User login

Using telehealth to deliver palliative care to cancer patients

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM ASCO QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM 2020

GLIMMER of hope for itch in primary biliary cholangitis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

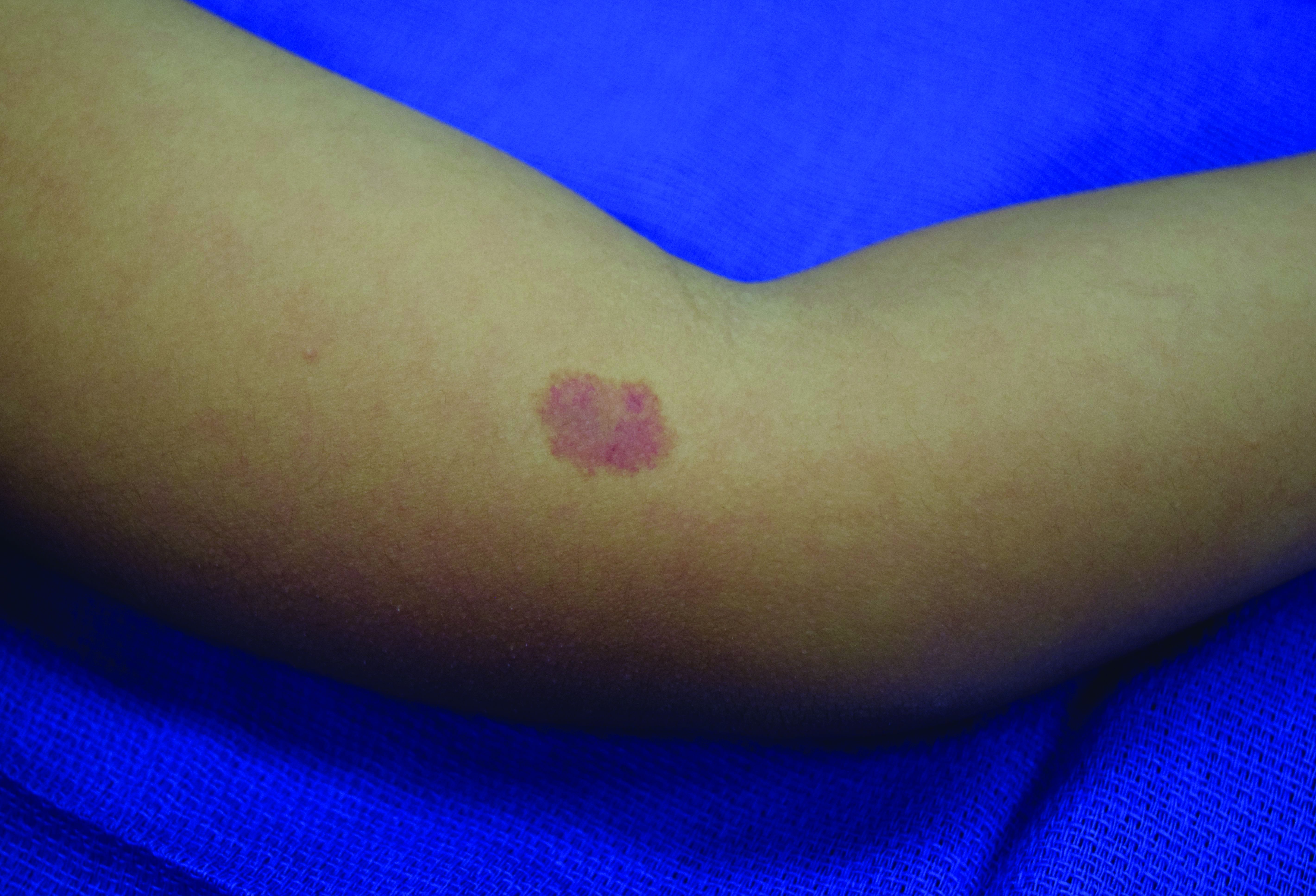

A 4-year-old presented to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of asymptomatic "brown spots."

Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome

with or without arteriovenous malformations, as well as arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). CM-AVM is an autosomal dominant disorder.1 CM-AVM type 1 is caused by mutations in the RASA1 gene, and CM-AVM type 2 is caused by mutations in the EPHB4 gene.2 Approximately 70% of patients with RASA1-associated CM-AVM syndrome and 80% of patients with EPHB4-associated CM-AVM syndrome have an affected parent, while the remainder have de novo variants.1

In patients with CM-AVM syndrome, CMs are often present at birth and more are typically acquired over time. CMs are characteristically 1-3 cm in diameter, round or oval, dull red or red-brown macules and patches with a blanched halo.3 Some CMs may be warm to touch indicating a possible underlying AVM or AVF.4 This can be confirmed by Doppler ultrasound, which would demonstrate increased arterial flow.4 CMs are most commonly located on the face and limbs and may present in isolation, but approximately one-third of patients have associated AVMs and AVFs.1,5 These high-flow vascular malformations may be present in skin, muscle, bone, brain, and/or spine and may be asymptomatic or lead to serious sequelae, including bleeding, congestive heart failure, and neurologic complications, such as migraine headaches, seizures, or even stroke.5 Symptoms from intracranial and spinal high-flow lesions usually present in early childhood and affect approximately 7% of patients.3

The diagnosis of CM-AVM should be suspected in an individual with numerous characteristic CMs and may be supported by the presence of AVMs and AVFs, family history of CM-AVM, and/or identification of RASA1 or EPHB4 mutation by molecular genetic testing.1,3 Although there are no consensus protocols for imaging CM-AVM patients, MRI of the brain and spine is recommended at diagnosis to identify underlying high-flow lesions.1 This may allow for early treatment before the development of symptoms.1 Any lesions identified on screening imaging may require regular surveillance, which is best determined by discussion with the radiologist.1 Although there are no reports of patients with negative results on screening imaging who later develop AVMs or AVFs, there should be a low threshold for repeat imaging in patients who develop new symptoms or physical exam findings.3,4

It has previously been suggested that the CMs in CM-AVM may actually represent early or small AVMs and pulsed-dye laser (PDL) treatment was not recommended because of concern for potential progression of lesions.4 However, a recent study demonstrated good response to PDL in patients with CM-AVM with no evidence of worsening or recurrence of lesions with long-term follow-up.6 Treatment of CMs that cause cosmetic concerns may be considered following discussion of risks and benefits with a dermatologist. Management of AVMs and AVFs requires a multidisciplinary team that, depending on location and symptoms of these features, may require the expertise of specialists such as neurosurgery, surgery, orthopedics, cardiology, and/or interventional radiology.1

Given the suspicion for CM-AVM in our patient, further workup was completed. A skin biopsy was consistent with CM. Genetic testing with the Vascular Malformations Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication revealed a pathogenic variant in the RASA1 gene and a variant of unknown clinical significance in the TEK gene. Parental genetic testing for the RASA1 mutation was negative, supporting a de novo mutation in the patient. CNS imaging showed a small developmental venous malformation in the brain that neurosurgery did not think was clinically significant. At the most recent follow-up at age 8 years, our patient had developed a few new small CMs but was otherwise well.

Dr. Leszczynska is trained in pediatrics and is the current dermatology research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Croce is a dermatology-trained pediatric nurse practitioner and PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing. Dr. Diaz is chief of pediatric dermatology at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, assistant professor of pediatrics and medicine (dermatology), and dermatology residency associate program director at University of Texas at Austin . The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is the editor of this column.

References

1. Bayrak-Toydemir P, Stevenson D. Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; February 22, 2011.

2.Yu J et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Sep;34(5):e227-30.

3. Orme CM et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;30(4):409-15.

4. Weitz NA et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;32(1):76-84.

5. Revencu N et al. Hum Mutat. 2013 Dec;34(12):1632-41.

6. Iznardo H et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Mar;37(2):342-44.

Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome

with or without arteriovenous malformations, as well as arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). CM-AVM is an autosomal dominant disorder.1 CM-AVM type 1 is caused by mutations in the RASA1 gene, and CM-AVM type 2 is caused by mutations in the EPHB4 gene.2 Approximately 70% of patients with RASA1-associated CM-AVM syndrome and 80% of patients with EPHB4-associated CM-AVM syndrome have an affected parent, while the remainder have de novo variants.1

In patients with CM-AVM syndrome, CMs are often present at birth and more are typically acquired over time. CMs are characteristically 1-3 cm in diameter, round or oval, dull red or red-brown macules and patches with a blanched halo.3 Some CMs may be warm to touch indicating a possible underlying AVM or AVF.4 This can be confirmed by Doppler ultrasound, which would demonstrate increased arterial flow.4 CMs are most commonly located on the face and limbs and may present in isolation, but approximately one-third of patients have associated AVMs and AVFs.1,5 These high-flow vascular malformations may be present in skin, muscle, bone, brain, and/or spine and may be asymptomatic or lead to serious sequelae, including bleeding, congestive heart failure, and neurologic complications, such as migraine headaches, seizures, or even stroke.5 Symptoms from intracranial and spinal high-flow lesions usually present in early childhood and affect approximately 7% of patients.3

