User login

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Implantation Mycoses

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Implantation Mycoses

Implantation mycoses such as chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma are a diverse group of fungal diseases that occur when a break in the skin allows the entry of the causative fungus. These diseases disproportionately affect individuals in low- and middle-income countries causing substantial disability, decreased quality of life, and severe social stigma.1-3 Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical.

Chromoblastomycosis and mycetoma are designated as neglected tropical diseases, but research to improve their management is sparse, even compared to other neglected tropical diseases.4,5 Since there are no global diagnostic and treatment guidelines to date, we outline steps to diagnose and manage chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma.

Chromoblastomycosis

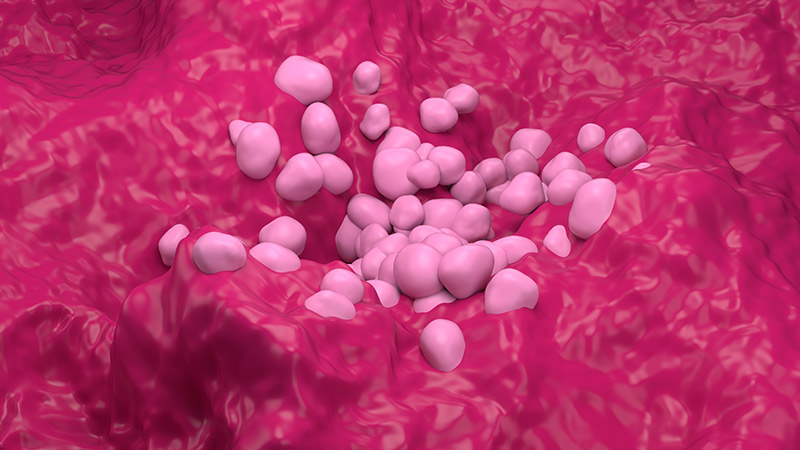

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Chromoblastomycosis is distinguished from subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis by microscopically visualizing the characteristic thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells (also known as medlar bodies, muriform cells, or sclerotic bodies).6 In phaeohyphomycosis, short hyphae and pseudohyphae plus some single cells typically are seen.

Epidemiology—Globally, the distribution and burden of chromoblastomycosis are relatively unknown. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. A literature review conducted in 2021 identified 7740 cases of chromoblastomycosis, mostly reported in South America, Africa, Central America and Mexico, and Asia.7 Most of the patients were male, and the median age was 52 years. One study found an incidence of 14.7 per 1,000,000 patients in the United States for both chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycotic abscesses (which included both skin and brain abscesses).8 Most patients were aged 65 years or older, with a higher incidence in males. Geographically, the incidence was highest in the Northeast followed by the South; patients in rural areas also had higher incidence of disease.8

Causative Organisms—Causative species cannot reliably distinguish between chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, as some species overlap. Cladophialophora carrionii, Fonsecaea species, Phialophora verrucosa species complex, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa most commonly cause chromoblastomycosis.9,10

Clinical Manifestations—Chromoblastomycosis initially manifests as a solitary erythematous macule at a site of trauma (often not recalled by the patient) that can evolve to a smooth pink papule and may progress to 1 of 5 morphologies: nodular, verrucous, tumorous, cicatricial, or plaque.6 Patients may present with more than one morphology, particularly in long-standing or advanced disease. Lesions commonly manifest on the arms and legs in otherwise healthy individuals in environments (eg, rural, agricultural) that have more opportunities for injury and exposure to the causative fungi. Affected individuals often have small black specks on the lesion surface that are visible with the naked eye.6

Diagnosis—Common differential diagnoses include cutaneous blastomycosis, fixed sporotrichosis, warty tuberculosis nocardiosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, podoconiosis, lymphatic filariasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, and psoriasis.6 Squamous cell carcinoma is both a differential diagnosis as well as a potential complication of the disease.11

