User login

Treating PTSD: A review of 8 studies

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. The lifetime prevalence among American adults is 6.8%.1 Management of PTSD includes treating distressing symptoms, reducing avoidant behaviors, treating comorbid conditions (eg, depression, substance use disorders, or mood dysregulation), and improving adaptive functioning, which includes restoring a psychological sense of safety and trust. PTSD can be treated using evidence-based psychotherapies, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both modalities. For adults, evidence-based treatment guidelines recommend the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, cognitive therapy, and prolonged exposure therapy.2 These guidelines also recommend (with some reservations) the use of brief eclectic psychotherapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and narrative exposure therapy.2 Although the evidence base for the use of medications is not as strong as that for the psychotherapies listed above, the guidelines recommend the use of fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine.2

Currently available treatments for PTSD have significant limitations. For example, trauma-focused psychotherapies can have significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, or treatment dropout.3,4 Additionally, such therapies are not widely accessible. As for pharmacotherapy, very few available options are supported by evidence, and the efficacy of these options is limited, as shown by the reports that only 60% of patients with PTSD show a response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and only 20% to 30% achieve complete remission.5 Additionally, it may take months for patients to achieve an acceptable level of improvement with medications. As a result, a substantial proportion of patients who seek treatment continue to remain symptomatic, with impaired levels of functioning. This lack of progress in PTSD treatment has been labeled as a national crisis, calling for an urgent need to find effective pharmacologic treatments for PTSD.6

