User login

Managing menopause symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

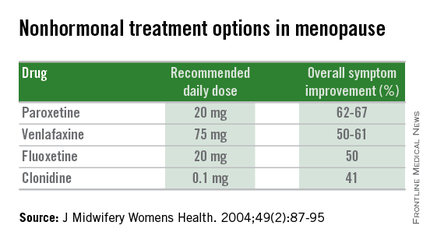

Nonhormonal therapies

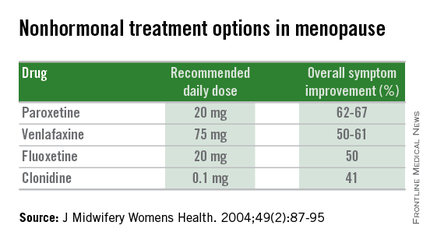

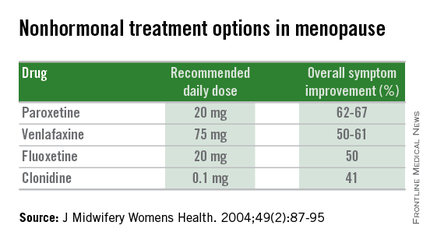

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

Denosumab better at building bone than zoledronic acid

SAN FRANCISCO – Denosumab was superior to zoledronic acid (ZA) in building bone at the lumber spine, total hip, and femoral neck in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis previously treated with oral bisphosphonate therapy in a randomized phase III trial. This study is one more piece of level I evidence to support the effectiveness of transitioning to denosumab in such patients.

“In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis on prior oral bisphosphonates for 2 or more years, transitioning to denosumab resulted in significantly greater increases in bone mineral density [BMD], compared with zoledronic acid at all measured skeletal sites,” said lead author Dr. Paul D. Miller of the Colorado Center for Bone Research, Lakewood, Colo.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Dr. Miller said: “This study completes a suite of trials that show transitioning from oral bisphosphonates to denosumab provides greater increases in bone mineral density and reduction in bone turnover markers, compared to maintaining therapy with another bisphosphonate.”

“Adherence rates to oral bisphosphonates are low,” he continued. “Patients who are intolerant to or fail other bisphosphonates may cycle from one bisphosphonate to another, but clinical benefits are not shown. Previous trials have shown that denosumab increased bone mineral density in women previously treated with oral bisphosphonates, whereas zoledronic acid did not, in women previously treated with alendronate.”

A prospective, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial was mounted to compare denosumab given subcutaneously at 60 mg every 6 months (n = 321) vs. ZA 5 mg once a year (n = 322) in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who were intolerant to or who failed oral bisphosphonate therapy after at least 2 years of treatment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between both treatment arms. Median age was 69 years. About 38% had previous osteoporotic fracture. Bone mineral density T scores were similar between groups. Prior oral bisphosphonate exposure was a median of 6.4 years. Bone turnover marker levels were similar between the two arms.

For the primary endpoint, at 12 months, denosumab achieved a greater increase in BMD at all sites, compared with ZA: a 2.1% difference was observed at the lumbar spine and a 1.4% difference at the total hip.

Changes in bone turnover markers over time were more favorable with denosumab, he continued. Serum C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide (CTX) level was maintained in the denosumab arm and increased with ZA over 12 months. A similar pattern was observed with procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP).

Adverse events were comparable between both groups. Serious adverse events were reported in 7.8% in the denosumab arm versus 9.1% in the ZA arm, but this difference was not statistically significant. Slightly more hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in the denosumab group: 3.8% versus 1.9% for ZA. The number of osteoporotic-related fractures was doubled in the ZA arm: 7 for denosumab vs. 15 for ZA.

Dr. Miller told listeners that this is the fourth study to show that denosumab is effective in osteoporotic patients previously on oral bisphosphonates, including prior risedronate, ibandronate, and alendronate.

SAN FRANCISCO – Denosumab was superior to zoledronic acid (ZA) in building bone at the lumber spine, total hip, and femoral neck in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis previously treated with oral bisphosphonate therapy in a randomized phase III trial. This study is one more piece of level I evidence to support the effectiveness of transitioning to denosumab in such patients.

“In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis on prior oral bisphosphonates for 2 or more years, transitioning to denosumab resulted in significantly greater increases in bone mineral density [BMD], compared with zoledronic acid at all measured skeletal sites,” said lead author Dr. Paul D. Miller of the Colorado Center for Bone Research, Lakewood, Colo.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Dr. Miller said: “This study completes a suite of trials that show transitioning from oral bisphosphonates to denosumab provides greater increases in bone mineral density and reduction in bone turnover markers, compared to maintaining therapy with another bisphosphonate.”

“Adherence rates to oral bisphosphonates are low,” he continued. “Patients who are intolerant to or fail other bisphosphonates may cycle from one bisphosphonate to another, but clinical benefits are not shown. Previous trials have shown that denosumab increased bone mineral density in women previously treated with oral bisphosphonates, whereas zoledronic acid did not, in women previously treated with alendronate.”

A prospective, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial was mounted to compare denosumab given subcutaneously at 60 mg every 6 months (n = 321) vs. ZA 5 mg once a year (n = 322) in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who were intolerant to or who failed oral bisphosphonate therapy after at least 2 years of treatment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between both treatment arms. Median age was 69 years. About 38% had previous osteoporotic fracture. Bone mineral density T scores were similar between groups. Prior oral bisphosphonate exposure was a median of 6.4 years. Bone turnover marker levels were similar between the two arms.

