User login

Plasma Omega-6 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids Inversely Associated With Cancer

TOPLINE:

Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids are associated with a lower incidence of cancer. However, omega-3 fatty acids are linked to an increased risk for prostate cancer, specifically.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers looked for associations of plasma omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with the incidence of cancer overall and 19 site-specific cancers in the large population-based prospective UK Biobank cohort.

- They included 253,138 participants aged 37-73 years who were followed for an average of 12.9 years, with 29,838 diagnosed with cancer.

- Plasma levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids were measured using nuclear magnetic resonance and expressed as percentages of total fatty acids.

- Participants with cancer diagnoses at baseline, those who withdrew from the study, and those with missing data on plasma PUFAs were excluded.

- The study adjusted for multiple covariates, including age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and family history of diseases.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids were associated with a 2% and 1% reduction in overall cancer risk per SD increase, respectively (P = .001 and P = .03).

- Omega-6 fatty acids were inversely associated with 14 site-specific cancers, whereas omega-3 fatty acids were inversely associated with five site-specific cancers.

- Prostate cancer was positively associated with omega-3 fatty acids, with a 3% increased risk per SD increase (P = .049).

- A higher omega-6/omega-3 ratio was associated with an increased risk for overall cancer, and three site-specific cancers showed positive associations with the ratio. “Each standard deviation increase, corresponding to a 13.13 increase in the omega ratio, was associated with a 2% increase in the risk of rectum cancer,” for example, the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, our findings provide support for possible small net protective roles of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in the development of new cancer incidence. Our study also suggests that the usage of circulating blood biomarkers captures different aspects of dietary intake, reduces measurement errors, and thus enhances statistical power. The differential effects of omega-6% and omega-3% in age and sex subgroups warrant future investigation,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yuchen Zhang of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia. It was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s potential for selective bias persists due to the participant sample skewing heavily toward European ancestry and White ethnicity. The number of events was small for some specific cancer sites, which may have limited the statistical power. The study focused on total omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, with only two individual fatty acids measured. Future studies are needed to examine the roles of other individual PUFAs and specific genetic variants.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids are associated with a lower incidence of cancer. However, omega-3 fatty acids are linked to an increased risk for prostate cancer, specifically.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers looked for associations of plasma omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with the incidence of cancer overall and 19 site-specific cancers in the large population-based prospective UK Biobank cohort.

- They included 253,138 participants aged 37-73 years who were followed for an average of 12.9 years, with 29,838 diagnosed with cancer.

- Plasma levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids were measured using nuclear magnetic resonance and expressed as percentages of total fatty acids.

- Participants with cancer diagnoses at baseline, those who withdrew from the study, and those with missing data on plasma PUFAs were excluded.

- The study adjusted for multiple covariates, including age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and family history of diseases.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids were associated with a 2% and 1% reduction in overall cancer risk per SD increase, respectively (P = .001 and P = .03).

- Omega-6 fatty acids were inversely associated with 14 site-specific cancers, whereas omega-3 fatty acids were inversely associated with five site-specific cancers.

- Prostate cancer was positively associated with omega-3 fatty acids, with a 3% increased risk per SD increase (P = .049).

- A higher omega-6/omega-3 ratio was associated with an increased risk for overall cancer, and three site-specific cancers showed positive associations with the ratio. “Each standard deviation increase, corresponding to a 13.13 increase in the omega ratio, was associated with a 2% increase in the risk of rectum cancer,” for example, the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, our findings provide support for possible small net protective roles of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in the development of new cancer incidence. Our study also suggests that the usage of circulating blood biomarkers captures different aspects of dietary intake, reduces measurement errors, and thus enhances statistical power. The differential effects of omega-6% and omega-3% in age and sex subgroups warrant future investigation,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yuchen Zhang of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia. It was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s potential for selective bias persists due to the participant sample skewing heavily toward European ancestry and White ethnicity. The number of events was small for some specific cancer sites, which may have limited the statistical power. The study focused on total omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, with only two individual fatty acids measured. Future studies are needed to examine the roles of other individual PUFAs and specific genetic variants.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids are associated with a lower incidence of cancer. However, omega-3 fatty acids are linked to an increased risk for prostate cancer, specifically.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers looked for associations of plasma omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with the incidence of cancer overall and 19 site-specific cancers in the large population-based prospective UK Biobank cohort.

- They included 253,138 participants aged 37-73 years who were followed for an average of 12.9 years, with 29,838 diagnosed with cancer.

- Plasma levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids were measured using nuclear magnetic resonance and expressed as percentages of total fatty acids.

- Participants with cancer diagnoses at baseline, those who withdrew from the study, and those with missing data on plasma PUFAs were excluded.

- The study adjusted for multiple covariates, including age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors, and family history of diseases.

TAKEAWAY:

- Higher plasma levels of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids were associated with a 2% and 1% reduction in overall cancer risk per SD increase, respectively (P = .001 and P = .03).

- Omega-6 fatty acids were inversely associated with 14 site-specific cancers, whereas omega-3 fatty acids were inversely associated with five site-specific cancers.

- Prostate cancer was positively associated with omega-3 fatty acids, with a 3% increased risk per SD increase (P = .049).

- A higher omega-6/omega-3 ratio was associated with an increased risk for overall cancer, and three site-specific cancers showed positive associations with the ratio. “Each standard deviation increase, corresponding to a 13.13 increase in the omega ratio, was associated with a 2% increase in the risk of rectum cancer,” for example, the authors wrote.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, our findings provide support for possible small net protective roles of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in the development of new cancer incidence. Our study also suggests that the usage of circulating blood biomarkers captures different aspects of dietary intake, reduces measurement errors, and thus enhances statistical power. The differential effects of omega-6% and omega-3% in age and sex subgroups warrant future investigation,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yuchen Zhang of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia. It was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s potential for selective bias persists due to the participant sample skewing heavily toward European ancestry and White ethnicity. The number of events was small for some specific cancer sites, which may have limited the statistical power. The study focused on total omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, with only two individual fatty acids measured. Future studies are needed to examine the roles of other individual PUFAs and specific genetic variants.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Disparities in Skin Cancer Outcomes in the Latine/Hispanic Population

The Latine/Hispanic population in the United States comprises one of the largest and youngest skin of color communities.1,2 In 2020, this group accounted for 19% of all Americans—a percentage expected to increase to more than 25% by 2060.3

It must be emphasized that the Latine/Hispanic community in the United States is incredibly diverse.4 Approximately one-third of individuals in this group are foreign-born, and this community is made up of people from all racialized groups, religions, languages, and cultural identities.2 The heterogeneity of the Latine/Hispanic population translates into a wide representation of skin tones, reflecting a rich range of ancestries, ethnicities, and cultures. The percentage of individuals from each origin group may differ according to where they live in the United States; for instance, individuals who identify as Mexican comprise more than 80% of the Latine/Hispanic population in both Texas and California but only 17% in Florida, where more than half of Latine/Hispanic people identify as Cuban or Puerto Rican.4,5 As a result, when it comes to skin cancer epidemiology, variations in incidence and mortality may exist within each of these subgroups who identify as part of the Latine/Hispanic community, as reported for other cancers.6,7 Further research is needed to investigate these potential differences.Unfortunately, considerable health disparities persist among this rapidly growing population, including increased morbidity and mortality from melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) despite overall low lifetime incidence.8,9 In this review, the epidemiology, clinical manifestation, and ethnic disparities for skin cancer among the US Latine/Hispanic population are summarized; other factors impacting overall health and health care, including sociocultural factors, also are briefly discussed.

Terminology

Before a meaningful dialogue can be had about skin cancer in the Latine/Hispanic population, it is important to contextualize the terms used to identify this patient population, including Latino/Latine and Hispanic. In the early 1970s, the United States adopted the term Hispanic as a way of conglomerating Spanish-speaking individuals from Spain, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The goal was to implement a common identifier that enabled the US government to study the economic and social development of these groups.10 Nevertheless, considerable differences (eg, variations in skin pigmentation, sun sensitivity) exist among Hispanic communities, with some having stronger European, African, or Amerindian influences due to colonization of their distinct countries.11