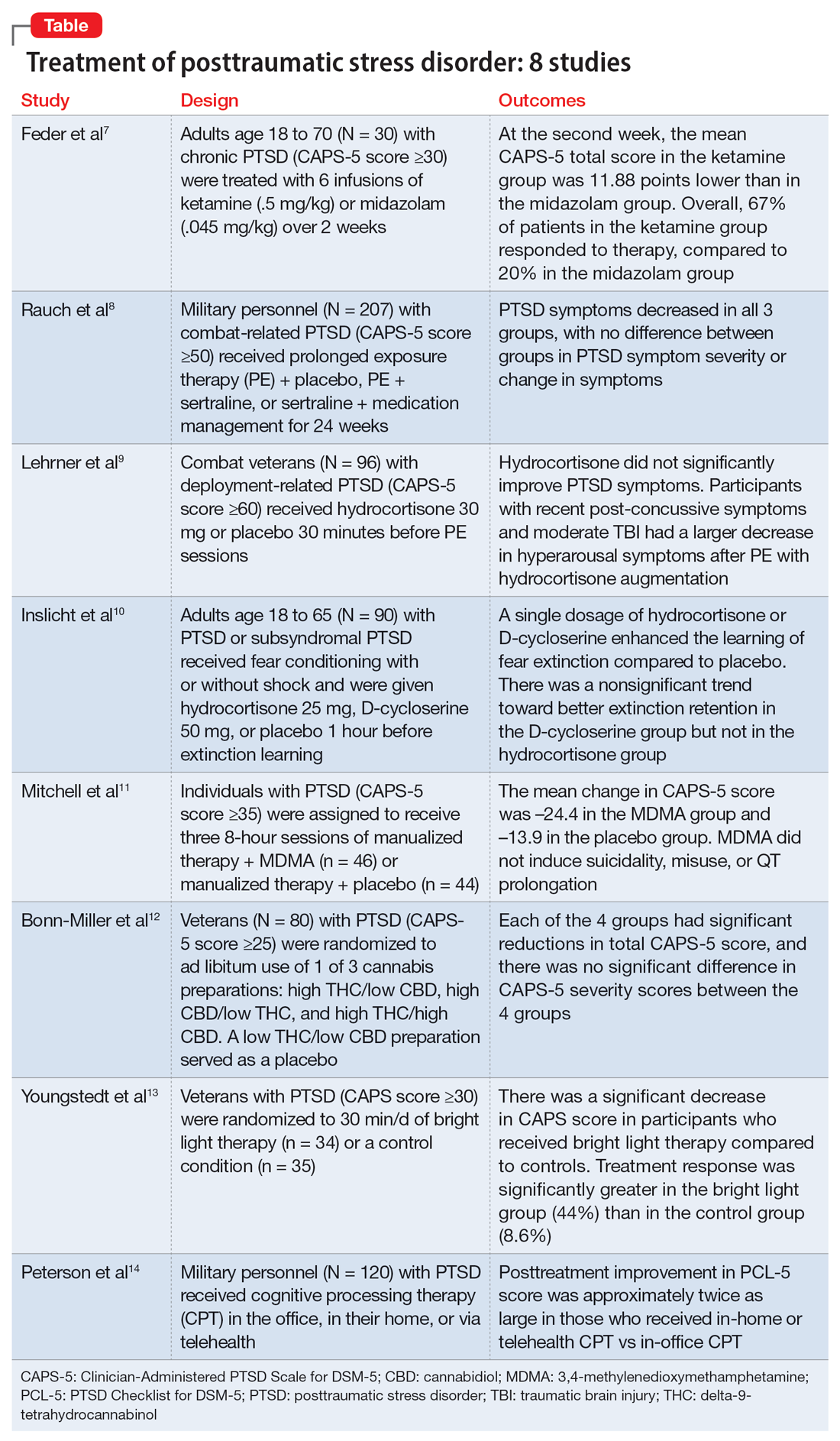

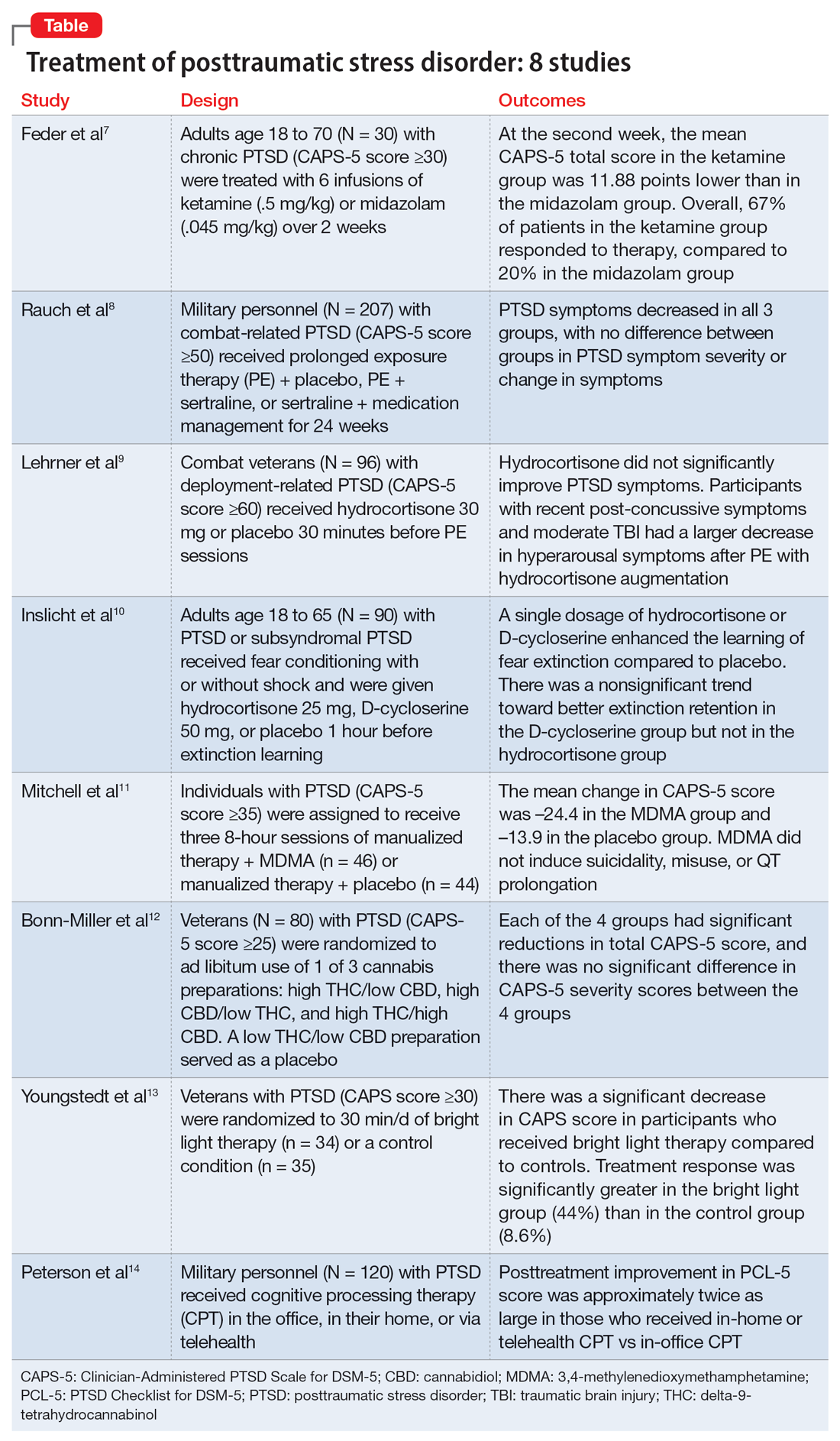

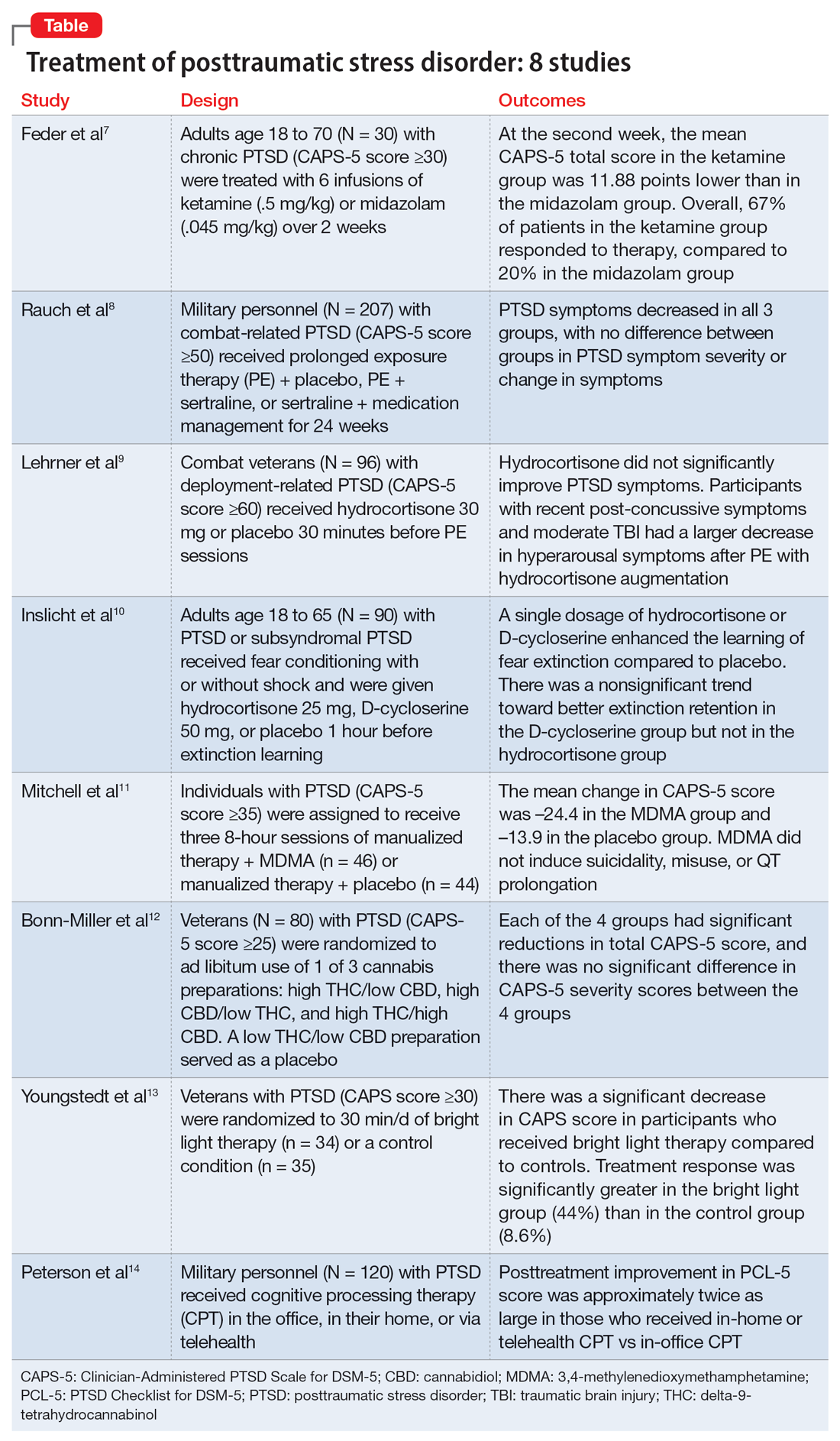

In this article, we review 8 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of treatments for PTSD published within the last 5 years (Table7-14).

1. Feder A, Costi S, Rutter SB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(2):193-202

Feder et al had previously found a significant and quick decrease in PTSD symptoms after a single dose of IV ketamine had. This is the first RCT to examine the effectiveness and safety of repeated IV ketamine infusions for the treatment of persistent PTSD.7

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel-arm controlled trial treated 30 individuals with chronic PTSD with 6 infusions of either ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) over 2 consecutive weeks.

- Participants were individuals age 18 to 70 with a primary diagnosis of chronic PTSD according to the DSM-5 criteria and determined by The Structure Clinical Interview for DSM-5, with a score ≥30 on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

- Any severe or unstable medical condition, active suicidal or homicidal ideation, lifetime history of psychotic or bipolar disorder, current anorexia nervosa or bulimia, alcohol or substance use disorder within 3 months of screening, history of recreational ketamine or phencyclidine use on more than 1 occasion or any use in the previous 2 years, and ongoing treatment with a long-acting benzodiazepine or opioid medication were all considered exclusion criteria. Individuals who took short-acting benzodiazepines had their morning doses held on infusion days. Marijuana or cannabis derivatives were allowed.

- The primary outcome measure was a change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS-5. This was administered before the first infusion and weekly thereafter. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised, the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and adverse effect measurements were used as secondary outcome measures.

- Treatment response was defined as ≥30% symptom improvement 2 weeks after the first infusion as assessed with CAPS-5.

- Individuals who responded to treatment were followed naturalistically weekly for up to 4 weeks and then monthly until loss of responder status, or up to 6 months if there was no loss of response.

Outcomes

- At the second week, the mean CAPS-5 total score in the ketamine group was 11.88 points (SE = 3.96) lower than in the midazolam group (d = 1.13; 95% CI, 0.36 to 1.91).

- In the ketamine group, 67% of patients responded to therapy, compared to 20% in the midazolam group.

- Following the 2-week course of infusions, the median period until loss of response among ketamine responders was 27.5 days.

- Ketamine infusions showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated ketamine infusions are effective in reducing symptom severity in individuals with chronic PTSD.

- Limitations to this study include the exclusion of individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder, current alcohol or substance use disorder, or suicidal ideations, the small sample size, and a higher rate of transient dissociative symptoms in the ketamine group.

- Future studies could evaluate the efficacy of repeated ketamine infusions in individuals with treatment-resistant PTSD. Also, further studies are required to assess the efficacy of novel interventions to prevent relapse and evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of periodic IV ketamine use as maintenance.

- Additional research might determine whether pairing psychotherapy with ketamine administration can lessen the risk of recurrence for PTSD patients after stopping ketamine infusions.

2. Rauch SAM, Kim HM, Powell C, et al. Efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, sertraline hydrochloride, and their combination among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):117-126

Clinical practice recommendations for PTSD have identified trauma-focused psychotherapies and SSRIs as very effective treatments. The few studies that have compared trauma-focused psychotherapy to SSRIs or to a combination of treatments are not generalizable, have significant limitations, or are primarily concerned with refractory disorders or augmentation techniques. This study evaluated the efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy (PE) plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management in the treatment of PTSD.8

Study design

- This randomized, 4-site, 24-week clinical trial divided participants into 3 subgroups: PE plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management.

- Participants were veterans or service members of the Iraq and/or Afghanistan wars with combat-related PTSD and significant impairment as indicated by a CAPS score ≥50 for at least 3 months. The DSM-IV-TR version of CAPS was used because the DSM-5 version was not available at the time of the study.

- Individuals who had a current, imminent risk of suicide; active psychosis; alcohol or substance dependence in the past 8 weeks; inability to attend weekly appointments for the treatment period; prior intolerance to or failure of an adequate trial of PE or sertraline; medical illness likely to result in hospitalization or contraindication to study treatment; serious cognitive impairment; mild traumatic brain injury; or concurrent use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, prazosin, or sleep agents were excluded.

- Participants completed up to thirteen 90-minute sessions of PE.

- The sertraline dosage was titrated during a 10-week period and continued until Week 24. Dosages were adjusted between 50 and 200 mg/d, with the last dose increase at Week 10.

- The primary outcome measure was symptom severity of PTSD in the past month as determined by CAPS score at Week 24.

- The secondary outcome was self-reported symptoms of PTSD (PTSD checklist [PCL] Specific Stressor Version), clinically meaningful change (reduction of ≥20 points or score ≤35 on CAPS), response (reduction of ≥50% in CAPS score), and remission (CAPS score ≤35).

