User login

Study evaluating in utero treatment for hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia seeks enrollees

A multicenter, international phase 2 trial known as EDELIFE is underway to investigate the safety and efficacy of an in utero treatment for developing males with X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED).

This condition is caused by mutations in the gene coding for ectodysplasin A (EDA), a protein that signals the epithelial-mesenchymal transition during embryogenesis. EDA loss or dysfunction precludes binding to its endogenous EDA1 receptor (EDAR), and downstream development of teeth, hair, nails, and skin adnexae, most notably eccrine glands.

The treatment, ER004, is a first-in-class signaling protein EDA replacement molecule now under investigation by the EspeRare Foundation, with support from the Pierre Fabre Foundation. The pioneering clinical trial is evaluating the delivery of ER004 protein replacement in utero to affected fetuses, allowing antenatal binding to the EDAR. According to the EDELIFE web site, when ER004 is administered to XLHED-affected males in utero, it “should act as a replacement for the missing EDA and trigger the process that leads to the normal development of a baby’s skin, teeth, hair, and sweat glands, leading to better formation of these structures.”

The protein is delivered into the amniotic fluid via a needle and syringe under ultrasound guidance. In a report on this treatment used in a pair of affected twins and a third XLHED-affected male published in 2018, the authors reported that the three babies were able to sweat normally after birth, “and XLHED-related illness had not developed by 14-22 months of age.”

The goal of the prospective, open-label, genotype match–controlled EDELIFE trial is to confirm the efficacy and safety results for ER004 in a larger group of boys, and to determine if it can lead to robust, and long-lasting improvement in XLHED-associated defects.

In the United States, the first pregnant woman to join the study received the treatment in February 2023 at Washington University in St. Louis. Other clinical sites are located in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Led by principal investigator Holm Schneider, MD, of the University Erlanger-Nurnberg (Germany), researchers are seeking to enroll mothers aged 18 years and older who are genetically confirmed carriers of the XLHED mutation and pregnant with a boy or considering pregnancy. The control group will include XLHED-affected males, 6 months to 60 years old, who are blood relatives of the pregnant woman participating in the study.

“This is an unprecedented approach to preventing a significant morbidity affecting boys with XLHED, and a potential model for in utero correction of genetic defects involving embryogenesis,” Elaine Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, said in an interview. Dr. Siegfried, who has served on the scientific advisory board of the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias since 1997, added that many years of effort “has finally yielded sufficient funding and identified an international network of experts to support this ambitious trial. We are now seeking participation of the most important collaborators: mothers willing to help establish safety and efficacy of this approach.”

Mary Fete, MSN, RN, executive director of the NFED, said that the EDELIFE clinical trial “provides enormous hope for our families affected by XLHED. It’s extraordinary to think that the baby boys affected by XLHED who have received ER004 are sweating normally and have other improved symptoms. The NFED is proud to have begun and fostered the research for 30-plus years that developed ER004.”

Dr. Siegfried is a member of the independent data monitoring committee for the EDELIFE trial.

Clinicians treating affected families or potentially eligible subjects are encouraged to contact the trial investigators at this link.

A multicenter, international phase 2 trial known as EDELIFE is underway to investigate the safety and efficacy of an in utero treatment for developing males with X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED).

This condition is caused by mutations in the gene coding for ectodysplasin A (EDA), a protein that signals the epithelial-mesenchymal transition during embryogenesis. EDA loss or dysfunction precludes binding to its endogenous EDA1 receptor (EDAR), and downstream development of teeth, hair, nails, and skin adnexae, most notably eccrine glands.

The treatment, ER004, is a first-in-class signaling protein EDA replacement molecule now under investigation by the EspeRare Foundation, with support from the Pierre Fabre Foundation. The pioneering clinical trial is evaluating the delivery of ER004 protein replacement in utero to affected fetuses, allowing antenatal binding to the EDAR. According to the EDELIFE web site, when ER004 is administered to XLHED-affected males in utero, it “should act as a replacement for the missing EDA and trigger the process that leads to the normal development of a baby’s skin, teeth, hair, and sweat glands, leading to better formation of these structures.”

The protein is delivered into the amniotic fluid via a needle and syringe under ultrasound guidance. In a report on this treatment used in a pair of affected twins and a third XLHED-affected male published in 2018, the authors reported that the three babies were able to sweat normally after birth, “and XLHED-related illness had not developed by 14-22 months of age.”

The goal of the prospective, open-label, genotype match–controlled EDELIFE trial is to confirm the efficacy and safety results for ER004 in a larger group of boys, and to determine if it can lead to robust, and long-lasting improvement in XLHED-associated defects.

In the United States, the first pregnant woman to join the study received the treatment in February 2023 at Washington University in St. Louis. Other clinical sites are located in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Led by principal investigator Holm Schneider, MD, of the University Erlanger-Nurnberg (Germany), researchers are seeking to enroll mothers aged 18 years and older who are genetically confirmed carriers of the XLHED mutation and pregnant with a boy or considering pregnancy. The control group will include XLHED-affected males, 6 months to 60 years old, who are blood relatives of the pregnant woman participating in the study.

