User login

Estrogen therapy linked to brain atrophy in women with diabetes

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2015

Key clinical point: Prescribing estrogen therapy for older women with type 2 diabetes could increase the risk of brain atrophy.

Major finding: Older women with type 2 diabetes who took estrogen therapy had about an 18-cc lower total brain volume than women with diabetes who took placebo and than women without the disease.

Data source: WHIMS-MRI was a large parallel-group study that examined the effect of hormone therapy on the brain and cognition in postmenopausal women.

Disclosures: Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FDA advisors urge physician certification for flibanserin

Without the option of recommending physician certification as a condition for flibanserin approval, the Food and Drug Administration advisory panel vote might have shifted against approval of the drug for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women.

At a joint meeting of two FDA advisory panels in June, members of the Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee voted 18-6 that the overall benefit-risk profile of flibanserin supported approval for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women, provided that certain risk management options beyond labeling were implemented. If approved by the FDA, flibanserin would be the first drug approved for treating HSDD.

Assurance that prescribers would be fully apprised of the serious risks of hypotension and syncope associated with the drug, exacerbation of those side effects when combined with alcohol or a CYP3A4 inhibitor – and the modest effects over placebo – was cited by several of the panelists who voted in favor of approval.

All of those voting in favor of approval chose the option of supporting approval “only if certain risk management options beyond labeling are implemented.” None of the panelists voted for the option of supporting approval with “labeling alone to manage the risks.”

The conditions include a risk management plan to address serious adverse effects associated with the drug, a requirement for physician certification, and postmarketing studies to further evaluate and monitor the drug’s safety and efficacy.

The risks of hypotension and syncope, and central nervous system depression are also exacerbated by moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, but the interaction with alcohol was raised as a particularly serious issue because of the high rate of alcohol use and binge drinking among women who would likely be treated with flibanserin, according to FDA reviewers.

The risk of drug interactions can be mitigated with drug interaction screening programs used in health care systems, such as in electronic medical records and pharmacies, while alcohol use is a patient-dependent behavior, is common among women, and therefore more difficult to control, Kimberly Lehrfeld, Pharm.D., a team leader in the division of risk management in the FDA’s office of medication error prevention and analysis, said at the meeting. Several panelists recommended that alcohol use be a contraindication.

Physician certification is among the Elements to Assure Safe Use or ETASU, which along with a medication guide and a communication plan for health care providers, are components of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), a way to help manage the risks of a drug or biologic while still making it available to patients who need it.

Physician certification is part of the REMS for drugs such as mifepristone (Mifeprex), thalidomide (Thalomid), and natalizumab (Tysabri).

“A risk strategy that gets physicians the information they need to use it properly is going to be key,” said Dr. Robert Silbergleit, who voted for approval.”A REMS strategy is going to be very important because I think that the most likely risks … are going to come from physicians who don’t use the drug properly because they’re not properly educated.”

Dr. Silbergleit, a professor in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said he was also concerned about the marketing of the drug. “Clinicians may be in the situation where they have to counter direct-to-consumer marketing that could lead to misuse of the drug,” he said at the meeting.

Also voting for approval, Marjorie Shaw Phillips, R.Ph., pharmacy coordinator at Georgia Regents Medical Center in Augusta, said that everyone needs to be aware of the potential safety concerns. But while she does not think pharmacy registration would be beneficial, there is a role for the pharmacist to confirm that it’s an educated provider prescribing the drug and that they’ve discussed the risks with the patient.

She added that it will be important for physicians to set realistic expectations for patients.

“It’s not a magical little pink pill, and there are going to be a whole lot of women with sexual dysfunction for whom there’s no evidence that it’s going to benefit them,” she said at the meeting.

The panel did not specifically recommend pharmacy certification, but pharmacists would have to verify that the prescribing physicians are certified, if the drug is approved, an FDA official said at the meeting.

A decision from the FDA is expected in August. The FDA panelists reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, flibanserin’s manufacturer, said in a statement that the company looks forward “to continuing our work with the FDA as it completes its review of our new drug application, including the discussion of a Risks Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.” If approved, the company plans to market flibanserin as “Addyi.”