For the primary endpoint, at 12 months, denosumab achieved a greater increase in BMD at all sites, compared with ZA: a 2.1% difference was observed at the lumbar spine and a 1.4% difference at the total hip.

Changes in bone turnover markers over time were more favorable with denosumab, he continued. Serum C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide (CTX) level was maintained in the denosumab arm and increased with ZA over 12 months. A similar pattern was observed with procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP).

Adverse events were comparable between both groups. Serious adverse events were reported in 7.8% in the denosumab arm versus 9.1% in the ZA arm, but this difference was not statistically significant. Slightly more hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in the denosumab group: 3.8% versus 1.9% for ZA. The number of osteoporotic-related fractures was doubled in the ZA arm: 7 for denosumab vs. 15 for ZA.

Dr. Miller told listeners that this is the fourth study to show that denosumab is effective in osteoporotic patients previously on oral bisphosphonates, including prior risedronate, ibandronate, and alendronate.

SAN FRANCISCO – Denosumab was superior to zoledronic acid (ZA) in building bone at the lumber spine, total hip, and femoral neck in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis previously treated with oral bisphosphonate therapy in a randomized phase III trial. This study is one more piece of level I evidence to support the effectiveness of transitioning to denosumab in such patients.

“In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis on prior oral bisphosphonates for 2 or more years, transitioning to denosumab resulted in significantly greater increases in bone mineral density [BMD], compared with zoledronic acid at all measured skeletal sites,” said lead author Dr. Paul D. Miller of the Colorado Center for Bone Research, Lakewood, Colo.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Dr. Miller said: “This study completes a suite of trials that show transitioning from oral bisphosphonates to denosumab provides greater increases in bone mineral density and reduction in bone turnover markers, compared to maintaining therapy with another bisphosphonate.”

“Adherence rates to oral bisphosphonates are low,” he continued. “Patients who are intolerant to or fail other bisphosphonates may cycle from one bisphosphonate to another, but clinical benefits are not shown. Previous trials have shown that denosumab increased bone mineral density in women previously treated with oral bisphosphonates, whereas zoledronic acid did not, in women previously treated with alendronate.”

A prospective, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial was mounted to compare denosumab given subcutaneously at 60 mg every 6 months (n = 321) vs. ZA 5 mg once a year (n = 322) in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who were intolerant to or who failed oral bisphosphonate therapy after at least 2 years of treatment.

Baseline characteristics were similar between both treatment arms. Median age was 69 years. About 38% had previous osteoporotic fracture. Bone mineral density T scores were similar between groups. Prior oral bisphosphonate exposure was a median of 6.4 years. Bone turnover marker levels were similar between the two arms.

For the primary endpoint, at 12 months, denosumab achieved a greater increase in BMD at all sites, compared with ZA: a 2.1% difference was observed at the lumbar spine and a 1.4% difference at the total hip.

Changes in bone turnover markers over time were more favorable with denosumab, he continued. Serum C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide (CTX) level was maintained in the denosumab arm and increased with ZA over 12 months. A similar pattern was observed with procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP).

Adverse events were comparable between both groups. Serious adverse events were reported in 7.8% in the denosumab arm versus 9.1% in the ZA arm, but this difference was not statistically significant. Slightly more hypersensitivity adverse events were reported in the denosumab group: 3.8% versus 1.9% for ZA. The number of osteoporotic-related fractures was doubled in the ZA arm: 7 for denosumab vs. 15 for ZA.

Dr. Miller told listeners that this is the fourth study to show that denosumab is effective in osteoporotic patients previously on oral bisphosphonates, including prior risedronate, ibandronate, and alendronate.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Denosumab was superior to zoledronic acid in building bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who had previously been treated with oral bisphosphonates.

Major finding: Denosumab achieved a 2.1% difference in BMD at the lumbar spine and a 1.4% difference at the hip, compared with zoledronic acid.

Data source: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial that included 643 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Miller’s financial disclosures include Alexion, Amgen, Merck, Merck Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Regeneron, National Bone Health Alliance, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Radius, and he is owner and director of the Colorado Center for Bone Research. The study was supported by Amgen.

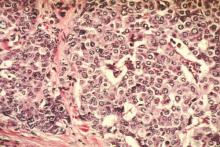

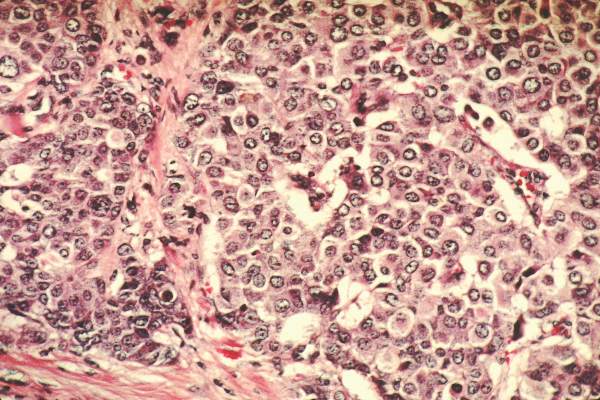

Menopause status could guide breast cancer screening interval

Among postmenopausal women, breast cancers diagnosed following biennial mammography intervals are no more “unfavorable” than those diagnosed following annual intervals, according to a report published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“When considering recommendations regarding screening intervals, the potential benefit of diagnosing cancers at an earlier stage must be weighed against the increased potential for harms associated with more frequent screening, such as false-positive recalls and biopsies, which are 1.5 to 2 times higher in annual vs. biennial screeners,” wrote Diana L. Miglioretti, Ph.D., of the University of California, Davis, and her associates in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC).

