User login

Four-week, 8-week CAB/RPV injections safe, effective in women

according to results from the ATLAS-2M study, presented at the HIV Glasgow 2020 Virtual Conference, held October 5-8. The women also reported high satisfaction with the regimen, compared with daily oral antiretroviral therapy.

Previously reported results had shown that the two-drug combination administered every 8 weeks (600 mg cabotegravir and 900 mg rilpivirine) was noninferior to injections every 4 weeks (400 mg cabotegravir and 600 mg rilpivirine) in adults with HIV during the open-label phase 3b ATLAS-2M trial. Further, the ATLAS and FLAIR phase 3 trials had shown the 4-week administration of the therapy to be noninferior to a daily oral three-drug antiretroviral therapy.

Paul Benn, MBBS, of ViiV Healthcare (which is seeking regulatory approval for CAB/RPV treatment), and his colleagues completed a planned subgroup analysis of women in the ATLAS-2M trial. The primary endpoint was the proportion of intention-to-treat participants with plasma HIV-1 RNA of at least 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 4% at 48 weeks. The secondary endpoint was the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 10%.

Among the 280 women enrolled, 137 were randomly assigned to receive injections every 8 weeks, and 143 to receive injections every 4 weeks. A majority of the women (56%) were White, the median age was 44 years, and just over half (53%) were treatment naive with cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

At 48 weeks, 3.6% of women in the 8-week group and 0% of women in the 4-week group had at least 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA. In both arms, 91% of participants had HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL. Plasma concentrations of cabotegravir and rilpivirine were similar between the women and the overall study population.

Confirmed virologic failure occurred in five women, all before week 24. Three of the women were subtype A/A1, and four of them had archived nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance–associated mutations.

There were no significant differences in the safety profile between the groups; 99% of injection site reactions that occurred were mild to moderate and lasted a median 3-4 days. Fewer than 4% of participants discontinued because of adverse events – five women in the 8-week group and five women in the 4-week group. Four women cited injection site reactions as the reason for discontinuation.

Women not previously treated with CAB/RPV reported increased treatment satisfaction on the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, a score of 5.4 in the 8-week group and 3.9 in the 4-week group. Among those with prior CAB/RPV treatment, 88% preferred the 8-weekly injections, 8% preferred the 4-weekly injections, and 2% preferred oral dosing.

Long-acting CAB/RPV is an investigational formulation. In December 2019, the Food and Drug Administration denied approval to the formulation on the basis of manufacturing and chemistry concerns, according to a company press release.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results from the ATLAS-2M study, presented at the HIV Glasgow 2020 Virtual Conference, held October 5-8. The women also reported high satisfaction with the regimen, compared with daily oral antiretroviral therapy.

Previously reported results had shown that the two-drug combination administered every 8 weeks (600 mg cabotegravir and 900 mg rilpivirine) was noninferior to injections every 4 weeks (400 mg cabotegravir and 600 mg rilpivirine) in adults with HIV during the open-label phase 3b ATLAS-2M trial. Further, the ATLAS and FLAIR phase 3 trials had shown the 4-week administration of the therapy to be noninferior to a daily oral three-drug antiretroviral therapy.

Paul Benn, MBBS, of ViiV Healthcare (which is seeking regulatory approval for CAB/RPV treatment), and his colleagues completed a planned subgroup analysis of women in the ATLAS-2M trial. The primary endpoint was the proportion of intention-to-treat participants with plasma HIV-1 RNA of at least 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 4% at 48 weeks. The secondary endpoint was the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 10%.

Among the 280 women enrolled, 137 were randomly assigned to receive injections every 8 weeks, and 143 to receive injections every 4 weeks. A majority of the women (56%) were White, the median age was 44 years, and just over half (53%) were treatment naive with cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

At 48 weeks, 3.6% of women in the 8-week group and 0% of women in the 4-week group had at least 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA. In both arms, 91% of participants had HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL. Plasma concentrations of cabotegravir and rilpivirine were similar between the women and the overall study population.

Confirmed virologic failure occurred in five women, all before week 24. Three of the women were subtype A/A1, and four of them had archived nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance–associated mutations.

There were no significant differences in the safety profile between the groups; 99% of injection site reactions that occurred were mild to moderate and lasted a median 3-4 days. Fewer than 4% of participants discontinued because of adverse events – five women in the 8-week group and five women in the 4-week group. Four women cited injection site reactions as the reason for discontinuation.

Women not previously treated with CAB/RPV reported increased treatment satisfaction on the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, a score of 5.4 in the 8-week group and 3.9 in the 4-week group. Among those with prior CAB/RPV treatment, 88% preferred the 8-weekly injections, 8% preferred the 4-weekly injections, and 2% preferred oral dosing.

Long-acting CAB/RPV is an investigational formulation. In December 2019, the Food and Drug Administration denied approval to the formulation on the basis of manufacturing and chemistry concerns, according to a company press release.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results from the ATLAS-2M study, presented at the HIV Glasgow 2020 Virtual Conference, held October 5-8. The women also reported high satisfaction with the regimen, compared with daily oral antiretroviral therapy.

Previously reported results had shown that the two-drug combination administered every 8 weeks (600 mg cabotegravir and 900 mg rilpivirine) was noninferior to injections every 4 weeks (400 mg cabotegravir and 600 mg rilpivirine) in adults with HIV during the open-label phase 3b ATLAS-2M trial. Further, the ATLAS and FLAIR phase 3 trials had shown the 4-week administration of the therapy to be noninferior to a daily oral three-drug antiretroviral therapy.

Paul Benn, MBBS, of ViiV Healthcare (which is seeking regulatory approval for CAB/RPV treatment), and his colleagues completed a planned subgroup analysis of women in the ATLAS-2M trial. The primary endpoint was the proportion of intention-to-treat participants with plasma HIV-1 RNA of at least 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 4% at 48 weeks. The secondary endpoint was the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL with a noninferiority margin of 10%.

Among the 280 women enrolled, 137 were randomly assigned to receive injections every 8 weeks, and 143 to receive injections every 4 weeks. A majority of the women (56%) were White, the median age was 44 years, and just over half (53%) were treatment naive with cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

At 48 weeks, 3.6% of women in the 8-week group and 0% of women in the 4-week group had at least 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA. In both arms, 91% of participants had HIV-1 RNA under 50 copies/mL. Plasma concentrations of cabotegravir and rilpivirine were similar between the women and the overall study population.

Confirmed virologic failure occurred in five women, all before week 24. Three of the women were subtype A/A1, and four of them had archived nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) resistance–associated mutations.

There were no significant differences in the safety profile between the groups; 99% of injection site reactions that occurred were mild to moderate and lasted a median 3-4 days. Fewer than 4% of participants discontinued because of adverse events – five women in the 8-week group and five women in the 4-week group. Four women cited injection site reactions as the reason for discontinuation.

Women not previously treated with CAB/RPV reported increased treatment satisfaction on the HIV Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, a score of 5.4 in the 8-week group and 3.9 in the 4-week group. Among those with prior CAB/RPV treatment, 88% preferred the 8-weekly injections, 8% preferred the 4-weekly injections, and 2% preferred oral dosing.

Long-acting CAB/RPV is an investigational formulation. In December 2019, the Food and Drug Administration denied approval to the formulation on the basis of manufacturing and chemistry concerns, according to a company press release.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Social factors predicted peripartum depressive symptoms in Black women with HIV

Women with high-risk pregnancies because of chronic conditions are at increased risk for developing postpartum depression, and HIV may be one such risk. However, risk factors for women living with HIV, particularly Black women, have not been well studied, wrote Emmanuela Nneamaka Ojukwu of the University of Miami School of Nursing, and colleagues.

Data suggest that as many as half of cases of postpartum depression (PPD) begin before delivery, the researchers noted. “Therefore, for this study, the symptoms of both PND (prenatal depression) and PPD have been classified in what we have termed peripartum depressive symptoms (PDS),” and defined as depressive symptoms during pregnancy and within 1 year postpartum, they said.

In a study published in the Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of 143 Black women living with HIV seen at specialty prenatal and women’s health clinics in Miami.

Overall, 81 women (57%) reported either perinatal or postpartum depressive symptoms, or both. “Some of the symptoms prevalent among women in our study included restlessness, depressed mood, apathy, guilt, hopelessness, and social isolation,” the researchers said.

Social factors show significant impact

In a multivariate analysis, low income, intimate partner violence, and childcare burden were significant predictors of PDS (P less than .05). Women who reported intimate partner violence or abuse were 6.5 times more likely to experience PDS than were women who did not report abuse, and women with a childcare burden involving two children were 4.6 times more likely to experience PDS than were women with no childcare burden or only one child needing child care.

The average age of the women studied was 29 years, and 59% were above the federal poverty level. Nearly two-thirds (62%) were Black and 38% were Haitian; 63% were unemployed, 62% had a high school diploma or less, and 59% received care through Medicaid.

The researchers assessed four categories of health: HIV-related, gynecologic, obstetric, and psychosocial. The average viral load among the patients was 22,359 copies/mL at baseline, and they averaged 2.5 medical comorbidities. The most common comorbid conditions were other sexually transmitted infections and blood disorders, followed by cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

Quantitative studies needed

Larger quantitative studies of Black pregnant women living with HIV are needed to analyze social factors at multiple levels, the researchers said. “To address depression among Black women living with HIV, local and federal governments should enact measures that increase the family income and diminish the prevalence of [intimate partner violence] among these women,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including retrospective design and use of self-reports, as well as the small sample size and lack of generalizability to women living with HIV of other races or from other regions, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the value of early screening and referral to improve well being for Black women living with HIV, as well as the importance of comprehensive medical care, they said.

“Women should be counseled that postpartum physical and psychological changes (and the stresses and demands of caring for a new baby) may make [antiretroviral] adherence more difficult and that additional support may be needed during this period,” the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ojukwu EN et al. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020 May 22. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.05.004.

Women with high-risk pregnancies because of chronic conditions are at increased risk for developing postpartum depression, and HIV may be one such risk. However, risk factors for women living with HIV, particularly Black women, have not been well studied, wrote Emmanuela Nneamaka Ojukwu of the University of Miami School of Nursing, and colleagues.

Data suggest that as many as half of cases of postpartum depression (PPD) begin before delivery, the researchers noted. “Therefore, for this study, the symptoms of both PND (prenatal depression) and PPD have been classified in what we have termed peripartum depressive symptoms (PDS),” and defined as depressive symptoms during pregnancy and within 1 year postpartum, they said.

In a study published in the Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of 143 Black women living with HIV seen at specialty prenatal and women’s health clinics in Miami.

Overall, 81 women (57%) reported either perinatal or postpartum depressive symptoms, or both. “Some of the symptoms prevalent among women in our study included restlessness, depressed mood, apathy, guilt, hopelessness, and social isolation,” the researchers said.

Social factors show significant impact

In a multivariate analysis, low income, intimate partner violence, and childcare burden were significant predictors of PDS (P less than .05). Women who reported intimate partner violence or abuse were 6.5 times more likely to experience PDS than were women who did not report abuse, and women with a childcare burden involving two children were 4.6 times more likely to experience PDS than were women with no childcare burden or only one child needing child care.

