User login

Pediatric self-administration drives cough and cold drug mishaps

BALTIMORE – The vast majority of reported U.S. episodes of cough and cold medication serious adverse event episodes in young children occurred by an accidental, self-administration overdose, according to a review of all pediatric episodes collected by the designated national surveillance system during 2008-2014.

This pattern highlights the continued need for diligent education of families about the potential danger posed by these largely OTC products as well as a possible additional need for further improvement in protective packaging, Dr. G. Sam Wang said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Although the manufacturers of these products voluntarily changed their labeling in 2007 to say “do not use” in children younger than 4 years old, the continued vulnerability of very young children and the high rate of self-administration suggests that labeling restrictions alone are “unlikely to have a significant impact” on the problem, he said. “What could be better is storage and [packaging] engineering controls to prevent the accidental ingestions that seem to represent the majority of cases,” Dr. Wang said in an interview.

The good news was that the 4,250 reported U.S. cases during 2008-2014 in children younger than age 12 years and judged by an expert review panel to be at least potentially related to cold and cough medications represents a significant decline, compared with earlier periods, and is also “quite low” when compared with the millions of units in annual U.S. sales.

“The overall adverse event rate compared with the volume sold is in the single digits per million of products sold, and the rate has been declining,” said Dr. Wang, a pediatric toxicologist at the University of Colorado in Denver and a consultant to the Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, also in Denver, the group that maintains and reviews this registry, begun in January 2008. “I think we’re making progress,” but diligent education by physicians and other health care providers about the dangers posed by these drugs must continue, he said.

The analysis also identified that two drugs were by far the top culprits in causing pediatric adverse reactions to cough and cold medications, diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan. Diphenhydramine played a role in 53% of the 4,224 nonfatal adverse reaction cases and 54% of the 26 fatal cases identified by the registry panel as at least potentially related to a cough and cold medication, while dextromethorphan was responsible for 41% of the nonfatal and 19% of the fatal cases. In a majority of cases, these drugs were in products with a single active ingredient, although products with combined ingredients also played a role for some cases. Most often these drugs were in OTC formulations and in pediatric formulations.

Dr. Wang called it unlikely that manufacturers would formulate cold and cough medications without diphenhydramine or dextromethorphan because these drugs have the antitussive and sedative properties that consumers seek from cough and cold medications. He also noted that the addition of bittering agents to formulations have not had a history of reducing accidental self-administrations by children, but added “a good taste doesn’t help.”

During 2008-2014 U.S. surveillance by the registry review panel identified a total of 5,342 unique case reports of serious adverse events in children less than 12 years old and believed related to any of eight drugs commonly found in cold and cough medications. The reports came from any of five sources: the National Poison Data System, the Food and Drug Administration’s adverse event reporting system, safety reports to manufacturers, and through surveillance of the medical literature, and the news media. The panel winnowed these down to 4,250 cases at least potentially related to these drugs.

Among the 26 fatal cases, 16 (62%) occurred in children less than 2 years old and an additional four (15%) were in children aged 2 years to less than 4 years. Nine of these cases (35%) involved parental administration, with only two cases (8%) involving self-administration. An additional nine cases (35%) had no reported source of administration, and the remaining six (23%) cases involved other sources of administration. Seven of the 26 fatalities involved confirmed overdoses, with the dose unknown for the remaining 19 cases, Dr. Wang reported.

Among the 4,224 nonfatal cases, 15% occurred in children less than 2 years, 46% in children ages 2 years to less than 4 years, 19% in children 4 years to less than 6 years and 20% in children 6 years to less than 12 years. These cases involved a confirmed overdose in 73% of cases, a therapeutic range dose in 7%, with the remainder involving a dose of unknown size. Self-administration occurred 75% of the time.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The vast majority of reported U.S. episodes of cough and cold medication serious adverse event episodes in young children occurred by an accidental, self-administration overdose, according to a review of all pediatric episodes collected by the designated national surveillance system during 2008-2014.

This pattern highlights the continued need for diligent education of families about the potential danger posed by these largely OTC products as well as a possible additional need for further improvement in protective packaging, Dr. G. Sam Wang said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Although the manufacturers of these products voluntarily changed their labeling in 2007 to say “do not use” in children younger than 4 years old, the continued vulnerability of very young children and the high rate of self-administration suggests that labeling restrictions alone are “unlikely to have a significant impact” on the problem, he said. “What could be better is storage and [packaging] engineering controls to prevent the accidental ingestions that seem to represent the majority of cases,” Dr. Wang said in an interview.

The good news was that the 4,250 reported U.S. cases during 2008-2014 in children younger than age 12 years and judged by an expert review panel to be at least potentially related to cold and cough medications represents a significant decline, compared with earlier periods, and is also “quite low” when compared with the millions of units in annual U.S. sales.

“The overall adverse event rate compared with the volume sold is in the single digits per million of products sold, and the rate has been declining,” said Dr. Wang, a pediatric toxicologist at the University of Colorado in Denver and a consultant to the Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, also in Denver, the group that maintains and reviews this registry, begun in January 2008. “I think we’re making progress,” but diligent education by physicians and other health care providers about the dangers posed by these drugs must continue, he said.

