User login

For MD-IQ use only

Botulinum Toxin for the Treatment of Intractable Raynaud Phenomenon

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

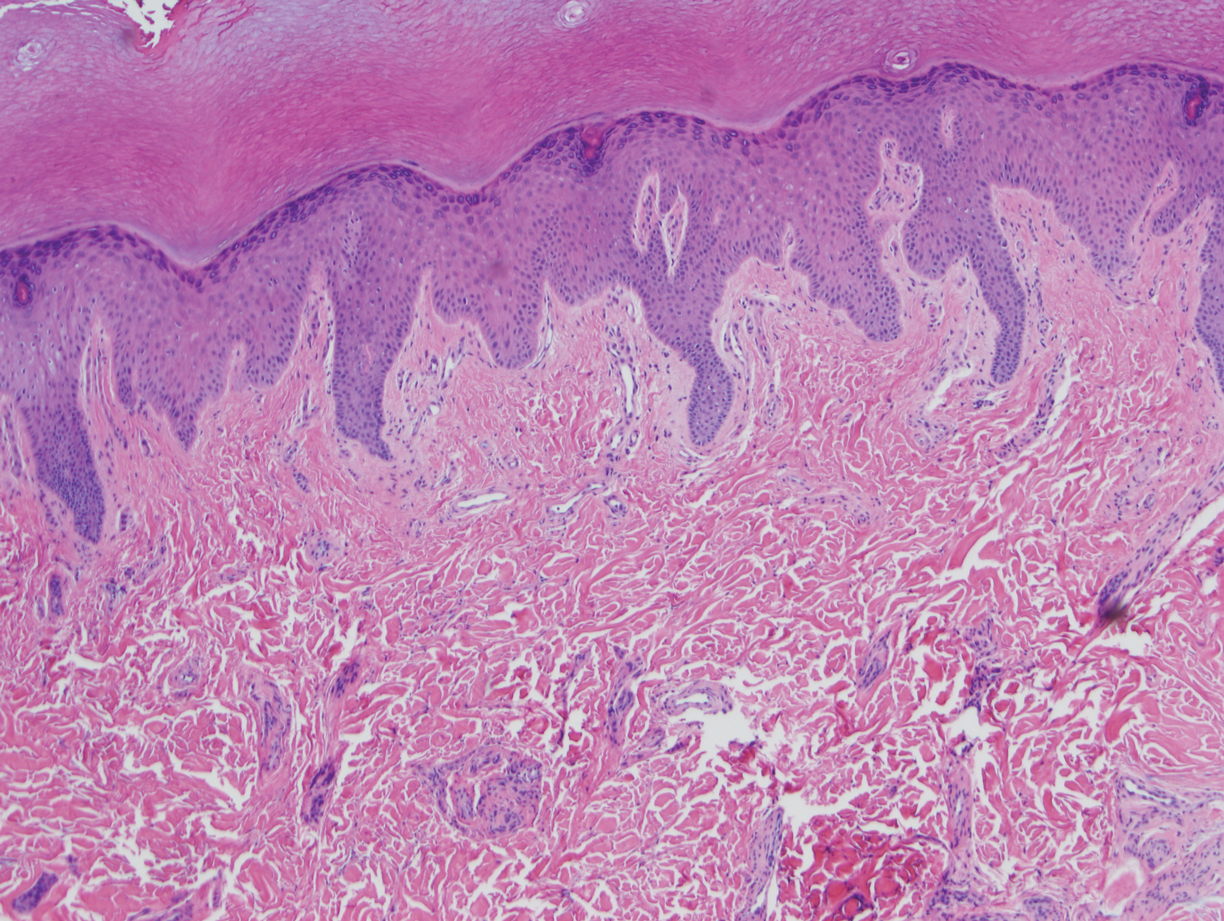

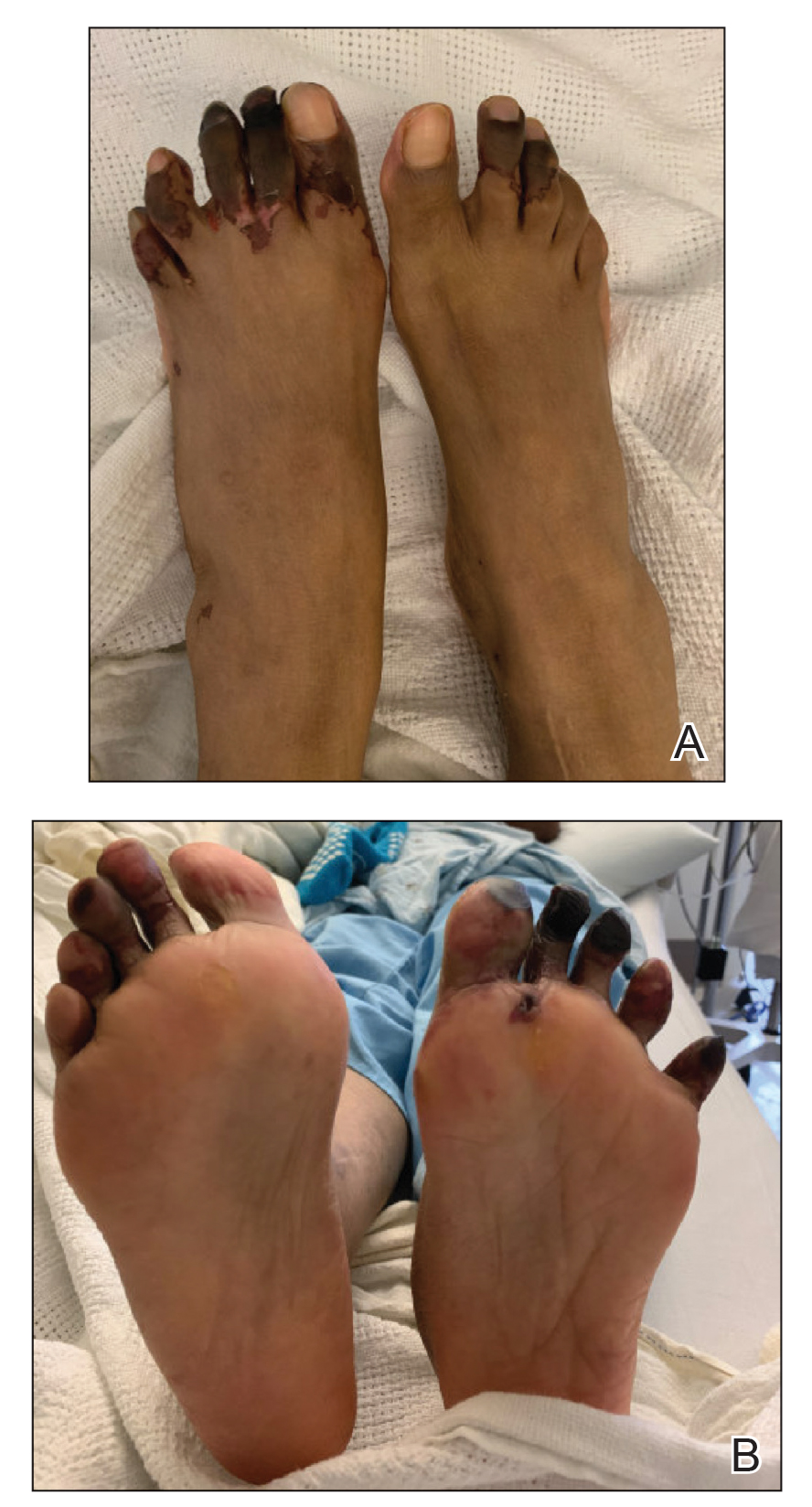

