User login

Aggregate response benefit in skin clearance and itch reduction favor upadacitinib over dupilumab in AD

Key clinical point: The overall improvement in skin clearance and itch reduction suggested a preference for 30 mg upadacitinib over dupilumab and that for 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib over placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 24, the aggregate response benefit for skin clearance and itch, respectively, was 32.5% and 25.8% higher with 30 mg upadacitinib vs dupilumab. The benefit favored upadacitinib over dupilumab as early as week 4. Moreover, 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib showed similar benefits over placebo.

Study details: This post hoc analysis of the data from phase 3 studies (Heads Up, Measure Up 1, and Measure Up 2) included 2356 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received upadacitinib, dupilumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie. Five authors declared being employees of or owning stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors declared being consultants, speakers, or advisors of or having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Aggregate response benefit in skin clearance and itch reduction with upadacitinib or dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2023 (Dec 18). doi: 10.1089/derm.2023.0153

Key clinical point: The overall improvement in skin clearance and itch reduction suggested a preference for 30 mg upadacitinib over dupilumab and that for 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib over placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 24, the aggregate response benefit for skin clearance and itch, respectively, was 32.5% and 25.8% higher with 30 mg upadacitinib vs dupilumab. The benefit favored upadacitinib over dupilumab as early as week 4. Moreover, 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib showed similar benefits over placebo.

Study details: This post hoc analysis of the data from phase 3 studies (Heads Up, Measure Up 1, and Measure Up 2) included 2356 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received upadacitinib, dupilumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie. Five authors declared being employees of or owning stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors declared being consultants, speakers, or advisors of or having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Aggregate response benefit in skin clearance and itch reduction with upadacitinib or dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2023 (Dec 18). doi: 10.1089/derm.2023.0153

Key clinical point: The overall improvement in skin clearance and itch reduction suggested a preference for 30 mg upadacitinib over dupilumab and that for 15 mg or 30 mg upadacitinib over placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 24, the aggregate response benefit for skin clearance and itch, respectively, was 32.5% and 25.8% higher with 30 mg upadacitinib vs dupilumab. The benefit favored upadacitinib over dupilumab as early as week 4. Moreover, 15 and 30 mg upadacitinib showed similar benefits over placebo.

Study details: This post hoc analysis of the data from phase 3 studies (Heads Up, Measure Up 1, and Measure Up 2) included 2356 patients with moderate-to-severe AD who received upadacitinib, dupilumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by AbbVie. Five authors declared being employees of or owning stock or stock options in AbbVie. Several authors declared being consultants, speakers, or advisors of or having other ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Aggregate response benefit in skin clearance and itch reduction with upadacitinib or dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2023 (Dec 18). doi: 10.1089/derm.2023.0153

Rademikibart shows promise in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Rademikibart administered at 2-week (Q2W) and 4-week (Q4W) intervals was well-tolerated and effective in improving the overall symptoms in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, the least squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores with 300 mg Q2W (−63.0%; P = .0007), 150 mg Q2W (−57.6%; P = .0067), and 300 mg Q4W (−63.5%; P = .0004) rademikibart were significantly higher than that with placebo (−39.7%). Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar with rademikibart (48.2%) and placebo (53.6%).

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 226 anti-interleukin (IL)-4Ra/IL-13 treatment-naive adults with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to receive rademikibart (300 mg Q2W, 150 mg Q2W, or 300 mg Q4W) or placebo for 16 weeks following a 600 mg loading dose of rademikibart or placebo, respectively, on day 1.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Connect Biopharma. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Connect Biopharma. The other authors declared being consultants of or having other ties with various sources, including Connect Biopharma.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Efficacy and safety of rademikibart (CBP-201), a next-generation monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4Rα, in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 2 randomized trial (CBP-201-WW001). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 (Dec 27). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.11.924

Key clinical point: Rademikibart administered at 2-week (Q2W) and 4-week (Q4W) intervals was well-tolerated and effective in improving the overall symptoms in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, the least squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores with 300 mg Q2W (−63.0%; P = .0007), 150 mg Q2W (−57.6%; P = .0067), and 300 mg Q4W (−63.5%; P = .0004) rademikibart were significantly higher than that with placebo (−39.7%). Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar with rademikibart (48.2%) and placebo (53.6%).

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 226 anti-interleukin (IL)-4Ra/IL-13 treatment-naive adults with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to receive rademikibart (300 mg Q2W, 150 mg Q2W, or 300 mg Q4W) or placebo for 16 weeks following a 600 mg loading dose of rademikibart or placebo, respectively, on day 1.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Connect Biopharma. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Connect Biopharma. The other authors declared being consultants of or having other ties with various sources, including Connect Biopharma.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Efficacy and safety of rademikibart (CBP-201), a next-generation monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4Rα, in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 2 randomized trial (CBP-201-WW001). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 (Dec 27). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.11.924

Key clinical point: Rademikibart administered at 2-week (Q2W) and 4-week (Q4W) intervals was well-tolerated and effective in improving the overall symptoms in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, the least squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores with 300 mg Q2W (−63.0%; P = .0007), 150 mg Q2W (−57.6%; P = .0067), and 300 mg Q4W (−63.5%; P = .0004) rademikibart were significantly higher than that with placebo (−39.7%). Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar with rademikibart (48.2%) and placebo (53.6%).

Study details: This phase 2 trial included 226 anti-interleukin (IL)-4Ra/IL-13 treatment-naive adults with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1) to receive rademikibart (300 mg Q2W, 150 mg Q2W, or 300 mg Q4W) or placebo for 16 weeks following a 600 mg loading dose of rademikibart or placebo, respectively, on day 1.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Connect Biopharma. Ten authors declared being employees or shareholders of Connect Biopharma. The other authors declared being consultants of or having other ties with various sources, including Connect Biopharma.

Source: Silverberg JI et al. Efficacy and safety of rademikibart (CBP-201), a next-generation monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4Rα, in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 2 randomized trial (CBP-201-WW001). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 (Dec 27). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2023.11.924

Interim analysis confirms the safety and efficacy of dupilumab in atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to a rapid improvement in disease control that was sustained through 2 years and showed an acceptable safety profile in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Dupilumab led to an improvement in the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score at 3 months (5.5) and 24 months (2.6) compared with baseline (16.1), with a mean absolute change from baseline to 24 months being −14.0. No new safety signals were observed.

