User login

AAP issues clinical update to cerebral palsy guidelines

Updated clinical guidelines for the early diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy have been issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Coauthored with the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine, the report builds on new evidence for improved care and outcomes since the 2006 consensus guidelines.

Cerebral palsy, the most common neuromotor disorder of childhood, is often accompanied by cognitive impairments, epilepsy, sensory impairments, behavioral problems, communication difficulties, breathing and sleep problems, gastrointestinal and nutritional problems, and bone and orthopedic problems.

In the United States, the estimated prevalence of cerebral palsy ranges from 1.5 to 4 per 1,000 live births.

“Early identification and initiation of evidence-based motor therapies can improve outcomes by taking advantage of the neuroplasticity in the infant brain,” said the guideline authors in an executive summary.

The guideline, published in Pediatrics, is directed to primary care physicians with pediatrics, family practice, or internal medicine training. “It’s a much more comprehensive overview of the important role that primary care providers play in the lifetime care of people with cerebral palsy,” explained Garey Noritz, MD, chair of the 2021-2022 Executive Committee of the Council on Children with Disabilities. Dr. Noritz, a professor of pediatrics at Ohio State University and division chief of the complex health care program at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, said: “The combined efforts of the primary care physician and specialty providers are needed to achieve the best outcomes.”

The AAP recommends that primary care pediatricians, neonatologists, and other specialists caring for hospitalized newborns recognize those at high risk of cerebral palsy, diagnose them as early as possible, and promptly refer them for therapy. Primary care physicians are advised to identify motor delays early by formalizing standardized developmental surveillance and screening at 9, 18, and 30 months, and to implement family-centered care across multiple specialists.

“If a motor disorder is suspected, primary care physicians should simultaneously begin a medical evaluation, refer to a specialist for definitive diagnosis, and to therapists for treatment,” Dr. Noritz emphasized.

“The earlier any possible movement disorder is recognized and intervention begins, the better a child can develop a gait pattern and work toward living an independent life, said Manish N. Shah, MD, associate professor of pediatric neurosurgery at the University of Texas, Houston, who was not involved in developing the guidelines.

For children in whom physical therapy and medication have not reduced leg spasticity, a minimally invasive spinal procedure can help release contracted tendons and encourage independent walking. The optimal age for selective dorsal rhizotomy is about 4 years, said Dr. Shah, who is director of the Texas Comprehensive Spasticity Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. “You can turn these children into walkers. As adults, they can get jobs, have their own families. It’s life-changing.”

Importantly, the guidelines address the health care disparities leading to a higher prevalence of cerebral palsy in Black children and in those from families with lower socioeconomic status. “Efforts to combat racism and eliminate barriers to culturally sensitive prenatal, perinatal, and later pediatric care may help to improve outcomes for all children with cerebral palsy,” the authors said.

“Every child with cerebral palsy needs an individual plan, but only 30% or 40% are getting interventions,” said Dr. Shah. The updated guidelines could help payers rethink the 15-20 visits a year that are often approved, compared with the 2-3 visits per week that are needed for speech, physical, and occupational therapy, he pointed out.

“Financial issues often compromise the interdisciplinary and coordinated care associated with favorable outcomes in children with cerebral palsy,” said Heidi Feldman, MD, PhD, a developmental and behavioral pediatric specialist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine Children’s Health’s Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. “With a new guideline, there may be greater willingness to fund these essential services.”

In the meantime, the AAP recommends that pediatricians advise families about available medical, social, and educational services, such as early intervention services, the Title V Maternal and Child Health block grant program, and special education services through the public school system.

Children with cerebral palsy need the same standardized primary care as any child, including the full schedule of recommended vaccinations and vision and hearing testing. They also need to be monitored and treated for the many problems that commonly co-occur, including chronic pain.

When secondary complications arise, the frequency of visits should increase.

Pneumonia, the leading cause of death in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy, can be prevented or minimized through immunization against respiratory diseases and screening for signs and symptoms of aspiration and sleep-disordered breathing.

The AAP also recommends that symptoms or functional declines undergo full investigation into other potential causes.

Since the sedentary lifestyle associated with cerebral palsy is now known to be related to the higher rates of cardiovascular complications in this patient population, the AAP recommends more attention be paid to physical activity and a healthy diet early in life. Pediatricians are advised to help families locate suitable opportunities for adaptive sports and recreation.

Almost 50% of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy have intellectual disability, 60%-80% have difficulty speaking, and about 25% are nonverbal. To address this, pediatricians should maximize the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices and involve experts in speech and language pathology, according to the guidelines.

“Many individuals with cerebral palsy and severe motor limitations have active, creative minds, and may need assistive technology, such as electronic talking devices, to demonstrate that mental life,” said Dr. Feldman. “Primary care clinicians should advocate for assistive technology.”

For challenging behavior, especially in the patient with limited verbal skills, potential nonbehavioral culprits such as constipation, esophageal reflux disease, and musculoskeletal or dental pain must be ruled out.

In the lead-up to adolescence, youth with cerebral palsy must be prepared for puberty, menstruation, and healthy, safe sexual relationships, much like their nonaffected peers. Since a disproportionate number of children with cerebral palsy experience neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, however, family stressors should be identified and caregivers referred for support services.

For the transition from pediatric to adult health care, the AAP recommends that structured planning begin between 12 and 14 years of age. Before transfer, the pediatrician should prepare a comprehensive medical summary with the input of the patient, parent/guardian, and pediatric subspecialists.

Without a proper handoff, “there is an increased risk of morbidity, medical complications, unnecessary emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and procedures,” the authors warned.

Transitions are likely to run more smoothly when youth are given the opportunity to understand their medical condition and be involved in decisions about their health. With this in mind, the AAP recommends that pediatricians actively discourage overprotective parents from getting in the way of their child developing “maximal independence.”

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors, Dr. Shah, or Dr. Feldman.

*This story was updated on Nov. 28, 2022.

Updated clinical guidelines for the early diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy have been issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Coauthored with the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine, the report builds on new evidence for improved care and outcomes since the 2006 consensus guidelines.

Cerebral palsy, the most common neuromotor disorder of childhood, is often accompanied by cognitive impairments, epilepsy, sensory impairments, behavioral problems, communication difficulties, breathing and sleep problems, gastrointestinal and nutritional problems, and bone and orthopedic problems.

In the United States, the estimated prevalence of cerebral palsy ranges from 1.5 to 4 per 1,000 live births.

