User login

The perils of CA-125 as a diagnostic tool in patients with adnexal masses

CA-125, or cancer antigen 125, is an epitope (antigen) on the transmembrane glycoprotein MUC16, or mucin 16. This protein is expressed on the surface of tissue derived from embryonic coelomic and Müllerian epithelium including the reproductive tract. CA-125 is also expressed in other tissue such as the pleura, lungs, pericardium, intestines, and kidneys. MUC16 plays an important role in tumor proliferation, invasiveness, and cell motility.1 In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), CA-125 may be found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells. It is shed in the bloodstream and can be quantified using a serum test.

There are a number of CA-125 assays in commercial use, and although none have been deemed to be clinically superior, there can be some differences between assays. It is important, if possible, to use the same assay when following serial CA-125 values. Most frequently, this will mean getting the test through the same laboratory.

CA-125 has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in patients with a current or prior diagnosis of ovarian cancer to monitor treatment response, progression of disease, or disease recurrence.

It is frequently used off label in the workup of adnexal masses, while not FDA approved. CA-125 and other serum biomarkers may help determine the etiology of an adnexal mass; however, they are not diagnostic and should be used thoughtfully. It is important to have conversations with patients before ordering a CA-125 (or other serum biomarkers) about potential results and their effect on diagnosis and treatment. This will lessen some patient anxiety when tests results become available, especially in the setting of autoreleasing results under the Cures Act.

One of the reasons that CA-125 can be difficult to interpret when used as a diagnostic tool is the number of nonmalignant disease processes that can result in CA-125 elevations. CA-125 can be elevated in inflammatory and infectious disease states, including but not limited to, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, diverticulitis, and pneumonia. Severe/critical COVID-19 infection has recently been found to be associated with increased levels of CA-125.2 It is important to obtain a complete medical history and to take specific note of any current or recent flares in inflammatory or infectious processes that could contribute to CA-125 elevations.

Special caution should be taken in premenopausal patients. The sensitivity and specificity of CA-125 are lower in this cohort of patients compared to postmenopausal women. This is multifactorial but in part due to gynecologic conditions that can increase CA-125, such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis, and the higher incidence of nonepithelial ovarian cancers (which frequently have different serum biomarkers) in younger patients. A patient’s gynecologic history, her age, and ultrasound or other imaging findings should help determine what, if any, serum biomarkers are appropriate for workup of an adnexal mass rather than the default ordering of CA-125 to determine need for referral to gynecologic oncology. If the decision has been made to take the patient to the operating room, CA-125 is not approved as a triage tool to guide who best to perform the surgery. In this case, one of two serum tumor marker panel tests that has received FDA approval for triage after the decision for surgery has been made (the multivariate index assay or the risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm) should be used.

When considering its ability to serve as a diagnostic test for ovarian cancer, the sensitivity of CA-125 is affected by the number of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who have a test result that falls within the normal range (up to 50% of patients with stage I disease).3 The specificity of CA-125 is affected by the large number of nonmalignant conditions that can cause its elevation. Depending on the age of the patient, her menopausal status, comorbid conditions, and reason for obtaining serum biomarkers (e.g., decision for surgery has already been made), CA-125 (or CA-125 alone) may not be the best tool to use in the workup of an adnexal mass and can cause significant patient anxiety. In the setting of acute disease, such as COVID-19 infection, it may be better to delay obtaining serum biomarkers for the work-up of an adnexal mass. If delay is not feasible, then repeat serum biomarkers once the acute phase of illness has passed.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Thériault C et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;121(3):434-43.

2. Wei X et al. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2036-41.

3. Zurawski VR Jr et al. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:677-80.

CA-125, or cancer antigen 125, is an epitope (antigen) on the transmembrane glycoprotein MUC16, or mucin 16. This protein is expressed on the surface of tissue derived from embryonic coelomic and Müllerian epithelium including the reproductive tract. CA-125 is also expressed in other tissue such as the pleura, lungs, pericardium, intestines, and kidneys. MUC16 plays an important role in tumor proliferation, invasiveness, and cell motility.1 In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), CA-125 may be found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells. It is shed in the bloodstream and can be quantified using a serum test.

There are a number of CA-125 assays in commercial use, and although none have been deemed to be clinically superior, there can be some differences between assays. It is important, if possible, to use the same assay when following serial CA-125 values. Most frequently, this will mean getting the test through the same laboratory.

CA-125 has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in patients with a current or prior diagnosis of ovarian cancer to monitor treatment response, progression of disease, or disease recurrence.

It is frequently used off label in the workup of adnexal masses, while not FDA approved. CA-125 and other serum biomarkers may help determine the etiology of an adnexal mass; however, they are not diagnostic and should be used thoughtfully. It is important to have conversations with patients before ordering a CA-125 (or other serum biomarkers) about potential results and their effect on diagnosis and treatment. This will lessen some patient anxiety when tests results become available, especially in the setting of autoreleasing results under the Cures Act.

One of the reasons that CA-125 can be difficult to interpret when used as a diagnostic tool is the number of nonmalignant disease processes that can result in CA-125 elevations. CA-125 can be elevated in inflammatory and infectious disease states, including but not limited to, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, diverticulitis, and pneumonia. Severe/critical COVID-19 infection has recently been found to be associated with increased levels of CA-125.2 It is important to obtain a complete medical history and to take specific note of any current or recent flares in inflammatory or infectious processes that could contribute to CA-125 elevations.

Special caution should be taken in premenopausal patients. The sensitivity and specificity of CA-125 are lower in this cohort of patients compared to postmenopausal women. This is multifactorial but in part due to gynecologic conditions that can increase CA-125, such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis, and the higher incidence of nonepithelial ovarian cancers (which frequently have different serum biomarkers) in younger patients. A patient’s gynecologic history, her age, and ultrasound or other imaging findings should help determine what, if any, serum biomarkers are appropriate for workup of an adnexal mass rather than the default ordering of CA-125 to determine need for referral to gynecologic oncology. If the decision has been made to take the patient to the operating room, CA-125 is not approved as a triage tool to guide who best to perform the surgery. In this case, one of two serum tumor marker panel tests that has received FDA approval for triage after the decision for surgery has been made (the multivariate index assay or the risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm) should be used.

When considering its ability to serve as a diagnostic test for ovarian cancer, the sensitivity of CA-125 is affected by the number of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who have a test result that falls within the normal range (up to 50% of patients with stage I disease).3 The specificity of CA-125 is affected by the large number of nonmalignant conditions that can cause its elevation. Depending on the age of the patient, her menopausal status, comorbid conditions, and reason for obtaining serum biomarkers (e.g., decision for surgery has already been made), CA-125 (or CA-125 alone) may not be the best tool to use in the workup of an adnexal mass and can cause significant patient anxiety. In the setting of acute disease, such as COVID-19 infection, it may be better to delay obtaining serum biomarkers for the work-up of an adnexal mass. If delay is not feasible, then repeat serum biomarkers once the acute phase of illness has passed.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Thériault C et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;121(3):434-43.

2. Wei X et al. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2036-41.

3. Zurawski VR Jr et al. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:677-80.

CA-125, or cancer antigen 125, is an epitope (antigen) on the transmembrane glycoprotein MUC16, or mucin 16. This protein is expressed on the surface of tissue derived from embryonic coelomic and Müllerian epithelium including the reproductive tract. CA-125 is also expressed in other tissue such as the pleura, lungs, pericardium, intestines, and kidneys. MUC16 plays an important role in tumor proliferation, invasiveness, and cell motility.1 In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), CA-125 may be found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells. It is shed in the bloodstream and can be quantified using a serum test.

There are a number of CA-125 assays in commercial use, and although none have been deemed to be clinically superior, there can be some differences between assays. It is important, if possible, to use the same assay when following serial CA-125 values. Most frequently, this will mean getting the test through the same laboratory.

