User login

Does Exercise Reduce Cancer Risk? It’s Just Not That Simple

“Exercise is medicine” has become something of a mantra, with good reason. There’s no doubt that regular physical activity has a broad range of health benefits. Exercise can improve circulation, help control weight, reduce stress, and boost mood — take your pick.

Lower cancer risk is also on the list — with exercise promoted as a risk-cutting strategy in government guidelines and in recommendations from professional groups such as the American Cancer Society.

The bulk of the data hangs on less rigorous, observational studies that have linked physical activity to lower risks for certain cancers, but plenty of questions remain.

What are the cancer types where exercise makes a difference? How significant is that impact? And what, exactly, defines a physical activity pattern powerful enough to move the needle on cancer risk?

Here’s an overview of the state of the evidence.

Exercise and Cancer Types: A Mixed Bag

When it comes to cancer prevention strategies, guidelines uniformly endorse less couch time and more movement. But a deeper look at the science reveals a complex and often poorly understood connection between exercise and cancer risk.

For certain cancer types, the benefits of exercise on cancer risk seem fairly well established.

The latest edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, published in 2018, cites “strong evidence” that regular exercise might curb the risks for breast and colon cancers as well as bladder, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, and gastric cancers. These guidelines also point to “moderate”-strength evidence of a protective association with lung cancer.

The evidence of a protective effect, however, is strongest for breast and colon cancers, said Jennifer Ligibel, MD, senior physician in the Breast Oncology Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, . “But,” she pointed out, “that may be because they’re some of the most common cancers, and it’s been easier to detect an association.”

Guidelines from the American Cancer Society, published in 2020, align with the 2018 recommendations.

“We believe there’s strong evidence to suggest at least eight different types of cancer are associated with physical activity,” said Erika Rees-Punia, PhD, MPH, senior principal scientist, epidemiology and behavioral research at the American Cancer Society.

That view is not universal, however. Current recommendations from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, for example, are more circumspect, citing only three cancers with good evidence of a protective effect from exercise: Breast (postmenopausal), colon, and endometrial.

“We definitely can’t say exercise reduces the risk of all cancers,” said Lee Jones, PhD, head of the Exercise Oncology Program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “The data suggest it’s just not that simple.”

And it’s challenging to put all the evidence together, Dr. Jones added.

The physical activity guidelines are based on published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses of data from observational studies that examined the relationship between physical activity — aerobic exercise, specifically — and cancer incidence. That means the evidence comes with all the limitations observational studies entail, such as how they collect information on participants’ exercise habits — which, Dr. Jones noted, is typically done via “monster questionnaires” that gauge physical activity in broad strokes.

Pooling all those findings into a meta-analysis is tricky, Dr. Jones added, because individual studies vary in important ways — from follow-up periods to how they quantify exercise and track cancer incidence.

In a study published in February in Cancer Cell, Dr. Jones and his colleagues attempted to address some of those issues by leveraging data from the PLCO screening trial.

The PLCO was a prospective study of over 60,000 US adults that compared the effects of annual screening vs usual care on cancer mortality. At enrollment, participants completed questionnaires that included an assessment of “vigorous” exercise. Based on that, Dr. Jones and his colleagues classified 55% as “exercisers” — meaning they reported 2 or more hours of vigorous exercise per week. The remaining 45%, who were in the 0 to 1 hour per week range, were deemed non-exercisers.

Over a median of 18 years, nearly 16,000 first-time invasive cancers were diagnosed, and some interesting differences between exercisers and non-exercisers emerged. The active group had lower risks for three cancers: Head and neck, with a 26% lower risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), lung (a 20% lower risk), and breast (an 11% lower risk).

What was striking, however, was the lack of connection between exercise and many cancers cited in the guidelines, including colon, gastric, bladder, endometrial, and renal cancers.

Perhaps even more surprising — exercisers had higher risks for prostate cancer (12%) and melanoma (20%). This finding, Dr. Jones said, is in line with a previous pooled analysis of data from 12 US and European prospective cohorts. In this study, the most physically active participants (90th percentile) had higher risks for melanoma and prostate cancer, compared with the least active group (10th percentile).

The melanoma findings do make sense, Dr. Jones said, given that highly active people may spend a lot of time in the sun. “My advice,” Dr. Jones said, “is, if you’re exercising outside, wear sunscreen.” The prostate cancer findings, however, are more puzzling and warrant further research, he noted.

But the bottom line is that the relationship between exercise and cancer types is mixed and far from nailed down.

How Big Is the Effect?

Even if exercise reduces the risk for only certain cancers, that’s still important, particularly when those links appear strongest for common cancer types, such as breast and colon.

But how much of a difference can exercise make?

Based on the evidence, it may only be a modest one. A 2019 systematic review by the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee provided a rough estimate: Across hundreds of epidemiological studies, people with the highest physical activity levels had a 10%-20% lower risk for the cancers cited in the 2018 exercise guidelines compared with people who were least active.

These figures, however, are probably an underestimate, said Anne McTiernan, MD, PhD, a member of the advisory committee and professor of epidemiology, at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

“This is what we usually see when a factor is not measured very well,” said Dr. McTiernan, explaining that the individual studies differed in their categories of “highest” and “lowest” physical activity, such that one study’s “highest” could be another’s mid-range.

“In other words, the effects of physical activity are likely larger” than the review found, Dr. McTiernan said.

The next logical question is whether a bigger exercise “dose” — more time or higher intensity — would have a greater impact on cancer risk. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology tried to clarify that by pooling data on over 750,000 participants from nine prospective cohorts.

Overall, people meeting government recommendations for exercise — equivalent to about 2.5-5 hours of weekly moderate activity, such as a brisk walk, or about 1.25-2.5 hours of more vigorous activities, like running — had lower risks for seven of 15 cancer types studied compared with less active people.

For cancers with positive findings, being on the higher end of the recommended 2.5- to 5-hour weekly range was better. Risk reductions for breast cancer, for instance, were 6% at 2.5 hours of physical activity per week and 10% at 5 hours per week. Similar trends emerged for other cancer types, including colon (8%-14%), endometrial (10%-18%), liver cancer (18%-27%), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in women (11%-18%).

But there may be an exercise sweet spot that maximizes the cancer risk benefit.

Among people who surpassed the recommendations — exercising for more time or more intensely — the risk reduction benefit did not necessarily improve in a linear fashion. For certain cancer types, such as colon and endometrial, the benefits of more vigorous exercise “eroded at higher levels of activity,” the authors said.

The issue here is that most studies have not dug deeply into aerobic exercise habits. Often, studies present participants with a list of activities — walking, biking, and running — and ask them to estimate how often and for what duration they do each.

Plus, “we’ve usually lumped moderate and vigorous activities together,” Dr. Rees-Punia said, which means there’s a lack of “granular data” to say whether certain intensities or frequencies of exercise are optimal and for whom.

Why Exercise May Lower Cancer Risk

Exercise habits do not, of course, exist in a vacuum. Highly active people, Dr. Ligibel said, tend to be of higher socioeconomic status, leaner, and have generally healthier lifestyles than sedentary people.

Body weight is a big confounder as well. However, Dr. Rees-Punia noted, it’s also probably a reason that exercise is linked to lower cancer risks, particularly by preventing weight gain. Still, studies have found that the association between exercise and many cancers remains significant after adjusting for body mass index.

The why remains unclear, though some studies offer clues.

“There’s been some really interesting mechanistic research, suggesting that exercise may help inhibit tumor growth or upregulate the immune system,” Dr. Ligibel said.

That includes not only lab research but small intervention studies. While these studies have largely involved people who already have cancer, some have also focused on healthy individuals.

A 2019 study from Dr. Ligibel and her colleagues, which randomly assigned 49 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer to start either an exercise program or mind-body practices ahead of surgery, found exercisers, who had been active for about a month at the time of surgery, showed signs of immune system upregulation in their tumors, while the control group did not.

Among healthy postmenopausal women, a meta-analysis of six clinical trials from Dr. McTiernan and her colleagues found that exercise plus calorie reduction can reduce levels of breast cancer-related endogenous hormones, more so than calorie-cutting alone. And a 2023 study found that high-intensity exercise boosted the ranks of certain immune cells and reduced inflammation in the colon among people at high risk for colon and endometrial cancers due to Lynch syndrome.