The optimal frequency of mammographic screening remains controversial. The American Cancer Society commissioned the BCSC to analyze the most recent information on this issue as part of its effort to update the ACS guideline for breast cancer screening for women at average risk.

BCSC registries collect patient and clinical data from community radiology facilities across the country. For this analysis, Dr. Miglioretti and her colleagues focused on 15,440 women aged 40-85 years in these registries who were diagnosed as having breast cancer from 1996 to 2012. A total of 12,070 of the women underwent annual mammographic screening and 3,370 underwent biennial mammographic screening.

Among premenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (relative risk, 1.11). In contrast, among postmenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were not more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (RR, 1.03), the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3084).

In an editorial accompanying this report, Dr. Wendy Y. Chen of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Harvard Medical School, all in Boston, wrote, “Although the authors do not endorse annual or biennial screening, they imply that biennial screening would be acceptable for postmenopausal women but inferior for premenopausal women.”

Most developed countries outside the United States – including the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia – recommend screening every 2 or 3 years, Dr. Chen noted (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3286).

This study and others clearly show that, with less frequent mammography, breast cancers will be larger and have a slightly more advanced stage when they are discovered, Dr. Chen wrote. But with a better understanding of tumor biology and improvements in targeted therapy, the best approach may not be simply trying to identify a smaller tumor, she added.

“Efforts should be focused on a better understanding of how screening interacts with tumor biology with a better understanding of the types of interval cancers and sojourn times and how these characteristics differ by age and/or menopausal status,” Dr. Chen wrote.

This study was supported by the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Miglioretti reported having no relevant financial disclosures. One of the investigators reported being an unpaid advisor on General Electric Health Care’s breast medical advisory board.

Among postmenopausal women, breast cancers diagnosed following biennial mammography intervals are no more “unfavorable” than those diagnosed following annual intervals, according to a report published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“When considering recommendations regarding screening intervals, the potential benefit of diagnosing cancers at an earlier stage must be weighed against the increased potential for harms associated with more frequent screening, such as false-positive recalls and biopsies, which are 1.5 to 2 times higher in annual vs. biennial screeners,” wrote Diana L. Miglioretti, Ph.D., of the University of California, Davis, and her associates in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC).

The optimal frequency of mammographic screening remains controversial. The American Cancer Society commissioned the BCSC to analyze the most recent information on this issue as part of its effort to update the ACS guideline for breast cancer screening for women at average risk.

BCSC registries collect patient and clinical data from community radiology facilities across the country. For this analysis, Dr. Miglioretti and her colleagues focused on 15,440 women aged 40-85 years in these registries who were diagnosed as having breast cancer from 1996 to 2012. A total of 12,070 of the women underwent annual mammographic screening and 3,370 underwent biennial mammographic screening.

Among premenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (relative risk, 1.11). In contrast, among postmenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were not more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (RR, 1.03), the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3084).

In an editorial accompanying this report, Dr. Wendy Y. Chen of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Harvard Medical School, all in Boston, wrote, “Although the authors do not endorse annual or biennial screening, they imply that biennial screening would be acceptable for postmenopausal women but inferior for premenopausal women.”

Most developed countries outside the United States – including the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia – recommend screening every 2 or 3 years, Dr. Chen noted (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3286).

This study and others clearly show that, with less frequent mammography, breast cancers will be larger and have a slightly more advanced stage when they are discovered, Dr. Chen wrote. But with a better understanding of tumor biology and improvements in targeted therapy, the best approach may not be simply trying to identify a smaller tumor, she added.

“Efforts should be focused on a better understanding of how screening interacts with tumor biology with a better understanding of the types of interval cancers and sojourn times and how these characteristics differ by age and/or menopausal status,” Dr. Chen wrote.

This study was supported by the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Miglioretti reported having no relevant financial disclosures. One of the investigators reported being an unpaid advisor on General Electric Health Care’s breast medical advisory board.

Among postmenopausal women, breast cancers diagnosed following biennial mammography intervals are no more “unfavorable” than those diagnosed following annual intervals, according to a report published online Oct. 20 in JAMA Oncology.

“When considering recommendations regarding screening intervals, the potential benefit of diagnosing cancers at an earlier stage must be weighed against the increased potential for harms associated with more frequent screening, such as false-positive recalls and biopsies, which are 1.5 to 2 times higher in annual vs. biennial screeners,” wrote Diana L. Miglioretti, Ph.D., of the University of California, Davis, and her associates in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC).

The optimal frequency of mammographic screening remains controversial. The American Cancer Society commissioned the BCSC to analyze the most recent information on this issue as part of its effort to update the ACS guideline for breast cancer screening for women at average risk.

BCSC registries collect patient and clinical data from community radiology facilities across the country. For this analysis, Dr. Miglioretti and her colleagues focused on 15,440 women aged 40-85 years in these registries who were diagnosed as having breast cancer from 1996 to 2012. A total of 12,070 of the women underwent annual mammographic screening and 3,370 underwent biennial mammographic screening.

