User login

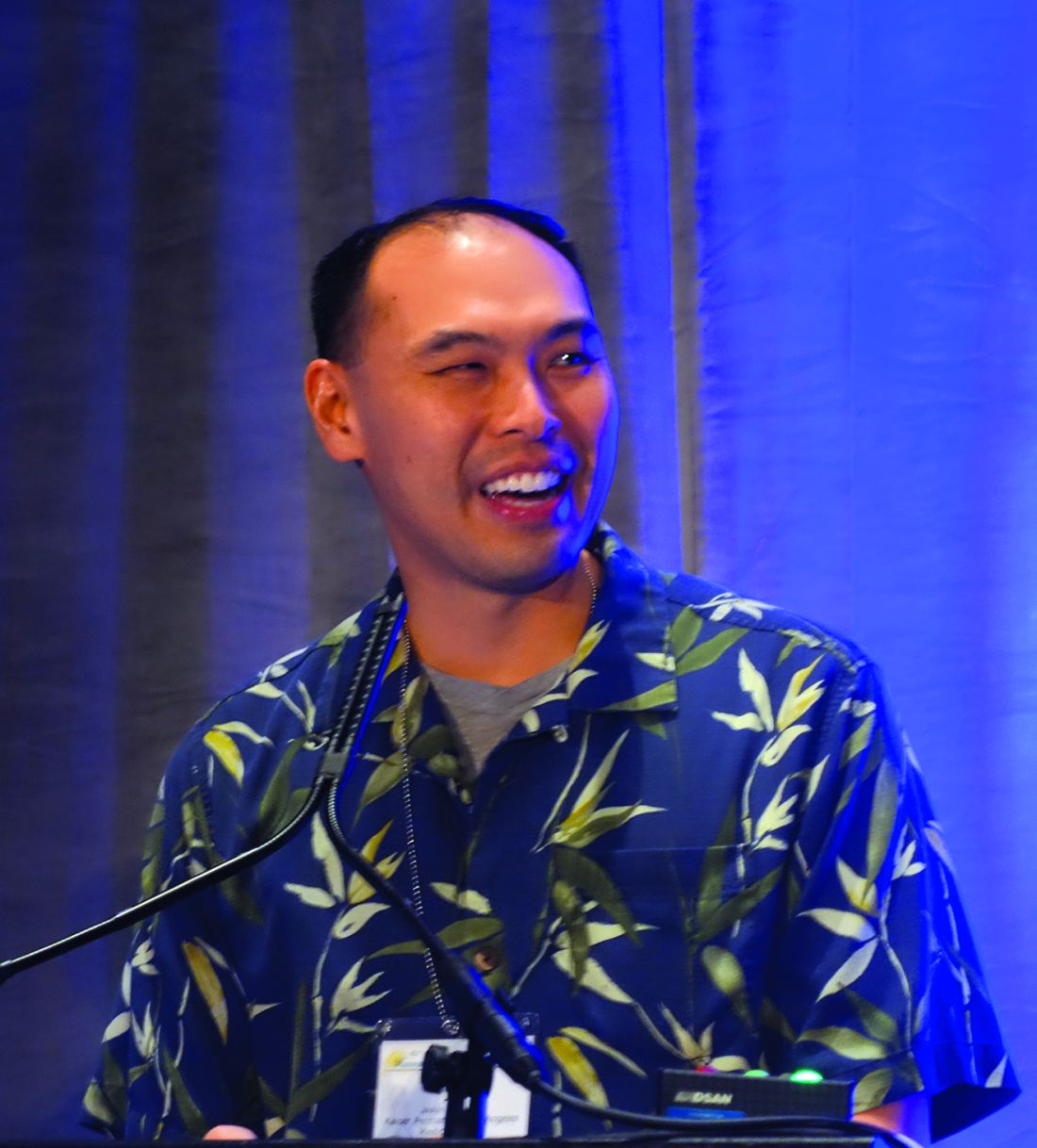

Postpartum care: State scorecard for Medicaid enrollees

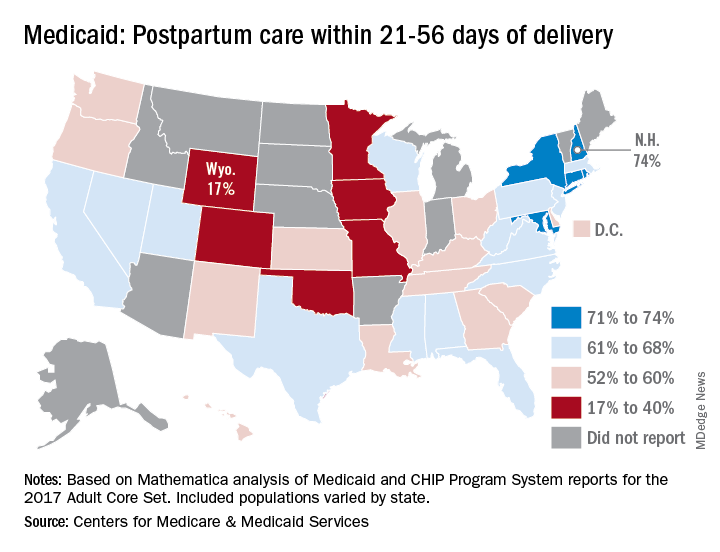

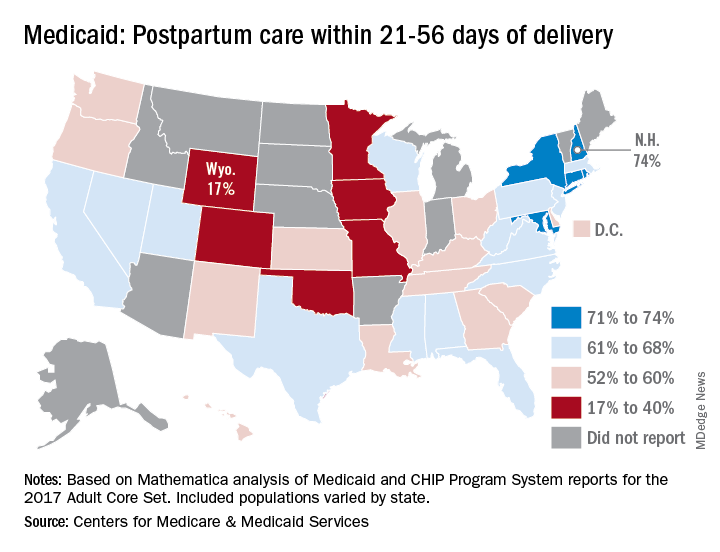

Timely postpartum care for Medicaid enrollees varies considerably, ranging from 17% to 74% among the states, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

A national median of 60% of women saw a health care provider within 21-56 days of their delivery, CMS reported in its Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Scorecard.