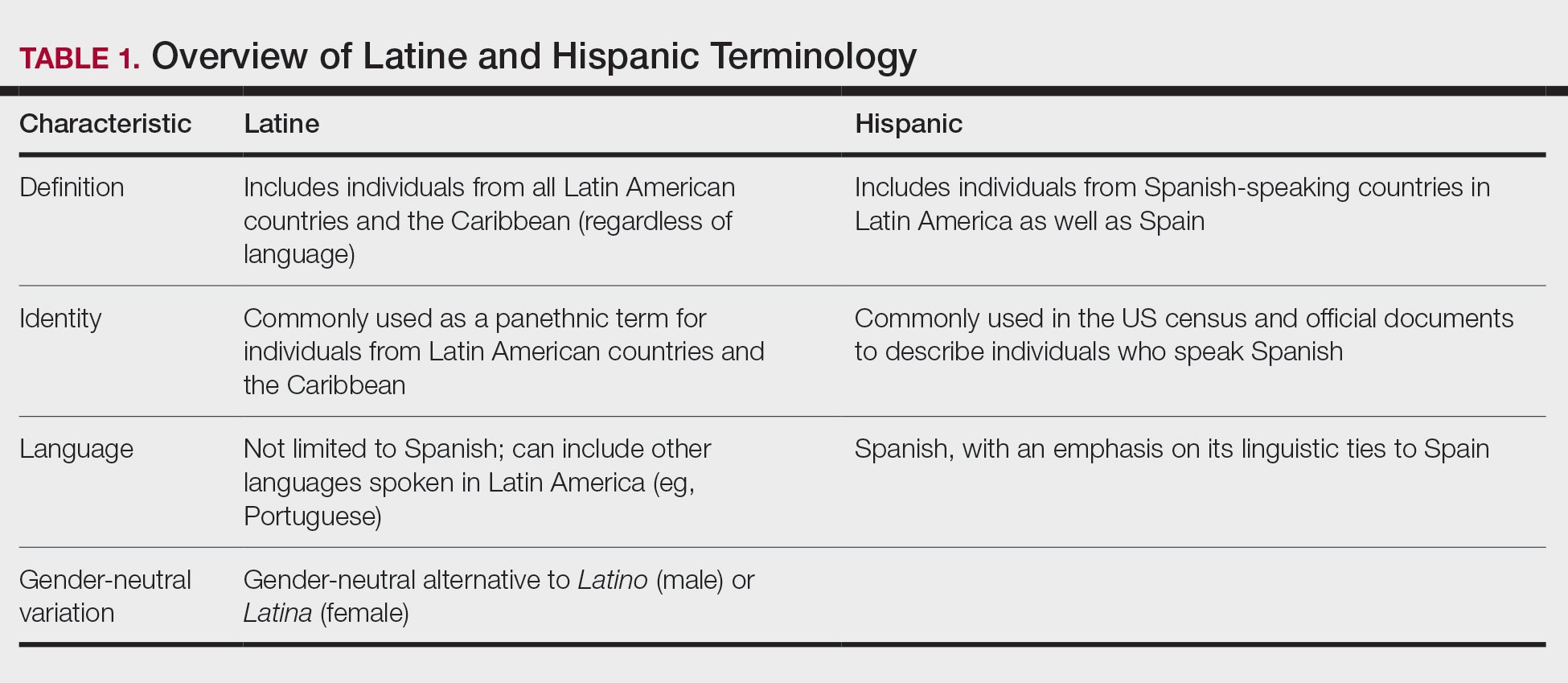

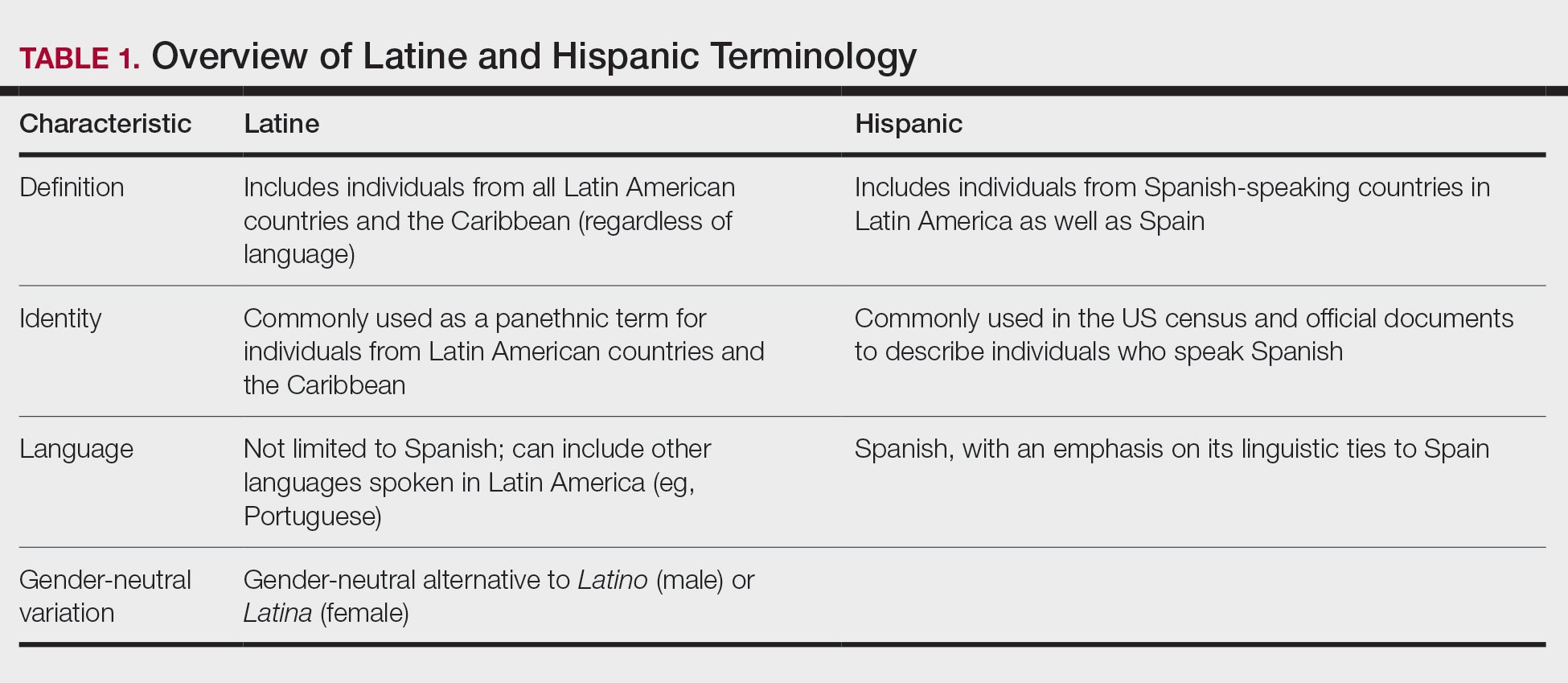

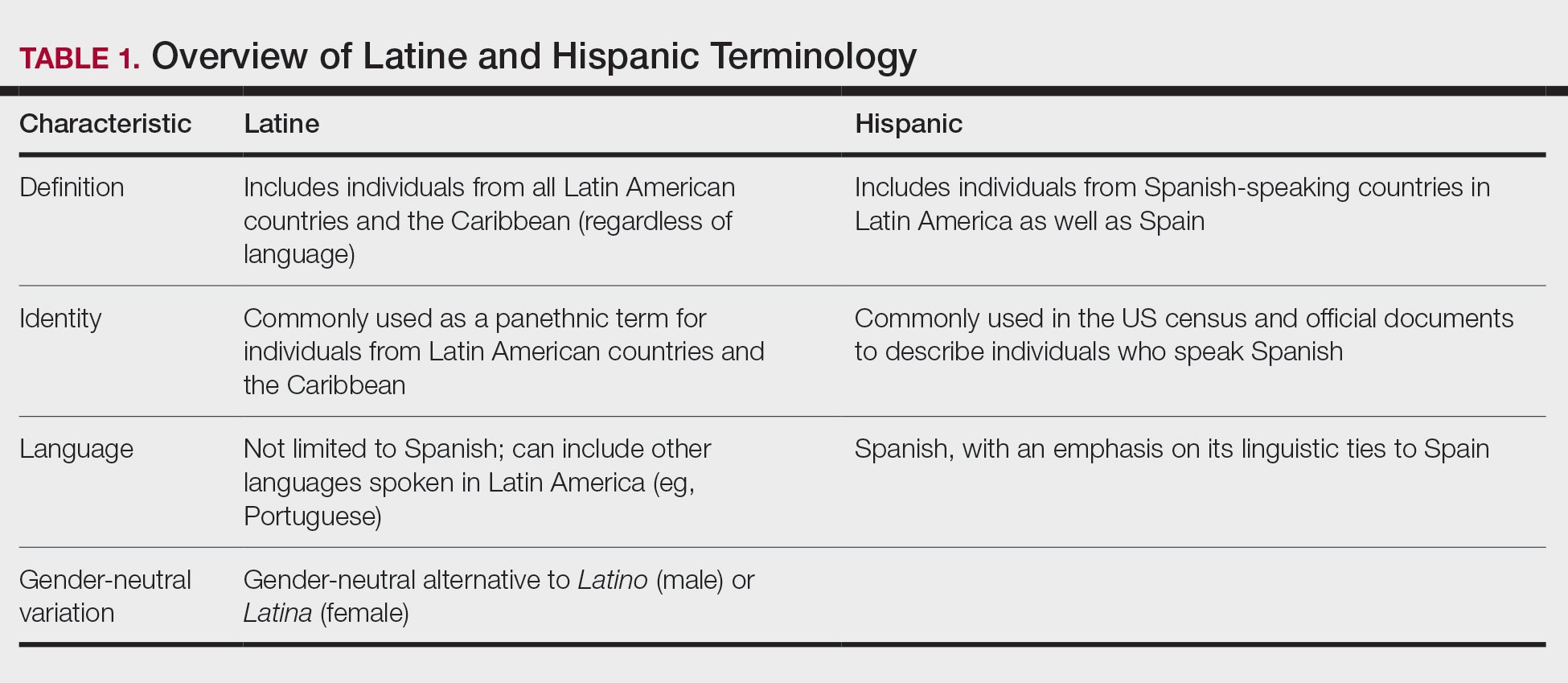

In contrast, Latino is a geographic term and refers to people with roots in Latin America and the Caribbean (Table 1).12,13 For example, a person from Brazil may be considered Latino but not Hispanic as Brazilians speak Portuguese; alternatively, Spaniards (who are considered Hispanic) are not Latino because Spain is not a Latin American country. A person from Mexico would be considered both Latino and Hispanic.13