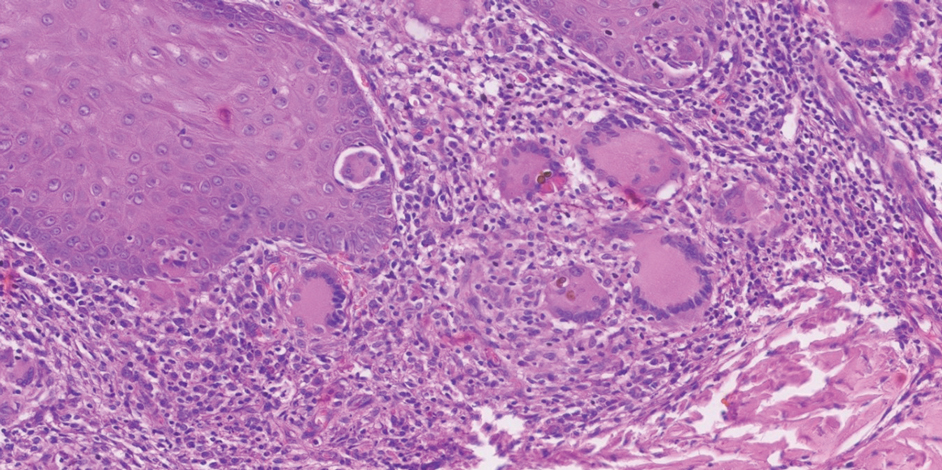

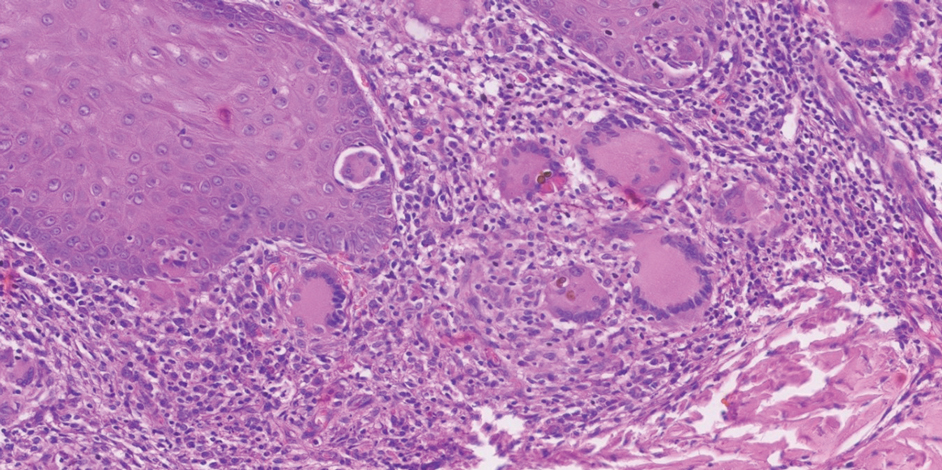

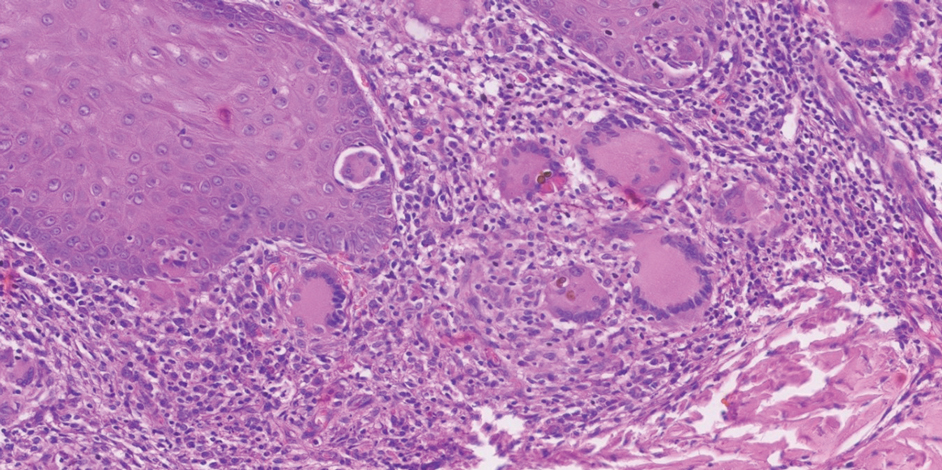

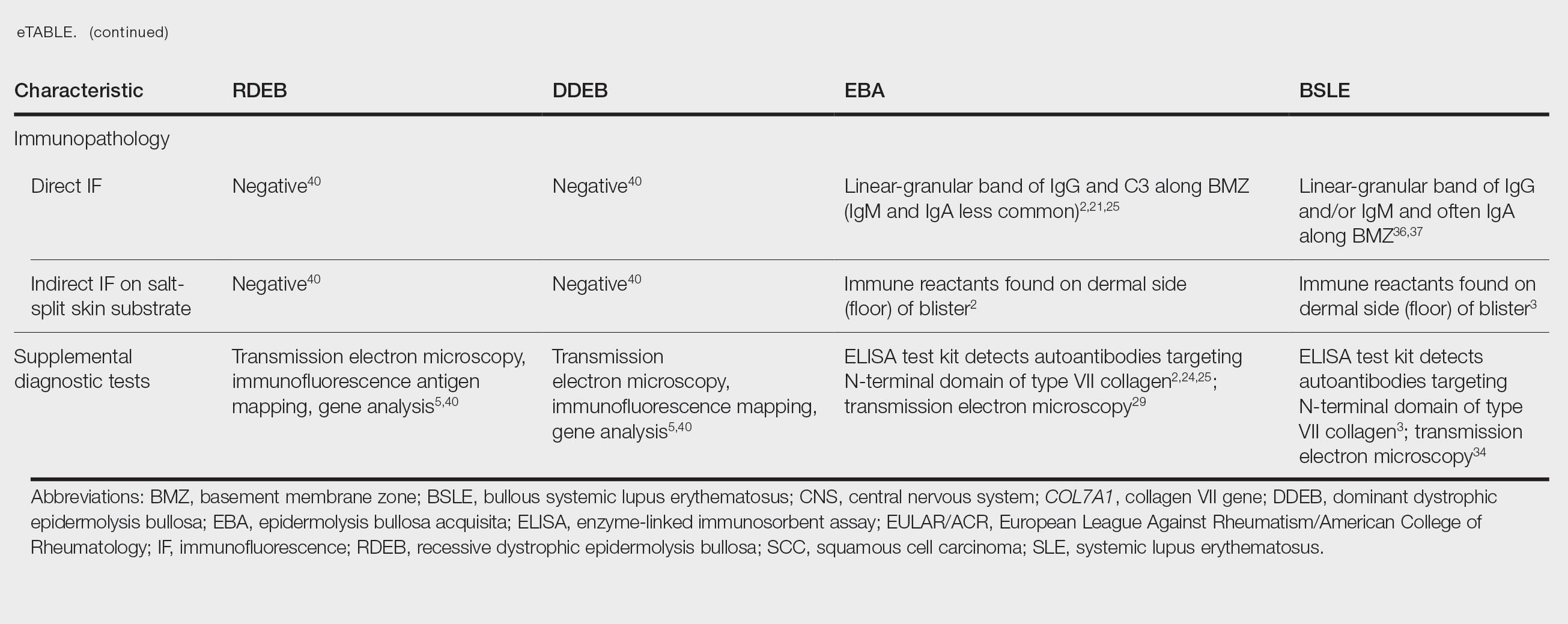

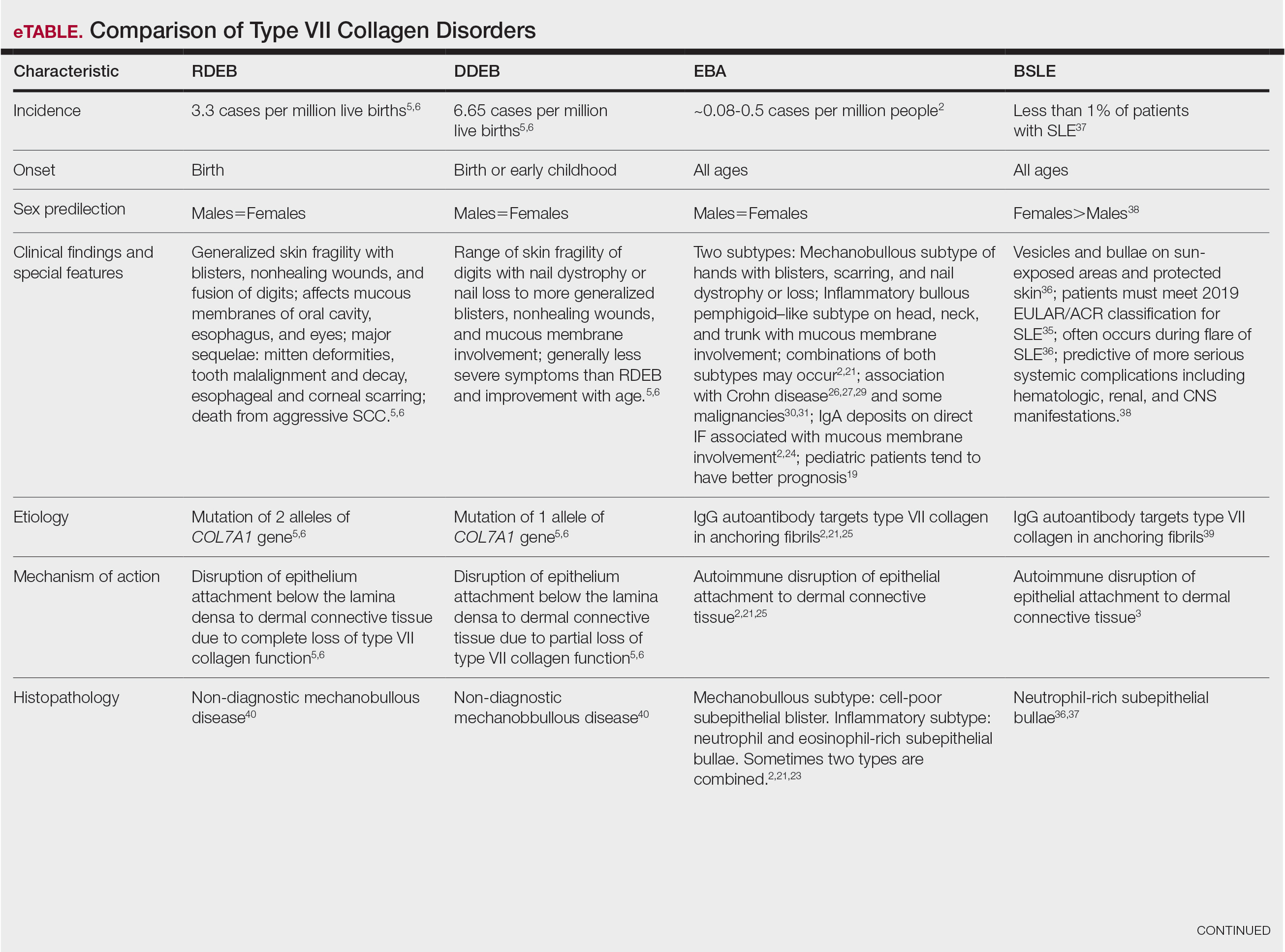

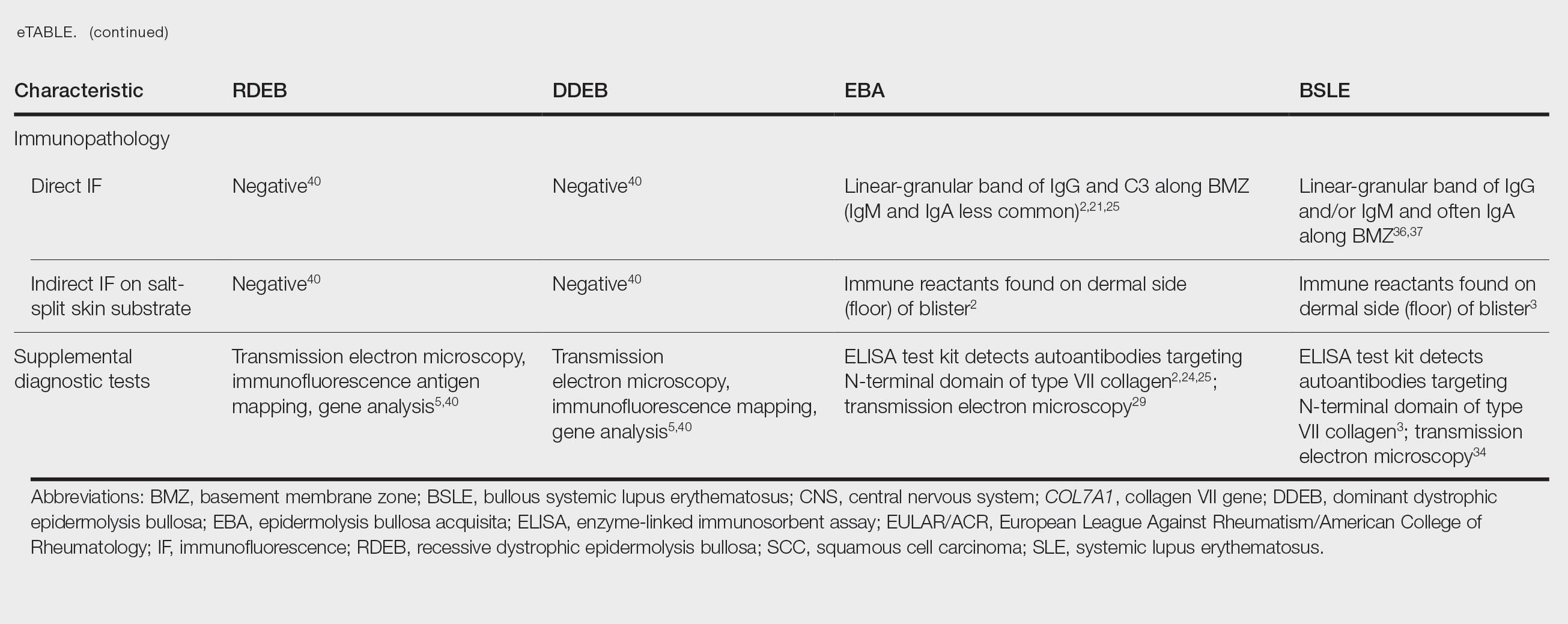

Potassium hydroxide preparation with skin scapings or a biopsy from the lesion has high sensitivity and quick turnaround times. There often is a background histopathologic reaction of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Examining samples taken from areas with the visible small black dots on the skin surface can increase the likelihood of detecting fungal elements (Figure 1). Clinicians also may choose to obtain a 6- to 8-mm deep skin biopsy from the lesion and splice it in half, with one sample sent for histopathology and the other for culture (Figure 2). Skin scrapings can be sent for culture instead. In the case of verrucous lesions, biopsy is preferred if feasible.

Treatment should not be delayed while awaiting the culture results if infection is otherwise confirmed by direct microscopy or histopathology. The treatment approach remains similar regardless of the causative species. If the culture results are positive, the causative genus can be identified by the microscopic morphology; however, molecular diagnostic tools are needed for accurate species identification.12,13

Antifungal Susceptibility Testing—For most dematiaceous fungi, interpreting minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) is challenging due to a lack of data from multicenter studies. One report examined sequential isolates of Fonsecaea pedrosoi and demonstrated both high MIC values and clinical resistance to itraconazole in some cases, likely from treatment pressure.14 Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute–approved epidemiologic cutoff values (ECVs) are established for F pedrosoi for commonly used antifungals including itraconazole (0.5 µg/mL), terbinafine (0.25 µg/mL), and posaconazole (0.5 µg/mL).15 Clinicians may choose to obtain sequential isolates for any causative fungi in recalcitrant disease to monitor for increases in MIC.