Without the option of recommending physician certification as a condition for flibanserin approval, the Food and Drug Administration advisory panel vote might have shifted against approval of the drug for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women.

At a joint meeting of two FDA advisory panels in June, members of the Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee voted 18-6 that the overall benefit-risk profile of flibanserin supported approval for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women, provided that certain risk management options beyond labeling were implemented. If approved by the FDA, flibanserin would be the first drug approved for treating HSDD.

Assurance that prescribers would be fully apprised of the serious risks of hypotension and syncope associated with the drug, exacerbation of those side effects when combined with alcohol or a CYP3A4 inhibitor – and the modest effects over placebo – was cited by several of the panelists who voted in favor of approval.

All of those voting in favor of approval chose the option of supporting approval “only if certain risk management options beyond labeling are implemented.” None of the panelists voted for the option of supporting approval with “labeling alone to manage the risks.”

The conditions include a risk management plan to address serious adverse effects associated with the drug, a requirement for physician certification, and postmarketing studies to further evaluate and monitor the drug’s safety and efficacy.

The risks of hypotension and syncope, and central nervous system depression are also exacerbated by moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, but the interaction with alcohol was raised as a particularly serious issue because of the high rate of alcohol use and binge drinking among women who would likely be treated with flibanserin, according to FDA reviewers.

The risk of drug interactions can be mitigated with drug interaction screening programs used in health care systems, such as in electronic medical records and pharmacies, while alcohol use is a patient-dependent behavior, is common among women, and therefore more difficult to control, Kimberly Lehrfeld, Pharm.D., a team leader in the division of risk management in the FDA’s office of medication error prevention and analysis, said at the meeting. Several panelists recommended that alcohol use be a contraindication.

Physician certification is among the Elements to Assure Safe Use or ETASU, which along with a medication guide and a communication plan for health care providers, are components of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), a way to help manage the risks of a drug or biologic while still making it available to patients who need it.

Physician certification is part of the REMS for drugs such as mifepristone (Mifeprex), thalidomide (Thalomid), and natalizumab (Tysabri).

“A risk strategy that gets physicians the information they need to use it properly is going to be key,” said Dr. Robert Silbergleit, who voted for approval.”A REMS strategy is going to be very important because I think that the most likely risks … are going to come from physicians who don’t use the drug properly because they’re not properly educated.”

Dr. Silbergleit, a professor in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said he was also concerned about the marketing of the drug. “Clinicians may be in the situation where they have to counter direct-to-consumer marketing that could lead to misuse of the drug,” he said at the meeting.

Also voting for approval, Marjorie Shaw Phillips, R.Ph., pharmacy coordinator at Georgia Regents Medical Center in Augusta, said that everyone needs to be aware of the potential safety concerns. But while she does not think pharmacy registration would be beneficial, there is a role for the pharmacist to confirm that it’s an educated provider prescribing the drug and that they’ve discussed the risks with the patient.

She added that it will be important for physicians to set realistic expectations for patients.

“It’s not a magical little pink pill, and there are going to be a whole lot of women with sexual dysfunction for whom there’s no evidence that it’s going to benefit them,” she said at the meeting.

The panel did not specifically recommend pharmacy certification, but pharmacists would have to verify that the prescribing physicians are certified, if the drug is approved, an FDA official said at the meeting.

A decision from the FDA is expected in August. The FDA panelists reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, flibanserin’s manufacturer, said in a statement that the company looks forward “to continuing our work with the FDA as it completes its review of our new drug application, including the discussion of a Risks Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.” If approved, the company plans to market flibanserin as “Addyi.”

Without the option of recommending physician certification as a condition for flibanserin approval, the Food and Drug Administration advisory panel vote might have shifted against approval of the drug for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women.

At a joint meeting of two FDA advisory panels in June, members of the Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee voted 18-6 that the overall benefit-risk profile of flibanserin supported approval for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women, provided that certain risk management options beyond labeling were implemented. If approved by the FDA, flibanserin would be the first drug approved for treating HSDD.

Assurance that prescribers would be fully apprised of the serious risks of hypotension and syncope associated with the drug, exacerbation of those side effects when combined with alcohol or a CYP3A4 inhibitor – and the modest effects over placebo – was cited by several of the panelists who voted in favor of approval.