More recently, the term Latine has been introduced as an alternative to the gender binary inherent in the Spanish language.12 For the purposes of this article, the terms Latine and Hispanic will be used interchangeably (unless otherwise specified) depending on how they are cited in the existing literature. Furthermore, the term non-Hispanic White (NHW) will be used to refer to individuals who have been socially ascribed or who self-identify as White in terms of race or ethnicity.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is more likely to metastasize compared to other forms of skin cancer, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). For Latine/Hispanic individuals living in the United States, the lifetime risk for melanoma is 1 in 200 compared to 1 in 33 for NHW individuals.14 While the lifetime risk for melanoma is low for the Latine/Hispanic population, Hispanic individuals are diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age (mean, 56 years), and the rate of new cases is marginally higher for women (4.9 per 100,000) compared to men (4.8 per 100,000).15,16

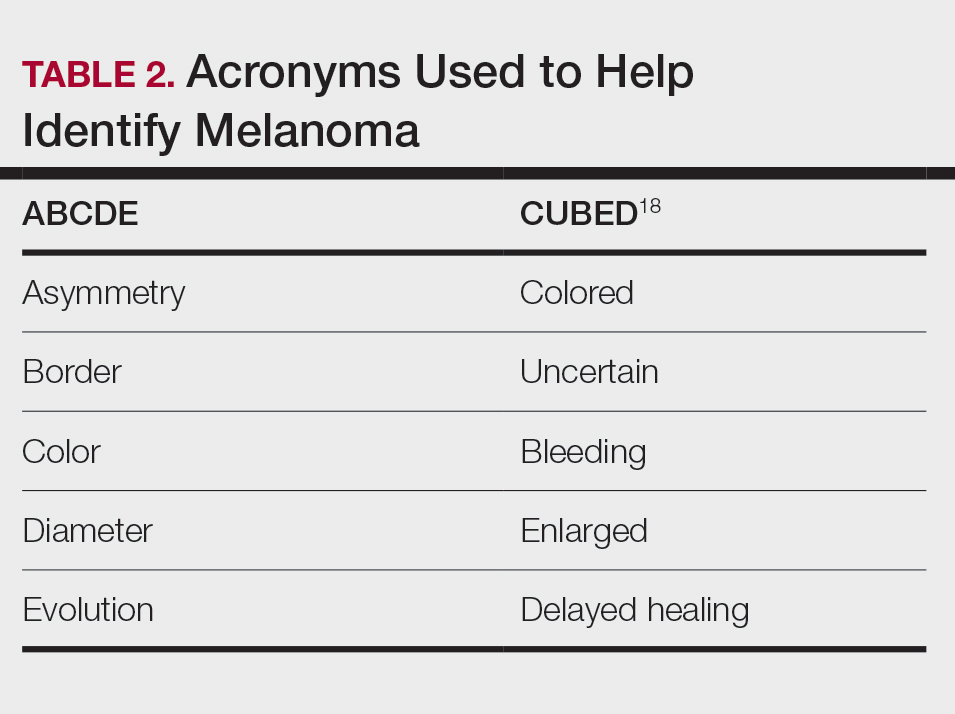

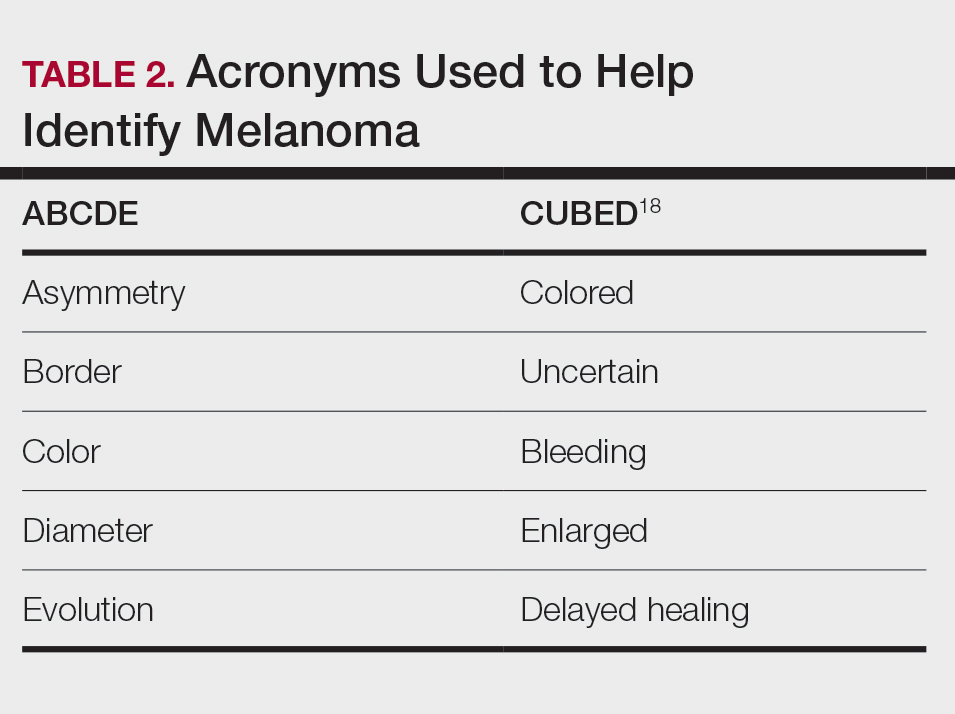

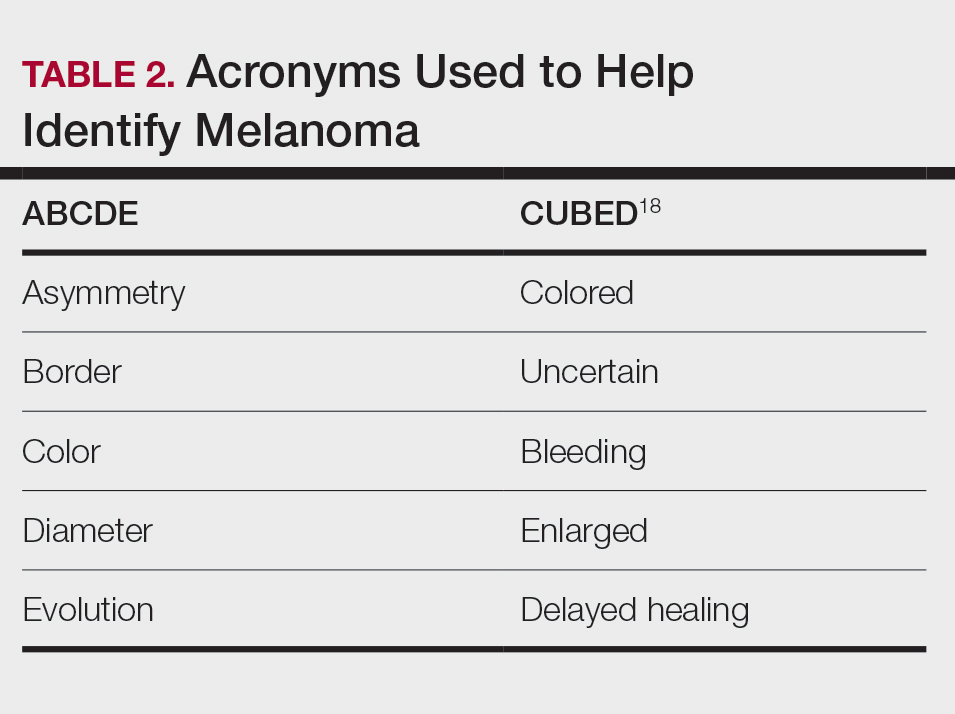

Typical sites of melanoma manifestation in Latine/Hispanic individuals include the torso (most common site in Hispanic men), lower extremities (most common site in Hispanic women), and acral sites (palms, soles, and nails).9,16,17 Anatomic location also can vary according to age for both men and women. For men, the incidence of melanoma on the trunk appears to decrease with age, while the incidence on the head and neck may increase. For women, the incidence of melanoma on the lower extremities and hip increases with age. Cutaneous melanoma may manifest as a lesion with asymmetry, irregular borders, variation in pigmentation, large diameter (>6 mm), and evolution over time. In patients with skin of color, melanoma easily can be missed, as it also typically mimics more benign skin conditions and may develop from an existing black- or dark brown–pigmented macule.18 The most common histologic subtype reported among Latine/Hispanic individuals in the United States is superficial spreading melanoma (20%–23%) followed by nodular melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma.16,19 Until additional risk factors associated with melanoma susceptibility in Hispanic/Latine people are better elucidated, it may be appropriate to use an alternative acronym, such as CUBED (Table 2), in addition to the standard ABCDE system to help recognize potential melanoma on acral sites.18

