User login

New nonhormonal hot flash treatments on the way

researchers told attendees at the virtual North American Menopause Society 2020 Annual Meeting.

“The KNDy [kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin] neuron manipulation is really exciting and holds great promise for rapid and highly effective amelioration of hot flashes, up to 80%, and improvement in other menopausal symptoms, though we’re still looking at the safety in phase 3 trials,” reported Susan D. Reed, MD, MPH, director of the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“If we continue to see good safety data, these are going to be the greatest things since sliced bread,” Dr. Reed said in an interview. “I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this in menopause therapeutics in a long time.”

While several nonhormonal drugs are already used to treat vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women with and without breast cancer, none are as effective as hormone treatments.

“For now, the SSRIs, SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and GABAergics are the best frontline nonhormonal options with a moderate effect, and clonidine and oxybutynin are effective, but we see more side effects with these,” Dr. Reed said. She noted the importance of considering patients’ mood, sleep, pain, sexual function, weight gain, overactive bladder, blood pressure, and individual quality of life (QOL) goals in tailoring those therapies.

But women still need more nonhormonal options that are at least as effective as hormonal options, Dr. Reed said. Some women are unable to take hormonal options because they are at risk for blood clots or breast cancer.

“Then there’s preference,” she said. “Sometimes people don’t like the way they feel when they take hormones, or they just don’t want hormones in their body. It’s absolutely critical to have these options available for women.”

Nanette F. Santoro, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview that physicians may not always realize the extent to which vasomotor symptoms interfere with women’s daily lives.

“They have an eroding effect on QOL that is not appreciated sometimes,” she said. Though hot flashes eventually subside in most women, others may continue to experience them into their 70s, when hormonal therapies can begin causing more harm than benefit.

“It goes underappreciated that, for a proportion of women, hot flashes will never go away, and they’re just as bad [as] when they were in their 50s,” Dr. Santoro said. “They need to be treated, and the nonhormonal treatments do not work for everybody.”

Promising KNDy therapeutics

Autopsy studies of postmenopausal women revealed that a complex of neurons in the hypothalamus was “massively hypertrophied” and sits right next to the thermoregulatory center of the brain, Dr. Reed explained.

The complex produces three types of molecules: kisspeptin (a neuropeptide), neurokinin B (a neuropeptide), and dynorphin (a kappa opioid), collectively referred to as the KNDy. The KNDy neural complex is located in the same place as the majority of hormone receptors in the arcuate nucleus, a collection of nerve cells in the hypothalamus.

The current hypothesis is that the KNDy neurons, which communicate with each other, become hyperactivated and cause hot flashes by spilling over to and triggering the thermoregulatory center next door. NKB (kisspeptin and neurokinin B) agonists activate KNDy neurons and dynorphin agonists inactivate KNDy, so the expectation is that NKB antagonists or dynorphin agonists would stop hot flashes.

Indeed, research published in 2015 showed that women taking kappa agonists experienced fewer hot flashes than women in the placebo group. However, no peripherally restricted kappa agonists are currently in clinical trials, so their future as therapeutics is unclear.

Right now, three different NK antagonists are in the pipeline for reducing vasomotor symptoms: MLE 4901 (pavinetant) and ESN364 (fezolinetant) are both NK3R antagonists, and NT-814 is a dual NK1R/NK3R antagonist. All three of these drugs were originally developed to treat schizophrenia.

Phase 2 clinical trials of pavinetant were discontinued in November 2017 by Millendo Therapeutics because 3 of 28 women experienced abnormal liver function, which normalized within 90 days. However, the study had shown an 80% decrease in hot flashes in women taking pavinetant, compared with a 30% decrease in the placebo group.

Fezolinetant, currently in phase 3 trials with Astellas, showed a dose response effect on reproductive hormones in phase 1 studies and a short half-life (4-6 hours) in women. It also showed no concerning side effects.

“There was, in fact, a decrease in the endometrial thickness, a delayed or impeded ovulation and a prolonged cycle duration,” Reed said.

The subsequent phase 2a study showed a reduction of five hot flashes a day (93% decrease), compared with placebo (54% decrease, P <.001) “with an abrupt return to baseline hot flash frequency after cessation,” she said. Improvements also occurred in sleep quality, quality of life, disability, and interference of hot flashes in daily life.

The phase 2b study found no difference in effects between once-daily versus twice-daily doses. However, two severe adverse events occurred: a drug-induced liver injury in one woman and cholelithiasis in another, both on the 60-mg, once-daily dose. Additionally, five women on varying doses had transient increases (above 1000 U/L) in creatinine kinase, though apparently without dose response.

A 52-week, three-arm, phase 3 trial of fezolinetant is currently under way with a goal of enrolling 1,740 participants, and plans to be completed by December 2021. Participants will undergo regular adverse event screening first biweekly, then monthly, with vital signs, blood, and urine monitoring.

Meanwhile, NT-814 from KaNDy Therapeutics, has completed phase 2a and phase 2b trials with phase 3 slated to begin in 2021. Adverse events in phase 1 included sleepiness and headache, and it had a long half-life (about 26 hours) and rapid absorption (an hour).

The phase 2a trial found a reduction of five hot flashes a day, compared with placebo, with main side effects again being sleepiness and headache. No events of abnormal liver function occurred. Phase 2b results have not been published.

So far, existing research suggests that KNDy interventions will involve a single daily oral dose that begins taking effect within 3 days and is fully in effect within 1-2 weeks. The reduction in hot flashes, about five fewer a day, is more effective than any other currently used nonhormonal medications for vasomotor symptoms. SSRIs and SNRIs tend to result in 1.5-2 fewer hot flashes a day, and gabapentin results in about 3 fewer per day. It will take longer-term studies, however, and paying attention to liver concerns for the NK3R antagonists to move into clinic.

“We want to keep our eye on the [luteinizing hormone] because if it decreases too much, it could adversely affect sexual function, and this does appear to be a dose-response finding,” Dr. Reed said. It would also be ideal, she said, to target only the KNDy neurons with NK3 antagonists without effects on the NK3 receptors in the liver.

Other nonhormonal options

Oxybutynin is another a nonhormonal agent under investigation for vasomotor symptoms. It’s an anticholinergic that resulted in 80% fewer hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo in a 2016 trial, but 52% of women complained of dry mouth. A more recent study similarly found high efficacy – a 60%-80% drop in hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo – but also side effects of dry mouth, difficulty urinating, and abdominal pain.

Finally, Dr. Reed mentioned three other agents under investigation as possible nonhormonal therapeutics, though she has little information about them. They include MT-8554 by Mitsubishi Tanabe; FP-101 by Fervent Pharmaceuticals; and Q-122 by QUE Oncology with Emory University, Atlanta, and the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

None of the currently available nonhormonal options provide as high efficacy as hormones, but they do reduce symptoms:

Clonidine is an off-label option some physicians already use as a nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but again, the side effects are problematic: dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, postural hypotension, and poor sleep.

Paroxetine, at 7.5-10 mg, is the only FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but she listed other off-label options found effective in evidence reviews: gabapentin (100-2,400 mg), venlafaxine (37.5-75 mg), citalopram (10 mg), desvenlafaxine (150 mg), and escitalopram (10 mg).

“I want you to take note of the lower doses in all of these products that are efficacious above those doses that might be used for mood,” Dr. Reed added.

Dr. Reed receives royalties from UpToDate and research funding from Bayer. Dr. Santoro owns stock in MenoGeniX and serves as a consultant or advisor to Ansh Labs, MenoGeniX, and Ogeda/Astellas.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers told attendees at the virtual North American Menopause Society 2020 Annual Meeting.

“The KNDy [kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin] neuron manipulation is really exciting and holds great promise for rapid and highly effective amelioration of hot flashes, up to 80%, and improvement in other menopausal symptoms, though we’re still looking at the safety in phase 3 trials,” reported Susan D. Reed, MD, MPH, director of the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“If we continue to see good safety data, these are going to be the greatest things since sliced bread,” Dr. Reed said in an interview. “I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this in menopause therapeutics in a long time.”

While several nonhormonal drugs are already used to treat vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women with and without breast cancer, none are as effective as hormone treatments.

“For now, the SSRIs, SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and GABAergics are the best frontline nonhormonal options with a moderate effect, and clonidine and oxybutynin are effective, but we see more side effects with these,” Dr. Reed said. She noted the importance of considering patients’ mood, sleep, pain, sexual function, weight gain, overactive bladder, blood pressure, and individual quality of life (QOL) goals in tailoring those therapies.