“This is an unprecedented approach to preventing a significant morbidity affecting boys with XLHED, and a potential model for in utero correction of genetic defects involving embryogenesis,” Elaine Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, said in an interview. Dr. Siegfried, who has served on the scientific advisory board of the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias since 1997, added that many years of effort “has finally yielded sufficient funding and identified an international network of experts to support this ambitious trial. We are now seeking participation of the most important collaborators: mothers willing to help establish safety and efficacy of this approach.”

Mary Fete, MSN, RN, executive director of the NFED, said that the EDELIFE clinical trial “provides enormous hope for our families affected by XLHED. It’s extraordinary to think that the baby boys affected by XLHED who have received ER004 are sweating normally and have other improved symptoms. The NFED is proud to have begun and fostered the research for 30-plus years that developed ER004.”

Dr. Siegfried is a member of the independent data monitoring committee for the EDELIFE trial.

Clinicians treating affected families or potentially eligible subjects are encouraged to contact the trial investigators at this link.

A multicenter, international phase 2 trial known as EDELIFE is underway to investigate the safety and efficacy of an in utero treatment for developing males with X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED).

This condition is caused by mutations in the gene coding for ectodysplasin A (EDA), a protein that signals the epithelial-mesenchymal transition during embryogenesis. EDA loss or dysfunction precludes binding to its endogenous EDA1 receptor (EDAR), and downstream development of teeth, hair, nails, and skin adnexae, most notably eccrine glands.

The treatment, ER004, is a first-in-class signaling protein EDA replacement molecule now under investigation by the EspeRare Foundation, with support from the Pierre Fabre Foundation. The pioneering clinical trial is evaluating the delivery of ER004 protein replacement in utero to affected fetuses, allowing antenatal binding to the EDAR. According to the EDELIFE web site, when ER004 is administered to XLHED-affected males in utero, it “should act as a replacement for the missing EDA and trigger the process that leads to the normal development of a baby’s skin, teeth, hair, and sweat glands, leading to better formation of these structures.”

The protein is delivered into the amniotic fluid via a needle and syringe under ultrasound guidance. In a report on this treatment used in a pair of affected twins and a third XLHED-affected male published in 2018, the authors reported that the three babies were able to sweat normally after birth, “and XLHED-related illness had not developed by 14-22 months of age.”

The goal of the prospective, open-label, genotype match–controlled EDELIFE trial is to confirm the efficacy and safety results for ER004 in a larger group of boys, and to determine if it can lead to robust, and long-lasting improvement in XLHED-associated defects.

In the United States, the first pregnant woman to join the study received the treatment in February 2023 at Washington University in St. Louis. Other clinical sites are located in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Led by principal investigator Holm Schneider, MD, of the University Erlanger-Nurnberg (Germany), researchers are seeking to enroll mothers aged 18 years and older who are genetically confirmed carriers of the XLHED mutation and pregnant with a boy or considering pregnancy. The control group will include XLHED-affected males, 6 months to 60 years old, who are blood relatives of the pregnant woman participating in the study.

“This is an unprecedented approach to preventing a significant morbidity affecting boys with XLHED, and a potential model for in utero correction of genetic defects involving embryogenesis,” Elaine Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Saint Louis University, said in an interview. Dr. Siegfried, who has served on the scientific advisory board of the National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias since 1997, added that many years of effort “has finally yielded sufficient funding and identified an international network of experts to support this ambitious trial. We are now seeking participation of the most important collaborators: mothers willing to help establish safety and efficacy of this approach.”

Mary Fete, MSN, RN, executive director of the NFED, said that the EDELIFE clinical trial “provides enormous hope for our families affected by XLHED. It’s extraordinary to think that the baby boys affected by XLHED who have received ER004 are sweating normally and have other improved symptoms. The NFED is proud to have begun and fostered the research for 30-plus years that developed ER004.”

Dr. Siegfried is a member of the independent data monitoring committee for the EDELIFE trial.

Clinicians treating affected families or potentially eligible subjects are encouraged to contact the trial investigators at this link.

Innovations in pediatric chronic pain management

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

At the new Walnut Creek Clinic in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay area, kids get a “Comfort Promise.”

The clinic extends the work of the Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, Palliative & Integrative Medicine beyond the locations in University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland.

At Walnut Creek, clinical acupuncturists, massage therapists, and specialists in hypnosis complement advanced medical care with integrative techniques.

The “Comfort Promise” program, which is being rolled out at that clinic and other UCSF pediatric clinics through the end of 2024, is the clinicians’ pledge to do everything in their power to make tests, infusions, and vaccinations “practically pain free.”

Needle sticks, for example, can be a common source of pain and anxiety for kids. Techniques to minimize pain vary by age. Among the ways the clinicians minimize needle pain for a child 6- to 12-years-old are:

- Giving the child control options to pick which arm; and watch the injection, pause it, or stop it with a communication sign.