Outcomes

- At Week 24, 149 participants completed the study; 207 were included in the intent-to-treat analysis.

- PTSD symptoms significantly decreased over 24 weeks, according to a modified intent-to-treat analysis utilizing a mixed model of repeated measurements; nevertheless, slopes were similar across therapy groups.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Although the severity of PTSD symptoms decreased in all 3 subgroups, there was no difference in PTSD symptom severity or change in symptoms at Week 24 among all 3 subgroups.

- The main limitation of this study was the inclusion of only combat veterans.

- Further research should focus on enhancing treatment retention and should include administering sustained exposure therapy at brief intervals.

3. Lehrner A, Hildebrandt T, Bierer LM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone augmentation of prolonged exposure for PTSD in US combat veterans. Behav Res Ther. 2021;144:103924

First-line therapy for PTSD includes cognitive-behavioral therapies such as PE. However, because many people still have major adverse effects after receiving medication, improving treatment efficacy is a concern. Glucocorticoids promote extinction learning, and alterations in glucocorticoid signaling pathways have been associated with PTSD. Lehrner et al previously showed that adding hydrocortisone (HCORT) to PE therapy increased patients’ glucocorticoid sensitivity at baseline, improved treatment retention, and resulted in greater treatment improvements. This study evaluated HCORT in conjunction with PE for combat veterans with PTSD following deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan.9

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial administered HCORT 30 mg oral or placebo to 96 combat veterans 30 minutes before PE sessions.

- Participants were veterans previously deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq with deployment-related PTSD >6 months with a minimum CAPS score of 60. They were unmedicated or on a stable psychotropic regimen for ≥4 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included a lifetime history of a primary psychotic disorder (bipolar I disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder), medical or mental health condition other than PTSD that required immediate clinical attention, moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), substance abuse or dependence within the past 3 months, medical illness that contraindicated ingestion of hydrocortisone, acute suicide risk, and pregnancy or intent to become pregnant.

- The primary outcome measures included PTSD severity as assessed with CAPS.

- Secondary outcome measures included self-reported PTSD symptoms as assessed with the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) and depression as assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI). These scales were administered pretreatment, posttreatment, and at 3-months follow-up.

Outcomes

- Out of 96 veterans enrolled, 60 were randomized and 52 completed the treatment.

- Five participants were considered recovered early and completed <12 sessions.

- Of those who completed treatment, 50 completed the 1-week posttreatment evaluations and 49 completed the 3-month follow-up evaluation.

- There was no difference in the proportion of dropouts (13.33%) across the conditions.

- HCORT failed to significantly improve either secondary outcomes or PTSD symptoms, according to an intent-to-treat analysis.

- However, exploratory analyses revealed that veterans with recent post-concussive symptoms and moderate TBI exposure saw a larger decrease in hyperarousal symptoms after PE therapy with HCORT augmentation.

- The reduction in avoidance symptoms with HCORT augmentation was also larger in veterans with higher baseline glucocorticoid sensitivity.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- HCORT does not improve PTSD symptoms as assessed with the CAPS and PDS, or depression as assessed with the BDI.

- The main limitation of this study is generalizability.

- Further studies are needed to determine whether PE with HCORT could benefit veterans with indicators of enhanced glucocorticoid sensitivity, mild TBI, or postconcussive syndrome.

4. Inslicht SS, Niles AN, Metzler TJ, et al. Randomized controlled experimental study of hydrocortisone and D-cycloserine effects on fear extinction in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(11):1945-1952

PE, one of the most well-researched therapies for PTSD, is based on fear extinction. Exploring pharmacotherapies that improve fear extinction learning and their potential as supplements to PE is gaining increased attention. Such pharmacotherapies aim to improve the clinical impact of PE on the extent and persistence of symptom reduction. This study evaluated the effects of HCORT and D-cycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, on the learning and consolidation of fear extinction in patients with PTSD.10

Study design

- This double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-group experimental design evaluated 90 individuals with PTSD who underwent fear conditioning with stimuli that was paired (CS+) or unpaired (CS−) with shock.

- Participants were veterans and civilians age 18 to 65 recruited from VA outpatient and community clinics and internet advertisements who met the criteria for PTSD or subsyndromal PTSD (according to DSM-IV criteria) for at least 3 months.

- Exclusion criteria included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance abuse or dependence, alcohol dependence, previous moderate or severe head injury, seizure or neurological disorder, current infectious illness, systemic illness affecting CNS function, or other conditions known to affect psychophysiological responses. Excluded medications were antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, alpha- and beta-adrenergics, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, and steroids.

- Extinction learning took place 72 hours after extinction, and extinction retention was evaluated 1 week later. Placebo, HCORT 25 mg, or DCS 50 mg was given 1 hour before extinction learning.

- Clinical measures included PTSD diagnosis and symptom levels as determined by interview using CAPS and skin conduction response.

Outcomes

- The mean shock level, mean pre-stimulus skin conductance level (SCL) during habituation, and mean SC orienting response during the habituation phase did not differ between groups and were not associated with differential fear conditioning. Therefore, variations in shock level preference, resting SCL, or SC orienting response magnitude are unlikely to account for differences between groups during extinction learning and retention.

- During extinction learning, the DCS and HCORT groups showed a reduced differential CS+/CS− skin conductance response (SCR) compared to placebo.

- One week later, during the retention testing, there was a nonsignificant trend toward a smaller differential CS+/CS− SCR in the DCS group compared to placebo. HCORT and DCS administered as a single dosage facilitated fear extinction learning in individuals with PTSD symptoms.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- In traumatized people with PTSD symptoms, a single dosage of HCORT or DCS enhanced the learning of fear extinction compared to placebo. A nonsignificant trend toward better extinction retention in the DCS group but not the HCORT group was also visible.

- These results imply that glucocorticoids and NMDA agonists have the potential to promote extinction learning in PTSD.

- Limitations include a lack of measures of glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity or FKBP5.

- Further studies could evaluate these findings with the addition of blood biomarker measures such as glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity or FKBP5.

5. Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

Poor PTSD treatment results are associated with numerous comorbid conditions, such as dissociation, depression, alcohol and substance use disorders, childhood trauma, and suicidal ideation, which frequently leads to treatment resistance. Therefore, it is crucial to find a treatment that works for individuals with PTSD who also have comorbid conditions. In animal models, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), an empathogen/entactogen with stimulant properties, has been shown to enhance fear memory extinction and modulate fear memory reconsolidation. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of MDMA-assisted therapy for treating patients with severe PTSD, including those with common comorbidities.11

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-site, phase 3 clinical trial evaluated individuals randomized to receive manualized therapy with MDMA or with placebo, combined with 3 preparatory and 9 integrative therapy sessions.

- Participants were 90 individuals (46 randomized to MDMA and 44 to placebo) with PTSD with a symptom duration ≥6 months and CAPS-5 total severity score ≥35 at baseline.

- Exclusion criteria included primary psychotic disorder, bipolar I disorder, eating disorders with active purging, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, dissociative identity disorder, personality disorders, current alcohol and substance use disorders, lactation or pregnancy, and any condition that could make receiving a sympathomimetic medication dangerous due to hypertension or tachycardia, including uncontrolled hypertension, history of arrhythmia, or marked baseline prolongation of QT and/or QTc interval.

- Three 8-hour experimental sessions of either therapy with MDMA assistance or therapy with a placebo control were given during the treatment period, and they were spaced approximately 4 weeks apart.

- In each session, participants received placebo or a single divided dose of MDMA 80 to 180 mg.

- At baseline and 2 months after the last experimental sessions, PTSD symptoms were measured with CAPS-5, and functional impairment was measured with Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS).

- The primary outcome measure was CAPS-5 total severity score at 18 weeks compared to baseline for MDMA-assisted therapy vs placebo-assisted therapy.

- The secondary outcome measure was clinician-rated functional impairment using the mean difference in SDS total scores from baseline to 18 weeks for MDMA-assisted therapy vs placebo-assisted therapy.

Outcomes

- MDMA was found to induce significant and robust attenuation in CAPS-5 score compared to placebo.

- The mean change in CAPS-5 score in completers was –24.4 in the MDMA group and –13.9 in the placebo group.

- MDMA significantly decreased the SDS total score.

- MDMA did not induce suicidality, misuse, or QT prolongation.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- MDMA-assisted therapy is significantly more effective than manualized therapy with placebo in treating patients with severe PTSD, and it is also safe and well-tolerated, even in individuals with comorbidities.

- No major safety issues were associated with MDMA-assisted treatment.

- MDMA-assisted therapy should be promptly assessed for clinical usage because it has the potential to significantly transform the way PTSD is treated.

