User login

For MD-IQ use only

3D Printing for the Development of Palatal Defect Prosthetics

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

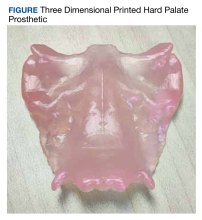

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

Are Direct-to-Consumer Microbiome Tests Clinically Useful?

Companies selling gut microbiome tests directly to consumers offer up a variety of claims to promote their products.

“We analyze the trillions of microbes in your gut microflora and craft a unique formula for your unique gut needs,” one says. “Get actionable dietary, supplement, and lifestyle recommendations from our microbiome experts based on your results, tailored to mom and baby’s biomarkers. ... Any family member like dads or siblings are welcome too,” says another.

The companies assert that they can improve gut health by offering individuals personalized treatments based on their gut microbiome test results. The trouble is, no provider, company, or technology can reliably do that yet.

Clinical Implications, Not Applications

The microbiome is the “constellation of microorganisms that call the human body home,” including many strains of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. That constellation comprises some 39 trillion cells.

Although knowledge is increasing on the oral, cutaneous, and vaginal microbiomes, the gut microbiome is arguably the most studied. However, while research is increasingly demonstrating that the gut microbiome has clinical implications, much work needs to be done before reliable applications based on that research are available.

But , Erik C. von Rosenvinge, MD, AGAF, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the VA Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, said in an interview.

“If you go to their websites, even if it’s not stated overtly, these companies at least give the impression that they’re providing actionable, useful information,” he said. “The sites recommend microbiome testing, and often supplements, probiotics, or other products that they sell. And consumers are told they need to be tested again once they start taking any of these products to see if they’re receiving any benefit.”

Dr. von Rosenvinge and colleagues authored a recent article in Science arguing that DTC microbiome tests “lack analytical and clinical validity” — and yet regulation of the industry has been “generally ignored.” They identified 31 companies globally, 17 of which are based in the United States, claiming to have products and/or services aimed at changing the intestinal microbiome.

Unreliable, Unregulated

The lack of reliability has been shown by experts who have tested the tests.

“People have taken the same stool sample, sent it to multiple companies, and gotten different results back,” Dr. von Rosenvinge said. “People also have taken a stool sample and sent it to the same company under two different names and received two different results. If the test is unreliable at its foundational level, it’s hard to use it in any clinical way.”

Test users’ methods and the companies’ procedures can affect the results, Dina Kao, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, said in an interview.

“So many biases can be introduced at every single step of the way, starting from how the stool sample was collected and how it’s preserved or not being preserved, because that can introduce a lot of noise that would change the analyses. Which primer they’re using to amplify the signals and which bioinformatic pipeline they use are also important,” said Dr. Kao, who presented at the recent Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit, organized by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM).

Different investigators and companies use different technologies, so it’s very difficult to compare them and to create a standard, said Mahmoud Ghannoum, PhD, a professor in the dermatology and pathology departments at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and director of the Center for Medical Mycology at University Hospitals in Cleveland.

The complexity of the gut microbiome makes test standardization more difficult than it is when just one organism is involved, Dr. Ghannoum, who chaired the antifungal subcommittee at the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, said in an interview.

“Even though many researchers are focusing on bacteria, we also have fungi and viruses. We need standardization of methods for testing these organisms if we want to have regulations,” said Dr. Ghannoum, a cofounder of BIOHM, a microbiome company that offers nondiagnostic tests and markets a variety of probiotics, prebiotics, and immunity supplements. BIOHM is one of the 31 companies identified by Dr. von Rosenvinge and colleagues, as noted above.

Dr. Ghannoum believes that taking a systematic approach could facilitate standardization and, ultimately, regulation of the DTC microbiome testing products. He and his colleagues described such an approach by outlining the stages for designing probiotics capable of modulating the microbiome in chronic diseases, using Crohn’s disease as a model. Their strategy involved the following steps:

- Using primary microbiome data to identify, by abundance, the microorganisms underlying dysbiosis.

- Gaining insight into the interactions among the identified pathogens.

- Conducting a correlation analysis to identify potential lead probiotic strains that antagonize these pathogens and discovering metabolites that can interrupt their interactions.

- Creating a prototype formulation for testing.

- Validating the efficacy of the candidate formulation via preclinical in vitro and in vivo testing.

- Conducting clinical testing.

Dr. Ghannoum recommends that companies use a similar process “to provide evidence that what they are doing will be helpful, not only for them but also for the reputation of the whole industry.”

Potential Pitfalls

Whether test results from commercial companies are positioned as wellness aids or diagnostic tools, providing advice based on the results “is where the danger can really come in,” Dr. Kao said. “There is still so much we don’t know about which microbial signatures are associated with each condition.”

“Even when we have a solution, like the Crohn’s exclusion diet, a physician doesn’t know enough of the nuances to give advice to a patient,” she said. “That really should be done under the guidance of an expert dietitian. And if a company is selling probiotics, I personally feel that’s not ethical. I’m pretty sure there’s always going to be some kind of conflict of interest.”