CA-125 has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in patients with a current or prior diagnosis of ovarian cancer to monitor treatment response, progression of disease, or disease recurrence.

It is frequently used off label in the workup of adnexal masses, while not FDA approved. CA-125 and other serum biomarkers may help determine the etiology of an adnexal mass; however, they are not diagnostic and should be used thoughtfully. It is important to have conversations with patients before ordering a CA-125 (or other serum biomarkers) about potential results and their effect on diagnosis and treatment. This will lessen some patient anxiety when tests results become available, especially in the setting of autoreleasing results under the Cures Act.

One of the reasons that CA-125 can be difficult to interpret when used as a diagnostic tool is the number of nonmalignant disease processes that can result in CA-125 elevations. CA-125 can be elevated in inflammatory and infectious disease states, including but not limited to, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, diverticulitis, and pneumonia. Severe/critical COVID-19 infection has recently been found to be associated with increased levels of CA-125.2 It is important to obtain a complete medical history and to take specific note of any current or recent flares in inflammatory or infectious processes that could contribute to CA-125 elevations.

Special caution should be taken in premenopausal patients. The sensitivity and specificity of CA-125 are lower in this cohort of patients compared to postmenopausal women. This is multifactorial but in part due to gynecologic conditions that can increase CA-125, such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis, and the higher incidence of nonepithelial ovarian cancers (which frequently have different serum biomarkers) in younger patients. A patient’s gynecologic history, her age, and ultrasound or other imaging findings should help determine what, if any, serum biomarkers are appropriate for workup of an adnexal mass rather than the default ordering of CA-125 to determine need for referral to gynecologic oncology. If the decision has been made to take the patient to the operating room, CA-125 is not approved as a triage tool to guide who best to perform the surgery. In this case, one of two serum tumor marker panel tests that has received FDA approval for triage after the decision for surgery has been made (the multivariate index assay or the risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm) should be used.

When considering its ability to serve as a diagnostic test for ovarian cancer, the sensitivity of CA-125 is affected by the number of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who have a test result that falls within the normal range (up to 50% of patients with stage I disease).3 The specificity of CA-125 is affected by the large number of nonmalignant conditions that can cause its elevation. Depending on the age of the patient, her menopausal status, comorbid conditions, and reason for obtaining serum biomarkers (e.g., decision for surgery has already been made), CA-125 (or CA-125 alone) may not be the best tool to use in the workup of an adnexal mass and can cause significant patient anxiety. In the setting of acute disease, such as COVID-19 infection, it may be better to delay obtaining serum biomarkers for the work-up of an adnexal mass. If delay is not feasible, then repeat serum biomarkers once the acute phase of illness has passed.

Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Thériault C et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;121(3):434-43.

2. Wei X et al. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2036-41.

3. Zurawski VR Jr et al. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:677-80.

Downtime? Enjoy it

Everything in medicine, and pretty much the universe, is based on averages. Average reduction of seizures, average blood levels, average response to treatment, average insurance reimbursement, average time spent with a new consult.

Statistics are helpful in working through large amounts of data, but on a smaller scale, like my practice, statistics aren’t quite as helpful.

I see, on average, maybe 10 patients per day, consisting of new ones, follow-ups, and electromyography and nerve conduction velocity (EMG/NCV) studies. That is, by far, a smaller number of patients than my colleagues in primary care see, and probably other neurology practices as well. But it works for me.

But that’s on averages and not always. Sometimes we all hit slumps. Who knows why? Everyone is on vacation, or the holidays are coming, or they’ve been abducted by aliens. Whatever the reason, I get the occasional week where I’m pretty bored. Maybe one or two patients in a day. I start to feel like the lonely Maytag repairman behind my desk. I check to see if any drug samples have expired. I wonder if people are actually reading my online reviews and going elsewhere.

Years ago weeks like that terrified me. I was worried my little practice might fail (granted, it still could). But as years – and cycles that make up the averages – go by, they don’t bother me as much.

After 23 years I’ve learned that it’s just part of the normal fluctuations that make up an average. One morning I’ll roll the phones and the lines will explode (figuratively, I hope) with calls. At times like these my secretary seems to grow another pair of arms as she frantically schedules callers, puts others on hold, copies insurance cards, and gives the evil eye to drug reps who step in and ask her if she’s busy.

Then my schedule gets packed. My secretary crams patients in my emergency slots of 7:00, 8:00, and 12:00. MRI results come in that require me to see people sooner rather than later. My “average” of 10 patients per day suddenly doesn’t exist. I go home with a pile of dictations to do and work away into the night to catch up.

With experience we learn to take this in stride. Now, when I hit a slow patch, I remind myself that it’s not the average, and to enjoy it while I can. Read a book, take a long lunch, go home early and nap.

Worrying about where the patients are isn’t productive, or good for your mental health. They know where I am, and will find me when they need me.

. Enjoy the slow times while you can.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Everything in medicine, and pretty much the universe, is based on averages. Average reduction of seizures, average blood levels, average response to treatment, average insurance reimbursement, average time spent with a new consult.

Statistics are helpful in working through large amounts of data, but on a smaller scale, like my practice, statistics aren’t quite as helpful.

I see, on average, maybe 10 patients per day, consisting of new ones, follow-ups, and electromyography and nerve conduction velocity (EMG/NCV) studies. That is, by far, a smaller number of patients than my colleagues in primary care see, and probably other neurology practices as well. But it works for me.

But that’s on averages and not always. Sometimes we all hit slumps. Who knows why? Everyone is on vacation, or the holidays are coming, or they’ve been abducted by aliens. Whatever the reason, I get the occasional week where I’m pretty bored. Maybe one or two patients in a day. I start to feel like the lonely Maytag repairman behind my desk. I check to see if any drug samples have expired. I wonder if people are actually reading my online reviews and going elsewhere.

Years ago weeks like that terrified me. I was worried my little practice might fail (granted, it still could). But as years – and cycles that make up the averages – go by, they don’t bother me as much.

After 23 years I’ve learned that it’s just part of the normal fluctuations that make up an average. One morning I’ll roll the phones and the lines will explode (figuratively, I hope) with calls. At times like these my secretary seems to grow another pair of arms as she frantically schedules callers, puts others on hold, copies insurance cards, and gives the evil eye to drug reps who step in and ask her if she’s busy.

Then my schedule gets packed. My secretary crams patients in my emergency slots of 7:00, 8:00, and 12:00. MRI results come in that require me to see people sooner rather than later. My “average” of 10 patients per day suddenly doesn’t exist. I go home with a pile of dictations to do and work away into the night to catch up.

With experience we learn to take this in stride. Now, when I hit a slow patch, I remind myself that it’s not the average, and to enjoy it while I can. Read a book, take a long lunch, go home early and nap.

Worrying about where the patients are isn’t productive, or good for your mental health. They know where I am, and will find me when they need me.

. Enjoy the slow times while you can.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Everything in medicine, and pretty much the universe, is based on averages. Average reduction of seizures, average blood levels, average response to treatment, average insurance reimbursement, average time spent with a new consult.

Statistics are helpful in working through large amounts of data, but on a smaller scale, like my practice, statistics aren’t quite as helpful.

I see, on average, maybe 10 patients per day, consisting of new ones, follow-ups, and electromyography and nerve conduction velocity (EMG/NCV) studies. That is, by far, a smaller number of patients than my colleagues in primary care see, and probably other neurology practices as well. But it works for me.

But that’s on averages and not always. Sometimes we all hit slumps. Who knows why? Everyone is on vacation, or the holidays are coming, or they’ve been abducted by aliens. Whatever the reason, I get the occasional week where I’m pretty bored. Maybe one or two patients in a day. I start to feel like the lonely Maytag repairman behind my desk. I check to see if any drug samples have expired. I wonder if people are actually reading my online reviews and going elsewhere.

