User login

Chronic insomnia afflicts one in three perimenopausal women

LAS VEGAS – Sleeplessness is both common and distressing for women in midlife, according to a new analysis of data from a large observational study.

One-third of women at all stages of the menopausal transition reported sleep disturbance that met the clinical criteria for insomnia, regardless of many markers of health and socioeconomic status, Colleen L. Ciano, Ph.D., reported at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Acute insomnia is prevalent in adults, and women are known to suffer more than men from chronic insomnia. Perimenopausal women, in particular, may have increased sleep disturbances.

Dr. Ciano, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the large, longitudinal Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) to ascertain insomnia’s prevalence in perimenopausal and surgically menopausal women. Using SWAN study data, she also attempted to tease out factors that might increase a woman’s risk for chronic insomnia.

SWAN, said Dr. Ciano, was designed to examine the health of midlife women, gathering data from 3,302 women with a mean age of 45.9 years. Ten years of study data are now available from an ethnically diverse sample of women participating at seven sites across the United States.

Four questions from the SWAN questionnaire were identified for analysis as dependent variables. The questions related to trouble falling asleep, nighttime wakings, early-morning wakings, and a subjective rating of sleep quality over 2 weeks. Women were stratified into early or late menopause, or surgical menopause.

More than one-third of women at all stages of the midlife transition, or who were in surgical menopause, reported diagnosable insomnia. On the whole, insomnia increased for women over the study period. Waking after sleep onset also increased for perimenopausal women as they moved through menopause, from 26% to 36%. Sleep quality, as a bifurcated measure of sleep quality derived from a four-point scale, also dropped over the study period.

During the SWAN data collection period, the number of perimenopausal women who met at least one of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria for insomnia rose from just over 30% to just over 40%, while the number of women who reported no insomnia symptoms fell steeply, dropping from just under 70% to approximately 50%.

When Dr. Ciano analyzed the prevalence of insomnia by perimenopausal stage, she found more insomnia in late-perimenopausal women (prevalence 31%-48%), compared with those in early menopause (31%-59%).

Women in late perimenopause had an odds ratio of 1.3 of reporting any symptom of insomnia, compared with those in early menopause, according to Dr. Ciano.

Women who were heavier, older, or depressed, as well as those having night sweats, were all more likely to suffer from insomnia on multivariable analysis (all P=0.002 or less). Factors that did not influence insomnia included marital status, tobacco or alcohol use, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and many comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Ciano advised clinicians to pay attention to these findings and initiate insomnia screenings. Routine evaluation of perimenopausal women should include careful questioning and an assessment of sleep patterns and problems. This is especially important since obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are all prevalent chronic illnesses that can be impacted by insomnia, she said.

Future studies should include physiologic measures and objective sleep data, which could be correlated with subjective reports, said Dr. Ciano. Sleep diaries can be an adjunct to observational and objective data, and can be correlated with such objective measures as endogenous hormone levels and objective vasomotor symptom monitoring.

Dr. Ciano’s research was supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research, Pennsylvana State University, and the Beta Sigma chapter of Sigma Theta Tau. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Sleeplessness is both common and distressing for women in midlife, according to a new analysis of data from a large observational study.

One-third of women at all stages of the menopausal transition reported sleep disturbance that met the clinical criteria for insomnia, regardless of many markers of health and socioeconomic status, Colleen L. Ciano, Ph.D., reported at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Acute insomnia is prevalent in adults, and women are known to suffer more than men from chronic insomnia. Perimenopausal women, in particular, may have increased sleep disturbances.

Dr. Ciano, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the large, longitudinal Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) to ascertain insomnia’s prevalence in perimenopausal and surgically menopausal women. Using SWAN study data, she also attempted to tease out factors that might increase a woman’s risk for chronic insomnia.

SWAN, said Dr. Ciano, was designed to examine the health of midlife women, gathering data from 3,302 women with a mean age of 45.9 years. Ten years of study data are now available from an ethnically diverse sample of women participating at seven sites across the United States.

Four questions from the SWAN questionnaire were identified for analysis as dependent variables. The questions related to trouble falling asleep, nighttime wakings, early-morning wakings, and a subjective rating of sleep quality over 2 weeks. Women were stratified into early or late menopause, or surgical menopause.

More than one-third of women at all stages of the midlife transition, or who were in surgical menopause, reported diagnosable insomnia. On the whole, insomnia increased for women over the study period. Waking after sleep onset also increased for perimenopausal women as they moved through menopause, from 26% to 36%. Sleep quality, as a bifurcated measure of sleep quality derived from a four-point scale, also dropped over the study period.

During the SWAN data collection period, the number of perimenopausal women who met at least one of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria for insomnia rose from just over 30% to just over 40%, while the number of women who reported no insomnia symptoms fell steeply, dropping from just under 70% to approximately 50%.