The analysis also identified that two drugs were by far the top culprits in causing pediatric adverse reactions to cough and cold medications, diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan. Diphenhydramine played a role in 53% of the 4,224 nonfatal adverse reaction cases and 54% of the 26 fatal cases identified by the registry panel as at least potentially related to a cough and cold medication, while dextromethorphan was responsible for 41% of the nonfatal and 19% of the fatal cases. In a majority of cases, these drugs were in products with a single active ingredient, although products with combined ingredients also played a role for some cases. Most often these drugs were in OTC formulations and in pediatric formulations.

Dr. Wang called it unlikely that manufacturers would formulate cold and cough medications without diphenhydramine or dextromethorphan because these drugs have the antitussive and sedative properties that consumers seek from cough and cold medications. He also noted that the addition of bittering agents to formulations have not had a history of reducing accidental self-administrations by children, but added “a good taste doesn’t help.”

During 2008-2014 U.S. surveillance by the registry review panel identified a total of 5,342 unique case reports of serious adverse events in children less than 12 years old and believed related to any of eight drugs commonly found in cold and cough medications. The reports came from any of five sources: the National Poison Data System, the Food and Drug Administration’s adverse event reporting system, safety reports to manufacturers, and through surveillance of the medical literature, and the news media. The panel winnowed these down to 4,250 cases at least potentially related to these drugs.

Among the 26 fatal cases, 16 (62%) occurred in children less than 2 years old and an additional four (15%) were in children aged 2 years to less than 4 years. Nine of these cases (35%) involved parental administration, with only two cases (8%) involving self-administration. An additional nine cases (35%) had no reported source of administration, and the remaining six (23%) cases involved other sources of administration. Seven of the 26 fatalities involved confirmed overdoses, with the dose unknown for the remaining 19 cases, Dr. Wang reported.

Among the 4,224 nonfatal cases, 15% occurred in children less than 2 years, 46% in children ages 2 years to less than 4 years, 19% in children 4 years to less than 6 years and 20% in children 6 years to less than 12 years. These cases involved a confirmed overdose in 73% of cases, a therapeutic range dose in 7%, with the remainder involving a dose of unknown size. Self-administration occurred 75% of the time.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BALTIMORE – The vast majority of reported U.S. episodes of cough and cold medication serious adverse event episodes in young children occurred by an accidental, self-administration overdose, according to a review of all pediatric episodes collected by the designated national surveillance system during 2008-2014.

This pattern highlights the continued need for diligent education of families about the potential danger posed by these largely OTC products as well as a possible additional need for further improvement in protective packaging, Dr. G. Sam Wang said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Although the manufacturers of these products voluntarily changed their labeling in 2007 to say “do not use” in children younger than 4 years old, the continued vulnerability of very young children and the high rate of self-administration suggests that labeling restrictions alone are “unlikely to have a significant impact” on the problem, he said. “What could be better is storage and [packaging] engineering controls to prevent the accidental ingestions that seem to represent the majority of cases,” Dr. Wang said in an interview.

The good news was that the 4,250 reported U.S. cases during 2008-2014 in children younger than age 12 years and judged by an expert review panel to be at least potentially related to cold and cough medications represents a significant decline, compared with earlier periods, and is also “quite low” when compared with the millions of units in annual U.S. sales.

“The overall adverse event rate compared with the volume sold is in the single digits per million of products sold, and the rate has been declining,” said Dr. Wang, a pediatric toxicologist at the University of Colorado in Denver and a consultant to the Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, also in Denver, the group that maintains and reviews this registry, begun in January 2008. “I think we’re making progress,” but diligent education by physicians and other health care providers about the dangers posed by these drugs must continue, he said.

The analysis also identified that two drugs were by far the top culprits in causing pediatric adverse reactions to cough and cold medications, diphenhydramine and dextromethorphan. Diphenhydramine played a role in 53% of the 4,224 nonfatal adverse reaction cases and 54% of the 26 fatal cases identified by the registry panel as at least potentially related to a cough and cold medication, while dextromethorphan was responsible for 41% of the nonfatal and 19% of the fatal cases. In a majority of cases, these drugs were in products with a single active ingredient, although products with combined ingredients also played a role for some cases. Most often these drugs were in OTC formulations and in pediatric formulations.

Dr. Wang called it unlikely that manufacturers would formulate cold and cough medications without diphenhydramine or dextromethorphan because these drugs have the antitussive and sedative properties that consumers seek from cough and cold medications. He also noted that the addition of bittering agents to formulations have not had a history of reducing accidental self-administrations by children, but added “a good taste doesn’t help.”

During 2008-2014 U.S. surveillance by the registry review panel identified a total of 5,342 unique case reports of serious adverse events in children less than 12 years old and believed related to any of eight drugs commonly found in cold and cough medications. The reports came from any of five sources: the National Poison Data System, the Food and Drug Administration’s adverse event reporting system, safety reports to manufacturers, and through surveillance of the medical literature, and the news media. The panel winnowed these down to 4,250 cases at least potentially related to these drugs.