Study details: Findings are from a 2-year interim analysis of real-world data from the PROSE registry study including 764 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (age ≥ 12 years) who initiated dupilumab.

Disclosures: The PROSE registry is sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in Sanofi or Regeneron. The other authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for or receiving speaker or investigator fees from Sanofi, Regeneron, and others.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Real-world effectiveness of dupilumab in adult and adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis: 2-year Interim data from the PROSE registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024 (Jan 4). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01061-4

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to a rapid improvement in disease control that was sustained through 2 years and showed an acceptable safety profile in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Dupilumab led to an improvement in the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score at 3 months (5.5) and 24 months (2.6) compared with baseline (16.1), with a mean absolute change from baseline to 24 months being −14.0. No new safety signals were observed.

Study details: Findings are from a 2-year interim analysis of real-world data from the PROSE registry study including 764 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (age ≥ 12 years) who initiated dupilumab.

Disclosures: The PROSE registry is sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in Sanofi or Regeneron. The other authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for or receiving speaker or investigator fees from Sanofi, Regeneron, and others.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Real-world effectiveness of dupilumab in adult and adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis: 2-year Interim data from the PROSE registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024 (Jan 4). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01061-4

Key clinical point: Dupilumab led to a rapid improvement in disease control that was sustained through 2 years and showed an acceptable safety profile in adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Dupilumab led to an improvement in the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score at 3 months (5.5) and 24 months (2.6) compared with baseline (16.1), with a mean absolute change from baseline to 24 months being −14.0. No new safety signals were observed.

Study details: Findings are from a 2-year interim analysis of real-world data from the PROSE registry study including 764 patients with moderate-to-severe AD (age ≥ 12 years) who initiated dupilumab.

Disclosures: The PROSE registry is sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Three authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in Sanofi or Regeneron. The other authors declared serving as consultants, investigators, or advisory board members for or receiving speaker or investigator fees from Sanofi, Regeneron, and others.

Source: Simpson EL et al. Real-world effectiveness of dupilumab in adult and adolescent patients with atopic dermatitis: 2-year Interim data from the PROSE registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024 (Jan 4). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-01061-4

Atopic dermatitis not linked with increased venous thromboembolism risk

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

Atopic dermatitis not linked with increased venous thromboembolism risk

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

Key clinical point: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with a lower risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) than several rheumatologic and gastrointestinal immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).

Major finding: Patients with AD vs AD-matched control individuals did not have a higher risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.90-1.02). Compared with patients having AD, those with Crohn’s disease (aHR 1.71; 95% CI 1.47-1.99), rheumatoid arthritis (aHR 1.57; 95% CI 1.43-1.72), ulcerative colitis (aHR 1.84; 95% CI 1.63-2.09), and ankylosing spondylitis (aHR 1.45; 95% CI 1.03-2.03) had higher risks for VTE.

Study details: This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 2,061,222 adult patients with IMID, including 1,098,633 patients with AD who were matched with 1,098,633 control individuals without IMID.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. JF Merola declared being a consultant or investigator for AbbVie and others. The other authors declared being current or former employees of or owning stocks or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Merola JF et al. Venous thromboembolism risk is lower in patients with atopic dermatitis than other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective, observational, comparative cohort study using US claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Dec 23). doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.027