When Dr. Ciano analyzed the prevalence of insomnia by perimenopausal stage, she found more insomnia in late-perimenopausal women (prevalence 31%-48%), compared with those in early menopause (31%-59%).

Women in late perimenopause had an odds ratio of 1.3 of reporting any symptom of insomnia, compared with those in early menopause, according to Dr. Ciano.

Women who were heavier, older, or depressed, as well as those having night sweats, were all more likely to suffer from insomnia on multivariable analysis (all P=0.002 or less). Factors that did not influence insomnia included marital status, tobacco or alcohol use, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and many comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Ciano advised clinicians to pay attention to these findings and initiate insomnia screenings. Routine evaluation of perimenopausal women should include careful questioning and an assessment of sleep patterns and problems. This is especially important since obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are all prevalent chronic illnesses that can be impacted by insomnia, she said.

Future studies should include physiologic measures and objective sleep data, which could be correlated with subjective reports, said Dr. Ciano. Sleep diaries can be an adjunct to observational and objective data, and can be correlated with such objective measures as endogenous hormone levels and objective vasomotor symptom monitoring.

Dr. Ciano’s research was supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research, Pennsylvana State University, and the Beta Sigma chapter of Sigma Theta Tau. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Sleeplessness is both common and distressing for women in midlife, according to a new analysis of data from a large observational study.

One-third of women at all stages of the menopausal transition reported sleep disturbance that met the clinical criteria for insomnia, regardless of many markers of health and socioeconomic status, Colleen L. Ciano, Ph.D., reported at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Acute insomnia is prevalent in adults, and women are known to suffer more than men from chronic insomnia. Perimenopausal women, in particular, may have increased sleep disturbances.

Dr. Ciano, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues used data from the large, longitudinal Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) to ascertain insomnia’s prevalence in perimenopausal and surgically menopausal women. Using SWAN study data, she also attempted to tease out factors that might increase a woman’s risk for chronic insomnia.

SWAN, said Dr. Ciano, was designed to examine the health of midlife women, gathering data from 3,302 women with a mean age of 45.9 years. Ten years of study data are now available from an ethnically diverse sample of women participating at seven sites across the United States.

Four questions from the SWAN questionnaire were identified for analysis as dependent variables. The questions related to trouble falling asleep, nighttime wakings, early-morning wakings, and a subjective rating of sleep quality over 2 weeks. Women were stratified into early or late menopause, or surgical menopause.

More than one-third of women at all stages of the midlife transition, or who were in surgical menopause, reported diagnosable insomnia. On the whole, insomnia increased for women over the study period. Waking after sleep onset also increased for perimenopausal women as they moved through menopause, from 26% to 36%. Sleep quality, as a bifurcated measure of sleep quality derived from a four-point scale, also dropped over the study period.

During the SWAN data collection period, the number of perimenopausal women who met at least one of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria for insomnia rose from just over 30% to just over 40%, while the number of women who reported no insomnia symptoms fell steeply, dropping from just under 70% to approximately 50%.

When Dr. Ciano analyzed the prevalence of insomnia by perimenopausal stage, she found more insomnia in late-perimenopausal women (prevalence 31%-48%), compared with those in early menopause (31%-59%).

Women in late perimenopause had an odds ratio of 1.3 of reporting any symptom of insomnia, compared with those in early menopause, according to Dr. Ciano.

Women who were heavier, older, or depressed, as well as those having night sweats, were all more likely to suffer from insomnia on multivariable analysis (all P=0.002 or less). Factors that did not influence insomnia included marital status, tobacco or alcohol use, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and many comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Ciano advised clinicians to pay attention to these findings and initiate insomnia screenings. Routine evaluation of perimenopausal women should include careful questioning and an assessment of sleep patterns and problems. This is especially important since obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are all prevalent chronic illnesses that can be impacted by insomnia, she said.

Future studies should include physiologic measures and objective sleep data, which could be correlated with subjective reports, said Dr. Ciano. Sleep diaries can be an adjunct to observational and objective data, and can be correlated with such objective measures as endogenous hormone levels and objective vasomotor symptom monitoring.

Dr. Ciano’s research was supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research, Pennsylvana State University, and the Beta Sigma chapter of Sigma Theta Tau. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE NAMS 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: One in three perimenopausal women has persistent insomnia.

Major finding: An average of one-third of perimenopausal women have significant symptoms of insomnia, higher than age-matched prevalence in the general population.