Although the lifetime risk for melanoma among Hispanic individuals in the United States is lower than that for NHW individuals, Hispanic patients who are diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with increased tumor thickness and later-stage diagnosis compared to NHW individuals.8,16,20 In a recent study by Qian et al,8 advanced stage melanoma—defined as regional or distant stage disease—was present in 12.6% of NHW individuals. In contrast, the percentage of Hispanics with advanced disease was higher at 21%.8 Even after controlling for insurance and poverty status, Hispanic individuals were at greater risk than NHW individuals for late-stage diagnosis.16,20

Morbidity and mortality also have been shown to be higher in Hispanic patients with cutaneous melanoma.9,17 Reasons for this are multifactorial, with studies specific to melanoma citing challenges associated with early detection in individuals with deeply pigmented skin, a lack of awareness and knowledge about skin cancer among Latine/Hispanic patients, and treatment disparities.21-23 Moreover, very few studies have reported comprehensive data on patients from Africa and Latin America. Studies examining the role of genetic ancestry, epigenetic variants, and skin pigmentation and the risk for melanoma among the Latine/Hispanic population therefore are much needed.24

Keratinocyte Carcinomas

Keratinocyte carcinomas, also known as nonmelanoma skin cancers, include BCC and SCC. In comparison to the high-quality data available for melanoma from cancer registries, there are less reliable incidence data for KCs, especially among individuals with skin of color.25 As a result, KC epidemiology in the United States is drawn largely from case series (especially for individuals with skin of color) or claims data from small data sets often from geographically restricted regions within the United States.25,26

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant skin cancer in Latine/Hispanic individuals. Among those with lighter skin tones, the lifetime risk for BCC is about 30%.27,28 Men typically are affected at a higher rate than women, and the median age for diagnosis is 68 years.29 The development of BCC primarily is linked to lifetime accumulated UV radiation exposure. Even though BCC has a low mortality rate, it can lead to substantial morbidity due to factors such as tumor location, size, and rate of invasion, resulting in cosmetic and functional issues. Given its low metastatic potential, treatment of BCC typically is aimed at local control.30 Options for treatment include Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), curettage and electrodessication, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, and topical therapies. Systemic therapies are reserved for patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease.30

Latine/Hispanic patients characteristically present with BCCs on sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the head and neck region. In most patients, BCC manifests as a translucent pearly nodule with superficial telangiectasias and/or a nonhealing ulcer with a central depression and rolled nontender borders. However, in patients with skin of color, 66% of BCCs manifest with pigmentation; in fact, pigmented BCC (a subtype of BCC) has been shown to have a higher prevalence among Hispanic individuals, with an incidence twice as frequent as in NHW individuals.31 In addition, there are reports of increased tendency among Latine/Hispanic individuals to develop multiple BCCs.32,33

The relationship between UV exposure and KCs could explain the relatively higher incidence in populations with skin of color living in warmer climates, including Hispanic individuals.34 Even so, the development of BCCs appears to correlate directly with the degree of pigmentation in the skin, as it is most common in individuals with lighter skin tones within the Hispanic population.25,34,35 Other risk factors associated with BCC development include albinism, arsenic ingestion, chronic infections, immunosuppression, history of radiation treatment, and history of scars or ulcers due to physical/thermal trauma.35-37

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer among Latine/Hispanic patients. In contrast with NHW patients, evidence supporting the role of UV exposure as a primary risk factor for SCC in patients with skin of color remains limited.25,38 Reports linking UV exposure and KCs in Hispanic and Black individuals predominantly include case series or population-based studies that do not consider levels of UV exposure.25

More recently, genetic ancestry analyses of a large multiethnic cohort found an increased risk for cutaneous SCC among Latine/Hispanic individuals with European ancestry compared to those with Native American or African ancestry; however, these genetic ancestry associations were attenuated (although not eliminated) after considering skin pigmentation (using loci associated with skin pigmentation), history of sun exposure (using actinic keratoses as a covariate for chronic sun exposure), and sun-protected vs sun-exposed anatomic sites, supporting the role of other environmental or sociocultural factors in the development of SCC.39 Similar to BCCs, immunosuppression, chronic scarring, skin irritation, and inflammatory disease also are documented risk factors.9,32

Among NHW individuals with lighter skin tones, SCC characteristically manifests on sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the head and neck region. Typically, a lesion may appear as a scaly erythematous papule or plaque that may be verrucous in nature or a nonhealing bleeding ulcer. In patients with more deeply pigmented skin, SCC tends to develop in the perianal region and on the penis and lower legs; pigmented lesions also may be present (as commonly reported in BCCs).9,32,36

Unfortunately, the lower incidence of KCs and lack of surveillance in populations with skin of color result in a low index of clinical suspicion, leading to delayed diagnoses and increased morbidity.40 Keratinocyte carcinomas are more costly to treat and require more health care resources for Latine/Hispanic and Black patients compared to their NHW counterparts; for example, KCs are associated with more ambulatory visits, more prescription medications, and greater cost on a per-person, per-year basis in Latine/Hispanic and Black patients compared with NHW patients.41 Moreover, a recent multicenter retrospective study found Hispanic patients had 17% larger MMS defects following treatment for KCs compared to NHW patients after adjustment for age, sex, and insurance type.42

Hispanic patients tend to present initially with SCCs in areas associated with advanced disease, such as the anogenital region, penis, and the lower extremities. Latine and Black men have the highest incidence of penile SCC, which is rare with high morbidity and mortality.32,43,44 The higher incidence of penile SCC among Hispanic individuals living in southern states could correspond to circumcision or HPV infection rates,44 ultimately impacting incidence.45

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare locally aggressive cutaneous sarcoma. According to population studies, overall incidence of DFSP is around 4.1 to 4.2 per million in the United States. Population-based studies on DFSP are limited, but available data suggest that Black patients as well as women have the highest incidence.46

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by its capacity to invade surrounding tissues in a tentaclelike pattern.47 This characteristic often leads to inadequate initial resection of the lesion as well as a high recurrence rate despite its low metastatic potential.48 In early stages, DFSP typically manifests as an asymptomatic plaque with a slow growth rate. The color of the lesion ranges from reddish brown to flesh colored. The pigmented form of DFSP, known as Bednar tumor, is the most common among Black patients.47 As the tumor grows, it tends to become firm and nodular. The most common location for

Although current guidelines designate MMS as the first-line treatment for DFSP, the procedure may be inaccessible for certain populations.49 Patients with skin of color are more likely to undergo wide local excision (WLE) than MMS; however, WLE is less effective, with a recurrence rate of 30% compared with 3% in those treated with MMS.50 A retrospective cohort study of more than 2000 patients revealed that Hispanic and Black patients were less likely to undergo MMS. In addition, the authors noted that WLE recipients more commonly were deceased at the end of the study.51

Despite undergoing treatment for a primary DFSP, Hispanic patients also appear to be at increased risk for a second surgery.52 Additional studies are needed to elucidate the reasons behind higher recurrence rates in Latine/Hispanic patients compared to NHW individuals.

Factors Influencing Skin Cancer Outcomes

In recent years, racial and ethnic disparities in health care use, medical treatment, and quality of care among minoritized populations (including Latine/Hispanic groups) have been documented in the medical literature.53,54 These systemic inequities, which are rooted in structural racism,55 have contributed to poorer health outcomes, worse health status, and lower-quality care for minoritized patients living in the United States, including those impacted by dermatologic conditions.8,43,55-57 Becoming familiar with the sociocultural factors influencing skin cancer outcomes in the Latine/Hispanic community (including the lack of or inadequate health insurance, medical mistrust, language, and other cultural elements) and the paucity of research in this domain could help eliminate existing health inequities in this population.

Health Insurance Coverage—Although the uninsured rates in the Latine population have decreased since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (from 30% in 2013 to a low of 19% in 2017),58 inadequate health insurance coverage remains one of the largest barriers to health care access and a contributor to health disparities among the Latine community. Nearly 1 in 5 Latine individuals in the United States are uninsured compared to 8% of NHW individuals.58 Even though Latine individuals are more likely than non-Latine individuals to be part of the workforce, Latine employees are less likely to receive employer-sponsored coverage (27% vs 53% for NHW individuals).59

Not surprisingly, noncitizens are far less likely to be insured; this includes lawfully present immigrants (ie, permanent residents or green card holders, refugees, asylees, and others who are authorized to live in the United States temporarily or permanently) and undocumented immigrants (including individuals who entered the country without authorization and individuals who entered the country lawfully and stayed after their visa or status expired). The higher uninsured rate among noncitizens reflects not only limited access to employer-sponsored coverage but includes immigrant eligibility restrictions for federal programs such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Affordable Care Act Marketplace coverage.60

With approximately 9 million Americans living in mixed-status families (and nearly 10% of babies born each year with at least one undocumented parent), restrictive federal or state health care policies may extend beyond their stated target and impact both Latine citizens and noncitizens.61-65 For instance, Vargas et al64 found that both Latine citizens and noncitizens who lived in states with a high number of immigration-related laws had decreased odds of reporting optimal health as compared to Latine respondents in states with fewer immigration-related laws. Other barriers to enrollment include fears and confusion about program qualification, even if eligible.58