- Limitations of this study include a smaller sample size (due to the COVID-19 pandemic); lack of ethnic and racial diversity; short duration; safety data were collected by site therapist, which limited the blinding; and the blinding of participants was difficult due to the subjective effects of MDMA, which could have resulted in expectation effects.

6. Bonn-Miller MO, Sisley S, Riggs P, et al. The short-term impact of 3 smoked cannabis preparations versus placebo on PTSD symptoms: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246990

Sertraline and paroxetine are the only FDA-approved medications for treating PTSD. Some evidence suggests cannabis may provide a therapeutic benefit for PTSD.15 This study examined the effects of 3 different preparations of cannabis for treating PTSD symptoms.12

Study design

- This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial used 3 active treatment groups of cannabis: high delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)/low cannabidiol (CBD), high CBD/low THC, and high THC/high CBD (THC+CBD). A low THC/low CBD preparation was used as a placebo. “High” content contained 9% to 15% concentration by weight of the respective cannabinoid, and “low” content contained <2% concentration by weight.

- Inclusion criteria included being a US military veteran, meeting DSM-5 PTSD criteria for ≥6 months, having moderate symptom severity (CAPS-5 score ≥25), abstaining from cannabis 2 weeks prior to study and agreeing not to use any non-study cannabis during the trial, and being stable on medications/therapy prior to the study.

- Exclusion criteria included women who were pregnant/nursing/child-bearing age and not taking an effective means of birth control; current/past serious mental illness, including psychotic and personality disorders; having a first-degree relative with a psychotic or bipolar disorder; having a high suicide risk based on Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; meeting DSM-5 criteria for moderate-severe cannabis use disorder; screening positive for illicit substances; or having significant medical disease.

- Participants in Stage 1 (n = 80) were randomized to 1 of the 3 active treatments or placebo for 3 weeks. After a 2-week washout, participants in Stage 2 (n = 74) were randomized to receive for 3 weeks 1 of the 3 active treatments they had not previously received.

- During each stage, participants had ad libitum use for a maximum of 1.8 g/d.

- The primary outcome was change in PTSD symptom severity by the end of Stage 1 as assessed with CAPS-5.

- Secondary outcomes included the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the general depression subscale and anxiety subscale from the self-report Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS), the Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning, and the Insomnia Severity Index.

Outcomes

- Six participants did not continue to Stage 2. Three participants did not finish Stage 2 due to adverse effects, and 7 did not complete outcome measurements. The overall attrition rate was 16.3%.

- There was no significant difference in total grams of smoked cannabis or placebo between the 4 treatment groups in Stage 1 at the end of 3 weeks. In Stage 2, there was a significant difference, with the THC+CBD group using more cannabis compared to the other 2 groups.

- Each of the 4 groups had significant reductions in total CAPS-5 scores at the end of Stage 1, and there was no significant difference in CAPS-5 severity scores between the 4 groups.

- In Stage 1, PCL-5 scores were not significantly different between treatment groups from baseline to the end of stage. There was a significant difference in Stage 2 between the high CBD and THC+CBD groups, with the combined group reporting greater improvement of symptoms.

- In Stage 2, the THC+CBD group reported greater reductions in pre/post IDAS social anxiety scores and IDAS general depression scores, and the high THC group reported greater reductions in pre/post IDAS social anxiety scores.

- In Stage 1, 37 of 60 participants in the active groups reported at least 1 adverse event, and 45 of the 74 Stage 2 participants reported at least 1 adverse event. The most common adverse events were cough, throat irritation, and anxiety. Participants in the Stage 1 high THC group had a significant increase in reported withdrawal symptoms after 1 week of stopping use.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- This first randomized, placebo-control trial of cannabis in US veterans did not show a significant difference among treatment groups, including placebo, on the primary outcome of CAPS-5 score. All 4 groups had significant reductions in symptom severity on CAPS-5 and showed good tolerability.

- Prior beliefs about the effects of cannabis may have played a role in the reduction of PTSD symptoms in the placebo group.

- Many participants (n =34) were positive for THC during the screening process, so previous cannabis use/chronicity of cannabis use may have contributed.

- One limitation was that participants assigned to the Stage 1 high THC group had Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test scores (which assesses cannabis use disorder risk) about 2 times greater than participants in other conditions.

- Another limitation was that total cannabis use was lower than expected, as participants in Stage 1 used 8.2 g to 14.6 g over 3 weeks, though they had access to up to 37.8 g.

- There was no placebo in Stage 2.

- Future studies should look at longer treatment periods with more participants.

7. Youngstedt SD, Kline CE, Reynolds AM, et al. Bright light treatment of combat-related PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. Milit Med. 2022;187(3-4):e435-e444

Bright light therapy is an inexpensive treatment approach that may affect serotonergic pathways.16 This study examined bright light therapy for reducing PTSD symptoms and examined if improvement of PTSD is related to a shift in circadian rhythm.13

Study design

- Veterans with combat-related PTSD had to have been stable on treatment for at least 8 weeks or to have not received any other PTSD treatments prior to the study.

- Participants were randomized to active treatment of 30 minutes daily 10,000 lux ultraviolet-filtered white light while sitting within 18 inches (n = 34) or a control condition of 30 minutes daily inactivated negative ion generator (n = 35) for 4 weeks.

- Inclusion criteria included a CAPS score ≥30.

- Exclusion criteria included high suicidality, high probability of alcohol/substance abuse in the past 3 months, bipolar disorder/mania/schizophrenia/psychosis, ophthalmologic deformities, shift work in past 2 months or travel across time zones in past 2 weeks, head trauma, high outdoor light exposure, history of winter depression, history of seizures, or myocardial infarction/stroke/cancer within 3 years.

- Primary outcomes were improvement on CAPS and Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (CGI-IM) score at Week 4.

- Wrist actigraphy recordings measured sleep.

- Other measurements included the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Hamilton atypical symptoms (HAM-AS), PCL-Military (PCL-M), Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), BDI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI Form Y-2), Beck Suicide Scale, and Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects questionnaire.

Outcomes

- There was a significant decrease in CAPS score in participants who received bright light therapy compared to controls. Treatment response (defined as ≥33% reduction in score) was significantly greater in the bright light (44%) vs control (8.6%) group. No participants achieved remission.

- There was a significant improvement in CGI-IM scores in the bright light group, but no significant difference in participants who were judged to improve “much” or “very much.”

- PCL-M scores did not change significantly between groups, although a significantly greater proportion of participants had treatment response in the bright light group (33%) vs control (6%).

- There were no significant changes in HAM-D, HAM-AS, STAI, BDI, actigraphic estimates of sleep, or PSQI scores.

- Bright light therapy resulted in phase advancement while control treatment had phase delay.

- There were no significant differences in adverse effects.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Bright light therapy may be a treatment option or adjunct for combat-related PTSD as seen by improvement on CAPS and CGI scores, as well as a greater treatment response seen on CAPS and PCL-5 scores in the bright light group.

- There was no significant difference for other measures, including depression, anxiety, and sleep.

- Limitations include excluding patients with a wide variety of medical or psychiatric comorbidities, as well as limited long-term follow up data.

- Other limitations include not knowing the precise amount of time participants stayed in front of the light device and loss of some actigraphic data (data from only 49 of 69 participants).

8. Peterson AL, Mintz J, Moring JC, et al. In-office, in-home, and telehealth cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):41 doi:10.1186/s12888-022-03699-4

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT), a type of trauma-focused psychotherapy, is an effective treatment for PTSD in the military population.17,18 However, patients may not be able to or want to participate in such therapy due to barriers such as difficulty arranging transportation, being homebound due to injury, concerns about COVID-19, stigma, familial obligations, and job constraints. This study looked at if CPT delivered face-to-face at the patient’s home or via telehealth in home would be effective and increase accessibility.14

Study design

- Participants (n = 120) were active-duty military and veterans who met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. They were randomized to receive CPT in the office, in their home, or via telehealth. Participants could choose not to partake in 1 modality but were then randomized to 1 of the other 2.

- Exclusion criteria included suicide/homicide risk needing intervention, items/situations pertaining to danger (ie, aggressive pet or unsafe neighborhood), significant alcohol/substance use, active psychosis, and impaired cognitive functioning.

- The primary outcome measurement was change in PCL-5 and CAPS-5 score over 6 months. The BDI-II was used to assess depressive symptoms.

- Secondary outcomes included the Reliable Change Index (defined as “an improvement of 10 or more points that was sustained at all subsequent assessments”) on the PCL-5 and remission on the CAPS-5.

- CPT was delivered in 60-minute sessions twice a week for 6 weeks. Participants who did not have electronic resources were loaned a telehealth apparatus.

Outcomes

- Overall, 57% of participants opted out of 1 modality, which resulted in fewer participants being placed into the in-home arm (n = 32). Most participants chose not to do in-home treatments (54%), followed by in-office (29%), and telehealth (17%).

