User login

CDC investigating accidental anthrax shipment to labs

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating a shipment of anthrax mistakenly sent to labs in the United States and abroad from the Department of Defense, the agency said in a May 30 announcement.

The presence of anthrax was confirmed after a laboratory working with the DOD reported being able to grow live Bacillus anthracis bacteria, although an inactive agent was expected. The lab was working with the DOD to develop a diagnostic test to identify biological threats, the CDC reported.

The accidental shipment is not believed to pose a risk to the public, the CDC said. Samples are being sent to the CDC or Laboratory Response Network labs for testing, and CDC officials are performing onsite investigations at the laboratories involved.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating a shipment of anthrax mistakenly sent to labs in the United States and abroad from the Department of Defense, the agency said in a May 30 announcement.

The presence of anthrax was confirmed after a laboratory working with the DOD reported being able to grow live Bacillus anthracis bacteria, although an inactive agent was expected. The lab was working with the DOD to develop a diagnostic test to identify biological threats, the CDC reported.

The accidental shipment is not believed to pose a risk to the public, the CDC said. Samples are being sent to the CDC or Laboratory Response Network labs for testing, and CDC officials are performing onsite investigations at the laboratories involved.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is investigating a shipment of anthrax mistakenly sent to labs in the United States and abroad from the Department of Defense, the agency said in a May 30 announcement.

The presence of anthrax was confirmed after a laboratory working with the DOD reported being able to grow live Bacillus anthracis bacteria, although an inactive agent was expected. The lab was working with the DOD to develop a diagnostic test to identify biological threats, the CDC reported.

The accidental shipment is not believed to pose a risk to the public, the CDC said. Samples are being sent to the CDC or Laboratory Response Network labs for testing, and CDC officials are performing onsite investigations at the laboratories involved.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Babies and Booze—Pediatric Considerations in the Management of Ethanol Intoxication

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

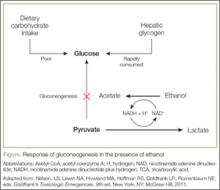

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Case

A previously healthy 4-month-old girl was brought into the ED for concerns of alcohol ingestion. Reportedly, the infant’s father reconstituted 4 ounces of powdered formula using what he thought was water from an unmarked bottle in his refrigerator. He later realized that the bottle contained rum, although he still let the child finish the 4 ounces of formula in the hopes that she would vomit—which did not occur.

Upon arrival to the ED, the infant’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 100/61 mm Hg; heart rate, 155 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 36 breaths/minute; and temperature, normal. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. A rapid bedside blood glucose test was 89 mg/dL. The infant’s physical examination was unremarkable. She appeared active but hungry, had a strong cry, and had a developmentally appropriate gross neurological examination.

How does ethanol exposure in children typically occur?

Recent reports from the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System demonstrate that ethanol exposures comprise 1% to 3% of total exposures in children aged ≤5 years.

The most common sources are ethanol-containing beverages, mouthwash, and cologne/perfume.1 Ethanol can also be found as a solvent for certain pediatric liquid medications (eg, ranitidine) or in flavor extracts (eg, vanilla extract, orange extract). Any clear alcohol (eg, vodka, gin, rum) stored in an accessible site, such as a refrigerator, may be mistaken for water. In many reports, a caregiver unintentionally used the alcohol to reconstitute formula; however, intentional provision of alcohol to toddlers, usually as a sedative, is a recurring concern.2

What are the clinical concerns in children with ethanol intoxication?

Under usual conditions, a normal serum glucose concentration is maintained from ingested carbohydrates and via glycogenolysis of hepatic glycogen stores. Such glycogen reserves can sustain normal blood glucose concentrations for several hours in adults but for a shorter period in children. Once glycogen is depleted, as is common after an overnight fast, glucose can be generated through gluconeogenesis.