Defining an Exercise ‘Prescription’

Despite the gaps and uncertainties in the research, government guidelines as well as those from the American Cancer Society and other medical groups are in lockstep in their exercise recommendations: Adults should strive for 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (like brisk walking), 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity (like running), or some combination each week.

The guidelines also encourage strength training twice a week — advice that’s based on research tying those activity levels to lower risks for heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

But there’s no “best” exercise prescription for lowering cancer risk specifically. Most epidemiological studies have examined only aerobic activity, Dr. Rees-Punia said, and there’s very little known about whether strength conditioning or other moderate heart rate-elevating activities, such as daily household chores, may reduce the risk for cancer.

Given the lack of nuance in the literature, it’s hard to say what intensities, types, or amounts of exercise are best for each individual.

Going forward, device-based measurements of physical activity could “help us sort out the effects of different intensities of exercise and possibly types,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

But overall, Dr. McTiernan said, the data do show that the risks for several cancers are lower at the widely recommended activity levels.

“The bottom-line advice is still to exercise at least 150 minutes per week at a moderate-intensity level or greater,” Dr. McTiernan said.

Or put another way, moving beats being sedentary. It’s probably wise for everyone to sit less, noted Dr. Rees-Punia, for overall health and based on evidence tying sedentary time to the risks for certain cancers, including colon, endometrial, and lung.

There’s a practical element to consider in all of this: What physical activities will people actually do on the regular? In the big epidemiological studies, Dr. McTiernan noted, middle-aged and older adults most often report walking, suggesting that’s the preferred, or most accessible activity, for many.

“You can only benefit from the physical activity you’ll actually do,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

Dr. Ligibel echoed that sentiment, saying she encourages patients to think about physical activity as a process: “You need to find things you like to do and work them into your daily life, in a sustainable way.

“People often talk about exercise being medicine,” Dr. Ligibel said. “But I think you could take that too far. If we get too prescriptive about it, that could take the joy away.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Exercise is medicine” has become something of a mantra, with good reason. There’s no doubt that regular physical activity has a broad range of health benefits. Exercise can improve circulation, help control weight, reduce stress, and boost mood — take your pick.

Lower cancer risk is also on the list — with exercise promoted as a risk-cutting strategy in government guidelines and in recommendations from professional groups such as the American Cancer Society.

The bulk of the data hangs on less rigorous, observational studies that have linked physical activity to lower risks for certain cancers, but plenty of questions remain.

What are the cancer types where exercise makes a difference? How significant is that impact? And what, exactly, defines a physical activity pattern powerful enough to move the needle on cancer risk?

Here’s an overview of the state of the evidence.

Exercise and Cancer Types: A Mixed Bag

When it comes to cancer prevention strategies, guidelines uniformly endorse less couch time and more movement. But a deeper look at the science reveals a complex and often poorly understood connection between exercise and cancer risk.

For certain cancer types, the benefits of exercise on cancer risk seem fairly well established.

The latest edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, published in 2018, cites “strong evidence” that regular exercise might curb the risks for breast and colon cancers as well as bladder, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, and gastric cancers. These guidelines also point to “moderate”-strength evidence of a protective association with lung cancer.

The evidence of a protective effect, however, is strongest for breast and colon cancers, said Jennifer Ligibel, MD, senior physician in the Breast Oncology Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, . “But,” she pointed out, “that may be because they’re some of the most common cancers, and it’s been easier to detect an association.”

Guidelines from the American Cancer Society, published in 2020, align with the 2018 recommendations.

“We believe there’s strong evidence to suggest at least eight different types of cancer are associated with physical activity,” said Erika Rees-Punia, PhD, MPH, senior principal scientist, epidemiology and behavioral research at the American Cancer Society.

That view is not universal, however. Current recommendations from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, for example, are more circumspect, citing only three cancers with good evidence of a protective effect from exercise: Breast (postmenopausal), colon, and endometrial.

“We definitely can’t say exercise reduces the risk of all cancers,” said Lee Jones, PhD, head of the Exercise Oncology Program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “The data suggest it’s just not that simple.”

And it’s challenging to put all the evidence together, Dr. Jones added.

The physical activity guidelines are based on published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses of data from observational studies that examined the relationship between physical activity — aerobic exercise, specifically — and cancer incidence. That means the evidence comes with all the limitations observational studies entail, such as how they collect information on participants’ exercise habits — which, Dr. Jones noted, is typically done via “monster questionnaires” that gauge physical activity in broad strokes.

Pooling all those findings into a meta-analysis is tricky, Dr. Jones added, because individual studies vary in important ways — from follow-up periods to how they quantify exercise and track cancer incidence.

In a study published in February in Cancer Cell, Dr. Jones and his colleagues attempted to address some of those issues by leveraging data from the PLCO screening trial.

The PLCO was a prospective study of over 60,000 US adults that compared the effects of annual screening vs usual care on cancer mortality. At enrollment, participants completed questionnaires that included an assessment of “vigorous” exercise. Based on that, Dr. Jones and his colleagues classified 55% as “exercisers” — meaning they reported 2 or more hours of vigorous exercise per week. The remaining 45%, who were in the 0 to 1 hour per week range, were deemed non-exercisers.

Over a median of 18 years, nearly 16,000 first-time invasive cancers were diagnosed, and some interesting differences between exercisers and non-exercisers emerged. The active group had lower risks for three cancers: Head and neck, with a 26% lower risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), lung (a 20% lower risk), and breast (an 11% lower risk).

What was striking, however, was the lack of connection between exercise and many cancers cited in the guidelines, including colon, gastric, bladder, endometrial, and renal cancers.

Perhaps even more surprising — exercisers had higher risks for prostate cancer (12%) and melanoma (20%). This finding, Dr. Jones said, is in line with a previous pooled analysis of data from 12 US and European prospective cohorts. In this study, the most physically active participants (90th percentile) had higher risks for melanoma and prostate cancer, compared with the least active group (10th percentile).

The melanoma findings do make sense, Dr. Jones said, given that highly active people may spend a lot of time in the sun. “My advice,” Dr. Jones said, “is, if you’re exercising outside, wear sunscreen.” The prostate cancer findings, however, are more puzzling and warrant further research, he noted.

But the bottom line is that the relationship between exercise and cancer types is mixed and far from nailed down.

How Big Is the Effect?

Even if exercise reduces the risk for only certain cancers, that’s still important, particularly when those links appear strongest for common cancer types, such as breast and colon.

But how much of a difference can exercise make?

Based on the evidence, it may only be a modest one. A 2019 systematic review by the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee provided a rough estimate: Across hundreds of epidemiological studies, people with the highest physical activity levels had a 10%-20% lower risk for the cancers cited in the 2018 exercise guidelines compared with people who were least active.

These figures, however, are probably an underestimate, said Anne McTiernan, MD, PhD, a member of the advisory committee and professor of epidemiology, at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

“This is what we usually see when a factor is not measured very well,” said Dr. McTiernan, explaining that the individual studies differed in their categories of “highest” and “lowest” physical activity, such that one study’s “highest” could be another’s mid-range.

“In other words, the effects of physical activity are likely larger” than the review found, Dr. McTiernan said.

The next logical question is whether a bigger exercise “dose” — more time or higher intensity — would have a greater impact on cancer risk. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology tried to clarify that by pooling data on over 750,000 participants from nine prospective cohorts.

Overall, people meeting government recommendations for exercise — equivalent to about 2.5-5 hours of weekly moderate activity, such as a brisk walk, or about 1.25-2.5 hours of more vigorous activities, like running — had lower risks for seven of 15 cancer types studied compared with less active people.

For cancers with positive findings, being on the higher end of the recommended 2.5- to 5-hour weekly range was better. Risk reductions for breast cancer, for instance, were 6% at 2.5 hours of physical activity per week and 10% at 5 hours per week. Similar trends emerged for other cancer types, including colon (8%-14%), endometrial (10%-18%), liver cancer (18%-27%), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in women (11%-18%).

But there may be an exercise sweet spot that maximizes the cancer risk benefit.

Among people who surpassed the recommendations — exercising for more time or more intensely — the risk reduction benefit did not necessarily improve in a linear fashion. For certain cancer types, such as colon and endometrial, the benefits of more vigorous exercise “eroded at higher levels of activity,” the authors said.