The diagnosis of CM-AVM should be suspected in an individual with numerous characteristic CMs and may be supported by the presence of AVMs and AVFs, family history of CM-AVM, and/or identification of RASA1 or EPHB4 mutation by molecular genetic testing.1,3 Although there are no consensus protocols for imaging CM-AVM patients, MRI of the brain and spine is recommended at diagnosis to identify underlying high-flow lesions.1 This may allow for early treatment before the development of symptoms.1 Any lesions identified on screening imaging may require regular surveillance, which is best determined by discussion with the radiologist.1 Although there are no reports of patients with negative results on screening imaging who later develop AVMs or AVFs, there should be a low threshold for repeat imaging in patients who develop new symptoms or physical exam findings.3,4

It has previously been suggested that the CMs in CM-AVM may actually represent early or small AVMs and pulsed-dye laser (PDL) treatment was not recommended because of concern for potential progression of lesions.4 However, a recent study demonstrated good response to PDL in patients with CM-AVM with no evidence of worsening or recurrence of lesions with long-term follow-up.6 Treatment of CMs that cause cosmetic concerns may be considered following discussion of risks and benefits with a dermatologist. Management of AVMs and AVFs requires a multidisciplinary team that, depending on location and symptoms of these features, may require the expertise of specialists such as neurosurgery, surgery, orthopedics, cardiology, and/or interventional radiology.1

Given the suspicion for CM-AVM in our patient, further workup was completed. A skin biopsy was consistent with CM. Genetic testing with the Vascular Malformations Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication revealed a pathogenic variant in the RASA1 gene and a variant of unknown clinical significance in the TEK gene. Parental genetic testing for the RASA1 mutation was negative, supporting a de novo mutation in the patient. CNS imaging showed a small developmental venous malformation in the brain that neurosurgery did not think was clinically significant. At the most recent follow-up at age 8 years, our patient had developed a few new small CMs but was otherwise well.

Dr. Leszczynska is trained in pediatrics and is the current dermatology research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Croce is a dermatology-trained pediatric nurse practitioner and PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing. Dr. Diaz is chief of pediatric dermatology at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, assistant professor of pediatrics and medicine (dermatology), and dermatology residency associate program director at University of Texas at Austin . The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is the editor of this column.

References

1. Bayrak-Toydemir P, Stevenson D. Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; February 22, 2011.

2.Yu J et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Sep;34(5):e227-30.

3. Orme CM et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;30(4):409-15.

4. Weitz NA et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;32(1):76-84.

5. Revencu N et al. Hum Mutat. 2013 Dec;34(12):1632-41.

6. Iznardo H et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Mar;37(2):342-44.

Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome

with or without arteriovenous malformations, as well as arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). CM-AVM is an autosomal dominant disorder.1 CM-AVM type 1 is caused by mutations in the RASA1 gene, and CM-AVM type 2 is caused by mutations in the EPHB4 gene.2 Approximately 70% of patients with RASA1-associated CM-AVM syndrome and 80% of patients with EPHB4-associated CM-AVM syndrome have an affected parent, while the remainder have de novo variants.1

In patients with CM-AVM syndrome, CMs are often present at birth and more are typically acquired over time. CMs are characteristically 1-3 cm in diameter, round or oval, dull red or red-brown macules and patches with a blanched halo.3 Some CMs may be warm to touch indicating a possible underlying AVM or AVF.4 This can be confirmed by Doppler ultrasound, which would demonstrate increased arterial flow.4 CMs are most commonly located on the face and limbs and may present in isolation, but approximately one-third of patients have associated AVMs and AVFs.1,5 These high-flow vascular malformations may be present in skin, muscle, bone, brain, and/or spine and may be asymptomatic or lead to serious sequelae, including bleeding, congestive heart failure, and neurologic complications, such as migraine headaches, seizures, or even stroke.5 Symptoms from intracranial and spinal high-flow lesions usually present in early childhood and affect approximately 7% of patients.3

The diagnosis of CM-AVM should be suspected in an individual with numerous characteristic CMs and may be supported by the presence of AVMs and AVFs, family history of CM-AVM, and/or identification of RASA1 or EPHB4 mutation by molecular genetic testing.1,3 Although there are no consensus protocols for imaging CM-AVM patients, MRI of the brain and spine is recommended at diagnosis to identify underlying high-flow lesions.1 This may allow for early treatment before the development of symptoms.1 Any lesions identified on screening imaging may require regular surveillance, which is best determined by discussion with the radiologist.1 Although there are no reports of patients with negative results on screening imaging who later develop AVMs or AVFs, there should be a low threshold for repeat imaging in patients who develop new symptoms or physical exam findings.3,4

