User login

Understanding messenger RNA and other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

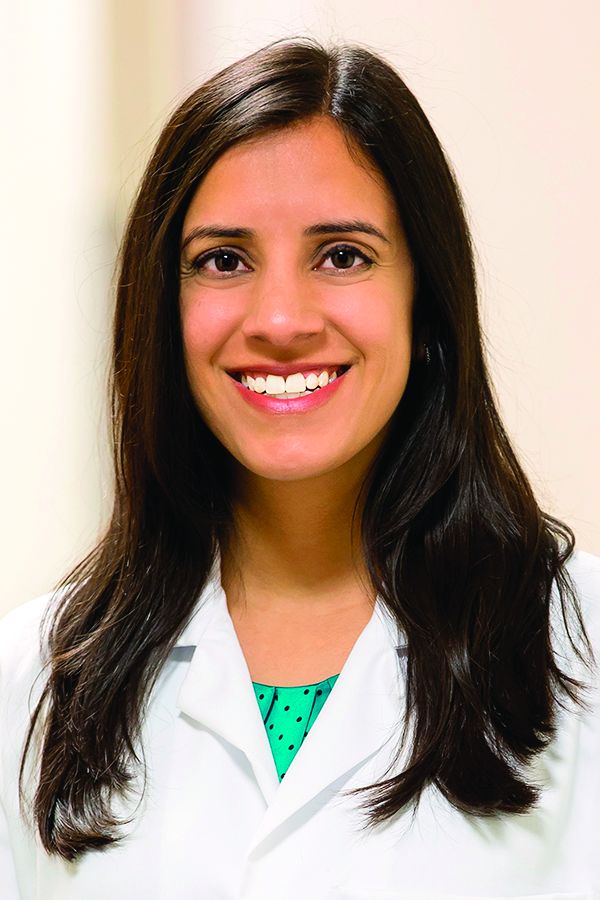

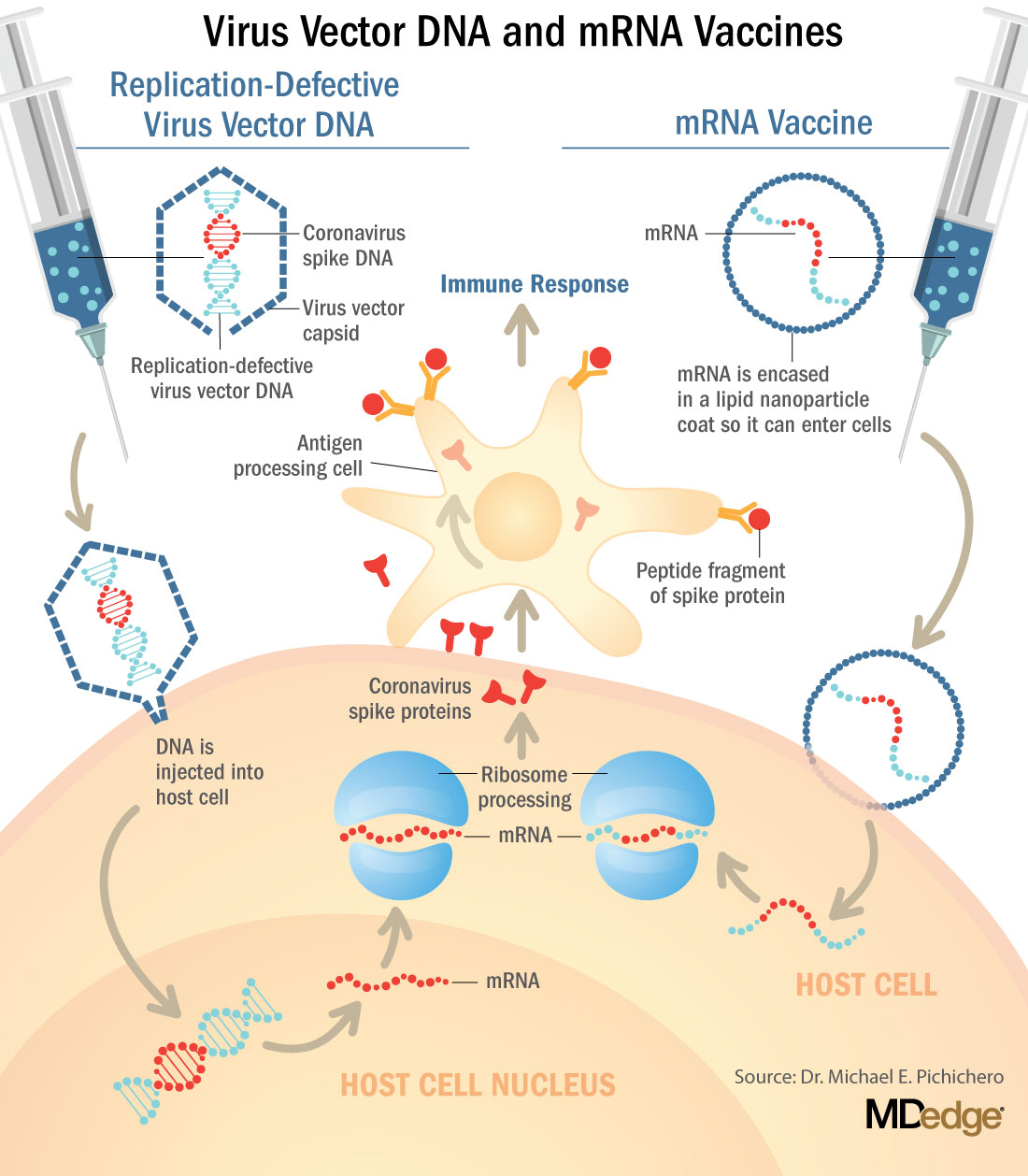

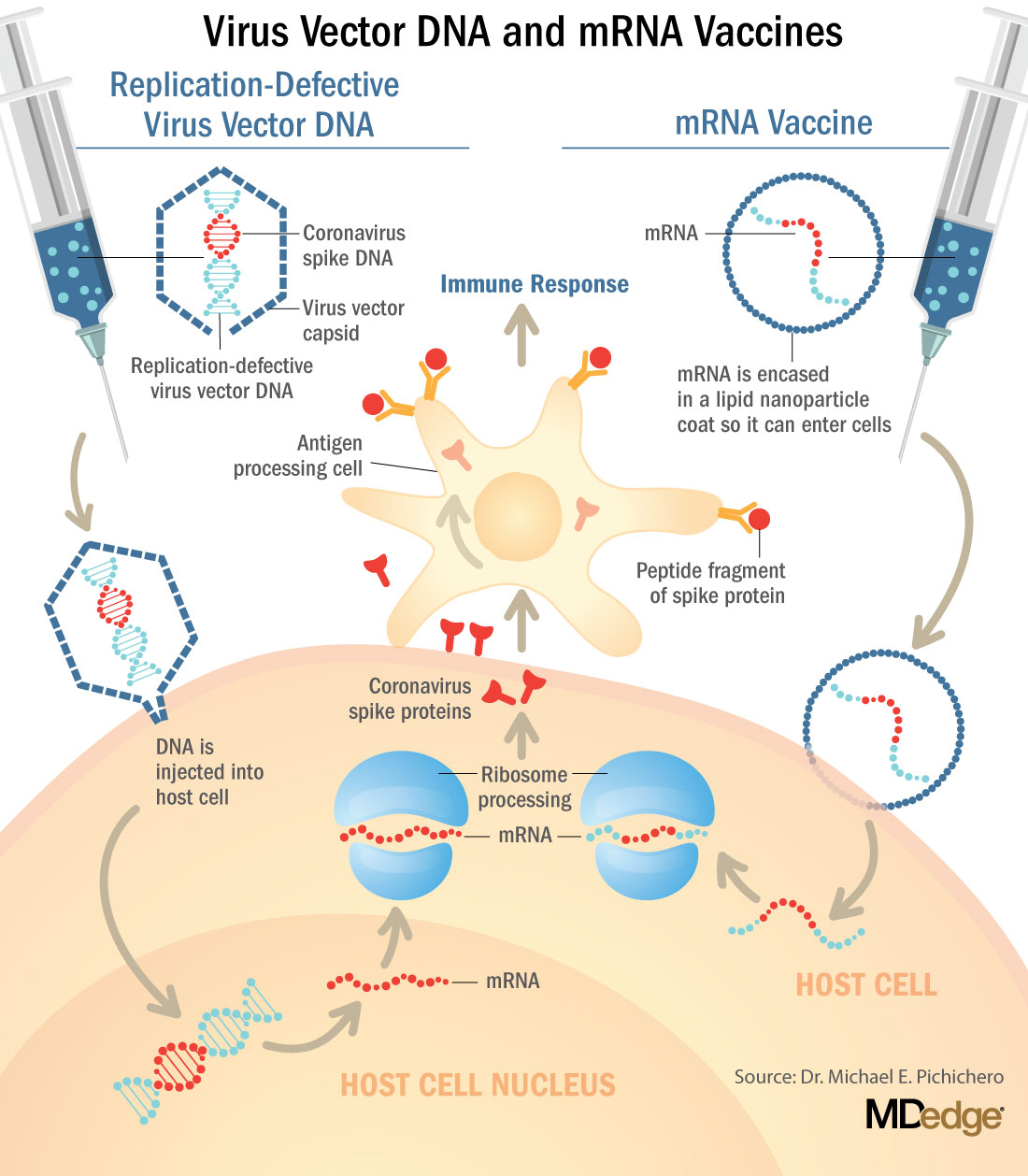

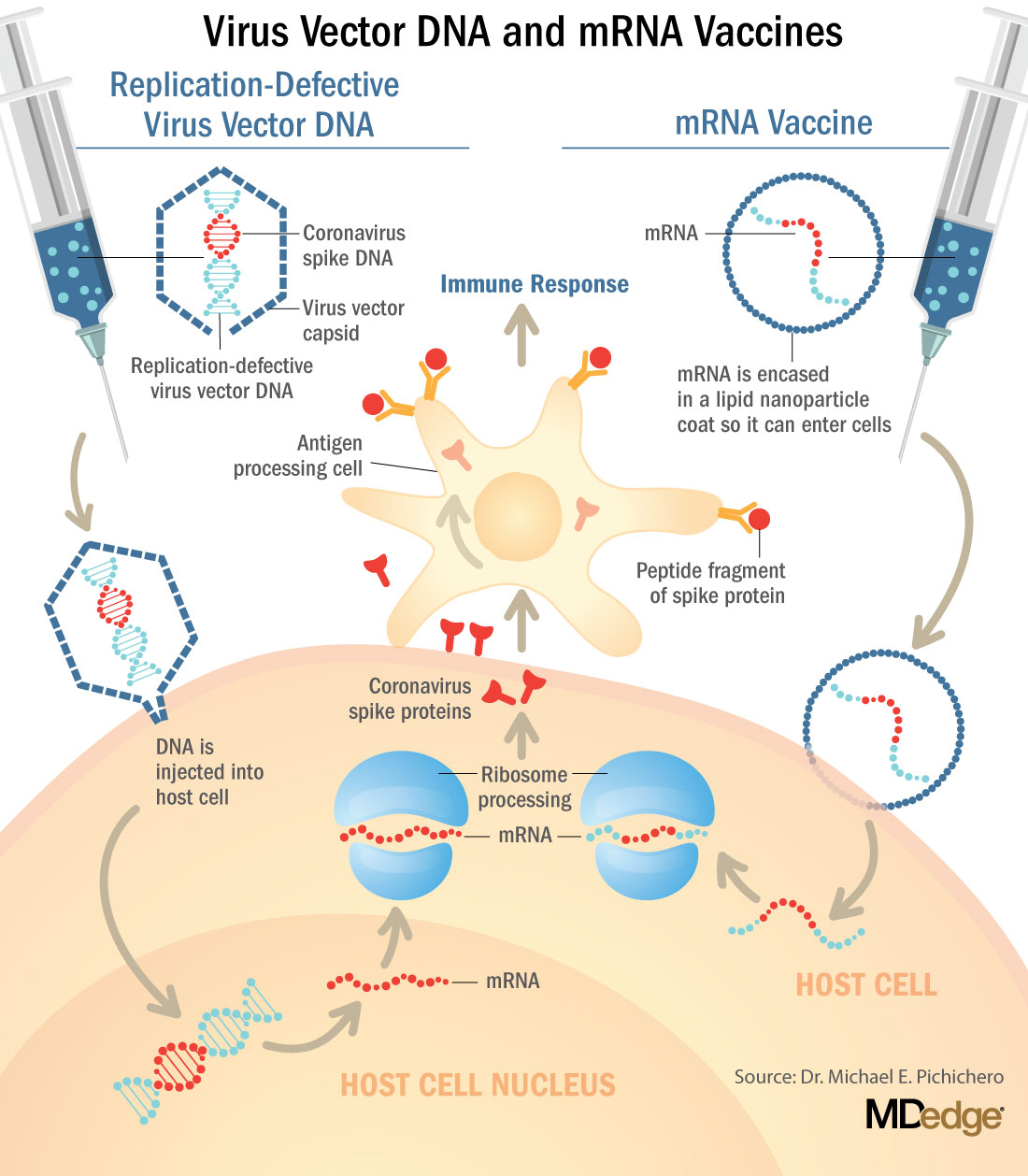

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

How to identify and treat common bites and stings

Insect, arachnid, and other arthropod bites and stings are common patient complaints in a primary care office. A thorough history and physical exam can often isolate the specific offender and guide management. In this article, we outline how to identify, diagnose, and treat common bites and stings from bees and wasps; centipedes and spiders; fleas; flies and biting midges; mosquitoes; and ticks, and discuss how high-risk patients should be triaged and referred for additional testing and treatment, such as venom immunotherapy (VIT).

Insects and arachnids:Background and epidemiology

Insects are arthropods with 3-part exoskeletons: head, thorax, and abdomen. They have 6 jointed legs, compound eyes, and antennae. There are approximately 91,000 insect species in the United States, the most abundant orders being Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), and Hymenoptera (includes ants, bees, wasps, and sawflies).1

The reported incidence of insect bites and stings varies widely because most people experience mild symptoms and therefore do not seek medical care. Best statistics are for Hymenoptera stings, which are more likely to cause a severe reaction. In Europe, 56% to 94% of the general population has reported being bitten or stung by one of the Hymenoptera species.2 In many areas of Australia, the incidence of jack jumper ant stings is only 2% to 3%3; in the United States, 55% of people report being stung by nonnative fire ants within 3 weeks of moving into an endemic area.4

Arachnids are some of the earliest terrestrial organisms, of the class Arachnida, which includes scorpions, ticks, spiders, mites, and daddy longlegs (harvestmen).5 Arachnids are wingless and characterized by segmented bodies, jointed appendages, and exoskeletons.6,7 In most, the body is separated into 2 segments (the cephalothorax and abdomen), except for mites, ticks, and daddy longlegs, in which the entire body comprises a single segment.5

Arthropod bites are common in the United States; almost one-half are caused by spiders.7 Brown recluse (Loxosceles spp) and black widow (Latrodectus spp) spider bites are the most concerning: Although usually mild, these bites can be life-threatening but are rarely fatal. In 2013, almost 3500 bites by black widow and brown recluse spiders were reported.8

