User login

Atypical Keratotic Nodule on the Knuckle

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

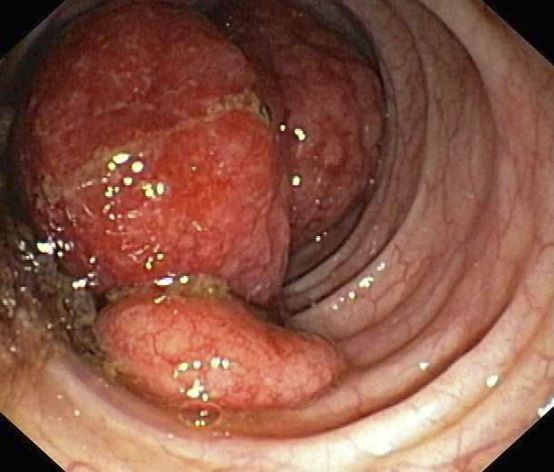

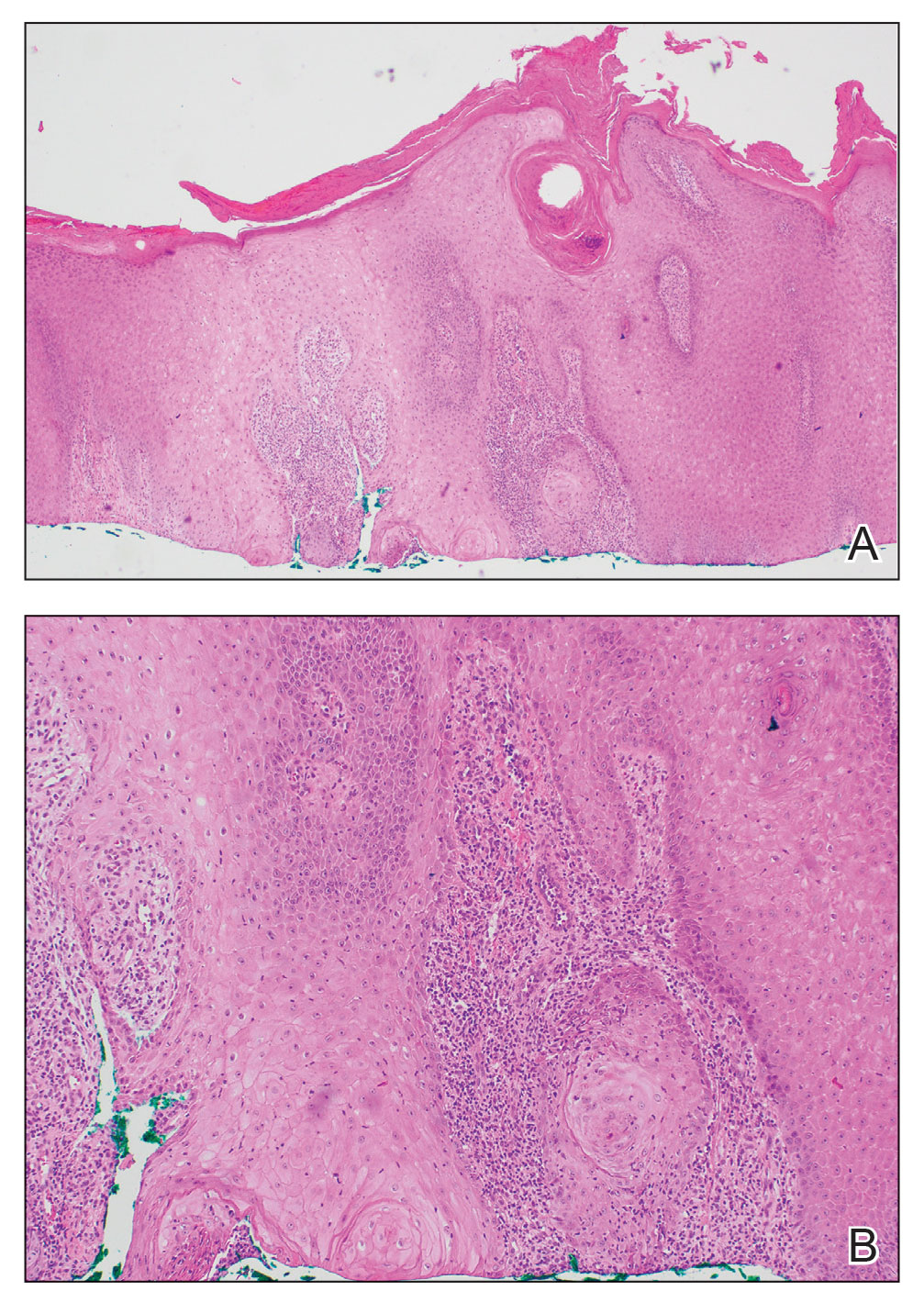

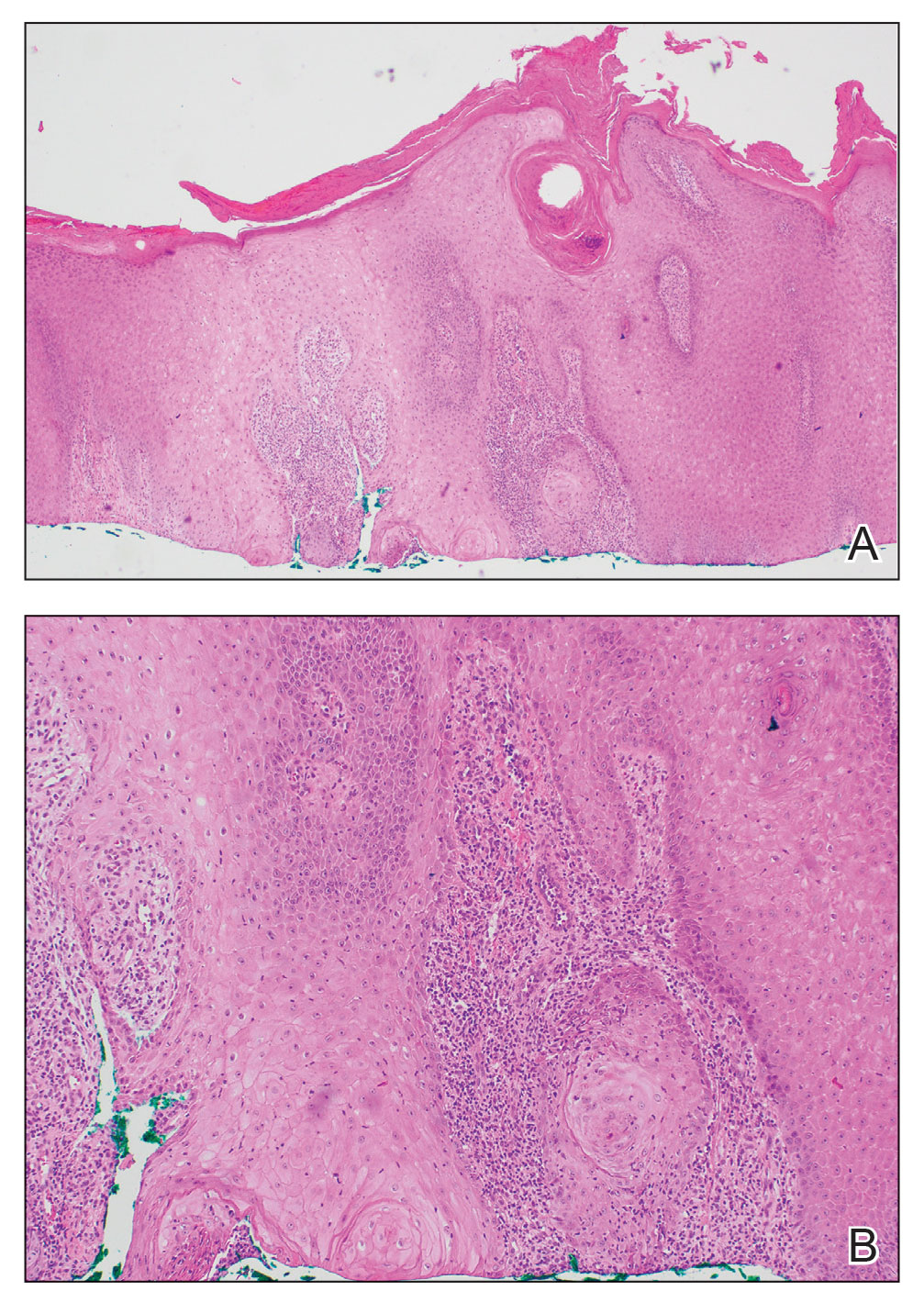

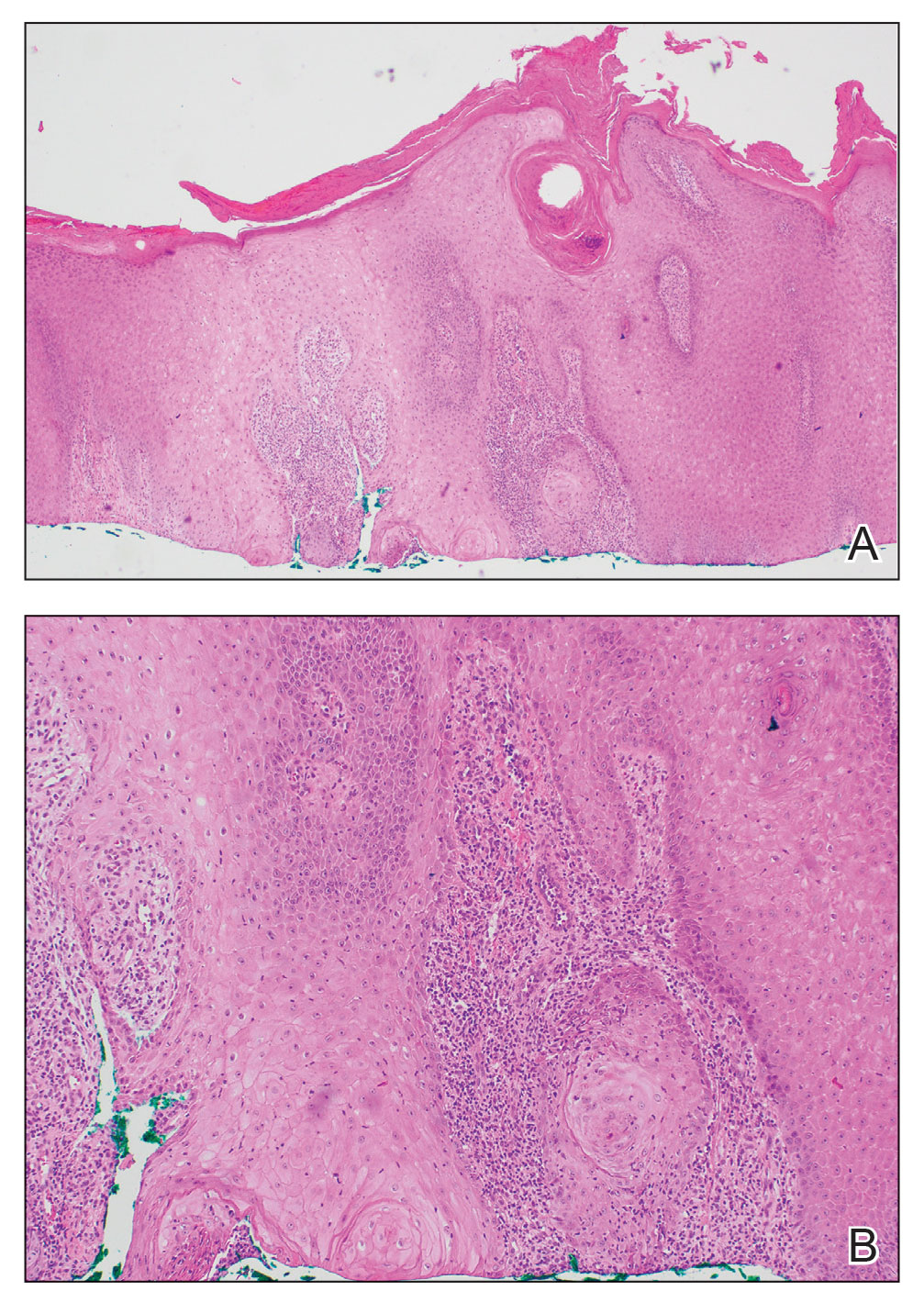

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

A 75-year-old man presented with a lesion on the knuckle of 5 months’ duration. He reported that the lesion initially grew very quickly before shrinking down to its current size. He denied any bleeding or pain but thought he may have had a splinter in the area around the time the lesion appeared. He reported spending a lot of time outdoors and noted several recent insect and tick bites. He also owned a boat and frequently went fishing. He previously had been treated for actinic keratoses but had no history of skin cancer and no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm erythematous nodule with central hyperkeratosis overlying the metacarpophalangeal joint of the right index finger. A shave biopsy was performed.

Feedback and Education in Dermatology Residency

A dermatology resident has more education and experience than a medical student or intern but less than a fellow or attending physician. Because of this position, residents have a unique opportunity to provide feedback and education to those with less knowledge and experience as a teacher and also to provide feedback to their more senior colleagues about their teaching effectiveness while simultaneously learning from them. The reciprocal exchange of information—from patients and colleagues in clinic, co-residents or attendings in lectures, or in other environments such as pathology at the microscope or skills during simulation training sessions—is the cornerstone of medical education. Being able to give effective feedback while also learning to accept it is one of the most vital skills a resident can learn to thrive in medical education.

The importance of feedback cannot be understated. The art of medicine involves the scientific knowledge needed to treat disease, as well as the social ability to educate, comfort, and heal those afflicted. Mastering this art takes a lifetime. The direct imparting of knowledge from those more experienced to those learning occurs via feedback. In addition, the desire to better oneself leads to more satisfaction with work and improved performance.1 The ability to give and receive feedback is vital for the field of dermatology and medicine in general.