Supplements and probiotics are generally safe, but negative consequences can occur, Dr. von Rosenvinge noted.

“We occasionally see people who end up with liver problems as a result of certain supplements, and rarely, probiotics have been associated with infections from those organisms, usually in those with a compromised immune system,” he said.

Other risks include people taking supplements or probiotics when they actually have a medically treatable condition or delays in diagnosis of a potentially serious underlying condition, such as colon cancer, he said. Some patients may stop taking their traditional medication in favor of taking supplements or may experience a drug-supplement interaction if they take both.

What to Tell Patients

“Doctors should be advising against this testing for their patients,” gastroenterologist Colleen R. Kelly, MD, AGAF, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview. “I explain to patients that these tests are not validated and are clinically meaningless data and not worth the money. There is a reason they are not covered by insurance.

“Recommendations to purchase probiotics or supplements manufactured by the testing company to ‘restore a balanced or healthy microbiome’ clearly seem like a scam,” she added. “I believe some of these companies are capitalizing on patients who are desperate for answers to explain chronic symptoms, such as bloating in irritable bowel syndrome.”

Dr. von Rosenvinge said that the message to patients “is that the science isn’t there yet to support using the results of these tests in a meaningful way. We believe the microbiome is very important in health and disease, but the tests themselves in their current state are not as reliable and reproducible as we would like.”

When patients come in with test results, the first question a clinician should ask is what led them to seek out this type of information in the first place, Dr. von Rosenvinge said.

“Our patient focus groups suggested that many have not gotten clear, satisfactory answers from traditional medicine,” he said. “We don’t have a single test that says, yes, you have irritable bowel syndrome, or no, you don’t. We might suggest things that are helpful for some people and are less helpful for others.”

Dr. Kelly said she worries that “there are snake oil salesmen and cons out there who will gladly take your money. These may be smart people, capable of doing very high-level testing, and even producing very detailed and accurate results, but that doesn’t mean we know what to do with them.”

She hopes to see a microbiome-based diagnostic test in the future, particularly if the ability to therapeutically manipulate the gut microbiome in various diseases becomes a reality.

Educate Clinicians, Companies

More education is needed on the subject, so we can become “microbial clinicians,” Dr. Kao said.

“The microbiome never came up when I was going through my medical education,” she said. But we, and the next generation of physicians, “need to at least be able to understand the basics.

“Hopefully, one day, we will be in a position where we can have meaningful interpretations of the test results and make some kind of meaningful dietary interventions,” Dr. Kao added.

As for clinicians who are currently ordering these tests and products directly from the DTC companies, Dr. Kao said, “I roll my eyes.”

Dr. Ghannoum reiterated that companies offering microbiome tests and products also need to be educated and encouraged to use systematic approaches to product development and interpretation.

“Companies should be open to calls from clinicians and be ready to explain findings on a report, as well as the basis for any recommendations,” he said.

Dr. von Rosenvinge, Dr. Kao, and Dr. Kelly had no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Ghannoum is a cofounder of BIOHM.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Companies selling gut microbiome tests directly to consumers offer up a variety of claims to promote their products.

“We analyze the trillions of microbes in your gut microflora and craft a unique formula for your unique gut needs,” one says. “Get actionable dietary, supplement, and lifestyle recommendations from our microbiome experts based on your results, tailored to mom and baby’s biomarkers. ... Any family member like dads or siblings are welcome too,” says another.

The companies assert that they can improve gut health by offering individuals personalized treatments based on their gut microbiome test results. The trouble is, no provider, company, or technology can reliably do that yet.

Clinical Implications, Not Applications

The microbiome is the “constellation of microorganisms that call the human body home,” including many strains of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. That constellation comprises some 39 trillion cells.

Although knowledge is increasing on the oral, cutaneous, and vaginal microbiomes, the gut microbiome is arguably the most studied. However, while research is increasingly demonstrating that the gut microbiome has clinical implications, much work needs to be done before reliable applications based on that research are available.

But , Erik C. von Rosenvinge, MD, AGAF, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the VA Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, said in an interview.

“If you go to their websites, even if it’s not stated overtly, these companies at least give the impression that they’re providing actionable, useful information,” he said. “The sites recommend microbiome testing, and often supplements, probiotics, or other products that they sell. And consumers are told they need to be tested again once they start taking any of these products to see if they’re receiving any benefit.”

Dr. von Rosenvinge and colleagues authored a recent article in Science arguing that DTC microbiome tests “lack analytical and clinical validity” — and yet regulation of the industry has been “generally ignored.” They identified 31 companies globally, 17 of which are based in the United States, claiming to have products and/or services aimed at changing the intestinal microbiome.

Unreliable, Unregulated

The lack of reliability has been shown by experts who have tested the tests.

“People have taken the same stool sample, sent it to multiple companies, and gotten different results back,” Dr. von Rosenvinge said. “People also have taken a stool sample and sent it to the same company under two different names and received two different results. If the test is unreliable at its foundational level, it’s hard to use it in any clinical way.”