Risk factors

Risk factors for insect, arachnid, and other arthropod bites and stings are primarily environmental. People who live or work in proximity of biting or stinging insects (eg, gardeners and beekeepers) are more likely to be affected; so are those who work with animals or live next to standing water or grassy or wooded locales.

Continue to: There are also risk factors...

There are also risk factors for a systemic sting reaction:

- A sting reaction < 2 months earlier increases the risk of a subsequent systemic sting reaction by ≥ 50%.9

- Among beekeepers, paradoxically, the risk of a systemic reaction is higher in those stung < 15 times a year than in those stung > 200 times.10

- Patients with an elevated baseline serum level of tryptase (reference range, < 11.4 ng/mL), which is part of the allergenic response, or with biopsy-proven systemic mastocytosis are at increased risk of a systemic sting reaction.11

Presentation: Signs and symptomsvary with severity

Insect bites and stings usually cause transient local inflammation and, occasionally, a toxic reaction. Allergic hypersensitivity can result in a large local reaction or a generalized systemic reaction12:

- A small local reaction is transient and mild, develops directly at the site of the sting, and can last several days.13

- A large (or significant) local reaction, defined as swelling > 10 cm in diameter (FIGURE 1) and lasting > 24 hours, occurs in 2% to 26% of people who have been bitten or stung.14 This is an immunoglobulin (Ig) E–mediated late-phase reaction that can be accompanied by fatigue and nausea.12,13,15 For a patient with a large local reaction, the risk of a concomitant systemic reaction is 4% to 10%, typically beginning within 30 minutes after envenomation or, possibly, delayed for several hours or marked by a biphasic interval.16

- Characteristics of a systemic reaction are urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, large-airway edema, hypotension, and other clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis.17 In the United States, a systemic sting reaction is reported to occur in approximately 3% of bite and sting victims. Mortality among the general population from a systemic bite or sting reaction is 0.16 for every 100,000 people,2 and at least 40 to 100 die every year in the United States from anaphylaxis resulting from an insect bite or sting.18

- The most severe anaphylactic reactions involve the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, commonly including hypotension and symptoms of upper- or lower-airway obstruction. Laryngeal edema and circulatory failure are the most common mechanisms of anaphylactic death.19