The issue here is that most studies have not dug deeply into aerobic exercise habits. Often, studies present participants with a list of activities — walking, biking, and running — and ask them to estimate how often and for what duration they do each.

Plus, “we’ve usually lumped moderate and vigorous activities together,” Dr. Rees-Punia said, which means there’s a lack of “granular data” to say whether certain intensities or frequencies of exercise are optimal and for whom.

Why Exercise May Lower Cancer Risk

Exercise habits do not, of course, exist in a vacuum. Highly active people, Dr. Ligibel said, tend to be of higher socioeconomic status, leaner, and have generally healthier lifestyles than sedentary people.

Body weight is a big confounder as well. However, Dr. Rees-Punia noted, it’s also probably a reason that exercise is linked to lower cancer risks, particularly by preventing weight gain. Still, studies have found that the association between exercise and many cancers remains significant after adjusting for body mass index.

The why remains unclear, though some studies offer clues.

“There’s been some really interesting mechanistic research, suggesting that exercise may help inhibit tumor growth or upregulate the immune system,” Dr. Ligibel said.

That includes not only lab research but small intervention studies. While these studies have largely involved people who already have cancer, some have also focused on healthy individuals.

A 2019 study from Dr. Ligibel and her colleagues, which randomly assigned 49 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer to start either an exercise program or mind-body practices ahead of surgery, found exercisers, who had been active for about a month at the time of surgery, showed signs of immune system upregulation in their tumors, while the control group did not.

Among healthy postmenopausal women, a meta-analysis of six clinical trials from Dr. McTiernan and her colleagues found that exercise plus calorie reduction can reduce levels of breast cancer-related endogenous hormones, more so than calorie-cutting alone. And a 2023 study found that high-intensity exercise boosted the ranks of certain immune cells and reduced inflammation in the colon among people at high risk for colon and endometrial cancers due to Lynch syndrome.

Defining an Exercise ‘Prescription’

Despite the gaps and uncertainties in the research, government guidelines as well as those from the American Cancer Society and other medical groups are in lockstep in their exercise recommendations: Adults should strive for 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (like brisk walking), 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity (like running), or some combination each week.

The guidelines also encourage strength training twice a week — advice that’s based on research tying those activity levels to lower risks for heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

But there’s no “best” exercise prescription for lowering cancer risk specifically. Most epidemiological studies have examined only aerobic activity, Dr. Rees-Punia said, and there’s very little known about whether strength conditioning or other moderate heart rate-elevating activities, such as daily household chores, may reduce the risk for cancer.

Given the lack of nuance in the literature, it’s hard to say what intensities, types, or amounts of exercise are best for each individual.

Going forward, device-based measurements of physical activity could “help us sort out the effects of different intensities of exercise and possibly types,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

But overall, Dr. McTiernan said, the data do show that the risks for several cancers are lower at the widely recommended activity levels.

“The bottom-line advice is still to exercise at least 150 minutes per week at a moderate-intensity level or greater,” Dr. McTiernan said.

Or put another way, moving beats being sedentary. It’s probably wise for everyone to sit less, noted Dr. Rees-Punia, for overall health and based on evidence tying sedentary time to the risks for certain cancers, including colon, endometrial, and lung.

There’s a practical element to consider in all of this: What physical activities will people actually do on the regular? In the big epidemiological studies, Dr. McTiernan noted, middle-aged and older adults most often report walking, suggesting that’s the preferred, or most accessible activity, for many.

“You can only benefit from the physical activity you’ll actually do,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

Dr. Ligibel echoed that sentiment, saying she encourages patients to think about physical activity as a process: “You need to find things you like to do and work them into your daily life, in a sustainable way.

“People often talk about exercise being medicine,” Dr. Ligibel said. “But I think you could take that too far. If we get too prescriptive about it, that could take the joy away.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Exercise is medicine” has become something of a mantra, with good reason. There’s no doubt that regular physical activity has a broad range of health benefits. Exercise can improve circulation, help control weight, reduce stress, and boost mood — take your pick.

Lower cancer risk is also on the list — with exercise promoted as a risk-cutting strategy in government guidelines and in recommendations from professional groups such as the American Cancer Society.

The bulk of the data hangs on less rigorous, observational studies that have linked physical activity to lower risks for certain cancers, but plenty of questions remain.

What are the cancer types where exercise makes a difference? How significant is that impact? And what, exactly, defines a physical activity pattern powerful enough to move the needle on cancer risk?

Here’s an overview of the state of the evidence.

Exercise and Cancer Types: A Mixed Bag

When it comes to cancer prevention strategies, guidelines uniformly endorse less couch time and more movement. But a deeper look at the science reveals a complex and often poorly understood connection between exercise and cancer risk.

For certain cancer types, the benefits of exercise on cancer risk seem fairly well established.

The latest edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, published in 2018, cites “strong evidence” that regular exercise might curb the risks for breast and colon cancers as well as bladder, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, and gastric cancers. These guidelines also point to “moderate”-strength evidence of a protective association with lung cancer.

The evidence of a protective effect, however, is strongest for breast and colon cancers, said Jennifer Ligibel, MD, senior physician in the Breast Oncology Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, . “But,” she pointed out, “that may be because they’re some of the most common cancers, and it’s been easier to detect an association.”

Guidelines from the American Cancer Society, published in 2020, align with the 2018 recommendations.

“We believe there’s strong evidence to suggest at least eight different types of cancer are associated with physical activity,” said Erika Rees-Punia, PhD, MPH, senior principal scientist, epidemiology and behavioral research at the American Cancer Society.

That view is not universal, however. Current recommendations from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, for example, are more circumspect, citing only three cancers with good evidence of a protective effect from exercise: Breast (postmenopausal), colon, and endometrial.

“We definitely can’t say exercise reduces the risk of all cancers,” said Lee Jones, PhD, head of the Exercise Oncology Program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “The data suggest it’s just not that simple.”

And it’s challenging to put all the evidence together, Dr. Jones added.

The physical activity guidelines are based on published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and pooled analyses of data from observational studies that examined the relationship between physical activity — aerobic exercise, specifically — and cancer incidence. That means the evidence comes with all the limitations observational studies entail, such as how they collect information on participants’ exercise habits — which, Dr. Jones noted, is typically done via “monster questionnaires” that gauge physical activity in broad strokes.

Pooling all those findings into a meta-analysis is tricky, Dr. Jones added, because individual studies vary in important ways — from follow-up periods to how they quantify exercise and track cancer incidence.

In a study published in February in Cancer Cell, Dr. Jones and his colleagues attempted to address some of those issues by leveraging data from the PLCO screening trial.

The PLCO was a prospective study of over 60,000 US adults that compared the effects of annual screening vs usual care on cancer mortality. At enrollment, participants completed questionnaires that included an assessment of “vigorous” exercise. Based on that, Dr. Jones and his colleagues classified 55% as “exercisers” — meaning they reported 2 or more hours of vigorous exercise per week. The remaining 45%, who were in the 0 to 1 hour per week range, were deemed non-exercisers.

Over a median of 18 years, nearly 16,000 first-time invasive cancers were diagnosed, and some interesting differences between exercisers and non-exercisers emerged. The active group had lower risks for three cancers: Head and neck, with a 26% lower risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), lung (a 20% lower risk), and breast (an 11% lower risk).

What was striking, however, was the lack of connection between exercise and many cancers cited in the guidelines, including colon, gastric, bladder, endometrial, and renal cancers.

Perhaps even more surprising — exercisers had higher risks for prostate cancer (12%) and melanoma (20%). This finding, Dr. Jones said, is in line with a previous pooled analysis of data from 12 US and European prospective cohorts. In this study, the most physically active participants (90th percentile) had higher risks for melanoma and prostate cancer, compared with the least active group (10th percentile).

The melanoma findings do make sense, Dr. Jones said, given that highly active people may spend a lot of time in the sun. “My advice,” Dr. Jones said, “is, if you’re exercising outside, wear sunscreen.” The prostate cancer findings, however, are more puzzling and warrant further research, he noted.

But the bottom line is that the relationship between exercise and cancer types is mixed and far from nailed down.

How Big Is the Effect?