The average age of the women studied was 29 years, and 59% were above the federal poverty level. Nearly two-thirds (62%) were Black and 38% were Haitian; 63% were unemployed, 62% had a high school diploma or less, and 59% received care through Medicaid.

The researchers assessed four categories of health: HIV-related, gynecologic, obstetric, and psychosocial. The average viral load among the patients was 22,359 copies/mL at baseline, and they averaged 2.5 medical comorbidities. The most common comorbid conditions were other sexually transmitted infections and blood disorders, followed by cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

Quantitative studies needed

Larger quantitative studies of Black pregnant women living with HIV are needed to analyze social factors at multiple levels, the researchers said. “To address depression among Black women living with HIV, local and federal governments should enact measures that increase the family income and diminish the prevalence of [intimate partner violence] among these women,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including retrospective design and use of self-reports, as well as the small sample size and lack of generalizability to women living with HIV of other races or from other regions, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the value of early screening and referral to improve well being for Black women living with HIV, as well as the importance of comprehensive medical care, they said.

“Women should be counseled that postpartum physical and psychological changes (and the stresses and demands of caring for a new baby) may make [antiretroviral] adherence more difficult and that additional support may be needed during this period,” the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ojukwu EN et al. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020 May 22. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.05.004.

Women with high-risk pregnancies because of chronic conditions are at increased risk for developing postpartum depression, and HIV may be one such risk. However, risk factors for women living with HIV, particularly Black women, have not been well studied, wrote Emmanuela Nneamaka Ojukwu of the University of Miami School of Nursing, and colleagues.

Data suggest that as many as half of cases of postpartum depression (PPD) begin before delivery, the researchers noted. “Therefore, for this study, the symptoms of both PND (prenatal depression) and PPD have been classified in what we have termed peripartum depressive symptoms (PDS),” and defined as depressive symptoms during pregnancy and within 1 year postpartum, they said.

In a study published in the Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of 143 Black women living with HIV seen at specialty prenatal and women’s health clinics in Miami.

Overall, 81 women (57%) reported either perinatal or postpartum depressive symptoms, or both. “Some of the symptoms prevalent among women in our study included restlessness, depressed mood, apathy, guilt, hopelessness, and social isolation,” the researchers said.

Social factors show significant impact

In a multivariate analysis, low income, intimate partner violence, and childcare burden were significant predictors of PDS (P less than .05). Women who reported intimate partner violence or abuse were 6.5 times more likely to experience PDS than were women who did not report abuse, and women with a childcare burden involving two children were 4.6 times more likely to experience PDS than were women with no childcare burden or only one child needing child care.

The average age of the women studied was 29 years, and 59% were above the federal poverty level. Nearly two-thirds (62%) were Black and 38% were Haitian; 63% were unemployed, 62% had a high school diploma or less, and 59% received care through Medicaid.

The researchers assessed four categories of health: HIV-related, gynecologic, obstetric, and psychosocial. The average viral load among the patients was 22,359 copies/mL at baseline, and they averaged 2.5 medical comorbidities. The most common comorbid conditions were other sexually transmitted infections and blood disorders, followed by cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

Quantitative studies needed

Larger quantitative studies of Black pregnant women living with HIV are needed to analyze social factors at multiple levels, the researchers said. “To address depression among Black women living with HIV, local and federal governments should enact measures that increase the family income and diminish the prevalence of [intimate partner violence] among these women,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including retrospective design and use of self-reports, as well as the small sample size and lack of generalizability to women living with HIV of other races or from other regions, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the value of early screening and referral to improve well being for Black women living with HIV, as well as the importance of comprehensive medical care, they said.

“Women should be counseled that postpartum physical and psychological changes (and the stresses and demands of caring for a new baby) may make [antiretroviral] adherence more difficult and that additional support may be needed during this period,” the researchers wrote.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Ojukwu EN et al. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020 May 22. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.05.004.

FROM ARCHIVES OF PSYCHIATRIC NURSING

Choose wisely

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

Four years ago, just prior to the 2016 presidential election, I mentioned the Choosing Wisely campaign in my JFP editorial.1 I said that family physicians should do their part in controlling health care costs by carefully selecting tests and treatments that are known to be effective and avoiding those that are not. This remains as true now as it was then.

The Choosing Wisely campaign was sparked by a family physician, Dr. Howard Brody, in the context of national health care reform. In a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine editorial, he challenged physicians to do their part in controlling health care costs by not ordering tests and treatments that have no value for patients.2 At that time, it was estimated that a third of tests and treatments ordered by US physicians were of marginal or no value.3

Dr. Brody’s editorial caught the attention of the National Physicians Alliance and eventually many other physician organizations. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation launched the Choosing Wisely initiative; today, the campaign Web site, choosingwisely.org, has a wealth of information and practice recommendations from 78 medical specialty organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

In this month’s issue of JFP, Dr. Kate Rowland has summarized 10 of the most important Choosing Wisely recommendations that apply to family physicians and other primary care clinicians. Here are 5 more recommendations from the Choosing Wisely list of tests and treatments to avoid ordering for your patients:

- Don’t perform pelvic exams on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer.

- Don’t routinely screen for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or digital rectal exam. For men who want PSA screening, it should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making.

- Don’t order annual electrocardiograms or any other cardiac screening for low-risk patients without symptoms.

- Don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics for otitis media in children ages 2 to 12 years with nonsevere symptoms when observation is reasonable.

- Don’t use dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 or men younger than 70 with no risk factors.

In total, AAFP lists 18 recommendations (2 additional recommendations have been withdrawn, based on updated evidence) on the Choosing Wisely Web site. I encourage you to review them to see if you should change any of your current patient recommendations.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

1. Hickner J. Count on this no matter who wins the election. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:664.

2. Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the Top Five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:283-285.

3. Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs—lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849-852.

Ruling out PE in pregnancy

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old G2P1001 at 28 weeks’ gestation presents to your clinic with 1 day of dyspnea and palpitations. Her pregnancy has been otherwise uncomplicated. She reports worsening dyspnea with mild exertion but denies other symptoms, including leg swelling.

The current incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnant women is estimated to be a relatively low 5 to 12 events per 10,000 pregnancies, yet the condition is the leading cause of maternal mortality in developed countries.2,3,4 Currently, there are conflicting recommendations among relevant organization guidelines regarding the use of D-dimer testing to aid in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) during pregnancy. Both the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend using D-dimer testing to rule out PE in pregnant women (ESC Class IIa, level of evidence B based on small studies, retrospective studies, and observational studies; GTH provides no grade).5,6

Conversely, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), and the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Society of Thoracic Radiology recommend against the use of D-dimer testing in pregnant women because pregnant women were excluded from D-dimer validation studies (RCOG and SOGC Grade D; ATS weak recommendation).4,7,8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not have specific recommendations regarding the use of D-dimer testing during pregnancy, but has endorsed the ATS guidelines.4,9 In addition, SOGC recommends against the use of clinical prediction scores (Grade D), and RCOG states that there is no evidence to support their use (Grade C).7,8 The remaining societies do not make a recommendation for or against the use of clinical prediction scores because of the absence of high-quality evidence regarding their use in the pregnant patient population.4,5,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Prospective validation of a strategy to diagnose PE in pregnant women

This multicenter, multinational, prospective diagnostic study involving 395 pregnant women evaluated the accuracy of PE diagnosis across 11 centers in France and Switzerland from August 2008 through July 2016.1 Patients with clinically suspected PE were evaluated in emergency departments. Patients were tested according to a diagnostic algorithm that included pretest clinical probability using the revised Geneva Score for Pulmonary Embolism (www.mdcalc.com/geneva-score-revised-pulmonary-embolism), a clinical prediction tool that uses patient history, presenting symptoms, and clinical signs to classify patients as being at low (0-3/25), intermediate (4-10/25), or high (≥ 11/25) risk;10 high-sensitivity D-dimer testing; bilateral lower limb compression ultrasonography (CUS); computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan.

PE was excluded in patients who had a low or intermediate pretest clinical probability score and a negative D-dimer test result (< 500 mcg/L). Patients with a high pretest probability score or positive D-dimer test result underwent CUS, and, if negative, subsequent CTPA. A V/Q scan was performed if the CTPA was inconclusive. If the work-up was negative, PE was excluded.

Untreated pregnant women had clinical follow-up at 3 months. Any cases of suspected VTE were evaluated by a 3-member independent adjudication committee blinded to the initial diagnostic work-up. The primary outcome was the rate of adjudicated VTE events during the 3-month follow-up period. PE was diagnosed in 28 patients (7.1%) and excluded in 367 (clinical probability score and negative D-dimer test result [n = 46], negative CTPA result [n = 290], normal or low-probability V/Q scan [n = 17], and other reason [n = 14]). Twenty-two women received anticoagulation during the follow-up period for other reasons (mainly history of previous VTE disease). No symptomatic VTE events occurred in any of the women after the diagnostic work-up was negative, including among those patients who were ruled out with only the clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result (rate 0.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0%-1%).

WHAT’S NEW

Clinical probability and D-dimer rule out PE in pregnant women

This study ruled out PE in patients with low/intermediate risk as determined by the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer test, enabling patients to avoid further diagnostic testing. This low-cost strategy can be applied easily to the pregnant population.

CAVEATS

Additional research is still needed

From the results of this study, 11.6% of patients (n = 46) had a PE ruled out utilizing the revised Geneva score in conjunction with a D-dimer test result, with avoidance of chest imaging. However, this study was powered for the entire treatment algorithm and was not specifically powered for patients with low- or intermediate-risk pretest probability scores. Since this is the first published prospective diagnostic study of VTE in pregnancy, further research is needed to confirm the findings that a clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result can safely rule out PE in pregnant women.

In addition, further research is needed to determine pregnancy-adapted D-dimer cut-off values, as the researchers of this study noted that < 500 mcg/L was useful in the first and second trimester, but that levels increased as gestational age increased.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

Implementing a diagnostic algorithm that incorporates sequential assessment of pretest clinical probability based on the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer measurement should be relatively easy to implement, as both methods are readily available and relatively inexpensive.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H, Elias A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. A multicenter prospective management outcome study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:766-773.

2. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2009-2012. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2014.

3. Bourjeily G, Paidas M, Khalil H, et al. Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375:500-512.

4. Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1200-1208.

5. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603.

6. Linnemann B, Bauersachs R, Rott H, et al. Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Diagnosis of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism-position paper of the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH). Vasa. 2016;45:87-101.

7. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the puerperium: acute management. Green‐top Guideline No. 37b. April 2015.

8. Chan WS, Rey E, Kent NE, et al. Venous thromboembolism and antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:527-553.

9. James A, Birsner M, Kaimal A, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins‐Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e1-e17.

10. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old G2P1001 at 28 weeks’ gestation presents to your clinic with 1 day of dyspnea and palpitations. Her pregnancy has been otherwise uncomplicated. She reports worsening dyspnea with mild exertion but denies other symptoms, including leg swelling.

