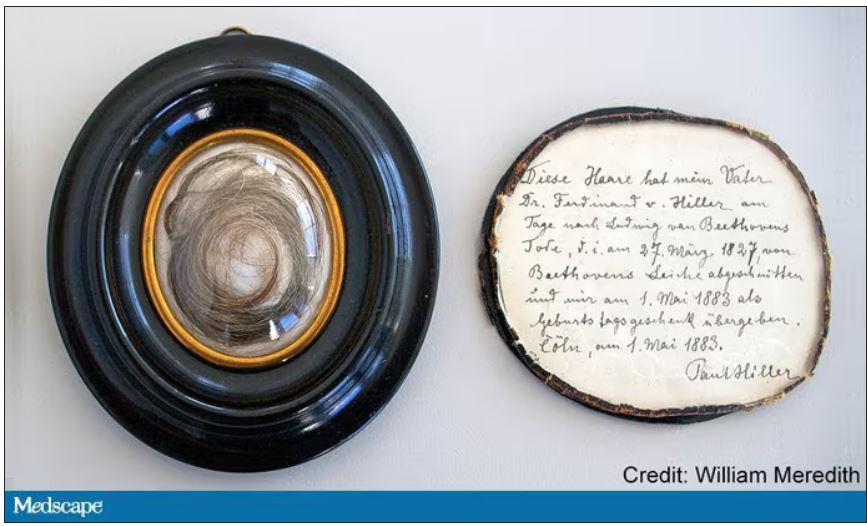

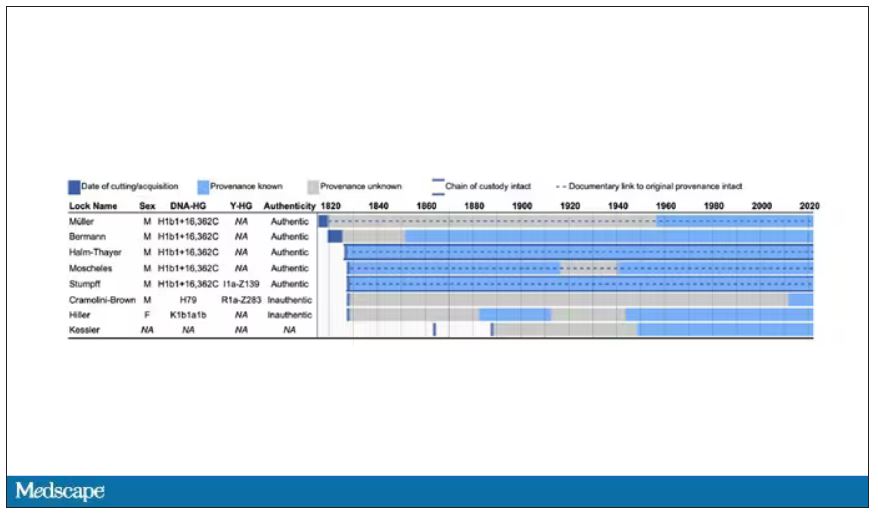

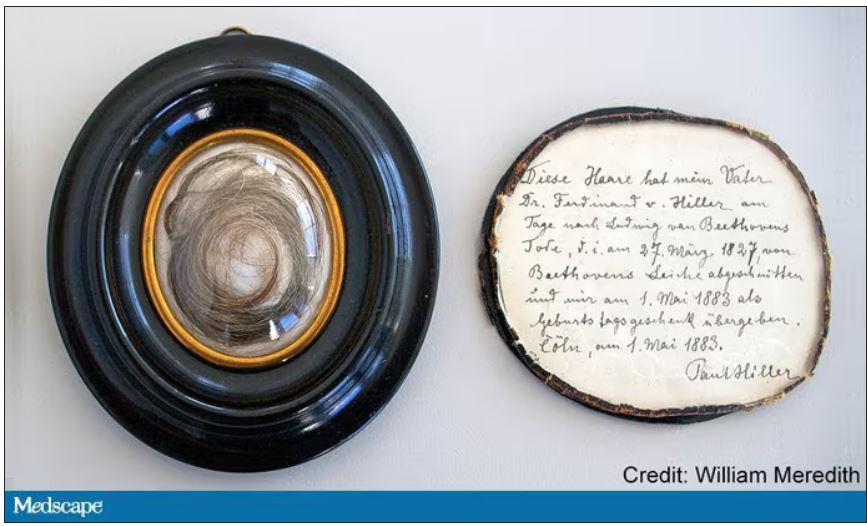

The researchers identified eight locks of hair in private and public collections, all attributed to the maestro.