“Medicaid is the largest payer for maternity care in the United States. The program has an important role to play in improving maternal and perinatal health outcomes,” the CMS noted.

New Hampshire’s rate of 74% was the highest of any state, just edging out Maryland and Rhode Island, each at 73%. The only other states over 70% were Connecticut and New York, which both reported rates of 71%, scorecard data show.

In Wyoming, the state with the lowest rate, 17% of Medicaid enrollees received timely postpartum care. The other four states with rates below 40% were Oklahoma (22%), Colorado (35%), Iowa (37%), and Missouri (38%), the CMS said after a recent refresh of data in the scorecard.

“The included populations … can vary by state. For example, some states report data on certain populations such as those covered under managed care but not those covered under fee for service. This variation in data and calculation methods can affect measure performance and comparisons between states,” the CMS said.

The scorecard is based on Mathematica analysis of Medicaid and CHIP Program System reports for the 2017 Adult Core Set, and the measurement period was Nov. 6, 2015, to Nov. 5, 2016. Twelve states did not report data on postpartum care to the CMS.

“More and more states are voluntarily reporting their health outcomes in the scorecard, and the new data is leading us into an era of increased transparency and accountability, so that together we can improve the quality of care we give to the vulnerable Americans that depend on this vital program,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

Timely postpartum care for Medicaid enrollees varies considerably, ranging from 17% to 74% among the states, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

A national median of 60% of women saw a health care provider within 21-56 days of their delivery, CMS reported in its Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Scorecard.

“Medicaid is the largest payer for maternity care in the United States. The program has an important role to play in improving maternal and perinatal health outcomes,” the CMS noted.

New Hampshire’s rate of 74% was the highest of any state, just edging out Maryland and Rhode Island, each at 73%. The only other states over 70% were Connecticut and New York, which both reported rates of 71%, scorecard data show.

In Wyoming, the state with the lowest rate, 17% of Medicaid enrollees received timely postpartum care. The other four states with rates below 40% were Oklahoma (22%), Colorado (35%), Iowa (37%), and Missouri (38%), the CMS said after a recent refresh of data in the scorecard.

“The included populations … can vary by state. For example, some states report data on certain populations such as those covered under managed care but not those covered under fee for service. This variation in data and calculation methods can affect measure performance and comparisons between states,” the CMS said.

The scorecard is based on Mathematica analysis of Medicaid and CHIP Program System reports for the 2017 Adult Core Set, and the measurement period was Nov. 6, 2015, to Nov. 5, 2016. Twelve states did not report data on postpartum care to the CMS.

“More and more states are voluntarily reporting their health outcomes in the scorecard, and the new data is leading us into an era of increased transparency and accountability, so that together we can improve the quality of care we give to the vulnerable Americans that depend on this vital program,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

Timely postpartum care for Medicaid enrollees varies considerably, ranging from 17% to 74% among the states, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

A national median of 60% of women saw a health care provider within 21-56 days of their delivery, CMS reported in its Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Scorecard.

“Medicaid is the largest payer for maternity care in the United States. The program has an important role to play in improving maternal and perinatal health outcomes,” the CMS noted.

New Hampshire’s rate of 74% was the highest of any state, just edging out Maryland and Rhode Island, each at 73%. The only other states over 70% were Connecticut and New York, which both reported rates of 71%, scorecard data show.

In Wyoming, the state with the lowest rate, 17% of Medicaid enrollees received timely postpartum care. The other four states with rates below 40% were Oklahoma (22%), Colorado (35%), Iowa (37%), and Missouri (38%), the CMS said after a recent refresh of data in the scorecard.

“The included populations … can vary by state. For example, some states report data on certain populations such as those covered under managed care but not those covered under fee for service. This variation in data and calculation methods can affect measure performance and comparisons between states,” the CMS said.

The scorecard is based on Mathematica analysis of Medicaid and CHIP Program System reports for the 2017 Adult Core Set, and the measurement period was Nov. 6, 2015, to Nov. 5, 2016. Twelve states did not report data on postpartum care to the CMS.

“More and more states are voluntarily reporting their health outcomes in the scorecard, and the new data is leading us into an era of increased transparency and accountability, so that together we can improve the quality of care we give to the vulnerable Americans that depend on this vital program,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

USPSTF updates, reaffirms recommendation for HBV screening in pregnant women

The according to task force member Douglas K. Owens, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System and other members of the task force.

The recommendation statement, published in JAMA, was based on an evidence report and systematic review also published in JAMA. In that review, two studies of fair quality were identified; one included 155,081 infants born to HBV-positive women identified for case management through the national Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program from 1994 to 2008, and the other included 4,446 infants born in a large, regional health care organization in the United States between 1997 and 2010. In both, low rates of perinatal transmission were reported for those periods – between 0.5% and 1.9% – with the rate falling over time.

In the 2009 recommendation, the USPSTF found adequate evidence that serologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen accurately identifies HBV infection, and that interventions were effective in preventing perinatal transmission. That recommendation has been reaffirmed in the current update, with HBV screening receiving a grade of A, which is the strongest the USPSTF offers.

In a related editorial, Neil S. Silverman, MD, of the Center for Fetal Medicine and Women’s Ultrasound in Los Angeles noted several improvements in maternal HBV therapy since the publication of the original 2009 recommendation, including maternal HBV-targeted antiviral therapy during pregnancy as an adjunct to neonatal immunoprophylaxis and the ability to refer women for chronic treatment of their HBV disease to prevent long-term infection complications. The task forces also noted that HBV screening of all pregnant women is mandated by law in 26 states.

One member of the task force reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Healthwise, another member reported receiving personal fees from UpToDate; a third reported participating in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ Hepatitis B Guidance and Hepatitis B Systematic Review Group. The evidence and review study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Silverman reported no disclosures.

SOURCes: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9365; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):360-2; Silverman NS. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):312-14.

The according to task force member Douglas K. Owens, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System and other members of the task force.

The recommendation statement, published in JAMA, was based on an evidence report and systematic review also published in JAMA. In that review, two studies of fair quality were identified; one included 155,081 infants born to HBV-positive women identified for case management through the national Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program from 1994 to 2008, and the other included 4,446 infants born in a large, regional health care organization in the United States between 1997 and 2010. In both, low rates of perinatal transmission were reported for those periods – between 0.5% and 1.9% – with the rate falling over time.