Medical Mistrust and Unfamiliarity—Mistrust of medical professionals has been shown to reduce patient adherence to treatment as prescribed by their medical provider and can negatively influence health outcomes.53 For racial/ethnic minoritized groups (including Latine/Hispanic patients), medical mistrust may be rooted in patients’ experience of discrimination in the health care setting. In a recent cross-sectional study, results from a survey of California adults (including 704 non-Hispanic Black, 711 Hispanic, and 913 NHW adults) found links between levels of medical mistrust and perceived discrimination based on race/ethnicity and language as well as perceived discrimination due to income level and type or lack of insurance.53 Interestingly, discrimination attributed to income level and insurance status remained after controlling for race/ethnicity and language. As expected, patients reliant on public insurance programs such as Medicare have been reported to have greater medical mistrust and suspicion compared with private insurance holders.65 Together, these findings support the notion that individuals who have low socioeconomic status and lack insurance coverage—disproportionately historically marginalized populations—are more likely to perceive discrimination in health care settings, have greater medical mistrust, and experience poorer health outcomes.53

It also is important for health care providers to consider that the US health care system is unfamiliar to many Latine/Hispanic individuals. Costs of medical services tend to be substantially higher in the United States, which can contribute to mistrust in the system.66 In addition, unethical medical experimentations have negatively affected both Latine and especially non-Hispanic Black populations, with long-lasting perceptions of deception and exploitation.67 These beliefs have undermined the trust that these populations have in clinicians and the health care system.54,67

Language and Other Cultural Elements—The inability to effectively communicate with health care providers could contribute to disparities in access to and use of health care services among Latine/Hispanic individuals. In a Medical Expenditure Panel Survey analysis, half of Hispanic patients with limited comfort speaking English did not have a usual source of care, and almost 90% of those with a usual source of care had a provider who spoke Spanish or used interpreters—indicating that few Hispanic individuals with limited comfort speaking English selected a usual source of care without language assistance.68,69 In other examples, language barriers contributed to disparities in cancer screening, and individuals with limited English proficiency were more likely to have difficulty understanding their physician due to language barriers.68,70

Improving cultural misconceptions regarding skin conditions, especially skin cancer, is another important consideration in the Latine/Hispanic community. Many Latine/Hispanic individuals wrongly believe they cannot develop skin cancer due to their darker skin tones and lack of family history.26 Moreover, multiple studies assessing melanoma knowledge and perception among participants with skin of color (including one with an equal number of Latine/Hispanic, Black/African American, and Asian individuals for a total of 120 participants) revealed that many were unaware of the risk for melanoma on acral sites.71 Participants expressed a need for more culturally relevant content from both clinicians and public materials (eg, images of acral melanoma in a person with skin of color).71-73

Paucity of Research—There is limited research regarding skin cancer risks and methods of prevention for patients with skin of color, including the Latine/Hispanic population. Efforts to engage and include patients from these communities, as well as clinicians or investigators from similar backgrounds, in clinical studies are desperately needed. It also is important that clinical studies collect data beyond population descriptors to account for both clinical and genetic variations observed in the Latine/Hispanic population.

Latine/Hispanic individuals are quite diverse with many variable factors that may influence skin cancer outcomes. Often, cancer surveillance data are available in aggregate only, which could mask this heterogeneity.74 Rigorous studies that collect more granular data, including objective measures of skin pigmentation beyond self-reported Fitzpatrick skin type, culture/beliefs, lifestyle/behavior, geographic location, socioeconomic status, genetics, or epigenetics could help fully elucidate skin cancer risks and mitigate health disparities among individuals who identify as part of this population.

Final Thoughts

The Latine/Hispanic community—the largest ethnic minoritized group in the United States—is disproportionately affected by dermatologic health disparities. We hope this review helps to increase recognition of the clinical manifestations of skin cancer in Latine/Hispanic patients. Other factors that may impact skin cancer outcomes in this population include (but are not limited to) lack of or inadequate health insurance, medical mistrust, linguistic barriers and/or individual/cultural perspectives, along with limited research. Recognizing and addressing these (albeit complex) barriers that contribute to the inequitable access to health care in this population remains a critical step toward improving skin cancer outcomes.

- Noe-Bustamnate L, Lopez MH, Krogstad JM. US Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. July 7, 2020. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/07/07/u-s-hispanic-population-surpassed-60-million-in-2019-but-growth-has-slowed/

- Frank C, Lopez MH. Hispanic Americans’ trust in and engagement with science. Pew Research Center. June 14, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/06/PS_2022.06.14_hispanic-americans-science_REPORT.pdf

- US Census Bureau. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. US Government Printing Office; 2015. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

- Zong J. A mosaic, not a monolith: a profile of the U.S. Latino population, 2000-2020. October 26, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://latino.ucla.edu/research/latino-population-2000-2020/

- Latinos in California, Texas, New York, Florida and New Jersey. Pew Research Center. March 19, 2004. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2004/03/19/latinos-in-california-texas-new-york-florida-and-new-jersey/

- Pinheiro PS, Sherman RL, Trapido EJ, et al. Cancer incidence in first generation US Hispanics: Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and new Latinos. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2162-2169.

- Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Kobetz EN. Disaggregated Hispanic groups and cancer: importance, methodology, and current knowledge. In: Ramirez AG, Trapido EJ, eds. Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos. Springer; 2020:17-34.

- Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593.

- Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

- Cruzval-O’Reilly E, Lugo-Somolinos A. Melanoma in Hispanics: we may have it all wrong. Cutis. 2020;106:28-30.

- Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine—a time for reckoning with racism. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:474-480.

- Lopez MH, Krogstad JM, Passel JS. Who is Hispanic? September 5, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/09/05/who-is-hispanic/

- Carrasquillo OY, Lambert J, Merritt BG. Comment on “Disparities in nonmelanoma skin cancer in Hispanic/Latino patients based on Mohs micrographic surgery defect size: a multicenter retrospective study.”J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:E129-E130.

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. Updated January 17, 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- National Cancer Institute. Melanoma of the skin: recent trends in SEER age-adjusted incidence rates, 2000-2021. Updated June 27, 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.htmlsite=53&data_type=1&graph_type=2&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=6&age_range=1&stage=101&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=0&advopt_display=2

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801.

- Bristow IR, de Berker DA, Acland KM, et al. Clinical guidelines for the recognition of melanoma of the foot and nail unit. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010;3:25.

- Fernandez JM, Mata EM, Behbahani S, et al. Survival of Hispanic patients with cutaneous melanoma: a retrospective cohort analysis of 6016 cases from the National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1135-1138.

- Hu S, Sherman R, Arheart K, et al. Predictors of neighborhood risk for late-stage melanoma: addressing disparities through spatial analysis and area-based measures. J Investigative Dermatol. 2014;134:937-945.

- Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, et al. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:771-779.

- Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, et al. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:222-231.

- Weiss J, Kirsner RS, Hu S. Trends in primary skin cancer prevention among US Hispanics: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:580-586.

- Carvalho LAD, Aguiar FC, Smalley KSM, et al. Acral melanoma: new insights into the immune and genomic landscape. Neoplasia. 2023;46:100947.

- Kolitz E, Lopes F, Arffa M, et al. UV Exposure and the risk of keratinocyte carcinoma in skin of color: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:542-546.

- Lukowiak TM, Aizman L, Perz A, et al. Association of age, sex, race, and geographic region with variation of the ratio of basal cell to cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1192-1198.

- Basset-Seguin N, Herms F. Update in the management of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00140.

- McDaniel B, Badri T, Steele RB. Basal cell carcinoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 13, 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: what’s new under the sun. Photochem Photobiol. 2010;86:481-491.

- Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24.

- Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(5 pt 1):751-752.

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, et al. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:903-910.

- Byrd-Miles K, Toombs EL, Peck GL. Skin cancer in individuals of African, Asian, Latin-American, and American-Indian descent: differences in incidence, clinical presentation, and survival compared to Caucasians. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:10-16.

- Rivas M, Rojas E, Calaf GM, et al. Association between non-melanoma and melanoma skin cancer rates, vitamin D and latitude. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:3787-3792.

- Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

- Davis DS, Robinson C, Callender VD. Skin cancer in women of color: epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical manifestations. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:127-134.

- Maafs E, De la Barreda F, Delgado R, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of trunk and extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:622-628.

- Munjal A, Ferguson N. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:481-489.

- Jorgenson E, Choquet H, Yin J, et al. Genetic ancestry, skin pigmentation, and the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic white populations. Commun Biol. 2020;3:765.

- Soliman YS, Mieczkowska K, Zhu TR, et al. Characterizing basal cell carcinoma in Hispanic individuals undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery: a 7-year retrospective review at an academic institution in the Bronx. Brit J Dermatol. 2022;187:597-599.

- Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378.

- Blumenthal LY, Arzeno J, Syder N, et al. Disparities in nonmelanoma skin cancer in Hispanic/Latino patients based on Mohs micrographic surgery defect size: a multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:353-358.

- Slopnick EA, Kim SP, Kiechle JE, et al. Racial disparities differ for African Americans and Hispanics in the diagnosis and treatment of penile cancer. Urology. 2016;96:22-28.

