User login

VIDEO: Immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

WASHINGTON – During a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Adam Friedman, MD, presented on off-label use of immunomodulators for inflammatory skin diseases, the highlights of which he shared with fellow George Washington University dermatologist, A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, in an interview following the session.

Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington,

For example, as reflected in PubMed searches, low-dose naltrexone, which has to be compounded, is being used for such diseases as Hailey-Hailey and lichen planopilaris, said Dr. Friedman, who is using it for his mast cell activation syndrome patients. During the interview, he also describes his treatment approach for urticaria.

In his final remarks, Dr. Friedman encourages colleagues to “get creative,” publish, and talk about their experiences with off-label treatments in dermatology, citing the example of an article that mentioned using pioglitazone for lichen planopilaris. This article stimulated interest in using the type 2 diabetes agent pioglitazone to treat this skin disease, he notes.

Dr. Friedman and Dr. Kirkorian, a pediatric dermatologist at George Washington University and interim chief of pediatric dermatology at Children’s National in Washington had no relevant disclosures.

Case report may link gluteal implants to lymphoma

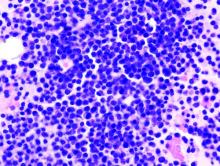

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

Patients with textured silicone gluteal implants could be at risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, based on a possible case of ALCL in a patient diagnosed 1 year after implant placement.

The 49-year-old woman was initially diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase–negative ALCL via a lung mass and pleural fluid before bilateral gluteal ulceration occurred 1 month later, reported Orr Shauly of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and his colleagues.

Soft-tissue disease and fluid accumulation around the gluteal implants suggested that the lung mass had metastasized from primary neoplasia in the gluteal region. If ALCL did originate at the site of the gluteal implants, it would represent a first for silicone implant–associated ALCL, which has historically been associated exclusively with breast implants.

“As many as 200 cases of [breast implant-associated ALCL] have been described worldwide, with a majority in the context of cosmetic primary breast augmentation or cancer-related breast reconstruction with the use of a textured implant (57% of all cases),” the investigators wrote in Aesthetic Surgery Journal. “Recently however, it has been hypothesized that the relationship of ALCL with the placement of textured silicone implants may not [be] limited to the breast due to its multifactorial nature and association with texturization of the implant surface.”

During the initial work-up, a CT showed fluid collection and enhancement around the gluteal implants. Following ALCL diagnosis via lung mass biopsy and histopathology, the patient was transferred to a different facility for chemotherapy. When the patient presented 1 month later to the original facility with gluteal ulceration, the oncology team suspected infection; however, all cultures from fluid around the implants were negative.

Because of the possibility of false-negative tests, the patient was started on a regimen of acyclovir, vancomycin, metronidazole, and isavuconazole. Explantation was planned, but before this could occur, the patient deteriorated rapidly and died of respiratory and renal failure.

ALCL was not confirmed via cytology or histopathology in the gluteal region, and the patient’s family did not consent to autopsy, so a definitive diagnosis of gluteal implant–associated ALCL remained elusive.

“In this instance, it can only be concluded that the patient’s condition may have been associated with placement of textured silicone gluteal implants, but [we] still lack evidence of causation,” the investigators wrote. “It should also be noted that ALCL does not typically present with skin ulceration, and this may be a unique disease process in this patient or as a result of her bedridden state given the late stage of her disease. Furthermore, this presentation was uniquely aggressive and presented extremely quickly after placement of the gluteal implants. In most patients, ALCL develops and presents approximately 10 years after implantation.”

The investigators cautioned that “care should be taken to avoid sensationalizing all implant-associated ALCL.”

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest and the study did not receive funding.

SOURCE: Shauly O et al. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz044.

FROM AESTHETIC SURGERY JOURNAL

Necrotizing Infection of the Upper Extremity: A Veterans Affairs Medical Center Experience (2008-2017)

Necrotizing infection of the extremity is a rare but potentially lethal diagnosis with a mortality rate in the range of 17% to 35%.1-4 The plastic surgery service at the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) treats all hand emergencies, including upper extremity infection, in the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Heath System. There has been a well-coordinated emergency hand care system in place for several years that includes specialty templates on the electronic health record, pre-existing urgent clinic appointments, and single service surgical specialty care.5 This facilitates a fluid line of communication between primary care, emergency department (ED) providers, and surgical specialties. The objective of the study was to evaluate our identification, treatment, and outcome of these serious infections.

Methods

The MRVAMC Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective review of necrotizing infection of the upper extremity treated at the facility by the plastic surgery service. Surgical cases over a 9-year period (June 5, 2008-June 5, 2017) were identified by CPT (current procedural technology) codes for amputation and/or debridement of the upper extremity. The charts were reviewed for evidence of necrotizing infection by clinical description or pathology report. The patients’ age, sex, etiology, comorbidities from their problem list, vitals, and laboratory results were recorded upon arrival at the hospital. Time from presentation to surgery, treatment, and outcomes were recorded.

Results

Ten patients were treated for necrotizing infection of the upper extremity over a 9-year period; all were men with an average age of 64 years. Etiologies included nail biting, “bug bites,” crush injuries, burns, suspected IV drug use, and unknown. Nine of 10 patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). Most did not show evidence of hemodynamic instability on hospital arrival (Table). One patient was hypotensive with a mean arterial blood pressure < 65 mm Hg, 2 had heart rates > 100 beats/min, 1 patient had a temperature > 38° C, and 7 had elevated white blood cell (WBC) counts ranging from 11 to 24 k/cmm. Two undiagnosed patients with DM (patients 1 and 8) expressed no complaints of pain and presented with blood glucose > 450 mg/dL with hemoglobin A1c levels > 12%.

Infectious disease and critical care services were involved in the treatment of several cases when requested. A computed tomography (CT) scan was used in 2 of the patients (patients 1 and 4) to assist in the diagnosis (Figure 1).

Seven patients out of 10 were treated with surgery within 24 hours on hospital arrival. The severity of the pathology was not initially recognized in 2 of the patients earlier in the review. A third patient resisted surgical treatment until the second hospital day. Four patients had from 1 to 3 digital amputations, 2 patients had wrist disarticulations, and 1 had a distal forearm amputation.

Antibiotics were managed by critical care, hospitalist, or infectious disease services and adjusted once final cultures were returned (Table).

Discussion

Necrotizing infection of the upper extremity is a rare pathology with a substantial risk of amputation and mortality that requires a high index of suspicion and expeditious referral to a hand surgeon. It is well accepted that the key to survival is prompt surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue, ideally within 24 hours of hospital arrival.2-4,6 Death is usually secondary to sepsis.3 The classic presentation of pain out of proportion to exam, hypotension, erythema, skin necrosis, elevated WBC count, and fever may not be present and can delay diagnosis.1-4,6

DM is the most common comorbidity, and reviews have found the disease occurs more often in males, both which are consistent with our study.1-3 Diabetic infections have been found to be more likely to present as necrotizing infection than are nondiabetic infections and be at a higher risk for amputation.7 The patients with the wrist disarticulations and forearm amputation had DM. A minor trauma can be a portal for infection, which can be monomicrobial or polymicrobial.1,4 Once the diagnosis is suspected, prompt resuscitation, surgical debridement, IV antibiotics, and early intensive care are lifesaving. Hyperbaric oxygen is not available at MRVAMC and was not pursued as a transfer request due to its controversial benefit.6

There were no perioperative 30-day mortalities over a 9-year period in patients identified as having necrotizing infection of the upper extremity. This is attributed to an aggressive and well-coordinated, multisystem approach involving emergency, surgical, anesthesia, intensive care, and infectious disease services.

The hand trauma triage system in place at MRVAMC was started in 2008 and presented at the 38th Annual VA Surgeons Meeting in New Haven, Connecticut. The process starts at the level of the ED, urgent care or primary care provider and facilitates rapid access to subspecialty care by reducing unnecessary phone calls and appointment wait times.