Four of the samples had an intact chain of custody from the time the hair was cut. DNA sequencing on these four and an additional one of the eight locks came from the same individual, a male of European heritage.

The three locks with less documentation came from three other unrelated individuals. Interestingly, analysis of one of those hair samples – the so-called Hiller Lock – had shown high levels of lead, leading historians to speculate that lead poisoning could account for some of Beethoven’s symptoms.

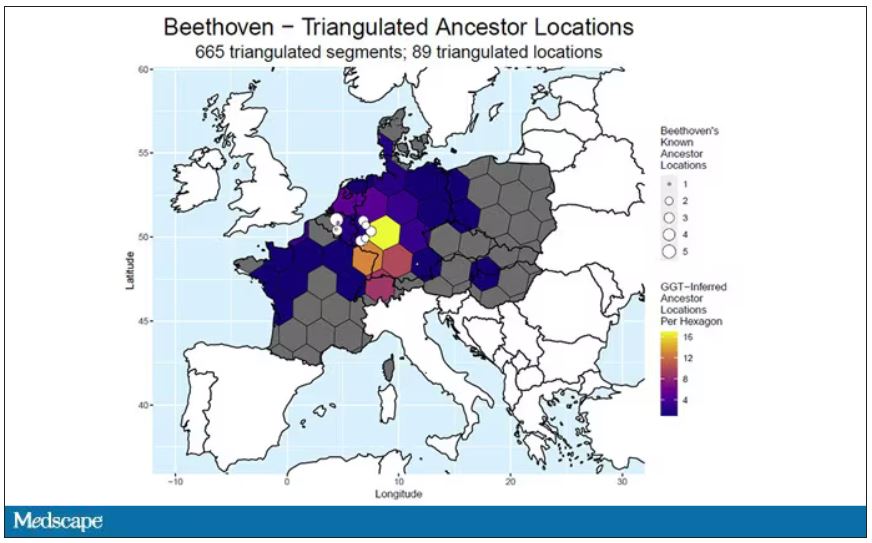

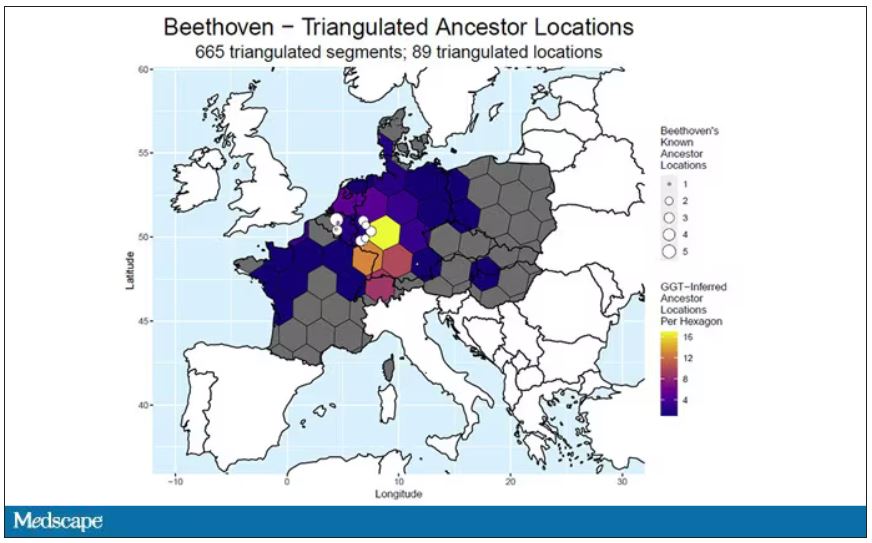

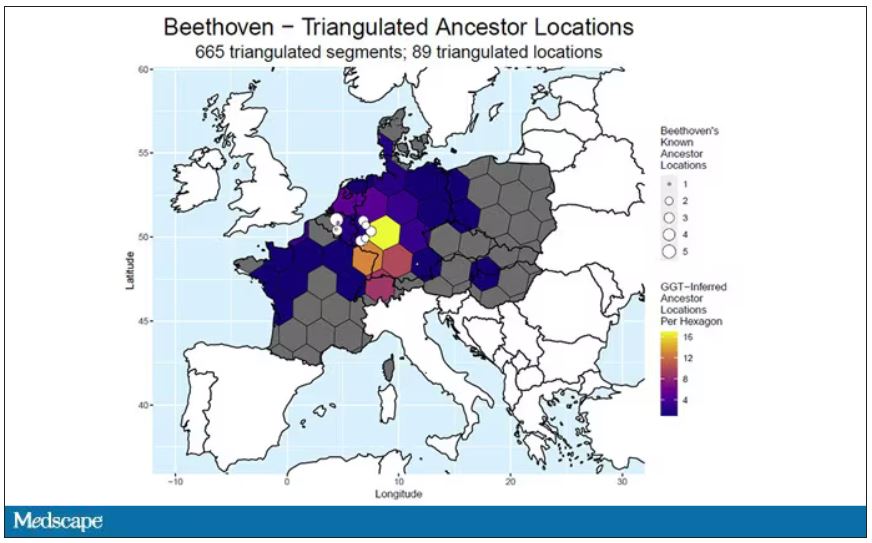

DNA analysis of that hair reveals it to have come from a woman likely of North African, Middle Eastern, or Jewish ancestry. We can no longer presume that plumbism was involved in Beethoven’s death. Beethoven’s ancestry turns out to be less exotic and maps quite well to ethnic German populations today.

In fact, there are van Beethovens alive as we speak, primarily in Belgium. Genealogic records suggest that these van Beethovens share a common ancestor with the virtuoso composer, a man by the name of Aert van Beethoven.

But the DNA reveals a scandal.

The Y-chromosome that Beethoven inherited was not Aert van Beethoven’s. Questions of Beethoven’s paternity have been raised before, but this evidence strongly suggests an extramarital paternity event, at least in the generations preceding his birth. That’s right – Beethoven may not have been a Beethoven.

With five locks now essentially certain to have come from Beethoven himself, the authors could use DNA analysis to try to explain three significant health problems he experienced throughout his life and death: his hearing loss, his terrible gastrointestinal issues, and his liver failure.

Let’s start with the most disappointing results, explanations for his hearing loss. No genetic cause was forthcoming, though the authors note that they have little to go on in regard to the genetic risk for otosclerosis, to which his hearing loss has often been attributed. Lead poisoning is, of course, possible here, though this report focuses only on genetics – there was no testing for lead – and as I mentioned, the lock that was strongly lead-positive in prior studies is almost certainly inauthentic.

What about his lifelong GI complaints? Some have suggested celiac disease or lactose intolerance as explanations. These can essentially be ruled out by the genetic analysis, which shows no risk alleles for celiac disease and the presence of the lactase-persistence gene which confers the ability to metabolize lactose throughout one’s life. IBS is harder to assess genetically, but for what it’s worth, he scored quite low on a polygenic risk score for the condition, in just the 9th percentile of risk. We should probably be looking elsewhere to explain the GI distress.

The genetic information bore much more fruit in regard to his liver disease. Remember that Beethoven’s autopsy showed cirrhosis. His polygenic risk score for liver cirrhosis puts him in the 96th percentile of risk. He was also heterozygous for two variants that can cause hereditary hemochromatosis. The risk for cirrhosis among those with these variants is increased by the use of alcohol. And historical accounts are quite clear that Beethoven consumed more than his share.