Types and Implementation of Feedback

Feedback comes in many forms and can be classified via different characteristics such as formal vs informal, written vs spoken, real time vs delayed, and single observer vs pooled data. Each style of feedback has positive and negative aspects, and a feedback provider will need to weigh the pros and cons when deciding the most appropriate one. Although there is no one correct way to provide feedback, the literature shows that some forms of feedback may be more effective and better received than others. This can depend on the context of what is being evaluated.

Many dermatology residencies employ formal scheduled feedback as part of their curricula, ensuring that residents will receive feedback at preset time intervals and providing residency directors with information to assess improvement and areas where more growth is needed. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education provides a reference for programs on how to give this formal standardized feedback in The Milestones Guidebook.2 This feedback is a minimum required amount, with a survey of residents showing preference for frequent informal feedback sessions in addition to standardized formal feedback.3 Another study showed that residents want feedback that is confidential, in person, shortly after experiences, and specific to their actions.4 Medical students also voiced a need for frequent, transparent, and actionable feedback during protected, predetermined, and communicated times.5 Clearly, learners appreciate spoken intentional feedback as opposed to the traditional formal model of feedback.

Finally, a study was performed analyzing how prior generations of physician educators view millennial trainees.6 Because most current dermatology residents were born between 1981 and 1996, this study seemed to pinpoint thoughts toward teaching current residents. The study found that although negative judgments such as millennial entitlement (P<.001), impoliteness (P<.001), oversensitivity (P<.001), and inferior work ethic (P<.001) reached significance, millennial ideals of social justice (P<.001) and savviness with technology (P<.001) also were notable. Overall, millennials were thought to be good colleagues (P<.001), were equally competent to more experienced clinicians (P<.001), and would lead medicine to a good future (P=.039).6

Identifying and Maximizing the Impact of Feedback

In addition to how and when to provide feedback, there are discrepancies between attending and resident perception of what is considered feedback. This disconnect can be seen in a study of 122 respondents (67 residents and 55 attendings) that showed 31% of attendings reported giving feedback daily, as opposed to only 9% of residents who reported receiving daily feedback.4 When feedback is to be performed, it may be important to specifically announce the process so that it can be properly acknowledged.7

Beach8 provided a systematic breakdown of clinical teaching to those who may be unfamiliar with the process. This method is divided into preclinic, in-clinic, and postclinic strategies to maximize learning. The author recommended establishing the objectives of the rotation from the teacher’s perspective and inquiring about the objectives of the learner. Both perspectives should inform the lessons to be learned; for example, if a medical student expresses specific interest in psoriasis (a well-established part of a medical student curriculum), all efforts should be placed on arranging for that student to see those specific patients. Beach8 also recommended providing resources and creating a positive supportive learning environment to better utilize precious clinic time and create investment in all learning parties. The author recommended matching trainees during clinic to competence-specific challenges in clinical practice where appropriate technical skill is needed. Appropriate autonomy also is promoted, as it requires higher levels of learning and knowledge consolidation. Group discussions can be facilitated by asking questions of increasing levels of difficulty as experience increases. Finally, postclinic feedback should be timely and constructive.8

One technique discussed by Beach8 is the “1-minute preceptor plus” approach. In this approach, the teacher wants to establish 5 “micro-skills” by first getting a commitment, then checking for supportive evidence of this initial plan, teaching a general principle, reinforcing what was properly performed, and correcting errors. The “plus” comes from trying to take that lesson and apply it to a broader concept. Although this concept is meant to be used in a time-limited setting, it can be expanded to larger conversations. A common example could be made when residents teach rotating medical students through direct observation and supervision during clinic. In this hypothetical situation, the resident and medical student see a patient with erythematous silver-scaled plaques on the elbows and knees. During the patient encounter, the student then inquires about any personal history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. After leaving the examination room, the medical student asserts the diagnosis is plaque psoriasis because of the physical examination findings and distribution of lesions. A discussion about the relationship between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome commences, emphasizing the pathophysiology of type 1 helper T-cell–mediated and type 17 helper T-cell–mediated inflammation with vascular damage and growth from inflammatory cytokines.9 The student subsequently is praised on inquiring about relevant comorbidities, and a relevant journal article is retrieved for the student’s future studies. Teaching points regarding the Koebner phenomenon, such as that it is not an instantaneous process and comes with a differential diagnosis, are then provided.

Situation-Behavior-Impact is another teaching method developed by the Center for Creative Leadership. In this technique, one will identify what specifically happened, how the learner responded, and what occurred because of the response.10 This technique is exemplified in the following mock conversation between an attending and their resident following a challenging patient situation: “When you walked into the room and asked the patient coming in for a follow-up appointment ‘What brings you in today?,’ they immediately tensed up and responded that you should already know and check your electronic medical record. This tension could be ameliorated by reviewing the patient’s medical record and addressing what they initially presented for, followed by inquiring if there are other skin problems they want to discuss afterwards.” By identifying the cause-and-effect relationship, helpful and unhelpful responses can be identified and ways to mitigate or continue behaviors can be brainstormed.

The Learning Process

Brodell et all11 outlined techniques to augment the education process that are specific to dermatology. They recommended learning general applicable concepts instead of contextless memorization, mnemonic devices to assist memory for associations and lists, and repetition and practice of learned material. For teaching, they divided techniques into Aristotelian or Socratic; Aristotelian teaching is the formal lecture style, whereas Socratic is conversation based. Both have a place in teaching—as fundamental knowledge grows via Aristotelian teaching, critical thinking can be enhanced via the Socratic method. The authors then outlined tips to create the most conducive learning environment for students.11

Feedback is a reciprocal process with information being given and received by both the teacher and the learner. This is paramount because perfecting the art of teaching is a career-long process and can only be achieved via correction of oversights and mistakes. A questionnaire-based study found that when critiquing the teacher, a combination of self-assessment with assessment from learners was effective in stimulating the greatest level of change in the teacher.12 This finding likely is because the educator was able to see the juxtaposition of how they think they performed with how students interpreted the same situation. Another survey-based study showed that of 68 attending physicians, 28 attendings saw utility in specialized feedback training; an additional 11 attendings agreed with online modules to improve their feedback skills. A recommendation that trainees receive training on the acceptance feedback also was proposed.13 Specialized training to give and receive feedback could be initiated for both attending and resident physicians to fully create an environment emphasizing improvement and teamwork.

Final Thoughts

The art of giving and receiving feedback is a deliberate process that develops with experience and training. Because residents are early in their medical career, being familiar with techniques such as those outlined in this article can enhance teaching and the reception of feedback. Residents are in a unique position, as residency itself is a time of dramatic learning and teaching. Providing feedback gives us a way to advance medicine and better ourselves by solidifying good habits and knowledge.

Acknowledgment—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and reviewing this article.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, et al. The Milestones Guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/milestonesguidebook.pdf

- Wang JV, O’Connor M, McGuinn K, et al. Feedback practices in dermatology residency programs: building a culture for millennials. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:282-283.

- Hajar T, Wanat KA, Fett N. Survey of resident physician and attending physician feedback perceptions: there is still work to be done. Dermatol Online J. 2020;25:13030/qt2sg354p6.