- Introducing memory shaping by asking the child about the experience afterward and presenting it in a positive way by praising the acts of sitting still, breathing deeply, or being brave.

- Using distractors such as asking the child to hold a favorite item from home, storytelling, coloring, singing, or using breathing exercises.

Stefan Friedrichsdorf, MD, chief of the UCSF division of pediatric pain, palliative & integrative medicine, said in a statement: “For kids with chronic pain, complex pain medications can cause more harm than benefit. Our goal is to combine exercise and physical therapy with integrative medicine and skills-based psychotherapy to help them become pain free in their everyday life.”

Bundling appointments for early impact

At Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, the chronic pain treatment program bundles visits with experts in several disciplines, include social workers, psychologists, and physical therapists, in addition to the medical team, so that patients can complete a first round of visits with multiple specialists in a short period, as opposed to several months.

Natalie Weatherred, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology and the pain clinic coordinator, said in an interview that the up-front visits involve between four and eight follow-up sessions in a short period with everybody in the multidisciplinary team “to really help jump-start their pain treatment.”

She pointed out that many families come from distant parts of the state or beyond so the bundled appointments are also important for easing burden on families.

Sarah Duggan, APRN-NP, CPNP-PC, also a pediatric nurse practitioner in anesthesiology at Lurie’s, pointed out that patients at their clinic often have other chronic conditions as well, such as such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome so the care integration is particularly important.

“We can get them the appropriate care that they need and the resources they need, much sooner than we would have been able to do 5 or 10 years ago,” Ms. Duggan said.

Virtual reality distraction instead of sedation

Henry Huang, MD, anesthesiologist and pain physician at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, said a special team there collaborates with the Chariot Program at Stanford (Calif.) University and incorporates virtual reality to distract children from pain and anxiety and harness their imaginations during induction for anesthesia, intravenous placement, and vaccinations.

“At our institution we’ve been recruiting patients to do a proof of concept to do virtual reality distraction for pain procedures, such as nerve blocks or steroid injections,” Dr. Huang said.

Traditionally, kids would have received oral or intravenous sedation to help them cope with the fear and pain.

“We’ve been successful in several cases without relying on any sedation,” he said. “The next target is to expand that to the chronic pain population.”

The distraction techniques are promising for a wide range of ages, he said, and the programming is tailored to the child’s ability to interact with the technology.

He said he is also part of a group promoting use of ultrasound instead of x-rays to guide injections to the spine and chest to reduce children’s exposure to radiation. His group is helping teach these methods to other clinicians nationally.

Dr. Huang said the most important development in chronic pediatric pain has been the growth of rehab centers that include the medical team, and practitioners from psychology as well as occupational and physical therapy.

“More and more hospitals are recognizing the importance of these pain rehab centers,” he said.

The problem, Dr. Huang said, is that these programs have always been resource intensive and involve highly specialized clinicians. The cost and the limited number of specialists make it difficult for widespread rollout.

“That’s always been the challenge from the pediatric pain world,” he said.

Recognizing the complexity of kids’ chronic pain

Angela Garcia, MD, a consulting physician for pediatric rehabilitation medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh said

Techniques such as biofeedback and acupuncture are becoming more mainstream in pediatric chronic care, she said.

At the UPMC clinic, children and their families talk with a care team about their values and what they want to accomplish in managing the child’s pain. They ask what the pain is preventing the child from doing.

“Their goals really are our goals,” she said.

She said she also refers almost all patients to one of the center’s pain psychologists.

“Pain is biopsychosocial,” she said. “We want to make sure we’re addressing how to cope with pain.”

Dr. Garcia said she hopes nutritional therapy is one of the next approaches the clinic will incorporate, particularly surrounding how dietary changes can reduce inflammation “and heal the body from the inside out.”

She said the hospital is also looking at developing an inpatient pain program for kids whose functioning has changed so drastically that they need more intensive therapies.

Whatever the treatment approach, she said, addressing the pain early is critical.

“There is an increased risk of a child with chronic pain becoming an adult with chronic pain,” Dr. Garcia pointed out, “and that can lead to a decrease in the ability to participate in society.”

Ms. Weatherred, Ms. Duggan, Dr. Huang, and Dr. Garcia reported no relevant financial relationships.