All hand emergencies are covered by the plastic surgery service rather than the traditional split coverage between orthopedics and plastic surgery. This provides consistency and continuity for the patients and staff. The electronic health record consult template gives specific instructions to contact the on-call plastic surgeon. The resident/fellow gets called if patient is in-house, and faculty is called if the patient is outside the main hospital. The requesting provider gets instructions on treatment and follow-up. Clinic profiles have appointments reserved for urgent consults during the first hour so that patients can be sent to pre-anesthesia clinic or hand therapy, depending on the diagnosis. This triage system increased our hand trauma volume by a multiple of 6 between 2008 and 2012 but cut the appointment wait time > 1 week by half, as a percentage of consults, and did not significantly increase after-hour use of the operating room. The number of faculty and trainees stayed the same.

We did find that speed to diagnosis for necrotizing infection is an area that can be improved on with a higher clinical suspicion. There is a learning curve to the diagnosis and treatment, which can be prolonged when the index cases do not present themselves often and the patients do not appear in distress. This argues for consistency in hand-specific trauma coverage. The patients were most often initially seen by the resident and examined by a faculty member within hours. There were 4 different plastic surgery faculty involved in these cases, and they all included resident participation before, during, and after surgery. Debridement consists of wide local excision to bleeding tissue. Author review of the operative notes found the numbers of trips to the operating room for debridement can be reduced as the surgeon becomes more confident in the diagnosis and management, resulting in less “whittling” and a more definitive debridement, resulting in a faster recovery.

The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) is a tool that helps to distinguish necrotizing infection from other forms of soft tissue infection by using a point system for laboratory values that include C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose values.8 We do not routinely request CRP results, but 1 of the 2 patients (patient 9) who had the full complement of laboratory tests would have met high-risk criteria. The diagnostic accuracy of this tool has been questioned9; however, the authors welcome any method that can rapidly and noninvasively assist in getting the patient proper attention.

The patients were not seen for long-term follow-up, but some did return to the main hospital or clinic for other pathology and were pleased to show off their grip strength after a 3-ray amputation (patient 1) and aesthetics after upper arm and forearm debridement and skin graft reconstruction (patient 4, Figure 4).

A single-ray amputation can be expected to result in a loss of grip and pinch strength, about 43.3% and 33.6%, respectively; however, given the alternative of further loss of life or limb, this was considered a reasonable trade-off.10 One wrist disarticulation and the forearm amputation were seen by amputee clinic for prosthetic fitting many months after the amputations once the wounds were healed and edema had subsided.

Conclusion

A well-coordinated multidisciplinary effort was the key to successful identification and treatment of this serious life- and limb-threatening infection at our institution. We did identify room for improvement in making an earlier diagnosis and performing a more aggressive first debridement.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Angoules AG, Kontakis G, Drakoulakis E, Vrentzos G, Granick MS, Giannoudis PV. Necrotizing fasciitis of upper and lower limb: a systemic review. Injury. 2007;38(suppl 5):S19-S26.

2. Chauhan A, Wigton MD, Palmer BA. Necrotizing fasciitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(8):1598-1601.

3. Cheng NC, SU YM, Kuo YS, Tai HC, Tang YB. Factors affecting the mortality of necrotizing fasciitis involving the upper extremities. Surg Today. 2008;38(12):1108-1113.

4. Sunderland IR, Friedrich JB. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(10):1900-1901.

5. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

6. Stevens D, Bryant A. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253-2265.

7. Sharma K, Pan D, Friedman J, Yu JL, Mull A, Moore AM. Quantifying the effect of diabetes on surgical hand and forearm infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(2):105-114.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58-65. 10. Bhat AK, Acharya AM, Narayanakurup JK, Kumar B, Nagpal PS, Kamath A. Functional and cosmetic outcome of single-digit ray amputation in hand. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):275-281.

Necrotizing infection of the extremity is a rare but potentially lethal diagnosis with a mortality rate in the range of 17% to 35%.1-4 The plastic surgery service at the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) treats all hand emergencies, including upper extremity infection, in the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Heath System. There has been a well-coordinated emergency hand care system in place for several years that includes specialty templates on the electronic health record, pre-existing urgent clinic appointments, and single service surgical specialty care.5 This facilitates a fluid line of communication between primary care, emergency department (ED) providers, and surgical specialties. The objective of the study was to evaluate our identification, treatment, and outcome of these serious infections.

Methods

The MRVAMC Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective review of necrotizing infection of the upper extremity treated at the facility by the plastic surgery service. Surgical cases over a 9-year period (June 5, 2008-June 5, 2017) were identified by CPT (current procedural technology) codes for amputation and/or debridement of the upper extremity. The charts were reviewed for evidence of necrotizing infection by clinical description or pathology report. The patients’ age, sex, etiology, comorbidities from their problem list, vitals, and laboratory results were recorded upon arrival at the hospital. Time from presentation to surgery, treatment, and outcomes were recorded.

Results

Ten patients were treated for necrotizing infection of the upper extremity over a 9-year period; all were men with an average age of 64 years. Etiologies included nail biting, “bug bites,” crush injuries, burns, suspected IV drug use, and unknown. Nine of 10 patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). Most did not show evidence of hemodynamic instability on hospital arrival (Table). One patient was hypotensive with a mean arterial blood pressure < 65 mm Hg, 2 had heart rates > 100 beats/min, 1 patient had a temperature > 38° C, and 7 had elevated white blood cell (WBC) counts ranging from 11 to 24 k/cmm. Two undiagnosed patients with DM (patients 1 and 8) expressed no complaints of pain and presented with blood glucose > 450 mg/dL with hemoglobin A1c levels > 12%.

Infectious disease and critical care services were involved in the treatment of several cases when requested. A computed tomography (CT) scan was used in 2 of the patients (patients 1 and 4) to assist in the diagnosis (Figure 1).

Seven patients out of 10 were treated with surgery within 24 hours on hospital arrival. The severity of the pathology was not initially recognized in 2 of the patients earlier in the review. A third patient resisted surgical treatment until the second hospital day. Four patients had from 1 to 3 digital amputations, 2 patients had wrist disarticulations, and 1 had a distal forearm amputation.

Antibiotics were managed by critical care, hospitalist, or infectious disease services and adjusted once final cultures were returned (Table).

Discussion

Necrotizing infection of the upper extremity is a rare pathology with a substantial risk of amputation and mortality that requires a high index of suspicion and expeditious referral to a hand surgeon. It is well accepted that the key to survival is prompt surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue, ideally within 24 hours of hospital arrival.2-4,6 Death is usually secondary to sepsis.3 The classic presentation of pain out of proportion to exam, hypotension, erythema, skin necrosis, elevated WBC count, and fever may not be present and can delay diagnosis.1-4,6

DM is the most common comorbidity, and reviews have found the disease occurs more often in males, both which are consistent with our study.1-3 Diabetic infections have been found to be more likely to present as necrotizing infection than are nondiabetic infections and be at a higher risk for amputation.7 The patients with the wrist disarticulations and forearm amputation had DM. A minor trauma can be a portal for infection, which can be monomicrobial or polymicrobial.1,4 Once the diagnosis is suspected, prompt resuscitation, surgical debridement, IV antibiotics, and early intensive care are lifesaving. Hyperbaric oxygen is not available at MRVAMC and was not pursued as a transfer request due to its controversial benefit.6

There were no perioperative 30-day mortalities over a 9-year period in patients identified as having necrotizing infection of the upper extremity. This is attributed to an aggressive and well-coordinated, multisystem approach involving emergency, surgical, anesthesia, intensive care, and infectious disease services.