In the 2009 recommendation, the USPSTF found adequate evidence that serologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen accurately identifies HBV infection, and that interventions were effective in preventing perinatal transmission. That recommendation has been reaffirmed in the current update, with HBV screening receiving a grade of A, which is the strongest the USPSTF offers.

In a related editorial, Neil S. Silverman, MD, of the Center for Fetal Medicine and Women’s Ultrasound in Los Angeles noted several improvements in maternal HBV therapy since the publication of the original 2009 recommendation, including maternal HBV-targeted antiviral therapy during pregnancy as an adjunct to neonatal immunoprophylaxis and the ability to refer women for chronic treatment of their HBV disease to prevent long-term infection complications. The task forces also noted that HBV screening of all pregnant women is mandated by law in 26 states.

One member of the task force reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Healthwise, another member reported receiving personal fees from UpToDate; a third reported participating in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ Hepatitis B Guidance and Hepatitis B Systematic Review Group. The evidence and review study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Silverman reported no disclosures.

SOURCes: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9365; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):360-2; Silverman NS. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):312-14.

The according to task force member Douglas K. Owens, MD, of the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto (Calif.) Health Care System and other members of the task force.

The recommendation statement, published in JAMA, was based on an evidence report and systematic review also published in JAMA. In that review, two studies of fair quality were identified; one included 155,081 infants born to HBV-positive women identified for case management through the national Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Program from 1994 to 2008, and the other included 4,446 infants born in a large, regional health care organization in the United States between 1997 and 2010. In both, low rates of perinatal transmission were reported for those periods – between 0.5% and 1.9% – with the rate falling over time.

In the 2009 recommendation, the USPSTF found adequate evidence that serologic testing for hepatitis B surface antigen accurately identifies HBV infection, and that interventions were effective in preventing perinatal transmission. That recommendation has been reaffirmed in the current update, with HBV screening receiving a grade of A, which is the strongest the USPSTF offers.

In a related editorial, Neil S. Silverman, MD, of the Center for Fetal Medicine and Women’s Ultrasound in Los Angeles noted several improvements in maternal HBV therapy since the publication of the original 2009 recommendation, including maternal HBV-targeted antiviral therapy during pregnancy as an adjunct to neonatal immunoprophylaxis and the ability to refer women for chronic treatment of their HBV disease to prevent long-term infection complications. The task forces also noted that HBV screening of all pregnant women is mandated by law in 26 states.

One member of the task force reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Healthwise, another member reported receiving personal fees from UpToDate; a third reported participating in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases’ Hepatitis B Guidance and Hepatitis B Systematic Review Group. The evidence and review study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Silverman reported no disclosures.

SOURCes: Owens DK et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9365; Henderson JT et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):360-2; Silverman NS. JAMA. 2019 Jul 23;32(4):312-14.

FROM JAMA

Clinics get more time on Title X changes

Family planning clinics will have more time to comply with a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and bars them from referring women for the procedures.

The Department of Health & Human Services does not intend to bring enforcement actions against taxpayer-funded clinics if they are making good-faith efforts to comply with the new rules, according to a memo issued July 20. Such good faith efforts include a written assurance by Aug. 19 that clinics are not providing abortions nor including abortion in their family planning methods, according to the emailed guidance sent by Diane Foley, MD, HHS Deputy Assistant Secretary at the Office of Population Affairs (OPA). Clinics must also detail an action plan describing the steps they will take to comply with the Title X changes and start those actions immediately, according to the memo, obtained by this news organization.

“In the past, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, has exercised enforcement discretion in appropriate circumstances,” according to the memo. “Given the circumstances surrounding the implementation of the final rule, OPA does not intend to bring enforcement actions against Title X recipients that are making, and continue to make, good-faith efforts to comply with the final rule. OPA is committed to working with grantees to assist them in coming into compliance with the requirements of the final rule.”

The decision comes a week after HHS warned family planning clinics that receive federal money to immediately stop providing referrals and counseling on abortion or face revocation of funding. An email from HHS on July 15 stated that the agency was requiring immediate compliance of the Title X changes consistent with recent court rulings. The warning came just before the start of a national Title X grantee meeting held in Washington.

The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income individuals. Under the rule, the government will withdraw financial assistance to clinics if they allow counseling or referrals associated with abortion, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services. The rule also imposes physical separation requirements for health centers that offer abortions.

More than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

In the July 20 memo, Dr. Foley wrote that, in addition to the Aug. 19 requirements, clinics must send written confirmation by Sep. 18 outlining the steps taken to comply with the Title X changes and provide any relevant documentation needed for HHS to verify the compliance. By March 4, 2020, a written statement must be submitted affirming the clinic is in compliance with the requirement for physical separation between Title X services and abortion services.

The National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, a plaintiff in one of the challenges, called the administration’s July 20 memo “wholly insufficient” and said the clinics need more guidance about how to move forward with the rule changes.

“It’s just absurd to think that a few bullet points amount to guidance,” association officials said in a July 21 statement. “We urge [the agency] to take the time to properly expand on and better describe how it will interpret aspects of the rule – using examples that reflect the wide range of provider settings and administrative structures present in Title X. Once again, [the agency] falls far short of linking the rule to day-to-day practice, leaving the entire family planning network in the dark on how they need to operate to stay in the program.”

At presstime, HHS had not responded to a message seeking comment on the requirements. In her note, Dr. Foley wrote that more guidance on the changes were forthcoming and that grantees unable to meet the required time line may request a deadline extension from the agency.

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.”

Family planning clinics will have more time to comply with a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and bars them from referring women for the procedures.

The Department of Health & Human Services does not intend to bring enforcement actions against taxpayer-funded clinics if they are making good-faith efforts to comply with the new rules, according to a memo issued July 20. Such good faith efforts include a written assurance by Aug. 19 that clinics are not providing abortions nor including abortion in their family planning methods, according to the emailed guidance sent by Diane Foley, MD, HHS Deputy Assistant Secretary at the Office of Population Affairs (OPA). Clinics must also detail an action plan describing the steps they will take to comply with the Title X changes and start those actions immediately, according to the memo, obtained by this news organization.

“In the past, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, has exercised enforcement discretion in appropriate circumstances,” according to the memo. “Given the circumstances surrounding the implementation of the final rule, OPA does not intend to bring enforcement actions against Title X recipients that are making, and continue to make, good-faith efforts to comply with the final rule. OPA is committed to working with grantees to assist them in coming into compliance with the requirements of the final rule.”

