User login

EREFS value has diagnostic utility for eosinophilic esophagitis

The Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, or EREFS, is not only highly predictive of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) but also its responsiveness to treatment, which suggests it may be used as an outcome measure, researchers say.

A prospective study of 211 adults undergoing upper endoscopy to investigate symptoms of esophageal dysfunction compared the EREFS with consensus guidelines for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis.

The guidelines approach identified 67 cases of eosinophilic esophagitis and 144 control subjects without eosinophilic esophagitis. When these patients were assessed via the EREFS, researchers found multiple, highly significant differences between the cases and controls, with a mean total EREFS of 3.88 for cases and 0.42 for controls, according to a paper published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“On ROC [receiver operator characteristic] analysis, a model that contained all 5 components of the EREFS system as categorical variables had an AUC [area under the curve] of 0.946, indicating an excellent ability to predict EoE case status based on endoscopic findings alone,” wrote Dr. Evan S. Dellon and colleagues of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In this model, a score of 2.0 or above showed a sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 92%, positive predictive value of 84%, negative predictive value of 94%, and accuracy of 91%.

Most of the score’s predictive ability was attributed to its inflammatory component, and less from the fibrostenotic score, which the authors suggested was due to the high prevalence of strictures in the control group.

The EREFS also improved significantly after treatment, in conjunction with endoscopic findings.

Total EREFS significantly decreased from 3.88 to 2.01, the inflammatory score decreased from 2.41 to 1.22, and the fibrostenotic score decreased from 1.46 to 0.89.

Histologic responders to treatment showed much more significant decreases in EREFS compared with nonresponders (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015, Sept. 12 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040]).

Researchers also examined the impact of weighing the various features of EREFS differently.

“The iterative analysis investigating weighing the EREFS features differently showed that increasing the weight of the exudate, rings, and edema score modestly increased the predictive power when the change in eosinophil counts was treated continuously and that increasing the weight of exudates and rings was beneficial with a threshold eosinophil count (less than 15 eosinophil/hpf) for response,” they reported.

Based on this finding, the researchers created a set of EREFS scores using these varied weights, and showed that doubling the exudates, rings, and edema scores achieved the score’s maximum responsiveness while still keeping the weighting system simple, although these changes did not alter the score’s overall predictive ability.

The EREFS score was developed as a way to standardize the description, recognition, and reporting of eosinophilic esophagitis, but its diagnostic utility and responsiveness to treatment were unknown, the authors said.

“This prospective study found that the EREFS classification has diagnostic utility for EoE,” they wrote. “Moreover, the score is responsive to treatment, decreasing significantly in histologic responders, and can be used as an outcome measure.”

The National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease funded the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, or EREFS, is not only highly predictive of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) but also its responsiveness to treatment, which suggests it may be used as an outcome measure, researchers say.

A prospective study of 211 adults undergoing upper endoscopy to investigate symptoms of esophageal dysfunction compared the EREFS with consensus guidelines for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis.

The guidelines approach identified 67 cases of eosinophilic esophagitis and 144 control subjects without eosinophilic esophagitis. When these patients were assessed via the EREFS, researchers found multiple, highly significant differences between the cases and controls, with a mean total EREFS of 3.88 for cases and 0.42 for controls, according to a paper published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“On ROC [receiver operator characteristic] analysis, a model that contained all 5 components of the EREFS system as categorical variables had an AUC [area under the curve] of 0.946, indicating an excellent ability to predict EoE case status based on endoscopic findings alone,” wrote Dr. Evan S. Dellon and colleagues of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In this model, a score of 2.0 or above showed a sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 92%, positive predictive value of 84%, negative predictive value of 94%, and accuracy of 91%.

Most of the score’s predictive ability was attributed to its inflammatory component, and less from the fibrostenotic score, which the authors suggested was due to the high prevalence of strictures in the control group.

The EREFS also improved significantly after treatment, in conjunction with endoscopic findings.

Total EREFS significantly decreased from 3.88 to 2.01, the inflammatory score decreased from 2.41 to 1.22, and the fibrostenotic score decreased from 1.46 to 0.89.

Histologic responders to treatment showed much more significant decreases in EREFS compared with nonresponders (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015, Sept. 12 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040]).

Researchers also examined the impact of weighing the various features of EREFS differently.

“The iterative analysis investigating weighing the EREFS features differently showed that increasing the weight of the exudate, rings, and edema score modestly increased the predictive power when the change in eosinophil counts was treated continuously and that increasing the weight of exudates and rings was beneficial with a threshold eosinophil count (less than 15 eosinophil/hpf) for response,” they reported.

Based on this finding, the researchers created a set of EREFS scores using these varied weights, and showed that doubling the exudates, rings, and edema scores achieved the score’s maximum responsiveness while still keeping the weighting system simple, although these changes did not alter the score’s overall predictive ability.

The EREFS score was developed as a way to standardize the description, recognition, and reporting of eosinophilic esophagitis, but its diagnostic utility and responsiveness to treatment were unknown, the authors said.

“This prospective study found that the EREFS classification has diagnostic utility for EoE,” they wrote. “Moreover, the score is responsive to treatment, decreasing significantly in histologic responders, and can be used as an outcome measure.”

The National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease funded the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score, or EREFS, is not only highly predictive of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) but also its responsiveness to treatment, which suggests it may be used as an outcome measure, researchers say.

A prospective study of 211 adults undergoing upper endoscopy to investigate symptoms of esophageal dysfunction compared the EREFS with consensus guidelines for diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis.

The guidelines approach identified 67 cases of eosinophilic esophagitis and 144 control subjects without eosinophilic esophagitis. When these patients were assessed via the EREFS, researchers found multiple, highly significant differences between the cases and controls, with a mean total EREFS of 3.88 for cases and 0.42 for controls, according to a paper published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“On ROC [receiver operator characteristic] analysis, a model that contained all 5 components of the EREFS system as categorical variables had an AUC [area under the curve] of 0.946, indicating an excellent ability to predict EoE case status based on endoscopic findings alone,” wrote Dr. Evan S. Dellon and colleagues of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In this model, a score of 2.0 or above showed a sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 92%, positive predictive value of 84%, negative predictive value of 94%, and accuracy of 91%.

Most of the score’s predictive ability was attributed to its inflammatory component, and less from the fibrostenotic score, which the authors suggested was due to the high prevalence of strictures in the control group.

The EREFS also improved significantly after treatment, in conjunction with endoscopic findings.

Total EREFS significantly decreased from 3.88 to 2.01, the inflammatory score decreased from 2.41 to 1.22, and the fibrostenotic score decreased from 1.46 to 0.89.

Histologic responders to treatment showed much more significant decreases in EREFS compared with nonresponders (Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2015, Sept. 12 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040]).

Researchers also examined the impact of weighing the various features of EREFS differently.

“The iterative analysis investigating weighing the EREFS features differently showed that increasing the weight of the exudate, rings, and edema score modestly increased the predictive power when the change in eosinophil counts was treated continuously and that increasing the weight of exudates and rings was beneficial with a threshold eosinophil count (less than 15 eosinophil/hpf) for response,” they reported.

Based on this finding, the researchers created a set of EREFS scores using these varied weights, and showed that doubling the exudates, rings, and edema scores achieved the score’s maximum responsiveness while still keeping the weighting system simple, although these changes did not alter the score’s overall predictive ability.