Data source: Analysis of the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a multi-site longitudinal study of 3,302 ethnically diverse midlife-aged women.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research, Pennsylvana State University, and the Beta Sigma chapter of Sigma Theta Tau. Dr. Ciano reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Ask, listen, help: Pearls to treat sexual dysfunction in menopause

LAS VEGAS – The first step is to ask. A menopausal woman may be struggling with a female sexual disorder (FSD), but unless her clinician asks, the patient may never volunteer information about her sexual health.

Susan Kellogg Spadt, Ph.D., offered that advice, along with a toolkit of tips, treatments, and pearls for physicians and others caring for the menopausal woman’s sexual health.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt, a certified sexual counselor and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Drexel University, Philadelphia, addressed FSD in the context of the complicated psychosocial landscape of midlife.

Women at this stage of life may be experiencing life stress as children move out, retirement looms, and aging parents require time and attention. Also, as women age, they are more likely to require medications that can negatively affect sexual health. Body image issues, depression, anxiety, and discrepancy with partner desire levels can all be prevalent in women aged 45-64 years, the group most likely to experience distress from sexual problems, she said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

This is important in the context of a relationship, said Dr. Kellogg Spadt. She pointed out that “when sex is good, it adds a little bit – like icing on the cupcake – to a good relationship.” But when sex is bad or nonexistent, she said, it plays an inordinately negative role, reducing the quality of the relationship by 50%-70% in some studies.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt said a good opening approach should confirm the ubiquity of sexual problems in midlife and normalize concerns. Clinicians can ask: “With menopause, many women have changes in their sexual response. These concerns are very common. Tell me – are you feeling well and complete in your sex life?”

If questioning reveals unsatisfying or nonexistent sex, many problems can be addressed in the office. First, careful questioning and an exam can tease out the extent to which dyspareunia and vaginal dryness may be limiting sexual pleasure. In that case, lubricants, moisturizers, and topical estrogen can be considered.

Office sessions with physical therapists certified in pelvic issues, combined with home use of dilators, can help overcome physical contributors to an uncomfortable sexual experience, she said.

Clinicians can also provide brief office-based counseling using the “PLISSIT” model, which. gives permission for the patient to speak openly about sexual issues; provides limited information to educate the patient about her anatomy and resources available; offers specific suggestions, for example, positioning tips or moisturizer recommendations; and offers intensive therapy, when indicated, such as referring for adjunctive psychotherapy.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt concluded with her top clinical pearls for sexual health in menopausal women:

• Add moisture daily. Using a water-based, bioadhesive lubricant several times a week regardless of sexual frequency can significantly ease comfort and satisfaction with sex and make it easier to have an orgasm.

• Nourish. A Mediterranean diet has been shown to promote sexual function, and regular exercise improves mood and overall health.

• Talk. Partners can use “I” language to talk about sex honestly and in a nonaccusatory way. Clinicians can help provide the vocabulary and communication tips to facilitate this.

• Prioritize pleasure. Intimate time together won’t just happen; even a 20-minute block of time, scheduled weekly, for touching and intimate conversation can clear the way to better sex.

• Think. Reading or watching erotica, being mindful of erotic thoughts as they occur, and focusing on sensation rather than distractions during arousal are all important.

• Stimulate. After menopause, some women need more intense stimulation to reach orgasm, so vibrators can be incorporated into sex play. Women who are uncomfortable with this can use the “doctor’s orders” approach with their partners.

• Try. Just opening up and talking about sex problems shows that a woman is committed to her partner, and taking action shows her level of care and concern for the relationship.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt reported being a consultant or on the advisory board of Neogyn and Nuelle, and on the speakers bureau of Novo Nordisk and Shionogi.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – The first step is to ask. A menopausal woman may be struggling with a female sexual disorder (FSD), but unless her clinician asks, the patient may never volunteer information about her sexual health.

Susan Kellogg Spadt, Ph.D., offered that advice, along with a toolkit of tips, treatments, and pearls for physicians and others caring for the menopausal woman’s sexual health.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt, a certified sexual counselor and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Drexel University, Philadelphia, addressed FSD in the context of the complicated psychosocial landscape of midlife.

Women at this stage of life may be experiencing life stress as children move out, retirement looms, and aging parents require time and attention. Also, as women age, they are more likely to require medications that can negatively affect sexual health. Body image issues, depression, anxiety, and discrepancy with partner desire levels can all be prevalent in women aged 45-64 years, the group most likely to experience distress from sexual problems, she said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

This is important in the context of a relationship, said Dr. Kellogg Spadt. She pointed out that “when sex is good, it adds a little bit – like icing on the cupcake – to a good relationship.” But when sex is bad or nonexistent, she said, it plays an inordinately negative role, reducing the quality of the relationship by 50%-70% in some studies.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt said a good opening approach should confirm the ubiquity of sexual problems in midlife and normalize concerns. Clinicians can ask: “With menopause, many women have changes in their sexual response. These concerns are very common. Tell me – are you feeling well and complete in your sex life?”