- Yoon J, Said JT, Thompson LL, et al. Medical student perceptions of assessment systems, subjectivity, and variability on introductory dermatology clerkships. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:232-330.

- Marka A, LeBoeuf MR, Vidal NY. Perspectives of dermatology faculty toward millennial trainees and colleagues: a national survey. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5:65-71.

- Bernard AW, Kman NE, Khandelwal S. Feedback in the emergency medicine clerkship. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:537-542.

- Beach RA. Strategies to maximise teaching in your next ambulatory clinic. Clin Teach. 2017;14:85-89.

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases part I. epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

- Olbricht SM. What makes feedback productive? Cutis. 2016;98:222-223.

- Brodell RT, Wile MZ, Chren M, et al. Learning and teaching in dermatology: a practitioner’s guide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:946-952.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, et al. Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2010;15:315-328.

- Chelliah P, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. What makes giving feedback challenging? a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD)[published online July 19, 2022]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02370-y

A dermatology resident has more education and experience than a medical student or intern but less than a fellow or attending physician. Because of this position, residents have a unique opportunity to provide feedback and education to those with less knowledge and experience as a teacher and also to provide feedback to their more senior colleagues about their teaching effectiveness while simultaneously learning from them. The reciprocal exchange of information—from patients and colleagues in clinic, co-residents or attendings in lectures, or in other environments such as pathology at the microscope or skills during simulation training sessions—is the cornerstone of medical education. Being able to give effective feedback while also learning to accept it is one of the most vital skills a resident can learn to thrive in medical education.

The importance of feedback cannot be understated. The art of medicine involves the scientific knowledge needed to treat disease, as well as the social ability to educate, comfort, and heal those afflicted. Mastering this art takes a lifetime. The direct imparting of knowledge from those more experienced to those learning occurs via feedback. In addition, the desire to better oneself leads to more satisfaction with work and improved performance.1 The ability to give and receive feedback is vital for the field of dermatology and medicine in general.

Types and Implementation of Feedback

Feedback comes in many forms and can be classified via different characteristics such as formal vs informal, written vs spoken, real time vs delayed, and single observer vs pooled data. Each style of feedback has positive and negative aspects, and a feedback provider will need to weigh the pros and cons when deciding the most appropriate one. Although there is no one correct way to provide feedback, the literature shows that some forms of feedback may be more effective and better received than others. This can depend on the context of what is being evaluated.

Many dermatology residencies employ formal scheduled feedback as part of their curricula, ensuring that residents will receive feedback at preset time intervals and providing residency directors with information to assess improvement and areas where more growth is needed. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education provides a reference for programs on how to give this formal standardized feedback in The Milestones Guidebook.2 This feedback is a minimum required amount, with a survey of residents showing preference for frequent informal feedback sessions in addition to standardized formal feedback.3 Another study showed that residents want feedback that is confidential, in person, shortly after experiences, and specific to their actions.4 Medical students also voiced a need for frequent, transparent, and actionable feedback during protected, predetermined, and communicated times.5 Clearly, learners appreciate spoken intentional feedback as opposed to the traditional formal model of feedback.

Finally, a study was performed analyzing how prior generations of physician educators view millennial trainees.6 Because most current dermatology residents were born between 1981 and 1996, this study seemed to pinpoint thoughts toward teaching current residents. The study found that although negative judgments such as millennial entitlement (P<.001), impoliteness (P<.001), oversensitivity (P<.001), and inferior work ethic (P<.001) reached significance, millennial ideals of social justice (P<.001) and savviness with technology (P<.001) also were notable. Overall, millennials were thought to be good colleagues (P<.001), were equally competent to more experienced clinicians (P<.001), and would lead medicine to a good future (P=.039).6

Identifying and Maximizing the Impact of Feedback

In addition to how and when to provide feedback, there are discrepancies between attending and resident perception of what is considered feedback. This disconnect can be seen in a study of 122 respondents (67 residents and 55 attendings) that showed 31% of attendings reported giving feedback daily, as opposed to only 9% of residents who reported receiving daily feedback.4 When feedback is to be performed, it may be important to specifically announce the process so that it can be properly acknowledged.7

Beach8 provided a systematic breakdown of clinical teaching to those who may be unfamiliar with the process. This method is divided into preclinic, in-clinic, and postclinic strategies to maximize learning. The author recommended establishing the objectives of the rotation from the teacher’s perspective and inquiring about the objectives of the learner. Both perspectives should inform the lessons to be learned; for example, if a medical student expresses specific interest in psoriasis (a well-established part of a medical student curriculum), all efforts should be placed on arranging for that student to see those specific patients. Beach8 also recommended providing resources and creating a positive supportive learning environment to better utilize precious clinic time and create investment in all learning parties. The author recommended matching trainees during clinic to competence-specific challenges in clinical practice where appropriate technical skill is needed. Appropriate autonomy also is promoted, as it requires higher levels of learning and knowledge consolidation. Group discussions can be facilitated by asking questions of increasing levels of difficulty as experience increases. Finally, postclinic feedback should be timely and constructive.8

One technique discussed by Beach8 is the “1-minute preceptor plus” approach. In this approach, the teacher wants to establish 5 “micro-skills” by first getting a commitment, then checking for supportive evidence of this initial plan, teaching a general principle, reinforcing what was properly performed, and correcting errors. The “plus” comes from trying to take that lesson and apply it to a broader concept. Although this concept is meant to be used in a time-limited setting, it can be expanded to larger conversations. A common example could be made when residents teach rotating medical students through direct observation and supervision during clinic. In this hypothetical situation, the resident and medical student see a patient with erythematous silver-scaled plaques on the elbows and knees. During the patient encounter, the student then inquires about any personal history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. After leaving the examination room, the medical student asserts the diagnosis is plaque psoriasis because of the physical examination findings and distribution of lesions. A discussion about the relationship between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome commences, emphasizing the pathophysiology of type 1 helper T-cell–mediated and type 17 helper T-cell–mediated inflammation with vascular damage and growth from inflammatory cytokines.9 The student subsequently is praised on inquiring about relevant comorbidities, and a relevant journal article is retrieved for the student’s future studies. Teaching points regarding the Koebner phenomenon, such as that it is not an instantaneous process and comes with a differential diagnosis, are then provided.

Situation-Behavior-Impact is another teaching method developed by the Center for Creative Leadership. In this technique, one will identify what specifically happened, how the learner responded, and what occurred because of the response.10 This technique is exemplified in the following mock conversation between an attending and their resident following a challenging patient situation: “When you walked into the room and asked the patient coming in for a follow-up appointment ‘What brings you in today?,’ they immediately tensed up and responded that you should already know and check your electronic medical record. This tension could be ameliorated by reviewing the patient’s medical record and addressing what they initially presented for, followed by inquiring if there are other skin problems they want to discuss afterwards.” By identifying the cause-and-effect relationship, helpful and unhelpful responses can be identified and ways to mitigate or continue behaviors can be brainstormed.