Bees and wasps

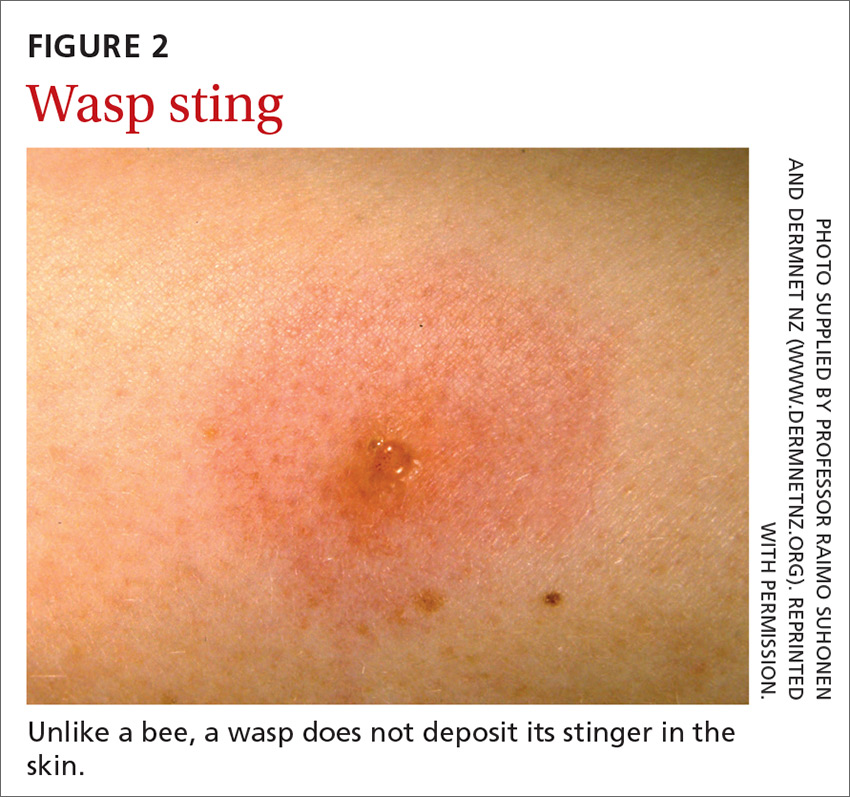

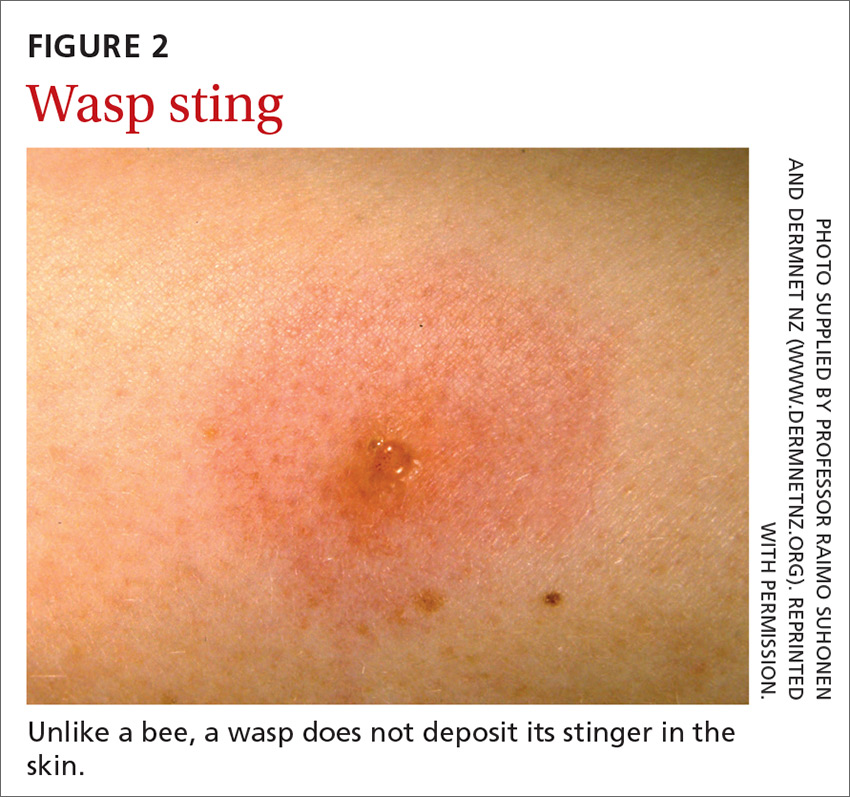

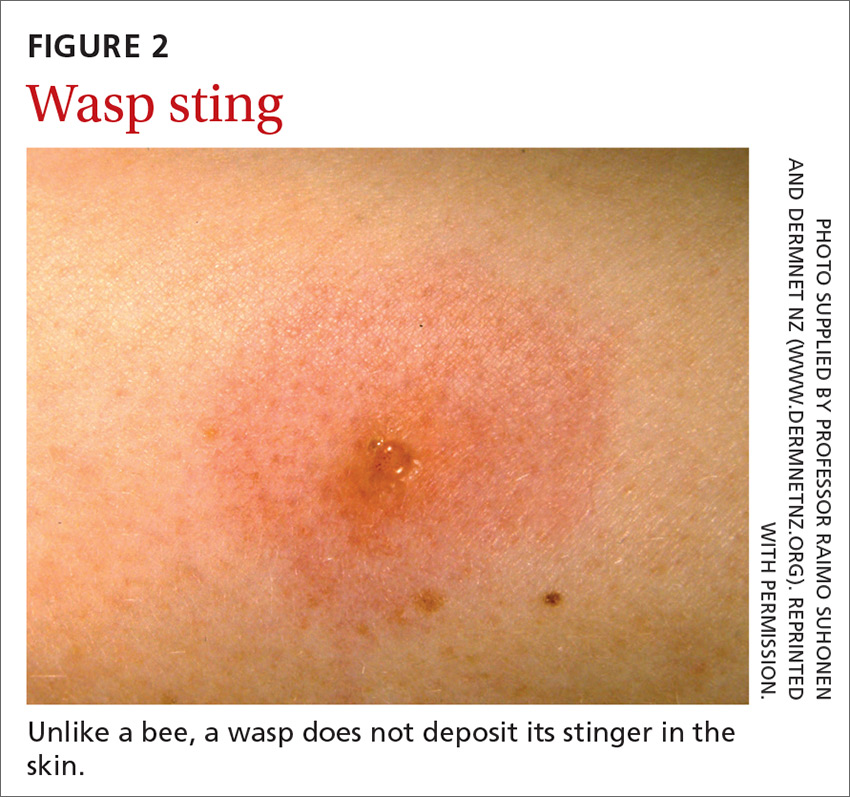

Hymenoptera stinging insects include the family Apidae (honey bee, bumblebee, and sweat bee) and Vespidae (yellow jacket, yellow- and white-faced hornets, and paper wasp). A worker honey bee can sting only once, leaving its barbed stinger in the skin; a wasp, hornet, and yellow jacket can sting multiple times (FIGURE 2).2

Continue to: Bee and wasp sting...

Bee and wasp sting allergies are the most common insect venom allergic reactions. A bee sting is more likely to lead to a severe allergic reaction than a wasp sting. Allergic reactions to hornet and bumblebee stings are less common but can occur in patients already sensitized to wasp and honey bee stings.20,21

Management. Remove honey bee stingers by scraping the skin with a fingernail or credit card. Ideally, the stinger should be removed in the first 30 seconds, before the venom sac empties. Otherwise, intense local inflammation, with possible lymphangitic streaking, can result.22

For guidance on localized symptomatic care of bee and wasp stings and bites and stings from other sources discussed in this article, see “Providing relief and advanced care” on page E6.

Centipedes and spiders

Centipedes are arthropods of the class Chilopoda, subphylum Myriapoda, that are characterized by repeating linear (metameric) segments, each containing 1 pair of legs.23 Centipedes have a pair of poison claws behind the head that are used to paralyze prey—usually, small insects.23,24 The bite of a larger centipede can cause a painful reaction that generally subsides after a few hours but can last several days. Centipede bites are usually nonfatal to humans.23

Spiders belong to the class Arachnida, order Araneae. They have 8 legs with chelicerae (mouthpiece, or “jaws”) that inject venom into prey.25 Most spiders found in the United States cannot bite through human skin.26,27 Common exceptions are black widow and brown recluse spiders, which each produce a distinct toxic venom that can cause significant morbidity in humans through a bite, although bites are rarely fatal.26,27

