User login

ILD on the rise: Doctors offer tips for diagnosing deadly disease

“There is definitely a delay from the time of symptom onset to the time that they are even evaluated for ILD,” said Dr. Kulkarni of the department of pulmonary, allergy and critical care medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “Some patients have had a significant loss of lung function by the time they come to see us. By that point we are limited by what treatment options we can offer.”

Interstitial lung disease is an umbrella term for a group of disorders involving progressive scarring of the lungs – typically irreversible – usually caused by long-term exposure to hazardous materials or by autoimmune effects. It includes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a disease that is fairly rare but which has therapy options that can be effective if caught early enough. The term pulmonary fibrosis refers to lung scarring. Another type of ILD is pulmonary sarcoidosis, in which small clumps of immune cells form in the lungs in an immune response sometimes following an environmental trigger, and can lead to lung scarring if it doesn’t resolve.

Cases of ILD appear to be on the rise, and COVID-19 has made diagnosing it more complicated. One study found the prevalence of ILD and pulmonary sarcoidosis in high-income countries was about 122 of every 100,000 people in 1990 and rose to about 198 of every 100,000 people in 2017. The data were pulled from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. Globally, the researchers found a prevalence of 62 per 100,000 in 1990, compared with 82 per 100,000 in 2017.

If all of a patient’s symptoms have appeared post COVID and a physician is seeing a patient within 4-6 weeks of COVID symptoms, it is likely that the symptoms are COVID related. But a full work-up is recommended if a patient has lung crackles, which are an indicator of lung scarring, she said.

“The patterns that are seen on CT scan for COVID pneumonia are very distinct from what we expect to see with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” Dr. Kulkarni said. “Putting all this information together is what is important to differentiate it from COVID pneumonia, as well as other types of ILD.”

A study published earlier this year found similarities between COVID-19 and IPF in gene expression, their IL-15-heavy cytokine storms, and the type of damage to alveolar cells. Both might be driven by endoplasmic reticulum stress, they found.

“COVID-19 resembles IPF at a fundamental level,” they wrote.

Jeffrey Horowitz, MD, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, said the need for early diagnosis is in part a function of the therapies available for ILD.

“They don’t make the lung function better,” he said. “So delays in diagnosis mean that there’s the possibility of underlying progression for months, or sometimes years, before the diagnosis is recognized.”

In an area in which diagnosis is delayed and the prognosis is dire – 3-5 years in untreated patients after diagnosis – “there’s a tremendous amount of nihilism out there” among patients, he said.

He said patients with long-term shortness of breath and unexplained cough are often told they have asthma and are prescribed inhalers, but then further assessment isn’t performed when those don’t work.

Diagnosing ILD in primary care

Many primary care physicians feel ill-equipped to discuss IPF. More than a dozen physicians contacted for this piece to talk about ILD either did not respond, or said they felt unqualified to respond to questions on the disease.

“Not my area of expertise” and “I don’t think I’m the right person for this discussion” were two of the responses provided to this news organization.

“For some reason, in the world of primary care, it seems like there’s an impediment to getting pulmonary function studies,” Dr. Horowitz said. “Anybody who has a persistent ongoing prolonged unexplained shortness of breath and cough should have pulmonary function studies done.”

Listening to the lungs alone might not be enough, he said. There might be no clear sign in the case of early pulmonary fibrosis, he said.

“There’s the textbook description of these Velcro-sounding crackles, but sometimes it’s very subtle,” he said. “And unless you’re listening very carefully it can easily be missed by somebody who has a busy practice, or it’s loud.”

William E. Golden, MD, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, is the sole primary care physician contacted for this piece who spoke with authority on ILD.

For cases of suspected ILD, internist Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, suggested ordering a test for diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which will be low in the case of IPF, along with a fine-cut lung CT scan to assess ongoing fibrotic changes.

It’s “not that difficult, but you need to have an index of suspicion for the diagnosis,” he said.

New initiative for helping diagnose ILD

Dr. Kulkarni is a committee member for a new effort under way to try to get patients with ILD diagnosed earlier.

The initiative, called Bridging Specialties: Timely Diagnosis for ILD Patients, has already produced an introductory podcast and a white paper on the effort, and its rationale is expected to be released soon, according to Dr. Kulkarni and her fellow committee members.

The American College of Chest Physicians and the Three Lakes Foundation – a foundation dedicated to pulmonary fibrosis awareness and research – are working together on this initiative. They plan to put together a suite of resources, to be gradually rolled out on the college’s website, to raise awareness about the importance of early diagnosis of ILD.

The full toolkit, expected to be rolled out over the next 12 months, will include a series of podcasts and resources on how to get patients diagnosed earlier and steps to take in cases of suspected ILD, Dr. Kulkarni said.

“The goal would be to try to increase awareness about the disease so that people start thinking more about it up front – and not after we’ve ruled out everything else,” she said. The main audience will be primary care providers, but patients and community pulmonologists would likely also benefit from the resources, the committee members said.

The urgency of the initiative stems from the way ILD treatments work. They are antifibrotic, meaning they help prevent scar tissue from forming, but they can’t reverse scar tissue that has already formed. If scarring is severe, the only option might be a lung transplant, and, since the average age at ILD diagnosis is in the 60s, many patients have comorbidities that make them ineligible for transplant. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study mentioned earlier, the death rate per 100,000 people with ILD was 1.93 in 2017.

“The longer we take to diagnose it, the more chance that inflammation will become scar tissue,” Dr. Kularni explained.

William Lago, MD, another member of the committee and a family physician, said identifying ILD early is not a straightforward matter .

“When they first present, it’s hard to pick up,” said Dr. Lago, who is also a staff physician at Cleveland Clinic’s Wooster Family Health Center and medical director of the COVID Recover Clinic there. “Many of them, even themselves, will discount the symptoms.”

Dr. Lago said that patients might resist having a work-up even when a primary care physician identifies symptoms as possible ILD. In rural settings, they might have to travel quite a distance for a CT scan or other necessary evaluations, or they might just not think the symptoms are serious enough.

“Most of the time when I’ve picked up some of my pulmonary fibrosis patients, it’s been incidentally while they’re in the office for other things,” he said. He often has to “push the issue” for further work-up, he said.

The overlap of shortness of breath and cough with other, much more common disorders, such as heart disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), make ILD diagnosis a challenge, he said.

“For most of us, we’ve got sometimes 10 or 15 minutes with a patient who’s presenting with 5-6 different problems. And the shortness of breath or the occasional cough – that they think is nothing – is probably the least of those,” Dr. Lago said.

Dr. Golden said he suspected a tool like the one being developed by CHEST to be useful for some and not useful for others. He added that “no one has the time to spend on that kind of thing.”

Instead, he suggested just reinforcing what the core symptoms are and what the core testing is, “to make people think about it.”

Dr. Horowitiz seemed more optimistic about the likelihood of the CHEST tool being utilized to diagnose ILD.

Whether and how he would use the CHEST resource will depend on the final form it takes, Dr. Horowitz said. It’s encouraging that it’s being put together by a credible source, he added.

Dr. Kulkarni reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Aluda Pharmaceuticals and PureTech Lyt-100 Inc. Dr. Lago, Dr. Horowitz, and Dr. Golden reported no relevant disclosures.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

“There is definitely a delay from the time of symptom onset to the time that they are even evaluated for ILD,” said Dr. Kulkarni of the department of pulmonary, allergy and critical care medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “Some patients have had a significant loss of lung function by the time they come to see us. By that point we are limited by what treatment options we can offer.”

Interstitial lung disease is an umbrella term for a group of disorders involving progressive scarring of the lungs – typically irreversible – usually caused by long-term exposure to hazardous materials or by autoimmune effects. It includes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a disease that is fairly rare but which has therapy options that can be effective if caught early enough. The term pulmonary fibrosis refers to lung scarring. Another type of ILD is pulmonary sarcoidosis, in which small clumps of immune cells form in the lungs in an immune response sometimes following an environmental trigger, and can lead to lung scarring if it doesn’t resolve.

Cases of ILD appear to be on the rise, and COVID-19 has made diagnosing it more complicated. One study found the prevalence of ILD and pulmonary sarcoidosis in high-income countries was about 122 of every 100,000 people in 1990 and rose to about 198 of every 100,000 people in 2017. The data were pulled from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. Globally, the researchers found a prevalence of 62 per 100,000 in 1990, compared with 82 per 100,000 in 2017.