However, in the presence of ethanol (Figure), the excessive reducing potential (ie, NADH) that results from ethanol metabolism shunts pyruvate away from the gluconeogenic pathway (toward lactate), inhibiting glucose production. Unlike adults, children and infants, who have relatively low glycogen reserves, are at significant risk for hypoglycemia following ethanol exposure. This represents the largest contributor to morbidity and mortality of children with ethanol intoxication.3 Patients with hypoglycemia can have a highly variable clinical presentation including agitation, seizures, focality, or coma.4

Case Continuation

Intravenous (IV) access was obtained, and the patient was placed on a dextrose-containing fluid at 1.5 times the maintenance flow rate. Pertinent laboratory studies revealed a serum glucose level of 90 mg/dL, normal electrolyte panel, and an initial blood alcohol concentration of 337 mg/dL (approximately 30 minutes postingestion).

How do children with ethanol intoxication present?

While there is some variation in clinical effects among nontolerant adults, acute ethanol intoxication with a serum concentration >250 mg/dL is frequently associated with stupor, respiratory depression, and hypotension. A concentration >400 mg/dL may be associated with coma or apnea. Although similar clinical effects are expected in adolescents and children, infants often have counterintuitive clinical findings.

To date, eight cases of significant infant ethanol exposure exist in the literature (age range, 29 days to 9 months; ethanol concentration, 183-524 mg/dL). Respiratory depression was absent in all cases.5-9 In all but two cases, the neurological examination revealed only subtle decreases in interaction or tone. The remaining two children were described as obtunded and flaccid (ethanol levels, 405 mg/dL and 524 mg/dL, respectively) and were intubated for airway protection despite normal respiratory rates.7,10

The incongruence between the clinical findings (both the neurological examination and respiratory effects) and the ethanol concentration is difficult to explain. It may be due to age-related neurological immaturity or a limited ability to perform the required detailed neurological examinations in children. In particular, the relatively preserved level of consciousness, despite an otherwise coma-inducing ethanol concentration, is unique to infants. Accordingly, there should be a low threshold to check ethanol concentrations in infants presenting with apparent life-threatening events, altered mental status, decreased tone, or unexplained hypoglycemia or hypothermia.

What is the estimated time to sobriety in infants?

Ethanol is eliminated via a hepatic enzymatic oxidation pathway that becomes saturated at low serum levels. In nontolerant adults, this results in a zero-order kinetic elimination pattern with an ethanol elimination rate of approximately 20 mg/dL per hour. Anecdotally, it had been thought that children clear ethanol at roughly double this rate via unclear mechanisms. However, a review of published kinetic data suggests the actual rate of clearance may not differ substantially from adults (range, 19-34 mg/dL per hour).5-7,10,11

Case Conclusion

The patient was transferred to a tertiary care pediatric hospital for continued management, where the markedly elevated serum ethanol concentration was confirmed. She was maintained on a dextrose-containing IV fluid and observed overnight without development of any complications. Serial serum ethanol concentrations were performed and complete clearance was achieved approximately 20 hours postingestion, suggesting a metabolic rate of 16 mg/dL per hour. The infant was discharged home with supervision by child protective services.

Dr Boroughf is a toxicology fellow, department of emergency medicine, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Henretig is an attending toxicologist, department of emergency medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.

- Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(10):949-1229.

- Wood JN, Pecker LH, Russo ME, Henretig F, Christian CW. Evaluation and referral for child maltreatment in pediatric poisoning victims. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(4):362-369.

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(1):5-12.

- Malouf R, Brust JC. Hypoglycemia: causes, neurological manifestations, and outcome. Ann Neurol.1985;17(5):421-430.

- Chikava K, Lower DR, Frangiskakis SH, Sepulveda JL, Virji MA, Rao KN. Acute ethanol intoxication in a 7-month old-infant. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7(4):400-402.

- Ford JB, Wayment MT, Albertson TE, Owen KP, Radke JB, Sutter ME. Elimination kinetics of ethanol in a 5-week-old infant and a literature review of infant ethanol pharmacokinetics. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:250716. doi:10.1155/2013/250716

- McCormick T, Levine M, Knox O, Claudius I. Ethanol ingestion in two infants under 2 months old: a previously unreported cause of ALTE. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2);e604-e607.