“Early identification and initiation of evidence-based motor therapies can improve outcomes by taking advantage of the neuroplasticity in the infant brain,” said the guideline authors in an executive summary.

The guideline, published in Pediatrics, is directed to primary care physicians with pediatrics, family practice, or internal medicine training. “It’s a much more comprehensive overview of the important role that primary care providers play in the lifetime care of people with cerebral palsy,” explained Garey Noritz, MD, chair of the 2021-2022 Executive Committee of the Council on Children with Disabilities. Dr. Noritz, a professor of pediatrics at Ohio State University and division chief of the complex health care program at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, said: “The combined efforts of the primary care physician and specialty providers are needed to achieve the best outcomes.”

The AAP recommends that primary care pediatricians, neonatologists, and other specialists caring for hospitalized newborns recognize those at high risk of cerebral palsy, diagnose them as early as possible, and promptly refer them for therapy. Primary care physicians are advised to identify motor delays early by formalizing standardized developmental surveillance and screening at 9, 18, and 30 months, and to implement family-centered care across multiple specialists.

“If a motor disorder is suspected, primary care physicians should simultaneously begin a medical evaluation, refer to a specialist for definitive diagnosis, and to therapists for treatment,” Dr. Noritz emphasized.

“The earlier any possible movement disorder is recognized and intervention begins, the better a child can develop a gait pattern and work toward living an independent life, said Manish N. Shah, MD, associate professor of pediatric neurosurgery at the University of Texas, Houston, who was not involved in developing the guidelines.

For children in whom physical therapy and medication have not reduced leg spasticity, a minimally invasive spinal procedure can help release contracted tendons and encourage independent walking. The optimal age for selective dorsal rhizotomy is about 4 years, said Dr. Shah, who is director of the Texas Comprehensive Spasticity Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. “You can turn these children into walkers. As adults, they can get jobs, have their own families. It’s life-changing.”

Importantly, the guidelines address the health care disparities leading to a higher prevalence of cerebral palsy in Black children and in those from families with lower socioeconomic status. “Efforts to combat racism and eliminate barriers to culturally sensitive prenatal, perinatal, and later pediatric care may help to improve outcomes for all children with cerebral palsy,” the authors said.

“Every child with cerebral palsy needs an individual plan, but only 30% or 40% are getting interventions,” said Dr. Shah. The updated guidelines could help payers rethink the 15-20 visits a year that are often approved, compared with the 2-3 visits per week that are needed for speech, physical, and occupational therapy, he pointed out.

“Financial issues often compromise the interdisciplinary and coordinated care associated with favorable outcomes in children with cerebral palsy,” said Heidi Feldman, MD, PhD, a developmental and behavioral pediatric specialist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine Children’s Health’s Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. “With a new guideline, there may be greater willingness to fund these essential services.”

In the meantime, the AAP recommends that pediatricians advise families about available medical, social, and educational services, such as early intervention services, the Title V Maternal and Child Health block grant program, and special education services through the public school system.

Children with cerebral palsy need the same standardized primary care as any child, including the full schedule of recommended vaccinations and vision and hearing testing. They also need to be monitored and treated for the many problems that commonly co-occur, including chronic pain.

When secondary complications arise, the frequency of visits should increase.

Pneumonia, the leading cause of death in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy, can be prevented or minimized through immunization against respiratory diseases and screening for signs and symptoms of aspiration and sleep-disordered breathing.

The AAP also recommends that symptoms or functional declines undergo full investigation into other potential causes.

Since the sedentary lifestyle associated with cerebral palsy is now known to be related to the higher rates of cardiovascular complications in this patient population, the AAP recommends more attention be paid to physical activity and a healthy diet early in life. Pediatricians are advised to help families locate suitable opportunities for adaptive sports and recreation.

Almost 50% of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy have intellectual disability, 60%-80% have difficulty speaking, and about 25% are nonverbal. To address this, pediatricians should maximize the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices and involve experts in speech and language pathology, according to the guidelines.

“Many individuals with cerebral palsy and severe motor limitations have active, creative minds, and may need assistive technology, such as electronic talking devices, to demonstrate that mental life,” said Dr. Feldman. “Primary care clinicians should advocate for assistive technology.”

For challenging behavior, especially in the patient with limited verbal skills, potential nonbehavioral culprits such as constipation, esophageal reflux disease, and musculoskeletal or dental pain must be ruled out.

In the lead-up to adolescence, youth with cerebral palsy must be prepared for puberty, menstruation, and healthy, safe sexual relationships, much like their nonaffected peers. Since a disproportionate number of children with cerebral palsy experience neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, however, family stressors should be identified and caregivers referred for support services.

For the transition from pediatric to adult health care, the AAP recommends that structured planning begin between 12 and 14 years of age. Before transfer, the pediatrician should prepare a comprehensive medical summary with the input of the patient, parent/guardian, and pediatric subspecialists.

Without a proper handoff, “there is an increased risk of morbidity, medical complications, unnecessary emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and procedures,” the authors warned.

Transitions are likely to run more smoothly when youth are given the opportunity to understand their medical condition and be involved in decisions about their health. With this in mind, the AAP recommends that pediatricians actively discourage overprotective parents from getting in the way of their child developing “maximal independence.”

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors, Dr. Shah, or Dr. Feldman.

*This story was updated on Nov. 28, 2022.

Updated clinical guidelines for the early diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy have been issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Coauthored with the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine, the report builds on new evidence for improved care and outcomes since the 2006 consensus guidelines.

Cerebral palsy, the most common neuromotor disorder of childhood, is often accompanied by cognitive impairments, epilepsy, sensory impairments, behavioral problems, communication difficulties, breathing and sleep problems, gastrointestinal and nutritional problems, and bone and orthopedic problems.

In the United States, the estimated prevalence of cerebral palsy ranges from 1.5 to 4 per 1,000 live births.

“Early identification and initiation of evidence-based motor therapies can improve outcomes by taking advantage of the neuroplasticity in the infant brain,” said the guideline authors in an executive summary.

The guideline, published in Pediatrics, is directed to primary care physicians with pediatrics, family practice, or internal medicine training. “It’s a much more comprehensive overview of the important role that primary care providers play in the lifetime care of people with cerebral palsy,” explained Garey Noritz, MD, chair of the 2021-2022 Executive Committee of the Council on Children with Disabilities. Dr. Noritz, a professor of pediatrics at Ohio State University and division chief of the complex health care program at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, said: “The combined efforts of the primary care physician and specialty providers are needed to achieve the best outcomes.”