Perinatal psychiatry: 5 key principles

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

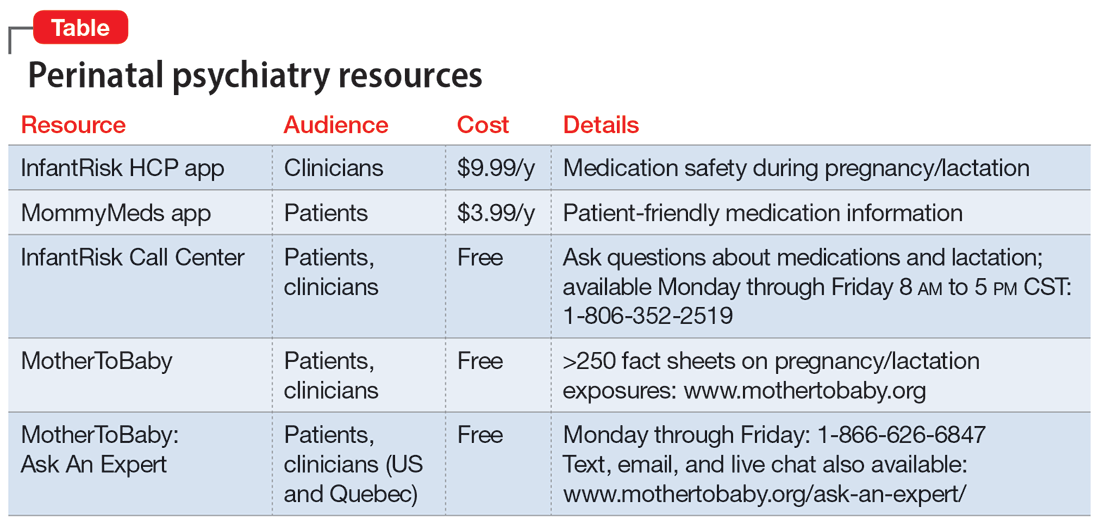

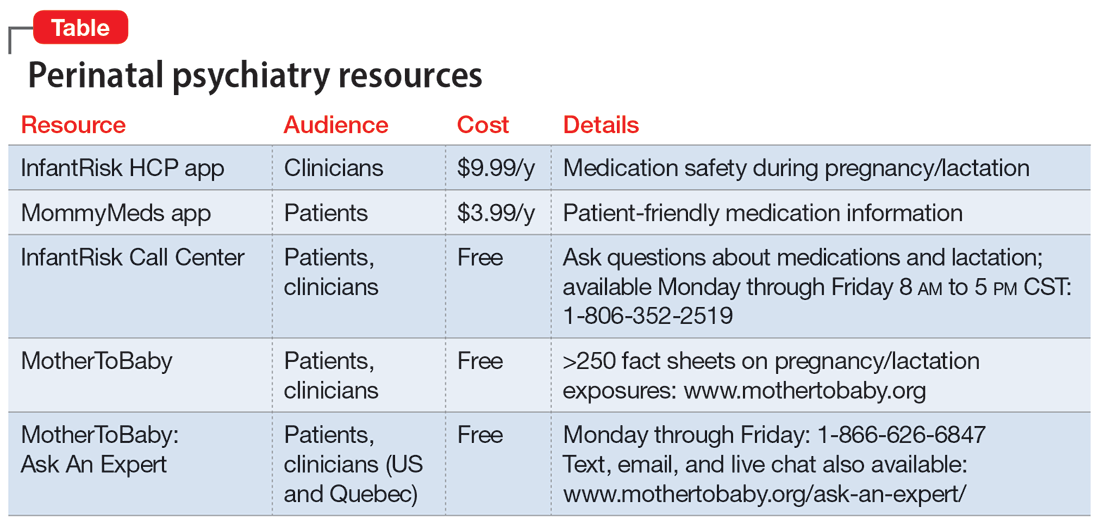

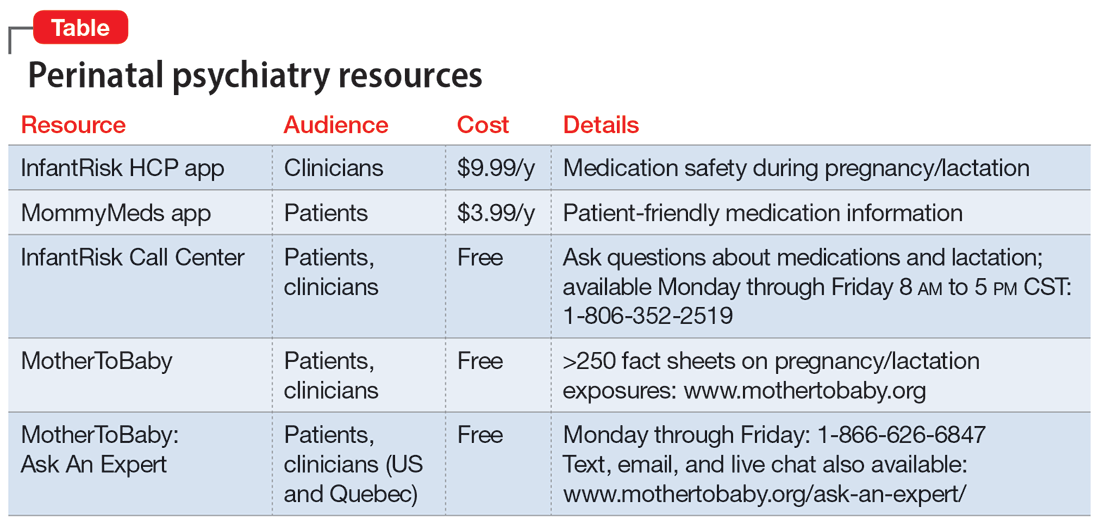

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and childbirth.1 Mental health concerns are a leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States, which has rising maternal mortality rates and glaring racial and socioeconomic disparities.2 Inconsistent perinatal psychiatry training likely contributes to perceived discomfort of patients who are pregnant.3 This is why it is critical for all psychiatrists to understand the principles of perinatal psychiatry. Here is a brief description of 5 key principles.