Management—In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. If antifungals are needed, itraconazole is the most commonly prescribed agent, typically at a dose of 100 to 200 mg twice daily. Terbinafine also has been used first-line at a dose of 250 to 500 mg per day. Voriconazole and posaconazole also may be suitable options for first-line or for refractory disease treatment. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy usually is several months, but many patients require years of therapy until resolution of lesions.

Clinicians can consider combination therapy with an antifungal and a topical immunomodulator such as imiquimod (applied topically 3 times per week); this combination can be considered in refractory disease and even upon initial diagnosis, especially in severe disease.17,18 Nonpharmacologic interventions such as cryotherapy, heat, and light-based therapies have been used, but outcome data are scarce.19-23

Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis is distinguished from chromoblastomycosis by short hyphae and hyphal fragments usually seen microscopically instead of visualizing thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells.6

Epidemiology—Globally, the burden and distribution of phaeohyphomycosis, including its cutaneous manifestations, are not well understood. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. Phaeohyphomycosis is a generic term used to describe infections caused by pigmented hyphal fungi that can manifest on the skin (subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis) but also can affect deep structures including the brain (systemic phaeohyphomycosis).24

Causative Organisms—Alternaria, Bipolaris, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Exophiala, and Exserohilum species most commonly cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis. Alternaria infections manifesting with skin lesions often are referred to as cutaneous alternariosis.25

Clinical Manifestations—The most common skin manifestation of phaeohyphomycosis is a subcutaneous cyst (cystic phaeohyphomycosis)(Figure 2). Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also may manifest with nodules or plaques (Figure 3). Phaeohyphomycosis appears to occur more commonly in individuals who are immunosuppressed, those in whom T-cell function is affected, in congenital immunodeficiency states (eg, individuals with CARD9 mutations).26

Diagnosis—Culture is the gold standard for confirming phaeohyphomycosis.27 For cystic phaeohyphomycosis, clinicians can consider aspiration of the cyst for direct microscopic examination and culture. Histopathology may be utilized but can have lower sensitivity in showing dematiaceous hyphae and granulomatous inflammation; using the Masson-Fontana stain for melanin can be helpful. Molecular diagnostic tools including metagenomics applied directly to the tissue may be useful but are likely to have lower sensitivity than culture and require specialist diagnostic facilities.

Management—The approaches to managing chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis are similar, though the preferred agents often differ. In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. In localized forms, itraconazole usually is used, but in those cases associated with immunodeficiency states, voriconazole may be necessary. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy may be substantially longer for chromoblastomycosis (months to years) compared to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (weeks to months), although in immunocompromised individuals treatment may be even more prolonged.

Mycetoma

Mycetoma is caused by one of several different types of fungi (eumycetoma) and bacteria (actinomycetoma) that lead to progressively debilitating yet painless subcutaneous tumorlike lesions. The lesions usually manifest on the arms and legs but can occur anywhere.

Epidemiology—Little is known about the true global burden of mycetoma, but it occurs more frequently in low-income communities in rural areas.28 A retrospective review identified 19,494 cases published from 1876 to 2019, with cases reported in 102 countries.29 The countries with the highest numbers of cases are Sudan and Mexico, where there is more information on the distribution of the disease. Cases often are reported in what is known as the mycetoma belt (between latitudes 15° south and 30° north) but are increasingly identified outside this region.28 Young men aged 20 to 40 years are most commonly affected.

In the United States, mycetoma is uncommon, but clinicians can encounter locally acquired and travel-associated cases; hence, taking a good travel history is essential. One study specifically evaluating eumycetoma found a prevalence of 5.2 per 1,000,000 patients.8 Women and those aged 65 years or older had a higher incidence. Incidence was similar across US regions, but a higher incidence was reported in nonrural areas.8

Causative Organisms—More than 60 different species of fungi can cause eumycetoma; most cases are caused by Madurella mycetomatis, Trematosphaeria grisea (formerly Madurella grisea); Pseudallescheria boydii species complex, and Falciformispora (formerly Leptosphaeria) senegalensis.30 Actinomycetoma commonly is caused by Nocardia species (Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, Nocardia transvalensis, Nocardia harenae, and Nocardia takedensis), Streptomyces somaliensis, and Actinomadura species (Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri).31

Clinical Manifestations—Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous disease with a progressive inflammatory reaction (Figures 4 and 5). Over the course of years, mycetoma progresses from small nodules to large, bone-invasive, mutilating lesions. Mycetoma manifests as a triad of painless firm subcutaneous masses, formation of multiple sinuses within the masses, and a purulent or seropurulent discharge containing sandlike visible particles (grains) that can be white, yellow, red, or black.28 Lesions usually are painless in early disease and are slowly progressive. Large lesion size, bone destruction, secondary bacterial infections, and actinomycetoma may lead to higher likelihood of pain.32

Diagnosis—Other conditions that could manifest with the same triad seen in mycetoma such as botryomycosis should be included in the differential. Other differential diagnoses include foreign body granuloma, filariasis, mycobacterial infection, skeletal tuberculosis, and yaws.

Proper treatment requires an accurate diagnosis that distinguishes actinomycetoma from eumycetoma.33 Culturing of grains obtained from deep lesion aspirates enables identification of the causative organism (Figure 6). The color of the grains may provide clues to their etiology: black grains are caused by fungus, red grains by a bacterium (A pelletieri), and pale (yellow or white) grains can be caused by either one.31Nocardia mycetoma grains are very small and usually cannot be appreciated with the naked eye. Histopathology of deep biopsy specimens (biopsy needle or surgical biopsy) stained with hematoxylin and eosin can diagnose actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. Punch biopsies often are not helpful, as the inflammatory mass is too deeply located. Deep surgical biopsy is preferred; however, species identification cannot be made without culture. Molecular tests for certain causative organisms of mycetoma have been developed but are not readily available.34,35 Currently, no serologic tests can diagnose mycetoma reliably. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose mycetoma and, with appropriate training, distinguish between actinomycetoma and eumycetoma; it also can be combined with needle aspiration for taking grain samples.36

Treatment—Treatment of mycetoma depends on identification of the causal etiology and requires long-term and expensive drug regimens. It is not possible to determine the causative organism clinically. Actinomycetoma generally responds to medical treatment, and surgery rarely is needed. The current first-line treatment is co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) in combination with amoxicillin and clavulanate acid or co-trimoxazole and amikacin for refractory disease; linezolid also may be a promising option for refractory disease.37

Eumycetoma is less responsive to medical therapies, and recurrence is common. Current recommended therapy is itraconazole for 9 to 12 months; however, cure rates ranging from 26% to 75% in combination with surgery have been reported, and fungi often can still be cultured from lesions posttreatment.38,39 Surgical excision often is used following 6 months of treatment with itraconazole to obtain better outcomes. Amputation may be required if the combination of antifungals and surgical excision fails. Fosravuconazole has shown promise in one clinical trial, but it is not approved in most countries, including the United States.39

Final Thoughts

Chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma can cause devastating disease. Patients with these conditions often are unable to carry out daily activities and experience stigma and discrimination. Limited diagnostic and treatment options hamper the ability of clinicians to respond appropriately to suspect and confirmed disease. Effectively examining the skin is the starting point for diagnosing and managing these diseases and can help clinicians to care for patients and prevent severe disease.

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-east Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2025.100561

- Abbas M, Scolding PS, Yosif AA, et al. The disabling consequences of mycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0007019. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007019

- Siregar GO, Harianja M, Rinonce HT, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a case series from Sumba, eastern Indonesia. Clin Exp Dermatol. Published online March 8, 2025. doi:10.1093/ced/llaf111

- World Health Organization. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021-2030. Published January 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- Impact Global Health. The G-FINDER 2024 neglected disease R&D report. Impact Global Health. Published January 30, 2025. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://cdn.impactglobalhealth.org/media/G-FINDER%202024_Full%20report-1.pdf

- Queiroz-Telles F, de Hoog S, Santos DWCL, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:233-276. doi:10.1128/CMR.00032-16

- Santos DWCL, de Azevedo CMPS, Vicente VA, et al. The global burden of chromoblastomycosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009611. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009611

- Gold JAW, Smith DJ, Benedict K, et al. Epidemiology of implantation mycoses in the United States: an analysis of commercial insurance claims data, 2017 to 2021. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:427-430. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.048

- Smith DJ, Queiroz-Telles F, Rabenja FR, et al. A global chromoblastomycosis strategy and development of the global chromoblastomycosis working group. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012562. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0012562

- Heath CP, Sharma PC, Sontakke S, et al. The brief case: hidden in plain sight—exophiala jeanselmei subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis of hand masquerading as a hematoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2024;62:E01068-24. doi:10.1128/jcm.01068-24

- Azevedo CMPS, Marques SG, Santos DWCL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma derived from chronic chromoblastomycosis in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1500-1504. doi:10.1093/cid/civ104

- Sun J, Najafzadeh MJ, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, et al. Molecular characterization of pathogenic members of the genus Fonsecaea using multilocus analysis. PloS One. 2012;7:E41512. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041512

- Najafzadeh MJ, Sun J, Vicente V, et al. Fonsecaea nubica sp. nov, a new agent of human chromoblastomycosis revealed using molecular data. Med Mycol. 2010;48:800-806. doi:10.3109/13693780903503081

- Andrade TS, Castro LGM, Nunes RS, et al. Susceptibility of sequential Fonsecaea pedrosoi isolates from chromoblastomycosis patients to antifungal agents. Mycoses. 2004;47:216-221. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00984.x

- Smith DJ, Melhem MSC, Dirven J, et al. Establishment of epidemiological cutoff values for Fonsecaea pedrosoi, the primary etiologic agent of chromoblastomycosis, and eight antifungal medications. J Clin Microbiol. Published online April 4, 2025. doi:10.1128/jcm.01903-24

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:884-928. doi:10.1128/CMR.00019-10

- de Sousa M da GT, Belda W, Spina R, et al. Topical application of imiquimod as a treatment for chromoblastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1734-1737. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu168

- Logan C, Singh M, Fox N, et al. Chromoblastomycosis treated with posaconazole and adjunctive imiquimod: lending innate immunity a helping hand. Open Forum Infect Dis. Published online March 14, 2023. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad124

- Castro LGM, Pimentel ERA, Lacaz CS. Treatment of chromomycosis by cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen: 15 years’ experience. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:408-412. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01532.x

- Tagami H, Ohi M, Aoshima T, et al. Topical heat therapy for cutaneous chromomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:740-741.