The AAP recommends that primary care pediatricians, neonatologists, and other specialists caring for hospitalized newborns recognize those at high risk of cerebral palsy, diagnose them as early as possible, and promptly refer them for therapy. Primary care physicians are advised to identify motor delays early by formalizing standardized developmental surveillance and screening at 9, 18, and 30 months, and to implement family-centered care across multiple specialists.

“If a motor disorder is suspected, primary care physicians should simultaneously begin a medical evaluation, refer to a specialist for definitive diagnosis, and to therapists for treatment,” Dr. Noritz emphasized.

“The earlier any possible movement disorder is recognized and intervention begins, the better a child can develop a gait pattern and work toward living an independent life, said Manish N. Shah, MD, associate professor of pediatric neurosurgery at the University of Texas, Houston, who was not involved in developing the guidelines.

For children in whom physical therapy and medication have not reduced leg spasticity, a minimally invasive spinal procedure can help release contracted tendons and encourage independent walking. The optimal age for selective dorsal rhizotomy is about 4 years, said Dr. Shah, who is director of the Texas Comprehensive Spasticity Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. “You can turn these children into walkers. As adults, they can get jobs, have their own families. It’s life-changing.”

Importantly, the guidelines address the health care disparities leading to a higher prevalence of cerebral palsy in Black children and in those from families with lower socioeconomic status. “Efforts to combat racism and eliminate barriers to culturally sensitive prenatal, perinatal, and later pediatric care may help to improve outcomes for all children with cerebral palsy,” the authors said.

“Every child with cerebral palsy needs an individual plan, but only 30% or 40% are getting interventions,” said Dr. Shah. The updated guidelines could help payers rethink the 15-20 visits a year that are often approved, compared with the 2-3 visits per week that are needed for speech, physical, and occupational therapy, he pointed out.

“Financial issues often compromise the interdisciplinary and coordinated care associated with favorable outcomes in children with cerebral palsy,” said Heidi Feldman, MD, PhD, a developmental and behavioral pediatric specialist at Stanford (Calif.) Medicine Children’s Health’s Johnson Center for Pregnancy and Newborn Services. “With a new guideline, there may be greater willingness to fund these essential services.”

In the meantime, the AAP recommends that pediatricians advise families about available medical, social, and educational services, such as early intervention services, the Title V Maternal and Child Health block grant program, and special education services through the public school system.

Children with cerebral palsy need the same standardized primary care as any child, including the full schedule of recommended vaccinations and vision and hearing testing. They also need to be monitored and treated for the many problems that commonly co-occur, including chronic pain.

When secondary complications arise, the frequency of visits should increase.

Pneumonia, the leading cause of death in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy, can be prevented or minimized through immunization against respiratory diseases and screening for signs and symptoms of aspiration and sleep-disordered breathing.

The AAP also recommends that symptoms or functional declines undergo full investigation into other potential causes.

Since the sedentary lifestyle associated with cerebral palsy is now known to be related to the higher rates of cardiovascular complications in this patient population, the AAP recommends more attention be paid to physical activity and a healthy diet early in life. Pediatricians are advised to help families locate suitable opportunities for adaptive sports and recreation.

Almost 50% of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy have intellectual disability, 60%-80% have difficulty speaking, and about 25% are nonverbal. To address this, pediatricians should maximize the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices and involve experts in speech and language pathology, according to the guidelines.

“Many individuals with cerebral palsy and severe motor limitations have active, creative minds, and may need assistive technology, such as electronic talking devices, to demonstrate that mental life,” said Dr. Feldman. “Primary care clinicians should advocate for assistive technology.”

For challenging behavior, especially in the patient with limited verbal skills, potential nonbehavioral culprits such as constipation, esophageal reflux disease, and musculoskeletal or dental pain must be ruled out.

In the lead-up to adolescence, youth with cerebral palsy must be prepared for puberty, menstruation, and healthy, safe sexual relationships, much like their nonaffected peers. Since a disproportionate number of children with cerebral palsy experience neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, however, family stressors should be identified and caregivers referred for support services.

For the transition from pediatric to adult health care, the AAP recommends that structured planning begin between 12 and 14 years of age. Before transfer, the pediatrician should prepare a comprehensive medical summary with the input of the patient, parent/guardian, and pediatric subspecialists.

Without a proper handoff, “there is an increased risk of morbidity, medical complications, unnecessary emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and procedures,” the authors warned.

Transitions are likely to run more smoothly when youth are given the opportunity to understand their medical condition and be involved in decisions about their health. With this in mind, the AAP recommends that pediatricians actively discourage overprotective parents from getting in the way of their child developing “maximal independence.”

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors, Dr. Shah, or Dr. Feldman.

*This story was updated on Nov. 28, 2022.

FROM PEDIATRICS

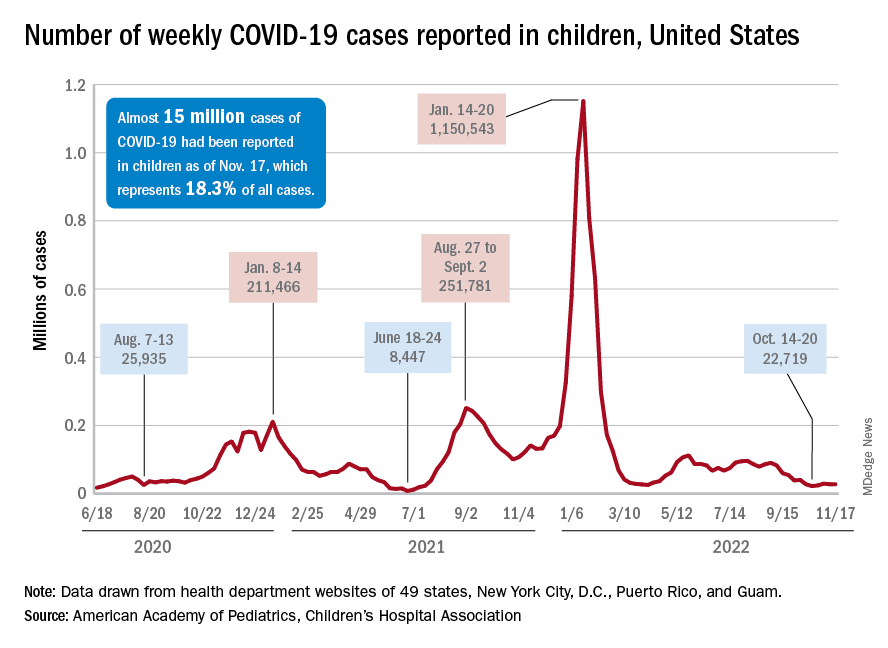

Children and COVID: Weekly cases maintain a low-level plateau

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Local-level youth suicides reflect mental health care shortages

Rates of youth suicides at the county level increased as mental health professional shortages increased, based on data from more than 5,000 youth suicides across all counties in the United States.