The current incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnant women is estimated to be a relatively low 5 to 12 events per 10,000 pregnancies, yet the condition is the leading cause of maternal mortality in developed countries.2,3,4 Currently, there are conflicting recommendations among relevant organization guidelines regarding the use of D-dimer testing to aid in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) during pregnancy. Both the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend using D-dimer testing to rule out PE in pregnant women (ESC Class IIa, level of evidence B based on small studies, retrospective studies, and observational studies; GTH provides no grade).5,6

Conversely, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), and the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Society of Thoracic Radiology recommend against the use of D-dimer testing in pregnant women because pregnant women were excluded from D-dimer validation studies (RCOG and SOGC Grade D; ATS weak recommendation).4,7,8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not have specific recommendations regarding the use of D-dimer testing during pregnancy, but has endorsed the ATS guidelines.4,9 In addition, SOGC recommends against the use of clinical prediction scores (Grade D), and RCOG states that there is no evidence to support their use (Grade C).7,8 The remaining societies do not make a recommendation for or against the use of clinical prediction scores because of the absence of high-quality evidence regarding their use in the pregnant patient population.4,5,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Prospective validation of a strategy to diagnose PE in pregnant women

This multicenter, multinational, prospective diagnostic study involving 395 pregnant women evaluated the accuracy of PE diagnosis across 11 centers in France and Switzerland from August 2008 through July 2016.1 Patients with clinically suspected PE were evaluated in emergency departments. Patients were tested according to a diagnostic algorithm that included pretest clinical probability using the revised Geneva Score for Pulmonary Embolism (www.mdcalc.com/geneva-score-revised-pulmonary-embolism), a clinical prediction tool that uses patient history, presenting symptoms, and clinical signs to classify patients as being at low (0-3/25), intermediate (4-10/25), or high (≥ 11/25) risk;10 high-sensitivity D-dimer testing; bilateral lower limb compression ultrasonography (CUS); computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan.

PE was excluded in patients who had a low or intermediate pretest clinical probability score and a negative D-dimer test result (< 500 mcg/L). Patients with a high pretest probability score or positive D-dimer test result underwent CUS, and, if negative, subsequent CTPA. A V/Q scan was performed if the CTPA was inconclusive. If the work-up was negative, PE was excluded.

Untreated pregnant women had clinical follow-up at 3 months. Any cases of suspected VTE were evaluated by a 3-member independent adjudication committee blinded to the initial diagnostic work-up. The primary outcome was the rate of adjudicated VTE events during the 3-month follow-up period. PE was diagnosed in 28 patients (7.1%) and excluded in 367 (clinical probability score and negative D-dimer test result [n = 46], negative CTPA result [n = 290], normal or low-probability V/Q scan [n = 17], and other reason [n = 14]). Twenty-two women received anticoagulation during the follow-up period for other reasons (mainly history of previous VTE disease). No symptomatic VTE events occurred in any of the women after the diagnostic work-up was negative, including among those patients who were ruled out with only the clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result (rate 0.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0%-1%).

WHAT’S NEW

Clinical probability and D-dimer rule out PE in pregnant women

This study ruled out PE in patients with low/intermediate risk as determined by the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer test, enabling patients to avoid further diagnostic testing. This low-cost strategy can be applied easily to the pregnant population.

CAVEATS

Additional research is still needed

From the results of this study, 11.6% of patients (n = 46) had a PE ruled out utilizing the revised Geneva score in conjunction with a D-dimer test result, with avoidance of chest imaging. However, this study was powered for the entire treatment algorithm and was not specifically powered for patients with low- or intermediate-risk pretest probability scores. Since this is the first published prospective diagnostic study of VTE in pregnancy, further research is needed to confirm the findings that a clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result can safely rule out PE in pregnant women.

In addition, further research is needed to determine pregnancy-adapted D-dimer cut-off values, as the researchers of this study noted that < 500 mcg/L was useful in the first and second trimester, but that levels increased as gestational age increased.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

Implementing a diagnostic algorithm that incorporates sequential assessment of pretest clinical probability based on the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer measurement should be relatively easy to implement, as both methods are readily available and relatively inexpensive.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 28-year-old G2P1001 at 28 weeks’ gestation presents to your clinic with 1 day of dyspnea and palpitations. Her pregnancy has been otherwise uncomplicated. She reports worsening dyspnea with mild exertion but denies other symptoms, including leg swelling.

The current incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnant women is estimated to be a relatively low 5 to 12 events per 10,000 pregnancies, yet the condition is the leading cause of maternal mortality in developed countries.2,3,4 Currently, there are conflicting recommendations among relevant organization guidelines regarding the use of D-dimer testing to aid in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) during pregnancy. Both the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend using D-dimer testing to rule out PE in pregnant women (ESC Class IIa, level of evidence B based on small studies, retrospective studies, and observational studies; GTH provides no grade).5,6

Conversely, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC), and the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Society of Thoracic Radiology recommend against the use of D-dimer testing in pregnant women because pregnant women were excluded from D-dimer validation studies (RCOG and SOGC Grade D; ATS weak recommendation).4,7,8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not have specific recommendations regarding the use of D-dimer testing during pregnancy, but has endorsed the ATS guidelines.4,9 In addition, SOGC recommends against the use of clinical prediction scores (Grade D), and RCOG states that there is no evidence to support their use (Grade C).7,8 The remaining societies do not make a recommendation for or against the use of clinical prediction scores because of the absence of high-quality evidence regarding their use in the pregnant patient population.4,5,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Prospective validation of a strategy to diagnose PE in pregnant women

This multicenter, multinational, prospective diagnostic study involving 395 pregnant women evaluated the accuracy of PE diagnosis across 11 centers in France and Switzerland from August 2008 through July 2016.1 Patients with clinically suspected PE were evaluated in emergency departments. Patients were tested according to a diagnostic algorithm that included pretest clinical probability using the revised Geneva Score for Pulmonary Embolism (www.mdcalc.com/geneva-score-revised-pulmonary-embolism), a clinical prediction tool that uses patient history, presenting symptoms, and clinical signs to classify patients as being at low (0-3/25), intermediate (4-10/25), or high (≥ 11/25) risk;10 high-sensitivity D-dimer testing; bilateral lower limb compression ultrasonography (CUS); computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan.

PE was excluded in patients who had a low or intermediate pretest clinical probability score and a negative D-dimer test result (< 500 mcg/L). Patients with a high pretest probability score or positive D-dimer test result underwent CUS, and, if negative, subsequent CTPA. A V/Q scan was performed if the CTPA was inconclusive. If the work-up was negative, PE was excluded.

Untreated pregnant women had clinical follow-up at 3 months. Any cases of suspected VTE were evaluated by a 3-member independent adjudication committee blinded to the initial diagnostic work-up. The primary outcome was the rate of adjudicated VTE events during the 3-month follow-up period. PE was diagnosed in 28 patients (7.1%) and excluded in 367 (clinical probability score and negative D-dimer test result [n = 46], negative CTPA result [n = 290], normal or low-probability V/Q scan [n = 17], and other reason [n = 14]). Twenty-two women received anticoagulation during the follow-up period for other reasons (mainly history of previous VTE disease). No symptomatic VTE events occurred in any of the women after the diagnostic work-up was negative, including among those patients who were ruled out with only the clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result (rate 0.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0%-1%).

WHAT’S NEW

Clinical probability and D-dimer rule out PE in pregnant women

This study ruled out PE in patients with low/intermediate risk as determined by the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer test, enabling patients to avoid further diagnostic testing. This low-cost strategy can be applied easily to the pregnant population.

CAVEATS

Additional research is still needed

From the results of this study, 11.6% of patients (n = 46) had a PE ruled out utilizing the revised Geneva score in conjunction with a D-dimer test result, with avoidance of chest imaging. However, this study was powered for the entire treatment algorithm and was not specifically powered for patients with low- or intermediate-risk pretest probability scores. Since this is the first published prospective diagnostic study of VTE in pregnancy, further research is needed to confirm the findings that a clinical prediction tool and a negative D-dimer test result can safely rule out PE in pregnant women.

In addition, further research is needed to determine pregnancy-adapted D-dimer cut-off values, as the researchers of this study noted that < 500 mcg/L was useful in the first and second trimester, but that levels increased as gestational age increased.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

Implementing a diagnostic algorithm that incorporates sequential assessment of pretest clinical probability based on the revised Geneva score and a D-dimer measurement should be relatively easy to implement, as both methods are readily available and relatively inexpensive.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H, Elias A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. A multicenter prospective management outcome study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:766-773.

2. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2009-2012. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2014.

3. Bourjeily G, Paidas M, Khalil H, et al. Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375:500-512.

4. Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1200-1208.

5. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603.

6. Linnemann B, Bauersachs R, Rott H, et al. Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Diagnosis of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism-position paper of the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH). Vasa. 2016;45:87-101.

7. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the puerperium: acute management. Green‐top Guideline No. 37b. April 2015.

8. Chan WS, Rey E, Kent NE, et al. Venous thromboembolism and antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:527-553.

9. James A, Birsner M, Kaimal A, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins‐Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e1-e17.

10. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

1. Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H, Elias A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. A multicenter prospective management outcome study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:766-773.

2. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2009-2012. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2014.

3. Bourjeily G, Paidas M, Khalil H, et al. Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375:500-512.

4. Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1200-1208.

5. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:543-603.

6. Linnemann B, Bauersachs R, Rott H, et al. Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Diagnosis of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism-position paper of the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH). Vasa. 2016;45:87-101.

7. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the puerperium: acute management. Green‐top Guideline No. 37b. April 2015.

8. Chan WS, Rey E, Kent NE, et al. Venous thromboembolism and antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:527-553.

9. James A, Birsner M, Kaimal A, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins‐Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e1-e17.

10. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use a clinical probability score to identify patients at low or intermediate risk for pulmonary embolism (PE) and combine that with a high-sensitivity D-dimer test to rule out PE in pregnant women.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Prospective diagnostic management outcome study.1

Righini M, Robert-Ebadi H, Elias A, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism during pregnancy: a multicenter prospective management outcome study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:766-773.1

Female cardiac advantage essentially lost after MI

Women are known to lag 5-10 years behind men in experiencing coronary heart disease (CHD), but new research suggests the gap narrows substantially following a myocardial infarction.

“Women lose a considerable portion, but not all, of their coronary and survival advantage – i.e., the lower event rates – after suffering a MI,” study author Sanne Peters, PhD, George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, said in an interview.

Previous studies of sex differences in event rates after a coronary event have produced mixed results and were primarily focused on mortality following MI. Importantly, the studies also lacked a control group without a history of CHD and, thus, were unable to provide a reference point for the disparity in event rates, she explained.

Using the MarketScan and Medicare databases, however, Dr. Peters and colleagues matched 339,890 U.S. adults hospitalized for an MI between January 2015 and December 2016 with 1,359,560 U.S. adults without a history of CHD.

Over a median 1.3 years follow-up, there were 12,518 MIs in the non-CHD group and 27,115 recurrent MIs in the MI group.