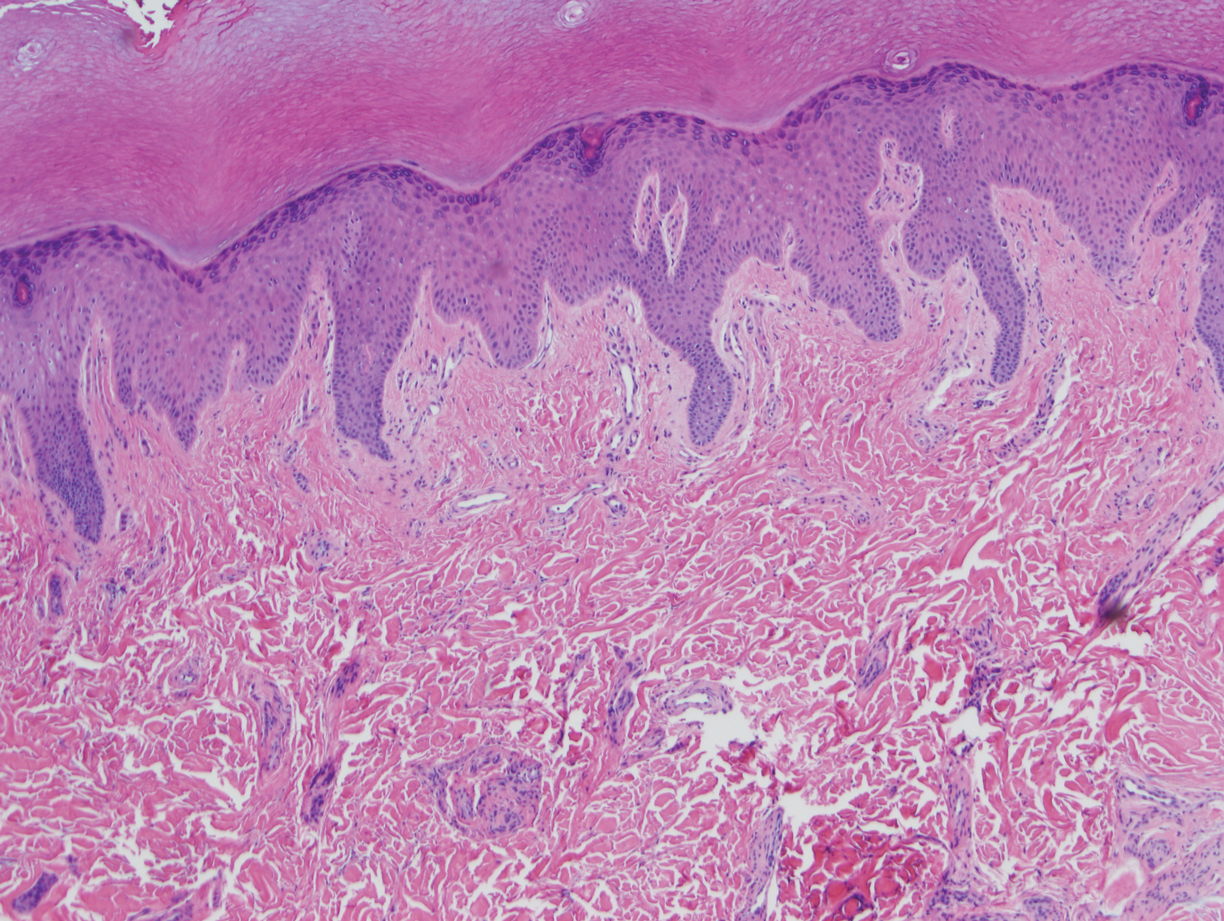

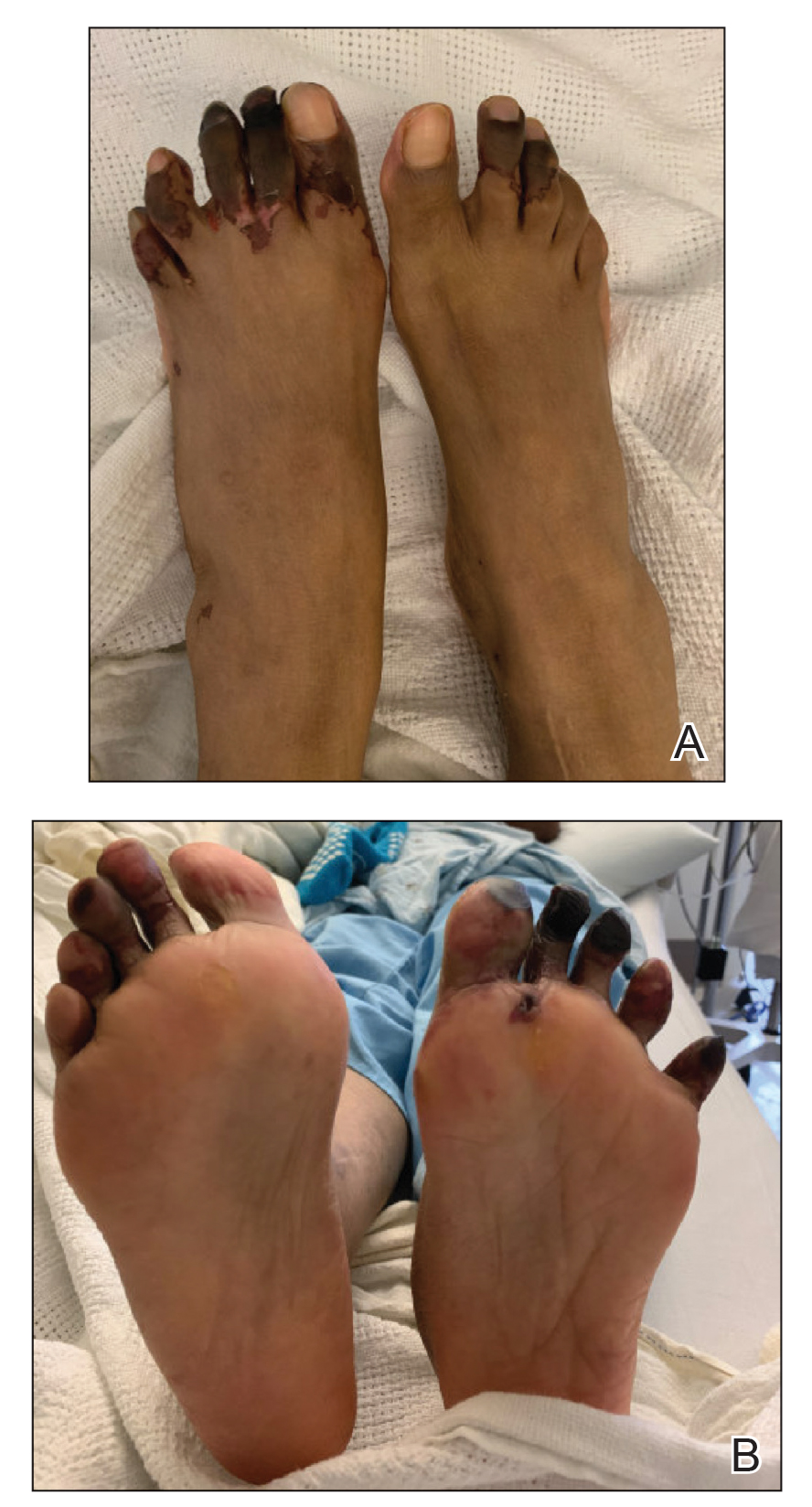

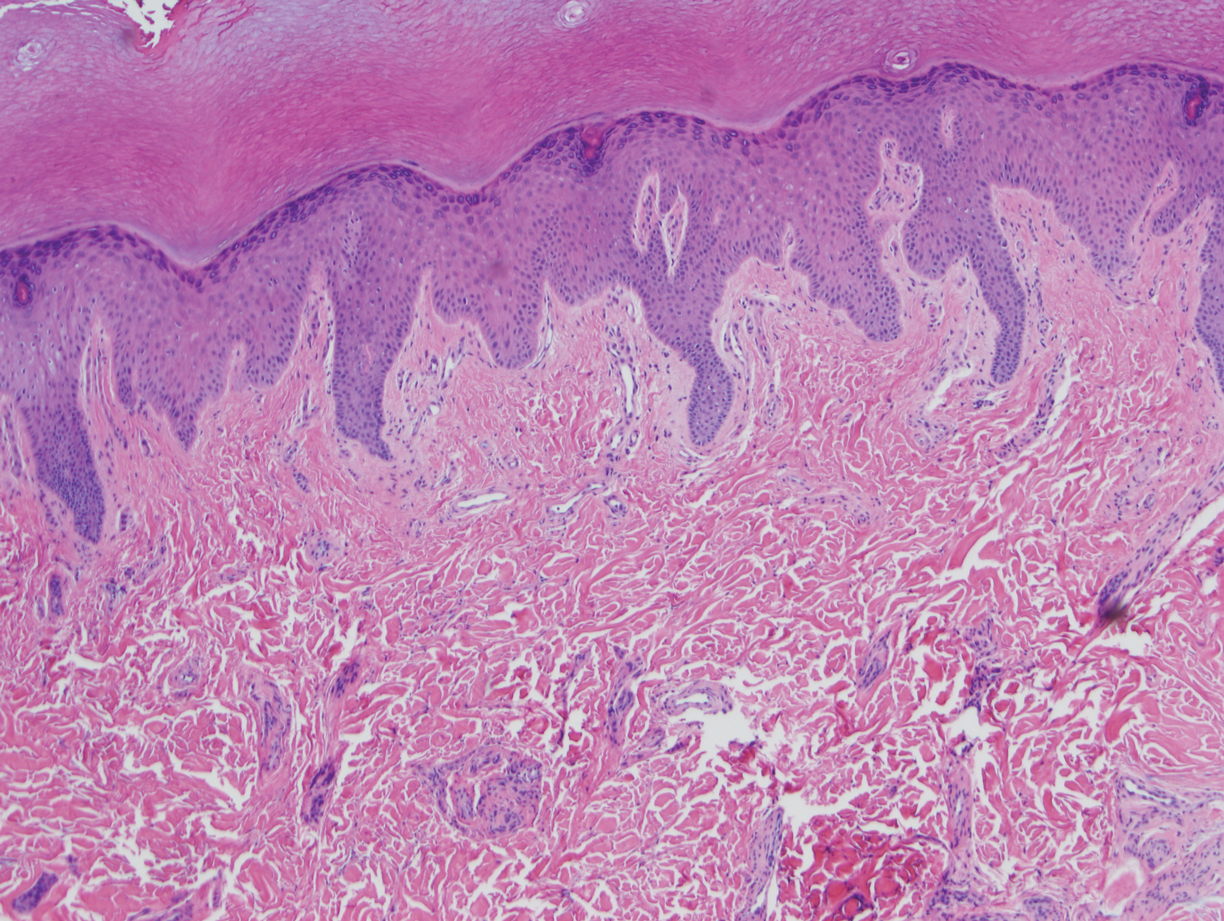

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

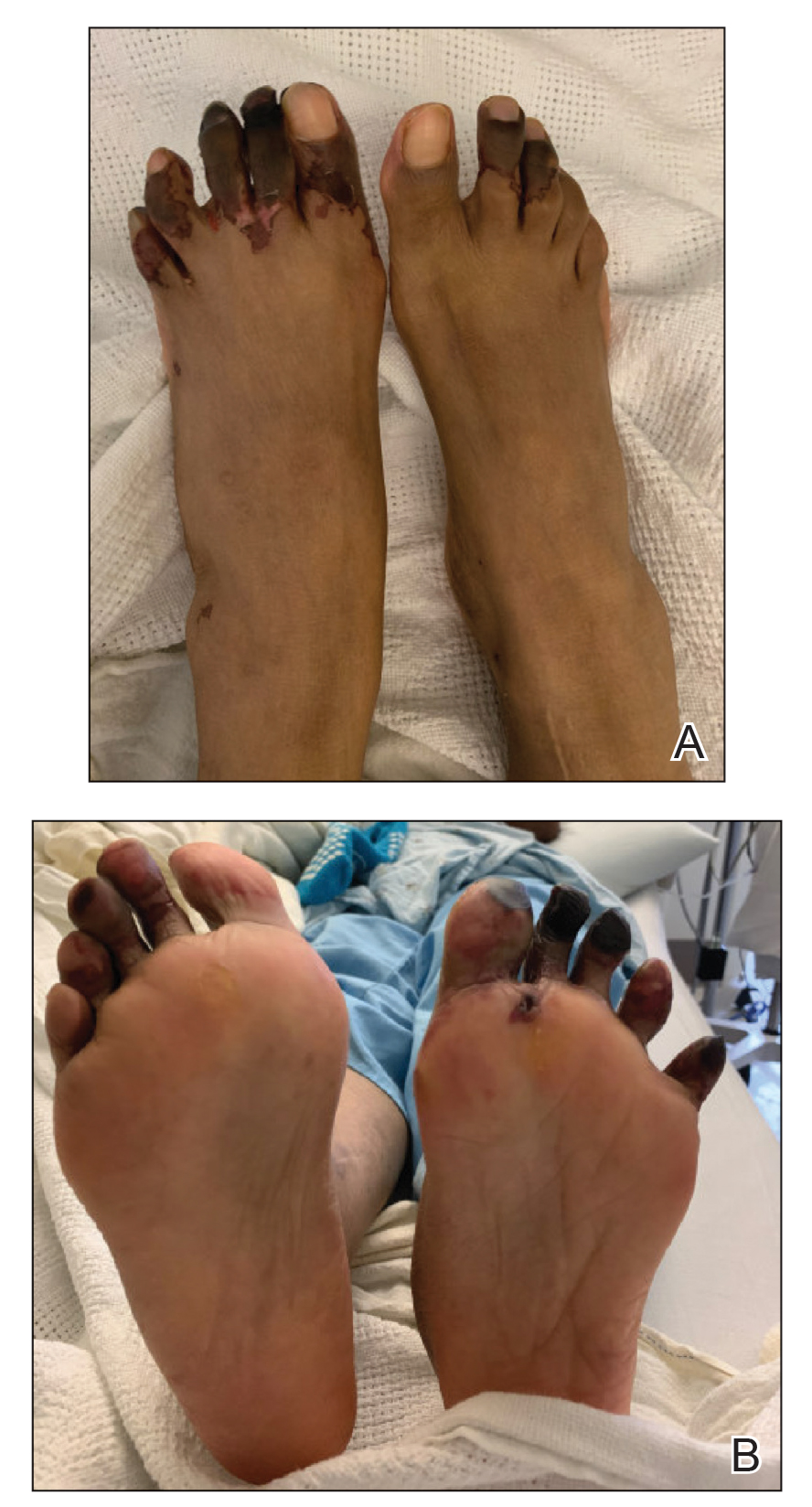

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

Practice Points

- Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is a vascular disorder characterized by episodic vasospasms of the digits often due to cold temperature or stress.

- OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP after failure with traditional treatments, such as calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, prostaglandins, endothelin receptor blockers, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors.

- A standard technique of delivery of onabotulinumtoxinA involves injection of 5 U/mL into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base (near the metacarpal head) for a total of 50 U per hand or foot.

New finasteride lawsuit brings renewed attention to psychiatric, ED adverse event reports

A new merit a closer look and, potentially, better counseling and monitoring from clinicians.

The nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen filed the suit on behalf of the Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation (PFSF) in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The PFSF had filed a citizen’s petition in 2017 that requested that the FDA either take the 1-mg formulation off the market, or add warnings about the potential for erectile dysfunction, depression, and suicidal ideation, among other adverse reactions.

The PFSF has alleged that long-term use of Propecia (and its generic equivalents) can lead to postfinasteride syndrome (PFS), characterized by sexual dysfunction and psycho-neurocognitive symptoms. The symptoms may continue long after men stop taking the drug, according to PFSF.

Public Citizen said the FDA needs to take action in part because U.S. prescriptions of the hair loss formulation “more than doubled from 2015 to 2020,” and online and telemedicine companies such as Hims, Roman, and Keeps “aggressively market and sell generic finasteride for hair loss.” According to GoodRx, a 1-month supply of generic 1-mg tablets costs as little as $8-$10.

Both Canadian and British regulatory authorities have added warnings about depression and suicide to the Propecia label but the FDA has not changed its labeling. An agency spokesperson told this news organization that the “FDA does not comment on the status of pending citizen petitions or on pending litigation.”

Propecia’s developer, Merck, has not responded to several requests for comment from this news organization.

Why some patients develop PFS and others do not is still not understood, but some clinicians said they counsel all patients on the risks of severe and persistent side effects that have been associated with Propecia.

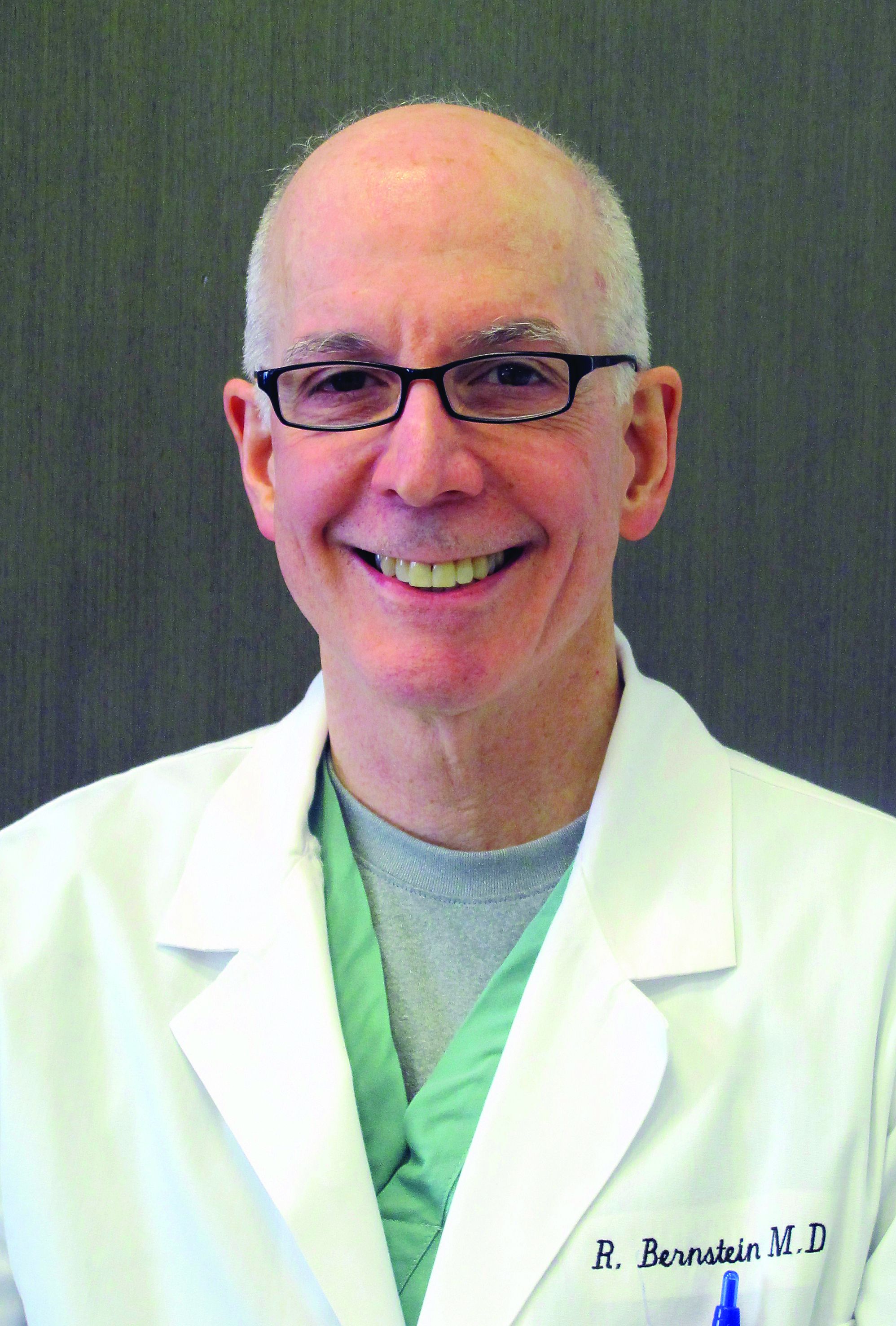

Robert M. Bernstein, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University, New York, and a fellow of the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, said that 2%-4% of his patients have some side effects, similar to the original reported incidence, with sexual dysfunction being the most common.

If a man experiences an adverse effect, the drug should be stopped, Dr. Bernstein said in an interview. He noted that “there seems to be a significant increased risk of persistent side effects in people with certain psychiatric conditions, and those people should be counseled carefully before considering the medication.”

“Everybody should be warned that the risk of persistent side effects is real but in the average person it is quite uncommon,” added Dr. Bernstein, founder of Bernstein Medical, a division of Schweiger Dermatology Group focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of hair loss. “I don’t think it should be withdrawn from the market,” he said.

Alan Jacobs, MD, a Manhattan-based neuroendocrinologist and behavioral neurologist in private practice who said he has treated hundreds of men for PFS, and who is an expert witness for the plaintiff in a suit alleging that finasteride led to a man’s suicide, said that taking the drug off the market would be unfortunate because it helps so many men. “I don’t think you need to get rid of the drug per se,” he said in an interview. “But very rapidly, people need to do clinical research to find out how to predict who’s more at risk,” he added.