The decision comes a week after HHS warned family planning clinics that receive federal money to immediately stop providing referrals and counseling on abortion or face revocation of funding. An email from HHS on July 15 stated that the agency was requiring immediate compliance of the Title X changes consistent with recent court rulings. The warning came just before the start of a national Title X grantee meeting held in Washington.

The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income individuals. Under the rule, the government will withdraw financial assistance to clinics if they allow counseling or referrals associated with abortion, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services. The rule also imposes physical separation requirements for health centers that offer abortions.

More than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

In the July 20 memo, Dr. Foley wrote that, in addition to the Aug. 19 requirements, clinics must send written confirmation by Sep. 18 outlining the steps taken to comply with the Title X changes and provide any relevant documentation needed for HHS to verify the compliance. By March 4, 2020, a written statement must be submitted affirming the clinic is in compliance with the requirement for physical separation between Title X services and abortion services.

The National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, a plaintiff in one of the challenges, called the administration’s July 20 memo “wholly insufficient” and said the clinics need more guidance about how to move forward with the rule changes.

“It’s just absurd to think that a few bullet points amount to guidance,” association officials said in a July 21 statement. “We urge [the agency] to take the time to properly expand on and better describe how it will interpret aspects of the rule – using examples that reflect the wide range of provider settings and administrative structures present in Title X. Once again, [the agency] falls far short of linking the rule to day-to-day practice, leaving the entire family planning network in the dark on how they need to operate to stay in the program.”

At presstime, HHS had not responded to a message seeking comment on the requirements. In her note, Dr. Foley wrote that more guidance on the changes were forthcoming and that grantees unable to meet the required time line may request a deadline extension from the agency.

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.”

Family planning clinics will have more time to comply with a Trump administration rule that prohibits physicians from counseling patients about abortion and bars them from referring women for the procedures.

The Department of Health & Human Services does not intend to bring enforcement actions against taxpayer-funded clinics if they are making good-faith efforts to comply with the new rules, according to a memo issued July 20. Such good faith efforts include a written assurance by Aug. 19 that clinics are not providing abortions nor including abortion in their family planning methods, according to the emailed guidance sent by Diane Foley, MD, HHS Deputy Assistant Secretary at the Office of Population Affairs (OPA). Clinics must also detail an action plan describing the steps they will take to comply with the Title X changes and start those actions immediately, according to the memo, obtained by this news organization.

“In the past, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, has exercised enforcement discretion in appropriate circumstances,” according to the memo. “Given the circumstances surrounding the implementation of the final rule, OPA does not intend to bring enforcement actions against Title X recipients that are making, and continue to make, good-faith efforts to comply with the final rule. OPA is committed to working with grantees to assist them in coming into compliance with the requirements of the final rule.”

The decision comes a week after HHS warned family planning clinics that receive federal money to immediately stop providing referrals and counseling on abortion or face revocation of funding. An email from HHS on July 15 stated that the agency was requiring immediate compliance of the Title X changes consistent with recent court rulings. The warning came just before the start of a national Title X grantee meeting held in Washington.

The changes to the Title X program make health clinics ineligible for funding if they offer, promote, or support abortion as a method of family planning. Title X grants generally go to health centers that provide reproductive health care – such as STD testing, cancer screenings, and contraception – to low-income individuals. Under the rule, the government will withdraw financial assistance to clinics if they allow counseling or referrals associated with abortion, regardless of whether the money is used for other health care services. The rule also imposes physical separation requirements for health centers that offer abortions.

More than 20 states and several abortion rights organizations sued over the rules in four separate states. District judges in Oregon, Washington, and California temporarily blocked the rules from taking effect. In a June 20 decision, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the federal government may go forward with its plan to restrict Title X funding from clinics that provide abortion counseling or that refer patients for abortion services. The decision overturned the lower court injunctions.

In the July 20 memo, Dr. Foley wrote that, in addition to the Aug. 19 requirements, clinics must send written confirmation by Sep. 18 outlining the steps taken to comply with the Title X changes and provide any relevant documentation needed for HHS to verify the compliance. By March 4, 2020, a written statement must be submitted affirming the clinic is in compliance with the requirement for physical separation between Title X services and abortion services.

The National Family Planning & Reproductive Health Association, a plaintiff in one of the challenges, called the administration’s July 20 memo “wholly insufficient” and said the clinics need more guidance about how to move forward with the rule changes.

“It’s just absurd to think that a few bullet points amount to guidance,” association officials said in a July 21 statement. “We urge [the agency] to take the time to properly expand on and better describe how it will interpret aspects of the rule – using examples that reflect the wide range of provider settings and administrative structures present in Title X. Once again, [the agency] falls far short of linking the rule to day-to-day practice, leaving the entire family planning network in the dark on how they need to operate to stay in the program.”

At presstime, HHS had not responded to a message seeking comment on the requirements. In her note, Dr. Foley wrote that more guidance on the changes were forthcoming and that grantees unable to meet the required time line may request a deadline extension from the agency.

HHS has previously said that the Title X changes ensure that grants and contracts awarded under the program fully comply with the statutory program integrity requirements, “thereby fulfilling the purpose of Title X, so that more women and men can receive services that help them consider and achieve both their short-term and long-term family planning needs.”

New WHO recommendations promote dolutegravir benefits in the face of lowered risk signal for neural tube defects

The risk of neural tube defects linked to dolutegravir exposure during pregnancy is lower than previously signaled, according to new reports that have prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to confirm that this antiviral medication should be the preferred option across all populations.

The use of dolutegravir (DTG) during pregnancy has been a pressing global health question since May 2018, when an unplanned interim analysis of the Tsepamo surveillance study of birth outcomes in Botswana showed four neural tube defects associated with dolutegravir exposure among 426 infants born to HIV-positive women (0.94%).

With follow-up for additional births, however, just one more neural tube defect was identified out of 1,683 deliveries among women who had taken DTG around the time of conception (0.30%), according to a report just presented here at the at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

By comparison, prevalence rates of neural tube defects were 0.10% for mothers taking other antiretroviral therapies at conception, 0.04% for those specifically taking efavirenz at conception, and 0.08% in HIV-uninfected mothers, according to the report, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“While there may be a risk for neural tube defects, this risk is small, and really importantly, needs to be weighed against the large potential benefits of dolutegravir,” investigator Rebecca M. Zash, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said here in Mexico City during an IAS 2019 video press conference.

The WHO had previously sounded a note of caution, saying that DTG could be “considered” in women of childbearing age if other first‐line antiretroviral agents such as efavirenz could not be used.

However, following release of new evidence, including the study by Dr. Zash and colleagues, the WHO has come out with a clear recommendation for HIV drug as “the preferred first-line and second-line treatment for all populations, including pregnant women and those of childbearing potential.”