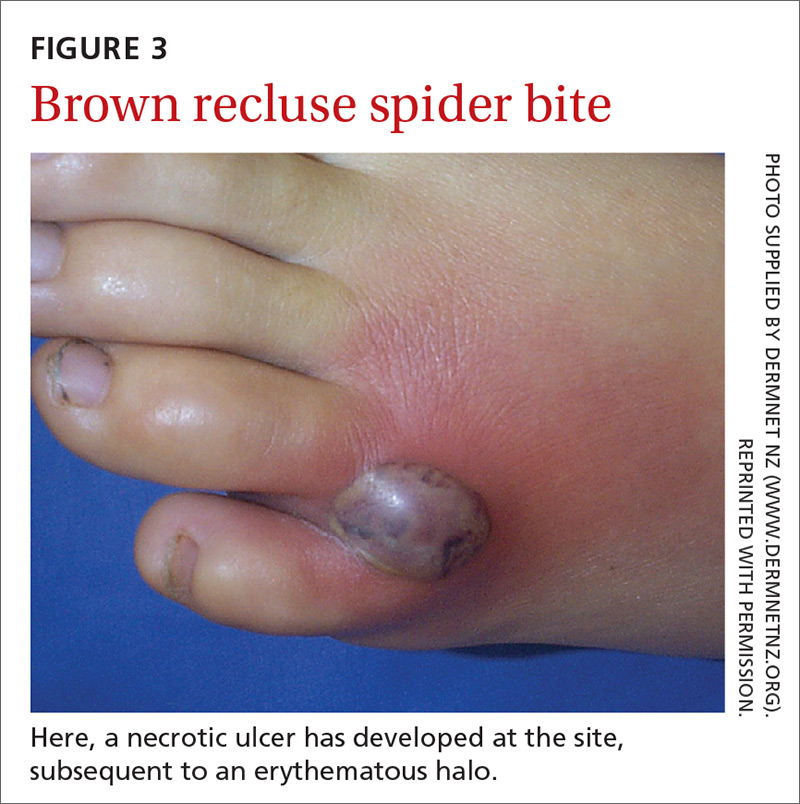

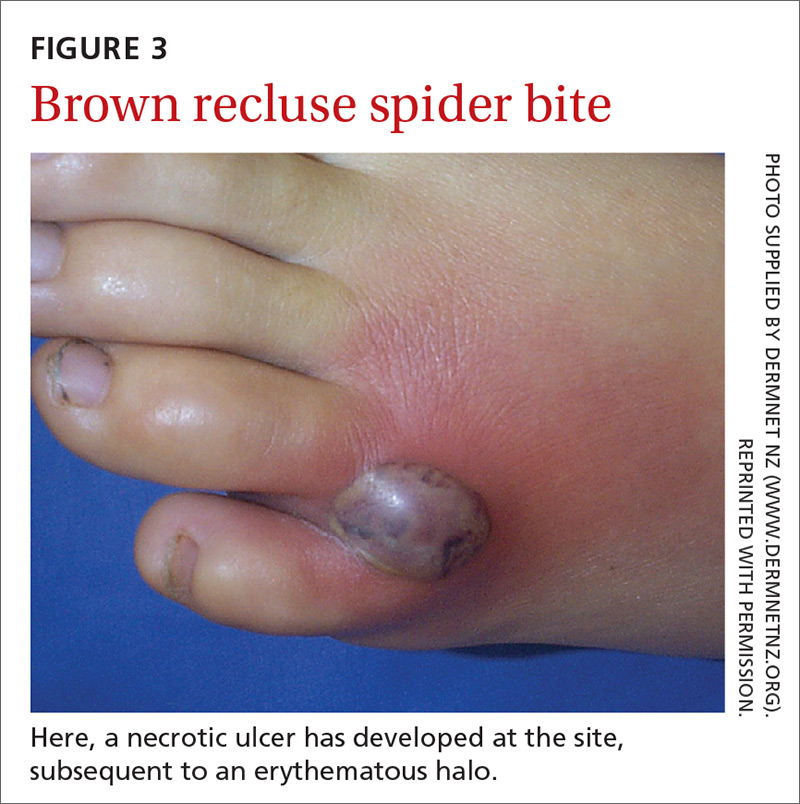

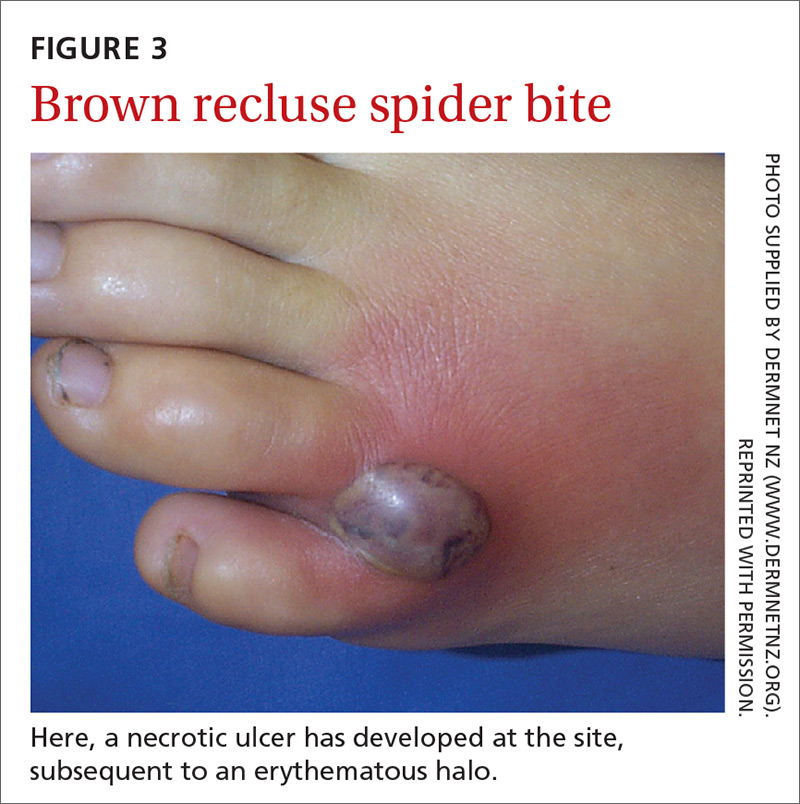

The brown recluse spider is described as having a violin-shaped marking on the abdomen; the body is yellowish, tan, or dark brown. A bite can produce tiny fang marks and cause dull pain at the site of the bite that spreads quickly; myalgia; and pain in the stomach, back, chest, and legs.28,29 The bite takes approximately 7 days to resolve. In a minority of cases, a tender erythematous halo develops, followed by a severe necrotic ulcer, or loxoscelism (FIGURE 3; 40% of cases) or scarring (13%), or both.29,30

Continue to: In contrast...

In contrast, the body of a black widow spider is black; females exhibit a distinctive red or yellow hourglass marking on their ventral aspect.28,31 The pinprick sensation of a bite leads to symptoms that can include erythema, swelling, pain, stiffness, chills, fever, nausea, and stomach pain.30,32

Management. Again, see “Providing relief and advanced care” on page E6. Consider providing antivenin treatment for moderate or severe bites of brown recluse and black widow spiders.

Fleas

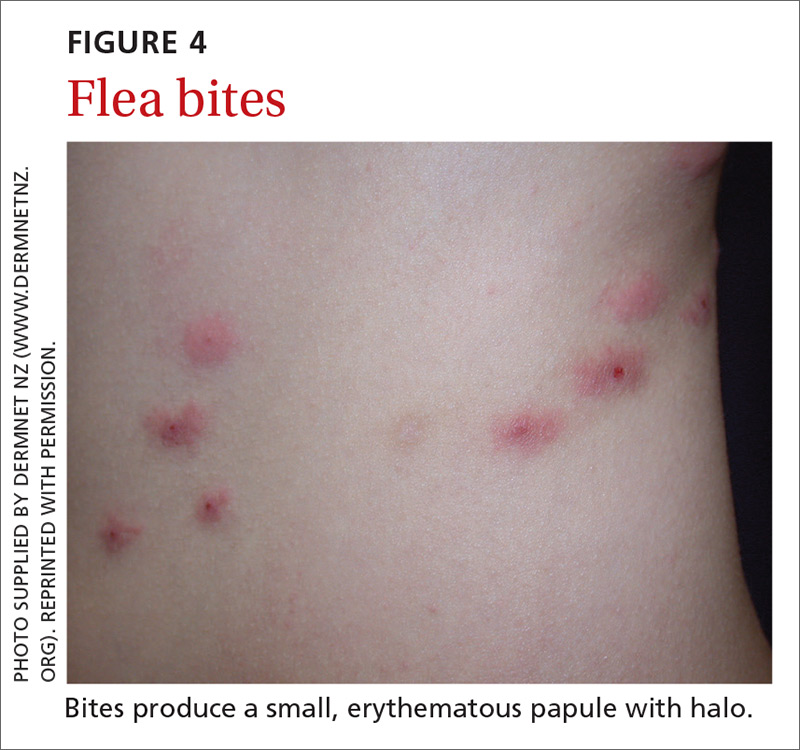

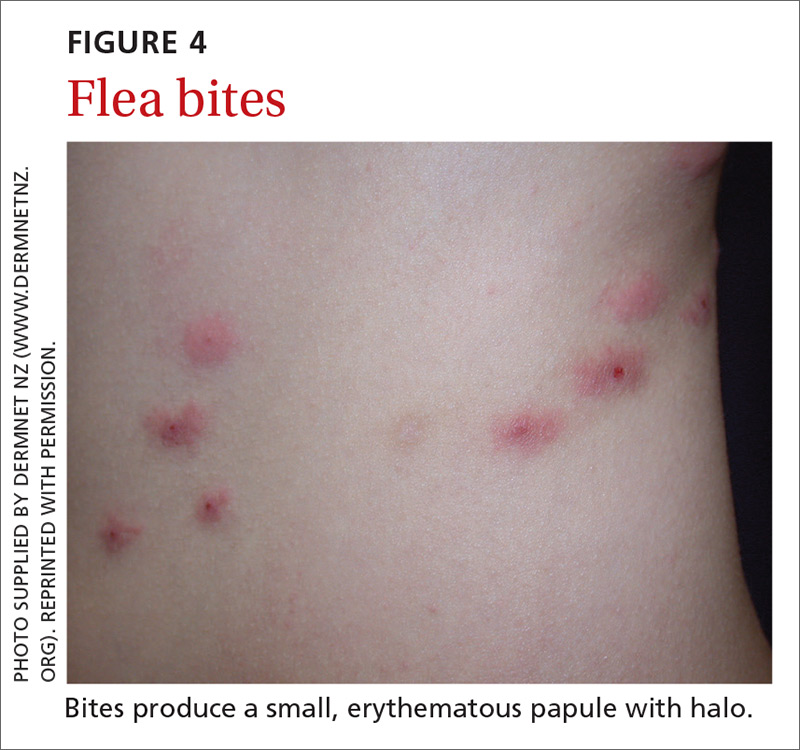

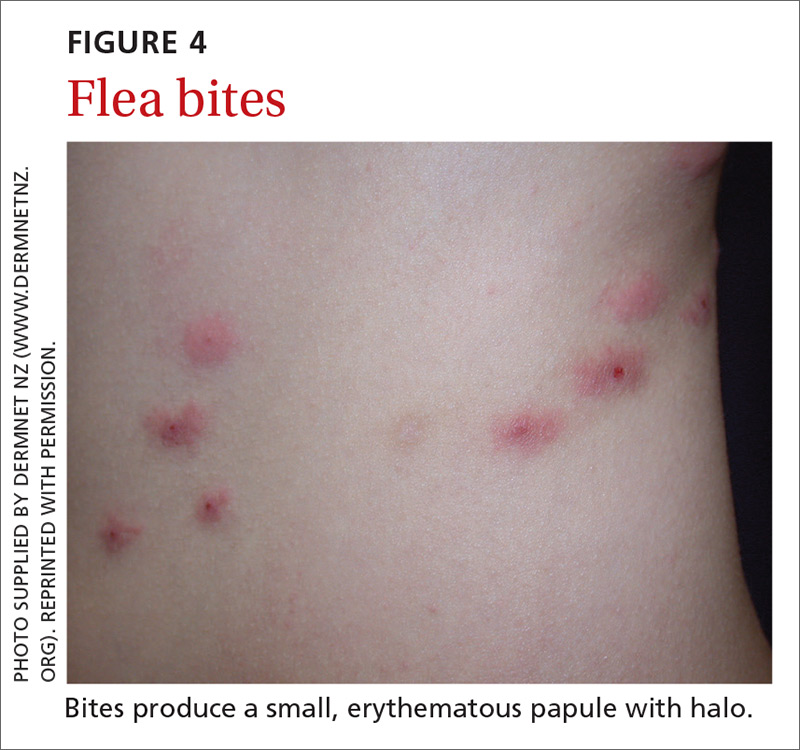

Fleas are members of the order Siphonaptera. They are small (1.5-3.2 mm long), reddish brown, wingless, blood-sucking insects with long legs that allow them to jump far (12 or 13 inches) and high (6 or 7 inches).33 Domesticated cats and dogs are the source of most flea infestations, resulting in an increased risk of exposure for humans.34,35 Flea bites, which generally occur on lower extremities, develop into a small, erythematous papule with a halo (FIGURE 4) and associated mild edema, and cause intense pruritus 30 minutes after the bite.35-37

Fleas are a vector for severe microbial infections, including bartonellosis, bubonic plague, cat-flea typhus, murine typhus, cat-scratch disease, rickettsial disease, and tularemia. Tungiasis is an inflammatory burrowing flea infestation—not a secondary infection for which the flea is a vector.34,35

Preventive management. Repellents, including products that contain DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide), picaridin (2-[2-hydroxyethyl]-1-piperidinecarboxylic acid 1-methylpropyl ester), and PMD (p-menthane-3,8-diol, a chemical constituent of Eucalyptus citriodora oil) can be used to prevent flea bites in humans.33,38 Studies show that the scent of other botanic oils, including lavender, cedarwood, and peppermint, can also help prevent infestation by fleas; however, these compounds are not as effective as traditional insect repellents.33,38

Flea control is difficult, requiring a multimodal approach to treating the infested animal and its environment.39 Treatment of the infested domestic animal is the primary method of preventing human bites. Nonpesticidal control involves frequent cleaning of carpeting, furniture, animal bedding, and kennels. Insecticides can be applied throughout the house to combat severe infestation.33,38

Continue to: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention...