- Fong HF, Muller AA. An unexpected clinical course in a 29-day-old infant with ethanol exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):111-113.

- Iyer SS, Haupt A, Henretig FM. Pick your poison: straight from the spring? Ped Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):194-196.

- Edmunds SM, Ajizian SJ, Liguori A. Acute obtundation in a 9-month-old patient: ethanol ingestion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(10):739-741.

- Simon HK, Cox JM, Sucov A, Linakis JG. Serum ethanol clearance in intoxicated children and adolescents presenting to the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(6):520-524.

HCV spike in four Appalachian states tied to drug abuse

Acute hepatitis C virus infections more than tripled among young people in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia between 2006 and 2012, investigators reported online May 8 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increase in acute HCV infections in central Appalachia is highly correlated with the region’s epidemic of prescription opioid abuse and facilitated by an upsurge in the number of persons who inject drugs,” said Dr. Jon Zibbell at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his associates.

Nationally, acute HCV infections have risen most steeply in states east of the Mississippi. To further explore the trend, the researchers examined HCV case data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, and data on 217,789 admissions to substance abuse treatment centers related to opioid or injection drug abuse (MMWR 2015;64:453-8).

Confirmed HCV cases among individuals aged 30 years and younger rose by 364% in the four Appalachian states during 2006-2012, the investigators found. “The increasing incidence among nonurban residents was at least double that of urban residents each year,” they said. Among patients with known risk factors for HCV infection, 73% reported injection drug use.

During the same time, treatment admissions for opioid dependency among individuals aged 12-29 years rose by 21% in the four states, and self-reported injection drug use rose by more than 12%, the researchers said. “Evidence-based strategies as well as integrated-service provision are urgently needed in drug treatment programs to ensure patients are tested for HCV, and persons found to be HCV infected are linked to care and receive appropriate treatment,” they concluded. “These efforts will require further collaboration among federal partners and state and local health departments to better address the syndemic of opioid abuse and HCV infection.”

The investigators declared no funding sources or financial conflicts of interest.

Acute hepatitis C virus infections more than tripled among young people in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia between 2006 and 2012, investigators reported online May 8 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increase in acute HCV infections in central Appalachia is highly correlated with the region’s epidemic of prescription opioid abuse and facilitated by an upsurge in the number of persons who inject drugs,” said Dr. Jon Zibbell at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his associates.

Nationally, acute HCV infections have risen most steeply in states east of the Mississippi. To further explore the trend, the researchers examined HCV case data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, and data on 217,789 admissions to substance abuse treatment centers related to opioid or injection drug abuse (MMWR 2015;64:453-8).

Confirmed HCV cases among individuals aged 30 years and younger rose by 364% in the four Appalachian states during 2006-2012, the investigators found. “The increasing incidence among nonurban residents was at least double that of urban residents each year,” they said. Among patients with known risk factors for HCV infection, 73% reported injection drug use.

During the same time, treatment admissions for opioid dependency among individuals aged 12-29 years rose by 21% in the four states, and self-reported injection drug use rose by more than 12%, the researchers said. “Evidence-based strategies as well as integrated-service provision are urgently needed in drug treatment programs to ensure patients are tested for HCV, and persons found to be HCV infected are linked to care and receive appropriate treatment,” they concluded. “These efforts will require further collaboration among federal partners and state and local health departments to better address the syndemic of opioid abuse and HCV infection.”

The investigators declared no funding sources or financial conflicts of interest.

Acute hepatitis C virus infections more than tripled among young people in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia between 2006 and 2012, investigators reported online May 8 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increase in acute HCV infections in central Appalachia is highly correlated with the region’s epidemic of prescription opioid abuse and facilitated by an upsurge in the number of persons who inject drugs,” said Dr. Jon Zibbell at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his associates.

Nationally, acute HCV infections have risen most steeply in states east of the Mississippi. To further explore the trend, the researchers examined HCV case data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, and data on 217,789 admissions to substance abuse treatment centers related to opioid or injection drug abuse (MMWR 2015;64:453-8).