The updated scientific reports and guidelines have important implications for global health. “Many countries have been working to make dolutegravir-based treatment their preferred first-line regimen, as it’s got several advantages over efavirenz, which people have been using for many years now, including its tolerability and resistance profiles, and its impact on morbidity and mortality,” IAS president Anton Pozniak, MD, said in the press conference.

Some countries paused their plans to roll out dolutegravir-based regimens after the preliminary safety signal from the Tsepamo study was reported, Dr. Pozniak added.

In another study presented at IAS looking at dolutegravir use at conception, investigators described an additional surveillance study in Botswana, conducted independently from the Tsepamo study. One neural tube defect was found among 152 deliveries in mothers who had been taking DTG at conception (0.66%), and two neural tube defects among 2,326 deliveries to HIV-negative mothers (0.09%).

Although the number of deliveries are small in this study, the results suggest a risk of neural tube defects with DTG exposure at conception of less than 1%, said Mmakgomo Mimi Raesima, MD, MPH, public health specialist, Ministry of Health and Wellness, Botswana.

Because neural-tube defects might be related to low folate levels, Dr. Raesima said “conversations are continuing” with regard to folate food fortification in Botswana, a country that does not mandate folate-fortified grains.

“We want to capitalize on the momentum from these results,” Dr. Raesima said in the press conference.

The Tsepamo study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zash reported grants during the conduct of the study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Zash R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905230.

The risk of neural tube defects linked to dolutegravir exposure during pregnancy is lower than previously signaled, according to new reports that have prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to confirm that this antiviral medication should be the preferred option across all populations.

The use of dolutegravir (DTG) during pregnancy has been a pressing global health question since May 2018, when an unplanned interim analysis of the Tsepamo surveillance study of birth outcomes in Botswana showed four neural tube defects associated with dolutegravir exposure among 426 infants born to HIV-positive women (0.94%).

With follow-up for additional births, however, just one more neural tube defect was identified out of 1,683 deliveries among women who had taken DTG around the time of conception (0.30%), according to a report just presented here at the at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

By comparison, prevalence rates of neural tube defects were 0.10% for mothers taking other antiretroviral therapies at conception, 0.04% for those specifically taking efavirenz at conception, and 0.08% in HIV-uninfected mothers, according to the report, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“While there may be a risk for neural tube defects, this risk is small, and really importantly, needs to be weighed against the large potential benefits of dolutegravir,” investigator Rebecca M. Zash, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said here in Mexico City during an IAS 2019 video press conference.

The WHO had previously sounded a note of caution, saying that DTG could be “considered” in women of childbearing age if other first‐line antiretroviral agents such as efavirenz could not be used.

However, following release of new evidence, including the study by Dr. Zash and colleagues, the WHO has come out with a clear recommendation for HIV drug as “the preferred first-line and second-line treatment for all populations, including pregnant women and those of childbearing potential.”

The updated scientific reports and guidelines have important implications for global health. “Many countries have been working to make dolutegravir-based treatment their preferred first-line regimen, as it’s got several advantages over efavirenz, which people have been using for many years now, including its tolerability and resistance profiles, and its impact on morbidity and mortality,” IAS president Anton Pozniak, MD, said in the press conference.

Some countries paused their plans to roll out dolutegravir-based regimens after the preliminary safety signal from the Tsepamo study was reported, Dr. Pozniak added.

In another study presented at IAS looking at dolutegravir use at conception, investigators described an additional surveillance study in Botswana, conducted independently from the Tsepamo study. One neural tube defect was found among 152 deliveries in mothers who had been taking DTG at conception (0.66%), and two neural tube defects among 2,326 deliveries to HIV-negative mothers (0.09%).

Although the number of deliveries are small in this study, the results suggest a risk of neural tube defects with DTG exposure at conception of less than 1%, said Mmakgomo Mimi Raesima, MD, MPH, public health specialist, Ministry of Health and Wellness, Botswana.

Because neural-tube defects might be related to low folate levels, Dr. Raesima said “conversations are continuing” with regard to folate food fortification in Botswana, a country that does not mandate folate-fortified grains.

“We want to capitalize on the momentum from these results,” Dr. Raesima said in the press conference.

The Tsepamo study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zash reported grants during the conduct of the study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Zash R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905230.

The risk of neural tube defects linked to dolutegravir exposure during pregnancy is lower than previously signaled, according to new reports that have prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to confirm that this antiviral medication should be the preferred option across all populations.

The use of dolutegravir (DTG) during pregnancy has been a pressing global health question since May 2018, when an unplanned interim analysis of the Tsepamo surveillance study of birth outcomes in Botswana showed four neural tube defects associated with dolutegravir exposure among 426 infants born to HIV-positive women (0.94%).

With follow-up for additional births, however, just one more neural tube defect was identified out of 1,683 deliveries among women who had taken DTG around the time of conception (0.30%), according to a report just presented here at the at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

By comparison, prevalence rates of neural tube defects were 0.10% for mothers taking other antiretroviral therapies at conception, 0.04% for those specifically taking efavirenz at conception, and 0.08% in HIV-uninfected mothers, according to the report, which was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“While there may be a risk for neural tube defects, this risk is small, and really importantly, needs to be weighed against the large potential benefits of dolutegravir,” investigator Rebecca M. Zash, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said here in Mexico City during an IAS 2019 video press conference.

The WHO had previously sounded a note of caution, saying that DTG could be “considered” in women of childbearing age if other first‐line antiretroviral agents such as efavirenz could not be used.

However, following release of new evidence, including the study by Dr. Zash and colleagues, the WHO has come out with a clear recommendation for HIV drug as “the preferred first-line and second-line treatment for all populations, including pregnant women and those of childbearing potential.”

The updated scientific reports and guidelines have important implications for global health. “Many countries have been working to make dolutegravir-based treatment their preferred first-line regimen, as it’s got several advantages over efavirenz, which people have been using for many years now, including its tolerability and resistance profiles, and its impact on morbidity and mortality,” IAS president Anton Pozniak, MD, said in the press conference.

Some countries paused their plans to roll out dolutegravir-based regimens after the preliminary safety signal from the Tsepamo study was reported, Dr. Pozniak added.

In another study presented at IAS looking at dolutegravir use at conception, investigators described an additional surveillance study in Botswana, conducted independently from the Tsepamo study. One neural tube defect was found among 152 deliveries in mothers who had been taking DTG at conception (0.66%), and two neural tube defects among 2,326 deliveries to HIV-negative mothers (0.09%).

