User login

Metronidazole and alcohol

A 32-year-old man develops diarrhea after receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate to treat an infection following a dog bite. He is diagnosed with Clostridium difficile and prescribed a 10-day course of metronidazole. He has no other medical problems. He will be the best man at his brother’s wedding tomorrow. What advice should you give him about alcohol use at the reception?

A. Do not take metronidazole the day of the wedding if you will be drinking alcohol.

B. Take metronidazole, do not drink alcohol.

C. It’s okay to drink alcohol.

For years, we have advised patients to not use alcohol if they are taking metronidazole because of concern for a disulfiram-like reaction between alcohol and metronidazole. This has been a standard warning given by physicians and appears as a contraindication in the prescribing information. It has been well accepted as a true, proven reaction.

Is it true?

As early as the 1960s, case reports and an uncontrolled study suggested that combining metronidazole with alcohol produced a disulfiram-like reaction, with case reports of severe reactions, including death.1, 2, 3 This was initially considered an area that might be therapeutic in the treatment of alcoholism, but several studies showed no benefit.4, 5

Caroline S. Williams and Dr. Kevin R. Woodcock reviewed the case reports for evidence of proof of a true interaction between metronidazole and ethanol.6 The case reports referenced textbooks to substantiate the interaction, but they did not present clear evidence of an interaction as the cause of elevated acetaldehyde levels.

Researchers have shown in a rat model that metronidazole can increase intracolonic, but not blood, acetaldehyde levels in rats that have received a combination of ethanol and metronidazole.7 Metronidazole did not have any inhibitory effect on hepatic or colonic alcohol dehydrogenase or aldehyde dehydrogenase. What was found was that rats treated with metronidazole had increased growth of Enterobacteriaceae, an alcohol dehydrogenase–containing aerobe, which could be the cause of the higher intracolonic acetaldehyde levels.

Jukka-Pekka Visapää and his colleagues studied the effect of coadministration of metronidazole and ethanol in young, healthy male volunteers.8 The study was a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The study was small, with 12 participants. One-half of the study participants received metronidazole three times a day for 5 days; the other half received placebo. All participants then received ethanol 0.4g/kg, with blood testing being done every 20 minutes for the next 4 hours. Blood was tested for ethanol concentrations and for acetaldehyde levels. The study participants also had blood pressure, pulse, skin temperature, and symptoms monitored during the study.

There was no difference in blood acetaldehyde levels, vital signs, or symptoms between patients who received metronidazole or placebo. None of the subjects in the study had any measurable symptoms.

Metronidazole has many side effects, including nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and seizures. These symptoms have a great deal of overlap with the symptoms of alcohol-disulfiram interaction. It has been assumed in early case reports that metronidazole caused a similar interaction with alcohol and raised acetaldehyde levels by interfering with aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Animal models and the human study do not show this to be the case. It is possible that metronidazole side effects alone were the cause of the symptoms in case reports. The one human study done was on healthy male volunteers, so projecting the results to a population with liver disease or other serious illness is a bit of a stretch. I think that if a problem exists with alcohol and metronidazole, it is uncommon and unlikely to occur in healthy individuals.

So, what would I advise the patient in the case about whether he can drink alcohol? I think that the risk would be minimal and that it would be safe for him to drink alcohol.

References

1. Br J Clin Pract. 1985 Jul;39(7):292-3.

2. Psychiatr Neurol. 1966;152:395-401.

3. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996 Dec;17(4):343-6.

4. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1972 Sep;33: 734-40.

5. Q J Stud Ethanol. 1969 Mar;30: 140-51.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Feb;34(2):255-7.

7. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000 Apr;24(4):570-5.

8. Ann Pharmacother. 2002 Jun;36(6):971-4.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 32-year-old man develops diarrhea after receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate to treat an infection following a dog bite. He is diagnosed with Clostridium difficile and prescribed a 10-day course of metronidazole. He has no other medical problems. He will be the best man at his brother’s wedding tomorrow. What advice should you give him about alcohol use at the reception?

A. Do not take metronidazole the day of the wedding if you will be drinking alcohol.

B. Take metronidazole, do not drink alcohol.

C. It’s okay to drink alcohol.

For years, we have advised patients to not use alcohol if they are taking metronidazole because of concern for a disulfiram-like reaction between alcohol and metronidazole. This has been a standard warning given by physicians and appears as a contraindication in the prescribing information. It has been well accepted as a true, proven reaction.

Is it true?

As early as the 1960s, case reports and an uncontrolled study suggested that combining metronidazole with alcohol produced a disulfiram-like reaction, with case reports of severe reactions, including death.1, 2, 3 This was initially considered an area that might be therapeutic in the treatment of alcoholism, but several studies showed no benefit.4, 5

Caroline S. Williams and Dr. Kevin R. Woodcock reviewed the case reports for evidence of proof of a true interaction between metronidazole and ethanol.6 The case reports referenced textbooks to substantiate the interaction, but they did not present clear evidence of an interaction as the cause of elevated acetaldehyde levels.

Researchers have shown in a rat model that metronidazole can increase intracolonic, but not blood, acetaldehyde levels in rats that have received a combination of ethanol and metronidazole.7 Metronidazole did not have any inhibitory effect on hepatic or colonic alcohol dehydrogenase or aldehyde dehydrogenase. What was found was that rats treated with metronidazole had increased growth of Enterobacteriaceae, an alcohol dehydrogenase–containing aerobe, which could be the cause of the higher intracolonic acetaldehyde levels.

Jukka-Pekka Visapää and his colleagues studied the effect of coadministration of metronidazole and ethanol in young, healthy male volunteers.8 The study was a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The study was small, with 12 participants. One-half of the study participants received metronidazole three times a day for 5 days; the other half received placebo. All participants then received ethanol 0.4g/kg, with blood testing being done every 20 minutes for the next 4 hours. Blood was tested for ethanol concentrations and for acetaldehyde levels. The study participants also had blood pressure, pulse, skin temperature, and symptoms monitored during the study.

There was no difference in blood acetaldehyde levels, vital signs, or symptoms between patients who received metronidazole or placebo. None of the subjects in the study had any measurable symptoms.

Metronidazole has many side effects, including nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and seizures. These symptoms have a great deal of overlap with the symptoms of alcohol-disulfiram interaction. It has been assumed in early case reports that metronidazole caused a similar interaction with alcohol and raised acetaldehyde levels by interfering with aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Animal models and the human study do not show this to be the case. It is possible that metronidazole side effects alone were the cause of the symptoms in case reports. The one human study done was on healthy male volunteers, so projecting the results to a population with liver disease or other serious illness is a bit of a stretch. I think that if a problem exists with alcohol and metronidazole, it is uncommon and unlikely to occur in healthy individuals.

So, what would I advise the patient in the case about whether he can drink alcohol? I think that the risk would be minimal and that it would be safe for him to drink alcohol.