The age-standardized rate of MI per 1,000 person-years was 4.0 in women and 6.1 in men without a history of CHD, compared with 57.6 in women and 62.7 in men with a prior MI.

After multivariate adjustment, the women-to-men hazard ratio for MI was 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.67) in the non-CHD group and 0.94 (95% CI, 0.92-0.96) in the prior MI group, the authors reported Oct. 5 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Additional results show the multivariate adjusted women-to-men hazard ratios for three other cardiovascular outcomes follow a similar pattern in the non-CHD and prior MI groups:

- CHD events: 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.54) and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.85-0.89).

- Heart failure hospitalization: 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-0.96) and 1.02 (95% CI, 1.00-1.04).

- All-cause mortality: 0.72 (95% CI, 0.71-0.73) and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.89-0.92).

“By including a control group of individuals without CHD, we demonstrated that the magnitude of the sex difference in cardiac event rates and survival is considerably smaller among those with prior MI than among those without a history of CHD,” Dr. Peters said.

Of note, the sex differences were consistent across age and race/ethnicity groups for all events, except for heart failure hospitalizations, where the adjusted hazard ratio for women vs. men age 80 years or older was 0.95 for those without a history of CHD (95% CI, 0.91-0.98) and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.96-1.02) for participants with a previous MI.

Dr. Peters said it’s not clear why the female advantage is attenuated post-MI but that one explanation is that women are less likely than men to receive guideline-recommended treatments and dosages or to adhere to prescribed therapies after MI hospitalization, which could put them at a higher risk of subsequent events and worse outcomes than men.

“Sex differences in pathophysiology of CHD and its complications may also explain, to some extent, why the rates of recurrent events are considerably more similar between the sexes than incident event rates,” she said. Compared with men, women have a higher incidence of MI with nonobstructive coronary artery disease and of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and evidence-based treatment options are more limited for both conditions.

“After people read this, I think the important thing to recognize is we need to push– as much as we can, with what meds we have, and what data we have – secondary prevention in these women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, director of preventive cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University, Columbus, said in an interview.

The lack of a female advantage post-MI should also elicit a “really meaningful conversation with our patients on shared decision-making of why they need to be on medications, remembering on our part to prescribe the medications, remembering to prescribe cardiac rehab, and also reminding our community we do need more data and need to investigate this further,” she said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nanette Wenger, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also points out that nonobstructive coronary disease is more common in women and, “yet, guideline-based therapies are those validated for obstructive coronary disease in a predominantly male population but, nonetheless, are applied for nonobstructive coronary disease.”

She advocates for aggressive evaluation and treatment for women with chest pain symptoms as well as early identification of women at risk for CHD, specifically those with metabolic syndrome, preeclampsia, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic inflammatory conditions, and high-risk race/ethnicity.

“Next, when coronary angiography is undertaken, particularly in younger women, an assiduous search for spontaneous coronary artery dissection and its appropriate management, as well as prompt and evidence-based interventions and medical therapies for an acute coronary event [are indicated],” Dr. Wenger wrote. “However, basic to improving outcomes for women is the elucidation of the optimal noninvasive techniques to identify microvascular disease, which could then enable delineation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic approaches.”

Dr. Peters is supported by a U.K. Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship. Dr. Mehta and Dr. Wenger disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Women are known to lag 5-10 years behind men in experiencing coronary heart disease (CHD), but new research suggests the gap narrows substantially following a myocardial infarction.

“Women lose a considerable portion, but not all, of their coronary and survival advantage – i.e., the lower event rates – after suffering a MI,” study author Sanne Peters, PhD, George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, said in an interview.

Previous studies of sex differences in event rates after a coronary event have produced mixed results and were primarily focused on mortality following MI. Importantly, the studies also lacked a control group without a history of CHD and, thus, were unable to provide a reference point for the disparity in event rates, she explained.

Using the MarketScan and Medicare databases, however, Dr. Peters and colleagues matched 339,890 U.S. adults hospitalized for an MI between January 2015 and December 2016 with 1,359,560 U.S. adults without a history of CHD.

Over a median 1.3 years follow-up, there were 12,518 MIs in the non-CHD group and 27,115 recurrent MIs in the MI group.

The age-standardized rate of MI per 1,000 person-years was 4.0 in women and 6.1 in men without a history of CHD, compared with 57.6 in women and 62.7 in men with a prior MI.

After multivariate adjustment, the women-to-men hazard ratio for MI was 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.67) in the non-CHD group and 0.94 (95% CI, 0.92-0.96) in the prior MI group, the authors reported Oct. 5 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Additional results show the multivariate adjusted women-to-men hazard ratios for three other cardiovascular outcomes follow a similar pattern in the non-CHD and prior MI groups:

- CHD events: 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.54) and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.85-0.89).

- Heart failure hospitalization: 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-0.96) and 1.02 (95% CI, 1.00-1.04).

- All-cause mortality: 0.72 (95% CI, 0.71-0.73) and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.89-0.92).

“By including a control group of individuals without CHD, we demonstrated that the magnitude of the sex difference in cardiac event rates and survival is considerably smaller among those with prior MI than among those without a history of CHD,” Dr. Peters said.

Of note, the sex differences were consistent across age and race/ethnicity groups for all events, except for heart failure hospitalizations, where the adjusted hazard ratio for women vs. men age 80 years or older was 0.95 for those without a history of CHD (95% CI, 0.91-0.98) and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.96-1.02) for participants with a previous MI.

Dr. Peters said it’s not clear why the female advantage is attenuated post-MI but that one explanation is that women are less likely than men to receive guideline-recommended treatments and dosages or to adhere to prescribed therapies after MI hospitalization, which could put them at a higher risk of subsequent events and worse outcomes than men.

“Sex differences in pathophysiology of CHD and its complications may also explain, to some extent, why the rates of recurrent events are considerably more similar between the sexes than incident event rates,” she said. Compared with men, women have a higher incidence of MI with nonobstructive coronary artery disease and of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and evidence-based treatment options are more limited for both conditions.

“After people read this, I think the important thing to recognize is we need to push– as much as we can, with what meds we have, and what data we have – secondary prevention in these women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, director of preventive cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University, Columbus, said in an interview.

The lack of a female advantage post-MI should also elicit a “really meaningful conversation with our patients on shared decision-making of why they need to be on medications, remembering on our part to prescribe the medications, remembering to prescribe cardiac rehab, and also reminding our community we do need more data and need to investigate this further,” she said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nanette Wenger, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also points out that nonobstructive coronary disease is more common in women and, “yet, guideline-based therapies are those validated for obstructive coronary disease in a predominantly male population but, nonetheless, are applied for nonobstructive coronary disease.”

She advocates for aggressive evaluation and treatment for women with chest pain symptoms as well as early identification of women at risk for CHD, specifically those with metabolic syndrome, preeclampsia, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic inflammatory conditions, and high-risk race/ethnicity.

“Next, when coronary angiography is undertaken, particularly in younger women, an assiduous search for spontaneous coronary artery dissection and its appropriate management, as well as prompt and evidence-based interventions and medical therapies for an acute coronary event [are indicated],” Dr. Wenger wrote. “However, basic to improving outcomes for women is the elucidation of the optimal noninvasive techniques to identify microvascular disease, which could then enable delineation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic approaches.”

Dr. Peters is supported by a U.K. Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship. Dr. Mehta and Dr. Wenger disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Women are known to lag 5-10 years behind men in experiencing coronary heart disease (CHD), but new research suggests the gap narrows substantially following a myocardial infarction.

“Women lose a considerable portion, but not all, of their coronary and survival advantage – i.e., the lower event rates – after suffering a MI,” study author Sanne Peters, PhD, George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, said in an interview.

Previous studies of sex differences in event rates after a coronary event have produced mixed results and were primarily focused on mortality following MI. Importantly, the studies also lacked a control group without a history of CHD and, thus, were unable to provide a reference point for the disparity in event rates, she explained.

Using the MarketScan and Medicare databases, however, Dr. Peters and colleagues matched 339,890 U.S. adults hospitalized for an MI between January 2015 and December 2016 with 1,359,560 U.S. adults without a history of CHD.

Over a median 1.3 years follow-up, there were 12,518 MIs in the non-CHD group and 27,115 recurrent MIs in the MI group.

The age-standardized rate of MI per 1,000 person-years was 4.0 in women and 6.1 in men without a history of CHD, compared with 57.6 in women and 62.7 in men with a prior MI.

After multivariate adjustment, the women-to-men hazard ratio for MI was 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.67) in the non-CHD group and 0.94 (95% CI, 0.92-0.96) in the prior MI group, the authors reported Oct. 5 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Additional results show the multivariate adjusted women-to-men hazard ratios for three other cardiovascular outcomes follow a similar pattern in the non-CHD and prior MI groups:

- CHD events: 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.54) and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.85-0.89).

- Heart failure hospitalization: 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-0.96) and 1.02 (95% CI, 1.00-1.04).

- All-cause mortality: 0.72 (95% CI, 0.71-0.73) and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.89-0.92).

“By including a control group of individuals without CHD, we demonstrated that the magnitude of the sex difference in cardiac event rates and survival is considerably smaller among those with prior MI than among those without a history of CHD,” Dr. Peters said.

Of note, the sex differences were consistent across age and race/ethnicity groups for all events, except for heart failure hospitalizations, where the adjusted hazard ratio for women vs. men age 80 years or older was 0.95 for those without a history of CHD (95% CI, 0.91-0.98) and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.96-1.02) for participants with a previous MI.

Dr. Peters said it’s not clear why the female advantage is attenuated post-MI but that one explanation is that women are less likely than men to receive guideline-recommended treatments and dosages or to adhere to prescribed therapies after MI hospitalization, which could put them at a higher risk of subsequent events and worse outcomes than men.

“Sex differences in pathophysiology of CHD and its complications may also explain, to some extent, why the rates of recurrent events are considerably more similar between the sexes than incident event rates,” she said. Compared with men, women have a higher incidence of MI with nonobstructive coronary artery disease and of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and evidence-based treatment options are more limited for both conditions.

“After people read this, I think the important thing to recognize is we need to push– as much as we can, with what meds we have, and what data we have – secondary prevention in these women,” Laxmi Mehta, MD, director of preventive cardiology and women’s cardiovascular health at Ohio State University, Columbus, said in an interview.

The lack of a female advantage post-MI should also elicit a “really meaningful conversation with our patients on shared decision-making of why they need to be on medications, remembering on our part to prescribe the medications, remembering to prescribe cardiac rehab, and also reminding our community we do need more data and need to investigate this further,” she said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nanette Wenger, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, also points out that nonobstructive coronary disease is more common in women and, “yet, guideline-based therapies are those validated for obstructive coronary disease in a predominantly male population but, nonetheless, are applied for nonobstructive coronary disease.”

She advocates for aggressive evaluation and treatment for women with chest pain symptoms as well as early identification of women at risk for CHD, specifically those with metabolic syndrome, preeclampsia, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, chronic inflammatory conditions, and high-risk race/ethnicity.