It has previously been suggested that the CMs in CM-AVM may actually represent early or small AVMs and pulsed-dye laser (PDL) treatment was not recommended because of concern for potential progression of lesions.4 However, a recent study demonstrated good response to PDL in patients with CM-AVM with no evidence of worsening or recurrence of lesions with long-term follow-up.6 Treatment of CMs that cause cosmetic concerns may be considered following discussion of risks and benefits with a dermatologist. Management of AVMs and AVFs requires a multidisciplinary team that, depending on location and symptoms of these features, may require the expertise of specialists such as neurosurgery, surgery, orthopedics, cardiology, and/or interventional radiology.1

Given the suspicion for CM-AVM in our patient, further workup was completed. A skin biopsy was consistent with CM. Genetic testing with the Vascular Malformations Panel, Sequencing and Deletion/Duplication revealed a pathogenic variant in the RASA1 gene and a variant of unknown clinical significance in the TEK gene. Parental genetic testing for the RASA1 mutation was negative, supporting a de novo mutation in the patient. CNS imaging showed a small developmental venous malformation in the brain that neurosurgery did not think was clinically significant. At the most recent follow-up at age 8 years, our patient had developed a few new small CMs but was otherwise well.

Dr. Leszczynska is trained in pediatrics and is the current dermatology research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. Ms. Croce is a dermatology-trained pediatric nurse practitioner and PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing. Dr. Diaz is chief of pediatric dermatology at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, assistant professor of pediatrics and medicine (dermatology), and dermatology residency associate program director at University of Texas at Austin . The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, is the editor of this column.

References

1. Bayrak-Toydemir P, Stevenson D. Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; February 22, 2011.

2.Yu J et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Sep;34(5):e227-30.

3. Orme CM et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug;30(4):409-15.

4. Weitz NA et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;32(1):76-84.

5. Revencu N et al. Hum Mutat. 2013 Dec;34(12):1632-41.

6. Iznardo H et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020 Mar;37(2):342-44.

Higher cardiovascular risks in Kawasaki disease persist 10-plus years

Risks are highest in first year.

Survivors of Kawasaki disease remain at a higher long-term risk for cardiovascular events into young adulthood, including myocardial infarction, compared to people without the disease, new evidence reveals. The elevated risks emerged in survivors both with and without cardiovascular involvement at the time of initial diagnosis.

Overall risk of cardiovascular events was highest in the first year following Kawasaki disease diagnosis, and about 10 times greater than in healthy children, Cal Robinson, MD, said during a press conference at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The risk gradually decreased over time. However, even 10 years after diagnosis of their illness, they still had a 39% higher risk,” said study author Dr. Robinson, a PGY4 pediatric nephrology fellow at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Dr. Robinson also put the numbers in perspective. “We fully acknowledged these are very rare events in children, especially healthy children, which is why we needed such a large cohort to study this. Interpret the numbers cautiously.”

In terms of patient and family counseling, “I would say children with Kawasaki disease have a higher risk of myocardial infarction, but the absolute risk is still low,” he added. For example, 16 Kawasaki disease survivors experienced a heart attack during follow-up, or 0.4% of the affected study population, compared to a rate of 0.1% among matched controls.

“These families are often very frightened after the initial Kawasaki disease diagnosis,” Dr. Robinson said. “We have to balance some discussion with what we know about Kawasaki disease without overly scaring or terrifying these families, who are already anxious.”

To quantify the incidence and timing of cardiovascular events and cardiac disease following diagnosis, Dr. Robinson and colleagues assessed large databases representing approximately 3 million children. They focused on children hospitalized with a Kawasaki disease diagnosis between 1995 and 2018. These children had a median length of stay of 3 days and 2.5% were admitted to critical care. The investigators matched his population 1:100 to unaffected children in Ontario.

Follow-up was up to 24 years (median, 11 years) in this retrospective, population-based cohort study.

Risks raised over a decade and beyond

Compared to matched controls, Kawasaki disease survivors had a higher risk for a cardiac event in the first year following diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 11.65; 95% confidence interval, 10.34-13.13). The 1- to 5-year risk was lower (aHR, 3.35), a trend that continued between 5 and 10 years (aHR, 1.87) and as well as after more than 10 years (aHR, 1.39).

The risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE, a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death) was likewise highest in the first year after diagnosis (aHR, 3.27), followed by a 51% greater risk at 1-5 years, a 113% increased risk at 5-10 years, and a 17% elevated risk after 10 years.

The investigators compared the 144 Kawasaki disease survivors who experienced a coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) within 90 days of hospital admission to the 4,453 others who did not have a CAA. The risk for a composite cardiovascular event was elevated at each time point among those with a history of CAA, especially in the first year. The adjusted HR was 33.12 in the CAA group versus 10.44 in the non-CAA group.

