User login

Review: Opioid prescriptions are the work of many physicians

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

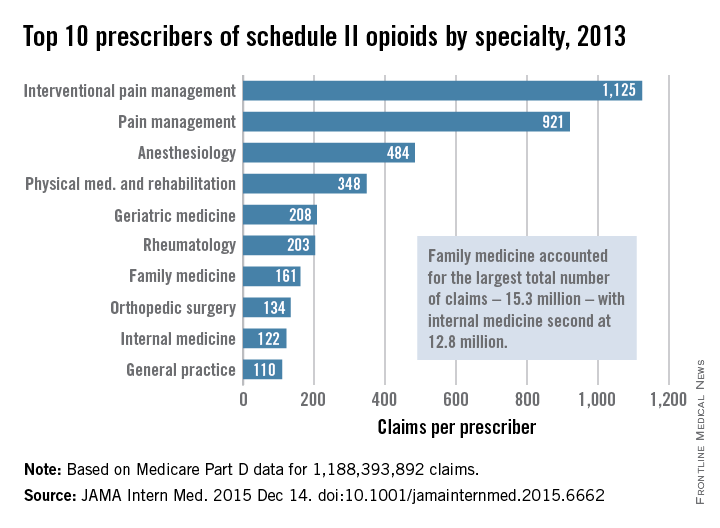

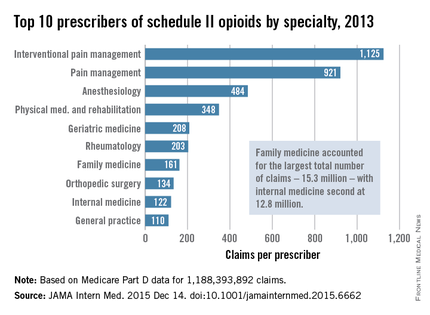

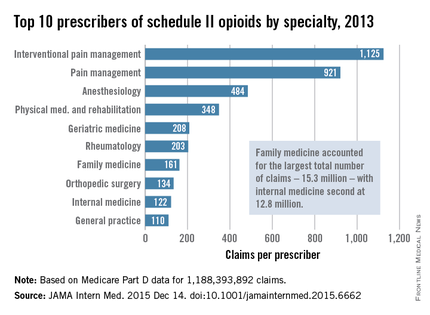

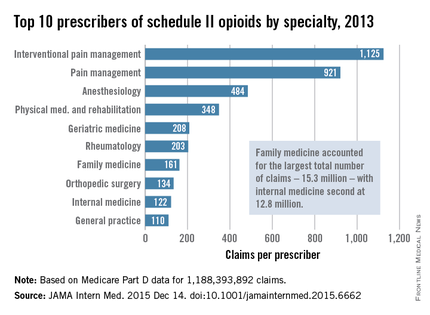

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

A “broad swath” of Medicare providers wrote scripts for opioids in 2013, contradicting the idea that the overdose epidemic is mainly the work of “small groups of prolific prescribers and corrupt pill mills,” investigators wrote online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Contrary to the California workers’ compensation data showing a small subset of prescribers accounting for a disproportionately large percentage of opioid prescribing, Medicare opioid prescribing is distributed across many prescribers and is, if anything, less skewed than all drug prescribing,” said Dr. Jonathan H. Chen of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System, and his associates.

Their study included 808,020 prescribers and almost 1.2 billion Medicare Part D claims worth nearly $81 billion dollars. They focused on schedule II opioid prescriptions containing oxycodone, fentanyl, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, meperidine, codeine, opium, or levorphanol (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Dec 14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662).

Not surprisingly, specialists in pain management, anesthesia, and physical medicine wrote the most prescriptions per provider. But family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined. “The trends hold up across state lines, with negligible geographic variability,” the researchers said.

The findings contradict an analysis of California workers’ compensation data, in which 1% of prescribers accounted for a third of schedule II opioid prescriptions, and 10% of prescribers accounted for 80% of prescriptions, the investigators noted. Nonetheless, 10% of Medicare prescribers in Dr. Chen’s study accounted for 78% of the total cost of opioids, possibly because they were prescribing pricier formulations or higher doses.

Overall, the findings suggest that opioid prescribing is “widespread” and “relatively indifferent to individual physicians, specialty, or region” – and that efforts to stem the tide must be equally broad, the researchers concluded.

Their study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Many different types of general practitioners and specialists often prescribe opioids to Medicare beneficiaries.

Major finding: Family practitioners, internists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants wrote 35,268,234 prescriptions – more than all other specialties combined.

Data source: An analysis of nearly 1.2 billion Medicare part D claims from 2013.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust. The researchers had no disclosures.

FDA approves treatment for chemotherapy ODs, life-threatening toxicities

Uridine triacetate, a pyrimidine analogue, has been approved for the emergency treatment of fluorouracil or capecitabine overdoses in adults and children, and for patients who develop “certain severe or life-threatening toxicities within 4 days of receiving” these treatments, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 11.

“Today’s approval is a first-of-its-kind therapy that can potentially save lives following overdose or life-threatening toxicity from these chemotherapy agents,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the office of hematology and oncology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the FDA statement. It will be marketed as Vistogard by Wellstat Therapeutics.

Uridine comes in an oral granule formulation that can be mixed into soft foods or, when necessary, administered via a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube, the prescribing information states. The indication is for use after an overdose “regardless of the presence of symptoms,” and for treating “early-onset, severe, or life-threatening toxicity affecting the cardiac or central nervous system, and/or early-onset, unusually severe adverse reactions (e.g., gastrointestinal toxicity and/or neutropenia) within 96 hours following the end of fluorouracil or capecitabine administration,” according to the prescribing information.

Uridine blocks cell damage and cell death caused by fluorouracil chemotherapy, according to the statement, which adds that it is up to the patient’s health care provider to “determine when he or she should return to the prescribed chemotherapy after treatment with Vistogard.”

Uridine was evaluated in two studies of 135 adults and children with cancer, treated with uridine for a fluorouracil or capecitabine overdose, or for early-onset, unusually severe or life-threatening toxicities within 96 hours after receiving fluorouracil (not because of an overdose). Among those treated for an overdose, 97% were alive 30 days after treatment, and among those treated for early-onset severe or life-threatening toxicity, 89% were alive 30 days after treatment. In addition, 33% of the patients resumed chemotherapy within 30 days, according to the FDA statement. Diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea were the most common adverse events associated with treatment.