- Lyon JP, Pedroso e Silva Azevedo C de M, Moreira LM, et al. Photodynamic antifungal therapy against chromoblastomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:293-297. doi:10.1007/s11046-011-9434-6

- Kinbara T, Fukushiro R, Eryu Y. Chromomycosis—report of two cases successfully treated with local heat therapy. Mykosen. 1982;25:689-694. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1982.tb01944.x

- Yang Y, Hu Y, Zhang J, et al. A refractory case of chromoblastomycosis due to Fonsecaea monophora with improvement by photodynamic therapy. Med Mycol. 2012;50:649-653. doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.655258

- Sánchez-Cárdenas CD, Isa-Pimentel M, Arenas R. Phaeohyphomycosis: a review. Microbiol Res. 2023;14:1751-1763. doi:10.3390/microbiolres14040120

- Guillet J, Berkaoui I, Gargala G, et al. Cutaneous alternariosis. Mycopathologia. 2024;189:81. doi:10.1007/s11046-024-00888-5

- Wang X, Wang W, Lin Z, et al. CARD9 mutations linked to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and TH17 cell deficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:905-908. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.033

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SCA, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx200

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, et al. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:100-112. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X

- Emery D, Denning DW. The global distribution of actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:E0008397. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008397

- van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH. An updated list of eumycetoma causative agents and their differences in grain formation and treatment response. Clin Microbiol Rev. Published online May 2024. doi:10.1128/cmr.00034-23

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883. doi:10.1111/jdv.13008

- El-Amin SO, El-Amin RO, El-Amin SM, et al. Painful mycetoma: a study to understand the risk factors in patients visiting the Mycetoma Research Centre (MRC) in Khartoum, Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2025;119:145-151. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trae093

- Ahmed AA, van de Sande W, Fahal AH. Mycetoma laboratory diagnosis: review article. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005638. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005638

- Siddig EE, Ahmed A, Hassan OB, et al. Using a Madurella mycetomatis specific PCR on grains obtained via noninvasive fine needle aspirated material is more accurate than cytology. Mycoses. Published online February 5, 2023. doi:10.1111/myc.13572

- Konings M, Siddig E, Eadie K, et al. The development of a multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification reaction to detect the most common causative agents of eumycetoma. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. Published online April 30, 2025. doi:10.1007/s10096-025-05134-4

- Siddig EE, El Had Bakhait O, El nour Hussein Bahar M, et al. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology significantly improved mycetoma diagnosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1845-1850. doi:10.1111/jdv.18363

- Bonifaz A, García-Sotelo RS, Lumbán-Ramirez F, et al. Update on actinomycetoma treatment: linezolid in the treatment of actinomycetomas due to Nocardia spp and Actinomadura madurae resistant to conventional treatments. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2025;23:79-89. doi:10.1080/14787210.2024.2448723

- Chandler DJ, Bonifaz A, van de Sande WWJ. An update on the development of novel antifungal agents for eumycetoma. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1165273. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1165273

- Fahal AH, Siddig Ahmed E, Mubarak Bakhiet S, et al. Two dose levels of once-weekly fosravuconazole versus daily itraconazole, in combination with surgery, in patients with eumycetoma in Sudan: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2, proof-of-concept superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:1254-1265. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00404-3

Implantation mycoses such as chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma are a diverse group of fungal diseases that occur when a break in the skin allows the entry of the causative fungus. These diseases disproportionately affect individuals in low- and middle-income countries causing substantial disability, decreased quality of life, and severe social stigma.1-3 Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical.

Chromoblastomycosis and mycetoma are designated as neglected tropical diseases, but research to improve their management is sparse, even compared to other neglected tropical diseases.4,5 Since there are no global diagnostic and treatment guidelines to date, we outline steps to diagnose and manage chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma.

Chromoblastomycosis

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Chromoblastomycosis is distinguished from subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis by microscopically visualizing the characteristic thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells (also known as medlar bodies, muriform cells, or sclerotic bodies).6 In phaeohyphomycosis, short hyphae and pseudohyphae plus some single cells typically are seen.

Epidemiology—Globally, the distribution and burden of chromoblastomycosis are relatively unknown. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. A literature review conducted in 2021 identified 7740 cases of chromoblastomycosis, mostly reported in South America, Africa, Central America and Mexico, and Asia.7 Most of the patients were male, and the median age was 52 years. One study found an incidence of 14.7 per 1,000,000 patients in the United States for both chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycotic abscesses (which included both skin and brain abscesses).8 Most patients were aged 65 years or older, with a higher incidence in males. Geographically, the incidence was highest in the Northeast followed by the South; patients in rural areas also had higher incidence of disease.8

Causative Organisms—Causative species cannot reliably distinguish between chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, as some species overlap. Cladophialophora carrionii, Fonsecaea species, Phialophora verrucosa species complex, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa most commonly cause chromoblastomycosis.9,10

Clinical Manifestations—Chromoblastomycosis initially manifests as a solitary erythematous macule at a site of trauma (often not recalled by the patient) that can evolve to a smooth pink papule and may progress to 1 of 5 morphologies: nodular, verrucous, tumorous, cicatricial, or plaque.6 Patients may present with more than one morphology, particularly in long-standing or advanced disease. Lesions commonly manifest on the arms and legs in otherwise healthy individuals in environments (eg, rural, agricultural) that have more opportunities for injury and exposure to the causative fungi. Affected individuals often have small black specks on the lesion surface that are visible with the naked eye.6

Diagnosis—Common differential diagnoses include cutaneous blastomycosis, fixed sporotrichosis, warty tuberculosis nocardiosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, podoconiosis, lymphatic filariasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, and psoriasis.6 Squamous cell carcinoma is both a differential diagnosis as well as a potential complication of the disease.11

Potassium hydroxide preparation with skin scapings or a biopsy from the lesion has high sensitivity and quick turnaround times. There often is a background histopathologic reaction of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Examining samples taken from areas with the visible small black dots on the skin surface can increase the likelihood of detecting fungal elements (Figure 1). Clinicians also may choose to obtain a 6- to 8-mm deep skin biopsy from the lesion and splice it in half, with one sample sent for histopathology and the other for culture (Figure 2). Skin scrapings can be sent for culture instead. In the case of verrucous lesions, biopsy is preferred if feasible.

Treatment should not be delayed while awaiting the culture results if infection is otherwise confirmed by direct microscopy or histopathology. The treatment approach remains similar regardless of the causative species. If the culture results are positive, the causative genus can be identified by the microscopic morphology; however, molecular diagnostic tools are needed for accurate species identification.12,13

Antifungal Susceptibility Testing—For most dematiaceous fungi, interpreting minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) is challenging due to a lack of data from multicenter studies. One report examined sequential isolates of Fonsecaea pedrosoi and demonstrated both high MIC values and clinical resistance to itraconazole in some cases, likely from treatment pressure.14 Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute–approved epidemiologic cutoff values (ECVs) are established for F pedrosoi for commonly used antifungals including itraconazole (0.5 µg/mL), terbinafine (0.25 µg/mL), and posaconazole (0.5 µg/mL).15 Clinicians may choose to obtain sequential isolates for any causative fungi in recalcitrant disease to monitor for increases in MIC.

Management—In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. If antifungals are needed, itraconazole is the most commonly prescribed agent, typically at a dose of 100 to 200 mg twice daily. Terbinafine also has been used first-line at a dose of 250 to 500 mg per day. Voriconazole and posaconazole also may be suitable options for first-line or for refractory disease treatment. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy usually is several months, but many patients require years of therapy until resolution of lesions.