Among premenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (relative risk, 1.11). In contrast, among postmenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were not more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (RR, 1.03), the investigators wrote (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3084).

In an editorial accompanying this report, Dr. Wendy Y. Chen of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Harvard Medical School, all in Boston, wrote, “Although the authors do not endorse annual or biennial screening, they imply that biennial screening would be acceptable for postmenopausal women but inferior for premenopausal women.”

Most developed countries outside the United States – including the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia – recommend screening every 2 or 3 years, Dr. Chen noted (JAMA Oncol. 2015 Oct 20 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncology.2015.3286).

This study and others clearly show that, with less frequent mammography, breast cancers will be larger and have a slightly more advanced stage when they are discovered, Dr. Chen wrote. But with a better understanding of tumor biology and improvements in targeted therapy, the best approach may not be simply trying to identify a smaller tumor, she added.

“Efforts should be focused on a better understanding of how screening interacts with tumor biology with a better understanding of the types of interval cancers and sojourn times and how these characteristics differ by age and/or menopausal status,” Dr. Chen wrote.

This study was supported by the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Miglioretti reported having no relevant financial disclosures. One of the investigators reported being an unpaid advisor on General Electric Health Care’s breast medical advisory board.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: After menopause, breast cancers diagnosed after 2-year mammography intervals are no more unfavorable than those arising after 1-year intervals.

Major finding: Among postmenopausal women, those diagnosed after biennial mammograms were not more likely to have tumors with unfavorable prognostic characteristics than were those diagnosed after annual mammograms (relative risk, 1.03).

Data source: A prospective cohort study involving 15,440 women diagnosed with breast cancer from 1996 to 2012.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Miglioretti reported having no relevant financial disclosures. One of the investigators reported being an unpaid advisor on General Electric Health Care’s breast medical advisory board.

What’s in the pipeline for female sexual problems?

LAS VEGAS – Female desire and sexual function involve a complicated and interconnected cascade of hormones and neurotransmitters, each providing a potential target for modulation in cases of low desire or sexual dysfunction.

There are some pharmacologic options available now and more drugs in the pipeline, Dr. Roya Rezaee said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Dr. Rezaee, codirector of the Program for Sexual Health and Vulvovaginal Disorders at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, explained how each treatment acts in the chemical cascade of desire and sexual response.* Though much remains unknown, researchers have identified neurochemical pathways of desire and arousal that act on the brain stem, the hypothalamus, and the amygdala.

Among the neurotransmitters and neurohormones thought to promote female sexual function, dopamine and melanocortin are associated with attention and desire, while norepinephrine and oxytocin are more directly related to arousal. Estrogen and testosterone function as excitatory neurohormones. Serotonin, because it is associated with satiety, may be inhibitory, as are prolactin and the endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids.

In the peripheral tissues, the presence of sex hormones maintains general genital function. For example, estradiol not only promotes vaginal lubrication, but also helps maintain adequate blood flow to the vagina and clitoris. Exogenous testosterone can directly influence the amount of unbound estrogen as well as testosterone, said Dr. Rezaee. Higher testosterone levels downregulate sex hormone–binding globulin, increasing circulating levels of free estrogen and testosterone.

“For women, low testosterone does not always correlate with low desire, but testosterone administration has been shown to be efficacious for low desire,” Dr. Rezaee said. “People are still writing prescriptions for testosterone off label, because a lot of us believe in the data,” she said, adding that a 2009 Cochrane review showed a good safety profile for testosterone.

Targeting dopaminergic pathways to increase desire, an extended-release daily oral combination of trazodone and bupropion, to be marketed as Lorexys, is about to begin phase III clinical trials. Bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been known to have prosexual side effects, Dr. Rezaee said. Both ingredients in Lorexys are currently approved as antidepressants.

Increasing available norepinephrine may help with focus and attention, and increase subjective sexual excitement. However, the ADHD and antidepressant medications that increase norepinephrine carry significant side effects and should not be what physicians use to help their patients with low desire, Dr. Rezaee said.

“Serotonin may have a role in low desire by acting as a sexual satiety signal, and SSRIs are serotonergic agents that inhibit desire, arousal, and orgasm in the brain and in the tissue,” she said.

However, there are seven known families of serotonin receptors, and selective modulation specifically of the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A and 5-HT2A receptors may have prosexual effects. The newly approved medication flibanserin (Addyi) is a selective agonist for 5-HT1A and an antagonist for 5-HT2A receptors. Flibanserin is also thought to produce upregulation in dopamine and norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex, combating the satiety signals from serotonin and leading to increased desire.

Other medications that are 5-HT1A agonists with potential prosexual effects include buspirone (Buspar) and trazodone (Desyrel, Oleptro).

Blockade of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) permits relaxation of smooth muscles in arterial walls and increases blood flow to erectile tissues. PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra) may be of benefit to some women as well, said Dr. Rezaee, though they do not address low desire.

“Newer data support the use of PDE5 inhibitors with women who suffer from SSRI-induced orgasmic complaints of increased latency or decreased intensity, or anorgasmia,” she said. A dose of 25-50 mg of sildenafil 1 hour before sexual activity may help these patients, she advised.

Phase II trials have been completed for two other combination drugs to treat female sexual problems. Lybrido is a combination of testosterone and sildenafil, while Lybridos combines testosterone with buspirone. Both products are oral tablets, taken on demand.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class drug in development as a melanocortin agonist. This drug, meant to be used on demand to activate an endogenous pathway that increases attention and desire, is in phase III clinical trials.