All of those voting in favor of approval chose the option of supporting approval “only if certain risk management options beyond labeling are implemented.” None of the panelists voted for the option of supporting approval with “labeling alone to manage the risks.”

The conditions include a risk management plan to address serious adverse effects associated with the drug, a requirement for physician certification, and postmarketing studies to further evaluate and monitor the drug’s safety and efficacy.

The risks of hypotension and syncope, and central nervous system depression are also exacerbated by moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors, but the interaction with alcohol was raised as a particularly serious issue because of the high rate of alcohol use and binge drinking among women who would likely be treated with flibanserin, according to FDA reviewers.

The risk of drug interactions can be mitigated with drug interaction screening programs used in health care systems, such as in electronic medical records and pharmacies, while alcohol use is a patient-dependent behavior, is common among women, and therefore more difficult to control, Kimberly Lehrfeld, Pharm.D., a team leader in the division of risk management in the FDA’s office of medication error prevention and analysis, said at the meeting. Several panelists recommended that alcohol use be a contraindication.

Physician certification is among the Elements to Assure Safe Use or ETASU, which along with a medication guide and a communication plan for health care providers, are components of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), a way to help manage the risks of a drug or biologic while still making it available to patients who need it.

Physician certification is part of the REMS for drugs such as mifepristone (Mifeprex), thalidomide (Thalomid), and natalizumab (Tysabri).

“A risk strategy that gets physicians the information they need to use it properly is going to be key,” said Dr. Robert Silbergleit, who voted for approval.”A REMS strategy is going to be very important because I think that the most likely risks … are going to come from physicians who don’t use the drug properly because they’re not properly educated.”

Dr. Silbergleit, a professor in the department of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said he was also concerned about the marketing of the drug. “Clinicians may be in the situation where they have to counter direct-to-consumer marketing that could lead to misuse of the drug,” he said at the meeting.

Also voting for approval, Marjorie Shaw Phillips, R.Ph., pharmacy coordinator at Georgia Regents Medical Center in Augusta, said that everyone needs to be aware of the potential safety concerns. But while she does not think pharmacy registration would be beneficial, there is a role for the pharmacist to confirm that it’s an educated provider prescribing the drug and that they’ve discussed the risks with the patient.

She added that it will be important for physicians to set realistic expectations for patients.

“It’s not a magical little pink pill, and there are going to be a whole lot of women with sexual dysfunction for whom there’s no evidence that it’s going to benefit them,” she said at the meeting.

The panel did not specifically recommend pharmacy certification, but pharmacists would have to verify that the prescribing physicians are certified, if the drug is approved, an FDA official said at the meeting.

A decision from the FDA is expected in August. The FDA panelists reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, flibanserin’s manufacturer, said in a statement that the company looks forward “to continuing our work with the FDA as it completes its review of our new drug application, including the discussion of a Risks Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.” If approved, the company plans to market flibanserin as “Addyi.”

CMSC: Many menopausal and MS symptoms overlap

INDIANAPOLIS – About 50% of women with multiple sclerosis are postmenopausal, but objective data about the impact of menopause on the course of multiple sclerosis are lacking.

“We don’t know anything about the impact of menopause on the MS course; there is wide variability in patient-reported outcomes, but nothing written about comorbidities or symptom management,” Dr. Riley Bove, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “We’ve been working on this. A lot of it is unknown.”

She described menopause is “an opportunity for providers to tackle symptoms and improve well-being and discuss meaningful quality of life and priorities with patients. It can be a good time to talk about these things.”

In a study that Dr. Bove conducted with the online patient-powered research platform PatientsLikeMe, female MS patients were asked to describe the impact of menopause on their disease. Among the themes that emerged were an occasional perimenopausal onset of MS (“menopause and MS symptoms were pretty much simultaneous,” one 58-year-old respondent said); the effect of hot flashes on MS symptoms (“I confused the two, especially hot flashes,” said a 53-year-old woman); and worsening of MS-related disability after menopause, particularly surgical (“Before I stopped taking birth control pills I was working and able to walk and house clean , etc.,” a 53-year-old respondent said. “I had the surgery, and I started to progress toward being completely wheelchair bound.”)