The Learning Process

Brodell et all11 outlined techniques to augment the education process that are specific to dermatology. They recommended learning general applicable concepts instead of contextless memorization, mnemonic devices to assist memory for associations and lists, and repetition and practice of learned material. For teaching, they divided techniques into Aristotelian or Socratic; Aristotelian teaching is the formal lecture style, whereas Socratic is conversation based. Both have a place in teaching—as fundamental knowledge grows via Aristotelian teaching, critical thinking can be enhanced via the Socratic method. The authors then outlined tips to create the most conducive learning environment for students.11

Feedback is a reciprocal process with information being given and received by both the teacher and the learner. This is paramount because perfecting the art of teaching is a career-long process and can only be achieved via correction of oversights and mistakes. A questionnaire-based study found that when critiquing the teacher, a combination of self-assessment with assessment from learners was effective in stimulating the greatest level of change in the teacher.12 This finding likely is because the educator was able to see the juxtaposition of how they think they performed with how students interpreted the same situation. Another survey-based study showed that of 68 attending physicians, 28 attendings saw utility in specialized feedback training; an additional 11 attendings agreed with online modules to improve their feedback skills. A recommendation that trainees receive training on the acceptance feedback also was proposed.13 Specialized training to give and receive feedback could be initiated for both attending and resident physicians to fully create an environment emphasizing improvement and teamwork.

Final Thoughts

The art of giving and receiving feedback is a deliberate process that develops with experience and training. Because residents are early in their medical career, being familiar with techniques such as those outlined in this article can enhance teaching and the reception of feedback. Residents are in a unique position, as residency itself is a time of dramatic learning and teaching. Providing feedback gives us a way to advance medicine and better ourselves by solidifying good habits and knowledge.

Acknowledgment—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and reviewing this article.

A dermatology resident has more education and experience than a medical student or intern but less than a fellow or attending physician. Because of this position, residents have a unique opportunity to provide feedback and education to those with less knowledge and experience as a teacher and also to provide feedback to their more senior colleagues about their teaching effectiveness while simultaneously learning from them. The reciprocal exchange of information—from patients and colleagues in clinic, co-residents or attendings in lectures, or in other environments such as pathology at the microscope or skills during simulation training sessions—is the cornerstone of medical education. Being able to give effective feedback while also learning to accept it is one of the most vital skills a resident can learn to thrive in medical education.

The importance of feedback cannot be understated. The art of medicine involves the scientific knowledge needed to treat disease, as well as the social ability to educate, comfort, and heal those afflicted. Mastering this art takes a lifetime. The direct imparting of knowledge from those more experienced to those learning occurs via feedback. In addition, the desire to better oneself leads to more satisfaction with work and improved performance.1 The ability to give and receive feedback is vital for the field of dermatology and medicine in general.

Types and Implementation of Feedback

Feedback comes in many forms and can be classified via different characteristics such as formal vs informal, written vs spoken, real time vs delayed, and single observer vs pooled data. Each style of feedback has positive and negative aspects, and a feedback provider will need to weigh the pros and cons when deciding the most appropriate one. Although there is no one correct way to provide feedback, the literature shows that some forms of feedback may be more effective and better received than others. This can depend on the context of what is being evaluated.

Many dermatology residencies employ formal scheduled feedback as part of their curricula, ensuring that residents will receive feedback at preset time intervals and providing residency directors with information to assess improvement and areas where more growth is needed. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education provides a reference for programs on how to give this formal standardized feedback in The Milestones Guidebook.2 This feedback is a minimum required amount, with a survey of residents showing preference for frequent informal feedback sessions in addition to standardized formal feedback.3 Another study showed that residents want feedback that is confidential, in person, shortly after experiences, and specific to their actions.4 Medical students also voiced a need for frequent, transparent, and actionable feedback during protected, predetermined, and communicated times.5 Clearly, learners appreciate spoken intentional feedback as opposed to the traditional formal model of feedback.

Finally, a study was performed analyzing how prior generations of physician educators view millennial trainees.6 Because most current dermatology residents were born between 1981 and 1996, this study seemed to pinpoint thoughts toward teaching current residents. The study found that although negative judgments such as millennial entitlement (P<.001), impoliteness (P<.001), oversensitivity (P<.001), and inferior work ethic (P<.001) reached significance, millennial ideals of social justice (P<.001) and savviness with technology (P<.001) also were notable. Overall, millennials were thought to be good colleagues (P<.001), were equally competent to more experienced clinicians (P<.001), and would lead medicine to a good future (P=.039).6

Identifying and Maximizing the Impact of Feedback

In addition to how and when to provide feedback, there are discrepancies between attending and resident perception of what is considered feedback. This disconnect can be seen in a study of 122 respondents (67 residents and 55 attendings) that showed 31% of attendings reported giving feedback daily, as opposed to only 9% of residents who reported receiving daily feedback.4 When feedback is to be performed, it may be important to specifically announce the process so that it can be properly acknowledged.7

Beach8 provided a systematic breakdown of clinical teaching to those who may be unfamiliar with the process. This method is divided into preclinic, in-clinic, and postclinic strategies to maximize learning. The author recommended establishing the objectives of the rotation from the teacher’s perspective and inquiring about the objectives of the learner. Both perspectives should inform the lessons to be learned; for example, if a medical student expresses specific interest in psoriasis (a well-established part of a medical student curriculum), all efforts should be placed on arranging for that student to see those specific patients. Beach8 also recommended providing resources and creating a positive supportive learning environment to better utilize precious clinic time and create investment in all learning parties. The author recommended matching trainees during clinic to competence-specific challenges in clinical practice where appropriate technical skill is needed. Appropriate autonomy also is promoted, as it requires higher levels of learning and knowledge consolidation. Group discussions can be facilitated by asking questions of increasing levels of difficulty as experience increases. Finally, postclinic feedback should be timely and constructive.8

One technique discussed by Beach8 is the “1-minute preceptor plus” approach. In this approach, the teacher wants to establish 5 “micro-skills” by first getting a commitment, then checking for supportive evidence of this initial plan, teaching a general principle, reinforcing what was properly performed, and correcting errors. The “plus” comes from trying to take that lesson and apply it to a broader concept. Although this concept is meant to be used in a time-limited setting, it can be expanded to larger conversations. A common example could be made when residents teach rotating medical students through direct observation and supervision during clinic. In this hypothetical situation, the resident and medical student see a patient with erythematous silver-scaled plaques on the elbows and knees. During the patient encounter, the student then inquires about any personal history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. After leaving the examination room, the medical student asserts the diagnosis is plaque psoriasis because of the physical examination findings and distribution of lesions. A discussion about the relationship between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome commences, emphasizing the pathophysiology of type 1 helper T-cell–mediated and type 17 helper T-cell–mediated inflammation with vascular damage and growth from inflammatory cytokines.9 The student subsequently is praised on inquiring about relevant comorbidities, and a relevant journal article is retrieved for the student’s future studies. Teaching points regarding the Koebner phenomenon, such as that it is not an instantaneous process and comes with a differential diagnosis, are then provided.