Confirmed HCV cases among individuals aged 30 years and younger rose by 364% in the four Appalachian states during 2006-2012, the investigators found. “The increasing incidence among nonurban residents was at least double that of urban residents each year,” they said. Among patients with known risk factors for HCV infection, 73% reported injection drug use.

During the same time, treatment admissions for opioid dependency among individuals aged 12-29 years rose by 21% in the four states, and self-reported injection drug use rose by more than 12%, the researchers said. “Evidence-based strategies as well as integrated-service provision are urgently needed in drug treatment programs to ensure patients are tested for HCV, and persons found to be HCV infected are linked to care and receive appropriate treatment,” they concluded. “These efforts will require further collaboration among federal partners and state and local health departments to better address the syndemic of opioid abuse and HCV infection.”

The investigators declared no funding sources or financial conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Hepatitis C virus infections more than tripled among young people in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, and were strongly tied to rises in opioid and injection drug abuse.

Major finding: From 2006 to 2012, the number of acute HCV infections increased by 364% among individuals aged 30 years or less.

Data source: Analysis of HCV case data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System and of substance abuse admissions data from the Treatment Episode Data Set.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no funding sources or financial conflicts of interest.

Mind the Gap: Case Study in Toxicology

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

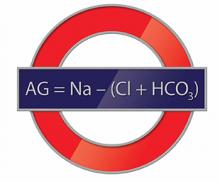

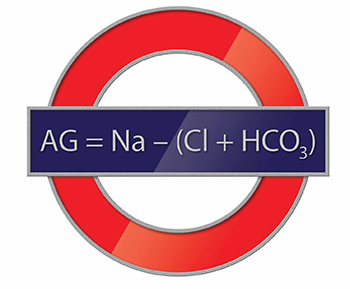

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Malpractice Counsel

Sepsis Following Vaginal Hysterectomy

| A 45-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of lower abdominal pain, which she described as gradual, aching, and intermittent. The patient stated that she had undergone a vaginal hysterectomy a few days prior and that the pain started less than 24 hours after discharge from the hospital. She denied fever or chills, nausea, or vomiting, and said that she had a bowel movement earlier that day. She also denied any urinary symptoms. Her medical history was significant only for hypothyroidism, for which she was taking levothyroxine. The patient denied cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption. She said she had been taking acetaminophen-hydrocodone for postoperative pain, but that it did not provide any relief. |

The patient’s vital signs were: temperature, 98.6˚F; blood pressure, 112/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 98 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal, as were the heart and lung examinations. The patient’s abdomen was soft, with mild diffuse lower abdominal tenderness. There was no guarding, rebound, or mass present. A gross nonspeculum examination of the vaginal area did not reveal any discharge or erythema; a rectal examination was not performed.

The EP ordered a complete blood count (CBC), lipase evaluation, and urinalysis. All test results were normal. The emergency physician (EP) then contacted the obstetrician-gynecologist (OB/GYN) who had performed the hysterectomy. The OB/GYN recommended the EP change the analgesic agent to acetaminophen-oxycodone and to encourage the patient to keep her follow-up postoperative appointment in 1 week. The EP followed these instructions and discharged the patient home with a prescription for the new analgesic.

Three days later, however, the patient presented back to the same ED complaining of increased and now generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She was noted to be febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive. On physical examination, her abdomen was diffusely tender with guarding and rebound. She was given a 2-L bolus of intravenous (IV) normal saline and started on broad spectrum IV antibiotics. After another consultation with the patient’s OB/GYN surgeon, the patient was taken immediately to the operating room. On exploration, she was found to have a segment of perforated bowel and peritonitis. A portion of the bowel was resected, but her postoperative course was complicated by sepsis. After a 1-month stay in the hospital, she was discharged home.