- There was a significant posttreatment improvement in PCL-5 scores in all treatment arms, with improvement greater with in-home (d = 2.1) and telehealth (d = 2.0) vs in-office (d=1.3). The in-home and telehealth scores were significantly improved compared to in-office, and the difference between in-home and telehealth PCL-5 scores was minimal.

- At 6 months posttreatment, the differences between the 3 treatment groups on PCL-5 score were negligible.

- CAPS-5 scores were significantly improved in all treatment arms, with improvement largest with in-home treatment; however, the differences between the groups were not significant.

- BDI-II scores improved in all modalities but were larger in the in-home (d = 1.2) and telehealth (d = 1.1) arms than the in-office arm (d = 0.52).

- Therapist time commitment was greater for the in-home and in-office arms (2 hours/session) than the telehealth arm (1 hour/session). This difference was due to commuting time for the patient or therapist.

- The dropout rate was not statistically significant between the groups.

- Adverse events did not significantly differ per group. The most commonly reported ones included nightmares, sleep difficulty, depression, anxiety, and irritability.

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients undergoing CPT had significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, with posttreatment PCL-5 improvement approximately twice as large in those who received the in-home and telehealth modalities vs in-office treatment.

- The group differences were not seen on CAPS-5 scores at posttreatment, or PCL-5 or CAPS-5 scores at 6 months posttreatment.

- In-home CPT was declined the most, which suggests that in-home distractions or the stigma of a mental health clinician being in their home played a role in patients’ decision-making. However, in-home CPT produced the greatest amount of improvement in PTSD symptoms. The authors concluded that in-home therapy should be reserved for those who are homebound or have travel limitations.

- This study shows evidence that telehealth may be a good modality for CPT, as seen by improvement in PTSD symptoms and good acceptability and retention.

- Limitations include more patients opting out of in-home CPT, and reimbursement for travel may not be available in the real-world setting.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Delmer O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am Psychol. 2019;74(5):596-607. doi: 10.1037/amp0000473

3. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, et al. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2015;314(5):489-500.

4. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Marmar CR. First-line psychotherapies for military-related PTSD. JAMA. 2020;323(7):656-657.

5. Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, Marques-Portella C, et al. Pharmacologic alternatives to antidepressants in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):169-180.

6. Krystal JH, Davis LL, Neylan TC, et al. It is time to address the crisis in the pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a consensus statement of the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82(7):e51-e59.

7. Feder A, Costi S, Rutter SB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(2):193-202. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20050596

8. Rauch SAM, Kim HM, Powell C, et al. Efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, sertraline hydrochloride, and their combination among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):117-126. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3412

9. Lehrner A, Hildebrandt T, Bierer LM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone augmentation of prolonged exposure for PTSD in US combat veterans. Behav Res Ther. 2021;144:103924. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2021.103924

10. Inslicht SS, Niles AN, Metzler TJ, et al. Randomized controlled experimental study of hydrocortisone and D-cycloserine effects on fear extinction in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(11):1945-1952. doi:10.1038/s41386-021-01222-z

11. Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

12. Bonn-Miller MO, Sisley S, Riggs P, et al. The short-term impact of 3 smoked cannabis preparations versus placebo on PTSD symptoms: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246990

13. Youngstedt SD, Kline CE, Reynolds AM, et al. Bright light treatment of combat-related PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. Milit Med. 2022;187(3-4):e435-e444. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab014

14. Peterson AL, Mintz J, Moring JC, et al. In-office, in-home, and telehealth cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12888-022-03699-4

15. Loflin MJ, Babson KA, Bonn-Miller MO. Cannabinoids as therapeutic for PTSD. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;14:78-83. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.12.001

16. Neumeister A, Praschak-Rieder N, Besselmann B, et al. Effects of tryptophan depletion on drug-free patients with seasonal affective disorder during a stable response to bright light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(2):133-138. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140043008

17. Kaysen D, Schumm J, Pedersen ER, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with comorbid PTSD and alcohol use disorders. Addict Behav. 2014;39(2):420-427. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.016

18. Resick PA, Wachen JS, Mintz J, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group cognitive processing therapy compared with group present-centered therapy for PTSD among active duty military personnel. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(6):1058-1068. doi:10.1037/ccp0000016

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. The lifetime prevalence among American adults is 6.8%.1 Management of PTSD includes treating distressing symptoms, reducing avoidant behaviors, treating comorbid conditions (eg, depression, substance use disorders, or mood dysregulation), and improving adaptive functioning, which includes restoring a psychological sense of safety and trust. PTSD can be treated using evidence-based psychotherapies, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both modalities. For adults, evidence-based treatment guidelines recommend the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, cognitive therapy, and prolonged exposure therapy.2 These guidelines also recommend (with some reservations) the use of brief eclectic psychotherapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and narrative exposure therapy.2 Although the evidence base for the use of medications is not as strong as that for the psychotherapies listed above, the guidelines recommend the use of fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine.2

Currently available treatments for PTSD have significant limitations. For example, trauma-focused psychotherapies can have significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, or treatment dropout.3,4 Additionally, such therapies are not widely accessible. As for pharmacotherapy, very few available options are supported by evidence, and the efficacy of these options is limited, as shown by the reports that only 60% of patients with PTSD show a response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and only 20% to 30% achieve complete remission.5 Additionally, it may take months for patients to achieve an acceptable level of improvement with medications. As a result, a substantial proportion of patients who seek treatment continue to remain symptomatic, with impaired levels of functioning. This lack of progress in PTSD treatment has been labeled as a national crisis, calling for an urgent need to find effective pharmacologic treatments for PTSD.6

In this article, we review 8 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of treatments for PTSD published within the last 5 years (Table7-14).

1. Feder A, Costi S, Rutter SB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(2):193-202

Feder et al had previously found a significant and quick decrease in PTSD symptoms after a single dose of IV ketamine had. This is the first RCT to examine the effectiveness and safety of repeated IV ketamine infusions for the treatment of persistent PTSD.7

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel-arm controlled trial treated 30 individuals with chronic PTSD with 6 infusions of either ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) over 2 consecutive weeks.

- Participants were individuals age 18 to 70 with a primary diagnosis of chronic PTSD according to the DSM-5 criteria and determined by The Structure Clinical Interview for DSM-5, with a score ≥30 on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

- Any severe or unstable medical condition, active suicidal or homicidal ideation, lifetime history of psychotic or bipolar disorder, current anorexia nervosa or bulimia, alcohol or substance use disorder within 3 months of screening, history of recreational ketamine or phencyclidine use on more than 1 occasion or any use in the previous 2 years, and ongoing treatment with a long-acting benzodiazepine or opioid medication were all considered exclusion criteria. Individuals who took short-acting benzodiazepines had their morning doses held on infusion days. Marijuana or cannabis derivatives were allowed.

- The primary outcome measure was a change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS-5. This was administered before the first infusion and weekly thereafter. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised, the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and adverse effect measurements were used as secondary outcome measures.

- Treatment response was defined as ≥30% symptom improvement 2 weeks after the first infusion as assessed with CAPS-5.

- Individuals who responded to treatment were followed naturalistically weekly for up to 4 weeks and then monthly until loss of responder status, or up to 6 months if there was no loss of response.

Outcomes

- At the second week, the mean CAPS-5 total score in the ketamine group was 11.88 points (SE = 3.96) lower than in the midazolam group (d = 1.13; 95% CI, 0.36 to 1.91).

- In the ketamine group, 67% of patients responded to therapy, compared to 20% in the midazolam group.

- Following the 2-week course of infusions, the median period until loss of response among ketamine responders was 27.5 days.

- Ketamine infusions showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated ketamine infusions are effective in reducing symptom severity in individuals with chronic PTSD.

- Limitations to this study include the exclusion of individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder, current alcohol or substance use disorder, or suicidal ideations, the small sample size, and a higher rate of transient dissociative symptoms in the ketamine group.

- Future studies could evaluate the efficacy of repeated ketamine infusions in individuals with treatment-resistant PTSD. Also, further studies are required to assess the efficacy of novel interventions to prevent relapse and evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of periodic IV ketamine use as maintenance.

- Additional research might determine whether pairing psychotherapy with ketamine administration can lessen the risk of recurrence for PTSD patients after stopping ketamine infusions.

2. Rauch SAM, Kim HM, Powell C, et al. Efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, sertraline hydrochloride, and their combination among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):117-126

Clinical practice recommendations for PTSD have identified trauma-focused psychotherapies and SSRIs as very effective treatments. The few studies that have compared trauma-focused psychotherapy to SSRIs or to a combination of treatments are not generalizable, have significant limitations, or are primarily concerned with refractory disorders or augmentation techniques. This study evaluated the efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy (PE) plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management in the treatment of PTSD.8

Study design

- This randomized, 4-site, 24-week clinical trial divided participants into 3 subgroups: PE plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management.