Situation-Behavior-Impact is another teaching method developed by the Center for Creative Leadership. In this technique, one will identify what specifically happened, how the learner responded, and what occurred because of the response.10 This technique is exemplified in the following mock conversation between an attending and their resident following a challenging patient situation: “When you walked into the room and asked the patient coming in for a follow-up appointment ‘What brings you in today?,’ they immediately tensed up and responded that you should already know and check your electronic medical record. This tension could be ameliorated by reviewing the patient’s medical record and addressing what they initially presented for, followed by inquiring if there are other skin problems they want to discuss afterwards.” By identifying the cause-and-effect relationship, helpful and unhelpful responses can be identified and ways to mitigate or continue behaviors can be brainstormed.

The Learning Process

Brodell et all11 outlined techniques to augment the education process that are specific to dermatology. They recommended learning general applicable concepts instead of contextless memorization, mnemonic devices to assist memory for associations and lists, and repetition and practice of learned material. For teaching, they divided techniques into Aristotelian or Socratic; Aristotelian teaching is the formal lecture style, whereas Socratic is conversation based. Both have a place in teaching—as fundamental knowledge grows via Aristotelian teaching, critical thinking can be enhanced via the Socratic method. The authors then outlined tips to create the most conducive learning environment for students.11

Feedback is a reciprocal process with information being given and received by both the teacher and the learner. This is paramount because perfecting the art of teaching is a career-long process and can only be achieved via correction of oversights and mistakes. A questionnaire-based study found that when critiquing the teacher, a combination of self-assessment with assessment from learners was effective in stimulating the greatest level of change in the teacher.12 This finding likely is because the educator was able to see the juxtaposition of how they think they performed with how students interpreted the same situation. Another survey-based study showed that of 68 attending physicians, 28 attendings saw utility in specialized feedback training; an additional 11 attendings agreed with online modules to improve their feedback skills. A recommendation that trainees receive training on the acceptance feedback also was proposed.13 Specialized training to give and receive feedback could be initiated for both attending and resident physicians to fully create an environment emphasizing improvement and teamwork.

Final Thoughts

The art of giving and receiving feedback is a deliberate process that develops with experience and training. Because residents are early in their medical career, being familiar with techniques such as those outlined in this article can enhance teaching and the reception of feedback. Residents are in a unique position, as residency itself is a time of dramatic learning and teaching. Providing feedback gives us a way to advance medicine and better ourselves by solidifying good habits and knowledge.

Acknowledgment—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and reviewing this article.

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, et al. The Milestones Guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/milestonesguidebook.pdf

- Wang JV, O’Connor M, McGuinn K, et al. Feedback practices in dermatology residency programs: building a culture for millennials. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:282-283.

- Hajar T, Wanat KA, Fett N. Survey of resident physician and attending physician feedback perceptions: there is still work to be done. Dermatol Online J. 2020;25:13030/qt2sg354p6.

- Yoon J, Said JT, Thompson LL, et al. Medical student perceptions of assessment systems, subjectivity, and variability on introductory dermatology clerkships. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:232-330.

- Marka A, LeBoeuf MR, Vidal NY. Perspectives of dermatology faculty toward millennial trainees and colleagues: a national survey. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5:65-71.

- Bernard AW, Kman NE, Khandelwal S. Feedback in the emergency medicine clerkship. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:537-542.

- Beach RA. Strategies to maximise teaching in your next ambulatory clinic. Clin Teach. 2017;14:85-89.

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases part I. epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

- Olbricht SM. What makes feedback productive? Cutis. 2016;98:222-223.

- Brodell RT, Wile MZ, Chren M, et al. Learning and teaching in dermatology: a practitioner’s guide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:946-952.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, et al. Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2010;15:315-328.

- Chelliah P, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. What makes giving feedback challenging? a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD)[published online July 19, 2022]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02370-y

- Crommelinck M, Anseel F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behavior: a literature review. Med Educ. 2013;47:232-241.

- Edgar L, McLean S, Hogan SO, et al. The Milestones Guidebook. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/milestonesguidebook.pdf

- Wang JV, O’Connor M, McGuinn K, et al. Feedback practices in dermatology residency programs: building a culture for millennials. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:282-283.

- Hajar T, Wanat KA, Fett N. Survey of resident physician and attending physician feedback perceptions: there is still work to be done. Dermatol Online J. 2020;25:13030/qt2sg354p6.

- Yoon J, Said JT, Thompson LL, et al. Medical student perceptions of assessment systems, subjectivity, and variability on introductory dermatology clerkships. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:232-330.

- Marka A, LeBoeuf MR, Vidal NY. Perspectives of dermatology faculty toward millennial trainees and colleagues: a national survey. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5:65-71.

- Bernard AW, Kman NE, Khandelwal S. Feedback in the emergency medicine clerkship. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:537-542.

- Beach RA. Strategies to maximise teaching in your next ambulatory clinic. Clin Teach. 2017;14:85-89.

- Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases part I. epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

- Olbricht SM. What makes feedback productive? Cutis. 2016;98:222-223.

- Brodell RT, Wile MZ, Chren M, et al. Learning and teaching in dermatology: a practitioner’s guide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:946-952.

- Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, et al. Combined student ratings and self-assessment provide useful feedback for clinical teachers. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2010;15:315-328.

- Chelliah P, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. What makes giving feedback challenging? a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD)[published online July 19, 2022]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02370-y

RESIDENT PEARLS

- Feedback between dermatology trainees and their educators should be provided in a private and constructive way soon after the observation was performed.

- One method to improve education and feedback in a residency program is a specialty course to improve giving and receiving feedback by both residents and attending physicians.

Focus on menopause

OBG Management caught up with Drs. Jan Shifren and Genevieve Neal-Perry while they were attending the annual meeting of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), held October 12-15, 2022, in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Shifren presented on the “Ins and Outs of Hormone Therapy,” while Dr. Neal-Perry focused on “Menopause Physiology.”

Evaluating symptomatic patients for appropriate hormone therapy

OBG Management: In your presentation to the group at the NAMS meeting, you described a 51-year-old patient with the principal symptoms of frequent hot flashes and night sweats, sleep disruption, fatigue, irritability, vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia. As she reported already trying several lifestyle modification approaches, what are your questions for her to determine whether hormone therapy (HT), systemic or low-dose vaginal, is advisable?

Jan Shifren, MD: As with every patient, you need to begin with a thorough history and confirm her physical exam is up to date. If there are concerns related to genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM), then a pelvic exam is indicated. This patient is a healthy menopausal woman with bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and vaginal dryness. Sleep disruption from night sweats is likely the cause of her fatigue and irritability, and her dyspareunia due to atrophic vulvovaginal changes. The principal indication for systemic HT is bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and a healthy woman who is under age 60 or within 10 years of the onset of menopause is generally a very good candidate for hormones. For this healthy 51-year-old with bothersome VMS unresponsive to lifestyle modification, the benefits of HT should outweigh potential risks. As low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy is minimally absorbed and very safe, this would be recommended instead of systemic HT if her only menopause symptoms were vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.

HT types and formulations

OBG Management: For this patient, low-dose vaginal estrogen is appropriate. In general, how do you decide on recommendations for combination therapy or estrogen only, and what formulations and dosages do you recommend?

Dr. Shifren: Any woman with a uterus needs to take a progestogen together with estrogen to protect her uterus from estrogen-induced endometrial overgrowth. With low dose vaginal estrogen therapy, however, concurrent progestogen is not needed.