The hand trauma triage system in place at MRVAMC was started in 2008 and presented at the 38th Annual VA Surgeons Meeting in New Haven, Connecticut. The process starts at the level of the ED, urgent care or primary care provider and facilitates rapid access to subspecialty care by reducing unnecessary phone calls and appointment wait times.

All hand emergencies are covered by the plastic surgery service rather than the traditional split coverage between orthopedics and plastic surgery. This provides consistency and continuity for the patients and staff. The electronic health record consult template gives specific instructions to contact the on-call plastic surgeon. The resident/fellow gets called if patient is in-house, and faculty is called if the patient is outside the main hospital. The requesting provider gets instructions on treatment and follow-up. Clinic profiles have appointments reserved for urgent consults during the first hour so that patients can be sent to pre-anesthesia clinic or hand therapy, depending on the diagnosis. This triage system increased our hand trauma volume by a multiple of 6 between 2008 and 2012 but cut the appointment wait time > 1 week by half, as a percentage of consults, and did not significantly increase after-hour use of the operating room. The number of faculty and trainees stayed the same.

We did find that speed to diagnosis for necrotizing infection is an area that can be improved on with a higher clinical suspicion. There is a learning curve to the diagnosis and treatment, which can be prolonged when the index cases do not present themselves often and the patients do not appear in distress. This argues for consistency in hand-specific trauma coverage. The patients were most often initially seen by the resident and examined by a faculty member within hours. There were 4 different plastic surgery faculty involved in these cases, and they all included resident participation before, during, and after surgery. Debridement consists of wide local excision to bleeding tissue. Author review of the operative notes found the numbers of trips to the operating room for debridement can be reduced as the surgeon becomes more confident in the diagnosis and management, resulting in less “whittling” and a more definitive debridement, resulting in a faster recovery.

The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) is a tool that helps to distinguish necrotizing infection from other forms of soft tissue infection by using a point system for laboratory values that include C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose values.8 We do not routinely request CRP results, but 1 of the 2 patients (patient 9) who had the full complement of laboratory tests would have met high-risk criteria. The diagnostic accuracy of this tool has been questioned9; however, the authors welcome any method that can rapidly and noninvasively assist in getting the patient proper attention.

The patients were not seen for long-term follow-up, but some did return to the main hospital or clinic for other pathology and were pleased to show off their grip strength after a 3-ray amputation (patient 1) and aesthetics after upper arm and forearm debridement and skin graft reconstruction (patient 4, Figure 4).

A single-ray amputation can be expected to result in a loss of grip and pinch strength, about 43.3% and 33.6%, respectively; however, given the alternative of further loss of life or limb, this was considered a reasonable trade-off.10 One wrist disarticulation and the forearm amputation were seen by amputee clinic for prosthetic fitting many months after the amputations once the wounds were healed and edema had subsided.

Conclusion

A well-coordinated multidisciplinary effort was the key to successful identification and treatment of this serious life- and limb-threatening infection at our institution. We did identify room for improvement in making an earlier diagnosis and performing a more aggressive first debridement.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

Necrotizing infection of the extremity is a rare but potentially lethal diagnosis with a mortality rate in the range of 17% to 35%.1-4 The plastic surgery service at the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) treats all hand emergencies, including upper extremity infection, in the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Heath System. There has been a well-coordinated emergency hand care system in place for several years that includes specialty templates on the electronic health record, pre-existing urgent clinic appointments, and single service surgical specialty care.5 This facilitates a fluid line of communication between primary care, emergency department (ED) providers, and surgical specialties. The objective of the study was to evaluate our identification, treatment, and outcome of these serious infections.

Methods

The MRVAMC Institutional Review Board approved a retrospective review of necrotizing infection of the upper extremity treated at the facility by the plastic surgery service. Surgical cases over a 9-year period (June 5, 2008-June 5, 2017) were identified by CPT (current procedural technology) codes for amputation and/or debridement of the upper extremity. The charts were reviewed for evidence of necrotizing infection by clinical description or pathology report. The patients’ age, sex, etiology, comorbidities from their problem list, vitals, and laboratory results were recorded upon arrival at the hospital. Time from presentation to surgery, treatment, and outcomes were recorded.

Results

Ten patients were treated for necrotizing infection of the upper extremity over a 9-year period; all were men with an average age of 64 years. Etiologies included nail biting, “bug bites,” crush injuries, burns, suspected IV drug use, and unknown. Nine of 10 patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). Most did not show evidence of hemodynamic instability on hospital arrival (Table). One patient was hypotensive with a mean arterial blood pressure < 65 mm Hg, 2 had heart rates > 100 beats/min, 1 patient had a temperature > 38° C, and 7 had elevated white blood cell (WBC) counts ranging from 11 to 24 k/cmm. Two undiagnosed patients with DM (patients 1 and 8) expressed no complaints of pain and presented with blood glucose > 450 mg/dL with hemoglobin A1c levels > 12%.

Infectious disease and critical care services were involved in the treatment of several cases when requested. A computed tomography (CT) scan was used in 2 of the patients (patients 1 and 4) to assist in the diagnosis (Figure 1).

Seven patients out of 10 were treated with surgery within 24 hours on hospital arrival. The severity of the pathology was not initially recognized in 2 of the patients earlier in the review. A third patient resisted surgical treatment until the second hospital day. Four patients had from 1 to 3 digital amputations, 2 patients had wrist disarticulations, and 1 had a distal forearm amputation.

Antibiotics were managed by critical care, hospitalist, or infectious disease services and adjusted once final cultures were returned (Table).

Discussion

Necrotizing infection of the upper extremity is a rare pathology with a substantial risk of amputation and mortality that requires a high index of suspicion and expeditious referral to a hand surgeon. It is well accepted that the key to survival is prompt surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue, ideally within 24 hours of hospital arrival.2-4,6 Death is usually secondary to sepsis.3 The classic presentation of pain out of proportion to exam, hypotension, erythema, skin necrosis, elevated WBC count, and fever may not be present and can delay diagnosis.1-4,6

DM is the most common comorbidity, and reviews have found the disease occurs more often in males, both which are consistent with our study.1-3 Diabetic infections have been found to be more likely to present as necrotizing infection than are nondiabetic infections and be at a higher risk for amputation.7 The patients with the wrist disarticulations and forearm amputation had DM. A minor trauma can be a portal for infection, which can be monomicrobial or polymicrobial.1,4 Once the diagnosis is suspected, prompt resuscitation, surgical debridement, IV antibiotics, and early intensive care are lifesaving. Hyperbaric oxygen is not available at MRVAMC and was not pursued as a transfer request due to its controversial benefit.6

There were no perioperative 30-day mortalities over a 9-year period in patients identified as having necrotizing infection of the upper extremity. This is attributed to an aggressive and well-coordinated, multisystem approach involving emergency, surgical, anesthesia, intensive care, and infectious disease services.

The hand trauma triage system in place at MRVAMC was started in 2008 and presented at the 38th Annual VA Surgeons Meeting in New Haven, Connecticut. The process starts at the level of the ED, urgent care or primary care provider and facilitates rapid access to subspecialty care by reducing unnecessary phone calls and appointment wait times.

All hand emergencies are covered by the plastic surgery service rather than the traditional split coverage between orthopedics and plastic surgery. This provides consistency and continuity for the patients and staff. The electronic health record consult template gives specific instructions to contact the on-call plastic surgeon. The resident/fellow gets called if patient is in-house, and faculty is called if the patient is outside the main hospital. The requesting provider gets instructions on treatment and follow-up. Clinic profiles have appointments reserved for urgent consults during the first hour so that patients can be sent to pre-anesthesia clinic or hand therapy, depending on the diagnosis. This triage system increased our hand trauma volume by a multiple of 6 between 2008 and 2012 but cut the appointment wait time > 1 week by half, as a percentage of consults, and did not significantly increase after-hour use of the operating room. The number of faculty and trainees stayed the same.