The EREFS score was developed as a way to standardize the description, recognition, and reporting of eosinophilic esophagitis, but its diagnostic utility and responsiveness to treatment were unknown, the authors said.

“This prospective study found that the EREFS classification has diagnostic utility for EoE,” they wrote. “Moreover, the score is responsive to treatment, decreasing significantly in histologic responders, and can be used as an outcome measure.”

The National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease funded the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score is highly predictive of eosinophilic esophagitis and responsiveness to treatment.

Major finding: A model containing all five components of the EREFS system as categorical variables had an AUC of 0.946.

Data source: A prospective study of 211 adults undergoing upper endoscopy to investigate esophageal dysfunction.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease funded the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

High serum leptin, insulin levels linked to Barrett’s esophagus risk

High serum insulin and leptin levels were significantly associated with Barrett’s esophagus, according to authors of a meta-analysis of nine observational studies published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels, and were 1.74 times as likely to have hyperinsulinemia, said Dr. Apoorva Chandar of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland) and his associates.

Central obesity was known to increase the risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.009]), but this meta-analysis helped pinpoint the hormones that might mediate the relationship, the investigators said. However, the link between obesity and Barrett’s esophagus “is likely complex,” meriting additional longitudinal analyses, they added.

Metabolically active fat produces leptin and other adipokines. Elevated serum leptin has anti-apoptotic and angiogenic effects and also is a marker for insulin resistance, the researchers noted. “Several observational studies have examined the association of serum adipokines and insulin with Barrett’s esophagus, but evidence regarding this association remains inconclusive,” they said. Therefore, they reviewed observational studies published through April 2015 that examined relationships between Barrett’s esophagus, adipokines, and insulin. The studies included 10 separate cohorts of 1,432 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and 3,550 controls, enabling the researchers to estimate summary adjusted odds ratios (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.041]).

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels (adjusted OR, 2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-3.78) and 1.74 times as likely to have elevated serum insulin levels (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.65). Total serum adiponectin was not linked to risk of Barrett’s esophagus, but increased serum levels of high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin were (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.16-2.63), and one study reported an inverse correlation between levels of low molecular weight leptin and Barrett’s esophagus risk. Low molecular weight adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects, while HMW adiponectin is proinflammatory, the researchers noted.

“It is simplistic to assume that the effects of obesity on the development of Barrett’s esophagus are mediated by one single adipokine,” the researchers said. “Leptin and adiponectin seem to crosstalk, and both of these adipokines also affect insulin-signaling pathways.” Obesity is a chronic inflammatory state characterized by increases in other circulating cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha, they noted. Their findings do not solely implicate leptin among the adipokines, but show that it “might be an important contributor, and support further studies on the effects of leptin on the leptin receptor in the proliferation of Barrett’s epithelium.” They also noted that although women have higher leptin levels than men, men are at much greater risk of Barrett’s esophagus, which their review could not explain. Studies to date are “not adequate” to assess gender-specific relationships between insulin, adipokines, and Barrett’s esophagus, they said.

Other evidence has linked insulin to Barrett’s esophagus, according to the researchers. Insulin and related signaling pathways are upregulated in tissue specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s esophagus is more likely to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma in the setting of insulin resistance, they noted. “Given that recent studies have shown an association between Barrett’s esophagus and measures of central obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2, it is conceivable that hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, which are known consequences of central obesity, are associated with Barrett’s esophagus pathogenesis,” they said.

However, their study did not link hyperinsulinemia to Barrett’s esophagus among subjects with GERD, possibly because of confounding or overmatching, they noted. More rigorous studies would be needed to fairly evaluate any relationship between insulin resistance and risk of Barrett’s esophagus, they concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that abdominal, especially visceral as opposed to cutaneous, obesity isassociated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus. The precise mechanisms are unclear; however, there is increasing evidence that this association is likely mediated through both the mechanical effect of increased abdominal pressure promoting gastroesophageal reflux and the nonmechanical metabolic and inflammatory effects of abdominal obesity. Adipose tissue produces and releases a variety of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, including the adipokines leptin and adiponectin, as well as cytokines and chemokines. Leptin (higher levels in visceral fat) has proinflammatory effects that promote a low-grade inflammatory state, while adiponectin (less visceral fat) protects against the complications of obesity by exerting anti-inflammatory effects.

|

| Dr. Aaron Thrift |

Results from single-center studies examining associations of circulating adipokines, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines with Barrett’s esophagus have been conflicting, potentially due to methodologic shortcomings. In this article, Dr. Chandar and his colleagues conducted a meta-analysis and report that higher serum levels of leptin and insulin are associated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus, while there was no association between serum adiponectin and Barrett’s esophagus. This study highlights the complexity of these associations. For example, only leptin among the adipokines was associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Thus, additional longitudinal studies are required to further tease out these associations, and formal mediation analysis would help quantify how much of the obesity effect is through these hormones. From a clinical perspective, the importance of the findings of this paper is that these may be attractive targets for preventing Barrett’s esophagus.

Dr. Thrift is in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts of interest.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that abdominal, especially visceral as opposed to cutaneous, obesity isassociated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus. The precise mechanisms are unclear; however, there is increasing evidence that this association is likely mediated through both the mechanical effect of increased abdominal pressure promoting gastroesophageal reflux and the nonmechanical metabolic and inflammatory effects of abdominal obesity. Adipose tissue produces and releases a variety of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, including the adipokines leptin and adiponectin, as well as cytokines and chemokines. Leptin (higher levels in visceral fat) has proinflammatory effects that promote a low-grade inflammatory state, while adiponectin (less visceral fat) protects against the complications of obesity by exerting anti-inflammatory effects.

|

| Dr. Aaron Thrift |

Results from single-center studies examining associations of circulating adipokines, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines with Barrett’s esophagus have been conflicting, potentially due to methodologic shortcomings. In this article, Dr. Chandar and his colleagues conducted a meta-analysis and report that higher serum levels of leptin and insulin are associated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus, while there was no association between serum adiponectin and Barrett’s esophagus. This study highlights the complexity of these associations. For example, only leptin among the adipokines was associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Thus, additional longitudinal studies are required to further tease out these associations, and formal mediation analysis would help quantify how much of the obesity effect is through these hormones. From a clinical perspective, the importance of the findings of this paper is that these may be attractive targets for preventing Barrett’s esophagus.

Dr. Thrift is in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts of interest.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that abdominal, especially visceral as opposed to cutaneous, obesity isassociated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus. The precise mechanisms are unclear; however, there is increasing evidence that this association is likely mediated through both the mechanical effect of increased abdominal pressure promoting gastroesophageal reflux and the nonmechanical metabolic and inflammatory effects of abdominal obesity. Adipose tissue produces and releases a variety of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, including the adipokines leptin and adiponectin, as well as cytokines and chemokines. Leptin (higher levels in visceral fat) has proinflammatory effects that promote a low-grade inflammatory state, while adiponectin (less visceral fat) protects against the complications of obesity by exerting anti-inflammatory effects.

|

| Dr. Aaron Thrift |

Results from single-center studies examining associations of circulating adipokines, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines with Barrett’s esophagus have been conflicting, potentially due to methodologic shortcomings. In this article, Dr. Chandar and his colleagues conducted a meta-analysis and report that higher serum levels of leptin and insulin are associated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus, while there was no association between serum adiponectin and Barrett’s esophagus. This study highlights the complexity of these associations. For example, only leptin among the adipokines was associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Thus, additional longitudinal studies are required to further tease out these associations, and formal mediation analysis would help quantify how much of the obesity effect is through these hormones. From a clinical perspective, the importance of the findings of this paper is that these may be attractive targets for preventing Barrett’s esophagus.