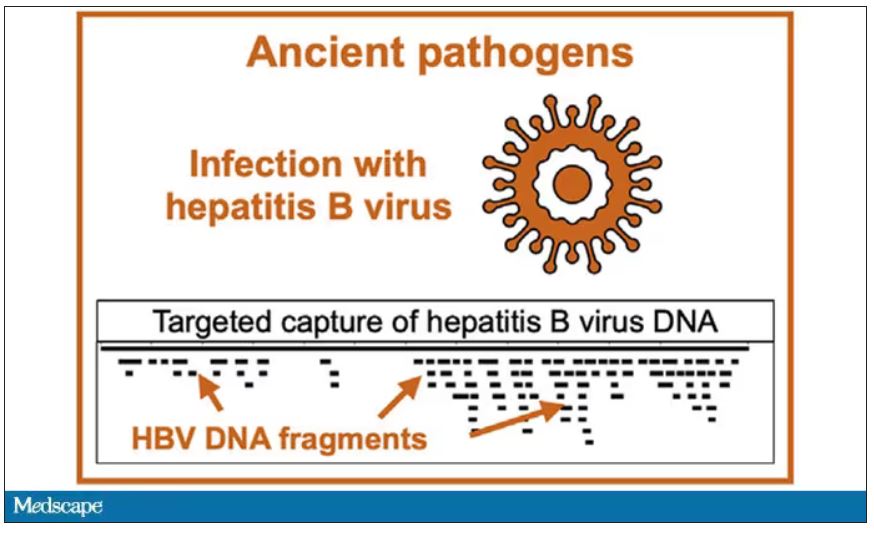

But it wasn’t just Beethoven’s DNA in these hair follicles. Analysis of a follicle from later in his life revealed the unmistakable presence of hepatitis B virus. Endemic in Europe at the time, this was a common cause of liver failure and is likely to have contributed to, if not directly caused, Beethoven’s demise.

It’s hard to read these results and not marvel at the fact that, two centuries after his death, our fascination with Beethoven has led us to probe every corner of his life – his letters, his writings, his medical records, and now his very DNA. What are we actually looking for? Is it relevant to us today what caused his hearing loss? His stomach troubles? Even his death? Will it help any patients in the future? I propose that what we are actually trying to understand is something ineffable: Genius of magnitude that is rarely seen in one or many lifetimes. And our scientific tools, as sharp as they may have become, are still far too blunt to probe the depths of that transcendence.

In any case, friends, no more of these sounds. Let us sing more cheerful songs, more full of joy.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to open this week with a case.

A 56-year-old musician presents with diffuse abdominal pain, cramping, and jaundice. His medical history is notable for years of diffuse abdominal complaints, characterized by disabling bouts of diarrhea.

In addition to the jaundice, this acute illness was accompanied by fever as well as diffuse edema and ascites. The patient underwent several abdominal paracenteses to drain excess fluid. One consulting physician administered alcohol to relieve pain, to little avail.

The patient succumbed to his illness. An autopsy showed diffuse liver injury, as well as papillary necrosis of the kidneys. Notably, the nerves of his auditory canal were noted to be thickened, along with the bony part of the skull, consistent with Paget disease of the bone and explaining, potentially, why the talented musician had gone deaf at such a young age.

An interesting note on social history: The patient had apparently developed some feelings for the niece of that doctor who prescribed alcohol. Her name was Therese, perhaps mistranscribed as Elise, and it seems that he may have written this song for her.

We’re talking about this paper in Current Biology, by Tristan Begg and colleagues, which gives us a look into the very genome of what some would argue is the world’s greatest composer.

The ability to extract DNA from older specimens has transformed the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and history, and now, perhaps, musicology as well.

The researchers identified eight locks of hair in private and public collections, all attributed to the maestro.

Four of the samples had an intact chain of custody from the time the hair was cut. DNA sequencing on these four and an additional one of the eight locks came from the same individual, a male of European heritage.

