User login

Adjuvant Chemotherapy May be Omitted in Older Women Aged 80 Years or Older With HR+/HER2- BC

Key clinical point: Among patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC), adjuvant chemotherapy failed to improve survival outcomes in older women (age ≥ 80 years) but improved prognosis in women age 65-79 years.

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival (OS; P = .79) and cancer-specific survival (CSS; P = .091) outcomes in patients age 80 years and older. However, in patients age 65-79 years, adjuvant chemotherapy was effective in improving OS (P < .001) but not CSS (P = .092).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 45,762 women with HR+/HER2− BC, age 65-79 years (n = 38,128) or 80 years and older (n = 7634) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, of whom 20.7% and 3.8%, respectively, received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Project '100 Foreign Experts Plan of Hebei Province,' China. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Source: Ma X, Wu S, Zhang X, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival outcomes in older women with HR+/HER2- breast cancer: A propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study using the SEER database. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078782. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078782 Source

Key clinical point: Among patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC), adjuvant chemotherapy failed to improve survival outcomes in older women (age ≥ 80 years) but improved prognosis in women age 65-79 years.

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival (OS; P = .79) and cancer-specific survival (CSS; P = .091) outcomes in patients age 80 years and older. However, in patients age 65-79 years, adjuvant chemotherapy was effective in improving OS (P < .001) but not CSS (P = .092).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 45,762 women with HR+/HER2− BC, age 65-79 years (n = 38,128) or 80 years and older (n = 7634) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, of whom 20.7% and 3.8%, respectively, received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Project '100 Foreign Experts Plan of Hebei Province,' China. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Source: Ma X, Wu S, Zhang X, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival outcomes in older women with HR+/HER2- breast cancer: A propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study using the SEER database. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078782. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078782 Source

Key clinical point: Among patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) breast cancer (BC), adjuvant chemotherapy failed to improve survival outcomes in older women (age ≥ 80 years) but improved prognosis in women age 65-79 years.

Major finding: Adjuvant chemotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival (OS; P = .79) and cancer-specific survival (CSS; P = .091) outcomes in patients age 80 years and older. However, in patients age 65-79 years, adjuvant chemotherapy was effective in improving OS (P < .001) but not CSS (P = .092).

Study details: This retrospective cohort study included 45,762 women with HR+/HER2− BC, age 65-79 years (n = 38,128) or 80 years and older (n = 7634) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, of whom 20.7% and 3.8%, respectively, received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Project '100 Foreign Experts Plan of Hebei Province,' China. The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Source: Ma X, Wu S, Zhang X, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival outcomes in older women with HR+/HER2- breast cancer: A propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study using the SEER database. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078782. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078782 Source

Antibiotic Exposure During Immunotherapy Increases Disease Burden in HER2− Early BC

Key clinical point: Exposure to antibiotics during neoadjuvant pembrolizumab treatment was associated with a high residual cancer burden (RCB) in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), stage II or III breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: During pembrolizumab treatment, antibiotic use was significantly correlated with RCB index (RCB index-coefficient 0.86; P = .01) and was associated with a higher mean RCB index compared with no use of antibiotics (1.80 vs 1.08).

Study details: This secondary analysis of the phase 2 I-SPY2 trial included 66 patients with HER2− stage II or III BC treated with pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, of which 27% of patients concurrently used antibiotics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Amit A. Kulkarni declared receiving institutional research funding and serving on advisory boards for various sources. The other authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kulkarni AA, Jain A, Jewett PI, et al, and the ISPY2 Consortium. Association of antibiotic exposure with residual cancer burden in HER2-negative early stage breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024;10:24 (Mar 26). doi: 10.1038/s41523-024-00630-w Source

Key clinical point: Exposure to antibiotics during neoadjuvant pembrolizumab treatment was associated with a high residual cancer burden (RCB) in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), stage II or III breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: During pembrolizumab treatment, antibiotic use was significantly correlated with RCB index (RCB index-coefficient 0.86; P = .01) and was associated with a higher mean RCB index compared with no use of antibiotics (1.80 vs 1.08).