Suicide remains the second leading cause of death among adolescents in the United States, and shortages of pediatric mental health providers are well known, but the association between mental health workforce shortages and youth suicides at the local level has not been well studied, Jennifer A. Hoffmann, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies have shown few or no child psychiatrists or child-focused mental health professionals in most counties across the United States, and shortages are more likely in rural and high-poverty counties, the researchers noted.

In a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed all youth suicide data from January 2015 to Dec. 31, 2016 using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File. They used a multivariate binomial regression model to examine the association between youth suicide rates and the presence or absence of mental health care. Mental health care shortages were based on data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s assessment of the number of mental health professionals relative to the country population and the availability of nearby services. Areas identified as having shortages were designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and scored on a severity level of 0-25, with higher scores indicating greater shortages. Approximately two-thirds (67.6%) of the 3,133 counties included in the study met criteria for mental health workforce shortage areas.

The researchers identified 5,034 suicides in youth aged 5-19 years during the study period, for an annual rate of 3.99 per 100,000 individuals. Of these, 72.8% were male and 68.2% were non-Hispanic White.

Overall, a county designation of mental health care shortage was significantly associated with an increased rate of youth suicide (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.16) and also increased rate of youth firearm suicide (aIRR, 1.27) after controlling for county and socioeconomic characteristics including the presence of a children’s mental health hospital, the percentage of children without health insurance, median household income, and racial makeup of the county.

The adjusted youth suicide rate increased by 4% for every 1-point increase in the HPSA score in counties with designated mental health workforce shortages.

The adjusted youth suicide rates were higher in counties with a lower median household income, and youth suicides increased with increases in the percentages of uninsured children, the researchers wrote.

“Reducing poverty, addressing social determinants of health, and improving insurance coverage may be considered as components of a multipronged societal strategy to improve child health and reduce youth suicides,” they said. “Efforts are needed to enhance the mental health professional workforce to match current levels of need.” Possible strategies to increase the pediatric mental health workforce may include improving reimbursement and integrating mental health care into primary care and schools by expanding telehealth services.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential misclassification of demographics or cause of death, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the inability to assess actual use of mental health services or firearm ownership in a household, and the possible differences between county-level associations and those of a city, neighborhood, or individual.

However, the results indicate that mental health professional workforce shortages were associated with increased youth suicide rates, and the data may inform local-level suicide prevention efforts, they concluded.

Data support the need for early intervention

“It was very important to conduct this study at this time because mental health problems, to include suicidal ideation, continue to increase in adolescents,” Peter L. Loper Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview. “This study reinforces the immense import of sufficient mental health workforce to mitigate this increasing risk of suicide in adolescents.”

Dr. Loper said: “I believe that early intervention, or consistent access to mental health services, can go a very long way in preventing suicide in adolescents.

“I think the primary implications of this study are more relevant at the systems level, and reinforce the necessity of clinicians advocating for policies that address mental health workforce shortages in counties that are underserved,” he added.

However, “One primary barrier to increasing the number of mental health professionals at a local level, and specifically the number of child psychiatrists, is that demand is currently outpacing supply,” said Dr. Loper, a pediatrician and psychiatrist who was not involved in the study. “As the study authors cite, increasing telepsychiatry services and increasing mental health workforce specifically in the primary care setting may help offset these deficiencies,” he noted. Looking ahead, primary prevention of mental health problems by grassroots efforts is vital to stopping the trend in increased youth suicides and more mental health professionals are needed to mitigate the phenomenon of isolation and the degradation of community constructs.

As for additional research, Dr. Loper agreed with the study authors comments on the need for “more granular data” to better understand the correlation between mental health workforce and suicide in adolescents. “Data that captures city or neighborhood statistics related to mental health workforce and adolescent suicide could go a long way in our efforts to continue to better understand this very important correlation.”

The study was supported by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award. Dr. Hoffmann disclosed research funding from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality unrelated to the current study. Dr. Loper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Rates of youth suicides at the county level increased as mental health professional shortages increased, based on data from more than 5,000 youth suicides across all counties in the United States.

Suicide remains the second leading cause of death among adolescents in the United States, and shortages of pediatric mental health providers are well known, but the association between mental health workforce shortages and youth suicides at the local level has not been well studied, Jennifer A. Hoffmann, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies have shown few or no child psychiatrists or child-focused mental health professionals in most counties across the United States, and shortages are more likely in rural and high-poverty counties, the researchers noted.

In a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed all youth suicide data from January 2015 to Dec. 31, 2016 using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File. They used a multivariate binomial regression model to examine the association between youth suicide rates and the presence or absence of mental health care. Mental health care shortages were based on data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s assessment of the number of mental health professionals relative to the country population and the availability of nearby services. Areas identified as having shortages were designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and scored on a severity level of 0-25, with higher scores indicating greater shortages. Approximately two-thirds (67.6%) of the 3,133 counties included in the study met criteria for mental health workforce shortage areas.

The researchers identified 5,034 suicides in youth aged 5-19 years during the study period, for an annual rate of 3.99 per 100,000 individuals. Of these, 72.8% were male and 68.2% were non-Hispanic White.

Overall, a county designation of mental health care shortage was significantly associated with an increased rate of youth suicide (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.16) and also increased rate of youth firearm suicide (aIRR, 1.27) after controlling for county and socioeconomic characteristics including the presence of a children’s mental health hospital, the percentage of children without health insurance, median household income, and racial makeup of the county.

The adjusted youth suicide rate increased by 4% for every 1-point increase in the HPSA score in counties with designated mental health workforce shortages.

The adjusted youth suicide rates were higher in counties with a lower median household income, and youth suicides increased with increases in the percentages of uninsured children, the researchers wrote.