“Next, when coronary angiography is undertaken, particularly in younger women, an assiduous search for spontaneous coronary artery dissection and its appropriate management, as well as prompt and evidence-based interventions and medical therapies for an acute coronary event [are indicated],” Dr. Wenger wrote. “However, basic to improving outcomes for women is the elucidation of the optimal noninvasive techniques to identify microvascular disease, which could then enable delineation of appropriate preventive and therapeutic approaches.”

Dr. Peters is supported by a U.K. Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship. Dr. Mehta and Dr. Wenger disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

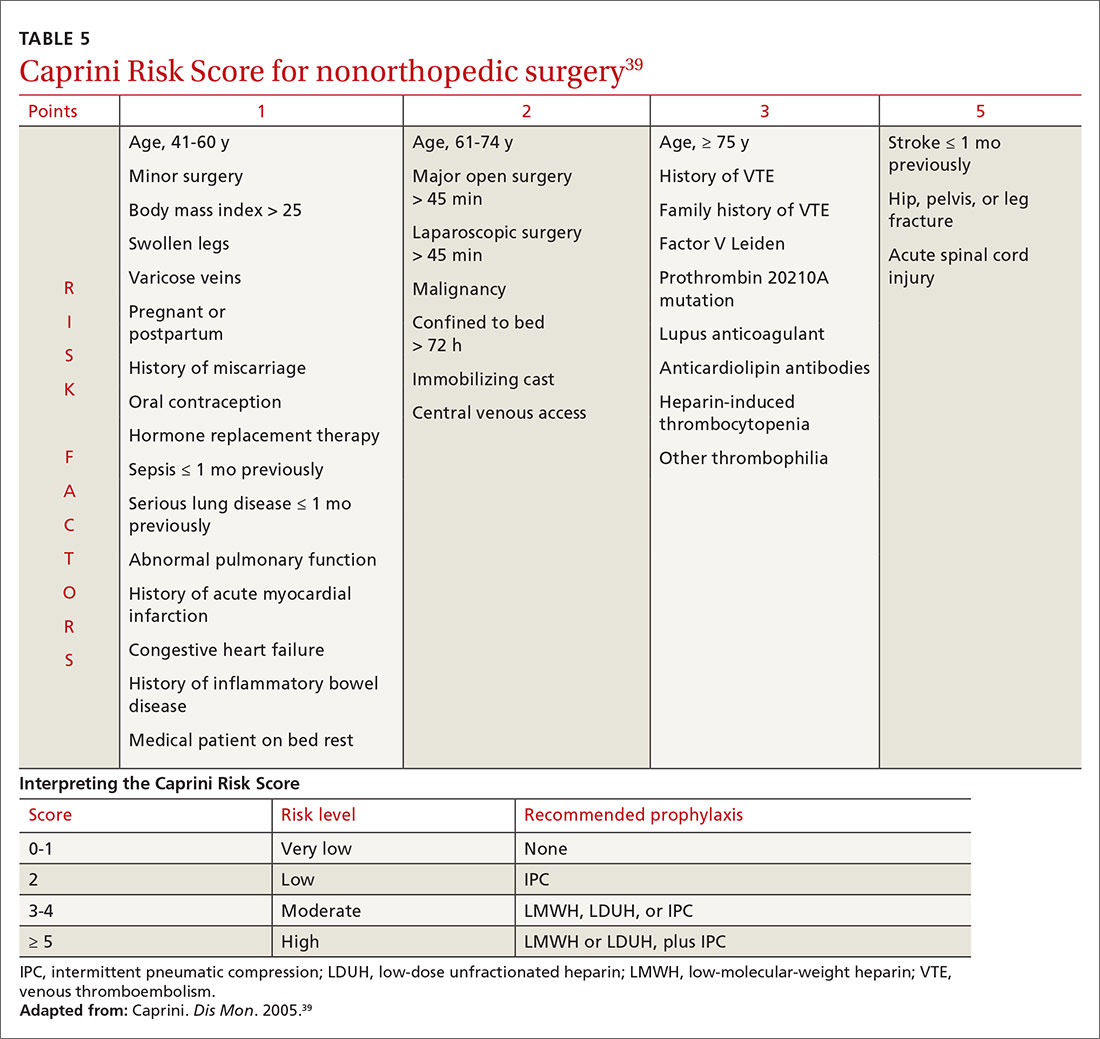

Primary prevention of VTE spans a spectrum

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common and dangerous disease, affecting 0.1%-0.2% of the population annually—a rate that might be underreported.1 VTE is a collective term for venous blood clots, including (1) deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of peripheral veins and (2) pulmonary embolism, which occurs after a clot travels through the heart and becomes lodged in the pulmonary vasculature. Two-thirds of VTE cases present clinically as DVT2; most mortality from VTE disease is caused by the 20% of cases of pulmonary embolism that present as sudden death.1

VTE is comparable to myocardial infarction (MI) in incidence and severity. In 2008, 208 of every 100,000 people had an MI, with a 30-day mortality of 16/100,0003; VTE disease has an annual incidence of 161 of every 100,000 people and a 28-day mortality of 18/100,000.4 Although the incidence and severity of MI are steadily decreasing, the rate of VTE appears constant.3,5 The high mortality of VTE suggests that primary prevention, which we discuss in this article, is valuable (see “Key points: Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism”).

SIDEBAR

Key points: Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism

- Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE), a disease with mortality similar to myocardial infarction, should be an important consideration in at-risk patients.

- Although statins reduce the risk of VTE, their use is justified only if they are also required for prevention of cardiovascular disease.

- The risk of travel-related VTE can be reduced by wearing compression stockings.

- The choice of particular methods of contraception and of hormone replacement therapy can reduce VTE risk.

- Because of the risk of bleeding, using anticoagulants for primary prevention of VTE is justified only in certain circumstances.

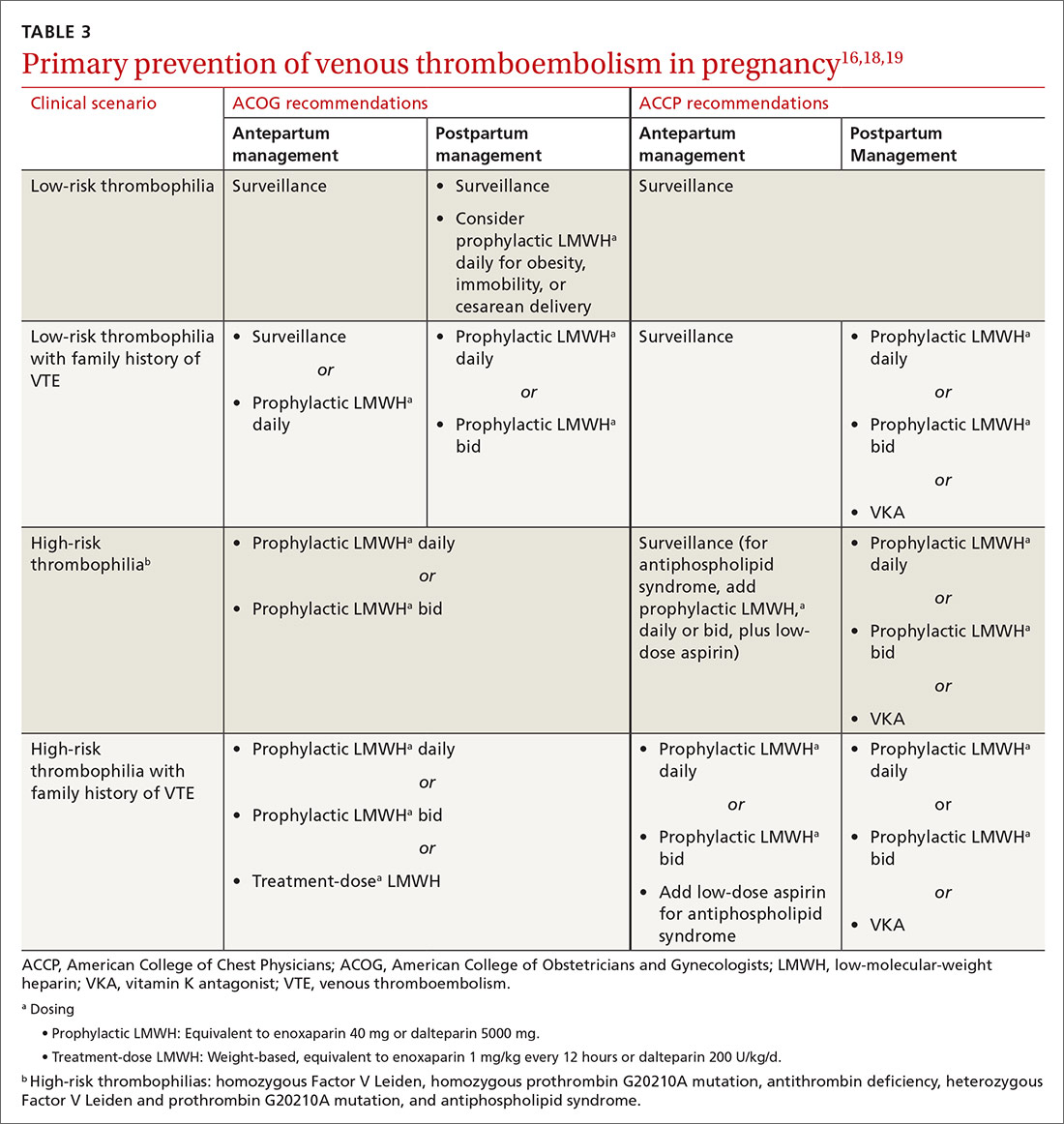

- Pregnancy is the only condition in which there is a guideline indication for thrombophilia testing, because test results in this setting can change recommendations for preventing VTE.