References

1. Br J Clin Pract. 1985 Jul;39(7):292-3.

2. Psychiatr Neurol. 1966;152:395-401.

3. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996 Dec;17(4):343-6.

4. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1972 Sep;33: 734-40.

5. Q J Stud Ethanol. 1969 Mar;30: 140-51.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Feb;34(2):255-7.

7. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000 Apr;24(4):570-5.

8. Ann Pharmacother. 2002 Jun;36(6):971-4.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 32-year-old man develops diarrhea after receiving amoxicillin/clavulanate to treat an infection following a dog bite. He is diagnosed with Clostridium difficile and prescribed a 10-day course of metronidazole. He has no other medical problems. He will be the best man at his brother’s wedding tomorrow. What advice should you give him about alcohol use at the reception?

A. Do not take metronidazole the day of the wedding if you will be drinking alcohol.

B. Take metronidazole, do not drink alcohol.

C. It’s okay to drink alcohol.

For years, we have advised patients to not use alcohol if they are taking metronidazole because of concern for a disulfiram-like reaction between alcohol and metronidazole. This has been a standard warning given by physicians and appears as a contraindication in the prescribing information. It has been well accepted as a true, proven reaction.

Is it true?

As early as the 1960s, case reports and an uncontrolled study suggested that combining metronidazole with alcohol produced a disulfiram-like reaction, with case reports of severe reactions, including death.1, 2, 3 This was initially considered an area that might be therapeutic in the treatment of alcoholism, but several studies showed no benefit.4, 5

Caroline S. Williams and Dr. Kevin R. Woodcock reviewed the case reports for evidence of proof of a true interaction between metronidazole and ethanol.6 The case reports referenced textbooks to substantiate the interaction, but they did not present clear evidence of an interaction as the cause of elevated acetaldehyde levels.

Researchers have shown in a rat model that metronidazole can increase intracolonic, but not blood, acetaldehyde levels in rats that have received a combination of ethanol and metronidazole.7 Metronidazole did not have any inhibitory effect on hepatic or colonic alcohol dehydrogenase or aldehyde dehydrogenase. What was found was that rats treated with metronidazole had increased growth of Enterobacteriaceae, an alcohol dehydrogenase–containing aerobe, which could be the cause of the higher intracolonic acetaldehyde levels.

Jukka-Pekka Visapää and his colleagues studied the effect of coadministration of metronidazole and ethanol in young, healthy male volunteers.8 The study was a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. The study was small, with 12 participants. One-half of the study participants received metronidazole three times a day for 5 days; the other half received placebo. All participants then received ethanol 0.4g/kg, with blood testing being done every 20 minutes for the next 4 hours. Blood was tested for ethanol concentrations and for acetaldehyde levels. The study participants also had blood pressure, pulse, skin temperature, and symptoms monitored during the study.

There was no difference in blood acetaldehyde levels, vital signs, or symptoms between patients who received metronidazole or placebo. None of the subjects in the study had any measurable symptoms.

Metronidazole has many side effects, including nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and seizures. These symptoms have a great deal of overlap with the symptoms of alcohol-disulfiram interaction. It has been assumed in early case reports that metronidazole caused a similar interaction with alcohol and raised acetaldehyde levels by interfering with aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Animal models and the human study do not show this to be the case. It is possible that metronidazole side effects alone were the cause of the symptoms in case reports. The one human study done was on healthy male volunteers, so projecting the results to a population with liver disease or other serious illness is a bit of a stretch. I think that if a problem exists with alcohol and metronidazole, it is uncommon and unlikely to occur in healthy individuals.

So, what would I advise the patient in the case about whether he can drink alcohol? I think that the risk would be minimal and that it would be safe for him to drink alcohol.

References

1. Br J Clin Pract. 1985 Jul;39(7):292-3.

2. Psychiatr Neurol. 1966;152:395-401.

3. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996 Dec;17(4):343-6.

4. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1972 Sep;33: 734-40.

5. Q J Stud Ethanol. 1969 Mar;30: 140-51.

6. Ann Pharmacother. 2000 Feb;34(2):255-7.

7. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000 Apr;24(4):570-5.

8. Ann Pharmacother. 2002 Jun;36(6):971-4.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Prescription opioid overdoses targeted in new CDC program

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program aimed at helping states combat and prevent opioid drug overdoses.

The Prescription Drug Overdose: Prevention for States program will be launching in 16 states chosen in a competitive application process. The CDC is committing $20 million in fiscal year 2015, and each state will receive $750,000 to $1 million each year for the next 4 years to advance prevention in several areas, such as enhancing prescription drug–monitoring programs, putting prevention into action in communities nationwide, and investigating the connection between prescription opioid abuse and heroin use, the CDC said in a press release.

In 2013, 16,000 people died from prescription opioid overdoses, four times more than in 1999, with prescription of opioids increasing at the same rate over the same time. Despite more opioids being prescribed, the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. In addition, heroin deaths also have spiked, with the 8,000 heroin overdose deaths nearly three times as many as in 2010.

“The prescription drug overdose epidemic requires a multifaceted approach, and states are key partners in our efforts on the front lines to prevent overdose deaths. With this funding, states can improve their ability to track the problem, work with insurers to help providers make informed prescribing decisions, and take action to combat this epidemic,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Sylvia M. Burwell said in the release.

Find the full CDC press release here.

First EDition: News for and about the practice of Emergency Medicine

More bicyclists, more fatalities

BY RICHARD FRANKI

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

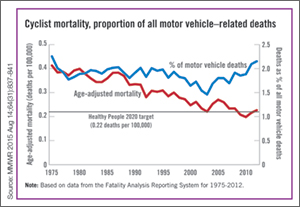

| The annual rate for bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicles dropped 44% from 1975 to 2012, but the downward trend has slowed in recent years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. |

Annual mortality among cyclists for all motor vehicle-related deaths was 0.23 per 100,000 in 2012, a decline of 44% since 1975 when the rate was 0.41 per 100,000. But the rate is up from just under 0.20 per 100,000 in 2010. In 2012, the rate topped the Healthy People 2020 goal of 0.22 for the first time since 2008, according to Jason Vargo, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his associates.1

The explanation may be that the number of bicyclists has been steadily rising. “The share of total household trips taken by bicycle has doubled over the last 35 years,” with the largest share of that increase occurring in recent years. From 2000 to 2012, for example, “the number of US workers who traveled to work by bicycle increased 61%,” the researchers wrote.