Among the 26 fatal cases, 16 (62%) occurred in children less than 2 years old and an additional four (15%) were in children aged 2 years to less than 4 years. Nine of these cases (35%) involved parental administration, with only two cases (8%) involving self-administration. An additional nine cases (35%) had no reported source of administration, and the remaining six (23%) cases involved other sources of administration. Seven of the 26 fatalities involved confirmed overdoses, with the dose unknown for the remaining 19 cases, Dr. Wang reported.

Among the 4,224 nonfatal cases, 15% occurred in children less than 2 years, 46% in children ages 2 years to less than 4 years, 19% in children 4 years to less than 6 years and 20% in children 6 years to less than 12 years. These cases involved a confirmed overdose in 73% of cases, a therapeutic range dose in 7%, with the remainder involving a dose of unknown size. Self-administration occurred 75% of the time.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Serious adverse events in U.S. children caused by cough and cold medications most commonly occur from self-administration in children younger than 4 years old.

Major finding: Three-quarters of serious adverse events occurred by self-administration, with 61% of episodes in children younger than 4 years old.

Data source: Review of 5,342 reported U.S. cough and cold medication serious adverse event episodes in children during 2008-2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Wang had no disclosures.

ABMS approves new addiction medicine subspecialty

Many more physicians seeking to subspecialize in addiction medicine will now have the official blessing of the American Board of Medical Specialties.

ABMS announced March 14 its approval of an addiction medicine subspecialty that the American Board of Preventive Medicine (ABPM) will sponsor.

Physicians who are certified by any of the 24 ABMS member boards can apply for the addiction medicine certification. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology offers certification in addiction psychiatry, but only to psychiatrists.

ABPM hasn’t set a date for the addiction medicine subspecialty’s first board certification exam, which the board will develop. ABPM will post updates on its website, www.theabpm.org.

“Increasing the number of well-trained and certified specialists in addiction medicine will significantly increase access to care for those in need of intervention and treatment,” said ABPM’s board chair, Dr. Denece O. Kesler, in a statement.

One in seven Americans older than 12 years meets medical criteria for an addiction to nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs, according to statistics from the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. But only 11% of those who need treatment are able to receive it, in part because of a lack of addiction medicine providers.

The American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM) hailed the new subspecialty. “This is a great day for addiction medicine,” Dr. Robert J. Sokol, president of ABAM and the Addiction Medicine Foundation (AMF), said in a statement. “This landmark event, more than any other, recognizes addiction as a preventable and treatable disease.”

ABAM has certified 3,902 physicians, according to the organization, which is not an ABMS member board. There are 40 AMF-sponsored fellowship training programs nationally, with a commitment to establish 125 more by 2025. AMF expects the ABMS recognition will lead to the fellowships gaining the imprimatur of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education.

“This is a positive development that has the potential to address a serious public health problem,” Dr. Daniel Lieberman, vice chairman of the psychiatry and behavioral health department at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “This action will reassure doctors who are interested in addiction medicine that the time and effort they put into obtaining additional training will give them the status of a subspecialist with recognized expertise. It may also encourage young doctors to consider addiction medicine as a career path.”

Meanwhile, a package of mental health reforms moving in the U.S. Senate could improve patients’ access to addiction medicine providers. One of the bills, the TREAT Act, would increase the number of substance use detoxification patients that a qualified provider is legally allowed to treat annually, from 30 patients to 100 patients. The legislation also would allow those practitioners to request permission to annually treat unlimited numbers of patients thereafter.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Many more physicians seeking to subspecialize in addiction medicine will now have the official blessing of the American Board of Medical Specialties.

ABMS announced March 14 its approval of an addiction medicine subspecialty that the American Board of Preventive Medicine (ABPM) will sponsor.

Physicians who are certified by any of the 24 ABMS member boards can apply for the addiction medicine certification. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology offers certification in addiction psychiatry, but only to psychiatrists.

ABPM hasn’t set a date for the addiction medicine subspecialty’s first board certification exam, which the board will develop. ABPM will post updates on its website, www.theabpm.org.

“Increasing the number of well-trained and certified specialists in addiction medicine will significantly increase access to care for those in need of intervention and treatment,” said ABPM’s board chair, Dr. Denece O. Kesler, in a statement.

One in seven Americans older than 12 years meets medical criteria for an addiction to nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs, according to statistics from the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. But only 11% of those who need treatment are able to receive it, in part because of a lack of addiction medicine providers.

The American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM) hailed the new subspecialty. “This is a great day for addiction medicine,” Dr. Robert J. Sokol, president of ABAM and the Addiction Medicine Foundation (AMF), said in a statement. “This landmark event, more than any other, recognizes addiction as a preventable and treatable disease.”

ABAM has certified 3,902 physicians, according to the organization, which is not an ABMS member board. There are 40 AMF-sponsored fellowship training programs nationally, with a commitment to establish 125 more by 2025. AMF expects the ABMS recognition will lead to the fellowships gaining the imprimatur of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education.