We did find that speed to diagnosis for necrotizing infection is an area that can be improved on with a higher clinical suspicion. There is a learning curve to the diagnosis and treatment, which can be prolonged when the index cases do not present themselves often and the patients do not appear in distress. This argues for consistency in hand-specific trauma coverage. The patients were most often initially seen by the resident and examined by a faculty member within hours. There were 4 different plastic surgery faculty involved in these cases, and they all included resident participation before, during, and after surgery. Debridement consists of wide local excision to bleeding tissue. Author review of the operative notes found the numbers of trips to the operating room for debridement can be reduced as the surgeon becomes more confident in the diagnosis and management, resulting in less “whittling” and a more definitive debridement, resulting in a faster recovery.

The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) is a tool that helps to distinguish necrotizing infection from other forms of soft tissue infection by using a point system for laboratory values that include C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose values.8 We do not routinely request CRP results, but 1 of the 2 patients (patient 9) who had the full complement of laboratory tests would have met high-risk criteria. The diagnostic accuracy of this tool has been questioned9; however, the authors welcome any method that can rapidly and noninvasively assist in getting the patient proper attention.

The patients were not seen for long-term follow-up, but some did return to the main hospital or clinic for other pathology and were pleased to show off their grip strength after a 3-ray amputation (patient 1) and aesthetics after upper arm and forearm debridement and skin graft reconstruction (patient 4, Figure 4).

A single-ray amputation can be expected to result in a loss of grip and pinch strength, about 43.3% and 33.6%, respectively; however, given the alternative of further loss of life or limb, this was considered a reasonable trade-off.10 One wrist disarticulation and the forearm amputation were seen by amputee clinic for prosthetic fitting many months after the amputations once the wounds were healed and edema had subsided.

Conclusion

A well-coordinated multidisciplinary effort was the key to successful identification and treatment of this serious life- and limb-threatening infection at our institution. We did identify room for improvement in making an earlier diagnosis and performing a more aggressive first debridement.

Acknowledgments

This project is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Angoules AG, Kontakis G, Drakoulakis E, Vrentzos G, Granick MS, Giannoudis PV. Necrotizing fasciitis of upper and lower limb: a systemic review. Injury. 2007;38(suppl 5):S19-S26.

2. Chauhan A, Wigton MD, Palmer BA. Necrotizing fasciitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(8):1598-1601.

3. Cheng NC, SU YM, Kuo YS, Tai HC, Tang YB. Factors affecting the mortality of necrotizing fasciitis involving the upper extremities. Surg Today. 2008;38(12):1108-1113.

4. Sunderland IR, Friedrich JB. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(10):1900-1901.

5. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

6. Stevens D, Bryant A. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253-2265.

7. Sharma K, Pan D, Friedman J, Yu JL, Mull A, Moore AM. Quantifying the effect of diabetes on surgical hand and forearm infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(2):105-114.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58-65. 10. Bhat AK, Acharya AM, Narayanakurup JK, Kumar B, Nagpal PS, Kamath A. Functional and cosmetic outcome of single-digit ray amputation in hand. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):275-281.

1. Angoules AG, Kontakis G, Drakoulakis E, Vrentzos G, Granick MS, Giannoudis PV. Necrotizing fasciitis of upper and lower limb: a systemic review. Injury. 2007;38(suppl 5):S19-S26.

2. Chauhan A, Wigton MD, Palmer BA. Necrotizing fasciitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(8):1598-1601.

3. Cheng NC, SU YM, Kuo YS, Tai HC, Tang YB. Factors affecting the mortality of necrotizing fasciitis involving the upper extremities. Surg Today. 2008;38(12):1108-1113.

4. Sunderland IR, Friedrich JB. Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(10):1900-1901.

5. Coady-Fariborzian L, McGreane A. Comparison of hand emergency triage before and after specialty templates (2007 vs 2012). Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):215-220.

6. Stevens D, Bryant A. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253-2265.

7. Sharma K, Pan D, Friedman J, Yu JL, Mull A, Moore AM. Quantifying the effect of diabetes on surgical hand and forearm infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(2):105-114.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infection: diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, imaging, and LRINEC score: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58-65. 10. Bhat AK, Acharya AM, Narayanakurup JK, Kumar B, Nagpal PS, Kamath A. Functional and cosmetic outcome of single-digit ray amputation in hand. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):275-281.

Rare Neurological Disease Special Report

The 5th annual Rare Neurological Disease Special Report covers a wide range of topics related to rare neurological diseases. Nearly 20 bylined articles include overviews of specific diseases, discussions of translational science, reports on trends in diagnosis and screening, advice on resources for health care professionals, snapshots of emerging therapies, and more. This year’s issue has a special focus on genetics and the potential for genetic therapy to transform the treatment of rare diseases.

The 5th annual Rare Neurological Disease Special Report covers a wide range of topics related to rare neurological diseases. Nearly 20 bylined articles include overviews of specific diseases, discussions of translational science, reports on trends in diagnosis and screening, advice on resources for health care professionals, snapshots of emerging therapies, and more. This year’s issue has a special focus on genetics and the potential for genetic therapy to transform the treatment of rare diseases.

The 5th annual Rare Neurological Disease Special Report covers a wide range of topics related to rare neurological diseases. Nearly 20 bylined articles include overviews of specific diseases, discussions of translational science, reports on trends in diagnosis and screening, advice on resources for health care professionals, snapshots of emerging therapies, and more. This year’s issue has a special focus on genetics and the potential for genetic therapy to transform the treatment of rare diseases.

BTK inhibitor calms pemphigus vulgaris with low-dose steroids

WASHINGTON – An investigational molecule that blocks the downstream proinflammatory effects of B cells controlled disease activity and induced clinical remission in patients with pemphigus by 12 weeks.

At the end of a 24-week, open-label trial, a key driver of the sometimes-fatal blistering disease, Deedee Murrell, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The clinical efficacy plus a favorable safety profile supports the further development of the molecule, designed and manufactured by Principia Biopharma in San Francisco. The company is currently recruiting for a pivotal phase 3 trial of PRN1008 in 120 patients with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris.

Despite the recent approval of rituximab (Rituxan) for moderate to severe pemphigus, there remains an unmet need for a quick-acting, steroid-sparing, anti-inflammatory treatment, said Dr. Murrell, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

“We need something to use instead of high-dose steroids while we are waiting for rituximab to kick in, which can take 3 months,” and rituximab, which depletes B cells, puts patients at risk for infection, she said. “We need something that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing, safe for chronic administration, avoids B-cell depletion, and is convenient.”

Blocking the BTK receptor on B cells puts the brakes on the B-cell mediated inflammatory pathway, preventing activation of monocytes, macrophages, mast cells, basophils, and neutrophils. At the same time, however, it does not deplete the B-cell population, said Dr. Murrell, the lead investigator.

The BELIEVE study comprised 27 patients with mild to severe pemphigus of an average 6 years’ duration. Most (18) had relapsing disease; the remainder had newly diagnosed pemphigus. A majority (16) had severe disease, as measured by a score of 15 or more on the Pemphigus Disease Activity Index (PDAI). Almost all (23) were positive for antidesmoglein antibodies. Only one patient was negative for antibodies.

The mean corticosteroid dose at baseline was 14 mg/day, although that ranged from no steroids to 30 mg/day.

The study consisted of a 12-week treatment phase and a 12-week follow-up phase. During treatment, patients could take no more than 0.5 mg/kg of prednisone daily, although with 400 mg PRN1008 twice a day. They were allowed to undertake rescue immunosuppression if they experienced a disease flare.

The primary endpoint was disease control by day 29 as evidenced by no new lesions. Secondary endpoints were complete remission, minimization of prednisone, quality of life, antibody levels, and clinician measures including the PDAI and the Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score.