The report was based on data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System, which limits fatalities to those involving a motor vehicle on a public road.2

Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

BY AMY KARON

FROM EMERGENCY MEDICINE JOURNAL

| A pair of large surgical bolt cutters were used to safely and quickly cut a titanium ring from a patient’s swollen finger, according to a letter published online in the Emergency Medicine Journal. |

“Our method used simple equipment that is readily available in most hospitals at all times, took less than 30 seconds to perform, and could be performed by a sole operator without damage to the underlying finger,” wrote Dr Andrej Salibi and Dr Andrew Morritt at Sheffield (England) Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation.1

Ring constriction is a fairly common problem that can cause necrosis and loss of the digit if the ring is not removed. Basic ring cutters can sever gold and silver, but not titanium, which has become popular for rings because it is hypoallergenic, durable, lightweight, and strong—so strong that diamond-tipped saws or drills can take up to 15 minutes to cut these rings. Many facilities also lack access to such equipment, and it generates enough heat that an assistant must irrigate the surrounding skin to prevent burns.

The case report described a patient who bathed in warm water at a spa and developed a painful, swollen finger that was constricted by a titanium wedding band. Elevation and lubrication at the ED failed to remove the ring, as did finger binding, and use of a manual ring cutter.

“The fire service was called and attempted removal using specialized cutting equipment, which also failed,” the surgeons wrote. “The patient was then admitted under the plastic surgery service for hand elevation, and further attempts 8 hours later blunted two manual ring cutters.” At this point, the surgeons borrowed a large pair of bolt cutters from the operating room, and quickly severed the ring without harming the finger. Then they applied lateral traction with a pair of paper clips and removed the split ring.

The authors declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Federal plan emphasizes heroin/opioid treatment over incarceration

BY WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

Frontline Medical News

| WASHINGTON—The Obama administration has announced that it will spend an additional $13.4 million fighting opioid and heroin abuse, emphasizing treatment over law enforcement. |

The increased emphasis will center on geographic areas where heroin and opioid abuse are rampant, specifically: Appalachia; New England; Philadelphia/Camden, New Jersey; metropolitan New York City, particularly northern New Jersey; and the Washington/Baltimore metropolitan region. Public safety officers and first responders will be trained in how to administer naloxone and provide other medical attention for those in the midst of a heroin or opioid overdose.

The 15 states in the targeted areas will share and leverage data to determine regional patterns of heroin and prescription painkiller-related overdose. These data are expected to delineate where the narcotics—especially those laced with other, more dangerous drugs—are being produced and distributed so that heroin response teams can disrupt the production and distribution of illegal drugs, and respond pre-emptively by expanding resources to communities hardest hit.

In a statement, Michael Botticelli, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said the administration’s emphasis on “the national drug challenge as both a public health and public safety issue” is based on viewing drug addiction as “a chronic disease of the brain that can be successfully prevented and treated, and from which one can recover.”

The initiative also will provide additional funding for similar efforts to address opioid abuse and methamphetamine abuse in the Southwest and along the United States/Mexico border.

“This program demonstrates the importance of linking health to criminal justice in collaboration rather than seeing better, new drug policy as a choice between health and law enforcement,” Dr Robert L. DuPont, former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, said in an interview.

Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

BY MIKE BOCK

Frontline Medical News

| An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings,1 The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement. |

Developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45 in a typical 200-bed hospital, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

- Creating awareness among staff

- Using a validated fall risk assessment tool

- Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program

- Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients

- Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year; and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Dr Lappin is an assistant professor and an attending physician, department of emergency medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Reference - CDC More bicyclists, more fatalities

- Vargo J, Gerhardstein BG, Whitfield GP, Wendel A. Bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicle traffic – United States, 1975-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(31):837-841.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). http://www.nhtsa.gov/FARS. Accessed August 20, 2015.

Reference - Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

- Salibi A, Morritt AN. Removing a titanium wedding ring [published online ahead of print August 13, 2015]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-204962.

Reference - Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. New! Targeted Solutions Tool for Preventing Falls. http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/tst_pfi.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2015.

More bicyclists, more fatalities

BY RICHARD FRANKI

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

| The annual rate for bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicles dropped 44% from 1975 to 2012, but the downward trend has slowed in recent years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. |

Annual mortality among cyclists for all motor vehicle-related deaths was 0.23 per 100,000 in 2012, a decline of 44% since 1975 when the rate was 0.41 per 100,000. But the rate is up from just under 0.20 per 100,000 in 2010. In 2012, the rate topped the Healthy People 2020 goal of 0.22 for the first time since 2008, according to Jason Vargo, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his associates.1

The explanation may be that the number of bicyclists has been steadily rising. “The share of total household trips taken by bicycle has doubled over the last 35 years,” with the largest share of that increase occurring in recent years. From 2000 to 2012, for example, “the number of US workers who traveled to work by bicycle increased 61%,” the researchers wrote.

The report was based on data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System, which limits fatalities to those involving a motor vehicle on a public road.2

Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

BY AMY KARON

FROM EMERGENCY MEDICINE JOURNAL

| A pair of large surgical bolt cutters were used to safely and quickly cut a titanium ring from a patient’s swollen finger, according to a letter published online in the Emergency Medicine Journal. |

“Our method used simple equipment that is readily available in most hospitals at all times, took less than 30 seconds to perform, and could be performed by a sole operator without damage to the underlying finger,” wrote Dr Andrej Salibi and Dr Andrew Morritt at Sheffield (England) Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation.1

Ring constriction is a fairly common problem that can cause necrosis and loss of the digit if the ring is not removed. Basic ring cutters can sever gold and silver, but not titanium, which has become popular for rings because it is hypoallergenic, durable, lightweight, and strong—so strong that diamond-tipped saws or drills can take up to 15 minutes to cut these rings. Many facilities also lack access to such equipment, and it generates enough heat that an assistant must irrigate the surrounding skin to prevent burns.

The case report described a patient who bathed in warm water at a spa and developed a painful, swollen finger that was constricted by a titanium wedding band. Elevation and lubrication at the ED failed to remove the ring, as did finger binding, and use of a manual ring cutter.

“The fire service was called and attempted removal using specialized cutting equipment, which also failed,” the surgeons wrote. “The patient was then admitted under the plastic surgery service for hand elevation, and further attempts 8 hours later blunted two manual ring cutters.” At this point, the surgeons borrowed a large pair of bolt cutters from the operating room, and quickly severed the ring without harming the finger. Then they applied lateral traction with a pair of paper clips and removed the split ring.

The authors declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Federal plan emphasizes heroin/opioid treatment over incarceration

BY WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

Frontline Medical News

| WASHINGTON—The Obama administration has announced that it will spend an additional $13.4 million fighting opioid and heroin abuse, emphasizing treatment over law enforcement. |

The increased emphasis will center on geographic areas where heroin and opioid abuse are rampant, specifically: Appalachia; New England; Philadelphia/Camden, New Jersey; metropolitan New York City, particularly northern New Jersey; and the Washington/Baltimore metropolitan region. Public safety officers and first responders will be trained in how to administer naloxone and provide other medical attention for those in the midst of a heroin or opioid overdose.

The 15 states in the targeted areas will share and leverage data to determine regional patterns of heroin and prescription painkiller-related overdose. These data are expected to delineate where the narcotics—especially those laced with other, more dangerous drugs—are being produced and distributed so that heroin response teams can disrupt the production and distribution of illegal drugs, and respond pre-emptively by expanding resources to communities hardest hit.