Clinicians can consider combination therapy with an antifungal and a topical immunomodulator such as imiquimod (applied topically 3 times per week); this combination can be considered in refractory disease and even upon initial diagnosis, especially in severe disease.17,18 Nonpharmacologic interventions such as cryotherapy, heat, and light-based therapies have been used, but outcome data are scarce.19-23

Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis is distinguished from chromoblastomycosis by short hyphae and hyphal fragments usually seen microscopically instead of visualizing thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells.6

Epidemiology—Globally, the burden and distribution of phaeohyphomycosis, including its cutaneous manifestations, are not well understood. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. Phaeohyphomycosis is a generic term used to describe infections caused by pigmented hyphal fungi that can manifest on the skin (subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis) but also can affect deep structures including the brain (systemic phaeohyphomycosis).24

Causative Organisms—Alternaria, Bipolaris, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Exophiala, and Exserohilum species most commonly cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis. Alternaria infections manifesting with skin lesions often are referred to as cutaneous alternariosis.25

Clinical Manifestations—The most common skin manifestation of phaeohyphomycosis is a subcutaneous cyst (cystic phaeohyphomycosis)(Figure 2). Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also may manifest with nodules or plaques (Figure 3). Phaeohyphomycosis appears to occur more commonly in individuals who are immunosuppressed, those in whom T-cell function is affected, in congenital immunodeficiency states (eg, individuals with CARD9 mutations).26

Diagnosis—Culture is the gold standard for confirming phaeohyphomycosis.27 For cystic phaeohyphomycosis, clinicians can consider aspiration of the cyst for direct microscopic examination and culture. Histopathology may be utilized but can have lower sensitivity in showing dematiaceous hyphae and granulomatous inflammation; using the Masson-Fontana stain for melanin can be helpful. Molecular diagnostic tools including metagenomics applied directly to the tissue may be useful but are likely to have lower sensitivity than culture and require specialist diagnostic facilities.

Management—The approaches to managing chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis are similar, though the preferred agents often differ. In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. In localized forms, itraconazole usually is used, but in those cases associated with immunodeficiency states, voriconazole may be necessary. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy may be substantially longer for chromoblastomycosis (months to years) compared to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (weeks to months), although in immunocompromised individuals treatment may be even more prolonged.

Mycetoma

Mycetoma is caused by one of several different types of fungi (eumycetoma) and bacteria (actinomycetoma) that lead to progressively debilitating yet painless subcutaneous tumorlike lesions. The lesions usually manifest on the arms and legs but can occur anywhere.

Epidemiology—Little is known about the true global burden of mycetoma, but it occurs more frequently in low-income communities in rural areas.28 A retrospective review identified 19,494 cases published from 1876 to 2019, with cases reported in 102 countries.29 The countries with the highest numbers of cases are Sudan and Mexico, where there is more information on the distribution of the disease. Cases often are reported in what is known as the mycetoma belt (between latitudes 15° south and 30° north) but are increasingly identified outside this region.28 Young men aged 20 to 40 years are most commonly affected.

In the United States, mycetoma is uncommon, but clinicians can encounter locally acquired and travel-associated cases; hence, taking a good travel history is essential. One study specifically evaluating eumycetoma found a prevalence of 5.2 per 1,000,000 patients.8 Women and those aged 65 years or older had a higher incidence. Incidence was similar across US regions, but a higher incidence was reported in nonrural areas.8

Causative Organisms—More than 60 different species of fungi can cause eumycetoma; most cases are caused by Madurella mycetomatis, Trematosphaeria grisea (formerly Madurella grisea); Pseudallescheria boydii species complex, and Falciformispora (formerly Leptosphaeria) senegalensis.30 Actinomycetoma commonly is caused by Nocardia species (Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, Nocardia transvalensis, Nocardia harenae, and Nocardia takedensis), Streptomyces somaliensis, and Actinomadura species (Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri).31

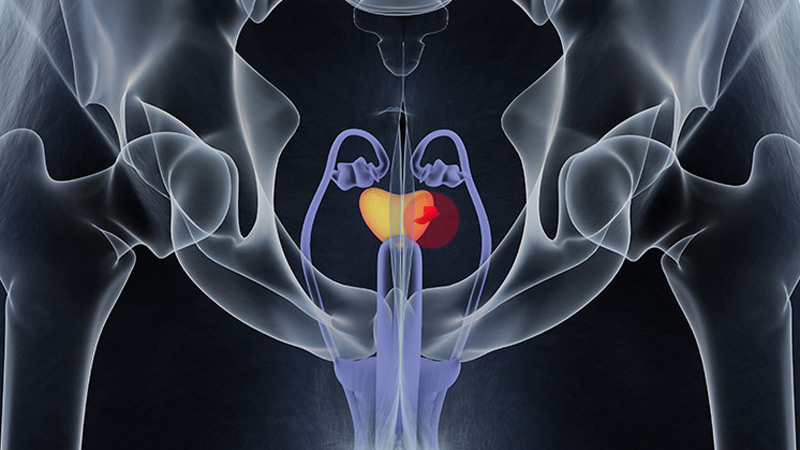

Clinical Manifestations—Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous disease with a progressive inflammatory reaction (Figures 4 and 5). Over the course of years, mycetoma progresses from small nodules to large, bone-invasive, mutilating lesions. Mycetoma manifests as a triad of painless firm subcutaneous masses, formation of multiple sinuses within the masses, and a purulent or seropurulent discharge containing sandlike visible particles (grains) that can be white, yellow, red, or black.28 Lesions usually are painless in early disease and are slowly progressive. Large lesion size, bone destruction, secondary bacterial infections, and actinomycetoma may lead to higher likelihood of pain.32

Diagnosis—Other conditions that could manifest with the same triad seen in mycetoma such as botryomycosis should be included in the differential. Other differential diagnoses include foreign body granuloma, filariasis, mycobacterial infection, skeletal tuberculosis, and yaws.

Proper treatment requires an accurate diagnosis that distinguishes actinomycetoma from eumycetoma.33 Culturing of grains obtained from deep lesion aspirates enables identification of the causative organism (Figure 6). The color of the grains may provide clues to their etiology: black grains are caused by fungus, red grains by a bacterium (A pelletieri), and pale (yellow or white) grains can be caused by either one.31Nocardia mycetoma grains are very small and usually cannot be appreciated with the naked eye. Histopathology of deep biopsy specimens (biopsy needle or surgical biopsy) stained with hematoxylin and eosin can diagnose actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. Punch biopsies often are not helpful, as the inflammatory mass is too deeply located. Deep surgical biopsy is preferred; however, species identification cannot be made without culture. Molecular tests for certain causative organisms of mycetoma have been developed but are not readily available.34,35 Currently, no serologic tests can diagnose mycetoma reliably. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose mycetoma and, with appropriate training, distinguish between actinomycetoma and eumycetoma; it also can be combined with needle aspiration for taking grain samples.36

Treatment—Treatment of mycetoma depends on identification of the causal etiology and requires long-term and expensive drug regimens. It is not possible to determine the causative organism clinically. Actinomycetoma generally responds to medical treatment, and surgery rarely is needed. The current first-line treatment is co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) in combination with amoxicillin and clavulanate acid or co-trimoxazole and amikacin for refractory disease; linezolid also may be a promising option for refractory disease.37

Eumycetoma is less responsive to medical therapies, and recurrence is common. Current recommended therapy is itraconazole for 9 to 12 months; however, cure rates ranging from 26% to 75% in combination with surgery have been reported, and fungi often can still be cultured from lesions posttreatment.38,39 Surgical excision often is used following 6 months of treatment with itraconazole to obtain better outcomes. Amputation may be required if the combination of antifungals and surgical excision fails. Fosravuconazole has shown promise in one clinical trial, but it is not approved in most countries, including the United States.39

Final Thoughts

Chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma can cause devastating disease. Patients with these conditions often are unable to carry out daily activities and experience stigma and discrimination. Limited diagnostic and treatment options hamper the ability of clinicians to respond appropriately to suspect and confirmed disease. Effectively examining the skin is the starting point for diagnosing and managing these diseases and can help clinicians to care for patients and prevent severe disease.

Implantation mycoses such as chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma are a diverse group of fungal diseases that occur when a break in the skin allows the entry of the causative fungus. These diseases disproportionately affect individuals in low- and middle-income countries causing substantial disability, decreased quality of life, and severe social stigma.1-3 Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical.

Chromoblastomycosis and mycetoma are designated as neglected tropical diseases, but research to improve their management is sparse, even compared to other neglected tropical diseases.4,5 Since there are no global diagnostic and treatment guidelines to date, we outline steps to diagnose and manage chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma.

Chromoblastomycosis

Chromoblastomycosis is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Chromoblastomycosis is distinguished from subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis by microscopically visualizing the characteristic thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells (also known as medlar bodies, muriform cells, or sclerotic bodies).6 In phaeohyphomycosis, short hyphae and pseudohyphae plus some single cells typically are seen.

Epidemiology—Globally, the distribution and burden of chromoblastomycosis are relatively unknown. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. A literature review conducted in 2021 identified 7740 cases of chromoblastomycosis, mostly reported in South America, Africa, Central America and Mexico, and Asia.7 Most of the patients were male, and the median age was 52 years. One study found an incidence of 14.7 per 1,000,000 patients in the United States for both chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycotic abscesses (which included both skin and brain abscesses).8 Most patients were aged 65 years or older, with a higher incidence in males. Geographically, the incidence was highest in the Northeast followed by the South; patients in rural areas also had higher incidence of disease.8

Causative Organisms—Causative species cannot reliably distinguish between chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, as some species overlap. Cladophialophora carrionii, Fonsecaea species, Phialophora verrucosa species complex, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa most commonly cause chromoblastomycosis.9,10

Clinical Manifestations—Chromoblastomycosis initially manifests as a solitary erythematous macule at a site of trauma (often not recalled by the patient) that can evolve to a smooth pink papule and may progress to 1 of 5 morphologies: nodular, verrucous, tumorous, cicatricial, or plaque.6 Patients may present with more than one morphology, particularly in long-standing or advanced disease. Lesions commonly manifest on the arms and legs in otherwise healthy individuals in environments (eg, rural, agricultural) that have more opportunities for injury and exposure to the causative fungi. Affected individuals often have small black specks on the lesion surface that are visible with the naked eye.6

Diagnosis—Common differential diagnoses include cutaneous blastomycosis, fixed sporotrichosis, warty tuberculosis nocardiosis, cutaneous leishmaniasis, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, podoconiosis, lymphatic filariasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, and psoriasis.6 Squamous cell carcinoma is both a differential diagnosis as well as a potential complication of the disease.11

Potassium hydroxide preparation with skin scapings or a biopsy from the lesion has high sensitivity and quick turnaround times. There often is a background histopathologic reaction of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Examining samples taken from areas with the visible small black dots on the skin surface can increase the likelihood of detecting fungal elements (Figure 1). Clinicians also may choose to obtain a 6- to 8-mm deep skin biopsy from the lesion and splice it in half, with one sample sent for histopathology and the other for culture (Figure 2). Skin scrapings can be sent for culture instead. In the case of verrucous lesions, biopsy is preferred if feasible.