But women still need more nonhormonal options that are at least as effective as hormonal options, Dr. Reed said. Some women are unable to take hormonal options because they are at risk for blood clots or breast cancer.

“Then there’s preference,” she said. “Sometimes people don’t like the way they feel when they take hormones, or they just don’t want hormones in their body. It’s absolutely critical to have these options available for women.”

Nanette F. Santoro, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview that physicians may not always realize the extent to which vasomotor symptoms interfere with women’s daily lives.

“They have an eroding effect on QOL that is not appreciated sometimes,” she said. Though hot flashes eventually subside in most women, others may continue to experience them into their 70s, when hormonal therapies can begin causing more harm than benefit.

“It goes underappreciated that, for a proportion of women, hot flashes will never go away, and they’re just as bad [as] when they were in their 50s,” Dr. Santoro said. “They need to be treated, and the nonhormonal treatments do not work for everybody.”

Promising KNDy therapeutics

Autopsy studies of postmenopausal women revealed that a complex of neurons in the hypothalamus was “massively hypertrophied” and sits right next to the thermoregulatory center of the brain, Dr. Reed explained.

The complex produces three types of molecules: kisspeptin (a neuropeptide), neurokinin B (a neuropeptide), and dynorphin (a kappa opioid), collectively referred to as the KNDy. The KNDy neural complex is located in the same place as the majority of hormone receptors in the arcuate nucleus, a collection of nerve cells in the hypothalamus.

The current hypothesis is that the KNDy neurons, which communicate with each other, become hyperactivated and cause hot flashes by spilling over to and triggering the thermoregulatory center next door. NKB (kisspeptin and neurokinin B) agonists activate KNDy neurons and dynorphin agonists inactivate KNDy, so the expectation is that NKB antagonists or dynorphin agonists would stop hot flashes.

Indeed, research published in 2015 showed that women taking kappa agonists experienced fewer hot flashes than women in the placebo group. However, no peripherally restricted kappa agonists are currently in clinical trials, so their future as therapeutics is unclear.

Right now, three different NK antagonists are in the pipeline for reducing vasomotor symptoms: MLE 4901 (pavinetant) and ESN364 (fezolinetant) are both NK3R antagonists, and NT-814 is a dual NK1R/NK3R antagonist. All three of these drugs were originally developed to treat schizophrenia.

Phase 2 clinical trials of pavinetant were discontinued in November 2017 by Millendo Therapeutics because 3 of 28 women experienced abnormal liver function, which normalized within 90 days. However, the study had shown an 80% decrease in hot flashes in women taking pavinetant, compared with a 30% decrease in the placebo group.

Fezolinetant, currently in phase 3 trials with Astellas, showed a dose response effect on reproductive hormones in phase 1 studies and a short half-life (4-6 hours) in women. It also showed no concerning side effects.

“There was, in fact, a decrease in the endometrial thickness, a delayed or impeded ovulation and a prolonged cycle duration,” Reed said.

The subsequent phase 2a study showed a reduction of five hot flashes a day (93% decrease), compared with placebo (54% decrease, P <.001) “with an abrupt return to baseline hot flash frequency after cessation,” she said. Improvements also occurred in sleep quality, quality of life, disability, and interference of hot flashes in daily life.

The phase 2b study found no difference in effects between once-daily versus twice-daily doses. However, two severe adverse events occurred: a drug-induced liver injury in one woman and cholelithiasis in another, both on the 60-mg, once-daily dose. Additionally, five women on varying doses had transient increases (above 1000 U/L) in creatinine kinase, though apparently without dose response.

A 52-week, three-arm, phase 3 trial of fezolinetant is currently under way with a goal of enrolling 1,740 participants, and plans to be completed by December 2021. Participants will undergo regular adverse event screening first biweekly, then monthly, with vital signs, blood, and urine monitoring.

Meanwhile, NT-814 from KaNDy Therapeutics, has completed phase 2a and phase 2b trials with phase 3 slated to begin in 2021. Adverse events in phase 1 included sleepiness and headache, and it had a long half-life (about 26 hours) and rapid absorption (an hour).

The phase 2a trial found a reduction of five hot flashes a day, compared with placebo, with main side effects again being sleepiness and headache. No events of abnormal liver function occurred. Phase 2b results have not been published.

So far, existing research suggests that KNDy interventions will involve a single daily oral dose that begins taking effect within 3 days and is fully in effect within 1-2 weeks. The reduction in hot flashes, about five fewer a day, is more effective than any other currently used nonhormonal medications for vasomotor symptoms. SSRIs and SNRIs tend to result in 1.5-2 fewer hot flashes a day, and gabapentin results in about 3 fewer per day. It will take longer-term studies, however, and paying attention to liver concerns for the NK3R antagonists to move into clinic.

“We want to keep our eye on the [luteinizing hormone] because if it decreases too much, it could adversely affect sexual function, and this does appear to be a dose-response finding,” Dr. Reed said. It would also be ideal, she said, to target only the KNDy neurons with NK3 antagonists without effects on the NK3 receptors in the liver.

Other nonhormonal options

Oxybutynin is another a nonhormonal agent under investigation for vasomotor symptoms. It’s an anticholinergic that resulted in 80% fewer hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo in a 2016 trial, but 52% of women complained of dry mouth. A more recent study similarly found high efficacy – a 60%-80% drop in hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo – but also side effects of dry mouth, difficulty urinating, and abdominal pain.

Finally, Dr. Reed mentioned three other agents under investigation as possible nonhormonal therapeutics, though she has little information about them. They include MT-8554 by Mitsubishi Tanabe; FP-101 by Fervent Pharmaceuticals; and Q-122 by QUE Oncology with Emory University, Atlanta, and the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

None of the currently available nonhormonal options provide as high efficacy as hormones, but they do reduce symptoms:

Clonidine is an off-label option some physicians already use as a nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but again, the side effects are problematic: dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, postural hypotension, and poor sleep.

Paroxetine, at 7.5-10 mg, is the only FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but she listed other off-label options found effective in evidence reviews: gabapentin (100-2,400 mg), venlafaxine (37.5-75 mg), citalopram (10 mg), desvenlafaxine (150 mg), and escitalopram (10 mg).

“I want you to take note of the lower doses in all of these products that are efficacious above those doses that might be used for mood,” Dr. Reed added.

Dr. Reed receives royalties from UpToDate and research funding from Bayer. Dr. Santoro owns stock in MenoGeniX and serves as a consultant or advisor to Ansh Labs, MenoGeniX, and Ogeda/Astellas.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers told attendees at the virtual North American Menopause Society 2020 Annual Meeting.

“The KNDy [kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin] neuron manipulation is really exciting and holds great promise for rapid and highly effective amelioration of hot flashes, up to 80%, and improvement in other menopausal symptoms, though we’re still looking at the safety in phase 3 trials,” reported Susan D. Reed, MD, MPH, director of the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

“If we continue to see good safety data, these are going to be the greatest things since sliced bread,” Dr. Reed said in an interview. “I don’t think we’ve seen anything like this in menopause therapeutics in a long time.”

While several nonhormonal drugs are already used to treat vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women with and without breast cancer, none are as effective as hormone treatments.

“For now, the SSRIs, SNRIs [serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors], and GABAergics are the best frontline nonhormonal options with a moderate effect, and clonidine and oxybutynin are effective, but we see more side effects with these,” Dr. Reed said. She noted the importance of considering patients’ mood, sleep, pain, sexual function, weight gain, overactive bladder, blood pressure, and individual quality of life (QOL) goals in tailoring those therapies.

But women still need more nonhormonal options that are at least as effective as hormonal options, Dr. Reed said. Some women are unable to take hormonal options because they are at risk for blood clots or breast cancer.

“Then there’s preference,” she said. “Sometimes people don’t like the way they feel when they take hormones, or they just don’t want hormones in their body. It’s absolutely critical to have these options available for women.”

Nanette F. Santoro, MD, a professor of ob.gyn. at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who was not involved in the presentation, said in an interview that physicians may not always realize the extent to which vasomotor symptoms interfere with women’s daily lives.

“They have an eroding effect on QOL that is not appreciated sometimes,” she said. Though hot flashes eventually subside in most women, others may continue to experience them into their 70s, when hormonal therapies can begin causing more harm than benefit.

“It goes underappreciated that, for a proportion of women, hot flashes will never go away, and they’re just as bad [as] when they were in their 50s,” Dr. Santoro said. “They need to be treated, and the nonhormonal treatments do not work for everybody.”

