User login

For MD-IQ use only

Autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: Treatment options

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Evidence supports the crucial role of early intervention and nonpharmacologic approaches

A large percentage of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience persisting significant social deficits in adulthood,1 which often leads to isolation, depressive symptoms, and poor occupational and relationship functioning.2,3 Childhood is a vital time for making the most significant and lasting changes that can improve functioning of individuals with ASD. Psychiatrists and other physicians who treat children are in a key role to influence outcomes of children at risk for or diagnosed with ASD.

This article provides updates on various aspects of ASD diagnosis and treatment (based on available evidence up to March 2020). Part 1 (

A comprehensive approach is essential

Multiple treatment modalities have been recommended for ASD.5 It is essential to address all aspects of ASD through cognitive, developmental, social-communication, sensory-motor, and behavioral interventions. Nonpharmacologic interventions are crucial in improving long-term outcomes of children with ASD.6

Nonpharmacologic treatments

Nonpharmacologic interventions commonly utilized for children with ASD include behavioral therapies, other psychological therapies, speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, educational interventions, parent coaching/training, developmental social interventions, and other modalities of therapy that are delivered in school, home, and clinic settings.5,7

A recent study examining ASD treatment trends via caregivers’ reports (N = 5,122) from the SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge) cohort in the United States reported that 80% of children received speech-language therapy or occupational therapy; 52% got both.5 The study revealed that approximately one-quarter utilized 3 therapies simultaneously; two-thirds had utilized 3 or more therapies in the previous year.5

Interventions for children with ASD need to be individualized.1,8 Evidence-based behavioral interventions for ASD fall into 2 broad categories: Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), and Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBI). Traditionally, ABA has been a key model, guiding treatment for enhancing social-communicating skills and lowering maladaptive behaviors in ASD.9 ABA follows a structured and prescribed format,10,11 and has been shown to be efficacious.1,7 More recently, NDBI, in which interventions are “embedded” in the natural environment of the young child and more actively incorporate a developmental perspective, has been shown to be beneficial in improving and generalizing social-communication skills in young children with ASD.7,11

Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is an intensive, naturalistic behavioral intervention4 that has been shown to be efficacious for enhancing communication and adaptive behavior in children with ASD.7,8,12 A multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Rogers et al12 that examined the efficacy of ESDM in 118 children (age 14 to 24 months) with ASD found the treatment was beneficial and superior compared with a “community intervention” group, in regards to language ability measured in time by group analyses.The ESDM intervention in this study involved weekly parent coaching for 3 months, along with 24 months of 15 hours/week of one-on-one treatment provided by therapy professionals.12

Reciprocal imitation training (RIT) is another naturalistic intervention that has shown benefit in training children with ASD in imitation skills during play.13 Studies have found that both RIT and ESDM can be parent-implemented, after parents receive training.13,14

Parent-mediated, parent-implemented interventions may have a role in improving outcomes in childhood ASD,7,15 particularly “better generalization and maintenance of skills than therapist-implemented intervention” for lowering challenging behaviors and enhancing verbal and nonverbal communication.16

Various social skills interventions have also been found effective for children with ASD.1 Such interventions are often provided in the school setting.7 Coordination with the child’s school to discuss and advocating for adequate and suitable interventions, educational services, and placement is an essential aspect of ASD treatment.7

Two other school-based, comprehensive treatment model interventions—Learning Experiences and Alternative Programs for Preschoolers and their Parents (LEAP), and TEACCH—have some evidence of leading to improvement in children with ASD.7,17

Some studies have found that music therapy may have high efficacy for children with ASD, even with smaller length and intensity of treatment, particularly in improving social interaction, engagement with parents, joint attention, and communication.3,18 Further research is needed to conclusively establish the efficacy of music therapy for ASD in children and adolescents.

A few studies have assessed the long-term outcomes of interventions for ASD; however, more research is needed.19 Pickles et al19 conducted a follow-up to determine the long-term effects of the Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT), an RCT of parent-mediated social communication therapy for children age 2 to 4 with ASD. The children’s average age at follow-up was 10 years. The authors found a significant long-term decrease in ASD symptoms and enhancement of social communication with parents (N = 152).

Technology-based interventions, including games and robotics, have been investigated in recent years, for treatment of children with ASD (eg, for improving social skills).20

Research suggests that the intensity (number of hours) and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments for ASD is critical to improving outcomes (Box1,3,5,7,10,16).

Box

A higher intensity of nonpharmacologic intervention (greater number of hours) has been associated with greater benefit for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), in the form of enhancements in IQ and adaptive behavior.1,10,16 In the United States, the intensity of interventions commonly ranges from 30 to 200 or more minutes per week.3 This may mean that a child with ASD who is receiving 30 minutes of speech therapy at school and continues to exhibit significant deficits in speech-language or social-communication may likely benefit from additional hours of speech therapy and/or social-communication skill training, and should be referred accordingly, even for private therapy services if needed and feasible.7 Guidelines created through a systematic review of evidence recommend at least 25 hours per week of comprehensive treatment interventions for children with ASD to address language, social deficits, and behavioral difficulties.1 The duration of intervention has also been shown to play a role in outcomes.1,3,10 Given the complexity and extent of impairment often associated with ASD, it is not surprising that in recent research examining trends in ASD treatment in the United States, most caregivers reported therapy as ongoing.5 The exact intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic interventions may depend on several factors, such as severity of ASD and of the specific deficit being targeted, type of intervention, and therapist skill. The quality of skills of the care provider has also been shown to affect the benefits gained from the intervention.3

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy...

Pharmacotherapy

Medications cannot resolve core features of ASD.21 However, certain medications may help address associated comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, or others, when these conditions have not responded to nonpharmacologic interventions.7,22 Common symptoms that are often treated with pharmacotherapy include aggression, irritability, hyperactivity, attentional difficulties, tics, self-injurious behavior, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and mood dysregulation/lability.23 Generally speaking, medications might be considered if symptoms are severe and markedly impair functioning. For mild to moderate conditions, psychotherapy and other nonpharmacologic interventions are generally considered first-line. Since none of the medications described below are specific to ASD and psychiatrists generally receive training in prescribing them for other indications, a comprehensive review of their risks and benefits is beyond the scope of this article. No psychotropic medications are known to have robust evidence for safety in preschool children with ASD, and thus are best avoided.

Antipsychotics. Risperidone (for age 5 and older) and aripiprazole (age 6 to 17) are the only medications FDA-approved for use in children and adolescents with ASD, specifically for irritability associated with ASD.21,24 These 2 second-generation antipsychotics may also assist in lowering aggression in patients with ASD.24 First-generation antipsychotics such as haloperidol have been shown to be effective for irritability and aggression in ASD, but the risk of significant adverse effects such as dyskinesias and extrapyramidal symptoms limit their use.24 Two studies (a double-blind study and an open-label extension of that study) in children and adolescents with ASD found that risperidone was more effective and better tolerated than haloperidol in behavioral measures, impulsivity, and even in the social domain.25,26 In addition to other adverse effects and risks, increased prolactin secondary to risperidone use requires close monitoring and caution.24-26 As is the case with the use of other psychotropic medications in children and adolescents, those with ASD who receive antipsychotics should also be periodically reassessed to determine the need for continued use of these medications.27 A multicenter relapse prevention RCT found no statistically significant difference in the time to relapse between aripiprazole and placebo.27 Metabolic syndrome, cardiac risks, and other risks need to be considered before prescribing an antipsychotic.28 Given their serious adverse effects profile, use should be considered only when there is severe impairment or risk of injury, after carefully weighing risks/benefits.