Although the number of deliveries are small in this study, the results suggest a risk of neural tube defects with DTG exposure at conception of less than 1%, said Mmakgomo Mimi Raesima, MD, MPH, public health specialist, Ministry of Health and Wellness, Botswana.

Because neural-tube defects might be related to low folate levels, Dr. Raesima said “conversations are continuing” with regard to folate food fortification in Botswana, a country that does not mandate folate-fortified grains.

“We want to capitalize on the momentum from these results,” Dr. Raesima said in the press conference.

The Tsepamo study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zash reported grants during the conduct of the study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Zash R et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905230.

FROM IAS 2019

iPledge: Fetal exposure to isotretinoin continues

but pregnancy, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure are still occurring in women of reproductive age, according to a retrospective study published in JAMA Dermatology.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration implemented the iPledge program, with requirements that include women of childbearing age having a negative pregnancy test and evidence of using two forms of contraception monthly to use isotretinoin, a teratogen. “Although the number of pregnancy-related adverse events for patients taking isotretinoin has decreased since 2006, pregnancies, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure continue to be a problem,” Elizabeth Tkachenko, BS, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, and coauthors concluded. “Further research is required to determine the most efficacious system to reduce complications for patients and administrative requirements for physicians while at the same time maintaining access to this important drug.” (iPledge followed other Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy systems for isotretinoin.)

She and her colleagues performed a retrospective evaluation of pregnancy-related adverse events related to isotretinoin that had occurred between January 1997 and December 2017 using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), which receives reports from prescribers, consumers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. While there could be many different classification terms for each individual, any number of adverse events reported by an individual was counted as one pregnancy. Ms. Tkachenko and colleagues classified abortions, pregnancies during contraception use, and pregnancy-related defects into separate subgroups for analysis.

From 1997 to 2017, there were 6,740 pregnancies among women (mean age, 24.6 years) during treatment with isotretinoin reported to FAERS, with 7 reports in 1997, and a peak of 768 pregnancies in 2006. Almost 70% (4,647) of the pregnancies were reported after iPledge was introduced. Between 2011 and 2017, there were 218-310 pregnancy reports each year.

Of the total number of pregnancy reports during the study period, 1,896 were abortions (28.1% of the total); 10.9% of the total number of pregnancy reports were spontaneous abortions (733). The number of abortions peaked in 2008, with 291 reports, of which 85% were therapeutic abortions. Also peaking in 2008 was the number of reports of pregnancies while taking a contraceptive (64). After 2008, pregnancies and abortions dropped.

Fetal defects peaked in 2000, with 34 cases reported, and dropped to four or fewer reports annually after 2008.

“Our findings demonstrate that reports of pregnancy among women taking isotretinoin are concentrated among those aged 20 to 29 years, peaked in 2006, and have been consistent since 2011,” the authors wrote.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include limitations of FAERS data and possible reporting fatigue among doctors and patients. The total number of isotretinoin courses prescribed to this patient population is also unknown, which affected their ability to determine the true rate of pregnancy-related adverse events, they noted.

The other authors for this study were from Harvard Medical School and the departments of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, as well as the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One author reported support from an award by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health and salary support from a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tkachenko E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

The rate of fetal exposure to isotretinoin has generally decreased since the implementation of the iPledge program, but rates have plateaued since 2011, and it is unclear why the exposure rate does not continue to decrease, Arielle R. Nagler, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

As noted by Tkachenko et al., it is not possible to infer that iPledge resulted in declines in fetal exposure, abortions, and pregnancy-related complications. Use of long-acting reversible contraception, education about contraception use, and reporting fatigue could be factors in the decline, Dr. Nagler noted. “The inability to clearly demonstrate causality, combined with the unexplained delay and plateau in the number of fetal exposures to isotretinoin after the implementation of iPledge, makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of iPledge in this reported trend,” she said.

The decrease in fetal exposure could also potentially be explained by effects of iPledge on the availability of isotretinoin for women of childbearing age. Indeed, studies have shown a significant decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions in this patient population after iPledge was implemented.

Despite lack of data, there is still too much fetal exposure to isotretinoin, wrote Dr. Nagler, which calls into question the efficacy of the iPledge program. “We can all agree that 1 fetal exposure to isotretinoin should be too many, but without taking isotretinoin off the market, we will never achieve zero fetal exposures to isotretinoin. Still, we can – and should – expect more from a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] program,” Dr. Nagler concluded.

Dr. Nagler is with the department of dermatology at New York University. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The rate of fetal exposure to isotretinoin has generally decreased since the implementation of the iPledge program, but rates have plateaued since 2011, and it is unclear why the exposure rate does not continue to decrease, Arielle R. Nagler, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

As noted by Tkachenko et al., it is not possible to infer that iPledge resulted in declines in fetal exposure, abortions, and pregnancy-related complications. Use of long-acting reversible contraception, education about contraception use, and reporting fatigue could be factors in the decline, Dr. Nagler noted. “The inability to clearly demonstrate causality, combined with the unexplained delay and plateau in the number of fetal exposures to isotretinoin after the implementation of iPledge, makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of iPledge in this reported trend,” she said.

The decrease in fetal exposure could also potentially be explained by effects of iPledge on the availability of isotretinoin for women of childbearing age. Indeed, studies have shown a significant decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions in this patient population after iPledge was implemented.

Despite lack of data, there is still too much fetal exposure to isotretinoin, wrote Dr. Nagler, which calls into question the efficacy of the iPledge program. “We can all agree that 1 fetal exposure to isotretinoin should be too many, but without taking isotretinoin off the market, we will never achieve zero fetal exposures to isotretinoin. Still, we can – and should – expect more from a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] program,” Dr. Nagler concluded.

Dr. Nagler is with the department of dermatology at New York University. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The rate of fetal exposure to isotretinoin has generally decreased since the implementation of the iPledge program, but rates have plateaued since 2011, and it is unclear why the exposure rate does not continue to decrease, Arielle R. Nagler, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

As noted by Tkachenko et al., it is not possible to infer that iPledge resulted in declines in fetal exposure, abortions, and pregnancy-related complications. Use of long-acting reversible contraception, education about contraception use, and reporting fatigue could be factors in the decline, Dr. Nagler noted. “The inability to clearly demonstrate causality, combined with the unexplained delay and plateau in the number of fetal exposures to isotretinoin after the implementation of iPledge, makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the role of iPledge in this reported trend,” she said.

The decrease in fetal exposure could also potentially be explained by effects of iPledge on the availability of isotretinoin for women of childbearing age. Indeed, studies have shown a significant decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions in this patient population after iPledge was implemented.