If questioning reveals unsatisfying or nonexistent sex, many problems can be addressed in the office. First, careful questioning and an exam can tease out the extent to which dyspareunia and vaginal dryness may be limiting sexual pleasure. In that case, lubricants, moisturizers, and topical estrogen can be considered.

Office sessions with physical therapists certified in pelvic issues, combined with home use of dilators, can help overcome physical contributors to an uncomfortable sexual experience, she said.

Clinicians can also provide brief office-based counseling using the “PLISSIT” model, which. gives permission for the patient to speak openly about sexual issues; provides limited information to educate the patient about her anatomy and resources available; offers specific suggestions, for example, positioning tips or moisturizer recommendations; and offers intensive therapy, when indicated, such as referring for adjunctive psychotherapy.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt concluded with her top clinical pearls for sexual health in menopausal women:

• Add moisture daily. Using a water-based, bioadhesive lubricant several times a week regardless of sexual frequency can significantly ease comfort and satisfaction with sex and make it easier to have an orgasm.

• Nourish. A Mediterranean diet has been shown to promote sexual function, and regular exercise improves mood and overall health.

• Talk. Partners can use “I” language to talk about sex honestly and in a nonaccusatory way. Clinicians can help provide the vocabulary and communication tips to facilitate this.

• Prioritize pleasure. Intimate time together won’t just happen; even a 20-minute block of time, scheduled weekly, for touching and intimate conversation can clear the way to better sex.

• Think. Reading or watching erotica, being mindful of erotic thoughts as they occur, and focusing on sensation rather than distractions during arousal are all important.

• Stimulate. After menopause, some women need more intense stimulation to reach orgasm, so vibrators can be incorporated into sex play. Women who are uncomfortable with this can use the “doctor’s orders” approach with their partners.

• Try. Just opening up and talking about sex problems shows that a woman is committed to her partner, and taking action shows her level of care and concern for the relationship.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt reported being a consultant or on the advisory board of Neogyn and Nuelle, and on the speakers bureau of Novo Nordisk and Shionogi.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – The first step is to ask. A menopausal woman may be struggling with a female sexual disorder (FSD), but unless her clinician asks, the patient may never volunteer information about her sexual health.

Susan Kellogg Spadt, Ph.D., offered that advice, along with a toolkit of tips, treatments, and pearls for physicians and others caring for the menopausal woman’s sexual health.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt, a certified sexual counselor and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Drexel University, Philadelphia, addressed FSD in the context of the complicated psychosocial landscape of midlife.

Women at this stage of life may be experiencing life stress as children move out, retirement looms, and aging parents require time and attention. Also, as women age, they are more likely to require medications that can negatively affect sexual health. Body image issues, depression, anxiety, and discrepancy with partner desire levels can all be prevalent in women aged 45-64 years, the group most likely to experience distress from sexual problems, she said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

This is important in the context of a relationship, said Dr. Kellogg Spadt. She pointed out that “when sex is good, it adds a little bit – like icing on the cupcake – to a good relationship.” But when sex is bad or nonexistent, she said, it plays an inordinately negative role, reducing the quality of the relationship by 50%-70% in some studies.

Dr. Kellogg Spadt said a good opening approach should confirm the ubiquity of sexual problems in midlife and normalize concerns. Clinicians can ask: “With menopause, many women have changes in their sexual response. These concerns are very common. Tell me – are you feeling well and complete in your sex life?”

If questioning reveals unsatisfying or nonexistent sex, many problems can be addressed in the office. First, careful questioning and an exam can tease out the extent to which dyspareunia and vaginal dryness may be limiting sexual pleasure. In that case, lubricants, moisturizers, and topical estrogen can be considered.

Office sessions with physical therapists certified in pelvic issues, combined with home use of dilators, can help overcome physical contributors to an uncomfortable sexual experience, she said.

Clinicians can also provide brief office-based counseling using the “PLISSIT” model, which. gives permission for the patient to speak openly about sexual issues; provides limited information to educate the patient about her anatomy and resources available; offers specific suggestions, for example, positioning tips or moisturizer recommendations; and offers intensive therapy, when indicated, such as referring for adjunctive psychotherapy.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt concluded with her top clinical pearls for sexual health in menopausal women:

• Add moisture daily. Using a water-based, bioadhesive lubricant several times a week regardless of sexual frequency can significantly ease comfort and satisfaction with sex and make it easier to have an orgasm.

• Nourish. A Mediterranean diet has been shown to promote sexual function, and regular exercise improves mood and overall health.

• Talk. Partners can use “I” language to talk about sex honestly and in a nonaccusatory way. Clinicians can help provide the vocabulary and communication tips to facilitate this.