Even if exercise reduces the risk for only certain cancers, that’s still important, particularly when those links appear strongest for common cancer types, such as breast and colon.

But how much of a difference can exercise make?

Based on the evidence, it may only be a modest one. A 2019 systematic review by the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee provided a rough estimate: Across hundreds of epidemiological studies, people with the highest physical activity levels had a 10%-20% lower risk for the cancers cited in the 2018 exercise guidelines compared with people who were least active.

These figures, however, are probably an underestimate, said Anne McTiernan, MD, PhD, a member of the advisory committee and professor of epidemiology, at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

“This is what we usually see when a factor is not measured very well,” said Dr. McTiernan, explaining that the individual studies differed in their categories of “highest” and “lowest” physical activity, such that one study’s “highest” could be another’s mid-range.

“In other words, the effects of physical activity are likely larger” than the review found, Dr. McTiernan said.

The next logical question is whether a bigger exercise “dose” — more time or higher intensity — would have a greater impact on cancer risk. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology tried to clarify that by pooling data on over 750,000 participants from nine prospective cohorts.

Overall, people meeting government recommendations for exercise — equivalent to about 2.5-5 hours of weekly moderate activity, such as a brisk walk, or about 1.25-2.5 hours of more vigorous activities, like running — had lower risks for seven of 15 cancer types studied compared with less active people.

For cancers with positive findings, being on the higher end of the recommended 2.5- to 5-hour weekly range was better. Risk reductions for breast cancer, for instance, were 6% at 2.5 hours of physical activity per week and 10% at 5 hours per week. Similar trends emerged for other cancer types, including colon (8%-14%), endometrial (10%-18%), liver cancer (18%-27%), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in women (11%-18%).

But there may be an exercise sweet spot that maximizes the cancer risk benefit.

Among people who surpassed the recommendations — exercising for more time or more intensely — the risk reduction benefit did not necessarily improve in a linear fashion. For certain cancer types, such as colon and endometrial, the benefits of more vigorous exercise “eroded at higher levels of activity,” the authors said.

The issue here is that most studies have not dug deeply into aerobic exercise habits. Often, studies present participants with a list of activities — walking, biking, and running — and ask them to estimate how often and for what duration they do each.

Plus, “we’ve usually lumped moderate and vigorous activities together,” Dr. Rees-Punia said, which means there’s a lack of “granular data” to say whether certain intensities or frequencies of exercise are optimal and for whom.

Why Exercise May Lower Cancer Risk

Exercise habits do not, of course, exist in a vacuum. Highly active people, Dr. Ligibel said, tend to be of higher socioeconomic status, leaner, and have generally healthier lifestyles than sedentary people.

Body weight is a big confounder as well. However, Dr. Rees-Punia noted, it’s also probably a reason that exercise is linked to lower cancer risks, particularly by preventing weight gain. Still, studies have found that the association between exercise and many cancers remains significant after adjusting for body mass index.

The why remains unclear, though some studies offer clues.

“There’s been some really interesting mechanistic research, suggesting that exercise may help inhibit tumor growth or upregulate the immune system,” Dr. Ligibel said.

That includes not only lab research but small intervention studies. While these studies have largely involved people who already have cancer, some have also focused on healthy individuals.

A 2019 study from Dr. Ligibel and her colleagues, which randomly assigned 49 women newly diagnosed with breast cancer to start either an exercise program or mind-body practices ahead of surgery, found exercisers, who had been active for about a month at the time of surgery, showed signs of immune system upregulation in their tumors, while the control group did not.

Among healthy postmenopausal women, a meta-analysis of six clinical trials from Dr. McTiernan and her colleagues found that exercise plus calorie reduction can reduce levels of breast cancer-related endogenous hormones, more so than calorie-cutting alone. And a 2023 study found that high-intensity exercise boosted the ranks of certain immune cells and reduced inflammation in the colon among people at high risk for colon and endometrial cancers due to Lynch syndrome.

Defining an Exercise ‘Prescription’

Despite the gaps and uncertainties in the research, government guidelines as well as those from the American Cancer Society and other medical groups are in lockstep in their exercise recommendations: Adults should strive for 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (like brisk walking), 75-150 minutes of vigorous activity (like running), or some combination each week.

The guidelines also encourage strength training twice a week — advice that’s based on research tying those activity levels to lower risks for heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

But there’s no “best” exercise prescription for lowering cancer risk specifically. Most epidemiological studies have examined only aerobic activity, Dr. Rees-Punia said, and there’s very little known about whether strength conditioning or other moderate heart rate-elevating activities, such as daily household chores, may reduce the risk for cancer.

Given the lack of nuance in the literature, it’s hard to say what intensities, types, or amounts of exercise are best for each individual.

Going forward, device-based measurements of physical activity could “help us sort out the effects of different intensities of exercise and possibly types,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

But overall, Dr. McTiernan said, the data do show that the risks for several cancers are lower at the widely recommended activity levels.

“The bottom-line advice is still to exercise at least 150 minutes per week at a moderate-intensity level or greater,” Dr. McTiernan said.

Or put another way, moving beats being sedentary. It’s probably wise for everyone to sit less, noted Dr. Rees-Punia, for overall health and based on evidence tying sedentary time to the risks for certain cancers, including colon, endometrial, and lung.

There’s a practical element to consider in all of this: What physical activities will people actually do on the regular? In the big epidemiological studies, Dr. McTiernan noted, middle-aged and older adults most often report walking, suggesting that’s the preferred, or most accessible activity, for many.

“You can only benefit from the physical activity you’ll actually do,” Dr. Rees-Punia said.

Dr. Ligibel echoed that sentiment, saying she encourages patients to think about physical activity as a process: “You need to find things you like to do and work them into your daily life, in a sustainable way.

“People often talk about exercise being medicine,” Dr. Ligibel said. “But I think you could take that too far. If we get too prescriptive about it, that could take the joy away.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How to Optimize Epidermal Approximation During Wound Suturing Using a Smartphone Camera