Despite lack of data, there is still too much fetal exposure to isotretinoin, wrote Dr. Nagler, which calls into question the efficacy of the iPledge program. “We can all agree that 1 fetal exposure to isotretinoin should be too many, but without taking isotretinoin off the market, we will never achieve zero fetal exposures to isotretinoin. Still, we can – and should – expect more from a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] program,” Dr. Nagler concluded.

Dr. Nagler is with the department of dermatology at New York University. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

but pregnancy, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure are still occurring in women of reproductive age, according to a retrospective study published in JAMA Dermatology.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration implemented the iPledge program, with requirements that include women of childbearing age having a negative pregnancy test and evidence of using two forms of contraception monthly to use isotretinoin, a teratogen. “Although the number of pregnancy-related adverse events for patients taking isotretinoin has decreased since 2006, pregnancies, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure continue to be a problem,” Elizabeth Tkachenko, BS, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, and coauthors concluded. “Further research is required to determine the most efficacious system to reduce complications for patients and administrative requirements for physicians while at the same time maintaining access to this important drug.” (iPledge followed other Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy systems for isotretinoin.)

She and her colleagues performed a retrospective evaluation of pregnancy-related adverse events related to isotretinoin that had occurred between January 1997 and December 2017 using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), which receives reports from prescribers, consumers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. While there could be many different classification terms for each individual, any number of adverse events reported by an individual was counted as one pregnancy. Ms. Tkachenko and colleagues classified abortions, pregnancies during contraception use, and pregnancy-related defects into separate subgroups for analysis.

From 1997 to 2017, there were 6,740 pregnancies among women (mean age, 24.6 years) during treatment with isotretinoin reported to FAERS, with 7 reports in 1997, and a peak of 768 pregnancies in 2006. Almost 70% (4,647) of the pregnancies were reported after iPledge was introduced. Between 2011 and 2017, there were 218-310 pregnancy reports each year.

Of the total number of pregnancy reports during the study period, 1,896 were abortions (28.1% of the total); 10.9% of the total number of pregnancy reports were spontaneous abortions (733). The number of abortions peaked in 2008, with 291 reports, of which 85% were therapeutic abortions. Also peaking in 2008 was the number of reports of pregnancies while taking a contraceptive (64). After 2008, pregnancies and abortions dropped.

Fetal defects peaked in 2000, with 34 cases reported, and dropped to four or fewer reports annually after 2008.

“Our findings demonstrate that reports of pregnancy among women taking isotretinoin are concentrated among those aged 20 to 29 years, peaked in 2006, and have been consistent since 2011,” the authors wrote.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include limitations of FAERS data and possible reporting fatigue among doctors and patients. The total number of isotretinoin courses prescribed to this patient population is also unknown, which affected their ability to determine the true rate of pregnancy-related adverse events, they noted.

The other authors for this study were from Harvard Medical School and the departments of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, as well as the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One author reported support from an award by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health and salary support from a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tkachenko E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

but pregnancy, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure are still occurring in women of reproductive age, according to a retrospective study published in JAMA Dermatology.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration implemented the iPledge program, with requirements that include women of childbearing age having a negative pregnancy test and evidence of using two forms of contraception monthly to use isotretinoin, a teratogen. “Although the number of pregnancy-related adverse events for patients taking isotretinoin has decreased since 2006, pregnancies, abortions, and fetal defects associated with isotretinoin exposure continue to be a problem,” Elizabeth Tkachenko, BS, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, and coauthors concluded. “Further research is required to determine the most efficacious system to reduce complications for patients and administrative requirements for physicians while at the same time maintaining access to this important drug.” (iPledge followed other Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy systems for isotretinoin.)

She and her colleagues performed a retrospective evaluation of pregnancy-related adverse events related to isotretinoin that had occurred between January 1997 and December 2017 using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), which receives reports from prescribers, consumers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. While there could be many different classification terms for each individual, any number of adverse events reported by an individual was counted as one pregnancy. Ms. Tkachenko and colleagues classified abortions, pregnancies during contraception use, and pregnancy-related defects into separate subgroups for analysis.

From 1997 to 2017, there were 6,740 pregnancies among women (mean age, 24.6 years) during treatment with isotretinoin reported to FAERS, with 7 reports in 1997, and a peak of 768 pregnancies in 2006. Almost 70% (4,647) of the pregnancies were reported after iPledge was introduced. Between 2011 and 2017, there were 218-310 pregnancy reports each year.

Of the total number of pregnancy reports during the study period, 1,896 were abortions (28.1% of the total); 10.9% of the total number of pregnancy reports were spontaneous abortions (733). The number of abortions peaked in 2008, with 291 reports, of which 85% were therapeutic abortions. Also peaking in 2008 was the number of reports of pregnancies while taking a contraceptive (64). After 2008, pregnancies and abortions dropped.

Fetal defects peaked in 2000, with 34 cases reported, and dropped to four or fewer reports annually after 2008.

“Our findings demonstrate that reports of pregnancy among women taking isotretinoin are concentrated among those aged 20 to 29 years, peaked in 2006, and have been consistent since 2011,” the authors wrote.

Limitations of the study, they noted, include limitations of FAERS data and possible reporting fatigue among doctors and patients. The total number of isotretinoin courses prescribed to this patient population is also unknown, which affected their ability to determine the true rate of pregnancy-related adverse events, they noted.

The other authors for this study were from Harvard Medical School and the departments of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, as well as the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. One author reported support from an award by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health and salary support from a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tkachenko E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Little association found between in utero H1N1 vaccine and 5-year health outcomes

according to Laura K. Walsh of the University of Ottawa and associates.

The investigators conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study from November 2009 to October 2010 of all live births within the province of Ontario. Of the 104,249 eligible live births reported to the Ontario birth registry, 31,295 were exposed to the H1N1 vaccine in utero. After adjustment, there were no significant differences in the women who did and did not receive vaccines during pregnancy, according to the study, published in the BMJ.

After a median follow-up of 5 years, 14% of children received an asthma diagnosis, with a median age at diagnosis of 1.8 years. Children were more likely to receive an asthma diagnosis if their mothers had a preexisting condition or if they were born preterm. At follow-up, 34% of children had at least one upper respiratory tract infection. Sensory disorder, neoplasm, and pediatric complex chronic condition were rare, each occurring in less than 1% of the study cohort (BMJ. 2019 Jul 10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4151).

No significant association was found between prenatal exposure to the H1N1 vaccine and upper or lower respiratory infections, otitis media, all infections, neoplasms, sensory disorders, rates of urgent and inpatient health services use, pediatric complex chronic conditions, or mortality. A weak but significant association was observed for asthma (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.09), and a weak inverse association was found for gastrointestinal infections (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91-0.98).