- Goodman MT, Hernandez BY, Shvetsov YB. Demographic and pathologic differences in the incidence of invasive penile cancer in the United States, 1995-2003. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1833-1839.

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Maness SB. Social determinants of health and human papillomavirus vaccination among young adults, National Health Interview Survey 2016. J Community Health. 2019;44:149-158.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Mosallaei D, Lee EB, Lobl M, et al. Rare cutaneous malignancies in skin of color. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:606-612.

- Criscito MC, Martires KJ, Stein JA. Prognostic factors, treatment, and survival in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1365-1371.

- Orenstein LAV, Nelson MM, Wolner Z, et al. Differences in outpatient dermatology encounter work relative value units and net payments by patient race, sex, and age. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:406-412.

- Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, et al. A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with long-term follow-up: the Mayo Clinic experience. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:98-106.

- Moore KJ, Chang MS, Weiss J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the surgical treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:245-247.

- Trofymenko O, Bordeaux JS, Zeitouni NC. Survival in patients with primary dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: National Cancer Database analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1125-1134.

- Bazargan M, Cobb S, Assari S. Discrimination and medical mistrust in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of California adults. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19:4-15.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC; 2003.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453-1463.

- Tackett KJ, Jenkins F, Morrell DS, et al. Structural racism and its influence on the severity of atopic dermatitis in African American children. Pediatric Dermatol. 2020;37:142-146.

- Greif C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. A retrospective cohort study of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans at a large metropolitan academic center. JAAD Int. 2022;6:104-106.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health insurance coverage and access to care among Latinos: recent rrends and key challenges (HP-2021-22). October 8, 2021. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-insurance-coverage-access-care-among-latinos

- Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch LN. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2020 (Current Population Reports No. P60-274). US Census Bureau; 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-274.pdf

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts on health coverage of immigrants. Updated June 26, 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/key-facts-on-health-coverage-of-immigrants/

- Pew Research Center. Unauthorized immigrants: length of residency, patterns of parenthood. Published December 1, 2011. Accessed October 28, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2011/12/01/unauthorized-immigrants-length-of-residency-patterns-of-parenthood/

- Schneider J, Schmitt M. Understanding the relationship between racial discrimination and mental health among African American adults: a review. SAGE Open. 2015;5:1-10.

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:29-38.

- Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, Juarez M. The impact of punitive immigrant laws on the health of Latina/o Populations. Polit Policy. 2017;45:312-337.

- Sutton AL, He J, Edmonds MC, et al. Medical mistrust in Black breast cancer patients: acknowledging the roles of the trustor and the trustee. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34:600-607.

- Jacobs J. An overview of Latin American healthcare systems. Pacific Prime Latin America. July 31, 2023. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.pacificprime.lat/blog/an-overview-of-latin-american-healthcare-systems/

- CDC. Unfair and unjust practices and conditions harm Hispanic and Latino people and drive health disparities. May 15, 2024. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco-health-equity/collection/hispanic-latino-unfair-and-unjust.html

- Hall IJ, Rim SH, Dasari S. Preventive care use among Hispanic adults with limited comfort speaking English: an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data. Prev Med. 2022;159:107042.

- Brach C, Chevarley FM. Demographics and health care access and utilization of limited-English-proficient and English-proficient Hispanics. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2008. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications//rf28/rf28.pdf

- Berdahl TA, Kirby JB. Patient-provider communication disparities by limited English proficiency (LEP): trends from the US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2006-2015. J General Intern Med. 2019;34:1434-1440.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

- Robinson JK, Nodal M, Chavez L, et al. Enhancing the relevance of skin self-examination for Latinos. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:717-718.

- Buchanan Lunsford N, Berktold J, Holman DM, et al. Skin cancer knowledge, awareness, beliefs and preventive behaviors among black and hispanic men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:203-209.

- Madrigal JM, Correa-Mendez M, Arias JD, et al. Hispanic, Latino/a, Latinx, Latine: disentangling the identities of Hispanic/Latino Americans. National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics. October 20, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2024. https://dceg.cancer.gov/about/diversity-inclusion/inclusivity-minute/2022/disentangling-identities-hispanic-latino-americans

The Latine/Hispanic population in the United States comprises one of the largest and youngest skin of color communities.1,2 In 2020, this group accounted for 19% of all Americans—a percentage expected to increase to more than 25% by 2060.3

It must be emphasized that the Latine/Hispanic community in the United States is incredibly diverse.4 Approximately one-third of individuals in this group are foreign-born, and this community is made up of people from all racialized groups, religions, languages, and cultural identities.2 The heterogeneity of the Latine/Hispanic population translates into a wide representation of skin tones, reflecting a rich range of ancestries, ethnicities, and cultures. The percentage of individuals from each origin group may differ according to where they live in the United States; for instance, individuals who identify as Mexican comprise more than 80% of the Latine/Hispanic population in both Texas and California but only 17% in Florida, where more than half of Latine/Hispanic people identify as Cuban or Puerto Rican.4,5 As a result, when it comes to skin cancer epidemiology, variations in incidence and mortality may exist within each of these subgroups who identify as part of the Latine/Hispanic community, as reported for other cancers.6,7 Further research is needed to investigate these potential differences.Unfortunately, considerable health disparities persist among this rapidly growing population, including increased morbidity and mortality from melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) despite overall low lifetime incidence.8,9 In this review, the epidemiology, clinical manifestation, and ethnic disparities for skin cancer among the US Latine/Hispanic population are summarized; other factors impacting overall health and health care, including sociocultural factors, also are briefly discussed.

Terminology

Before a meaningful dialogue can be had about skin cancer in the Latine/Hispanic population, it is important to contextualize the terms used to identify this patient population, including Latino/Latine and Hispanic. In the early 1970s, the United States adopted the term Hispanic as a way of conglomerating Spanish-speaking individuals from Spain, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The goal was to implement a common identifier that enabled the US government to study the economic and social development of these groups.10 Nevertheless, considerable differences (eg, variations in skin pigmentation, sun sensitivity) exist among Hispanic communities, with some having stronger European, African, or Amerindian influences due to colonization of their distinct countries.11

In contrast, Latino is a geographic term and refers to people with roots in Latin America and the Caribbean (Table 1).12,13 For example, a person from Brazil may be considered Latino but not Hispanic as Brazilians speak Portuguese; alternatively, Spaniards (who are considered Hispanic) are not Latino because Spain is not a Latin American country. A person from Mexico would be considered both Latino and Hispanic.13

More recently, the term Latine has been introduced as an alternative to the gender binary inherent in the Spanish language.12 For the purposes of this article, the terms Latine and Hispanic will be used interchangeably (unless otherwise specified) depending on how they are cited in the existing literature. Furthermore, the term non-Hispanic White (NHW) will be used to refer to individuals who have been socially ascribed or who self-identify as White in terms of race or ethnicity.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is more likely to metastasize compared to other forms of skin cancer, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). For Latine/Hispanic individuals living in the United States, the lifetime risk for melanoma is 1 in 200 compared to 1 in 33 for NHW individuals.14 While the lifetime risk for melanoma is low for the Latine/Hispanic population, Hispanic individuals are diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age (mean, 56 years), and the rate of new cases is marginally higher for women (4.9 per 100,000) compared to men (4.8 per 100,000).15,16

Typical sites of melanoma manifestation in Latine/Hispanic individuals include the torso (most common site in Hispanic men), lower extremities (most common site in Hispanic women), and acral sites (palms, soles, and nails).9,16,17 Anatomic location also can vary according to age for both men and women. For men, the incidence of melanoma on the trunk appears to decrease with age, while the incidence on the head and neck may increase. For women, the incidence of melanoma on the lower extremities and hip increases with age. Cutaneous melanoma may manifest as a lesion with asymmetry, irregular borders, variation in pigmentation, large diameter (>6 mm), and evolution over time. In patients with skin of color, melanoma easily can be missed, as it also typically mimics more benign skin conditions and may develop from an existing black- or dark brown–pigmented macule.18 The most common histologic subtype reported among Latine/Hispanic individuals in the United States is superficial spreading melanoma (20%–23%) followed by nodular melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma.16,19 Until additional risk factors associated with melanoma susceptibility in Hispanic/Latine people are better elucidated, it may be appropriate to use an alternative acronym, such as CUBED (Table 2), in addition to the standard ABCDE system to help recognize potential melanoma on acral sites.18

Although the lifetime risk for melanoma among Hispanic individuals in the United States is lower than that for NHW individuals, Hispanic patients who are diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with increased tumor thickness and later-stage diagnosis compared to NHW individuals.8,16,20 In a recent study by Qian et al,8 advanced stage melanoma—defined as regional or distant stage disease—was present in 12.6% of NHW individuals. In contrast, the percentage of Hispanics with advanced disease was higher at 21%.8 Even after controlling for insurance and poverty status, Hispanic individuals were at greater risk than NHW individuals for late-stage diagnosis.16,20

Morbidity and mortality also have been shown to be higher in Hispanic patients with cutaneous melanoma.9,17 Reasons for this are multifactorial, with studies specific to melanoma citing challenges associated with early detection in individuals with deeply pigmented skin, a lack of awareness and knowledge about skin cancer among Latine/Hispanic patients, and treatment disparities.21-23 Moreover, very few studies have reported comprehensive data on patients from Africa and Latin America. Studies examining the role of genetic ancestry, epigenetic variants, and skin pigmentation and the risk for melanoma among the Latine/Hispanic population therefore are much needed.24