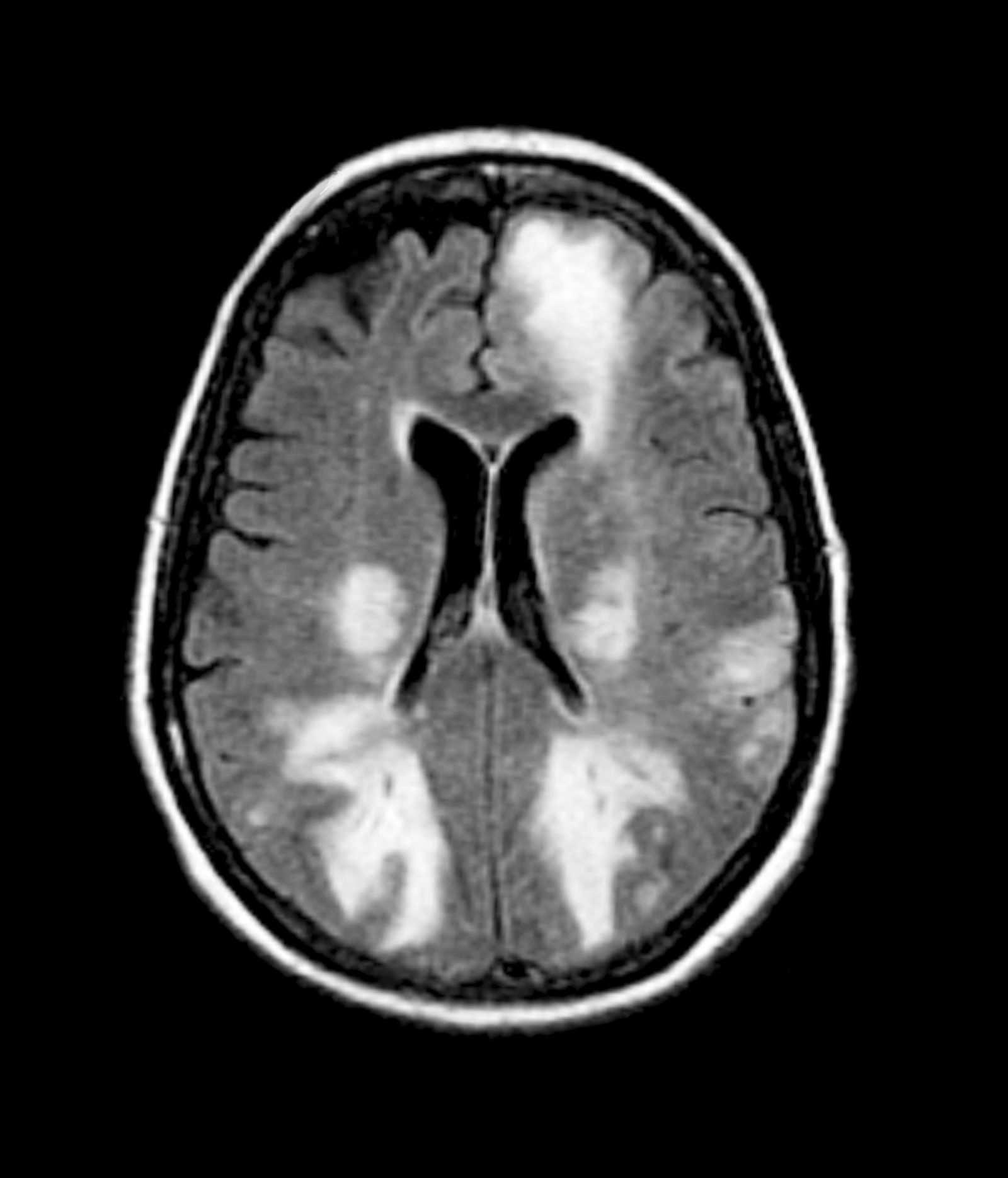

Chest pain and shortness of breath

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

In a lifelong smoker, a tumor in the periphery of the lung and histology showing glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation is most likely large cell carcinoma, a type of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Although small cell lung cancer is also associated with smoking, histology typically demonstrates highly cellular aspirates with small blue cells with very scant or null cytoplasm, loosely arranged or in a syncytial pattern. Bronchial adenoma is unlikely, given the patient's unintentional weight loss and fatigue over the past few months. Mesothelioma is most associated with asbestos exposure and is found in the lung pleura, which typically presents with pleural effusion.

Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths in the US, second only to prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women; approximately 85% of all lung cancers are classified as NSCLC. Histologically, NSCLC is further categorized into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). When a patient presents with intrathoracic symptoms (including cough, chest pain, wheezing, or dyspnea) and a pulmonary nodule on chest radiography, NSCLC is typically suspected as a possible diagnosis. Smoking is the most common cause of this lung cancer (78% in men, 90% in women).

Several methods confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC, including bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, mediastinoscopy, thoracentesis, thoracoscopy, and transthoracic needle biopsy. Which method is chosen depends on the primary lesion location and accessibility. Histologic evaluation helps differentiate between the various subtypes of NSCLC. LCC is a subset of NSCLC that is a diagnosis of exclusion. Histologically, LCC is poorly differentiated, and 90% of cases will show squamous, glandular, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

When first diagnosed with NSCLC, 20% of patients have cancer confined to a specific area, 25% of patients have cancer that has spread to nearby areas, and 55% of patients have cancer that has spread to distant body parts. The specific symptoms experienced by patients will vary depending on the location of the cancer. The prognosis for NSCLC depends on the staging of the tumor, nodes, and metastases, the patient's performance status, and any existing health conditions. In the US, the 5-year relative survival rate is 61.2% for localized disease, 33.5% for regional disease, and 7.0% for disease with distant metastases.

Treatment of NSCLC also varies according to the patient's functional status, tumor stage, molecular characteristics, and comorbidities. Generally, patients with stage I, II, or III NSCLC are treated with the intent to cure, which can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combined approach. Lobectomy or resection is generally accepted as an approach for surgical intervention on early-stage NSCLC; however, for stages higher than IB (including stage II/III), patients are recommended to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with stage IV disease (or recurrence after initial management) are typically treated with systemic therapy or should be considered for palliative treatment to improve quality of life and overall survival.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old man presents to his primary care physician with a persistent cough, dyspnea, unintentional weight loss, and fatigue over the past few months. He has a history of smoking for 30 years but quit 5 years ago. He also reports occasional chest pain and shortness of breath during physical activities. Physical examination reveals crackles in the middle lobe of the right lung. The patient occasionally coughs up blood. Chest radiography shows a large mass in the right lung, and a subsequent CT scan confirms a large peripheral mass of solid attenuation with an irregular margin. The patient undergoes thoracoscopy to obtain a biopsy sample from the tumor for further analysis. The biopsy reveals glandular cells with some neuroendocrine differentiation.

Preventing ASCVD Events: Using Coronary Artery Calcification Scores to Personalize Risk and Guide Statin Therapy

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality, and cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor. Several randomized clinical trials have shown that lung cancer screening (LCS) with nonelectrocardiogram (ECG)-gated low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces both lung cancer and all-cause mortality.1,2 Hence, the US Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening with LDCT in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.3

Smoking is also an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and LCS clinical trials acknowledge that mortality from ASCVD events exceeds that of lung cancer.4,5 In an analysis of asymptomatic individuals from the Framingham Heart Offspring study who were eligible for LCS, the ASCVD event rate during a median (IQR) follow-up of 11.4 (9.7-12.0) years was 12.6%.6 However, despite the high rate of ASCVD events in this population, primary prevention strategies are consistently underused. In a study of 5495 individuals who underwent LCS with LDCT, only 40% of those eligible for statins had one prescribed, underscoring the missed opportunity for preventing ASCVD events during LCS.7 Yet the interactions for shared decision making and the availability of coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores from the LDCT provide an ideal window for intervening and preventing ASCVD events during LCS.

CAC is a hallmark of atherosclerotic plaque development and is proportional to plaque burden and ASCVD risk.8 Because of the relationship between CAC, subclinical atherosclerosis, and ASCVD risk, there is an opportunity to use CAC detected by LDCT to predict ASCVD risk and guide recommendations for statin treatment in individuals enrolled in LCS. Traditionally, CAC has been visualized by ECG-gated noncontrast CT scans with imaging protocols specifically designed to visualize the coronary arteries, minimize motion artifacts, and reduce signal noise. These scans are specifically done for primary prevention risk assessment and report an Agatston score, a summed measure based on calcified plaque area and maximal density.9 Results are reported as an overall CAC score and an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted percentile of CAC. Currently, a CAC score ≥ 100 or above the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race is considered abnormal.

High-quality evidence supports CAC scores as a strong predictor of ASCVD risk independent of age, sex, race, and other traditional risk factors.10-12 In asymptomatic individuals, a CAC score of 0 is a strong, negative risk factor associated with very low annualized mortality rates and cardiovascular (CV) events, so intermediate-risk individuals can be reclassified to a lower risk group avoiding or delaying statin therapy.13 As a result, current primary prevention guidelines allow for CAC scoring in asymptomatic, intermediate-risk adults where the clinical benefits of statin therapy are uncertain, knowing the CAC score will aid in the clinical decision to delay or initiate statin therapy.