• Prioritize pleasure. Intimate time together won’t just happen; even a 20-minute block of time, scheduled weekly, for touching and intimate conversation can clear the way to better sex.

• Think. Reading or watching erotica, being mindful of erotic thoughts as they occur, and focusing on sensation rather than distractions during arousal are all important.

• Stimulate. After menopause, some women need more intense stimulation to reach orgasm, so vibrators can be incorporated into sex play. Women who are uncomfortable with this can use the “doctor’s orders” approach with their partners.

• Try. Just opening up and talking about sex problems shows that a woman is committed to her partner, and taking action shows her level of care and concern for the relationship.

Dr. Kellogg Stadt reported being a consultant or on the advisory board of Neogyn and Nuelle, and on the speakers bureau of Novo Nordisk and Shionogi.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NAMS 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Does hormone therapy reduce mortality in recently menopausal women?

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

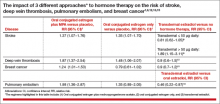

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Clinicians work to maximize the quality of life and longevity of every patient. For women with moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, oral estrogen therapy can improve quality of life, but at the cost of significant adverse effects. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) reported that for postmenopausal women with a uterus, conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE+MPA) hormone therapy (HT) versus placebo significantly increased the risk of cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR], 1.13), breast cancer (RR, 1.24), stroke (RR, 1.37), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.87), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.98).1 In postmeno pausal women without a uterus, CEE HT did not increase the risk of breast cancer (RR, 0.79), compared with placebo, but it did significantly in crease the risk of cardiovascular events (RR, 1.11), stroke (RR, 1.35), deep vein thrombosis (RR, 1.48), and pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.35).1

Clinicians prescribing estrogen must individualize therapy according to its benefits and risks. An important issue that has received insufficient at tention is, “What is the effect of HT on mortality in recently menopausal women?” Here, I examine this issue.

HT reduces mortality in recently menopausal women

Pooling the results of the WHI CEE+MPA and CEE-only trials reveals that there were 70 deaths in the HT-treated groups and 98 deaths in the placebo groups among women aged 50 to 59 years.1 With 4,706 and 4,259 women alive at the conclusion of the study in the HT and placebo groups, respectively, the women in the placebo group had significantly more deaths than the women in the HT-treated groups (Fisher exact test, P = .0194, χ2 test with Yates correction, P = .0226).

Using pooled data from the WHI, the RR of death in the HT versus placebo group was estimated at 0.70 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51−0.96), representing approximately 5 fewer deaths per 1,000 women per 5 years of therapy.2 In women aged 60 to 69 years and 70 to 79 years there were no significant differences in death rates between the HT- and placebo-treated women.

My interpretation of these results is that HT likely is associated with a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women, but not in women distant from menopause onset.

Cochrane review of HT and mortality

Consistent with the WHI findings, authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials including 40,410 menopausal women reported that HT significantly increased the risk of stroke (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10−1.41), venous thromboembolism (RR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.36−2.69), and pulmonary emboli (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.32−2.48).3 However, among women treated with oral HT within 10 years after the start of menopause, there was a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (RR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.29−0.96). Using data from 5 clinical trials, the Cochrane meta-analysis researchers reported that, compared with placebo, HT reduced mortality (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52−0.95).3

Results of the Cochrane meta-analysis are consistent with those of a previous meta-analysis of 19 randomized trials involving 16,000 women. In this analysis, investigators found a reduced risk of death in recently menopausal women treated with hormone therapy (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.52−0.96).4

Early menopause, HT, and mortality

Authors of multiple large epidemiologic studies have reported that early menopause is associated with an increased risk of death if HT is not initiated.5−7 For example, results of a study of women in Olmsted County, Minnesota, conducted from 1950 to 1987, indicated that, for women younger than age 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy, the risk of death was increased among those who did not initiate HT, compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (hazard ratio [HR], 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27−2.68; P = .001).7

By contrast, women younger than 45 years who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and initiated estrogen therapy did not have an increased risk of death compared with women who did not undergo oophorectomy (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.30−1.41; P = .28).7 An excess number of cardiovascular events appeared to account for the increased mortality among women with early surgical menopause who did not initiate HT.

The “timing hypothesis” proposes that the initiation of HT soon after the onset of menopause is associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects, but initiation more than 10 years after the onset of menopause is not associated with beneficial cardiovascular effects. The timing hypothesis is supported by the finding that, in recently menopausal women, HT is associated with reduced carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), compared with placebo.8 Greater CIMT thickness is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

In my experience, few primary care clinicians are aware of these data. Often, these clinicians over-emphasize the risks and withhold HT in this vulnerable group of women.