Michael S. Irwig, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has studied the persistent sexual and nonsexual side effects of finasteride, said he believes there should be a boxed warning on the finasteride label to let the men who take it “know that they can have permanent persistent sexual dysfunction, and/or depression and suicide have been noted with this medicine.

“Those who prescribe it should be having a conversation with patients about the potential risks and benefits so that everybody knows about the potential before they get on the medicine,” said Dr. Irwig, who also is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Other countries warn of psychiatric effects

The FDA approved the 1-mg form of finasteride for male pattern hair loss in 1997.

In 2012, the label and the patient insert were updated to state that side effects included less desire for sex, erectile dysfunction, and a decrease in the amount of semen produced, but that those adverse events occurred in less than 2% of men and generally went away in most men who stopped taking the drug.

That label change unleashed a flood of more than 1,000 lawsuits against Merck. The company reportedly settled at least half of them for $4.3 million in 2018. The Superior Court of New Jersey closed out the consolidated class action against Merck in May 2021, noting that all of the cases had been settled or dismissed.

The suits generally accused Merck of not giving adequate warning about sexual side effects, according to an investigation by Reuters. That 2019 special report found that Merck had understated the number of men who experienced sexual side effects and the duration of those symptoms. The news organization also reported that from 2009 to 2018, the FDA received 5,000 reports of sexual or mental health side effects – and sometimes both – in men who took finasteride. Some 350 of the men reported suicidal thoughts, and there were 50 reports of suicide.

Public Citizen’s lawsuit alleges that VigiBase, which is managed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, lists 378 cases of suicidal ideation, 39 cases of suicide attempt, and 88 cases of completed suicide associated with finasteride use. VigiBase collects data from 153 countries on adverse reactions to medications.

In February 2021, more documents from the class action lawsuits were unsealed in response to a Reuters request. According to the news organization, the documents showed that Merck knew of reports of depression, including suicidal thoughts, as early as 2009.

However, according to Reuters, the FDA in 2011 granted Merck’s request to only note depression as a potential side effect, without including the risk of suicidal ideation.

The current FDA label notes a small incidence of sexual dysfunction, including decreased libido (1.8% in trials) and erectile dysfunction (1.3%) and mentions depression as a side effect observed during the postmarketing period.

The Canadian label has the same statistics on sexual side effects but is much stronger on mental adverse effects: “Psychiatric disorders: mood alterations and depression, decreased libido that continued after discontinuation of treatment. Mood alterations including depressed mood and, less frequently, suicidal ideation have been reported in patients treated with finasteride 1 mg. Patients should be monitored for psychiatric symptoms, and if these occur, the patient should be advised to seek medical advice.”

In the United Kingdom, patients prescribed the drug are given a leaflet, which notes that “Mood alterations such as depressed mood, depression and, less frequently, suicidal thoughts have been reported in patients treated with Propecia,” and advises patients to stop taking the drug if they experience any of those symptoms and to discuss it with their physician.

Public Citizen noted in its lawsuit that French and German drug regulators have sent letters to clinicians advising them to inform patients of the risk of suicidal thoughts and anxiety.

Is there biological plausibility?

To bolster its argument that finasteride has dangerous psychiatric side effects, the advocacy organization cited a study first published in JAMA Dermatology in late 2020 that investigated suicidality and psychological adverse events in patients taking finasteride.

David-Dan Nguyen, MPH, and his colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Montreal, examined the VigiBase database and found 356 cases of suicidality and 2,926 psychological adverse events; cases were highest from 2015 to 2019.

They documented what they called a “significant disproportionality signal for suicidality (reporting odds ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.90-4.15) and psychological adverse events (ROR, 4.33; 95% CI, 4.17-4.49) with finasteride, especially in younger men and those with alopecia, but not in older men or those with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The study authors noted that some studies have suggested that men with depression have low levels of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, which is produced by the 5-alpha reductase enzyme. Finasteride is a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

According to Public Citizen’s lawsuit, “The product labeling does not disclose important information about finasteride’s mechanism of action,” and “the drug inhibits multiple steroid hormone pathways that are responsible for the formation of brain neurosteroids that regulate many critical functions in the central nervous system, like sexual function, mood, sleep, cognitive function, the stress response, and motivation.”

Dr. Jacobs said that “there’s a lot of good solid high-quality research, mostly in animals, but also some on humans, showing a plausible link between blocking 5-alpha reductase in the brain, deficiency of neuroactive steroids, and depression.”

The author of an accompanying editorial, Roger S. Ho, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of dermatology, New York University, was skeptical. “Without a plausible biological hypothesis pharmacodynamically linking the drug and the reported adverse event, this kind of analysis may lead to false findings,” Dr. Ho said in the editorial about the Nguyen study.

Dr. Ho also wrote that he believed that the lack of a suicidality signal for dutasteride, a drug with a similar mechanism of action, but without as much media attention, “hints at a potential reporting bias unique to finasteride.”

He recommended that clinicians “conduct a full evaluation and a detailed, personalized risk-benefit assessment for patients before each prescription of finasteride.”

Important medicine, important caveats

Dr. Jacobs said that many of the men who come to him with side effects after taking finasteride have “been blown off by most of the doctors they go to see.”

Urologists dismiss them because their sexual dysfunction is not a gonad issue. They are told that it’s in their head, said Dr. Jacobs, adding that, “it is in their head, but it’s biological.”

The drug’s label advises that sexual side effects disappear when the drug is stopped. “That’s only true most of the time, not all of the time,” said Dr. Jacobs, adding that the persistence of any side effects impacts what he calls a “small subset” of men who take the drug.

“We have treated tens of thousands of patients who have benefited from the medicine and had no side effects,” said Dr. Bernstein. “But there is a lot that’s still not known about it.”

Even so, “baldness in young people is not a benign condition,” he said, adding that it can be socially debilitating. “An 18-year-old with a full head of thick hair who’s totally bald in 3 or 4 years – that can totally change his psyche,” Dr. Bernstein said. Finasteride may be the best option for those young men, and it is an important medication, he said. Does it need to be used more carefully? “Certainly you can’t argue with that,” he commented.

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Irwig reported no conflicts. Dr. Jacobs disclosed that he is an expert witness for the plaintiffs in a suit against Propecia maker Merck.

A new merit a closer look and, potentially, better counseling and monitoring from clinicians.

The nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen filed the suit on behalf of the Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation (PFSF) in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The PFSF had filed a citizen’s petition in 2017 that requested that the FDA either take the 1-mg formulation off the market, or add warnings about the potential for erectile dysfunction, depression, and suicidal ideation, among other adverse reactions.

The PFSF has alleged that long-term use of Propecia (and its generic equivalents) can lead to postfinasteride syndrome (PFS), characterized by sexual dysfunction and psycho-neurocognitive symptoms. The symptoms may continue long after men stop taking the drug, according to PFSF.

Public Citizen said the FDA needs to take action in part because U.S. prescriptions of the hair loss formulation “more than doubled from 2015 to 2020,” and online and telemedicine companies such as Hims, Roman, and Keeps “aggressively market and sell generic finasteride for hair loss.” According to GoodRx, a 1-month supply of generic 1-mg tablets costs as little as $8-$10.