Medications for attentional difficulties. A multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the use of extended-release guanfacine in children with ASD (N = 62) found the rate of positive response on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale was 50% for guanfacine vs 9.4% for placebo.29 Clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects of guanfacine, such as fatigue, drowsiness, lightheadedness, lowering of blood pressure and heart rate, and other effects.29 A randomized, double-blind trial of 97 children and adolescents with ASD and ADHD found that atomoxetine had moderate benefit for ADHD symptoms.30 The study reported no serious adverse effects.30 However, it is especially important to monitor for hepatic and cardiac adverse effects (in addition to monitoring for risk of increase in suicidal thoughts/behavior, as in the case of antidepressants) when using atomoxetine, in addition to other side effects and risks. Some evidence suggests that methylphenidate may be effective for attentional difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD21 but may pose a higher risk of adverse effects in this population compared with neurotypical patients.31

Antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are sometimes used to reduce obsessive-compulsive symptoms, repetitive behavior, or depressive symptoms in children with ASD, but are not FDA-approved for children or adolescents with ASD. In general, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of SSRIs for ASD in children.31-34 In addition, children with ASD may be at a greater risk of adverse effects from SSRIs.32,34 Despite this, SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications in children with ASD.32

An RCT examining the efficacy of fluoxetine in 158 children and adolescents with ASD found no significant difference in Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) score after 14 weeks of treatment; activation was a common adverse effect.35 A 2005 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 45 children/adolescents with ASD found that low-dose liquid fluoxetine was more effective than placebo for reducing repetitive behaviors in this population.36 Larger studies are warranted to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine (and of SSRIs in general, particularly in the long term) for children and adolescents with ASD.36 A 2009 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 149 children with ASD revealed no significant difference between citalopram and placebo as measured by Clinical Global Impressions scale or CY-BOCS scores, and noted a significantly elevated likelihood of adverse effects.37