Unlike traditional ECG-gated CAC scoring, LDCT imaging protocols are non–ECG-gated and performed at variable energy and slice thickness to optimize the detection of lung nodules. Early studies suggested that CAC detected by LDCT could be used in lieu of traditional CAC scoring to personalize risk.14,15 Recently, multiple studies have validated the accuracy and reproducibility of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC. In both the NELSON and the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) LCS trials, higher visual and quantitative measures of CAC were independently and incrementally associated with ASCVD risk.16,17 A subsequent review and meta-analysis of 6 LCS trials confirmed CAC detected by LDCT to be an independent predictor of ASCVD events regardless of the method used to measure CAC.18

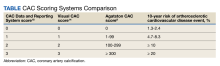

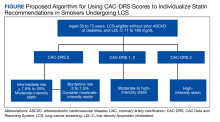

There is now consensus that either an Agatston score or a visual estimate of CAC be reported on all noncontrast, noncardiac chest CT scans irrespective of the indication or technique, including LDCT scans for LCS using a uniform reporting system known as the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS).19 The CAC-DRS simplifies reporting and adds modifiers indicating if the reported score is visual (V) or Agatston (A) and number of vessels involved. For example, CAC-DRS A0 or CAC-DRS V0 would indicate an Agatston score of 0 or a visual score of 0. CAC-DRS A1/N2 would indicate a total Agatston score of 1-99 in 2 coronary arteries. The currently agreed-on CAC-DRS risk groups are listed in the Table, along with their corresponding visual score or Agatston score and anticipated 10-year event rate, irrespective of other risk factors.20

As LCS efforts increase, primary care practitioners will receive LDCT reports that now incorporate an estimation of CAC (visual or quantitative). Thus, it will be increasingly important to know how to interpret and use these scores to guide clinical decisions regarding the initiation of statin therapy, referral for additional testing, and when to seek specialty cardiology care. For instance, does the absence of CAC (CAC = 0) on LDCT predict a low enough risk for statin therapy to be delayed or withdrawn? Does increasing CAC scores on follow-up LDCT in individuals on statin therapy represent treatment failure? When should CAC scores trigger additional testing, such as a stress test or referral to cardiology specialty care?

Primary Prevention in LCS

The initial approach to primary prevention in LCS is no different from that recommended by the 2018 multisociety guidelines on the management of blood cholesterol, the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline on primary prevention, or the 2022 USPTSF recommendations on statin use for primary prevention of CV disease in adults.21-23 For a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 190 mg/dL, high-intensity statin therapy is recommended without further risk stratification. Individuals with diabetes also are at higher-than-average risk, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended.

For individuals not in either group, a validated ASCVD risk assessment tool is recommended to estimate baseline risk. The most validated tool for estimating risk in the US population is the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) which provides an estimate of the 10-year risk for fatal and myocardial infarction and fatal and nonfatal stroke.24 The PCE risk calculator uses age, presence of diabetes, sex, smoking history, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and treatment for hypertension to place individuals into 1 of 4 risk groups: low (< 5%), borderline (5% to < 7.5%), intermediate (≥ 7.5% to < 20%), and high (≥ 20%). Clinicians should be aware that the PCE only considers current smoking history and not prior smoking history or cumulative pack-year history. This differs from eligibility for LCS where recent smoking plays a larger role. All these risk factors are important to consider when evaluating risk and discussing risk-reducing strategies like statin therapy.

The 2018 multisociety guidelines and the 2019 primary prevention guidelines set the threshold for considering initiation of statin therapy at intermediate risk ≥ 7.5%.21,22 The 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines set the threshold for considering statin therapy at an estimated 10-year event rate of 12%, whereas the 2022 UPSTF recommendations set the threshold at 10% with additional risk factors as the threshold for statin therapy.23,25 The reasons for these differences are beyond the scope of this review, but all these guidelines use the PCE to estimate baseline risk as the starting point for clinical decision making.

The PCE was originally derived and validated in population studies dating to the 1960s when the importance of diet, exercise, and smoking cessation in reducing ASCVD events was not well appreciated. The application of the PCE in more contemporary populations shows that it overestimates risk, especially in older individuals and women.26,27 Overestimation of risk has the potential to result in the initiation of statin therapy in individuals in whom the actual clinical benefit would otherwise be small.

To address this issue, current guidelines allow the use of CAC scoring to refine risk in individuals who are classified as intermediate risk and who otherwise desire to avoid lifelong statin therapy. Using current recommendations, we make suggestions on how to use CAC scores from LDCT to aid in clinical decision making for individuals in LCS (Figure).

No Coronary Artery Calcification

Between 25% and 30% of LDCT done for LCS will show no CAC.14,16 In general population studies, a CAC score of 0 is a strong negative predictor when there are no other risk factors.13,28 In contrast, the negative predictive ability of a CAC score of 0 in individuals with a smoking history who are eligible for LCS is unproven. In multivariate modeling, a CAC score of 0 did not reduce the significant hazard of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or smokers.29 In an analysis of 44,042 individuals without known heart disease referred for CAC scoring, the frequency of a CAC score of 0 was only modestly lower in smokers (38%) compared with nonsmokers (42%), yet the all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher.30 In addition, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) participants who were current smokers or eligible for LCS and had a CAC score of 0 had an observed 11-year ASCVD event rate of 13.4% and 20.8%, respectively, leading to the conclusion that a CAC score of 0 may not be predictive of minimal risk in smokers and those eligible for LCS.31 Additionally, in LCS-eligible individuals, the PCE underestimated event rates and incorporation of CAC scores did not significantly improve risk estimation. Finally, data from the NLST screening trial showed that the absence of CAC on LDCT was not associated with better survival or lower CV mortality compared with individuals with low CAC scores.32

The question of whether individuals undergoing LCS with LDCT who have no detectable CAC can avoid statin therapy is an unresolved issue; no contemporary studies have looked specifically at the relationship between estimated risk, a CAC score of 0, and ASCVD outcomes in individuals participating in LCS. For these reasons, we recommend moderate-intensity statin therapy when the estimated risk is intermediate because it is unclear that either an Agatston score of 0 reclassifies intermediate-risk LCS-eligible individuals to a lower risk group.

For the few borderline risk (estimated risk, 5% to < 7.5%) LCS-eligible individuals, a CAC score of 0 might confer low short-term risk but the long-term benefit of statin therapy on reducing subsequent risk, the presence of other risk factors, and the willingness to stop smoking should all be considered. For these individuals who elect to avoid statin therapy, annual re-estimation of risk at the time of repeat LDCT is recommended. In these circumstances, referral for traditional Agatston scoring is not likely to change decision making because the sensitivity of the 2 techniques is very similar.

Agatston Score of 1-99 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 1

In general population studies, these scores correspond to borderline risk and an estimated 10-year event rate of just under 7.5%.20 In both the NELSON and NLST LCS trials, even low amounts of CAC regardless of the scoring method were associated with higher observed ASCVD mortality when adjusted for other baseline risk factors.32 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with intermediate and borderline risk, a CAC score between 1 and 99 or a visual estimate of 1 indicates the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is reasonable.

Agatston Score of 100-299 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 2

Across all ages, races, and sexes, CAC scores between 100 to 299 are associated with an event rate of about 15% over 10 years.20 In the NELSON LCS trial, the adjusted hazard ratio for ASCVD events with a nontraditional Agatston score of 101 to 400 was 6.58.33 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with a CAC score of 100 to 299, regardless of the baseline risk estimate, the projected absolute event rate at 10 years would be about 20%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended to reduce the baseline LDL-C by 30% to 49%.

Agatston Score of > 300 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 3

Agatston CAC scores > 300 are consistent with a 10-year incidence of ASCVD events of > 15% regardless of age, sex, or race and ethnicity.20 In the Calcium Consortium, a CAC > 400 was correlated with an event rate of 13.6 events/1000 person-years.12 In a Walter Reed Military Medical Center study, a CAC score > 400 projected a cumulative incidence of ASCVD events of nearly 20% at 10 years.34 In smokers eligible for LCS, a CAC score > 300 projected a 10-year ASCVD event rate of 25%.29 In these patients, moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended, although high-intensity statin therapy can be considered if there are other risk factors.

Agatston Score ≥ 1000

The 2018 consensus statement on CAC reporting categorizes all CAC scores > 300 into a single risk group because the recommended treatment options do not differ.19 However, recent data suggest this might not be the case since individuals with very high CAC scores experience high rates of events that might justify more aggressive intervention. In an analysis of individuals who participated in the CAC Consortium with a CAC score ≥ 1000, the all-cause mortality rate was 18.8 per 1000 person-years with a CV mortality rate of 8 per 1000 person-years.35 Individuals with very high levels of CAC > 1000 also have a greater number of diseased coronary arteries, higher involvement of the left main coronary artery, and significantly higher event rates compared with those with a CAC of 400 to 999.36 In an analysis of individuals from the NLST trial, nontraditionally measured Agatston score > 1000 was associated with a hazard ratio for coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality of 3.66 in men and 5.81 in women.17 These observed and projected levels of risk are like that seen in secondary prevention trials, and some experts have recommended the use of high-intensity statin therapy to reduce LDL-C to < 70 mg/dL.37

Primary Prevention in Individuals aged 76 to 80 years

LCS can continue through age 80 years, while the PCE and primary prevention guidelines are truncated at age 75 years. Because age is a major contributor to risk, many of these individuals will already be in the intermediate- to high-risk group. However, the net clinical benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention in this age group is not well established, and the few primary prevention trials in this group have not demonstrated net clinical benefit.38 As a result, current guidelines do not provide specific treatment recommendations for individuals aged > 75 years but recognize the value of shared decision making considering associated comorbidities, age-related risks of statin therapy, and the desires of the individual to avoid ASCVD-related events even if the net clinical benefit is low.

Older individuals with elevated CAC scores should be informed about the risk of ASCVD events and the potential but unproven benefit of moderate-intensity statin therapy. Older individuals with a CAC score of 0 likely have low short-term risk of ASCVD events and withholding statin therapy is not unreasonable.

CAC Scores on Annual LDCT Scans

Because LCS requires annual LDCT scans, primary care practitioners and patients need to understand the significance of changing CAC scores over time. For individuals not on statin therapy, increasing calcification is a marker of progression of subclinical atherosclerosis. Patients undergoing LCS not on statin who have progressive increases in their CAC should consider initiating statin therapy. Individuals who opted not to initiate statin therapy who subsequently develop CAC should be re-engaged in a discussion about the significance of the finding and the clinically proven benefits of statin therapy in individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis. These considerations do not apply to individuals already on statin therapy. Statins convert lipid-rich plaques to lipid-depleted plaques, resulting in increasing calcification. As a result, CAC scores do not decrease and may increase with statin therapy.39 Individuals participating in annual LCS should be informed of this possibility. Also, in these individuals, referral to specialty care as a treatment failure is not supported by the literature.

Furthermore, serial CAC scoring to titrate the intensity of statin therapy is not currently recommended. The goal with moderate-intensity statin therapy is a 30% to 49% reduction from baseline LDL-C. If this milestone is not achieved, the statin dose can be escalated. For high-intensity statin therapy, the goal is a > 50% reduction. If this milestone is not achieved, then additional lipid-lowering agents, such as ezetimibe, can be added.

Further ASCVD Testing

LCS with LDCT is associated with improved health outcomes, and LDCT is the preferred imaging modality. The ability of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC is sufficient for clinical decision making. Therefore, obtaining a traditional CAC score increases radiation exposure without additional clinical benefits.

Furthermore, although referral for additional testing in those with nonzero CAC scores is common, current evidence does not support this practice in asymptomatic individuals. Indeed, the risks of LCS include overdiagnosis, excessive testing, and overtreatment secondary to the discovery of other findings, such as benign pulmonary nodules and CAC. With respect to CAD, randomized controlled trials do not support a strategy of coronary angiography and intervention in asymptomatic individuals, even with moderate-to-severe ischemia on functional testing.40 As a result, routine stress tests to diagnose CAD or to confirm the results of CAC scores in asymptomatic individuals are not recommended. The only potential exception would be in select cases where the CAC score is > 1000 and when calcium is predominately located in the left main coronary artery.

Conclusions

LCS provides smokers at risk for lung cancer with the best probability to survive that diagnosis, and coincidentally LCS may also provide the best opportunity to prevent ASCVD events and mortality. Before initiating LCS, clinicians should initiate a shared decision making conversation about the benefits and risks of LDCT scans. In addition to relevant education about smoking, during shared decision making, the initial ASCVD risk estimate should be done using the PCE and when appropriate the benefits of statin therapy discussed. Individuals also should be informed of the potential for identifying CAC and counseled on its significance and how it might influence the decision to recommend statin therapy.

In patients undergoing LCS with an estimated risk of ≥ 7.5% to < 20%, moderate-intensity statin therapy is indicated. In this setting, a CAC score > 0 indicates subclinical atherosclerosis and should be used to help direct patients toward initiating statin therapy. Unfortunately, in patients undergoing LCS a CAC score of 0 might not provide protection against ASCVD, and until there is more information to the contrary, these individuals should at least participate in shared decision making about the long-term benefits of statin therapy in reducing ASCVD risk. Because LDCT scanning is done annually, there are opportunities to review the importance of prevention and to adjust therapy as needed to achieve the greatest reduction in ASCVD. Reported elevated CAC scores on LDCT provide an opportunity to re-engage the patient in the discussion about the benefits of statin therapy if they are not already on a statin, or consideration for high-intensity statin if the CAC score is > 1000 or reduction in baseline LDL-C is < 30% on the current statin dose.

1. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, Oudkerk M. Lung-cancer screening and the NELSON Trial. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2165-2166. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004224

2. Aberle T, Adams DR, Berg AM, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):396-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

3. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;25(10):962-970. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1117

4. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341-350. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1211128

5. Khan SS, Ning H, Sinha A, et al. Cigarette smoking and competing risks for fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease subtypes across the life course. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(23):e021751. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.021751

6. Lu MT, Onuma OK, Massaro JM, et al. Lung cancer screening eligibility in the community: cardiovascular risk factors, coronary artery calcification, and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2016;134(12):897-899. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023957

7. Tailor TD, Chiles C, Yeboah J, et al. Cardiovascular risk in the lung cancer screening population: a multicenter study evaluating the association between coronary artery calcification and preventive statin prescription. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(9):1258-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.01.015

8. Mori H, Torii S, Kutyna M, et al. Coronary artery calcification and its progression: what does it really mean? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(1):127-142. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.012

10. Nasir K, Bittencourt MS, Blaha MJ, et al. Implications of coronary artery calcium testing among statin candidates according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol management guidelines: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(15): 1657-1668. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.066

11. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1336-1345. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072100

12. Grandhi GR, Mirbolouk M, Dardari ZA. Interplay of coronary artery calcium and risk factors for predicting CVD/CHD Mortality: the CAC Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(5):1175-1186. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.08.024

13. Blaha M, Budoff MJ, Shaw J. Absence of coronary artery calcification and all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(6):692-700. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.009

14. Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Farooqi A, et al. Frequency of coronary artery calcification on low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Clin Imaging. 2006;30(3):181-185. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2005.11.002

15. Shemesh J, Henschke C, Shaham D, et al. Ordinal scoring of coronary artery calcifications on low-dose CT scans of the chest is predictive of death from cardiovascular disease. Radiology. 2010;257:541-548. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100383

16. Jacobs PC, Gondrie MJ, van der Graaf Y, et al. Coronary artery calcium can predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events on low-dose CT screening for lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(3):505-511. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5577

17. Lessmann N, de Jong PA, Celeng C, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery and thoracic aorta calcification and their association with cardiovascular mortality in heavy smokers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9):1808-1817. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.10.026

18. Gendarme S, Goussault H, Assie JB, et al. Impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates of coronary artery calcifications detected during organized, low-dose, computed-tomography screening for lung cancer: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(7):1553. doi:10.3390/cancers13071553

19. Hecht HS, Blaha MJ, Kazerooni EA, et al. CAC-DRS: coronary artery calcium data and reporting system. An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018;12(3):185-191. doi:10.1016/j.jcct.2018.03.008

20. Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, et al. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(25):2401-2408. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy217

21. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1046-e1081. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000624

22. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

23. Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328(8):746-753. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.13044

24. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889-2934. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002

25. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline. Updated August 25, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/lipids

25. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline. Updated August 25, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/lipids

26. DeFilippis AP, Young, R, Carrubba CJ, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266-275. doi:10.7326/M14-1281

27. Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon, MD, et al. Accuracy of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk equation in a large contemporary, multiethnic population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(18):2118-2130. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.055

28. Sarwar A, Shaw LJ, Shapiro MD, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(6):675-688. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.031

29. McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Rivera JJ, et al. Mortality rates in smokers and nonsmokers in the presence or absence of coronary artery calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(10):1037-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.02.017

30. Leigh A, McEvoy JW, Garg P, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk stratification in smokers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(5):852-861. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.017

31. Garg PK, Jorgensen NW, McClelland RL, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to improve coronary heart disease risk assessment in lung cancer screening population: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomagr. 2018;12(6):439-400.

32. Chiles C, Duan F, Gladish GW, et al. Association of coronary artery calcification and mortality in the national lung screening trial: a comparison of three scoring methods. Radiology. 2015;276(1):82-90. doi:10.1148/radiol.15142062

33. Takx RA, Isgum I, Willemink MJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium in nongated CT to predict cardiovascular events in male lung cancer screening participants: results of the NELSON study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9(1):50-57. doi:10.1016/j.jcct.2014.11.006

34. Mitchell JD, Paisley R, Moon P, et al. Coronary artery calcium and long-term risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke: The Walter Reed Cohort Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(12):1799-1806. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.09.003

35. Peng AW, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, et al. Long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality in asymptomatic patients with CAC >/=1,000: results from the CAC Consortium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;13(1, pt 1):83-93. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.005

36. Peng AW, Dardari ZA. Blumenthal RS, et al. Very high coronary artery calcium (>/=1000) and association with cardiovascular disease events, non-cardiovascular disease outcomes, and mortality: results from MESA. Circulation. 2021;143(16):1571-1583. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050545

37. Orringer CE, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, et al. The National Lipid Association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction. J Clin Lipidol. 2021;15(1):33-60. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2020.12.005

38. Sheperd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. PROSPER study group. PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease. (PROSPER): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623-1630. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x

39. Puri R, Nicholls SJ, Shao M, et al. Impact of statins on serial coronary calcification during atheroma progression and regression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(13):1273-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.036

40. Maron D.J, Hochman J S, Reynolds HR, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1395-1407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1915922

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality, and cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor. Several randomized clinical trials have shown that lung cancer screening (LCS) with nonelectrocardiogram (ECG)-gated low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces both lung cancer and all-cause mortality.1,2 Hence, the US Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommends annual screening with LDCT in adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20-pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.3

Smoking is also an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), and LCS clinical trials acknowledge that mortality from ASCVD events exceeds that of lung cancer.4,5 In an analysis of asymptomatic individuals from the Framingham Heart Offspring study who were eligible for LCS, the ASCVD event rate during a median (IQR) follow-up of 11.4 (9.7-12.0) years was 12.6%.6 However, despite the high rate of ASCVD events in this population, primary prevention strategies are consistently underused. In a study of 5495 individuals who underwent LCS with LDCT, only 40% of those eligible for statins had one prescribed, underscoring the missed opportunity for preventing ASCVD events during LCS.7 Yet the interactions for shared decision making and the availability of coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores from the LDCT provide an ideal window for intervening and preventing ASCVD events during LCS.

CAC is a hallmark of atherosclerotic plaque development and is proportional to plaque burden and ASCVD risk.8 Because of the relationship between CAC, subclinical atherosclerosis, and ASCVD risk, there is an opportunity to use CAC detected by LDCT to predict ASCVD risk and guide recommendations for statin treatment in individuals enrolled in LCS. Traditionally, CAC has been visualized by ECG-gated noncontrast CT scans with imaging protocols specifically designed to visualize the coronary arteries, minimize motion artifacts, and reduce signal noise. These scans are specifically done for primary prevention risk assessment and report an Agatston score, a summed measure based on calcified plaque area and maximal density.9 Results are reported as an overall CAC score and an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted percentile of CAC. Currently, a CAC score ≥ 100 or above the 75th percentile for age, sex, and race is considered abnormal.

High-quality evidence supports CAC scores as a strong predictor of ASCVD risk independent of age, sex, race, and other traditional risk factors.10-12 In asymptomatic individuals, a CAC score of 0 is a strong, negative risk factor associated with very low annualized mortality rates and cardiovascular (CV) events, so intermediate-risk individuals can be reclassified to a lower risk group avoiding or delaying statin therapy.13 As a result, current primary prevention guidelines allow for CAC scoring in asymptomatic, intermediate-risk adults where the clinical benefits of statin therapy are uncertain, knowing the CAC score will aid in the clinical decision to delay or initiate statin therapy.

Unlike traditional ECG-gated CAC scoring, LDCT imaging protocols are non–ECG-gated and performed at variable energy and slice thickness to optimize the detection of lung nodules. Early studies suggested that CAC detected by LDCT could be used in lieu of traditional CAC scoring to personalize risk.14,15 Recently, multiple studies have validated the accuracy and reproducibility of LDCT to detect and quantify CAC. In both the NELSON and the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) LCS trials, higher visual and quantitative measures of CAC were independently and incrementally associated with ASCVD risk.16,17 A subsequent review and meta-analysis of 6 LCS trials confirmed CAC detected by LDCT to be an independent predictor of ASCVD events regardless of the method used to measure CAC.18

There is now consensus that either an Agatston score or a visual estimate of CAC be reported on all noncontrast, noncardiac chest CT scans irrespective of the indication or technique, including LDCT scans for LCS using a uniform reporting system known as the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS).19 The CAC-DRS simplifies reporting and adds modifiers indicating if the reported score is visual (V) or Agatston (A) and number of vessels involved. For example, CAC-DRS A0 or CAC-DRS V0 would indicate an Agatston score of 0 or a visual score of 0. CAC-DRS A1/N2 would indicate a total Agatston score of 1-99 in 2 coronary arteries. The currently agreed-on CAC-DRS risk groups are listed in the Table, along with their corresponding visual score or Agatston score and anticipated 10-year event rate, irrespective of other risk factors.20

As LCS efforts increase, primary care practitioners will receive LDCT reports that now incorporate an estimation of CAC (visual or quantitative). Thus, it will be increasingly important to know how to interpret and use these scores to guide clinical decisions regarding the initiation of statin therapy, referral for additional testing, and when to seek specialty cardiology care. For instance, does the absence of CAC (CAC = 0) on LDCT predict a low enough risk for statin therapy to be delayed or withdrawn? Does increasing CAC scores on follow-up LDCT in individuals on statin therapy represent treatment failure? When should CAC scores trigger additional testing, such as a stress test or referral to cardiology specialty care?

Primary Prevention in LCS

The initial approach to primary prevention in LCS is no different from that recommended by the 2018 multisociety guidelines on the management of blood cholesterol, the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline on primary prevention, or the 2022 USPTSF recommendations on statin use for primary prevention of CV disease in adults.21-23 For a baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥ 190 mg/dL, high-intensity statin therapy is recommended without further risk stratification. Individuals with diabetes also are at higher-than-average risk, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended.

For individuals not in either group, a validated ASCVD risk assessment tool is recommended to estimate baseline risk. The most validated tool for estimating risk in the US population is the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE) which provides an estimate of the 10-year risk for fatal and myocardial infarction and fatal and nonfatal stroke.24 The PCE risk calculator uses age, presence of diabetes, sex, smoking history, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and treatment for hypertension to place individuals into 1 of 4 risk groups: low (< 5%), borderline (5% to < 7.5%), intermediate (≥ 7.5% to < 20%), and high (≥ 20%). Clinicians should be aware that the PCE only considers current smoking history and not prior smoking history or cumulative pack-year history. This differs from eligibility for LCS where recent smoking plays a larger role. All these risk factors are important to consider when evaluating risk and discussing risk-reducing strategies like statin therapy.

The 2018 multisociety guidelines and the 2019 primary prevention guidelines set the threshold for considering initiation of statin therapy at intermediate risk ≥ 7.5%.21,22 The 2020 US Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines set the threshold for considering statin therapy at an estimated 10-year event rate of 12%, whereas the 2022 UPSTF recommendations set the threshold at 10% with additional risk factors as the threshold for statin therapy.23,25 The reasons for these differences are beyond the scope of this review, but all these guidelines use the PCE to estimate baseline risk as the starting point for clinical decision making.

The PCE was originally derived and validated in population studies dating to the 1960s when the importance of diet, exercise, and smoking cessation in reducing ASCVD events was not well appreciated. The application of the PCE in more contemporary populations shows that it overestimates risk, especially in older individuals and women.26,27 Overestimation of risk has the potential to result in the initiation of statin therapy in individuals in whom the actual clinical benefit would otherwise be small.

To address this issue, current guidelines allow the use of CAC scoring to refine risk in individuals who are classified as intermediate risk and who otherwise desire to avoid lifelong statin therapy. Using current recommendations, we make suggestions on how to use CAC scores from LDCT to aid in clinical decision making for individuals in LCS (Figure).

No Coronary Artery Calcification

Between 25% and 30% of LDCT done for LCS will show no CAC.14,16 In general population studies, a CAC score of 0 is a strong negative predictor when there are no other risk factors.13,28 In contrast, the negative predictive ability of a CAC score of 0 in individuals with a smoking history who are eligible for LCS is unproven. In multivariate modeling, a CAC score of 0 did not reduce the significant hazard of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or smokers.29 In an analysis of 44,042 individuals without known heart disease referred for CAC scoring, the frequency of a CAC score of 0 was only modestly lower in smokers (38%) compared with nonsmokers (42%), yet the all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher.30 In addition, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) participants who were current smokers or eligible for LCS and had a CAC score of 0 had an observed 11-year ASCVD event rate of 13.4% and 20.8%, respectively, leading to the conclusion that a CAC score of 0 may not be predictive of minimal risk in smokers and those eligible for LCS.31 Additionally, in LCS-eligible individuals, the PCE underestimated event rates and incorporation of CAC scores did not significantly improve risk estimation. Finally, data from the NLST screening trial showed that the absence of CAC on LDCT was not associated with better survival or lower CV mortality compared with individuals with low CAC scores.32

The question of whether individuals undergoing LCS with LDCT who have no detectable CAC can avoid statin therapy is an unresolved issue; no contemporary studies have looked specifically at the relationship between estimated risk, a CAC score of 0, and ASCVD outcomes in individuals participating in LCS. For these reasons, we recommend moderate-intensity statin therapy when the estimated risk is intermediate because it is unclear that either an Agatston score of 0 reclassifies intermediate-risk LCS-eligible individuals to a lower risk group.

For the few borderline risk (estimated risk, 5% to < 7.5%) LCS-eligible individuals, a CAC score of 0 might confer low short-term risk but the long-term benefit of statin therapy on reducing subsequent risk, the presence of other risk factors, and the willingness to stop smoking should all be considered. For these individuals who elect to avoid statin therapy, annual re-estimation of risk at the time of repeat LDCT is recommended. In these circumstances, referral for traditional Agatston scoring is not likely to change decision making because the sensitivity of the 2 techniques is very similar.

Agatston Score of 1-99 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 1

In general population studies, these scores correspond to borderline risk and an estimated 10-year event rate of just under 7.5%.20 In both the NELSON and NLST LCS trials, even low amounts of CAC regardless of the scoring method were associated with higher observed ASCVD mortality when adjusted for other baseline risk factors.32 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with intermediate and borderline risk, a CAC score between 1 and 99 or a visual estimate of 1 indicates the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis, and moderate-intensity statin therapy is reasonable.

Agatston Score of 100-299 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 2

Across all ages, races, and sexes, CAC scores between 100 to 299 are associated with an event rate of about 15% over 10 years.20 In the NELSON LCS trial, the adjusted hazard ratio for ASCVD events with a nontraditional Agatston score of 101 to 400 was 6.58.33 Thus, in patients undergoing LCS with a CAC score of 100 to 299, regardless of the baseline risk estimate, the projected absolute event rate at 10 years would be about 20%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended to reduce the baseline LDL-C by 30% to 49%.

Agatston Score of > 300 or CAC-DRS or Visual Score of 3

Agatston CAC scores > 300 are consistent with a 10-year incidence of ASCVD events of > 15% regardless of age, sex, or race and ethnicity.20 In the Calcium Consortium, a CAC > 400 was correlated with an event rate of 13.6 events/1000 person-years.12 In a Walter Reed Military Medical Center study, a CAC score > 400 projected a cumulative incidence of ASCVD events of nearly 20% at 10 years.34 In smokers eligible for LCS, a CAC score > 300 projected a 10-year ASCVD event rate of 25%.29 In these patients, moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended, although high-intensity statin therapy can be considered if there are other risk factors.

Agatston Score ≥ 1000

The 2018 consensus statement on CAC reporting categorizes all CAC scores > 300 into a single risk group because the recommended treatment options do not differ.19 However, recent data suggest this might not be the case since individuals with very high CAC scores experience high rates of events that might justify more aggressive intervention. In an analysis of individuals who participated in the CAC Consortium with a CAC score ≥ 1000, the all-cause mortality rate was 18.8 per 1000 person-years with a CV mortality rate of 8 per 1000 person-years.35 Individuals with very high levels of CAC > 1000 also have a greater number of diseased coronary arteries, higher involvement of the left main coronary artery, and significantly higher event rates compared with those with a CAC of 400 to 999.36 In an analysis of individuals from the NLST trial, nontraditionally measured Agatston score > 1000 was associated with a hazard ratio for coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality of 3.66 in men and 5.81 in women.17 These observed and projected levels of risk are like that seen in secondary prevention trials, and some experts have recommended the use of high-intensity statin therapy to reduce LDL-C to < 70 mg/dL.37

Primary Prevention in Individuals aged 76 to 80 years

LCS can continue through age 80 years, while the PCE and primary prevention guidelines are truncated at age 75 years. Because age is a major contributor to risk, many of these individuals will already be in the intermediate- to high-risk group. However, the net clinical benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention in this age group is not well established, and the few primary prevention trials in this group have not demonstrated net clinical benefit.38 As a result, current guidelines do not provide specific treatment recommendations for individuals aged > 75 years but recognize the value of shared decision making considering associated comorbidities, age-related risks of statin therapy, and the desires of the individual to avoid ASCVD-related events even if the net clinical benefit is low.

Older individuals with elevated CAC scores should be informed about the risk of ASCVD events and the potential but unproven benefit of moderate-intensity statin therapy. Older individuals with a CAC score of 0 likely have low short-term risk of ASCVD events and withholding statin therapy is not unreasonable.

CAC Scores on Annual LDCT Scans