Continue to: Estrogen options...

Estrogen options. I ask my patients about their preferences, but I typically recommend transdermal or non-oral estradiol formulations for my menopausal patients. The most commonly prescribed non-oral menopausal estrogen is the patch—as they are convenient, come in a wide range of doses, and are generic and generally affordable. There are also US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved transdermal gels and creams, and a vaginal ring that provides systemic estrogen, but these options are typically more expensive than the patch. All non-oral estrogen formulations are composed of estradiol, which is especially nice for a patient preferring “bioidentical HT.”

Many of our patients like the idea that they are using “natural” HT. I inform them that bioidentical is a marketing term rather than a medical term, but if their goal is to take the same hormones that their ovaries made when they were younger, they should use FDA-approved formulations of estradiol and progesterone for their menopausal HT symptoms. I do not recommend compounded bioidentical HT due to concerns regarding product quality and safety. The combination of FDA-approved estradiol patches and oral micronized progesterone provides a high quality, carefully regulated bioidentical HT regimen. For women greatly preferring an oral estrogen, oral estradiol with micronized progesterone is an option.

In addition to patient preference for natural HT, the reasons that I encourage women to consider the estradiol transdermal patch for their menopausal HT include:

- no increased risk of venous thromboembolic events when physiologically dosed menopausal estradiol therapy is provided by a skin patch (observational data).1 With oral estrogens, even when dosed for menopause, VTE risk increases, as coagulation factors increase due to the first-pass hepatic effect. This does not occur with non-oral menopausal estrogens.

- no increased risk of gallbladder disease, which occurs with oral estrogen therapy (observational data)2

- possibly lower risk of stroke when low-dose menopausal HT is provided via skin patch (observational data)3

- convenience—the patches are changed once or twice weekly

- wide range of doses available, which optimizes identifying the lowest effective dose and decreasing the dose over time.

Progestogen options. Progestogens may be given daily or cyclically. Use of daily progestogen typically results in amenorrhea, which is preferred by most women. Cyclic use of a progestogen for 12-14 days each month results in a monthly withdrawal bleed, which is a good option for a woman experiencing bothersome breakthrough bleeding with daily progestogen. Use of a progestogen-releasing IUD is an off-label alternative for endometrial protection with menopausal HT. As discussed earlier, as many women prefer bioidentical HT, one of our preferred regimens is to provide transdermal estradiol with FDA-approved oral micronized progesterone. There are several patches that combine estradiol with a progestogen, but there is not a lot of dosing flexibility and product choice. There also is an approved product available that combines oral estradiol and micronized progesterone in one tablet.

Scheduling follow-up

OBG Management: Now that you have started the opening case patient on HT, how often are you going to monitor her for treatment?

Dr. Shifren: Women will not experience maximum efficacy for hot flash relief from their estrogen therapy for 3 months, so I typically see a patient back at 3 to 4 months to assess side effects and symptom control. I encourage women to reach out sooner if they are having a bothersome side effect. Once she is doing well on an HT regimen, we assess risks and benefits of ongoing treatment annually. The goal is to be certain she is on the lowest dose of estrogen that treats her symptoms, and we slowly decrease the estrogen dose over time.

Breast cancer risk

OBG Management: In your presentation, you mentioned that the risk of breast cancer does not increase appreciably with short-term use of HT. Is it possible to define short term?

Dr. Shifren: In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a large double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of menopausal HT, there was a slight increase in breast cancer risk after approximately 4 to 5 years of use in women using estrogen with progestogen.4 I share with patients that this increased risk is about the same as that of obesity or drinking more than 1 alcoholic beverage daily. As an increased risk of breast cancer does not occur for several years, a woman may be able to take hormones for bothersome symptoms, feel well, and slowly come off without incurring significant breast cancer risk. In the WHI, there was no increase in breast cancer risk in women without a uterus randomized to estrogen alone.

Regarding cardiovascular risk, in the WHI, an increased risk of cardiovascular events generally was not seen in healthy women younger than age 60 and within 10 years of the onset of menopause.5 Benefits of HT may not outweigh risks for women with significant underlying cardiovascular risk factors, even if they are younger and close to menopause onset.

Continue to: The importance of shared decision making...

The importance of shared decision making

Dr. Shifren: As with any important health care decision, women should be involved in an individualized discussion of risks and benefits, with shared decision making about whether HT is the right choice. Women also should be involved in ongoing decisions regarding HT formulation, dose, and duration of use.

A nonhormonal option for hot flashes

OBG Management: How many women experience VMS around the time of menopause?

Dr. Genevieve Neal-Perry, MD, PhD: About 60% to 70% of individuals will experience hot flashes around the time of the menopause.6 Of those, about 40% are what we would call moderate to severe hot flashes—which are typically the most disruptive in terms of quality of life.7 The window of time in which they are likely to have them, at typically their most intense timeframe, is 2 years before the final menstrual period and the year after.7 In terms of the average duration, however, it’s about 7 years, which is a lot longer than what we previously thought.8 Moreover, there are disparities in that women of color, particularly African American women, can have them as long as 10 years.8

OBG Management: Can you explain why the VMS occur, and specifically around the time of menopause?

Dr. Neal-Perry: For many years we did not understand the basic biology of hot flashes. When you think about it, it’s completely amazing—when half of our population experiences hot flashes, and we don’t understand why, and we don’t have therapy that specifically targets hot flashes.

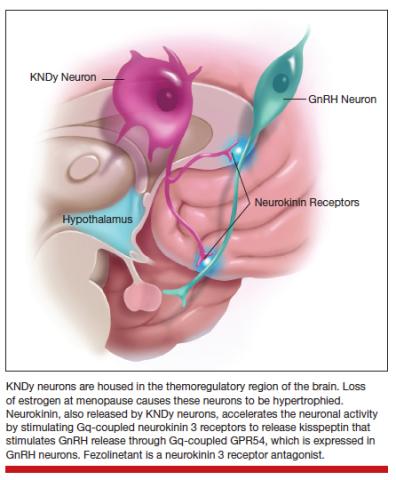

What we now know from work completed by Naomi Rance, in particular, is that a specific region of the brain, the hypothalamus, exhibited changes in number of neurons that seemed to be increased in size in menopausal people and smaller in size in people who were not menopausal.9 That started the journey to understanding the biology, and eventual mechanism, of hot flashes. It took about 10-15 years before we really began to understand why.

What we know now is that estrogen, a hormone that is made by the ovaries, activates and inactivates neurons located in the hypothalamus, a brain region that controls our thermoregulation—the way your body perceives temperature. The hypothalamus controls your response to temperature, either you experience chills or you dissipate heat by vasodilating (hot flush) and sweating.