1. Discuss preconception planning

Reproductive life planning should occur with all patients who are capable of becoming pregnant. This planning should include not just a risks/benefits analysis and anticipatory planning regarding medications but also a discussion of prior perinatal symptoms, pregnancy intentions and contraception (especially in light of increasingly limited access to abortion), and the bidirectional nature of pregnancy and mental health conditions.

The acronym PATH provides a framework for these conversations:

- Pregnancy Attitudes: “Do you think you might like to have (more) children at some point?”

- Timing: “If considering future parenthood, when do you think that might be?”

- How important is prevention: “How important is it to you to prevent pregnancy (until then)?”4

2. Focus on perinatal mental health

Discussion often centers on medication risks to the fetus at the expense of considering risks of under- or nontreatment for both members of the dyad. Undertreating perinatal mental health conditions results in dual exposures (medication and illness), and untreated illness is associated with negative effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes and the well-being of the parent and offspring.1

3. Resist experimentation

It is common for clinicians to reflexively switch patients who are pregnant from an effective medication to one viewed as the “safest” or “best” because it has more data. This exposes the fetus to 2 medications and the dyad to potential symptoms of the illness. Decisions about medication changes should instead be made on an individual basis considering the risks and benefits of all exposures as well as the patient’s current symptoms, previous treatment, and family history.

4. Collaborate and communicate

Despite effective interventions, many perinatal mental health conditions go untreated.1 Normalize perinatal mental health symptoms with patients to reduce stigma and barriers to disclosure, and respect their decisions regarding perinatal medication use. Proper communication with the obstetric team ensures appropriate perinatal mental health screening and fetal monitoring (eg, possible fetal growth ultrasounds for a patient taking prazosin, or assessing for neonatal adaptation syndrome if there is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure in utero).

5. Recognize your limitations

Our understanding of psychotropics’ teratogenicity is constantly evolving, and we must recognize when we don’t know something. In addition to medication databases such as Reprotox (https://reprotox.org/) and LactMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/), several perinatal psychiatry resources are available for both patients and clinicians (Table). Additionally, Postpartum Support International maintains a National Perinatal Consult Line (1-877-499-4773) as well as a list of state perinatal psychiatry access lines (https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/state-perinatal-psychiatry-access-lines/) for clinicians. The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org) is also a helpful resource for clinicians.

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

1. Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, et al. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. April 29, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states

2. Singh GK. Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(1):29-42. doi:10.21106/ijma.444

3. Weinreb L, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, et al. What happens to mental health treatment during pregnancy? Women’s experience with prescribing providers. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(3):349-355. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9293-7

4. Callegari LS, Aiken AR, Dehlendorf C, et al. Addressing potential pitfalls of reproductive life planning with patient-centered counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.004

Reassuring data on stimulants for ADHD in kids and later substance abuse

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.

“While stimulant medication is the first-line treatment most often recommended for most persons with ADHD, by not following through on evaluations, parents also miss the opportunity to learn about nonpharmacological strategies that might also be helpful to help cope with ADHD symptoms and its potential co-occurring challenges,” she added.

Dr. Schweitzer also noted that many parents hope their children will outgrow the symptoms without realizing that by not obtaining an evaluation and treatment for their child, there is an associated cost, including less than optimal academic performance, social relationships, and emotional health.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD was a National Institute of Mental Health cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and under a National Institute on Drug Abuse contract followed by a data analysis grant. Dr. Molina reported grants from the NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.

“While stimulant medication is the first-line treatment most often recommended for most persons with ADHD, by not following through on evaluations, parents also miss the opportunity to learn about nonpharmacological strategies that might also be helpful to help cope with ADHD symptoms and its potential co-occurring challenges,” she added.

Dr. Schweitzer also noted that many parents hope their children will outgrow the symptoms without realizing that by not obtaining an evaluation and treatment for their child, there is an associated cost, including less than optimal academic performance, social relationships, and emotional health.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD was a National Institute of Mental Health cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and under a National Institute on Drug Abuse contract followed by a data analysis grant. Dr. Molina reported grants from the NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Throughout rigorous analyses, and after accounting for more than 70 variables in this longitudinal sample of children with ADHD taking stimulants, we did not find an association with later substance use,” lead investigator Brooke Molina, PhD, director of the youth and family research program at the University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Protective effect?

Owing to symptoms of impulsivity inherent to ADHD, the disorder itself carries a risk for elevated substance use, the investigators note.

