User login

FDA okays first sublingual med for agitation in serious mental illness

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first FDA-approved, orally dissolving, self-administered sublingual treatment for this indication. With a demonstrated onset of action as early as 20 minutes, it shows a high response rate in patients at both 120-mcg and 180-mcg doses.

An estimated 7.3 million individuals in the United States are diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, and up to one-quarter of them experience episodes of agitation that can occur 10-17 times annually. These episodes represent a significant burden for patients, caregivers, and the health care system.

“There are large numbers of patients who experience agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, and this condition has been a long-standing challenge for health care professionals to treat,” said John Krystal, MD, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research and chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“The approval of Igalmi, a self-administered film with a desirable onset of action, represents a milestone moment. It provides health care teams with an innovative tool to help control agitation. As clinicians, we welcome this much-needed new oral treatment option,” he added.

“Igalmi is the first new acute treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder–associated agitation in nearly a decade and represents a differentiated approach to helping patients manage this difficult and debilitating symptom,” said Vimal Mehta, PhD, CEO of BioXcel Therapeutics.

The FDA approval of Igalmi is based on data from two pivotal randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 trials that evaluated Igalmi for the acute treatment of agitation associated with schizophrenia (SERENITY I) or bipolar I or II disorder (SERENITY II).

The most common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were somnolence, paresthesia or oral hypoesthesia, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension, and orthostatic hypotension. All adverse drug reactions were mild to moderate in severity. While Igalmi was not associated with any treatment-related serious adverse effects in phase 3 studies, it may cause notable side effects, including hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, QT interval prolongation, and somnolence.

As previously reported by this news organization, data from the phase 3 SERENITY II trial that evaluated Igalmi in bipolar disorders were published in JAMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study: Physical fitness in children linked with concentration, quality of life

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MEDICINE

Exercise to Reduce Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Veterans

Physical exercise offers preventative and therapeutic benefits for a range of chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer disease, and depression.1,2 Exercise has been well studied for its antidepressant effects, its ability to reduce risk of aging-related dementia, and favorable effects on a range of cognitive functions.2 Lesser evidence exists regarding the impact of exercise on other mental health concerns. Therefore, an accurate understanding of whether physical exercise may ameliorate other conditions is important.

A small meta-analysis by Rosenbaum and colleagues found that exercise interventions were superior to control conditions for symptom reduction in study participants with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 This meta-analysis included 4 randomized clinical trials representing 200 cases. The trial included a variety of physical activities (eg, yoga, aerobic, and strength-building exercises) and control conditions, and participants recruited from online, community, inpatient, and outpatient settings. The standardized mean difference (SMD) produced by the analysis indicated a small-to-medium effect (Hedges g, -0.35), with the authors reporting no evidence of publication bias, although an assessment of potential bias associated with individual trial design characteristics was not conducted. Of note, a meta-analysis by Watts and colleagues found that effect sizes for PTSD treatments tend to be smaller in veteran populations.4 Therefore, how much the mean effect size estimate in the study is applicable to veterans with PTSD is unknown.3

Veterans represent a unique subpopulation in which PTSD is common, although no meta-analysis yet published has synthesized the effects of exercise interventions from trials of veterans with PTSD.5 A recent systematic review by Whitworth and Ciccolo concluded that exercise may be associated with reduced risk of PTSD, a briefer course of PTSD symptoms, and/or reduced sleep- and depression-related difficulties.6 However, that review primarily included observational, cross-sectional, and qualitative works. No trials included in our meta-analysis were included in that review.6

Evidence-based psychotherapies like cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure have been shown to be effective for treating PTSD in veterans; however, these modalities are accompanied by high rates of dropout (eg, 40-60%), thereby limiting their clinical utility.7 The use of complementary and alternative approaches for treatment in the United States has increased in recent years, and exercise represents an important complementary treatment option.8 In a study by Baldwin and colleagues, nearly 50% of veterans reported using complementary or alternative approaches, and veterans with PTSD were among those likely to use such approaches.9 However, current studies of the effects of exercise interventions on PTSD symptom reduction are mostly small and varied, making determinations difficult regarding the potential utility of exercise for treating this condition in veterans.

Literature Search

No previous research has synthesized the literature on the effects of exercise on PTSD in the veteran population. The current meta-analysis aims to provide a synthesis of systematically selected studies on this topic to determine whether exercise-based interventions are effective at reducing veterans’ symptoms of PTSD. Our hypothesis was that, when used as a primary or adjuvant intervention for PTSD, physical exercise would be associated with a reduction of PTSD symptom scale scores. We planned a priori to produce separate estimates for single-arm and multi-arm trials. We also wanted to conduct a careful risk of bias assessment—or evaluation of study features that may have systematically influenced results—for included trials, not only to provide context for interpretation of results, but also to inform suggestions for research to advance this field of inquiry.10

Methods

This study was preregistered on PROSPERO and followed PRISMA guidelines for meta-analyses and systematic reviews.11 Supplementary materials, such as the PRISMA checklist, study data, and funnel plots, are available online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1). Conference abstracts were omitted due to a lack of necessary information. We decided early in the planning process to include both randomized and single-arm trials, expecting the number of completed studies in the area of exercise for PTSD symptom reduction in veterans, and particularly randomized trials of such, would be relatively small.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study was a single- or multi-arm interventional trial; (2) participants were veterans; (3) participants had a current diagnosis of PTSD or exhibited subthreshold PTSD symptoms, as established by authors of the individual studies and supported by a structured clinical interview, semistructured interview, or elevated scores on PTSD symptom self-report measures; (4) the study included an intervention in which exercise (physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive in the sense that improvement or maintenance of physical fitness or health is an objective) was the primary component; (5) PTSD symptom severity was by a clinician-rated or self-report measure; and (6) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal.12 Studies were excluded if means, standard deviations, and sample sizes were not available or the full text of the study was not available in English.