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide a general introduction to getting rid of fleas for pet owners.40 For specific guidance on flea-eradication strategies and specific flea-control products, advise patients to seek the advice of their veterinarian.

Flies and biting midges

Flies are 2-winged insects belonging to the order Diptera. Several fly species can bite, causing a local inflammatory reaction; these include black flies, deer flies, horse flies, and sand flies. Signs and symptoms of a fly bite include pain, pruritus, erythema, and mild swelling (FIGURE 5).41,42 Flies can transmit several infections, including bartonellosis, enteric bacterial disease (eg, caused by Campylobacter spp), leishmaniasis, loiasis, onchocerciasis, and trypanosomiasis.43

Biting midges, also called “no-see-ums,” biting gnats, moose flies, and “punkies,”44 are tiny (1-3 mm long) blood-sucking flies.45 Bitten patients often report not having seen the midge because it is so small. The bite typically starts as a small, erythematous papule that develops into a dome-shaped blister and can be extraordinarily pruritic and painful.44 The majority of people who have been bitten develop a hypersensitivity reaction, which usually resolves in a few weeks.

Management. Suppressing adult biting midges with an environmental insecticide is typically insufficient because the insecticide must be sprayed daily to eradicate active midges and generally does not affect larval habitat. Insect repellents and biopesticides, such as oil of lemon eucalyptus, can be effective in reducing the risk of bites.44,45

Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes are flying, blood-sucking insects of the order Diptera and family Culicidae. Anopheles, Culex, and Aedes genera are responsible for most bites of humans.

The bite of a mosquito produces an indurated, limited local reaction characterized by a pruritic wheal (3-29 mm in diameter) with surrounding erythema (FIGURE 6) that peaks in approximately 30 minutes, although patients might have a delayed reaction hours later.46 Immunocompromised patients might experience a more significant local inflammatory reaction that is accompanied by low-grade fever, hives, or swollen lymph nodes.46,47

Mosquitoes are a vector for serious infections, including dengue, Japanese encephalitis, malaria, and yellow fever, and disease caused by Chikungunya, West Nile, and Zika viruses.

Continue to: Management

Management. Advise patients to reduce their risk by using insect repellent, sleeping under mosquito netting, and wearing a long-sleeve shirt and long pants when traveling to endemic areas or when a local outbreak occurs.48

Ticks

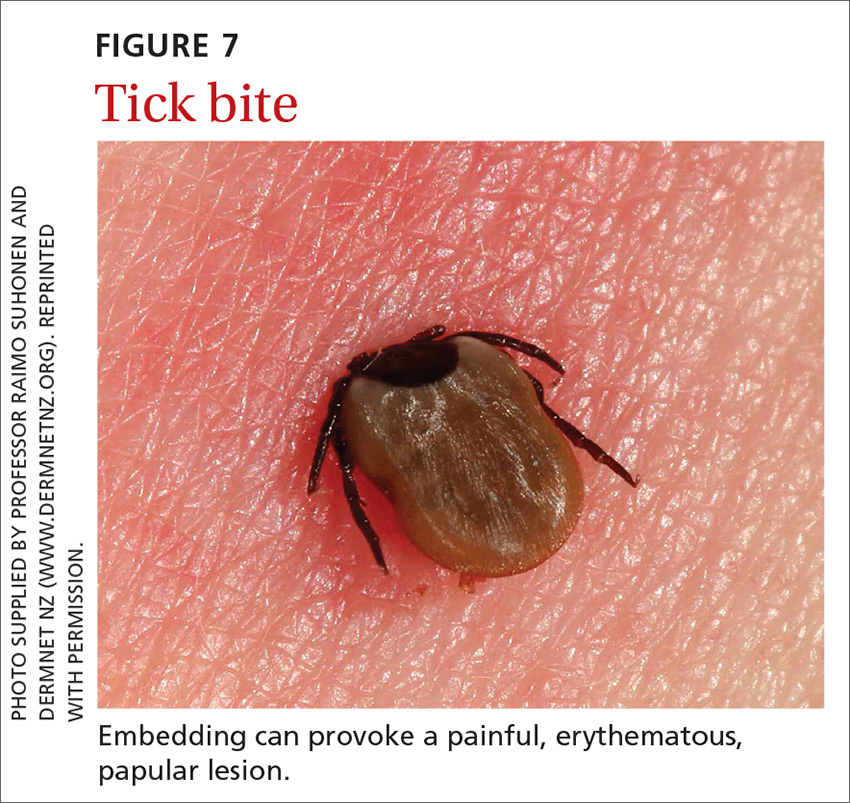

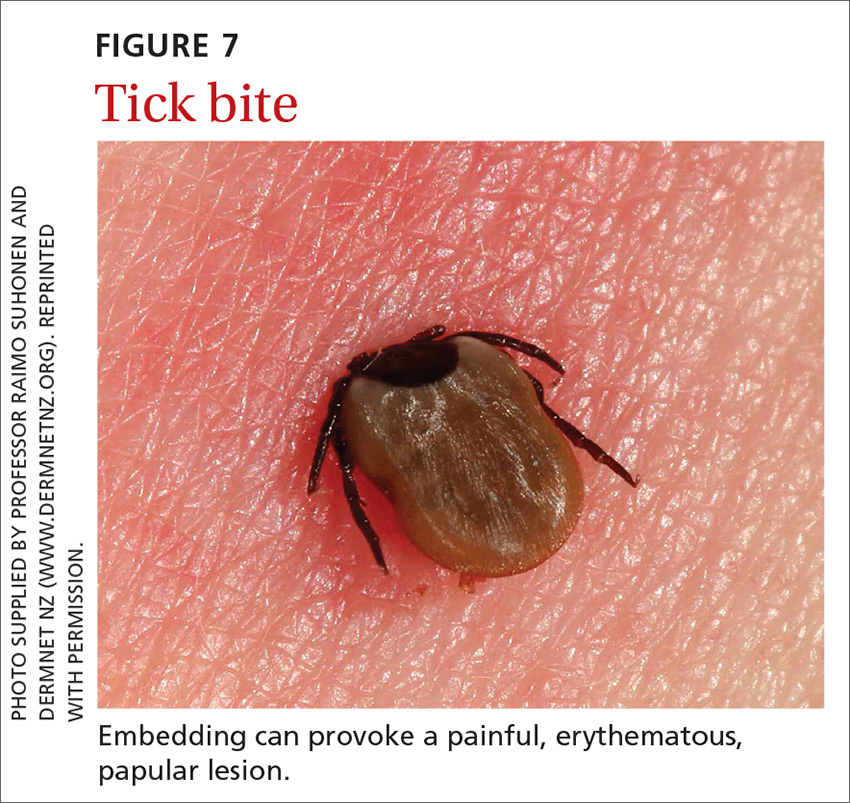

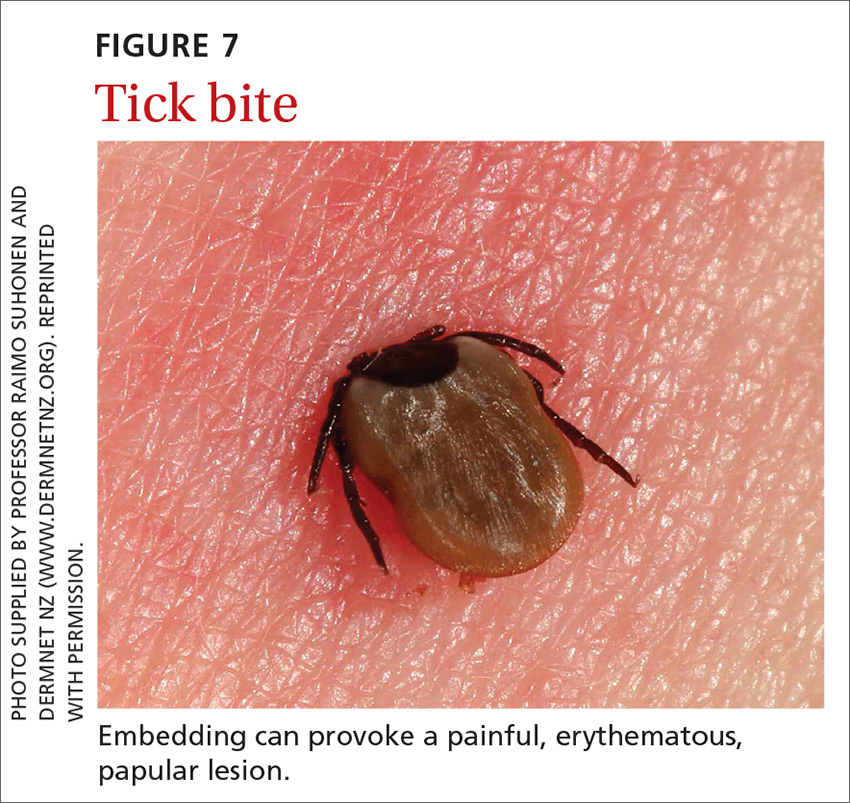

Ticks belong to the order Parasitiformes and families Ixodidae and Argasidae. Hard ticks are found in brushy fields and tall grasses and can bite and feed on humans for days. Soft ticks are generally found around animal nests.29 Tick bites can cause a local reaction that includes painful, erythematous, inflammatory papular lesions (FIGURE 7).49