The patient sued the EP—but not her OB/GYN—for failure to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis on her initial ED visit, or at least to admit her to the hospital for observation. The EP argued that even if a computed tomography (CT) scan had been performed on the initial visit, it probably would have been normal, since the bowel had not yet perforated. After trial, a defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

This case illustrates two important points. First, not every patient with abdominal pain requires a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis. So many malpractice cases against EPs involve the failure to perform advanced imaging. Unfortunately, that is usually only through the benefit of hindsight. For a patient with mild abdominal pain, only minimal tenderness on examination, and a negative laboratory workup, it can be perfectly appropriate to treat him or her symptomatically with close follow-up and specific instructions to return to the ED if his or her condition worsens (as was the case with this patient).

The second important point is to not over-rely on a consultant(s), especially if she or he has not independently examined the patient. When calling a consultant, it is best to have a specific question (ie, “Can you see the patient in the morning?”) or action (ie, “I would like to admit the patient to your service”). In general, the EP should not rely on the consultant to give “permission” to discharge the patient. As the physician seeing the patient, the EP is the most well-equipped to work up the patient and determine the needed disposition. Rare is the consultant that can arrive at a better disposition than the EP who performed the history and physical examination on the patient.

Regarding the patient’s GYN surgery, vaginal hysterectomy (VH) is preferred over abdominal hysterectomy (AH) for benign disease as it is associated with reduced infective morbidity and earlier return to normal activities.1 With respect to postoperative events, clinicians typically employ the Clavien-Dindo grading system for the classification of surgical complications.2 The system consists of five grades, ranging from Grade I (any deviation from normal postoperative course, without the need for pharmacological intervention) to Grade V (death).

Following hysterectomy, postoperative urinary or pelvic infections are not uncommon, with an incidence of 15% to 20%.1 In the Clavien-Dindo system, these complications would typically be considered Grade II (pharmacological treatment other than what is considered an acceptable therapeutic regimen), requiring antibiotics and no surgical intervention. Grade III complications, however, usually involve postoperative issues that require surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention, which in VH would include ureteral, bladder, or bowel injury.1 In a study by Gendy et al,1 the incidence of such complications posthysterectomy, ranged from 1.7% to 5.7%. So while not extremely common, serious complications can occur postoperatively.

The last point is a minor one, but a truth every EP needs to remember: While it may be difficult for a patient to sue her or his own physician, especially one with whom she or he has a longstanding patient-physician relationship, it is much easier for her or him to place blame upon and sue another physician—for example, the EP.

Missed Testicular Torsion?

| A 14-year-old boy presented to the ED with a several day history of abdominal pain with radiation to the right testicle. The patient denied any nausea, vomiting, or changes in bowel habits. He also denied any genitourinary symptoms, including dysuria or urinary frequency. The boy was otherwise in good health, on no medications, and up to date on his immunizations. |

The patient was a well appearing teenager in no acute distress. All vital signs were normal, as were the heart and lung examinations. The abdominal examination revealed mild, generalized tenderness without guarding or rebound. The genitalia examination was normal.

The EP ordered a CBC, urinalysis, and a testicular ultrasound, the results of which were all normal. The patient was discharged home with instructions to follow up with his pediatrician in 2 days and to return to the ED if his symptoms worsened.

The patient was seen by his pediatrician approximately 1 month later for his scheduled annual physical examination. The pediatrician, who was aware of the boy’s prior ED visit, found the patient in good health, and performed no additional testing.

Approximately 9 months after the initial ED visit, the patient was accidently kicked in the groin while jumping on a trampoline. He experienced immediate onset of severe, excruciating right testicular pain and presented to the ED approximately 24 hours later with continued pain and swelling. A testicular ultrasound was immediately ordered and demonstrated an enlarged right testicle due to torsion.

The patient underwent surgery to remove the right testicle. His family sued the EP and hospital from the initial visit (9 months earlier) for missed intermittent testicular torsion. They argued that the patient should have been referred to a urologist for further evaluation. In addition, the plaintiff claimed he could no longer participate in sports and suffered disfigurement as a result of the surgery. The EP asserted that the patient’s pain during that initial visit was primarily abdominal in nature and that an ultrasound of the testicles was normal, and did not reveal any evidence of testicular torsion. The EP further argued that the testicular torsion was due to the trauma incurred on the trampoline. According to published accounts, a defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