They speculate that this may be why some previous research suggests prescription stimulants reduce the risk of subsequent substance use disorder. However, other studies have found no such protective link.

To shed more light on the issue, the investigators used data from the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD, a multicenter, 14-month randomized clinical trial of medication and behavioral therapy for children with ADHD. However, for the purposes of the present study, investigators focused only on stimulant use in children.

At the time of recruitment, the children were aged 7-9 and had been diagnosed with ADHD between 1994 and 1996.

Investigators assessed the participants prior to randomization, at months 3 and 9, and at the end of treatment. They were then followed for 16 years and were assessed at years 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 until a mean age of 25.

During 12-, 14-, and 16-year follow-up, participants completed a questionnaire on their use of alcohol, marijuana, cigarettes, and several illicit and prescription drugs.

Investigators collected information on participants’ stimulant treatment via the Services for Children and Adolescents Parent Interview until they reached age 18. After that, participants reported their own stimulant treatment.

A total of 579 participants were included in the analysis. Of these, 61% were White, 20% were Black, and 8% were Hispanic.

Decline in stimulant use over time

The analysis showed that stimulant use declined “precipitously” over time – from 60% at the 2- and 3-year assessments to an average of 7% during early adulthood.

The investigators also found that for some participants, substance use increased steadily through adolescence and remained stable through early adulthood. For instance, 36.5% of the adolescents in the total cohort reported smoking tobacco daily, and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week.

In addition, approximately 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week, and 6% reported “other” substance use, which included sedative misuse, heroin, inhalants, hallucinogens, or other substances taken to “get high.”

After accounting for developmental trends in substance use in the sample through adolescence into early adulthood with several rigorous statistical models, the researchers found no association between current or prior stimulant treatment and cigarette, marijuana, alcohol, or other substance use, with one exception.

While cumulative stimulant treatment was associated with increased heavy drinking, the effect size of this association was small. Each additional year of cumulative stimulant use was estimated to increase participants’ likelihood of any binge drinking/drunkenness vs. none in the past year by 4% (95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.08; P =.03).

When the investigators used a causal analytic method to account for age and other time-varying characteristics, including household income, behavior problems, and parental support, there was no evidence that current (B range, –0.62-0.34) or prior stimulant treatment (B range, –0.06-0.70) or their interaction (B range, –0.49-0.86) was associated with substance use in adulthood.

Dr. Molina noted that although participants were recruited from multiple sites, the sample may not be generalizable because children and parents who present for an intensive treatment study such as this are not necessarily representative of the general ADHD population.

Reassuring findings

In a comment, Julie Schweitzer, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, said she hopes the study findings will quell the stigma surrounding stimulant use by children with ADHD.

“Parents’ fears that stimulant use will lead to a substance use disorder inhibits them from bringing their children for an ADHD evaluation, thus reducing the likelihood that they will receive timely treatment,” Dr. Schweitzer said.

“While stimulant medication is the first-line treatment most often recommended for most persons with ADHD, by not following through on evaluations, parents also miss the opportunity to learn about nonpharmacological strategies that might also be helpful to help cope with ADHD symptoms and its potential co-occurring challenges,” she added.

Dr. Schweitzer also noted that many parents hope their children will outgrow the symptoms without realizing that by not obtaining an evaluation and treatment for their child, there is an associated cost, including less than optimal academic performance, social relationships, and emotional health.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD was a National Institute of Mental Health cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and under a National Institute on Drug Abuse contract followed by a data analysis grant. Dr. Molina reported grants from the NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Concussion may not affect IQ in children

data suggest.

In a multicenter study of almost 900 children with concussion or orthopedic injury, differences between groups in full-scale IQ (Cohen’s d = 0.13) and matrix reasoning scores (d = 0.16) were small.

“We draw the inference that IQ scores are unchanged, in the sense that they’re not different from [those of] kids with other types of injuries that don’t involve the brain,” said study author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury and a professor of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.).

The study was published in Pediatrics.

A representative sample

The investigators analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies of children who were treated for concussion or mild orthopedic injury at two hospitals in the United States and five in Canada. Participants were aged 8-17 years and were recruited within 24 hours of the index event. Patients in the United States completed IQ and performance validity testing at 3-18 days after injury. Patients in Canada did so at 3 months after injury. The study used the short-form IQ test. The investigators included 866 children in their analysis.

Using linear modeling, Bayesian analysis, and multigroup factor analysis, the researchers found “very small group differences” in full-scale IQ scores between the two groups. Mean IQ was 104.95 for the concussion group and 106.08 for the orthopedic-injury group. Matrix reasoning scores were 52.28 and 53.81 for the concussion and orthopedic-injury groups, respectively.

Vocabulary scores did not differ between the two groups (53.25 for the concussion group and 53.27 for the orthopedic-injury group).

The study population is “pretty representative” from a demographic perspective, although it was predominantly White, said Dr. Yeates. “On the other hand, we did look at socioeconomic status, and that didn’t seem to alter the findings at all.”