Study details: This secondary analysis of the phase 2 I-SPY2 trial included 66 patients with HER2− stage II or III BC treated with pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, of which 27% of patients concurrently used antibiotics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Amit A. Kulkarni declared receiving institutional research funding and serving on advisory boards for various sources. The other authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kulkarni AA, Jain A, Jewett PI, et al, and the ISPY2 Consortium. Association of antibiotic exposure with residual cancer burden in HER2-negative early stage breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024;10:24 (Mar 26). doi: 10.1038/s41523-024-00630-w Source

Key clinical point: Exposure to antibiotics during neoadjuvant pembrolizumab treatment was associated with a high residual cancer burden (RCB) in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−), stage II or III breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: During pembrolizumab treatment, antibiotic use was significantly correlated with RCB index (RCB index-coefficient 0.86; P = .01) and was associated with a higher mean RCB index compared with no use of antibiotics (1.80 vs 1.08).

Study details: This secondary analysis of the phase 2 I-SPY2 trial included 66 patients with HER2− stage II or III BC treated with pembrolizumab plus paclitaxel followed by doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, of which 27% of patients concurrently used antibiotics.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Amit A. Kulkarni declared receiving institutional research funding and serving on advisory boards for various sources. The other authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kulkarni AA, Jain A, Jewett PI, et al, and the ISPY2 Consortium. Association of antibiotic exposure with residual cancer burden in HER2-negative early stage breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2024;10:24 (Mar 26). doi: 10.1038/s41523-024-00630-w Source

Breast Cancer Radiation Therapy Raises Risk for Nonkeratinocyte Skin Cancer

Key clinical point: Patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) who underwent radiation therapy were at a significantly higher risk of developing nonkeratinocyte skin cancers, particularly melanoma and hemangiosarcoma.

Major finding: Compared with the general population, the risk for nonkeratinocyte skin cancer in the skin of the breast or trunk was 57% higher (standardized incidence ratio [SIR] 1.57; 95% CI 1.45-1.7) after BC treatment with radiation therapy, with a 1.37-fold higher risk for melanoma (SIR 1.37; 95% CI 1.25-1.49) and 27.11-fold higher risk for hemangiosarcoma (SIR 27.11; 95% CI 21.6-33.61).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 875,880 patients with newly diagnosed BC from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of which 50.3% of patients received radiation therapy.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding. Shawheen J. Rezaei declared being supported by Stanford University School of Medicine. Bernice Y. Kwong declared receiving personal fees from Novocure, Genentech, and Novartis. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Rezaei SJ, Eid E, Tang JY, et al. Incidence of nonkeratinocyte skin cancer after breast cancer radiation therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e241632 (Mar 8). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1632 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) who underwent radiation therapy were at a significantly higher risk of developing nonkeratinocyte skin cancers, particularly melanoma and hemangiosarcoma.

Major finding: Compared with the general population, the risk for nonkeratinocyte skin cancer in the skin of the breast or trunk was 57% higher (standardized incidence ratio [SIR] 1.57; 95% CI 1.45-1.7) after BC treatment with radiation therapy, with a 1.37-fold higher risk for melanoma (SIR 1.37; 95% CI 1.25-1.49) and 27.11-fold higher risk for hemangiosarcoma (SIR 27.11; 95% CI 21.6-33.61).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 875,880 patients with newly diagnosed BC from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of which 50.3% of patients received radiation therapy.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding. Shawheen J. Rezaei declared being supported by Stanford University School of Medicine. Bernice Y. Kwong declared receiving personal fees from Novocure, Genentech, and Novartis. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Rezaei SJ, Eid E, Tang JY, et al. Incidence of nonkeratinocyte skin cancer after breast cancer radiation therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e241632 (Mar 8). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1632 Source

Key clinical point: Patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) who underwent radiation therapy were at a significantly higher risk of developing nonkeratinocyte skin cancers, particularly melanoma and hemangiosarcoma.

Major finding: Compared with the general population, the risk for nonkeratinocyte skin cancer in the skin of the breast or trunk was 57% higher (standardized incidence ratio [SIR] 1.57; 95% CI 1.45-1.7) after BC treatment with radiation therapy, with a 1.37-fold higher risk for melanoma (SIR 1.37; 95% CI 1.25-1.49) and 27.11-fold higher risk for hemangiosarcoma (SIR 27.11; 95% CI 21.6-33.61).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 875,880 patients with newly diagnosed BC from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of which 50.3% of patients received radiation therapy.