Dr. Thrift is in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He has no conflicts of interest.

High serum insulin and leptin levels were significantly associated with Barrett’s esophagus, according to authors of a meta-analysis of nine observational studies published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels, and were 1.74 times as likely to have hyperinsulinemia, said Dr. Apoorva Chandar of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland) and his associates.

Central obesity was known to increase the risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.009]), but this meta-analysis helped pinpoint the hormones that might mediate the relationship, the investigators said. However, the link between obesity and Barrett’s esophagus “is likely complex,” meriting additional longitudinal analyses, they added.

Metabolically active fat produces leptin and other adipokines. Elevated serum leptin has anti-apoptotic and angiogenic effects and also is a marker for insulin resistance, the researchers noted. “Several observational studies have examined the association of serum adipokines and insulin with Barrett’s esophagus, but evidence regarding this association remains inconclusive,” they said. Therefore, they reviewed observational studies published through April 2015 that examined relationships between Barrett’s esophagus, adipokines, and insulin. The studies included 10 separate cohorts of 1,432 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and 3,550 controls, enabling the researchers to estimate summary adjusted odds ratios (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.041]).

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels (adjusted OR, 2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-3.78) and 1.74 times as likely to have elevated serum insulin levels (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.65). Total serum adiponectin was not linked to risk of Barrett’s esophagus, but increased serum levels of high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin were (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.16-2.63), and one study reported an inverse correlation between levels of low molecular weight leptin and Barrett’s esophagus risk. Low molecular weight adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects, while HMW adiponectin is proinflammatory, the researchers noted.

“It is simplistic to assume that the effects of obesity on the development of Barrett’s esophagus are mediated by one single adipokine,” the researchers said. “Leptin and adiponectin seem to crosstalk, and both of these adipokines also affect insulin-signaling pathways.” Obesity is a chronic inflammatory state characterized by increases in other circulating cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha, they noted. Their findings do not solely implicate leptin among the adipokines, but show that it “might be an important contributor, and support further studies on the effects of leptin on the leptin receptor in the proliferation of Barrett’s epithelium.” They also noted that although women have higher leptin levels than men, men are at much greater risk of Barrett’s esophagus, which their review could not explain. Studies to date are “not adequate” to assess gender-specific relationships between insulin, adipokines, and Barrett’s esophagus, they said.

Other evidence has linked insulin to Barrett’s esophagus, according to the researchers. Insulin and related signaling pathways are upregulated in tissue specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s esophagus is more likely to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma in the setting of insulin resistance, they noted. “Given that recent studies have shown an association between Barrett’s esophagus and measures of central obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2, it is conceivable that hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, which are known consequences of central obesity, are associated with Barrett’s esophagus pathogenesis,” they said.

However, their study did not link hyperinsulinemia to Barrett’s esophagus among subjects with GERD, possibly because of confounding or overmatching, they noted. More rigorous studies would be needed to fairly evaluate any relationship between insulin resistance and risk of Barrett’s esophagus, they concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

High serum insulin and leptin levels were significantly associated with Barrett’s esophagus, according to authors of a meta-analysis of nine observational studies published in the December issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels, and were 1.74 times as likely to have hyperinsulinemia, said Dr. Apoorva Chandar of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland) and his associates.

Central obesity was known to increase the risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.009]), but this meta-analysis helped pinpoint the hormones that might mediate the relationship, the investigators said. However, the link between obesity and Barrett’s esophagus “is likely complex,” meriting additional longitudinal analyses, they added.

Metabolically active fat produces leptin and other adipokines. Elevated serum leptin has anti-apoptotic and angiogenic effects and also is a marker for insulin resistance, the researchers noted. “Several observational studies have examined the association of serum adipokines and insulin with Barrett’s esophagus, but evidence regarding this association remains inconclusive,” they said. Therefore, they reviewed observational studies published through April 2015 that examined relationships between Barrett’s esophagus, adipokines, and insulin. The studies included 10 separate cohorts of 1,432 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and 3,550 controls, enabling the researchers to estimate summary adjusted odds ratios (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.041]).

Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels (adjusted OR, 2.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-3.78) and 1.74 times as likely to have elevated serum insulin levels (95% CI, 1.14 to 2.65). Total serum adiponectin was not linked to risk of Barrett’s esophagus, but increased serum levels of high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin were (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.16-2.63), and one study reported an inverse correlation between levels of low molecular weight leptin and Barrett’s esophagus risk. Low molecular weight adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects, while HMW adiponectin is proinflammatory, the researchers noted.

“It is simplistic to assume that the effects of obesity on the development of Barrett’s esophagus are mediated by one single adipokine,” the researchers said. “Leptin and adiponectin seem to crosstalk, and both of these adipokines also affect insulin-signaling pathways.” Obesity is a chronic inflammatory state characterized by increases in other circulating cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor–alpha, they noted. Their findings do not solely implicate leptin among the adipokines, but show that it “might be an important contributor, and support further studies on the effects of leptin on the leptin receptor in the proliferation of Barrett’s epithelium.” They also noted that although women have higher leptin levels than men, men are at much greater risk of Barrett’s esophagus, which their review could not explain. Studies to date are “not adequate” to assess gender-specific relationships between insulin, adipokines, and Barrett’s esophagus, they said.

Other evidence has linked insulin to Barrett’s esophagus, according to the researchers. Insulin and related signaling pathways are upregulated in tissue specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s esophagus is more likely to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma in the setting of insulin resistance, they noted. “Given that recent studies have shown an association between Barrett’s esophagus and measures of central obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2, it is conceivable that hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, which are known consequences of central obesity, are associated with Barrett’s esophagus pathogenesis,” they said.

However, their study did not link hyperinsulinemia to Barrett’s esophagus among subjects with GERD, possibly because of confounding or overmatching, they noted. More rigorous studies would be needed to fairly evaluate any relationship between insulin resistance and risk of Barrett’s esophagus, they concluded.

The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: High serum levels of leptin and insulin were associated with Barrett’s esophagus in a meta-analysis.

Major finding: Compared with population controls, patients with Barrett’s esophagus were twice as likely to have high serum leptin levels, and were 1.74 times as likely to have hyperinsulinemia.

Data source: Meta-analysis of nine observational studies that included 1,432 Barrett’s esophagus patients and 3,550 controls.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute funded the study. The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Early TIPS tied to mortality reduction in esophageal bleeds

HONOLULU – Early use of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is associated with substantial reductions in mortality, according to an analysis of a national inpatient database.