Years ago weeks like that terrified me. I was worried my little practice might fail (granted, it still could). But as years – and cycles that make up the averages – go by, they don’t bother me as much.

After 23 years I’ve learned that it’s just part of the normal fluctuations that make up an average. One morning I’ll roll the phones and the lines will explode (figuratively, I hope) with calls. At times like these my secretary seems to grow another pair of arms as she frantically schedules callers, puts others on hold, copies insurance cards, and gives the evil eye to drug reps who step in and ask her if she’s busy.

Then my schedule gets packed. My secretary crams patients in my emergency slots of 7:00, 8:00, and 12:00. MRI results come in that require me to see people sooner rather than later. My “average” of 10 patients per day suddenly doesn’t exist. I go home with a pile of dictations to do and work away into the night to catch up.

With experience we learn to take this in stride. Now, when I hit a slow patch, I remind myself that it’s not the average, and to enjoy it while I can. Read a book, take a long lunch, go home early and nap.

Worrying about where the patients are isn’t productive, or good for your mental health. They know where I am, and will find me when they need me.

. Enjoy the slow times while you can.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Fever after a tropical trip: A guide to differential diagnosis

After 2 years of a pandemic in which traveling was barely possible, tropical diseases are becoming important once more. At a 2022 conference for internal medicine specialists, tropical medicine specialist Fritz Holst, MD, of the Center for Tropical and Travel Medicine in Marburg, Germany, explained what questions you should be asking travelers with a fever at your practice and how to proceed with a suspected case.

The following article is based on the lecture: “Differential Diagnosis of Fever After a Trip to the Tropics,” which Dr. Holst gave at the 128th conference of the German Society of Internal Medicine.

A meta-analysis of studies concerning the topic, “returnee travelers from the tropics with fever,” was published in 2020. According to the analysis, purely tropical infections make up a third (33%) of fever diagnoses worldwide following an exotic trip. Malaria accounts for a fifth (22%), 5% are dengue fever, and 2.2% are typhoid (enteric fever).

In 26% of the returnee travelers investigated, nontropical infections were the cause of the fever. Acute gastroenteritis was responsible for 14%, and respiratory infections were responsible for 13%. In 18% of the cases, the cause of the fever remained unclear.

In Germany, the number of malaria cases has increased, said Dr. Holst. In Hessen, for example, there was recently a malaria fatality. “What we should do has been forgotten again,” he warned. More attention should also be paid once more to prophylaxis.

How to proceed

Dr. Holst described the following steps for treating recently returned travelers who are sick:

- Severely ill or not: If there are signs of a severe disease, such as dyspnea, signs of bleeding, hypotension, or central nervous system symptoms, the patient should be referred to a clinic. A diagnosis should be made within 1 day and treatment should be started.

- Transmissible or dangerous disease: This question should be quickly clarified to protect health care personnel, especially those treating patients. By using a thorough medical history (discussed below), a range of diseases may be clarified.

- Disease outbreak in destination country: Find out about possible disease outbreaks in the country that the traveler visited.

- Malaria? Immediate diagnostics: Malaria should always be excluded in patients at the practice on the same day by using a thick blood smear, even if no fever is present. If this is not possible because of time constraints, the affected person should be transferred directly to the clinic.

- Fever independent of the travel? Exclude other causes of the fever (for example, endocarditis).

- Involve tropical medicine specialists in a timely manner.

Nine mandatory questions

Dr. Holst also listed nine questions that clinicians should ask this patient population.

Where were you exactly?

Depending on the regional prevalence of tropical diseases, certain pathogens can be excluded quickly. Approximately 35% of travelers returning from Africa have malaria, whereas typhoid is much rarer. In contrast, typhoid and dengue fever are much more widespread in Southeast Asia. In Latin America, this is the case for both dengue fever and leptospirosis.

When did you travel?

By using the incubation time of the pathogen in question, as well as the time of return journey, you can determine which diseases are possible and which are not. In one patient who visited the practice 4 weeks after his return, dengue or typhoid were excluded.

Where did you stay overnight?

Whether in an unhygienic bed or under the stars, the question regarding how and where travelers stayed overnight provides important evidence of the following nocturnal vectors:

- Sandflies: Leishmaniasis

- Kissing bugs: Chagas disease

- Fleas: Spotted fever, bubonic plague

- Mosquitoes: Malaria, dengue, filariasis

What did you eat?

Many infections can be attributed to careless eating. For example, when eating fish, crabs, crawfish, or frogs, especially if raw, liver fluke, lung fluke, or ciguatera should be considered. Mussel toxins have been found on the coast of Kenya and even in the south of France. In North African countries, you should be cautious when eating nonpasteurized milk products (for example, camel milk). They can transmit the pathogens for brucellosis and tuberculosis. In beef or pork that has not been cooked thoroughly, there is the risk of trichinosis or of a tapeworm. Even vegetarians need to be careful. Infections with the common liver fluke are possible after eating watercress.

What have you been doing?

You can only get some diseases through certain activities, said Dr. Holst. If long-distance travelers tell you about the following excursions, prick up your ears:

- Freshwater contact: Schistosomiasis, leptospirosis

- Caving: Histoplasmosis, rabies

- Excavations: Anthrax, coccidioidomycosis

- Camel tour: MERS coronavirus (Do not mount a sniffling camel!)

- Walking around barefoot: Strongyloides, hookworm

Was there contact with animals?

Because of the risk of rabies following contact with cats or biting apes, Dr. Holst advised long-distance travelers to get vaccinated.

Were there new sexual partners?

In the event of new sexual contacts, tests for hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV should be performed.

Are you undergoing medical treatment?

The patient may already be under medical supervision because of having a disease.

What prophylactic measures did you take before traveling?

To progress in the differential diagnosis, questions should also be asked regarding prophylactic measures. Vaccination against hepatitis A provides very efficient infection protection, whereas vaccines against typhoid offer a much lower level of protection.

Diagnostic tests

As long as there are no abnormalities, such as meningism or heart murmurs, further diagnostics include routine infectiologic laboratory investigations (C-reactive protein, blood count, etc), blood culture (aerobic, anaerobic), a urine dipstick test, and rapid tests for malaria and dengue.

To exclude malaria, a thick blood smear should always be performed on the same day, said Dr. Holst. “The rapid test is occasionally negative. But you often only detect tertian malaria in the thick blood smear. And you have to repeat the diagnostics the following day.” For this, it is important to know that a single test result does not exclude malaria right away. In contrast, detecting malaria antibodies is obsolete. Depending on the result, further tests include serologies, antigen investigations, and polymerase chain reaction.

