User login

Lost keys, missed appointments: The struggle of treating executive dysfunction

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Student loan forgiveness plans exclude physicians

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More practice merger options

The continuing than larger ones. While there are some smaller offices offering unique services that may be able to remain small, most small general practices will be forced to at least consider a larger alternative. Recently, I discussed one option – merging individual practices into a larger one – but others are available.

One alternate strategy is to form a cooperative group. If you look around your area of practice, you will likely find other small practices in similar situations that might be willing to collaborate with you for the purpose of pooling your billing and purchasing resources. This allows each participant to maintain independence, yet share office overhead expenses and employee salaries for mutual benefit. If that arrangement works, and remains satisfactory for all participants, you can consider expanding your sharing of expenditures, such as collective purchasing of supplies and equipment, and centralizing appointment scheduling. Such an arrangement might be particularly attractive to physicians in later stages of their careers who need to alleviate financial burdens but don’t wish to close up shop just yet.

After more time has passed, if everyone remains happy with the arrangement, an outright merger can be considered, allowing the group to negotiate higher insurance remunerations and even lower overhead costs. Obviously, projects of this size and scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

Another option is to join an independent practice association (IPA), if one is operating in your area. IPAs are physician-directed legal entities, formed to provide the same advantages enjoyed by large group practices while allowing individual members to remain independent. IPAs have greater purchasing power, allowing members to cut costs on medical and office supplies. They can also negotiate more favorable contracts with insurance companies and other payers.

Before joining such an organization, examine its legal status carefully. Some IPAs have been charged with antitrust violations because their member practices are, in reality, competitors. Make certain that any IPA you consider joining abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. Look carefully at its financial solvency as well, as IPAs have also been known to fail, leaving former members to pick up the tab.

An alternative to the IPA is the accountable care organization (ACO), a relatively new entity created as part of the Affordable Care Act. Like an IPA, an ACO’s basic purpose is to limit unnecessary spending; but ACOs are typically limited to Medicare and Medicaid recipients, and involve a larger network of doctors and hospitals sharing financial and medical responsibility for patient care. Criteria for limits on spending are established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

ACOs offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings. According to federal data, ACOs saved Medicare $4.1 billion in 2020). As of January 2022, 483 ACOs were participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. A similar entity designed for private-sector patients is the clinically integrated network (CIN), created by the Federal Trade Commission to serve the commercial or self-insured market, while ACOs treat Medicare and Medicaid patients. Like ACOs, the idea is to work together to improve care and reduce costs by sharing records and tracking data.

When joining any group, read the agreement carefully for any clauses that might infringe on your clinical judgment. In particular, be sure that there are no restrictions on patient treatment or physician referral options for your patients. You should also negotiate an escape clause, allowing you to opt out if you become unhappy with the arrangement.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous is significant, and many private practitioners are unwilling to pay it. In 2019, the American Medical Association reported that for the first time, there were fewer physician owners (45.9%) than employees (47.4%).

But as I have written many times, those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

The continuing than larger ones. While there are some smaller offices offering unique services that may be able to remain small, most small general practices will be forced to at least consider a larger alternative. Recently, I discussed one option – merging individual practices into a larger one – but others are available.

One alternate strategy is to form a cooperative group. If you look around your area of practice, you will likely find other small practices in similar situations that might be willing to collaborate with you for the purpose of pooling your billing and purchasing resources. This allows each participant to maintain independence, yet share office overhead expenses and employee salaries for mutual benefit. If that arrangement works, and remains satisfactory for all participants, you can consider expanding your sharing of expenditures, such as collective purchasing of supplies and equipment, and centralizing appointment scheduling. Such an arrangement might be particularly attractive to physicians in later stages of their careers who need to alleviate financial burdens but don’t wish to close up shop just yet.

After more time has passed, if everyone remains happy with the arrangement, an outright merger can be considered, allowing the group to negotiate higher insurance remunerations and even lower overhead costs. Obviously, projects of this size and scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

Another option is to join an independent practice association (IPA), if one is operating in your area. IPAs are physician-directed legal entities, formed to provide the same advantages enjoyed by large group practices while allowing individual members to remain independent. IPAs have greater purchasing power, allowing members to cut costs on medical and office supplies. They can also negotiate more favorable contracts with insurance companies and other payers.

Before joining such an organization, examine its legal status carefully. Some IPAs have been charged with antitrust violations because their member practices are, in reality, competitors. Make certain that any IPA you consider joining abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. Look carefully at its financial solvency as well, as IPAs have also been known to fail, leaving former members to pick up the tab.