Based on this study, “early use of TIPS, together with patient and physician education on current guidelines and protocols, should continue to be a priority to improve patient outcomes” in patients with hepatic cirrhosis and risk of recurrent esophageal variceal bleeds, reported Dr. Basile Njei, a gastroenterology fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In this study, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database was queried by ICD-9 codes to identify patients with esophageal variceal bleeding treated between the years 2000 and 2010. The goal was to compare early use of TIPS, defined as TIPS administered within 72 hours of the bleeding, relative to rescue TIPS, defined as TIPS after two or more episodes of bleeding or one bleeding episode followed by another endoscopic intervention, such as balloon tamponade or surgery.

Over the period of study, a Poisson regression analysis used to control for multiple variables associated any TIPS utilization with an inverse association with overall mortality, producing a relative risk of 0.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.92). In the context of timing of TIPS, in-hospital mortality fell from 5.6% for those who received rescue TIPS to 1.5% in those who underwent early TIPS.

On multivariate analysis, an advantage was observed for early TIPS relative to rescue TIPS for in-hospital mortality (RR, 0.85; P less than .01), in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), and length of hospital stay (RR, 0.87; P less than .01). Rates of sepsis (RR, 0.83; P = .32) and hepatic encephalopathy (RR, 0.87; P = .22) were not significantly lower in the early TIPS group, but they were also not increased. For early TIPS versus no TIPS, the advantages on multivariate analysis were similar for both in-hospital deaths (RR, 0.87; P less than .01) and in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), but no advantage was seen for length of stay for TIPS versus no TIPS (RR, 0.99; P = .18).

Overall, there was a steady decline in mortality associated with esophageal variceal bleeding over the period of evaluation, falling incrementally over time from 656 deaths per 100,000 hospitalizations in 2000 to 412 deaths per 100,000 in 2010. This 37.2% reduction was statistically significant (P less than .01). The reduction in mortality was inversely associated with an increasing use of TIPS over the study period.

The data from this analysis are consistent with a multicenter randomized trial conducted several years ago in Europe (N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-9). In that study 63 patients with hepatic cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding who had been treated with vasoactive drugs plus endoscopic therapy were randomized to early TIPS or rescue TIPS. At 1 year, 86% of those in the early TIPS group were alive versus 61% (P = .01) of those randomized to receive TIPS as a rescue strategy.

Relative to the previous study, the key finding of this study is that early TIPS “is associated with significant short-term reductions in rebleeding and mortality without a significant increase in encephalopathy in real world U.S. clinical practice,” according to Dr. Njei. It substantiates the European study and encourages a protocol that emphasizes early TIPS, particularly in those with a high risk of repeat esophageal variceal bleeding.

In the discussion that followed the presentation of these results at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, the moderator, Dr. Paul Y. Kwo, medical director of liver transplantation, Indiana University, Indianapolis, pointed out, that some of those in the rescue TIPS group might simply have been poor candidates for this intervention. Although he praised the methodology of this study, which won the 2015 ACG Fellows-In-Training Award, he questioned whether rescue TIPS was a last resort salvage therapy in those initially considered poor risks for TIPS. Dr. Njei responded that the multivariate analysis was specifically designed to control for variables such as risk status to diminish this potential bias. Indeed, he said he believes TIPS is underemployed.

“The relatively small percentage of eligible cases receiving early TIPS suggests that there is room for further improvement in the treatment of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and esophageal variceal bleeding,” Dr. Njei concluded.

Dr. Njei reported that he had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

HONOLULU – Early use of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is associated with substantial reductions in mortality, according to an analysis of a national inpatient database.

Based on this study, “early use of TIPS, together with patient and physician education on current guidelines and protocols, should continue to be a priority to improve patient outcomes” in patients with hepatic cirrhosis and risk of recurrent esophageal variceal bleeds, reported Dr. Basile Njei, a gastroenterology fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In this study, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database was queried by ICD-9 codes to identify patients with esophageal variceal bleeding treated between the years 2000 and 2010. The goal was to compare early use of TIPS, defined as TIPS administered within 72 hours of the bleeding, relative to rescue TIPS, defined as TIPS after two or more episodes of bleeding or one bleeding episode followed by another endoscopic intervention, such as balloon tamponade or surgery.

Over the period of study, a Poisson regression analysis used to control for multiple variables associated any TIPS utilization with an inverse association with overall mortality, producing a relative risk of 0.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.92). In the context of timing of TIPS, in-hospital mortality fell from 5.6% for those who received rescue TIPS to 1.5% in those who underwent early TIPS.

On multivariate analysis, an advantage was observed for early TIPS relative to rescue TIPS for in-hospital mortality (RR, 0.85; P less than .01), in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), and length of hospital stay (RR, 0.87; P less than .01). Rates of sepsis (RR, 0.83; P = .32) and hepatic encephalopathy (RR, 0.87; P = .22) were not significantly lower in the early TIPS group, but they were also not increased. For early TIPS versus no TIPS, the advantages on multivariate analysis were similar for both in-hospital deaths (RR, 0.87; P less than .01) and in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), but no advantage was seen for length of stay for TIPS versus no TIPS (RR, 0.99; P = .18).

Overall, there was a steady decline in mortality associated with esophageal variceal bleeding over the period of evaluation, falling incrementally over time from 656 deaths per 100,000 hospitalizations in 2000 to 412 deaths per 100,000 in 2010. This 37.2% reduction was statistically significant (P less than .01). The reduction in mortality was inversely associated with an increasing use of TIPS over the study period.

The data from this analysis are consistent with a multicenter randomized trial conducted several years ago in Europe (N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-9). In that study 63 patients with hepatic cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding who had been treated with vasoactive drugs plus endoscopic therapy were randomized to early TIPS or rescue TIPS. At 1 year, 86% of those in the early TIPS group were alive versus 61% (P = .01) of those randomized to receive TIPS as a rescue strategy.

Relative to the previous study, the key finding of this study is that early TIPS “is associated with significant short-term reductions in rebleeding and mortality without a significant increase in encephalopathy in real world U.S. clinical practice,” according to Dr. Njei. It substantiates the European study and encourages a protocol that emphasizes early TIPS, particularly in those with a high risk of repeat esophageal variceal bleeding.

In the discussion that followed the presentation of these results at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, the moderator, Dr. Paul Y. Kwo, medical director of liver transplantation, Indiana University, Indianapolis, pointed out, that some of those in the rescue TIPS group might simply have been poor candidates for this intervention. Although he praised the methodology of this study, which won the 2015 ACG Fellows-In-Training Award, he questioned whether rescue TIPS was a last resort salvage therapy in those initially considered poor risks for TIPS. Dr. Njei responded that the multivariate analysis was specifically designed to control for variables such as risk status to diminish this potential bias. Indeed, he said he believes TIPS is underemployed.

“The relatively small percentage of eligible cases receiving early TIPS suggests that there is room for further improvement in the treatment of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and esophageal variceal bleeding,” Dr. Njei concluded.

Dr. Njei reported that he had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

HONOLULU – Early use of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is associated with substantial reductions in mortality, according to an analysis of a national inpatient database.

Based on this study, “early use of TIPS, together with patient and physician education on current guidelines and protocols, should continue to be a priority to improve patient outcomes” in patients with hepatic cirrhosis and risk of recurrent esophageal variceal bleeds, reported Dr. Basile Njei, a gastroenterology fellow at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In this study, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database was queried by ICD-9 codes to identify patients with esophageal variceal bleeding treated between the years 2000 and 2010. The goal was to compare early use of TIPS, defined as TIPS administered within 72 hours of the bleeding, relative to rescue TIPS, defined as TIPS after two or more episodes of bleeding or one bleeding episode followed by another endoscopic intervention, such as balloon tamponade or surgery.