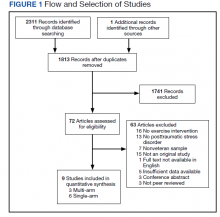

The systematic review was conducted using PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases, from the earliest record to February 2021. The following search phrase was used, without additional limits, to acquire a list of potential studies: (“PTSD” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “posttraumatic stress disorder” or “post traumatic stress disorder”) and (“veteran” or “veterans”) and (“exercise” or “aerobic” or “activity” or “physical activity”). The references of identified publications also were searched for additional studies. Then, study titles and abstracts were evaluated and finally, full texts were evaluated to determine study inclusion. All screening, study selection, and risk of bias and data extraction activities were performed by 2 independent reviewers (DR and MJ) with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus (Figure 1). A list of studies excluded during full-text review and rationales can be viewed online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1).

Data Collection

Data were extracted from included studies using custom forms and included the following information based on PRISMA guidelines: (1) study design characteristics; (2) intervention details; and (3) PTSD outcome information.11 PTSD symptom severity was the primary outcome of interest. Outcome data were included if they were derived from a measure of PTSD symptoms—equivalency across measures was assumed for meta-analyses. Potential study bias for each outcome was evaluated using the ROBINS-I and Cochrane Collaboration’s RoB 2 tools for single-arm and multi-arm trials, respectively.13,14 These tools evaluate domains related to the design, conduct, and analysis of studies that are associated with bias (ie, systematic error in findings, such as under- or overestimation of results).10 Examples include how well authors performed and concealed randomization procedures, addressed missing data, and measured study outcomes.13,14 The risk of bias (eg, low, moderate, serious) associated with each domain is rated and, based on the domain ratings, each study is then given an overall rating regarding how much risk influences bias.13,14 Broadly, lower risk of bias corresponds to higher confidence in the validity of results.

Finally, 4 authors (associated with 2 single- and 2 multi-arm studies) were contacted and asked to provide further information. Data for 1 additional multi-arm study were obtained from these communications and included in the final study selection.15 These authors were also asked for information about any unpublished works of which they were aware, although no additional works were identified.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed with R Studio R 3.6.0 software.16 An SMD (also known as Hedges g) was calculated for each study outcome: for single-arm trials, this was the SMD between pre- and postintervention scores, whereas for multi-arm trials, this was the SMD between postintervention outcome scores across groups. CIs for each SMD were calculated using a standard normal distribution. Combined SMDs were estimated separately for single- and multi-arm studies, using random-effects meta-analyses. In order to include multiple relevant outcomes from a single trial (ie, for studies using multiple PTSD symptom measures), robust variance estimation was used.17 Precision was used to weight SMDs.

Correlations between pre- and postintervention scores were not available for 1 single-arm study.18 A correlation coefficient of 0.8 was imputed to calculate the standard error of the of the SMDs for the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the PTSD Checklist (PCL), as this value is consistent with past findings regarding the test-retest reliability of these measures.19-22 A sensitivity analysis, using several alternative correlational values, revealed that the choice of correlation coefficient did not impact the overall results of the meta-analysis.

I2 was used to evaluate between-study heterogeneity. Values of I2 > 25%, 50%, and 75% were selected to reflect low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively, in accordance with guidelines described by Higgins and colleagues.23 Potential publication bias was assessed via funnel plot and Egger test.24 Finally, although collection of depressive symptom scores was proposed as a secondary outcome in the study protocol, such data were available only for 1 multi-arm study. As a result, this outcome was not evaluated.

Results

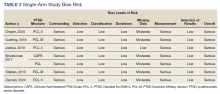

Six studies with 101 total participants were included in the single-arm analyses (Table 1).18,25-29 Participants consisted of veterans with chronic pain, post-9/11 veterans, female veterans of childbearing age, veterans with a history of trauma therapy, and other veterans. Types of exercise included moderate aerobic exercise and yoga. PTSD symptom measures included the CAPS and the PCL (PCL-5 or PCL-M versions). Reported financial sources for included studies included federal grant funding, nonprofit material support, outside organization support, use of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) resources, and no reported financial support.