“This is a positive development that has the potential to address a serious public health problem,” Dr. Daniel Lieberman, vice chairman of the psychiatry and behavioral health department at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “This action will reassure doctors who are interested in addiction medicine that the time and effort they put into obtaining additional training will give them the status of a subspecialist with recognized expertise. It may also encourage young doctors to consider addiction medicine as a career path.”

Meanwhile, a package of mental health reforms moving in the U.S. Senate could improve patients’ access to addiction medicine providers. One of the bills, the TREAT Act, would increase the number of substance use detoxification patients that a qualified provider is legally allowed to treat annually, from 30 patients to 100 patients. The legislation also would allow those practitioners to request permission to annually treat unlimited numbers of patients thereafter.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Many more physicians seeking to subspecialize in addiction medicine will now have the official blessing of the American Board of Medical Specialties.

ABMS announced March 14 its approval of an addiction medicine subspecialty that the American Board of Preventive Medicine (ABPM) will sponsor.

Physicians who are certified by any of the 24 ABMS member boards can apply for the addiction medicine certification. The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology offers certification in addiction psychiatry, but only to psychiatrists.

ABPM hasn’t set a date for the addiction medicine subspecialty’s first board certification exam, which the board will develop. ABPM will post updates on its website, www.theabpm.org.

“Increasing the number of well-trained and certified specialists in addiction medicine will significantly increase access to care for those in need of intervention and treatment,” said ABPM’s board chair, Dr. Denece O. Kesler, in a statement.

One in seven Americans older than 12 years meets medical criteria for an addiction to nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs, according to statistics from the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. But only 11% of those who need treatment are able to receive it, in part because of a lack of addiction medicine providers.

The American Board of Addiction Medicine (ABAM) hailed the new subspecialty. “This is a great day for addiction medicine,” Dr. Robert J. Sokol, president of ABAM and the Addiction Medicine Foundation (AMF), said in a statement. “This landmark event, more than any other, recognizes addiction as a preventable and treatable disease.”

ABAM has certified 3,902 physicians, according to the organization, which is not an ABMS member board. There are 40 AMF-sponsored fellowship training programs nationally, with a commitment to establish 125 more by 2025. AMF expects the ABMS recognition will lead to the fellowships gaining the imprimatur of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education.

“This is a positive development that has the potential to address a serious public health problem,” Dr. Daniel Lieberman, vice chairman of the psychiatry and behavioral health department at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “This action will reassure doctors who are interested in addiction medicine that the time and effort they put into obtaining additional training will give them the status of a subspecialist with recognized expertise. It may also encourage young doctors to consider addiction medicine as a career path.”

Meanwhile, a package of mental health reforms moving in the U.S. Senate could improve patients’ access to addiction medicine providers. One of the bills, the TREAT Act, would increase the number of substance use detoxification patients that a qualified provider is legally allowed to treat annually, from 30 patients to 100 patients. The legislation also would allow those practitioners to request permission to annually treat unlimited numbers of patients thereafter.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

New CDC opioid guideline targets overprescribing for chronic pain

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Marijuana tourists also visiting Colorado EDs

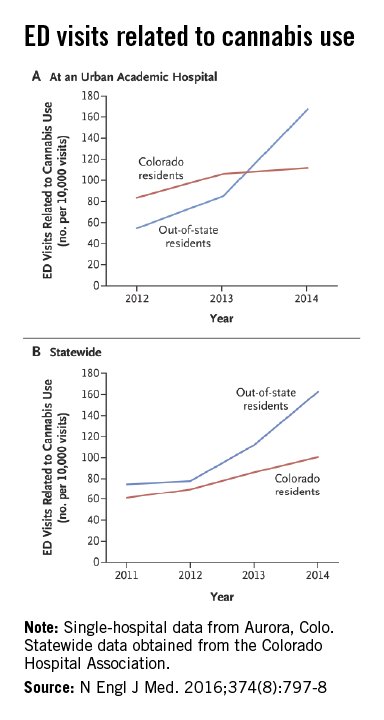

Out-of-state residents appear to be driving the recent increases in marijuana-related emergency department visits in Colorado, Dr. Howard S. Kim and his associates reported online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Using statewide data from the Colorado Hospital Association, they found that ED visits related to cannabis by out-of-state residents rose from 78 per 10,000 ED visits in 2012 to 163 per 10,000 in 2014, an increase of 109%. For Colorado residents, cannabis-related ED admissions over that same time period went up 44% – from 70 per 10,000 to 101, said Dr. Kim of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24;374[8]:797-8. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1515009).

The investigators also looked at a single urban academic hospital in Aurora, Colo., and found that cannabis-related ED visits there for out-of-state residents went from 85 per 10,000 visits in 2013 to 168 per 10,000 in 2014, compared with respective rates of 106 and 112 for Colorado residents.

“The flattening of the rates of ED visits possibly related to cannabis use among Colorado residents in an urban hospital may represent a learning curve during the period when marijuana was potentially available to Colorado residents for medical use (medical marijuana period) but was largely inaccessible to out-of-state residents,” they suggested.