By the end of week 4, 54% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint. The benefit continued to expand, with 73% reaching that response by the end of week 12. During this period, the mean prednisone dose was 12 mg/day.

Among the 24 patients who completed the study, complete remission occurred in 17% by week 12. However, patients continued to respond through the follow-up period, even after the study medication was stopped. By week 24, 25% of these patients experienced a complete remission. At the point of remission, the mean steroid dose was 8 mg/day. The median duration of remission was 2 months after stopping PRN1008.

The PDAI fell by a median of 70% by week 12 and was maintained at that level by the end of week 24. The median level of antidesmoglein autoantibodies fell by up to 65%. Again, the improvement continued throughout the off-drug follow-up period. In subgroup analyses, PRN1008 was more effective in patients with moderate to severe disease than those with mild disease (80% response vs. 64%). It was equally effective in those with newly diagnosed disease (75% vs. 72%) and regardless of antibody level at baseline.

The adverse event profile was relatively benign. Most side effects were mild and transient, and included upper abdominal pain, headache, and nausea. There were two mild infections and one serious infection, which presented in a patient with a long-standing localized cellulitis that activated and was associated a high fever. It was culture negative and PRN1008 was restarted without issue.

There was also one serious adverse event and one death, both unrelated to the study drug. One patient developed a pancreatic cyst that was discovered on day 29. The patient dropped out of the study to have elective surgery. The death occurred in a patient who developed acute respiratory failure on day 8 of treatment, caused by an undiagnosed congenital pulmonary sequestration. The patient died of a brain embolism shortly after lung surgery.

Dr. Murrell designed the study and was an investigator. She reported a financial relationship with Principia, as well as with numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – An investigational molecule that blocks the downstream proinflammatory effects of B cells controlled disease activity and induced clinical remission in patients with pemphigus by 12 weeks.

At the end of a 24-week, open-label trial, a key driver of the sometimes-fatal blistering disease, Deedee Murrell, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The clinical efficacy plus a favorable safety profile supports the further development of the molecule, designed and manufactured by Principia Biopharma in San Francisco. The company is currently recruiting for a pivotal phase 3 trial of PRN1008 in 120 patients with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris.

Despite the recent approval of rituximab (Rituxan) for moderate to severe pemphigus, there remains an unmet need for a quick-acting, steroid-sparing, anti-inflammatory treatment, said Dr. Murrell, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

“We need something to use instead of high-dose steroids while we are waiting for rituximab to kick in, which can take 3 months,” and rituximab, which depletes B cells, puts patients at risk for infection, she said. “We need something that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing, safe for chronic administration, avoids B-cell depletion, and is convenient.”

Blocking the BTK receptor on B cells puts the brakes on the B-cell mediated inflammatory pathway, preventing activation of monocytes, macrophages, mast cells, basophils, and neutrophils. At the same time, however, it does not deplete the B-cell population, said Dr. Murrell, the lead investigator.

The BELIEVE study comprised 27 patients with mild to severe pemphigus of an average 6 years’ duration. Most (18) had relapsing disease; the remainder had newly diagnosed pemphigus. A majority (16) had severe disease, as measured by a score of 15 or more on the Pemphigus Disease Activity Index (PDAI). Almost all (23) were positive for antidesmoglein antibodies. Only one patient was negative for antibodies.

The mean corticosteroid dose at baseline was 14 mg/day, although that ranged from no steroids to 30 mg/day.

The study consisted of a 12-week treatment phase and a 12-week follow-up phase. During treatment, patients could take no more than 0.5 mg/kg of prednisone daily, although with 400 mg PRN1008 twice a day. They were allowed to undertake rescue immunosuppression if they experienced a disease flare.

The primary endpoint was disease control by day 29 as evidenced by no new lesions. Secondary endpoints were complete remission, minimization of prednisone, quality of life, antibody levels, and clinician measures including the PDAI and the Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score.

By the end of week 4, 54% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint. The benefit continued to expand, with 73% reaching that response by the end of week 12. During this period, the mean prednisone dose was 12 mg/day.

Among the 24 patients who completed the study, complete remission occurred in 17% by week 12. However, patients continued to respond through the follow-up period, even after the study medication was stopped. By week 24, 25% of these patients experienced a complete remission. At the point of remission, the mean steroid dose was 8 mg/day. The median duration of remission was 2 months after stopping PRN1008.

The PDAI fell by a median of 70% by week 12 and was maintained at that level by the end of week 24. The median level of antidesmoglein autoantibodies fell by up to 65%. Again, the improvement continued throughout the off-drug follow-up period. In subgroup analyses, PRN1008 was more effective in patients with moderate to severe disease than those with mild disease (80% response vs. 64%). It was equally effective in those with newly diagnosed disease (75% vs. 72%) and regardless of antibody level at baseline.

The adverse event profile was relatively benign. Most side effects were mild and transient, and included upper abdominal pain, headache, and nausea. There were two mild infections and one serious infection, which presented in a patient with a long-standing localized cellulitis that activated and was associated a high fever. It was culture negative and PRN1008 was restarted without issue.

There was also one serious adverse event and one death, both unrelated to the study drug. One patient developed a pancreatic cyst that was discovered on day 29. The patient dropped out of the study to have elective surgery. The death occurred in a patient who developed acute respiratory failure on day 8 of treatment, caused by an undiagnosed congenital pulmonary sequestration. The patient died of a brain embolism shortly after lung surgery.

Dr. Murrell designed the study and was an investigator. She reported a financial relationship with Principia, as well as with numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – An investigational molecule that blocks the downstream proinflammatory effects of B cells controlled disease activity and induced clinical remission in patients with pemphigus by 12 weeks.

At the end of a 24-week, open-label trial, a key driver of the sometimes-fatal blistering disease, Deedee Murrell, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The clinical efficacy plus a favorable safety profile supports the further development of the molecule, designed and manufactured by Principia Biopharma in San Francisco. The company is currently recruiting for a pivotal phase 3 trial of PRN1008 in 120 patients with moderate to severe pemphigus vulgaris.

Despite the recent approval of rituximab (Rituxan) for moderate to severe pemphigus, there remains an unmet need for a quick-acting, steroid-sparing, anti-inflammatory treatment, said Dr. Murrell, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

“We need something to use instead of high-dose steroids while we are waiting for rituximab to kick in, which can take 3 months,” and rituximab, which depletes B cells, puts patients at risk for infection, she said. “We need something that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing, safe for chronic administration, avoids B-cell depletion, and is convenient.”

Blocking the BTK receptor on B cells puts the brakes on the B-cell mediated inflammatory pathway, preventing activation of monocytes, macrophages, mast cells, basophils, and neutrophils. At the same time, however, it does not deplete the B-cell population, said Dr. Murrell, the lead investigator.

The BELIEVE study comprised 27 patients with mild to severe pemphigus of an average 6 years’ duration. Most (18) had relapsing disease; the remainder had newly diagnosed pemphigus. A majority (16) had severe disease, as measured by a score of 15 or more on the Pemphigus Disease Activity Index (PDAI). Almost all (23) were positive for antidesmoglein antibodies. Only one patient was negative for antibodies.

The mean corticosteroid dose at baseline was 14 mg/day, although that ranged from no steroids to 30 mg/day.

The study consisted of a 12-week treatment phase and a 12-week follow-up phase. During treatment, patients could take no more than 0.5 mg/kg of prednisone daily, although with 400 mg PRN1008 twice a day. They were allowed to undertake rescue immunosuppression if they experienced a disease flare.

The primary endpoint was disease control by day 29 as evidenced by no new lesions. Secondary endpoints were complete remission, minimization of prednisone, quality of life, antibody levels, and clinician measures including the PDAI and the Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score.

By the end of week 4, 54% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint. The benefit continued to expand, with 73% reaching that response by the end of week 12. During this period, the mean prednisone dose was 12 mg/day.