With respect to individual studies, Shivakumar and colleagues found that completion of an aerobic exercise program was associated with reduced scores on 2 different PTSD symptom scales (PCL and CAPS) in 16 women veterans.18 A trauma-informed yoga intervention study with 18 participants by Cushing and colleagues demonstrated veteran participation to be associated with large reductions in PTSD, anxiety, and depression scale scores.25 In a study with 34 veterans, Chopin and colleagues found that a trauma-informed yoga intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, as did a study by Zaccari and colleagues with 17 veterans.26,29 Justice and Brems also found some evidence that trauma-informed yoga interventions helped PTSD symptoms in a small sample of 4 veterans, although these results were not quantitatively analyzed.27 In contrast, a small pilot study (n = 12) by Staples and colleagues testing a biweekly, 6-week yoga program did not show a significant effect on PTSD symptoms.28

Three studies with 217 total veteran participants were included in the multi-arm analyses (Table 2).15,30,31 As all multi-arm trials incorporated randomization, they will be referred to as randomized controlled trials (RCTs). On contact, Davis and colleagues provided veteran-specific results for their trial; as such, our data differ from those within the published article.15 Participants from all included studies were veterans currently experiencing symptoms of PTSD. Types of exercise included yoga and combined methods (eg, aerobic and strength training).15,30,31 PTSD symptom measures included the CAPS or the PCL-5.15,30,31 Reported financial sources for included studies included federal grant funding, as well as nonprofit support, private donations, and VA and Department of Defense resources.

Davis and colleagues conducted a recently concluded RCT with > 130 veteran participants and found that a novel manualized yoga program was superior to an attention control in reducing PTSD symptom scale scores for veterans.15 Goldstein and colleagues found that a program consisting of both aerobic and resistance exercises reduced PTSD symptoms to a greater extent than a waitlist control condition, with 47 veterans randomized in this trial.30 Likewise, Hall and colleagues conducted a pilot RCT in which an intervention that integrated exercise and cognitive behavioral techniques was compared to a waitlist control condition.31 For the 48 veterans included in the analyses, the authors reported greater PTSD symptom reduction associated with integrated exercise than that of the control condition; however, the study was not powered to detect statistically significant differences between groups.

Bias Assessment

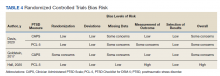

Results for the risk of bias assessments can be viewed in Tables 3 and 4. For single-arm studies, overall risk of bias was serious for all included trials. Serious risk of bias was found in 2 domains: confounding, due to a lack of accounting for potential preexisting baseline trends (eg, regression to the mean) that could have impacted study results; and measurement, due to the use of a self-report symptom measure (PCL) or CAPS with unblinded assessors. Multiple studies also showed moderate risk in the missing data domain due to participant dropout without appropriate analytic methods to address potential bias.

For RCTs, overall risk of bias ranged from some concerns to high risk. High risk of bias was found in 1 domain, measurement of outcome, due to use of a self-report symptom measure (PCL) with unblinded groups.31 The other 2 studies all had some concern of bias in at least 1 of the following domains: randomization, missing data, and measurement of outcome.

Pooled Standardized Mean Differences

Meta-analytic results can be viewed in Figure 2. The pooled SMD for the 6 single-arm studies was -0.60 (df = 4.41, 95% CI, -1.08 to -0.12, P = .03), indicating a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms over the course of an exercise intervention. Combining SMDs for the 3 included RCTs revealed a pooled SMD of -0.40 (df = 1.57, 95% CI, -0.86 to 0.06, P = .06), indicating that exercise did not result in a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms compared with control conditions.

Publication Bias and Heterogeneity

Visual inspection funnel plots and Egger test did not suggest the presence of publication bias for RCTs (t = 1.21, df = 2, P = .35) or single-arm studies (t = -0.36, df = 5, P = .73).

Single-arm studies displayed a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 81.5%). Including sample size or exercise duration as variables in meta-regressions did not reduce heterogeneity (I2 = 85.2% and I2 = 83.8%, respectively). Performing a subgroup analysis only on studies using yoga as an intervention also did not reduce heterogeneity (I2 = 79.2%). Due to the small number of studies, no further exploration of heterogeneity was conducted on single-arm studies. RCTs did not display any heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Discussion

Our report represents an early synthesis of the first prospective studies of physical exercise interventions for PTSD in veterans. Results from meta-analyses of 6 single-arm studies (101 participants) and 3 RCTs (217 participants) provide early evidence that exercise may reduce PTSD symptoms in veterans. Yoga was the most common form of exercise used in single-arm studies, whereas RCTs used a wider range of interventions. The pooled SMD of -0.60 for single-arm longitudinal studies suggest a medium decrease in PTSD symptoms for veterans who engage in exercise interventions. Analysis of the RCTs supported this finding, with a pooled SMD of -0.40 reflecting a small-to-medium effect of exercise on PTSD symptoms over control conditions, although this result did not achieve statistical significance. Of note, while the nonsignificant finding for RCTs may have been due to insufficient power caused by the limited number of included studies, possibly exercise was not more efficacious than were the control conditions.

Although RCTs represented a variety of exercise types, PTSD symptom measures, and veteran subgroups, statistical results were not indicative of heterogeneity. However, only the largest and most comprehensive study of exercise for PTSD in veterans to date by Davis and colleagues had a statistically significant SMD.15 Of note, one of the other 2 RCTs displayed an SMD of a similar magnitude, but this study had a much smaller sample size and was underpowered to detect significance.30 Additionally, risk of bias assessments for single-arm studies and RCTs revealed study characteristics that suggest possible inflation of absolute effect sizes for individual studies. Therefore, the pooled SMDs we report are interpretable but may exceed the true effect of exercise for PTSD symptom reduction in veterans.