Promising KNDy therapeutics

Autopsy studies of postmenopausal women revealed that a complex of neurons in the hypothalamus was “massively hypertrophied” and sits right next to the thermoregulatory center of the brain, Dr. Reed explained.

The complex produces three types of molecules: kisspeptin (a neuropeptide), neurokinin B (a neuropeptide), and dynorphin (a kappa opioid), collectively referred to as the KNDy. The KNDy neural complex is located in the same place as the majority of hormone receptors in the arcuate nucleus, a collection of nerve cells in the hypothalamus.

The current hypothesis is that the KNDy neurons, which communicate with each other, become hyperactivated and cause hot flashes by spilling over to and triggering the thermoregulatory center next door. NKB (kisspeptin and neurokinin B) agonists activate KNDy neurons and dynorphin agonists inactivate KNDy, so the expectation is that NKB antagonists or dynorphin agonists would stop hot flashes.

Indeed, research published in 2015 showed that women taking kappa agonists experienced fewer hot flashes than women in the placebo group. However, no peripherally restricted kappa agonists are currently in clinical trials, so their future as therapeutics is unclear.

Right now, three different NK antagonists are in the pipeline for reducing vasomotor symptoms: MLE 4901 (pavinetant) and ESN364 (fezolinetant) are both NK3R antagonists, and NT-814 is a dual NK1R/NK3R antagonist. All three of these drugs were originally developed to treat schizophrenia.

Phase 2 clinical trials of pavinetant were discontinued in November 2017 by Millendo Therapeutics because 3 of 28 women experienced abnormal liver function, which normalized within 90 days. However, the study had shown an 80% decrease in hot flashes in women taking pavinetant, compared with a 30% decrease in the placebo group.

Fezolinetant, currently in phase 3 trials with Astellas, showed a dose response effect on reproductive hormones in phase 1 studies and a short half-life (4-6 hours) in women. It also showed no concerning side effects.

“There was, in fact, a decrease in the endometrial thickness, a delayed or impeded ovulation and a prolonged cycle duration,” Reed said.

The subsequent phase 2a study showed a reduction of five hot flashes a day (93% decrease), compared with placebo (54% decrease, P <.001) “with an abrupt return to baseline hot flash frequency after cessation,” she said. Improvements also occurred in sleep quality, quality of life, disability, and interference of hot flashes in daily life.

The phase 2b study found no difference in effects between once-daily versus twice-daily doses. However, two severe adverse events occurred: a drug-induced liver injury in one woman and cholelithiasis in another, both on the 60-mg, once-daily dose. Additionally, five women on varying doses had transient increases (above 1000 U/L) in creatinine kinase, though apparently without dose response.

A 52-week, three-arm, phase 3 trial of fezolinetant is currently under way with a goal of enrolling 1,740 participants, and plans to be completed by December 2021. Participants will undergo regular adverse event screening first biweekly, then monthly, with vital signs, blood, and urine monitoring.

Meanwhile, NT-814 from KaNDy Therapeutics, has completed phase 2a and phase 2b trials with phase 3 slated to begin in 2021. Adverse events in phase 1 included sleepiness and headache, and it had a long half-life (about 26 hours) and rapid absorption (an hour).

The phase 2a trial found a reduction of five hot flashes a day, compared with placebo, with main side effects again being sleepiness and headache. No events of abnormal liver function occurred. Phase 2b results have not been published.

So far, existing research suggests that KNDy interventions will involve a single daily oral dose that begins taking effect within 3 days and is fully in effect within 1-2 weeks. The reduction in hot flashes, about five fewer a day, is more effective than any other currently used nonhormonal medications for vasomotor symptoms. SSRIs and SNRIs tend to result in 1.5-2 fewer hot flashes a day, and gabapentin results in about 3 fewer per day. It will take longer-term studies, however, and paying attention to liver concerns for the NK3R antagonists to move into clinic.

“We want to keep our eye on the [luteinizing hormone] because if it decreases too much, it could adversely affect sexual function, and this does appear to be a dose-response finding,” Dr. Reed said. It would also be ideal, she said, to target only the KNDy neurons with NK3 antagonists without effects on the NK3 receptors in the liver.

Other nonhormonal options

Oxybutynin is another a nonhormonal agent under investigation for vasomotor symptoms. It’s an anticholinergic that resulted in 80% fewer hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo in a 2016 trial, but 52% of women complained of dry mouth. A more recent study similarly found high efficacy – a 60%-80% drop in hot flashes, compared with 30% with placebo – but also side effects of dry mouth, difficulty urinating, and abdominal pain.

Finally, Dr. Reed mentioned three other agents under investigation as possible nonhormonal therapeutics, though she has little information about them. They include MT-8554 by Mitsubishi Tanabe; FP-101 by Fervent Pharmaceuticals; and Q-122 by QUE Oncology with Emory University, Atlanta, and the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

None of the currently available nonhormonal options provide as high efficacy as hormones, but they do reduce symptoms:

Clonidine is an off-label option some physicians already use as a nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but again, the side effects are problematic: dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, postural hypotension, and poor sleep.

Paroxetine, at 7.5-10 mg, is the only FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but she listed other off-label options found effective in evidence reviews: gabapentin (100-2,400 mg), venlafaxine (37.5-75 mg), citalopram (10 mg), desvenlafaxine (150 mg), and escitalopram (10 mg).

“I want you to take note of the lower doses in all of these products that are efficacious above those doses that might be used for mood,” Dr. Reed added.

Dr. Reed receives royalties from UpToDate and research funding from Bayer. Dr. Santoro owns stock in MenoGeniX and serves as a consultant or advisor to Ansh Labs, MenoGeniX, and Ogeda/Astellas.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA proposes withdrawing Makena’s approval

Makena should be withdrawn from the market because a postmarketing study did not show clinical benefit, according to a statement released today from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the Food and Drug Administration.

The drug, hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection, was approved in 2011 to reduce the risk of preterm birth in women who with previous spontaneous preterm birth. The FDA approved the medication under an accelerated pathway that required another trial to confirm clinical benefit.

The required postmarketing study “not only failed to demonstrate Makena’s benefit to the neonate, but also failed to substantiate any effect of Makena on the surrogate endpoint of gestational age at delivery that was the basis of the initial approval,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, acting director of the CDER, wrote in a letter to AMAG Pharma USA, which markets Makena. The letter also was sent to other companies developing products that use the drug.

Beyond the lack of efficacy, risks associated with the drug include thromboembolic disorders, allergic reactions, decreased glucose tolerance, and fluid retention. “The risk of exposing treated pregnant women to these harms, in addition to false hopes, costs, and additional healthcare utilization outweighs Makena’s unproven benefit,” Dr. Cavazzoni said.

The letter notifies companies about the opportunity for a hearing on the proposed withdrawal of marketing approval. Makena and its generic equivalents will remain on the market until the manufacturers remove the drugs or the FDA commissioner mandates their removal, the CDER said.

The FDA commissioner ultimately will decide whether to withdraw approval of the drug. An FDA panel previously voted to withdraw the drug from the market in October 2019, and the drug has remained in limbo since.

Health care professionals should discuss “Makena’s benefits, risks, and uncertainties with their patients to decide whether to use Makena while a final decision is being made about the drug’s marketing status,” the CDER announcement said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Makena should be withdrawn from the market because a postmarketing study did not show clinical benefit, according to a statement released today from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the Food and Drug Administration.

The drug, hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection, was approved in 2011 to reduce the risk of preterm birth in women who with previous spontaneous preterm birth. The FDA approved the medication under an accelerated pathway that required another trial to confirm clinical benefit.

The required postmarketing study “not only failed to demonstrate Makena’s benefit to the neonate, but also failed to substantiate any effect of Makena on the surrogate endpoint of gestational age at delivery that was the basis of the initial approval,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, acting director of the CDER, wrote in a letter to AMAG Pharma USA, which markets Makena. The letter also was sent to other companies developing products that use the drug.

Beyond the lack of efficacy, risks associated with the drug include thromboembolic disorders, allergic reactions, decreased glucose tolerance, and fluid retention. “The risk of exposing treated pregnant women to these harms, in addition to false hopes, costs, and additional healthcare utilization outweighs Makena’s unproven benefit,” Dr. Cavazzoni said.

The letter notifies companies about the opportunity for a hearing on the proposed withdrawal of marketing approval. Makena and its generic equivalents will remain on the market until the manufacturers remove the drugs or the FDA commissioner mandates their removal, the CDER said.