“Reducing poverty, addressing social determinants of health, and improving insurance coverage may be considered as components of a multipronged societal strategy to improve child health and reduce youth suicides,” they said. “Efforts are needed to enhance the mental health professional workforce to match current levels of need.” Possible strategies to increase the pediatric mental health workforce may include improving reimbursement and integrating mental health care into primary care and schools by expanding telehealth services.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential misclassification of demographics or cause of death, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the inability to assess actual use of mental health services or firearm ownership in a household, and the possible differences between county-level associations and those of a city, neighborhood, or individual.

However, the results indicate that mental health professional workforce shortages were associated with increased youth suicide rates, and the data may inform local-level suicide prevention efforts, they concluded.

Data support the need for early intervention

“It was very important to conduct this study at this time because mental health problems, to include suicidal ideation, continue to increase in adolescents,” Peter L. Loper Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview. “This study reinforces the immense import of sufficient mental health workforce to mitigate this increasing risk of suicide in adolescents.”

Dr. Loper said: “I believe that early intervention, or consistent access to mental health services, can go a very long way in preventing suicide in adolescents.

“I think the primary implications of this study are more relevant at the systems level, and reinforce the necessity of clinicians advocating for policies that address mental health workforce shortages in counties that are underserved,” he added.

However, “One primary barrier to increasing the number of mental health professionals at a local level, and specifically the number of child psychiatrists, is that demand is currently outpacing supply,” said Dr. Loper, a pediatrician and psychiatrist who was not involved in the study. “As the study authors cite, increasing telepsychiatry services and increasing mental health workforce specifically in the primary care setting may help offset these deficiencies,” he noted. Looking ahead, primary prevention of mental health problems by grassroots efforts is vital to stopping the trend in increased youth suicides and more mental health professionals are needed to mitigate the phenomenon of isolation and the degradation of community constructs.

As for additional research, Dr. Loper agreed with the study authors comments on the need for “more granular data” to better understand the correlation between mental health workforce and suicide in adolescents. “Data that captures city or neighborhood statistics related to mental health workforce and adolescent suicide could go a long way in our efforts to continue to better understand this very important correlation.”

The study was supported by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award. Dr. Hoffmann disclosed research funding from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality unrelated to the current study. Dr. Loper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Rates of youth suicides at the county level increased as mental health professional shortages increased, based on data from more than 5,000 youth suicides across all counties in the United States.

Suicide remains the second leading cause of death among adolescents in the United States, and shortages of pediatric mental health providers are well known, but the association between mental health workforce shortages and youth suicides at the local level has not been well studied, Jennifer A. Hoffmann, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies have shown few or no child psychiatrists or child-focused mental health professionals in most counties across the United States, and shortages are more likely in rural and high-poverty counties, the researchers noted.

In a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed all youth suicide data from January 2015 to Dec. 31, 2016 using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File. They used a multivariate binomial regression model to examine the association between youth suicide rates and the presence or absence of mental health care. Mental health care shortages were based on data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration’s assessment of the number of mental health professionals relative to the country population and the availability of nearby services. Areas identified as having shortages were designated as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and scored on a severity level of 0-25, with higher scores indicating greater shortages. Approximately two-thirds (67.6%) of the 3,133 counties included in the study met criteria for mental health workforce shortage areas.

The researchers identified 5,034 suicides in youth aged 5-19 years during the study period, for an annual rate of 3.99 per 100,000 individuals. Of these, 72.8% were male and 68.2% were non-Hispanic White.

Overall, a county designation of mental health care shortage was significantly associated with an increased rate of youth suicide (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.16) and also increased rate of youth firearm suicide (aIRR, 1.27) after controlling for county and socioeconomic characteristics including the presence of a children’s mental health hospital, the percentage of children without health insurance, median household income, and racial makeup of the county.

The adjusted youth suicide rate increased by 4% for every 1-point increase in the HPSA score in counties with designated mental health workforce shortages.

The adjusted youth suicide rates were higher in counties with a lower median household income, and youth suicides increased with increases in the percentages of uninsured children, the researchers wrote.

“Reducing poverty, addressing social determinants of health, and improving insurance coverage may be considered as components of a multipronged societal strategy to improve child health and reduce youth suicides,” they said. “Efforts are needed to enhance the mental health professional workforce to match current levels of need.” Possible strategies to increase the pediatric mental health workforce may include improving reimbursement and integrating mental health care into primary care and schools by expanding telehealth services.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential misclassification of demographics or cause of death, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the inability to assess actual use of mental health services or firearm ownership in a household, and the possible differences between county-level associations and those of a city, neighborhood, or individual.

However, the results indicate that mental health professional workforce shortages were associated with increased youth suicide rates, and the data may inform local-level suicide prevention efforts, they concluded.

Data support the need for early intervention

“It was very important to conduct this study at this time because mental health problems, to include suicidal ideation, continue to increase in adolescents,” Peter L. Loper Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview. “This study reinforces the immense import of sufficient mental health workforce to mitigate this increasing risk of suicide in adolescents.”

Dr. Loper said: “I believe that early intervention, or consistent access to mental health services, can go a very long way in preventing suicide in adolescents.

“I think the primary implications of this study are more relevant at the systems level, and reinforce the necessity of clinicians advocating for policies that address mental health workforce shortages in counties that are underserved,” he added.

However, “One primary barrier to increasing the number of mental health professionals at a local level, and specifically the number of child psychiatrists, is that demand is currently outpacing supply,” said Dr. Loper, a pediatrician and psychiatrist who was not involved in the study. “As the study authors cite, increasing telepsychiatry services and increasing mental health workforce specifically in the primary care setting may help offset these deficiencies,” he noted. Looking ahead, primary prevention of mental health problems by grassroots efforts is vital to stopping the trend in increased youth suicides and more mental health professionals are needed to mitigate the phenomenon of isolation and the degradation of community constructs.

As for additional research, Dr. Loper agreed with the study authors comments on the need for “more granular data” to better understand the correlation between mental health workforce and suicide in adolescents. “Data that captures city or neighborhood statistics related to mental health workforce and adolescent suicide could go a long way in our efforts to continue to better understand this very important correlation.”

The study was supported by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigator Award. Dr. Hoffmann disclosed research funding from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality unrelated to the current study. Dr. Loper had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

AAP issues guidelines to combat rise in respiratory illness

Updated guidance from the group outlines measures to optimize resources to manage a surge of patients filling hospital beds, emergency departments, and physicians’ practices.