Among the 24 patients who completed the study, complete remission occurred in 17% by week 12. However, patients continued to respond through the follow-up period, even after the study medication was stopped. By week 24, 25% of these patients experienced a complete remission. At the point of remission, the mean steroid dose was 8 mg/day. The median duration of remission was 2 months after stopping PRN1008.

The PDAI fell by a median of 70% by week 12 and was maintained at that level by the end of week 24. The median level of antidesmoglein autoantibodies fell by up to 65%. Again, the improvement continued throughout the off-drug follow-up period. In subgroup analyses, PRN1008 was more effective in patients with moderate to severe disease than those with mild disease (80% response vs. 64%). It was equally effective in those with newly diagnosed disease (75% vs. 72%) and regardless of antibody level at baseline.

The adverse event profile was relatively benign. Most side effects were mild and transient, and included upper abdominal pain, headache, and nausea. There were two mild infections and one serious infection, which presented in a patient with a long-standing localized cellulitis that activated and was associated a high fever. It was culture negative and PRN1008 was restarted without issue.

There was also one serious adverse event and one death, both unrelated to the study drug. One patient developed a pancreatic cyst that was discovered on day 29. The patient dropped out of the study to have elective surgery. The death occurred in a patient who developed acute respiratory failure on day 8 of treatment, caused by an undiagnosed congenital pulmonary sequestration. The patient died of a brain embolism shortly after lung surgery.

Dr. Murrell designed the study and was an investigator. She reported a financial relationship with Principia, as well as with numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Murrell D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

Histoplasmosis Manifests After Decades

Immunocompromised patients can be at risk for complications long after the original health issue was resolved—a problem illustrated by a patient who had a heart transplant in 1986 but developed acute progressive disseminated histoplasmosis decades later.

The patient presented with altered mental status; a Mini-Mental State Exam showed confusion. A computed tomography scan of the patient’s head revealed lesions, raising the suspicion of metastatic malignancy, which was ruled out after biopsy of a medial right temporal brain lesion. MRIs of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed bilateral masses on his adrenal glands. Guided adrenal biopsy showed necrotizing granulomas consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis.

However, that diagnosis was questioned—the patient had lived in Arizona for years, not, for instance, the Midwest, where histoplasmosis is more common. Nor did he have a history of spelunking, prior exposure to bird or bat droppings. He did report a short visit to North Carolina 30 years earlier. And he had been on immunosuppressive drugs for years.

The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B, which was discontinued when his renal function deteriorated. He was switched to itraconazole, then restarted on amphotericin B with close monitoring after the diagnosis was confirmed. His doses of immunosuppressive drugs were reduced.

The clinicians note that HIV/AIDS and use of immunosuppressive drugs are among the risk factors for disseminated infection. They cite 1 study that found immunosuppression was the single most common risk factor. In another study, the risk of histoplasmosis increased as CD4+ T cells dropped below 300/µL.

The patient’s case was complicated by the fact that it was > 30 years after his heart transplant, and he had made only a short visit to an endemic area. He also had no history of histoplasmosis—the clinicians say a database search turned up the fact that most reported cases were preceded by symptomatic infection.

When charting patient history, they advise placing emphasis on a history of travel to endemic areas and considering histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients in nonendemic areas.

Immunocompromised patients can be at risk for complications long after the original health issue was resolved—a problem illustrated by a patient who had a heart transplant in 1986 but developed acute progressive disseminated histoplasmosis decades later.

The patient presented with altered mental status; a Mini-Mental State Exam showed confusion. A computed tomography scan of the patient’s head revealed lesions, raising the suspicion of metastatic malignancy, which was ruled out after biopsy of a medial right temporal brain lesion. MRIs of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed bilateral masses on his adrenal glands. Guided adrenal biopsy showed necrotizing granulomas consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis.

However, that diagnosis was questioned—the patient had lived in Arizona for years, not, for instance, the Midwest, where histoplasmosis is more common. Nor did he have a history of spelunking, prior exposure to bird or bat droppings. He did report a short visit to North Carolina 30 years earlier. And he had been on immunosuppressive drugs for years.

The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B, which was discontinued when his renal function deteriorated. He was switched to itraconazole, then restarted on amphotericin B with close monitoring after the diagnosis was confirmed. His doses of immunosuppressive drugs were reduced.

The clinicians note that HIV/AIDS and use of immunosuppressive drugs are among the risk factors for disseminated infection. They cite 1 study that found immunosuppression was the single most common risk factor. In another study, the risk of histoplasmosis increased as CD4+ T cells dropped below 300/µL.

The patient’s case was complicated by the fact that it was > 30 years after his heart transplant, and he had made only a short visit to an endemic area. He also had no history of histoplasmosis—the clinicians say a database search turned up the fact that most reported cases were preceded by symptomatic infection.

When charting patient history, they advise placing emphasis on a history of travel to endemic areas and considering histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients in nonendemic areas.

Immunocompromised patients can be at risk for complications long after the original health issue was resolved—a problem illustrated by a patient who had a heart transplant in 1986 but developed acute progressive disseminated histoplasmosis decades later.

The patient presented with altered mental status; a Mini-Mental State Exam showed confusion. A computed tomography scan of the patient’s head revealed lesions, raising the suspicion of metastatic malignancy, which was ruled out after biopsy of a medial right temporal brain lesion. MRIs of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed bilateral masses on his adrenal glands. Guided adrenal biopsy showed necrotizing granulomas consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis.

However, that diagnosis was questioned—the patient had lived in Arizona for years, not, for instance, the Midwest, where histoplasmosis is more common. Nor did he have a history of spelunking, prior exposure to bird or bat droppings. He did report a short visit to North Carolina 30 years earlier. And he had been on immunosuppressive drugs for years.

The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B, which was discontinued when his renal function deteriorated. He was switched to itraconazole, then restarted on amphotericin B with close monitoring after the diagnosis was confirmed. His doses of immunosuppressive drugs were reduced.

The clinicians note that HIV/AIDS and use of immunosuppressive drugs are among the risk factors for disseminated infection. They cite 1 study that found immunosuppression was the single most common risk factor. In another study, the risk of histoplasmosis increased as CD4+ T cells dropped below 300/µL.

The patient’s case was complicated by the fact that it was > 30 years after his heart transplant, and he had made only a short visit to an endemic area. He also had no history of histoplasmosis—the clinicians say a database search turned up the fact that most reported cases were preceded by symptomatic infection.

When charting patient history, they advise placing emphasis on a history of travel to endemic areas and considering histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients in nonendemic areas.

Lentiviral gene therapy appears effective in X-CGD

HOUSTON – , said Donald B. Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Seven of nine patients treated were “alive and well” at 12 months’ follow-up after receiving lentiviral vector transduced CD34+ cells, Dr. Kohn reported in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings.

Most patients were able to discontinue antibiotic prophylaxis for this disease, which is associated with severe, recurrent, and prolonged life-threatening infections, he said.

Results of the small study provide “proof of concept” for use of the gene therapy in the disease, though additional studies are needed to formally assess the clinical safety and efficacy of the approach, he said.

The estimated incidence of chronic granulomatous disease is 1 in 200,000 births in the United States, and the X-linked form is most common, occurring in about 60% of patients, Dr. Kohn told attendees of the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Most of these patients are treated with antibacterial or antifungal prophylaxis. While allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is also an option, according to Dr. Kohn, the approach is limited by a lack of matched donors and graft-versus-host disease.

Dr. Kohn reported results for nine patients in the United States and the United Kingdom who were treated with the same G1XCGD lentiviral vector. The patients, who ranged in age from 2 to 27 years, underwent CD34+ cell mobilization or bone marrow isolation, transduction with the lentiviral vector, busulfan conditioning, and autologous transplantation.

All patients had confirmed X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, and had had at least one severe infection or inflammatory complication requiring hospitalization.