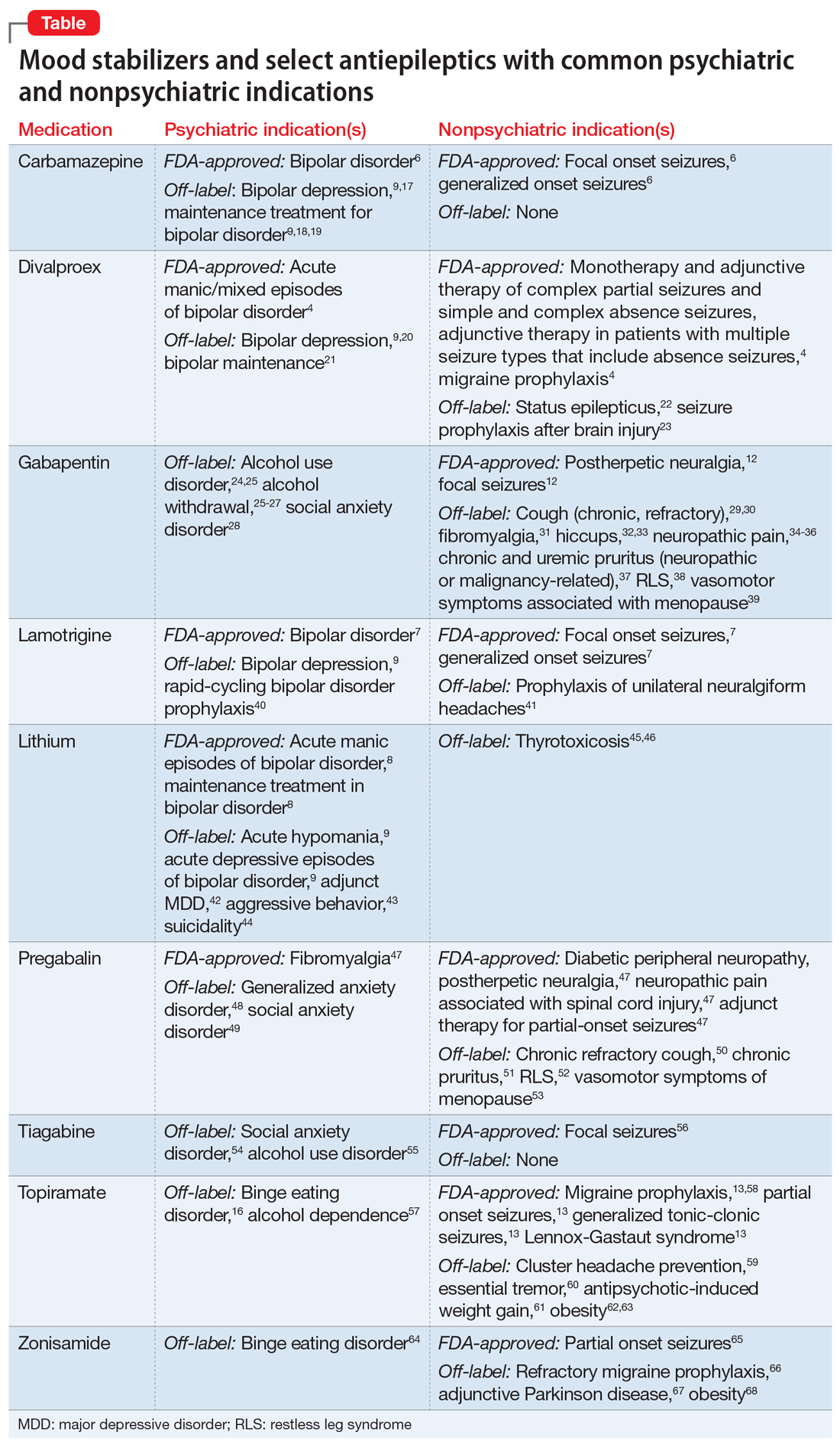

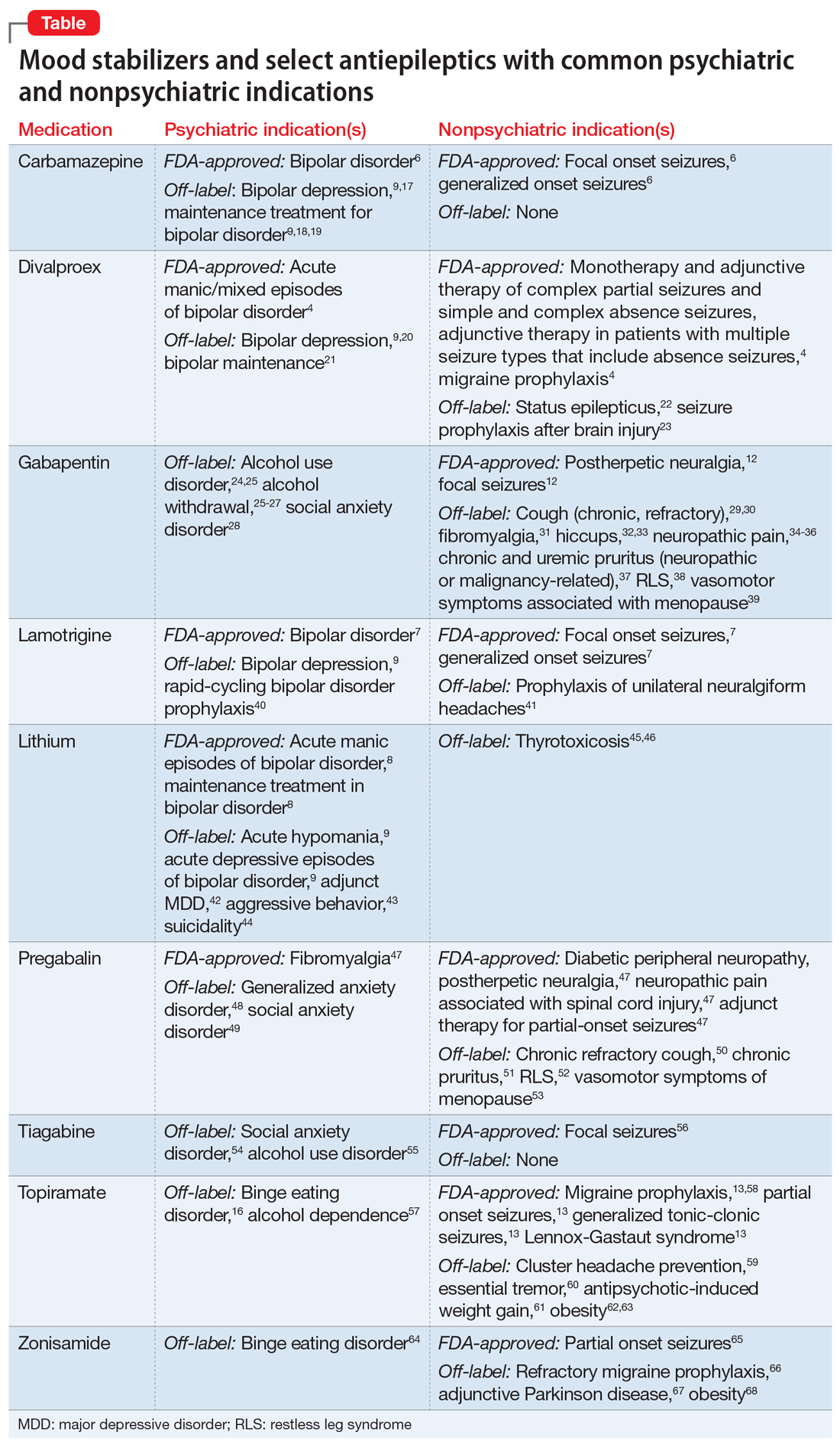

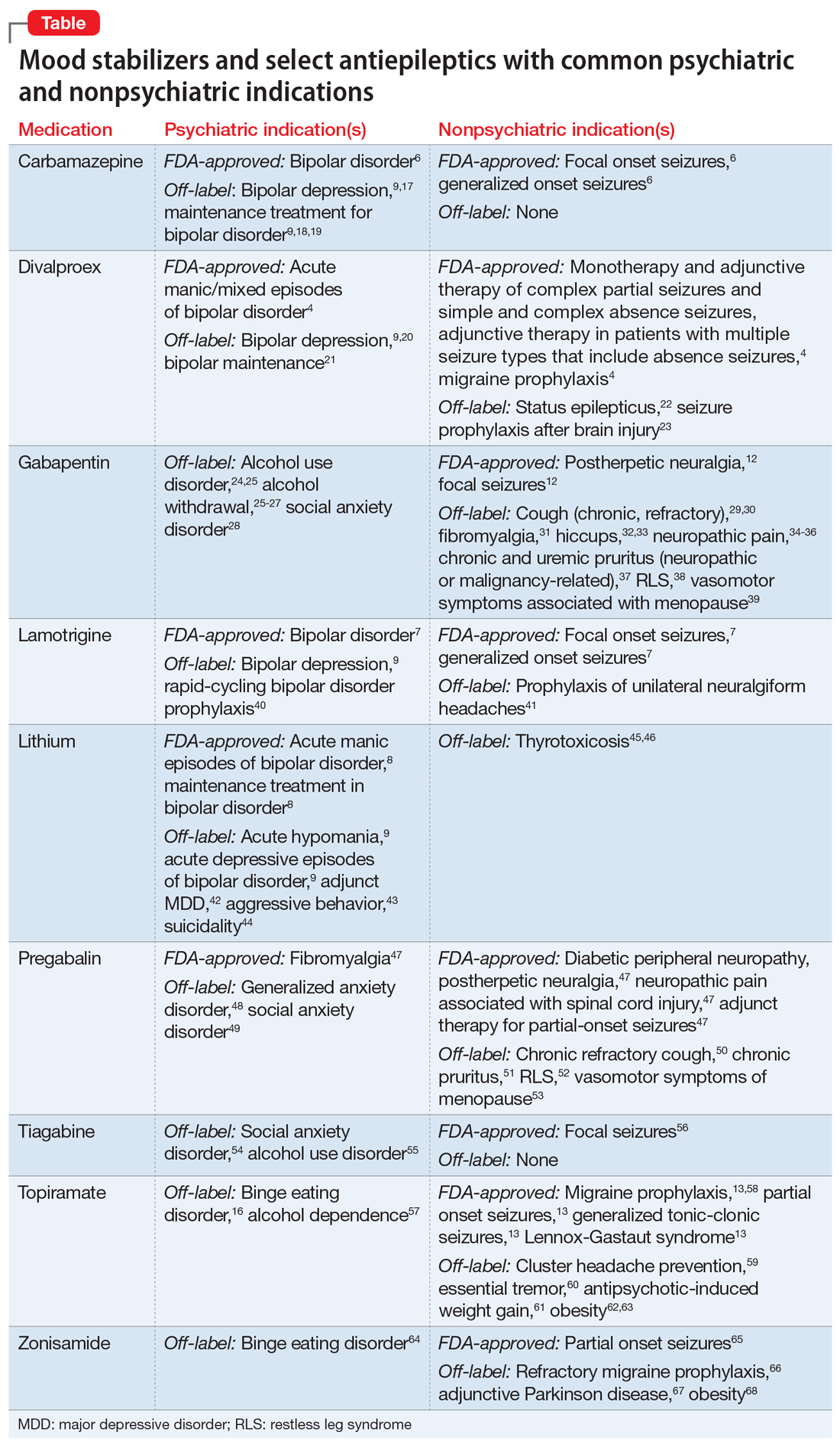

Other antidepressants. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of any other antidepressants in children and adolescents with ASD. A few studies38,39 have examined the use of venlafaxine in children with ASD; however, further research and controlled studies with large sample sizes are required to conclusively establish its benefits. There is a dearth of evidence examining the use of the tetracyclic antidepressant mirtazapine, or other classes of medications such as tricyclic antidepressants or mood stabilizers, in children with ASD; only a few small studies have assessed the efficacy and adverse effects of these medications for such patients.31

Polypharmacy. Although there is no evidence to support polypharmacy in children and adolescents with ASD, the practice appears to be rampant in these patients.28,40 A 2013 retrospective, observational study of psychotropic medication use in children with ASD (N = 33,565) found that 64% were prescribed psychotropic medications, and 35% exhibited evidence of polypharmacy.40 In this study, the total duration of polypharmacy averaged 525 days.40 When addressing polypharmacy, systematic deprescribing or simplification of the psychotropic medication regimen may be needed,28 while taking into account the patient’s complete clinical situation, including (but not limited to) tolerability of the medication regimen, presence or absence of current stressors, presence or absence of adequate supports, use of nonpharmacologic treatments where appropriate, and other factors.

More studies assessing the efficacy and safety of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents with ASD are needed,32 especially studies that evaluate the effects of long-term use, because evidence for pharmacologic treatments for children with ASD is mixed and insufficient.33 There is also a need for evidence-based standards for prescribing psychotropic medications in children and adolescents with ASD.

Psychotropic medications, if used in ASD, should be used only in conjunction with other evidence-based treatment modalities, and not as monotherapy.21 Children and adolescents with ASD may be particularly susceptible to side effects or adverse effects of certain psychotropic medications.31 When considering medications, carefully weigh the risks and benefits.7,21,24,28 Starting low and going slow is generally the preferred strategy.31,32 As always, when recommending medications, discuss in detail with parents the potential side effects, benefits, risks, interactions, and alternatives.

Other agents. Several double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have evaluated using melatonin for sleep difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD.41 A randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial that assessed 160 children with ASD and insomnia found that melatonin plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was superior in efficacy to melatonin alone, CBT alone, or placebo.41

The evidence regarding oxytocin use for children with ASD is mixed.31 Some small studies have associated improvement in the social domain with its use. Guastella et al42 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oxytocin nasal spray for 16 participants (age 12 to 19) with ASD, and found oxytocin enhanced emotional identification. Gordon et al43 conducted a functional MRI study of brain activity with oxytocin use in children with high-functioning ASD (N = 17). They found that oxytocin may augment “salience and hedonic evaluations of socially meaningful stimuli in children with ASD” and thus help social attunement. Further research is needed to evaluate the impact of oxytocin on social behavior.

Complementary and alternative medicine. Although there is limited and inconclusive evidence about the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with ASD, these therapies continue to be commonly used.44-46 A recent survey of parents (N = 211) of children with ASD from academic ASD outpatient clinics in Germany found that 46% reported their child was using or had used some type of complementary and alternative medicine.44 There is inadequate evidence to support the use of a gluten-free, casein-free diet for children/adolescents with ASD.46 A recent cross-sectional study assessing supplement use in 210 children with ASD in Canada found that 75% used supplements, such as multivitamins (77.8%), vitamin D (44.9%), omega 3 (42.5%), probiotics (36.5%), and magnesium (28.1%), despite insufficient evidence to support their safety or efficacy for children with ASD.47 Importantly, 33.5% of parents in this study reported that they did not inform the physician about all their child’s supplements.47 Some of the reasons the parents in this study provided for not disclosing information about supplements to their physicians were “physician lack of knowledge,” “no benefit,” “too time-consuming,” and “scared of judgment.”47 Semi-structured interviews of parents of 21 children with ASD in Australia revealed that parents found information on complementary and alternative medicine and therapies complex and often conflicting.45 In addition to recommendations from health care professionals, evidence suggests that parents often consider the opinions of media, friends, and family when making a decision on using complementary and alternative medicine modalities for children/adolescents with ASD.46 Such findings can inform physician practices regarding supplement use, and highlight the need to educate parents about the evidence regarding these therapies and potential adverse effects and interactions of such therapies,46 along with the need to develop a centralized, evidence-based resource for parents regarding their use.45

Omega 3 supplementation has in general shown few adverse effects47; still, risks/benefits need to be weighed before use. Some evidence suggests that it may decrease hyperactivity in children with ASD.31,48 However, further research, particularly controlled trials with large sample sizes, are needed for a definitive determination of efficacy.31,48 A meta-analysis that included 27 RCTs assessing the efficacy of dietary interventions for various ASD symptoms found that omega 3 supplementation was more effective than placebo, but compared with placebo, the effect size was small.49 A RCT of 73 children with ASD in New Zealand found that omega 3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids may benefit some core symptoms of ASD; the authors suggested that further research is needed to conclusively establish efficacy.50

Continue to: A need for advocacy and research..