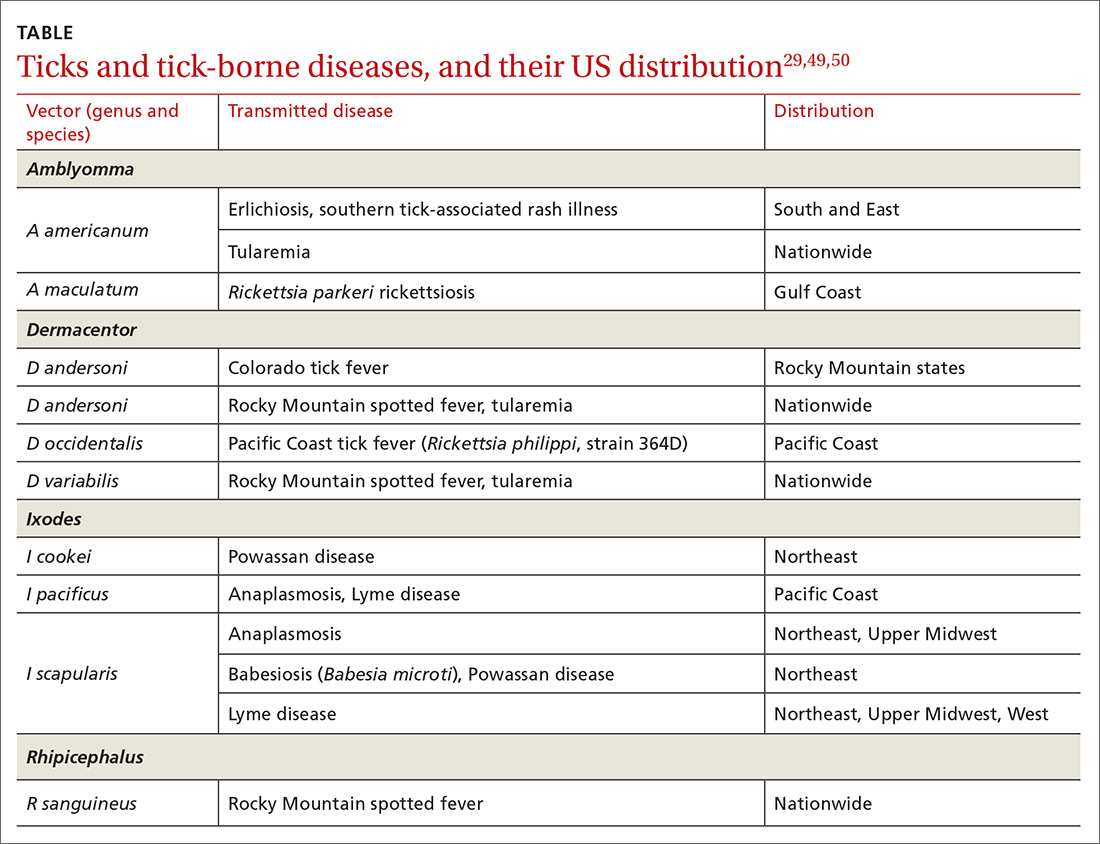

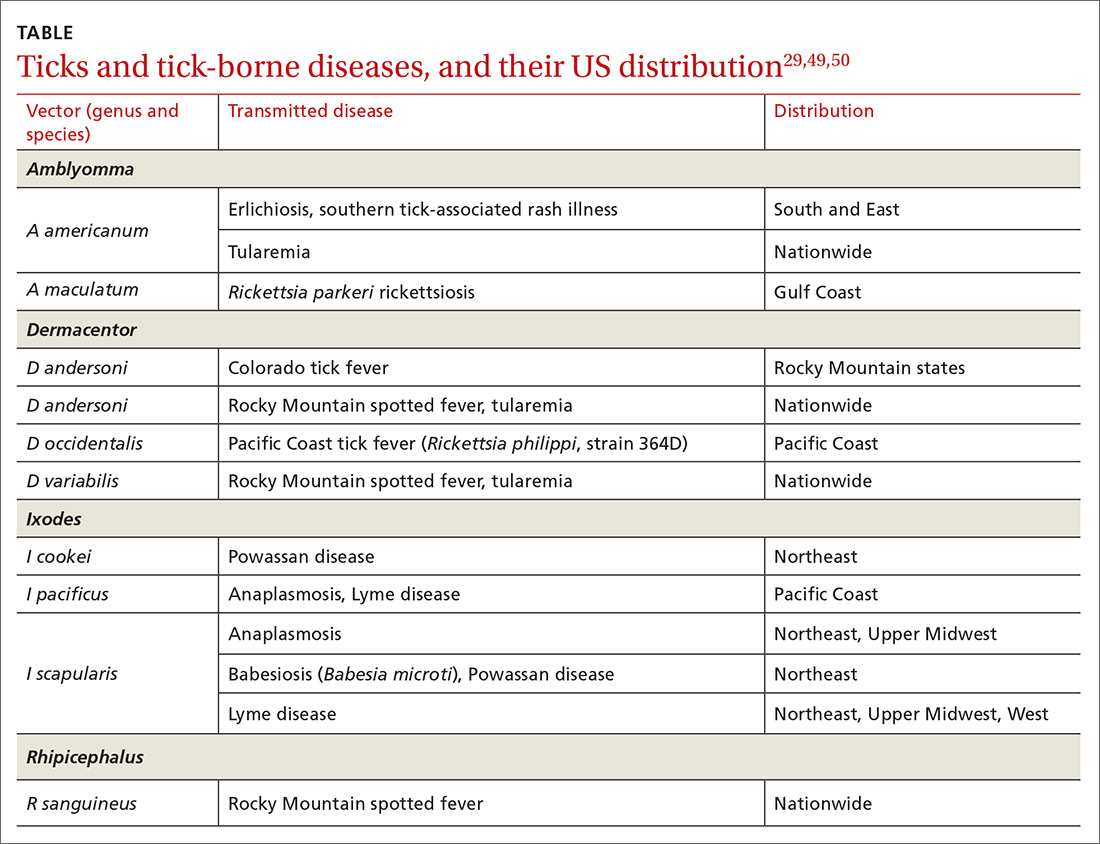

Ticks can transmit several infectious diseases. Depending on the microbial pathogen and the genus and species of tick, it takes 2 to 96 hours for the tick to attach to skin and transmit the pathogen to the human host. The TABLE29,49,50 provides an overview of tick species in the United States, diseases that they can transmit, and the geographic distribution of those diseases.

Management. Ticks should be removed with fine-tipped tweezers. Grasp the body of the tick close to the skin and pull upward while applying steady, even pressure. After removing the tick, clean the bite and the surrounding area with alcohol or with soap and water. Dispose of a live tick by flushing it down the toilet; or, kill it in alcohol and either seal it in a bag with tape or place it in a container.50

Diagnosis and the utilityof special testing

The diagnosis of insect, arachnid, and other arthropod bites and stings depends on the history, including obtaining a record of possible exposure and a travel history; the timing of the bite or sting; and associated signs and symptoms.18,51

Venom skin testing. For Hymenoptera stings, intradermal tests using a venom concentration of 0.001 to 1 μg/mL are positive in 65% to 80% of patients with a history of a systemic insect-sting allergic reaction. A negative venom skin test can occur during the 3-to-6-week refractory period after a sting reaction or many years later, which represents a loss of sensitivity. Positive venom skin tests are used to confirm allergy and identify specific insects to which the patient is allergic.11,12

Continue to: Allergen-specific IgE antibody testing.

Allergen-specific IgE antibody testing. These serum assays—typically, radioallergosorbent testing (RAST)—are less sensitive than venom skin tests. RAST is useful when venom skin testing cannot be performed or when skin testing is negative in a patient who has had a severe allergic reaction to an insect bite or sting. Serum IgE-specific antibody testing is preferred over venom skin testing in patients who are at high risk of anaphylaxis.52,53

Providing reliefand advanced care

Symptomatic treatment of mild bites and stings includes washing the affected area with soap and water and applying a cold compress to reduce swelling.54 For painful lesions, an oral analgesic can be prescribed.

For mild or moderate pruritus, a low- to midpotency topical corticosteroid (eg, hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% bid), topical calamine, or pramoxine can be applied,or a nonsedating oral antihistamine, such as loratadine (10 mg/d) or cetirizine (10 mg/d), can be used.14,55 For severe itching, a sedating antihistamine, such as hydroxyzine (10-25 mg every 4 to 6 hours prn), might help relieve symptoms; H1- and H2-receptor antagonists can be used concomitantly.54,55

Significant local symptoms. Large local reactions are treated with a midpotency topical corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% bid) plus an oral antihistamine to relieve pruritus and reduce allergic inflammation. For a more severe reaction, an oral corticosteroid (prednisone 1 mg/kg; maximum dosage, 50 mg/d) can be given for 5 to 7 days.54-56

Management of a necrotic ulcer secondary to a brown recluse spider bite is symptomatic and supportive. The size of these wounds can increase for as long as 10 days after the bite; resolution can require months of wound care, possibly with debridement. Rarely, skin grafting is required.27,28,31

VIT. Some studies show that VIT can improve quality of life in patients with prolonged, frequent, and worsening reactions to insect bites or stings and repeated, unavoidable exposures.55,56 VIT is recommended for patients with systemic hypersensitivity and a positive venom skin test result. It is approximately 95% effective in preventing or reducing severe systemic reactions and reduces the risk of anaphylaxis (see next section) and death.57 The maintenance dosage of VIT is usually 100 μg every 4 to 6 weeks; optimal duration of treatment is 3 to 5 years.58

Continue to: After VIT is complete...

After VIT is complete, counsel patients that a mild systemic reaction is still possible after an insect bite or sting. More prolonged, even lifetime, treatment should be considered for patients who have58,59

- a history of severe, life-threatening allergic reactions to bites and stings

- honey bee sting allergy

- mast-cell disease

- a history of anaphylaxis while receiving VIT.