Treat early

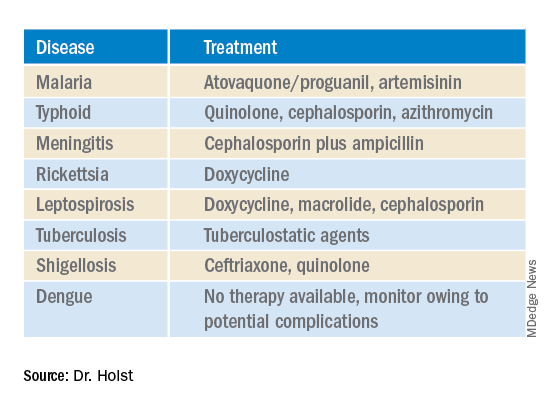

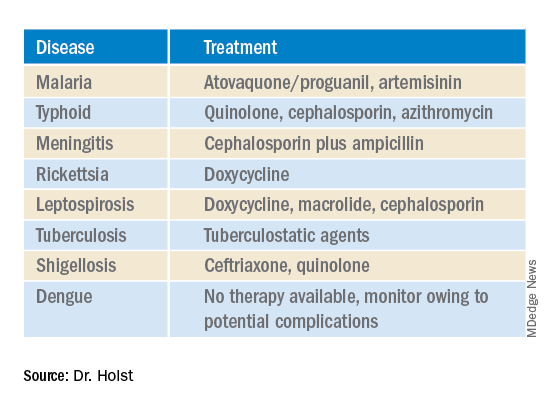

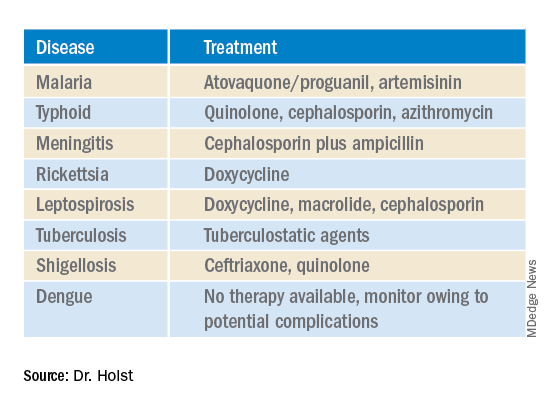

A complete set of results is not always available promptly. Experts recommend that, “if you already have a hunch, then start the therapy, even without a definite diagnosis.” This applies in particular for the suspected diagnoses in the following table.

This article was translated from Coliquio. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

After 2 years of a pandemic in which traveling was barely possible, tropical diseases are becoming important once more. At a 2022 conference for internal medicine specialists, tropical medicine specialist Fritz Holst, MD, of the Center for Tropical and Travel Medicine in Marburg, Germany, explained what questions you should be asking travelers with a fever at your practice and how to proceed with a suspected case.

The following article is based on the lecture: “Differential Diagnosis of Fever After a Trip to the Tropics,” which Dr. Holst gave at the 128th conference of the German Society of Internal Medicine.

A meta-analysis of studies concerning the topic, “returnee travelers from the tropics with fever,” was published in 2020. According to the analysis, purely tropical infections make up a third (33%) of fever diagnoses worldwide following an exotic trip. Malaria accounts for a fifth (22%), 5% are dengue fever, and 2.2% are typhoid (enteric fever).

In 26% of the returnee travelers investigated, nontropical infections were the cause of the fever. Acute gastroenteritis was responsible for 14%, and respiratory infections were responsible for 13%. In 18% of the cases, the cause of the fever remained unclear.

In Germany, the number of malaria cases has increased, said Dr. Holst. In Hessen, for example, there was recently a malaria fatality. “What we should do has been forgotten again,” he warned. More attention should also be paid once more to prophylaxis.

How to proceed

Dr. Holst described the following steps for treating recently returned travelers who are sick:

- Severely ill or not: If there are signs of a severe disease, such as dyspnea, signs of bleeding, hypotension, or central nervous system symptoms, the patient should be referred to a clinic. A diagnosis should be made within 1 day and treatment should be started.

- Transmissible or dangerous disease: This question should be quickly clarified to protect health care personnel, especially those treating patients. By using a thorough medical history (discussed below), a range of diseases may be clarified.

- Disease outbreak in destination country: Find out about possible disease outbreaks in the country that the traveler visited.

- Malaria? Immediate diagnostics: Malaria should always be excluded in patients at the practice on the same day by using a thick blood smear, even if no fever is present. If this is not possible because of time constraints, the affected person should be transferred directly to the clinic.

- Fever independent of the travel? Exclude other causes of the fever (for example, endocarditis).

- Involve tropical medicine specialists in a timely manner.

Nine mandatory questions

Dr. Holst also listed nine questions that clinicians should ask this patient population.

Where were you exactly?

Depending on the regional prevalence of tropical diseases, certain pathogens can be excluded quickly. Approximately 35% of travelers returning from Africa have malaria, whereas typhoid is much rarer. In contrast, typhoid and dengue fever are much more widespread in Southeast Asia. In Latin America, this is the case for both dengue fever and leptospirosis.

When did you travel?

By using the incubation time of the pathogen in question, as well as the time of return journey, you can determine which diseases are possible and which are not. In one patient who visited the practice 4 weeks after his return, dengue or typhoid were excluded.

Where did you stay overnight?

Whether in an unhygienic bed or under the stars, the question regarding how and where travelers stayed overnight provides important evidence of the following nocturnal vectors:

- Sandflies: Leishmaniasis

- Kissing bugs: Chagas disease

- Fleas: Spotted fever, bubonic plague

- Mosquitoes: Malaria, dengue, filariasis

What did you eat?

Many infections can be attributed to careless eating. For example, when eating fish, crabs, crawfish, or frogs, especially if raw, liver fluke, lung fluke, or ciguatera should be considered. Mussel toxins have been found on the coast of Kenya and even in the south of France. In North African countries, you should be cautious when eating nonpasteurized milk products (for example, camel milk). They can transmit the pathogens for brucellosis and tuberculosis. In beef or pork that has not been cooked thoroughly, there is the risk of trichinosis or of a tapeworm. Even vegetarians need to be careful. Infections with the common liver fluke are possible after eating watercress.

What have you been doing?

You can only get some diseases through certain activities, said Dr. Holst. If long-distance travelers tell you about the following excursions, prick up your ears:

- Freshwater contact: Schistosomiasis, leptospirosis

- Caving: Histoplasmosis, rabies

- Excavations: Anthrax, coccidioidomycosis

- Camel tour: MERS coronavirus (Do not mount a sniffling camel!)

- Walking around barefoot: Strongyloides, hookworm

Was there contact with animals?

Because of the risk of rabies following contact with cats or biting apes, Dr. Holst advised long-distance travelers to get vaccinated.

Were there new sexual partners?

In the event of new sexual contacts, tests for hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV should be performed.

Are you undergoing medical treatment?

The patient may already be under medical supervision because of having a disease.

What prophylactic measures did you take before traveling?

To progress in the differential diagnosis, questions should also be asked regarding prophylactic measures. Vaccination against hepatitis A provides very efficient infection protection, whereas vaccines against typhoid offer a much lower level of protection.

Diagnostic tests

As long as there are no abnormalities, such as meningism or heart murmurs, further diagnostics include routine infectiologic laboratory investigations (C-reactive protein, blood count, etc), blood culture (aerobic, anaerobic), a urine dipstick test, and rapid tests for malaria and dengue.

To exclude malaria, a thick blood smear should always be performed on the same day, said Dr. Holst. “The rapid test is occasionally negative. But you often only detect tertian malaria in the thick blood smear. And you have to repeat the diagnostics the following day.” For this, it is important to know that a single test result does not exclude malaria right away. In contrast, detecting malaria antibodies is obsolete. Depending on the result, further tests include serologies, antigen investigations, and polymerase chain reaction.

Treat early

A complete set of results is not always available promptly. Experts recommend that, “if you already have a hunch, then start the therapy, even without a definite diagnosis.” This applies in particular for the suspected diagnoses in the following table.

This article was translated from Coliquio. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

After 2 years of a pandemic in which traveling was barely possible, tropical diseases are becoming important once more. At a 2022 conference for internal medicine specialists, tropical medicine specialist Fritz Holst, MD, of the Center for Tropical and Travel Medicine in Marburg, Germany, explained what questions you should be asking travelers with a fever at your practice and how to proceed with a suspected case.

The following article is based on the lecture: “Differential Diagnosis of Fever After a Trip to the Tropics,” which Dr. Holst gave at the 128th conference of the German Society of Internal Medicine.

A meta-analysis of studies concerning the topic, “returnee travelers from the tropics with fever,” was published in 2020. According to the analysis, purely tropical infections make up a third (33%) of fever diagnoses worldwide following an exotic trip. Malaria accounts for a fifth (22%), 5% are dengue fever, and 2.2% are typhoid (enteric fever).