A need for advocacy and research

Physicians who treat children with ASD can not only make appropriate referrals and educate parents, but also educate their patients’ schools and advocate for their patients to get the level of services they need.23,28

A recent study in the United States found that behavior therapy and speech-language therapy were used less often in the treatment of children with ASD in rural areas compared with those in metro areas.5 This suggests that in addition to increasing parents’ awareness and use of ASD services and providing referrals where appropriate, physicians are in a unique position to advocate for public health policies to improve access, coverage, and training for the provision of such services in rural areas.

There is need for ongoing research to further examine the efficacy and nuances of effects of various treatment interventions for ASD, especially long-term studies with larger sample sizes.11,51 Additionally, research is warranted to better understand the underlying genetic and neurobiological mechanisms of ASD, which would help guide the development of biomarkers,52 innovative treatments, and disease-modifying agents for ASD.7,22 Exploring the effects of potential alliances or joint action between biological and psychosocial interventions for ASD is also an area that needs further research.51

Bottom Line

A combination of treatment modalities (such as speech-language therapy, social skills training, behavior therapy/other psychotherapy, and occupational therapy for sensory sensitivities) is generally needed to improve the long-term outcomes of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In addition to the importance of early intervention, the intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments are vital to improving outcomes in ASD.

1. Maglione MA, Gans D, Das L, et al. Nonmedical interventions for children with ASD: recommended guidelines and further research needs. Pediatrics. 2012;30(Suppl 2):S169-S178.

2. Simms MD, Jin XM. Autism, language disorder, and social (pragmatic) communication disorder: DSM-V and differential diagnoses. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(8):355-363. doi:10.1542/pir.36-8-355

3. Su Maw S, Haga C. Effectiveness of cognitive, developmental, and behavioural interventions for autism spectrum disorder in preschool-aged children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2018;4(9):e00763. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00763

4. Charman T. Editorial: trials and tribulations in early autism intervention research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(9):846-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.03.004

5. Monz BU, Houghton R, Law K, et al. Treatment patterns in children with autism in the United States. Autism Res. 2019;12(3):517-526. doi:10.1002/aur.2070

6. Sperdin HF, Schaer M. Aberrant development of speech processing in young children with autism: new insights from neuroimaging biomarkers. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:393. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00393

7. Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM, et al. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193447. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3447

8. Contaldo A, Colombi C, Pierotti C, et al. Outcomes and moderators of Early Start Denver Model intervention in young children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a mixed individual and group setting. Autism. 2020;24(3):718-729. doi:10.1177/1362361319888344

9. Lei J, Ventola P. Pivotal response treatment for autism spectrum disorder: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1613-1626. doi:10.2147/NDT.S120710

10. Landa RJ. Efficacy of early interventions for infants and young children with, and at risk for, autism spectrum disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(1):25-39. doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1432574

11. Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2411-2428. doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8

12. Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, et al. A multisite randomized controlled two-phase trial of the Early Start Denver Model compared to treatment as usual. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(9):853-865. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.01.004

13. Ingersoll B, Gergans S. The effect of a parent-implemented imitation intervention on spontaneous imitation skills in young children with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2007;28(2):163-175.

14. Waddington H, van der Meer L, Sigafoos J, et al. Examining parent use of specific intervention techniques during a 12-week training program based on the Early Start Denver Model. Autism. 2020;24(2):484-498. doi:10.1177/1362361319876495

15. Trembath D, Gurm M, Scheerer NE, et al. Systematic review of factors that may influence the outcomes and generalizability of parent‐mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2019;12(9):1304-1321.

16. Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, et al. Effects of a brief Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1052-1065. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003

17. Boyd BA, Hume K, McBee MT, et al. Comparative efficacy of LEAP, TEACCH and non-model-specific special education programs for preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(2):366-380. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1877-9

18. Thompson GA, McFerran KS, Gold C. Family-centred music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(6):840-852. doi:10.1111/cch.12121

19. Pickles A, Le Couteur A, Leadbitter K, et al. Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2501-2509.

20. Grossard C, Palestra G, Xavier J, et al. ICT and autism care: state of the art. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(6):474-483. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000455

21. Cukier S, Barrios N. Pharmacological interventions for intellectual disability and autism. Vertex. 2019;XXX(143)52-63.

22. Sharma SR, Gonda X, Tarazi FI. Autism spectrum disorder: classification, diagnosis and therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;190:91-104.

23. Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(2):237-257.

24. LeClerc S, Easley D. Pharmacological therapies for autism spectrum disorder: a review. P T. 2015;40(6):389-397.

25. Gencer O, Emiroglu FN, Miral S, et al. Comparison of long-term efficacy and safety of risperidone and haloperidol in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. An open label maintenance study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(4):217-225.

26. Miral S, Gencer O, Inal-Emiroglu FN, et al. Risperidone versus haloperidol in children and adolescents with AD: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(1):1-8.

27. Findling RL, Mankoski R, Timko K, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole in the long-term maintenance treatment of pediatric patients with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):22-30. doi:10.4088/jcp.13m08500

28. McLennan JD. Deprescribing in a youth with an intellectual disability, autism, behavioural problems, and medication-related obesity: a case study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(3):141-146.

29. Scahill L, McCracken JT, King B, et al. Extended-release guanfacine for hyperactivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1197-1206. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010055

30. Harfterkamp M, van de Loo-Neus G, Minderaa RB, et al. A randomized double-blind study of atomoxetine versus placebo for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(7):733-741. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.04.011

31. DeFilippis M, Wagner KD. Treatment of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2016;46(2):18-41.

32. DeFilippis M. Depression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Children (Basel). 2018;5(9):112. doi:10.3390/children5090112

33. Goel R, Hong JS, Findling RL, et al. An update on pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(1):78-95. doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1458706

34. Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD004677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004677.pub3

35. Herscu P, Handen BL, Arnold LE, et al. The SOFIA study: negative multi-center study of low dose fluoxetine on repetitive behaviors in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(9):3233-3244. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-04120-y

36. Hollander E, Phillips A, Chaplin W, et al. A placebo controlled crossover trial of liquid fluoxetine on repetitive behaviors in childhood and adolescent autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(3):582-589.

37. King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L, et al. Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):583-590. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.30

38. Hollander E, Kaplan A, Cartwright C, et al. Venlafaxine in children, adolescents, and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: an open retrospective clinical report. J Child Neurol. 2000;15(2):132-135.

39. Carminati GG, Deriaz N, Bertschy G. Low-dose venlafaxine in three adolescents and young adults with autistic disorder improves self-injurious behavior and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD)-like symptoms. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(2):312-315.

40. Spencer D, Marshall J, Post B, et al. Psychotropic medication use and polypharmacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):833-840. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3774

41. Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Sebastiani T, et al. Controlled-release melatonin, singly and combined with cognitive behavioural therapy, for persistent insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(6):700-709. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01021.x

42. Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, et al. Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):692-694. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020

43. Gordon I, Vander Wyk BC, Bennett RH, et al. Oxytocin enhances brain function in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(52):20953-20958. doi:10.1073/pnas.1312857110

44. Höfer J, Bachmann C, Kamp-Becker I, et al. Willingness to try and lifetime use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in Germany: a survey of parents. Autism. 2019;23(7):1865-1870. doi:10.1177/1362361318823545

45. Smith CA, Parton C, King M, et al. Parents’ experiences of information-seeking and decision-making regarding complementary medicine for children with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2805-0

46. Marsden REF, Francis J, Garner I. Use of GFCF diets in children with ASD. An investigation into parents’ beliefs using the theory of planned behaviour. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(9):3716-3731. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-04035-8

47. Trudeau MS, Madden RF, Parnell JA, et al. Dietary and supplement-based complementary and alternative medicine use in pediatric autism spectrum disorder. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1783. doi:10.3390/nu11081783

48. Bent S, Hendren RL, Zandi T, et al. Internet-based, randomized, controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for hyperactivity in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(6):658-666. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.018

49. Fraguas D, Díaz-Caneja C, Pina-Camacho L, et al. Dietary interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 144(5):e20183218.

50. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised-controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder in children. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(5):1778-1794. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3860-y

51. Green J, Garg S. Annual research review: the state of autism intervention science: progress, target psychological and biological mechanisms and future prospects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):424-443. doi:10.1111/jcpp.1289

52. Frye RE, Vassall S, Kaur G, et al. Emerging biomarkers in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(23):792. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.11.53

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Evidence supports the crucial role of early intervention and nonpharmacologic approaches

A large percentage of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience persisting significant social deficits in adulthood,1 which often leads to isolation, depressive symptoms, and poor occupational and relationship functioning.2,3 Childhood is a vital time for making the most significant and lasting changes that can improve functioning of individuals with ASD. Psychiatrists and other physicians who treat children are in a key role to influence outcomes of children at risk for or diagnosed with ASD.

This article provides updates on various aspects of ASD diagnosis and treatment (based on available evidence up to March 2020). Part 1 (

A comprehensive approach is essential

Multiple treatment modalities have been recommended for ASD.5 It is essential to address all aspects of ASD through cognitive, developmental, social-communication, sensory-motor, and behavioral interventions. Nonpharmacologic interventions are crucial in improving long-term outcomes of children with ASD.6

Nonpharmacologic treatments

Nonpharmacologic interventions commonly utilized for children with ASD include behavioral therapies, other psychological therapies, speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, educational interventions, parent coaching/training, developmental social interventions, and other modalities of therapy that are delivered in school, home, and clinic settings.5,7

A recent study examining ASD treatment trends via caregivers’ reports (N = 5,122) from the SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge) cohort in the United States reported that 80% of children received speech-language therapy or occupational therapy; 52% got both.5 The study revealed that approximately one-quarter utilized 3 therapies simultaneously; two-thirds had utilized 3 or more therapies in the previous year.5

Interventions for children with ASD need to be individualized.1,8 Evidence-based behavioral interventions for ASD fall into 2 broad categories: Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), and Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBI). Traditionally, ABA has been a key model, guiding treatment for enhancing social-communicating skills and lowering maladaptive behaviors in ASD.9 ABA follows a structured and prescribed format,10,11 and has been shown to be efficacious.1,7 More recently, NDBI, in which interventions are “embedded” in the natural environment of the young child and more actively incorporate a developmental perspective, has been shown to be beneficial in improving and generalizing social-communication skills in young children with ASD.7,11

Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is an intensive, naturalistic behavioral intervention4 that has been shown to be efficacious for enhancing communication and adaptive behavior in children with ASD.7,8,12 A multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Rogers et al12 that examined the efficacy of ESDM in 118 children (age 14 to 24 months) with ASD found the treatment was beneficial and superior compared with a “community intervention” group, in regards to language ability measured in time by group analyses.The ESDM intervention in this study involved weekly parent coaching for 3 months, along with 24 months of 15 hours/week of one-on-one treatment provided by therapy professionals.12

Reciprocal imitation training (RIT) is another naturalistic intervention that has shown benefit in training children with ASD in imitation skills during play.13 Studies have found that both RIT and ESDM can be parent-implemented, after parents receive training.13,14

Parent-mediated, parent-implemented interventions may have a role in improving outcomes in childhood ASD,7,15 particularly “better generalization and maintenance of skills than therapist-implemented intervention” for lowering challenging behaviors and enhancing verbal and nonverbal communication.16

Various social skills interventions have also been found effective for children with ASD.1 Such interventions are often provided in the school setting.7 Coordination with the child’s school to discuss and advocating for adequate and suitable interventions, educational services, and placement is an essential aspect of ASD treatment.7

Two other school-based, comprehensive treatment model interventions—Learning Experiences and Alternative Programs for Preschoolers and their Parents (LEAP), and TEACCH—have some evidence of leading to improvement in children with ASD.7,17

Some studies have found that music therapy may have high efficacy for children with ASD, even with smaller length and intensity of treatment, particularly in improving social interaction, engagement with parents, joint attention, and communication.3,18 Further research is needed to conclusively establish the efficacy of music therapy for ASD in children and adolescents.

A few studies have assessed the long-term outcomes of interventions for ASD; however, more research is needed.19 Pickles et al19 conducted a follow-up to determine the long-term effects of the Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT), an RCT of parent-mediated social communication therapy for children age 2 to 4 with ASD. The children’s average age at follow-up was 10 years. The authors found a significant long-term decrease in ASD symptoms and enhancement of social communication with parents (N = 152).

Technology-based interventions, including games and robotics, have been investigated in recent years, for treatment of children with ASD (eg, for improving social skills).20

Research suggests that the intensity (number of hours) and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments for ASD is critical to improving outcomes (Box1,3,5,7,10,16).

Box

A higher intensity of nonpharmacologic intervention (greater number of hours) has been associated with greater benefit for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), in the form of enhancements in IQ and adaptive behavior.1,10,16 In the United States, the intensity of interventions commonly ranges from 30 to 200 or more minutes per week.3 This may mean that a child with ASD who is receiving 30 minutes of speech therapy at school and continues to exhibit significant deficits in speech-language or social-communication may likely benefit from additional hours of speech therapy and/or social-communication skill training, and should be referred accordingly, even for private therapy services if needed and feasible.7 Guidelines created through a systematic review of evidence recommend at least 25 hours per week of comprehensive treatment interventions for children with ASD to address language, social deficits, and behavioral difficulties.1 The duration of intervention has also been shown to play a role in outcomes.1,3,10 Given the complexity and extent of impairment often associated with ASD, it is not surprising that in recent research examining trends in ASD treatment in the United States, most caregivers reported therapy as ongoing.5 The exact intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic interventions may depend on several factors, such as severity of ASD and of the specific deficit being targeted, type of intervention, and therapist skill. The quality of skills of the care provider has also been shown to affect the benefits gained from the intervention.3

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy...

Pharmacotherapy

Medications cannot resolve core features of ASD.21 However, certain medications may help address associated comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, or others, when these conditions have not responded to nonpharmacologic interventions.7,22 Common symptoms that are often treated with pharmacotherapy include aggression, irritability, hyperactivity, attentional difficulties, tics, self-injurious behavior, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and mood dysregulation/lability.23 Generally speaking, medications might be considered if symptoms are severe and markedly impair functioning. For mild to moderate conditions, psychotherapy and other nonpharmacologic interventions are generally considered first-line. Since none of the medications described below are specific to ASD and psychiatrists generally receive training in prescribing them for other indications, a comprehensive review of their risks and benefits is beyond the scope of this article. No psychotropic medications are known to have robust evidence for safety in preschool children with ASD, and thus are best avoided.

Antipsychotics. Risperidone (for age 5 and older) and aripiprazole (age 6 to 17) are the only medications FDA-approved for use in children and adolescents with ASD, specifically for irritability associated with ASD.21,24 These 2 second-generation antipsychotics may also assist in lowering aggression in patients with ASD.24 First-generation antipsychotics such as haloperidol have been shown to be effective for irritability and aggression in ASD, but the risk of significant adverse effects such as dyskinesias and extrapyramidal symptoms limit their use.24 Two studies (a double-blind study and an open-label extension of that study) in children and adolescents with ASD found that risperidone was more effective and better tolerated than haloperidol in behavioral measures, impulsivity, and even in the social domain.25,26 In addition to other adverse effects and risks, increased prolactin secondary to risperidone use requires close monitoring and caution.24-26 As is the case with the use of other psychotropic medications in children and adolescents, those with ASD who receive antipsychotics should also be periodically reassessed to determine the need for continued use of these medications.27 A multicenter relapse prevention RCT found no statistically significant difference in the time to relapse between aripiprazole and placebo.27 Metabolic syndrome, cardiac risks, and other risks need to be considered before prescribing an antipsychotic.28 Given their serious adverse effects profile, use should be considered only when there is severe impairment or risk of injury, after carefully weighing risks/benefits.

Medications for attentional difficulties. A multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the use of extended-release guanfacine in children with ASD (N = 62) found the rate of positive response on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale was 50% for guanfacine vs 9.4% for placebo.29 Clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects of guanfacine, such as fatigue, drowsiness, lightheadedness, lowering of blood pressure and heart rate, and other effects.29 A randomized, double-blind trial of 97 children and adolescents with ASD and ADHD found that atomoxetine had moderate benefit for ADHD symptoms.30 The study reported no serious adverse effects.30 However, it is especially important to monitor for hepatic and cardiac adverse effects (in addition to monitoring for risk of increase in suicidal thoughts/behavior, as in the case of antidepressants) when using atomoxetine, in addition to other side effects and risks. Some evidence suggests that methylphenidate may be effective for attentional difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD21 but may pose a higher risk of adverse effects in this population compared with neurotypical patients.31

Antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are sometimes used to reduce obsessive-compulsive symptoms, repetitive behavior, or depressive symptoms in children with ASD, but are not FDA-approved for children or adolescents with ASD. In general, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of SSRIs for ASD in children.31-34 In addition, children with ASD may be at a greater risk of adverse effects from SSRIs.32,34 Despite this, SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications in children with ASD.32

An RCT examining the efficacy of fluoxetine in 158 children and adolescents with ASD found no significant difference in Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) score after 14 weeks of treatment; activation was a common adverse effect.35 A 2005 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 45 children/adolescents with ASD found that low-dose liquid fluoxetine was more effective than placebo for reducing repetitive behaviors in this population.36 Larger studies are warranted to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine (and of SSRIs in general, particularly in the long term) for children and adolescents with ASD.36 A 2009 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 149 children with ASD revealed no significant difference between citalopram and placebo as measured by Clinical Global Impressions scale or CY-BOCS scores, and noted a significantly elevated likelihood of adverse effects.37

Other antidepressants. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of any other antidepressants in children and adolescents with ASD. A few studies38,39 have examined the use of venlafaxine in children with ASD; however, further research and controlled studies with large sample sizes are required to conclusively establish its benefits. There is a dearth of evidence examining the use of the tetracyclic antidepressant mirtazapine, or other classes of medications such as tricyclic antidepressants or mood stabilizers, in children with ASD; only a few small studies have assessed the efficacy and adverse effects of these medications for such patients.31

Polypharmacy. Although there is no evidence to support polypharmacy in children and adolescents with ASD, the practice appears to be rampant in these patients.28,40 A 2013 retrospective, observational study of psychotropic medication use in children with ASD (N = 33,565) found that 64% were prescribed psychotropic medications, and 35% exhibited evidence of polypharmacy.40 In this study, the total duration of polypharmacy averaged 525 days.40 When addressing polypharmacy, systematic deprescribing or simplification of the psychotropic medication regimen may be needed,28 while taking into account the patient’s complete clinical situation, including (but not limited to) tolerability of the medication regimen, presence or absence of current stressors, presence or absence of adequate supports, use of nonpharmacologic treatments where appropriate, and other factors.

More studies assessing the efficacy and safety of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents with ASD are needed,32 especially studies that evaluate the effects of long-term use, because evidence for pharmacologic treatments for children with ASD is mixed and insufficient.33 There is also a need for evidence-based standards for prescribing psychotropic medications in children and adolescents with ASD.

Psychotropic medications, if used in ASD, should be used only in conjunction with other evidence-based treatment modalities, and not as monotherapy.21 Children and adolescents with ASD may be particularly susceptible to side effects or adverse effects of certain psychotropic medications.31 When considering medications, carefully weigh the risks and benefits.7,21,24,28 Starting low and going slow is generally the preferred strategy.31,32 As always, when recommending medications, discuss in detail with parents the potential side effects, benefits, risks, interactions, and alternatives.

Other agents. Several double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have evaluated using melatonin for sleep difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD.41 A randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial that assessed 160 children with ASD and insomnia found that melatonin plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was superior in efficacy to melatonin alone, CBT alone, or placebo.41

The evidence regarding oxytocin use for children with ASD is mixed.31 Some small studies have associated improvement in the social domain with its use. Guastella et al42 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oxytocin nasal spray for 16 participants (age 12 to 19) with ASD, and found oxytocin enhanced emotional identification. Gordon et al43 conducted a functional MRI study of brain activity with oxytocin use in children with high-functioning ASD (N = 17). They found that oxytocin may augment “salience and hedonic evaluations of socially meaningful stimuli in children with ASD” and thus help social attunement. Further research is needed to evaluate the impact of oxytocin on social behavior.

Complementary and alternative medicine. Although there is limited and inconclusive evidence about the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with ASD, these therapies continue to be commonly used.44-46 A recent survey of parents (N = 211) of children with ASD from academic ASD outpatient clinics in Germany found that 46% reported their child was using or had used some type of complementary and alternative medicine.44 There is inadequate evidence to support the use of a gluten-free, casein-free diet for children/adolescents with ASD.46 A recent cross-sectional study assessing supplement use in 210 children with ASD in Canada found that 75% used supplements, such as multivitamins (77.8%), vitamin D (44.9%), omega 3 (42.5%), probiotics (36.5%), and magnesium (28.1%), despite insufficient evidence to support their safety or efficacy for children with ASD.47 Importantly, 33.5% of parents in this study reported that they did not inform the physician about all their child’s supplements.47 Some of the reasons the parents in this study provided for not disclosing information about supplements to their physicians were “physician lack of knowledge,” “no benefit,” “too time-consuming,” and “scared of judgment.”47 Semi-structured interviews of parents of 21 children with ASD in Australia revealed that parents found information on complementary and alternative medicine and therapies complex and often conflicting.45 In addition to recommendations from health care professionals, evidence suggests that parents often consider the opinions of media, friends, and family when making a decision on using complementary and alternative medicine modalities for children/adolescents with ASD.46 Such findings can inform physician practices regarding supplement use, and highlight the need to educate parents about the evidence regarding these therapies and potential adverse effects and interactions of such therapies,46 along with the need to develop a centralized, evidence-based resource for parents regarding their use.45

Omega 3 supplementation has in general shown few adverse effects47; still, risks/benefits need to be weighed before use. Some evidence suggests that it may decrease hyperactivity in children with ASD.31,48 However, further research, particularly controlled trials with large sample sizes, are needed for a definitive determination of efficacy.31,48 A meta-analysis that included 27 RCTs assessing the efficacy of dietary interventions for various ASD symptoms found that omega 3 supplementation was more effective than placebo, but compared with placebo, the effect size was small.49 A RCT of 73 children with ASD in New Zealand found that omega 3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids may benefit some core symptoms of ASD; the authors suggested that further research is needed to conclusively establish efficacy.50

Continue to: A need for advocacy and research..

A need for advocacy and research

Physicians who treat children with ASD can not only make appropriate referrals and educate parents, but also educate their patients’ schools and advocate for their patients to get the level of services they need.23,28

A recent study in the United States found that behavior therapy and speech-language therapy were used less often in the treatment of children with ASD in rural areas compared with those in metro areas.5 This suggests that in addition to increasing parents’ awareness and use of ASD services and providing referrals where appropriate, physicians are in a unique position to advocate for public health policies to improve access, coverage, and training for the provision of such services in rural areas.

There is need for ongoing research to further examine the efficacy and nuances of effects of various treatment interventions for ASD, especially long-term studies with larger sample sizes.11,51 Additionally, research is warranted to better understand the underlying genetic and neurobiological mechanisms of ASD, which would help guide the development of biomarkers,52 innovative treatments, and disease-modifying agents for ASD.7,22 Exploring the effects of potential alliances or joint action between biological and psychosocial interventions for ASD is also an area that needs further research.51

Bottom Line

A combination of treatment modalities (such as speech-language therapy, social skills training, behavior therapy/other psychotherapy, and occupational therapy for sensory sensitivities) is generally needed to improve the long-term outcomes of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In addition to the importance of early intervention, the intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments are vital to improving outcomes in ASD.

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Evidence supports the crucial role of early intervention and nonpharmacologic approaches

A large percentage of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience persisting significant social deficits in adulthood,1 which often leads to isolation, depressive symptoms, and poor occupational and relationship functioning.2,3 Childhood is a vital time for making the most significant and lasting changes that can improve functioning of individuals with ASD. Psychiatrists and other physicians who treat children are in a key role to influence outcomes of children at risk for or diagnosed with ASD.