Based on results of our analyses, it is reasonable, albeit preliminary, to conclude that exercise interventions may result in reduced PTSD symptoms among veterans. At the very least, these findings support the continued investigation of such interventions for veterans. Given the unique and salubrious characteristics of physical exercise, such results, if supported by further research, suggest that exercise-based interventions may be particularly valuable within the trauma treatment realm. For example, exercise can be less expensive and more convenient than attending traditional treatment, and for veterans reluctant to engage in standard treatment approaches such as psychiatric and psychosocial modalities, complementary approaches entailing exercise may be viewed as particularly acceptable or enjoyable.32 In addition to possibly reducing PTSD symptoms, exercise is a well-established treatment for conditions commonly comorbid with PTSD, including depression, anxiety disorders, cognitive difficulties, and certain chronic pain conditions.6 As such, exercise represents a holistic treatment option that has the potential to augment standard PTSD care.

Limitations

The present study has several important limitations. First, few studies were found that met the broad eligibility criteria and those that did often had a small sample size. Besides highlighting a gap in the extant research, the limited studies available for meta-analysis means that caution must be taken when interpreting results. Fortunately, this issue will likely resolve once additional studies investigating the impact of exercise on PTSD symptoms in veterans are available for synthesis.

Relatedly, the included study interventions varied considerably, both in the types of exercise used and the characteristics of the exercises (eg, frequency, duration, and intensity), which is relevant as different exercise modalities are associated with differential physical effects.33 Including such a mixture of exercises may have given an incomplete picture of their potential therapeutic effects. Also, none of the RCTs compared exercise against first-line treatments for PTSD, such as prolonged exposure or cognitive processing therapy, which would have provided further insight into the role exercise could play in clinical settings.7

Another limitation is the elevated risk of bias found in most studies, particularly present in the longitudinal single-arm studies, all of which were rated at serious risk. For instance, no single-arm study controlled for preexisting baseline trends: without such (and lacking a comparison control group like in RCTs), it is possible that the observed effects were due to extraneous factors, rather than the exercise intervention. Although not as severe, the multi-arm RCTs also displayed at least moderate risk of bias. Therefore, SMDs may have been overestimated for each group of studies.

Finally, the results of the single-arm meta-analysis displayed high statistical heterogeneity, reducing the generalizability of the results. One possible cause of this heterogeneity may have been the yoga interventions, as a separate analysis removing the only nonyoga study did not reduce heterogeneity. This result was surprising, as the included yoga interventions seemed similar across studies. While the presence of high heterogeneity does require some caution when applying these results to outside interventions, the present study made use of random-effects meta-analysis, a technique that incorporates study heterogeneity into the statistical model, thereby strengthening the findings compared with that of a traditional fixed-effects approach.10

Future Steps

Several future steps are warranted to improve knowledge of exercise as a treatment for PTSD in veterans and in the general population. With current meta-analyses limited to small numbers of studies, additional studies of the efficacy of exercise for treating PTSD could help in several ways. A larger pool of studies would enable future meta-analyses to explore related questions, such as those regarding the impact of exercise on quality of life or depressive symptom reduction among veterans with PTSD. A greater number of studies also would enable meta-analysts to explore potentially critical moderators. For example, the duration, frequency, or type of exercise may moderate the effect of exercise on PTSD symptom reduction. Moderators related to patient or study design characteristics also should be explored in future studies.

Future work also should evaluate the impact that specific features of exercise regimens have on PTSD. Knowing whether the type or structure of exercise affects its clinical use would be invaluable in developing and implementing efficient exercise-based interventions. For example, if facilitated exercise was found to be significantly more effective at reducing PTSD symptoms than exercise completed independently, the development of exercise intervention programs in the VA and other facilities that commonly treat PTSD may be warranted. Additionally, it may be useful to identify specific mechanisms through which exercise reduces PTSD symptoms. For example, in addition to its beneficial biological effects, exercise also promotes psychological health through behavioral activation and alterations within reinforcement/reward systems, suggesting that exercise regularity may be more important than intensity.34,35 Understanding which mechanisms contribute most to change will aid in the development of more efficient interventions.

Given that veterans are demonstrating considerable interest in complementary and alternative PTSD treatments, it is critical that researchers focus on high-quality randomized tests of these interventions. Therefore, in addition to greater quality of exercise intervention studies, future efforts should be focused on RCTs that are designed in such a way as to limit potential introduction of bias. For example, assessment data should be completed by blinded assessors using standardized measures, and analyses should account for missing data and unequal participant attrition between groups. Ideally, pre-intervention trends across multiple baseline datapoints also would be collected in single-arm studies to avoid confounding related to regression to the mean. It is also recommended that future meta-analyses use risk of bias assessments and consider how the results of such assessments may impact the interpretation of results.

Conclusions

Findings from both single-arm studies and RCTs suggest possible benefit of exercise on PTSD symptom reduction, although confirmation of findings is needed. No study found increased symptoms following exercise intervention. Thus, it is reasonable to consider physical exercise, such as yoga, as an adjunct, whole-health consistent treatment. HCPs working with veterans with past traumatic experiences should consider incorporating exercise into patient care. Enhanced educational efforts emphasizing the psychotherapeutic impact of exercise may also have value for the veteran population. Furthermore, the current risk of bias assessments highlights the need for additional high-quality RCTs evaluating the specific impact of exercise on PTSD symptom reduction in veterans. In particular, this field of inquiry would benefit from larger samples and design characteristics to reduce bias (eg, blinding when possible, use of CAPS vs only self-report symptom measures, reducing problematic attrition, corrections for missing data, etc).