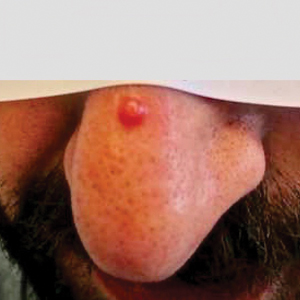

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

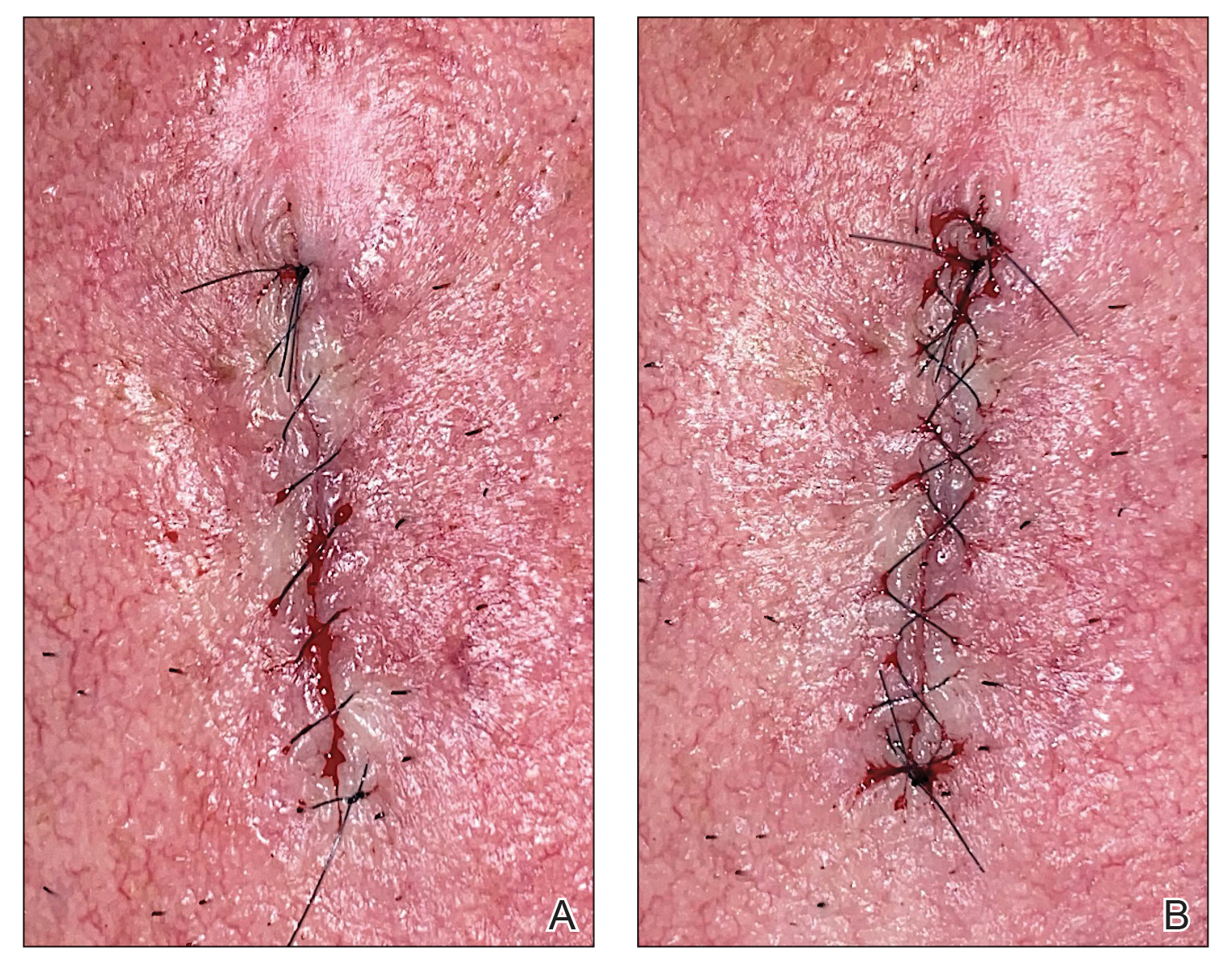

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

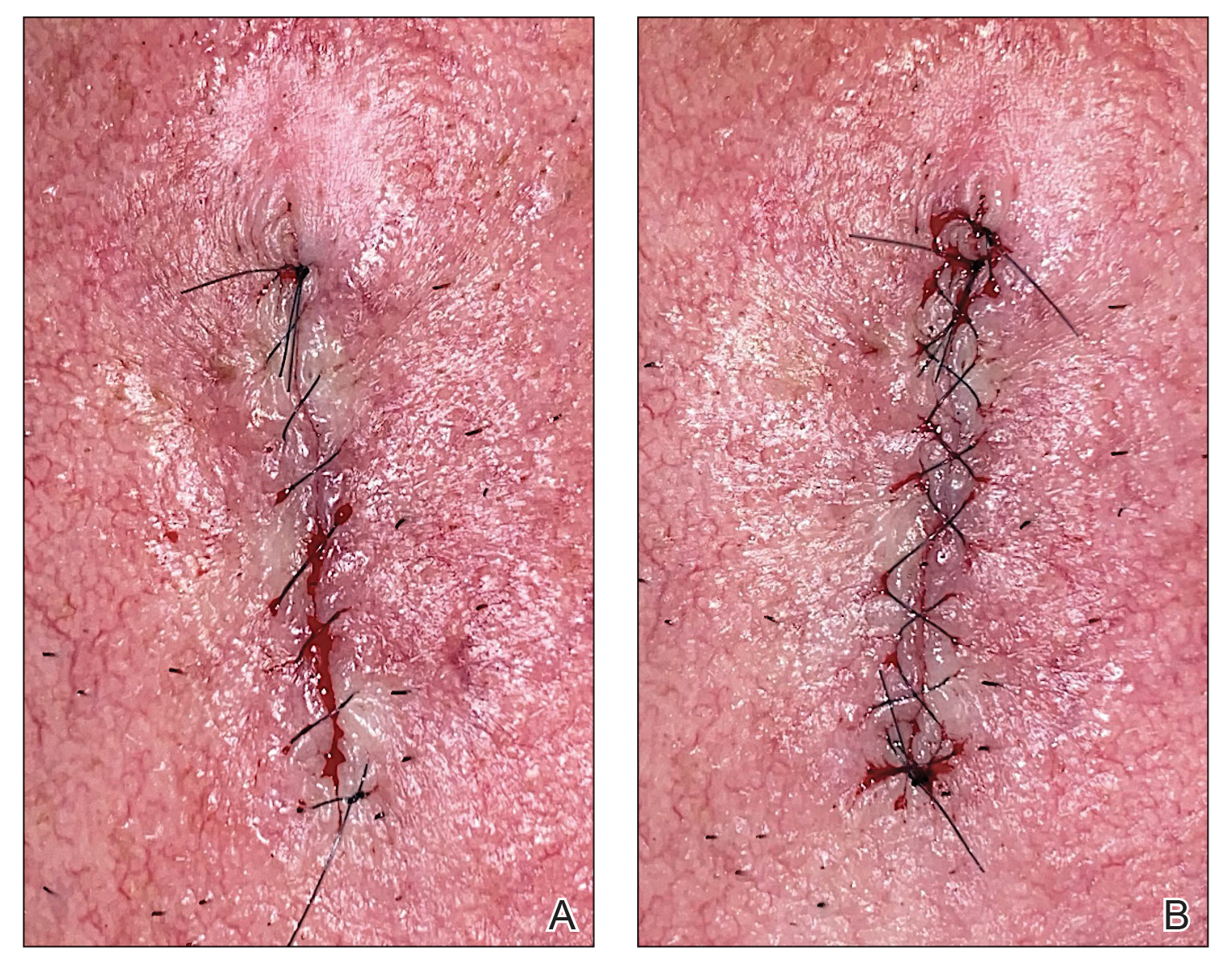

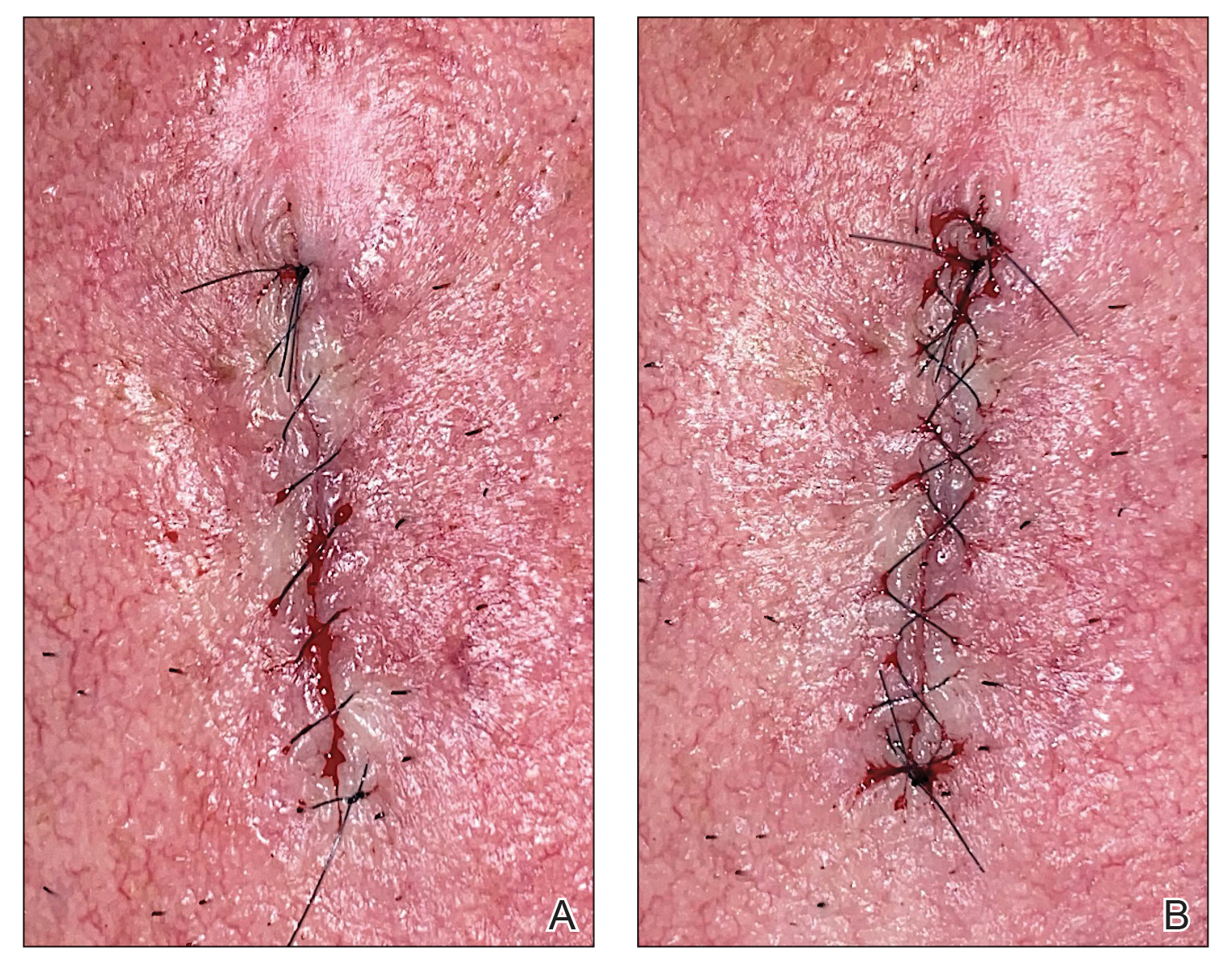

The Technique

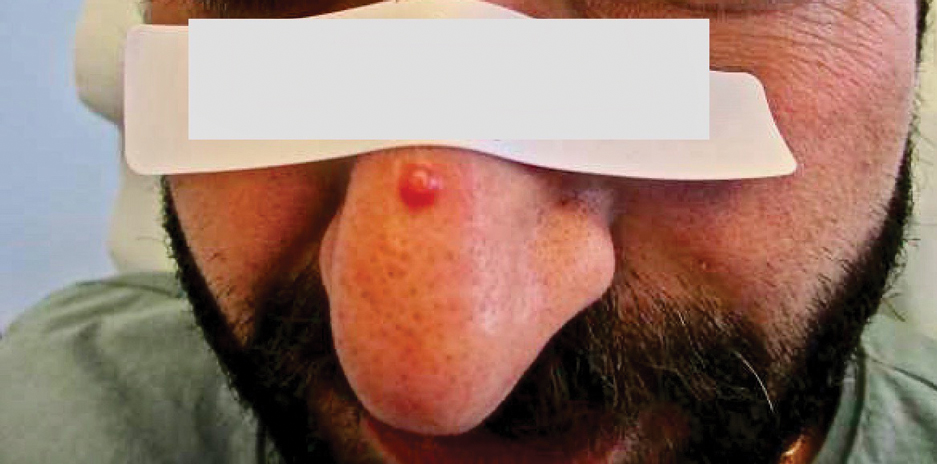

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

The Technique

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

The Technique

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

FDA Removes Harmful Chemicals From Food Packaging

Issued on February 28, 2024, “this means the major source of dietary exposure to PFAS from food packaging like fast-food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, take-out paperboard containers, and pet food bags is being eliminated,” the FDA said in a statement.

In 2020, the FDA had secured commitments from manufacturers to stop selling products containing PFAS used in the food packaging for grease-proofing. “Today’s announcement marks the fulfillment of these voluntary commitments,” according to the agency.

PFAS, a class of thousands of chemicals also called “forever chemicals” are widely used in consumer and industrial products. People may be exposed via contaminated food packaging (although perhaps no longer in the United States) or occupationally. Studies have found that some PFAS disrupt hormones including estrogen and testosterone, whereas others may impair thyroid function.

Endocrine Society Report Sounds the Alarm About PFAS and Others

The FDA’s announcement came just 2 days after the Endocrine Society issued a new alarm about the human health dangers from environmental EDCs including PFAS in a report covering the latest science.

“Endocrine disrupting chemicals” are individual substances or mixtures that can interfere with natural hormonal function, leading to disease or even death. Many are ubiquitous in the modern environment and contribute to a wide range of human diseases.

The new report Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health was issued jointly with the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), a global advocacy organization. It’s an update to the Endocrine Society’s 2015 report, providing new data on the endocrine-disrupting substances previously covered and adding four EDCs not discussed in that document: Pesticides, plastics, PFAS, and children’s products containing arsenic.

At a briefing held during the United Nations Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, last week, the new report’s lead author Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin, noted, “A well-established body of scientific research indicates that endocrine-disrupting chemicals that are part of our daily lives are making us more susceptible to reproductive disorders, cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and other serious health conditions.”

Added Dr. Gore, who is also a member of the Endocrine Society’s Board of Directors, “These chemicals pose particularly serious risks to pregnant women and children. Now is the time for the UN Environment Assembly and other global policymakers to take action to address this threat to public health.”

While the science has been emerging rapidly, global and national chemical control policies haven’t kept up, the authors said. Of particular concern is that EDCs behave differently from other chemicals in many ways, including that even very low-dose exposures can pose health threats, but policies thus far haven’t dealt with that aspect.

Moreover, “the effects of low doses cannot be predicted by the effects observed at high doses. This means there may be no safe dose for exposure to EDCs,” according to the report.

Exposures can come from household products, including furniture, toys, and food packages, as well as electronics building materials and cosmetics. These chemicals are also in the outdoor environment, via pesticides, air pollution, and industrial waste.