Over the period of study, a Poisson regression analysis used to control for multiple variables associated any TIPS utilization with an inverse association with overall mortality, producing a relative risk of 0.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.92). In the context of timing of TIPS, in-hospital mortality fell from 5.6% for those who received rescue TIPS to 1.5% in those who underwent early TIPS.

On multivariate analysis, an advantage was observed for early TIPS relative to rescue TIPS for in-hospital mortality (RR, 0.85; P less than .01), in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), and length of hospital stay (RR, 0.87; P less than .01). Rates of sepsis (RR, 0.83; P = .32) and hepatic encephalopathy (RR, 0.87; P = .22) were not significantly lower in the early TIPS group, but they were also not increased. For early TIPS versus no TIPS, the advantages on multivariate analysis were similar for both in-hospital deaths (RR, 0.87; P less than .01) and in-hospital rebleeding (RR, 0.57; P less than .01), but no advantage was seen for length of stay for TIPS versus no TIPS (RR, 0.99; P = .18).

Overall, there was a steady decline in mortality associated with esophageal variceal bleeding over the period of evaluation, falling incrementally over time from 656 deaths per 100,000 hospitalizations in 2000 to 412 deaths per 100,000 in 2010. This 37.2% reduction was statistically significant (P less than .01). The reduction in mortality was inversely associated with an increasing use of TIPS over the study period.

The data from this analysis are consistent with a multicenter randomized trial conducted several years ago in Europe (N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-9). In that study 63 patients with hepatic cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding who had been treated with vasoactive drugs plus endoscopic therapy were randomized to early TIPS or rescue TIPS. At 1 year, 86% of those in the early TIPS group were alive versus 61% (P = .01) of those randomized to receive TIPS as a rescue strategy.

Relative to the previous study, the key finding of this study is that early TIPS “is associated with significant short-term reductions in rebleeding and mortality without a significant increase in encephalopathy in real world U.S. clinical practice,” according to Dr. Njei. It substantiates the European study and encourages a protocol that emphasizes early TIPS, particularly in those with a high risk of repeat esophageal variceal bleeding.

In the discussion that followed the presentation of these results at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, the moderator, Dr. Paul Y. Kwo, medical director of liver transplantation, Indiana University, Indianapolis, pointed out, that some of those in the rescue TIPS group might simply have been poor candidates for this intervention. Although he praised the methodology of this study, which won the 2015 ACG Fellows-In-Training Award, he questioned whether rescue TIPS was a last resort salvage therapy in those initially considered poor risks for TIPS. Dr. Njei responded that the multivariate analysis was specifically designed to control for variables such as risk status to diminish this potential bias. Indeed, he said he believes TIPS is underemployed.

“The relatively small percentage of eligible cases receiving early TIPS suggests that there is room for further improvement in the treatment of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and esophageal variceal bleeding,” Dr. Njei concluded.

Dr. Njei reported that he had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

AT ACG 2015

Key clinical point:Early use of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to reduce the risk of esophageal variceal rebleeding is associated with reduced mortality.

Major finding: In those receiving early TIPS (TIPS administered within 72 hours of the bleeding) mortality was 1.5% vs. 5.6% for those receiving TIPS as rescue therapy.

Data source: A retrospective evaluation of a national inpatient database.

Disclosures: Dr. Njei reported that he had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Disparity found in PPI risk perception among physicians

HONOLULU – A survey of almost 500 physicians found that primary care physicians (PCPs) are far more concerned about the reported adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) than are gastroenterologists and use them more sparingly. The results of the survey were presented at the 2015 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Annual Scientific Meeting and Postgraduate Course.

“We asked physicians about a broad array of adverse effects from long-term use of PPIs and PCPs expressed greater concern for all of them,” reported Dr. Samir Kapadia, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Alternatively, significantly more gastroenterologists responded that they really had no concerns for any of these adverse effects.”

The evidence may be on the side of the gastroenterologists, according to Dr. Kapadia. Although PPIs have been associated with hypomagnesemia, iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile infection, and interactions with the platelet inhibitor clopidogrel, Dr. Kapadia noted that few associations have been made on the basis of prospective trials.

“Much of the available literature is observational or based on studies that are heterogeneous and small,” Dr. Kapadia. “Confounding factors in these studies also limit interpretation.”

In this study for which surveys are still being collected, a 19-item questionnaire was distributed to 384 gastroenterologists and 88 PCPs. In addition to demographic information, the surveys were designed to capture opinions about the safety of PPIs as well as elicit information about how these agents are being used in clinical practice.

Of side effects associated with PPIs, significantly more PCPs than gastroenterologists expressed concern about hypomagnesemia (41.7% vs. 6.3%; P less than .001), iron deficiency (33.3% vs. 11.4%; P = .014) and vitamin B12 deficiency (47.6% vs. 17.3%; P = .005). From the other perspective, when asked about their concern for these and other safety issues, the answer was “none of the above” for 26.2% of PCPs and 67.1% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001).

When given specific risk scenarios, PCPs were consistently more prepared to discontinue PPI therapy than were gastroenterologists. For example, in a hypothetical 65-year-old with GERD symptoms expressing concern about risk of hip fracture, 64.5% of PCPs vs. 30.7% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001) responded that they would discontinue the PPI. In a patient of the same age about to start broad-spectrum antibiotics for cellulitis, 16.1% of PCPs, but only 4.3% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) reported that they would discontinue PPIs. Conversely, 68.5% of gastroenterologists vs. 54.2% of PCPs (P = .028) would continue therapy.

For a hypothetical 65-year-old with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) initiating clopidogrel, 50% of PCPs vs. 27.6% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would switch to an H2-receptor antagonist. Only 27.3% of PCPs vs. 46.4% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would continue the PPI. When the age of the hypothetical patient is raised to 75 years, PCPs, but not gastroenterologists, were even more likely to discontinue PPI therapy.

Using PPIs appropriately is an important goal, Dr. Kapadia emphasized. However, he suggested that many warnings about the risks of PPIs, including those issued by the Food and Drug Administration, are incompletely substantiated and are not being evaluated with an appropriate attention to benefit-to-risk ratio of a drug that not only controls symptoms but may also reduce risk of GI bleeding. Others share this point of view.

“The pendulum has moved too far in regard to the fear of potential side effects,” agreed Dr. Philip Katz, chairman, division of gastroenterology, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. First author of the 2013 ACG guidelines on GERD, which addresses the safety of PPIs (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-28), Dr. Katz said in an interview that the data generated by this survey suggest that PCPs are misinterpreting the relative risks and need to be given more information about indications in which benefits are well established.

Making the same point, Dr. Nicholas J. Shaheen, chief, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, suggested “This may be a failure on our part [as gastroenterologists] to educate our colleagues about the role of these drugs.”

Dr. Kapadia reported no potential conflicts.

HONOLULU – A survey of almost 500 physicians found that primary care physicians (PCPs) are far more concerned about the reported adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) than are gastroenterologists and use them more sparingly. The results of the survey were presented at the 2015 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Annual Scientific Meeting and Postgraduate Course.