Acknowledgments

This research is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Eastern Kansas Healthcare System (Dwight D. Eisenhower VA Medical Center). It was also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, as well as the Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Since Dr. Reis and Dr. Gaddy are employees of the US Government and contributed to this manuscript as part of their official duties, the work is not subject to US copyright. This study was preregistered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/; ID: CRD42020153419).

1. Reiner M, Niermann C, Jekauc D, Woll A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:813. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-813

2. Walsh R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):579-592. doi:10.1037/a0021769

3. Rosenbaum S, Vancampfort D, Steel Z, Newby J, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Physical activity in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):130-136. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017

4. Watts BV, Schnurr PP, Mayo L, Young-Xu Y, Weeks WB, Friedman MJ. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):e541-550. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08225

5. Tanielian T, Jaycox L, eds. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. RAND Corporation; 2008

6. Whitworth JW, Ciccolo JT. Exercise and post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans: a systematic review. Mil Med. 2016;181(9):953-960. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00488

7. Rutt BT, Oehlert ME, Krieshok TS, Lichtenberg JW. Effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Psychol Rep. 2018;121(2):282-302. doi:10.1177/0033294117727746

8. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015(79):1-16.

9. Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: Implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1697-1704. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.15.1697

10. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chanlder J, et al, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane; 2021.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

12. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126-131.

13. Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

14. Sterne JAC, Savovic´ J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898

15. Davis LW, Schmid AA, Daggy JK, et al. Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with veterans and civilians. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):904-912. doi:10.1037/tra0000564

16. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019.

17. Tipton E. Small sample adjustments for robust variance estimation with meta-regression. Psychol Methods .2015;20(3):375-393. doi:10.1037/met0000011

18. Shivakumar G, Anderson EH, Surís AM, North CS. Exercise for PTSD in women veterans: a proof-of-concept study. Mil Med. 2017;182(11):e1809-e1814. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00440

19. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75-90. doi:10.1007/BF02105408

20. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669-673. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2

21. Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, et al. The Clinician- Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS- 5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol Assess. 2018;30(3):383-395.doi:10.1037/pas0000486

22. Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(7):596-606. doi:10.1002/da.20837

23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

24. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

25. Cushing RE, Braun KL, Alden CISW, Katz AR. Military- tailored yoga for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2018;183(5-6):e223-e231. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx071

26. Chopin SM, Sheerin CM, Meyer BL. Yoga for warriors: An intervention for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):888-896. doi:10.1037/tra0000649

27. Justice L, Brems C. Bridging body and mind: case series of a 10-week trauma-informed yoga protocol for veterans. Int J Yoga Therap. 2019;29(1):65-79. doi:10.17761/D-17-2019-00029

28. Staples JK, Hamilton MF, Uddo M. A yoga program for the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. Mil Med. 2013;178(8):854-860. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00536

29. Zaccari B, Callahan ML, Storzbach D, McFarlane N, Hudson R, Loftis JM. Yoga for veterans with PTSD: Cognitive functioning, mental health, and salivary cortisol. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):913-917. doi:10.1037/tra0000909

30. Goldstein LA, Mehling WE, Metzler TJ, et al. Veterans Group Exercise: A randomized pilot trial of an Integrative Exercise program for veterans with posttraumatic stress. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:345-352. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.002

31. Hall KS, Morey MC, Bosworth HB, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of exercise training for older veterans with PTSD. J Behav Med. 2020;43(4):648-659. doi:10.1007/s10865-019-00073-w

32. Gaddy MA. Implementation of an integrative medicine treatment program at a Veterans Health Administration residential mental health facility. Psychol Serv. 2018;15(4):503- 509. doi:10.1037/ser0000189

33. Werner CM, Hecksteden A, Morsch A, et al. Differential effects of endurance, interval, and resistance training on telomerase activity and telomere length in a randomized, controlled study. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(1):34- 46. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy585

34. Silverman MN, Deuster PA. Biological mechanisms underlying the role of physical fitness in health and resilience. Interface Focus. 2014;4(5):20140040. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2014.0040

35. Smith PJ, Merwin RM. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: an integrative review. Annu Rev Med. 2021;72:45-62. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060619-022943.

Physical exercise offers preventative and therapeutic benefits for a range of chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer disease, and depression.1,2 Exercise has been well studied for its antidepressant effects, its ability to reduce risk of aging-related dementia, and favorable effects on a range of cognitive functions.2 Lesser evidence exists regarding the impact of exercise on other mental health concerns. Therefore, an accurate understanding of whether physical exercise may ameliorate other conditions is important.