The three locks with less documentation came from three other unrelated individuals. Interestingly, analysis of one of those hair samples – the so-called Hiller Lock – had shown high levels of lead, leading historians to speculate that lead poisoning could account for some of Beethoven’s symptoms.

DNA analysis of that hair reveals it to have come from a woman likely of North African, Middle Eastern, or Jewish ancestry. We can no longer presume that plumbism was involved in Beethoven’s death. Beethoven’s ancestry turns out to be less exotic and maps quite well to ethnic German populations today.

In fact, there are van Beethovens alive as we speak, primarily in Belgium. Genealogic records suggest that these van Beethovens share a common ancestor with the virtuoso composer, a man by the name of Aert van Beethoven.

But the DNA reveals a scandal.

The Y-chromosome that Beethoven inherited was not Aert van Beethoven’s. Questions of Beethoven’s paternity have been raised before, but this evidence strongly suggests an extramarital paternity event, at least in the generations preceding his birth. That’s right – Beethoven may not have been a Beethoven.

With five locks now essentially certain to have come from Beethoven himself, the authors could use DNA analysis to try to explain three significant health problems he experienced throughout his life and death: his hearing loss, his terrible gastrointestinal issues, and his liver failure.

Let’s start with the most disappointing results, explanations for his hearing loss. No genetic cause was forthcoming, though the authors note that they have little to go on in regard to the genetic risk for otosclerosis, to which his hearing loss has often been attributed. Lead poisoning is, of course, possible here, though this report focuses only on genetics – there was no testing for lead – and as I mentioned, the lock that was strongly lead-positive in prior studies is almost certainly inauthentic.

What about his lifelong GI complaints? Some have suggested celiac disease or lactose intolerance as explanations. These can essentially be ruled out by the genetic analysis, which shows no risk alleles for celiac disease and the presence of the lactase-persistence gene which confers the ability to metabolize lactose throughout one’s life. IBS is harder to assess genetically, but for what it’s worth, he scored quite low on a polygenic risk score for the condition, in just the 9th percentile of risk. We should probably be looking elsewhere to explain the GI distress.

The genetic information bore much more fruit in regard to his liver disease. Remember that Beethoven’s autopsy showed cirrhosis. His polygenic risk score for liver cirrhosis puts him in the 96th percentile of risk. He was also heterozygous for two variants that can cause hereditary hemochromatosis. The risk for cirrhosis among those with these variants is increased by the use of alcohol. And historical accounts are quite clear that Beethoven consumed more than his share.

But it wasn’t just Beethoven’s DNA in these hair follicles. Analysis of a follicle from later in his life revealed the unmistakable presence of hepatitis B virus. Endemic in Europe at the time, this was a common cause of liver failure and is likely to have contributed to, if not directly caused, Beethoven’s demise.

It’s hard to read these results and not marvel at the fact that, two centuries after his death, our fascination with Beethoven has led us to probe every corner of his life – his letters, his writings, his medical records, and now his very DNA. What are we actually looking for? Is it relevant to us today what caused his hearing loss? His stomach troubles? Even his death? Will it help any patients in the future? I propose that what we are actually trying to understand is something ineffable: Genius of magnitude that is rarely seen in one or many lifetimes. And our scientific tools, as sharp as they may have become, are still far too blunt to probe the depths of that transcendence.

In any case, friends, no more of these sounds. Let us sing more cheerful songs, more full of joy.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m going to open this week with a case.

A 56-year-old musician presents with diffuse abdominal pain, cramping, and jaundice. His medical history is notable for years of diffuse abdominal complaints, characterized by disabling bouts of diarrhea.

In addition to the jaundice, this acute illness was accompanied by fever as well as diffuse edema and ascites. The patient underwent several abdominal paracenteses to drain excess fluid. One consulting physician administered alcohol to relieve pain, to little avail.

The patient succumbed to his illness. An autopsy showed diffuse liver injury, as well as papillary necrosis of the kidneys. Notably, the nerves of his auditory canal were noted to be thickened, along with the bony part of the skull, consistent with Paget disease of the bone and explaining, potentially, why the talented musician had gone deaf at such a young age.