HT: Minimizing the risks of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer

Results of multiple studies have shown that certain HT regimens increase the risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Is it possible to prescribe HT in a way that reduces these risks?

Results of observational studies indicate that, compared with oral estrogen therapy, transdermal HT is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer (TABLE).9−15

Reducing the risk of stroke caused by HT is an important goal. In a study of 15,710 women who had stroke and 59,958 control women aged 50 to 79 years, transdermal estradiol at a dose of 50 µg or less daily was not associated with an increased risk of stroke, compared with HT nonuse (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62−1.05).9 Compared with HT nonuse, the use of oral estrogen (rate ratio, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15−1.42) or transdermal estradiol 50 µg or greater daily (rate ratio, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.15−3.11) was associated with an increased risk of stroke.9

Reducing the risks of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism caused by HT is an important goal. In a meta-analysis of the risk of VTE with HT, compared with nonusers, oral estrogen therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of VTE (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9−3.4). Compared with nonuse, transdermal estrogen therapy was not associated with an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9−1.7).11 In a study comparing oral versus transdermal estradiol, transdermal estradiol was associated with a reduced risk of pulmonary embolism (0.46 [95% CI, 0.22−0.97]).13

Reducing the risk of breast cancer caused by HT is an important goal. Results of one study showed that the combination of oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1−1.9). By contrast, the combination of transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with nonuse (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7−1.2).15

The bottom line

In recently menopausal women with moderate to severe hot flashes, HT improves quality of life and appears to decrease mortality. However, HT with oral estrogen plus synthetic progestin is associated with an increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and breast cancer. Compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol treatment is associated with a lower risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Compared with oral estrogen plus a synthetic progestin, transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer. The benefits of HT are likely maximized by initiating therapy in the perimenopause transition or early in the postmenopause, and the risks are minimized by using transdermal estradiol.16−18

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post-stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353−1368.

- Santen RJ, Allred DC, Ardoin SP, et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(suppl 1):S1−S66.

- Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229.

- Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122(11):1016−1022.

- Gordon T, Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease: The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(2):157−161.

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willet WC, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the Nurses Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(11):756−762.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15−23.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Testing the menopausal hormone therapy timing hypothesis: the early versus late intervention trial with estradiol [abstract 13283]. American Heart Association Meeting 2014. Circulation. 2014;130:A13283.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979−986.

- Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7655):1227−1231.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340−345.

- Laliberte F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052−1059.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(11):2277−2286.

- Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(3):448−454.

- L’Hermite M. HRT optimization, using transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone, a safer HRT. Climacteric. 2013;16(suppl 1):44−53.

- Simon JA. What’s new in hormone replacement therapy: focus on transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1):3−10.

- Mueck AO. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: the value of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone. Climacteric. 2012;15(suppl 1): 11−17.

Individualizing treatment of menopausal symptoms

Menopause experts Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, and JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, provide a comprehensive review of various treatments for menopausal symptoms in an article recently published ahead of print in Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 They discuss hormonal and nonhormonal options to treat vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and considerations for the use of hormone therapy in special populations: women with early menopause, women with a history of breast cancer and those who carry the BRCA gene mutation, and women with a history of venous thrombosis.1

The authors write that, “given the lower rates of adverse events on HT among women close to menopause onset and at lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease, risk stratification and personalized risk assessment appear to represent a sound strategy for optimizing the benefit–risk profile and safety of HT.”1 They suggest that instead of stopping systemic HT at age 65 years, the length of treatment be individualized based on a woman’s risk profile and preferences. The authors encourage gynecologists and other clinicians to use benefit–risk profile tools for both hormonal and nonhormonal options to help women make sound decisions on treating menopausal symptoms.1

Readthe full Clinical Expert Series here.

Reference

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms [published online ahead of print September 3, 2015]. Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001058. Accessed September 18, 2015.

Menopause experts Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, and JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, provide a comprehensive review of various treatments for menopausal symptoms in an article recently published ahead of print in Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 They discuss hormonal and nonhormonal options to treat vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and considerations for the use of hormone therapy in special populations: women with early menopause, women with a history of breast cancer and those who carry the BRCA gene mutation, and women with a history of venous thrombosis.1

The authors write that, “given the lower rates of adverse events on HT among women close to menopause onset and at lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease, risk stratification and personalized risk assessment appear to represent a sound strategy for optimizing the benefit–risk profile and safety of HT.”1 They suggest that instead of stopping systemic HT at age 65 years, the length of treatment be individualized based on a woman’s risk profile and preferences. The authors encourage gynecologists and other clinicians to use benefit–risk profile tools for both hormonal and nonhormonal options to help women make sound decisions on treating menopausal symptoms.1

Readthe full Clinical Expert Series here.