Uridine was granted orphan drug, priority review, and fast track designations.

Uridine triacetate, a pyrimidine analogue, has been approved for the emergency treatment of fluorouracil or capecitabine overdoses in adults and children, and for patients who develop “certain severe or life-threatening toxicities within 4 days of receiving” these treatments, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 11.

“Today’s approval is a first-of-its-kind therapy that can potentially save lives following overdose or life-threatening toxicity from these chemotherapy agents,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the office of hematology and oncology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the FDA statement. It will be marketed as Vistogard by Wellstat Therapeutics.

Uridine comes in an oral granule formulation that can be mixed into soft foods or, when necessary, administered via a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube, the prescribing information states. The indication is for use after an overdose “regardless of the presence of symptoms,” and for treating “early-onset, severe, or life-threatening toxicity affecting the cardiac or central nervous system, and/or early-onset, unusually severe adverse reactions (e.g., gastrointestinal toxicity and/or neutropenia) within 96 hours following the end of fluorouracil or capecitabine administration,” according to the prescribing information.

Uridine blocks cell damage and cell death caused by fluorouracil chemotherapy, according to the statement, which adds that it is up to the patient’s health care provider to “determine when he or she should return to the prescribed chemotherapy after treatment with Vistogard.”

Uridine was evaluated in two studies of 135 adults and children with cancer, treated with uridine for a fluorouracil or capecitabine overdose, or for early-onset, unusually severe or life-threatening toxicities within 96 hours after receiving fluorouracil (not because of an overdose). Among those treated for an overdose, 97% were alive 30 days after treatment, and among those treated for early-onset severe or life-threatening toxicity, 89% were alive 30 days after treatment. In addition, 33% of the patients resumed chemotherapy within 30 days, according to the FDA statement. Diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea were the most common adverse events associated with treatment.

Uridine was granted orphan drug, priority review, and fast track designations.

Uridine triacetate, a pyrimidine analogue, has been approved for the emergency treatment of fluorouracil or capecitabine overdoses in adults and children, and for patients who develop “certain severe or life-threatening toxicities within 4 days of receiving” these treatments, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Dec. 11.

“Today’s approval is a first-of-its-kind therapy that can potentially save lives following overdose or life-threatening toxicity from these chemotherapy agents,” Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the office of hematology and oncology products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the FDA statement. It will be marketed as Vistogard by Wellstat Therapeutics.

Uridine comes in an oral granule formulation that can be mixed into soft foods or, when necessary, administered via a nasogastric or gastrostomy tube, the prescribing information states. The indication is for use after an overdose “regardless of the presence of symptoms,” and for treating “early-onset, severe, or life-threatening toxicity affecting the cardiac or central nervous system, and/or early-onset, unusually severe adverse reactions (e.g., gastrointestinal toxicity and/or neutropenia) within 96 hours following the end of fluorouracil or capecitabine administration,” according to the prescribing information.

Uridine blocks cell damage and cell death caused by fluorouracil chemotherapy, according to the statement, which adds that it is up to the patient’s health care provider to “determine when he or she should return to the prescribed chemotherapy after treatment with Vistogard.”

Uridine was evaluated in two studies of 135 adults and children with cancer, treated with uridine for a fluorouracil or capecitabine overdose, or for early-onset, unusually severe or life-threatening toxicities within 96 hours after receiving fluorouracil (not because of an overdose). Among those treated for an overdose, 97% were alive 30 days after treatment, and among those treated for early-onset severe or life-threatening toxicity, 89% were alive 30 days after treatment. In addition, 33% of the patients resumed chemotherapy within 30 days, according to the FDA statement. Diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea were the most common adverse events associated with treatment.

Uridine was granted orphan drug, priority review, and fast track designations.

Senate calls for childproof packaging for ‘e-cig juice’

The Senate passed a bill that would require childproof packaging for liquid nicotine products.

The Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 (S. 142), also would codify Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate the packaging of liquid nicotine that is used to refill various electronic nicotine delivery systems.

S. 142 passed by unanimous consent in the Senate on Dec. 10. The House of Representatives has not taken action on the bill.

“Just a small amount of this stuff can injure or even kill a small child,” Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.), the bill’s sponsor, said in a statement. “Making these bottles childproof is just common sense.”

In 2014, poison control centers received more than 3,000 calls related to e-cigarette nicotine exposure, including one toddler death, according to a statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With e-cigarettes becoming more and more common in households across the country, we cannot afford to wait another day to protect children from poisonous liquid nicotine,” AAP President Dr. Sandra Hassink said.

The Senate passed a bill that would require childproof packaging for liquid nicotine products.

The Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 (S. 142), also would codify Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate the packaging of liquid nicotine that is used to refill various electronic nicotine delivery systems.

S. 142 passed by unanimous consent in the Senate on Dec. 10. The House of Representatives has not taken action on the bill.

“Just a small amount of this stuff can injure or even kill a small child,” Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.), the bill’s sponsor, said in a statement. “Making these bottles childproof is just common sense.”

In 2014, poison control centers received more than 3,000 calls related to e-cigarette nicotine exposure, including one toddler death, according to a statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With e-cigarettes becoming more and more common in households across the country, we cannot afford to wait another day to protect children from poisonous liquid nicotine,” AAP President Dr. Sandra Hassink said.

The Senate passed a bill that would require childproof packaging for liquid nicotine products.

The Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 (S. 142), also would codify Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate the packaging of liquid nicotine that is used to refill various electronic nicotine delivery systems.

S. 142 passed by unanimous consent in the Senate on Dec. 10. The House of Representatives has not taken action on the bill.

“Just a small amount of this stuff can injure or even kill a small child,” Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.), the bill’s sponsor, said in a statement. “Making these bottles childproof is just common sense.”

In 2014, poison control centers received more than 3,000 calls related to e-cigarette nicotine exposure, including one toddler death, according to a statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With e-cigarettes becoming more and more common in households across the country, we cannot afford to wait another day to protect children from poisonous liquid nicotine,” AAP President Dr. Sandra Hassink said.

Naloxone to revive an addict

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

First EDition: News for and about the practice of emergency medicine

FDA approves first naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose

BY DEEPAK CHITNIS

Frontline Medical News

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first nasal spray variant of the opioid-overdose drug naloxone hydrochloride.