In 26% of the returnee travelers investigated, nontropical infections were the cause of the fever. Acute gastroenteritis was responsible for 14%, and respiratory infections were responsible for 13%. In 18% of the cases, the cause of the fever remained unclear.

In Germany, the number of malaria cases has increased, said Dr. Holst. In Hessen, for example, there was recently a malaria fatality. “What we should do has been forgotten again,” he warned. More attention should also be paid once more to prophylaxis.

How to proceed

Dr. Holst described the following steps for treating recently returned travelers who are sick:

- Severely ill or not: If there are signs of a severe disease, such as dyspnea, signs of bleeding, hypotension, or central nervous system symptoms, the patient should be referred to a clinic. A diagnosis should be made within 1 day and treatment should be started.

- Transmissible or dangerous disease: This question should be quickly clarified to protect health care personnel, especially those treating patients. By using a thorough medical history (discussed below), a range of diseases may be clarified.

- Disease outbreak in destination country: Find out about possible disease outbreaks in the country that the traveler visited.

- Malaria? Immediate diagnostics: Malaria should always be excluded in patients at the practice on the same day by using a thick blood smear, even if no fever is present. If this is not possible because of time constraints, the affected person should be transferred directly to the clinic.

- Fever independent of the travel? Exclude other causes of the fever (for example, endocarditis).

- Involve tropical medicine specialists in a timely manner.

Nine mandatory questions

Dr. Holst also listed nine questions that clinicians should ask this patient population.

Where were you exactly?

Depending on the regional prevalence of tropical diseases, certain pathogens can be excluded quickly. Approximately 35% of travelers returning from Africa have malaria, whereas typhoid is much rarer. In contrast, typhoid and dengue fever are much more widespread in Southeast Asia. In Latin America, this is the case for both dengue fever and leptospirosis.

When did you travel?

By using the incubation time of the pathogen in question, as well as the time of return journey, you can determine which diseases are possible and which are not. In one patient who visited the practice 4 weeks after his return, dengue or typhoid were excluded.

Where did you stay overnight?

Whether in an unhygienic bed or under the stars, the question regarding how and where travelers stayed overnight provides important evidence of the following nocturnal vectors:

- Sandflies: Leishmaniasis

- Kissing bugs: Chagas disease

- Fleas: Spotted fever, bubonic plague

- Mosquitoes: Malaria, dengue, filariasis

What did you eat?

Many infections can be attributed to careless eating. For example, when eating fish, crabs, crawfish, or frogs, especially if raw, liver fluke, lung fluke, or ciguatera should be considered. Mussel toxins have been found on the coast of Kenya and even in the south of France. In North African countries, you should be cautious when eating nonpasteurized milk products (for example, camel milk). They can transmit the pathogens for brucellosis and tuberculosis. In beef or pork that has not been cooked thoroughly, there is the risk of trichinosis or of a tapeworm. Even vegetarians need to be careful. Infections with the common liver fluke are possible after eating watercress.

What have you been doing?

You can only get some diseases through certain activities, said Dr. Holst. If long-distance travelers tell you about the following excursions, prick up your ears:

- Freshwater contact: Schistosomiasis, leptospirosis

- Caving: Histoplasmosis, rabies

- Excavations: Anthrax, coccidioidomycosis

- Camel tour: MERS coronavirus (Do not mount a sniffling camel!)

- Walking around barefoot: Strongyloides, hookworm

Was there contact with animals?

Because of the risk of rabies following contact with cats or biting apes, Dr. Holst advised long-distance travelers to get vaccinated.

Were there new sexual partners?

In the event of new sexual contacts, tests for hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV should be performed.

Are you undergoing medical treatment?

The patient may already be under medical supervision because of having a disease.

What prophylactic measures did you take before traveling?

To progress in the differential diagnosis, questions should also be asked regarding prophylactic measures. Vaccination against hepatitis A provides very efficient infection protection, whereas vaccines against typhoid offer a much lower level of protection.

Diagnostic tests

As long as there are no abnormalities, such as meningism or heart murmurs, further diagnostics include routine infectiologic laboratory investigations (C-reactive protein, blood count, etc), blood culture (aerobic, anaerobic), a urine dipstick test, and rapid tests for malaria and dengue.

To exclude malaria, a thick blood smear should always be performed on the same day, said Dr. Holst. “The rapid test is occasionally negative. But you often only detect tertian malaria in the thick blood smear. And you have to repeat the diagnostics the following day.” For this, it is important to know that a single test result does not exclude malaria right away. In contrast, detecting malaria antibodies is obsolete. Depending on the result, further tests include serologies, antigen investigations, and polymerase chain reaction.

Treat early

A complete set of results is not always available promptly. Experts recommend that, “if you already have a hunch, then start the therapy, even without a definite diagnosis.” This applies in particular for the suspected diagnoses in the following table.

This article was translated from Coliquio. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Does COVID-19 raise the risk for diabetes?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Does having had a COVID-19 infection increase your risk for the development of diabetes subsequently? Some data say yes and other data say no. No matter what, it’s obviously important to screen people for diabetes routinely, pandemic or not. Remember, screening should start at age 35.

For over a decade, we have known that SARS-type viruses bind to beta cells. This could cause either direct damage to the beta cell or in some way trigger beta cell autoimmunity. We also know that COVID-19 infection increases the levels of inflammatory mediators, which could cause damage to beta cells and potentially to insulin receptors. There is a potential that having had a COVID-19 infection could increase rates of developing type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes.

However, there are other possible causes for people to develop diabetes after having a COVID-19 infection. A COVID-19 infection could cause one to seek medical care, unmasking latent type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes by causing infection-related insulin resistance and worsening preexisting mild hypoglycemia. In addition, people could have sought more medical care in the years since the pandemic has been ebbing, which may make it look like cases have increased.

For example, during the worst of the pandemic, I had multiple referrals for “COVID-19–caused new-onset diabetes” only to find that the patient had an A1c level above 10% and a history of mildly elevated blood glucose levels. This suggests to me that COVID-19 did not cause the diabetes per se but rather worsened an underlying glucose abnormality.

Since the pandemic has improved, I have also seen people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes that I think is associated with pandemic-related weight gain and inactivity.

The bigger issue is what is happening to people after COVID-19 infection who lack risk factors. What about those who we didn’t think were at high risk to get diabetes to begin with and didn’t have prediabetes?

An article by Xie and Al-Aly in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology showed an increase in rates of diabetes in a large VA cohort among those who had a COVID-19 infection compared with both a contemporaneous control who did not have COVID-19 and a historical control. The researchers looked at the patient data 1 year after they’d had COVID-19, so it wasn’t the immediate post–COVID-19 phase but several months later.

They found that the risk for incident type 2 diabetes development was increased by 40% after adjusting for many risk factors. This included individuals who didn’t have traditional risk factors before they developed type 2 diabetes.

What does this mean clinically? First, pandemic or not, people need screening for diabetes and encouragement to have a healthy lifestyle. There may be an increased risk for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes after COVID-19 infection due to a variety of different mechanisms.

As for people with type 1 diabetes, we also don’t know if having a COVID-19 infection increases their risk. We do know that there was an increase in the severity of diabetic ketoacidosis presentation during the pandemic, so we need to be sure that we reinforce sick-day rules with our patients with type 1 diabetes and that all individuals with type 1 diabetes have the ability to test their ketone levels at home.

In people with new-onset diabetes, whether type 1 or type 2, caused by COVID-19 or not, we need to treat appropriately based on their clinical situation.

Data from registries started during the pandemic will provide more definitive answers and help us find out if there is a relationship between having had COVID-19 infection and developing diabetes.

Perhaps that can help us better understand the mechanisms behind the development of diabetes overall.