If all of a patient’s symptoms have appeared post COVID and a physician is seeing a patient within 4-6 weeks of COVID symptoms, it is likely that the symptoms are COVID related. But a full work-up is recommended if a patient has lung crackles, which are an indicator of lung scarring, she said.

“The patterns that are seen on CT scan for COVID pneumonia are very distinct from what we expect to see with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” Dr. Kulkarni said. “Putting all this information together is what is important to differentiate it from COVID pneumonia, as well as other types of ILD.”

A study published earlier this year found similarities between COVID-19 and IPF in gene expression, their IL-15-heavy cytokine storms, and the type of damage to alveolar cells. Both might be driven by endoplasmic reticulum stress, they found.

“COVID-19 resembles IPF at a fundamental level,” they wrote.

Jeffrey Horowitz, MD, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, said the need for early diagnosis is in part a function of the therapies available for ILD.

“They don’t make the lung function better,” he said. “So delays in diagnosis mean that there’s the possibility of underlying progression for months, or sometimes years, before the diagnosis is recognized.”

In an area in which diagnosis is delayed and the prognosis is dire – 3-5 years in untreated patients after diagnosis – “there’s a tremendous amount of nihilism out there” among patients, he said.

He said patients with long-term shortness of breath and unexplained cough are often told they have asthma and are prescribed inhalers, but then further assessment isn’t performed when those don’t work.

Diagnosing ILD in primary care

Many primary care physicians feel ill-equipped to discuss IPF. More than a dozen physicians contacted for this piece to talk about ILD either did not respond, or said they felt unqualified to respond to questions on the disease.

“Not my area of expertise” and “I don’t think I’m the right person for this discussion” were two of the responses provided to this news organization.

“For some reason, in the world of primary care, it seems like there’s an impediment to getting pulmonary function studies,” Dr. Horowitz said. “Anybody who has a persistent ongoing prolonged unexplained shortness of breath and cough should have pulmonary function studies done.”

Listening to the lungs alone might not be enough, he said. There might be no clear sign in the case of early pulmonary fibrosis, he said.

“There’s the textbook description of these Velcro-sounding crackles, but sometimes it’s very subtle,” he said. “And unless you’re listening very carefully it can easily be missed by somebody who has a busy practice, or it’s loud.”

William E. Golden, MD, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, is the sole primary care physician contacted for this piece who spoke with authority on ILD.

For cases of suspected ILD, internist Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, suggested ordering a test for diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which will be low in the case of IPF, along with a fine-cut lung CT scan to assess ongoing fibrotic changes.

It’s “not that difficult, but you need to have an index of suspicion for the diagnosis,” he said.

New initiative for helping diagnose ILD

Dr. Kulkarni is a committee member for a new effort under way to try to get patients with ILD diagnosed earlier.

The initiative, called Bridging Specialties: Timely Diagnosis for ILD Patients, has already produced an introductory podcast and a white paper on the effort, and its rationale is expected to be released soon, according to Dr. Kulkarni and her fellow committee members.

The American College of Chest Physicians and the Three Lakes Foundation – a foundation dedicated to pulmonary fibrosis awareness and research – are working together on this initiative. They plan to put together a suite of resources, to be gradually rolled out on the college’s website, to raise awareness about the importance of early diagnosis of ILD.

The full toolkit, expected to be rolled out over the next 12 months, will include a series of podcasts and resources on how to get patients diagnosed earlier and steps to take in cases of suspected ILD, Dr. Kulkarni said.

“The goal would be to try to increase awareness about the disease so that people start thinking more about it up front – and not after we’ve ruled out everything else,” she said. The main audience will be primary care providers, but patients and community pulmonologists would likely also benefit from the resources, the committee members said.

The urgency of the initiative stems from the way ILD treatments work. They are antifibrotic, meaning they help prevent scar tissue from forming, but they can’t reverse scar tissue that has already formed. If scarring is severe, the only option might be a lung transplant, and, since the average age at ILD diagnosis is in the 60s, many patients have comorbidities that make them ineligible for transplant. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study mentioned earlier, the death rate per 100,000 people with ILD was 1.93 in 2017.

“The longer we take to diagnose it, the more chance that inflammation will become scar tissue,” Dr. Kularni explained.

William Lago, MD, another member of the committee and a family physician, said identifying ILD early is not a straightforward matter .

“When they first present, it’s hard to pick up,” said Dr. Lago, who is also a staff physician at Cleveland Clinic’s Wooster Family Health Center and medical director of the COVID Recover Clinic there. “Many of them, even themselves, will discount the symptoms.”

Dr. Lago said that patients might resist having a work-up even when a primary care physician identifies symptoms as possible ILD. In rural settings, they might have to travel quite a distance for a CT scan or other necessary evaluations, or they might just not think the symptoms are serious enough.

“Most of the time when I’ve picked up some of my pulmonary fibrosis patients, it’s been incidentally while they’re in the office for other things,” he said. He often has to “push the issue” for further work-up, he said.

The overlap of shortness of breath and cough with other, much more common disorders, such as heart disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), make ILD diagnosis a challenge, he said.

“For most of us, we’ve got sometimes 10 or 15 minutes with a patient who’s presenting with 5-6 different problems. And the shortness of breath or the occasional cough – that they think is nothing – is probably the least of those,” Dr. Lago said.

Dr. Golden said he suspected a tool like the one being developed by CHEST to be useful for some and not useful for others. He added that “no one has the time to spend on that kind of thing.”

Instead, he suggested just reinforcing what the core symptoms are and what the core testing is, “to make people think about it.”

Dr. Horowitiz seemed more optimistic about the likelihood of the CHEST tool being utilized to diagnose ILD.

Whether and how he would use the CHEST resource will depend on the final form it takes, Dr. Horowitz said. It’s encouraging that it’s being put together by a credible source, he added.

Dr. Kulkarni reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Aluda Pharmaceuticals and PureTech Lyt-100 Inc. Dr. Lago, Dr. Horowitz, and Dr. Golden reported no relevant disclosures.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

“There is definitely a delay from the time of symptom onset to the time that they are even evaluated for ILD,” said Dr. Kulkarni of the department of pulmonary, allergy and critical care medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “Some patients have had a significant loss of lung function by the time they come to see us. By that point we are limited by what treatment options we can offer.”

Interstitial lung disease is an umbrella term for a group of disorders involving progressive scarring of the lungs – typically irreversible – usually caused by long-term exposure to hazardous materials or by autoimmune effects. It includes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a disease that is fairly rare but which has therapy options that can be effective if caught early enough. The term pulmonary fibrosis refers to lung scarring. Another type of ILD is pulmonary sarcoidosis, in which small clumps of immune cells form in the lungs in an immune response sometimes following an environmental trigger, and can lead to lung scarring if it doesn’t resolve.

Cases of ILD appear to be on the rise, and COVID-19 has made diagnosing it more complicated. One study found the prevalence of ILD and pulmonary sarcoidosis in high-income countries was about 122 of every 100,000 people in 1990 and rose to about 198 of every 100,000 people in 2017. The data were pulled from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. Globally, the researchers found a prevalence of 62 per 100,000 in 1990, compared with 82 per 100,000 in 2017.

If all of a patient’s symptoms have appeared post COVID and a physician is seeing a patient within 4-6 weeks of COVID symptoms, it is likely that the symptoms are COVID related. But a full work-up is recommended if a patient has lung crackles, which are an indicator of lung scarring, she said.

“The patterns that are seen on CT scan for COVID pneumonia are very distinct from what we expect to see with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” Dr. Kulkarni said. “Putting all this information together is what is important to differentiate it from COVID pneumonia, as well as other types of ILD.”

A study published earlier this year found similarities between COVID-19 and IPF in gene expression, their IL-15-heavy cytokine storms, and the type of damage to alveolar cells. Both might be driven by endoplasmic reticulum stress, they found.

“COVID-19 resembles IPF at a fundamental level,” they wrote.

Jeffrey Horowitz, MD, a pulmonologist and professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, said the need for early diagnosis is in part a function of the therapies available for ILD.

“They don’t make the lung function better,” he said. “So delays in diagnosis mean that there’s the possibility of underlying progression for months, or sometimes years, before the diagnosis is recognized.”

In an area in which diagnosis is delayed and the prognosis is dire – 3-5 years in untreated patients after diagnosis – “there’s a tremendous amount of nihilism out there” among patients, he said.

He said patients with long-term shortness of breath and unexplained cough are often told they have asthma and are prescribed inhalers, but then further assessment isn’t performed when those don’t work.

Diagnosing ILD in primary care

Many primary care physicians feel ill-equipped to discuss IPF. More than a dozen physicians contacted for this piece to talk about ILD either did not respond, or said they felt unqualified to respond to questions on the disease.

“Not my area of expertise” and “I don’t think I’m the right person for this discussion” were two of the responses provided to this news organization.

“For some reason, in the world of primary care, it seems like there’s an impediment to getting pulmonary function studies,” Dr. Horowitz said. “Anybody who has a persistent ongoing prolonged unexplained shortness of breath and cough should have pulmonary function studies done.”

Listening to the lungs alone might not be enough, he said. There might be no clear sign in the case of early pulmonary fibrosis, he said.

“There’s the textbook description of these Velcro-sounding crackles, but sometimes it’s very subtle,” he said. “And unless you’re listening very carefully it can easily be missed by somebody who has a busy practice, or it’s loud.”

William E. Golden, MD, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, is the sole primary care physician contacted for this piece who spoke with authority on ILD.

For cases of suspected ILD, internist Dr. Golden, who also serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News, suggested ordering a test for diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which will be low in the case of IPF, along with a fine-cut lung CT scan to assess ongoing fibrotic changes.

It’s “not that difficult, but you need to have an index of suspicion for the diagnosis,” he said.

New initiative for helping diagnose ILD

Dr. Kulkarni is a committee member for a new effort under way to try to get patients with ILD diagnosed earlier.

The initiative, called Bridging Specialties: Timely Diagnosis for ILD Patients, has already produced an introductory podcast and a white paper on the effort, and its rationale is expected to be released soon, according to Dr. Kulkarni and her fellow committee members.

The American College of Chest Physicians and the Three Lakes Foundation – a foundation dedicated to pulmonary fibrosis awareness and research – are working together on this initiative. They plan to put together a suite of resources, to be gradually rolled out on the college’s website, to raise awareness about the importance of early diagnosis of ILD.

The full toolkit, expected to be rolled out over the next 12 months, will include a series of podcasts and resources on how to get patients diagnosed earlier and steps to take in cases of suspected ILD, Dr. Kulkarni said.

“The goal would be to try to increase awareness about the disease so that people start thinking more about it up front – and not after we’ve ruled out everything else,” she said. The main audience will be primary care providers, but patients and community pulmonologists would likely also benefit from the resources, the committee members said.

The urgency of the initiative stems from the way ILD treatments work. They are antifibrotic, meaning they help prevent scar tissue from forming, but they can’t reverse scar tissue that has already formed. If scarring is severe, the only option might be a lung transplant, and, since the average age at ILD diagnosis is in the 60s, many patients have comorbidities that make them ineligible for transplant. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study mentioned earlier, the death rate per 100,000 people with ILD was 1.93 in 2017.

“The longer we take to diagnose it, the more chance that inflammation will become scar tissue,” Dr. Kularni explained.

William Lago, MD, another member of the committee and a family physician, said identifying ILD early is not a straightforward matter .

“When they first present, it’s hard to pick up,” said Dr. Lago, who is also a staff physician at Cleveland Clinic’s Wooster Family Health Center and medical director of the COVID Recover Clinic there. “Many of them, even themselves, will discount the symptoms.”

Dr. Lago said that patients might resist having a work-up even when a primary care physician identifies symptoms as possible ILD. In rural settings, they might have to travel quite a distance for a CT scan or other necessary evaluations, or they might just not think the symptoms are serious enough.

“Most of the time when I’ve picked up some of my pulmonary fibrosis patients, it’s been incidentally while they’re in the office for other things,” he said. He often has to “push the issue” for further work-up, he said.

The overlap of shortness of breath and cough with other, much more common disorders, such as heart disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), make ILD diagnosis a challenge, he said.

“For most of us, we’ve got sometimes 10 or 15 minutes with a patient who’s presenting with 5-6 different problems. And the shortness of breath or the occasional cough – that they think is nothing – is probably the least of those,” Dr. Lago said.

Dr. Golden said he suspected a tool like the one being developed by CHEST to be useful for some and not useful for others. He added that “no one has the time to spend on that kind of thing.”

Instead, he suggested just reinforcing what the core symptoms are and what the core testing is, “to make people think about it.”

Dr. Horowitiz seemed more optimistic about the likelihood of the CHEST tool being utilized to diagnose ILD.

Whether and how he would use the CHEST resource will depend on the final form it takes, Dr. Horowitz said. It’s encouraging that it’s being put together by a credible source, he added.

Dr. Kulkarni reported financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Aluda Pharmaceuticals and PureTech Lyt-100 Inc. Dr. Lago, Dr. Horowitz, and Dr. Golden reported no relevant disclosures.

Katie Lennon contributed to this report.

FDA okays spesolimab, first treatment for generalized pustular psoriasis

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biologic agent spesolimab (Spevigo) for the treatment of flares in adults with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), the company that manufactures the drug has announced.

Until this approval, “there were no FDA-approved options to treat patients experiencing a GPP flare,” Mark Lebwohl, MD, principal investigator in the pivotal spesolimab trial, told this news organization. The approval “is a turning point for dermatologists and clinicians who treat patients living with this devastating and debilitating disease,” he said. Treatment with spesolimab “rapidly improves the clinical symptoms of GPP flares and will greatly improve our ability to help our patients manage painful flares,” noted Dr. Lebwohl, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Spesolimab, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim, is a novel, selective monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-36 signaling known to be involved in GPP. It received priority review and had orphan drug and breakthrough therapy designation.

GPP affects an estimated 1 of every 10,000 people in the United States.

Though rare, GPP is a potentially life-threatening disease that is distinct from plaque psoriasis. GPP is caused by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin. Throughout the course of the disease, patients may suffer recurring episodes of widespread eruptions of painful, sterile pustules across all parts of the body.

Spesolimab was evaluated in a global, 12-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial that involved 53 adults experiencing a GPP flare. After 1 week, significantly more patients treated with spesolimab than placebo showed no visible pustules (54% vs 6%), according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions, seen in at least 5% of patients treated with spesolimab, were asthenia and fatigue; nausea and vomiting; headache; pruritus and prurigo; hematoma and bruising at the infusion site; and urinary tract infection.

Dr. Lebwohl is a paid consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 9/6/22.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biologic agent spesolimab (Spevigo) for the treatment of flares in adults with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), the company that manufactures the drug has announced.

Until this approval, “there were no FDA-approved options to treat patients experiencing a GPP flare,” Mark Lebwohl, MD, principal investigator in the pivotal spesolimab trial, told this news organization. The approval “is a turning point for dermatologists and clinicians who treat patients living with this devastating and debilitating disease,” he said. Treatment with spesolimab “rapidly improves the clinical symptoms of GPP flares and will greatly improve our ability to help our patients manage painful flares,” noted Dr. Lebwohl, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Spesolimab, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim, is a novel, selective monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-36 signaling known to be involved in GPP. It received priority review and had orphan drug and breakthrough therapy designation.

GPP affects an estimated 1 of every 10,000 people in the United States.

Though rare, GPP is a potentially life-threatening disease that is distinct from plaque psoriasis. GPP is caused by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin. Throughout the course of the disease, patients may suffer recurring episodes of widespread eruptions of painful, sterile pustules across all parts of the body.

Spesolimab was evaluated in a global, 12-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial that involved 53 adults experiencing a GPP flare. After 1 week, significantly more patients treated with spesolimab than placebo showed no visible pustules (54% vs 6%), according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions, seen in at least 5% of patients treated with spesolimab, were asthenia and fatigue; nausea and vomiting; headache; pruritus and prurigo; hematoma and bruising at the infusion site; and urinary tract infection.

Dr. Lebwohl is a paid consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 9/6/22.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biologic agent spesolimab (Spevigo) for the treatment of flares in adults with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), the company that manufactures the drug has announced.

Until this approval, “there were no FDA-approved options to treat patients experiencing a GPP flare,” Mark Lebwohl, MD, principal investigator in the pivotal spesolimab trial, told this news organization. The approval “is a turning point for dermatologists and clinicians who treat patients living with this devastating and debilitating disease,” he said. Treatment with spesolimab “rapidly improves the clinical symptoms of GPP flares and will greatly improve our ability to help our patients manage painful flares,” noted Dr. Lebwohl, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Spesolimab, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim, is a novel, selective monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-36 signaling known to be involved in GPP. It received priority review and had orphan drug and breakthrough therapy designation.

GPP affects an estimated 1 of every 10,000 people in the United States.

Though rare, GPP is a potentially life-threatening disease that is distinct from plaque psoriasis. GPP is caused by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin. Throughout the course of the disease, patients may suffer recurring episodes of widespread eruptions of painful, sterile pustules across all parts of the body.

Spesolimab was evaluated in a global, 12-week, placebo-controlled clinical trial that involved 53 adults experiencing a GPP flare. After 1 week, significantly more patients treated with spesolimab than placebo showed no visible pustules (54% vs 6%), according to the company.

The most common adverse reactions, seen in at least 5% of patients treated with spesolimab, were asthenia and fatigue; nausea and vomiting; headache; pruritus and prurigo; hematoma and bruising at the infusion site; and urinary tract infection.

Dr. Lebwohl is a paid consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 9/6/22.

Erlotinib promising for cancer prevention in familial adenomatous polyposis

“If existing data are confirmed and extended through future research, this strategy has the potential for substantial impact on clinical practice by decreasing, delaying, or augmenting endoscopic and surgical interventions as the mainstay for duodenal cancer prevention in this high-risk patient population,” the study team says.

FAP is a rare genetic condition that markedly raises the risk for colorectal polyps and cancer.

“The biological pathway that leads to the development of polyps and colon cancer in patients with FAP is the same biological pathway as patients in the general population,” study investigator Niloy Jewel Samadder, MD, with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in a news release.

“Our trial looked at opportunities to use chemoprevention agents in patients with FAP to inhibit the development of precancerous polyps in the small bowel and colorectum,” Dr. Samadder explains.

In an earlier study, the researchers found that the combination of the COX-2 inhibitor sulindac (150 mg twice daily) and erlotinib (75 mg daily) reduced duodenal polyp burden.

However, the dual-drug strategy was associated with a relatively high adverse event (AE) rate, which may limit use of the combination for chemoprevention, as reported previously.

This phase 2 study tested whether erlotinib’s AE profile would be improved with a once-weekly dosing schedule while still reducing polyp burden.

The study was first published online in the journal Gut.

In the single-arm, multicenter study, 46 adults with FAP (mean age, 44 years; 48% women) self-administered 350 mg of erlotinib by mouth one time per week for 6 months. All but four participants completed the 6-month study.

After 6 months of weekly erlotinib, duodenal polyp burden was significantly reduced, with a mean percent reduction of 29.6% (95% confidence interval: –39.6% to –19.7%; P < .0001).

The benefit was observed in patients with either Spigelman 2 or Spigelman 3 duodenal polyp burden.

“Though only 12% of patients noted a decrease in Spigelman stage from 3 to 2 associated with therapy, the majority of patients (86%) had stable disease while on treatment,” the study team reports.

GI polyp number (a secondary outcome) was also decreased after 6 months of treatment with erlotinib (median decrease of 30.8%; P = .0256).

While once-weekly erlotinib was “generally” well tolerated, grade 2 or 3 AEs were reported in 72% of patients; two suffered grade 3 toxicity. Nonetheless, the AE rate was significantly more than the expected null hypothesis rate of 50%, the study team states.

Four patients withdrew from the study because of drug-induced AEs, which included grade 3 rash acneiform, grade 2 infections (hand, foot, and mouth disease), grade 1 fatigue, and grade 1 rash acneiform. No grade 4 AEs were reported.

The most common AE was an erlotinib-induced acneiform-like rash, which occurred in 56.5% of study patients. The rash was managed with topical cortisone and/or clindamycin. Additional erlotinib-induced AEs included oral mucositis (6.5%), diarrhea (50%), and nausea (26.1%).

Summing up, Dr. Samadder and colleagues note that FAP “portends a heritable, systemic predisposition to cancer, and the ultimate goal of cancer preventive intervention is to interrupt the development of neoplasia, need for surgery, and ultimately death from cancer, with an acceptable AE profile.”

The findings from this phase 2 trial support further study of erlotinib as “an effective, acceptable cancer preventive agent for FAP-associated gastrointestinal polyposis,” they conclude.

The study was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Samadder is a consultant for Janssen Research and Development, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, and Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“If existing data are confirmed and extended through future research, this strategy has the potential for substantial impact on clinical practice by decreasing, delaying, or augmenting endoscopic and surgical interventions as the mainstay for duodenal cancer prevention in this high-risk patient population,” the study team says.

FAP is a rare genetic condition that markedly raises the risk for colorectal polyps and cancer.

“The biological pathway that leads to the development of polyps and colon cancer in patients with FAP is the same biological pathway as patients in the general population,” study investigator Niloy Jewel Samadder, MD, with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in a news release.

“Our trial looked at opportunities to use chemoprevention agents in patients with FAP to inhibit the development of precancerous polyps in the small bowel and colorectum,” Dr. Samadder explains.

In an earlier study, the researchers found that the combination of the COX-2 inhibitor sulindac (150 mg twice daily) and erlotinib (75 mg daily) reduced duodenal polyp burden.

However, the dual-drug strategy was associated with a relatively high adverse event (AE) rate, which may limit use of the combination for chemoprevention, as reported previously.

This phase 2 study tested whether erlotinib’s AE profile would be improved with a once-weekly dosing schedule while still reducing polyp burden.

The study was first published online in the journal Gut.

In the single-arm, multicenter study, 46 adults with FAP (mean age, 44 years; 48% women) self-administered 350 mg of erlotinib by mouth one time per week for 6 months. All but four participants completed the 6-month study.

After 6 months of weekly erlotinib, duodenal polyp burden was significantly reduced, with a mean percent reduction of 29.6% (95% confidence interval: –39.6% to –19.7%; P < .0001).

The benefit was observed in patients with either Spigelman 2 or Spigelman 3 duodenal polyp burden.

“Though only 12% of patients noted a decrease in Spigelman stage from 3 to 2 associated with therapy, the majority of patients (86%) had stable disease while on treatment,” the study team reports.

GI polyp number (a secondary outcome) was also decreased after 6 months of treatment with erlotinib (median decrease of 30.8%; P = .0256).

While once-weekly erlotinib was “generally” well tolerated, grade 2 or 3 AEs were reported in 72% of patients; two suffered grade 3 toxicity. Nonetheless, the AE rate was significantly more than the expected null hypothesis rate of 50%, the study team states.

Four patients withdrew from the study because of drug-induced AEs, which included grade 3 rash acneiform, grade 2 infections (hand, foot, and mouth disease), grade 1 fatigue, and grade 1 rash acneiform. No grade 4 AEs were reported.

The most common AE was an erlotinib-induced acneiform-like rash, which occurred in 56.5% of study patients. The rash was managed with topical cortisone and/or clindamycin. Additional erlotinib-induced AEs included oral mucositis (6.5%), diarrhea (50%), and nausea (26.1%).

Summing up, Dr. Samadder and colleagues note that FAP “portends a heritable, systemic predisposition to cancer, and the ultimate goal of cancer preventive intervention is to interrupt the development of neoplasia, need for surgery, and ultimately death from cancer, with an acceptable AE profile.”

The findings from this phase 2 trial support further study of erlotinib as “an effective, acceptable cancer preventive agent for FAP-associated gastrointestinal polyposis,” they conclude.

The study was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Samadder is a consultant for Janssen Research and Development, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, and Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“If existing data are confirmed and extended through future research, this strategy has the potential for substantial impact on clinical practice by decreasing, delaying, or augmenting endoscopic and surgical interventions as the mainstay for duodenal cancer prevention in this high-risk patient population,” the study team says.

FAP is a rare genetic condition that markedly raises the risk for colorectal polyps and cancer.

“The biological pathway that leads to the development of polyps and colon cancer in patients with FAP is the same biological pathway as patients in the general population,” study investigator Niloy Jewel Samadder, MD, with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in a news release.

“Our trial looked at opportunities to use chemoprevention agents in patients with FAP to inhibit the development of precancerous polyps in the small bowel and colorectum,” Dr. Samadder explains.

In an earlier study, the researchers found that the combination of the COX-2 inhibitor sulindac (150 mg twice daily) and erlotinib (75 mg daily) reduced duodenal polyp burden.

However, the dual-drug strategy was associated with a relatively high adverse event (AE) rate, which may limit use of the combination for chemoprevention, as reported previously.

This phase 2 study tested whether erlotinib’s AE profile would be improved with a once-weekly dosing schedule while still reducing polyp burden.

The study was first published online in the journal Gut.

In the single-arm, multicenter study, 46 adults with FAP (mean age, 44 years; 48% women) self-administered 350 mg of erlotinib by mouth one time per week for 6 months. All but four participants completed the 6-month study.

After 6 months of weekly erlotinib, duodenal polyp burden was significantly reduced, with a mean percent reduction of 29.6% (95% confidence interval: –39.6% to –19.7%; P < .0001).

The benefit was observed in patients with either Spigelman 2 or Spigelman 3 duodenal polyp burden.

“Though only 12% of patients noted a decrease in Spigelman stage from 3 to 2 associated with therapy, the majority of patients (86%) had stable disease while on treatment,” the study team reports.

GI polyp number (a secondary outcome) was also decreased after 6 months of treatment with erlotinib (median decrease of 30.8%; P = .0256).

While once-weekly erlotinib was “generally” well tolerated, grade 2 or 3 AEs were reported in 72% of patients; two suffered grade 3 toxicity. Nonetheless, the AE rate was significantly more than the expected null hypothesis rate of 50%, the study team states.

Four patients withdrew from the study because of drug-induced AEs, which included grade 3 rash acneiform, grade 2 infections (hand, foot, and mouth disease), grade 1 fatigue, and grade 1 rash acneiform. No grade 4 AEs were reported.

The most common AE was an erlotinib-induced acneiform-like rash, which occurred in 56.5% of study patients. The rash was managed with topical cortisone and/or clindamycin. Additional erlotinib-induced AEs included oral mucositis (6.5%), diarrhea (50%), and nausea (26.1%).

Summing up, Dr. Samadder and colleagues note that FAP “portends a heritable, systemic predisposition to cancer, and the ultimate goal of cancer preventive intervention is to interrupt the development of neoplasia, need for surgery, and ultimately death from cancer, with an acceptable AE profile.”

The findings from this phase 2 trial support further study of erlotinib as “an effective, acceptable cancer preventive agent for FAP-associated gastrointestinal polyposis,” they conclude.

The study was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Samadder is a consultant for Janssen Research and Development, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, and Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GUT

FDA approves first gene therapy, betibeglogene autotemcel (Zynteglo), for beta-thalassemia

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exaggerated Facial Lines on the Forehead and Cheeks

The Diagnosis: Pachydermoperiostosis

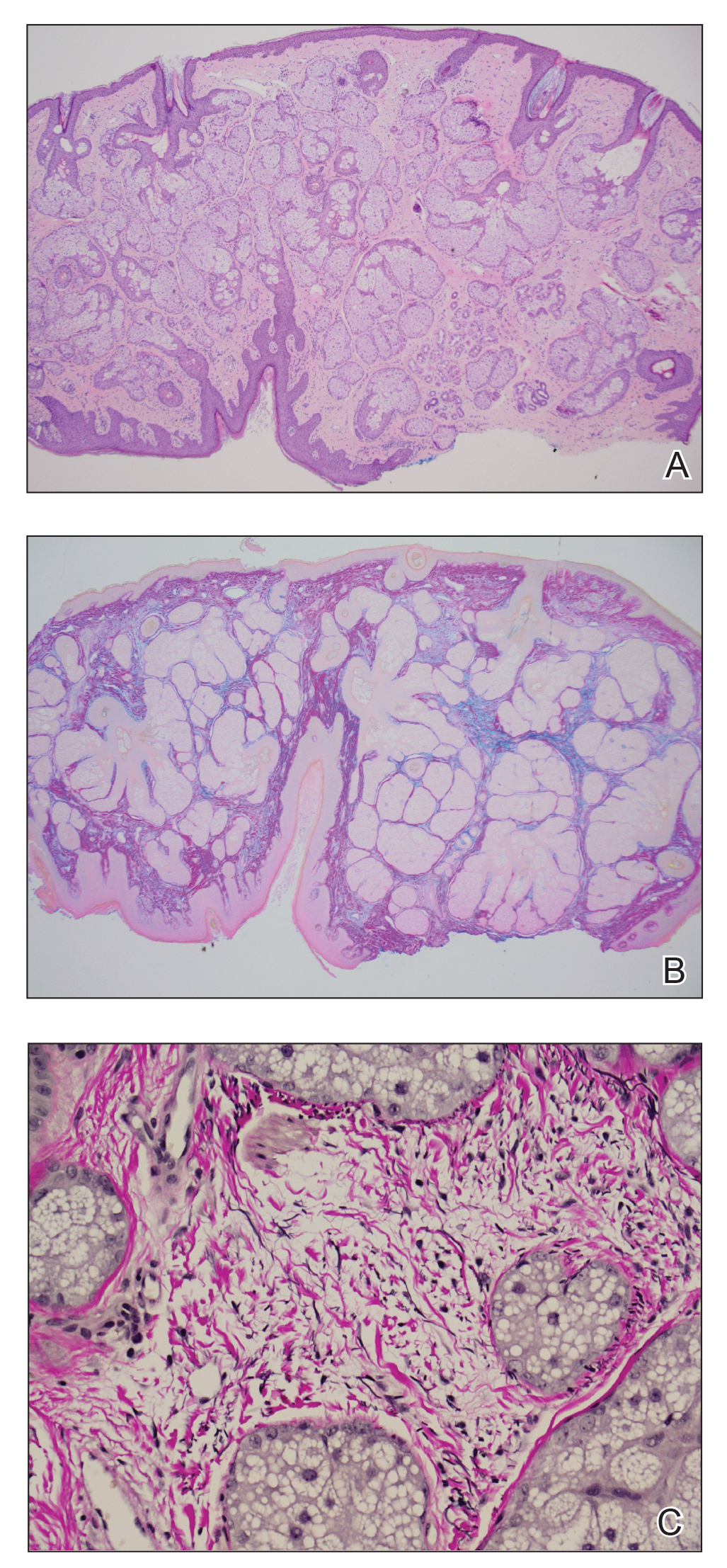

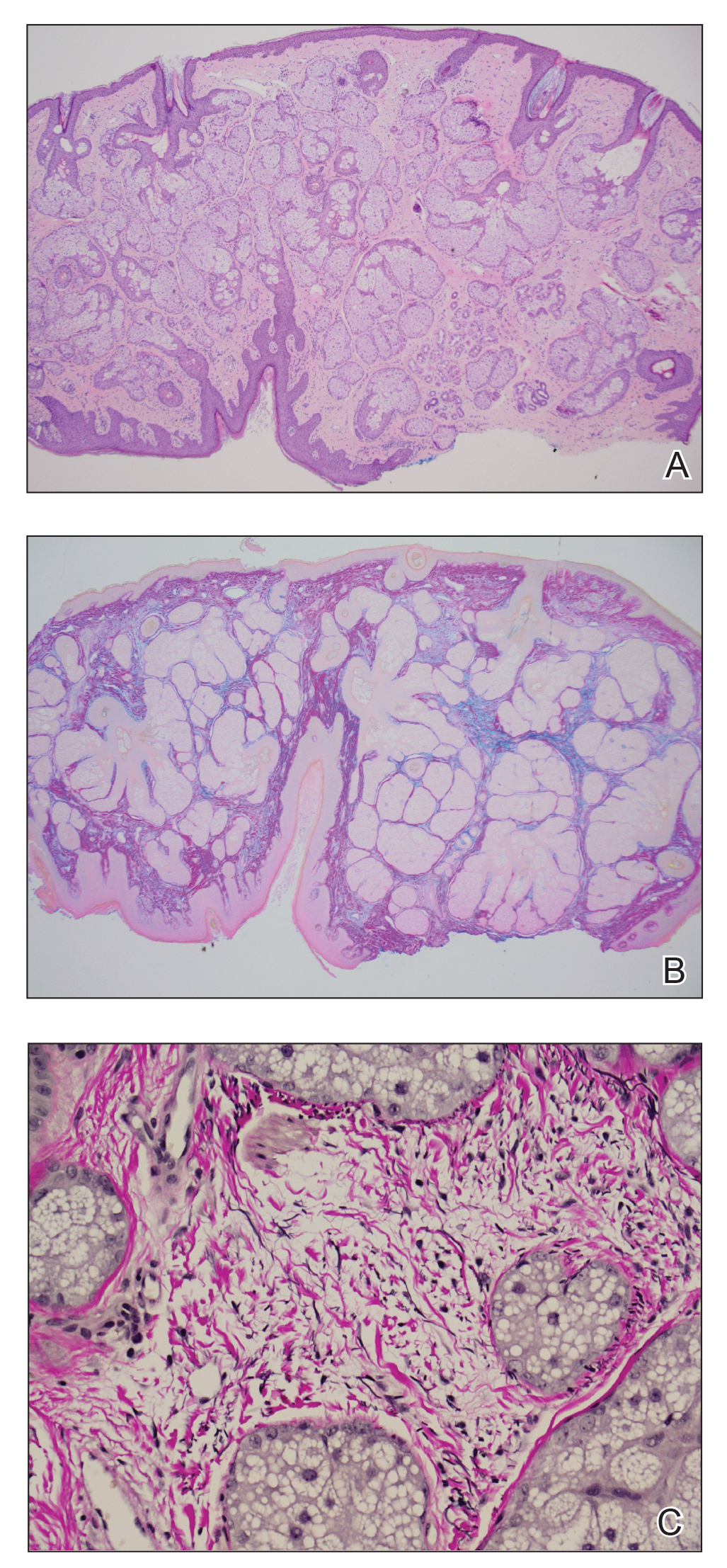

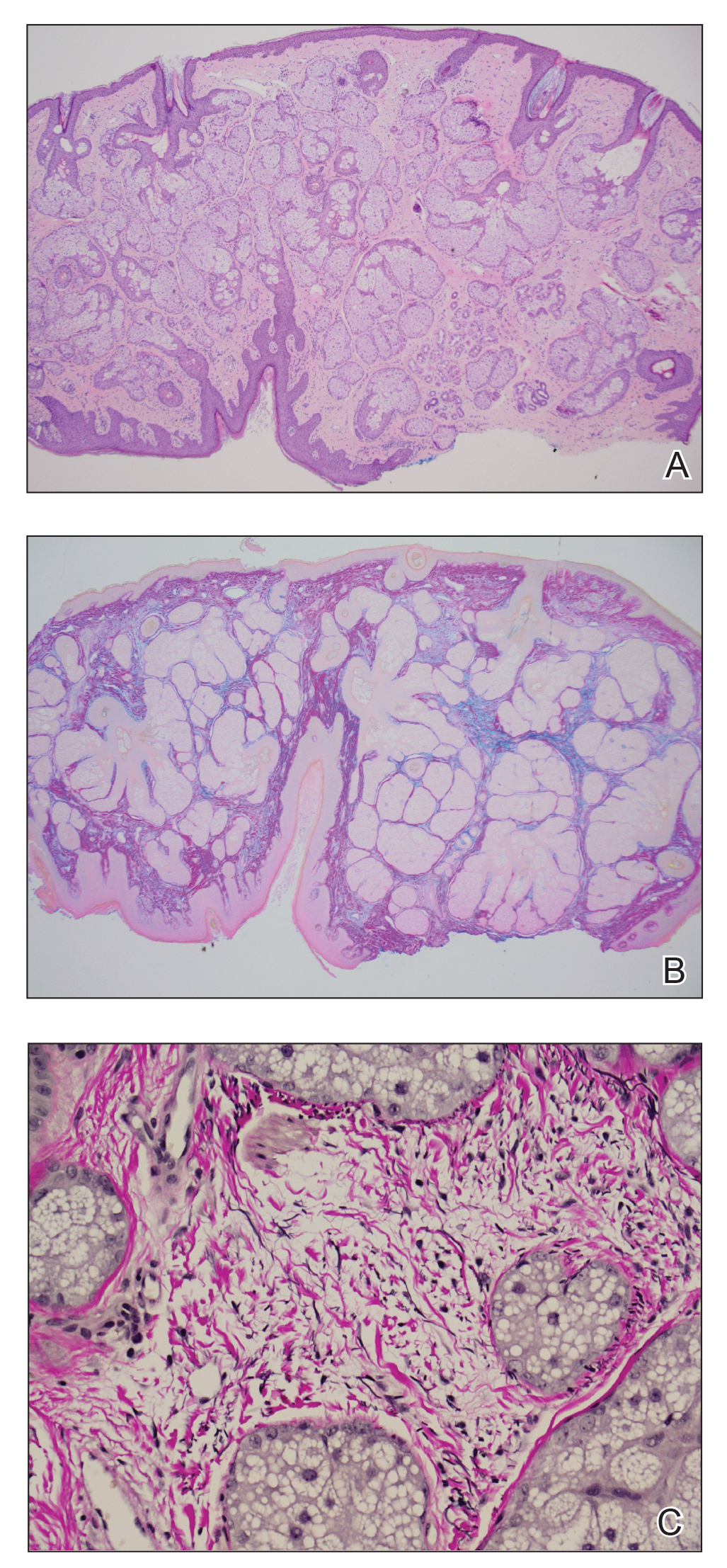

Histopathology of the forehead punch biopsy demonstrated sebaceous hyperplasia with an occupation rate of greater than 40%, increased mucin, elastic fiber degeneration, and fibrosis. Pachydermia is graded from 0 to 3 depending on the degree of these changes; our patient met criteria for grade 3 pachydermia (Figure 1). Radiography revealed diffuse cortical thickening of the long bones that was most marked in the left femur (Figure 2); however, no other findings were demonstrative of Paget disease.

Pachydermoperiostosis (PDP)(also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy) is a rare genetic condition that affects both the dermatologic and skeletal systems. Clinical features of the disease include progressive thickening and furrowing of the skin on the scalp and face (known as pachydermia), digital clubbing, and periostosis. Other potential cutaneous features include seborrhea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles, cutis verticis gyrata, eczema, and a burning sensation of the hands and feet. Myelofibrosis and gastrointestinal abnormalities also have been reported.1

The disease typically affects males (7:1 ratio); also, men typically display a more severe phenotype of the disease.2 It most commonly begins during puberty and follows a generally progressive course of 5 to 20 years before eventually stabilizing. Both autosomal-dominant with incomplete penetrance and recessive inheritance versions of PDP can occur. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PDP; PGE2 is important in the inflammatory response and may evolve from disrupted protein degradation pathways.3 Sasaki et al4 additionally reported that the severity of pachydermia clinically and histologically appeared to correlate with the serum PGE2 levels in affected patients. Prostaglandin E2 causes a vasodilatory effect, perhaps explaining the clubbing observed in PDP, and also modifies the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, causing the bone remodeling observed in the disease.4

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included PDP, as well as lepromatous leprosy, acromegaly, Paget disease of the bone, amyloidosis, scleromyxedema, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, the time course of the disease, lack of numerous symmetric thickened plaques and madarosis, and pathology argued against lepromatous leprosy. Acromegaly was ruled out due to lack of macroglossia as well as laboratory analysis within reference range including IGF-1 levels and thyroid function tests. Biopsy findings ultimately ruled out amyloidosis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The bone scan revealed diffuse cortical thickening consistent with PDP, and there were no other radiologic findings suggestive of Paget disease. Pachydermoperiostosis is diagnosed using the Borochowitz criteria, which entails that 2 of the following 4 fulfillment criteria must be met: familial transmission, pachydermia, digital clubbing, and/or bony involvement with evidence of radiologic alterations or pain. Our patient met all 4 criteria. The clinical manifestations of PDP are variable with respect to skin and bone changes. The various clinical expressions include the complete form (ie, pachydermia, cutis verticis gyrata, periostosis), the incomplete form (ie, absence of cutis verticis gyrata), and forme fruste (ie, pachydermia with minimal or absent periostosis).5

Management for PDP involves surgical correction for cosmesis as well as for functional concerns if present. Symptoms secondary to periostosis should be managed with symptomatic treatment such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Patients managed with etoricoxib, a COX-2–selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, have had normalized inflammatory markers that resulted in the lessening of forehead skin folds. Oral aescin has been shown to relieve joint pain due to its antiedematous effect.6 Our patient received treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for symptomatic management of the associated joint pain but unfortunately was lost to follow-up.

- Castori M, Sinibaldi L, Mingarelli R, et al. Pachydermoperiostosis: an update. Clin Genet. 2005;68:477-486.

- Reginato AJ, Shipachasse V, Guerrero R. Familial idiopathic hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and cranial suture defects in children. Skel Radiol. 1982;8:105-109.

- Coggins KG, Coffman TM, Koller BH. The Hippocratic finger points the blame at PGE2. Nat Genet. 2008;40:691-692.

- Sasaki T, Niizeki H, Shimizu A, et al. Identification of mutations in the prostaglandin transporter gene SLCO2A1 and its phenotype-genotype correlation in Japanese patients with pachydermoperiostosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68:36-44.

- Bhaskaranand K, Shetty RR, Bhat AK. Pachydermoperiostosis: three case reports. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2001;9:61-66.

- Zhang H, Yang B. Successful treatment of pachydermoperiostosis patients with etoricoxib, aescin, and arthroscopic synovectomy: two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E8865.

The Diagnosis: Pachydermoperiostosis

Histopathology of the forehead punch biopsy demonstrated sebaceous hyperplasia with an occupation rate of greater than 40%, increased mucin, elastic fiber degeneration, and fibrosis. Pachydermia is graded from 0 to 3 depending on the degree of these changes; our patient met criteria for grade 3 pachydermia (Figure 1). Radiography revealed diffuse cortical thickening of the long bones that was most marked in the left femur (Figure 2); however, no other findings were demonstrative of Paget disease.

Pachydermoperiostosis (PDP)(also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy) is a rare genetic condition that affects both the dermatologic and skeletal systems. Clinical features of the disease include progressive thickening and furrowing of the skin on the scalp and face (known as pachydermia), digital clubbing, and periostosis. Other potential cutaneous features include seborrhea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles, cutis verticis gyrata, eczema, and a burning sensation of the hands and feet. Myelofibrosis and gastrointestinal abnormalities also have been reported.1

The disease typically affects males (7:1 ratio); also, men typically display a more severe phenotype of the disease.2 It most commonly begins during puberty and follows a generally progressive course of 5 to 20 years before eventually stabilizing. Both autosomal-dominant with incomplete penetrance and recessive inheritance versions of PDP can occur. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PDP; PGE2 is important in the inflammatory response and may evolve from disrupted protein degradation pathways.3 Sasaki et al4 additionally reported that the severity of pachydermia clinically and histologically appeared to correlate with the serum PGE2 levels in affected patients. Prostaglandin E2 causes a vasodilatory effect, perhaps explaining the clubbing observed in PDP, and also modifies the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, causing the bone remodeling observed in the disease.4

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included PDP, as well as lepromatous leprosy, acromegaly, Paget disease of the bone, amyloidosis, scleromyxedema, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, the time course of the disease, lack of numerous symmetric thickened plaques and madarosis, and pathology argued against lepromatous leprosy. Acromegaly was ruled out due to lack of macroglossia as well as laboratory analysis within reference range including IGF-1 levels and thyroid function tests. Biopsy findings ultimately ruled out amyloidosis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The bone scan revealed diffuse cortical thickening consistent with PDP, and there were no other radiologic findings suggestive of Paget disease. Pachydermoperiostosis is diagnosed using the Borochowitz criteria, which entails that 2 of the following 4 fulfillment criteria must be met: familial transmission, pachydermia, digital clubbing, and/or bony involvement with evidence of radiologic alterations or pain. Our patient met all 4 criteria. The clinical manifestations of PDP are variable with respect to skin and bone changes. The various clinical expressions include the complete form (ie, pachydermia, cutis verticis gyrata, periostosis), the incomplete form (ie, absence of cutis verticis gyrata), and forme fruste (ie, pachydermia with minimal or absent periostosis).5

Management for PDP involves surgical correction for cosmesis as well as for functional concerns if present. Symptoms secondary to periostosis should be managed with symptomatic treatment such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Patients managed with etoricoxib, a COX-2–selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, have had normalized inflammatory markers that resulted in the lessening of forehead skin folds. Oral aescin has been shown to relieve joint pain due to its antiedematous effect.6 Our patient received treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for symptomatic management of the associated joint pain but unfortunately was lost to follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Pachydermoperiostosis

Histopathology of the forehead punch biopsy demonstrated sebaceous hyperplasia with an occupation rate of greater than 40%, increased mucin, elastic fiber degeneration, and fibrosis. Pachydermia is graded from 0 to 3 depending on the degree of these changes; our patient met criteria for grade 3 pachydermia (Figure 1). Radiography revealed diffuse cortical thickening of the long bones that was most marked in the left femur (Figure 2); however, no other findings were demonstrative of Paget disease.

Pachydermoperiostosis (PDP)(also known as Touraine-Solente-Golé syndrome or primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy) is a rare genetic condition that affects both the dermatologic and skeletal systems. Clinical features of the disease include progressive thickening and furrowing of the skin on the scalp and face (known as pachydermia), digital clubbing, and periostosis. Other potential cutaneous features include seborrhea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles, cutis verticis gyrata, eczema, and a burning sensation of the hands and feet. Myelofibrosis and gastrointestinal abnormalities also have been reported.1

The disease typically affects males (7:1 ratio); also, men typically display a more severe phenotype of the disease.2 It most commonly begins during puberty and follows a generally progressive course of 5 to 20 years before eventually stabilizing. Both autosomal-dominant with incomplete penetrance and recessive inheritance versions of PDP can occur. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PDP; PGE2 is important in the inflammatory response and may evolve from disrupted protein degradation pathways.3 Sasaki et al4 additionally reported that the severity of pachydermia clinically and histologically appeared to correlate with the serum PGE2 levels in affected patients. Prostaglandin E2 causes a vasodilatory effect, perhaps explaining the clubbing observed in PDP, and also modifies the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, causing the bone remodeling observed in the disease.4

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included PDP, as well as lepromatous leprosy, acromegaly, Paget disease of the bone, amyloidosis, scleromyxedema, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, the time course of the disease, lack of numerous symmetric thickened plaques and madarosis, and pathology argued against lepromatous leprosy. Acromegaly was ruled out due to lack of macroglossia as well as laboratory analysis within reference range including IGF-1 levels and thyroid function tests. Biopsy findings ultimately ruled out amyloidosis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The bone scan revealed diffuse cortical thickening consistent with PDP, and there were no other radiologic findings suggestive of Paget disease. Pachydermoperiostosis is diagnosed using the Borochowitz criteria, which entails that 2 of the following 4 fulfillment criteria must be met: familial transmission, pachydermia, digital clubbing, and/or bony involvement with evidence of radiologic alterations or pain. Our patient met all 4 criteria. The clinical manifestations of PDP are variable with respect to skin and bone changes. The various clinical expressions include the complete form (ie, pachydermia, cutis verticis gyrata, periostosis), the incomplete form (ie, absence of cutis verticis gyrata), and forme fruste (ie, pachydermia with minimal or absent periostosis).5

Management for PDP involves surgical correction for cosmesis as well as for functional concerns if present. Symptoms secondary to periostosis should be managed with symptomatic treatment such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Patients managed with etoricoxib, a COX-2–selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, have had normalized inflammatory markers that resulted in the lessening of forehead skin folds. Oral aescin has been shown to relieve joint pain due to its antiedematous effect.6 Our patient received treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for symptomatic management of the associated joint pain but unfortunately was lost to follow-up.

- Castori M, Sinibaldi L, Mingarelli R, et al. Pachydermoperiostosis: an update. Clin Genet. 2005;68:477-486.

- Reginato AJ, Shipachasse V, Guerrero R. Familial idiopathic hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and cranial suture defects in children. Skel Radiol. 1982;8:105-109.

- Coggins KG, Coffman TM, Koller BH. The Hippocratic finger points the blame at PGE2. Nat Genet. 2008;40:691-692.

- Sasaki T, Niizeki H, Shimizu A, et al. Identification of mutations in the prostaglandin transporter gene SLCO2A1 and its phenotype-genotype correlation in Japanese patients with pachydermoperiostosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68:36-44.

- Bhaskaranand K, Shetty RR, Bhat AK. Pachydermoperiostosis: three case reports. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2001;9:61-66.

- Zhang H, Yang B. Successful treatment of pachydermoperiostosis patients with etoricoxib, aescin, and arthroscopic synovectomy: two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E8865.

- Castori M, Sinibaldi L, Mingarelli R, et al. Pachydermoperiostosis: an update. Clin Genet. 2005;68:477-486.

- Reginato AJ, Shipachasse V, Guerrero R. Familial idiopathic hypertrophic osteoarthropathy and cranial suture defects in children. Skel Radiol. 1982;8:105-109.

- Coggins KG, Coffman TM, Koller BH. The Hippocratic finger points the blame at PGE2. Nat Genet. 2008;40:691-692.

- Sasaki T, Niizeki H, Shimizu A, et al. Identification of mutations in the prostaglandin transporter gene SLCO2A1 and its phenotype-genotype correlation in Japanese patients with pachydermoperiostosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68:36-44.

- Bhaskaranand K, Shetty RR, Bhat AK. Pachydermoperiostosis: three case reports. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2001;9:61-66.

- Zhang H, Yang B. Successful treatment of pachydermoperiostosis patients with etoricoxib, aescin, and arthroscopic synovectomy: two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E8865.

A 36-year-old man presented to the emergency department with an olecranon fracture after falling from a tree. The patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and a surgical history of facial cosmetic surgery. He underwent internal fixation with orthopedic surgery for the olecranon fracture, and dermatology subsequently was consulted due to diffuse skin changes on the face. He reported that these dermatologic changes began around 17 years of age and had progressed to the current presentation. He denied itching, burning, pain, or contact with armadillos. A family history revealed the patient’s brother also had a similar appearance. Physical examination revealed exaggerated facial lines on the forehead (top) and cheeks. Digital clubbing and skin thickening were noted on the hands (bottom) and feet; examination of the back revealed multiple hypopigmented patches. Observation of the scalp showed multiple symmetric ridges and grooves with sparse overlying hair consistent with cutis verticis gyrata. A punch biopsy of the forehead was obtained as well as bone radiography taken previously by the primary team.

Polio: The unwanted sequel

Summer, since 1975, is traditionally a time for the BIG blockbusters to hit theaters. Some are new, others are sequels in successful franchises. Some anticipated, some not as much.

And, in summer 2022, we have the least-wanted sequel in modern history – Polio II: The Return.

Of course, this sequel isn’t in the theaters (unless the concessions staff isn’t washing their hands), definitely isn’t funny, and could potentially cost a lot more money than the latest Marvel Cinematic Universe flick.

Personally and professionally, I’m in the middle generation on the disease. I’m young enough that I never had to worry about catching it or having afflicted classmates. But, as a doctor, I’m old enough to still see the consequences. Like most neurologists, I have a handful of patients who had childhood polio, and still deal with the chronic weakness (and consequent pain and orthopedic issues it brings). Signing off on braces and other mobility aids for them is still commonplace.

One of my attendings in residency was the renowned Parkinson’s disease expert Abraham Lieberman. On rounds it was impossible not to notice his marked limp, a consequence of childhood polio, and he’d tell us what it was like, being a 6-year-old boy and dealing with the disease. You learn as much from hearing firsthand experiences as you do from textbooks.

And now the virus is showing up again. A few victims, a lot of virions circulating in waste water, but it shouldn’t be there at all.

We aren’t in the era when schoolchildren died or were crippled by it. Elementary school kids today don’t see classmates catch polio and never return to school, or see their grieving parents.

To take 1 year: More than 3,000 American children died of polio in 1952, and more than 21,000 were left with lifelong paralysis – many of them still among us.

When you think of an iron lung, you think of polio.

Those were the casualties in a war to save future generations from this, along with smallpox and other horrors.

But today, that war is mostly forgotten. And now scientific evidence is drowned out by whatever’s on Facebook and the hard-earned miracle of vaccination is ignored in favor of a nonmedical “social influencer” on YouTube.

So The majority of the population likely has nothing to worry about. But there may be segments that are hit hard, and when they are they will never accept the obvious reasons why. It will be part of a cover-up, or a conspiracy, or whatever the guy on Parler told them it was.

As doctors, we’re in the middle. We have to give patients the best recommendations we can, based on learning, evidence, and experience, but at the same time have to recognize their autonomy. I’m not following someone around to make sure they get vaccinated, or take the medication I prescribed.

But we’re also the ones who can be held legally responsible for bad outcomes, regardless of the actual facts of the matter. On the flip side, you don’t hear about someone suing a Facebook “influencer” for doling out inaccurate, potentially fatal, medical advice.

So cracks appear in herd immunity, and leaks will happen.

A few generations of neurologists, including mine, have completed training without considering polio in a differential diagnosis. It would, of course, get bandied about in grand rounds or at the conference table, but none of us really took it seriously. To us residents it was more of historical note. “Gone with the Wind” and the “Wizard of Oz” both came out in 1939, and while we all knew of them, none of us were going to be watching them at the theaters.

Unlike them, though, polio is trying make it back to prime time. It’s a sequel nobody wanted.

But here it is.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Summer, since 1975, is traditionally a time for the BIG blockbusters to hit theaters. Some are new, others are sequels in successful franchises. Some anticipated, some not as much.

And, in summer 2022, we have the least-wanted sequel in modern history – Polio II: The Return.

Of course, this sequel isn’t in the theaters (unless the concessions staff isn’t washing their hands), definitely isn’t funny, and could potentially cost a lot more money than the latest Marvel Cinematic Universe flick.

Personally and professionally, I’m in the middle generation on the disease. I’m young enough that I never had to worry about catching it or having afflicted classmates. But, as a doctor, I’m old enough to still see the consequences. Like most neurologists, I have a handful of patients who had childhood polio, and still deal with the chronic weakness (and consequent pain and orthopedic issues it brings). Signing off on braces and other mobility aids for them is still commonplace.

One of my attendings in residency was the renowned Parkinson’s disease expert Abraham Lieberman. On rounds it was impossible not to notice his marked limp, a consequence of childhood polio, and he’d tell us what it was like, being a 6-year-old boy and dealing with the disease. You learn as much from hearing firsthand experiences as you do from textbooks.

And now the virus is showing up again. A few victims, a lot of virions circulating in waste water, but it shouldn’t be there at all.

We aren’t in the era when schoolchildren died or were crippled by it. Elementary school kids today don’t see classmates catch polio and never return to school, or see their grieving parents.

To take 1 year: More than 3,000 American children died of polio in 1952, and more than 21,000 were left with lifelong paralysis – many of them still among us.

When you think of an iron lung, you think of polio.

Those were the casualties in a war to save future generations from this, along with smallpox and other horrors.

But today, that war is mostly forgotten. And now scientific evidence is drowned out by whatever’s on Facebook and the hard-earned miracle of vaccination is ignored in favor of a nonmedical “social influencer” on YouTube.

So The majority of the population likely has nothing to worry about. But there may be segments that are hit hard, and when they are they will never accept the obvious reasons why. It will be part of a cover-up, or a conspiracy, or whatever the guy on Parler told them it was.

As doctors, we’re in the middle. We have to give patients the best recommendations we can, based on learning, evidence, and experience, but at the same time have to recognize their autonomy. I’m not following someone around to make sure they get vaccinated, or take the medication I prescribed.

But we’re also the ones who can be held legally responsible for bad outcomes, regardless of the actual facts of the matter. On the flip side, you don’t hear about someone suing a Facebook “influencer” for doling out inaccurate, potentially fatal, medical advice.

So cracks appear in herd immunity, and leaks will happen.

A few generations of neurologists, including mine, have completed training without considering polio in a differential diagnosis. It would, of course, get bandied about in grand rounds or at the conference table, but none of us really took it seriously. To us residents it was more of historical note. “Gone with the Wind” and the “Wizard of Oz” both came out in 1939, and while we all knew of them, none of us were going to be watching them at the theaters.

Unlike them, though, polio is trying make it back to prime time. It’s a sequel nobody wanted.

But here it is.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.