Marketed in the United States as Narcan (Adapt Pharma, a partner of Lightlake Therapeutics, Radnor, Pennsylvania) the nasal spray is known to stop or, in some cases, reverse the effects of opioid overdosing in patients. Narcan is the first naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray approved by the FDA.

“Combating the opioid abuse epidemic is a top priority for the FDA,” Dr Stephen Ostroff, FDA acting commissioner, said in a statement released with the November 18 approval announcement. “While naloxone will not solve the underlying problems of the opioid epidemic, we are speeding to review new formulations that will ultimately save lives that might otherwise be lost to drug addiction and overdose.”1

The nasal spray itself is available only with a prescription, and is safe for use by both adults and children, according to the FDA.

The spray delivers a dose of 4 mg naloxone in a single 0.1-mL nasal spray, which comes in a ready-to-use, needle-free device, according to Adapt Pharma. Administration of Narcan, which is sprayed into one nostril while the patient is lying on his or her back, does not require special training.

The FDA warned that body aches, diarrhea, tachycardia, fever, piloerection, nausea, nervousness, abdominal cramps, weakness, and increased blood pressure, among other conditions, are all possible side effects of Narcan.

Narcan’s approval is one step of many that must be taken to adequately address and ultimately end the problem of opioid abuse in the US, cautioned Dr Peter Friedmann, an addiction medicine specialist and chief research officer at Baystate Health in Springfield, Massachusetts. He expressed concern regarding the pricing of Narcan, noting that the drug’s affordability is crucial to its success.

“Right now, nasal atomizers with syringes are used off label, and the prices have been going up with increasing demand,” he said. “But [Narcan] is a commercial product based around what is essentially a generic medication, so [I] hope it’s priced at a price point that’s accessible to the great majority of patients and their families who are facing addiction, many of whom don’t have huge means.”

Therapeutic hypothermia after nonshockable-rhythm cardiac arrest

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM CIRCULATION

Vitals Key clinical point: Therapeutic hypothermia raises the rate of survival with a good neurologic outcome in comatose patients after a cardiac arrest with a nonshockable initial rhythm. Major finding: The rate of survival-to-hospital discharge was significantly higher with therapeutic hypothermia (29%) than without it (15%), as was the rate of survival with a favorable neurologic outcome (21% vs 10%). Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 519 adults enrolled in a therapeutic hypothermia registry during a 3-year period. Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr Perman and her associates reported having no financial disclosures. |

Therapeutic hypothermia significantly raises the rate of survival with a good neurologic outcome among patients who are comatose after a cardiac arrest with a nonshockable initial rhythm, according to a report published online November 16 in Circulation.1

Many observational and retrospective cohort studies have examined the possible benefits of therapeutic hypothermia in this patient population, but they have produced conflicting results. No prospective randomized clinical trials have been published, and some clinicians insist the treatment should be reserved for patients who meet the narrow criteria for which there is good supportive evidence; others, eager for any clinical strategy that can improve the outcomes of these critically ill patients, routinely expand its use to comatose patients regardless of their initial heart rhythm or the location of the cardiac arrest, wrote Dr Sarah M. Perman of the department of emergency medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora, and her associates.

They studied the issue using data from a national registry of patients treated at 16 medical centers that sometimes use therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. They assessed the records of 519 adults who had a nontraumatic cardiac arrest and initially registered either pulseless electrical activity or asystole, then had a return of spontaneous circulation but remained comatose. Approximately half of these comatose survivors (262 patients) were treated with therapeutic hypothermia according to their hospital’s usual protocols, and the other half (257 control subjects) received standard care without therapeutic hypothermia.

In the propensity-matched cohort, the rate of survival-to-hospital discharge was significantly higher with therapeutic hypothermia (29%) than without it (15%), as was the rate of survival with a favorable neurologic outcome (21% vs 10%). And in a multivariate analysis of factors contributing to positive patient outcomes, the intervention was associated with a 3.5-fold increase in favorable neurologic outcomes. A further analysis of the data showed that therapeutic hypothermia was associated with improved survival, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.8, the investigators said.

In addition, an analysis of outcomes across various subgroups of patients showed that regardless of the location of their cardiac arrest, patients were consistently more likely to survive to hospital discharge neurologically intact if they received therapeutic hypothermia (OR, 2.1 for out-of-hospital cardiac rest; OR, 4.2 for in-hospital cardiac arrest).

“These results lend support to a broadening of indications for therapeutic hypothermia in comatose post-arrest patients with initial nonshockable rhythms,” Dr Perman and her associates said.

Andexanet reverses anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors

BY BIANCA NOGRADY

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Andexanet reverses the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban in healthy older adults. Major finding: Andexanet achieved a 92% to 94% reduction in antifactor Xa activity, compared with an 18% to 21% reduction with placebo. Data source: A two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study in 145 healthy individuals. Disclosures: The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and a related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters. |

Andexanet alfa has been found to reverse the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, according to a study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the November 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.1

In a two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 145 healthy individuals with a mean age of 58 years, patients treated first with apixaban and then given a bolus of andexanet had a 94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with a 21% reduction with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 100% of patients within 2 to 5 minutes.

In the patients treated with rivaroxaban, treatment with andexanet reduced antifactor Xa activity by 92%, compared to 18% with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 96% of participants in the andexanet group, compared with 7% in the placebo group.

Adverse events associated with andexanet were minor, including constipation, feeling hot, or a strange taste in the mouth. The effects of the andexanet also were sustained over the course of a 2-hour infusion in addition to the bolus.1

“The rapid onset and offset of action of andexanet and the ability to administer it as a bolus or as a bolus plus an infusion may provide flexibility with regard to the restoration of hemostasis when urgent factor Xa inhibitor reversal is required,” Dr Deborah M. Siegal of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada and coauthors wrote.