Absolute contraindications to VIT include a history of serious immune disease, chronic infection, or cancer.58,59

Managing anaphylaxis

This severe allergic reaction can lead to death if untreated. First-line therapy is intramuscular epinephrine, 0.01 mg/kg (maximum single dose, 0.5 mg) given every 5 to 15 minutes.14,60 Epinephrine auto-injectors deliver a fixed dose and are labeled according to weight. Administration of O2 and intravenous fluids is recommended for hemodynamically unstable patients.60,61 Antihistamines and corticosteroids can be used as secondary treatment but should not replace epinephrine.56

After preliminary improvement, patients might decompensate when the epinephrine dose wears off. Furthermore, a biphasic reaction, variously reported in < 5% to as many as 20% of patients,61,62 occurs hours after the initial anaphylactic reaction. Patients should be monitored, therefore, for at least 6 to 8 hours after an anaphylactic reaction, preferably in a facility equipped to treat anaphylaxis.17,56

Before discharge, patients who have had an anaphylactic reaction should be given a prescription for epinephrine and training in the use of an epinephrine auto-injector. Allergen avoidance, along with an emergency plan in the event of a bite or sting, is recommended. Follow-up evaluation with an allergist or immunologist is essential for proper diagnosis and to determine whether the patient is a candidate for VIT.14,17

CORRESPONDENCE

Ecler Ercole Jaqua, MD, DipABLM, FAAFP, 1200 California Street, Suite 240, Redlands, CA 92374; [email protected].

1. Numbers of insects (species and individuals). Smithsonian BugInfo Web site. www.si.edu/spotlight/buginfo/bugnos. Accessed November 25, 2020.

2. Antonicelli L, Bilò MB, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of Hymenoptera allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:341-346.

3. Jack jumper ant allergy. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) Web site. Updated October 19, 2019. www.allergy.org.au/patients/insect-allergy-bites-and-stings/jack-jumper-ant-allergy. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. Kemp SF, deShazo RD, Moffit JE, et al. Expanding habitat of the imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta): a public health concern. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:683-691.

5. Goodnight ML. Arachnid. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. 2012. www.britannica.com/animal/arachnid. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ. Arachnids. In: Despommier DD, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ. Parasitic Diseases. 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag; 1995:268-283.

7. Diaz JH, Leblanc KE. Common spider bites. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:869-873.

8. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:1032-1283.

9. Pucci S, Antonicelli L, Bilò MB, et al. Shortness of interval between two stings as risk factor for developing Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy.1994;49:894-896.

10. Müller UR. Bee venom allergy in beekeepers and their family members. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:343-347.

11. Müller UR. Cardiovascular disease and anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:337-341.

12. Golden DBK. Stinging insect allergy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2541-2546.

13. Golden DBK, Demain T, Freeman T, et al. Stinging insect hypersensitivity: a practice parameter update 2016. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:28-54.

14. Bilò BM, Rueff F, Mosbech H, et al; EAACI Interest Group on Insect Venom Hypersensitivity. Diagnosis of Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2005;60:1339-1349.

15. Reisman RE. Insect stings. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:523-527.

16. Pucci S, D’Alò S, De Pasquale T, et al. Risk of anaphylaxis in patients with large local reactions to hymenoptera stings: a retrospective and prospective study. Clin Mol Allergy. 2015;13:21.

17. Golden DBK. Large local reactions to insect stings. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:331-334.

18. Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Emergency treatment and prevention of insect-sting anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:279-283.

19. Stinging insect allergy. In: Volcheck GW. Clinical Allergy: Diagnosis and Management. Humana Press; 2009:465-479.

20. Järvinen KM, Celestin J. Anaphylaxis avoidance and management: educating patients and their caregivers. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7:95-104.

21. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Insect venom allergies: overview. InformedHealth.org. Updated May 7, 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0096282/. Accessed November 25, 2020.

22. Casale TB, Burks AW. Clinical practice. Hymenoptera-sting hypersensitivity. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1432-1439.

23. Shelley RM. Centipedes and millipedes with emphasis on North American fauna. Kansas School Naturalist. 1999;45:1-16. https://sites.google.com/g.emporia.edu/ksn/ksn-home/vol-45-no-3-centipedes-and-millipedes-with-emphasis-on-n-america-fauna#h.p_JEf3uDlTg0jw. Accessed November 25, 2020.

24. Ogg B. Centipedes and millipedes. Nebraska Extension in Lancaster County Web site. https://lancaster.unl.edu/pest/resources/CentipedeMillipede012.shtml. Accessed November 25, 2020.

25. Cushing PE. Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae). In: Capinera JL, ed. Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer, Dordrecht; 2008:226.

26. Diaz JH, Leblanc KE. Common spider bites. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:869-873.

27. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venomous spiders. www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/spiders/. Accessed November 25, 2020.

28. Starr S. What you need to know to prevent a poisonous spider bite. AAP News. 2013;34:42. www.aappublications.org/content/aapnews/34/9/42.5.full.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

29. Spider bites. Mayo Clinic Web site. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/spider-bites/symptoms-causes/syc-20352371. Accessed November 25, 2020.

30. Barish RA, Arnold T. Spider bites. In: Merck Manual (Professional Version). Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2016. www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/spider-bites. Accessed November 25, 2020.

31. Juckett G. Arthropod bites. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:841-847.

32. Clark RF, Wethern-Kestner S, Vance MV, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment of black widow spider envenomation: a review of 163 cases. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:782-787.

33. Koehler PG, Pereira RM, Diclaro JW II. Fleas. Publication ENY-025. University of Florida IFAS Extension. Revised January 2012. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ig087. Accessed November 25, 2020.

34. Bitam I, Dittmar K, Parola P, et al. Fleas and flea-borne diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e667-e676.

35. Leulmi H, Socolovschi C, Laudisoit A, et al. Detection of Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia typhi, Bartonella species and Yersinia pestis in fleas (Siphonaptera) from Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3152.

36. Naimer SA, Cohen AD, Mumcuoglu KY, et al. Household papular urticaria. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4(11 suppl):911-913.

37. Golomb MR, Golomb HS. What’s eating you? Cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis). Cutis. 2010;85:10-11.

38. Dryden MW. Flea and tick control in the 21st century: challenges and opportunities. Vet Dermatol. 2009;20:435-440.

39. Dryden MW. Fleas in dogs and cats. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation: Merck Manual Veterinary Manual. Updated December 2014. www.merckvetmanual.com/integumentary-system/fleas-and-flea-allergy-dermatitis/fleas-in-dogs-and-cats. Accessed November 25, 2020.

40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Getting rid of fleas. www.cdc.gov/fleas/getting_rid.html. Accessed November 25, 2020.

41. Chattopadhyay P, Goyary D, Dhiman S, et al. Immunomodulating effects and hypersensitivity reactions caused by Northeast Indian black fly salivary gland extract. J Immunotoxicol. 2014;11:126-132.

42. Hrabak TM, Dice JP. Use of immunotherapy in the management of presumed anaphylaxis to the deer fly. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:351-354.

43. Royden A, Wedley A, Merga JY, et al. A role for flies (Diptera) in the transmission of Campylobacter to broilers? Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:3326-3334.

44. Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:13-18.

45. Carpenter S, Groschup MH, Garros C, et al. Culicoides biting midges, arboviruses and public health in Europe. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:102-113.

46. Peng Z, Yang M, Simons FE. Immunologic mechanisms in mosquito allergy: correlation of skin reactions with specific IgE and IgG anti-bodies and lymphocyte proliferation response to mosquito antigens. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1996;77:238-244.

47. Simons FE, Peng Z. Skeeter syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:705-707.

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ health. Clinician resources. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/clinician-information-center. Accessed November 25, 2020.

49. Gauci M, Loh RK, Stone BF, et al. Allergic reactions to the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus: diagnostic evaluation by skin test and radioimmunoassay. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:279-283.

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ticks. Removing a tick. www.cdc.gov/ticks/removing_a_tick.html. Accessed November 25, 2020.

51. Golden DB, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. Insect sting allergy with negative venom skin test responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:897-901.

52. Arzt L, Bokanovic D, Schrautzer C, et al. Immunological differences between insect venom-allergic patients with and without immunotherapy and asymptomatically sensitized subjects. Allergy. 2018;73:1223-1231.

53. Heddle R, Golden DBK. Allergy to insect stings and bites. World Allergy Organization Web site. Updated August 2015. www.worldallergy.org/education-and-programs/education/allergic-disease-resource-center/professionals/allergy-to-insect-stings-and-bites. Accessed November 25, 2020.

54. RuëffF, Przybilla B, Müller U, et al. The sting challenge test in Hymenoptera venom allergy. Position paper of the Subcommittee on Insect Venom Allergy of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 1996;51:216-225.

55. Management of simple insect bites: where’s the evidence? Drug Ther Bull. 2012;50:45-48.

56. Tracy JM. Insect allergy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78:773-783.

57. Golden DBK. Insect sting allergy and venom immunotherapy: a model and a mystery. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:439-447.

58. Winther L, Arnved J, Malling H-J, et al. Side-effects of allergen-specific immunotherapy: a prospective multi-centre study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:254-260.

59. Mellerup MT, Hahn GW, Poulsen LK, et al. Safety of allergen-specific immunotherapy. Relation between dosage regimen, allergen extract, disease and systemic side-effects during induction treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1423-1429.

60. Anaphylaxis and insect stings and bites. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59:e79-e82.

61. Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:373-380.

62. Pflipsen MC, Vega Colon KM. Anaphylaxis: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:355-362. Accessed November 25, 2020.

Insect, arachnid, and other arthropod bites and stings are common patient complaints in a primary care office. A thorough history and physical exam can often isolate the specific offender and guide management. In this article, we outline how to identify, diagnose, and treat common bites and stings from bees and wasps; centipedes and spiders; fleas; flies and biting midges; mosquitoes; and ticks, and discuss how high-risk patients should be triaged and referred for additional testing and treatment, such as venom immunotherapy (VIT).