A small meta-analysis by Rosenbaum and colleagues found that exercise interventions were superior to control conditions for symptom reduction in study participants with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 This meta-analysis included 4 randomized clinical trials representing 200 cases. The trial included a variety of physical activities (eg, yoga, aerobic, and strength-building exercises) and control conditions, and participants recruited from online, community, inpatient, and outpatient settings. The standardized mean difference (SMD) produced by the analysis indicated a small-to-medium effect (Hedges g, -0.35), with the authors reporting no evidence of publication bias, although an assessment of potential bias associated with individual trial design characteristics was not conducted. Of note, a meta-analysis by Watts and colleagues found that effect sizes for PTSD treatments tend to be smaller in veteran populations.4 Therefore, how much the mean effect size estimate in the study is applicable to veterans with PTSD is unknown.3

Veterans represent a unique subpopulation in which PTSD is common, although no meta-analysis yet published has synthesized the effects of exercise interventions from trials of veterans with PTSD.5 A recent systematic review by Whitworth and Ciccolo concluded that exercise may be associated with reduced risk of PTSD, a briefer course of PTSD symptoms, and/or reduced sleep- and depression-related difficulties.6 However, that review primarily included observational, cross-sectional, and qualitative works. No trials included in our meta-analysis were included in that review.6

Evidence-based psychotherapies like cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure have been shown to be effective for treating PTSD in veterans; however, these modalities are accompanied by high rates of dropout (eg, 40-60%), thereby limiting their clinical utility.7 The use of complementary and alternative approaches for treatment in the United States has increased in recent years, and exercise represents an important complementary treatment option.8 In a study by Baldwin and colleagues, nearly 50% of veterans reported using complementary or alternative approaches, and veterans with PTSD were among those likely to use such approaches.9 However, current studies of the effects of exercise interventions on PTSD symptom reduction are mostly small and varied, making determinations difficult regarding the potential utility of exercise for treating this condition in veterans.

Literature Search

No previous research has synthesized the literature on the effects of exercise on PTSD in the veteran population. The current meta-analysis aims to provide a synthesis of systematically selected studies on this topic to determine whether exercise-based interventions are effective at reducing veterans’ symptoms of PTSD. Our hypothesis was that, when used as a primary or adjuvant intervention for PTSD, physical exercise would be associated with a reduction of PTSD symptom scale scores. We planned a priori to produce separate estimates for single-arm and multi-arm trials. We also wanted to conduct a careful risk of bias assessment—or evaluation of study features that may have systematically influenced results—for included trials, not only to provide context for interpretation of results, but also to inform suggestions for research to advance this field of inquiry.10

Methods

This study was preregistered on PROSPERO and followed PRISMA guidelines for meta-analyses and systematic reviews.11 Supplementary materials, such as the PRISMA checklist, study data, and funnel plots, are available online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1). Conference abstracts were omitted due to a lack of necessary information. We decided early in the planning process to include both randomized and single-arm trials, expecting the number of completed studies in the area of exercise for PTSD symptom reduction in veterans, and particularly randomized trials of such, would be relatively small.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study was a single- or multi-arm interventional trial; (2) participants were veterans; (3) participants had a current diagnosis of PTSD or exhibited subthreshold PTSD symptoms, as established by authors of the individual studies and supported by a structured clinical interview, semistructured interview, or elevated scores on PTSD symptom self-report measures; (4) the study included an intervention in which exercise (physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive in the sense that improvement or maintenance of physical fitness or health is an objective) was the primary component; (5) PTSD symptom severity was by a clinician-rated or self-report measure; and (6) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal.12 Studies were excluded if means, standard deviations, and sample sizes were not available or the full text of the study was not available in English.

The systematic review was conducted using PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases, from the earliest record to February 2021. The following search phrase was used, without additional limits, to acquire a list of potential studies: (“PTSD” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “posttraumatic stress disorder” or “post traumatic stress disorder”) and (“veteran” or “veterans”) and (“exercise” or “aerobic” or “activity” or “physical activity”). The references of identified publications also were searched for additional studies. Then, study titles and abstracts were evaluated and finally, full texts were evaluated to determine study inclusion. All screening, study selection, and risk of bias and data extraction activities were performed by 2 independent reviewers (DR and MJ) with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus (Figure 1). A list of studies excluded during full-text review and rationales can be viewed online (doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5618437.v1).

Data Collection

Data were extracted from included studies using custom forms and included the following information based on PRISMA guidelines: (1) study design characteristics; (2) intervention details; and (3) PTSD outcome information.11 PTSD symptom severity was the primary outcome of interest. Outcome data were included if they were derived from a measure of PTSD symptoms—equivalency across measures was assumed for meta-analyses. Potential study bias for each outcome was evaluated using the ROBINS-I and Cochrane Collaboration’s RoB 2 tools for single-arm and multi-arm trials, respectively.13,14 These tools evaluate domains related to the design, conduct, and analysis of studies that are associated with bias (ie, systematic error in findings, such as under- or overestimation of results).10 Examples include how well authors performed and concealed randomization procedures, addressed missing data, and measured study outcomes.13,14 The risk of bias (eg, low, moderate, serious) associated with each domain is rated and, based on the domain ratings, each study is then given an overall rating regarding how much risk influences bias.13,14 Broadly, lower risk of bias corresponds to higher confidence in the validity of results.

Finally, 4 authors (associated with 2 single- and 2 multi-arm studies) were contacted and asked to provide further information. Data for 1 additional multi-arm study were obtained from these communications and included in the final study selection.15 These authors were also asked for information about any unpublished works of which they were aware, although no additional works were identified.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed with R Studio R 3.6.0 software.16 An SMD (also known as Hedges g) was calculated for each study outcome: for single-arm trials, this was the SMD between pre- and postintervention scores, whereas for multi-arm trials, this was the SMD between postintervention outcome scores across groups. CIs for each SMD were calculated using a standard normal distribution. Combined SMDs were estimated separately for single- and multi-arm studies, using random-effects meta-analyses. In order to include multiple relevant outcomes from a single trial (ie, for studies using multiple PTSD symptom measures), robust variance estimation was used.17 Precision was used to weight SMDs.