Menopause experts Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, and JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, provide a comprehensive review of various treatments for menopausal symptoms in an article recently published ahead of print in Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 They discuss hormonal and nonhormonal options to treat vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and considerations for the use of hormone therapy in special populations: women with early menopause, women with a history of breast cancer and those who carry the BRCA gene mutation, and women with a history of venous thrombosis.1

The authors write that, “given the lower rates of adverse events on HT among women close to menopause onset and at lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease, risk stratification and personalized risk assessment appear to represent a sound strategy for optimizing the benefit–risk profile and safety of HT.”1 They suggest that instead of stopping systemic HT at age 65 years, the length of treatment be individualized based on a woman’s risk profile and preferences. The authors encourage gynecologists and other clinicians to use benefit–risk profile tools for both hormonal and nonhormonal options to help women make sound decisions on treating menopausal symptoms.1

Readthe full Clinical Expert Series here.

Reference

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms [published online ahead of print September 3, 2015]. Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001058. Accessed September 18, 2015.

Reference

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms [published online ahead of print September 3, 2015]. Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001058. Accessed September 18, 2015.

Turn down the androgens to treat female pattern hair loss

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

NEW YORK – Antiandrogen hormones can help stabilize, and even improve, female pattern hair loss.

The pathophysiology of the disorder is unknown, but treatment is based on the assumption that women must be like men, at least when it comes to losing their hair. Intuitively, decreasing androgens should help correct the problem.

The answer, though, is a complicated mix of yes and maybe, Dr. Rochelle Torgerson said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

“It used to be assumed that pattern hair loss in women was just the same as it is in men,” said Dr. Torgerson of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Now there is some evidence that’s not true. In 2010, for example, this was seen in a woman with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, so in her, androgens were not affecting hair follicles. There must be a place for estrogen.”

Further complicating the picture is the fact that no hormonal medications have FDA approval for hair loss in women, and their use has a history of conflicting data in clinical studies. Still, they remain the cornerstone for treating this physically and emotionally challenging problem.

The initial challenge is simply what to label it at the first visit.

“I have no problem with term ‘androgenetic alopecia,’ since that is what women are seeing when they first look on the Internet for information. But I do try to transition them to ‘female pattern hair loss.’ And I never – ever – use the term ‘male pattern baldness.’ It has a huge impact on women.”

The disease is a progressive miniaturization of the hair follicle over time. The growing cycle slows and the resting phase lengthens. There is progressive thinning over the vertex. Some women may keep most of their frontal hairline, but the vast majority do say it’s thinner than it was.

Spironolactone and oral contraceptives with spironolactone analogues are Dr. Torgerson’s go-to medications for first-line treatment. For spironolactone, she prefers a dose of 100-200 mg/day. Some women experience gastrointestinal upset, dizziness, cramps, breast tenderness, and spotting with these medications.

Her choice for an oral contraceptive is the combination of 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol plus drospirenone, but any oral contraceptive approved for acne may work.

Finasteride and dutasteride are approved for pattern hair loss in men, but not in women. Both inhibit 5 alpha-reductase type II. Dutasteride is more potent that finasteride and also inhibits type 1 alpha-reductase; both of these enzymes convert testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The side-effect profile is more moderate than that of spironolactone, but both of the drugs have had mixed results in clinical trials.

One problem with the finasteride trials has been the variation in dosing. The least positive studies used the lowest dose of 1.25 mg. As the dosage increased to 2.5 mg and 5 mg, the benefit increased.

Despite her support for hormonal therapies, Dr. Torgerson doesn’t rely upon them alone – she supports them with the direct action of a 5% minoxidil foam. In addition to prescribing effective therapy, she urges women to actually be patient and to have realistic expectations.

Most women expect dramatic improvement in a short time. “I have no idea where that expectation comes from. This is a slow progressive condition. I agree with them that it’s completely unsexy to have the head of hair they do at that time. But if, in 3 years, they have this same head of hair, that’s going to be an amazing success. And once they have that expectation in their mind, they are usually happy with any other results that they see.”

Dr. Torgerson had no financial conflicts with regard to her presentation.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2015

Early intervention may forestall menopause-related skin aging

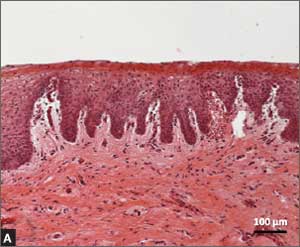

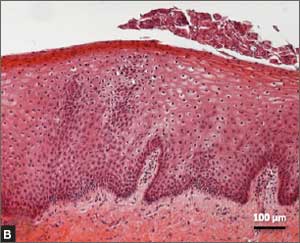

NEW YORK – Evidence is mounting that early intervention in the menopausal transition could help forestall some of the skin aging associated with estrogen decline.