Treatment should not be delayed while awaiting the culture results if infection is otherwise confirmed by direct microscopy or histopathology. The treatment approach remains similar regardless of the causative species. If the culture results are positive, the causative genus can be identified by the microscopic morphology; however, molecular diagnostic tools are needed for accurate species identification.12,13

Antifungal Susceptibility Testing—For most dematiaceous fungi, interpreting minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) is challenging due to a lack of data from multicenter studies. One report examined sequential isolates of Fonsecaea pedrosoi and demonstrated both high MIC values and clinical resistance to itraconazole in some cases, likely from treatment pressure.14 Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute–approved epidemiologic cutoff values (ECVs) are established for F pedrosoi for commonly used antifungals including itraconazole (0.5 µg/mL), terbinafine (0.25 µg/mL), and posaconazole (0.5 µg/mL).15 Clinicians may choose to obtain sequential isolates for any causative fungi in recalcitrant disease to monitor for increases in MIC.

Management—In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. If antifungals are needed, itraconazole is the most commonly prescribed agent, typically at a dose of 100 to 200 mg twice daily. Terbinafine also has been used first-line at a dose of 250 to 500 mg per day. Voriconazole and posaconazole also may be suitable options for first-line or for refractory disease treatment. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy usually is several months, but many patients require years of therapy until resolution of lesions.

Clinicians can consider combination therapy with an antifungal and a topical immunomodulator such as imiquimod (applied topically 3 times per week); this combination can be considered in refractory disease and even upon initial diagnosis, especially in severe disease.17,18 Nonpharmacologic interventions such as cryotherapy, heat, and light-based therapies have been used, but outcome data are scarce.19-23

Subcutaneous Phaeohyphomycosis

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also is caused by dematiaceous fungi that typically affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis is distinguished from chromoblastomycosis by short hyphae and hyphal fragments usually seen microscopically instead of visualizing thick-walled, single, or multicellular clusters of pigmented fungal cells.6

Epidemiology—Globally, the burden and distribution of phaeohyphomycosis, including its cutaneous manifestations, are not well understood. Infections are more common in tropical and subtropical areas but can be acquired anywhere. Phaeohyphomycosis is a generic term used to describe infections caused by pigmented hyphal fungi that can manifest on the skin (subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis) but also can affect deep structures including the brain (systemic phaeohyphomycosis).24

Causative Organisms—Alternaria, Bipolaris, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Exophiala, and Exserohilum species most commonly cause subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis. Alternaria infections manifesting with skin lesions often are referred to as cutaneous alternariosis.25

Clinical Manifestations—The most common skin manifestation of phaeohyphomycosis is a subcutaneous cyst (cystic phaeohyphomycosis)(Figure 2). Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis also may manifest with nodules or plaques (Figure 3). Phaeohyphomycosis appears to occur more commonly in individuals who are immunosuppressed, those in whom T-cell function is affected, in congenital immunodeficiency states (eg, individuals with CARD9 mutations).26

Diagnosis—Culture is the gold standard for confirming phaeohyphomycosis.27 For cystic phaeohyphomycosis, clinicians can consider aspiration of the cyst for direct microscopic examination and culture. Histopathology may be utilized but can have lower sensitivity in showing dematiaceous hyphae and granulomatous inflammation; using the Masson-Fontana stain for melanin can be helpful. Molecular diagnostic tools including metagenomics applied directly to the tissue may be useful but are likely to have lower sensitivity than culture and require specialist diagnostic facilities.

Management—The approaches to managing chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis are similar, though the preferred agents often differ. In early-stage disease, excision of the skin nodule may be curative, although concomitant treatment for several months with an antifungal is advised. In localized forms, itraconazole usually is used, but in those cases associated with immunodeficiency states, voriconazole may be necessary. Fluconazole does not have good activity against dematiaceous fungi and should be avoided.16 Topical antifungals will not reach the site of infection in adequate concentrations. Topical corticosteroids can make the disease worse and should be avoided. The duration of therapy may be substantially longer for chromoblastomycosis (months to years) compared to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (weeks to months), although in immunocompromised individuals treatment may be even more prolonged.

Mycetoma

Mycetoma is caused by one of several different types of fungi (eumycetoma) and bacteria (actinomycetoma) that lead to progressively debilitating yet painless subcutaneous tumorlike lesions. The lesions usually manifest on the arms and legs but can occur anywhere.

Epidemiology—Little is known about the true global burden of mycetoma, but it occurs more frequently in low-income communities in rural areas.28 A retrospective review identified 19,494 cases published from 1876 to 2019, with cases reported in 102 countries.29 The countries with the highest numbers of cases are Sudan and Mexico, where there is more information on the distribution of the disease. Cases often are reported in what is known as the mycetoma belt (between latitudes 15° south and 30° north) but are increasingly identified outside this region.28 Young men aged 20 to 40 years are most commonly affected.

In the United States, mycetoma is uncommon, but clinicians can encounter locally acquired and travel-associated cases; hence, taking a good travel history is essential. One study specifically evaluating eumycetoma found a prevalence of 5.2 per 1,000,000 patients.8 Women and those aged 65 years or older had a higher incidence. Incidence was similar across US regions, but a higher incidence was reported in nonrural areas.8

Causative Organisms—More than 60 different species of fungi can cause eumycetoma; most cases are caused by Madurella mycetomatis, Trematosphaeria grisea (formerly Madurella grisea); Pseudallescheria boydii species complex, and Falciformispora (formerly Leptosphaeria) senegalensis.30 Actinomycetoma commonly is caused by Nocardia species (Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, Nocardia transvalensis, Nocardia harenae, and Nocardia takedensis), Streptomyces somaliensis, and Actinomadura species (Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri).31

Clinical Manifestations—Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous disease with a progressive inflammatory reaction (Figures 4 and 5). Over the course of years, mycetoma progresses from small nodules to large, bone-invasive, mutilating lesions. Mycetoma manifests as a triad of painless firm subcutaneous masses, formation of multiple sinuses within the masses, and a purulent or seropurulent discharge containing sandlike visible particles (grains) that can be white, yellow, red, or black.28 Lesions usually are painless in early disease and are slowly progressive. Large lesion size, bone destruction, secondary bacterial infections, and actinomycetoma may lead to higher likelihood of pain.32

Diagnosis—Other conditions that could manifest with the same triad seen in mycetoma such as botryomycosis should be included in the differential. Other differential diagnoses include foreign body granuloma, filariasis, mycobacterial infection, skeletal tuberculosis, and yaws.

Proper treatment requires an accurate diagnosis that distinguishes actinomycetoma from eumycetoma.33 Culturing of grains obtained from deep lesion aspirates enables identification of the causative organism (Figure 6). The color of the grains may provide clues to their etiology: black grains are caused by fungus, red grains by a bacterium (A pelletieri), and pale (yellow or white) grains can be caused by either one.31Nocardia mycetoma grains are very small and usually cannot be appreciated with the naked eye. Histopathology of deep biopsy specimens (biopsy needle or surgical biopsy) stained with hematoxylin and eosin can diagnose actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. Punch biopsies often are not helpful, as the inflammatory mass is too deeply located. Deep surgical biopsy is preferred; however, species identification cannot be made without culture. Molecular tests for certain causative organisms of mycetoma have been developed but are not readily available.34,35 Currently, no serologic tests can diagnose mycetoma reliably. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose mycetoma and, with appropriate training, distinguish between actinomycetoma and eumycetoma; it also can be combined with needle aspiration for taking grain samples.36

Treatment—Treatment of mycetoma depends on identification of the causal etiology and requires long-term and expensive drug regimens. It is not possible to determine the causative organism clinically. Actinomycetoma generally responds to medical treatment, and surgery rarely is needed. The current first-line treatment is co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) in combination with amoxicillin and clavulanate acid or co-trimoxazole and amikacin for refractory disease; linezolid also may be a promising option for refractory disease.37

Eumycetoma is less responsive to medical therapies, and recurrence is common. Current recommended therapy is itraconazole for 9 to 12 months; however, cure rates ranging from 26% to 75% in combination with surgery have been reported, and fungi often can still be cultured from lesions posttreatment.38,39 Surgical excision often is used following 6 months of treatment with itraconazole to obtain better outcomes. Amputation may be required if the combination of antifungals and surgical excision fails. Fosravuconazole has shown promise in one clinical trial, but it is not approved in most countries, including the United States.39

Final Thoughts

Chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma can cause devastating disease. Patients with these conditions often are unable to carry out daily activities and experience stigma and discrimination. Limited diagnostic and treatment options hamper the ability of clinicians to respond appropriately to suspect and confirmed disease. Effectively examining the skin is the starting point for diagnosing and managing these diseases and can help clinicians to care for patients and prevent severe disease.