A separate document from the AAP endorses giving extra doses of palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody used to prevent severe infection in infants at high risk of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), as long as the illness is prevalent in the community.

Upticks in rates of RSV and influenza, along with a crisis in children’s mental health, prompted the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association to petition the Biden administration on Nov. 14 to declare an emergency. Such a move would free up extra funding and waivers to allow physicians and hospitals to pool resources, the organizations said.

Despite those challenges, the AAP stressed in its new guidance that routine care, such as immunizations and chronic disease management, “cannot be neglected.”

Shifting resources

Officials at some children’s hospitals said that they have already implemented many of the AAP’s recommended measures for providing care during a surge, such as cross-training staff who usually treat adults, expanding telehealth and urgent care, and optimizing the use of ancillary care spaces.

“A lot of this is just reinforcing the things that I think children’s hospitals have been doing,” Lindsay Ragsdale, MD, chief medical officer for Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, said. “Can we shift adults around? Can we use an adult unit? Can we use an occupied space creatively? We’re really thinking outside the box.”

Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said large children’s hospitals have been actively sharing practices for handling a surge through various channels, but the new guidance could be a useful “checklist” for small hospitals and physician practices that lack well-developed plans.

The AAP’s suggestions for pediatricians in outpatient settings include stocking up on personal protective equipment, using social media and office staff to increase communication with families, and keeping abreast of wait times at local emergency departments.

Addressing a subset of kids

In updated guidance for palivizumab, the AAP noted that earlier-than-usual circulation of RSV prompted pediatricians in some areas to begin administering the drug in the summer and early fall.

Palivizumab is typically given in five consecutive monthly intramuscular injections during RSV season, starting in November. Eligible infants and young children include those born prematurely or who have conditions such as chronic lung disease, hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, or a suppressed immune system.

The AAP said it supports giving extra doses if RSV activity “persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter.” Published studies are sparse but contain “no evidence of increased frequency or severity of adverse events with later doses in a five-dose series nor with doses beyond five doses,” the group added.

The guidance may encourage payers to pick up the tab for extra doses, which are priced at more than $1,800 for cash customers, Dr. Pavia said. However, that recommendation addresses “a pretty small part of the problem overall because the injections are used for a very small subset of kids who are at the highest risk, and more than 80% of hospitalizations for RSV are among healthy kids,” he added.

Dr. Ragsdale and Dr. Pavia have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance from the group outlines measures to optimize resources to manage a surge of patients filling hospital beds, emergency departments, and physicians’ practices.

A separate document from the AAP endorses giving extra doses of palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody used to prevent severe infection in infants at high risk of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), as long as the illness is prevalent in the community.

Upticks in rates of RSV and influenza, along with a crisis in children’s mental health, prompted the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association to petition the Biden administration on Nov. 14 to declare an emergency. Such a move would free up extra funding and waivers to allow physicians and hospitals to pool resources, the organizations said.

Despite those challenges, the AAP stressed in its new guidance that routine care, such as immunizations and chronic disease management, “cannot be neglected.”

Shifting resources

Officials at some children’s hospitals said that they have already implemented many of the AAP’s recommended measures for providing care during a surge, such as cross-training staff who usually treat adults, expanding telehealth and urgent care, and optimizing the use of ancillary care spaces.

“A lot of this is just reinforcing the things that I think children’s hospitals have been doing,” Lindsay Ragsdale, MD, chief medical officer for Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, said. “Can we shift adults around? Can we use an adult unit? Can we use an occupied space creatively? We’re really thinking outside the box.”

Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said large children’s hospitals have been actively sharing practices for handling a surge through various channels, but the new guidance could be a useful “checklist” for small hospitals and physician practices that lack well-developed plans.

The AAP’s suggestions for pediatricians in outpatient settings include stocking up on personal protective equipment, using social media and office staff to increase communication with families, and keeping abreast of wait times at local emergency departments.

Addressing a subset of kids

In updated guidance for palivizumab, the AAP noted that earlier-than-usual circulation of RSV prompted pediatricians in some areas to begin administering the drug in the summer and early fall.

Palivizumab is typically given in five consecutive monthly intramuscular injections during RSV season, starting in November. Eligible infants and young children include those born prematurely or who have conditions such as chronic lung disease, hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, or a suppressed immune system.

The AAP said it supports giving extra doses if RSV activity “persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter.” Published studies are sparse but contain “no evidence of increased frequency or severity of adverse events with later doses in a five-dose series nor with doses beyond five doses,” the group added.

The guidance may encourage payers to pick up the tab for extra doses, which are priced at more than $1,800 for cash customers, Dr. Pavia said. However, that recommendation addresses “a pretty small part of the problem overall because the injections are used for a very small subset of kids who are at the highest risk, and more than 80% of hospitalizations for RSV are among healthy kids,” he added.

Dr. Ragsdale and Dr. Pavia have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance from the group outlines measures to optimize resources to manage a surge of patients filling hospital beds, emergency departments, and physicians’ practices.

A separate document from the AAP endorses giving extra doses of palivizumab, a monoclonal antibody used to prevent severe infection in infants at high risk of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), as long as the illness is prevalent in the community.

Upticks in rates of RSV and influenza, along with a crisis in children’s mental health, prompted the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association to petition the Biden administration on Nov. 14 to declare an emergency. Such a move would free up extra funding and waivers to allow physicians and hospitals to pool resources, the organizations said.

Despite those challenges, the AAP stressed in its new guidance that routine care, such as immunizations and chronic disease management, “cannot be neglected.”

Shifting resources

Officials at some children’s hospitals said that they have already implemented many of the AAP’s recommended measures for providing care during a surge, such as cross-training staff who usually treat adults, expanding telehealth and urgent care, and optimizing the use of ancillary care spaces.

“A lot of this is just reinforcing the things that I think children’s hospitals have been doing,” Lindsay Ragsdale, MD, chief medical officer for Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Lexington, said. “Can we shift adults around? Can we use an adult unit? Can we use an occupied space creatively? We’re really thinking outside the box.”

Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, said large children’s hospitals have been actively sharing practices for handling a surge through various channels, but the new guidance could be a useful “checklist” for small hospitals and physician practices that lack well-developed plans.

The AAP’s suggestions for pediatricians in outpatient settings include stocking up on personal protective equipment, using social media and office staff to increase communication with families, and keeping abreast of wait times at local emergency departments.