“Although we observed a small, but statistically significant, increase in pediatric asthma and a reduction in gastrointestinal infections, we are not aware of any biologic mechanisms to explain these findings. Future studies in different settings and with different influenza vaccine formulations will be important for developing the evidence base on longer-term pediatric outcomes following influenza vaccination during pregnancy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

according to Laura K. Walsh of the University of Ottawa and associates.

The investigators conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study from November 2009 to October 2010 of all live births within the province of Ontario. Of the 104,249 eligible live births reported to the Ontario birth registry, 31,295 were exposed to the H1N1 vaccine in utero. After adjustment, there were no significant differences in the women who did and did not receive vaccines during pregnancy, according to the study, published in the BMJ.

After a median follow-up of 5 years, 14% of children received an asthma diagnosis, with a median age at diagnosis of 1.8 years. Children were more likely to receive an asthma diagnosis if their mothers had a preexisting condition or if they were born preterm. At follow-up, 34% of children had at least one upper respiratory tract infection. Sensory disorder, neoplasm, and pediatric complex chronic condition were rare, each occurring in less than 1% of the study cohort (BMJ. 2019 Jul 10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4151).

No significant association was found between prenatal exposure to the H1N1 vaccine and upper or lower respiratory infections, otitis media, all infections, neoplasms, sensory disorders, rates of urgent and inpatient health services use, pediatric complex chronic conditions, or mortality. A weak but significant association was observed for asthma (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.09), and a weak inverse association was found for gastrointestinal infections (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91-0.98).

“Although we observed a small, but statistically significant, increase in pediatric asthma and a reduction in gastrointestinal infections, we are not aware of any biologic mechanisms to explain these findings. Future studies in different settings and with different influenza vaccine formulations will be important for developing the evidence base on longer-term pediatric outcomes following influenza vaccination during pregnancy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

according to Laura K. Walsh of the University of Ottawa and associates.

The investigators conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study from November 2009 to October 2010 of all live births within the province of Ontario. Of the 104,249 eligible live births reported to the Ontario birth registry, 31,295 were exposed to the H1N1 vaccine in utero. After adjustment, there were no significant differences in the women who did and did not receive vaccines during pregnancy, according to the study, published in the BMJ.

After a median follow-up of 5 years, 14% of children received an asthma diagnosis, with a median age at diagnosis of 1.8 years. Children were more likely to receive an asthma diagnosis if their mothers had a preexisting condition or if they were born preterm. At follow-up, 34% of children had at least one upper respiratory tract infection. Sensory disorder, neoplasm, and pediatric complex chronic condition were rare, each occurring in less than 1% of the study cohort (BMJ. 2019 Jul 10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4151).

No significant association was found between prenatal exposure to the H1N1 vaccine and upper or lower respiratory infections, otitis media, all infections, neoplasms, sensory disorders, rates of urgent and inpatient health services use, pediatric complex chronic conditions, or mortality. A weak but significant association was observed for asthma (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.09), and a weak inverse association was found for gastrointestinal infections (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91-0.98).

“Although we observed a small, but statistically significant, increase in pediatric asthma and a reduction in gastrointestinal infections, we are not aware of any biologic mechanisms to explain these findings. Future studies in different settings and with different influenza vaccine formulations will be important for developing the evidence base on longer-term pediatric outcomes following influenza vaccination during pregnancy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

FROM THE BMJ

Expert advice for immediate postpartum LARC insertion

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

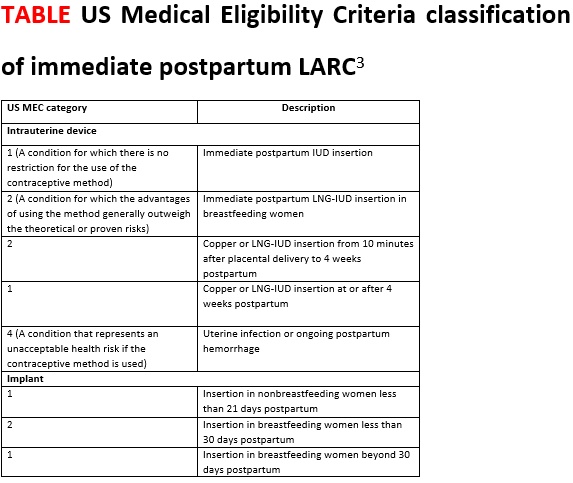

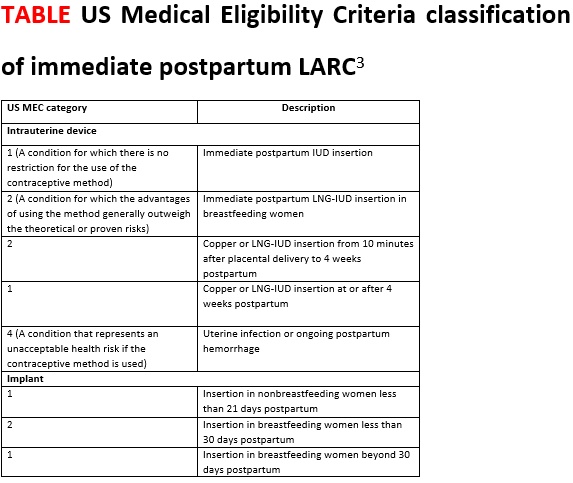

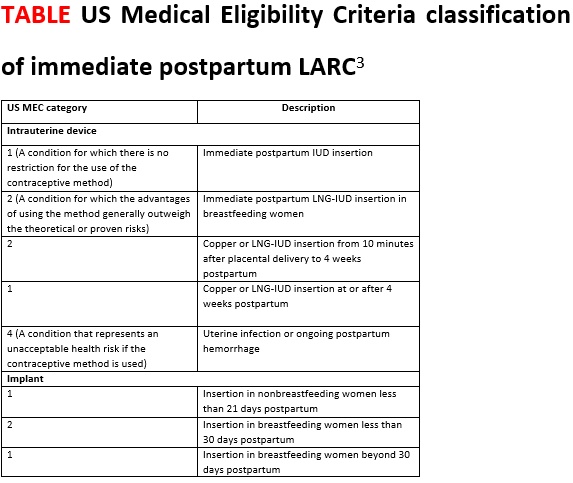

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.

1. Dole DM, Martin J. What nurses need to know about immediate postpartum initiation of long-acting reversible contraception. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21:186-195.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice Bulletin no. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

4. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-104.