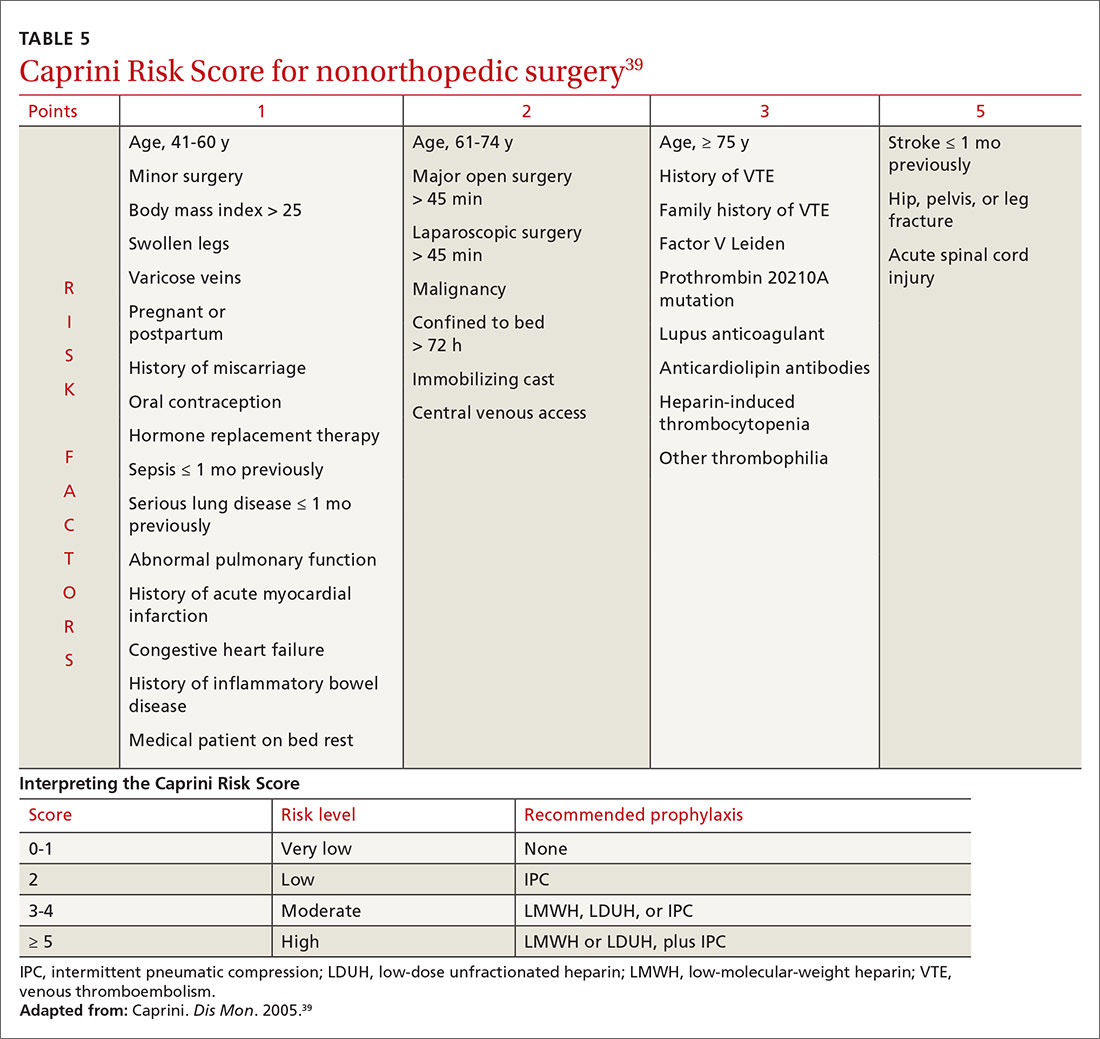

- Using a risk-stratification model is key to determining risk in both medically and surgically hospitalized patients. Trauma and major orthopedic surgery always place the patient at high risk of VTE.

Risk factors

Virchow’s triad of venous stasis, vascular injury, and hypercoagulability describes predisposing factors for VTE.6 Although venous valves promote blood flow, they produce isolated low-flow areas adjacent to valves that become concentrated and locally hypoxic, increasing the risk of clotting.7 The great majority of DVTs (≥ 96%) occur in the lower extremity,8 starting in the calf; there, 75% of cases resolve spontaneously before they extend into the deep veins of the proximal leg.7 One-half of DVTs that do move into the proximal leg eventually embolize.7

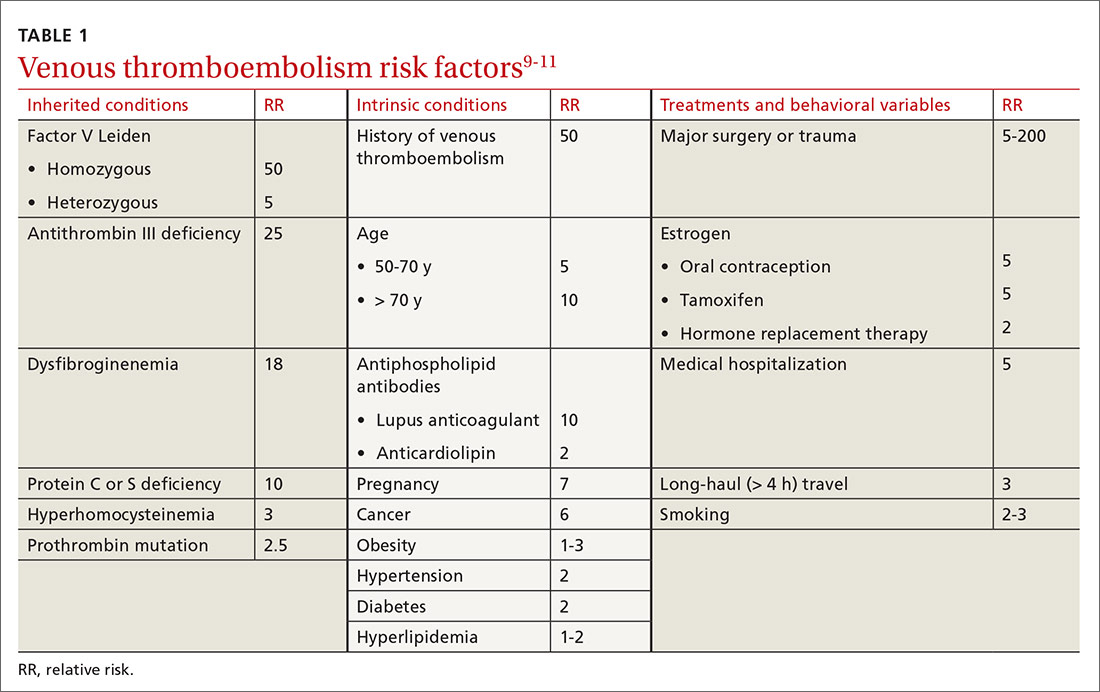

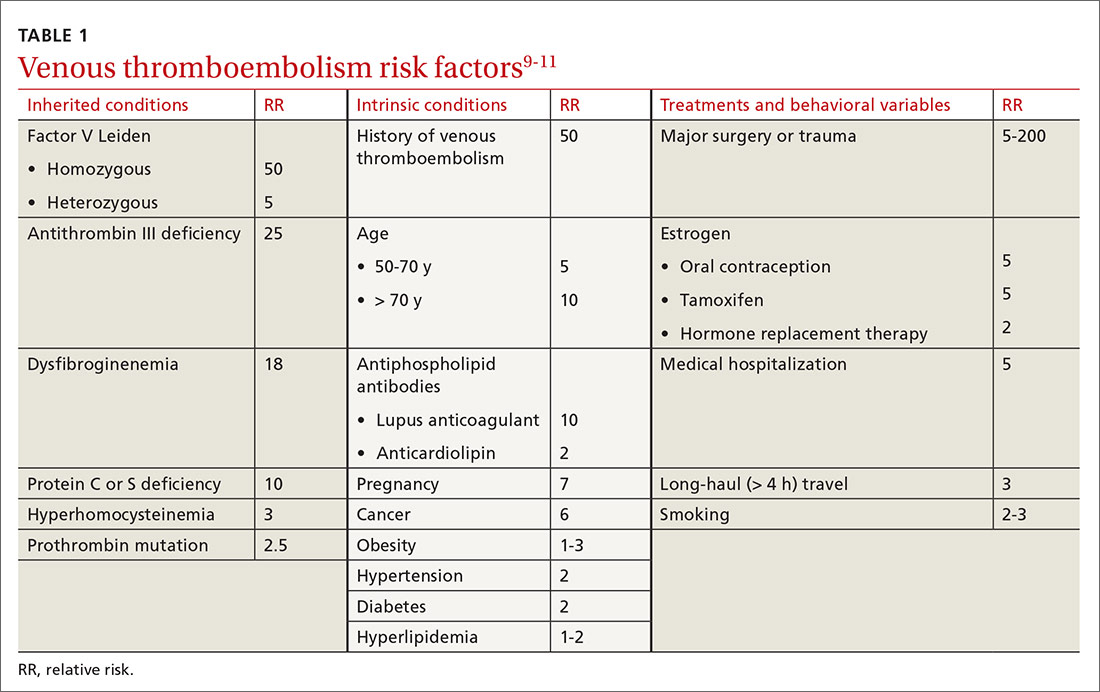

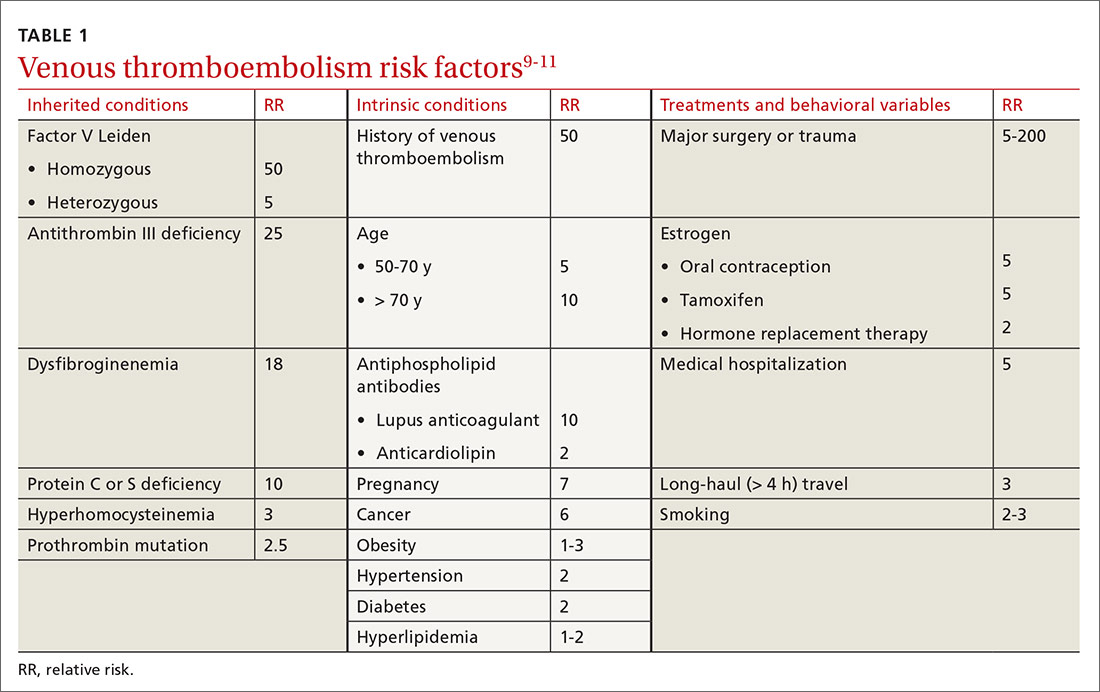

Major risk factors for VTE comprise inherited conditions, medical history, medical therapeutics, and behaviors (TABLE 1).9-11 Unlike the preventive management of coronary artery disease (CAD), there is no simple, generalized prevention algorithm to address VTE risk factors.