There were no infusion-related adverse events, and one serious adverse event, which was an inflammatory syndrome that resolved with steroids. Two patients died from complications unrelated to gene therapy, Dr. Kohn reported.

“The other patients are basically doing quite well,” he said.

Of the seven patients alive at the 12-month follow up, six were reported as “clinically well” and off antibiotic prophylaxis, according to Dr. Kohn, while the seventh patient was clinically well and receiving antimicrobial support.

Dr. Kohn is a scientific advisory board member for Orchard Therapeutics, which licensed the lentiviral gene therapy for X-CGD discussed in his presentation. He is also an inventor of intellectual property related to the therapy that UCLA has licensed to Orchard.

At its meeting, the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation announced a new name for the society: American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT).

SOURCE: Kohn DB et al. TCT 2019, Abstract LBA1.

HOUSTON – , said Donald B. Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Seven of nine patients treated were “alive and well” at 12 months’ follow-up after receiving lentiviral vector transduced CD34+ cells, Dr. Kohn reported in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings.

Most patients were able to discontinue antibiotic prophylaxis for this disease, which is associated with severe, recurrent, and prolonged life-threatening infections, he said.

Results of the small study provide “proof of concept” for use of the gene therapy in the disease, though additional studies are needed to formally assess the clinical safety and efficacy of the approach, he said.

The estimated incidence of chronic granulomatous disease is 1 in 200,000 births in the United States, and the X-linked form is most common, occurring in about 60% of patients, Dr. Kohn told attendees of the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Most of these patients are treated with antibacterial or antifungal prophylaxis. While allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is also an option, according to Dr. Kohn, the approach is limited by a lack of matched donors and graft-versus-host disease.

Dr. Kohn reported results for nine patients in the United States and the United Kingdom who were treated with the same G1XCGD lentiviral vector. The patients, who ranged in age from 2 to 27 years, underwent CD34+ cell mobilization or bone marrow isolation, transduction with the lentiviral vector, busulfan conditioning, and autologous transplantation.

All patients had confirmed X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, and had had at least one severe infection or inflammatory complication requiring hospitalization.

There were no infusion-related adverse events, and one serious adverse event, which was an inflammatory syndrome that resolved with steroids. Two patients died from complications unrelated to gene therapy, Dr. Kohn reported.

“The other patients are basically doing quite well,” he said.

Of the seven patients alive at the 12-month follow up, six were reported as “clinically well” and off antibiotic prophylaxis, according to Dr. Kohn, while the seventh patient was clinically well and receiving antimicrobial support.

Dr. Kohn is a scientific advisory board member for Orchard Therapeutics, which licensed the lentiviral gene therapy for X-CGD discussed in his presentation. He is also an inventor of intellectual property related to the therapy that UCLA has licensed to Orchard.

At its meeting, the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation announced a new name for the society: American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT).

SOURCE: Kohn DB et al. TCT 2019, Abstract LBA1.

HOUSTON – , said Donald B. Kohn, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Seven of nine patients treated were “alive and well” at 12 months’ follow-up after receiving lentiviral vector transduced CD34+ cells, Dr. Kohn reported in a late-breaking clinical trial session at the Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings.

Most patients were able to discontinue antibiotic prophylaxis for this disease, which is associated with severe, recurrent, and prolonged life-threatening infections, he said.

Results of the small study provide “proof of concept” for use of the gene therapy in the disease, though additional studies are needed to formally assess the clinical safety and efficacy of the approach, he said.

The estimated incidence of chronic granulomatous disease is 1 in 200,000 births in the United States, and the X-linked form is most common, occurring in about 60% of patients, Dr. Kohn told attendees of the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Most of these patients are treated with antibacterial or antifungal prophylaxis. While allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is also an option, according to Dr. Kohn, the approach is limited by a lack of matched donors and graft-versus-host disease.

Dr. Kohn reported results for nine patients in the United States and the United Kingdom who were treated with the same G1XCGD lentiviral vector. The patients, who ranged in age from 2 to 27 years, underwent CD34+ cell mobilization or bone marrow isolation, transduction with the lentiviral vector, busulfan conditioning, and autologous transplantation.

All patients had confirmed X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, and had had at least one severe infection or inflammatory complication requiring hospitalization.

There were no infusion-related adverse events, and one serious adverse event, which was an inflammatory syndrome that resolved with steroids. Two patients died from complications unrelated to gene therapy, Dr. Kohn reported.

“The other patients are basically doing quite well,” he said.

Of the seven patients alive at the 12-month follow up, six were reported as “clinically well” and off antibiotic prophylaxis, according to Dr. Kohn, while the seventh patient was clinically well and receiving antimicrobial support.

Dr. Kohn is a scientific advisory board member for Orchard Therapeutics, which licensed the lentiviral gene therapy for X-CGD discussed in his presentation. He is also an inventor of intellectual property related to the therapy that UCLA has licensed to Orchard.

At its meeting, the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation announced a new name for the society: American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT).

SOURCE: Kohn DB et al. TCT 2019, Abstract LBA1.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2019