Addressing a subset of kids

In updated guidance for palivizumab, the AAP noted that earlier-than-usual circulation of RSV prompted pediatricians in some areas to begin administering the drug in the summer and early fall.

Palivizumab is typically given in five consecutive monthly intramuscular injections during RSV season, starting in November. Eligible infants and young children include those born prematurely or who have conditions such as chronic lung disease, hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, or a suppressed immune system.

The AAP said it supports giving extra doses if RSV activity “persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter.” Published studies are sparse but contain “no evidence of increased frequency or severity of adverse events with later doses in a five-dose series nor with doses beyond five doses,” the group added.

The guidance may encourage payers to pick up the tab for extra doses, which are priced at more than $1,800 for cash customers, Dr. Pavia said. However, that recommendation addresses “a pretty small part of the problem overall because the injections are used for a very small subset of kids who are at the highest risk, and more than 80% of hospitalizations for RSV are among healthy kids,” he added.

Dr. Ragsdale and Dr. Pavia have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children with autism show distinct brain features related to motor impairment

Previous research suggests that individuals with ASD overlap in motor impairment with those with DCD. But these two conditions may differ significantly in some areas, as children with ASD tend to show weaker skills in social motor tasks such as imitation, wrote Emil Kilroy, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

The neurobiological basis of autism remains unknown, despite many research efforts, in part because of the heterogeneity of the disease, said corresponding author Lisa Aziz-Zadeh, PhD, also of the University of Southern California, in an interview.

Comorbidity with other disorders is a strong contributing factor to heterogeneity, and approximately 80% of autistic individuals have motor impairments and meet criteria for a diagnosis of DCD, said Dr. Aziz-Zadeh. “Controlling for other comorbidities, such as developmental coordination disorder, when trying to understand the neural basis of autism is important, so that we can understand which neural circuits are related to [core symptoms of autism] and which ones are related to motor impairments that are comorbid with autism, but not necessarily part of the core symptomology,” she explained. “We focused on white matter pathways here because many researchers now think the underlying basis of autism, besides genetics, is brain connectivity differences.”

In their study published in Scientific Reports, the researchers reviewed data from whole-brain correlational tractography for 22 individuals with autism spectrum disorder, 16 with developmental coordination disorder, and 21 normally developing individuals, who served as the control group. The mean age of the participants was approximately 11 years; the age range was 8-17 years.

Overall, patterns of brain diffusion (movement of fluid, mainly water molecules, in the brain) were significantly different in ASD children, compared with typically developing children.

The ASD group showed significantly reduced diffusivity in the bilateral fronto-parietal cingulum and the left parolfactory cingulum. This finding reflects previous studies suggesting an association between brain patterns in the cingulum area and ASD. But the current study is “the first to identify the fronto-parietal and the parolfactory portions of the cingulum as well as the anterior caudal u-fibers as specific to core ASD symptomatology and not related to motor-related comorbidity,” the researchers wrote.

Differences in brain diffusivity were associated with worse performance on motor skills and behavioral measures for children with ASD and children with DCD, compared with controls.

Motor development was assessed using the Total Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 (MABC-2) and the Florida Apraxia Battery modified for children (FAB-M). The MABC-2 is among the most common tools for measuring motor skills and identifying clinically relevant motor deficits in children and teens aged 3-16 years. The test includes three subtest scores (manual dexterity, gross-motor aiming and catching, and balance) and a total score. Scores are based on a child’s best performance on each component, and higher scores indicate better functioning. In the new study, The MABC-2 total scores averaged 10.57 for controls, compared with 5.76 in the ASD group, and 4.31 in the DCD group.

Children with ASD differed from the other groups in social measures. Social skills were measured using several tools, including the Social Responsivity Scale (SRS Total), which is a parent-completed survey that includes a total score designed to reflect the severity of social deficits in ASD. It is divided into five subscales for parents to assess a child’s social skill impairment: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and mannerisms. Scores for the SRS are calculated in T-scores, in which a score of 50 represents the mean. T-scores of 59 and below are generally not associated with ASD, and patients with these scores are considered to have low to no symptomatology. Scores on the SRS Total in the new study were 45.95, 77.45, and 55.81 for the controls, ASD group, and DCD group, respectively.

Results should raise awareness

“The results were largely predicted in our hypotheses – that we would find specific white matter pathways in autism that would differ from [what we saw in typically developing patients and those with DCD], and that diffusivity in ASD would be related to socioemotional differences,” Dr. Aziz-Zadeh said, in an interview.

“What was surprising was that some pathways that had previously been thought to be different in autism were also compromised in DCD, indicating that they were common to motor deficits which both groups shared, not to core autism symptomology,” she noted.

A message for clinicians from the study is that a dual diagnosis of DCD is often missing in ASD practice, said Dr. Aziz-Zadeh. “Given that approximately 80% of children with ASD have DCD, testing for DCD and addressing potential motor issues should be more common practice,” she said.

Dr. Aziz-Zadeh and colleagues are now investigating relationships between the brain, behavior, and the gut microbiome. “We think that understanding autism from a full-body perspective, examining interactions between the brain and the body, will be an important step in this field,” she emphasized.

The study was limited by several factors, including the small sample size, the use of only right-handed participants, and the use of self-reports by children and parents, the researchers noted. Additionally, they noted that white matter develops at different rates in different age groups, and future studies might consider age as a factor, as well as further behavioral assessments, they said.

Small sample size limits conclusions

“Understanding the neuroanatomic differences that may contribute to the core symptoms of ASD is a very important goal for the field, particularly how they relate to other comorbid symptoms and neurodevelopmental disorders,” said Michael Gandal, MD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a member of the Lifespan Brain Institute at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, in an interview.

“While this study provides some clues into how structural connectivity may relate to motor coordination in ASD, it will be important to replicate these findings in a much larger sample before we can really appreciate how robust these findings are and how well they generalize to the broader ASD population,” Dr. Gandal emphasized.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gandal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Previous research suggests that individuals with ASD overlap in motor impairment with those with DCD. But these two conditions may differ significantly in some areas, as children with ASD tend to show weaker skills in social motor tasks such as imitation, wrote Emil Kilroy, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

The neurobiological basis of autism remains unknown, despite many research efforts, in part because of the heterogeneity of the disease, said corresponding author Lisa Aziz-Zadeh, PhD, also of the University of Southern California, in an interview.