The FDA commissioner ultimately will decide whether to withdraw approval of the drug. An FDA panel previously voted to withdraw the drug from the market in October 2019, and the drug has remained in limbo since.

Health care professionals should discuss “Makena’s benefits, risks, and uncertainties with their patients to decide whether to use Makena while a final decision is being made about the drug’s marketing status,” the CDER announcement said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Makena should be withdrawn from the market because a postmarketing study did not show clinical benefit, according to a statement released today from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the Food and Drug Administration.

The drug, hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection, was approved in 2011 to reduce the risk of preterm birth in women who with previous spontaneous preterm birth. The FDA approved the medication under an accelerated pathway that required another trial to confirm clinical benefit.

The required postmarketing study “not only failed to demonstrate Makena’s benefit to the neonate, but also failed to substantiate any effect of Makena on the surrogate endpoint of gestational age at delivery that was the basis of the initial approval,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, acting director of the CDER, wrote in a letter to AMAG Pharma USA, which markets Makena. The letter also was sent to other companies developing products that use the drug.

Beyond the lack of efficacy, risks associated with the drug include thromboembolic disorders, allergic reactions, decreased glucose tolerance, and fluid retention. “The risk of exposing treated pregnant women to these harms, in addition to false hopes, costs, and additional healthcare utilization outweighs Makena’s unproven benefit,” Dr. Cavazzoni said.

The letter notifies companies about the opportunity for a hearing on the proposed withdrawal of marketing approval. Makena and its generic equivalents will remain on the market until the manufacturers remove the drugs or the FDA commissioner mandates their removal, the CDER said.

The FDA commissioner ultimately will decide whether to withdraw approval of the drug. An FDA panel previously voted to withdraw the drug from the market in October 2019, and the drug has remained in limbo since.

Health care professionals should discuss “Makena’s benefits, risks, and uncertainties with their patients to decide whether to use Makena while a final decision is being made about the drug’s marketing status,” the CDER announcement said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA updates info on postmarketing surveillance study of Essure

The Food and Drug Administration has updated its page on Essure information for patients and health care providers to add additional information on adverse events reported by its manufacturer.

Essure was a permanent implantable birth control device approved by the FDA in 2002. FDA ordered Bayer in 2016 to conduct a postmarket surveillance study of Essure following reports of safety concerns, and expanded the study from 3 years to 5 years in 2018. Bayer voluntarily removed Essure from the market at the end of 2018, citing low sales after a “black box” warning was placed on the device. All devices were returned to the company by the end of 2019.

Bayer is required to report variances in Medical Device Reporting (MDR) requirements of Essure related to litigation to the FDA, which includes adverse events such death, serious injury, and “malfunction that would be likely to cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the malfunction were to recur.” The reports are limited to events Bayer becomes aware of between November 2016 and November 2020. Bayer will continue to provide these reports until April 2021.

The FDA emphasized that the collected data are based on social media reports and already may be reported to the FDA, rather than being a collection of new events. “The limited information provided in the reports prevents the ability to draw any conclusions as to whether the device, or its removal, caused or contributed to any of the events in the reports,” Benjamin Fisher, PhD, director of the Reproductive, Gastro-Renal, Urological, General Hospital Device and Human Factors Office in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an FDA In Brief statement on Aug. 11.

The FDA first uploaded an Essure MDR variance spreadsheet in August 2020, listing 1,453 events, consisting of 53 reports of deaths, 1,376 reports of serious injury, and 24 reports of device malfunction that occurred as of June 2020. In September 2020, FDA uploaded a second variance spreadsheet, which added another 1,934 events that occurred as of July.

Interim analysis of postmarketing surveillance study

An interim analysis of 1,128 patients from 67 centers in the Essure postmarket surveillance study, which compared women who received Essure with those who received laparoscopic tubal sterilization, revealed that 94.6% (265 of 280 patients) in the Essure group had a successful implantation of the device, compared with 99.6% of women who achieved bilateral tubal occlusion from laparoscopic tubal sterilization.

Regarding safety, 9.1% of women in the Essure group and 4.5% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported chronic lower abdominal and/or pelvic pain, and 16.3% in the Essure group and 10.2% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported new or worsening abnormal uterine bleeding. In the Essure group, 22.3% of women said they experienced hypersensitivity, an allergic reaction, and new “autoimmune-like reactions” compared with 12.5% of women in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group.

The interim analysis also showed 19.7% of women in the Essure group and 3.0% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group underwent gynecologic surgical procedures, which were “driven primarily by Essure removal and endometrial ablation procedures in Essure patients.” Device removal occurred in 6.8% of women with the Essure device.

Consistent data on Essure

An FDA search of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database in January of 2020 revealed 47,856 medical device reports of Essure between November 2002 and December 2019. The most common adverse events observed during this period were:

- Pain or abdominal pain (32,901 cases).

- Heavy or irregular menses (14,573 cases). Headache (8,570 cases).

- Device fragment or foreign body in a patient (8,501 cases).

- Perforation (7,825 cases).

- Fatigue (7,083 cases).

- Gain or loss in weight (5,980 cases).

- Anxiety and/or depression (5,366 cases).

- Rash and/or hypersensitivity (5,077 cases)

- Hair loss (4,999 cases).

Problems with the device itself included reports of:

- Device incompatibility such as an allergy (7,515 cases).

- The device migrating (4,535 cases).

- The device breaking or fracturing (2,297 cases).

- The device dislodging or dislocating (1,797 cases).

- Improper operation including implant failure and pregnancy (1,058 cases).

In 2019, Essure received 15,083 medical device reports, an increase from 6,000 reports in 2018 and 11,854 reports in 2017.

To date, nearly 39,000 women in the United States have made claims to injuries related to the Essure device. In August, Bayer announced it would pay approximately $1.6 billion U.S. dollars to settle 90% of these cases in exchange for claimants to “dismiss their cases or not file.” Bayer also said in a press release that the settlement is not an admission of wrongdoing or liability on the part of the company.

In an interview, Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said the latest adverse event reports show “consistent info from [the] MAUDE database when comparing 2019 to previous years, highlighting most common problems related to pain and heavy or irregular bleeding.”

She emphasized ob.gyns with patients who have an Essure device should “consider Essure-related etiology that may necessitate device removal when evaluating patients with gynecological problems, especially with regard to abdominal/pelvic pain and heavy/irregular bleeding.”

Dr. Cansino reported no relevant financial disclosures. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

The Food and Drug Administration has updated its page on Essure information for patients and health care providers to add additional information on adverse events reported by its manufacturer.

Essure was a permanent implantable birth control device approved by the FDA in 2002. FDA ordered Bayer in 2016 to conduct a postmarket surveillance study of Essure following reports of safety concerns, and expanded the study from 3 years to 5 years in 2018. Bayer voluntarily removed Essure from the market at the end of 2018, citing low sales after a “black box” warning was placed on the device. All devices were returned to the company by the end of 2019.

Bayer is required to report variances in Medical Device Reporting (MDR) requirements of Essure related to litigation to the FDA, which includes adverse events such death, serious injury, and “malfunction that would be likely to cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the malfunction were to recur.” The reports are limited to events Bayer becomes aware of between November 2016 and November 2020. Bayer will continue to provide these reports until April 2021.

The FDA emphasized that the collected data are based on social media reports and already may be reported to the FDA, rather than being a collection of new events. “The limited information provided in the reports prevents the ability to draw any conclusions as to whether the device, or its removal, caused or contributed to any of the events in the reports,” Benjamin Fisher, PhD, director of the Reproductive, Gastro-Renal, Urological, General Hospital Device and Human Factors Office in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an FDA In Brief statement on Aug. 11.

The FDA first uploaded an Essure MDR variance spreadsheet in August 2020, listing 1,453 events, consisting of 53 reports of deaths, 1,376 reports of serious injury, and 24 reports of device malfunction that occurred as of June 2020. In September 2020, FDA uploaded a second variance spreadsheet, which added another 1,934 events that occurred as of July.

Interim analysis of postmarketing surveillance study

An interim analysis of 1,128 patients from 67 centers in the Essure postmarket surveillance study, which compared women who received Essure with those who received laparoscopic tubal sterilization, revealed that 94.6% (265 of 280 patients) in the Essure group had a successful implantation of the device, compared with 99.6% of women who achieved bilateral tubal occlusion from laparoscopic tubal sterilization.