Continuous no better than interrupted chest compressions

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Continuous chest compressions during CPR didn’t improve survival or neurologic function compared with standard compressions briefly interrupted for ventilation. Major finding: The primary outcome – the rate of survival to hospital discharge – was 9.0% for continuous chest compressions and 9.7% for interrupted compressions, a nonsignificant difference. Data source: A cluster-randomized crossover trial involving 23,711 adults treated by 114 North American EMS agencies for nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Defence Research and Development Canada, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the American Heart Association, and the Medic One Foundation. Dr Nichol and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. |

Continuous chest compressions during CPR failed to improve survival or neurologic function compared with standard chest compressions that are briefly interrupted for ventilation, based on findings in the first large randomized trial to compare the two strategies for out-of-hospital, nontraumatic cardiac arrest.

In a presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, simultaneously published online November 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr Graham Nichol and his associates analyzed data from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium, a network of clinical centers and EMS agencies that have expertise in conducting research on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.1

Data were analyzed for 23,711 adults treated by 114 EMS agencies affiliated with eight clinical centers across the United States and Canada. These agencies were grouped into 47 clusters that were randomly assigned to perform CPR using either continuous chest compressions (100 per minute) with asynchronous positive-pressure ventilations (10 per minute) or standard chest compressions interrupted for ventilations (at a rate of 30 compressions per two ventilations) at every response to an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Twice per year, each cluster crossed over to the other resuscitation strategy, said Dr Nichol of the University of Washington–Harborview Center for Prehospital Emergency Care and Clinical Trial Center in Seattle.

A total of 12,653 patients were assigned to continuous chest compressions (the intervention group) and 11,058 to interrupted chest compressions (the control group). The primary outcome—the rate of survival to hospital discharge—was 9.0% in the intervention group and 9.7% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, the rate of survival with favorable neurologic function did not differ significantly, at 7.0% and 7.7%, respectively, the investigators said.1

However, it is also possible that three important limitations of this trial unduly influenced the results.

First, the per-protocol analysis, which used an automated algorithm to assess adherence to the compression assignments, could not classify many patients as having received either continuous or interrupted chest compressions. Second, the quality of postresuscitation care, which certainly influences outcomes, was not monitored. And third, actual oxygenation levels were not measured, nor were minutes of ventilation delivered. Thus, “we do not know whether there were important differences in oxygenation or ventilation between the two treatment strategies,” he said.

It is not yet clear why this large randomized trial1 showed no benefit from continuous chest compressions when previous observational research showed the opposite. One possibility is that many of the previous studies assessed not just chest compressions but an entire bundle of care related to CPR, so the benefits they reported may not be attributable to chest compressions alone.

In addition, in this study the mean chest-compression fraction – the proportion of each minute during which compressions are given, an important marker of interruptions in chest compressions – was already high in the control group (0.77) and not much different from that in the intervention group (0.83). Both of these are much higher than the target recommended by both American and European guidelines, which is only 0.60.

And of course a third reason may be that the interruptions for ventilation during CPR aren’t all that critical, and may be less detrimental to survival, than is currently believed.

Dr Rudolph W. Koster is in the department of cardiology at Amsterdam Academic Medical Center. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr Koster made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr Nichol’s report (Koster RW. Continuous or interrupted chest compressions for cardiac arrest [published online ahead of print November 9, 2015]. N Engl J Med).

Answers elusive in quest for better chlamydia treatment

BY BRUCE JANCIN

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICAAC 2015

SAN DIEGO – The hottest topic today in the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases caused by Chlamydia trachomatis is the unresolved question of whether azithromycin is still as effective as doxycycline, the other current guideline-recommended, first-line therapy, Dr Kimberly Workowski said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

“This is important, because doxycycline is administered twice a day for 7 days, and azithromycin is given as a single pill suitable for directly observed therapy,” noted Dr Workowski, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta and lead author of the 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention STD treatment guidelines.1

Several recent retrospective case series have suggested azithromycin is less effective, with the biggest efficacy gap being seen in rectal C. trachomatis infections. These nonrandomized studies were further supported by an Australian meta-analysis of six randomized, controlled trials comparing the two antibiotics for the treatment of genital chlamydia. The investigators found roughly 3% greater efficacy for doxycycline, compared with azithromycin, for urogenital chlamydia, and a 7% advantage for doxycycline in treating symptomatic urethral infection in men.

However, the investigators were quick to add the caveat that “the quality of the evidence varies considerably.”2

There’s a pressing need for better data. Dr Workowski and her colleagues on the STD guidelines panel are eagerly awaiting the results of a well-structured randomized trial led by Dr William M. Geisler, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. The investigators randomized more than 300 chlamydia-infected male and female inmates in youth correctional facilities to guideline-recommended azithromycin at 1 g orally in a single dose or oral doxycycline at 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. The results, which are anticipated soon, should influence clinical practice, Dr Workowski said.

Here’s what else is new in chlamydia:

Pregnancy: For treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, amoxicillin at 500 mg orally t.i.d. for 7 days has been demoted from a first-line recommended therapy to alternative-regimen status. Now, the sole recommended first-line treatment in pregnancy is oral azithromycin at 1 g orally in a single dose.

“We did this based on in vitro studies showing Chlamydia trachomatis is not well-killed by amoxicillin. Instead, the drug induces persistent viable noninfectious forms which can sometimes reactivate,” Dr Workowski explained.

Delayed-release doxycycline: This FDA-approved drug, known as Doryx, administered as a 200-mg tablet once daily for 7 days, “might be an alternative” to the standard generic doxycycline regimen of 100 mg twice daily for 7 days, according to the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. In a randomized, double-blind trial, the new agent was as effective as twice-daily generic doxycycline in men and women with urogenital C. trachomatis infection, and it had fewer gastrointestinal side effects. Doryx is costlier than the twice-daily alternatives.

Lymphogranuloma venereum: The current guidelines repeat a point made in previous editions, but one Dr Workowski believes remains underappreciated and thus worthy of emphasis: Rectal exposure to C. trachomatis serovars L1, L2, and L3 in men who have sex with men or in women who have rectal sex can cause lymphogranuloma venereum, which takes the form of proctocolitis mimicking inflammatory bowel disease.

Patients suspected of having lymphogranuloma venereum should be started presumptively on the recommended regimen for this STD, which is oral doxycycline at 100 mg b.i.d. for 21 days.

“If you also see painful ulcers or, on anoscopy, mucosal ulcers, you should also treat empirically for herpes simplex until your culture results come back,” she added.