- Participants were veterans or service members of the Iraq and/or Afghanistan wars with combat-related PTSD and significant impairment as indicated by a CAPS score ≥50 for at least 3 months. The DSM-IV-TR version of CAPS was used because the DSM-5 version was not available at the time of the study.

- Individuals who had a current, imminent risk of suicide; active psychosis; alcohol or substance dependence in the past 8 weeks; inability to attend weekly appointments for the treatment period; prior intolerance to or failure of an adequate trial of PE or sertraline; medical illness likely to result in hospitalization or contraindication to study treatment; serious cognitive impairment; mild traumatic brain injury; or concurrent use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, prazosin, or sleep agents were excluded.

- Participants completed up to thirteen 90-minute sessions of PE.

- The sertraline dosage was titrated during a 10-week period and continued until Week 24. Dosages were adjusted between 50 and 200 mg/d, with the last dose increase at Week 10.

- The primary outcome measure was symptom severity of PTSD in the past month as determined by CAPS score at Week 24.

- The secondary outcome was self-reported symptoms of PTSD (PTSD checklist [PCL] Specific Stressor Version), clinically meaningful change (reduction of ≥20 points or score ≤35 on CAPS), response (reduction of ≥50% in CAPS score), and remission (CAPS score ≤35).

Outcomes

- At Week 24, 149 participants completed the study; 207 were included in the intent-to-treat analysis.

- PTSD symptoms significantly decreased over 24 weeks, according to a modified intent-to-treat analysis utilizing a mixed model of repeated measurements; nevertheless, slopes were similar across therapy groups.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Although the severity of PTSD symptoms decreased in all 3 subgroups, there was no difference in PTSD symptom severity or change in symptoms at Week 24 among all 3 subgroups.

- The main limitation of this study was the inclusion of only combat veterans.

- Further research should focus on enhancing treatment retention and should include administering sustained exposure therapy at brief intervals.

3. Lehrner A, Hildebrandt T, Bierer LM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone augmentation of prolonged exposure for PTSD in US combat veterans. Behav Res Ther. 2021;144:103924

First-line therapy for PTSD includes cognitive-behavioral therapies such as PE. However, because many people still have major adverse effects after receiving medication, improving treatment efficacy is a concern. Glucocorticoids promote extinction learning, and alterations in glucocorticoid signaling pathways have been associated with PTSD. Lehrner et al previously showed that adding hydrocortisone (HCORT) to PE therapy increased patients’ glucocorticoid sensitivity at baseline, improved treatment retention, and resulted in greater treatment improvements. This study evaluated HCORT in conjunction with PE for combat veterans with PTSD following deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan.9

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial administered HCORT 30 mg oral or placebo to 96 combat veterans 30 minutes before PE sessions.

- Participants were veterans previously deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq with deployment-related PTSD >6 months with a minimum CAPS score of 60. They were unmedicated or on a stable psychotropic regimen for ≥4 weeks.

- Exclusion criteria included a lifetime history of a primary psychotic disorder (bipolar I disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder), medical or mental health condition other than PTSD that required immediate clinical attention, moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), substance abuse or dependence within the past 3 months, medical illness that contraindicated ingestion of hydrocortisone, acute suicide risk, and pregnancy or intent to become pregnant.

- The primary outcome measures included PTSD severity as assessed with CAPS.

- Secondary outcome measures included self-reported PTSD symptoms as assessed with the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) and depression as assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI). These scales were administered pretreatment, posttreatment, and at 3-months follow-up.

Outcomes

- Out of 96 veterans enrolled, 60 were randomized and 52 completed the treatment.

- Five participants were considered recovered early and completed <12 sessions.

- Of those who completed treatment, 50 completed the 1-week posttreatment evaluations and 49 completed the 3-month follow-up evaluation.

- There was no difference in the proportion of dropouts (13.33%) across the conditions.

- HCORT failed to significantly improve either secondary outcomes or PTSD symptoms, according to an intent-to-treat analysis.

- However, exploratory analyses revealed that veterans with recent post-concussive symptoms and moderate TBI exposure saw a larger decrease in hyperarousal symptoms after PE therapy with HCORT augmentation.

- The reduction in avoidance symptoms with HCORT augmentation was also larger in veterans with higher baseline glucocorticoid sensitivity.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- HCORT does not improve PTSD symptoms as assessed with the CAPS and PDS, or depression as assessed with the BDI.

- The main limitation of this study is generalizability.

- Further studies are needed to determine whether PE with HCORT could benefit veterans with indicators of enhanced glucocorticoid sensitivity, mild TBI, or postconcussive syndrome.

4. Inslicht SS, Niles AN, Metzler TJ, et al. Randomized controlled experimental study of hydrocortisone and D-cycloserine effects on fear extinction in PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(11):1945-1952

PE, one of the most well-researched therapies for PTSD, is based on fear extinction. Exploring pharmacotherapies that improve fear extinction learning and their potential as supplements to PE is gaining increased attention. Such pharmacotherapies aim to improve the clinical impact of PE on the extent and persistence of symptom reduction. This study evaluated the effects of HCORT and D-cycloserine (DCS), a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, on the learning and consolidation of fear extinction in patients with PTSD.10

Study design

- This double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-group experimental design evaluated 90 individuals with PTSD who underwent fear conditioning with stimuli that was paired (CS+) or unpaired (CS−) with shock.

- Participants were veterans and civilians age 18 to 65 recruited from VA outpatient and community clinics and internet advertisements who met the criteria for PTSD or subsyndromal PTSD (according to DSM-IV criteria) for at least 3 months.

- Exclusion criteria included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance abuse or dependence, alcohol dependence, previous moderate or severe head injury, seizure or neurological disorder, current infectious illness, systemic illness affecting CNS function, or other conditions known to affect psychophysiological responses. Excluded medications were antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, alpha- and beta-adrenergics, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, and steroids.

- Extinction learning took place 72 hours after extinction, and extinction retention was evaluated 1 week later. Placebo, HCORT 25 mg, or DCS 50 mg was given 1 hour before extinction learning.

- Clinical measures included PTSD diagnosis and symptom levels as determined by interview using CAPS and skin conduction response.

Outcomes

- The mean shock level, mean pre-stimulus skin conductance level (SCL) during habituation, and mean SC orienting response during the habituation phase did not differ between groups and were not associated with differential fear conditioning. Therefore, variations in shock level preference, resting SCL, or SC orienting response magnitude are unlikely to account for differences between groups during extinction learning and retention.

- During extinction learning, the DCS and HCORT groups showed a reduced differential CS+/CS− skin conductance response (SCR) compared to placebo.

- One week later, during the retention testing, there was a nonsignificant trend toward a smaller differential CS+/CS− SCR in the DCS group compared to placebo. HCORT and DCS administered as a single dosage facilitated fear extinction learning in individuals with PTSD symptoms.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- In traumatized people with PTSD symptoms, a single dosage of HCORT or DCS enhanced the learning of fear extinction compared to placebo. A nonsignificant trend toward better extinction retention in the DCS group but not the HCORT group was also visible.

- These results imply that glucocorticoids and NMDA agonists have the potential to promote extinction learning in PTSD.

- Limitations include a lack of measures of glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity or FKBP5.

- Further studies could evaluate these findings with the addition of blood biomarker measures such as glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity or FKBP5.

5. Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

Poor PTSD treatment results are associated with numerous comorbid conditions, such as dissociation, depression, alcohol and substance use disorders, childhood trauma, and suicidal ideation, which frequently leads to treatment resistance. Therefore, it is crucial to find a treatment that works for individuals with PTSD who also have comorbid conditions. In animal models, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), an empathogen/entactogen with stimulant properties, has been shown to enhance fear memory extinction and modulate fear memory reconsolidation. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of MDMA-assisted therapy for treating patients with severe PTSD, including those with common comorbidities.11

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-site, phase 3 clinical trial evaluated individuals randomized to receive manualized therapy with MDMA or with placebo, combined with 3 preparatory and 9 integrative therapy sessions.

- Participants were 90 individuals (46 randomized to MDMA and 44 to placebo) with PTSD with a symptom duration ≥6 months and CAPS-5 total severity score ≥35 at baseline.

- Exclusion criteria included primary psychotic disorder, bipolar I disorder, eating disorders with active purging, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, dissociative identity disorder, personality disorders, current alcohol and substance use disorders, lactation or pregnancy, and any condition that could make receiving a sympathomimetic medication dangerous due to hypertension or tachycardia, including uncontrolled hypertension, history of arrhythmia, or marked baseline prolongation of QT and/or QTc interval.

- Three 8-hour experimental sessions of either therapy with MDMA assistance or therapy with a placebo control were given during the treatment period, and they were spaced approximately 4 weeks apart.

- In each session, participants received placebo or a single divided dose of MDMA 80 to 180 mg.