Correlations between pre- and postintervention scores were not available for 1 single-arm study.18 A correlation coefficient of 0.8 was imputed to calculate the standard error of the of the SMDs for the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the PTSD Checklist (PCL), as this value is consistent with past findings regarding the test-retest reliability of these measures.19-22 A sensitivity analysis, using several alternative correlational values, revealed that the choice of correlation coefficient did not impact the overall results of the meta-analysis.

I2 was used to evaluate between-study heterogeneity. Values of I2 > 25%, 50%, and 75% were selected to reflect low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively, in accordance with guidelines described by Higgins and colleagues.23 Potential publication bias was assessed via funnel plot and Egger test.24 Finally, although collection of depressive symptom scores was proposed as a secondary outcome in the study protocol, such data were available only for 1 multi-arm study. As a result, this outcome was not evaluated.

Results

Six studies with 101 total participants were included in the single-arm analyses (Table 1).18,25-29 Participants consisted of veterans with chronic pain, post-9/11 veterans, female veterans of childbearing age, veterans with a history of trauma therapy, and other veterans. Types of exercise included moderate aerobic exercise and yoga. PTSD symptom measures included the CAPS and the PCL (PCL-5 or PCL-M versions). Reported financial sources for included studies included federal grant funding, nonprofit material support, outside organization support, use of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) resources, and no reported financial support.

With respect to individual studies, Shivakumar and colleagues found that completion of an aerobic exercise program was associated with reduced scores on 2 different PTSD symptom scales (PCL and CAPS) in 16 women veterans.18 A trauma-informed yoga intervention study with 18 participants by Cushing and colleagues demonstrated veteran participation to be associated with large reductions in PTSD, anxiety, and depression scale scores.25 In a study with 34 veterans, Chopin and colleagues found that a trauma-informed yoga intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, as did a study by Zaccari and colleagues with 17 veterans.26,29 Justice and Brems also found some evidence that trauma-informed yoga interventions helped PTSD symptoms in a small sample of 4 veterans, although these results were not quantitatively analyzed.27 In contrast, a small pilot study (n = 12) by Staples and colleagues testing a biweekly, 6-week yoga program did not show a significant effect on PTSD symptoms.28

Three studies with 217 total veteran participants were included in the multi-arm analyses (Table 2).15,30,31 As all multi-arm trials incorporated randomization, they will be referred to as randomized controlled trials (RCTs). On contact, Davis and colleagues provided veteran-specific results for their trial; as such, our data differ from those within the published article.15 Participants from all included studies were veterans currently experiencing symptoms of PTSD. Types of exercise included yoga and combined methods (eg, aerobic and strength training).15,30,31 PTSD symptom measures included the CAPS or the PCL-5.15,30,31 Reported financial sources for included studies included federal grant funding, as well as nonprofit support, private donations, and VA and Department of Defense resources.

Davis and colleagues conducted a recently concluded RCT with > 130 veteran participants and found that a novel manualized yoga program was superior to an attention control in reducing PTSD symptom scale scores for veterans.15 Goldstein and colleagues found that a program consisting of both aerobic and resistance exercises reduced PTSD symptoms to a greater extent than a waitlist control condition, with 47 veterans randomized in this trial.30 Likewise, Hall and colleagues conducted a pilot RCT in which an intervention that integrated exercise and cognitive behavioral techniques was compared to a waitlist control condition.31 For the 48 veterans included in the analyses, the authors reported greater PTSD symptom reduction associated with integrated exercise than that of the control condition; however, the study was not powered to detect statistically significant differences between groups.

Bias Assessment

Results for the risk of bias assessments can be viewed in Tables 3 and 4. For single-arm studies, overall risk of bias was serious for all included trials. Serious risk of bias was found in 2 domains: confounding, due to a lack of accounting for potential preexisting baseline trends (eg, regression to the mean) that could have impacted study results; and measurement, due to the use of a self-report symptom measure (PCL) or CAPS with unblinded assessors. Multiple studies also showed moderate risk in the missing data domain due to participant dropout without appropriate analytic methods to address potential bias.

For RCTs, overall risk of bias ranged from some concerns to high risk. High risk of bias was found in 1 domain, measurement of outcome, due to use of a self-report symptom measure (PCL) with unblinded groups.31 The other 2 studies all had some concern of bias in at least 1 of the following domains: randomization, missing data, and measurement of outcome.

Pooled Standardized Mean Differences

Meta-analytic results can be viewed in Figure 2. The pooled SMD for the 6 single-arm studies was -0.60 (df = 4.41, 95% CI, -1.08 to -0.12, P = .03), indicating a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms over the course of an exercise intervention. Combining SMDs for the 3 included RCTs revealed a pooled SMD of -0.40 (df = 1.57, 95% CI, -0.86 to 0.06, P = .06), indicating that exercise did not result in a statistically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms compared with control conditions.

Publication Bias and Heterogeneity

Visual inspection funnel plots and Egger test did not suggest the presence of publication bias for RCTs (t = 1.21, df = 2, P = .35) or single-arm studies (t = -0.36, df = 5, P = .73).