Disclosures: This study did not declare any specific funding. Shawheen J. Rezaei declared being supported by Stanford University School of Medicine. Bernice Y. Kwong declared receiving personal fees from Novocure, Genentech, and Novartis. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Rezaei SJ, Eid E, Tang JY, et al. Incidence of nonkeratinocyte skin cancer after breast cancer radiation therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e241632 (Mar 8). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.1632 Source

MRI-Based Strategy Can Limit Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Duration in HR−/HER2+ BC

Key clinical point: MRI response can be used to identify patients with hormone receptor-negative (HR−), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer (BC) who may only require three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to achieve pathological complete response (pCR).

Major finding: After one to three cycles of chemotherapy, nearly one third of patients with HR−/HER2+ BC achieved radiological complete response (36%; 95% CI 30%-43%), of whom the majority of patients achieved pCR (88%; 95% CI 79%-94%). No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2 TRAIN-3 trial included 235 and 232 patients with stages II-III HR−/HER2+ and HR+/HER2+ BC, respectively, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy once every 3 weeks for up to nine cycles and whose response was monitored using breast MRI after every three cycles and lymph node biopsy.

Disclosures: This study received unrestricted financial support from Roche Netherlands. Two authors declared receiving institutional research funding from or having other ties with various sources, including Roche.

Source: van der Voort A, Louis FM, van Ramshorst MS, et al, on behalf of the Dutch Breast Cancer Research Group. MRI-guided optimisation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy duration in stage II–III HER2-positive breast cancer (TRAIN-3): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00104-9 Source

Key clinical point: MRI response can be used to identify patients with hormone receptor-negative (HR−), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer (BC) who may only require three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to achieve pathological complete response (pCR).

Major finding: After one to three cycles of chemotherapy, nearly one third of patients with HR−/HER2+ BC achieved radiological complete response (36%; 95% CI 30%-43%), of whom the majority of patients achieved pCR (88%; 95% CI 79%-94%). No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2 TRAIN-3 trial included 235 and 232 patients with stages II-III HR−/HER2+ and HR+/HER2+ BC, respectively, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy once every 3 weeks for up to nine cycles and whose response was monitored using breast MRI after every three cycles and lymph node biopsy.

Disclosures: This study received unrestricted financial support from Roche Netherlands. Two authors declared receiving institutional research funding from or having other ties with various sources, including Roche.

Source: van der Voort A, Louis FM, van Ramshorst MS, et al, on behalf of the Dutch Breast Cancer Research Group. MRI-guided optimisation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy duration in stage II–III HER2-positive breast cancer (TRAIN-3): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00104-9 Source

Key clinical point: MRI response can be used to identify patients with hormone receptor-negative (HR−), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer (BC) who may only require three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to achieve pathological complete response (pCR).

Major finding: After one to three cycles of chemotherapy, nearly one third of patients with HR−/HER2+ BC achieved radiological complete response (36%; 95% CI 30%-43%), of whom the majority of patients achieved pCR (88%; 95% CI 79%-94%). No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Study details: This phase 2 TRAIN-3 trial included 235 and 232 patients with stages II-III HR−/HER2+ and HR+/HER2+ BC, respectively, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy once every 3 weeks for up to nine cycles and whose response was monitored using breast MRI after every three cycles and lymph node biopsy.

Disclosures: This study received unrestricted financial support from Roche Netherlands. Two authors declared receiving institutional research funding from or having other ties with various sources, including Roche.

Source: van der Voort A, Louis FM, van Ramshorst MS, et al, on behalf of the Dutch Breast Cancer Research Group. MRI-guided optimisation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy duration in stage II–III HER2-positive breast cancer (TRAIN-3): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00104-9 Source

Novel Treatment Sequence Speeds Up Breast Reconstruction Procedures in Patients With Breast Cancer

Key clinical point: In patients with breast cancer (BC), premastectomy radiotherapy (PreMRT) followed by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction (IMBR) is feasible, safe, and shortens the time required for breast reconstruction.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 29.7 months, there were no complete flap losses, locoregional recurrences, distant metastases, or deaths in the 48 patients who completed mastectomy with IMBR. Patients could undergo mastectomy with IMBR as early as 3 weeks (median 23 days) after completing radiotherapy. No grade 3-4 radiotherapy-related toxic effect or discontinuation of radiotherapy was reported.