Dr Workowski reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis trumps systemic for acute pulmonary embolism

BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

AT CHEST 2015

Vitals Key clinical point: Catheter-directed thrombolysis was linked to reduced mortality, compared with systemic thrombolysis in patients with an acute pulmonary embolism. Major finding: In-hospital mortality in acute pulmonary embolism patients ran 10% with catheter-directed thrombolysis and 17% with systemic thrombolysis. Data source: Review of 1,521 US patients treated for acute pulmonary embolism during 2010-2012 in the National Inpatient Sample. Disclosures: Dr Saqib and Dr Muthiah had no disclosures. |

MONTREAL – Catheter-directed thrombolysis surpassed systemic thrombolysis for minimizing in-hospital mortality of patients with an acute pulmonary embolism in a review of more than 1,500 United States patients.

The review also found evidence that US pulmonary embolism (PE) patients increasingly undergo catheter-directed thrombolysis, with usage jumping by more than 50% from 2010 to 2012, although in 2012 US clinicians performed catheter-directed thrombolysis on 160 patients with an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) who were included in a national US registry of hospitalized patients, Dr Amina Saqib said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis resulted in a 9% in-hospital mortality rate and a 10% combined rate of in-hospital mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhages, rates significantly below those tallied in propensity score-matched patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis of their acute PE. The matched group with systemic thrombolysis had a 17% in-hospital mortality rate and a 17% combined mortality plus intracerebral hemorrhage rate, said Dr Saqib, a researcher at Staten Island (New York) University Hospital.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first, large, nationwide, observational study that compared safety and efficacy outcomes between systemic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis in acute PE,”

Dr Saqib said.

The US data, collected during 2010-2012, also showed that, after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables, each acute PE treatment by catheter-directed thrombolysis cost an average $9,428 above the cost for systemic thrombolysis, she said.

Dr Saqib and her associates used data collected by the Federal National Inpatient Sample. Among US patients hospitalized during 2010-2012 and entered into this database, they identified 1,169 adult acute PE patients who underwent systemic thrombolysis and 352 patients who received catheter-directed thrombolysis. The patients averaged about 58 years old and just under half were men.

The propensity score-adjusted analysis also showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment approaches for the incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage, any hemorrhages requiring a transfusion, new-onset acute renal failure, or hospital length of stay. Among the patients treated by catheter-directed thrombolysis, all the intracerebral hemorrhages occurred during 2010; during 2011 and 2012 none of the patients treated this way had an intracerebral hemorrhage, Dr Saqib noted.

Although the findings were consistent with results from prior analyses, the propensity-score adjustment used in the current study cannot fully account for all unmeasured confounding factors. The best way to compare catheter-directed thrombolysis and systemic thrombolysis for treating acute PE would be in a prospective, randomized study, Dr Saqib said.

Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest usually had intact brain function

BY AMY KARON

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Most adults who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrests remained neurologically intact, regardless of duration of CPR in the field. Major finding: Only 12% of patients survived, but 84% of survivors had a cerebral performance category of 1 or 2, including 10% who underwent more than 35 minutes of CPR before reaching the hospital. Data source: A retrospective observational study of 3,814 adults who had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest between 2005 and 2014. Disclosures: Dr Williams had no disclosures. The senior author disclosed research funding from the Medtronic Foundation. |

Most adults who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrests remained neurologically intact, even if cardiopulmonary resuscitation lasted longer than has been recommended, authors of a retrospective observational study reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr Jefferson Williams of the Wake County Department of Emergency Medical Services in Raleigh, North Carolina, and his associates studied 3,814 adults who had a cardiac arrest outside the hospital between 2005 and 2014. Only 12% of patients survived, but 84% of survivors had a cerebral performance category of 1 or 2, including 10% who underwent more than 35 minutes of CPR before reaching the hospital.

Neurologically intact survival was associated with having an initial shockable rhythm, a bystander-witnessed arrest, and return of spontaneous circulation in the field rather than in the hospital. Age, basic airway management, and therapeutic hypothermia phase also predicted survival with intact brain function, but duration of CPR did not.

Procalcitonin assay detects invasive bacterial infection

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Vitals Key clinical point: The procalcitonin assay was superior to three other tests at detecting invasive bacterial infection in febrile infants aged 7-91 days. Major finding: At a threshold of 0.3 ng/mL or more, procalcitonin level detected invasive bacterial infections with a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 78%, and a negative predictive value of 0.1. Data source: A multicenter prospective cohort study involving 2,047 infants treated at pediatric EDs in France during a 30-month period. Disclosures: The French Health Ministry funded the study. Dr Milcent and her associates reported having no financial disclosures. |

The procalcitonin assay was superior to C-reactive protein, neutrophil, and white blood cell measurements at identifying invasive bacterial infections in very young febrile infants, according to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.1

Compared with other biomarker assays, procalcitonin assays allow earlier detection of certain infections in older children. A few small studies have hinted at the usefulness of procalcitonin assays in infants, but to date no large prospective studies have assessed these assays in the youngest infants. For this prospective study, researchers evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin and other biomarkers in a study of 2,047 febrile infants aged 7-91 days who presented to 15 pediatric emergency departments in France during a 30-month period.

“We did not include infants 6 days or younger because they are likely to have early-onset sepsis related to perinatal factors and because physiologic procalcitonin concentrations during the first [few] days of life are higher than thereafter,” said Dr Karen Milcent of Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart (France), and her associates.

Serum samples were collected at the initial clinical examination, but procalcitonin assays were not performed at that time. Attending physicians diagnosed the infants as having either bacterial or nonbacterial infections without knowing the procalcitonin results. Then, procalcitonin tests were done retrospectively on frozen serum samples by lab personnel who were blinded to the infants’ clinical features. Thirteen (1.0%) infants had bacteremia and 8 (0.6%) had bacterial meningitis.

The procalcitonin assay was significantly more accurate at identifying invasive bacterial infections than was C-reactive protein level, absolute neutrophil count, or white blood cell count. At a threshold of 0.3 ng/mL or more, the procalcitonin level had a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 78%, and a negative predictive value of 0.1. In addition, the procalcitonin assay was the most accurate in a subgroup analysis restricted to patients whose fever duration was less than 6 hours and another subgroup analysis restricted to patients younger than 1 month of age, the researchers said.1

For young febrile infants, combining procalcitonin assay results with a careful case history, a thorough physical examination, and other appropriate testing offers the potential of avoiding lumbar punctures. These study findings “should encourage the development of decision-making rules that incorporate procalcitonin,” Dr Milcent and her associates said.