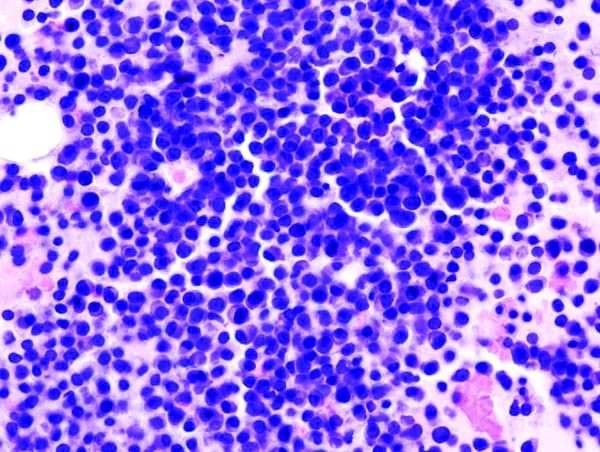

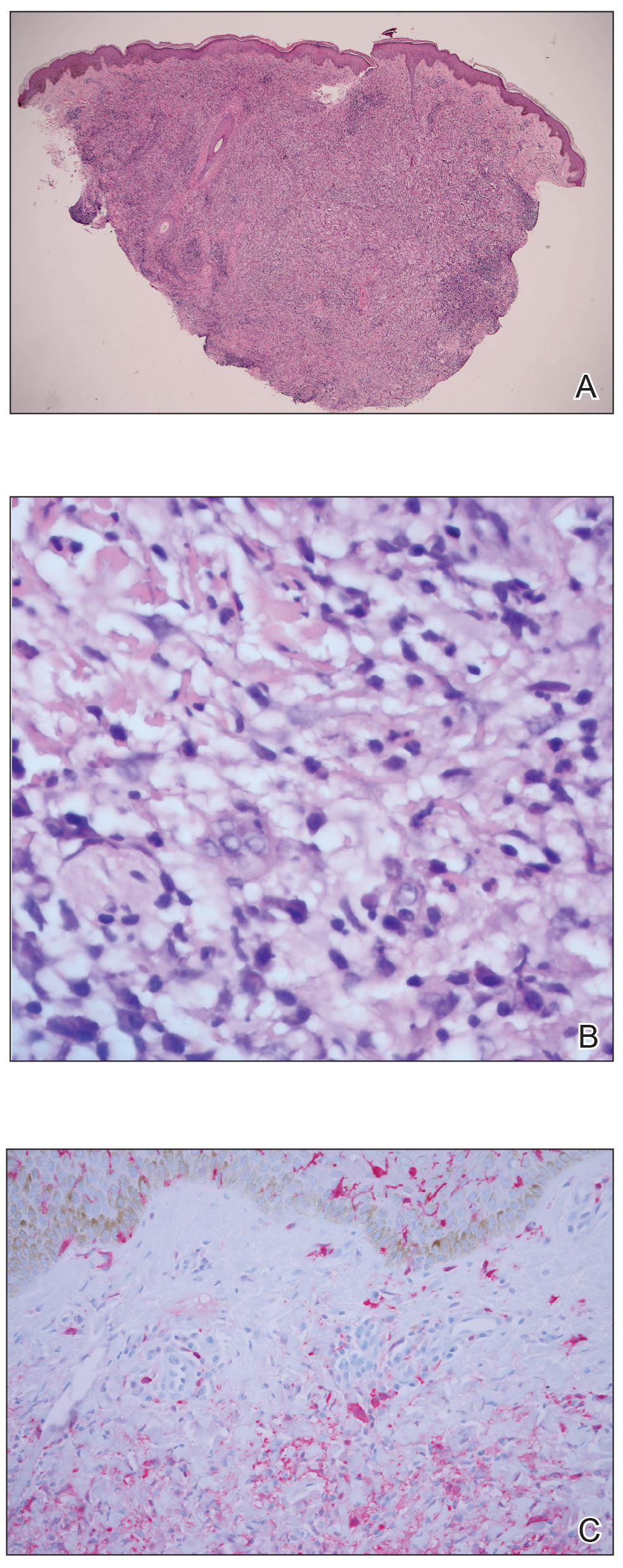

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Case Report

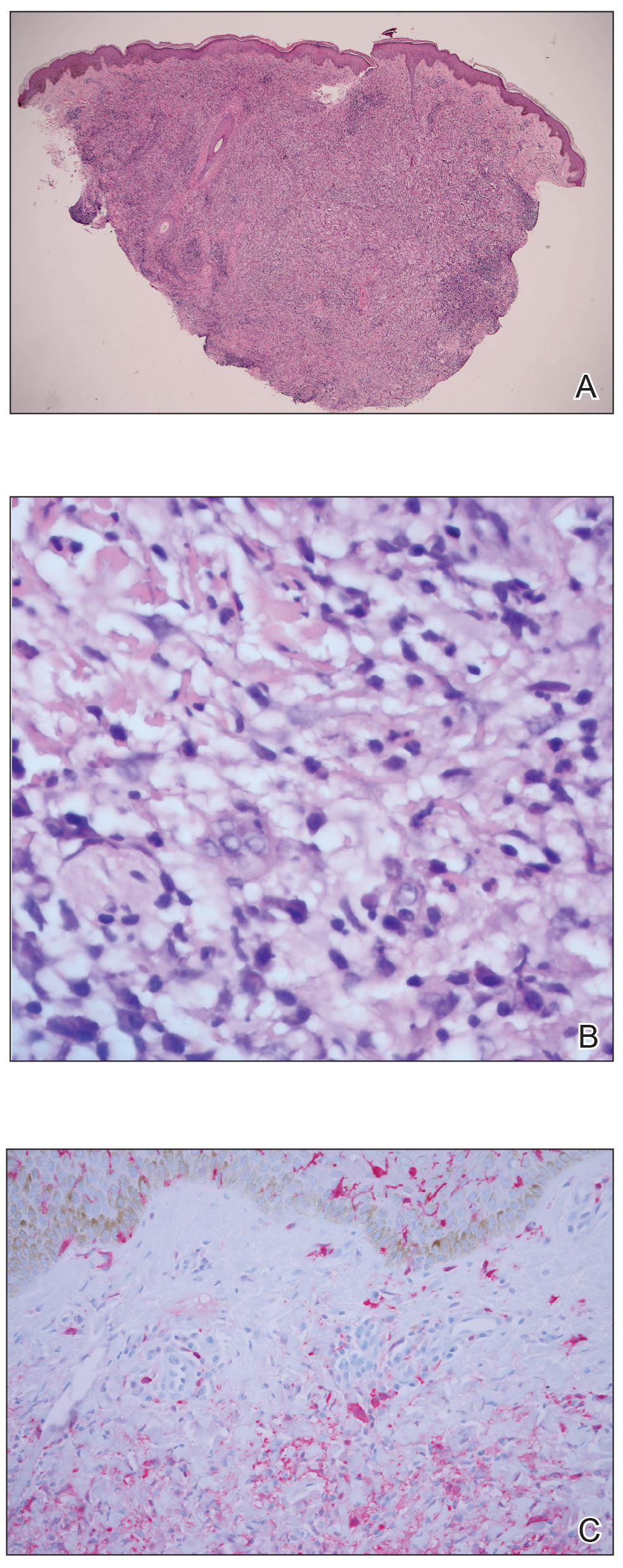

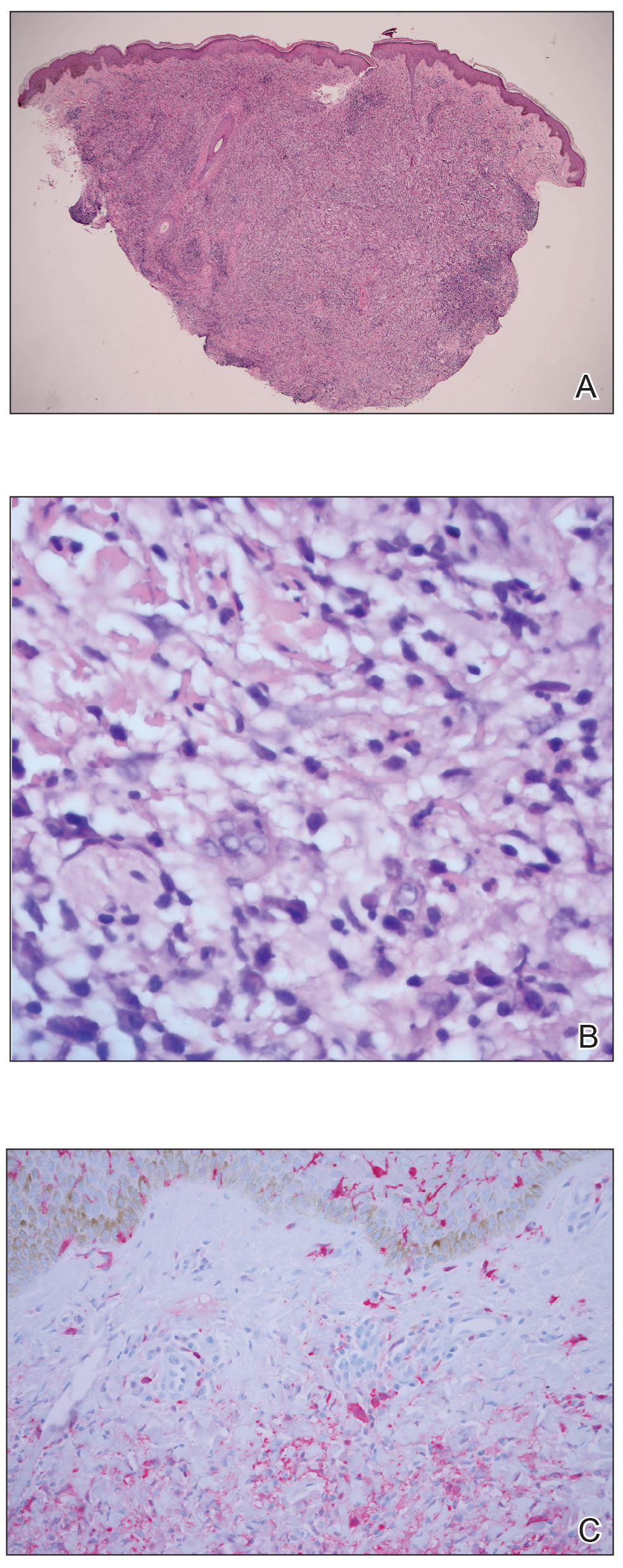

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology