User login

Pharmacogenomic Testing in Depression Treatment Decision Making: Clinical Pearls for Everyday Practice

CGRP-Targeted Therapies for Chronic Migraine Management

Migraine attacks are classified as chronic or episodic. Chronic migraines occur at least 15 days a month, and often prove functionally debilitating. In 2018, therapies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) were first introduced to help manage migraine attacks.

Dr Stephanie Nahas from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, discusses optimal approaches for incorporating these therapies, which include small molecule agents called gepants, and monoclonal antibodies. In both cases, these therapies prevent CGRP from binding to its receptor, which helps to reduce migraine symptomatology, both acutely and over time

According to Dr Nahas, the choice of therapy for an individual patient depends primarily on patient preferences. Most gepants are administered orally, and monoclonal antibodies are injected.

Dr Nahas recommends that these therapies should be considered when a previous treatment proves insufficient to reduce disease burden to the degree that allows improved functioning and quality of life for the patient.

--

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, Division of Headache Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University; Assistant Director, Headache Medicine Fellowship Program, Jefferson Headache Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Lundbeck; Pfizer; Theranica; Tonix (no relationships are active)

Migraine attacks are classified as chronic or episodic. Chronic migraines occur at least 15 days a month, and often prove functionally debilitating. In 2018, therapies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) were first introduced to help manage migraine attacks.

Dr Stephanie Nahas from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, discusses optimal approaches for incorporating these therapies, which include small molecule agents called gepants, and monoclonal antibodies. In both cases, these therapies prevent CGRP from binding to its receptor, which helps to reduce migraine symptomatology, both acutely and over time

According to Dr Nahas, the choice of therapy for an individual patient depends primarily on patient preferences. Most gepants are administered orally, and monoclonal antibodies are injected.

Dr Nahas recommends that these therapies should be considered when a previous treatment proves insufficient to reduce disease burden to the degree that allows improved functioning and quality of life for the patient.

--

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, Division of Headache Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University; Assistant Director, Headache Medicine Fellowship Program, Jefferson Headache Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Lundbeck; Pfizer; Theranica; Tonix (no relationships are active)

Migraine attacks are classified as chronic or episodic. Chronic migraines occur at least 15 days a month, and often prove functionally debilitating. In 2018, therapies that target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) were first introduced to help manage migraine attacks.

Dr Stephanie Nahas from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, discusses optimal approaches for incorporating these therapies, which include small molecule agents called gepants, and monoclonal antibodies. In both cases, these therapies prevent CGRP from binding to its receptor, which helps to reduce migraine symptomatology, both acutely and over time

According to Dr Nahas, the choice of therapy for an individual patient depends primarily on patient preferences. Most gepants are administered orally, and monoclonal antibodies are injected.

Dr Nahas recommends that these therapies should be considered when a previous treatment proves insufficient to reduce disease burden to the degree that allows improved functioning and quality of life for the patient.

--

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, Division of Headache Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University; Assistant Director, Headache Medicine Fellowship Program, Jefferson Headache Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Stephanie J. Nahas-Geiger, MD, MSEd, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Lundbeck; Pfizer; Theranica; Tonix (no relationships are active)

Optimal Preventive Therapy for Episodic Migraine

Episodic migraine occurs fewer than 15 days per month but can become chronic if poorly controlled. It is estimated that preventive therapy is indicated in over one third of patients with episodic migraine. Dr Barbara Nye from Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, discusses optimal approaches for managing episodic migraine. According to Dr Nye, several factors, including patient preference, clinical evidence, and insurance coverage, will help inform which treatments can be offered.

She mentions that currently approved treatments include nonspecific therapeutics such as antiseizure, antidepressant, and blood pressure medications. Newer therapies known as gepants and injectable monoclonal antibodies are also available to manage and prevent episodic migraine.

Dr Nye concludes that the appropriate therapeutic goal is a reduction in headache frequency, reduction in headache severity, and improved response to medications, as well as decreasing the level of disability that patients are experiencing.

--

Barbara L. Nye, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology, Wake Forest University; Director, Headache Fellowship, Department of Neurology, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Barbara L. Nye, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Episodic migraine occurs fewer than 15 days per month but can become chronic if poorly controlled. It is estimated that preventive therapy is indicated in over one third of patients with episodic migraine. Dr Barbara Nye from Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, discusses optimal approaches for managing episodic migraine. According to Dr Nye, several factors, including patient preference, clinical evidence, and insurance coverage, will help inform which treatments can be offered.