Regarding safety, 9.1% of women in the Essure group and 4.5% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported chronic lower abdominal and/or pelvic pain, and 16.3% in the Essure group and 10.2% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported new or worsening abnormal uterine bleeding. In the Essure group, 22.3% of women said they experienced hypersensitivity, an allergic reaction, and new “autoimmune-like reactions” compared with 12.5% of women in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group.

The interim analysis also showed 19.7% of women in the Essure group and 3.0% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group underwent gynecologic surgical procedures, which were “driven primarily by Essure removal and endometrial ablation procedures in Essure patients.” Device removal occurred in 6.8% of women with the Essure device.

Consistent data on Essure

An FDA search of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database in January of 2020 revealed 47,856 medical device reports of Essure between November 2002 and December 2019. The most common adverse events observed during this period were:

- Pain or abdominal pain (32,901 cases).

- Heavy or irregular menses (14,573 cases). Headache (8,570 cases).

- Device fragment or foreign body in a patient (8,501 cases).

- Perforation (7,825 cases).

- Fatigue (7,083 cases).

- Gain or loss in weight (5,980 cases).

- Anxiety and/or depression (5,366 cases).

- Rash and/or hypersensitivity (5,077 cases)

- Hair loss (4,999 cases).

Problems with the device itself included reports of:

- Device incompatibility such as an allergy (7,515 cases).

- The device migrating (4,535 cases).

- The device breaking or fracturing (2,297 cases).

- The device dislodging or dislocating (1,797 cases).

- Improper operation including implant failure and pregnancy (1,058 cases).

In 2019, Essure received 15,083 medical device reports, an increase from 6,000 reports in 2018 and 11,854 reports in 2017.

To date, nearly 39,000 women in the United States have made claims to injuries related to the Essure device. In August, Bayer announced it would pay approximately $1.6 billion U.S. dollars to settle 90% of these cases in exchange for claimants to “dismiss their cases or not file.” Bayer also said in a press release that the settlement is not an admission of wrongdoing or liability on the part of the company.

In an interview, Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said the latest adverse event reports show “consistent info from [the] MAUDE database when comparing 2019 to previous years, highlighting most common problems related to pain and heavy or irregular bleeding.”

She emphasized ob.gyns with patients who have an Essure device should “consider Essure-related etiology that may necessitate device removal when evaluating patients with gynecological problems, especially with regard to abdominal/pelvic pain and heavy/irregular bleeding.”

Dr. Cansino reported no relevant financial disclosures. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

The Food and Drug Administration has updated its page on Essure information for patients and health care providers to add additional information on adverse events reported by its manufacturer.

Essure was a permanent implantable birth control device approved by the FDA in 2002. FDA ordered Bayer in 2016 to conduct a postmarket surveillance study of Essure following reports of safety concerns, and expanded the study from 3 years to 5 years in 2018. Bayer voluntarily removed Essure from the market at the end of 2018, citing low sales after a “black box” warning was placed on the device. All devices were returned to the company by the end of 2019.

Bayer is required to report variances in Medical Device Reporting (MDR) requirements of Essure related to litigation to the FDA, which includes adverse events such death, serious injury, and “malfunction that would be likely to cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the malfunction were to recur.” The reports are limited to events Bayer becomes aware of between November 2016 and November 2020. Bayer will continue to provide these reports until April 2021.

The FDA emphasized that the collected data are based on social media reports and already may be reported to the FDA, rather than being a collection of new events. “The limited information provided in the reports prevents the ability to draw any conclusions as to whether the device, or its removal, caused or contributed to any of the events in the reports,” Benjamin Fisher, PhD, director of the Reproductive, Gastro-Renal, Urological, General Hospital Device and Human Factors Office in the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an FDA In Brief statement on Aug. 11.

The FDA first uploaded an Essure MDR variance spreadsheet in August 2020, listing 1,453 events, consisting of 53 reports of deaths, 1,376 reports of serious injury, and 24 reports of device malfunction that occurred as of June 2020. In September 2020, FDA uploaded a second variance spreadsheet, which added another 1,934 events that occurred as of July.

Interim analysis of postmarketing surveillance study

An interim analysis of 1,128 patients from 67 centers in the Essure postmarket surveillance study, which compared women who received Essure with those who received laparoscopic tubal sterilization, revealed that 94.6% (265 of 280 patients) in the Essure group had a successful implantation of the device, compared with 99.6% of women who achieved bilateral tubal occlusion from laparoscopic tubal sterilization.

Regarding safety, 9.1% of women in the Essure group and 4.5% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported chronic lower abdominal and/or pelvic pain, and 16.3% in the Essure group and 10.2% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group reported new or worsening abnormal uterine bleeding. In the Essure group, 22.3% of women said they experienced hypersensitivity, an allergic reaction, and new “autoimmune-like reactions” compared with 12.5% of women in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group.

The interim analysis also showed 19.7% of women in the Essure group and 3.0% in the laparoscopic tubal sterilization group underwent gynecologic surgical procedures, which were “driven primarily by Essure removal and endometrial ablation procedures in Essure patients.” Device removal occurred in 6.8% of women with the Essure device.

Consistent data on Essure

An FDA search of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database in January of 2020 revealed 47,856 medical device reports of Essure between November 2002 and December 2019. The most common adverse events observed during this period were:

- Pain or abdominal pain (32,901 cases).

- Heavy or irregular menses (14,573 cases). Headache (8,570 cases).

- Device fragment or foreign body in a patient (8,501 cases).

- Perforation (7,825 cases).

- Fatigue (7,083 cases).

- Gain or loss in weight (5,980 cases).

- Anxiety and/or depression (5,366 cases).

- Rash and/or hypersensitivity (5,077 cases)

- Hair loss (4,999 cases).

Problems with the device itself included reports of:

- Device incompatibility such as an allergy (7,515 cases).

- The device migrating (4,535 cases).

- The device breaking or fracturing (2,297 cases).

- The device dislodging or dislocating (1,797 cases).

- Improper operation including implant failure and pregnancy (1,058 cases).

In 2019, Essure received 15,083 medical device reports, an increase from 6,000 reports in 2018 and 11,854 reports in 2017.

To date, nearly 39,000 women in the United States have made claims to injuries related to the Essure device. In August, Bayer announced it would pay approximately $1.6 billion U.S. dollars to settle 90% of these cases in exchange for claimants to “dismiss their cases or not file.” Bayer also said in a press release that the settlement is not an admission of wrongdoing or liability on the part of the company.

In an interview, Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said the latest adverse event reports show “consistent info from [the] MAUDE database when comparing 2019 to previous years, highlighting most common problems related to pain and heavy or irregular bleeding.”

She emphasized ob.gyns with patients who have an Essure device should “consider Essure-related etiology that may necessitate device removal when evaluating patients with gynecological problems, especially with regard to abdominal/pelvic pain and heavy/irregular bleeding.”

Dr. Cansino reported no relevant financial disclosures. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

HPV vaccine shown to substantially reduce cervical cancer risk

It’s been shown that the vaccine (Gardasil) helps prevent genital warts and high-grade cervical lesions, but until now, data on the ability of the vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, although widely assumed, had been lacking.

“Our results extend [the] knowledge base by showing that quadrivalent HPV vaccination is also associated with a substantially reduced risk of invasive cervical cancer, which is the ultimate intent of HPV vaccination programs,” said investigators led by Jiayao Lei, PhD, a researcher in the department of medical epidemiology and biostatistics at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The study was published online Oct. 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This work provides evidence of actual cancer prevention,” commented Diane Harper, MD, an HPV expert and professor in the departments of family medicine and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She was the principal investigator on the original Gardasil trial.

This study “shows that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine provides prevention from the sexually transmitted HPV infection that actually reduces the incidence of cervical cancer in young women up to 30 years of age,” she said when approached for comment.

However, she also added a note of caution. These new results show “that vaccinated women still develop cervical cancer, but at a slower rate. This makes the connection between early-age vaccination and continued adult life screening incredibly important,” Dr. Harper said in an interview

Cervical cancer was diagnosed in 19 of the 527,871 women (0.004%) who had received at least one dose of the vaccine versus 538 among the 1,145,112 women (0.05%) who had not.

The cumulative incidence was 47 cases per 100,000 vaccinated women and 94 cases per 100,000 unvaccinated women. The cervical cancer incidence rate ratio for the comparison of vaccinated versus unvaccinated women was 0.37 (95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.57).

The risk reduction was even greater among women who had been vaccinated before the age of 17, with a cumulative incidence of 4 versus 54 cases per 100,000 for women vaccinated after age 17. The incidence rate ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.00-0.34) for women who had been vaccinated before age 17 versus 0.47 (95% CI, 0.27-0.75) among those vaccinated from age 17 to 30 years.