- At baseline and 2 months after the last experimental sessions, PTSD symptoms were measured with CAPS-5, and functional impairment was measured with Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS).

- The primary outcome measure was CAPS-5 total severity score at 18 weeks compared to baseline for MDMA-assisted therapy vs placebo-assisted therapy.

- The secondary outcome measure was clinician-rated functional impairment using the mean difference in SDS total scores from baseline to 18 weeks for MDMA-assisted therapy vs placebo-assisted therapy.

Outcomes

- MDMA was found to induce significant and robust attenuation in CAPS-5 score compared to placebo.

- The mean change in CAPS-5 score in completers was –24.4 in the MDMA group and –13.9 in the placebo group.

- MDMA significantly decreased the SDS total score.

- MDMA did not induce suicidality, misuse, or QT prolongation.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- MDMA-assisted therapy is significantly more effective than manualized therapy with placebo in treating patients with severe PTSD, and it is also safe and well-tolerated, even in individuals with comorbidities.

- No major safety issues were associated with MDMA-assisted treatment.

- MDMA-assisted therapy should be promptly assessed for clinical usage because it has the potential to significantly transform the way PTSD is treated.

- Limitations of this study include a smaller sample size (due to the COVID-19 pandemic); lack of ethnic and racial diversity; short duration; safety data were collected by site therapist, which limited the blinding; and the blinding of participants was difficult due to the subjective effects of MDMA, which could have resulted in expectation effects.

6. Bonn-Miller MO, Sisley S, Riggs P, et al. The short-term impact of 3 smoked cannabis preparations versus placebo on PTSD symptoms: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246990

Sertraline and paroxetine are the only FDA-approved medications for treating PTSD. Some evidence suggests cannabis may provide a therapeutic benefit for PTSD.15 This study examined the effects of 3 different preparations of cannabis for treating PTSD symptoms.12

Study design

- This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial used 3 active treatment groups of cannabis: high delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)/low cannabidiol (CBD), high CBD/low THC, and high THC/high CBD (THC+CBD). A low THC/low CBD preparation was used as a placebo. “High” content contained 9% to 15% concentration by weight of the respective cannabinoid, and “low” content contained <2% concentration by weight.

- Inclusion criteria included being a US military veteran, meeting DSM-5 PTSD criteria for ≥6 months, having moderate symptom severity (CAPS-5 score ≥25), abstaining from cannabis 2 weeks prior to study and agreeing not to use any non-study cannabis during the trial, and being stable on medications/therapy prior to the study.

- Exclusion criteria included women who were pregnant/nursing/child-bearing age and not taking an effective means of birth control; current/past serious mental illness, including psychotic and personality disorders; having a first-degree relative with a psychotic or bipolar disorder; having a high suicide risk based on Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; meeting DSM-5 criteria for moderate-severe cannabis use disorder; screening positive for illicit substances; or having significant medical disease.

- Participants in Stage 1 (n = 80) were randomized to 1 of the 3 active treatments or placebo for 3 weeks. After a 2-week washout, participants in Stage 2 (n = 74) were randomized to receive for 3 weeks 1 of the 3 active treatments they had not previously received.

- During each stage, participants had ad libitum use for a maximum of 1.8 g/d.

- The primary outcome was change in PTSD symptom severity by the end of Stage 1 as assessed with CAPS-5.

- Secondary outcomes included the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the general depression subscale and anxiety subscale from the self-report Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS), the Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning, and the Insomnia Severity Index.

Outcomes

- Six participants did not continue to Stage 2. Three participants did not finish Stage 2 due to adverse effects, and 7 did not complete outcome measurements. The overall attrition rate was 16.3%.

- There was no significant difference in total grams of smoked cannabis or placebo between the 4 treatment groups in Stage 1 at the end of 3 weeks. In Stage 2, there was a significant difference, with the THC+CBD group using more cannabis compared to the other 2 groups.

- Each of the 4 groups had significant reductions in total CAPS-5 scores at the end of Stage 1, and there was no significant difference in CAPS-5 severity scores between the 4 groups.

- In Stage 1, PCL-5 scores were not significantly different between treatment groups from baseline to the end of stage. There was a significant difference in Stage 2 between the high CBD and THC+CBD groups, with the combined group reporting greater improvement of symptoms.

- In Stage 2, the THC+CBD group reported greater reductions in pre/post IDAS social anxiety scores and IDAS general depression scores, and the high THC group reported greater reductions in pre/post IDAS social anxiety scores.

- In Stage 1, 37 of 60 participants in the active groups reported at least 1 adverse event, and 45 of the 74 Stage 2 participants reported at least 1 adverse event. The most common adverse events were cough, throat irritation, and anxiety. Participants in the Stage 1 high THC group had a significant increase in reported withdrawal symptoms after 1 week of stopping use.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- This first randomized, placebo-control trial of cannabis in US veterans did not show a significant difference among treatment groups, including placebo, on the primary outcome of CAPS-5 score. All 4 groups had significant reductions in symptom severity on CAPS-5 and showed good tolerability.

- Prior beliefs about the effects of cannabis may have played a role in the reduction of PTSD symptoms in the placebo group.

- Many participants (n =34) were positive for THC during the screening process, so previous cannabis use/chronicity of cannabis use may have contributed.

- One limitation was that participants assigned to the Stage 1 high THC group had Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test scores (which assesses cannabis use disorder risk) about 2 times greater than participants in other conditions.

- Another limitation was that total cannabis use was lower than expected, as participants in Stage 1 used 8.2 g to 14.6 g over 3 weeks, though they had access to up to 37.8 g.

- There was no placebo in Stage 2.

- Future studies should look at longer treatment periods with more participants.

7. Youngstedt SD, Kline CE, Reynolds AM, et al. Bright light treatment of combat-related PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. Milit Med. 2022;187(3-4):e435-e444

Bright light therapy is an inexpensive treatment approach that may affect serotonergic pathways.16 This study examined bright light therapy for reducing PTSD symptoms and examined if improvement of PTSD is related to a shift in circadian rhythm.13

Study design

- Veterans with combat-related PTSD had to have been stable on treatment for at least 8 weeks or to have not received any other PTSD treatments prior to the study.

- Participants were randomized to active treatment of 30 minutes daily 10,000 lux ultraviolet-filtered white light while sitting within 18 inches (n = 34) or a control condition of 30 minutes daily inactivated negative ion generator (n = 35) for 4 weeks.

- Inclusion criteria included a CAPS score ≥30.

- Exclusion criteria included high suicidality, high probability of alcohol/substance abuse in the past 3 months, bipolar disorder/mania/schizophrenia/psychosis, ophthalmologic deformities, shift work in past 2 months or travel across time zones in past 2 weeks, head trauma, high outdoor light exposure, history of winter depression, history of seizures, or myocardial infarction/stroke/cancer within 3 years.

- Primary outcomes were improvement on CAPS and Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (CGI-IM) score at Week 4.

- Wrist actigraphy recordings measured sleep.

- Other measurements included the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Hamilton atypical symptoms (HAM-AS), PCL-Military (PCL-M), Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), BDI, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI Form Y-2), Beck Suicide Scale, and Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects questionnaire.

Outcomes

- There was a significant decrease in CAPS score in participants who received bright light therapy compared to controls. Treatment response (defined as ≥33% reduction in score) was significantly greater in the bright light (44%) vs control (8.6%) group. No participants achieved remission.

- There was a significant improvement in CGI-IM scores in the bright light group, but no significant difference in participants who were judged to improve “much” or “very much.”

- PCL-M scores did not change significantly between groups, although a significantly greater proportion of participants had treatment response in the bright light group (33%) vs control (6%).

- There were no significant changes in HAM-D, HAM-AS, STAI, BDI, actigraphic estimates of sleep, or PSQI scores.

- Bright light therapy resulted in phase advancement while control treatment had phase delay.

- There were no significant differences in adverse effects.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Bright light therapy may be a treatment option or adjunct for combat-related PTSD as seen by improvement on CAPS and CGI scores, as well as a greater treatment response seen on CAPS and PCL-5 scores in the bright light group.

- There was no significant difference for other measures, including depression, anxiety, and sleep.

- Limitations include excluding patients with a wide variety of medical or psychiatric comorbidities, as well as limited long-term follow up data.

- Other limitations include not knowing the precise amount of time participants stayed in front of the light device and loss of some actigraphic data (data from only 49 of 69 participants).

8. Peterson AL, Mintz J, Moring JC, et al. In-office, in-home, and telehealth cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):41 doi:10.1186/s12888-022-03699-4

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT), a type of trauma-focused psychotherapy, is an effective treatment for PTSD in the military population.17,18 However, patients may not be able to or want to participate in such therapy due to barriers such as difficulty arranging transportation, being homebound due to injury, concerns about COVID-19, stigma, familial obligations, and job constraints. This study looked at if CPT delivered face-to-face at the patient’s home or via telehealth in home would be effective and increase accessibility.14

Study design

- Participants (n = 120) were active-duty military and veterans who met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. They were randomized to receive CPT in the office, in their home, or via telehealth. Participants could choose not to partake in 1 modality but were then randomized to 1 of the other 2.