The findings by Milcent et al are an important step forward in managing very young febrile infants, which remains a vexing problem.

A vital next step is to find alternatives to culture-based testing of blood, urine, and CSF. Genomic technologies that reliably detect molecular signatures in small amounts of biologic samples may be one such alternative. They may offer the additional benefit of identifying the pathogen and the host’s response to the presence of the pathogen.

Dr Nathan Kuppermann is in the departments of emergency medicine and pediatrics at the University of California–Davis. Dr Prashant Mahajan is in the departments of pediatrics and emergency medicine at Children’s Hospital of Michigan and Wayne State University, Detroit. They have no relevant financial disclosures. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr Milcent’s report (Kuppermann N, Mahajan P. Role of serum procalcitonin in identifying young febrile infants with invasive bacterial infections: one step closer to the holy grail [published online ahead of print November 23, 2015]? JAMA Ped. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3267).

Out-of-hospital MI survival is best in the Midwest

BY BRUCE JANCIN

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Substantial and as-yet unexplained regional differences in survival and total hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest exist across the United States. Major finding: Mortality among adults hospitalized after experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was 14% lower in the Midwest than in the Northeast. Data source: A retrospective analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2002-2012 that included 155,592 adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who survived to hospital admission. Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest. |

ORLANDO – Considerable regional variation exists across the United States in outcomes, including survival and hospital charges following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Dr Aiham Albaeni reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.1

He presented an analysis of 155,592 adults who survived at least until hospital admission following non-trauma-related out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) during 2002-2012. The data came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample, the largest all-payer US inpatient database.

Mortality was lowest among patients whose OHCA occurred in the Midwest. Indeed, taking the Northeast region as the reference point in a multivariate analysis, the adjusted mortality risk was 14% lower in the Midwest and 9% lower in the South. There was no difference in survival rates between the West and Northeast in this analysis adjusted for age, gender, race, primary diagnosis, income, Charlson Comorbidity Index, primary payer, and hospital size and teaching status, reported Dr Albaeni of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Total hospital charges for patients admitted following OHCA were far and away highest in the West, and this increased expenditure didn’t pay off in terms of a survival advantage. The Consumer Price Index–adjusted mean total hospital charges averaged $85,592 per patient in the West, $66,290 in the Northeast, $55,257 in the Midwest, and $54,878 in the South.

Outliers in terms of cost of care—that is, patients admitted with OHCA whose total hospital charges exceeded $109,000 per admission—were 85% more common in the West than the other three regions, he noted.

Hospital length of stay greater than 8 days occurred most often in the Northeast. These lengthier stays were 10% to 12% less common in the other regions.

The explanation for the marked regional differences observed in this study remains unknown.

“These findings call for more efforts to identify a high-quality model of excellence that standardizes health care delivery and improves quality of care in low-performing regions,” said Dr Albaeni.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study.

Modified Valsalva more than doubled conversion rate in supraventricular tachycardia

BY AMY KARON

FROM THE LANCET

Vitals Key clinical point: A modified version of the Valsalva maneuver, in which patients were immediately laid flat afterward with their legs passively raised, more than doubled the rate of conversion from acute supraventricular tachycardia to normal sinus rhythm as compared with the standard Valsalva maneuver. Major finding: The conversion rate was 43% for the modified Valsalva group and 17% for patients undergoing the standard maneuver (adjusted OR, 3.7; P < .0001). Data source: Multicenter, randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial of 428 patients presenting to emergency departments with acute SVT. Disclosures: The National Institute for Health Research funded the study. The investigators declared no competing interests. |

A modified version of the Valsalva maneuver more than doubled the rate of conversion from acute supraventricular tachycardia to normal sinus rhythm when compared with the standard maneuver, said authors of a randomized, controlled trial published in the Lancet.

In all, 93 of 214 (43%) emergency department patients with acute supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) achieved cardioversion a minute after treatment with the modified Valsalva maneuver, compared with 37 (17%) of patients treated with standard Valsalva (adjusted odds ratio, 3.7; 95% CI, 2.3-5.8; P < .0001), reported Dr Andrew Appelboam of Royal Devon and Exeter (England) Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and his associates.

Standard Valsalva is safe, but achieves cardioversion for only 5% to 20% of patients with acute SVT. Nonresponders usually receive intravenous adenosine, which causes transient asystole and has other side effects, including a sense of “impending doom” or imminent death, the investigators noted.1

For the modified Valsalva maneuver, patients underwent standardized strain at 40 mm Hg pressure for 15 seconds while semi-recumbent, but then immediately laid flat while a staff member raised their legs to a 45-degree angle for 15 seconds. They returned to the semi-recumbent position for another 45 seconds before their cardiac rhythm was reassessed. The control group simply remained semirecumbent for 60 seconds after 15 seconds of Valsalva strain.

The adapted technique should achieve the same rate of cardioversion in community practice, and clinicians should repeat it once if it is not initially effective, said the researchers. “As long as individuals can safely undertake a Valsalva strain and be repositioned as described, this maneuver can be used as the routine initial treatment for episodes of supraventricular tachycardia regardless of location,” they said. Patients did not experience serious adverse effects, and transient cardiac events were self-limited and affected similar proportions of both groups, they added.

The National Institute for Health Research funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

Off-label prescriptions link to more adverse events

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Vitals Key clinical point: Off-label prescribing in adults is common and very likely to cause adverse events. Major finding: The incidence of adverse events was 44% higher for off-label use (19.7 per 10,000 person-months) than for on-label use (12.5 per 10,000 person-months) of prescription drugs. Data source: A prospective cohort study of 46,021 adults who received 151,305 incident prescriptions from primary care clinicians in Quebec during a 5-year period. Disclosures: No sponsors were identified for this study. Dr Tewodros Eguale and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures. |

Off-label prescribing of drugs is common and very likely to cause adverse events, particularly when no strong scientific evidence supports the off-label use, according to a report published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

No systematic investigation of the off-label use of prescription drugs has been done to date, in part because physicians aren’t required to document intended indications. Recent innovations in electronic health records provided an opportunity to track off-label prescribing and its influence on adverse drug events for all 8.5 million residents in the Canadian province of Quebec. There, physicians must provide the indication for every new prescription, the reason for any dose changes or drug discontinuation, and the nature of any adverse events, said Dr Tewodros Eguale of the department of epidemiology, biostatistics, and occupational health at McGill University, Montreal, and his associates.