Out-of-state residents appear to be driving the recent increases in marijuana-related emergency department visits in Colorado, Dr. Howard S. Kim and his associates reported online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Using statewide data from the Colorado Hospital Association, they found that ED visits related to cannabis by out-of-state residents rose from 78 per 10,000 ED visits in 2012 to 163 per 10,000 in 2014, an increase of 109%. For Colorado residents, cannabis-related ED admissions over that same time period went up 44% – from 70 per 10,000 to 101, said Dr. Kim of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24;374[8]:797-8. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1515009).

The investigators also looked at a single urban academic hospital in Aurora, Colo., and found that cannabis-related ED visits there for out-of-state residents went from 85 per 10,000 visits in 2013 to 168 per 10,000 in 2014, compared with respective rates of 106 and 112 for Colorado residents.

“The flattening of the rates of ED visits possibly related to cannabis use among Colorado residents in an urban hospital may represent a learning curve during the period when marijuana was potentially available to Colorado residents for medical use (medical marijuana period) but was largely inaccessible to out-of-state residents,” they suggested.

Out-of-state residents appear to be driving the recent increases in marijuana-related emergency department visits in Colorado, Dr. Howard S. Kim and his associates reported online Feb. 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Using statewide data from the Colorado Hospital Association, they found that ED visits related to cannabis by out-of-state residents rose from 78 per 10,000 ED visits in 2012 to 163 per 10,000 in 2014, an increase of 109%. For Colorado residents, cannabis-related ED admissions over that same time period went up 44% – from 70 per 10,000 to 101, said Dr. Kim of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his associates (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 24;374[8]:797-8. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1515009).

The investigators also looked at a single urban academic hospital in Aurora, Colo., and found that cannabis-related ED visits there for out-of-state residents went from 85 per 10,000 visits in 2013 to 168 per 10,000 in 2014, compared with respective rates of 106 and 112 for Colorado residents.

“The flattening of the rates of ED visits possibly related to cannabis use among Colorado residents in an urban hospital may represent a learning curve during the period when marijuana was potentially available to Colorado residents for medical use (medical marijuana period) but was largely inaccessible to out-of-state residents,” they suggested.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Designer drug symptoms can mimic schizophrenia, anxiety, depression

LAS VEGAS – People who use spice, bath salts, and other so-called designer drugs may present with symptoms that resemble numerous psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and depression.

“Given the recent emergence of designer drugs, the long-term consequences of their use have not been extensively studied and are relatively unknown,” Dr. William M. Sauve said at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Sauve, medical director of TMS NeuroHealth Centers of Richmond and Charlottesville, both in Virginia, said designer drugs have grown in popularity in recent years because they are perceived as legal alternatives to illicit substances. In addition, their detection by standard drug toxicology screens is limited.

In October 2011, components of designer drugs, including synthetic cannabinoids and the major constituents of bath salts, were categorized as emergency Schedule I substances. In July 2012, President Obama signed the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act, which doubled the time that a substance may be temporarily assigned to Schedule I, from 18 months to 36 months.

“Under federal law, any chemical that is similar to a classified drug and is meant to be used for the same purposes is considered to be classified,” Dr. Sauve said. However, designer drugs “get labeled ‘not for human consumption’ and can be sold out in the open and camouflaged under names such as ‘stain remover,’ ‘research chemicals,’ and even ‘insect repellent.’ That’s why it’s very difficult for the law to catch up with these things. Active ingredients are also a moving target.”

He discussed three types of these designer drugs: synthetic cannabinoids, bath salts, and krokodil.

Synthetic cannabinoids mimic THC

Also known as spice, K2, and incense, these substances began to appear in the United States in 2008 and are mostly used by males. Primarily inhaled, these substances are meant to mimic the effects of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They work by decreasing levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and by increasing levels of glutamate and dopamine. “Serotonin levels can also be affected indirectly by endocannabinoid control of GABA and glutamate release,” he added.

Unlike marijuana, which is a partial agonist at the cannabinoid 1 (CB-1) receptor, synthetics are full agonists at the CB-1 receptor, “so as you use it, it will hit every receptor until you have maximal stimulation, and it may have 800 times greater affinity than THC,” he said. Signs and symptoms of acute intoxication can be wide ranging, from agitation and dysphoria to paranoia and tachycardia, and can last up to 6 hours. While commercial tests are available to detect synthetic cannabinoid metabolites, formulations change so often that “most tests quickly become obsolete,” Dr. Sauve said. He noted that intoxication with spice should be suspected in patients who present with bizarre behavior, anxiety, agitation, and/or psychosis in those with no known psychiatric history. Intravaneous benzodiazepines can be used for agitation and seizures. While knowledge of their long-term impact is lacking, synthetic cannabinoids may increase the risk of subsequent psychosis by threefold, he said, and kidney failure has been reported in several cases.