- Exclusion criteria included suicide/homicide risk needing intervention, items/situations pertaining to danger (ie, aggressive pet or unsafe neighborhood), significant alcohol/substance use, active psychosis, and impaired cognitive functioning.

- The primary outcome measurement was change in PCL-5 and CAPS-5 score over 6 months. The BDI-II was used to assess depressive symptoms.

- Secondary outcomes included the Reliable Change Index (defined as “an improvement of 10 or more points that was sustained at all subsequent assessments”) on the PCL-5 and remission on the CAPS-5.

- CPT was delivered in 60-minute sessions twice a week for 6 weeks. Participants who did not have electronic resources were loaned a telehealth apparatus.

Outcomes

- Overall, 57% of participants opted out of 1 modality, which resulted in fewer participants being placed into the in-home arm (n = 32). Most participants chose not to do in-home treatments (54%), followed by in-office (29%), and telehealth (17%).

- There was a significant posttreatment improvement in PCL-5 scores in all treatment arms, with improvement greater with in-home (d = 2.1) and telehealth (d = 2.0) vs in-office (d=1.3). The in-home and telehealth scores were significantly improved compared to in-office, and the difference between in-home and telehealth PCL-5 scores was minimal.

- At 6 months posttreatment, the differences between the 3 treatment groups on PCL-5 score were negligible.

- CAPS-5 scores were significantly improved in all treatment arms, with improvement largest with in-home treatment; however, the differences between the groups were not significant.

- BDI-II scores improved in all modalities but were larger in the in-home (d = 1.2) and telehealth (d = 1.1) arms than the in-office arm (d = 0.52).

- Therapist time commitment was greater for the in-home and in-office arms (2 hours/session) than the telehealth arm (1 hour/session). This difference was due to commuting time for the patient or therapist.

- The dropout rate was not statistically significant between the groups.

- Adverse events did not significantly differ per group. The most commonly reported ones included nightmares, sleep difficulty, depression, anxiety, and irritability.

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients undergoing CPT had significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, with posttreatment PCL-5 improvement approximately twice as large in those who received the in-home and telehealth modalities vs in-office treatment.

- The group differences were not seen on CAPS-5 scores at posttreatment, or PCL-5 or CAPS-5 scores at 6 months posttreatment.

- In-home CPT was declined the most, which suggests that in-home distractions or the stigma of a mental health clinician being in their home played a role in patients’ decision-making. However, in-home CPT produced the greatest amount of improvement in PTSD symptoms. The authors concluded that in-home therapy should be reserved for those who are homebound or have travel limitations.

- This study shows evidence that telehealth may be a good modality for CPT, as seen by improvement in PTSD symptoms and good acceptability and retention.

- Limitations include more patients opting out of in-home CPT, and reimbursement for travel may not be available in the real-world setting.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic and disabling psychiatric disorder. The lifetime prevalence among American adults is 6.8%.1 Management of PTSD includes treating distressing symptoms, reducing avoidant behaviors, treating comorbid conditions (eg, depression, substance use disorders, or mood dysregulation), and improving adaptive functioning, which includes restoring a psychological sense of safety and trust. PTSD can be treated using evidence-based psychotherapies, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of both modalities. For adults, evidence-based treatment guidelines recommend the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive processing therapy, cognitive therapy, and prolonged exposure therapy.2 These guidelines also recommend (with some reservations) the use of brief eclectic psychotherapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and narrative exposure therapy.2 Although the evidence base for the use of medications is not as strong as that for the psychotherapies listed above, the guidelines recommend the use of fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine.2

Currently available treatments for PTSD have significant limitations. For example, trauma-focused psychotherapies can have significant rates of nonresponse, partial response, or treatment dropout.3,4 Additionally, such therapies are not widely accessible. As for pharmacotherapy, very few available options are supported by evidence, and the efficacy of these options is limited, as shown by the reports that only 60% of patients with PTSD show a response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and only 20% to 30% achieve complete remission.5 Additionally, it may take months for patients to achieve an acceptable level of improvement with medications. As a result, a substantial proportion of patients who seek treatment continue to remain symptomatic, with impaired levels of functioning. This lack of progress in PTSD treatment has been labeled as a national crisis, calling for an urgent need to find effective pharmacologic treatments for PTSD.6

In this article, we review 8 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of treatments for PTSD published within the last 5 years (Table7-14).

1. Feder A, Costi S, Rutter SB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(2):193-202

Feder et al had previously found a significant and quick decrease in PTSD symptoms after a single dose of IV ketamine had. This is the first RCT to examine the effectiveness and safety of repeated IV ketamine infusions for the treatment of persistent PTSD.7

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, parallel-arm controlled trial treated 30 individuals with chronic PTSD with 6 infusions of either ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) or midazolam (0.045 mg/kg) over 2 consecutive weeks.

- Participants were individuals age 18 to 70 with a primary diagnosis of chronic PTSD according to the DSM-5 criteria and determined by The Structure Clinical Interview for DSM-5, with a score ≥30 on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

- Any severe or unstable medical condition, active suicidal or homicidal ideation, lifetime history of psychotic or bipolar disorder, current anorexia nervosa or bulimia, alcohol or substance use disorder within 3 months of screening, history of recreational ketamine or phencyclidine use on more than 1 occasion or any use in the previous 2 years, and ongoing treatment with a long-acting benzodiazepine or opioid medication were all considered exclusion criteria. Individuals who took short-acting benzodiazepines had their morning doses held on infusion days. Marijuana or cannabis derivatives were allowed.

- The primary outcome measure was a change in PTSD symptom severity as measured with CAPS-5. This was administered before the first infusion and weekly thereafter. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised, the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and adverse effect measurements were used as secondary outcome measures.

- Treatment response was defined as ≥30% symptom improvement 2 weeks after the first infusion as assessed with CAPS-5.

- Individuals who responded to treatment were followed naturalistically weekly for up to 4 weeks and then monthly until loss of responder status, or up to 6 months if there was no loss of response.

Outcomes

- At the second week, the mean CAPS-5 total score in the ketamine group was 11.88 points (SE = 3.96) lower than in the midazolam group (d = 1.13; 95% CI, 0.36 to 1.91).

- In the ketamine group, 67% of patients responded to therapy, compared to 20% in the midazolam group.

- Following the 2-week course of infusions, the median period until loss of response among ketamine responders was 27.5 days.

- Ketamine infusions showed good tolerability and safety. There were no clinically significant adverse effects.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated ketamine infusions are effective in reducing symptom severity in individuals with chronic PTSD.

- Limitations to this study include the exclusion of individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder, current alcohol or substance use disorder, or suicidal ideations, the small sample size, and a higher rate of transient dissociative symptoms in the ketamine group.

- Future studies could evaluate the efficacy of repeated ketamine infusions in individuals with treatment-resistant PTSD. Also, further studies are required to assess the efficacy of novel interventions to prevent relapse and evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of periodic IV ketamine use as maintenance.

- Additional research might determine whether pairing psychotherapy with ketamine administration can lessen the risk of recurrence for PTSD patients after stopping ketamine infusions.

2. Rauch SAM, Kim HM, Powell C, et al. Efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, sertraline hydrochloride, and their combination among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):117-126

Clinical practice recommendations for PTSD have identified trauma-focused psychotherapies and SSRIs as very effective treatments. The few studies that have compared trauma-focused psychotherapy to SSRIs or to a combination of treatments are not generalizable, have significant limitations, or are primarily concerned with refractory disorders or augmentation techniques. This study evaluated the efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy (PE) plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management in the treatment of PTSD.8

Study design

- This randomized, 4-site, 24-week clinical trial divided participants into 3 subgroups: PE plus placebo, PE plus sertraline, and sertraline plus enhanced medication management.

- Participants were veterans or service members of the Iraq and/or Afghanistan wars with combat-related PTSD and significant impairment as indicated by a CAPS score ≥50 for at least 3 months. The DSM-IV-TR version of CAPS was used because the DSM-5 version was not available at the time of the study.

- Individuals who had a current, imminent risk of suicide; active psychosis; alcohol or substance dependence in the past 8 weeks; inability to attend weekly appointments for the treatment period; prior intolerance to or failure of an adequate trial of PE or sertraline; medical illness likely to result in hospitalization or contraindication to study treatment; serious cognitive impairment; mild traumatic brain injury; or concurrent use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, prazosin, or sleep agents were excluded.

- Participants completed up to thirteen 90-minute sessions of PE.