An interesting note on social history: The patient had apparently developed some feelings for the niece of that doctor who prescribed alcohol. Her name was Therese, perhaps mistranscribed as Elise, and it seems that he may have written this song for her.

We’re talking about this paper in Current Biology, by Tristan Begg and colleagues, which gives us a look into the very genome of what some would argue is the world’s greatest composer.

The ability to extract DNA from older specimens has transformed the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and history, and now, perhaps, musicology as well.

The researchers identified eight locks of hair in private and public collections, all attributed to the maestro.

Four of the samples had an intact chain of custody from the time the hair was cut. DNA sequencing on these four and an additional one of the eight locks came from the same individual, a male of European heritage.

The three locks with less documentation came from three other unrelated individuals. Interestingly, analysis of one of those hair samples – the so-called Hiller Lock – had shown high levels of lead, leading historians to speculate that lead poisoning could account for some of Beethoven’s symptoms.

DNA analysis of that hair reveals it to have come from a woman likely of North African, Middle Eastern, or Jewish ancestry. We can no longer presume that plumbism was involved in Beethoven’s death. Beethoven’s ancestry turns out to be less exotic and maps quite well to ethnic German populations today.

In fact, there are van Beethovens alive as we speak, primarily in Belgium. Genealogic records suggest that these van Beethovens share a common ancestor with the virtuoso composer, a man by the name of Aert van Beethoven.

But the DNA reveals a scandal.

The Y-chromosome that Beethoven inherited was not Aert van Beethoven’s. Questions of Beethoven’s paternity have been raised before, but this evidence strongly suggests an extramarital paternity event, at least in the generations preceding his birth. That’s right – Beethoven may not have been a Beethoven.

With five locks now essentially certain to have come from Beethoven himself, the authors could use DNA analysis to try to explain three significant health problems he experienced throughout his life and death: his hearing loss, his terrible gastrointestinal issues, and his liver failure.

Let’s start with the most disappointing results, explanations for his hearing loss. No genetic cause was forthcoming, though the authors note that they have little to go on in regard to the genetic risk for otosclerosis, to which his hearing loss has often been attributed. Lead poisoning is, of course, possible here, though this report focuses only on genetics – there was no testing for lead – and as I mentioned, the lock that was strongly lead-positive in prior studies is almost certainly inauthentic.

What about his lifelong GI complaints? Some have suggested celiac disease or lactose intolerance as explanations. These can essentially be ruled out by the genetic analysis, which shows no risk alleles for celiac disease and the presence of the lactase-persistence gene which confers the ability to metabolize lactose throughout one’s life. IBS is harder to assess genetically, but for what it’s worth, he scored quite low on a polygenic risk score for the condition, in just the 9th percentile of risk. We should probably be looking elsewhere to explain the GI distress.

The genetic information bore much more fruit in regard to his liver disease. Remember that Beethoven’s autopsy showed cirrhosis. His polygenic risk score for liver cirrhosis puts him in the 96th percentile of risk. He was also heterozygous for two variants that can cause hereditary hemochromatosis. The risk for cirrhosis among those with these variants is increased by the use of alcohol. And historical accounts are quite clear that Beethoven consumed more than his share.

But it wasn’t just Beethoven’s DNA in these hair follicles. Analysis of a follicle from later in his life revealed the unmistakable presence of hepatitis B virus. Endemic in Europe at the time, this was a common cause of liver failure and is likely to have contributed to, if not directly caused, Beethoven’s demise.

It’s hard to read these results and not marvel at the fact that, two centuries after his death, our fascination with Beethoven has led us to probe every corner of his life – his letters, his writings, his medical records, and now his very DNA. What are we actually looking for? Is it relevant to us today what caused his hearing loss? His stomach troubles? Even his death? Will it help any patients in the future? I propose that what we are actually trying to understand is something ineffable: Genius of magnitude that is rarely seen in one or many lifetimes. And our scientific tools, as sharp as they may have become, are still far too blunt to probe the depths of that transcendence.