Dr. Rezaee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

*Correction, 10/20/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Rezaee's title.

LAS VEGAS – Female desire and sexual function involve a complicated and interconnected cascade of hormones and neurotransmitters, each providing a potential target for modulation in cases of low desire or sexual dysfunction.

There are some pharmacologic options available now and more drugs in the pipeline, Dr. Roya Rezaee said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Dr. Rezaee, codirector of the Program for Sexual Health and Vulvovaginal Disorders at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, explained how each treatment acts in the chemical cascade of desire and sexual response.* Though much remains unknown, researchers have identified neurochemical pathways of desire and arousal that act on the brain stem, the hypothalamus, and the amygdala.

Among the neurotransmitters and neurohormones thought to promote female sexual function, dopamine and melanocortin are associated with attention and desire, while norepinephrine and oxytocin are more directly related to arousal. Estrogen and testosterone function as excitatory neurohormones. Serotonin, because it is associated with satiety, may be inhibitory, as are prolactin and the endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids.

In the peripheral tissues, the presence of sex hormones maintains general genital function. For example, estradiol not only promotes vaginal lubrication, but also helps maintain adequate blood flow to the vagina and clitoris. Exogenous testosterone can directly influence the amount of unbound estrogen as well as testosterone, said Dr. Rezaee. Higher testosterone levels downregulate sex hormone–binding globulin, increasing circulating levels of free estrogen and testosterone.

“For women, low testosterone does not always correlate with low desire, but testosterone administration has been shown to be efficacious for low desire,” Dr. Rezaee said. “People are still writing prescriptions for testosterone off label, because a lot of us believe in the data,” she said, adding that a 2009 Cochrane review showed a good safety profile for testosterone.

Targeting dopaminergic pathways to increase desire, an extended-release daily oral combination of trazodone and bupropion, to be marketed as Lorexys, is about to begin phase III clinical trials. Bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been known to have prosexual side effects, Dr. Rezaee said. Both ingredients in Lorexys are currently approved as antidepressants.

Increasing available norepinephrine may help with focus and attention, and increase subjective sexual excitement. However, the ADHD and antidepressant medications that increase norepinephrine carry significant side effects and should not be what physicians use to help their patients with low desire, Dr. Rezaee said.

“Serotonin may have a role in low desire by acting as a sexual satiety signal, and SSRIs are serotonergic agents that inhibit desire, arousal, and orgasm in the brain and in the tissue,” she said.

However, there are seven known families of serotonin receptors, and selective modulation specifically of the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A and 5-HT2A receptors may have prosexual effects. The newly approved medication flibanserin (Addyi) is a selective agonist for 5-HT1A and an antagonist for 5-HT2A receptors. Flibanserin is also thought to produce upregulation in dopamine and norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex, combating the satiety signals from serotonin and leading to increased desire.

Other medications that are 5-HT1A agonists with potential prosexual effects include buspirone (Buspar) and trazodone (Desyrel, Oleptro).

Blockade of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) permits relaxation of smooth muscles in arterial walls and increases blood flow to erectile tissues. PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra) may be of benefit to some women as well, said Dr. Rezaee, though they do not address low desire.

“Newer data support the use of PDE5 inhibitors with women who suffer from SSRI-induced orgasmic complaints of increased latency or decreased intensity, or anorgasmia,” she said. A dose of 25-50 mg of sildenafil 1 hour before sexual activity may help these patients, she advised.

Phase II trials have been completed for two other combination drugs to treat female sexual problems. Lybrido is a combination of testosterone and sildenafil, while Lybridos combines testosterone with buspirone. Both products are oral tablets, taken on demand.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class drug in development as a melanocortin agonist. This drug, meant to be used on demand to activate an endogenous pathway that increases attention and desire, is in phase III clinical trials.

Dr. Rezaee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

*Correction, 10/20/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Rezaee's title.

LAS VEGAS – Female desire and sexual function involve a complicated and interconnected cascade of hormones and neurotransmitters, each providing a potential target for modulation in cases of low desire or sexual dysfunction.

There are some pharmacologic options available now and more drugs in the pipeline, Dr. Roya Rezaee said at the NAMS 2015 annual meeting.

Dr. Rezaee, codirector of the Program for Sexual Health and Vulvovaginal Disorders at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, explained how each treatment acts in the chemical cascade of desire and sexual response.* Though much remains unknown, researchers have identified neurochemical pathways of desire and arousal that act on the brain stem, the hypothalamus, and the amygdala.

Among the neurotransmitters and neurohormones thought to promote female sexual function, dopamine and melanocortin are associated with attention and desire, while norepinephrine and oxytocin are more directly related to arousal. Estrogen and testosterone function as excitatory neurohormones. Serotonin, because it is associated with satiety, may be inhibitory, as are prolactin and the endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids.

In the peripheral tissues, the presence of sex hormones maintains general genital function. For example, estradiol not only promotes vaginal lubrication, but also helps maintain adequate blood flow to the vagina and clitoris. Exogenous testosterone can directly influence the amount of unbound estrogen as well as testosterone, said Dr. Rezaee. Higher testosterone levels downregulate sex hormone–binding globulin, increasing circulating levels of free estrogen and testosterone.