Dr. Peters is professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, MannKind Corporation, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, and Zafgen. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Does having had a COVID-19 infection increase your risk for the development of diabetes subsequently? Some data say yes and other data say no. No matter what, it’s obviously important to screen people for diabetes routinely, pandemic or not. Remember, screening should start at age 35.

For over a decade, we have known that SARS-type viruses bind to beta cells. This could cause either direct damage to the beta cell or in some way trigger beta cell autoimmunity. We also know that COVID-19 infection increases the levels of inflammatory mediators, which could cause damage to beta cells and potentially to insulin receptors. There is a potential that having had a COVID-19 infection could increase rates of developing type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes.

However, there are other possible causes for people to develop diabetes after having a COVID-19 infection. A COVID-19 infection could cause one to seek medical care, unmasking latent type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes by causing infection-related insulin resistance and worsening preexisting mild hypoglycemia. In addition, people could have sought more medical care in the years since the pandemic has been ebbing, which may make it look like cases have increased.

For example, during the worst of the pandemic, I had multiple referrals for “COVID-19–caused new-onset diabetes” only to find that the patient had an A1c level above 10% and a history of mildly elevated blood glucose levels. This suggests to me that COVID-19 did not cause the diabetes per se but rather worsened an underlying glucose abnormality.

Since the pandemic has improved, I have also seen people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes that I think is associated with pandemic-related weight gain and inactivity.

The bigger issue is what is happening to people after COVID-19 infection who lack risk factors. What about those who we didn’t think were at high risk to get diabetes to begin with and didn’t have prediabetes?

An article by Xie and Al-Aly in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology showed an increase in rates of diabetes in a large VA cohort among those who had a COVID-19 infection compared with both a contemporaneous control who did not have COVID-19 and a historical control. The researchers looked at the patient data 1 year after they’d had COVID-19, so it wasn’t the immediate post–COVID-19 phase but several months later.

They found that the risk for incident type 2 diabetes development was increased by 40% after adjusting for many risk factors. This included individuals who didn’t have traditional risk factors before they developed type 2 diabetes.

What does this mean clinically? First, pandemic or not, people need screening for diabetes and encouragement to have a healthy lifestyle. There may be an increased risk for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes after COVID-19 infection due to a variety of different mechanisms.

As for people with type 1 diabetes, we also don’t know if having a COVID-19 infection increases their risk. We do know that there was an increase in the severity of diabetic ketoacidosis presentation during the pandemic, so we need to be sure that we reinforce sick-day rules with our patients with type 1 diabetes and that all individuals with type 1 diabetes have the ability to test their ketone levels at home.

In people with new-onset diabetes, whether type 1 or type 2, caused by COVID-19 or not, we need to treat appropriately based on their clinical situation.

Data from registries started during the pandemic will provide more definitive answers and help us find out if there is a relationship between having had COVID-19 infection and developing diabetes.

Perhaps that can help us better understand the mechanisms behind the development of diabetes overall.

Dr. Peters is professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, MannKind Corporation, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, and Zafgen. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Does having had a COVID-19 infection increase your risk for the development of diabetes subsequently? Some data say yes and other data say no. No matter what, it’s obviously important to screen people for diabetes routinely, pandemic or not. Remember, screening should start at age 35.

For over a decade, we have known that SARS-type viruses bind to beta cells. This could cause either direct damage to the beta cell or in some way trigger beta cell autoimmunity. We also know that COVID-19 infection increases the levels of inflammatory mediators, which could cause damage to beta cells and potentially to insulin receptors. There is a potential that having had a COVID-19 infection could increase rates of developing type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes.

However, there are other possible causes for people to develop diabetes after having a COVID-19 infection. A COVID-19 infection could cause one to seek medical care, unmasking latent type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes by causing infection-related insulin resistance and worsening preexisting mild hypoglycemia. In addition, people could have sought more medical care in the years since the pandemic has been ebbing, which may make it look like cases have increased.

For example, during the worst of the pandemic, I had multiple referrals for “COVID-19–caused new-onset diabetes” only to find that the patient had an A1c level above 10% and a history of mildly elevated blood glucose levels. This suggests to me that COVID-19 did not cause the diabetes per se but rather worsened an underlying glucose abnormality.

Since the pandemic has improved, I have also seen people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes that I think is associated with pandemic-related weight gain and inactivity.

The bigger issue is what is happening to people after COVID-19 infection who lack risk factors. What about those who we didn’t think were at high risk to get diabetes to begin with and didn’t have prediabetes?

An article by Xie and Al-Aly in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology showed an increase in rates of diabetes in a large VA cohort among those who had a COVID-19 infection compared with both a contemporaneous control who did not have COVID-19 and a historical control. The researchers looked at the patient data 1 year after they’d had COVID-19, so it wasn’t the immediate post–COVID-19 phase but several months later.

They found that the risk for incident type 2 diabetes development was increased by 40% after adjusting for many risk factors. This included individuals who didn’t have traditional risk factors before they developed type 2 diabetes.

What does this mean clinically? First, pandemic or not, people need screening for diabetes and encouragement to have a healthy lifestyle. There may be an increased risk for the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes after COVID-19 infection due to a variety of different mechanisms.

As for people with type 1 diabetes, we also don’t know if having a COVID-19 infection increases their risk. We do know that there was an increase in the severity of diabetic ketoacidosis presentation during the pandemic, so we need to be sure that we reinforce sick-day rules with our patients with type 1 diabetes and that all individuals with type 1 diabetes have the ability to test their ketone levels at home.

In people with new-onset diabetes, whether type 1 or type 2, caused by COVID-19 or not, we need to treat appropriately based on their clinical situation.

Data from registries started during the pandemic will provide more definitive answers and help us find out if there is a relationship between having had COVID-19 infection and developing diabetes.

Perhaps that can help us better understand the mechanisms behind the development of diabetes overall.

Dr. Peters is professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She disclosed ties with Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, MannKind Corporation, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, and Zafgen. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

20th anniversary and history of cosmetic botulinum toxin type A

The timeline of botulinum toxin discovery began with deadly outbreaks related to contaminated food across Europe in the late 1700s, the largest of which occurred in 1793 in Wildebrad, in southern Germany. In 1811, “prussic acid” was named as the culprit in what was referred to as sausage poisoning. Between 1817 and 1822, German physician Justinus Kerner noted that the active substance interrupted signals from motor nerves to muscles, but spared sensory and cognitive abilities, accurately describing botulism. He hypothesized that this substance could possibly be used as treatment for medical conditions when ingested orally. It wasn’t until 1895 that microbiologist Emile Pierre Van Ermengem, a professor of bacteriology in Belgium, identified the bacterium responsible as Bacillus botulinus, later renamed C. botulinum.

In 1905, it was discovered that C. botulinum produced a substance that affected neurotransmitter function, and between 1895 and 1915, seven toxin serotypes were recognized. In 1928, Herman Sommer, PhD, at the Hooper Foundation, at the University of California, San Francisco, isolated the most potent serotype: botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A).

In 1946, Carl Lamanna and James Duff developed concentration and crystallization techniques that were subsequently used by Edward Schantz, PhD, at Fort Detrick, Md., for a possible biologic weapon. In 1972, Dr. Schantz took his research to the University of Wisconsin, where he produced a large batch of BoNT-A that remained in clinical use until December 1997.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an ophthalmologist in San Francisco, Alan Scott, MD, began animal studies with BoNT-A supplied by Dr. Schantz, as a possible treatment for strabismus, publishing his first report of BoNT-A in primates in 1973. In 1978, the Food and Drug Administration granted approval to begin testing small amounts of the toxin in human volunteers. In 1980, a landmark paper was published demonstrating that BoNT-A corrects gaze misalignment in humans. By 1989, it was approved as Oculinum by the FDA for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm.