In a statement, Michael Botticelli, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said the administration’s emphasis on “the national drug challenge as both a public health and public safety issue” is based on viewing drug addiction as “a chronic disease of the brain that can be successfully prevented and treated, and from which one can recover.”

The initiative also will provide additional funding for similar efforts to address opioid abuse and methamphetamine abuse in the Southwest and along the United States/Mexico border.

“This program demonstrates the importance of linking health to criminal justice in collaboration rather than seeing better, new drug policy as a choice between health and law enforcement,” Dr Robert L. DuPont, former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, said in an interview.

Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

BY MIKE BOCK

Frontline Medical News

| An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings,1 The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement. |

Developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45 in a typical 200-bed hospital, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

- Creating awareness among staff

- Using a validated fall risk assessment tool

- Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program

- Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients

- Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year; and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Dr Lappin is an assistant professor and an attending physician, department of emergency medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

More bicyclists, more fatalities

BY RICHARD FRANKI

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

| The annual rate for bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicles dropped 44% from 1975 to 2012, but the downward trend has slowed in recent years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. |

Annual mortality among cyclists for all motor vehicle-related deaths was 0.23 per 100,000 in 2012, a decline of 44% since 1975 when the rate was 0.41 per 100,000. But the rate is up from just under 0.20 per 100,000 in 2010. In 2012, the rate topped the Healthy People 2020 goal of 0.22 for the first time since 2008, according to Jason Vargo, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his associates.1

The explanation may be that the number of bicyclists has been steadily rising. “The share of total household trips taken by bicycle has doubled over the last 35 years,” with the largest share of that increase occurring in recent years. From 2000 to 2012, for example, “the number of US workers who traveled to work by bicycle increased 61%,” the researchers wrote.

The report was based on data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System, which limits fatalities to those involving a motor vehicle on a public road.2

Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

BY AMY KARON

FROM EMERGENCY MEDICINE JOURNAL

| A pair of large surgical bolt cutters were used to safely and quickly cut a titanium ring from a patient’s swollen finger, according to a letter published online in the Emergency Medicine Journal. |

“Our method used simple equipment that is readily available in most hospitals at all times, took less than 30 seconds to perform, and could be performed by a sole operator without damage to the underlying finger,” wrote Dr Andrej Salibi and Dr Andrew Morritt at Sheffield (England) Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation.1

Ring constriction is a fairly common problem that can cause necrosis and loss of the digit if the ring is not removed. Basic ring cutters can sever gold and silver, but not titanium, which has become popular for rings because it is hypoallergenic, durable, lightweight, and strong—so strong that diamond-tipped saws or drills can take up to 15 minutes to cut these rings. Many facilities also lack access to such equipment, and it generates enough heat that an assistant must irrigate the surrounding skin to prevent burns.

The case report described a patient who bathed in warm water at a spa and developed a painful, swollen finger that was constricted by a titanium wedding band. Elevation and lubrication at the ED failed to remove the ring, as did finger binding, and use of a manual ring cutter.

“The fire service was called and attempted removal using specialized cutting equipment, which also failed,” the surgeons wrote. “The patient was then admitted under the plastic surgery service for hand elevation, and further attempts 8 hours later blunted two manual ring cutters.” At this point, the surgeons borrowed a large pair of bolt cutters from the operating room, and quickly severed the ring without harming the finger. Then they applied lateral traction with a pair of paper clips and removed the split ring.

The authors declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Federal plan emphasizes heroin/opioid treatment over incarceration

BY WHITNEY MCKNIGHT

Frontline Medical News

| WASHINGTON—The Obama administration has announced that it will spend an additional $13.4 million fighting opioid and heroin abuse, emphasizing treatment over law enforcement. |

The increased emphasis will center on geographic areas where heroin and opioid abuse are rampant, specifically: Appalachia; New England; Philadelphia/Camden, New Jersey; metropolitan New York City, particularly northern New Jersey; and the Washington/Baltimore metropolitan region. Public safety officers and first responders will be trained in how to administer naloxone and provide other medical attention for those in the midst of a heroin or opioid overdose.

The 15 states in the targeted areas will share and leverage data to determine regional patterns of heroin and prescription painkiller-related overdose. These data are expected to delineate where the narcotics—especially those laced with other, more dangerous drugs—are being produced and distributed so that heroin response teams can disrupt the production and distribution of illegal drugs, and respond pre-emptively by expanding resources to communities hardest hit.

In a statement, Michael Botticelli, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said the administration’s emphasis on “the national drug challenge as both a public health and public safety issue” is based on viewing drug addiction as “a chronic disease of the brain that can be successfully prevented and treated, and from which one can recover.”

The initiative also will provide additional funding for similar efforts to address opioid abuse and methamphetamine abuse in the Southwest and along the United States/Mexico border.

“This program demonstrates the importance of linking health to criminal justice in collaboration rather than seeing better, new drug policy as a choice between health and law enforcement,” Dr Robert L. DuPont, former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, said in an interview.

Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

BY MIKE BOCK

Frontline Medical News

| An online resource guide offers 21 targeted solutions for reducing the rate of falls in hospitals and urgent care settings,1 The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare announced in a statement. |

Developed in collaboration with seven hospitals and five health care organizations, the fall prevention methodology of the Targeted Solutions Tool could potentially reduce the number of patients injured from a fall from 117 to 45 in a typical 200-bed hospital, avoiding approximately $1 million in costs annually, the agency claims.

Some of the recommendations for reducing in-hospital falls include:

- Creating awareness among staff

- Using a validated fall risk assessment tool

- Engaging patients and their families in the fall safety program

- Hourly rounding with scheduled restroom use for patients

- Engaging all hospital staff and patients to ensure no patient walks without assistance

“Hundreds of thousands of patients fall in hospitals every year; and many of these falls result in moderate to severe injuries that can prolong hospital stays and require the patient to undergo additional treatment,” Dr Erin DuPree, vice president and chief medical officer of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, said in a statement.

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was created in 2008 as a nonprofit affiliate of The Joint Commission.

Dr Lappin is an assistant professor and an attending physician, department of emergency medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Reference - CDC More bicyclists, more fatalities

- Vargo J, Gerhardstein BG, Whitfield GP, Wendel A. Bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicle traffic – United States, 1975-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(31):837-841.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). http://www.nhtsa.gov/FARS. Accessed August 20, 2015.

Reference - Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

- Salibi A, Morritt AN. Removing a titanium wedding ring [published online ahead of print August 13, 2015]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-204962.

Reference - Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. New! Targeted Solutions Tool for Preventing Falls. http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/tst_pfi.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2015.