Overall, “the risk of cervical cancer among participants who had initiated vaccination before the age of 17 years was 88% lower than among those who had never been vaccinated,” the investigators noted.

These results “support the recommendation to administer quadrivalent HPV vaccine before exposure to HPV infection to achieve the most substantial benefit,” the investigators wrote.

Details of the Swedish review

For their review, Dr. Lei and colleagues used several Swedish demographic and health registries to connect vaccination status to incident cervical cancers, using the personal identification numbers Sweden issues to residents.

Participants were followed starting either on their 10th birthday or on Jan. 1, 2006, whichever came later. They were followed until, among other things, diagnosis of invasive cervical cancer; their 31st birthday; or until Dec. 31, 2017, whichever came first.

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine, approved in Sweden in 2006, was used almost exclusively during the study period. Participants were considered vaccinated if they had received only one shot, but the investigators set out to analyze a relationship between the incidence of invasive cervical cancer and the number of shots given.

Among other things, the team controlled for age at follow-up, calendar year, county of residence, maternal disease history, and parental characteristics, including education and household income.

The investigators commented that it’s possible that HPV-vaccinated women could have been generally healthier than unvaccinated women and so would have been at lower risk for cervical cancer.

“Confounding by lifestyle and health factors in the women (such as smoking status, sexual activity, oral contraceptive use, and obesity) cannot be excluded; these factors are known to be associated with a risk of cervical cancer,” the investigators wrote.

HPV is also associated with other types of cancer, including anal and oropharyngeal cancers. But these cancers develop over a longer period than cervical cancer.

Dr. Harper noted that the “probability of HPV 16 cancer by time since infection peaks at 40 years after infection for anal cancers and nearly 50 years after infection for oropharyngeal cancers. This means that registries, such as in Sweden, for the next 40 years will record the evidence to say whether HPV vaccination lasts long enough to prevent [these] other HPV 16–associated cancers occurring at a much later time in life.”

The work was funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Swedish Research Council and by the China Scholarship Council. Dr. Lei and two other investigators reported HPV vaccine research funding from Merck, the maker of Gardasil. Harper disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s been shown that the vaccine (Gardasil) helps prevent genital warts and high-grade cervical lesions, but until now, data on the ability of the vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, although widely assumed, had been lacking.

“Our results extend [the] knowledge base by showing that quadrivalent HPV vaccination is also associated with a substantially reduced risk of invasive cervical cancer, which is the ultimate intent of HPV vaccination programs,” said investigators led by Jiayao Lei, PhD, a researcher in the department of medical epidemiology and biostatistics at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The study was published online Oct. 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This work provides evidence of actual cancer prevention,” commented Diane Harper, MD, an HPV expert and professor in the departments of family medicine and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She was the principal investigator on the original Gardasil trial.

This study “shows that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine provides prevention from the sexually transmitted HPV infection that actually reduces the incidence of cervical cancer in young women up to 30 years of age,” she said when approached for comment.

However, she also added a note of caution. These new results show “that vaccinated women still develop cervical cancer, but at a slower rate. This makes the connection between early-age vaccination and continued adult life screening incredibly important,” Dr. Harper said in an interview

Cervical cancer was diagnosed in 19 of the 527,871 women (0.004%) who had received at least one dose of the vaccine versus 538 among the 1,145,112 women (0.05%) who had not.

The cumulative incidence was 47 cases per 100,000 vaccinated women and 94 cases per 100,000 unvaccinated women. The cervical cancer incidence rate ratio for the comparison of vaccinated versus unvaccinated women was 0.37 (95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.57).

The risk reduction was even greater among women who had been vaccinated before the age of 17, with a cumulative incidence of 4 versus 54 cases per 100,000 for women vaccinated after age 17. The incidence rate ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.00-0.34) for women who had been vaccinated before age 17 versus 0.47 (95% CI, 0.27-0.75) among those vaccinated from age 17 to 30 years.

Overall, “the risk of cervical cancer among participants who had initiated vaccination before the age of 17 years was 88% lower than among those who had never been vaccinated,” the investigators noted.

These results “support the recommendation to administer quadrivalent HPV vaccine before exposure to HPV infection to achieve the most substantial benefit,” the investigators wrote.

Details of the Swedish review

For their review, Dr. Lei and colleagues used several Swedish demographic and health registries to connect vaccination status to incident cervical cancers, using the personal identification numbers Sweden issues to residents.

Participants were followed starting either on their 10th birthday or on Jan. 1, 2006, whichever came later. They were followed until, among other things, diagnosis of invasive cervical cancer; their 31st birthday; or until Dec. 31, 2017, whichever came first.

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine, approved in Sweden in 2006, was used almost exclusively during the study period. Participants were considered vaccinated if they had received only one shot, but the investigators set out to analyze a relationship between the incidence of invasive cervical cancer and the number of shots given.

Among other things, the team controlled for age at follow-up, calendar year, county of residence, maternal disease history, and parental characteristics, including education and household income.

The investigators commented that it’s possible that HPV-vaccinated women could have been generally healthier than unvaccinated women and so would have been at lower risk for cervical cancer.

“Confounding by lifestyle and health factors in the women (such as smoking status, sexual activity, oral contraceptive use, and obesity) cannot be excluded; these factors are known to be associated with a risk of cervical cancer,” the investigators wrote.

HPV is also associated with other types of cancer, including anal and oropharyngeal cancers. But these cancers develop over a longer period than cervical cancer.

Dr. Harper noted that the “probability of HPV 16 cancer by time since infection peaks at 40 years after infection for anal cancers and nearly 50 years after infection for oropharyngeal cancers. This means that registries, such as in Sweden, for the next 40 years will record the evidence to say whether HPV vaccination lasts long enough to prevent [these] other HPV 16–associated cancers occurring at a much later time in life.”

The work was funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Swedish Research Council and by the China Scholarship Council. Dr. Lei and two other investigators reported HPV vaccine research funding from Merck, the maker of Gardasil. Harper disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s been shown that the vaccine (Gardasil) helps prevent genital warts and high-grade cervical lesions, but until now, data on the ability of the vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, although widely assumed, had been lacking.

“Our results extend [the] knowledge base by showing that quadrivalent HPV vaccination is also associated with a substantially reduced risk of invasive cervical cancer, which is the ultimate intent of HPV vaccination programs,” said investigators led by Jiayao Lei, PhD, a researcher in the department of medical epidemiology and biostatistics at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The study was published online Oct. 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This work provides evidence of actual cancer prevention,” commented Diane Harper, MD, an HPV expert and professor in the departments of family medicine and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She was the principal investigator on the original Gardasil trial.

This study “shows that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine provides prevention from the sexually transmitted HPV infection that actually reduces the incidence of cervical cancer in young women up to 30 years of age,” she said when approached for comment.

However, she also added a note of caution. These new results show “that vaccinated women still develop cervical cancer, but at a slower rate. This makes the connection between early-age vaccination and continued adult life screening incredibly important,” Dr. Harper said in an interview

Cervical cancer was diagnosed in 19 of the 527,871 women (0.004%) who had received at least one dose of the vaccine versus 538 among the 1,145,112 women (0.05%) who had not.

The cumulative incidence was 47 cases per 100,000 vaccinated women and 94 cases per 100,000 unvaccinated women. The cervical cancer incidence rate ratio for the comparison of vaccinated versus unvaccinated women was 0.37 (95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.57).

The risk reduction was even greater among women who had been vaccinated before the age of 17, with a cumulative incidence of 4 versus 54 cases per 100,000 for women vaccinated after age 17. The incidence rate ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.00-0.34) for women who had been vaccinated before age 17 versus 0.47 (95% CI, 0.27-0.75) among those vaccinated from age 17 to 30 years.

Overall, “the risk of cervical cancer among participants who had initiated vaccination before the age of 17 years was 88% lower than among those who had never been vaccinated,” the investigators noted.

These results “support the recommendation to administer quadrivalent HPV vaccine before exposure to HPV infection to achieve the most substantial benefit,” the investigators wrote.

Details of the Swedish review

For their review, Dr. Lei and colleagues used several Swedish demographic and health registries to connect vaccination status to incident cervical cancers, using the personal identification numbers Sweden issues to residents.

Participants were followed starting either on their 10th birthday or on Jan. 1, 2006, whichever came later. They were followed until, among other things, diagnosis of invasive cervical cancer; their 31st birthday; or until Dec. 31, 2017, whichever came first.