“We asked physicians about a broad array of adverse effects from long-term use of PPIs and PCPs expressed greater concern for all of them,” reported Dr. Samir Kapadia, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Alternatively, significantly more gastroenterologists responded that they really had no concerns for any of these adverse effects.”

The evidence may be on the side of the gastroenterologists, according to Dr. Kapadia. Although PPIs have been associated with hypomagnesemia, iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile infection, and interactions with the platelet inhibitor clopidogrel, Dr. Kapadia noted that few associations have been made on the basis of prospective trials.

“Much of the available literature is observational or based on studies that are heterogeneous and small,” Dr. Kapadia. “Confounding factors in these studies also limit interpretation.”

In this study for which surveys are still being collected, a 19-item questionnaire was distributed to 384 gastroenterologists and 88 PCPs. In addition to demographic information, the surveys were designed to capture opinions about the safety of PPIs as well as elicit information about how these agents are being used in clinical practice.

Of side effects associated with PPIs, significantly more PCPs than gastroenterologists expressed concern about hypomagnesemia (41.7% vs. 6.3%; P less than .001), iron deficiency (33.3% vs. 11.4%; P = .014) and vitamin B12 deficiency (47.6% vs. 17.3%; P = .005). From the other perspective, when asked about their concern for these and other safety issues, the answer was “none of the above” for 26.2% of PCPs and 67.1% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001).

When given specific risk scenarios, PCPs were consistently more prepared to discontinue PPI therapy than were gastroenterologists. For example, in a hypothetical 65-year-old with GERD symptoms expressing concern about risk of hip fracture, 64.5% of PCPs vs. 30.7% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001) responded that they would discontinue the PPI. In a patient of the same age about to start broad-spectrum antibiotics for cellulitis, 16.1% of PCPs, but only 4.3% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) reported that they would discontinue PPIs. Conversely, 68.5% of gastroenterologists vs. 54.2% of PCPs (P = .028) would continue therapy.

For a hypothetical 65-year-old with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) initiating clopidogrel, 50% of PCPs vs. 27.6% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would switch to an H2-receptor antagonist. Only 27.3% of PCPs vs. 46.4% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would continue the PPI. When the age of the hypothetical patient is raised to 75 years, PCPs, but not gastroenterologists, were even more likely to discontinue PPI therapy.

Using PPIs appropriately is an important goal, Dr. Kapadia emphasized. However, he suggested that many warnings about the risks of PPIs, including those issued by the Food and Drug Administration, are incompletely substantiated and are not being evaluated with an appropriate attention to benefit-to-risk ratio of a drug that not only controls symptoms but may also reduce risk of GI bleeding. Others share this point of view.

“The pendulum has moved too far in regard to the fear of potential side effects,” agreed Dr. Philip Katz, chairman, division of gastroenterology, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. First author of the 2013 ACG guidelines on GERD, which addresses the safety of PPIs (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-28), Dr. Katz said in an interview that the data generated by this survey suggest that PCPs are misinterpreting the relative risks and need to be given more information about indications in which benefits are well established.

Making the same point, Dr. Nicholas J. Shaheen, chief, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, suggested “This may be a failure on our part [as gastroenterologists] to educate our colleagues about the role of these drugs.”

Dr. Kapadia reported no potential conflicts.

HONOLULU – A survey of almost 500 physicians found that primary care physicians (PCPs) are far more concerned about the reported adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) than are gastroenterologists and use them more sparingly. The results of the survey were presented at the 2015 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Annual Scientific Meeting and Postgraduate Course.

“We asked physicians about a broad array of adverse effects from long-term use of PPIs and PCPs expressed greater concern for all of them,” reported Dr. Samir Kapadia, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Alternatively, significantly more gastroenterologists responded that they really had no concerns for any of these adverse effects.”

The evidence may be on the side of the gastroenterologists, according to Dr. Kapadia. Although PPIs have been associated with hypomagnesemia, iron deficiency, vitamin B12 deficiency, diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile infection, and interactions with the platelet inhibitor clopidogrel, Dr. Kapadia noted that few associations have been made on the basis of prospective trials.

“Much of the available literature is observational or based on studies that are heterogeneous and small,” Dr. Kapadia. “Confounding factors in these studies also limit interpretation.”

In this study for which surveys are still being collected, a 19-item questionnaire was distributed to 384 gastroenterologists and 88 PCPs. In addition to demographic information, the surveys were designed to capture opinions about the safety of PPIs as well as elicit information about how these agents are being used in clinical practice.

Of side effects associated with PPIs, significantly more PCPs than gastroenterologists expressed concern about hypomagnesemia (41.7% vs. 6.3%; P less than .001), iron deficiency (33.3% vs. 11.4%; P = .014) and vitamin B12 deficiency (47.6% vs. 17.3%; P = .005). From the other perspective, when asked about their concern for these and other safety issues, the answer was “none of the above” for 26.2% of PCPs and 67.1% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001).

When given specific risk scenarios, PCPs were consistently more prepared to discontinue PPI therapy than were gastroenterologists. For example, in a hypothetical 65-year-old with GERD symptoms expressing concern about risk of hip fracture, 64.5% of PCPs vs. 30.7% of gastroenterologists (P less than .001) responded that they would discontinue the PPI. In a patient of the same age about to start broad-spectrum antibiotics for cellulitis, 16.1% of PCPs, but only 4.3% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) reported that they would discontinue PPIs. Conversely, 68.5% of gastroenterologists vs. 54.2% of PCPs (P = .028) would continue therapy.

For a hypothetical 65-year-old with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) initiating clopidogrel, 50% of PCPs vs. 27.6% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would switch to an H2-receptor antagonist. Only 27.3% of PCPs vs. 46.4% of gastroenterologists (P = .001) would continue the PPI. When the age of the hypothetical patient is raised to 75 years, PCPs, but not gastroenterologists, were even more likely to discontinue PPI therapy.

Using PPIs appropriately is an important goal, Dr. Kapadia emphasized. However, he suggested that many warnings about the risks of PPIs, including those issued by the Food and Drug Administration, are incompletely substantiated and are not being evaluated with an appropriate attention to benefit-to-risk ratio of a drug that not only controls symptoms but may also reduce risk of GI bleeding. Others share this point of view.

“The pendulum has moved too far in regard to the fear of potential side effects,” agreed Dr. Philip Katz, chairman, division of gastroenterology, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia. First author of the 2013 ACG guidelines on GERD, which addresses the safety of PPIs (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-28), Dr. Katz said in an interview that the data generated by this survey suggest that PCPs are misinterpreting the relative risks and need to be given more information about indications in which benefits are well established.

Making the same point, Dr. Nicholas J. Shaheen, chief, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, suggested “This may be a failure on our part [as gastroenterologists] to educate our colleagues about the role of these drugs.”

Dr. Kapadia reported no potential conflicts.

FROM THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY 2015 SCIENTIFIC MEETING AND POSTGRADUATE COURSE

Key clinical point: Primary care physicians used proton pump inhibitors more sparingly, were more concerned about reported adverse effects than were gastroenterologists, but are perhaps too cautious in the cost-benefit analysis.

Major finding: Primary care physicians (PCPs) are far more concerned about the reported adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors than are gastroenterologists.