Estrogen supplementation and collagen stimulation both seem effective in preserving the integrity of a woman’s skin as levels of the hormone decrease, Dr. Diane Madfes said at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

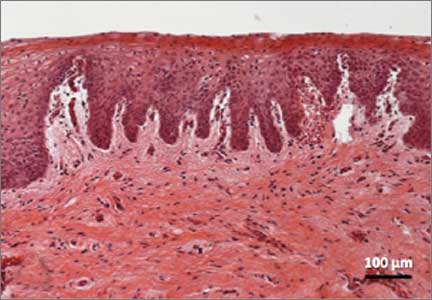

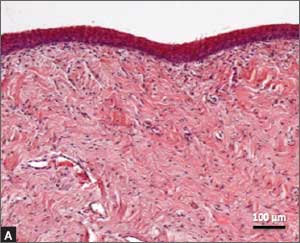

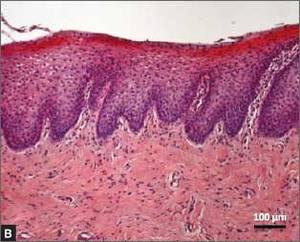

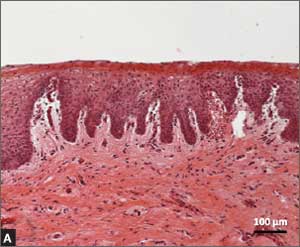

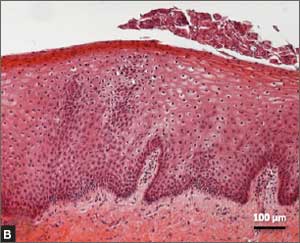

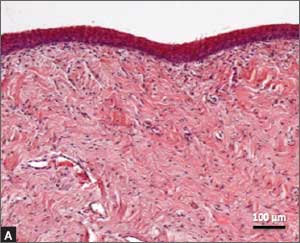

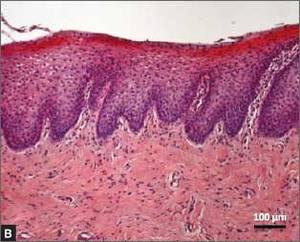

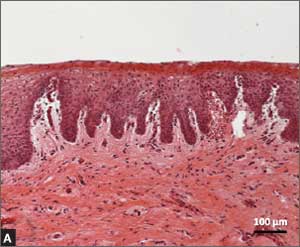

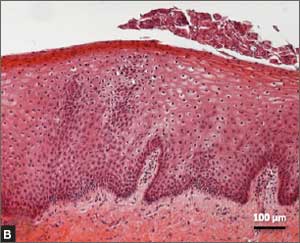

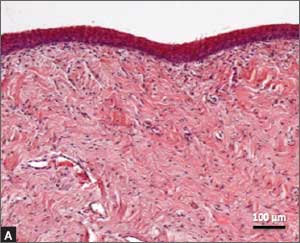

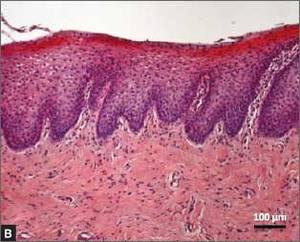

Type 3 collagen decreases by up to 50% within a few years of menopause, said Dr. Madfes, a dermatologist in New York. This is directly related to a loss of estrogen receptor beta in the dermal matrix, which promotes collagen formation.

“There is a theory – the timing hypothesis – that we have a window of opportunity to intervene. If we can stimulate the collagen before the receptors go down, maybe we can have a beneficial effect on skin.”

Any method of collagen stimulation should work, she said: laser resurfacing, microneedling, or radiofrequency. “We are very good about being able to stimulate collagen. The method doesn’t matter as much as the timing. The important thing is to intervene early. If you see your patients starting to sag, see a loss of elasticity, that is the time to intervene. Get at the collagen while it’s still receptive.”

Estrogen exerts a plethora of antiaging, skin-preserving effects. “We know that a decrease in estrogen is related to telomere shortening. Estrogen protects against oxidative damage. It signals keratinocytes through IGF-1,” she said.

The hormone also protects skin’s water-binding qualities by promoting mucopolysaccharides, sebum production, barrier function, and hyaluronic acid. It may even play a role in protecting against ultraviolet light. Estrogen downregulation affects healing by inhibiting the proliferation of keratinocytes and the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts.

All these add up to rapid skin aging after estrogen levels drop.

“The visible effects of aging on women’s skin are not so much related to her chronological age as to the years after menopause,” Dr. Madfes said – a finding that is particularly illustrated in young women with surgical menopause and those with breast cancer who take tamoxifen. The observation seems to suggest that early intervention with estrogen might help prevent at least some of the signs of aging.