An alternative to the IPA is the accountable care organization (ACO), a relatively new entity created as part of the Affordable Care Act. Like an IPA, an ACO’s basic purpose is to limit unnecessary spending; but ACOs are typically limited to Medicare and Medicaid recipients, and involve a larger network of doctors and hospitals sharing financial and medical responsibility for patient care. Criteria for limits on spending are established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

ACOs offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings. According to federal data, ACOs saved Medicare $4.1 billion in 2020). As of January 2022, 483 ACOs were participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. A similar entity designed for private-sector patients is the clinically integrated network (CIN), created by the Federal Trade Commission to serve the commercial or self-insured market, while ACOs treat Medicare and Medicaid patients. Like ACOs, the idea is to work together to improve care and reduce costs by sharing records and tracking data.

When joining any group, read the agreement carefully for any clauses that might infringe on your clinical judgment. In particular, be sure that there are no restrictions on patient treatment or physician referral options for your patients. You should also negotiate an escape clause, allowing you to opt out if you become unhappy with the arrangement.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous is significant, and many private practitioners are unwilling to pay it. In 2019, the American Medical Association reported that for the first time, there were fewer physician owners (45.9%) than employees (47.4%).

But as I have written many times, those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

The continuing than larger ones. While there are some smaller offices offering unique services that may be able to remain small, most small general practices will be forced to at least consider a larger alternative. Recently, I discussed one option – merging individual practices into a larger one – but others are available.

One alternate strategy is to form a cooperative group. If you look around your area of practice, you will likely find other small practices in similar situations that might be willing to collaborate with you for the purpose of pooling your billing and purchasing resources. This allows each participant to maintain independence, yet share office overhead expenses and employee salaries for mutual benefit. If that arrangement works, and remains satisfactory for all participants, you can consider expanding your sharing of expenditures, such as collective purchasing of supplies and equipment, and centralizing appointment scheduling. Such an arrangement might be particularly attractive to physicians in later stages of their careers who need to alleviate financial burdens but don’t wish to close up shop just yet.

After more time has passed, if everyone remains happy with the arrangement, an outright merger can be considered, allowing the group to negotiate higher insurance remunerations and even lower overhead costs. Obviously, projects of this size and scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

Another option is to join an independent practice association (IPA), if one is operating in your area. IPAs are physician-directed legal entities, formed to provide the same advantages enjoyed by large group practices while allowing individual members to remain independent. IPAs have greater purchasing power, allowing members to cut costs on medical and office supplies. They can also negotiate more favorable contracts with insurance companies and other payers.

Before joining such an organization, examine its legal status carefully. Some IPAs have been charged with antitrust violations because their member practices are, in reality, competitors. Make certain that any IPA you consider joining abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. Look carefully at its financial solvency as well, as IPAs have also been known to fail, leaving former members to pick up the tab.

An alternative to the IPA is the accountable care organization (ACO), a relatively new entity created as part of the Affordable Care Act. Like an IPA, an ACO’s basic purpose is to limit unnecessary spending; but ACOs are typically limited to Medicare and Medicaid recipients, and involve a larger network of doctors and hospitals sharing financial and medical responsibility for patient care. Criteria for limits on spending are established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

ACOs offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings. According to federal data, ACOs saved Medicare $4.1 billion in 2020). As of January 2022, 483 ACOs were participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. A similar entity designed for private-sector patients is the clinically integrated network (CIN), created by the Federal Trade Commission to serve the commercial or self-insured market, while ACOs treat Medicare and Medicaid patients. Like ACOs, the idea is to work together to improve care and reduce costs by sharing records and tracking data.

When joining any group, read the agreement carefully for any clauses that might infringe on your clinical judgment. In particular, be sure that there are no restrictions on patient treatment or physician referral options for your patients. You should also negotiate an escape clause, allowing you to opt out if you become unhappy with the arrangement.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous is significant, and many private practitioners are unwilling to pay it. In 2019, the American Medical Association reported that for the first time, there were fewer physician owners (45.9%) than employees (47.4%).