“For women, low testosterone does not always correlate with low desire, but testosterone administration has been shown to be efficacious for low desire,” Dr. Rezaee said. “People are still writing prescriptions for testosterone off label, because a lot of us believe in the data,” she said, adding that a 2009 Cochrane review showed a good safety profile for testosterone.

Targeting dopaminergic pathways to increase desire, an extended-release daily oral combination of trazodone and bupropion, to be marketed as Lorexys, is about to begin phase III clinical trials. Bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been known to have prosexual side effects, Dr. Rezaee said. Both ingredients in Lorexys are currently approved as antidepressants.

Increasing available norepinephrine may help with focus and attention, and increase subjective sexual excitement. However, the ADHD and antidepressant medications that increase norepinephrine carry significant side effects and should not be what physicians use to help their patients with low desire, Dr. Rezaee said.

“Serotonin may have a role in low desire by acting as a sexual satiety signal, and SSRIs are serotonergic agents that inhibit desire, arousal, and orgasm in the brain and in the tissue,” she said.

However, there are seven known families of serotonin receptors, and selective modulation specifically of the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A and 5-HT2A receptors may have prosexual effects. The newly approved medication flibanserin (Addyi) is a selective agonist for 5-HT1A and an antagonist for 5-HT2A receptors. Flibanserin is also thought to produce upregulation in dopamine and norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex, combating the satiety signals from serotonin and leading to increased desire.

Other medications that are 5-HT1A agonists with potential prosexual effects include buspirone (Buspar) and trazodone (Desyrel, Oleptro).

Blockade of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) permits relaxation of smooth muscles in arterial walls and increases blood flow to erectile tissues. PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil (Viagra) may be of benefit to some women as well, said Dr. Rezaee, though they do not address low desire.

“Newer data support the use of PDE5 inhibitors with women who suffer from SSRI-induced orgasmic complaints of increased latency or decreased intensity, or anorgasmia,” she said. A dose of 25-50 mg of sildenafil 1 hour before sexual activity may help these patients, she advised.

Phase II trials have been completed for two other combination drugs to treat female sexual problems. Lybrido is a combination of testosterone and sildenafil, while Lybridos combines testosterone with buspirone. Both products are oral tablets, taken on demand.

Bremelanotide is a first-in-class drug in development as a melanocortin agonist. This drug, meant to be used on demand to activate an endogenous pathway that increases attention and desire, is in phase III clinical trials.

Dr. Rezaee reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

*Correction, 10/20/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Rezaee's title.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NAMS 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

Midlife contraception strategy should include transition to menopause

LAS VEGAS – Though fertility declines precipitously as menopause nears, women in midlife may still conceive. Clinicians and patients need guidance to develop a rational plan for contraceptive management and a clear path to transition to menopausal symptom management, said Dr. Petra Casey at the NAMS 2015 Annual Meeting.

Dr. Casey, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that the rate of infertility approaches, but does not reach, 100% by age 50, so women need a game plan to take them through the end of their fertile years. These needs are not always met, she said, noting that 75% of pregnancies in women over the age of 40 are unintended.

The rate of spontaneous abortion may exceed 50% by age 45, and chronic diabetes and hypertension are more likely to result after pregnancies in older women. The substantial increase in risk for undesirable outcomes means that an unexpected pregnancy in midlife may cause considerable distress.

No contraceptive method is contraindicated by a patient’s age alone, said Dr. Casey, though it may be wise to reserve combined hormonal contraception (CHC) for women without cardiovascular disease and thrombotic risk. Reminding the audience that risk stratification for CHC for those over 40 years of age is category 2, meaning that benefits generally outweigh the risks, Dr. Casey said, “ ‘What? So a 55-year-old can use combined hormonal contraception?’ Yes!”

Patients may also wish to consider a progestin-only contraception method, a choice that provides endometrial protection. This option allows the judicious addition of estrogen by the most appropriate method to manage symptoms. Choices include a contraceptive implant, a progestin-only pill, or a levonorgestrel-emitting intrauterine device. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) may be less desirable because of the theoretical risk of bone loss, said Dr. Casey.

Transdermal estrogen delivery is preferred for menopausal doses of estrogen, according to the North American Menopause Society’s guidance for clinical care for midlife. If perimenopausal women are having cyclic vasomotor symptoms or headaches associated with estrogen nadir, transdermal estrogen therapy can be used during the menstrual week. With this option, a higher-dose patch of 0.1 mg will work better to replace endogenous estrogen.

For women who desire nonhormonal contraceptive and menopausal symptom management, a copper IUD, barrier contraception, or sterilization of the patient or her partner can be used in combination with a nonhormonal medication to manage vasomotor symptoms. Though the only Food and Drug Administration–approved nonhormonal option is paroxetine (Paxil) 7.5 mg/day, a variety of choices have been found effective in clinical trials. These include citalopram (Celexa) and escitalopram (Lexapro), venlafaxine (Effexor), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), gabapentin (Neurontin), and pregabalin (Lyrica).

Contraception should be continued until the patient has experienced 12 months of continuous amenorrhea if over the age of 50 years, or 2 years of amenorrhea if she is younger than 50 years, said Dr. Casey. A predictive model for onset of menopause has been developed that takes age, smoking, bleeding patterns, and estrogen and follicle-stimulating hormone levels into account, but “further study is needed before applying this model clinically,” said Dr. Casey. The decision about when to discontinue contraception also depends on the impact it will have on the particular couple. “Shared decision making is of the utmost importance,” she said.