Study details: The study enrolled 49 patients with T0-T3, N0-N3b, M0 BC from the phase 2 SAPHIRE trial who received PreMRT and were randomly assigned to receive hypofractionated or conventionally fractionated regional nodal irradiation, followed by mastectomy and IMBR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health and others. Five authors declared receiving grants from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Schaverien MV, Singh P, Smith BD, et al. Premastectomy radiotherapy and immediate breast reconstruction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245217 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5217 Source

Key clinical point: In patients with breast cancer (BC), premastectomy radiotherapy (PreMRT) followed by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction (IMBR) is feasible, safe, and shortens the time required for breast reconstruction.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 29.7 months, there were no complete flap losses, locoregional recurrences, distant metastases, or deaths in the 48 patients who completed mastectomy with IMBR. Patients could undergo mastectomy with IMBR as early as 3 weeks (median 23 days) after completing radiotherapy. No grade 3-4 radiotherapy-related toxic effect or discontinuation of radiotherapy was reported.

Study details: The study enrolled 49 patients with T0-T3, N0-N3b, M0 BC from the phase 2 SAPHIRE trial who received PreMRT and were randomly assigned to receive hypofractionated or conventionally fractionated regional nodal irradiation, followed by mastectomy and IMBR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health and others. Five authors declared receiving grants from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Schaverien MV, Singh P, Smith BD, et al. Premastectomy radiotherapy and immediate breast reconstruction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245217 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5217 Source

Key clinical point: In patients with breast cancer (BC), premastectomy radiotherapy (PreMRT) followed by mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction (IMBR) is feasible, safe, and shortens the time required for breast reconstruction.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 29.7 months, there were no complete flap losses, locoregional recurrences, distant metastases, or deaths in the 48 patients who completed mastectomy with IMBR. Patients could undergo mastectomy with IMBR as early as 3 weeks (median 23 days) after completing radiotherapy. No grade 3-4 radiotherapy-related toxic effect or discontinuation of radiotherapy was reported.

Study details: The study enrolled 49 patients with T0-T3, N0-N3b, M0 BC from the phase 2 SAPHIRE trial who received PreMRT and were randomly assigned to receive hypofractionated or conventionally fractionated regional nodal irradiation, followed by mastectomy and IMBR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health and others. Five authors declared receiving grants from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Schaverien MV, Singh P, Smith BD, et al. Premastectomy radiotherapy and immediate breast reconstruction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e245217 (Apr 5). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5217 Source

High TIL Levels Linked to Improved Prognosis in Early TNBC Even in Absence of Chemotherapy

Key clinical point: Higher levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in breast cancer tissue was associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who received locoregional therapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 18 years, each 10% increase in TIL levels was associated with significantly improved invasive disease-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.92; 95% CI 0.89-0.94), overall survival (aHR 0.88; 95% CI 0.85-0.91), and recurrence-free survival outcomes (aHR 0.90; 95% CI 0.87-0.92).

Study details: This retrospective pooled analysis included 1966 patients with early-stage TNBC (stage I TNBC, 55%) who underwent surgery with or without radiotherapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and others. Several authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Leon-Ferre RA, Jonas SF, Salgado R, et al, for the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. JAMA. 2024;331:1135-1144 (Apr 2). doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.3056 Source

Key clinical point: Higher levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in breast cancer tissue was associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who received locoregional therapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 18 years, each 10% increase in TIL levels was associated with significantly improved invasive disease-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.92; 95% CI 0.89-0.94), overall survival (aHR 0.88; 95% CI 0.85-0.91), and recurrence-free survival outcomes (aHR 0.90; 95% CI 0.87-0.92).

Study details: This retrospective pooled analysis included 1966 patients with early-stage TNBC (stage I TNBC, 55%) who underwent surgery with or without radiotherapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and others. Several authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Leon-Ferre RA, Jonas SF, Salgado R, et al, for the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. JAMA. 2024;331:1135-1144 (Apr 2). doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.3056 Source

Key clinical point: Higher levels of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in breast cancer tissue was associated with improved survival outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who received locoregional therapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Major finding: At a median follow-up of 18 years, each 10% increase in TIL levels was associated with significantly improved invasive disease-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.92; 95% CI 0.89-0.94), overall survival (aHR 0.88; 95% CI 0.85-0.91), and recurrence-free survival outcomes (aHR 0.90; 95% CI 0.87-0.92).

Study details: This retrospective pooled analysis included 1966 patients with early-stage TNBC (stage I TNBC, 55%) who underwent surgery with or without radiotherapy but no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was partly supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and others. Several authors declared ties with various sources.