“IPEN and the Endocrine Society call for chemical regulations based on the most modern scientific understanding of how hormones act and how EDCs can perturb these actions. We work to educate policy makers in global, regional, and national government assemblies and help ensure that regulations correlate with current scientific understanding,” they said in the report.

New Data on Four Classes of EDCs

Chapters of the report summarized the latest information about the science of EDCs and their links to endocrine disease and real-world exposure. It included a special section about “EDCs throughout the plastics life cycle” and a summary of the links between EDCs and climate change.

The report reviewed three pesticides, including the world’s most heavily applied herbicide, glycophosphate. Exposures can occur directly from the air, water, dust, and food residues. Recent data linked glycophosphate to adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Two toxic plastic chemicals, phthalates and bisphenols, are present in personal care products, among others. Emerging evidence links them with impaired neurodevelopment, leading to impaired cognitive function, learning, attention, and impulsivity.

Arsenic has long been linked to human health conditions including cancer, but more recent evidence finds it can disrupt multiple endocrine systems and lead to metabolic conditions including diabetes, reproductive dysfunction, and cardiovascular and neurocognitive conditions.

The special section about plastics noted that they are made from fossil fuels and chemicals, including many toxic substances that are known or suspected EDCs. People who live near plastic production facilities or waste dumps may be at greatest risk, but anyone can be exposed using any plastic product. Plastic waste disposal is increasingly problematic and often foisted on lower- and middle-income countries.

‘Additional Education and Awareness-Raising Among Stakeholders Remain Necessary’

Policies aimed at reducing human health risks from EDCs have included the 2022 Plastics Treaty, a resolution adopted by 175 countries at the United Nations Environmental Assembly that “may be a significant step toward global control of plastics and elimination of threats from exposures to EDCs in plastics,” the report said.

The authors added, “While significant progress has been made in recent years connecting scientific advances on EDCs with health-protective policies, additional education and awareness-raising among stakeholders remain necessary to achieve a safer and more sustainable environment that minimizes exposure to these harmful chemicals.”

The document was produced with financial contributions from the Government of Sweden, the Tides Foundation, Passport Foundation, and other donors.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Issued on February 28, 2024, “this means the major source of dietary exposure to PFAS from food packaging like fast-food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, take-out paperboard containers, and pet food bags is being eliminated,” the FDA said in a statement.

In 2020, the FDA had secured commitments from manufacturers to stop selling products containing PFAS used in the food packaging for grease-proofing. “Today’s announcement marks the fulfillment of these voluntary commitments,” according to the agency.

PFAS, a class of thousands of chemicals also called “forever chemicals” are widely used in consumer and industrial products. People may be exposed via contaminated food packaging (although perhaps no longer in the United States) or occupationally. Studies have found that some PFAS disrupt hormones including estrogen and testosterone, whereas others may impair thyroid function.

Endocrine Society Report Sounds the Alarm About PFAS and Others

The FDA’s announcement came just 2 days after the Endocrine Society issued a new alarm about the human health dangers from environmental EDCs including PFAS in a report covering the latest science.