Dr. Casey disclosed that she is a certified Nexplanon trainer and has received research grant support from Merck.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Though fertility declines precipitously as menopause nears, women in midlife may still conceive. Clinicians and patients need guidance to develop a rational plan for contraceptive management and a clear path to transition to menopausal symptom management, said Dr. Petra Casey at the NAMS 2015 Annual Meeting.

Dr. Casey, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that the rate of infertility approaches, but does not reach, 100% by age 50, so women need a game plan to take them through the end of their fertile years. These needs are not always met, she said, noting that 75% of pregnancies in women over the age of 40 are unintended.

The rate of spontaneous abortion may exceed 50% by age 45, and chronic diabetes and hypertension are more likely to result after pregnancies in older women. The substantial increase in risk for undesirable outcomes means that an unexpected pregnancy in midlife may cause considerable distress.

No contraceptive method is contraindicated by a patient’s age alone, said Dr. Casey, though it may be wise to reserve combined hormonal contraception (CHC) for women without cardiovascular disease and thrombotic risk. Reminding the audience that risk stratification for CHC for those over 40 years of age is category 2, meaning that benefits generally outweigh the risks, Dr. Casey said, “ ‘What? So a 55-year-old can use combined hormonal contraception?’ Yes!”

Patients may also wish to consider a progestin-only contraception method, a choice that provides endometrial protection. This option allows the judicious addition of estrogen by the most appropriate method to manage symptoms. Choices include a contraceptive implant, a progestin-only pill, or a levonorgestrel-emitting intrauterine device. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) may be less desirable because of the theoretical risk of bone loss, said Dr. Casey.

Transdermal estrogen delivery is preferred for menopausal doses of estrogen, according to the North American Menopause Society’s guidance for clinical care for midlife. If perimenopausal women are having cyclic vasomotor symptoms or headaches associated with estrogen nadir, transdermal estrogen therapy can be used during the menstrual week. With this option, a higher-dose patch of 0.1 mg will work better to replace endogenous estrogen.

For women who desire nonhormonal contraceptive and menopausal symptom management, a copper IUD, barrier contraception, or sterilization of the patient or her partner can be used in combination with a nonhormonal medication to manage vasomotor symptoms. Though the only Food and Drug Administration–approved nonhormonal option is paroxetine (Paxil) 7.5 mg/day, a variety of choices have been found effective in clinical trials. These include citalopram (Celexa) and escitalopram (Lexapro), venlafaxine (Effexor), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), gabapentin (Neurontin), and pregabalin (Lyrica).

Contraception should be continued until the patient has experienced 12 months of continuous amenorrhea if over the age of 50 years, or 2 years of amenorrhea if she is younger than 50 years, said Dr. Casey. A predictive model for onset of menopause has been developed that takes age, smoking, bleeding patterns, and estrogen and follicle-stimulating hormone levels into account, but “further study is needed before applying this model clinically,” said Dr. Casey. The decision about when to discontinue contraception also depends on the impact it will have on the particular couple. “Shared decision making is of the utmost importance,” she said.

Dr. Casey disclosed that she is a certified Nexplanon trainer and has received research grant support from Merck.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Though fertility declines precipitously as menopause nears, women in midlife may still conceive. Clinicians and patients need guidance to develop a rational plan for contraceptive management and a clear path to transition to menopausal symptom management, said Dr. Petra Casey at the NAMS 2015 Annual Meeting.

Dr. Casey, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that the rate of infertility approaches, but does not reach, 100% by age 50, so women need a game plan to take them through the end of their fertile years. These needs are not always met, she said, noting that 75% of pregnancies in women over the age of 40 are unintended.

The rate of spontaneous abortion may exceed 50% by age 45, and chronic diabetes and hypertension are more likely to result after pregnancies in older women. The substantial increase in risk for undesirable outcomes means that an unexpected pregnancy in midlife may cause considerable distress.

No contraceptive method is contraindicated by a patient’s age alone, said Dr. Casey, though it may be wise to reserve combined hormonal contraception (CHC) for women without cardiovascular disease and thrombotic risk. Reminding the audience that risk stratification for CHC for those over 40 years of age is category 2, meaning that benefits generally outweigh the risks, Dr. Casey said, “ ‘What? So a 55-year-old can use combined hormonal contraception?’ Yes!”

Patients may also wish to consider a progestin-only contraception method, a choice that provides endometrial protection. This option allows the judicious addition of estrogen by the most appropriate method to manage symptoms. Choices include a contraceptive implant, a progestin-only pill, or a levonorgestrel-emitting intrauterine device. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) may be less desirable because of the theoretical risk of bone loss, said Dr. Casey.

Transdermal estrogen delivery is preferred for menopausal doses of estrogen, according to the North American Menopause Society’s guidance for clinical care for midlife. If perimenopausal women are having cyclic vasomotor symptoms or headaches associated with estrogen nadir, transdermal estrogen therapy can be used during the menstrual week. With this option, a higher-dose patch of 0.1 mg will work better to replace endogenous estrogen.