But as I have written many times, those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Measles outbreaks: Protecting your patients during international travel

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

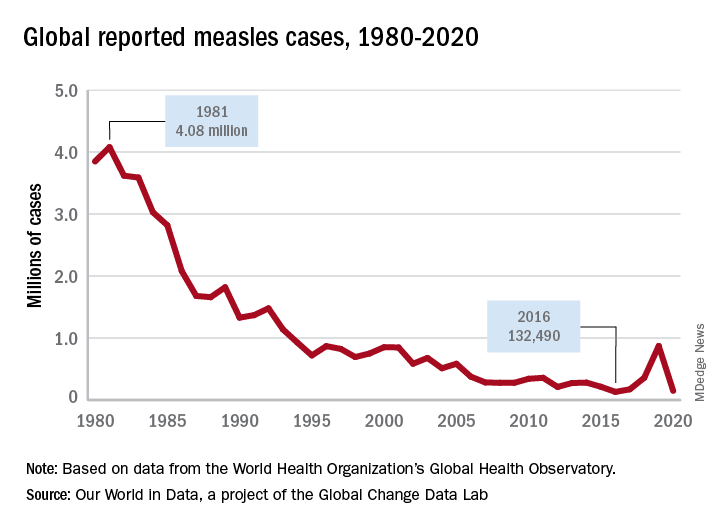

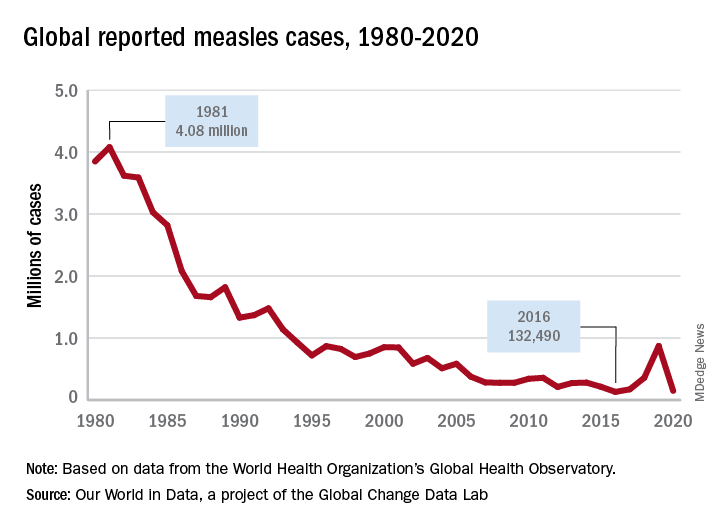

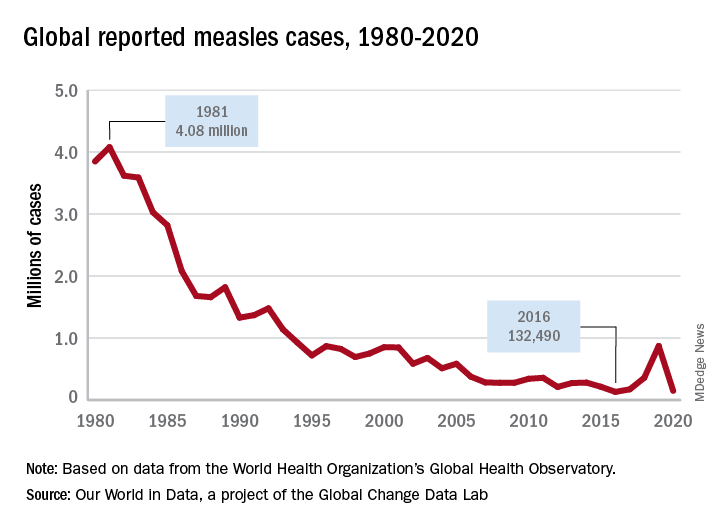

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

The U.S. immunization program is one of the best public health success stories. Physicians who provide care for children are familiar with the routine childhood immunization schedule and administer a measles-containing vaccine at age-appropriate times. Thanks to its rigorous implementation and acceptance, endemic measles (absence of continuous virus transmission for > 1 year) was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Loss of this status was in jeopardy in 2019 when 22 measles outbreaks occurred in 17 states (7 were multistate outbreaks). That year, 1,163 cases were reported.1 Most cases occurred in unvaccinated persons (89%) and 81 cases were imported of which 54 were in U.S. citizens returning from international travel. All outbreaks were linked to travel. Fortunately, the outbreaks were controlled prior to the elimination deadline, or the United States would have lost its measles elimination status. Restrictions on travel because of COVID-19 have relaxed significantly since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, resulting in increased regional and international travel. Multiple countries, including the United States noted a decline in routine immunizations rates during the last 2 years. Recent U.S. data for the 2020-2021 school year indicates that MMR immunizations rates (two doses) for kindergarteners declined to 93.9% (range 78.9% to > 98.9%), while the overall percentage of those students with an exemption remained low at 2.2%. Vaccine coverage greater than 95% was reported in only 16 states. Coverage of less than 90% was reported in seven states and the District of Columbia (Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin).2 Vaccine coverage should be 95% or higher to maintain herd immunity and control outbreaks.