In any case, friends, no more of these sounds. Let us sing more cheerful songs, more full of joy.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fast, cheap ... or accurate?

A recent study on the JAMA Network found that, .

Does this surprise anyone?

One of my friends, a pharmacist, has a sign in his home office: “Fast. Accurate. Cheap. You can’t have all 3.” A true statement. I’ve also seen it at car repair places, but they’re doctors in their own way.

The problem here is that physicians are increasingly squeezed for time. If your only revenue stream is seeing patients, and your expenses are going up (and whose aren’t?) then your options are to either raise your prices or see more patients.

Of course, raising prices in medicine can’t happen for most of us. We’re all tied into insurance contracts, which themselves are pegged to Medicare, as to how much we get paid. I mean, yes, you can raise your prices, but that doesn’t matter. The insurance company will still pay a predetermined amount set years ago, in better economic times, no matter what you charge.

So the only real option for most is to see more patients. Which means less time with each one. Which, inevitably, leads to more snap judgments, inappropriate prescriptions, and mistakes.

Patients may get Fast and Cheap, but Accurate gets sidelined. This is the nature of things. If you don’t have enough time to gather and process data, then you’re less likely to reach the right answer.

There’s also the fact that sometimes it’s easier for anyone to just take the path of least resistance. The patient wants an antibiotic, and you realize it’s going to take less time to hand them a script for one than to explain why they don’t need it for what’s probably a viral infection. Not only that, but then you run the risk of their giving you a bad Yelp review (“incompetent, refused to give me antibiotics when I obviously needed them, 1 star”) and who needs that? If you’re employed by a large health care system a bad online review will get you a talking-to by some nonmedical admin from marketing, saying you’re hurting the practice’s “brand.”

Years ago the satire site The Onion had an article about a doctor who specialized in “giving a shit” - assumedly where Accurate dominates. While none of us may intentionally rush through patients or do half-assed jobs, we also have to deal with pressures of time. There never seems to be enough in a workday.

Nowhere is this more true than in primary care, where the pressures of time, overhead, and a large patient volume intersect. There are patients to see, labs to review, phone calls to return, forms to complete, meetings to attend, samples to sign for ... and probably many other things I’ve left out.

The fact that this situation exists shouldn’t surprise anyone. People talk about “burnout” and “making health care better” but that just seems to be lip service. They give you a free subscription to a meditation app, phone access to a counselor, and a mandatory early morning meeting to discuss stress reduction. Of course, these things take time away from seeing patients, which sort of defeats the whole purpose. Unless you want to do them at home – taking time away from your family, or doing the taxes, or other things you have to do besides your day job.

This is not sustainable for patients, doctors, or the health care system as a whole. But right now the situation is only getting worse, and there aren’t any easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A recent study on the JAMA Network found that, .

Does this surprise anyone?

One of my friends, a pharmacist, has a sign in his home office: “Fast. Accurate. Cheap. You can’t have all 3.” A true statement. I’ve also seen it at car repair places, but they’re doctors in their own way.

The problem here is that physicians are increasingly squeezed for time. If your only revenue stream is seeing patients, and your expenses are going up (and whose aren’t?) then your options are to either raise your prices or see more patients.

Of course, raising prices in medicine can’t happen for most of us. We’re all tied into insurance contracts, which themselves are pegged to Medicare, as to how much we get paid. I mean, yes, you can raise your prices, but that doesn’t matter. The insurance company will still pay a predetermined amount set years ago, in better economic times, no matter what you charge.

So the only real option for most is to see more patients. Which means less time with each one. Which, inevitably, leads to more snap judgments, inappropriate prescriptions, and mistakes.

Patients may get Fast and Cheap, but Accurate gets sidelined. This is the nature of things. If you don’t have enough time to gather and process data, then you’re less likely to reach the right answer.