Keen clinical observation and a serendipitous discovery led to botulinum toxin’s first uses for cosmetic purposes. In the mid-1980s, Jean Carruthers, MD, an ophthalmologist in Vancouver, noted an unexpected concomitant improvement of glabellar rhytids in a patient treated with BoNT for blepharospasm. The result of the treatment was a more serene, untroubled expression. Dr. Carruthers discussed the observation with her dermatologist spouse, Alastair Carruthers, MD, who was attempting to use soft tissue–augmenting agents available at the time to soften forehead wrinkles. Intrigued by the possibilities, the Carruthers subsequently injected a small amount of BoNT-A between the eyebrows of their assistant, Cathy Bickerton Swann, also now known as “patient zero” and awaited the results.

Seventeen additional patients followed, aged 34-51, who collectively, would become part of the first report on the efficacy of BoNT-A for cosmetic use – for the treatment of glabellar frown lines – published in 1992.

Between 1992 and 1997, the popularity of off-label use of BoNT-A grew so rapidly that Allergan’s supply temporarily ran out. By 2002, safety and efficacy profiles of use in medical conditions such as strabismus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia, cerebral palsy, poststroke spasticity, hyperhidrosis, headache, and back pain had been well-established, facilitating the comfort and use for cosmetic purposes.

By 2002, open-label studies of more than 800 patients confirmed the efficacy and safety of BoNT for the treatment of dynamic facial rhytids. And in April 2002, the FDA granted approval of BoNT for the nonsurgical reduction of glabellar rhytids. The rest, some would say, is history. On this 20th-year anniversary of the approval of botulinum toxin for cosmetic use, special recognition is given here for the physicians and scientists who were astute enough to make this discovery, as botulinum toxin use remains one of the most popular and effective nonsurgical cosmetic procedures today.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley disclosed that she has been a clinical investigator and consultant for Botox manufacturer Allergan in the past, and manufacturers of other brands of botulinum toxins available for cosmetic use; Dysport (Galderma), Xeomin (Merz), and Jeuveau (Evolus). Dr. Talakoub had no disclosures.

Reference

“Botulinum Toxin: Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology Series 3rd Edition” (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013)

The timeline of botulinum toxin discovery began with deadly outbreaks related to contaminated food across Europe in the late 1700s, the largest of which occurred in 1793 in Wildebrad, in southern Germany. In 1811, “prussic acid” was named as the culprit in what was referred to as sausage poisoning. Between 1817 and 1822, German physician Justinus Kerner noted that the active substance interrupted signals from motor nerves to muscles, but spared sensory and cognitive abilities, accurately describing botulism. He hypothesized that this substance could possibly be used as treatment for medical conditions when ingested orally. It wasn’t until 1895 that microbiologist Emile Pierre Van Ermengem, a professor of bacteriology in Belgium, identified the bacterium responsible as Bacillus botulinus, later renamed C. botulinum.

In 1905, it was discovered that C. botulinum produced a substance that affected neurotransmitter function, and between 1895 and 1915, seven toxin serotypes were recognized. In 1928, Herman Sommer, PhD, at the Hooper Foundation, at the University of California, San Francisco, isolated the most potent serotype: botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A).

In 1946, Carl Lamanna and James Duff developed concentration and crystallization techniques that were subsequently used by Edward Schantz, PhD, at Fort Detrick, Md., for a possible biologic weapon. In 1972, Dr. Schantz took his research to the University of Wisconsin, where he produced a large batch of BoNT-A that remained in clinical use until December 1997.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an ophthalmologist in San Francisco, Alan Scott, MD, began animal studies with BoNT-A supplied by Dr. Schantz, as a possible treatment for strabismus, publishing his first report of BoNT-A in primates in 1973. In 1978, the Food and Drug Administration granted approval to begin testing small amounts of the toxin in human volunteers. In 1980, a landmark paper was published demonstrating that BoNT-A corrects gaze misalignment in humans. By 1989, it was approved as Oculinum by the FDA for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm.

Keen clinical observation and a serendipitous discovery led to botulinum toxin’s first uses for cosmetic purposes. In the mid-1980s, Jean Carruthers, MD, an ophthalmologist in Vancouver, noted an unexpected concomitant improvement of glabellar rhytids in a patient treated with BoNT for blepharospasm. The result of the treatment was a more serene, untroubled expression. Dr. Carruthers discussed the observation with her dermatologist spouse, Alastair Carruthers, MD, who was attempting to use soft tissue–augmenting agents available at the time to soften forehead wrinkles. Intrigued by the possibilities, the Carruthers subsequently injected a small amount of BoNT-A between the eyebrows of their assistant, Cathy Bickerton Swann, also now known as “patient zero” and awaited the results.

Seventeen additional patients followed, aged 34-51, who collectively, would become part of the first report on the efficacy of BoNT-A for cosmetic use – for the treatment of glabellar frown lines – published in 1992.

Between 1992 and 1997, the popularity of off-label use of BoNT-A grew so rapidly that Allergan’s supply temporarily ran out. By 2002, safety and efficacy profiles of use in medical conditions such as strabismus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia, cerebral palsy, poststroke spasticity, hyperhidrosis, headache, and back pain had been well-established, facilitating the comfort and use for cosmetic purposes.

By 2002, open-label studies of more than 800 patients confirmed the efficacy and safety of BoNT for the treatment of dynamic facial rhytids. And in April 2002, the FDA granted approval of BoNT for the nonsurgical reduction of glabellar rhytids. The rest, some would say, is history. On this 20th-year anniversary of the approval of botulinum toxin for cosmetic use, special recognition is given here for the physicians and scientists who were astute enough to make this discovery, as botulinum toxin use remains one of the most popular and effective nonsurgical cosmetic procedures today.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley disclosed that she has been a clinical investigator and consultant for Botox manufacturer Allergan in the past, and manufacturers of other brands of botulinum toxins available for cosmetic use; Dysport (Galderma), Xeomin (Merz), and Jeuveau (Evolus). Dr. Talakoub had no disclosures.

Reference

“Botulinum Toxin: Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology Series 3rd Edition” (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013)

The timeline of botulinum toxin discovery began with deadly outbreaks related to contaminated food across Europe in the late 1700s, the largest of which occurred in 1793 in Wildebrad, in southern Germany. In 1811, “prussic acid” was named as the culprit in what was referred to as sausage poisoning. Between 1817 and 1822, German physician Justinus Kerner noted that the active substance interrupted signals from motor nerves to muscles, but spared sensory and cognitive abilities, accurately describing botulism. He hypothesized that this substance could possibly be used as treatment for medical conditions when ingested orally. It wasn’t until 1895 that microbiologist Emile Pierre Van Ermengem, a professor of bacteriology in Belgium, identified the bacterium responsible as Bacillus botulinus, later renamed C. botulinum.

In 1905, it was discovered that C. botulinum produced a substance that affected neurotransmitter function, and between 1895 and 1915, seven toxin serotypes were recognized. In 1928, Herman Sommer, PhD, at the Hooper Foundation, at the University of California, San Francisco, isolated the most potent serotype: botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A).

In 1946, Carl Lamanna and James Duff developed concentration and crystallization techniques that were subsequently used by Edward Schantz, PhD, at Fort Detrick, Md., for a possible biologic weapon. In 1972, Dr. Schantz took his research to the University of Wisconsin, where he produced a large batch of BoNT-A that remained in clinical use until December 1997.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an ophthalmologist in San Francisco, Alan Scott, MD, began animal studies with BoNT-A supplied by Dr. Schantz, as a possible treatment for strabismus, publishing his first report of BoNT-A in primates in 1973. In 1978, the Food and Drug Administration granted approval to begin testing small amounts of the toxin in human volunteers. In 1980, a landmark paper was published demonstrating that BoNT-A corrects gaze misalignment in humans. By 1989, it was approved as Oculinum by the FDA for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm.