“Selected examples of adverse events associated with the most frequently used off-label drugs include akathisia resulting from the use of gabapentin for neurogenic pain; agitation associated with the use of amitriptyline hydrochloride for migraine; hallucinations with the use of trazodone hydrochloride for insomnia; QT interval prolongation with the use of quetiapine fumarate for depression; and weight gain with the use of olanzapine for depression,” the authors reported.

Prescribing information in electronic medical records of 46,021 adults (mean age 58 years) given 151,305 new prescriptions was analyzed during a 5-year period. Physicians reported off-label use in 17,847 (12%) of these prescriptions, and that off-label use lacked strong scientific evidence in 81% of cases. The median follow-up time for use of prescribed medications was 386 days (range, 1 day to 6 years).

The class of drugs with the highest rate of adverse effects was anti-infective agents (66.2 per 10,000 person-months), followed by central nervous system drugs such as antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antimigraine medicine (18.1 per 10,000); cardiovascular drugs (15.9 per 10,000); hormonal agents (12.7); autonomic drugs including albuterol and terbutaline (8.4); gastrointestinal drugs (6.1); ear, nose, and throat medications (2.8); and “other” agents such as antihistamines, blood thinners, and antineoplastics (1.3).

“Off-label use may be clinically appropriate given the complexity of the patient’s condition, the lack of alternative effective drugs, or after exhausting approved drugs.” However, previous research has shown that physicians’ lack of knowledge of approved treatment indications was one important factor contributing to off-label prescribing. And one study showed that physicians are finding it difficult to keep up with rapidly changing medication information, and this lack of knowledge is affecting treatment, Dr Eguale and his associates said.

That knowledge gap could be filled by supplying clinicians with information regarding drug approval status and the quality of supporting scientific evidence at the point of care, when they write prescriptions into patients’ electronic health records, the investigators noted. This would have the added advantage of facilitating communication among physicians, pharmacists, and patients, and could reduce medication errors such as those caused by giving drugs to the wrong patients or by giving patients sound-alike or look-alike drugs.

No sponsors were identified for this study. Dr Tewodros Eguale and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

This study, the most extensive and informative one to evaluate the safety of off-label drug use in adults to date, shows that clinicians often enter an arena of the unknown when they expand prescribing beyond the carefully devised confines of the labeled indication. It provides compelling evidence that off-label prescribing is frequently inappropriate and substantially raises the risk for an adverse event.

Even in cases in which an off-label indication has been studied, the pharmacokinetics, drug-disease interactions, drug-drug interactions, and other safety considerations weren’t studied to the degree required during the drug approval process. Moreover, how many clinicians have the time or motivation to review the evidence for those off-label indications, arriving at a balanced assessment of risks and benefits?

Dr Chester B. Good is in pharmacy benefits management services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs in Hines, Illinois, and the department of pharmacy and therapeutics at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr Good and Dr Walid F. Gellad are in the department of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and at the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion in the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System. Dr Good and Dr Gellad reported serving as unpaid advisers to the Food and Drug Administration’s Drug Safety Oversight Board. They made these remarks in an Invited Commentary accompanying Dr Eguale’s report (Good CB, Gellad WF. Off-label drug use and adverse drug events: turning up the heat on off-label prescribing [published online ahead of print November 2, 2014]. JAMA Intern Med. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6068).

Dr Lappin is an assistant professor and an attending physician, department of mergency medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

- FDA approves first naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose

- FDA moves quickly to approve easy-to-use nasal spray to treat opioid overdose [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; November 18, 2015. Updated November 19, 2015.

- Therapeutic hypothermia after nonshockable-rhythm cardiac arrest

- Perman SM, Grossestreuer AV, Wiee DJ, Carr BG, Abella BS, Gaieski DF. The utility of therapeutic hypothermia for post-cardiac arrest syndrome patients with an initial non-shockable rhythm [published online ahead of print November 16, 2015]. Circulation. pii:CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016317.

- Andexanet reverses anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors

- Siegal DM, Cornutte JT, Connolly SJ, et al. Andexanet alfa for the reversal of factor Xa inhibitor activity [published online ahead of print November 11, 2015]. N Engl J Med.

- Continuous no better than interrupted chest compressions

- Nichol G, Leroux B, Wang H, et al; ROC Investigators. Trial of continuous or interrupted chest compressions during CPR [published online ahead of print November 9, 2015]. N Engl J Med.

- Answers elusive in quest for better chlamydia treatment

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

- Kong FY, Tabrizi SN, Law M, et al. Azithrmycin versus doxycycline for the treatment of genital chlamydia infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):193-205.

- Procalcitonin assay detects invasive bacterial infection

- Milcent K, Faesch S, Gras-Le Guen C, et al. Use of procalcitonin assays to predict serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants [published online ahead of print November 23, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3210.

- Out-of-hospital MI survival is best in the Midwest

- Shaker M, Albaeni A, Rios R. Impact of Change in Resuscitation Guidelines on National Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes: Fulfilled Expectations? Paper presented at: American Heart Association 2015 Scientific Sessions; November 7-11, 2015; Orlando, Florida.

- Modified Valsalva more than doubled conversion rate in supraventricular tachycardia

- Appelboam A, Reuben A, Mann C, et al; REVERT trial collaborators. Postural modification to the standard Valsalva manoeuvre for emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardias (REVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10005):1747-1753.

- Off-label prescriptions link to more adverse events

- Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Verma A, et al. Association of off-label drug use and adverse drug events in an adult population [published online ahead of print November 2, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6058.

FDA approves first naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose

BY DEEPAK CHITNIS

Frontline Medical News

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first nasal spray variant of the opioid-overdose drug naloxone hydrochloride.

Marketed in the United States as Narcan (Adapt Pharma, a partner of Lightlake Therapeutics, Radnor, Pennsylvania) the nasal spray is known to stop or, in some cases, reverse the effects of opioid overdosing in patients. Narcan is the first naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray approved by the FDA.