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-east Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2025.100561

- Abbas M, Scolding PS, Yosif AA, et al. The disabling consequences of mycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0007019. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007019

- Siregar GO, Harianja M, Rinonce HT, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a case series from Sumba, eastern Indonesia. Clin Exp Dermatol. Published online March 8, 2025. doi:10.1093/ced/llaf111

- World Health Organization. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021-2030. Published January 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- Impact Global Health. The G-FINDER 2024 neglected disease R&D report. Impact Global Health. Published January 30, 2025. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://cdn.impactglobalhealth.org/media/G-FINDER%202024_Full%20report-1.pdf

- Queiroz-Telles F, de Hoog S, Santos DWCL, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:233-276. doi:10.1128/CMR.00032-16

- Santos DWCL, de Azevedo CMPS, Vicente VA, et al. The global burden of chromoblastomycosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009611. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009611

- Gold JAW, Smith DJ, Benedict K, et al. Epidemiology of implantation mycoses in the United States: an analysis of commercial insurance claims data, 2017 to 2021. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:427-430. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.048

- Smith DJ, Queiroz-Telles F, Rabenja FR, et al. A global chromoblastomycosis strategy and development of the global chromoblastomycosis working group. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012562. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0012562

- Heath CP, Sharma PC, Sontakke S, et al. The brief case: hidden in plain sight—exophiala jeanselmei subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis of hand masquerading as a hematoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2024;62:E01068-24. doi:10.1128/jcm.01068-24

- Azevedo CMPS, Marques SG, Santos DWCL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma derived from chronic chromoblastomycosis in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1500-1504. doi:10.1093/cid/civ104

- Sun J, Najafzadeh MJ, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, et al. Molecular characterization of pathogenic members of the genus Fonsecaea using multilocus analysis. PloS One. 2012;7:E41512. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041512

- Najafzadeh MJ, Sun J, Vicente V, et al. Fonsecaea nubica sp. nov, a new agent of human chromoblastomycosis revealed using molecular data. Med Mycol. 2010;48:800-806. doi:10.3109/13693780903503081

- Andrade TS, Castro LGM, Nunes RS, et al. Susceptibility of sequential Fonsecaea pedrosoi isolates from chromoblastomycosis patients to antifungal agents. Mycoses. 2004;47:216-221. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00984.x

- Smith DJ, Melhem MSC, Dirven J, et al. Establishment of epidemiological cutoff values for Fonsecaea pedrosoi, the primary etiologic agent of chromoblastomycosis, and eight antifungal medications. J Clin Microbiol. Published online April 4, 2025. doi:10.1128/jcm.01903-24

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:884-928. doi:10.1128/CMR.00019-10

- de Sousa M da GT, Belda W, Spina R, et al. Topical application of imiquimod as a treatment for chromoblastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1734-1737. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu168

- Logan C, Singh M, Fox N, et al. Chromoblastomycosis treated with posaconazole and adjunctive imiquimod: lending innate immunity a helping hand. Open Forum Infect Dis. Published online March 14, 2023. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad124

- Castro LGM, Pimentel ERA, Lacaz CS. Treatment of chromomycosis by cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen: 15 years’ experience. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:408-412. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01532.x

- Tagami H, Ohi M, Aoshima T, et al. Topical heat therapy for cutaneous chromomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:740-741.

- Lyon JP, Pedroso e Silva Azevedo C de M, Moreira LM, et al. Photodynamic antifungal therapy against chromoblastomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:293-297. doi:10.1007/s11046-011-9434-6

- Kinbara T, Fukushiro R, Eryu Y. Chromomycosis—report of two cases successfully treated with local heat therapy. Mykosen. 1982;25:689-694. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1982.tb01944.x

- Yang Y, Hu Y, Zhang J, et al. A refractory case of chromoblastomycosis due to Fonsecaea monophora with improvement by photodynamic therapy. Med Mycol. 2012;50:649-653. doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.655258

- Sánchez-Cárdenas CD, Isa-Pimentel M, Arenas R. Phaeohyphomycosis: a review. Microbiol Res. 2023;14:1751-1763. doi:10.3390/microbiolres14040120

- Guillet J, Berkaoui I, Gargala G, et al. Cutaneous alternariosis. Mycopathologia. 2024;189:81. doi:10.1007/s11046-024-00888-5

- Wang X, Wang W, Lin Z, et al. CARD9 mutations linked to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and TH17 cell deficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:905-908. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.033

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SCA, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx200

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, et al. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:100-112. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X

- Emery D, Denning DW. The global distribution of actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:E0008397. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008397

- van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH. An updated list of eumycetoma causative agents and their differences in grain formation and treatment response. Clin Microbiol Rev. Published online May 2024. doi:10.1128/cmr.00034-23

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883. doi:10.1111/jdv.13008

- El-Amin SO, El-Amin RO, El-Amin SM, et al. Painful mycetoma: a study to understand the risk factors in patients visiting the Mycetoma Research Centre (MRC) in Khartoum, Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2025;119:145-151. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trae093

- Ahmed AA, van de Sande W, Fahal AH. Mycetoma laboratory diagnosis: review article. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005638. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005638

- Siddig EE, Ahmed A, Hassan OB, et al. Using a Madurella mycetomatis specific PCR on grains obtained via noninvasive fine needle aspirated material is more accurate than cytology. Mycoses. Published online February 5, 2023. doi:10.1111/myc.13572

- Konings M, Siddig E, Eadie K, et al. The development of a multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification reaction to detect the most common causative agents of eumycetoma. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. Published online April 30, 2025. doi:10.1007/s10096-025-05134-4

- Siddig EE, El Had Bakhait O, El nour Hussein Bahar M, et al. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology significantly improved mycetoma diagnosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1845-1850. doi:10.1111/jdv.18363

- Bonifaz A, García-Sotelo RS, Lumbán-Ramirez F, et al. Update on actinomycetoma treatment: linezolid in the treatment of actinomycetomas due to Nocardia spp and Actinomadura madurae resistant to conventional treatments. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2025;23:79-89. doi:10.1080/14787210.2024.2448723

- Chandler DJ, Bonifaz A, van de Sande WWJ. An update on the development of novel antifungal agents for eumycetoma. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1165273. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1165273

- Fahal AH, Siddig Ahmed E, Mubarak Bakhiet S, et al. Two dose levels of once-weekly fosravuconazole versus daily itraconazole, in combination with surgery, in patients with eumycetoma in Sudan: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2, proof-of-concept superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:1254-1265. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00404-3

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-east Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561. doi:10.1016/j.lansea.2025.100561

- Abbas M, Scolding PS, Yosif AA, et al. The disabling consequences of mycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:E0007019. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007019

- Siregar GO, Harianja M, Rinonce HT, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a case series from Sumba, eastern Indonesia. Clin Exp Dermatol. Published online March 8, 2025. doi:10.1093/ced/llaf111

- World Health Organization. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021-2030. Published January 28, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

- Impact Global Health. The G-FINDER 2024 neglected disease R&D report. Impact Global Health. Published January 30, 2025. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://cdn.impactglobalhealth.org/media/G-FINDER%202024_Full%20report-1.pdf

- Queiroz-Telles F, de Hoog S, Santos DWCL, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:233-276. doi:10.1128/CMR.00032-16

- Santos DWCL, de Azevedo CMPS, Vicente VA, et al. The global burden of chromoblastomycosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:E0009611. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009611

- Gold JAW, Smith DJ, Benedict K, et al. Epidemiology of implantation mycoses in the United States: an analysis of commercial insurance claims data, 2017 to 2021. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:427-430. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.048

- Smith DJ, Queiroz-Telles F, Rabenja FR, et al. A global chromoblastomycosis strategy and development of the global chromoblastomycosis working group. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18:e0012562. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0012562

- Heath CP, Sharma PC, Sontakke S, et al. The brief case: hidden in plain sight—exophiala jeanselmei subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis of hand masquerading as a hematoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2024;62:E01068-24. doi:10.1128/jcm.01068-24

- Azevedo CMPS, Marques SG, Santos DWCL, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma derived from chronic chromoblastomycosis in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1500-1504. doi:10.1093/cid/civ104

- Sun J, Najafzadeh MJ, Gerrits van den Ende AHG, et al. Molecular characterization of pathogenic members of the genus Fonsecaea using multilocus analysis. PloS One. 2012;7:E41512. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041512

- Najafzadeh MJ, Sun J, Vicente V, et al. Fonsecaea nubica sp. nov, a new agent of human chromoblastomycosis revealed using molecular data. Med Mycol. 2010;48:800-806. doi:10.3109/13693780903503081

- Andrade TS, Castro LGM, Nunes RS, et al. Susceptibility of sequential Fonsecaea pedrosoi isolates from chromoblastomycosis patients to antifungal agents. Mycoses. 2004;47:216-221. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00984.x

- Smith DJ, Melhem MSC, Dirven J, et al. Establishment of epidemiological cutoff values for Fonsecaea pedrosoi, the primary etiologic agent of chromoblastomycosis, and eight antifungal medications. J Clin Microbiol. Published online April 4, 2025. doi:10.1128/jcm.01903-24

- Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:884-928. doi:10.1128/CMR.00019-10

- de Sousa M da GT, Belda W, Spina R, et al. Topical application of imiquimod as a treatment for chromoblastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1734-1737. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu168

- Logan C, Singh M, Fox N, et al. Chromoblastomycosis treated with posaconazole and adjunctive imiquimod: lending innate immunity a helping hand. Open Forum Infect Dis. Published online March 14, 2023. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad124

- Castro LGM, Pimentel ERA, Lacaz CS. Treatment of chromomycosis by cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen: 15 years’ experience. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:408-412. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01532.x

- Tagami H, Ohi M, Aoshima T, et al. Topical heat therapy for cutaneous chromomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:740-741.