The thermoregulatory region of the hypothalamus houses cells that receive messages from KNDy neurons, neurons also located in the hypothalamus that express kisspeptin, neurokinin, and dynorphin. Importantly, KNDy neurons express estrogen receptors. (The way that I like to think about estrogen and estrogen receptors is that estrogen is like the ball and the receptor is like the catcher’s mitt.) When estrogen interacts with this receptor, it keeps KNDy neurons quiet. But the increased variability and loss of estrogen that occurs around the time of menopause “disinhibits” KNDy neurons—meaning that they are no longer being reined in by estrogen. In response to decreased estrogen regulation, KNDy neurons become hypertrophied with neurotransmitters and more active. Specifically, KNDy neurons release neurokinin, a neuropeptide that self-stimulates KNDy neurons and activates neurons in the thermoregulatory zone of the brain—it’s a speed-forward feed-backward mechanism. The thermoregulatory neurons interpret this signal as “I feel hot,” and the body begins a series of functions to cool things down.

Continue to: Treatments that act on the thermoregulatory region

Treatments that act on the thermoregulatory region

Dr. Neal-Perry: I have described what happens in the brain around the time of menopause, and what triggers those hot flashes.

Estrogen. The reason that estrogen worked to treat the hot flashes is because estrogen inhibits and calms the neurons that become hyperactive during the menopause.

Fezolinetant. Fezolinetant is unique because it specifically targets the hormone receptor that triggers hot flashes, the neurokinin receptor. Fezolinetant is a nonhormone therapy that not only reduces the activity of KNDy neurons but also blocks the effects of neurons in the thermoregulatory zone, thereby reducing the sensation of the hot flashes. We are in such a special time in medical history for individuals who experience hot flashes because now we understand the basic biology of hot flashes, and we can generate targeted therapy to manage hot flashes—that is for both individuals who identify as women and individuals who identify as men, because both experience hot flashes.

OBG Management: Is there a particular threshold of hot flash symptoms that is considered important to treat, or is treatment based on essentially the bother to patients?

Dr. Neal-Perry: Treatment is solely based on if it bothers the patient. But we do know that people who have lots of bothersome hot flashes have a higher risk for heart disease and may have sleep disruption, reduced cognitive function, and poorer quality of life. Sleep dysfunction can impact the ability to think and function and can put those affected at increased risk for accidents.

For people who are having these symptoms that are disruptive to their life, you do want to treat them. You might say, “Well, we’ve had estrogen, why not use estrogen,” right? Well estrogen works very well, but there are lots of people who can’t use estrogen—individuals who have breast cancer, blood clotting disorders, significant heart disease, or diabetes. Then there are just some people who don’t feel comfortable using estrogen.

We have had a huge gap in care for individuals who experience hot flashes and who are ineligible for menopausal HT. While there are other nonhormonal options, they often have side effects like sexual dysfunction, hypersomnolence, or insomnia. Some people choose not to use these nonhormonal treatments because the side effects are worse for them than to trying to manage the hot flashes. The introduction to a nonhormonal therapy that is effective and does not have lots of side effects is exciting and will be welcomed by many who have not found relief.

OBG Management: Is fezolinetant available now for patients?

Dr. Neal-Perry: It is not available yet. Hopefully, it will be approved within the next year. Astellas recently completed a double blind randomized cross over design phase 3 study that found fezolinetant is highly effective for the management of hot flashes and that it has a low side effect profile.10 Fezolinetant’s most common side effect was COVID-19, a reflection of the fact that the trial was done during the COVID pandemic. The other most common side effect was headache. Everything else was minimal.

Other drugs in the same class as fezolinetant have been under development for the management of hot flashes; however, they encountered liver function challenges, and studies were stopped. Fezolinetant did not cause liver dysfunction.

Hot flash modifiers

OBG Management: Referring to that neuropathway, are there physiologic differences among women who do and do not experience hot flashes, and are there particular mechanisms that may protect patients against being bothered by hot flashes?

Dr. Neal-Perry: Well, there are some things that we can control, and there are things that we cannot control (like our genetic background). Some of the processes that are important for estrogen receptor function and estrogen metabolism, as well as some other receptor systems, can work differently. When estrogen metabolism is slightly different, it could result in reduced estrogen receptor activity and more hot flashes. Then there are some receptor polymorphisms that can increase or reduce the risk for hot flashes—the genetic piece.11

There are things that can modify your risk for hot flashes and the duration of hot flashes. Individuals who are obese or smoke may experience more hot flashes. Women of color, especially African American women, tend to have hot flashes occur earlier in their reproductive life and last for a longer duration; hot flashes may occur up to 2 years before menopause, last for more than 10 years, and be more disruptive. By contrast, Asian women tend to report fewer and less disruptive hot flashes.8

OBG Management: If fezolinetant were to be FDA approved, will there be particular patients that it will most appropriate for, since it is an estrogen alternative?

Dr. Neal-Perry: Yes, there may be different patients who might benefit from fezolinetant. This will depend on what the situation is—patients who have breast cancer, poorly controlled diabetes, or heart disease, and those patients who prefer not to use estrogen will benefit from fezolinetant, as we are going to look for other treatment options for those individuals. It will be important for medical providers to listen to their patients and understand the medical background of that individual to really define what is the best next step for the management of their hot flashes.

This is an exciting time for individuals affected by menopausal hot flashes; to understand the biology of hot flashes gives us real opportunities to bridge gaps around how to manage them. Individuals who experience hot flashes will know that they don’t have to suffer, that there are other options that are safe, that can help meet their needs and put them in a better place. ●

Excerpted from the presentation, “Do you see me? Culturally responsive care in menopause,” by Makeba Williams, MD, NCMP, at The North American Menopause Society meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, October 12-15, 2022.

Dr. Williams is Vice Chair of Professional Development and Wellness, Associate Professor, Washington University School of Medicine

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) challenged the notion that there is a universal menopausal experience.1 Up until that time, we had been using this universal experience that is based largely on the experiences of White women and applying that data to the experiences of women of color. Other research has shown that African American women have poorer quality of life and health status, and that they receive less treatment for a number of conditions.2,3

In a recent review of more than 20 years of literature, we found only 17 articles that met the inclusion criteria, reflecting the invisibility of African American women and other ethnic and racial minorities in the menopause literature and research. Key findings included that African American women1,4:

- experience an earlier age of onset of menopause

- have higher rates of premature menopause and early menopause, which is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease

- experience a longer time of the menopausal transition, with variability in the average age of menopause onset

- overall report lower rates of vaginal symptoms

- are less likely to report sleep disturbances than White women or Hispanic women, but more likely to report these symptoms than Asian women

- experience a higher prevalence, frequency, and severity of vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and were more bothered by those symptoms

− 48.4 years in the Healthy Women’s Study

− 50.9 years in the Penn Ovarian Aging Study

− 51.4 years in SWAN

- reported lower educational attainment, experiencing more socioeconomic disadvantage and exposure to more adverse life effects

- receive less treatment for VMS, hypertension, and depression, and are less likely to be prescribed statin drugs

- experience more discrimination

- use cigarettes and tobacco more, but are less likely to use alcohol and less likely to have physical activity.

Cultural influences on menopause

Im and colleagues have published many studies looking at cultural influences on African American, Hispanic, and Asian American women, and comparing them to White women.5 Notable differences were found regarding education level, family income, employment, number of children, and greater perceived health (which is associated with fewer menopausal symptoms). They identified 5 qualitative ideas: