User login

FDA expands Xofluza indication to include postexposure flu prophylaxis

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

50.6 million tobacco users are not a homogeneous group

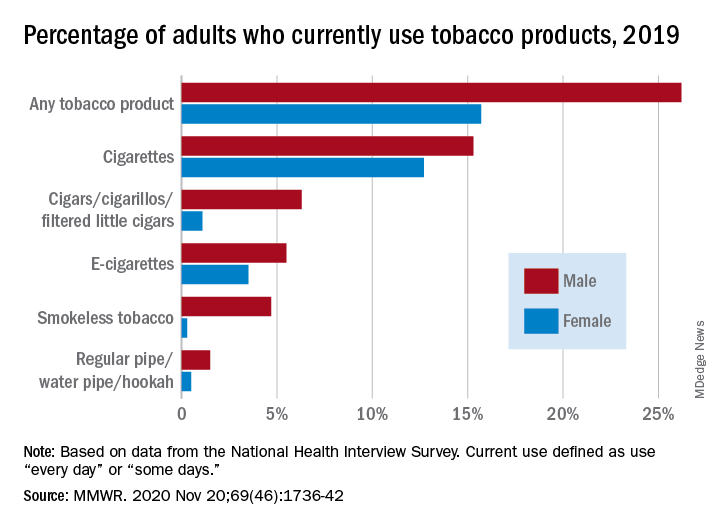

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

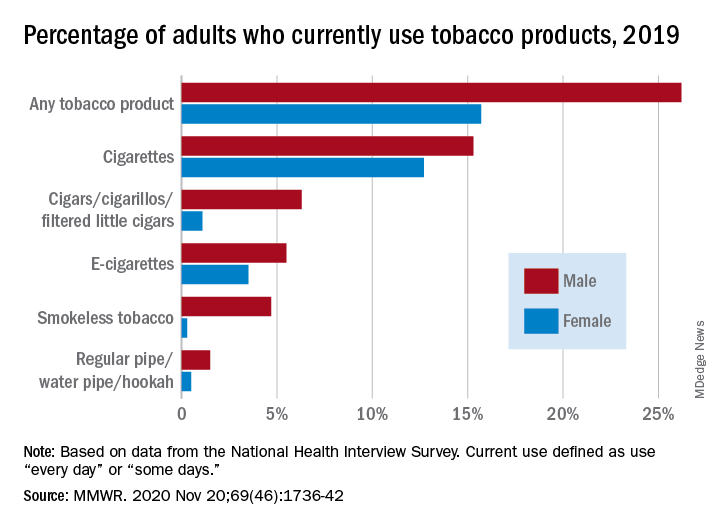

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

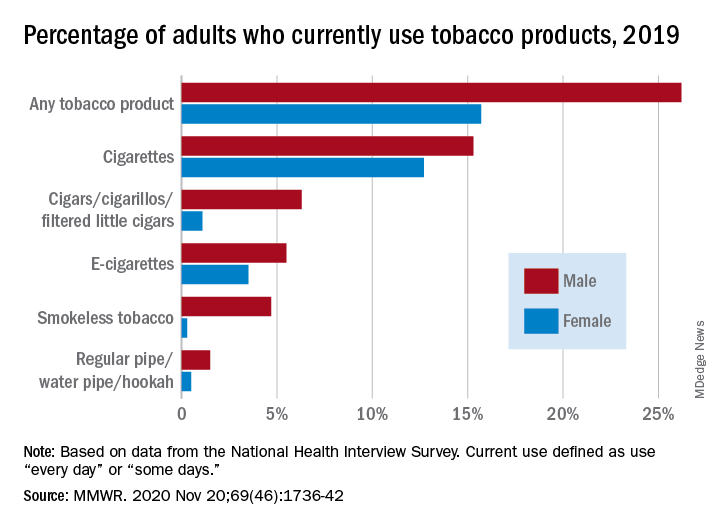

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

FROM MMWR

Liquid oxygen recommended for mobile patients with lung disease

People with chronic lung disease who need significant amounts of oxygen should be able to take it in liquid form when they are able to leave home, according to a new guideline from the American Thoracic Society.

“For those patients, often the other types of devices either can’t supply enough oxygen or are not portable enough,” said Anne Holland, PT, PhD, a professor of physiotherapy at Monash University and Alfred Hospital in Melbourne. “They’re heavy and cumbersome to use.”

Dr. Holland and colleagues also gave a more general recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen – though not necessarily in liquid form – for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or interstitial lung disease (ILD) who have severe exertional room air hypoxemia.

They published the recommendations as part of the ATS’ first-ever guideline on home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

The ATS identified the need for an updated guideline because of new research, and because an online survey of almost 2,000 U.S. oxygen users showed they were having problems accessing and using oxygen.

For long-term oxygen therapy, the guideline reinforces what most practitioners are already doing, Dr. Holland said. It recommends that adults with COPD or ILD who have severe chronic resting room air hypoxemia receive oxygen therapy at least 15 hours per day.

On the other hand, in adults with COPD who have moderate chronic resting room-air hypoxemia, the guideline recommends against long-term oxygen therapy.

The recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen for people with severe exertional room-air hypoxemia may have more effect on practice, Dr. Holland said. Laboratory-based tests have suggested oxygen can improve exercise capacity, but clinical trials used during daily life have had inconsistent results.

The evidence is particularly lacking for patients with ILD, Dr. Holland said in an interview. “It’s such an important part of practice to maintain oxygen therapy that it’s ethically very difficult to conduct such a trial. So, we did have to make use of indirect evidence from patients with COPD” for the guidelines.

The portable equipment comes with burdens, including managing its weight and bulk, social stigma, fear of cylinders running out, and equipment noise.

“We tried to clearly set out both the benefits and burdens of that therapy and made a conditional recommendation, and also a really strong call for shared decision-making with patients and health professionals,” Dr. Holland said.

In addition to looking at the evidence, the panel took into consideration the concerns identified by patients. This included the challenge of figuring out how to use the equipment. “All the oxygen equipment was ‘dumped’ on me,” wrote one oxygen user quoted in the guideline. “I knew nothing and was in a daze. I am sure that the delivery guy gave me some instructions when it was delivered but I retained nothing.”

For this reason, the guideline describes instruction and training on the use and maintenance of the equipment, including smoking cessation, fire prevention, and tripping hazards, as a “best practice.”

Nothing about the guideline is surprising, said MeiLan K. Han, MD, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association and professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “I don’t think they’ve actually come to any new conclusion,” she said in an interview. “This is pretty much how I practice already.”

But the guideline could have an effect on policy, she said. The panel noted research showing that lower Medicare reimbursement to durable medical equipment companies since 2011 has forced many patients to switch from small, easily portable liquid oxygen to home-fill oxygen systems that include heavy cylinders.

“The impact of this decline in the availability and adequacy of portable oxygen devices in the United States has been profound,” Dr. Holland and colleagues wrote. “Supplemental oxygen users reported numerous problems, with the overarching theme being restricted mobility and isolation due to inadequate portable options.”

For this reason, the guideline recommends liquid oxygen for patients with chronic lung disease who are mobile outside of the home and require continuous oxygen flow rates of >3 L/min during exertion.

Many of Dr. Han’s patients have struggled with this problem, she said. “The clunkiest, most painful form of ‘ambulatory oxygen’ are these really large metal cylinders. They’re huge. And you have to carry them on a cart. It’s portable in theory only.”

Some of her patients have resorted to buying their own equipment on eBay, she said.

The authors report multiple disclosures including serving as advisory board members to foundations and pharmaceutical companies, and some are company employees or stockholders.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People with chronic lung disease who need significant amounts of oxygen should be able to take it in liquid form when they are able to leave home, according to a new guideline from the American Thoracic Society.

“For those patients, often the other types of devices either can’t supply enough oxygen or are not portable enough,” said Anne Holland, PT, PhD, a professor of physiotherapy at Monash University and Alfred Hospital in Melbourne. “They’re heavy and cumbersome to use.”

Dr. Holland and colleagues also gave a more general recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen – though not necessarily in liquid form – for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or interstitial lung disease (ILD) who have severe exertional room air hypoxemia.

They published the recommendations as part of the ATS’ first-ever guideline on home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

The ATS identified the need for an updated guideline because of new research, and because an online survey of almost 2,000 U.S. oxygen users showed they were having problems accessing and using oxygen.

For long-term oxygen therapy, the guideline reinforces what most practitioners are already doing, Dr. Holland said. It recommends that adults with COPD or ILD who have severe chronic resting room air hypoxemia receive oxygen therapy at least 15 hours per day.

On the other hand, in adults with COPD who have moderate chronic resting room-air hypoxemia, the guideline recommends against long-term oxygen therapy.

The recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen for people with severe exertional room-air hypoxemia may have more effect on practice, Dr. Holland said. Laboratory-based tests have suggested oxygen can improve exercise capacity, but clinical trials used during daily life have had inconsistent results.

The evidence is particularly lacking for patients with ILD, Dr. Holland said in an interview. “It’s such an important part of practice to maintain oxygen therapy that it’s ethically very difficult to conduct such a trial. So, we did have to make use of indirect evidence from patients with COPD” for the guidelines.

The portable equipment comes with burdens, including managing its weight and bulk, social stigma, fear of cylinders running out, and equipment noise.

“We tried to clearly set out both the benefits and burdens of that therapy and made a conditional recommendation, and also a really strong call for shared decision-making with patients and health professionals,” Dr. Holland said.

In addition to looking at the evidence, the panel took into consideration the concerns identified by patients. This included the challenge of figuring out how to use the equipment. “All the oxygen equipment was ‘dumped’ on me,” wrote one oxygen user quoted in the guideline. “I knew nothing and was in a daze. I am sure that the delivery guy gave me some instructions when it was delivered but I retained nothing.”

For this reason, the guideline describes instruction and training on the use and maintenance of the equipment, including smoking cessation, fire prevention, and tripping hazards, as a “best practice.”

Nothing about the guideline is surprising, said MeiLan K. Han, MD, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association and professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “I don’t think they’ve actually come to any new conclusion,” she said in an interview. “This is pretty much how I practice already.”

But the guideline could have an effect on policy, she said. The panel noted research showing that lower Medicare reimbursement to durable medical equipment companies since 2011 has forced many patients to switch from small, easily portable liquid oxygen to home-fill oxygen systems that include heavy cylinders.

“The impact of this decline in the availability and adequacy of portable oxygen devices in the United States has been profound,” Dr. Holland and colleagues wrote. “Supplemental oxygen users reported numerous problems, with the overarching theme being restricted mobility and isolation due to inadequate portable options.”

For this reason, the guideline recommends liquid oxygen for patients with chronic lung disease who are mobile outside of the home and require continuous oxygen flow rates of >3 L/min during exertion.

Many of Dr. Han’s patients have struggled with this problem, she said. “The clunkiest, most painful form of ‘ambulatory oxygen’ are these really large metal cylinders. They’re huge. And you have to carry them on a cart. It’s portable in theory only.”

Some of her patients have resorted to buying their own equipment on eBay, she said.

The authors report multiple disclosures including serving as advisory board members to foundations and pharmaceutical companies, and some are company employees or stockholders.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People with chronic lung disease who need significant amounts of oxygen should be able to take it in liquid form when they are able to leave home, according to a new guideline from the American Thoracic Society.

“For those patients, often the other types of devices either can’t supply enough oxygen or are not portable enough,” said Anne Holland, PT, PhD, a professor of physiotherapy at Monash University and Alfred Hospital in Melbourne. “They’re heavy and cumbersome to use.”

Dr. Holland and colleagues also gave a more general recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen – though not necessarily in liquid form – for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or interstitial lung disease (ILD) who have severe exertional room air hypoxemia.

They published the recommendations as part of the ATS’ first-ever guideline on home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

The ATS identified the need for an updated guideline because of new research, and because an online survey of almost 2,000 U.S. oxygen users showed they were having problems accessing and using oxygen.

For long-term oxygen therapy, the guideline reinforces what most practitioners are already doing, Dr. Holland said. It recommends that adults with COPD or ILD who have severe chronic resting room air hypoxemia receive oxygen therapy at least 15 hours per day.

On the other hand, in adults with COPD who have moderate chronic resting room-air hypoxemia, the guideline recommends against long-term oxygen therapy.

The recommendation to prescribe ambulatory oxygen for people with severe exertional room-air hypoxemia may have more effect on practice, Dr. Holland said. Laboratory-based tests have suggested oxygen can improve exercise capacity, but clinical trials used during daily life have had inconsistent results.

The evidence is particularly lacking for patients with ILD, Dr. Holland said in an interview. “It’s such an important part of practice to maintain oxygen therapy that it’s ethically very difficult to conduct such a trial. So, we did have to make use of indirect evidence from patients with COPD” for the guidelines.

The portable equipment comes with burdens, including managing its weight and bulk, social stigma, fear of cylinders running out, and equipment noise.

“We tried to clearly set out both the benefits and burdens of that therapy and made a conditional recommendation, and also a really strong call for shared decision-making with patients and health professionals,” Dr. Holland said.

In addition to looking at the evidence, the panel took into consideration the concerns identified by patients. This included the challenge of figuring out how to use the equipment. “All the oxygen equipment was ‘dumped’ on me,” wrote one oxygen user quoted in the guideline. “I knew nothing and was in a daze. I am sure that the delivery guy gave me some instructions when it was delivered but I retained nothing.”

For this reason, the guideline describes instruction and training on the use and maintenance of the equipment, including smoking cessation, fire prevention, and tripping hazards, as a “best practice.”

Nothing about the guideline is surprising, said MeiLan K. Han, MD, a spokesperson for the American Lung Association and professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “I don’t think they’ve actually come to any new conclusion,” she said in an interview. “This is pretty much how I practice already.”

But the guideline could have an effect on policy, she said. The panel noted research showing that lower Medicare reimbursement to durable medical equipment companies since 2011 has forced many patients to switch from small, easily portable liquid oxygen to home-fill oxygen systems that include heavy cylinders.

“The impact of this decline in the availability and adequacy of portable oxygen devices in the United States has been profound,” Dr. Holland and colleagues wrote. “Supplemental oxygen users reported numerous problems, with the overarching theme being restricted mobility and isolation due to inadequate portable options.”

For this reason, the guideline recommends liquid oxygen for patients with chronic lung disease who are mobile outside of the home and require continuous oxygen flow rates of >3 L/min during exertion.

Many of Dr. Han’s patients have struggled with this problem, she said. “The clunkiest, most painful form of ‘ambulatory oxygen’ are these really large metal cylinders. They’re huge. And you have to carry them on a cart. It’s portable in theory only.”

Some of her patients have resorted to buying their own equipment on eBay, she said.

The authors report multiple disclosures including serving as advisory board members to foundations and pharmaceutical companies, and some are company employees or stockholders.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Rationale for baricitinib’s use in COVID-19 patients demonstrated

It should not be surprising that the RA drug baricitinib (Olumiant), a Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitor, might be beneficial in controlling the cytokine storm of hyperinflammation that can follow severe SARS-CoV-2 infections and lead to lung damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome – the leading cause of death from the virus.

But to demonstrate within a matter of months, at least preliminarily, that baricitinib reduces mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia required a widely cross-disciplinary international team of researchers from 10 countries working at breakneck speed, said Justin Stebbing, PhD, the principal investigator of a new baricitinib study published Nov. 13 in Science Advances. “We went from modeling and mechanistic investigations to clinical tests in a number of settings and laboratory analysis in record time.”

The international team of 50 researchers included medical specialists in rheumatology, virology, geriatrics, oncology, and general medicine, along with experts in molecular and cellular biology, bioinformatics, statistics and trial design, computer modeling, pathology, genetics, and super-resolution microscopy, Dr. Stebbing, professor of cancer medicine and medical oncology at Imperial College, London, said in an interview.

Artificial intelligence, provided by the London-based firm BenevolentAI, was used to sift through a huge repository of structured medical information to identify drugs that might block the SARS-CoV-2 infection process. It predicted that baricitinib would be a promising candidate to inhibit inflammation and reduce viral load in COVID-19. Previous reports by Dr. Stebbing and colleagues (here and here) describe this AI-mediated testing, which was validated by the new study.

The researchers also used three-dimensional miniature human liver organoids in vitro and super-resolution microscopy to perform further lab investigations, which showed that baricitinib reversed expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 triggered by type I interferons. Baricitinib inhibited the significant increase in ACE2 expression caused by interferon alpha-2, and thus cytokine-mediated inflammation, and also reduced infectivity, Dr. Stebbing said. “Our study of baricitinib shows that it has both antiviral and anticytokine effects and appears to be safe.”

71% mortality reduction

The team found a 71% reduction in mortality for a group of 83 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Italy and Spain – early epicenters of the pandemic – who received baricitinib along with standard care, compared with propensity-matched groups that received only standard care. At that time, between mid-March and mid-April, standard COVID-19 care included antibiotics, glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, low-molecular-weight heparin, and the antiretroviral combination lopinavir/ritonavir.

In the Spanish and Italian cohorts, baricitinib was generally well tolerated, although not without side effects, including bacterial infections and increases in liver enzyme levels, which may not have been related to baricitinib. Patients showed reductions in inflammation within days of starting treatment. “We did not observe thrombotic or vascular events in our cohorts, but most of the patients were receiving low molecular weight heparin,” he said.

The fact that baricitinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is already well studied for safety, can be taken conveniently as a once-daily oral tablet, and is less expensive than many other antiviral treatments all make it an good target for further study, including randomized, controlled trials that are already underway, Dr. Stebbing noted. His study cohort also included elderly patients (median age, 81 years) who are the most likely to experience severe disease or death from COVID-19.

The National Library of Medicine’s clinicaltrials.gov registry of federally funded clinical studies lists 15 current research initiatives involving baricitinib and COVID-19. Dr. Stebbing suggested that data generated so far are helping to guide ongoing studies on dose and duration of treatment – in other words, who it works for, when to give it, and at what dose it should be taken and for how long.

Manufacturer Eli Lilly, which markets baricitinib in 2-mg or 4-mg tablets, announced in October that initial data are starting to emerge from 1,000-plus patients enrolled in ACTT-2 (the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2). ACTT-2 compared patients on the broad-spectrum intravenous antiviral drug remdesivir (Veklury) with those receiving remdesivir in combination with baricitinib. Based on ACTT-2 results that suggested a reduced time to recovery and improved clinical outcomes for the combination group, the FDA issued an emergency-use authorization on Nov. 19 for the combination of baricitinib and remdesivir for the treatment of suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 in hospitalized adults and pediatric patients aged 2 years or older requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Interrupting the cytokine outbreak

Baricitinib has the potential to reduce or interrupt the passage of SARS-CoV-2 into cells, and thus to inhibit the JAK1- and JAK2-mediated cytokine outbreak, researcher Heinz-Josef Lenz, MD, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles, said in a comment. Baricitinib was also identified, using BenevolentAI’s proprietary, artificial intelligence-derived knowledge graph, as a numb-associated kinase inhibitor, with high affinity for AP2-associated protein kinase 1, an important endocytosis regulator.

Early clinical data suggest a potent biologic effect of baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg daily on circulating interleukin-6 levels and other inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein. Dr. Lenz said the evidence for advantageous action of baricitinib on viral endocytosis and excessive cytokine release constitutes the rationale for using it in combination with other antivirals such as remdesivir in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 illness.

“Although baricitinib may display antiviral activity on its own, its anti-inflammatory effects could hypothetically delay viral clearance,” Dr. Lenz added. “The data from Stebbing et al. confirm the dual actions of baricitinib, demonstrating its ability to inhibit viral entry into primary human hepatocyte spheroids and the reduction in inflammatory markers in COVID-19 patients.”

Other JAK inhibitors were not advanced as promising candidates for the research team’s attention by its artificial intelligence search, Dr. Stebbing noted. “The history of the pandemic has taught us the importance of well-designed observational studies as well as randomized, controlled trials. When it comes to COVID, pyrite looks much like gold, as failed studies of four antivirals have shown.”

Although the current translational research study did not use a placebo group, it is an important next step toward future randomized, controlled trials. “What’s great about this study is its high degree of collaboration, done with real urgency,” he added. “It’s harder to produce a paper that crosses multiple boundaries, like this one does, than a single-focused piece of work. But we wanted to link all of these threads together.”

The study was supported by the Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, the National Institute for Health Research, and the U.K. National Health Service’s Accelerated Access Collaborative. Dr. Stebbing has served on scientific advisory boards for Eli Lilly and other companies. Dr. Lenz had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Stebbing J et al. Sci Adv. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4724.

It should not be surprising that the RA drug baricitinib (Olumiant), a Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitor, might be beneficial in controlling the cytokine storm of hyperinflammation that can follow severe SARS-CoV-2 infections and lead to lung damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome – the leading cause of death from the virus.

But to demonstrate within a matter of months, at least preliminarily, that baricitinib reduces mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia required a widely cross-disciplinary international team of researchers from 10 countries working at breakneck speed, said Justin Stebbing, PhD, the principal investigator of a new baricitinib study published Nov. 13 in Science Advances. “We went from modeling and mechanistic investigations to clinical tests in a number of settings and laboratory analysis in record time.”

The international team of 50 researchers included medical specialists in rheumatology, virology, geriatrics, oncology, and general medicine, along with experts in molecular and cellular biology, bioinformatics, statistics and trial design, computer modeling, pathology, genetics, and super-resolution microscopy, Dr. Stebbing, professor of cancer medicine and medical oncology at Imperial College, London, said in an interview.

Artificial intelligence, provided by the London-based firm BenevolentAI, was used to sift through a huge repository of structured medical information to identify drugs that might block the SARS-CoV-2 infection process. It predicted that baricitinib would be a promising candidate to inhibit inflammation and reduce viral load in COVID-19. Previous reports by Dr. Stebbing and colleagues (here and here) describe this AI-mediated testing, which was validated by the new study.

The researchers also used three-dimensional miniature human liver organoids in vitro and super-resolution microscopy to perform further lab investigations, which showed that baricitinib reversed expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 triggered by type I interferons. Baricitinib inhibited the significant increase in ACE2 expression caused by interferon alpha-2, and thus cytokine-mediated inflammation, and also reduced infectivity, Dr. Stebbing said. “Our study of baricitinib shows that it has both antiviral and anticytokine effects and appears to be safe.”

71% mortality reduction

The team found a 71% reduction in mortality for a group of 83 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Italy and Spain – early epicenters of the pandemic – who received baricitinib along with standard care, compared with propensity-matched groups that received only standard care. At that time, between mid-March and mid-April, standard COVID-19 care included antibiotics, glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, low-molecular-weight heparin, and the antiretroviral combination lopinavir/ritonavir.

In the Spanish and Italian cohorts, baricitinib was generally well tolerated, although not without side effects, including bacterial infections and increases in liver enzyme levels, which may not have been related to baricitinib. Patients showed reductions in inflammation within days of starting treatment. “We did not observe thrombotic or vascular events in our cohorts, but most of the patients were receiving low molecular weight heparin,” he said.

The fact that baricitinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is already well studied for safety, can be taken conveniently as a once-daily oral tablet, and is less expensive than many other antiviral treatments all make it an good target for further study, including randomized, controlled trials that are already underway, Dr. Stebbing noted. His study cohort also included elderly patients (median age, 81 years) who are the most likely to experience severe disease or death from COVID-19.

The National Library of Medicine’s clinicaltrials.gov registry of federally funded clinical studies lists 15 current research initiatives involving baricitinib and COVID-19. Dr. Stebbing suggested that data generated so far are helping to guide ongoing studies on dose and duration of treatment – in other words, who it works for, when to give it, and at what dose it should be taken and for how long.

Manufacturer Eli Lilly, which markets baricitinib in 2-mg or 4-mg tablets, announced in October that initial data are starting to emerge from 1,000-plus patients enrolled in ACTT-2 (the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2). ACTT-2 compared patients on the broad-spectrum intravenous antiviral drug remdesivir (Veklury) with those receiving remdesivir in combination with baricitinib. Based on ACTT-2 results that suggested a reduced time to recovery and improved clinical outcomes for the combination group, the FDA issued an emergency-use authorization on Nov. 19 for the combination of baricitinib and remdesivir for the treatment of suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 in hospitalized adults and pediatric patients aged 2 years or older requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Interrupting the cytokine outbreak

Baricitinib has the potential to reduce or interrupt the passage of SARS-CoV-2 into cells, and thus to inhibit the JAK1- and JAK2-mediated cytokine outbreak, researcher Heinz-Josef Lenz, MD, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles, said in a comment. Baricitinib was also identified, using BenevolentAI’s proprietary, artificial intelligence-derived knowledge graph, as a numb-associated kinase inhibitor, with high affinity for AP2-associated protein kinase 1, an important endocytosis regulator.

Early clinical data suggest a potent biologic effect of baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg daily on circulating interleukin-6 levels and other inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein. Dr. Lenz said the evidence for advantageous action of baricitinib on viral endocytosis and excessive cytokine release constitutes the rationale for using it in combination with other antivirals such as remdesivir in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 illness.

“Although baricitinib may display antiviral activity on its own, its anti-inflammatory effects could hypothetically delay viral clearance,” Dr. Lenz added. “The data from Stebbing et al. confirm the dual actions of baricitinib, demonstrating its ability to inhibit viral entry into primary human hepatocyte spheroids and the reduction in inflammatory markers in COVID-19 patients.”

Other JAK inhibitors were not advanced as promising candidates for the research team’s attention by its artificial intelligence search, Dr. Stebbing noted. “The history of the pandemic has taught us the importance of well-designed observational studies as well as randomized, controlled trials. When it comes to COVID, pyrite looks much like gold, as failed studies of four antivirals have shown.”

Although the current translational research study did not use a placebo group, it is an important next step toward future randomized, controlled trials. “What’s great about this study is its high degree of collaboration, done with real urgency,” he added. “It’s harder to produce a paper that crosses multiple boundaries, like this one does, than a single-focused piece of work. But we wanted to link all of these threads together.”

The study was supported by the Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, the National Institute for Health Research, and the U.K. National Health Service’s Accelerated Access Collaborative. Dr. Stebbing has served on scientific advisory boards for Eli Lilly and other companies. Dr. Lenz had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Stebbing J et al. Sci Adv. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4724.

It should not be surprising that the RA drug baricitinib (Olumiant), a Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitor, might be beneficial in controlling the cytokine storm of hyperinflammation that can follow severe SARS-CoV-2 infections and lead to lung damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome – the leading cause of death from the virus.

But to demonstrate within a matter of months, at least preliminarily, that baricitinib reduces mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia required a widely cross-disciplinary international team of researchers from 10 countries working at breakneck speed, said Justin Stebbing, PhD, the principal investigator of a new baricitinib study published Nov. 13 in Science Advances. “We went from modeling and mechanistic investigations to clinical tests in a number of settings and laboratory analysis in record time.”

The international team of 50 researchers included medical specialists in rheumatology, virology, geriatrics, oncology, and general medicine, along with experts in molecular and cellular biology, bioinformatics, statistics and trial design, computer modeling, pathology, genetics, and super-resolution microscopy, Dr. Stebbing, professor of cancer medicine and medical oncology at Imperial College, London, said in an interview.

Artificial intelligence, provided by the London-based firm BenevolentAI, was used to sift through a huge repository of structured medical information to identify drugs that might block the SARS-CoV-2 infection process. It predicted that baricitinib would be a promising candidate to inhibit inflammation and reduce viral load in COVID-19. Previous reports by Dr. Stebbing and colleagues (here and here) describe this AI-mediated testing, which was validated by the new study.

The researchers also used three-dimensional miniature human liver organoids in vitro and super-resolution microscopy to perform further lab investigations, which showed that baricitinib reversed expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 triggered by type I interferons. Baricitinib inhibited the significant increase in ACE2 expression caused by interferon alpha-2, and thus cytokine-mediated inflammation, and also reduced infectivity, Dr. Stebbing said. “Our study of baricitinib shows that it has both antiviral and anticytokine effects and appears to be safe.”

71% mortality reduction

The team found a 71% reduction in mortality for a group of 83 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Italy and Spain – early epicenters of the pandemic – who received baricitinib along with standard care, compared with propensity-matched groups that received only standard care. At that time, between mid-March and mid-April, standard COVID-19 care included antibiotics, glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, low-molecular-weight heparin, and the antiretroviral combination lopinavir/ritonavir.

In the Spanish and Italian cohorts, baricitinib was generally well tolerated, although not without side effects, including bacterial infections and increases in liver enzyme levels, which may not have been related to baricitinib. Patients showed reductions in inflammation within days of starting treatment. “We did not observe thrombotic or vascular events in our cohorts, but most of the patients were receiving low molecular weight heparin,” he said.

The fact that baricitinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is already well studied for safety, can be taken conveniently as a once-daily oral tablet, and is less expensive than many other antiviral treatments all make it an good target for further study, including randomized, controlled trials that are already underway, Dr. Stebbing noted. His study cohort also included elderly patients (median age, 81 years) who are the most likely to experience severe disease or death from COVID-19.

The National Library of Medicine’s clinicaltrials.gov registry of federally funded clinical studies lists 15 current research initiatives involving baricitinib and COVID-19. Dr. Stebbing suggested that data generated so far are helping to guide ongoing studies on dose and duration of treatment – in other words, who it works for, when to give it, and at what dose it should be taken and for how long.

Manufacturer Eli Lilly, which markets baricitinib in 2-mg or 4-mg tablets, announced in October that initial data are starting to emerge from 1,000-plus patients enrolled in ACTT-2 (the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial 2). ACTT-2 compared patients on the broad-spectrum intravenous antiviral drug remdesivir (Veklury) with those receiving remdesivir in combination with baricitinib. Based on ACTT-2 results that suggested a reduced time to recovery and improved clinical outcomes for the combination group, the FDA issued an emergency-use authorization on Nov. 19 for the combination of baricitinib and remdesivir for the treatment of suspected or laboratory confirmed COVID-19 in hospitalized adults and pediatric patients aged 2 years or older requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Interrupting the cytokine outbreak

Baricitinib has the potential to reduce or interrupt the passage of SARS-CoV-2 into cells, and thus to inhibit the JAK1- and JAK2-mediated cytokine outbreak, researcher Heinz-Josef Lenz, MD, professor of medicine and preventive medicine at the University of Southern California’s Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles, said in a comment. Baricitinib was also identified, using BenevolentAI’s proprietary, artificial intelligence-derived knowledge graph, as a numb-associated kinase inhibitor, with high affinity for AP2-associated protein kinase 1, an important endocytosis regulator.

Early clinical data suggest a potent biologic effect of baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg daily on circulating interleukin-6 levels and other inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein. Dr. Lenz said the evidence for advantageous action of baricitinib on viral endocytosis and excessive cytokine release constitutes the rationale for using it in combination with other antivirals such as remdesivir in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 illness.

“Although baricitinib may display antiviral activity on its own, its anti-inflammatory effects could hypothetically delay viral clearance,” Dr. Lenz added. “The data from Stebbing et al. confirm the dual actions of baricitinib, demonstrating its ability to inhibit viral entry into primary human hepatocyte spheroids and the reduction in inflammatory markers in COVID-19 patients.”

Other JAK inhibitors were not advanced as promising candidates for the research team’s attention by its artificial intelligence search, Dr. Stebbing noted. “The history of the pandemic has taught us the importance of well-designed observational studies as well as randomized, controlled trials. When it comes to COVID, pyrite looks much like gold, as failed studies of four antivirals have shown.”

Although the current translational research study did not use a placebo group, it is an important next step toward future randomized, controlled trials. “What’s great about this study is its high degree of collaboration, done with real urgency,” he added. “It’s harder to produce a paper that crosses multiple boundaries, like this one does, than a single-focused piece of work. But we wanted to link all of these threads together.”

The study was supported by the Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, the National Institute for Health Research, and the U.K. National Health Service’s Accelerated Access Collaborative. Dr. Stebbing has served on scientific advisory boards for Eli Lilly and other companies. Dr. Lenz had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Stebbing J et al. Sci Adv. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4724.

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

Telehealth finds acceptance among patients with CF, clinicians

(CF) and the physicians who treat them, according to three new studies. The surveys examined attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic, which complicates interpretation of the survey, but the results nevertheless bode well for telehealth’s future in the management of CF.

“Patients could be responding positively just because they could have a visit during the pandemic,” said Andrew NeSmith, during a presentation of a survey of adults with CF at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. Mr. NeSmith is the clinical data coordinator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cystic Fibrosis Center.

Other posters at the conference examined attitudes among pediatric populations and treating physicians, with generally positive results, which has generated optimism that telehealth could become an important element of care after the pandemic fades. “This data suggests that telehealth could be integrated into routine follow-up care in the CF chronic care model,” said Mr. NeSmith.

His team collected responses from 119 individuals at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; Boston Children’s Hospital; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond; and West Virginia University, Morgantown. A total of 28% had conducted a prior telehealth visit before the study; 92% of visits were conducted with a medical doctor. Only 13% reported experiencing difficulties with their first telehealth visit. Eighty-five percent rated convenience, and 77% rated their satisfaction with telehealth as “high.” Most (92%) said they were able to see their desired disciplines, 95% felt all of their issues had been addressed, and 83% strongly agreed that telehealth visits were of adequate length.

Not everything was rosy. A total of 48% of participants expressed at least moderate concern over a lack of pulmonary function test or throat/sputum culture. There were much fewer concerns over missing vital signs or weight measurements.

The overall results weren’t surprising to Robert Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “I was expecting that patients were going to like it. It makes their life easier,” he said in an interview.

A survey of families of pediatric individuals with CF at seven centers found similar levels of satisfaction. A total of 23% had used telehealth previously; 96% rated convenience, and 93% rated satisfaction as “high.” Almost all (99%) felt that all concerns were met, 98% said that sessions were adequately long, and 87% had no trouble connecting to the visit.

Some participants in this survey had concerns about what might be missing with a televisit. Half (52%) had at least a moderate concern over lack of pulmonary function tests, 45% over lack of vital signs, 29% about lack of weight measurements, and 64% about the need for throat/sputum culture. Despite those issues, 69% preferred that “some” and 22% preferred that “most” future visits be conducted by telehealth.

A survey of physicians who used telehealth with CF patients also found broad support. They reported some challenges, with 70% saying they experienced technical difficulty, and 77% saying it “took time” to resolve a visit with only 18% reporting that visits were “quickly resolved.” Most (86%) said they were satisfied with telehealth for care delivery, and 78% said it was appropriate for most patients. Most said telehealth improved the patient-physician relationship, and they believed visits were more efficient when conducted via telehealth than in person. A majority (81%) endorsed using telehealth for some visits, and 12% for most visits.

A key question will be how telehealth affects patient outcomes, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, who was a coauthor of the survey of physicians. “If they’re not doing as well from an outcomes perspective, that would be a huge limitation to our patients,” said Dr. Perkins, who is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Although the study examined only models of care that were entirely virtual, Dr. Perkins noted that hybrid in-person/virtual care models are also possible. “Do we have better outcomes doing it that way? Is there higher patient satisfaction? I’m sure that will be a hot topic moving forward.”

Dr. Perkins noted that patients expressed concern about not being able to get sputum cultures and spirometry recordings during telehealth sessions. “That’s not really surprising to me, but I think it raises the question as we’re imagining care models for the future – how can we implement those components into future care delivery?”

Another hurdle will be insurance coverage. “My fear is that insurance companies are going to cut down the amount of reimbursement for telehealth visits in the future and just going to make it more complicated,” said Dr. Giusti. “Certainly, though, I think telehealth is an important outreach that we’d like to continue with our patients.”

Mr. NeSmith, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: NeSmith A et al. NACFC 2020, Abstracts 797, 799, 810.

(CF) and the physicians who treat them, according to three new studies. The surveys examined attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic, which complicates interpretation of the survey, but the results nevertheless bode well for telehealth’s future in the management of CF.

“Patients could be responding positively just because they could have a visit during the pandemic,” said Andrew NeSmith, during a presentation of a survey of adults with CF at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. Mr. NeSmith is the clinical data coordinator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cystic Fibrosis Center.

Other posters at the conference examined attitudes among pediatric populations and treating physicians, with generally positive results, which has generated optimism that telehealth could become an important element of care after the pandemic fades. “This data suggests that telehealth could be integrated into routine follow-up care in the CF chronic care model,” said Mr. NeSmith.

His team collected responses from 119 individuals at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; Boston Children’s Hospital; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond; and West Virginia University, Morgantown. A total of 28% had conducted a prior telehealth visit before the study; 92% of visits were conducted with a medical doctor. Only 13% reported experiencing difficulties with their first telehealth visit. Eighty-five percent rated convenience, and 77% rated their satisfaction with telehealth as “high.” Most (92%) said they were able to see their desired disciplines, 95% felt all of their issues had been addressed, and 83% strongly agreed that telehealth visits were of adequate length.

Not everything was rosy. A total of 48% of participants expressed at least moderate concern over a lack of pulmonary function test or throat/sputum culture. There were much fewer concerns over missing vital signs or weight measurements.

The overall results weren’t surprising to Robert Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “I was expecting that patients were going to like it. It makes their life easier,” he said in an interview.

A survey of families of pediatric individuals with CF at seven centers found similar levels of satisfaction. A total of 23% had used telehealth previously; 96% rated convenience, and 93% rated satisfaction as “high.” Almost all (99%) felt that all concerns were met, 98% said that sessions were adequately long, and 87% had no trouble connecting to the visit.

Some participants in this survey had concerns about what might be missing with a televisit. Half (52%) had at least a moderate concern over lack of pulmonary function tests, 45% over lack of vital signs, 29% about lack of weight measurements, and 64% about the need for throat/sputum culture. Despite those issues, 69% preferred that “some” and 22% preferred that “most” future visits be conducted by telehealth.

A survey of physicians who used telehealth with CF patients also found broad support. They reported some challenges, with 70% saying they experienced technical difficulty, and 77% saying it “took time” to resolve a visit with only 18% reporting that visits were “quickly resolved.” Most (86%) said they were satisfied with telehealth for care delivery, and 78% said it was appropriate for most patients. Most said telehealth improved the patient-physician relationship, and they believed visits were more efficient when conducted via telehealth than in person. A majority (81%) endorsed using telehealth for some visits, and 12% for most visits.

A key question will be how telehealth affects patient outcomes, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, who was a coauthor of the survey of physicians. “If they’re not doing as well from an outcomes perspective, that would be a huge limitation to our patients,” said Dr. Perkins, who is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Although the study examined only models of care that were entirely virtual, Dr. Perkins noted that hybrid in-person/virtual care models are also possible. “Do we have better outcomes doing it that way? Is there higher patient satisfaction? I’m sure that will be a hot topic moving forward.”

Dr. Perkins noted that patients expressed concern about not being able to get sputum cultures and spirometry recordings during telehealth sessions. “That’s not really surprising to me, but I think it raises the question as we’re imagining care models for the future – how can we implement those components into future care delivery?”

Another hurdle will be insurance coverage. “My fear is that insurance companies are going to cut down the amount of reimbursement for telehealth visits in the future and just going to make it more complicated,” said Dr. Giusti. “Certainly, though, I think telehealth is an important outreach that we’d like to continue with our patients.”

Mr. NeSmith, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: NeSmith A et al. NACFC 2020, Abstracts 797, 799, 810.

(CF) and the physicians who treat them, according to three new studies. The surveys examined attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic, which complicates interpretation of the survey, but the results nevertheless bode well for telehealth’s future in the management of CF.

“Patients could be responding positively just because they could have a visit during the pandemic,” said Andrew NeSmith, during a presentation of a survey of adults with CF at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference. Mr. NeSmith is the clinical data coordinator at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Cystic Fibrosis Center.

Other posters at the conference examined attitudes among pediatric populations and treating physicians, with generally positive results, which has generated optimism that telehealth could become an important element of care after the pandemic fades. “This data suggests that telehealth could be integrated into routine follow-up care in the CF chronic care model,” said Mr. NeSmith.

His team collected responses from 119 individuals at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; Boston Children’s Hospital; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston; Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond; and West Virginia University, Morgantown. A total of 28% had conducted a prior telehealth visit before the study; 92% of visits were conducted with a medical doctor. Only 13% reported experiencing difficulties with their first telehealth visit. Eighty-five percent rated convenience, and 77% rated their satisfaction with telehealth as “high.” Most (92%) said they were able to see their desired disciplines, 95% felt all of their issues had been addressed, and 83% strongly agreed that telehealth visits were of adequate length.

Not everything was rosy. A total of 48% of participants expressed at least moderate concern over a lack of pulmonary function test or throat/sputum culture. There were much fewer concerns over missing vital signs or weight measurements.

The overall results weren’t surprising to Robert Giusti, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics at New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center, New York, who was not involved in the study. “I was expecting that patients were going to like it. It makes their life easier,” he said in an interview.

A survey of families of pediatric individuals with CF at seven centers found similar levels of satisfaction. A total of 23% had used telehealth previously; 96% rated convenience, and 93% rated satisfaction as “high.” Almost all (99%) felt that all concerns were met, 98% said that sessions were adequately long, and 87% had no trouble connecting to the visit.

Some participants in this survey had concerns about what might be missing with a televisit. Half (52%) had at least a moderate concern over lack of pulmonary function tests, 45% over lack of vital signs, 29% about lack of weight measurements, and 64% about the need for throat/sputum culture. Despite those issues, 69% preferred that “some” and 22% preferred that “most” future visits be conducted by telehealth.

A survey of physicians who used telehealth with CF patients also found broad support. They reported some challenges, with 70% saying they experienced technical difficulty, and 77% saying it “took time” to resolve a visit with only 18% reporting that visits were “quickly resolved.” Most (86%) said they were satisfied with telehealth for care delivery, and 78% said it was appropriate for most patients. Most said telehealth improved the patient-physician relationship, and they believed visits were more efficient when conducted via telehealth than in person. A majority (81%) endorsed using telehealth for some visits, and 12% for most visits.

A key question will be how telehealth affects patient outcomes, according to Ryan Perkins, MD, who was a coauthor of the survey of physicians. “If they’re not doing as well from an outcomes perspective, that would be a huge limitation to our patients,” said Dr. Perkins, who is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Although the study examined only models of care that were entirely virtual, Dr. Perkins noted that hybrid in-person/virtual care models are also possible. “Do we have better outcomes doing it that way? Is there higher patient satisfaction? I’m sure that will be a hot topic moving forward.”

Dr. Perkins noted that patients expressed concern about not being able to get sputum cultures and spirometry recordings during telehealth sessions. “That’s not really surprising to me, but I think it raises the question as we’re imagining care models for the future – how can we implement those components into future care delivery?”

Another hurdle will be insurance coverage. “My fear is that insurance companies are going to cut down the amount of reimbursement for telehealth visits in the future and just going to make it more complicated,” said Dr. Giusti. “Certainly, though, I think telehealth is an important outreach that we’d like to continue with our patients.”

Mr. NeSmith, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: NeSmith A et al. NACFC 2020, Abstracts 797, 799, 810.

FROM NACFC 2020

Sleep apnea may correlate with anxiety, depression in patients with PCOS

a study suggests.

This finding could have implications for screening and treatment, Diana Xiaojie Zhou, MD, said at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

“Routine OSA screening in women with PCOS should be considered in the setting of existing depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Zhou, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. “Referral for OSA diagnosis and treatment in those who screen positive may have added psychological benefits in this population, as has been seen in the general population.”

Patients with PCOS experience a range of comorbidities, including higher rates of psychological disorders and OSA, she said.

OSA has been associated with depression and anxiety in the general population, and research indicates that treatment, such as with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may have psychological benefits, such as reduced depression symptoms.

PCOS guidelines recommend screening for OSA to identify and alleviate symptoms such as fatigue that may to contribute to mood disorders. “However, there is a lack of studies assessing the relationship between OSA and depression and anxiety specifically in women with PCOS,” Dr. Zhou said.

A cross-sectional study

To evaluate whether OSA is associated with depression and anxiety in women with PCOS, Dr. Zhou and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of all women seen at a multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at university between June 2017 and June 2020.

Participants had a diagnosis of PCOS clinically confirmed by the Rotterdam criteria. Researchers determined OSA risk using the Berlin questionnaire, which is divided into three domains. A positive score in two or more domains indicates a high risk of OSA.

The investigators used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression symptoms, and they used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to assess anxiety symptoms.

Researchers used two-sided t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test to evaluate for differences in patient characteristics. They performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of depression (that is, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) and anxiety (a GAD-7 score of 10 or greater) among patients with a high risk of OSA, compared with patients with a low risk of OSA. They adjusted for age, body mass index, free testosterone level, and insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR).

The researchers examined data from 201 patients: 125 with a low risk of OSA and 76 with a high risk of OSA. The average age of the patients was 28 years.

On average, patients in the high-risk OSA group had a greater body mass index (37.9 vs. 26.5), a higher level of free testosterone (6.5 ng/dL vs. 4.5 ng/dL), and a higher HOMA-IR score (7 vs. 3.1), relative to those with a low risk of OSA. In addition, a greater percentage of patients with a high risk of OSA experienced oligomenorrhea (84.9% vs. 70.5%).

The average PHQ-9 score was significantly higher in the high-risk OSA group (12 vs. 8.3), as was the average GAD-7 score (8.9 vs. 6.1).

In univariate analyses, having a high risk of OSA increased the likelihood of moderate or severe depression or anxiety approximately threefold.

In multivariate analyses, a high risk of OSA remained significantly associated with moderate or severe depression or anxiety, with an odds ratio of about 2.5. “Of note, BMI was a statistically significant predictor in the univariate analyses, but not so in the multivariate analyses,” Dr. Zhou said.

Although the investigators assessed OSA, depression, and anxiety using validated questionnaires, a study with clinically confirmed diagnoses of those conditions would strengthen these findings, she said.

Various possible links

Investigators have proposed various links between PCOS, OSA, and depression and anxiety, Dr. Zhou noted. Features of PCOS such as insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia increase the risk of OSA. “The sleep loss and fragmentation and hypoxia that define OSA then serve to increase sympathetic tone and oxidative stress, which then potentially can lead to an increase in depression and anxiety,” Dr. Zhou said.

The results suggests that treating OSA “may have added psychological benefits for women with PCOS and highlights the broad health implications of this condition,” Marla Lujan, PhD, chair of the ASRM’s androgen excess special interest group, said in a society news release.

“The cause of PCOS is still not well understood, but we do know that 1 in 10 women in their childbearing years suffer from PCOS,” said Dr. Lujan, of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “In addition to infertility, PCOS is also associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and abnormal blood lipids.”

In a discussion following Dr. Zhou’s presentation, Alice D. Domar, PhD, said the study was eye opening.

Dr. Domar, director of integrative care at Boston IVF and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that she does not typically discuss sleep apnea with patients. “For those of us who routinely work with PCOS patients, we are always looking for more information.”

Although PCOS guidelines mention screening for OSA, Dr. Zhou expects that few generalists who see PCOS patients or even subspecialists actually do.

Nevertheless, the potential for intervention is fascinating, she said. And if treating OSA also reduced a patient’s need for psychiatric medications, there could be added benefit in PCOS due to the metabolic side effects that accompany some of the drugs.

Dr. Zhou and Dr. Lujan had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Domar is a co-owner of FertiCalm, FertiStrong, and Aliz Health Apps, and a speaker for Ferring, EMD Serono, Merck, and Abbott.

SOURCE: Zhou DX et al. ASRM 2020. Abstract O-146.

a study suggests.

This finding could have implications for screening and treatment, Diana Xiaojie Zhou, MD, said at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

“Routine OSA screening in women with PCOS should be considered in the setting of existing depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Zhou, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. “Referral for OSA diagnosis and treatment in those who screen positive may have added psychological benefits in this population, as has been seen in the general population.”

Patients with PCOS experience a range of comorbidities, including higher rates of psychological disorders and OSA, she said.

OSA has been associated with depression and anxiety in the general population, and research indicates that treatment, such as with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may have psychological benefits, such as reduced depression symptoms.

PCOS guidelines recommend screening for OSA to identify and alleviate symptoms such as fatigue that may to contribute to mood disorders. “However, there is a lack of studies assessing the relationship between OSA and depression and anxiety specifically in women with PCOS,” Dr. Zhou said.

A cross-sectional study

To evaluate whether OSA is associated with depression and anxiety in women with PCOS, Dr. Zhou and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of all women seen at a multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at university between June 2017 and June 2020.

Participants had a diagnosis of PCOS clinically confirmed by the Rotterdam criteria. Researchers determined OSA risk using the Berlin questionnaire, which is divided into three domains. A positive score in two or more domains indicates a high risk of OSA.

The investigators used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression symptoms, and they used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to assess anxiety symptoms.

Researchers used two-sided t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test to evaluate for differences in patient characteristics. They performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of depression (that is, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) and anxiety (a GAD-7 score of 10 or greater) among patients with a high risk of OSA, compared with patients with a low risk of OSA. They adjusted for age, body mass index, free testosterone level, and insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR).

The researchers examined data from 201 patients: 125 with a low risk of OSA and 76 with a high risk of OSA. The average age of the patients was 28 years.

On average, patients in the high-risk OSA group had a greater body mass index (37.9 vs. 26.5), a higher level of free testosterone (6.5 ng/dL vs. 4.5 ng/dL), and a higher HOMA-IR score (7 vs. 3.1), relative to those with a low risk of OSA. In addition, a greater percentage of patients with a high risk of OSA experienced oligomenorrhea (84.9% vs. 70.5%).

The average PHQ-9 score was significantly higher in the high-risk OSA group (12 vs. 8.3), as was the average GAD-7 score (8.9 vs. 6.1).

In univariate analyses, having a high risk of OSA increased the likelihood of moderate or severe depression or anxiety approximately threefold.

In multivariate analyses, a high risk of OSA remained significantly associated with moderate or severe depression or anxiety, with an odds ratio of about 2.5. “Of note, BMI was a statistically significant predictor in the univariate analyses, but not so in the multivariate analyses,” Dr. Zhou said.

Although the investigators assessed OSA, depression, and anxiety using validated questionnaires, a study with clinically confirmed diagnoses of those conditions would strengthen these findings, she said.

Various possible links

Investigators have proposed various links between PCOS, OSA, and depression and anxiety, Dr. Zhou noted. Features of PCOS such as insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia increase the risk of OSA. “The sleep loss and fragmentation and hypoxia that define OSA then serve to increase sympathetic tone and oxidative stress, which then potentially can lead to an increase in depression and anxiety,” Dr. Zhou said.

The results suggests that treating OSA “may have added psychological benefits for women with PCOS and highlights the broad health implications of this condition,” Marla Lujan, PhD, chair of the ASRM’s androgen excess special interest group, said in a society news release.

“The cause of PCOS is still not well understood, but we do know that 1 in 10 women in their childbearing years suffer from PCOS,” said Dr. Lujan, of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “In addition to infertility, PCOS is also associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and abnormal blood lipids.”

In a discussion following Dr. Zhou’s presentation, Alice D. Domar, PhD, said the study was eye opening.