The sample size is one of the study’s strengths, said Dr. Yeates. “Having 866 kids is far larger, I think, than just about any other study out there.” Drawing from seven children’s hospitals in North America is another strength. “Previous studies, in addition to having smaller samples, were from a single site and often recruited from a clinic population, not a representative group for a general population of kids with concussion.”

The findings must be interpreted precisely, however. “We don’t have actual preinjury data, so the more precise way of describing the findings is to say they’re not different from kids who are very similar to them demographically, have the same risk factors for injuries, and had a similar experience of a traumatic injury,” said Dr. Yeates. “The IQ scores for both groups are smack dab in the average range.”

Overall, the results are encouraging. “There’s been a lot of bad news in the media and in the science about concussion that worries patients, so it’s nice to be able to provide a little bit of balance,” said Dr. Yeates. “The message I give parents is that most kids recover within 2-4 weeks, and we’re much better now at predicting who’s going to [recover] and who isn’t, and that helps, too, so that we can focus our intervention on kids who are most at risk.”

Some children will have persisting symptoms, but evidence-based treatments are lacking. “I think that’ll be a really important direction for the future,” said Dr. Yeates.

Graduated return

Commenting on the findings, Michael Esser, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, and an associate professor in pediatrics at the University of Calgary, said that they can help allay parents’ concerns about concussions. “It can also be of help for clinicians who want to have evidence to reassure families and promote a graduated return to activities. In particular, the study would support the philosophy of a graduated return to school or work, after a brief period of rest, following concussion.” Dr. Esser did not participate in the study.

The research is also noteworthy because it acknowledges that the differences in the design and methodology used in prior studies may explain the apparent disagreement over how concussion may influence cognitive function.

“This is an important message,” said Dr. Esser. “Families struggle with determining the merit of a lot of information due to the myriad of social media comments about concussion and the risk for cognitive impairment. Therefore, it is important that conclusions with a significant implication are evaluated with a variety of approaches.”

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Dr. Yeates disclosed relationships with the American Psychological Association, Guilford Press, and Cambridge University Press. He has received grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, Brain Canada Foundation, and the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board. He also has relationships with the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, National Pediatric Rehabilitation Resource Center, Center for Pediatric Rehabilitation, and Virginia Tech University. Dr. Esser had no relevant relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

data suggest.

In a multicenter study of almost 900 children with concussion or orthopedic injury, differences between groups in full-scale IQ (Cohen’s d = 0.13) and matrix reasoning scores (d = 0.16) were small.

“We draw the inference that IQ scores are unchanged, in the sense that they’re not different from [those of] kids with other types of injuries that don’t involve the brain,” said study author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury and a professor of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.).

The study was published in Pediatrics.

A representative sample

The investigators analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies of children who were treated for concussion or mild orthopedic injury at two hospitals in the United States and five in Canada. Participants were aged 8-17 years and were recruited within 24 hours of the index event. Patients in the United States completed IQ and performance validity testing at 3-18 days after injury. Patients in Canada did so at 3 months after injury. The study used the short-form IQ test. The investigators included 866 children in their analysis.

Using linear modeling, Bayesian analysis, and multigroup factor analysis, the researchers found “very small group differences” in full-scale IQ scores between the two groups. Mean IQ was 104.95 for the concussion group and 106.08 for the orthopedic-injury group. Matrix reasoning scores were 52.28 and 53.81 for the concussion and orthopedic-injury groups, respectively.

Vocabulary scores did not differ between the two groups (53.25 for the concussion group and 53.27 for the orthopedic-injury group).

The study population is “pretty representative” from a demographic perspective, although it was predominantly White, said Dr. Yeates. “On the other hand, we did look at socioeconomic status, and that didn’t seem to alter the findings at all.”

The sample size is one of the study’s strengths, said Dr. Yeates. “Having 866 kids is far larger, I think, than just about any other study out there.” Drawing from seven children’s hospitals in North America is another strength. “Previous studies, in addition to having smaller samples, were from a single site and often recruited from a clinic population, not a representative group for a general population of kids with concussion.”

The findings must be interpreted precisely, however. “We don’t have actual preinjury data, so the more precise way of describing the findings is to say they’re not different from kids who are very similar to them demographically, have the same risk factors for injuries, and had a similar experience of a traumatic injury,” said Dr. Yeates. “The IQ scores for both groups are smack dab in the average range.”

Overall, the results are encouraging. “There’s been a lot of bad news in the media and in the science about concussion that worries patients, so it’s nice to be able to provide a little bit of balance,” said Dr. Yeates. “The message I give parents is that most kids recover within 2-4 weeks, and we’re much better now at predicting who’s going to [recover] and who isn’t, and that helps, too, so that we can focus our intervention on kids who are most at risk.”

Some children will have persisting symptoms, but evidence-based treatments are lacking. “I think that’ll be a really important direction for the future,” said Dr. Yeates.