Data source: A survey of nearly 500 physicians, weighted toward gastroenterologists.

Disclosures: Dr. Kapadia reported no potential conflicts of interest.

GI bleeds in obese patients more complicated but no more fatal

HONOLULU – Obese patients who develop an upper GI bleed receive more treatment, are more likely to develop hemorrhagic shock, and are more likely to require admission to an intensive care unit than those who are not obese, but they do not have higher in-hospital mortality, according to analysis of a large national database that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The significantly greater odds ratio of most major complications from upper GI bleeds in patients with obesity relative to those who are not obese was expected but so was an increased rate of in-hospital mortality, according to the first author of the study, Dr. Marwan S. Abou Gergi of Catalyst Medical Consulting, Baltimore.

“In this study, patients with obesity received more frequent endoscopic interventions, which could explain why mortality rates were not significantly higher,” Dr. Abou Gergi reported.

In the analysis, characterized as the first study to evaluate the impact of obesity on outcomes in upper GI hemorrhage, data were drawn from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which is considered to provide a representative sample of U.S. hospital experience. Drawn from more than 7 million hospitalizations, the study focused on patients 18 or over with a primary ICD-9 code for upper GI hemorrhage. The primary outcome was mortality. Secondary outcomes included interventions, ICU admissions, and length of stay.

Of the 132,545 discharges with upper GI hemorrhage, 11,220 (8.5%) were identified as obese. The in-hospital mortality overall was 1.97%, but the proportion of those who died was slightly lower among patients identified as obese, producing a nonsignificant adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 0.87 (P greater than .1). Yet the rates of hemorrhage shock (OR 1.31; P = .02) and admission to the ICU (OR 1.35; P less than .02) were greater in the obese. The median length of stay of 0.35 days for obese patients was also significantly longer.

One reason for the lower rate of mortality may be more aggressive treatment. In particular, repeat endoscopy therapy was more common in those who were obese (P less than .01), suggesting, “Our treatments are working,” Dr. Abou Gergi said.

The proportion of patients with a score of 3 or greater on the Charlson comorbidity index was higher in the obese than in those not identified as obese (49% vs. 39%; P less than .01). This along with previously published evidence that obese patients take more anticoagulants, take more antiplatelets, and may face delays in endoscopy due to greater difficulty in administering sedation, were among considerations predicting a higher mortality, according to Dr. Abou Gergi.

However, there are several potential explanations for these unexpected findings. One is that mortality rates overall were low, making it difficult to show differences on this outcome. In addition, ICD-9 codes may be effective for isolating a group with obesity but not in identifying a control group without obesity.

“It is likely that not all patients who are obese received this code, so we may be seeing a population of obese patients be compared to another population that includes at least some patients who also have obesity,” explained Dr. John R. Saltzman, director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. A coauthor of this study, Dr. Saltzman noted that despite a comparable rate of in-hospital mortality, most of the findings in the study argued that patients who develop upper GI bleeding have a more difficult course. He noted that this is reflected in the cost of care, which was significantly higher in those who were obese.

Although he acknowledged that he was surprised that this was “essentially a negative study,” he believes that mortality may have been “too tough” as a primary endpoint for demonstrating a difference. However, he also believes that it may be appropriate to give credit for effective treatments.

“I think that may be the key. We are just getting better at taking care of these patients,” Dr. Saltzman said.

Dr. Abou Gergi reported he has no relevant financial relationships.

HONOLULU – Obese patients who develop an upper GI bleed receive more treatment, are more likely to develop hemorrhagic shock, and are more likely to require admission to an intensive care unit than those who are not obese, but they do not have higher in-hospital mortality, according to analysis of a large national database that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The significantly greater odds ratio of most major complications from upper GI bleeds in patients with obesity relative to those who are not obese was expected but so was an increased rate of in-hospital mortality, according to the first author of the study, Dr. Marwan S. Abou Gergi of Catalyst Medical Consulting, Baltimore.

“In this study, patients with obesity received more frequent endoscopic interventions, which could explain why mortality rates were not significantly higher,” Dr. Abou Gergi reported.

In the analysis, characterized as the first study to evaluate the impact of obesity on outcomes in upper GI hemorrhage, data were drawn from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which is considered to provide a representative sample of U.S. hospital experience. Drawn from more than 7 million hospitalizations, the study focused on patients 18 or over with a primary ICD-9 code for upper GI hemorrhage. The primary outcome was mortality. Secondary outcomes included interventions, ICU admissions, and length of stay.

Of the 132,545 discharges with upper GI hemorrhage, 11,220 (8.5%) were identified as obese. The in-hospital mortality overall was 1.97%, but the proportion of those who died was slightly lower among patients identified as obese, producing a nonsignificant adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 0.87 (P greater than .1). Yet the rates of hemorrhage shock (OR 1.31; P = .02) and admission to the ICU (OR 1.35; P less than .02) were greater in the obese. The median length of stay of 0.35 days for obese patients was also significantly longer.

One reason for the lower rate of mortality may be more aggressive treatment. In particular, repeat endoscopy therapy was more common in those who were obese (P less than .01), suggesting, “Our treatments are working,” Dr. Abou Gergi said.

The proportion of patients with a score of 3 or greater on the Charlson comorbidity index was higher in the obese than in those not identified as obese (49% vs. 39%; P less than .01). This along with previously published evidence that obese patients take more anticoagulants, take more antiplatelets, and may face delays in endoscopy due to greater difficulty in administering sedation, were among considerations predicting a higher mortality, according to Dr. Abou Gergi.

However, there are several potential explanations for these unexpected findings. One is that mortality rates overall were low, making it difficult to show differences on this outcome. In addition, ICD-9 codes may be effective for isolating a group with obesity but not in identifying a control group without obesity.

“It is likely that not all patients who are obese received this code, so we may be seeing a population of obese patients be compared to another population that includes at least some patients who also have obesity,” explained Dr. John R. Saltzman, director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. A coauthor of this study, Dr. Saltzman noted that despite a comparable rate of in-hospital mortality, most of the findings in the study argued that patients who develop upper GI bleeding have a more difficult course. He noted that this is reflected in the cost of care, which was significantly higher in those who were obese.

Although he acknowledged that he was surprised that this was “essentially a negative study,” he believes that mortality may have been “too tough” as a primary endpoint for demonstrating a difference. However, he also believes that it may be appropriate to give credit for effective treatments.

“I think that may be the key. We are just getting better at taking care of these patients,” Dr. Saltzman said.

Dr. Abou Gergi reported he has no relevant financial relationships.

HONOLULU – Obese patients who develop an upper GI bleed receive more treatment, are more likely to develop hemorrhagic shock, and are more likely to require admission to an intensive care unit than those who are not obese, but they do not have higher in-hospital mortality, according to analysis of a large national database that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The significantly greater odds ratio of most major complications from upper GI bleeds in patients with obesity relative to those who are not obese was expected but so was an increased rate of in-hospital mortality, according to the first author of the study, Dr. Marwan S. Abou Gergi of Catalyst Medical Consulting, Baltimore.

“In this study, patients with obesity received more frequent endoscopic interventions, which could explain why mortality rates were not significantly higher,” Dr. Abou Gergi reported.