Source: Leon-Ferre RA, Jonas SF, Salgado R, et al, for the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. JAMA. 2024;331:1135-1144 (Apr 2). doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.3056 Source

Ribociclib + Nonsteroidal Aromatase Inhibitor Improves Prognosis in HR+/HER2− Early BC

Key clinical point: Ribociclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (NSAI) vs NSAI alone for 3 years significantly improved invasive disease-free survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At 3 years, ribociclib + NSAI vs NSAI alone led to a 25.2% lower risk for invasive disease, recurrence, or death (hazard ratio 0.75; two-sided P = .003), with an absolute invasive disease-free survival benefit of 3.3% (90.4% vs 87.1%). No new safety signals were reported.

Study details: This prespecified interim analysis of the phase 3 NATALEE trial included 5101 patients with HR+/HER2− stage II or III early BC who were randomly assigned to receive ribociclib (dosage 400 mg/day for 21 consecutive days followed by 7 days off; duration 36 months) in combination with an NSAI or NSAI alone.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by Novartis. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stocks in Novartis. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Novartis.

Source: Slamon D, Lipatov O, Nowecki Z, et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1080-1091 (Mar 20). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2305488 Source

Key clinical point: Ribociclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (NSAI) vs NSAI alone for 3 years significantly improved invasive disease-free survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At 3 years, ribociclib + NSAI vs NSAI alone led to a 25.2% lower risk for invasive disease, recurrence, or death (hazard ratio 0.75; two-sided P = .003), with an absolute invasive disease-free survival benefit of 3.3% (90.4% vs 87.1%). No new safety signals were reported.

Study details: This prespecified interim analysis of the phase 3 NATALEE trial included 5101 patients with HR+/HER2− stage II or III early BC who were randomly assigned to receive ribociclib (dosage 400 mg/day for 21 consecutive days followed by 7 days off; duration 36 months) in combination with an NSAI or NSAI alone.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by Novartis. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stocks in Novartis. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Novartis.

Source: Slamon D, Lipatov O, Nowecki Z, et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1080-1091 (Mar 20). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2305488 Source

Key clinical point: Ribociclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (NSAI) vs NSAI alone for 3 years significantly improved invasive disease-free survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) early breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: At 3 years, ribociclib + NSAI vs NSAI alone led to a 25.2% lower risk for invasive disease, recurrence, or death (hazard ratio 0.75; two-sided P = .003), with an absolute invasive disease-free survival benefit of 3.3% (90.4% vs 87.1%). No new safety signals were reported.

Study details: This prespecified interim analysis of the phase 3 NATALEE trial included 5101 patients with HR+/HER2− stage II or III early BC who were randomly assigned to receive ribociclib (dosage 400 mg/day for 21 consecutive days followed by 7 days off; duration 36 months) in combination with an NSAI or NSAI alone.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by Novartis. Six authors declared being employees of or holding stocks in Novartis. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Novartis.

Source: Slamon D, Lipatov O, Nowecki Z, et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1080-1091 (Mar 20). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2305488 Source

De-Escalating Axillary Surgery Feasible in Breast Cancer with Sentinel-Node Metastases

Key clinical point: Recurrence-free survival after sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) yielded noninferior outcomes compared to complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer (BC) and one or two sentinel-node macrometastases.

Major finding: The estimated 5-year recurrence-free survival was comparable in the SLNB alone vs completion ALND group (89.7% [95% CI 87.5%-91.9%] vs 88.7% [95% CI 86.3%-91.1%]), with the hazard ratio for recurrence or death being significantly below the noninferiority margin (0.89; P < .001 for non-inferiority).

Study details: Findings are from the noninferiority trial, SENOMAC, which included 2540 patients with clinically node-negative primary T1 to T3 BC with one or two sentinel lymph-node macrometastases who were randomly assigned to undergo SLNB alone (n = 1335) or completion ALND (n = 1205).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and others. Oreste D. Gentilini declared serving as a consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Boniface J, Tvedskov TF, Rydén L, et al, for the SENOMAC Trialists’ Group. Omitting axillary dissection in breast cancer with sentinel-node metastases. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1163-1175 (Apr 3). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2313487 Source

Key clinical point: Recurrence-free survival after sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) yielded noninferior outcomes compared to complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer (BC) and one or two sentinel-node macrometastases.