Keen clinical observation and a serendipitous discovery led to botulinum toxin’s first uses for cosmetic purposes. In the mid-1980s, Jean Carruthers, MD, an ophthalmologist in Vancouver, noted an unexpected concomitant improvement of glabellar rhytids in a patient treated with BoNT for blepharospasm. The result of the treatment was a more serene, untroubled expression. Dr. Carruthers discussed the observation with her dermatologist spouse, Alastair Carruthers, MD, who was attempting to use soft tissue–augmenting agents available at the time to soften forehead wrinkles. Intrigued by the possibilities, the Carruthers subsequently injected a small amount of BoNT-A between the eyebrows of their assistant, Cathy Bickerton Swann, also now known as “patient zero” and awaited the results.

Seventeen additional patients followed, aged 34-51, who collectively, would become part of the first report on the efficacy of BoNT-A for cosmetic use – for the treatment of glabellar frown lines – published in 1992.

Between 1992 and 1997, the popularity of off-label use of BoNT-A grew so rapidly that Allergan’s supply temporarily ran out. By 2002, safety and efficacy profiles of use in medical conditions such as strabismus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, cervical dystonia, cerebral palsy, poststroke spasticity, hyperhidrosis, headache, and back pain had been well-established, facilitating the comfort and use for cosmetic purposes.

By 2002, open-label studies of more than 800 patients confirmed the efficacy and safety of BoNT for the treatment of dynamic facial rhytids. And in April 2002, the FDA granted approval of BoNT for the nonsurgical reduction of glabellar rhytids. The rest, some would say, is history. On this 20th-year anniversary of the approval of botulinum toxin for cosmetic use, special recognition is given here for the physicians and scientists who were astute enough to make this discovery, as botulinum toxin use remains one of the most popular and effective nonsurgical cosmetic procedures today.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley disclosed that she has been a clinical investigator and consultant for Botox manufacturer Allergan in the past, and manufacturers of other brands of botulinum toxins available for cosmetic use; Dysport (Galderma), Xeomin (Merz), and Jeuveau (Evolus). Dr. Talakoub had no disclosures.

Reference

“Botulinum Toxin: Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology Series 3rd Edition” (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013)

Climate change, medical education, and dermatology

The recent article on including the impact of climate on health in medical education programs shines an important light on the challenge – and urgent need – of integrating climate change training into medical education. These nascent efforts are just getting underway across the country, with some programs – notably Harvard’s C-CHANGE (Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment) program, mentioned in the article, and others, such as the University of Colorado’s Climate Medicine diploma course – leading the way. A number of publications, such as the editorial titled “A planetary health curriculum for medicine” published in 2021 in the BMJ, offer a roadmap to do so.

Medical schools, residency programs, and other medical specialty programs – including those for advanced practice providers, dentists, nurses, and more – should be incorporating climate change and its myriad of health impacts into their training pathways. The medical student group, Medical Students for a Sustainable Future, has put forth a planetary health report card that evaluates training programs on the strength of their focus on the intersections between climate and health.

While the article did not specifically focus on dermatology, these impacts are true in our field as well. The article notes that “at least one medical journal has recently ramped up its efforts to educate physicians on the links between health issues and climate change.” Notably in dermatology, the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology devoted an entire 124-page themed issue to climate change and dermatology in January, 2021, while JAMA Dermatology editor Kanade Shinkai, MD, PhD, called out climate change as one of the journal’s priorities in her annual editorial, stating, “Another priority for the journal is to better understand the effect of climate change on human health, specifically skin disease.”

The impacts of climate change in dermatology range from heat-related illness (a major cause of climate-associated mortality, with the skin serving as an essential thermoregulatory organ) to changing patterns of vector-borne illnesses to pollution and wildfire smoke flaring inflammatory skin diseases, to an increase in skin cancer, and more. While incorporation of health issues relating to climate change is important at a medical school level, it is also critical at the residency training – and board exam/certification – level as well.

Beyond the importance of building climate education into undergraduate and graduate medical education, it is also important that practicing physicians, post-residency training, remain up to date and keep abreast of changing patterns of disease in our rapidly changing climate. Lyme disease now occurs in Canada – and both earlier and later in the year even in places that are geographically used to seeing it. Early recognition is essential, but unprepared physicians may miss the early erythema migrans rash, and patients may suffer more severe sequelae as a result.

Finally, it’s important that medical organizations are aware of not just the health implications of climate change, but also potential policy impacts. Health care is a major emitter of CO2, and assistant secretary for health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Admiral Rachel L. Levine, MD, with the National Academy of Medicine, has appropriately pledged to reduce health care carbon emissions as part of the necessary steps that we must all take to avert the worst impacts of a warming world. The field of medicine and individual providers should educate themselves and actively work toward sustainability in health care, to improve the health of their patients, populations, and future generations.

Dr. Rosenbach is associate professor of dermatology and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and is the founder and cochair of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues. Dr. Rosenbach is speaking on behalf of himself and not the AAD.

The recent article on including the impact of climate on health in medical education programs shines an important light on the challenge – and urgent need – of integrating climate change training into medical education. These nascent efforts are just getting underway across the country, with some programs – notably Harvard’s C-CHANGE (Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment) program, mentioned in the article, and others, such as the University of Colorado’s Climate Medicine diploma course – leading the way. A number of publications, such as the editorial titled “A planetary health curriculum for medicine” published in 2021 in the BMJ, offer a roadmap to do so.

Medical schools, residency programs, and other medical specialty programs – including those for advanced practice providers, dentists, nurses, and more – should be incorporating climate change and its myriad of health impacts into their training pathways. The medical student group, Medical Students for a Sustainable Future, has put forth a planetary health report card that evaluates training programs on the strength of their focus on the intersections between climate and health.

While the article did not specifically focus on dermatology, these impacts are true in our field as well. The article notes that “at least one medical journal has recently ramped up its efforts to educate physicians on the links between health issues and climate change.” Notably in dermatology, the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology devoted an entire 124-page themed issue to climate change and dermatology in January, 2021, while JAMA Dermatology editor Kanade Shinkai, MD, PhD, called out climate change as one of the journal’s priorities in her annual editorial, stating, “Another priority for the journal is to better understand the effect of climate change on human health, specifically skin disease.”

The impacts of climate change in dermatology range from heat-related illness (a major cause of climate-associated mortality, with the skin serving as an essential thermoregulatory organ) to changing patterns of vector-borne illnesses to pollution and wildfire smoke flaring inflammatory skin diseases, to an increase in skin cancer, and more. While incorporation of health issues relating to climate change is important at a medical school level, it is also critical at the residency training – and board exam/certification – level as well.

Beyond the importance of building climate education into undergraduate and graduate medical education, it is also important that practicing physicians, post-residency training, remain up to date and keep abreast of changing patterns of disease in our rapidly changing climate. Lyme disease now occurs in Canada – and both earlier and later in the year even in places that are geographically used to seeing it. Early recognition is essential, but unprepared physicians may miss the early erythema migrans rash, and patients may suffer more severe sequelae as a result.

Finally, it’s important that medical organizations are aware of not just the health implications of climate change, but also potential policy impacts. Health care is a major emitter of CO2, and assistant secretary for health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Admiral Rachel L. Levine, MD, with the National Academy of Medicine, has appropriately pledged to reduce health care carbon emissions as part of the necessary steps that we must all take to avert the worst impacts of a warming world. The field of medicine and individual providers should educate themselves and actively work toward sustainability in health care, to improve the health of their patients, populations, and future generations.

Dr. Rosenbach is associate professor of dermatology and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and is the founder and cochair of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues. Dr. Rosenbach is speaking on behalf of himself and not the AAD.