“Combating the opioid abuse epidemic is a top priority for the FDA,” Dr Stephen Ostroff, FDA acting commissioner, said in a statement released with the November 18 approval announcement. “While naloxone will not solve the underlying problems of the opioid epidemic, we are speeding to review new formulations that will ultimately save lives that might otherwise be lost to drug addiction and overdose.”1

The nasal spray itself is available only with a prescription, and is safe for use by both adults and children, according to the FDA.

The spray delivers a dose of 4 mg naloxone in a single 0.1-mL nasal spray, which comes in a ready-to-use, needle-free device, according to Adapt Pharma. Administration of Narcan, which is sprayed into one nostril while the patient is lying on his or her back, does not require special training.

The FDA warned that body aches, diarrhea, tachycardia, fever, piloerection, nausea, nervousness, abdominal cramps, weakness, and increased blood pressure, among other conditions, are all possible side effects of Narcan.

Narcan’s approval is one step of many that must be taken to adequately address and ultimately end the problem of opioid abuse in the US, cautioned Dr Peter Friedmann, an addiction medicine specialist and chief research officer at Baystate Health in Springfield, Massachusetts. He expressed concern regarding the pricing of Narcan, noting that the drug’s affordability is crucial to its success.

“Right now, nasal atomizers with syringes are used off label, and the prices have been going up with increasing demand,” he said. “But [Narcan] is a commercial product based around what is essentially a generic medication, so [I] hope it’s priced at a price point that’s accessible to the great majority of patients and their families who are facing addiction, many of whom don’t have huge means.”

Therapeutic hypothermia after nonshockable-rhythm cardiac arrest

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM CIRCULATION

Vitals Key clinical point: Therapeutic hypothermia raises the rate of survival with a good neurologic outcome in comatose patients after a cardiac arrest with a nonshockable initial rhythm. Major finding: The rate of survival-to-hospital discharge was significantly higher with therapeutic hypothermia (29%) than without it (15%), as was the rate of survival with a favorable neurologic outcome (21% vs 10%). Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 519 adults enrolled in a therapeutic hypothermia registry during a 3-year period. Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr Perman and her associates reported having no financial disclosures. |

Therapeutic hypothermia significantly raises the rate of survival with a good neurologic outcome among patients who are comatose after a cardiac arrest with a nonshockable initial rhythm, according to a report published online November 16 in Circulation.1

Many observational and retrospective cohort studies have examined the possible benefits of therapeutic hypothermia in this patient population, but they have produced conflicting results. No prospective randomized clinical trials have been published, and some clinicians insist the treatment should be reserved for patients who meet the narrow criteria for which there is good supportive evidence; others, eager for any clinical strategy that can improve the outcomes of these critically ill patients, routinely expand its use to comatose patients regardless of their initial heart rhythm or the location of the cardiac arrest, wrote Dr Sarah M. Perman of the department of emergency medicine, University of Colorado, Aurora, and her associates.

They studied the issue using data from a national registry of patients treated at 16 medical centers that sometimes use therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. They assessed the records of 519 adults who had a nontraumatic cardiac arrest and initially registered either pulseless electrical activity or asystole, then had a return of spontaneous circulation but remained comatose. Approximately half of these comatose survivors (262 patients) were treated with therapeutic hypothermia according to their hospital’s usual protocols, and the other half (257 control subjects) received standard care without therapeutic hypothermia.

In the propensity-matched cohort, the rate of survival-to-hospital discharge was significantly higher with therapeutic hypothermia (29%) than without it (15%), as was the rate of survival with a favorable neurologic outcome (21% vs 10%). And in a multivariate analysis of factors contributing to positive patient outcomes, the intervention was associated with a 3.5-fold increase in favorable neurologic outcomes. A further analysis of the data showed that therapeutic hypothermia was associated with improved survival, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.8, the investigators said.

In addition, an analysis of outcomes across various subgroups of patients showed that regardless of the location of their cardiac arrest, patients were consistently more likely to survive to hospital discharge neurologically intact if they received therapeutic hypothermia (OR, 2.1 for out-of-hospital cardiac rest; OR, 4.2 for in-hospital cardiac arrest).

“These results lend support to a broadening of indications for therapeutic hypothermia in comatose post-arrest patients with initial nonshockable rhythms,” Dr Perman and her associates said.

Andexanet reverses anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors

BY BIANCA NOGRADY

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Andexanet reverses the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban in healthy older adults. Major finding: Andexanet achieved a 92% to 94% reduction in antifactor Xa activity, compared with an 18% to 21% reduction with placebo. Data source: A two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study in 145 healthy individuals. Disclosures: The study was supported by Portola Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer. Several authors are employees of Portola, one with stock options and a related patent. Other authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including the study supporters. |

Andexanet alfa has been found to reverse the anticoagulant effects of factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban, according to a study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the November 11 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.1

In a two-part randomized, placebo-controlled study involving 145 healthy individuals with a mean age of 58 years, patients treated first with apixaban and then given a bolus of andexanet had a 94% reduction in anti-factor Xa activity, compared with a 21% reduction with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 100% of patients within 2 to 5 minutes.

In the patients treated with rivaroxaban, treatment with andexanet reduced antifactor Xa activity by 92%, compared to 18% with placebo. Thrombin generation was restored in 96% of participants in the andexanet group, compared with 7% in the placebo group.

Adverse events associated with andexanet were minor, including constipation, feeling hot, or a strange taste in the mouth. The effects of the andexanet also were sustained over the course of a 2-hour infusion in addition to the bolus.1

“The rapid onset and offset of action of andexanet and the ability to administer it as a bolus or as a bolus plus an infusion may provide flexibility with regard to the restoration of hemostasis when urgent factor Xa inhibitor reversal is required,” Dr Deborah M. Siegal of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada and coauthors wrote.

Continuous no better than interrupted chest compressions

BY MARY ANN MOON

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Vitals Key clinical point: Continuous chest compressions during CPR didn’t improve survival or neurologic function compared with standard compressions briefly interrupted for ventilation. Major finding: The primary outcome – the rate of survival to hospital discharge – was 9.0% for continuous chest compressions and 9.7% for interrupted compressions, a nonsignificant difference. Data source: A cluster-randomized crossover trial involving 23,711 adults treated by 114 North American EMS agencies for nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Defence Research and Development Canada, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the American Heart Association, and the Medic One Foundation. Dr Nichol and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. |