Major finding: The estimated 5-year recurrence-free survival was comparable in the SLNB alone vs completion ALND group (89.7% [95% CI 87.5%-91.9%] vs 88.7% [95% CI 86.3%-91.1%]), with the hazard ratio for recurrence or death being significantly below the noninferiority margin (0.89; P < .001 for non-inferiority).

Study details: Findings are from the noninferiority trial, SENOMAC, which included 2540 patients with clinically node-negative primary T1 to T3 BC with one or two sentinel lymph-node macrometastases who were randomly assigned to undergo SLNB alone (n = 1335) or completion ALND (n = 1205).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and others. Oreste D. Gentilini declared serving as a consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Boniface J, Tvedskov TF, Rydén L, et al, for the SENOMAC Trialists’ Group. Omitting axillary dissection in breast cancer with sentinel-node metastases. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1163-1175 (Apr 3). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2313487 Source

Key clinical point: Recurrence-free survival after sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) yielded noninferior outcomes compared to complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer (BC) and one or two sentinel-node macrometastases.

Major finding: The estimated 5-year recurrence-free survival was comparable in the SLNB alone vs completion ALND group (89.7% [95% CI 87.5%-91.9%] vs 88.7% [95% CI 86.3%-91.1%]), with the hazard ratio for recurrence or death being significantly below the noninferiority margin (0.89; P < .001 for non-inferiority).

Study details: Findings are from the noninferiority trial, SENOMAC, which included 2540 patients with clinically node-negative primary T1 to T3 BC with one or two sentinel lymph-node macrometastases who were randomly assigned to undergo SLNB alone (n = 1335) or completion ALND (n = 1205).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and others. Oreste D. Gentilini declared serving as a consultant for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: de Boniface J, Tvedskov TF, Rydén L, et al, for the SENOMAC Trialists’ Group. Omitting axillary dissection in breast cancer with sentinel-node metastases. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1163-1175 (Apr 3). doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2313487 Source

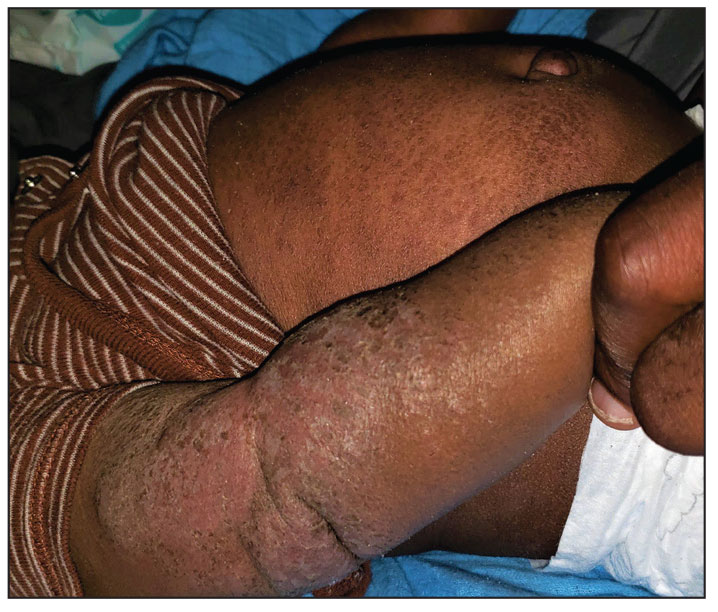

Progressively Worsening Scaly Patches and Plaques in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

A 5-month-old male with moderately brown skin that rarely burns and tans profusely presented to the emergency department with a worsening red rash of more than 4 months’ duration. The patient had diffuse erythroderma and eczematous patches and plaques covering 95% of the total body surface area, including lichenified plaques on the arms and elbows, with no signs of infection. He initially presented for his 1-month appointment at the pediatric clinic with scaly patches and plaques on the face and trunk as well as diffuse xerosis. He was prescribed daily oatmeal baths and topical Minerin (Major Pharmaceuticals)—containing water, petrolatum, mineral oil, mineral wax, lanolin alcohol, methylchloroisothiazolinone, and methylisothiazolinone—to be applied to the whole body twice daily. At the patient’s 2-month well visit, symptoms persisted. The patient’s pediatrician increased application of Minerin to 2 to 3 times daily, and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% application 2 to 3 times daily was added.