Keratinocyte Carcinomas

Keratinocyte carcinomas, also known as nonmelanoma skin cancers, include BCC and SCC. In comparison to the high-quality data available for melanoma from cancer registries, there are less reliable incidence data for KCs, especially among individuals with skin of color.25 As a result, KC epidemiology in the United States is drawn largely from case series (especially for individuals with skin of color) or claims data from small data sets often from geographically restricted regions within the United States.25,26

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant skin cancer in Latine/Hispanic individuals. Among those with lighter skin tones, the lifetime risk for BCC is about 30%.27,28 Men typically are affected at a higher rate than women, and the median age for diagnosis is 68 years.29 The development of BCC primarily is linked to lifetime accumulated UV radiation exposure. Even though BCC has a low mortality rate, it can lead to substantial morbidity due to factors such as tumor location, size, and rate of invasion, resulting in cosmetic and functional issues. Given its low metastatic potential, treatment of BCC typically is aimed at local control.30 Options for treatment include Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), curettage and electrodessication, cryosurgery, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, and topical therapies. Systemic therapies are reserved for patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease.30

Latine/Hispanic patients characteristically present with BCCs on sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the head and neck region. In most patients, BCC manifests as a translucent pearly nodule with superficial telangiectasias and/or a nonhealing ulcer with a central depression and rolled nontender borders. However, in patients with skin of color, 66% of BCCs manifest with pigmentation; in fact, pigmented BCC (a subtype of BCC) has been shown to have a higher prevalence among Hispanic individuals, with an incidence twice as frequent as in NHW individuals.31 In addition, there are reports of increased tendency among Latine/Hispanic individuals to develop multiple BCCs.32,33

The relationship between UV exposure and KCs could explain the relatively higher incidence in populations with skin of color living in warmer climates, including Hispanic individuals.34 Even so, the development of BCCs appears to correlate directly with the degree of pigmentation in the skin, as it is most common in individuals with lighter skin tones within the Hispanic population.25,34,35 Other risk factors associated with BCC development include albinism, arsenic ingestion, chronic infections, immunosuppression, history of radiation treatment, and history of scars or ulcers due to physical/thermal trauma.35-37

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer among Latine/Hispanic patients. In contrast with NHW patients, evidence supporting the role of UV exposure as a primary risk factor for SCC in patients with skin of color remains limited.25,38 Reports linking UV exposure and KCs in Hispanic and Black individuals predominantly include case series or population-based studies that do not consider levels of UV exposure.25

More recently, genetic ancestry analyses of a large multiethnic cohort found an increased risk for cutaneous SCC among Latine/Hispanic individuals with European ancestry compared to those with Native American or African ancestry; however, these genetic ancestry associations were attenuated (although not eliminated) after considering skin pigmentation (using loci associated with skin pigmentation), history of sun exposure (using actinic keratoses as a covariate for chronic sun exposure), and sun-protected vs sun-exposed anatomic sites, supporting the role of other environmental or sociocultural factors in the development of SCC.39 Similar to BCCs, immunosuppression, chronic scarring, skin irritation, and inflammatory disease also are documented risk factors.9,32

Among NHW individuals with lighter skin tones, SCC characteristically manifests on sun-exposed areas of the skin such as the head and neck region. Typically, a lesion may appear as a scaly erythematous papule or plaque that may be verrucous in nature or a nonhealing bleeding ulcer. In patients with more deeply pigmented skin, SCC tends to develop in the perianal region and on the penis and lower legs; pigmented lesions also may be present (as commonly reported in BCCs).9,32,36

Unfortunately, the lower incidence of KCs and lack of surveillance in populations with skin of color result in a low index of clinical suspicion, leading to delayed diagnoses and increased morbidity.40 Keratinocyte carcinomas are more costly to treat and require more health care resources for Latine/Hispanic and Black patients compared to their NHW counterparts; for example, KCs are associated with more ambulatory visits, more prescription medications, and greater cost on a per-person, per-year basis in Latine/Hispanic and Black patients compared with NHW patients.41 Moreover, a recent multicenter retrospective study found Hispanic patients had 17% larger MMS defects following treatment for KCs compared to NHW patients after adjustment for age, sex, and insurance type.42

Hispanic patients tend to present initially with SCCs in areas associated with advanced disease, such as the anogenital region, penis, and the lower extremities. Latine and Black men have the highest incidence of penile SCC, which is rare with high morbidity and mortality.32,43,44 The higher incidence of penile SCC among Hispanic individuals living in southern states could correspond to circumcision or HPV infection rates,44 ultimately impacting incidence.45

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare locally aggressive cutaneous sarcoma. According to population studies, overall incidence of DFSP is around 4.1 to 4.2 per million in the United States. Population-based studies on DFSP are limited, but available data suggest that Black patients as well as women have the highest incidence.46

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by its capacity to invade surrounding tissues in a tentaclelike pattern.47 This characteristic often leads to inadequate initial resection of the lesion as well as a high recurrence rate despite its low metastatic potential.48 In early stages, DFSP typically manifests as an asymptomatic plaque with a slow growth rate. The color of the lesion ranges from reddish brown to flesh colored. The pigmented form of DFSP, known as Bednar tumor, is the most common among Black patients.47 As the tumor grows, it tends to become firm and nodular. The most common location for

Although current guidelines designate MMS as the first-line treatment for DFSP, the procedure may be inaccessible for certain populations.49 Patients with skin of color are more likely to undergo wide local excision (WLE) than MMS; however, WLE is less effective, with a recurrence rate of 30% compared with 3% in those treated with MMS.50 A retrospective cohort study of more than 2000 patients revealed that Hispanic and Black patients were less likely to undergo MMS. In addition, the authors noted that WLE recipients more commonly were deceased at the end of the study.51

Despite undergoing treatment for a primary DFSP, Hispanic patients also appear to be at increased risk for a second surgery.52 Additional studies are needed to elucidate the reasons behind higher recurrence rates in Latine/Hispanic patients compared to NHW individuals.

Factors Influencing Skin Cancer Outcomes

In recent years, racial and ethnic disparities in health care use, medical treatment, and quality of care among minoritized populations (including Latine/Hispanic groups) have been documented in the medical literature.53,54 These systemic inequities, which are rooted in structural racism,55 have contributed to poorer health outcomes, worse health status, and lower-quality care for minoritized patients living in the United States, including those impacted by dermatologic conditions.8,43,55-57 Becoming familiar with the sociocultural factors influencing skin cancer outcomes in the Latine/Hispanic community (including the lack of or inadequate health insurance, medical mistrust, language, and other cultural elements) and the paucity of research in this domain could help eliminate existing health inequities in this population.

Health Insurance Coverage—Although the uninsured rates in the Latine population have decreased since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (from 30% in 2013 to a low of 19% in 2017),58 inadequate health insurance coverage remains one of the largest barriers to health care access and a contributor to health disparities among the Latine community. Nearly 1 in 5 Latine individuals in the United States are uninsured compared to 8% of NHW individuals.58 Even though Latine individuals are more likely than non-Latine individuals to be part of the workforce, Latine employees are less likely to receive employer-sponsored coverage (27% vs 53% for NHW individuals).59

Not surprisingly, noncitizens are far less likely to be insured; this includes lawfully present immigrants (ie, permanent residents or green card holders, refugees, asylees, and others who are authorized to live in the United States temporarily or permanently) and undocumented immigrants (including individuals who entered the country without authorization and individuals who entered the country lawfully and stayed after their visa or status expired). The higher uninsured rate among noncitizens reflects not only limited access to employer-sponsored coverage but includes immigrant eligibility restrictions for federal programs such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Affordable Care Act Marketplace coverage.60

With approximately 9 million Americans living in mixed-status families (and nearly 10% of babies born each year with at least one undocumented parent), restrictive federal or state health care policies may extend beyond their stated target and impact both Latine citizens and noncitizens.61-65 For instance, Vargas et al64 found that both Latine citizens and noncitizens who lived in states with a high number of immigration-related laws had decreased odds of reporting optimal health as compared to Latine respondents in states with fewer immigration-related laws. Other barriers to enrollment include fears and confusion about program qualification, even if eligible.58

Medical Mistrust and Unfamiliarity—Mistrust of medical professionals has been shown to reduce patient adherence to treatment as prescribed by their medical provider and can negatively influence health outcomes.53 For racial/ethnic minoritized groups (including Latine/Hispanic patients), medical mistrust may be rooted in patients’ experience of discrimination in the health care setting. In a recent cross-sectional study, results from a survey of California adults (including 704 non-Hispanic Black, 711 Hispanic, and 913 NHW adults) found links between levels of medical mistrust and perceived discrimination based on race/ethnicity and language as well as perceived discrimination due to income level and type or lack of insurance.53 Interestingly, discrimination attributed to income level and insurance status remained after controlling for race/ethnicity and language. As expected, patients reliant on public insurance programs such as Medicare have been reported to have greater medical mistrust and suspicion compared with private insurance holders.65 Together, these findings support the notion that individuals who have low socioeconomic status and lack insurance coverage—disproportionately historically marginalized populations—are more likely to perceive discrimination in health care settings, have greater medical mistrust, and experience poorer health outcomes.53