“The most interesting finding of this study was that children with Kawasaki syndrome are at higher risk for composite cardiovascular events and major adverse cardiac events even if they were not diagnosed with coronary artery aneurysm,” session comoderator Shervin Assassi, MD, professor of medicine and director of division of rheumatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said when asked to comment.

Dr. Robinson and colleagues also looked at outcomes based on presence or absence of coronary involvement at the time of Kawasaki disease diagnosis. For example, among those with initial coronary involvement, 15% later experienced a cardiovascular event and 10% experienced a major cardiovascular event.

“However, we were specifically interested in looking at children without initial coronary involvement. In this group, we also found these children were at increased risk for cardiovascular events compared to children without Kawasaki disease,” Dr. Robinson said. He said the distinction is important because approximately 95% of children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease do not feature initial coronary involvement.

In terms of clinical care, “our data provides an early signal that Kawasaki disease survivors – including those without initial coronary involvement – may be at higher risk of cardiovascular events into early adulthood.”

A call for closer monitoring

“Based on our results, we find that Kawasaki disease survivors may benefit from additional follow-up and surveillance for cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol,” Dr. Robinson said. Early identification of heightened risk could allow physicians to more closely monitor this subgroup and emphasize potentially beneficial lifestyle modifications, including increasing physical activity, implementing a heart healthy diet, and avoiding smoking.

Mortality was not significantly different between groups. “Despite the risk of cardiac events we found, death was uncommon,” Dr. Robinson said. Among children with Kawasaki disease, 1 in 500 died during follow-up, so “the risk of death was actually lower than for children without Kawasaki disease.”

Similar findings of lower mortality have been reported in research out of Japan, he added during a plenary presentation at ACR 2020. Future research is warranted to evaluate this finding further, Dr. Robinson said.

Future plans

Going forward, the investigators plan to evaluate noncardiovascular outcomes in this patient population. They would also like to examine health care utilization following a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease “to better understand what kind of follow-up is happening now in Ontario,” Dr. Robinson said.

Another unanswered question is whether the cardiovascular events observed in the study stem from atherosclerotic disease or a different mechanism among survivors of Kawasaki disease.

The research was supported by a McMaster University Resident Research Grant, a Hamilton Health Sciences New Investigator Award, and Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Dr. Robinson had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robinson C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10): Abstract 0937.

Risks are highest in first year.

Risks are highest in first year.

Survivors of Kawasaki disease remain at a higher long-term risk for cardiovascular events into young adulthood, including myocardial infarction, compared to people without the disease, new evidence reveals. The elevated risks emerged in survivors both with and without cardiovascular involvement at the time of initial diagnosis.

Overall risk of cardiovascular events was highest in the first year following Kawasaki disease diagnosis, and about 10 times greater than in healthy children, Cal Robinson, MD, said during a press conference at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The risk gradually decreased over time. However, even 10 years after diagnosis of their illness, they still had a 39% higher risk,” said study author Dr. Robinson, a PGY4 pediatric nephrology fellow at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Dr. Robinson also put the numbers in perspective. “We fully acknowledged these are very rare events in children, especially healthy children, which is why we needed such a large cohort to study this. Interpret the numbers cautiously.”

In terms of patient and family counseling, “I would say children with Kawasaki disease have a higher risk of myocardial infarction, but the absolute risk is still low,” he added. For example, 16 Kawasaki disease survivors experienced a heart attack during follow-up, or 0.4% of the affected study population, compared to a rate of 0.1% among matched controls.

“These families are often very frightened after the initial Kawasaki disease diagnosis,” Dr. Robinson said. “We have to balance some discussion with what we know about Kawasaki disease without overly scaring or terrifying these families, who are already anxious.”

To quantify the incidence and timing of cardiovascular events and cardiac disease following diagnosis, Dr. Robinson and colleagues assessed large databases representing approximately 3 million children. They focused on children hospitalized with a Kawasaki disease diagnosis between 1995 and 2018. These children had a median length of stay of 3 days and 2.5% were admitted to critical care. The investigators matched his population 1:100 to unaffected children in Ontario.

Follow-up was up to 24 years (median, 11 years) in this retrospective, population-based cohort study.

Risks raised over a decade and beyond

Compared to matched controls, Kawasaki disease survivors had a higher risk for a cardiac event in the first year following diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 11.65; 95% confidence interval, 10.34-13.13). The 1- to 5-year risk was lower (aHR, 3.35), a trend that continued between 5 and 10 years (aHR, 1.87) and as well as after more than 10 years (aHR, 1.39).

The risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE, a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death) was likewise highest in the first year after diagnosis (aHR, 3.27), followed by a 51% greater risk at 1-5 years, a 113% increased risk at 5-10 years, and a 17% elevated risk after 10 years.

The investigators compared the 144 Kawasaki disease survivors who experienced a coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) within 90 days of hospital admission to the 4,453 others who did not have a CAA. The risk for a composite cardiovascular event was elevated at each time point among those with a history of CAA, especially in the first year. The adjusted HR was 33.12 in the CAA group versus 10.44 in the non-CAA group.

“The most interesting finding of this study was that children with Kawasaki syndrome are at higher risk for composite cardiovascular events and major adverse cardiac events even if they were not diagnosed with coronary artery aneurysm,” session comoderator Shervin Assassi, MD, professor of medicine and director of division of rheumatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said when asked to comment.

Dr. Robinson and colleagues also looked at outcomes based on presence or absence of coronary involvement at the time of Kawasaki disease diagnosis. For example, among those with initial coronary involvement, 15% later experienced a cardiovascular event and 10% experienced a major cardiovascular event.

“However, we were specifically interested in looking at children without initial coronary involvement. In this group, we also found these children were at increased risk for cardiovascular events compared to children without Kawasaki disease,” Dr. Robinson said. He said the distinction is important because approximately 95% of children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease do not feature initial coronary involvement.

In terms of clinical care, “our data provides an early signal that Kawasaki disease survivors – including those without initial coronary involvement – may be at higher risk of cardiovascular events into early adulthood.”

A call for closer monitoring

“Based on our results, we find that Kawasaki disease survivors may benefit from additional follow-up and surveillance for cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol,” Dr. Robinson said. Early identification of heightened risk could allow physicians to more closely monitor this subgroup and emphasize potentially beneficial lifestyle modifications, including increasing physical activity, implementing a heart healthy diet, and avoiding smoking.

Mortality was not significantly different between groups. “Despite the risk of cardiac events we found, death was uncommon,” Dr. Robinson said. Among children with Kawasaki disease, 1 in 500 died during follow-up, so “the risk of death was actually lower than for children without Kawasaki disease.”

Similar findings of lower mortality have been reported in research out of Japan, he added during a plenary presentation at ACR 2020. Future research is warranted to evaluate this finding further, Dr. Robinson said.

Future plans

Going forward, the investigators plan to evaluate noncardiovascular outcomes in this patient population. They would also like to examine health care utilization following a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease “to better understand what kind of follow-up is happening now in Ontario,” Dr. Robinson said.

Another unanswered question is whether the cardiovascular events observed in the study stem from atherosclerotic disease or a different mechanism among survivors of Kawasaki disease.

The research was supported by a McMaster University Resident Research Grant, a Hamilton Health Sciences New Investigator Award, and Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Dr. Robinson had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robinson C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10): Abstract 0937.

Survivors of Kawasaki disease remain at a higher long-term risk for cardiovascular events into young adulthood, including myocardial infarction, compared to people without the disease, new evidence reveals. The elevated risks emerged in survivors both with and without cardiovascular involvement at the time of initial diagnosis.

Overall risk of cardiovascular events was highest in the first year following Kawasaki disease diagnosis, and about 10 times greater than in healthy children, Cal Robinson, MD, said during a press conference at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The risk gradually decreased over time. However, even 10 years after diagnosis of their illness, they still had a 39% higher risk,” said study author Dr. Robinson, a PGY4 pediatric nephrology fellow at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Dr. Robinson also put the numbers in perspective. “We fully acknowledged these are very rare events in children, especially healthy children, which is why we needed such a large cohort to study this. Interpret the numbers cautiously.”

In terms of patient and family counseling, “I would say children with Kawasaki disease have a higher risk of myocardial infarction, but the absolute risk is still low,” he added. For example, 16 Kawasaki disease survivors experienced a heart attack during follow-up, or 0.4% of the affected study population, compared to a rate of 0.1% among matched controls.

“These families are often very frightened after the initial Kawasaki disease diagnosis,” Dr. Robinson said. “We have to balance some discussion with what we know about Kawasaki disease without overly scaring or terrifying these families, who are already anxious.”

To quantify the incidence and timing of cardiovascular events and cardiac disease following diagnosis, Dr. Robinson and colleagues assessed large databases representing approximately 3 million children. They focused on children hospitalized with a Kawasaki disease diagnosis between 1995 and 2018. These children had a median length of stay of 3 days and 2.5% were admitted to critical care. The investigators matched his population 1:100 to unaffected children in Ontario.

Follow-up was up to 24 years (median, 11 years) in this retrospective, population-based cohort study.

Risks raised over a decade and beyond

Compared to matched controls, Kawasaki disease survivors had a higher risk for a cardiac event in the first year following diagnosis (adjusted hazard ratio, 11.65; 95% confidence interval, 10.34-13.13). The 1- to 5-year risk was lower (aHR, 3.35), a trend that continued between 5 and 10 years (aHR, 1.87) and as well as after more than 10 years (aHR, 1.39).

The risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE, a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death) was likewise highest in the first year after diagnosis (aHR, 3.27), followed by a 51% greater risk at 1-5 years, a 113% increased risk at 5-10 years, and a 17% elevated risk after 10 years.

The investigators compared the 144 Kawasaki disease survivors who experienced a coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) within 90 days of hospital admission to the 4,453 others who did not have a CAA. The risk for a composite cardiovascular event was elevated at each time point among those with a history of CAA, especially in the first year. The adjusted HR was 33.12 in the CAA group versus 10.44 in the non-CAA group.

“The most interesting finding of this study was that children with Kawasaki syndrome are at higher risk for composite cardiovascular events and major adverse cardiac events even if they were not diagnosed with coronary artery aneurysm,” session comoderator Shervin Assassi, MD, professor of medicine and director of division of rheumatology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said when asked to comment.

Dr. Robinson and colleagues also looked at outcomes based on presence or absence of coronary involvement at the time of Kawasaki disease diagnosis. For example, among those with initial coronary involvement, 15% later experienced a cardiovascular event and 10% experienced a major cardiovascular event.

“However, we were specifically interested in looking at children without initial coronary involvement. In this group, we also found these children were at increased risk for cardiovascular events compared to children without Kawasaki disease,” Dr. Robinson said. He said the distinction is important because approximately 95% of children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease do not feature initial coronary involvement.

In terms of clinical care, “our data provides an early signal that Kawasaki disease survivors – including those without initial coronary involvement – may be at higher risk of cardiovascular events into early adulthood.”

A call for closer monitoring

“Based on our results, we find that Kawasaki disease survivors may benefit from additional follow-up and surveillance for cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol,” Dr. Robinson said. Early identification of heightened risk could allow physicians to more closely monitor this subgroup and emphasize potentially beneficial lifestyle modifications, including increasing physical activity, implementing a heart healthy diet, and avoiding smoking.

Mortality was not significantly different between groups. “Despite the risk of cardiac events we found, death was uncommon,” Dr. Robinson said. Among children with Kawasaki disease, 1 in 500 died during follow-up, so “the risk of death was actually lower than for children without Kawasaki disease.”

Similar findings of lower mortality have been reported in research out of Japan, he added during a plenary presentation at ACR 2020. Future research is warranted to evaluate this finding further, Dr. Robinson said.

Future plans

Going forward, the investigators plan to evaluate noncardiovascular outcomes in this patient population. They would also like to examine health care utilization following a diagnosis of Kawasaki disease “to better understand what kind of follow-up is happening now in Ontario,” Dr. Robinson said.

Another unanswered question is whether the cardiovascular events observed in the study stem from atherosclerotic disease or a different mechanism among survivors of Kawasaki disease.

The research was supported by a McMaster University Resident Research Grant, a Hamilton Health Sciences New Investigator Award, and Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Dr. Robinson had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robinson C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10): Abstract 0937.

FROM ACR 2020

Key clinical point: Kawasaki disease survivors remain at elevated long-term risk for cardiovascular events.

Major finding: Overall cardiovascular event risk was 39% higher, even after 10 years.

Study details: A retrospective, population-based cohort study of more than 4,597 Kawasaki disease survivors and 459,700 matched children without Kawasaki disease.

Disclosures: The research was supported by a McMaster University Resident Research Grant, a Hamilton Health Sciences New Investigator Award, and Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Dr. Robinson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Robinson C et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10): Abstract 0937.

Gene-replacement therapy shows promise in X-linked myotubular myopathy

, according to research presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, which was held virtually this year. The treatment also appears to improve patients’ motor function significantly and help them to achieve motor milestones.

The results come from a phase 1/2 study of two doses of AT132. Three of 17 patients who received the higher dose had fatal liver dysfunction. The researchers are investigating these cases and will communicate their findings.

X-linked myotubular myopathy is a rare and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Mutations in MTM1, which encodes the myotubularin enzyme that is required for the development and function of skeletal muscle, cause the disease, which affects about one in 50,000 to one in 40,000 newborn boys. The disease is associated with profound muscle weakness and impairment of neuromuscular and respiratory function. Patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy achieve motor milestones much later or not at all, and most require a ventilator or a feeding tube. The mortality by age 18 months is approximately 50%.

The ASPIRO trial

Investigators theorized that muscle tissue would be an appropriate therapeutic target because it does not display dystrophic or inflammatory changes in most patients. They identified adeno-associated virus AAV8 as a potential carrier for gene therapy, since it targets skeletal muscle effectively.

Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, an attending physician at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and colleagues conducted the ASPIRO trial to examine AT132 as a potential treatment for X-linked myotubular myopathy. Eligible patients were younger than 5 years or had previously enrolled in a natural history study of the disease, required ventilator support at baseline, and had no clinically significant underlying liver disease. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132, 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132, or delayed treatment. Participants assigned to delayed treatment served as the study’s control group.

The study’s primary end points were safety and change in hours of daily ventilator support from baseline to week 24 after dosing. The investigators also examined a respiratory endpoint (i.e., maximal inspiratory pressure [MIP]) and neuromuscular endpoints (i.e., motor milestones, CHOP INTEND score, and muscle biopsy).

Treatment improved respiratory function

As of July 28, Dr. Kuntz and colleagues had enrolled 23 patients in the trial. Six participants received the lower dose of therapy, and 17 received the higher dose. Median age was 1.7 years for the low-dose group and 2.6 years for the high-dose group.

Patients assigned to receive the higher dose of therapy received treatment more recently than the low-dose group, and not all of the former have reached 48 weeks since treatment, said Dr. Kuntz. Fewer efficacy data are thus available for the high-dose group.

Each dose of AT132 was associated with a significantly greater decrease from baseline in least squares mean daily hours of ventilator dependence, compared with the control condition. At week 48, the mean reduction was approximately 19 hours/day for patients receiving 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132 and approximately 13 hours per day for patients receiving 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132. The investigators did not perform a statistical comparison of the two doses because of differing protocols for ventilator weaning between groups. All six patients who received the lower dose achieved ventilator independence, as did one patient who received the higher dose.

In addition, all treated patients had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean MIP, compared with controls. The mean increase was 45.7 cmH2O for the low-dose group, 46.1 cmH2O for the high-dose group, and −8.0 cmH2O for controls.

Before treatment, most patients had not achieved any of the motor milestones that investigators assessed. After treatment, five of six patients receiving the low dose achieved independent walking, as did one in 10 patients receiving the high dose. No controls achieved this milestone. Treated patients also had significantly greater increases from baseline in least squares mean CHOP INTEND scores, compared with controls. At least at one time point, five of six patients receiving the low dose, six of 10 patients receiving the high dose, and one control patient achieved the mean score observed in healthy infants.

Patients in both treatment arms had improvements in muscle pathology at weeks 24 and 48, including improvements in organelle localization and fiber size. In addition, patients in both treatment arms had continued detectable vector copies and myotubularin protein expression at both time points.

Deaths under investigation

In the low-dose group, one patient had four serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and in the high-dose group, eight patients had 27 serious treatment-emergent adverse events. The three patients in the high-dose group who developed fatal liver dysfunction were among the older, heavier patients in the study and, consequently, received among the highest total doses of treatment. These patients had evidence of likely preexisting intrahepatic cholestasis.

“This clinical trial is on hold pending discussions between regulatory agencies and the study sponsor regarding additional recruitment and the duration of follow-up,” said Dr. Kuntz.

Audentes Therapeutics, which is developing AT132, funded the trial. Dr. Kuntz had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bönnemann CG et al. CNS-ICNA 2020, Abstract P.62.

, according to research presented at the 2020 CNS-ICNA Conjoint Meeting, which was held virtually this year. The treatment also appears to improve patients’ motor function significantly and help them to achieve motor milestones.

The results come from a phase 1/2 study of two doses of AT132. Three of 17 patients who received the higher dose had fatal liver dysfunction. The researchers are investigating these cases and will communicate their findings.

X-linked myotubular myopathy is a rare and often fatal neuromuscular disease. Mutations in MTM1, which encodes the myotubularin enzyme that is required for the development and function of skeletal muscle, cause the disease, which affects about one in 50,000 to one in 40,000 newborn boys. The disease is associated with profound muscle weakness and impairment of neuromuscular and respiratory function. Patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy achieve motor milestones much later or not at all, and most require a ventilator or a feeding tube. The mortality by age 18 months is approximately 50%.

The ASPIRO trial

Investigators theorized that muscle tissue would be an appropriate therapeutic target because it does not display dystrophic or inflammatory changes in most patients. They identified adeno-associated virus AAV8 as a potential carrier for gene therapy, since it targets skeletal muscle effectively.

Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, an attending physician at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and colleagues conducted the ASPIRO trial to examine AT132 as a potential treatment for X-linked myotubular myopathy. Eligible patients were younger than 5 years or had previously enrolled in a natural history study of the disease, required ventilator support at baseline, and had no clinically significant underlying liver disease. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 × 1014 vg/kg of AAT132, 3 × 1014 vg/kg of AT132, or delayed treatment. Participants assigned to delayed treatment served as the study’s control group.