She mentions that currently approved treatments include nonspecific therapeutics such as antiseizure, antidepressant, and blood pressure medications. Newer therapies known as gepants and injectable monoclonal antibodies are also available to manage and prevent episodic migraine.

Dr Nye concludes that the appropriate therapeutic goal is a reduction in headache frequency, reduction in headache severity, and improved response to medications, as well as decreasing the level of disability that patients are experiencing.

--

Barbara L. Nye, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology, Wake Forest University; Director, Headache Fellowship, Department of Neurology, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Barbara L. Nye, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Episodic migraine occurs fewer than 15 days per month but can become chronic if poorly controlled. It is estimated that preventive therapy is indicated in over one third of patients with episodic migraine. Dr Barbara Nye from Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, discusses optimal approaches for managing episodic migraine. According to Dr Nye, several factors, including patient preference, clinical evidence, and insurance coverage, will help inform which treatments can be offered.

She mentions that currently approved treatments include nonspecific therapeutics such as antiseizure, antidepressant, and blood pressure medications. Newer therapies known as gepants and injectable monoclonal antibodies are also available to manage and prevent episodic migraine.

Dr Nye concludes that the appropriate therapeutic goal is a reduction in headache frequency, reduction in headache severity, and improved response to medications, as well as decreasing the level of disability that patients are experiencing.

--

Barbara L. Nye, MD, Associate Professor of Neurology, Wake Forest University; Director, Headache Fellowship, Department of Neurology, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Barbara L. Nye, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Acute Treatment of Migraine in Clinical Practice

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Acute Treatment of Migraine in Clinical Practice

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Migraine can be divided into two broad categories: episodic, in which attacks occur between two and four times a month; and chronic, in which individuals suffer from headaches for at least half the month and experience at least eight attacks.

Acute treatment is fundamental to reducing the immediate disability of migraine attack in both types, and several effective migraine-specific therapies have been approved.

Dr Jessica Ailani, director of the Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, discusses the benefits, potential side effects, and optimal use of migraine-specific therapies available for acute migraine, including how they can be used to build an effective treatment plan for an individual patient.

These include triptans (5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists), ergotamines (dihydroergotamine), neuromodulation devices, ditans (5-HT1F agonists), and gepants (CGRP antagonists).

--

Jessica Ailani, MD, Professor of Clinical Neurology, Director, Headache Center, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC

Jessica Ailani, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Aeon; electroCore; Dr. Reddy; Eli-Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline (2023); Lundbeck; Linpharma; Ipsen; Merz; Miravo; Pfizer; Neurolief; Gore; Satsuma; Scilex; Theranica; Tonix

Received research grant from: Parema; Ipsen; Lundbeck

Lichenoid Dermatosis on the Feet

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

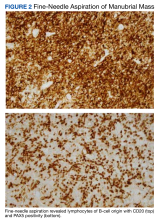

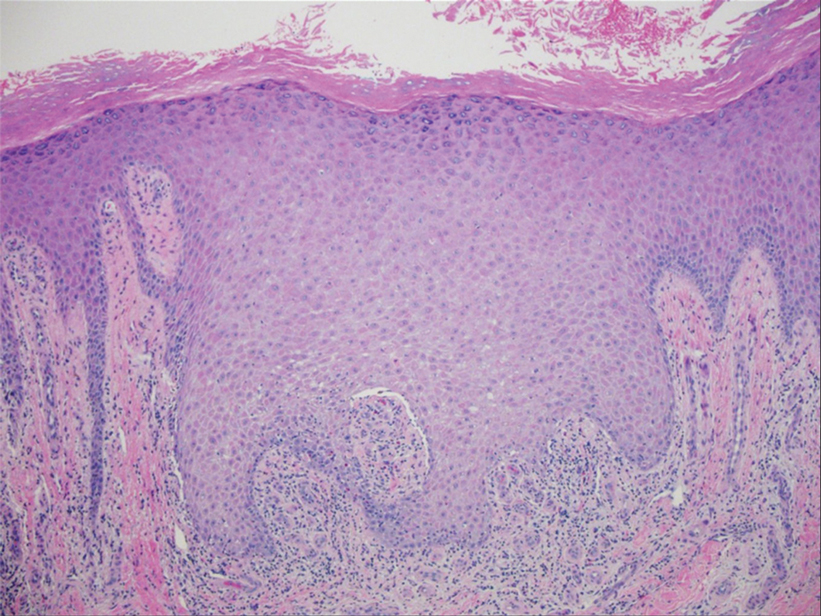

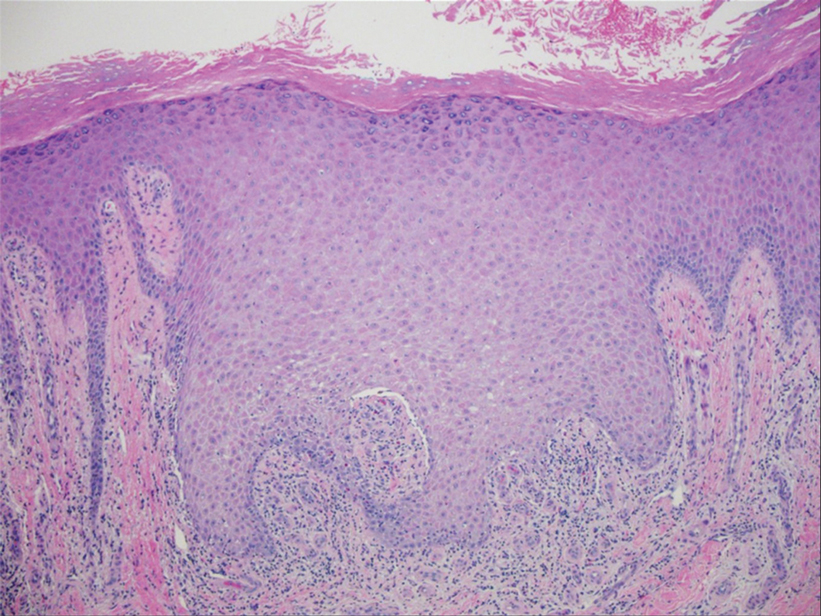

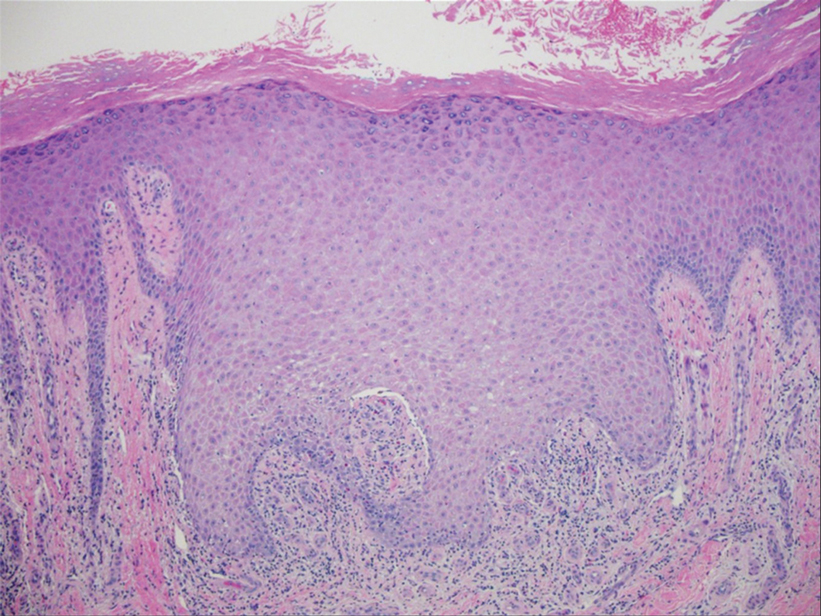

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lichen Planus

Two biopsies from the left lateral foot revealed hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, irregular acanthosis, and a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with a classic sawtooth pattern of the rete ridges (Figure 1). Based on the clinical findings and histopathology, the patient was diagnosed with hypertrophic lichen planus (LP) and was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05%, which resulted in progression of the symptoms. She experienced notable improvement 3 months after adding methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly (Figure 2).

Lichen planus is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition of the skin and mucous membranes that classically manifests as pruritic violaceous papules and plaques, which commonly are found on the wrists, lower back, and ankles.1 The most common variants of LP are hypertrophic, linear, mucosal, actinic, follicular, pigmented, annular, atrophic, and guttate.2 The clinical presentation and biopsy results in our patient were consistent with the hypertrophic variant of LP, which is a chronic condition that most often manifests on the lower legs, especially around the ankles, as hyperkeratotic papules, plaques, and nodules.2,3 The exact pathophysiology of hypertrophic LP is unknown, but there is evidence that the immune system plays a role in its development and that the Koebner phenomenon may contribute to its exacerbation.4 There is a well-known association between LP and hepatitis. Patients with chronic LP may develop squamous cell carcinoma.4 The variants of LP can overlap and do not exist independent of one another. Recognizing the overlap in these variants allows for earlier diagnosis and therapeutic intervention of the disease process to limit disease progression and patient clinic visits and to improve patient quality of life.

The differential diagnosis for hyperkeratotic plaques of the feet and ankles can be broad and may include keratosis lichenoides chronica, palmoplantar keratoderma, palmoplantar psoriasis, or lichen amyloidosis. These conditions are classified based on various criteria that include extent of disease manifestations, morphology of palmoplantar skin involvement, inheritance patterns, and molecular pathogenesis.5 Keratosis lichenoides chronica is a rare dermatosis that presents as a distinctive seborrheic dermatitis–like facial eruption. The facial eruption is accompanied by violaceous papular and nodular lesions that appear on the extremities and trunk, typically arranged in a linear or reticular pattern.6 Palmoplantar keratoderma represents a group of acquired and hereditary conditions that are characterized by excessive thickening of the palms and soles.5 Palmoplantar psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that affects the palms and soles and can manifest as hyperkeratosis, pustular, or mixed morphology.7 Lichen amyloidosis is a subtype of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis that manifests as multiple pruritic, firm, hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules on the shins that later coalesce in a rippled pattern.8,9

The first-line treatment for hypertrophic LP is topical corticosteroids. Alternative therapies include mycophenolate mofetil, acitretin, and intralesional corticosteroid injections.4 Treatment is similar for all of the LP variants.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Namazi MR, Bahmani M. Diagnosis: hypertrophic lichen planus. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:1-2. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2008.222

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:e3555. doi:10.7759 /cureus.3555

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2015.04.001

- Has C, Technau-Hafsi K. Palmoplantar keratodermas: clinical and genetic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:123-139; quiz 140. doi:10.1111/ddg.12930

- Konstantinov KN, Søndergaard J, Izuno G, et al. Keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(2 Pt 2):306-309. doi:10.1016 /s0190-9622(98)70570-5

- Miceli A, Schmieder GJ. Palmoplantar psoriasis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Tay CH, Dacosta JL. Lichen amyloidosis—clinical study of 40 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:129-136.

- Salim T, Shenoi SD, Balachandran C, et al. Lichen amyloidosis: a study of clinical, histopathologic and immunofluorescence findings in 30 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:166-169.

An 83-year-old woman presented for evaluation of hyperkeratotic plaques on the medial and lateral aspects of the left heel (top). Physical examination also revealed onychodystrophy of the toenails on the halluces (bottom). A crusted friable plaque on the lower lip and white plaques with peripheral reticulation and erosions on the buccal mucosa also were present. The patient had a history of nummular eczema, stasis dermatitis, and hand dermatitis. She denied a history of cold sores.

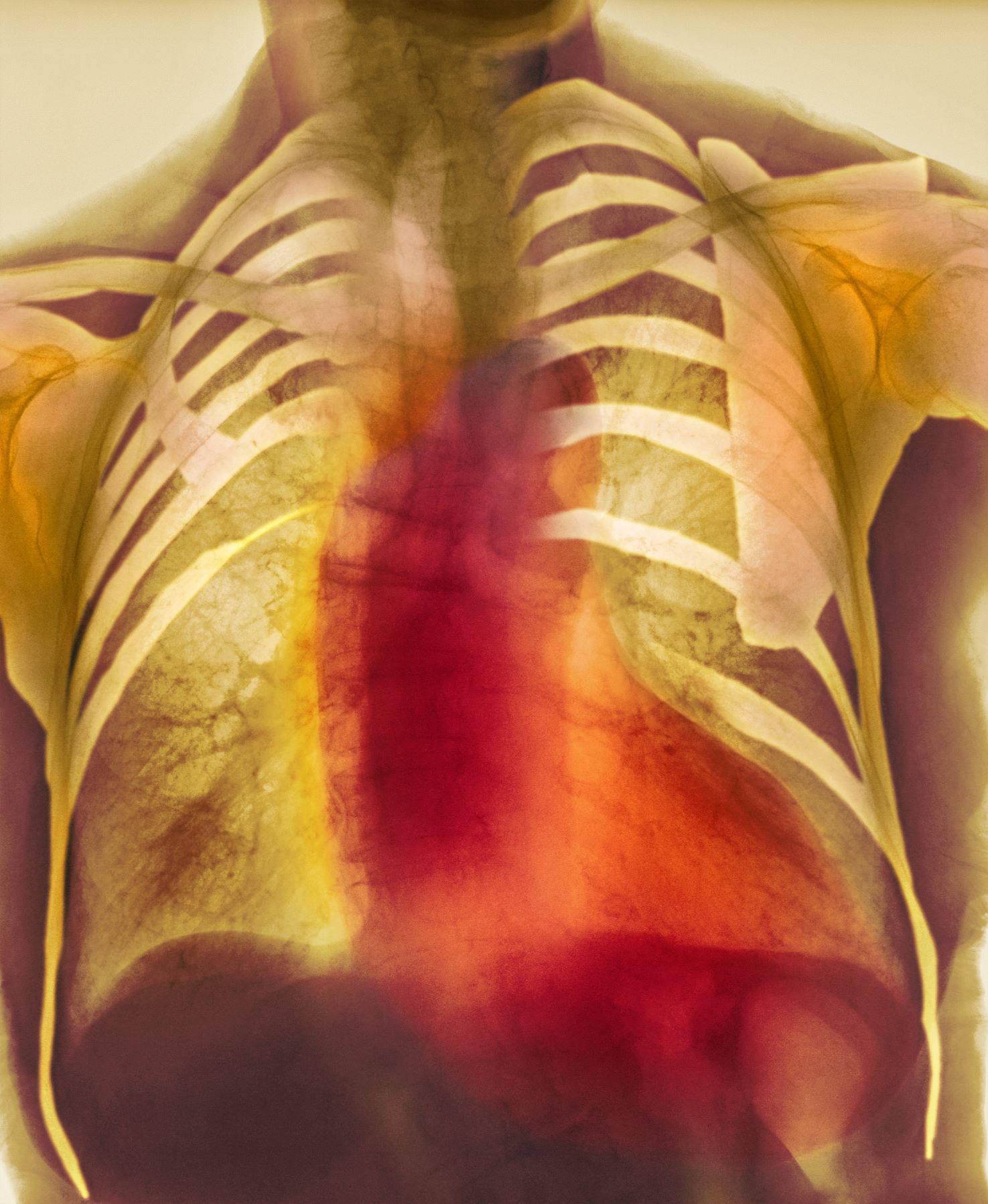

Dyspnea and mild edema

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old patient with obesity presents with dyspnea and mild edema. The patient is 5 ft 9 in, weighs 210 lb (BMI 31), and received an obesity diagnosis 1 year ago with a weight of 220 lb (BMI 32.5) but notes having lived with a BMI ≥ 30 for at least 5 years. Since being diagnosed with obesity, the patient has participated in regular counseling with a clinical nutrition specialist and exercise therapy, reports satisfaction with these, and is happy to have lost 10 lb. The patient presents today for follow-up physical exam and lab workup, with a complaint of increasing dyspnea that has limited participation in exercise therapy over the past 2 months.

On physical exam, the patient appears pale, with shortness of breath and mild edema in the ankles. The heart rhythm is fluttery and the heart rate is elevated at 90 beats/min. Blood pressure is 150/90 mm Hg. Lab results show A1c 6.6% and fasting glucose of 115 mg/dL. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is 101 mg/dL. Thyroid and hematologic findings are within normal parameters. The patient is sent for chest radiography, shown above (colorized).

Moral Injury in Health Care: A Unified Definition and its Relationship to Burnout

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

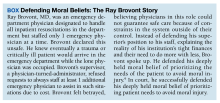

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

EBER-Negative, Double-Hit High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma Responding to Methotrexate Discontinuation