Both Canadian and British regulatory authorities have added warnings about depression and suicide to the Propecia label but the FDA has not changed its labeling. An agency spokesperson told this news organization that the “FDA does not comment on the status of pending citizen petitions or on pending litigation.”

Propecia’s developer, Merck, has not responded to several requests for comment from this news organization.

Why some patients develop PFS and others do not is still not understood, but some clinicians said they counsel all patients on the risks of severe and persistent side effects that have been associated with Propecia.

Robert M. Bernstein, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University, New York, and a fellow of the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, said that 2%-4% of his patients have some side effects, similar to the original reported incidence, with sexual dysfunction being the most common.

If a man experiences an adverse effect, the drug should be stopped, Dr. Bernstein said in an interview. He noted that “there seems to be a significant increased risk of persistent side effects in people with certain psychiatric conditions, and those people should be counseled carefully before considering the medication.”

“Everybody should be warned that the risk of persistent side effects is real but in the average person it is quite uncommon,” added Dr. Bernstein, founder of Bernstein Medical, a division of Schweiger Dermatology Group focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of hair loss. “I don’t think it should be withdrawn from the market,” he said.

Alan Jacobs, MD, a Manhattan-based neuroendocrinologist and behavioral neurologist in private practice who said he has treated hundreds of men for PFS, and who is an expert witness for the plaintiff in a suit alleging that finasteride led to a man’s suicide, said that taking the drug off the market would be unfortunate because it helps so many men. “I don’t think you need to get rid of the drug per se,” he said in an interview. “But very rapidly, people need to do clinical research to find out how to predict who’s more at risk,” he added.

Michael S. Irwig, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has studied the persistent sexual and nonsexual side effects of finasteride, said he believes there should be a boxed warning on the finasteride label to let the men who take it “know that they can have permanent persistent sexual dysfunction, and/or depression and suicide have been noted with this medicine.

“Those who prescribe it should be having a conversation with patients about the potential risks and benefits so that everybody knows about the potential before they get on the medicine,” said Dr. Irwig, who also is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Other countries warn of psychiatric effects

The FDA approved the 1-mg form of finasteride for male pattern hair loss in 1997.

In 2012, the label and the patient insert were updated to state that side effects included less desire for sex, erectile dysfunction, and a decrease in the amount of semen produced, but that those adverse events occurred in less than 2% of men and generally went away in most men who stopped taking the drug.

That label change unleashed a flood of more than 1,000 lawsuits against Merck. The company reportedly settled at least half of them for $4.3 million in 2018. The Superior Court of New Jersey closed out the consolidated class action against Merck in May 2021, noting that all of the cases had been settled or dismissed.

The suits generally accused Merck of not giving adequate warning about sexual side effects, according to an investigation by Reuters. That 2019 special report found that Merck had understated the number of men who experienced sexual side effects and the duration of those symptoms. The news organization also reported that from 2009 to 2018, the FDA received 5,000 reports of sexual or mental health side effects – and sometimes both – in men who took finasteride. Some 350 of the men reported suicidal thoughts, and there were 50 reports of suicide.

Public Citizen’s lawsuit alleges that VigiBase, which is managed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, lists 378 cases of suicidal ideation, 39 cases of suicide attempt, and 88 cases of completed suicide associated with finasteride use. VigiBase collects data from 153 countries on adverse reactions to medications.

In February 2021, more documents from the class action lawsuits were unsealed in response to a Reuters request. According to the news organization, the documents showed that Merck knew of reports of depression, including suicidal thoughts, as early as 2009.

However, according to Reuters, the FDA in 2011 granted Merck’s request to only note depression as a potential side effect, without including the risk of suicidal ideation.

The current FDA label notes a small incidence of sexual dysfunction, including decreased libido (1.8% in trials) and erectile dysfunction (1.3%) and mentions depression as a side effect observed during the postmarketing period.

The Canadian label has the same statistics on sexual side effects but is much stronger on mental adverse effects: “Psychiatric disorders: mood alterations and depression, decreased libido that continued after discontinuation of treatment. Mood alterations including depressed mood and, less frequently, suicidal ideation have been reported in patients treated with finasteride 1 mg. Patients should be monitored for psychiatric symptoms, and if these occur, the patient should be advised to seek medical advice.”

In the United Kingdom, patients prescribed the drug are given a leaflet, which notes that “Mood alterations such as depressed mood, depression and, less frequently, suicidal thoughts have been reported in patients treated with Propecia,” and advises patients to stop taking the drug if they experience any of those symptoms and to discuss it with their physician.

Public Citizen noted in its lawsuit that French and German drug regulators have sent letters to clinicians advising them to inform patients of the risk of suicidal thoughts and anxiety.

Is there biological plausibility?

To bolster its argument that finasteride has dangerous psychiatric side effects, the advocacy organization cited a study first published in JAMA Dermatology in late 2020 that investigated suicidality and psychological adverse events in patients taking finasteride.

David-Dan Nguyen, MPH, and his colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Montreal, examined the VigiBase database and found 356 cases of suicidality and 2,926 psychological adverse events; cases were highest from 2015 to 2019.

They documented what they called a “significant disproportionality signal for suicidality (reporting odds ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.90-4.15) and psychological adverse events (ROR, 4.33; 95% CI, 4.17-4.49) with finasteride, especially in younger men and those with alopecia, but not in older men or those with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The study authors noted that some studies have suggested that men with depression have low levels of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, which is produced by the 5-alpha reductase enzyme. Finasteride is a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

According to Public Citizen’s lawsuit, “The product labeling does not disclose important information about finasteride’s mechanism of action,” and “the drug inhibits multiple steroid hormone pathways that are responsible for the formation of brain neurosteroids that regulate many critical functions in the central nervous system, like sexual function, mood, sleep, cognitive function, the stress response, and motivation.”

Dr. Jacobs said that “there’s a lot of good solid high-quality research, mostly in animals, but also some on humans, showing a plausible link between blocking 5-alpha reductase in the brain, deficiency of neuroactive steroids, and depression.”

The author of an accompanying editorial, Roger S. Ho, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of dermatology, New York University, was skeptical. “Without a plausible biological hypothesis pharmacodynamically linking the drug and the reported adverse event, this kind of analysis may lead to false findings,” Dr. Ho said in the editorial about the Nguyen study.

Dr. Ho also wrote that he believed that the lack of a suicidality signal for dutasteride, a drug with a similar mechanism of action, but without as much media attention, “hints at a potential reporting bias unique to finasteride.”

He recommended that clinicians “conduct a full evaluation and a detailed, personalized risk-benefit assessment for patients before each prescription of finasteride.”

Important medicine, important caveats

Dr. Jacobs said that many of the men who come to him with side effects after taking finasteride have “been blown off by most of the doctors they go to see.”

Urologists dismiss them because their sexual dysfunction is not a gonad issue. They are told that it’s in their head, said Dr. Jacobs, adding that, “it is in their head, but it’s biological.”

The drug’s label advises that sexual side effects disappear when the drug is stopped. “That’s only true most of the time, not all of the time,” said Dr. Jacobs, adding that the persistence of any side effects impacts what he calls a “small subset” of men who take the drug.

“We have treated tens of thousands of patients who have benefited from the medicine and had no side effects,” said Dr. Bernstein. “But there is a lot that’s still not known about it.”

Even so, “baldness in young people is not a benign condition,” he said, adding that it can be socially debilitating. “An 18-year-old with a full head of thick hair who’s totally bald in 3 or 4 years – that can totally change his psyche,” Dr. Bernstein said. Finasteride may be the best option for those young men, and it is an important medication, he said. Does it need to be used more carefully? “Certainly you can’t argue with that,” he commented.

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Irwig reported no conflicts. Dr. Jacobs disclosed that he is an expert witness for the plaintiffs in a suit against Propecia maker Merck.

A new merit a closer look and, potentially, better counseling and monitoring from clinicians.

The nonprofit advocacy group Public Citizen filed the suit on behalf of the Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation (PFSF) in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The PFSF had filed a citizen’s petition in 2017 that requested that the FDA either take the 1-mg formulation off the market, or add warnings about the potential for erectile dysfunction, depression, and suicidal ideation, among other adverse reactions.

The PFSF has alleged that long-term use of Propecia (and its generic equivalents) can lead to postfinasteride syndrome (PFS), characterized by sexual dysfunction and psycho-neurocognitive symptoms. The symptoms may continue long after men stop taking the drug, according to PFSF.

Public Citizen said the FDA needs to take action in part because U.S. prescriptions of the hair loss formulation “more than doubled from 2015 to 2020,” and online and telemedicine companies such as Hims, Roman, and Keeps “aggressively market and sell generic finasteride for hair loss.” According to GoodRx, a 1-month supply of generic 1-mg tablets costs as little as $8-$10.

Both Canadian and British regulatory authorities have added warnings about depression and suicide to the Propecia label but the FDA has not changed its labeling. An agency spokesperson told this news organization that the “FDA does not comment on the status of pending citizen petitions or on pending litigation.”

Propecia’s developer, Merck, has not responded to several requests for comment from this news organization.

Why some patients develop PFS and others do not is still not understood, but some clinicians said they counsel all patients on the risks of severe and persistent side effects that have been associated with Propecia.

Robert M. Bernstein, MD, of the department of dermatology at Columbia University, New York, and a fellow of the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, said that 2%-4% of his patients have some side effects, similar to the original reported incidence, with sexual dysfunction being the most common.

If a man experiences an adverse effect, the drug should be stopped, Dr. Bernstein said in an interview. He noted that “there seems to be a significant increased risk of persistent side effects in people with certain psychiatric conditions, and those people should be counseled carefully before considering the medication.”

“Everybody should be warned that the risk of persistent side effects is real but in the average person it is quite uncommon,” added Dr. Bernstein, founder of Bernstein Medical, a division of Schweiger Dermatology Group focusing on the diagnosis and treatment of hair loss. “I don’t think it should be withdrawn from the market,” he said.

Alan Jacobs, MD, a Manhattan-based neuroendocrinologist and behavioral neurologist in private practice who said he has treated hundreds of men for PFS, and who is an expert witness for the plaintiff in a suit alleging that finasteride led to a man’s suicide, said that taking the drug off the market would be unfortunate because it helps so many men. “I don’t think you need to get rid of the drug per se,” he said in an interview. “But very rapidly, people need to do clinical research to find out how to predict who’s more at risk,” he added.

Michael S. Irwig, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who has studied the persistent sexual and nonsexual side effects of finasteride, said he believes there should be a boxed warning on the finasteride label to let the men who take it “know that they can have permanent persistent sexual dysfunction, and/or depression and suicide have been noted with this medicine.

“Those who prescribe it should be having a conversation with patients about the potential risks and benefits so that everybody knows about the potential before they get on the medicine,” said Dr. Irwig, who also is an endocrinologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Other countries warn of psychiatric effects

The FDA approved the 1-mg form of finasteride for male pattern hair loss in 1997.

In 2012, the label and the patient insert were updated to state that side effects included less desire for sex, erectile dysfunction, and a decrease in the amount of semen produced, but that those adverse events occurred in less than 2% of men and generally went away in most men who stopped taking the drug.

That label change unleashed a flood of more than 1,000 lawsuits against Merck. The company reportedly settled at least half of them for $4.3 million in 2018. The Superior Court of New Jersey closed out the consolidated class action against Merck in May 2021, noting that all of the cases had been settled or dismissed.

The suits generally accused Merck of not giving adequate warning about sexual side effects, according to an investigation by Reuters. That 2019 special report found that Merck had understated the number of men who experienced sexual side effects and the duration of those symptoms. The news organization also reported that from 2009 to 2018, the FDA received 5,000 reports of sexual or mental health side effects – and sometimes both – in men who took finasteride. Some 350 of the men reported suicidal thoughts, and there were 50 reports of suicide.

Public Citizen’s lawsuit alleges that VigiBase, which is managed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring, lists 378 cases of suicidal ideation, 39 cases of suicide attempt, and 88 cases of completed suicide associated with finasteride use. VigiBase collects data from 153 countries on adverse reactions to medications.

In February 2021, more documents from the class action lawsuits were unsealed in response to a Reuters request. According to the news organization, the documents showed that Merck knew of reports of depression, including suicidal thoughts, as early as 2009.

However, according to Reuters, the FDA in 2011 granted Merck’s request to only note depression as a potential side effect, without including the risk of suicidal ideation.

The current FDA label notes a small incidence of sexual dysfunction, including decreased libido (1.8% in trials) and erectile dysfunction (1.3%) and mentions depression as a side effect observed during the postmarketing period.

The Canadian label has the same statistics on sexual side effects but is much stronger on mental adverse effects: “Psychiatric disorders: mood alterations and depression, decreased libido that continued after discontinuation of treatment. Mood alterations including depressed mood and, less frequently, suicidal ideation have been reported in patients treated with finasteride 1 mg. Patients should be monitored for psychiatric symptoms, and if these occur, the patient should be advised to seek medical advice.”

In the United Kingdom, patients prescribed the drug are given a leaflet, which notes that “Mood alterations such as depressed mood, depression and, less frequently, suicidal thoughts have been reported in patients treated with Propecia,” and advises patients to stop taking the drug if they experience any of those symptoms and to discuss it with their physician.

Public Citizen noted in its lawsuit that French and German drug regulators have sent letters to clinicians advising them to inform patients of the risk of suicidal thoughts and anxiety.

Is there biological plausibility?

To bolster its argument that finasteride has dangerous psychiatric side effects, the advocacy organization cited a study first published in JAMA Dermatology in late 2020 that investigated suicidality and psychological adverse events in patients taking finasteride.

David-Dan Nguyen, MPH, and his colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, McGill University, Montreal, and the University of Montreal, examined the VigiBase database and found 356 cases of suicidality and 2,926 psychological adverse events; cases were highest from 2015 to 2019.

They documented what they called a “significant disproportionality signal for suicidality (reporting odds ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 2.90-4.15) and psychological adverse events (ROR, 4.33; 95% CI, 4.17-4.49) with finasteride, especially in younger men and those with alopecia, but not in older men or those with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The study authors noted that some studies have suggested that men with depression have low levels of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, which is produced by the 5-alpha reductase enzyme. Finasteride is a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

According to Public Citizen’s lawsuit, “The product labeling does not disclose important information about finasteride’s mechanism of action,” and “the drug inhibits multiple steroid hormone pathways that are responsible for the formation of brain neurosteroids that regulate many critical functions in the central nervous system, like sexual function, mood, sleep, cognitive function, the stress response, and motivation.”

Dr. Jacobs said that “there’s a lot of good solid high-quality research, mostly in animals, but also some on humans, showing a plausible link between blocking 5-alpha reductase in the brain, deficiency of neuroactive steroids, and depression.”

The author of an accompanying editorial, Roger S. Ho, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the department of dermatology, New York University, was skeptical. “Without a plausible biological hypothesis pharmacodynamically linking the drug and the reported adverse event, this kind of analysis may lead to false findings,” Dr. Ho said in the editorial about the Nguyen study.

Dr. Ho also wrote that he believed that the lack of a suicidality signal for dutasteride, a drug with a similar mechanism of action, but without as much media attention, “hints at a potential reporting bias unique to finasteride.”

He recommended that clinicians “conduct a full evaluation and a detailed, personalized risk-benefit assessment for patients before each prescription of finasteride.”

Important medicine, important caveats

Dr. Jacobs said that many of the men who come to him with side effects after taking finasteride have “been blown off by most of the doctors they go to see.”

Urologists dismiss them because their sexual dysfunction is not a gonad issue. They are told that it’s in their head, said Dr. Jacobs, adding that, “it is in their head, but it’s biological.”

The drug’s label advises that sexual side effects disappear when the drug is stopped. “That’s only true most of the time, not all of the time,” said Dr. Jacobs, adding that the persistence of any side effects impacts what he calls a “small subset” of men who take the drug.

“We have treated tens of thousands of patients who have benefited from the medicine and had no side effects,” said Dr. Bernstein. “But there is a lot that’s still not known about it.”

Even so, “baldness in young people is not a benign condition,” he said, adding that it can be socially debilitating. “An 18-year-old with a full head of thick hair who’s totally bald in 3 or 4 years – that can totally change his psyche,” Dr. Bernstein said. Finasteride may be the best option for those young men, and it is an important medication, he said. Does it need to be used more carefully? “Certainly you can’t argue with that,” he commented.

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Irwig reported no conflicts. Dr. Jacobs disclosed that he is an expert witness for the plaintiffs in a suit against Propecia maker Merck.

Guideline gives weak support to trying oral medical cannabis for chronic pain

“Evidence alone is not sufficient for clinical decision-making, particularly in chronic pain,” said Jason Busse, DC, PhD, director of Michael G. DeGroote Centre for Medicinal Cannabis Research at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and lead author of a newly released rapid guideline on medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain.

The recommendations, published online Sept. 9, 2021 in the British Medical Journal, suggest that providers offer patients with chronic pain a trial of noninhaled medical cannabis or cannabinoids if standard care or management is ineffective. However, the “weak” rating attached to the recommendation may compel some clinicians to automatically write off the panel’s recommendations.

“Because of the close balance between benefits and harms and wide variability in patient attitudes, the panel came to the conclusion that [some] patients presented with the current best evidence would likely choose to engage in a trial of medicinal cannabis, if their current care was felt to be suboptimal,” Dr. Busse explained in an interview.

But more importantly, “the recommendation allows for shared decision making to occur, and for different patients to make different decisions based on individual preferences and circumstances,” he said.

Evidence supports improved pain and sleep quality, physical functioning

Evidence supporting the use of medical cannabis in chronic pain is derived from a rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 studies enrolling 5,174 patients randomized to oral (capsule, spray, sublingual drops) or topical (transdermal cream) medical cannabis or placebo. Of note, three types of cannabinoids were represented: phytocannabinoids, synthetic, and endocannabinoids.

The studies included both patients with chronic noncancer pain (28 studies, n = 3,812) and chronic cancer pain not receiving palliative care (4 studies, n = 1,362). On average, baseline pain scores were a median 6.28 cm on a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS), and median participant age was 53 years. 60% of trials reporting sex differences enrolled female participants. Overall, patients were followed for roughly 2 months (median, 50 days).

Findings (27 studies, n = 3,939) showed that, compared with placebo, medical cannabis resulted in a small, albeit important, improvement in the proportion of patients experiencing pain relief at or above the minimally important difference (MID) (moderate-certainty evidence, 10% modeled risk difference [RD; 95% confidence interval, 5%-15%] for achieving at least the MID of 1 cm).

Medical cannabis (15 studies, n = 2,425) also provided a small increase in the proportion of patients experiencing improvements in physical functioning at or above the MID (high certainty evidence, 4% modeled RD [95% CI, 0.1%-8%] for achieving at least a MID of 10 points).

Additionally, participants experienced significant improvements in sleep quality, compared with placebo (16 studies, 3,124 participants, high-quality evidence), demonstrating a weighted mean difference of –0.53 cm on a 10-cm VAS (95% CI, –0.75 to –0.30 cm). A total of nine larger trials (n = 2,652, high-certainty evidence) saw a small increase in the proportion of patients experiencing improved sleep quality at or above the MID: 6% modeled RD (95% CI, 2%-9%).

On the other hand, benefits did not extend to emotional, role, or social functioning (high-certainty evidence).

First do no harm: Start low, go slow

While these findings provide a rationale for medical cannabis in chronic pain, exploring options with patients can be challenging. Studies on medical cannabis consistently note that patients want information, but data also show that many providers express a lack of knowledge to provide adequate counseling.

There are also legal hurdles. Despite the authorization of medicinal cannabis across a majority of states and territories, cannabis is still a schedule I substance under the Federal Controlled Substances Act. In addition, the absence of standards around formulations, potency, and dosing has also been cited as a major barrier to recommending medical cannabis, as have concerns about adverse events (AEs), especially with inhaled and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-predominant formulations.

Like most medications, medical cannabis dosing should be individualized depending on product, patient, and ability to titrate the dose, but the guidelines provide a general rule of thumb. Providers considering therapeutic noninhaled medical cannabis trials are encouraged to start with a low-dose cannabidiol (CBD) oral tablet, spray, or sublingual oil drops 5 mg twice daily, increasing it by 10 mg every 2-3 days depending on the clinical response (to a maximum daily dose of 40 mg/day). If patient response is unsatisfactory, they should consider adding 1-2.5 mg THC/daily, titrated every 2-7 days to a maximum of 40 mg/day.

Still, an important caveat is whether or not adjunctive CBD alone is effective for chronic pain.

“While we know that one out of seven U.S. adults are using cannabidiol, we know very little about its therapeutic effects when given by itself for pain,” Ziva Cooper, PhD, director of the Cannabis Research Initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an associate professor at-large of psychology and behavioral science, said in an interview. (Dr. Cooper was not involved in the guideline development.)

“But patients tend to self-report that CBD is helpful, and at low doses, we know that it is unlikely to have adverse effects of any significant concern,” Dr. Cooper noted.

Depending on its components, medical cannabis is associated with a wide range of AEs. Studies comprising the evidence base for the guideline reported transient cognitive impairment (relative risk, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.06-5.38), vomiting (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-1.99), and drowsiness (RR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.55-2.95), attention impairment (RR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.67-9.74), and nausea (RR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.28-1.99). Of note, findings of a subgroup analysis showed that the risk of dizziness increased with treatment duration, starting at 3 months (test of interaction P = .002).

However, Dr. Cooper explained that, because the included studies were inconsistent in terms of cannabis type (e.g., some looked at synthetic THC or THC-like substances where others looked at a THC/CBD combination) and formulation (capsules, oral mucosal sprays), it’s difficult to tease out component-specific AEs.