Risk factors for VTE and CAD overlap. Risk factors for atherosclerosis—obesity, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia—also increase the risk of VTE (TABLE 1).9-11 The association between risk factors for VTE and atherosclerosis is demonstrated by a doubling of the risk of MI and stroke in the year following VTE.11 Lifestyle changes are expected to reduce the risk of VTE, as they do for acute CAD, but studies are lacking to confirm this connection. There is no prospective evidence showing that weight loss or control of diabetes or hypertension reduces the risk of VTE.12 Smoking cessation does appear to reduce risk: Former smokers have the same VTE risk as never-smokers.13

Thrombophilia testing: Not generally useful

Inherited and acquired thrombophilic conditions define a group of disorders in which the risk of VTE is increased. Although thrombophilia testing was once considered for primary and secondary prevention of VTE, such testing is rarely used now because proof of benefit is lacking: A large case–control study showed that thrombophilia testing did not predict recurrence after a first VTE.14 Guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) do not address thrombophilia, and the American Society of Hematology recommends against thrombophilia testing after a provoked VTE.15,16

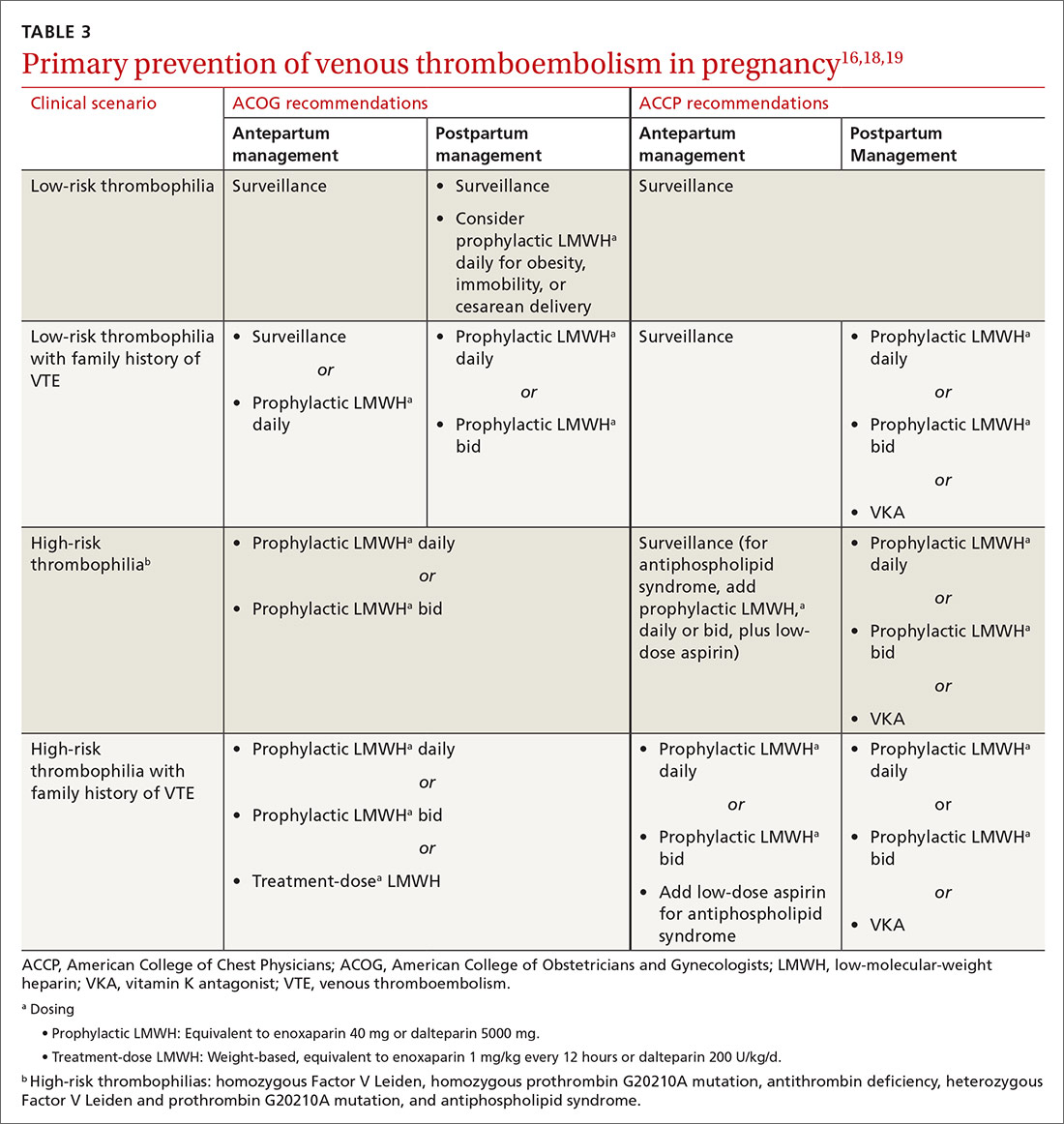

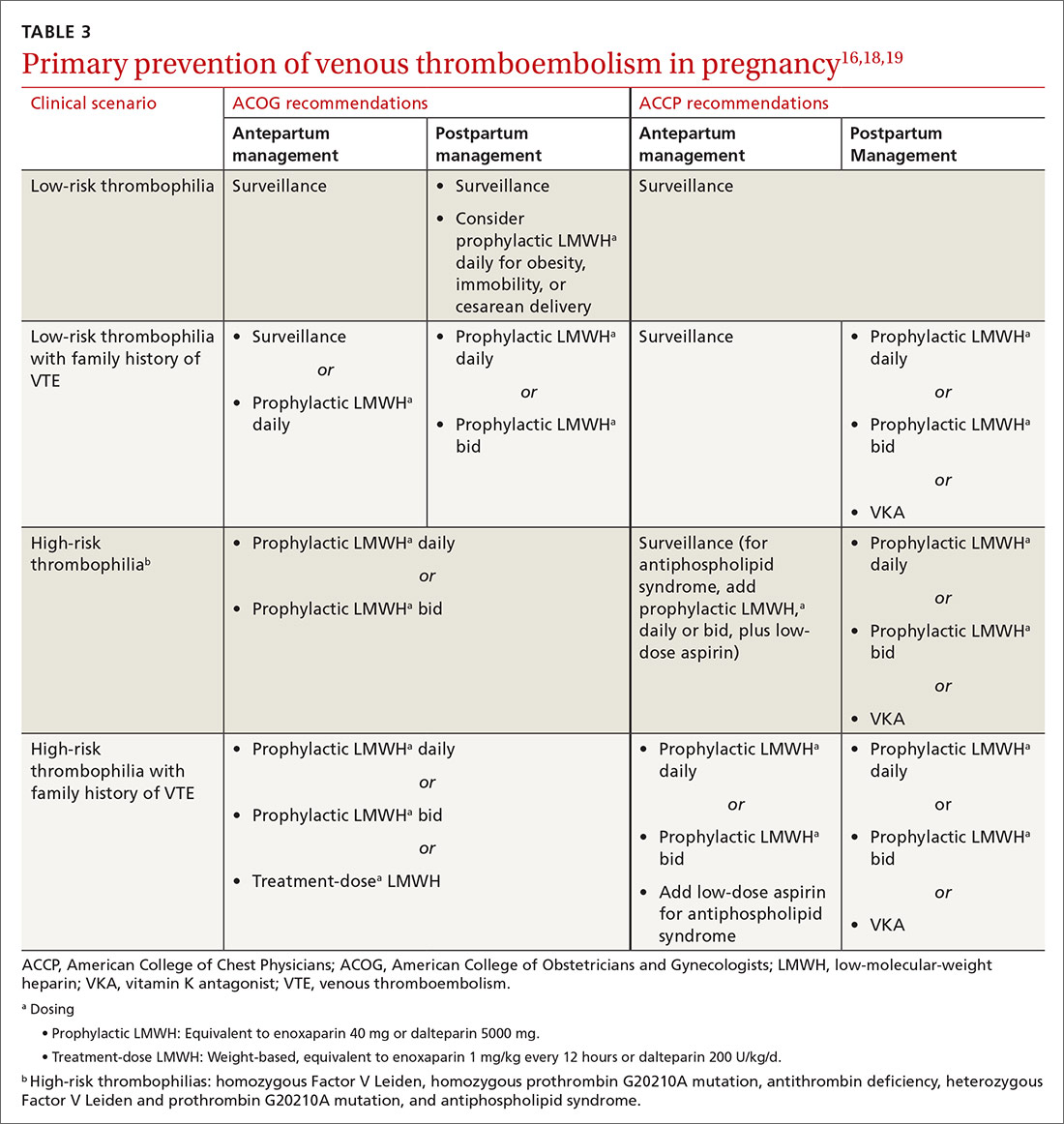

Primary prophylaxis of patients with a family history of VTE and inherited thrombophilia is controversial. Patients with both a family history of VTE and demonstrated thrombophilia do have double the average incidence of VTE, but this increased risk does not offset the significant bleeding risk associated with anticoagulation.17 Recommendations for thrombophilia testing are limited to certain situations in pregnancy, discussed in a bit.16,18,19