It also is important for health care providers to consider that the US health care system is unfamiliar to many Latine/Hispanic individuals. Costs of medical services tend to be substantially higher in the United States, which can contribute to mistrust in the system.66 In addition, unethical medical experimentations have negatively affected both Latine and especially non-Hispanic Black populations, with long-lasting perceptions of deception and exploitation.67 These beliefs have undermined the trust that these populations have in clinicians and the health care system.54,67

Language and Other Cultural Elements—The inability to effectively communicate with health care providers could contribute to disparities in access to and use of health care services among Latine/Hispanic individuals. In a Medical Expenditure Panel Survey analysis, half of Hispanic patients with limited comfort speaking English did not have a usual source of care, and almost 90% of those with a usual source of care had a provider who spoke Spanish or used interpreters—indicating that few Hispanic individuals with limited comfort speaking English selected a usual source of care without language assistance.68,69 In other examples, language barriers contributed to disparities in cancer screening, and individuals with limited English proficiency were more likely to have difficulty understanding their physician due to language barriers.68,70

Improving cultural misconceptions regarding skin conditions, especially skin cancer, is another important consideration in the Latine/Hispanic community. Many Latine/Hispanic individuals wrongly believe they cannot develop skin cancer due to their darker skin tones and lack of family history.26 Moreover, multiple studies assessing melanoma knowledge and perception among participants with skin of color (including one with an equal number of Latine/Hispanic, Black/African American, and Asian individuals for a total of 120 participants) revealed that many were unaware of the risk for melanoma on acral sites.71 Participants expressed a need for more culturally relevant content from both clinicians and public materials (eg, images of acral melanoma in a person with skin of color).71-73

Paucity of Research—There is limited research regarding skin cancer risks and methods of prevention for patients with skin of color, including the Latine/Hispanic population. Efforts to engage and include patients from these communities, as well as clinicians or investigators from similar backgrounds, in clinical studies are desperately needed. It also is important that clinical studies collect data beyond population descriptors to account for both clinical and genetic variations observed in the Latine/Hispanic population.

Latine/Hispanic individuals are quite diverse with many variable factors that may influence skin cancer outcomes. Often, cancer surveillance data are available in aggregate only, which could mask this heterogeneity.74 Rigorous studies that collect more granular data, including objective measures of skin pigmentation beyond self-reported Fitzpatrick skin type, culture/beliefs, lifestyle/behavior, geographic location, socioeconomic status, genetics, or epigenetics could help fully elucidate skin cancer risks and mitigate health disparities among individuals who identify as part of this population.

Final Thoughts

The Latine/Hispanic community—the largest ethnic minoritized group in the United States—is disproportionately affected by dermatologic health disparities. We hope this review helps to increase recognition of the clinical manifestations of skin cancer in Latine/Hispanic patients. Other factors that may impact skin cancer outcomes in this population include (but are not limited to) lack of or inadequate health insurance, medical mistrust, linguistic barriers and/or individual/cultural perspectives, along with limited research. Recognizing and addressing these (albeit complex) barriers that contribute to the inequitable access to health care in this population remains a critical step toward improving skin cancer outcomes.

The Latine/Hispanic population in the United States comprises one of the largest and youngest skin of color communities.1,2 In 2020, this group accounted for 19% of all Americans—a percentage expected to increase to more than 25% by 2060.3

It must be emphasized that the Latine/Hispanic community in the United States is incredibly diverse.4 Approximately one-third of individuals in this group are foreign-born, and this community is made up of people from all racialized groups, religions, languages, and cultural identities.2 The heterogeneity of the Latine/Hispanic population translates into a wide representation of skin tones, reflecting a rich range of ancestries, ethnicities, and cultures. The percentage of individuals from each origin group may differ according to where they live in the United States; for instance, individuals who identify as Mexican comprise more than 80% of the Latine/Hispanic population in both Texas and California but only 17% in Florida, where more than half of Latine/Hispanic people identify as Cuban or Puerto Rican.4,5 As a result, when it comes to skin cancer epidemiology, variations in incidence and mortality may exist within each of these subgroups who identify as part of the Latine/Hispanic community, as reported for other cancers.6,7 Further research is needed to investigate these potential differences.Unfortunately, considerable health disparities persist among this rapidly growing population, including increased morbidity and mortality from melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) despite overall low lifetime incidence.8,9 In this review, the epidemiology, clinical manifestation, and ethnic disparities for skin cancer among the US Latine/Hispanic population are summarized; other factors impacting overall health and health care, including sociocultural factors, also are briefly discussed.

Terminology

Before a meaningful dialogue can be had about skin cancer in the Latine/Hispanic population, it is important to contextualize the terms used to identify this patient population, including Latino/Latine and Hispanic. In the early 1970s, the United States adopted the term Hispanic as a way of conglomerating Spanish-speaking individuals from Spain, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The goal was to implement a common identifier that enabled the US government to study the economic and social development of these groups.10 Nevertheless, considerable differences (eg, variations in skin pigmentation, sun sensitivity) exist among Hispanic communities, with some having stronger European, African, or Amerindian influences due to colonization of their distinct countries.11

In contrast, Latino is a geographic term and refers to people with roots in Latin America and the Caribbean (Table 1).12,13 For example, a person from Brazil may be considered Latino but not Hispanic as Brazilians speak Portuguese; alternatively, Spaniards (who are considered Hispanic) are not Latino because Spain is not a Latin American country. A person from Mexico would be considered both Latino and Hispanic.13

More recently, the term Latine has been introduced as an alternative to the gender binary inherent in the Spanish language.12 For the purposes of this article, the terms Latine and Hispanic will be used interchangeably (unless otherwise specified) depending on how they are cited in the existing literature. Furthermore, the term non-Hispanic White (NHW) will be used to refer to individuals who have been socially ascribed or who self-identify as White in terms of race or ethnicity.

Melanoma

Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is more likely to metastasize compared to other forms of skin cancer, including basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). For Latine/Hispanic individuals living in the United States, the lifetime risk for melanoma is 1 in 200 compared to 1 in 33 for NHW individuals.14 While the lifetime risk for melanoma is low for the Latine/Hispanic population, Hispanic individuals are diagnosed with melanoma at an earlier age (mean, 56 years), and the rate of new cases is marginally higher for women (4.9 per 100,000) compared to men (4.8 per 100,000).15,16

Typical sites of melanoma manifestation in Latine/Hispanic individuals include the torso (most common site in Hispanic men), lower extremities (most common site in Hispanic women), and acral sites (palms, soles, and nails).9,16,17 Anatomic location also can vary according to age for both men and women. For men, the incidence of melanoma on the trunk appears to decrease with age, while the incidence on the head and neck may increase. For women, the incidence of melanoma on the lower extremities and hip increases with age. Cutaneous melanoma may manifest as a lesion with asymmetry, irregular borders, variation in pigmentation, large diameter (>6 mm), and evolution over time. In patients with skin of color, melanoma easily can be missed, as it also typically mimics more benign skin conditions and may develop from an existing black- or dark brown–pigmented macule.18 The most common histologic subtype reported among Latine/Hispanic individuals in the United States is superficial spreading melanoma (20%–23%) followed by nodular melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma.16,19 Until additional risk factors associated with melanoma susceptibility in Hispanic/Latine people are better elucidated, it may be appropriate to use an alternative acronym, such as CUBED (Table 2), in addition to the standard ABCDE system to help recognize potential melanoma on acral sites.18

Although the lifetime risk for melanoma among Hispanic individuals in the United States is lower than that for NHW individuals, Hispanic patients who are diagnosed with melanoma are more likely to present with increased tumor thickness and later-stage diagnosis compared to NHW individuals.8,16,20 In a recent study by Qian et al,8 advanced stage melanoma—defined as regional or distant stage disease—was present in 12.6% of NHW individuals. In contrast, the percentage of Hispanics with advanced disease was higher at 21%.8 Even after controlling for insurance and poverty status, Hispanic individuals were at greater risk than NHW individuals for late-stage diagnosis.16,20

Morbidity and mortality also have been shown to be higher in Hispanic patients with cutaneous melanoma.9,17 Reasons for this are multifactorial, with studies specific to melanoma citing challenges associated with early detection in individuals with deeply pigmented skin, a lack of awareness and knowledge about skin cancer among Latine/Hispanic patients, and treatment disparities.21-23 Moreover, very few studies have reported comprehensive data on patients from Africa and Latin America. Studies examining the role of genetic ancestry, epigenetic variants, and skin pigmentation and the risk for melanoma among the Latine/Hispanic population therefore are much needed.24

Keratinocyte Carcinomas

Keratinocyte carcinomas, also known as nonmelanoma skin cancers, include BCC and SCC. In comparison to the high-quality data available for melanoma from cancer registries, there are less reliable incidence data for KCs, especially among individuals with skin of color.25 As a result, KC epidemiology in the United States is drawn largely from case series (especially for individuals with skin of color) or claims data from small data sets often from geographically restricted regions within the United States.25,26