Bath salts widely available

Also labeled as “plant food,” “pond water cleaner,” “novelty collector’s items,” and “not for human consumption,” these stimulants began to be used in the United States in 2010, and are widely available online and in smoke shops. Users have a median age of 26 years, Dr. Sauve said, and are mostly male.

Bath salts may be comprised of methcathinones, especially synthetic cathinones. Natural cathinones are found in khat, a root from a shrub that is chewed upon primarily by people in North Africa. Bath salts also may contain methamphetamine analogues, which can be synthesized from ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. These include methylone (similar to MDMA, or ecstasy), mephedrone (similar to methamphetamine), and methylenedioxypyrovalerone (similar to cocaine). Bath salts can be inhaled, injected, snorted, swallowed, or inserted into the rectum or vagina, and effects occur in doses of 2-5 mg. Pharmacological effects vary and may include increased plasma norepinephrine, sympathetic effects, serotonin syndrome, and increased dopamine. He also noted that the transition from recreational to addictive use “may occur in a matter of days.”

Signs of toxicity with bath salts, Dr. Sauve continued, include the following: disorientation and agitation; dilated pupils with involuntary eye movements; lockjaw and teeth grinding; rapid, inappropriate, incoherent speech; being emotionally, verbally, or physically abusive, and having elevated liver enzymes and/or liver failure.

Treatment is primarily supportive and may include sedatives for anxiety, agitation, aggression, tremors, seizures, and psychosis. Physical restraints may be necessary.

Krokodil not seen much in U.S.

Formally known as desomorphine, this substance is synthesized from codeine and became popular in Russia after a crackdown on heroin there in 2010, Dr. Sauve said. The ingredients for krokodil synthesis include tablets containing codeine, caustic soda, gasoline, hydrochloric acid, iodine from disinfectants, and red phosphorus from matchboxes. While desomorphine is believed to be highly addictive, “all the other sequelae of krokodil are generally thought to be a result of phosphorus” and other substances. No good data exist in the prevalence of its use, he said. “We’re not really seeing this much in the United States, because it’s way too easy to get Oxycontin and heroin [here].”

Dr. Sauve reported that he is a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. He also reported being a member of the speakers bureau or receiving honoraria from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

LAS VEGAS – People who use spice, bath salts, and other so-called designer drugs may present with symptoms that resemble numerous psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and depression.

“Given the recent emergence of designer drugs, the long-term consequences of their use have not been extensively studied and are relatively unknown,” Dr. William M. Sauve said at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Sauve, medical director of TMS NeuroHealth Centers of Richmond and Charlottesville, both in Virginia, said designer drugs have grown in popularity in recent years because they are perceived as legal alternatives to illicit substances. In addition, their detection by standard drug toxicology screens is limited.

In October 2011, components of designer drugs, including synthetic cannabinoids and the major constituents of bath salts, were categorized as emergency Schedule I substances. In July 2012, President Obama signed the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act, which doubled the time that a substance may be temporarily assigned to Schedule I, from 18 months to 36 months.

“Under federal law, any chemical that is similar to a classified drug and is meant to be used for the same purposes is considered to be classified,” Dr. Sauve said. However, designer drugs “get labeled ‘not for human consumption’ and can be sold out in the open and camouflaged under names such as ‘stain remover,’ ‘research chemicals,’ and even ‘insect repellent.’ That’s why it’s very difficult for the law to catch up with these things. Active ingredients are also a moving target.”

He discussed three types of these designer drugs: synthetic cannabinoids, bath salts, and krokodil.

Synthetic cannabinoids mimic THC

Also known as spice, K2, and incense, these substances began to appear in the United States in 2008 and are mostly used by males. Primarily inhaled, these substances are meant to mimic the effects of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They work by decreasing levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and by increasing levels of glutamate and dopamine. “Serotonin levels can also be affected indirectly by endocannabinoid control of GABA and glutamate release,” he added.

Unlike marijuana, which is a partial agonist at the cannabinoid 1 (CB-1) receptor, synthetics are full agonists at the CB-1 receptor, “so as you use it, it will hit every receptor until you have maximal stimulation, and it may have 800 times greater affinity than THC,” he said. Signs and symptoms of acute intoxication can be wide ranging, from agitation and dysphoria to paranoia and tachycardia, and can last up to 6 hours. While commercial tests are available to detect synthetic cannabinoid metabolites, formulations change so often that “most tests quickly become obsolete,” Dr. Sauve said. He noted that intoxication with spice should be suspected in patients who present with bizarre behavior, anxiety, agitation, and/or psychosis in those with no known psychiatric history. Intravaneous benzodiazepines can be used for agitation and seizures. While knowledge of their long-term impact is lacking, synthetic cannabinoids may increase the risk of subsequent psychosis by threefold, he said, and kidney failure has been reported in several cases.

Bath salts widely available

Also labeled as “plant food,” “pond water cleaner,” “novelty collector’s items,” and “not for human consumption,” these stimulants began to be used in the United States in 2010, and are widely available online and in smoke shops. Users have a median age of 26 years, Dr. Sauve said, and are mostly male.