Continue to: Primary prevention of VTE in the clinic

Primary prevention of VTE in the clinic

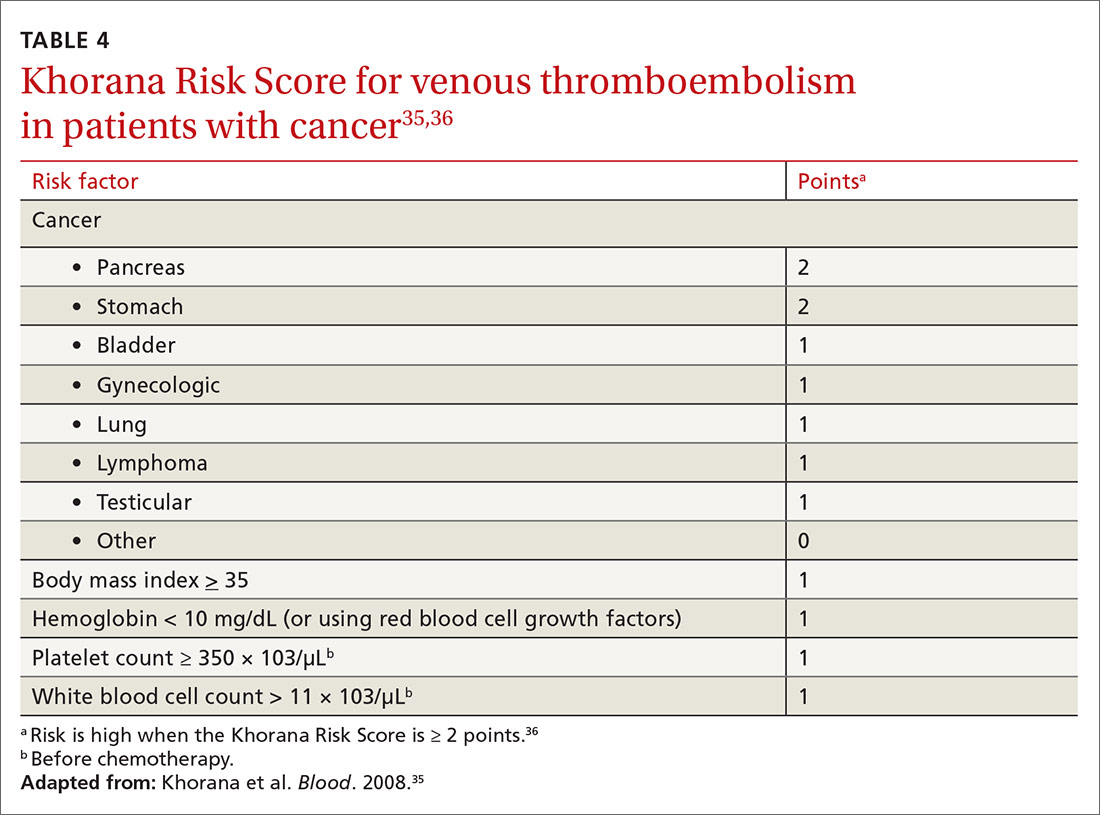

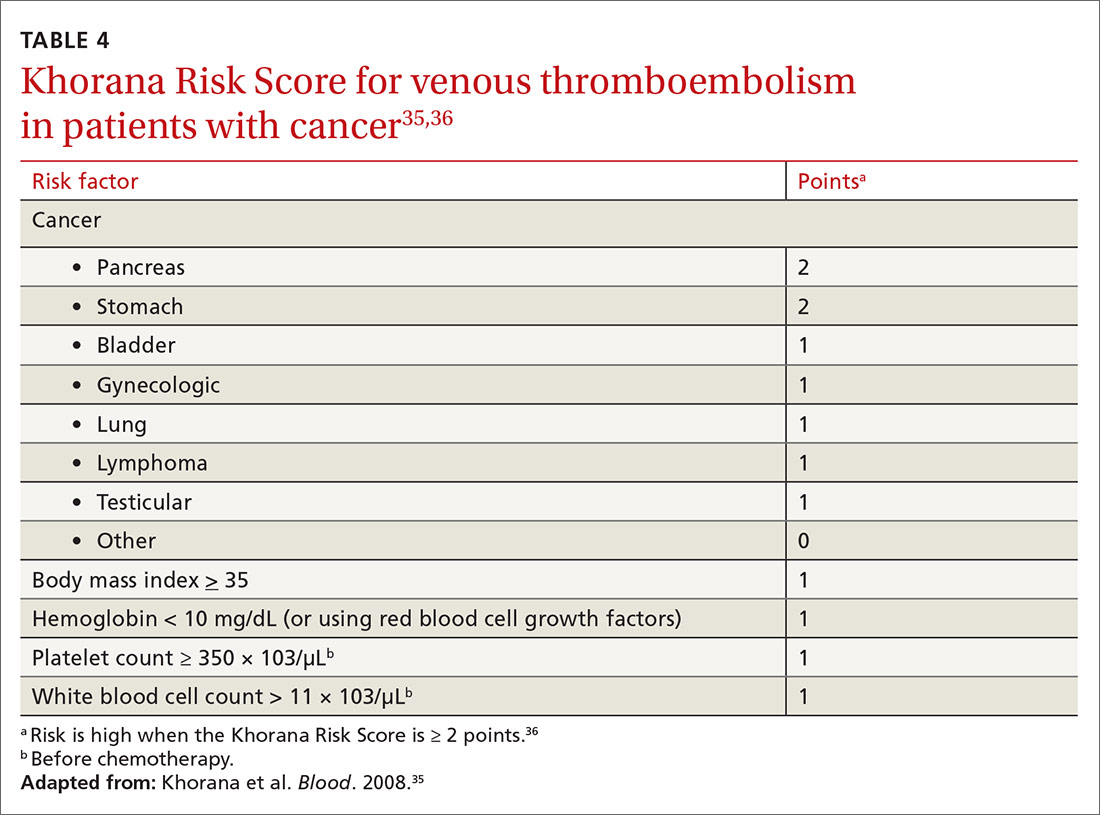

There is no single, overarching preventive strategy for VTE in an ambulatory patient (although statins, discussed in a moment, offer some benefit, broadly). There are, however, distinct behavioral characteristics and medical circumstances for which opportunities exist to reduce VTE risk—for example, when a person engages in long-distance travel, receives hormonal therapy, is pregnant, or has cancer. In each scenario, recognizing and mitigating risk are important.

Statins offer a (slight) benefit

There is evidence that statins reduce the risk of VTE—slightly20-23:

- A large randomized, controlled trial showed that rosuvastatin, 20 mg/d, reduced the rate of VTE, compared to placebo; however, the 2-year number needed to treat (NNT) was 349.20 The VTE benefit is minimal, however, compared to primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with statins (5-year NNT = 56).21 The sole significant adverse event associated with statins was new-onset type 2 diabetes (5-year number needed to harm = 235).21

- A subsequent meta-analysis confirmed a small reduction in VTE risk with statins.22 In its 2012 guidelines, ACCP declined to issue a recommendation on the use of statins for VTE prevention.23 When considering statins for primary cardiovascular disease prevention, take the additional VTE prevention into account.

Simple strategies can help prevent travel-related VTE

Travel is a common inciting factor for VTE. A systematic review showed that VTE risk triples after travel of ≥ 4 hours, increasing by 20% with each additional 2 hours.24 Most VTE occurs in travelers who have other VTE risk factors.25 Based on case–control studies,23 guidelines recommend these preventive measures:

- frequent calf exercises

- sitting in an aisle seat during air travel

- keeping hydrated.

A Cochrane review showed that graded compression stockings reduce asymptomatic DVT in travelers by a factor of 10, in high- and low-risk patients.26

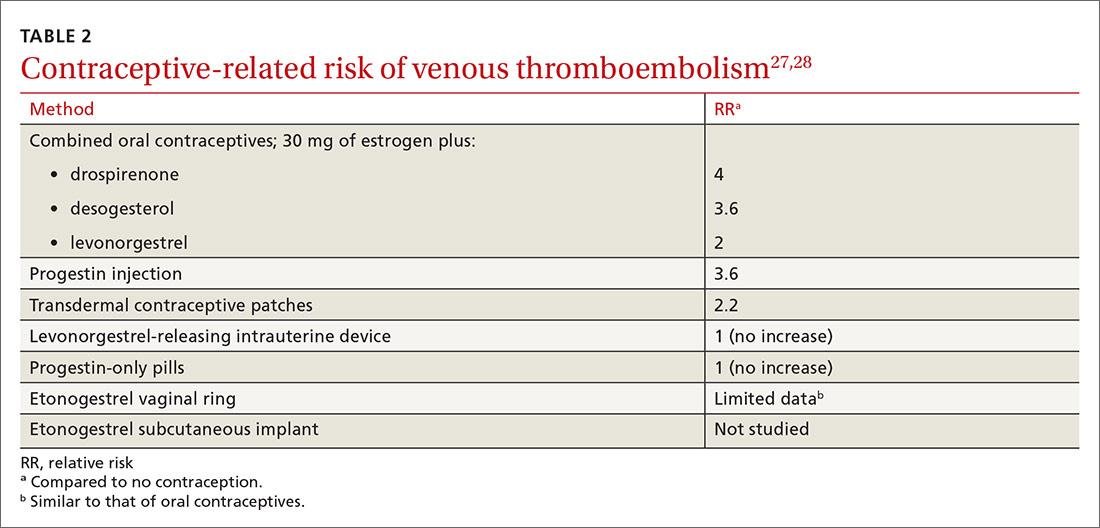

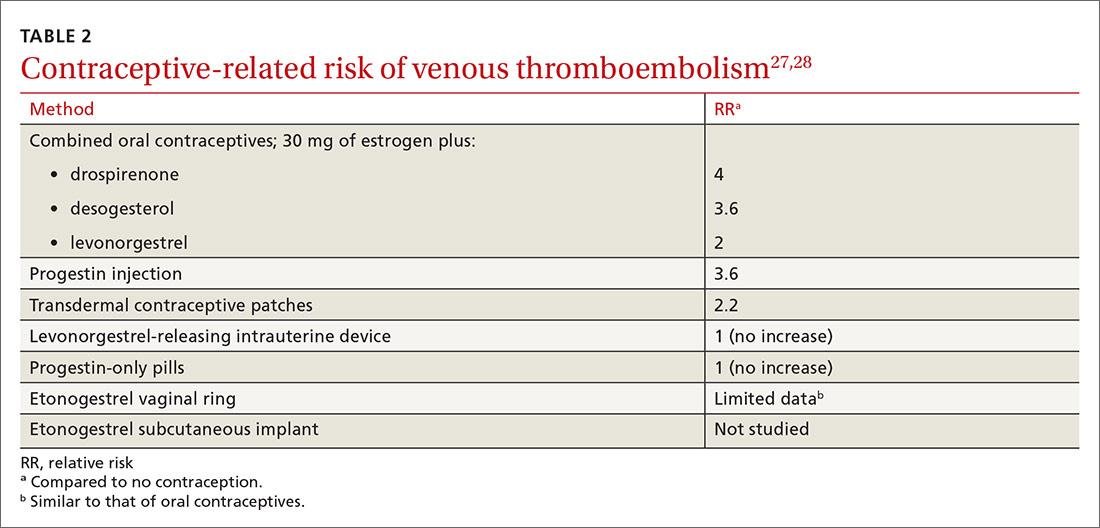

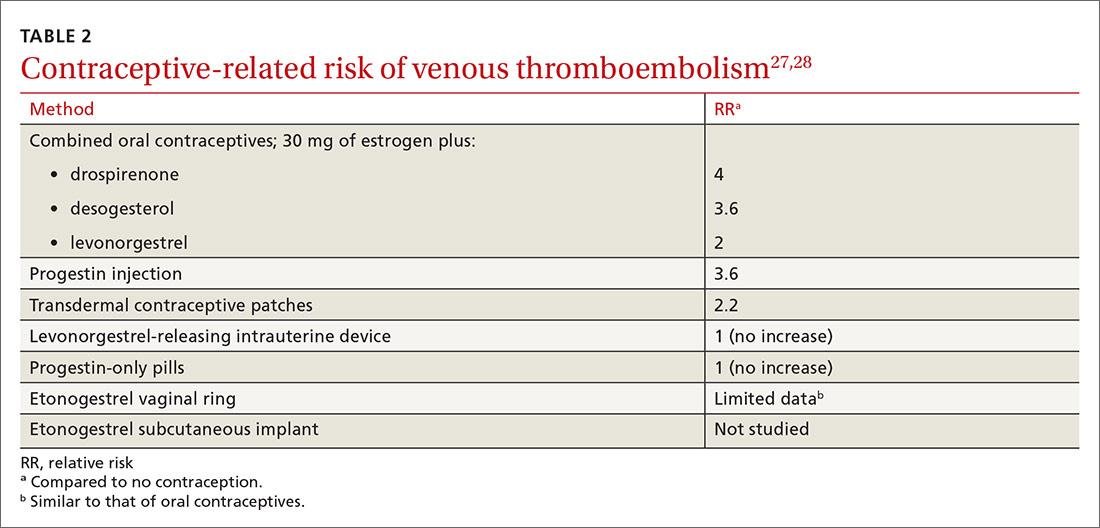

VTE risk varies with type of hormonal contraception