For women who desire nonhormonal contraceptive and menopausal symptom management, a copper IUD, barrier contraception, or sterilization of the patient or her partner can be used in combination with a nonhormonal medication to manage vasomotor symptoms. Though the only Food and Drug Administration–approved nonhormonal option is paroxetine (Paxil) 7.5 mg/day, a variety of choices have been found effective in clinical trials. These include citalopram (Celexa) and escitalopram (Lexapro), venlafaxine (Effexor), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), gabapentin (Neurontin), and pregabalin (Lyrica).

Contraception should be continued until the patient has experienced 12 months of continuous amenorrhea if over the age of 50 years, or 2 years of amenorrhea if she is younger than 50 years, said Dr. Casey. A predictive model for onset of menopause has been developed that takes age, smoking, bleeding patterns, and estrogen and follicle-stimulating hormone levels into account, but “further study is needed before applying this model clinically,” said Dr. Casey. The decision about when to discontinue contraception also depends on the impact it will have on the particular couple. “Shared decision making is of the utmost importance,” she said.

Dr. Casey disclosed that she is a certified Nexplanon trainer and has received research grant support from Merck.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NAMS 2015 ANNUAL MEETING

New guideline allows use of estrogen for hot flashes – with caveats

Clinicians treating vasomotor and genitourinary symptoms of menopause should consider estrogen therapy for healthy women with moderate to severe symptoms and no contraindications to hormone therapy, according to a new clinical practice guideline issued by the Endocrine Society.

The guideline, developed by an international panel, is designed to be a comprehensive document that emphasizes individualized clinical recommendations and generally takes a conservative approach to balancing risks and benefits, said Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel, chair of the task force that developed the guideline and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“We need to be very mindful of the individual health concerns of our patient – is the individual therapy that we choose safe for her?” noted Dr. Stuenkel during a web-hosted press conference announcing the publication of the guideline.

For women under 60 years of age or fewer than 10 years past menopause who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and are without contraindications, the guideline suggests initiating estrogen therapy, supplemented by a progestogen for those women who have a uterus (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2236).

The discussion regarding treatment options should be grounded by a obtaining a baseline history of and assessing risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and breast cancer. “Menopause is a portal to the second half of life,” so clinicians should address bone health, smoking cessation, alcohol use, and cardiovascular and cancer risks and screening in their discussion, said Dr. Stuenkel.

The panel makes specific recommendations to tailor treatment depending on risk. For example, women at intermediate to high risk of breast cancer should be steered toward nonhormonal therapies to relieve VMS. Those at moderate risk of CVD can consider transdermal estradiol, while nonhormonal therapies are recommended for the high–CVD risk group.

The genitourinary symptoms of menopause (GSM) can include not just vulvovaginal atrophy but also urinary frequency and recurrent urinary tract infections, said Dr. Stuenkel, so the panel used the broader terminology to address estrogen’s effect on both organ systems.

An initial trial of vaginal moisturizers, used at least twice weekly, supplemented by lubricants as needed before sexual activity, should be the first-line treatment for GSM. For women with persistent symptoms and no history of estrogen-dependent cancers, low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy is a logical next step and does not require accompanying progestogen treatment, according to the guideline.

For women with symptomatic GSM who have had breast or endometrial cancer whose symptoms are not sufficiently treated by nonhormonal methods, low-dose vaginal estrogen is a consideration. This option should be considered with a shared decision-making approach that involves the patient’s oncologist.

Conjugated equine estrogens plus bazedoxefine, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator (Duavee) can treat VMS and provide protection against bone loss, said the task force. The guideline recommends against the use of custom-compounded hormonal therapy and recommends the use of Food and Drug Administration–approved formulations. Ospemifene can be considered in women with significant dyspareunia and without contraindications, which include a history of breast cancer.

In conclusion, the guideline calls for ongoing rigorous study of the optimal agents and dosing for treatment of symptoms, how best to balance symptom relief with chronic disease prevention, and the merits of long-term hormone therapy beyond the period when symptomatic relief of VMS is needed. “International registries and clinical trials are overdue to address the long-reaching implications of these important issues,” said Dr. Stuenkel and coauthors of the guideline.

Dr. Stuenkel reported no relevant financial disclosures. Three task force members, Dr. Susan Davis, Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton, and Dr. Richard Santen, reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies. Cosponsoring organizations included the Australasian Menopause Society, the British Menopause Society, European Menopause and Andropause Society, the European Society of Endocrinology, and the International Menopause Society.

On Twitter @karioakes

Clinicians treating vasomotor and genitourinary symptoms of menopause should consider estrogen therapy for healthy women with moderate to severe symptoms and no contraindications to hormone therapy, according to a new clinical practice guideline issued by the Endocrine Society.

The guideline, developed by an international panel, is designed to be a comprehensive document that emphasizes individualized clinical recommendations and generally takes a conservative approach to balancing risks and benefits, said Dr. Cynthia Stuenkel, chair of the task force that developed the guideline and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

“We need to be very mindful of the individual health concerns of our patient – is the individual therapy that we choose safe for her?” noted Dr. Stuenkel during a web-hosted press conference announcing the publication of the guideline.

For women under 60 years of age or fewer than 10 years past menopause who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and are without contraindications, the guideline suggests initiating estrogen therapy, supplemented by a progestogen for those women who have a uterus (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2236).

The discussion regarding treatment options should be grounded by a obtaining a baseline history of and assessing risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and breast cancer. “Menopause is a portal to the second half of life,” so clinicians should address bone health, smoking cessation, alcohol use, and cardiovascular and cancer risks and screening in their discussion, said Dr. Stuenkel.