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine, approved in Sweden in 2006, was used almost exclusively during the study period. Participants were considered vaccinated if they had received only one shot, but the investigators set out to analyze a relationship between the incidence of invasive cervical cancer and the number of shots given.

Among other things, the team controlled for age at follow-up, calendar year, county of residence, maternal disease history, and parental characteristics, including education and household income.

The investigators commented that it’s possible that HPV-vaccinated women could have been generally healthier than unvaccinated women and so would have been at lower risk for cervical cancer.

“Confounding by lifestyle and health factors in the women (such as smoking status, sexual activity, oral contraceptive use, and obesity) cannot be excluded; these factors are known to be associated with a risk of cervical cancer,” the investigators wrote.

HPV is also associated with other types of cancer, including anal and oropharyngeal cancers. But these cancers develop over a longer period than cervical cancer.

Dr. Harper noted that the “probability of HPV 16 cancer by time since infection peaks at 40 years after infection for anal cancers and nearly 50 years after infection for oropharyngeal cancers. This means that registries, such as in Sweden, for the next 40 years will record the evidence to say whether HPV vaccination lasts long enough to prevent [these] other HPV 16–associated cancers occurring at a much later time in life.”

The work was funded by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Swedish Research Council and by the China Scholarship Council. Dr. Lei and two other investigators reported HPV vaccine research funding from Merck, the maker of Gardasil. Harper disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

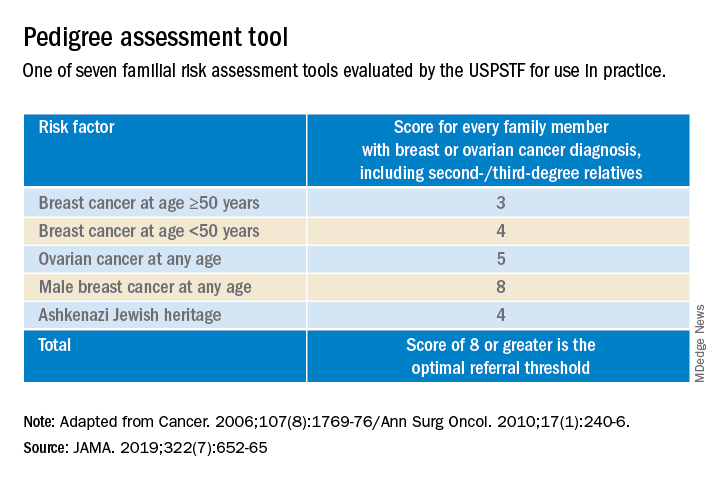

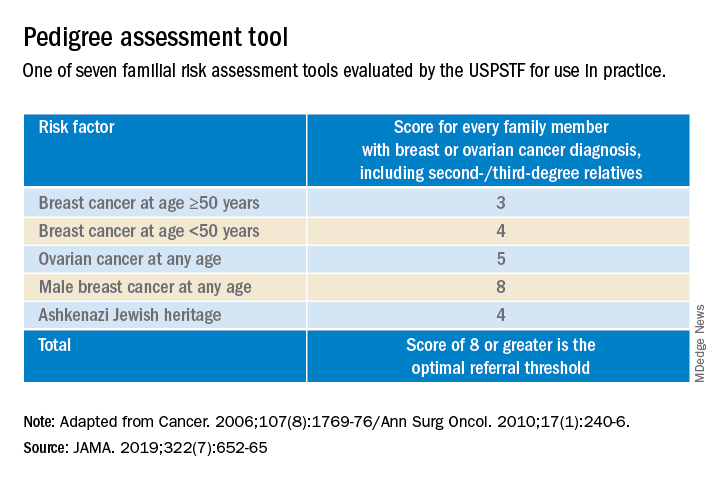

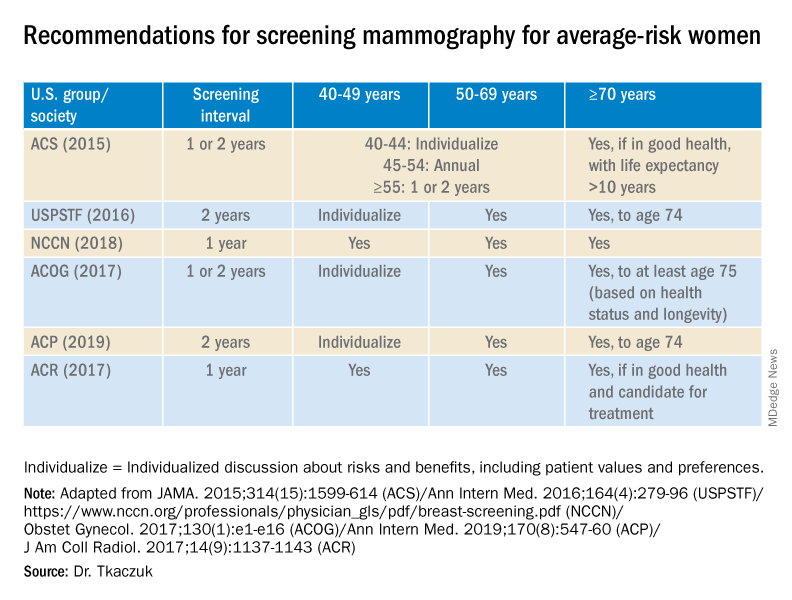

Breast cancer screening complexities

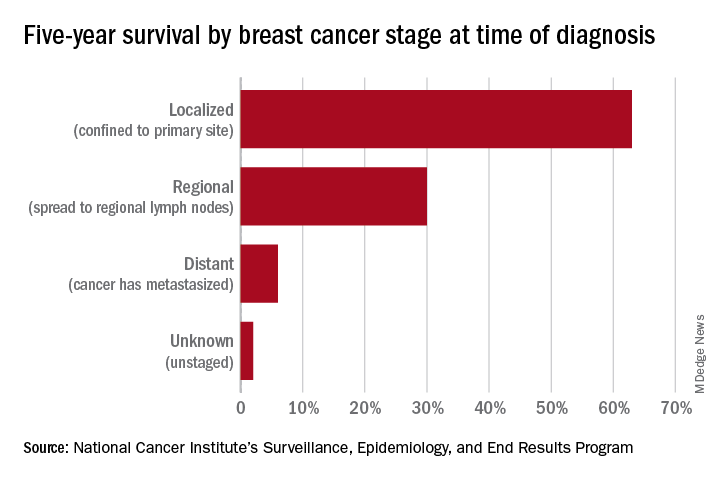

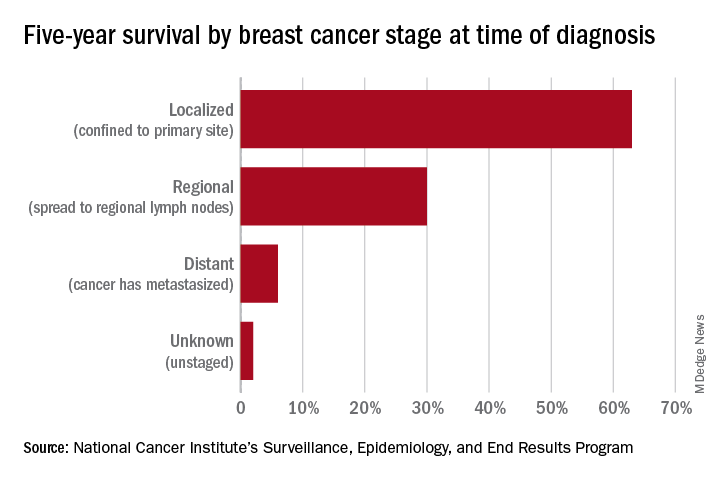

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

Breast cancer in women remains one of the most common types of cancer in the United States, affecting about one in eight women1 over the course of their lifetime. Despite its pervasiveness, the 5-year survival rate for women with breast cancer remains high, estimated at around 90%2 based on data from 2010-2016, in large part because of early detection and treatment through screening. However, many organizations disagree on when to start and how often to screen women at average risk.

Important to discussions about breast cancer screening is the trend that many women delay childbirth until their 30s and 40s. In 2018 the birth rate increased for women ages 35-44, and the mean age of first birth increased from the prior year across all racial and ethnic groups.3 Therefore, ob.gyns. may need to consider that their patients not only may have increased risk of developing breast cancer based on age alone – women aged 35-44 have four times greater risk of disease than women aged 20-342 – but that the pregnancy itself may further exacerbate risk in older women. A 2019 pooled analysis found that women who were older at first birth had a greater chance of developing breast cancer compared with women with no children.4

In addition, ob.gyns. should consider that their patients may have received a breast cancer diagnosis prior to initiation or completion of their family plans or that their patients are cancer survivors – in 2013-2017, breast cancer was the most common form of cancer in adolescents and young adults.5 Thus, practitioners should be prepared to discuss not only options for fertility preservation but the evidence regarding cancer recurrence after pregnancy.