Comorbidity with other disorders is a strong contributing factor to heterogeneity, and approximately 80% of autistic individuals have motor impairments and meet criteria for a diagnosis of DCD, said Dr. Aziz-Zadeh. “Controlling for other comorbidities, such as developmental coordination disorder, when trying to understand the neural basis of autism is important, so that we can understand which neural circuits are related to [core symptoms of autism] and which ones are related to motor impairments that are comorbid with autism, but not necessarily part of the core symptomology,” she explained. “We focused on white matter pathways here because many researchers now think the underlying basis of autism, besides genetics, is brain connectivity differences.”

In their study published in Scientific Reports, the researchers reviewed data from whole-brain correlational tractography for 22 individuals with autism spectrum disorder, 16 with developmental coordination disorder, and 21 normally developing individuals, who served as the control group. The mean age of the participants was approximately 11 years; the age range was 8-17 years.

Overall, patterns of brain diffusion (movement of fluid, mainly water molecules, in the brain) were significantly different in ASD children, compared with typically developing children.

The ASD group showed significantly reduced diffusivity in the bilateral fronto-parietal cingulum and the left parolfactory cingulum. This finding reflects previous studies suggesting an association between brain patterns in the cingulum area and ASD. But the current study is “the first to identify the fronto-parietal and the parolfactory portions of the cingulum as well as the anterior caudal u-fibers as specific to core ASD symptomatology and not related to motor-related comorbidity,” the researchers wrote.

Differences in brain diffusivity were associated with worse performance on motor skills and behavioral measures for children with ASD and children with DCD, compared with controls.

Motor development was assessed using the Total Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 (MABC-2) and the Florida Apraxia Battery modified for children (FAB-M). The MABC-2 is among the most common tools for measuring motor skills and identifying clinically relevant motor deficits in children and teens aged 3-16 years. The test includes three subtest scores (manual dexterity, gross-motor aiming and catching, and balance) and a total score. Scores are based on a child’s best performance on each component, and higher scores indicate better functioning. In the new study, The MABC-2 total scores averaged 10.57 for controls, compared with 5.76 in the ASD group, and 4.31 in the DCD group.

Children with ASD differed from the other groups in social measures. Social skills were measured using several tools, including the Social Responsivity Scale (SRS Total), which is a parent-completed survey that includes a total score designed to reflect the severity of social deficits in ASD. It is divided into five subscales for parents to assess a child’s social skill impairment: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and mannerisms. Scores for the SRS are calculated in T-scores, in which a score of 50 represents the mean. T-scores of 59 and below are generally not associated with ASD, and patients with these scores are considered to have low to no symptomatology. Scores on the SRS Total in the new study were 45.95, 77.45, and 55.81 for the controls, ASD group, and DCD group, respectively.

Results should raise awareness

“The results were largely predicted in our hypotheses – that we would find specific white matter pathways in autism that would differ from [what we saw in typically developing patients and those with DCD], and that diffusivity in ASD would be related to socioemotional differences,” Dr. Aziz-Zadeh said, in an interview.

“What was surprising was that some pathways that had previously been thought to be different in autism were also compromised in DCD, indicating that they were common to motor deficits which both groups shared, not to core autism symptomology,” she noted.

A message for clinicians from the study is that a dual diagnosis of DCD is often missing in ASD practice, said Dr. Aziz-Zadeh. “Given that approximately 80% of children with ASD have DCD, testing for DCD and addressing potential motor issues should be more common practice,” she said.

Dr. Aziz-Zadeh and colleagues are now investigating relationships between the brain, behavior, and the gut microbiome. “We think that understanding autism from a full-body perspective, examining interactions between the brain and the body, will be an important step in this field,” she emphasized.

The study was limited by several factors, including the small sample size, the use of only right-handed participants, and the use of self-reports by children and parents, the researchers noted. Additionally, they noted that white matter develops at different rates in different age groups, and future studies might consider age as a factor, as well as further behavioral assessments, they said.

Small sample size limits conclusions

“Understanding the neuroanatomic differences that may contribute to the core symptoms of ASD is a very important goal for the field, particularly how they relate to other comorbid symptoms and neurodevelopmental disorders,” said Michael Gandal, MD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a member of the Lifespan Brain Institute at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, in an interview.

“While this study provides some clues into how structural connectivity may relate to motor coordination in ASD, it will be important to replicate these findings in a much larger sample before we can really appreciate how robust these findings are and how well they generalize to the broader ASD population,” Dr. Gandal emphasized.

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gandal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Previous research suggests that individuals with ASD overlap in motor impairment with those with DCD. But these two conditions may differ significantly in some areas, as children with ASD tend to show weaker skills in social motor tasks such as imitation, wrote Emil Kilroy, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

The neurobiological basis of autism remains unknown, despite many research efforts, in part because of the heterogeneity of the disease, said corresponding author Lisa Aziz-Zadeh, PhD, also of the University of Southern California, in an interview.

Comorbidity with other disorders is a strong contributing factor to heterogeneity, and approximately 80% of autistic individuals have motor impairments and meet criteria for a diagnosis of DCD, said Dr. Aziz-Zadeh. “Controlling for other comorbidities, such as developmental coordination disorder, when trying to understand the neural basis of autism is important, so that we can understand which neural circuits are related to [core symptoms of autism] and which ones are related to motor impairments that are comorbid with autism, but not necessarily part of the core symptomology,” she explained. “We focused on white matter pathways here because many researchers now think the underlying basis of autism, besides genetics, is brain connectivity differences.”

In their study published in Scientific Reports, the researchers reviewed data from whole-brain correlational tractography for 22 individuals with autism spectrum disorder, 16 with developmental coordination disorder, and 21 normally developing individuals, who served as the control group. The mean age of the participants was approximately 11 years; the age range was 8-17 years.

Overall, patterns of brain diffusion (movement of fluid, mainly water molecules, in the brain) were significantly different in ASD children, compared with typically developing children.

The ASD group showed significantly reduced diffusivity in the bilateral fronto-parietal cingulum and the left parolfactory cingulum. This finding reflects previous studies suggesting an association between brain patterns in the cingulum area and ASD. But the current study is “the first to identify the fronto-parietal and the parolfactory portions of the cingulum as well as the anterior caudal u-fibers as specific to core ASD symptomatology and not related to motor-related comorbidity,” the researchers wrote.

Differences in brain diffusivity were associated with worse performance on motor skills and behavioral measures for children with ASD and children with DCD, compared with controls.