Insects and arachnids:Background and epidemiology

Insects are arthropods with 3-part exoskeletons: head, thorax, and abdomen. They have 6 jointed legs, compound eyes, and antennae. There are approximately 91,000 insect species in the United States, the most abundant orders being Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), and Hymenoptera (includes ants, bees, wasps, and sawflies).1

The reported incidence of insect bites and stings varies widely because most people experience mild symptoms and therefore do not seek medical care. Best statistics are for Hymenoptera stings, which are more likely to cause a severe reaction. In Europe, 56% to 94% of the general population has reported being bitten or stung by one of the Hymenoptera species.2 In many areas of Australia, the incidence of jack jumper ant stings is only 2% to 3%3; in the United States, 55% of people report being stung by nonnative fire ants within 3 weeks of moving into an endemic area.4

Arachnids are some of the earliest terrestrial organisms, of the class Arachnida, which includes scorpions, ticks, spiders, mites, and daddy longlegs (harvestmen).5 Arachnids are wingless and characterized by segmented bodies, jointed appendages, and exoskeletons.6,7 In most, the body is separated into 2 segments (the cephalothorax and abdomen), except for mites, ticks, and daddy longlegs, in which the entire body comprises a single segment.5

Arthropod bites are common in the United States; almost one-half are caused by spiders.7 Brown recluse (Loxosceles spp) and black widow (Latrodectus spp) spider bites are the most concerning: Although usually mild, these bites can be life-threatening but are rarely fatal. In 2013, almost 3500 bites by black widow and brown recluse spiders were reported.8

Risk factors

Risk factors for insect, arachnid, and other arthropod bites and stings are primarily environmental. People who live or work in proximity of biting or stinging insects (eg, gardeners and beekeepers) are more likely to be affected; so are those who work with animals or live next to standing water or grassy or wooded locales.

Continue to: There are also risk factors...

There are also risk factors for a systemic sting reaction:

- A sting reaction < 2 months earlier increases the risk of a subsequent systemic sting reaction by ≥ 50%.9

- Among beekeepers, paradoxically, the risk of a systemic reaction is higher in those stung < 15 times a year than in those stung > 200 times.10

- Patients with an elevated baseline serum level of tryptase (reference range, < 11.4 ng/mL), which is part of the allergenic response, or with biopsy-proven systemic mastocytosis are at increased risk of a systemic sting reaction.11

Presentation: Signs and symptomsvary with severity

Insect bites and stings usually cause transient local inflammation and, occasionally, a toxic reaction. Allergic hypersensitivity can result in a large local reaction or a generalized systemic reaction12:

- A small local reaction is transient and mild, develops directly at the site of the sting, and can last several days.13

- A large (or significant) local reaction, defined as swelling > 10 cm in diameter (FIGURE 1) and lasting > 24 hours, occurs in 2% to 26% of people who have been bitten or stung.14 This is an immunoglobulin (Ig) E–mediated late-phase reaction that can be accompanied by fatigue and nausea.12,13,15 For a patient with a large local reaction, the risk of a concomitant systemic reaction is 4% to 10%, typically beginning within 30 minutes after envenomation or, possibly, delayed for several hours or marked by a biphasic interval.16

- Characteristics of a systemic reaction are urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, large-airway edema, hypotension, and other clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis.17 In the United States, a systemic sting reaction is reported to occur in approximately 3% of bite and sting victims. Mortality among the general population from a systemic bite or sting reaction is 0.16 for every 100,000 people,2 and at least 40 to 100 die every year in the United States from anaphylaxis resulting from an insect bite or sting.18

- The most severe anaphylactic reactions involve the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, commonly including hypotension and symptoms of upper- or lower-airway obstruction. Laryngeal edema and circulatory failure are the most common mechanisms of anaphylactic death.19

Bees and wasps

Hymenoptera stinging insects include the family Apidae (honey bee, bumblebee, and sweat bee) and Vespidae (yellow jacket, yellow- and white-faced hornets, and paper wasp). A worker honey bee can sting only once, leaving its barbed stinger in the skin; a wasp, hornet, and yellow jacket can sting multiple times (FIGURE 2).2

Continue to: Bee and wasp sting...

Bee and wasp sting allergies are the most common insect venom allergic reactions. A bee sting is more likely to lead to a severe allergic reaction than a wasp sting. Allergic reactions to hornet and bumblebee stings are less common but can occur in patients already sensitized to wasp and honey bee stings.20,21

Management. Remove honey bee stingers by scraping the skin with a fingernail or credit card. Ideally, the stinger should be removed in the first 30 seconds, before the venom sac empties. Otherwise, intense local inflammation, with possible lymphangitic streaking, can result.22

For guidance on localized symptomatic care of bee and wasp stings and bites and stings from other sources discussed in this article, see “Providing relief and advanced care” on page E6.

Centipedes and spiders

Centipedes are arthropods of the class Chilopoda, subphylum Myriapoda, that are characterized by repeating linear (metameric) segments, each containing 1 pair of legs.23 Centipedes have a pair of poison claws behind the head that are used to paralyze prey—usually, small insects.23,24 The bite of a larger centipede can cause a painful reaction that generally subsides after a few hours but can last several days. Centipede bites are usually nonfatal to humans.23

Spiders belong to the class Arachnida, order Araneae. They have 8 legs with chelicerae (mouthpiece, or “jaws”) that inject venom into prey.25 Most spiders found in the United States cannot bite through human skin.26,27 Common exceptions are black widow and brown recluse spiders, which each produce a distinct toxic venom that can cause significant morbidity in humans through a bite, although bites are rarely fatal.26,27

The brown recluse spider is described as having a violin-shaped marking on the abdomen; the body is yellowish, tan, or dark brown. A bite can produce tiny fang marks and cause dull pain at the site of the bite that spreads quickly; myalgia; and pain in the stomach, back, chest, and legs.28,29 The bite takes approximately 7 days to resolve. In a minority of cases, a tender erythematous halo develops, followed by a severe necrotic ulcer, or loxoscelism (FIGURE 3; 40% of cases) or scarring (13%), or both.29,30

Continue to: In contrast...

In contrast, the body of a black widow spider is black; females exhibit a distinctive red or yellow hourglass marking on their ventral aspect.28,31 The pinprick sensation of a bite leads to symptoms that can include erythema, swelling, pain, stiffness, chills, fever, nausea, and stomach pain.30,32

Management. Again, see “Providing relief and advanced care” on page E6. Consider providing antivenin treatment for moderate or severe bites of brown recluse and black widow spiders.

Fleas

Fleas are members of the order Siphonaptera. They are small (1.5-3.2 mm long), reddish brown, wingless, blood-sucking insects with long legs that allow them to jump far (12 or 13 inches) and high (6 or 7 inches).33 Domesticated cats and dogs are the source of most flea infestations, resulting in an increased risk of exposure for humans.34,35 Flea bites, which generally occur on lower extremities, develop into a small, erythematous papule with a halo (FIGURE 4) and associated mild edema, and cause intense pruritus 30 minutes after the bite.35-37

Fleas are a vector for severe microbial infections, including bartonellosis, bubonic plague, cat-flea typhus, murine typhus, cat-scratch disease, rickettsial disease, and tularemia. Tungiasis is an inflammatory burrowing flea infestation—not a secondary infection for which the flea is a vector.34,35

Preventive management. Repellents, including products that contain DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide), picaridin (2-[2-hydroxyethyl]-1-piperidinecarboxylic acid 1-methylpropyl ester), and PMD (p-menthane-3,8-diol, a chemical constituent of Eucalyptus citriodora oil) can be used to prevent flea bites in humans.33,38 Studies show that the scent of other botanic oils, including lavender, cedarwood, and peppermint, can also help prevent infestation by fleas; however, these compounds are not as effective as traditional insect repellents.33,38

Flea control is difficult, requiring a multimodal approach to treating the infested animal and its environment.39 Treatment of the infested domestic animal is the primary method of preventing human bites. Nonpesticidal control involves frequent cleaning of carpeting, furniture, animal bedding, and kennels. Insecticides can be applied throughout the house to combat severe infestation.33,38

Continue to: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention...

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide a general introduction to getting rid of fleas for pet owners.40 For specific guidance on flea-eradication strategies and specific flea-control products, advise patients to seek the advice of their veterinarian.

Flies and biting midges

Flies are 2-winged insects belonging to the order Diptera. Several fly species can bite, causing a local inflammatory reaction; these include black flies, deer flies, horse flies, and sand flies. Signs and symptoms of a fly bite include pain, pruritus, erythema, and mild swelling (FIGURE 5).41,42 Flies can transmit several infections, including bartonellosis, enteric bacterial disease (eg, caused by Campylobacter spp), leishmaniasis, loiasis, onchocerciasis, and trypanosomiasis.43

Biting midges, also called “no-see-ums,” biting gnats, moose flies, and “punkies,”44 are tiny (1-3 mm long) blood-sucking flies.45 Bitten patients often report not having seen the midge because it is so small. The bite typically starts as a small, erythematous papule that develops into a dome-shaped blister and can be extraordinarily pruritic and painful.44 The majority of people who have been bitten develop a hypersensitivity reaction, which usually resolves in a few weeks.

Management. Suppressing adult biting midges with an environmental insecticide is typically insufficient because the insecticide must be sprayed daily to eradicate active midges and generally does not affect larval habitat. Insect repellents and biopesticides, such as oil of lemon eucalyptus, can be effective in reducing the risk of bites.44,45

Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes are flying, blood-sucking insects of the order Diptera and family Culicidae. Anopheles, Culex, and Aedes genera are responsible for most bites of humans.

The bite of a mosquito produces an indurated, limited local reaction characterized by a pruritic wheal (3-29 mm in diameter) with surrounding erythema (FIGURE 6) that peaks in approximately 30 minutes, although patients might have a delayed reaction hours later.46 Immunocompromised patients might experience a more significant local inflammatory reaction that is accompanied by low-grade fever, hives, or swollen lymph nodes.46,47