Testicular torsion occurs in a bimodal age distribution—during the first year of life (perinatal) and between ages 13 and 16 years (as was the case with this patient).1 In approximately 4% to 8% of patients, there is a history of an athletic event, strenuous physical activity, or trauma just prior to the onset of scrotal pain.2

Patients typically present with sudden onset of testicular pain that is frequently associated with nausea and vomiting. However, this condition can present with only lower abdominal pain—in part be due to the fact that adolescents and children may be reluctant to complain of testicular or scrotal pain out of fear or embarrassment.1 In all cases, a genital examination should be performed on every adolescent male with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain.3

On physical examination, the patient will usually have a swollen tender testicle. In comparison to the opposite side, the affected testicle is frequently raised and rests on a horizontal axis. The cremasteric reflex (ie, scratching the proximal inner thigh causes the ipsilateral testicle to rise) is frequently absent.4

Because of the time sensitive nature of the disease process, in classic presentations, a urologist should be immediately consulted. Ischemic changes to the testicle can begin within hours, and complete testicular atrophy occurs after 24 hours in most cases.4 Detorsion within 6 hours of onset of symptoms has a salvage rate of 90% to 100%, which drops to 25% to 50% after 12 hours and to less than 10% after 24 hours.4

For less obvious cases, color duplex testicular ultrasonography can be very helpful. Demonstration of decreased or absent blood flow is diagnostic and requires operative intervention. If untwisting the testis restores blood flow, then the condition is resolved; if this procedure fails, the testis is removed. Regardless of the outcome, the contralateral testis is fixed to prevent future torsion.

Intermittent testicular torsion is a difficult diagnosis to make. A history of recurrent unilateral scrotal pain is highly suspicious and warrants referral to a urologist. This patient had only one previous episode, which was primarily abdominal pain—not scrotal or testicular pain.

In this case, it appears the jury came to the correct decision. Given the patient had only one previous episode of abdominal pain, and an inciting event (trauma to the testicle) on the second presentation, this does not appear to be a case of missed intermittent testicular torsion. Rather, this was a correctly diagnosed testicular torsion with a delayed presentation, resulting in an unsalvageable testicle.

Reference - Sepsis Following Vaginal Hysterectomy

- Gendy R, Walsh CA, Walsh SR, Karantanis E. Vaginal hysterectomy versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(5):388.e1-8.

- Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009:250(2):187-196.

Reference - Missed Testicular Torsion?

- Pogorelić Z, Mrklić I, Jurić I. Do not forget to include testicular torsion in differential diagnosis of lower acute abdominal pain in young males. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(6 Pt B):1161-1165.

- Nicks BA, Manthey DE. Male genital problems. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Cine DM, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011:649.

- Lopez RN, Beasley SW. Testicular torsion: potential pitfalls in its diagnosis and management. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(2):E30-E32.

- Somani BK, Watson G, Townell N. Testicular torsion. BMJ. 2010;341:c3213.

Sepsis Following Vaginal Hysterectomy

| A 45-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of lower abdominal pain, which she described as gradual, aching, and intermittent. The patient stated that she had undergone a vaginal hysterectomy a few days prior and that the pain started less than 24 hours after discharge from the hospital. She denied fever or chills, nausea, or vomiting, and said that she had a bowel movement earlier that day. She also denied any urinary symptoms. Her medical history was significant only for hypothyroidism, for which she was taking levothyroxine. The patient denied cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption. She said she had been taking acetaminophen-hydrocodone for postoperative pain, but that it did not provide any relief. |

The patient’s vital signs were: temperature, 98.6˚F; blood pressure, 112/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 98 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal, as were the heart and lung examinations. The patient’s abdomen was soft, with mild diffuse lower abdominal tenderness. There was no guarding, rebound, or mass present. A gross nonspeculum examination of the vaginal area did not reveal any discharge or erythema; a rectal examination was not performed.