We have invited Dr. Katherine Tkaczuk, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine* and director of the breast evaluation and treatment program at the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center, to discuss the vital role of screening in the shared decision-making process of breast cancer prevention.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore,* as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

Correction, 1/8/21: *An earlier version of this article misstated the university affiliations for Dr. Tkaczuk and Dr. Reece.

References

1. U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics. breastcancer.org.

2. “Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer,” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

3. Martin JA et al. “Births: Final Data for 2018.” National Vital Statistics Reports. 2019 Nov 27;68(13):1-46.

4. Nichols HB et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jan;170(1):22-30.

5. “Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Among Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) (Ages 15-39),” Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute.

An oncologist’s view on screening mammography

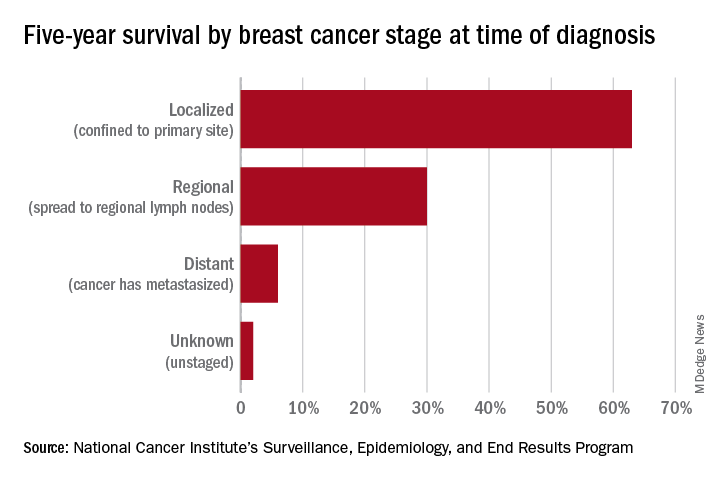

Screening mammography has contributed to the lowering of mortality from breast cancer by facilitating earlier diagnosis and a lower stage at diagnosis. With more effective treatment options for women who are diagnosed with lower-stage breast cancer, the current 5-year survival rate has risen to 90% – significantly higher than the 5-year survival rate of 75% in 1975.1

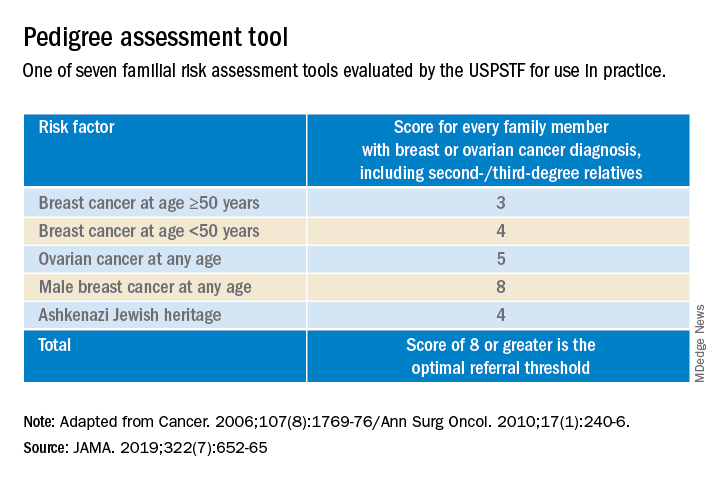

Women who are at much higher risk for developing breast cancer – mainly because of family history, certain genetic mutations, or a history of radiation therapy to the chest – will benefit the most from earlier and more frequent screening mammography as well as enhanced screening with non-x-ray methods of breast imaging. It is important that ob.gyns. help to identify these women.

However, the majority of women who are screened with mammography are at “average risk,” with a lifetime risk for developing breast cancer of 12.9%, based on 2015-2017 data from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER).1 The median age at diagnosis of breast cancer in the U.S. is 62 years,1 and advancing age is the most important risk factor for these women.

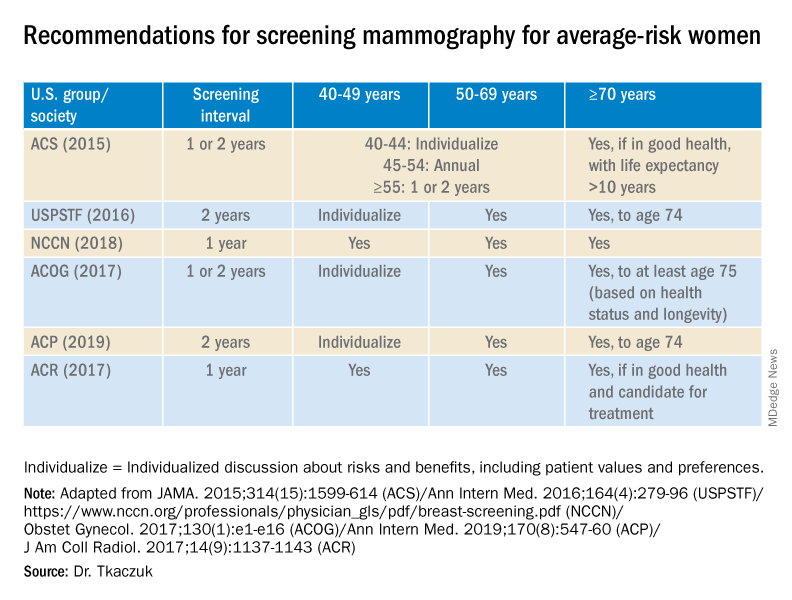

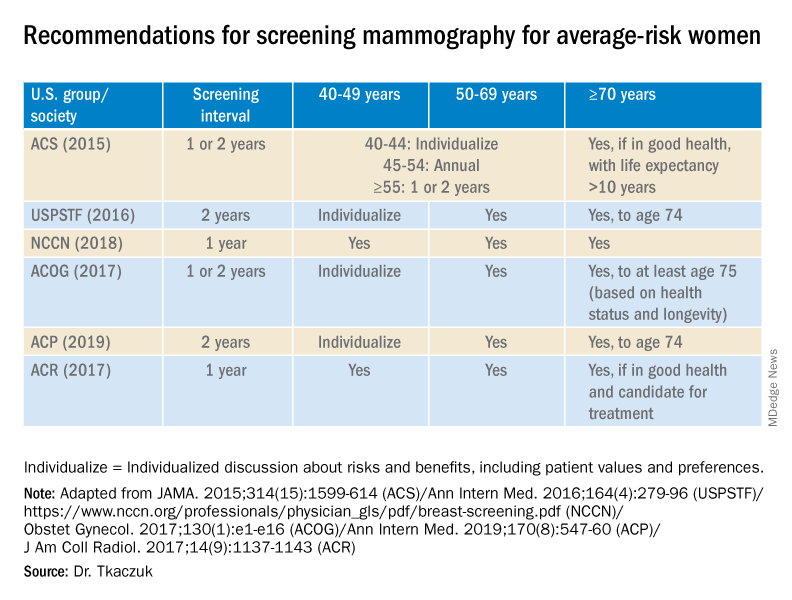

A 20% relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality with screening mammography has been demonstrated both in systematic reviews of randomized and observational studies2 and in a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials comparing screening and no screening.3 Even though the majority of randomized trials were done in the age of film mammography, experts believe that we still see at least a 20% reduction today.

Among average-risk women, those aged 50-74 with a life expectancy of at least 10 years will benefit the most from regular screening. According to the 2016 screening guideline of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), relative risk reductions in breast cancer mortality from mammography screening, by age group, are 0.88 (confidence interval, 0.73-1.003) for ages 39-49; 0.86 (CI, 0.68-0.97) for ages 50-59; 0.67 (CI, 0.55-0.91) for ages 60-69; and 0.80 (CI, 0.51 to 1.28) for ages 70-74.2

For women aged 40-49 years, most of the guidelines in the United States recommend individualized screening every 1 or 2 years – screening that is guided by shared decision-making that takes into account each woman’s values regarding relative harms and benefits. This is because their risk of developing breast cancer is relatively low while the risk of false-positive results can be higher.