This article provides updates on various aspects of ASD diagnosis and treatment (based on available evidence up to March 2020). Part 1 (

A comprehensive approach is essential

Multiple treatment modalities have been recommended for ASD.5 It is essential to address all aspects of ASD through cognitive, developmental, social-communication, sensory-motor, and behavioral interventions. Nonpharmacologic interventions are crucial in improving long-term outcomes of children with ASD.6

Nonpharmacologic treatments

Nonpharmacologic interventions commonly utilized for children with ASD include behavioral therapies, other psychological therapies, speech-language therapy, occupational therapy, educational interventions, parent coaching/training, developmental social interventions, and other modalities of therapy that are delivered in school, home, and clinic settings.5,7

A recent study examining ASD treatment trends via caregivers’ reports (N = 5,122) from the SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge) cohort in the United States reported that 80% of children received speech-language therapy or occupational therapy; 52% got both.5 The study revealed that approximately one-quarter utilized 3 therapies simultaneously; two-thirds had utilized 3 or more therapies in the previous year.5

Interventions for children with ASD need to be individualized.1,8 Evidence-based behavioral interventions for ASD fall into 2 broad categories: Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), and Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBI). Traditionally, ABA has been a key model, guiding treatment for enhancing social-communicating skills and lowering maladaptive behaviors in ASD.9 ABA follows a structured and prescribed format,10,11 and has been shown to be efficacious.1,7 More recently, NDBI, in which interventions are “embedded” in the natural environment of the young child and more actively incorporate a developmental perspective, has been shown to be beneficial in improving and generalizing social-communication skills in young children with ASD.7,11

Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is an intensive, naturalistic behavioral intervention4 that has been shown to be efficacious for enhancing communication and adaptive behavior in children with ASD.7,8,12 A multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Rogers et al12 that examined the efficacy of ESDM in 118 children (age 14 to 24 months) with ASD found the treatment was beneficial and superior compared with a “community intervention” group, in regards to language ability measured in time by group analyses.The ESDM intervention in this study involved weekly parent coaching for 3 months, along with 24 months of 15 hours/week of one-on-one treatment provided by therapy professionals.12

Reciprocal imitation training (RIT) is another naturalistic intervention that has shown benefit in training children with ASD in imitation skills during play.13 Studies have found that both RIT and ESDM can be parent-implemented, after parents receive training.13,14

Parent-mediated, parent-implemented interventions may have a role in improving outcomes in childhood ASD,7,15 particularly “better generalization and maintenance of skills than therapist-implemented intervention” for lowering challenging behaviors and enhancing verbal and nonverbal communication.16

Various social skills interventions have also been found effective for children with ASD.1 Such interventions are often provided in the school setting.7 Coordination with the child’s school to discuss and advocating for adequate and suitable interventions, educational services, and placement is an essential aspect of ASD treatment.7

Two other school-based, comprehensive treatment model interventions—Learning Experiences and Alternative Programs for Preschoolers and their Parents (LEAP), and TEACCH—have some evidence of leading to improvement in children with ASD.7,17

Some studies have found that music therapy may have high efficacy for children with ASD, even with smaller length and intensity of treatment, particularly in improving social interaction, engagement with parents, joint attention, and communication.3,18 Further research is needed to conclusively establish the efficacy of music therapy for ASD in children and adolescents.

A few studies have assessed the long-term outcomes of interventions for ASD; however, more research is needed.19 Pickles et al19 conducted a follow-up to determine the long-term effects of the Preschool Autism Communication Trial (PACT), an RCT of parent-mediated social communication therapy for children age 2 to 4 with ASD. The children’s average age at follow-up was 10 years. The authors found a significant long-term decrease in ASD symptoms and enhancement of social communication with parents (N = 152).

Technology-based interventions, including games and robotics, have been investigated in recent years, for treatment of children with ASD (eg, for improving social skills).20

Research suggests that the intensity (number of hours) and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments for ASD is critical to improving outcomes (Box1,3,5,7,10,16).

Box

A higher intensity of nonpharmacologic intervention (greater number of hours) has been associated with greater benefit for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), in the form of enhancements in IQ and adaptive behavior.1,10,16 In the United States, the intensity of interventions commonly ranges from 30 to 200 or more minutes per week.3 This may mean that a child with ASD who is receiving 30 minutes of speech therapy at school and continues to exhibit significant deficits in speech-language or social-communication may likely benefit from additional hours of speech therapy and/or social-communication skill training, and should be referred accordingly, even for private therapy services if needed and feasible.7 Guidelines created through a systematic review of evidence recommend at least 25 hours per week of comprehensive treatment interventions for children with ASD to address language, social deficits, and behavioral difficulties.1 The duration of intervention has also been shown to play a role in outcomes.1,3,10 Given the complexity and extent of impairment often associated with ASD, it is not surprising that in recent research examining trends in ASD treatment in the United States, most caregivers reported therapy as ongoing.5 The exact intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic interventions may depend on several factors, such as severity of ASD and of the specific deficit being targeted, type of intervention, and therapist skill. The quality of skills of the care provider has also been shown to affect the benefits gained from the intervention.3

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy...

Pharmacotherapy

Medications cannot resolve core features of ASD.21 However, certain medications may help address associated comorbidities, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, or others, when these conditions have not responded to nonpharmacologic interventions.7,22 Common symptoms that are often treated with pharmacotherapy include aggression, irritability, hyperactivity, attentional difficulties, tics, self-injurious behavior, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and mood dysregulation/lability.23 Generally speaking, medications might be considered if symptoms are severe and markedly impair functioning. For mild to moderate conditions, psychotherapy and other nonpharmacologic interventions are generally considered first-line. Since none of the medications described below are specific to ASD and psychiatrists generally receive training in prescribing them for other indications, a comprehensive review of their risks and benefits is beyond the scope of this article. No psychotropic medications are known to have robust evidence for safety in preschool children with ASD, and thus are best avoided.

Antipsychotics. Risperidone (for age 5 and older) and aripiprazole (age 6 to 17) are the only medications FDA-approved for use in children and adolescents with ASD, specifically for irritability associated with ASD.21,24 These 2 second-generation antipsychotics may also assist in lowering aggression in patients with ASD.24 First-generation antipsychotics such as haloperidol have been shown to be effective for irritability and aggression in ASD, but the risk of significant adverse effects such as dyskinesias and extrapyramidal symptoms limit their use.24 Two studies (a double-blind study and an open-label extension of that study) in children and adolescents with ASD found that risperidone was more effective and better tolerated than haloperidol in behavioral measures, impulsivity, and even in the social domain.25,26 In addition to other adverse effects and risks, increased prolactin secondary to risperidone use requires close monitoring and caution.24-26 As is the case with the use of other psychotropic medications in children and adolescents, those with ASD who receive antipsychotics should also be periodically reassessed to determine the need for continued use of these medications.27 A multicenter relapse prevention RCT found no statistically significant difference in the time to relapse between aripiprazole and placebo.27 Metabolic syndrome, cardiac risks, and other risks need to be considered before prescribing an antipsychotic.28 Given their serious adverse effects profile, use should be considered only when there is severe impairment or risk of injury, after carefully weighing risks/benefits.

Medications for attentional difficulties. A multisite, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the use of extended-release guanfacine in children with ASD (N = 62) found the rate of positive response on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale was 50% for guanfacine vs 9.4% for placebo.29 Clinicians need to monitor for adverse effects of guanfacine, such as fatigue, drowsiness, lightheadedness, lowering of blood pressure and heart rate, and other effects.29 A randomized, double-blind trial of 97 children and adolescents with ASD and ADHD found that atomoxetine had moderate benefit for ADHD symptoms.30 The study reported no serious adverse effects.30 However, it is especially important to monitor for hepatic and cardiac adverse effects (in addition to monitoring for risk of increase in suicidal thoughts/behavior, as in the case of antidepressants) when using atomoxetine, in addition to other side effects and risks. Some evidence suggests that methylphenidate may be effective for attentional difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD21 but may pose a higher risk of adverse effects in this population compared with neurotypical patients.31

Antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are sometimes used to reduce obsessive-compulsive symptoms, repetitive behavior, or depressive symptoms in children with ASD, but are not FDA-approved for children or adolescents with ASD. In general, there is inadequate evidence to support the use of SSRIs for ASD in children.31-34 In addition, children with ASD may be at a greater risk of adverse effects from SSRIs.32,34 Despite this, SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications in children with ASD.32

An RCT examining the efficacy of fluoxetine in 158 children and adolescents with ASD found no significant difference in Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) score after 14 weeks of treatment; activation was a common adverse effect.35 A 2005 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 45 children/adolescents with ASD found that low-dose liquid fluoxetine was more effective than placebo for reducing repetitive behaviors in this population.36 Larger studies are warranted to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of fluoxetine (and of SSRIs in general, particularly in the long term) for children and adolescents with ASD.36 A 2009 randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 149 children with ASD revealed no significant difference between citalopram and placebo as measured by Clinical Global Impressions scale or CY-BOCS scores, and noted a significantly elevated likelihood of adverse effects.37

Other antidepressants. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of any other antidepressants in children and adolescents with ASD. A few studies38,39 have examined the use of venlafaxine in children with ASD; however, further research and controlled studies with large sample sizes are required to conclusively establish its benefits. There is a dearth of evidence examining the use of the tetracyclic antidepressant mirtazapine, or other classes of medications such as tricyclic antidepressants or mood stabilizers, in children with ASD; only a few small studies have assessed the efficacy and adverse effects of these medications for such patients.31

Polypharmacy. Although there is no evidence to support polypharmacy in children and adolescents with ASD, the practice appears to be rampant in these patients.28,40 A 2013 retrospective, observational study of psychotropic medication use in children with ASD (N = 33,565) found that 64% were prescribed psychotropic medications, and 35% exhibited evidence of polypharmacy.40 In this study, the total duration of polypharmacy averaged 525 days.40 When addressing polypharmacy, systematic deprescribing or simplification of the psychotropic medication regimen may be needed,28 while taking into account the patient’s complete clinical situation, including (but not limited to) tolerability of the medication regimen, presence or absence of current stressors, presence or absence of adequate supports, use of nonpharmacologic treatments where appropriate, and other factors.

More studies assessing the efficacy and safety of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents with ASD are needed,32 especially studies that evaluate the effects of long-term use, because evidence for pharmacologic treatments for children with ASD is mixed and insufficient.33 There is also a need for evidence-based standards for prescribing psychotropic medications in children and adolescents with ASD.

Psychotropic medications, if used in ASD, should be used only in conjunction with other evidence-based treatment modalities, and not as monotherapy.21 Children and adolescents with ASD may be particularly susceptible to side effects or adverse effects of certain psychotropic medications.31 When considering medications, carefully weigh the risks and benefits.7,21,24,28 Starting low and going slow is generally the preferred strategy.31,32 As always, when recommending medications, discuss in detail with parents the potential side effects, benefits, risks, interactions, and alternatives.

Other agents. Several double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have evaluated using melatonin for sleep difficulties in children and adolescents with ASD.41 A randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trial that assessed 160 children with ASD and insomnia found that melatonin plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was superior in efficacy to melatonin alone, CBT alone, or placebo.41

The evidence regarding oxytocin use for children with ASD is mixed.31 Some small studies have associated improvement in the social domain with its use. Guastella et al42 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oxytocin nasal spray for 16 participants (age 12 to 19) with ASD, and found oxytocin enhanced emotional identification. Gordon et al43 conducted a functional MRI study of brain activity with oxytocin use in children with high-functioning ASD (N = 17). They found that oxytocin may augment “salience and hedonic evaluations of socially meaningful stimuli in children with ASD” and thus help social attunement. Further research is needed to evaluate the impact of oxytocin on social behavior.

Complementary and alternative medicine. Although there is limited and inconclusive evidence about the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with ASD, these therapies continue to be commonly used.44-46 A recent survey of parents (N = 211) of children with ASD from academic ASD outpatient clinics in Germany found that 46% reported their child was using or had used some type of complementary and alternative medicine.44 There is inadequate evidence to support the use of a gluten-free, casein-free diet for children/adolescents with ASD.46 A recent cross-sectional study assessing supplement use in 210 children with ASD in Canada found that 75% used supplements, such as multivitamins (77.8%), vitamin D (44.9%), omega 3 (42.5%), probiotics (36.5%), and magnesium (28.1%), despite insufficient evidence to support their safety or efficacy for children with ASD.47 Importantly, 33.5% of parents in this study reported that they did not inform the physician about all their child’s supplements.47 Some of the reasons the parents in this study provided for not disclosing information about supplements to their physicians were “physician lack of knowledge,” “no benefit,” “too time-consuming,” and “scared of judgment.”47 Semi-structured interviews of parents of 21 children with ASD in Australia revealed that parents found information on complementary and alternative medicine and therapies complex and often conflicting.45 In addition to recommendations from health care professionals, evidence suggests that parents often consider the opinions of media, friends, and family when making a decision on using complementary and alternative medicine modalities for children/adolescents with ASD.46 Such findings can inform physician practices regarding supplement use, and highlight the need to educate parents about the evidence regarding these therapies and potential adverse effects and interactions of such therapies,46 along with the need to develop a centralized, evidence-based resource for parents regarding their use.45

Omega 3 supplementation has in general shown few adverse effects47; still, risks/benefits need to be weighed before use. Some evidence suggests that it may decrease hyperactivity in children with ASD.31,48 However, further research, particularly controlled trials with large sample sizes, are needed for a definitive determination of efficacy.31,48 A meta-analysis that included 27 RCTs assessing the efficacy of dietary interventions for various ASD symptoms found that omega 3 supplementation was more effective than placebo, but compared with placebo, the effect size was small.49 A RCT of 73 children with ASD in New Zealand found that omega 3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids may benefit some core symptoms of ASD; the authors suggested that further research is needed to conclusively establish efficacy.50

Continue to: A need for advocacy and research..

A need for advocacy and research

Physicians who treat children with ASD can not only make appropriate referrals and educate parents, but also educate their patients’ schools and advocate for their patients to get the level of services they need.23,28

A recent study in the United States found that behavior therapy and speech-language therapy were used less often in the treatment of children with ASD in rural areas compared with those in metro areas.5 This suggests that in addition to increasing parents’ awareness and use of ASD services and providing referrals where appropriate, physicians are in a unique position to advocate for public health policies to improve access, coverage, and training for the provision of such services in rural areas.

There is need for ongoing research to further examine the efficacy and nuances of effects of various treatment interventions for ASD, especially long-term studies with larger sample sizes.11,51 Additionally, research is warranted to better understand the underlying genetic and neurobiological mechanisms of ASD, which would help guide the development of biomarkers,52 innovative treatments, and disease-modifying agents for ASD.7,22 Exploring the effects of potential alliances or joint action between biological and psychosocial interventions for ASD is also an area that needs further research.51

Bottom Line

A combination of treatment modalities (such as speech-language therapy, social skills training, behavior therapy/other psychotherapy, and occupational therapy for sensory sensitivities) is generally needed to improve the long-term outcomes of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In addition to the importance of early intervention, the intensity and duration of nonpharmacologic treatments are vital to improving outcomes in ASD.

1. Maglione MA, Gans D, Das L, et al. Nonmedical interventions for children with ASD: recommended guidelines and further research needs. Pediatrics. 2012;30(Suppl 2):S169-S178.

2. Simms MD, Jin XM. Autism, language disorder, and social (pragmatic) communication disorder: DSM-V and differential diagnoses. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(8):355-363. doi:10.1542/pir.36-8-355

3. Su Maw S, Haga C. Effectiveness of cognitive, developmental, and behavioural interventions for autism spectrum disorder in preschool-aged children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2018;4(9):e00763. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00763

4. Charman T. Editorial: trials and tribulations in early autism intervention research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(9):846-848. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.03.004

5. Monz BU, Houghton R, Law K, et al. Treatment patterns in children with autism in the United States. Autism Res. 2019;12(3):517-526. doi:10.1002/aur.2070

6. Sperdin HF, Schaer M. Aberrant development of speech processing in young children with autism: new insights from neuroimaging biomarkers. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:393. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00393

7. Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM, et al. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193447. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3447

8. Contaldo A, Colombi C, Pierotti C, et al. Outcomes and moderators of Early Start Denver Model intervention in young children with autism spectrum disorder delivered in a mixed individual and group setting. Autism. 2020;24(3):718-729. doi:10.1177/1362361319888344

9. Lei J, Ventola P. Pivotal response treatment for autism spectrum disorder: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1613-1626. doi:10.2147/NDT.S120710

10. Landa RJ. Efficacy of early interventions for infants and young children with, and at risk for, autism spectrum disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(1):25-39. doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1432574

11. Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2411-2428. doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8

12. Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, et al. A multisite randomized controlled two-phase trial of the Early Start Denver Model compared to treatment as usual. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(9):853-865. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.01.004

13. Ingersoll B, Gergans S. The effect of a parent-implemented imitation intervention on spontaneous imitation skills in young children with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2007;28(2):163-175.

14. Waddington H, van der Meer L, Sigafoos J, et al. Examining parent use of specific intervention techniques during a 12-week training program based on the Early Start Denver Model. Autism. 2020;24(2):484-498. doi:10.1177/1362361319876495

15. Trembath D, Gurm M, Scheerer NE, et al. Systematic review of factors that may influence the outcomes and generalizability of parent‐mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2019;12(9):1304-1321.

16. Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, et al. Effects of a brief Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1052-1065. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003

17. Boyd BA, Hume K, McBee MT, et al. Comparative efficacy of LEAP, TEACCH and non-model-specific special education programs for preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(2):366-380. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1877-9

18. Thompson GA, McFerran KS, Gold C. Family-centred music therapy to promote social engagement in young children with severe autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(6):840-852. doi:10.1111/cch.12121