- Lyon JP, Pedroso e Silva Azevedo C de M, Moreira LM, et al. Photodynamic antifungal therapy against chromoblastomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:293-297. doi:10.1007/s11046-011-9434-6

- Kinbara T, Fukushiro R, Eryu Y. Chromomycosis—report of two cases successfully treated with local heat therapy. Mykosen. 1982;25:689-694. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1982.tb01944.x

- Yang Y, Hu Y, Zhang J, et al. A refractory case of chromoblastomycosis due to Fonsecaea monophora with improvement by photodynamic therapy. Med Mycol. 2012;50:649-653. doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.655258

- Sánchez-Cárdenas CD, Isa-Pimentel M, Arenas R. Phaeohyphomycosis: a review. Microbiol Res. 2023;14:1751-1763. doi:10.3390/microbiolres14040120

- Guillet J, Berkaoui I, Gargala G, et al. Cutaneous alternariosis. Mycopathologia. 2024;189:81. doi:10.1007/s11046-024-00888-5

- Wang X, Wang W, Lin Z, et al. CARD9 mutations linked to subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis and TH17 cell deficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:905-908. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.033

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SCA, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx200

- Zijlstra EE, van de Sande WWJ, Welsh O, et al. Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:100-112. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X

- Emery D, Denning DW. The global distribution of actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:E0008397. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008397

- van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH. An updated list of eumycetoma causative agents and their differences in grain formation and treatment response. Clin Microbiol Rev. Published online May 2024. doi:10.1128/cmr.00034-23

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883. doi:10.1111/jdv.13008

- El-Amin SO, El-Amin RO, El-Amin SM, et al. Painful mycetoma: a study to understand the risk factors in patients visiting the Mycetoma Research Centre (MRC) in Khartoum, Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2025;119:145-151. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trae093

- Ahmed AA, van de Sande W, Fahal AH. Mycetoma laboratory diagnosis: review article. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005638. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005638

- Siddig EE, Ahmed A, Hassan OB, et al. Using a Madurella mycetomatis specific PCR on grains obtained via noninvasive fine needle aspirated material is more accurate than cytology. Mycoses. Published online February 5, 2023. doi:10.1111/myc.13572

- Konings M, Siddig E, Eadie K, et al. The development of a multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification reaction to detect the most common causative agents of eumycetoma. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. Published online April 30, 2025. doi:10.1007/s10096-025-05134-4

- Siddig EE, El Had Bakhait O, El nour Hussein Bahar M, et al. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology significantly improved mycetoma diagnosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1845-1850. doi:10.1111/jdv.18363

- Bonifaz A, García-Sotelo RS, Lumbán-Ramirez F, et al. Update on actinomycetoma treatment: linezolid in the treatment of actinomycetomas due to Nocardia spp and Actinomadura madurae resistant to conventional treatments. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2025;23:79-89. doi:10.1080/14787210.2024.2448723

- Chandler DJ, Bonifaz A, van de Sande WWJ. An update on the development of novel antifungal agents for eumycetoma. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1165273. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1165273

- Fahal AH, Siddig Ahmed E, Mubarak Bakhiet S, et al. Two dose levels of once-weekly fosravuconazole versus daily itraconazole, in combination with surgery, in patients with eumycetoma in Sudan: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2, proof-of-concept superiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:1254-1265. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00404-3

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Implantation Mycoses

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Implantation Mycoses

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis, subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, and mycetoma are implantation mycoses that cause substantial morbidity, decreased quality of life, and social stigma.

- Consider obtaining a biopsy of suspected chromoblastomycosis and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis to confirm infection while sending half of the sample for culture for organism identification.

- Distinguishing between actinomycetoma (caused by filamentous bacteria) and eumycetoma (caused by fungi) is critical for appropriate mycetoma treatment.

From Refractory to Responsive: The Expanding Therapeutic Landscape of Prurigo Nodularis

From Refractory to Responsive: The Expanding Therapeutic Landscape of Prurigo Nodularis

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic, severely pruritic neuroimmunologic skin disorder characterized by multiple firm hyperkeratotic nodules and intense pruritus, often leading to considerable impairment in quality of life and increased rates of depression and anxiety.1 It is considered difficult to treat due to its complex pathogenesis, the severity and chronicity of pruritus, and the limited efficacy of conventional therapies.2,3 The disease is driven by a self-perpetuating itch-scratch cycle, underpinned by dysregulation of both immune and neural pathways including type 2 (interleukin [IL] 4, IL-13, IL-31), Th17, and Th22 cytokines as well as neuropeptides and altered cutaneous nerve architecture.1,3 This results in persistent severe pruritus and nodular lesions that are highly refractory to standard treatments.1 Conventional therapies (eg, locally acting agents, phototherapy, and systemic immunomodulators and neuromodulators) have varied efficacy and notable adverse effect profiles.3 While the approval of targeted biologics has transformed the therapeutic landscape, several other treatment options also are being explored in clinical trials. Herein, we review all recently approved therapies as well as emerging treatments currently under investigation.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab, the first therapy for PN approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022—is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, key drivers of type 2 inflammation implicated in PN pathogenesis.4,5 In 2 pivotal phase 3 randomized controlled trials (LIBERTY-PN PRIME and PRIME2),5 dupilumab demonstrated notable efficacy in adults with moderate to severe PN. A reduction of 4 points or more on the Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) was achieved by 60.0% (45/75) of patients treated with dupilumab at week 24 compared with 18.4% (14/76) receiving placebo in the PRIME trial. In PRIME2, the same outcome was achieved by 37.2% (29/78) of patients receiving dupilumab at week 12 compared with 22.0% (18/82) of patients receiving placebo.5 Dupilumab also led to a greater proportion of patients achieving a substantial reduction in nodule count (≤5 nodules) and improved quality of life compared with placebo.5,6 The safety profile of dupilumab for treatment of PN was favorable and consistent with prior experience in atopic dermatitis; conjunctivitis was the most common adverse event.5,6

Nemolizumab

Nemolizumab, an IL-31 receptor A antagonist, is the most recent agent approved by the FDA for PN in 2024.7 In the OLYMPIA 1 and OLYMPIA 2 phase 3 trials,8 nemolizumab produced a clinically meaningful reduction in itch (defined as a ≥4-point improvement in the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale score) in 56.3% (103/183) of patients at week 16 compared with 20.9% (19/91) receiving placebo. Additionally, 37.7% (69/183) of patients receiving nemolizumab achieved clear or almost clear skin (Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 with a ≥2-point reduction) vs 11.0% with placebo (both P<.001). Benefits were observed as early as week 4, including rapid improvements in itch, sleep disturbance, and nodule count.8 Nemolizumab also improved quality of life and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression. The safety profile was favorable, with headache and atopic dermatitis the most common adverse events; serious adverse events were infrequent and similar between groups.8

Abrocitinib

Abrocitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, is an investigational therapy for PN and currently has not been approved by the FDA for this indication. In a phase 2 open-label trial, abrocitinib 200 mg daily for 12 weeks led to a 78.3% reduction in weekly Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale scores in PN, with 80.0% (8/10) of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement of 4 points or higher. Nodule counts and quality of life also improved, with an onset of itch relief as early as week 2. The safety profile was favorable, with acneform eruptions the most common adverse event and no serious adverse events reported9; however, these results are based on small, nonrandomized studies and require confirmation in larger randomized controlled trials before abrocitinib can be considered a standard therapy for PN.

Cryosim-1

Transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) is a cold-sensing ion channel found in unmyelinated sensory neurons within the dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia.10 It is activated by cool temperatures (15-28 °C) and compounds such as menthol, leading to calcium influx and a cooling sensation. In a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial, researchers investigated the efficacy of cryosim-1 (a synthetic TRPM8 agonist) in treating PN.10 Thirty patients were enrolled, with 18 (60.0%) receiving cryosim-1 and 12 (40.0%) receiving placebo over 8 weeks. By week 8, cryosim-1 significantly reduced itch severity (mean numerical rating scale score postapplication, 2.8 vs 4.3; P=.031) and improved sleep disturbances (2.2 vs 4.2; P=.031) compared to placebo. Patients reported higher satisfaction with itch relief, and no adverse effects were observed. The study concluded that cryosim-1 is a safe, effective topical therapy for PN, likely working by interrupting the itch-scratch cycle and potentially modulating inflammatory pathways involved in chronic itch.10

Nalbuphine

Nalbuphine is a κ opioid receptor agonist and μ opioid receptor antagonist that has been investigated for the treatment of PN.11 In a phase 2 randomized controlled trial, oral nalbuphine extended release (NAL-ER) 162 mg twice daily provided measurable antipruritic efficacy, with 44.4% (8/18) of patients achieving at least a 30% reduction in 7-day WI-NRS at week 10 compared with 36.4% (8/22) in the placebo group. Among those who completed the study, 66.7% (8/12) of patients receiving NAL-ER 162 mg achieved significant itch reduction vs 40% (8/20) receiving placebo (P=.03). At least a 50% reduction in WI-NRS was achieved by 33.3% (6/18) of patients receiving NAL-ER 162 mg twice daily. Extended open-label treatment was associated with further improvements in itch and lesion activity. Adverse events were mostly mild to moderate (eg, nausea, dizziness, headache, and fatigue) and occurred during dose titration. Physiologic opioid withdrawal symptoms were limited and resolved within a few days of discontinuing the medication.11

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, PN remains one of the most challenging chronic dermatologic conditions to manage and is driven by a complex interplay of neuroimmune mechanisms and resistance to many conventional therapies. The approval of dupilumab and nemolizumab has marked a pivotal shift in the therapeutic landscape, offering hope to patients who previously had limited options5,8; however, the burden of PN remains substantial, and many patients continue to experience relentless itch, poor sleep, and reduced quality of life.1 Emerging therapies such as TRPM8 agonists, Janus kinase inhibitors, and opioid modulators represent promising additions to the treatment options, targeting novel pathways beyond traditional immunosuppression.9-11