Graduated return

Commenting on the findings, Michael Esser, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, and an associate professor in pediatrics at the University of Calgary, said that they can help allay parents’ concerns about concussions. “It can also be of help for clinicians who want to have evidence to reassure families and promote a graduated return to activities. In particular, the study would support the philosophy of a graduated return to school or work, after a brief period of rest, following concussion.” Dr. Esser did not participate in the study.

The research is also noteworthy because it acknowledges that the differences in the design and methodology used in prior studies may explain the apparent disagreement over how concussion may influence cognitive function.

“This is an important message,” said Dr. Esser. “Families struggle with determining the merit of a lot of information due to the myriad of social media comments about concussion and the risk for cognitive impairment. Therefore, it is important that conclusions with a significant implication are evaluated with a variety of approaches.”

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Dr. Yeates disclosed relationships with the American Psychological Association, Guilford Press, and Cambridge University Press. He has received grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, Brain Canada Foundation, and the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board. He also has relationships with the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, National Pediatric Rehabilitation Resource Center, Center for Pediatric Rehabilitation, and Virginia Tech University. Dr. Esser had no relevant relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

data suggest.

In a multicenter study of almost 900 children with concussion or orthopedic injury, differences between groups in full-scale IQ (Cohen’s d = 0.13) and matrix reasoning scores (d = 0.16) were small.

“We draw the inference that IQ scores are unchanged, in the sense that they’re not different from [those of] kids with other types of injuries that don’t involve the brain,” said study author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury and a professor of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.).

The study was published in Pediatrics.

A representative sample

The investigators analyzed data from two prospective cohort studies of children who were treated for concussion or mild orthopedic injury at two hospitals in the United States and five in Canada. Participants were aged 8-17 years and were recruited within 24 hours of the index event. Patients in the United States completed IQ and performance validity testing at 3-18 days after injury. Patients in Canada did so at 3 months after injury. The study used the short-form IQ test. The investigators included 866 children in their analysis.

Using linear modeling, Bayesian analysis, and multigroup factor analysis, the researchers found “very small group differences” in full-scale IQ scores between the two groups. Mean IQ was 104.95 for the concussion group and 106.08 for the orthopedic-injury group. Matrix reasoning scores were 52.28 and 53.81 for the concussion and orthopedic-injury groups, respectively.

Vocabulary scores did not differ between the two groups (53.25 for the concussion group and 53.27 for the orthopedic-injury group).

The study population is “pretty representative” from a demographic perspective, although it was predominantly White, said Dr. Yeates. “On the other hand, we did look at socioeconomic status, and that didn’t seem to alter the findings at all.”

The sample size is one of the study’s strengths, said Dr. Yeates. “Having 866 kids is far larger, I think, than just about any other study out there.” Drawing from seven children’s hospitals in North America is another strength. “Previous studies, in addition to having smaller samples, were from a single site and often recruited from a clinic population, not a representative group for a general population of kids with concussion.”

The findings must be interpreted precisely, however. “We don’t have actual preinjury data, so the more precise way of describing the findings is to say they’re not different from kids who are very similar to them demographically, have the same risk factors for injuries, and had a similar experience of a traumatic injury,” said Dr. Yeates. “The IQ scores for both groups are smack dab in the average range.”

Overall, the results are encouraging. “There’s been a lot of bad news in the media and in the science about concussion that worries patients, so it’s nice to be able to provide a little bit of balance,” said Dr. Yeates. “The message I give parents is that most kids recover within 2-4 weeks, and we’re much better now at predicting who’s going to [recover] and who isn’t, and that helps, too, so that we can focus our intervention on kids who are most at risk.”

Some children will have persisting symptoms, but evidence-based treatments are lacking. “I think that’ll be a really important direction for the future,” said Dr. Yeates.

Graduated return

Commenting on the findings, Michael Esser, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, and an associate professor in pediatrics at the University of Calgary, said that they can help allay parents’ concerns about concussions. “It can also be of help for clinicians who want to have evidence to reassure families and promote a graduated return to activities. In particular, the study would support the philosophy of a graduated return to school or work, after a brief period of rest, following concussion.” Dr. Esser did not participate in the study.

The research is also noteworthy because it acknowledges that the differences in the design and methodology used in prior studies may explain the apparent disagreement over how concussion may influence cognitive function.

“This is an important message,” said Dr. Esser. “Families struggle with determining the merit of a lot of information due to the myriad of social media comments about concussion and the risk for cognitive impairment. Therefore, it is important that conclusions with a significant implication are evaluated with a variety of approaches.”

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Dr. Yeates disclosed relationships with the American Psychological Association, Guilford Press, and Cambridge University Press. He has received grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institutes of Health, Brain Canada Foundation, and the National Football League Scientific Advisory Board. He also has relationships with the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, National Pediatric Rehabilitation Resource Center, Center for Pediatric Rehabilitation, and Virginia Tech University. Dr. Esser had no relevant relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Exercise program boosted physical, but not mental, health in young children with overweight