The EP ordered a complete blood count (CBC), lipase evaluation, and urinalysis. All test results were normal. The emergency physician (EP) then contacted the obstetrician-gynecologist (OB/GYN) who had performed the hysterectomy. The OB/GYN recommended the EP change the analgesic agent to acetaminophen-oxycodone and to encourage the patient to keep her follow-up postoperative appointment in 1 week. The EP followed these instructions and discharged the patient home with a prescription for the new analgesic.

Three days later, however, the patient presented back to the same ED complaining of increased and now generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She was noted to be febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive. On physical examination, her abdomen was diffusely tender with guarding and rebound. She was given a 2-L bolus of intravenous (IV) normal saline and started on broad spectrum IV antibiotics. After another consultation with the patient’s OB/GYN surgeon, the patient was taken immediately to the operating room. On exploration, she was found to have a segment of perforated bowel and peritonitis. A portion of the bowel was resected, but her postoperative course was complicated by sepsis. After a 1-month stay in the hospital, she was discharged home.

The patient sued the EP—but not her OB/GYN—for failure to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis on her initial ED visit, or at least to admit her to the hospital for observation. The EP argued that even if a computed tomography (CT) scan had been performed on the initial visit, it probably would have been normal, since the bowel had not yet perforated. After trial, a defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

This case illustrates two important points. First, not every patient with abdominal pain requires a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis. So many malpractice cases against EPs involve the failure to perform advanced imaging. Unfortunately, that is usually only through the benefit of hindsight. For a patient with mild abdominal pain, only minimal tenderness on examination, and a negative laboratory workup, it can be perfectly appropriate to treat him or her symptomatically with close follow-up and specific instructions to return to the ED if his or her condition worsens (as was the case with this patient).

The second important point is to not over-rely on a consultant(s), especially if she or he has not independently examined the patient. When calling a consultant, it is best to have a specific question (ie, “Can you see the patient in the morning?”) or action (ie, “I would like to admit the patient to your service”). In general, the EP should not rely on the consultant to give “permission” to discharge the patient. As the physician seeing the patient, the EP is the most well-equipped to work up the patient and determine the needed disposition. Rare is the consultant that can arrive at a better disposition than the EP who performed the history and physical examination on the patient.

Regarding the patient’s GYN surgery, vaginal hysterectomy (VH) is preferred over abdominal hysterectomy (AH) for benign disease as it is associated with reduced infective morbidity and earlier return to normal activities.1 With respect to postoperative events, clinicians typically employ the Clavien-Dindo grading system for the classification of surgical complications.2 The system consists of five grades, ranging from Grade I (any deviation from normal postoperative course, without the need for pharmacological intervention) to Grade V (death).

Following hysterectomy, postoperative urinary or pelvic infections are not uncommon, with an incidence of 15% to 20%.1 In the Clavien-Dindo system, these complications would typically be considered Grade II (pharmacological treatment other than what is considered an acceptable therapeutic regimen), requiring antibiotics and no surgical intervention. Grade III complications, however, usually involve postoperative issues that require surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention, which in VH would include ureteral, bladder, or bowel injury.1 In a study by Gendy et al,1 the incidence of such complications posthysterectomy, ranged from 1.7% to 5.7%. So while not extremely common, serious complications can occur postoperatively.

The last point is a minor one, but a truth every EP needs to remember: While it may be difficult for a patient to sue her or his own physician, especially one with whom she or he has a longstanding patient-physician relationship, it is much easier for her or him to place blame upon and sue another physician—for example, the EP.

Missed Testicular Torsion?

| A 14-year-old boy presented to the ED with a several day history of abdominal pain with radiation to the right testicle. The patient denied any nausea, vomiting, or changes in bowel habits. He also denied any genitourinary symptoms, including dysuria or urinary frequency. The boy was otherwise in good health, on no medications, and up to date on his immunizations. |

The patient was a well appearing teenager in no acute distress. All vital signs were normal, as were the heart and lung examinations. The abdominal examination revealed mild, generalized tenderness without guarding or rebound. The genitalia examination was normal.

The EP ordered a CBC, urinalysis, and a testicular ultrasound, the results of which were all normal. The patient was discharged home with instructions to follow up with his pediatrician in 2 days and to return to the ED if his symptoms worsened.