Reference - CDC More bicyclists, more fatalities

- Vargo J, Gerhardstein BG, Whitfield GP, Wendel A. Bicyclist deaths associated with motor vehicle traffic – United States, 1975-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2015;64(31):837-841.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). http://www.nhtsa.gov/FARS. Accessed August 20, 2015.

Reference - Surgical bolt cutters quickly cut titanium ring

- Salibi A, Morritt AN. Removing a titanium wedding ring [published online ahead of print August 13, 2015]. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-204962.

Reference - Online resource is aid for preventing patient falls

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. New! Targeted Solutions Tool for Preventing Falls. http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/tst_pfi.aspx. Accessed August 20, 2015.

FDA warns of disabling joint pain from DPP-4 inhibitors

Multiple reports of severe and disabling joint pain in some patients taking dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes have prompted the Food and Drug Administration to add a new warning and precaution for this class of drugs. Some cases were severe enough to require hospitalization, though symptoms eventually resolved after patients stopped taking the medication.

In a MedWatch Bulletin, the FDA advises that physicians should be alert for DPP-4 inhibitors as a causative factor for patients who present with severe, persistent joint pain, even for those who have been on the medication for some time.

Most patients developed symptoms within a month of beginning treatment; however, some patients had been on a DPP-4 inhibitor for as long as a year before the onset of joint pain. When the medication was stopped, arthralgia resolved within a month in all reported cases.

Of the 33 cases of severe arthralgia found in the FDA adverse events reporting database, 28 were associated with the use of sitagliptin (Januvia), with some cases also reported with saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), alogliptin (Nesina), and vildagliptin (Galvus). Ten patients’ symptoms were severe enough to require hospitalization; eight experienced recurrent arthralgia when rechallenged.

A literature search conducted by FDA officials revealed seven reports of DPP-4 inhibitor–associated arthralgia, two of which also were in their reporting database.

Patients taking DPP-4 inhibitors should continue taking their medication but consult their health care providers if they experience severe, persistent joint pain, according to the FDA advisory.

On Twitter @karioakes

Multiple reports of severe and disabling joint pain in some patients taking dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes have prompted the Food and Drug Administration to add a new warning and precaution for this class of drugs. Some cases were severe enough to require hospitalization, though symptoms eventually resolved after patients stopped taking the medication.

In a MedWatch Bulletin, the FDA advises that physicians should be alert for DPP-4 inhibitors as a causative factor for patients who present with severe, persistent joint pain, even for those who have been on the medication for some time.

Most patients developed symptoms within a month of beginning treatment; however, some patients had been on a DPP-4 inhibitor for as long as a year before the onset of joint pain. When the medication was stopped, arthralgia resolved within a month in all reported cases.

Of the 33 cases of severe arthralgia found in the FDA adverse events reporting database, 28 were associated with the use of sitagliptin (Januvia), with some cases also reported with saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), alogliptin (Nesina), and vildagliptin (Galvus). Ten patients’ symptoms were severe enough to require hospitalization; eight experienced recurrent arthralgia when rechallenged.

A literature search conducted by FDA officials revealed seven reports of DPP-4 inhibitor–associated arthralgia, two of which also were in their reporting database.

Patients taking DPP-4 inhibitors should continue taking their medication but consult their health care providers if they experience severe, persistent joint pain, according to the FDA advisory.

On Twitter @karioakes

Multiple reports of severe and disabling joint pain in some patients taking dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes have prompted the Food and Drug Administration to add a new warning and precaution for this class of drugs. Some cases were severe enough to require hospitalization, though symptoms eventually resolved after patients stopped taking the medication.

In a MedWatch Bulletin, the FDA advises that physicians should be alert for DPP-4 inhibitors as a causative factor for patients who present with severe, persistent joint pain, even for those who have been on the medication for some time.

Most patients developed symptoms within a month of beginning treatment; however, some patients had been on a DPP-4 inhibitor for as long as a year before the onset of joint pain. When the medication was stopped, arthralgia resolved within a month in all reported cases.

Of the 33 cases of severe arthralgia found in the FDA adverse events reporting database, 28 were associated with the use of sitagliptin (Januvia), with some cases also reported with saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), alogliptin (Nesina), and vildagliptin (Galvus). Ten patients’ symptoms were severe enough to require hospitalization; eight experienced recurrent arthralgia when rechallenged.

A literature search conducted by FDA officials revealed seven reports of DPP-4 inhibitor–associated arthralgia, two of which also were in their reporting database.

Patients taking DPP-4 inhibitors should continue taking their medication but consult their health care providers if they experience severe, persistent joint pain, according to the FDA advisory.

On Twitter @karioakes

Picato adverse events prompt FDA warning

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Drug Safety Communication warning for the potential for severe allergic reactions, shingles, and severe eye injuries from incorrect application of Picato (ingenol mebutate), a topical gel used to treat actinic keratosis.

Picato’s manufacurer, Leo Pharma Inc., will be required to change the drug’s labeling to reflect the risk for these adverse events and provide more information about safe application of Picato gel.

In the data summary accompanying the announcement, the FDA noted that some of the incorrect use of Picato gel was related either to inaccurate prescribing or dispensing. Adverse events reported were associated with incorrect application of Picato gel, which is to be used on no more than 25 cm2 of skin at a time, and for no more than 3 consecutive days.

Some of the adverse events reports describe mixing Picato with other products, occluding the skin after applying Picato gel, washing it off before the recommended 6 hours, or applying at bedtime.

Additionally, some adverse events occurred when the stronger 0.05% formulation, intended for use on the extremities and trunk, was applied to the face. Facial actinic keratoses are to be treated with the 0.015% formulation.

Adverse events described included severe allergic reactions ranging from significant contact dermatitis to anaphylaxis. Reactivation of herpes zoster was also reported; some of these cases were associated with applying Picato gel to a larger-than-recommended area, or with using an incorrect dose strength.

Another class of adverse events involved accidental transfer of Picato gel, often to the eyes. This occurred even after handwashing. In addition to eyelid swelling and irritation, cases of chemical conjunctivitis and corneal ulceration were reported. Lips, tongue, and rectum were other areas affected by accidental transfer of Picato gel.

On Twitter @karioakes

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Drug Safety Communication warning for the potential for severe allergic reactions, shingles, and severe eye injuries from incorrect application of Picato (ingenol mebutate), a topical gel used to treat actinic keratosis.

Picato’s manufacurer, Leo Pharma Inc., will be required to change the drug’s labeling to reflect the risk for these adverse events and provide more information about safe application of Picato gel.

In the data summary accompanying the announcement, the FDA noted that some of the incorrect use of Picato gel was related either to inaccurate prescribing or dispensing. Adverse events reported were associated with incorrect application of Picato gel, which is to be used on no more than 25 cm2 of skin at a time, and for no more than 3 consecutive days.

Some of the adverse events reports describe mixing Picato with other products, occluding the skin after applying Picato gel, washing it off before the recommended 6 hours, or applying at bedtime.