In the analysis, characterized as the first study to evaluate the impact of obesity on outcomes in upper GI hemorrhage, data were drawn from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which is considered to provide a representative sample of U.S. hospital experience. Drawn from more than 7 million hospitalizations, the study focused on patients 18 or over with a primary ICD-9 code for upper GI hemorrhage. The primary outcome was mortality. Secondary outcomes included interventions, ICU admissions, and length of stay.

Of the 132,545 discharges with upper GI hemorrhage, 11,220 (8.5%) were identified as obese. The in-hospital mortality overall was 1.97%, but the proportion of those who died was slightly lower among patients identified as obese, producing a nonsignificant adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 0.87 (P greater than .1). Yet the rates of hemorrhage shock (OR 1.31; P = .02) and admission to the ICU (OR 1.35; P less than .02) were greater in the obese. The median length of stay of 0.35 days for obese patients was also significantly longer.

One reason for the lower rate of mortality may be more aggressive treatment. In particular, repeat endoscopy therapy was more common in those who were obese (P less than .01), suggesting, “Our treatments are working,” Dr. Abou Gergi said.

The proportion of patients with a score of 3 or greater on the Charlson comorbidity index was higher in the obese than in those not identified as obese (49% vs. 39%; P less than .01). This along with previously published evidence that obese patients take more anticoagulants, take more antiplatelets, and may face delays in endoscopy due to greater difficulty in administering sedation, were among considerations predicting a higher mortality, according to Dr. Abou Gergi.

However, there are several potential explanations for these unexpected findings. One is that mortality rates overall were low, making it difficult to show differences on this outcome. In addition, ICD-9 codes may be effective for isolating a group with obesity but not in identifying a control group without obesity.

“It is likely that not all patients who are obese received this code, so we may be seeing a population of obese patients be compared to another population that includes at least some patients who also have obesity,” explained Dr. John R. Saltzman, director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. A coauthor of this study, Dr. Saltzman noted that despite a comparable rate of in-hospital mortality, most of the findings in the study argued that patients who develop upper GI bleeding have a more difficult course. He noted that this is reflected in the cost of care, which was significantly higher in those who were obese.

Although he acknowledged that he was surprised that this was “essentially a negative study,” he believes that mortality may have been “too tough” as a primary endpoint for demonstrating a difference. However, he also believes that it may be appropriate to give credit for effective treatments.

“I think that may be the key. We are just getting better at taking care of these patients,” Dr. Saltzman said.

Dr. Abou Gergi reported he has no relevant financial relationships.

AT ACG 2015

Upper GI tract

This year’s session on esophagus/upper GI at the AGA Spring Postgraduate Course was packed with pragmatic, useful information for the evaluation of patients with upper GI disorders. The session began with a talk on the manifestations of extraesophageal reflux disease. The take-home message of this talk was that putative extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease rarely respond to high-dose therapy with PPIs (proton-pump inhibitors), in the absence of concurrent esophageal symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation. In such situations, investigation of other etiologies of patients’ symptoms, including occult postnasal drainage or cough-variant asthma, may be more rewarding than escalating anti-acid therapy.

Dr. John E. Pandolfino, AGAF, of Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed the utilization of high-resolution manometry in the evaluation of dysphagia. A central focus of this discussion was the use of the Chicago classification of motility abnormalities in assessing these patients. In the future, it is likely that the care of these patients will be dictated by the type of abnormality the patient has in this classification scheme. Especially in the setting of achalasia, data are emerging that some subtypes of achalasia are less likely to respond to some therapies. For instance, type 3 achalasia is unlikely to respond to pneumatic balloon dilatation.

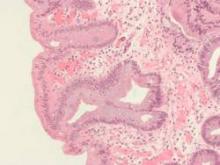

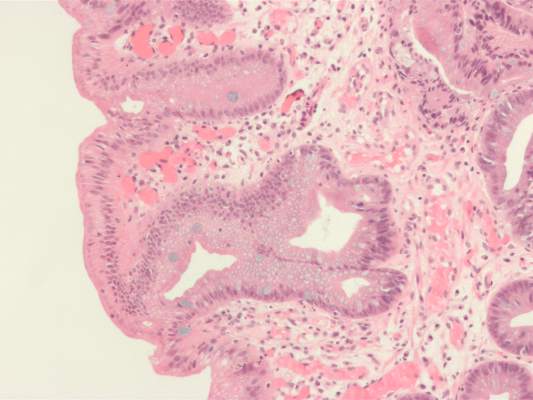

Dr. Rhonda Souza of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, taught us that a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires an 8-week trial of PPI therapy with no resolution of the eosinophilia. Esophageal dilation is generally safe in the setting of a dominant stricture, but it can be delayed prior to medical therapy if the patient is tolerating oral intake well. Although the most commonly used therapies for EoE now involve either swallowed steroids or dietary elimination therapy, several new agents are on the horizon that may give us new treatment options.

Finally, Dr. Amitabh Chak of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, reviewed the care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. This is an especially difficult group of patients to care for, due in part to the low reproducibility in the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, as well as the highly variable reported cancer outcomes in this patient population. Level 1 evidence now exists demonstrating that treatment with radiofrequency ablation decreases the incidence of cancer in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but most patients with this finding will not progress. Therefore, the field would benefit from better risk stratification of these patients.

Dr. Shaheen is professor of medicine and epidemiology and chief of the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.

This year’s session on esophagus/upper GI at the AGA Spring Postgraduate Course was packed with pragmatic, useful information for the evaluation of patients with upper GI disorders. The session began with a talk on the manifestations of extraesophageal reflux disease. The take-home message of this talk was that putative extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease rarely respond to high-dose therapy with PPIs (proton-pump inhibitors), in the absence of concurrent esophageal symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation. In such situations, investigation of other etiologies of patients’ symptoms, including occult postnasal drainage or cough-variant asthma, may be more rewarding than escalating anti-acid therapy.

Dr. John E. Pandolfino, AGAF, of Northwestern University, Chicago, discussed the utilization of high-resolution manometry in the evaluation of dysphagia. A central focus of this discussion was the use of the Chicago classification of motility abnormalities in assessing these patients. In the future, it is likely that the care of these patients will be dictated by the type of abnormality the patient has in this classification scheme. Especially in the setting of achalasia, data are emerging that some subtypes of achalasia are less likely to respond to some therapies. For instance, type 3 achalasia is unlikely to respond to pneumatic balloon dilatation.

Dr. Rhonda Souza of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, taught us that a diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires an 8-week trial of PPI therapy with no resolution of the eosinophilia. Esophageal dilation is generally safe in the setting of a dominant stricture, but it can be delayed prior to medical therapy if the patient is tolerating oral intake well. Although the most commonly used therapies for EoE now involve either swallowed steroids or dietary elimination therapy, several new agents are on the horizon that may give us new treatment options.

Finally, Dr. Amitabh Chak of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, reviewed the care of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. This is an especially difficult group of patients to care for, due in part to the low reproducibility in the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia, as well as the highly variable reported cancer outcomes in this patient population. Level 1 evidence now exists demonstrating that treatment with radiofrequency ablation decreases the incidence of cancer in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but most patients with this finding will not progress. Therefore, the field would benefit from better risk stratification of these patients.

Dr. Shaheen is professor of medicine and epidemiology and chief of the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the spring postgraduate course sessions held at DDW 2015.