Bath salts may be comprised of methcathinones, especially synthetic cathinones. Natural cathinones are found in khat, a root from a shrub that is chewed upon primarily by people in North Africa. Bath salts also may contain methamphetamine analogues, which can be synthesized from ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. These include methylone (similar to MDMA, or ecstasy), mephedrone (similar to methamphetamine), and methylenedioxypyrovalerone (similar to cocaine). Bath salts can be inhaled, injected, snorted, swallowed, or inserted into the rectum or vagina, and effects occur in doses of 2-5 mg. Pharmacological effects vary and may include increased plasma norepinephrine, sympathetic effects, serotonin syndrome, and increased dopamine. He also noted that the transition from recreational to addictive use “may occur in a matter of days.”

Signs of toxicity with bath salts, Dr. Sauve continued, include the following: disorientation and agitation; dilated pupils with involuntary eye movements; lockjaw and teeth grinding; rapid, inappropriate, incoherent speech; being emotionally, verbally, or physically abusive, and having elevated liver enzymes and/or liver failure.

Treatment is primarily supportive and may include sedatives for anxiety, agitation, aggression, tremors, seizures, and psychosis. Physical restraints may be necessary.

Krokodil not seen much in U.S.

Formally known as desomorphine, this substance is synthesized from codeine and became popular in Russia after a crackdown on heroin there in 2010, Dr. Sauve said. The ingredients for krokodil synthesis include tablets containing codeine, caustic soda, gasoline, hydrochloric acid, iodine from disinfectants, and red phosphorus from matchboxes. While desomorphine is believed to be highly addictive, “all the other sequelae of krokodil are generally thought to be a result of phosphorus” and other substances. No good data exist in the prevalence of its use, he said. “We’re not really seeing this much in the United States, because it’s way too easy to get Oxycontin and heroin [here].”

Dr. Sauve reported that he is a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. He also reported being a member of the speakers bureau or receiving honoraria from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

LAS VEGAS – People who use spice, bath salts, and other so-called designer drugs may present with symptoms that resemble numerous psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and depression.

“Given the recent emergence of designer drugs, the long-term consequences of their use have not been extensively studied and are relatively unknown,” Dr. William M. Sauve said at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Dr. Sauve, medical director of TMS NeuroHealth Centers of Richmond and Charlottesville, both in Virginia, said designer drugs have grown in popularity in recent years because they are perceived as legal alternatives to illicit substances. In addition, their detection by standard drug toxicology screens is limited.

In October 2011, components of designer drugs, including synthetic cannabinoids and the major constituents of bath salts, were categorized as emergency Schedule I substances. In July 2012, President Obama signed the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act, which doubled the time that a substance may be temporarily assigned to Schedule I, from 18 months to 36 months.

“Under federal law, any chemical that is similar to a classified drug and is meant to be used for the same purposes is considered to be classified,” Dr. Sauve said. However, designer drugs “get labeled ‘not for human consumption’ and can be sold out in the open and camouflaged under names such as ‘stain remover,’ ‘research chemicals,’ and even ‘insect repellent.’ That’s why it’s very difficult for the law to catch up with these things. Active ingredients are also a moving target.”

He discussed three types of these designer drugs: synthetic cannabinoids, bath salts, and krokodil.

Synthetic cannabinoids mimic THC

Also known as spice, K2, and incense, these substances began to appear in the United States in 2008 and are mostly used by males. Primarily inhaled, these substances are meant to mimic the effects of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They work by decreasing levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and by increasing levels of glutamate and dopamine. “Serotonin levels can also be affected indirectly by endocannabinoid control of GABA and glutamate release,” he added.

Unlike marijuana, which is a partial agonist at the cannabinoid 1 (CB-1) receptor, synthetics are full agonists at the CB-1 receptor, “so as you use it, it will hit every receptor until you have maximal stimulation, and it may have 800 times greater affinity than THC,” he said. Signs and symptoms of acute intoxication can be wide ranging, from agitation and dysphoria to paranoia and tachycardia, and can last up to 6 hours. While commercial tests are available to detect synthetic cannabinoid metabolites, formulations change so often that “most tests quickly become obsolete,” Dr. Sauve said. He noted that intoxication with spice should be suspected in patients who present with bizarre behavior, anxiety, agitation, and/or psychosis in those with no known psychiatric history. Intravaneous benzodiazepines can be used for agitation and seizures. While knowledge of their long-term impact is lacking, synthetic cannabinoids may increase the risk of subsequent psychosis by threefold, he said, and kidney failure has been reported in several cases.

Bath salts widely available

Also labeled as “plant food,” “pond water cleaner,” “novelty collector’s items,” and “not for human consumption,” these stimulants began to be used in the United States in 2010, and are widely available online and in smoke shops. Users have a median age of 26 years, Dr. Sauve said, and are mostly male.