Additionally, some adverse events occurred when the stronger 0.05% formulation, intended for use on the extremities and trunk, was applied to the face. Facial actinic keratoses are to be treated with the 0.015% formulation.

Adverse events described included severe allergic reactions ranging from significant contact dermatitis to anaphylaxis. Reactivation of herpes zoster was also reported; some of these cases were associated with applying Picato gel to a larger-than-recommended area, or with using an incorrect dose strength.

Another class of adverse events involved accidental transfer of Picato gel, often to the eyes. This occurred even after handwashing. In addition to eyelid swelling and irritation, cases of chemical conjunctivitis and corneal ulceration were reported. Lips, tongue, and rectum were other areas affected by accidental transfer of Picato gel.

On Twitter @karioakes

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Drug Safety Communication warning for the potential for severe allergic reactions, shingles, and severe eye injuries from incorrect application of Picato (ingenol mebutate), a topical gel used to treat actinic keratosis.

Picato’s manufacurer, Leo Pharma Inc., will be required to change the drug’s labeling to reflect the risk for these adverse events and provide more information about safe application of Picato gel.

In the data summary accompanying the announcement, the FDA noted that some of the incorrect use of Picato gel was related either to inaccurate prescribing or dispensing. Adverse events reported were associated with incorrect application of Picato gel, which is to be used on no more than 25 cm2 of skin at a time, and for no more than 3 consecutive days.

Some of the adverse events reports describe mixing Picato with other products, occluding the skin after applying Picato gel, washing it off before the recommended 6 hours, or applying at bedtime.

Additionally, some adverse events occurred when the stronger 0.05% formulation, intended for use on the extremities and trunk, was applied to the face. Facial actinic keratoses are to be treated with the 0.015% formulation.

Adverse events described included severe allergic reactions ranging from significant contact dermatitis to anaphylaxis. Reactivation of herpes zoster was also reported; some of these cases were associated with applying Picato gel to a larger-than-recommended area, or with using an incorrect dose strength.

Another class of adverse events involved accidental transfer of Picato gel, often to the eyes. This occurred even after handwashing. In addition to eyelid swelling and irritation, cases of chemical conjunctivitis and corneal ulceration were reported. Lips, tongue, and rectum were other areas affected by accidental transfer of Picato gel.

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM AN FDA MEDWATCH ALERT

Case Studies in Toxicology: Managing Missed Methadone

A 53-year-old woman presented to the ED after experiencing a fall. Her medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis, and a remote history of intravenous drug use, for which she had been maintained on methadone for the past 20 years. She reported that she had suffered several “fainting episodes” over the past month, and the morning prior to arrival, had sustained what she thought was a mechanical fall outside of the methadone program she attended. She complained of tenderness on her head but denied any other injuries.

The methadone program had referred the patient to the ED for evaluation, noting to the ED staff that her daily methadone dose of 185 mg had not been dispensed prior to transfer. During evaluation, the patient requested that the emergency physician (EP) provide the methadone dose since the clinic would close prior to her discharge from the ED.

How can requests for methadone be managed in the ED?

Methadone is a long-acting oral opioid that is used for both opioid replacement therapy and pain management. When used to reduce craving in opioid-dependent patients, methadone is administered daily through federally sanctioned methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs. Patients who consistently adhere to the required guidelines are given “take home” doses. When used for pain management, methadone is typically administered several times daily and may be prescribed by any provider with an appropriate DEA registration.

When given for MMT, methadone saturates the µ-opioid receptors and hinders their binding and agonism by other opioids such as heroin or oxycodone. Patients in MMT programs are started on a low initial dose and slowly titrated upward as tolerance to the adverse effects (eg, sedation) develop.

How are symptomatic patients with methadone withdrawal treated?

Most methadone programs have limited hours and require that patients who miss a dose wait until the following day to return to the program. This is typically without medical consequence because the high dose dispensed by these programs maintains a therapeutic blood concentration for far longer than the expected delay. Although the half-life of methadone exhibits wide interindividual variability, it generally ranges from 12 hours to more than 40 hours.1 Regardless, patients may feel anxious about potential opioid withdrawal, and this often leads them to access the ED for a missed dose.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms attending withdrawal may precede the objective signs of opioid withdrawal. Patients with objective signs of opioid withdrawal (eg, piloerection, vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils) may be sufficiently treated with supportive care alone, using antiemetics, hydration, and sometimes clonidine.

Administration of substitute opioids is problematic due to the patient’s underlying tolerance necessitating careful dose titration. Therefore, direct replacement of methadone in the ED remains controversial, and some EDs have strict policies prohibiting the administration of methadone to patients who have missed an MMT dose. Such policies, which are intended to discourage patients from using the ED as a convenience, may be appropriate given the generally benign—though uncomfortable—course of opioid withdrawal due to abstinence.

Other EDs provide replacement methadone for asymptomatic, treat-and-release patients confirmed to be enrolled in an MMT program when the time to the next dose is likely to be 24 hours or greater from the missed dose. Typically, a dose of no more than 10 mg orally or 10 mg intramuscularly (IM) is recommended, and patients should be advised that they will be receiving only a low dose to sufficient to prevent withdrawal—one that may not have the equivalent effects of the outpatient dose.

Whenever possible, a patient’s MMT program should be contacted and informed of the ED visit. For patients who display objective signs of withdrawal and who cannot be confirmed or who do not participate in an MMT program, 10 mg of methadone IM will prevent uncertainty of drug absorption in the setting of nausea or vomiting. All patients receiving oral methadone should be observed for 1 hour, and those receiving IM methadone should be observed for at least 90 minutes to assess for unexpected sedation.2

Patients encountering circumstances that prevent opioid access (eg, incarceration) and who are not in withdrawal but have gone without opioids for more than 5 days may have a loss of tolerance to their usual doses—whether the medication was obtained through an MMT program or illicitly. Harm-reduction strategies aimed at educating patients on the potential vulnerability to their familiar dosing regimens are warranted to avert inadvertent overdoses in chronic opioid users who are likely to resume illicit opoiod use.

Does this patient need syncope evaluation?

Further complicating the decision regarding ED dispensing of methadone are the effects of the drug on myocardial repolarization. Methadone affects conduction across the hERG potassium rectifier current and can prolong the QTc interval on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), predisposing a patient to torsade de pointes (TdP). Although there is controversy regarding the role of ECG screening during the enrollment of patients in methadone maintenance clinics, doses above 60 mg, underlying myocardial disease, female sex, and electrolyte disturbances may increase the risk of QT prolongation and TdP.3

Whether there is value in obtaining a screening ECG in a patient receiving an initial dose of methadone in the ED is unclear, and this practice is controversial even among methadone clinics. However, some of the excess death in patients taking methadone may be explained by the dysrhythmogenic potential of methadone.4 An ECG therefore may elucidate a correctable cause in methadone patients presenting with syncope.