Test users’ methods and the companies’ procedures can affect the results, Dina Kao, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, said in an interview.

“So many biases can be introduced at every single step of the way, starting from how the stool sample was collected and how it’s preserved or not being preserved, because that can introduce a lot of noise that would change the analyses. Which primer they’re using to amplify the signals and which bioinformatic pipeline they use are also important,” said Dr. Kao, who presented at the recent Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit, organized by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM).

Different investigators and companies use different technologies, so it’s very difficult to compare them and to create a standard, said Mahmoud Ghannoum, PhD, a professor in the dermatology and pathology departments at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and director of the Center for Medical Mycology at University Hospitals in Cleveland.

The complexity of the gut microbiome makes test standardization more difficult than it is when just one organism is involved, Dr. Ghannoum, who chaired the antifungal subcommittee at the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, said in an interview.

“Even though many researchers are focusing on bacteria, we also have fungi and viruses. We need standardization of methods for testing these organisms if we want to have regulations,” said Dr. Ghannoum, a cofounder of BIOHM, a microbiome company that offers nondiagnostic tests and markets a variety of probiotics, prebiotics, and immunity supplements. BIOHM is one of the 31 companies identified by Dr. von Rosenvinge and colleagues, as noted above.

Dr. Ghannoum believes that taking a systematic approach could facilitate standardization and, ultimately, regulation of the DTC microbiome testing products. He and his colleagues described such an approach by outlining the stages for designing probiotics capable of modulating the microbiome in chronic diseases, using Crohn’s disease as a model. Their strategy involved the following steps:

- Using primary microbiome data to identify, by abundance, the microorganisms underlying dysbiosis.

- Gaining insight into the interactions among the identified pathogens.

- Conducting a correlation analysis to identify potential lead probiotic strains that antagonize these pathogens and discovering metabolites that can interrupt their interactions.

- Creating a prototype formulation for testing.

- Validating the efficacy of the candidate formulation via preclinical in vitro and in vivo testing.

- Conducting clinical testing.

Dr. Ghannoum recommends that companies use a similar process “to provide evidence that what they are doing will be helpful, not only for them but also for the reputation of the whole industry.”

Potential Pitfalls

Whether test results from commercial companies are positioned as wellness aids or diagnostic tools, providing advice based on the results “is where the danger can really come in,” Dr. Kao said. “There is still so much we don’t know about which microbial signatures are associated with each condition.”

“Even when we have a solution, like the Crohn’s exclusion diet, a physician doesn’t know enough of the nuances to give advice to a patient,” she said. “That really should be done under the guidance of an expert dietitian. And if a company is selling probiotics, I personally feel that’s not ethical. I’m pretty sure there’s always going to be some kind of conflict of interest.”

Supplements and probiotics are generally safe, but negative consequences can occur, Dr. von Rosenvinge noted.

“We occasionally see people who end up with liver problems as a result of certain supplements, and rarely, probiotics have been associated with infections from those organisms, usually in those with a compromised immune system,” he said.

Other risks include people taking supplements or probiotics when they actually have a medically treatable condition or delays in diagnosis of a potentially serious underlying condition, such as colon cancer, he said. Some patients may stop taking their traditional medication in favor of taking supplements or may experience a drug-supplement interaction if they take both.

What to Tell Patients

“Doctors should be advising against this testing for their patients,” gastroenterologist Colleen R. Kelly, MD, AGAF, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview. “I explain to patients that these tests are not validated and are clinically meaningless data and not worth the money. There is a reason they are not covered by insurance.

“Recommendations to purchase probiotics or supplements manufactured by the testing company to ‘restore a balanced or healthy microbiome’ clearly seem like a scam,” she added. “I believe some of these companies are capitalizing on patients who are desperate for answers to explain chronic symptoms, such as bloating in irritable bowel syndrome.”

Dr. von Rosenvinge said that the message to patients “is that the science isn’t there yet to support using the results of these tests in a meaningful way. We believe the microbiome is very important in health and disease, but the tests themselves in their current state are not as reliable and reproducible as we would like.”

When patients come in with test results, the first question a clinician should ask is what led them to seek out this type of information in the first place, Dr. von Rosenvinge said.

“Our patient focus groups suggested that many have not gotten clear, satisfactory answers from traditional medicine,” he said. “We don’t have a single test that says, yes, you have irritable bowel syndrome, or no, you don’t. We might suggest things that are helpful for some people and are less helpful for others.”

Dr. Kelly said she worries that “there are snake oil salesmen and cons out there who will gladly take your money. These may be smart people, capable of doing very high-level testing, and even producing very detailed and accurate results, but that doesn’t mean we know what to do with them.”

She hopes to see a microbiome-based diagnostic test in the future, particularly if the ability to therapeutically manipulate the gut microbiome in various diseases becomes a reality.

Educate Clinicians, Companies

More education is needed on the subject, so we can become “microbial clinicians,” Dr. Kao said.