Single-arm studies displayed a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 81.5%). Including sample size or exercise duration as variables in meta-regressions did not reduce heterogeneity (I2 = 85.2% and I2 = 83.8%, respectively). Performing a subgroup analysis only on studies using yoga as an intervention also did not reduce heterogeneity (I2 = 79.2%). Due to the small number of studies, no further exploration of heterogeneity was conducted on single-arm studies. RCTs did not display any heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Discussion

Our report represents an early synthesis of the first prospective studies of physical exercise interventions for PTSD in veterans. Results from meta-analyses of 6 single-arm studies (101 participants) and 3 RCTs (217 participants) provide early evidence that exercise may reduce PTSD symptoms in veterans. Yoga was the most common form of exercise used in single-arm studies, whereas RCTs used a wider range of interventions. The pooled SMD of -0.60 for single-arm longitudinal studies suggest a medium decrease in PTSD symptoms for veterans who engage in exercise interventions. Analysis of the RCTs supported this finding, with a pooled SMD of -0.40 reflecting a small-to-medium effect of exercise on PTSD symptoms over control conditions, although this result did not achieve statistical significance. Of note, while the nonsignificant finding for RCTs may have been due to insufficient power caused by the limited number of included studies, possibly exercise was not more efficacious than were the control conditions.

Although RCTs represented a variety of exercise types, PTSD symptom measures, and veteran subgroups, statistical results were not indicative of heterogeneity. However, only the largest and most comprehensive study of exercise for PTSD in veterans to date by Davis and colleagues had a statistically significant SMD.15 Of note, one of the other 2 RCTs displayed an SMD of a similar magnitude, but this study had a much smaller sample size and was underpowered to detect significance.30 Additionally, risk of bias assessments for single-arm studies and RCTs revealed study characteristics that suggest possible inflation of absolute effect sizes for individual studies. Therefore, the pooled SMDs we report are interpretable but may exceed the true effect of exercise for PTSD symptom reduction in veterans.

Based on results of our analyses, it is reasonable, albeit preliminary, to conclude that exercise interventions may result in reduced PTSD symptoms among veterans. At the very least, these findings support the continued investigation of such interventions for veterans. Given the unique and salubrious characteristics of physical exercise, such results, if supported by further research, suggest that exercise-based interventions may be particularly valuable within the trauma treatment realm. For example, exercise can be less expensive and more convenient than attending traditional treatment, and for veterans reluctant to engage in standard treatment approaches such as psychiatric and psychosocial modalities, complementary approaches entailing exercise may be viewed as particularly acceptable or enjoyable.32 In addition to possibly reducing PTSD symptoms, exercise is a well-established treatment for conditions commonly comorbid with PTSD, including depression, anxiety disorders, cognitive difficulties, and certain chronic pain conditions.6 As such, exercise represents a holistic treatment option that has the potential to augment standard PTSD care.

Limitations

The present study has several important limitations. First, few studies were found that met the broad eligibility criteria and those that did often had a small sample size. Besides highlighting a gap in the extant research, the limited studies available for meta-analysis means that caution must be taken when interpreting results. Fortunately, this issue will likely resolve once additional studies investigating the impact of exercise on PTSD symptoms in veterans are available for synthesis.

Relatedly, the included study interventions varied considerably, both in the types of exercise used and the characteristics of the exercises (eg, frequency, duration, and intensity), which is relevant as different exercise modalities are associated with differential physical effects.33 Including such a mixture of exercises may have given an incomplete picture of their potential therapeutic effects. Also, none of the RCTs compared exercise against first-line treatments for PTSD, such as prolonged exposure or cognitive processing therapy, which would have provided further insight into the role exercise could play in clinical settings.7

Another limitation is the elevated risk of bias found in most studies, particularly present in the longitudinal single-arm studies, all of which were rated at serious risk. For instance, no single-arm study controlled for preexisting baseline trends: without such (and lacking a comparison control group like in RCTs), it is possible that the observed effects were due to extraneous factors, rather than the exercise intervention. Although not as severe, the multi-arm RCTs also displayed at least moderate risk of bias. Therefore, SMDs may have been overestimated for each group of studies.

Finally, the results of the single-arm meta-analysis displayed high statistical heterogeneity, reducing the generalizability of the results. One possible cause of this heterogeneity may have been the yoga interventions, as a separate analysis removing the only nonyoga study did not reduce heterogeneity. This result was surprising, as the included yoga interventions seemed similar across studies. While the presence of high heterogeneity does require some caution when applying these results to outside interventions, the present study made use of random-effects meta-analysis, a technique that incorporates study heterogeneity into the statistical model, thereby strengthening the findings compared with that of a traditional fixed-effects approach.10

Future Steps

Several future steps are warranted to improve knowledge of exercise as a treatment for PTSD in veterans and in the general population. With current meta-analyses limited to small numbers of studies, additional studies of the efficacy of exercise for treating PTSD could help in several ways. A larger pool of studies would enable future meta-analyses to explore related questions, such as those regarding the impact of exercise on quality of life or depressive symptom reduction among veterans with PTSD. A greater number of studies also would enable meta-analysts to explore potentially critical moderators. For example, the duration, frequency, or type of exercise may moderate the effect of exercise on PTSD symptom reduction. Moderators related to patient or study design characteristics also should be explored in future studies.