Why is measles prevention so important? Many physicians practicing in the United States today have never seen a case or know its potential complications. I saw my first case as a resident in an immigrant child. It took our training director to point out the subtle signs and symptoms. It was the first time I saw Kolpik spots. Measles is transmitted person to person via large respiratory droplets and less often by airborne spread. It is highly contagious for susceptible individuals with an attack rate of 90%. In this case, a medical student on the team developed symptoms about 10 days later. Six years would pass before I diagnosed my next case of measles. An HIV patient acquired it after close contact with someone who was in the prodromal stage. He presented with the 3 C’s: Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, in addition to fever and an erythematous rash. He did not recover from complications of the disease.

Prior to the routine administration of a measles vaccine, 3-4 million cases with almost 500 deaths occurred annually in the United States. Worldwide, 35 million cases and more than 6 million deaths occurred each year. Here, most patients recover completely; however, complications including otitis media, pneumonia, croup, and encephalitis can develop. Complications commonly occur in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Groups with the highest fatality rates include children aged less than 5 years, immunocompromised persons, and pregnant women. Worldwide, fatality rates are dependent on the patients underlying nutritional and health status in addition to the quality of health care available.3

Measles vaccine was licensed in 1963 and cases began to decline (Figure 1). There was a resurgence in 1989 but it was not limited to the United States. The cause of the U.S. resurgence was multifactorial: Widespread viral transmission among unvaccinated preschool-age children residing in inner cities, outbreaks in vaccinated school-age children, outbreaks in students and personnel on college campuses, and primary vaccine failure (2%-5% of recipients failed to have an adequate response). In 1989, to help prevent future outbreaks, the United States recommended a two-dose schedule for measles and in 1993, the Vaccines for Children Program, a federally funded program, was established to improve access to vaccines for all children.

What is going on internationally?

Figure 2 lists the top 10 countries with current measles outbreaks.

Most countries on the list may not be typical travel destinations for tourists; however, they are common destinations for individuals visiting friends and relatives after immigrating to the United States. In contrast to the United States, most countries with limited resources and infrastructure have mass-vaccination campaigns to ensure vaccine administration to large segments of the population. They too have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By report, at least 41 countries delayed implementation of their measles campaign in 2020 and 2021, thus, leading to the potential for even larger outbreaks.4

Progress toward the global elimination of measles is evidenced by the following: All 194 countries now include one dose of measles in their routine schedules; between 2000 and 2019 coverage of one dose of measles increased from 72% to 85% and countries with more than 90% coverage increased from 45% to 63%. Finally, the number of countries offering two doses of measles increased from 50% to 91% and vaccine coverage increased from 18% to 71% over the same time period.3

What can you do for your patients and their parents before they travel abroad?

- Inform all staff that the MMR vaccine can be administered to children as young as 6 months and at times other than those listed on the routine immunization schedule. This will help avoid parents seeking vaccine being denied an appointment.

- Children 6-11 months need 1 dose of MMR. Two additional doses will still need to be administered at the routine time.

- Children 12 months or older need 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart.

- If yellow fever vaccine is needed, coordinate administration with a travel medicine clinic since both are live vaccines and must be given on the same day.

- Any person born after 1956 should have 2 doses of MMR at least 4 weeks apart if they have no evidence of immunity.

- Encourage parents to always inform you and your staff of any international travel plans.

Moving forward, remember this increased global activity and the presence of inadequately vaccinated individuals/communities keeps the United States at continued risk for measles outbreaks. The source of the next outbreak may only be one plane ride away.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated 6/29/22.

References

1. Patel M et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11; 68(40):893-6.

2. Seither R et al. MMWR. 2022 Apr 22;71(16):561-8.

3. Gastañaduy PA et al. J Infect Dis. 2021 Sep 30;224(12 Suppl 2):S420-8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa793.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). http://www.CDC.gov/Measles.

A 64-year-old woman presents with a history of asymptomatic erythematous grouped papules on the right breast

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”