Administering methadone to patients with documented QT prolongation must weigh the risk of methadone’s conduction effects against the substantial risks of illicit opioid self-administration. For some patients at-risk for TdP, it may be preferable to use buprenorphine if possible, since it does not carry the same cardiac effects as methadone.1,5 Such therapy requires referral to a physician licensed to prescribe this medication.

How should admitted patients be managed?

While administration of methadone for withdrawal or maintenance therapy in the ED is acceptable, outpatient prescribing of methadone for these reasons is not legal, and only federally regulated clinics may engage in this practice. Hospitalized patients who are enrolled in an MMT program should have their daily methadone dose confirmed and continued—as long as the patient has not lost tolerance. Patients not participating in an MMT program can receive up to 3 days of methadone in the hospital, even if the practitioner is not registered to provide methadone.6 For these patients, it is recommended that the physician order a low dose of methadone and also consult with an addiction specialist to determine whether the patient should continue on MMT maintenance or undergo detoxification.

It is important to note that methadone may be prescribed for pain, but its use in the ED for this purpose is strongly discouraged, especially in patients who have never received methadone previously. For admitted patients requiring such potent opioid analgesia, consultation with a pain service or, when indicated, a palliative care/hospice specialist is warranted as the dosing intervals are different in each setting, and the risk of respiratory depression is high.

Case Conclusion

As requested by the MMT clinic, the patient was administered methadone 185 mg orally in the ED, though a dose of 10 mg would have been sufficient to prevent withdrawal. Unfortunately, the EP did not appreciate the relationship of the markedly prolonged QTc and the methadone, which should have prompted a dose reduction.

Evaluation of the patient’s electrolyte levels, which included magnesium and potassium, were normal. An ECG was repeated 24 hours later and revealed a persistent, but improved, QT interval at 505 ms. The remainder of the syncope workup was negative. Because the patient had no additional symptoms or events during her stay, she was discharged. At discharge, the EP followed up with the MMT clinic to discuss lowering the patient’s daily methadone dose, as well as close cardiology follow-up.

Dr Rao is the chief of the division of medical toxicology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Chou R, Weimer MB, Dana T. Methadone overdose and cardiac arrhythmia potential: findings from a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and College on Problems of Drug Dependence clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2014;15(4):338-365.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Web site. Methadone. http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/research/job185drugs/methadone.htm. Accessed August 3, 2015.

- Martin JA, Campbell A, Killip T, et al; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. QT interval screening in methadone maintenance treatment: report of a SAMHSA expert panel. J Addict Dis. 2011;30(4):283-306. Erratum in: J Addict Dis. 2012;31(1):91.

- Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Cooper WO, Hall K, Stein CM. Out-of-hospital mortality among patients receiving methadone for noncancer pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):420-427.

- Davis MP. Twelve reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic in the management of pain. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(6):209-219.

- US Government Printing Office. Federal Digital System. Administering or dispensing of narcotic drugs. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 CFR §1306.07. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-1998-title21-vol9/pdf/CFR-1998-title21-vol9-sec1306-07.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2015.

A 53-year-old woman presented to the ED after experiencing a fall. Her medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis, and a remote history of intravenous drug use, for which she had been maintained on methadone for the past 20 years. She reported that she had suffered several “fainting episodes” over the past month, and the morning prior to arrival, had sustained what she thought was a mechanical fall outside of the methadone program she attended. She complained of tenderness on her head but denied any other injuries.

The methadone program had referred the patient to the ED for evaluation, noting to the ED staff that her daily methadone dose of 185 mg had not been dispensed prior to transfer. During evaluation, the patient requested that the emergency physician (EP) provide the methadone dose since the clinic would close prior to her discharge from the ED.

How can requests for methadone be managed in the ED?

Methadone is a long-acting oral opioid that is used for both opioid replacement therapy and pain management. When used to reduce craving in opioid-dependent patients, methadone is administered daily through federally sanctioned methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs. Patients who consistently adhere to the required guidelines are given “take home” doses. When used for pain management, methadone is typically administered several times daily and may be prescribed by any provider with an appropriate DEA registration.

When given for MMT, methadone saturates the µ-opioid receptors and hinders their binding and agonism by other opioids such as heroin or oxycodone. Patients in MMT programs are started on a low initial dose and slowly titrated upward as tolerance to the adverse effects (eg, sedation) develop.

How are symptomatic patients with methadone withdrawal treated?

Most methadone programs have limited hours and require that patients who miss a dose wait until the following day to return to the program. This is typically without medical consequence because the high dose dispensed by these programs maintains a therapeutic blood concentration for far longer than the expected delay. Although the half-life of methadone exhibits wide interindividual variability, it generally ranges from 12 hours to more than 40 hours.1 Regardless, patients may feel anxious about potential opioid withdrawal, and this often leads them to access the ED for a missed dose.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms attending withdrawal may precede the objective signs of opioid withdrawal. Patients with objective signs of opioid withdrawal (eg, piloerection, vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils) may be sufficiently treated with supportive care alone, using antiemetics, hydration, and sometimes clonidine.

Administration of substitute opioids is problematic due to the patient’s underlying tolerance necessitating careful dose titration. Therefore, direct replacement of methadone in the ED remains controversial, and some EDs have strict policies prohibiting the administration of methadone to patients who have missed an MMT dose. Such policies, which are intended to discourage patients from using the ED as a convenience, may be appropriate given the generally benign—though uncomfortable—course of opioid withdrawal due to abstinence.

Other EDs provide replacement methadone for asymptomatic, treat-and-release patients confirmed to be enrolled in an MMT program when the time to the next dose is likely to be 24 hours or greater from the missed dose. Typically, a dose of no more than 10 mg orally or 10 mg intramuscularly (IM) is recommended, and patients should be advised that they will be receiving only a low dose to sufficient to prevent withdrawal—one that may not have the equivalent effects of the outpatient dose.

Whenever possible, a patient’s MMT program should be contacted and informed of the ED visit. For patients who display objective signs of withdrawal and who cannot be confirmed or who do not participate in an MMT program, 10 mg of methadone IM will prevent uncertainty of drug absorption in the setting of nausea or vomiting. All patients receiving oral methadone should be observed for 1 hour, and those receiving IM methadone should be observed for at least 90 minutes to assess for unexpected sedation.2

Patients encountering circumstances that prevent opioid access (eg, incarceration) and who are not in withdrawal but have gone without opioids for more than 5 days may have a loss of tolerance to their usual doses—whether the medication was obtained through an MMT program or illicitly. Harm-reduction strategies aimed at educating patients on the potential vulnerability to their familiar dosing regimens are warranted to avert inadvertent overdoses in chronic opioid users who are likely to resume illicit opoiod use.

Does this patient need syncope evaluation?