“Endocrine disrupting chemicals” are individual substances or mixtures that can interfere with natural hormonal function, leading to disease or even death. Many are ubiquitous in the modern environment and contribute to a wide range of human diseases.

The new report Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health was issued jointly with the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), a global advocacy organization. It’s an update to the Endocrine Society’s 2015 report, providing new data on the endocrine-disrupting substances previously covered and adding four EDCs not discussed in that document: Pesticides, plastics, PFAS, and children’s products containing arsenic.

At a briefing held during the United Nations Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, last week, the new report’s lead author Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin, noted, “A well-established body of scientific research indicates that endocrine-disrupting chemicals that are part of our daily lives are making us more susceptible to reproductive disorders, cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and other serious health conditions.”

Added Dr. Gore, who is also a member of the Endocrine Society’s Board of Directors, “These chemicals pose particularly serious risks to pregnant women and children. Now is the time for the UN Environment Assembly and other global policymakers to take action to address this threat to public health.”

While the science has been emerging rapidly, global and national chemical control policies haven’t kept up, the authors said. Of particular concern is that EDCs behave differently from other chemicals in many ways, including that even very low-dose exposures can pose health threats, but policies thus far haven’t dealt with that aspect.

Moreover, “the effects of low doses cannot be predicted by the effects observed at high doses. This means there may be no safe dose for exposure to EDCs,” according to the report.

Exposures can come from household products, including furniture, toys, and food packages, as well as electronics building materials and cosmetics. These chemicals are also in the outdoor environment, via pesticides, air pollution, and industrial waste.

“IPEN and the Endocrine Society call for chemical regulations based on the most modern scientific understanding of how hormones act and how EDCs can perturb these actions. We work to educate policy makers in global, regional, and national government assemblies and help ensure that regulations correlate with current scientific understanding,” they said in the report.

New Data on Four Classes of EDCs

Chapters of the report summarized the latest information about the science of EDCs and their links to endocrine disease and real-world exposure. It included a special section about “EDCs throughout the plastics life cycle” and a summary of the links between EDCs and climate change.

The report reviewed three pesticides, including the world’s most heavily applied herbicide, glycophosphate. Exposures can occur directly from the air, water, dust, and food residues. Recent data linked glycophosphate to adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Two toxic plastic chemicals, phthalates and bisphenols, are present in personal care products, among others. Emerging evidence links them with impaired neurodevelopment, leading to impaired cognitive function, learning, attention, and impulsivity.

Arsenic has long been linked to human health conditions including cancer, but more recent evidence finds it can disrupt multiple endocrine systems and lead to metabolic conditions including diabetes, reproductive dysfunction, and cardiovascular and neurocognitive conditions.

The special section about plastics noted that they are made from fossil fuels and chemicals, including many toxic substances that are known or suspected EDCs. People who live near plastic production facilities or waste dumps may be at greatest risk, but anyone can be exposed using any plastic product. Plastic waste disposal is increasingly problematic and often foisted on lower- and middle-income countries.

‘Additional Education and Awareness-Raising Among Stakeholders Remain Necessary’

Policies aimed at reducing human health risks from EDCs have included the 2022 Plastics Treaty, a resolution adopted by 175 countries at the United Nations Environmental Assembly that “may be a significant step toward global control of plastics and elimination of threats from exposures to EDCs in plastics,” the report said.

The authors added, “While significant progress has been made in recent years connecting scientific advances on EDCs with health-protective policies, additional education and awareness-raising among stakeholders remain necessary to achieve a safer and more sustainable environment that minimizes exposure to these harmful chemicals.”

The document was produced with financial contributions from the Government of Sweden, the Tides Foundation, Passport Foundation, and other donors.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Issued on February 28, 2024, “this means the major source of dietary exposure to PFAS from food packaging like fast-food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, take-out paperboard containers, and pet food bags is being eliminated,” the FDA said in a statement.

In 2020, the FDA had secured commitments from manufacturers to stop selling products containing PFAS used in the food packaging for grease-proofing. “Today’s announcement marks the fulfillment of these voluntary commitments,” according to the agency.

PFAS, a class of thousands of chemicals also called “forever chemicals” are widely used in consumer and industrial products. People may be exposed via contaminated food packaging (although perhaps no longer in the United States) or occupationally. Studies have found that some PFAS disrupt hormones including estrogen and testosterone, whereas others may impair thyroid function.

Endocrine Society Report Sounds the Alarm About PFAS and Others

The FDA’s announcement came just 2 days after the Endocrine Society issued a new alarm about the human health dangers from environmental EDCs including PFAS in a report covering the latest science.

“Endocrine disrupting chemicals” are individual substances or mixtures that can interfere with natural hormonal function, leading to disease or even death. Many are ubiquitous in the modern environment and contribute to a wide range of human diseases.

The new report Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health was issued jointly with the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), a global advocacy organization. It’s an update to the Endocrine Society’s 2015 report, providing new data on the endocrine-disrupting substances previously covered and adding four EDCs not discussed in that document: Pesticides, plastics, PFAS, and children’s products containing arsenic.

At a briefing held during the United Nations Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, last week, the new report’s lead author Andrea C. Gore, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin, noted, “A well-established body of scientific research indicates that endocrine-disrupting chemicals that are part of our daily lives are making us more susceptible to reproductive disorders, cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and other serious health conditions.”

Added Dr. Gore, who is also a member of the Endocrine Society’s Board of Directors, “These chemicals pose particularly serious risks to pregnant women and children. Now is the time for the UN Environment Assembly and other global policymakers to take action to address this threat to public health.”

While the science has been emerging rapidly, global and national chemical control policies haven’t kept up, the authors said. Of particular concern is that EDCs behave differently from other chemicals in many ways, including that even very low-dose exposures can pose health threats, but policies thus far haven’t dealt with that aspect.

Moreover, “the effects of low doses cannot be predicted by the effects observed at high doses. This means there may be no safe dose for exposure to EDCs,” according to the report.

Exposures can come from household products, including furniture, toys, and food packages, as well as electronics building materials and cosmetics. These chemicals are also in the outdoor environment, via pesticides, air pollution, and industrial waste.

“IPEN and the Endocrine Society call for chemical regulations based on the most modern scientific understanding of how hormones act and how EDCs can perturb these actions. We work to educate policy makers in global, regional, and national government assemblies and help ensure that regulations correlate with current scientific understanding,” they said in the report.

New Data on Four Classes of EDCs

Chapters of the report summarized the latest information about the science of EDCs and their links to endocrine disease and real-world exposure. It included a special section about “EDCs throughout the plastics life cycle” and a summary of the links between EDCs and climate change.

The report reviewed three pesticides, including the world’s most heavily applied herbicide, glycophosphate. Exposures can occur directly from the air, water, dust, and food residues. Recent data linked glycophosphate to adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Two toxic plastic chemicals, phthalates and bisphenols, are present in personal care products, among others. Emerging evidence links them with impaired neurodevelopment, leading to impaired cognitive function, learning, attention, and impulsivity.

Arsenic has long been linked to human health conditions including cancer, but more recent evidence finds it can disrupt multiple endocrine systems and lead to metabolic conditions including diabetes, reproductive dysfunction, and cardiovascular and neurocognitive conditions.

The special section about plastics noted that they are made from fossil fuels and chemicals, including many toxic substances that are known or suspected EDCs. People who live near plastic production facilities or waste dumps may be at greatest risk, but anyone can be exposed using any plastic product. Plastic waste disposal is increasingly problematic and often foisted on lower- and middle-income countries.

‘Additional Education and Awareness-Raising Among Stakeholders Remain Necessary’

Policies aimed at reducing human health risks from EDCs have included the 2022 Plastics Treaty, a resolution adopted by 175 countries at the United Nations Environmental Assembly that “may be a significant step toward global control of plastics and elimination of threats from exposures to EDCs in plastics,” the report said.

The authors added, “While significant progress has been made in recent years connecting scientific advances on EDCs with health-protective policies, additional education and awareness-raising among stakeholders remain necessary to achieve a safer and more sustainable environment that minimizes exposure to these harmful chemicals.”

The document was produced with financial contributions from the Government of Sweden, the Tides Foundation, Passport Foundation, and other donors.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

What Happens to Surgery Candidates with BHDs and Cancer?

based on data from a new study of nearly 700,000 individuals.