Bath salts may be comprised of methcathinones, especially synthetic cathinones. Natural cathinones are found in khat, a root from a shrub that is chewed upon primarily by people in North Africa. Bath salts also may contain methamphetamine analogues, which can be synthesized from ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. These include methylone (similar to MDMA, or ecstasy), mephedrone (similar to methamphetamine), and methylenedioxypyrovalerone (similar to cocaine). Bath salts can be inhaled, injected, snorted, swallowed, or inserted into the rectum or vagina, and effects occur in doses of 2-5 mg. Pharmacological effects vary and may include increased plasma norepinephrine, sympathetic effects, serotonin syndrome, and increased dopamine. He also noted that the transition from recreational to addictive use “may occur in a matter of days.”

Signs of toxicity with bath salts, Dr. Sauve continued, include the following: disorientation and agitation; dilated pupils with involuntary eye movements; lockjaw and teeth grinding; rapid, inappropriate, incoherent speech; being emotionally, verbally, or physically abusive, and having elevated liver enzymes and/or liver failure.

Treatment is primarily supportive and may include sedatives for anxiety, agitation, aggression, tremors, seizures, and psychosis. Physical restraints may be necessary.

Krokodil not seen much in U.S.

Formally known as desomorphine, this substance is synthesized from codeine and became popular in Russia after a crackdown on heroin there in 2010, Dr. Sauve said. The ingredients for krokodil synthesis include tablets containing codeine, caustic soda, gasoline, hydrochloric acid, iodine from disinfectants, and red phosphorus from matchboxes. While desomorphine is believed to be highly addictive, “all the other sequelae of krokodil are generally thought to be a result of phosphorus” and other substances. No good data exist in the prevalence of its use, he said. “We’re not really seeing this much in the United States, because it’s way too easy to get Oxycontin and heroin [here].”

Dr. Sauve reported that he is a consultant to Avanir Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. He also reported being a member of the speakers bureau or receiving honoraria from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE NPA PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

Case Studies In Toxicology: Withdrawal: Another Danger of Diversion

Case

A 34-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented to the ED after he had a seizure during his regular methadone-treatment program meeting. While at the clinic, attendees witnessed the patient experience a loss of consciousness accompanied by generalized shaking movements of his extremities, which lasted for several minutes.

Upon arrival in the ED, the patient stated that he had a mild headache; he was otherwise asymptomatic. Initial vital signs were: blood pressure, 126/80 mm Hg; heart rate, 82 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/minute; and temperature, 97.3°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air, and a finger-stick glucose test was 140 mg/dL.

Physical examination revealed a small right-sided parietal hematoma. The patient had no tremors and his neurological examination, including mental status, was normal. When reviewing the patient’s medical history and medications in the health record, it was noted that the patient had a prescription for alprazolam for an anxiety disorder. On further questioning, the patient admitted that he had sold his last alprazolam prescription and had not been taking the drug for the past week.

What characterizes the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome?

Although introduced into clinical practice in the 1960s, the potential for dependence and a withdrawal syndrome was not appreciated until the early 1980s. This clinical syndrome can manifest with a wide variety of findings, most commonly with what are termed “rebound effects” or “rebound hyperexcitability.” These effects include anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbance, tremulousness, irritability, sweating, psychomotor agitation, difficulty in concentration, nausea, weight loss, palpitations, headache, muscular pain and stiffness, or generalized weakness.2 More severe manifestations include delirium, seizures, or psychosis. Often, these symptoms and signs may be confused with the very manifestations that prompted the initial use of the BZD, a reemergence of which can exacerbate the withdrawal syndrome.

When does benzodiazepine withdrawal occur?

The exact time course of BZD withdrawal can vary considerably and, unlike alcohol withdrawal (which occurs from a single compound, ethanol), can be difficult to characterize. The onset of withdrawal symptoms is dependent on a number of factors, including the half-life of the BZD involved. For example, delayed onset withdrawal symptoms of up to 3 weeks after cessation of the medication are described with long-acting BZDs such as chlordiazepoxide and diazepam. Conversely, symptoms may present as early as 24 to 48 hours after abrupt termination of BZDs with shorter half-lives, alprazolam and lorazepam. This variable time of onset differs considerably from other withdrawal syndromes, notably ethanol withdrawal. While both syndromes correlate to the individual patient’s severity of dependence, alcohol withdrawal follows a more predictable time course.

Some authors distinguish a rebound syndrome from a true withdrawal syndrome, the former of which is self-limited in nature and the result of cessation of treatment for the primary disease process. In this model, rebound symptoms begin 1 to 4 days after the abrupt cessation or dose reduction of the BZD, and are relatively short-lived, lasting 2 to 3 days.2

What is the appropriate treatment for benzodiazepine withdrawal?

The standard therapy for almost all withdrawal syndromes is reinstitution of the causal agent. A number of non-BZD-based treatment strategies have been investigated, and all have met with limited success. Of these, anticonvulsant drugs such as carbamazepine and valproic acid were initially considered promising based on case reports and small case series.4 These medications ultimately proved ineffective in randomized, placebo-controlled studies.5 β-Adrenergic antagonists, such as propranolol, have been studied as a method to normalize a patient’s vital signs but also proved nonbeneficial in managing withdrawal.5,6