Further complicating the decision regarding ED dispensing of methadone are the effects of the drug on myocardial repolarization. Methadone affects conduction across the hERG potassium rectifier current and can prolong the QTc interval on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), predisposing a patient to torsade de pointes (TdP). Although there is controversy regarding the role of ECG screening during the enrollment of patients in methadone maintenance clinics, doses above 60 mg, underlying myocardial disease, female sex, and electrolyte disturbances may increase the risk of QT prolongation and TdP.3

Whether there is value in obtaining a screening ECG in a patient receiving an initial dose of methadone in the ED is unclear, and this practice is controversial even among methadone clinics. However, some of the excess death in patients taking methadone may be explained by the dysrhythmogenic potential of methadone.4 An ECG therefore may elucidate a correctable cause in methadone patients presenting with syncope.

Administering methadone to patients with documented QT prolongation must weigh the risk of methadone’s conduction effects against the substantial risks of illicit opioid self-administration. For some patients at-risk for TdP, it may be preferable to use buprenorphine if possible, since it does not carry the same cardiac effects as methadone.1,5 Such therapy requires referral to a physician licensed to prescribe this medication.

How should admitted patients be managed?

While administration of methadone for withdrawal or maintenance therapy in the ED is acceptable, outpatient prescribing of methadone for these reasons is not legal, and only federally regulated clinics may engage in this practice. Hospitalized patients who are enrolled in an MMT program should have their daily methadone dose confirmed and continued—as long as the patient has not lost tolerance. Patients not participating in an MMT program can receive up to 3 days of methadone in the hospital, even if the practitioner is not registered to provide methadone.6 For these patients, it is recommended that the physician order a low dose of methadone and also consult with an addiction specialist to determine whether the patient should continue on MMT maintenance or undergo detoxification.

It is important to note that methadone may be prescribed for pain, but its use in the ED for this purpose is strongly discouraged, especially in patients who have never received methadone previously. For admitted patients requiring such potent opioid analgesia, consultation with a pain service or, when indicated, a palliative care/hospice specialist is warranted as the dosing intervals are different in each setting, and the risk of respiratory depression is high.

Case Conclusion

As requested by the MMT clinic, the patient was administered methadone 185 mg orally in the ED, though a dose of 10 mg would have been sufficient to prevent withdrawal. Unfortunately, the EP did not appreciate the relationship of the markedly prolonged QTc and the methadone, which should have prompted a dose reduction.

Evaluation of the patient’s electrolyte levels, which included magnesium and potassium, were normal. An ECG was repeated 24 hours later and revealed a persistent, but improved, QT interval at 505 ms. The remainder of the syncope workup was negative. Because the patient had no additional symptoms or events during her stay, she was discharged. At discharge, the EP followed up with the MMT clinic to discuss lowering the patient’s daily methadone dose, as well as close cardiology follow-up.

Dr Rao is the chief of the division of medical toxicology at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

A 53-year-old woman presented to the ED after experiencing a fall. Her medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis, and a remote history of intravenous drug use, for which she had been maintained on methadone for the past 20 years. She reported that she had suffered several “fainting episodes” over the past month, and the morning prior to arrival, had sustained what she thought was a mechanical fall outside of the methadone program she attended. She complained of tenderness on her head but denied any other injuries.

The methadone program had referred the patient to the ED for evaluation, noting to the ED staff that her daily methadone dose of 185 mg had not been dispensed prior to transfer. During evaluation, the patient requested that the emergency physician (EP) provide the methadone dose since the clinic would close prior to her discharge from the ED.

How can requests for methadone be managed in the ED?

Methadone is a long-acting oral opioid that is used for both opioid replacement therapy and pain management. When used to reduce craving in opioid-dependent patients, methadone is administered daily through federally sanctioned methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs. Patients who consistently adhere to the required guidelines are given “take home” doses. When used for pain management, methadone is typically administered several times daily and may be prescribed by any provider with an appropriate DEA registration.

When given for MMT, methadone saturates the µ-opioid receptors and hinders their binding and agonism by other opioids such as heroin or oxycodone. Patients in MMT programs are started on a low initial dose and slowly titrated upward as tolerance to the adverse effects (eg, sedation) develop.

How are symptomatic patients with methadone withdrawal treated?

Most methadone programs have limited hours and require that patients who miss a dose wait until the following day to return to the program. This is typically without medical consequence because the high dose dispensed by these programs maintains a therapeutic blood concentration for far longer than the expected delay. Although the half-life of methadone exhibits wide interindividual variability, it generally ranges from 12 hours to more than 40 hours.1 Regardless, patients may feel anxious about potential opioid withdrawal, and this often leads them to access the ED for a missed dose.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms attending withdrawal may precede the objective signs of opioid withdrawal. Patients with objective signs of opioid withdrawal (eg, piloerection, vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils) may be sufficiently treated with supportive care alone, using antiemetics, hydration, and sometimes clonidine.

Administration of substitute opioids is problematic due to the patient’s underlying tolerance necessitating careful dose titration. Therefore, direct replacement of methadone in the ED remains controversial, and some EDs have strict policies prohibiting the administration of methadone to patients who have missed an MMT dose. Such policies, which are intended to discourage patients from using the ED as a convenience, may be appropriate given the generally benign—though uncomfortable—course of opioid withdrawal due to abstinence.

Other EDs provide replacement methadone for asymptomatic, treat-and-release patients confirmed to be enrolled in an MMT program when the time to the next dose is likely to be 24 hours or greater from the missed dose. Typically, a dose of no more than 10 mg orally or 10 mg intramuscularly (IM) is recommended, and patients should be advised that they will be receiving only a low dose to sufficient to prevent withdrawal—one that may not have the equivalent effects of the outpatient dose.

Whenever possible, a patient’s MMT program should be contacted and informed of the ED visit. For patients who display objective signs of withdrawal and who cannot be confirmed or who do not participate in an MMT program, 10 mg of methadone IM will prevent uncertainty of drug absorption in the setting of nausea or vomiting. All patients receiving oral methadone should be observed for 1 hour, and those receiving IM methadone should be observed for at least 90 minutes to assess for unexpected sedation.2

Patients encountering circumstances that prevent opioid access (eg, incarceration) and who are not in withdrawal but have gone without opioids for more than 5 days may have a loss of tolerance to their usual doses—whether the medication was obtained through an MMT program or illicitly. Harm-reduction strategies aimed at educating patients on the potential vulnerability to their familiar dosing regimens are warranted to avert inadvertent overdoses in chronic opioid users who are likely to resume illicit opoiod use.

Does this patient need syncope evaluation?

Further complicating the decision regarding ED dispensing of methadone are the effects of the drug on myocardial repolarization. Methadone affects conduction across the hERG potassium rectifier current and can prolong the QTc interval on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), predisposing a patient to torsade de pointes (TdP). Although there is controversy regarding the role of ECG screening during the enrollment of patients in methadone maintenance clinics, doses above 60 mg, underlying myocardial disease, female sex, and electrolyte disturbances may increase the risk of QT prolongation and TdP.3