The reason for this association remains unclear, and highlights the need to address existing behavioral health disorders (BHDs), which can be exacerbated after a patient is diagnosed with cancer, wrote Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, of The Ohio State University, Columbus, and colleagues. A cancer diagnosis can cause not only physical stress, but mental, emotional, social, and economic stress that can prompt a new BHD, cause relapse of a previous BHD, or exacerbate a current BHD, the researchers noted.

What is Known About BHDs and Cancer?

Although previous studies have shown a possible association between BHDs and increased cancer risk, as well as reduced compliance with care, the effect of BHDs on outcomes in cancer patients undergoing surgical resection has not been examined, wrote Dr. Pawlik and colleagues.

Previous research has focused on the impact of having a preexisting serious mental illness (SMI) such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder on cancer care.

A 2023 literature review of 27 studies published in the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences showed that patients with preexisting severe mental illness (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) had greater cancer-related mortality. In that study, the researchers also found that patients with severe mental illness were more likely to have metastatic disease at diagnosis, but less likely to receive optimal treatments, than individuals without SMIs.

Many studies also have focused on patients developing mental health problems (including BHDs) after a cancer diagnosis, but the current study is the first known to examine outcomes in those with BHDs before cancer.

Why Was It Important to Conduct This Study?

“BHDs are a diverse set of mental illnesses that affect an individual’s psychosocial wellbeing, potentially resulting in maladaptive behaviors,” Dr. Pawlik said in an interview. BHDs, which include substance abuse, eating disorders, and sleep disorders, are less common than anxiety/depression, but have an estimated prevalence of 1.3%-3.1% among adults in the United States, he said.

What Does the New Study Add?

In the new review by Dr. Pawlik and colleagues, published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (Katayama ES. J Am Coll Surg. 2024 Feb 29. doi: 2024. 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000954), BHDs were defined as substance abuse, eating disorders, or sleep disorders, which had not been the focus of previous studies. The researchers reviewed data from 694,836 adult patients with lung, esophageal, gastric, liver, pancreatic, or colorectal cancer between 2018-2021 using the Medicare Standard Analytic files. A total of 46,719 patients (6.7%) had at least one BHD.

Overall, patients with a BHD were significantly less likely than those without a BHD to undergo surgical resection (20.3% vs. 23.4%). Patients with a BHD also had significantly worse long-term postoperative survival than those without BHDs (median 37.1 months vs. 46.6 months) and significantly higher in-hospital costs ($17,432 vs. 16,159, P less than .001 for all).

Among patients who underwent cancer surgery, the odds of any complication were significantly higher for those with a BHD compared to those with no BHD (odds ratio 1.32), as were the odds of a prolonged length of stay (OR 1.67) and 90-day readmission (OR 1.57).

Dr. Pawlik said he was surprised by several of the findings, including that 1 in 15 Medicare beneficiaries had a BHD diagnosis, “with male sex and minority racial status, as well as higher social vulnerability, being associated with a higher prevalence of BHD.”

Also, the independent association of having a BHD with 30%-50% higher odds of a complication, prolonged length of stay, and 90-day readmission was higher than Dr. Pawlik had anticipated.

Why Do Patients With BHDs Have Fewer Surgeries and Worse Outcomes?

The reasons for this association were likely multifactorial and may reflect the greater burden of medical comorbidity and chronic illness in many patients with BHDs because of maladaptive lifestyles or poor nutrition status, Dr. Pawlik said.

“Patients with BHDs also likely face barriers to accessing care, which was noted particularly among patients with BHDs who lived in socially vulnerable areas,” he said. BHD patients also were more likely to be treated at low-volume rather than high-volume hospitals, “which undoubtedly contributed in part to worse outcomes in this cohort of patients,” he added.

What Can Oncologists Do to Help?

The take-home message for clinicians is that BHDs are linked to worse surgical outcomes and higher health care costs in cancer patients, Dr. Pawlik said in an interview.

“Enhanced accessibility to behavioral healthcare, as well as comprehensive policy reform related to mental health services are needed to improve care of patients with BHDs,” he said. “For example, implementing psychiatry compensation programs may encourage practice in vulnerable areas,” he said.

Other strategies include a following a collaborative care model involving mental health professionals working in tandem with primary care and mid-level practitioners and increasing use and establishment of telehealth systems to improve patient access to BHD services, he said.

What Are the Limitations?

The study by Dr. Pawlik and colleagues was limited by several factors, including the lack of data on younger patients and the full range of BHDs, as well as underreporting of BHDs and the high copays for mental health care, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that concomitant BHDs are associated with worse cancer outcomes and higher in-hospital costs, and illustrate the need to screen for and target these conditions in cancer patients, the researchers concluded.

What Are the Next Steps for Research?

The current study involved Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older, and more research is needed to investigate the impact of BHDs among younger cancer patients in whom the prevalence may be higher and the impact of BHDs may be different, Dr. Pawlik said in an interview. In addition, the analysis of BHDs as a composite of substance abuse, eating disorders, and sleep disorders (because the numbers were too small to break out data for each disorder, separately) prevented investigation of potential differences and unique challenges faced by distinct subpopulations of BHD patients, he said.

“Future studies should examine the individual impact of substance abuse, eating disorders, and sleep disorders on access to surgery, as well as the potential different impact that each one of these different BHDs may have on postoperative outcomes,” Dr. Pawlik suggested.

The study was supported by The Ohio State University College of Medicine Roessler Summer Research Scholarship. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

based on data from a new study of nearly 700,000 individuals.

The reason for this association remains unclear, and highlights the need to address existing behavioral health disorders (BHDs), which can be exacerbated after a patient is diagnosed with cancer, wrote Timothy M. Pawlik, MD, of The Ohio State University, Columbus, and colleagues. A cancer diagnosis can cause not only physical stress, but mental, emotional, social, and economic stress that can prompt a new BHD, cause relapse of a previous BHD, or exacerbate a current BHD, the researchers noted.

What is Known About BHDs and Cancer?

Although previous studies have shown a possible association between BHDs and increased cancer risk, as well as reduced compliance with care, the effect of BHDs on outcomes in cancer patients undergoing surgical resection has not been examined, wrote Dr. Pawlik and colleagues.

Previous research has focused on the impact of having a preexisting serious mental illness (SMI) such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder on cancer care.

A 2023 literature review of 27 studies published in the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences showed that patients with preexisting severe mental illness (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) had greater cancer-related mortality. In that study, the researchers also found that patients with severe mental illness were more likely to have metastatic disease at diagnosis, but less likely to receive optimal treatments, than individuals without SMIs.

Many studies also have focused on patients developing mental health problems (including BHDs) after a cancer diagnosis, but the current study is the first known to examine outcomes in those with BHDs before cancer.

Why Was It Important to Conduct This Study?

“BHDs are a diverse set of mental illnesses that affect an individual’s psychosocial wellbeing, potentially resulting in maladaptive behaviors,” Dr. Pawlik said in an interview. BHDs, which include substance abuse, eating disorders, and sleep disorders, are less common than anxiety/depression, but have an estimated prevalence of 1.3%-3.1% among adults in the United States, he said.

What Does the New Study Add?

In the new review by Dr. Pawlik and colleagues, published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (Katayama ES. J Am Coll Surg. 2024 Feb 29. doi: 2024. 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000954), BHDs were defined as substance abuse, eating disorders, or sleep disorders, which had not been the focus of previous studies. The researchers reviewed data from 694,836 adult patients with lung, esophageal, gastric, liver, pancreatic, or colorectal cancer between 2018-2021 using the Medicare Standard Analytic files. A total of 46,719 patients (6.7%) had at least one BHD.

Overall, patients with a BHD were significantly less likely than those without a BHD to undergo surgical resection (20.3% vs. 23.4%). Patients with a BHD also had significantly worse long-term postoperative survival than those without BHDs (median 37.1 months vs. 46.6 months) and significantly higher in-hospital costs ($17,432 vs. 16,159, P less than .001 for all).

Among patients who underwent cancer surgery, the odds of any complication were significantly higher for those with a BHD compared to those with no BHD (odds ratio 1.32), as were the odds of a prolonged length of stay (OR 1.67) and 90-day readmission (OR 1.57).