There’s also the fact that sometimes it’s easier for anyone to just take the path of least resistance. The patient wants an antibiotic, and you realize it’s going to take less time to hand them a script for one than to explain why they don’t need it for what’s probably a viral infection. Not only that, but then you run the risk of their giving you a bad Yelp review (“incompetent, refused to give me antibiotics when I obviously needed them, 1 star”) and who needs that? If you’re employed by a large health care system a bad online review will get you a talking-to by some nonmedical admin from marketing, saying you’re hurting the practice’s “brand.”

Years ago the satire site The Onion had an article about a doctor who specialized in “giving a shit” - assumedly where Accurate dominates. While none of us may intentionally rush through patients or do half-assed jobs, we also have to deal with pressures of time. There never seems to be enough in a workday.

Nowhere is this more true than in primary care, where the pressures of time, overhead, and a large patient volume intersect. There are patients to see, labs to review, phone calls to return, forms to complete, meetings to attend, samples to sign for ... and probably many other things I’ve left out.

The fact that this situation exists shouldn’t surprise anyone. People talk about “burnout” and “making health care better” but that just seems to be lip service. They give you a free subscription to a meditation app, phone access to a counselor, and a mandatory early morning meeting to discuss stress reduction. Of course, these things take time away from seeing patients, which sort of defeats the whole purpose. Unless you want to do them at home – taking time away from your family, or doing the taxes, or other things you have to do besides your day job.

This is not sustainable for patients, doctors, or the health care system as a whole. But right now the situation is only getting worse, and there aren’t any easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A recent study on the JAMA Network found that, .

Does this surprise anyone?

One of my friends, a pharmacist, has a sign in his home office: “Fast. Accurate. Cheap. You can’t have all 3.” A true statement. I’ve also seen it at car repair places, but they’re doctors in their own way.

The problem here is that physicians are increasingly squeezed for time. If your only revenue stream is seeing patients, and your expenses are going up (and whose aren’t?) then your options are to either raise your prices or see more patients.

Of course, raising prices in medicine can’t happen for most of us. We’re all tied into insurance contracts, which themselves are pegged to Medicare, as to how much we get paid. I mean, yes, you can raise your prices, but that doesn’t matter. The insurance company will still pay a predetermined amount set years ago, in better economic times, no matter what you charge.

So the only real option for most is to see more patients. Which means less time with each one. Which, inevitably, leads to more snap judgments, inappropriate prescriptions, and mistakes.

Patients may get Fast and Cheap, but Accurate gets sidelined. This is the nature of things. If you don’t have enough time to gather and process data, then you’re less likely to reach the right answer.

There’s also the fact that sometimes it’s easier for anyone to just take the path of least resistance. The patient wants an antibiotic, and you realize it’s going to take less time to hand them a script for one than to explain why they don’t need it for what’s probably a viral infection. Not only that, but then you run the risk of their giving you a bad Yelp review (“incompetent, refused to give me antibiotics when I obviously needed them, 1 star”) and who needs that? If you’re employed by a large health care system a bad online review will get you a talking-to by some nonmedical admin from marketing, saying you’re hurting the practice’s “brand.”

Years ago the satire site The Onion had an article about a doctor who specialized in “giving a shit” - assumedly where Accurate dominates. While none of us may intentionally rush through patients or do half-assed jobs, we also have to deal with pressures of time. There never seems to be enough in a workday.

Nowhere is this more true than in primary care, where the pressures of time, overhead, and a large patient volume intersect. There are patients to see, labs to review, phone calls to return, forms to complete, meetings to attend, samples to sign for ... and probably many other things I’ve left out.

The fact that this situation exists shouldn’t surprise anyone. People talk about “burnout” and “making health care better” but that just seems to be lip service. They give you a free subscription to a meditation app, phone access to a counselor, and a mandatory early morning meeting to discuss stress reduction. Of course, these things take time away from seeing patients, which sort of defeats the whole purpose. Unless you want to do them at home – taking time away from your family, or doing the taxes, or other things you have to do besides your day job.

This is not sustainable for patients, doctors, or the health care system as a whole. But right now the situation is only getting worse, and there aren’t any easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

COVID can mimic prostate cancer symptoms

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.