When it comes to solid recommendations for how to manage MS symptoms that overlap with menopause, “we’re in an evidence-free zone,” Dr. Bove said. “Symptoms in MS are kind of like dominoes: You have difficulty sleeping and then your day is off, fatigue is up and your mood is off, and everything can spiral. In the clinic, perimenopausal women often say things like, ‘I feel like I’m falling apart’ or ‘something has to give’ or ‘I need a change.’ ”

Common overlapping symptoms include vasomotor manifestations such as hot flashes, cold flashes, vascular instability, and rapid heartbeat. “The leading mechanistic explanation for the vasomotor symptoms is that abrupt hormone deprivation will result in the loss of negative feedback over hypothalamic NA [noradrenaline] synthesis,” Dr. Bove explained. “The proximity of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center to luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone-producing areas may also be involved.”

Sleep disturbances and insomnia in menopausal MS patients can impact fatigue and mood. Also, hot flashes can directly exacerbate the MS symptoms, fluctuating over the day or the week.

According to recommendations from the North American Menopause Society, estradiol is the most effective therapy for treating vasomotor symptoms. Other options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). “Probably the best studied SNRI is venlafaxine,” Dr. Bove said. “It seems to have modest effects on sleep quality and insomnia perimenopausally, as well as on hot flashes.”

Other alternatives include clonidine and gabapentin.

“If a patient wants to use [hormone therapy] for menopausal symptoms, it has to be an individualized approach,” Dr. Bove said. “You have to communicate with the primary care physician to understand what else is going on in this woman’s medical history. The current recommendations are to treat the symptoms with as low a dose as possible for as short a duration as possible. Our MS patients are also at risk for neurodegeneration, for brain volume loss, for cognitive decline, and for worsening function over time.”

With respect to cognition, observational studies have demonstrated that during a certain window of opportunity – defined as within 5 years of the last menstrual period – hormone therapy (HT) may have protective effects against Alzheimer’s disease and against cognitive decline in general. “Beyond this window of time, perhaps due to estrogen receptor down regulation, HT can be harmful, with an increased risk of stroke and dementia reported later on,” she said.

Against this, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) looked at unopposed estrogen, and estrogen and progestin combination, compared with placebo. It found that in women who initiated HT at the age of 65 or older faced an increased risk of dementia from any cause, and of cognitive decline. “This study really put the kibosh on HT as a form of neuroprotection,” Dr. Bove said. “But perhaps it’s unfair to the many patients who are at risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration, because the WHIMS did not find an increased risk of adverse cognitive events in women in whom HT was started perimenopausally. Longitudinal, placebo-controlled trials of the effects of HT within the window of opportunity are required to either prove or refute the observational studies that already exist that suggest HT may be neuroprotective. This is an important point to discuss with patients.”

The impact of perimenopausal sleep disturbance on MS symptoms also is unknown. A practical approach to managing sleep disturbance in perimenopausal MS patients is to identify and assess the triggers. “If the bladder symptoms are the major trigger versus mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety, the intervention will be different,” she said. “Consider counseling and/or consultation with a sleep specialist.” Some patients may benefit from pharmacologic treatment to “get them over the hump and get them sleeping better for a little while, versus longer term management if they have a life history of insomnia,” she said. “If the problem is sleep management, you’ll need a drug with a longer half-life. Consider other comorbidities such as anxiety and restless leg syndrome.” Classes of medications to consider include benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs and SNRIs.

Mood symptoms commonly overlap in menopausal patients with MS, especially those related to depression and anxiety. “They may be underdiagnosed and undertreated,” Dr. Bove said. “It’s been shown that depression influences the perceived severity of other MS symptoms. Depression is a strong predictor of cognitive and sexual dysfunction, so our perimenopausal MS women have a vulnerability to more severe mood symptoms.” Managing mood symptoms “needs to be multifaceted” and may include psychotherapy to optimize coping abilities, antidepressants, support groups, fatigue and sleep optimization, and social work “to see how employment or financial stressors may be playing a role in a person’s mood.”

In addition, menopausal women may report changes in attention, executive function, multitasking, word finding difficulties, and memory problems, especially in the first year after the final menstrual period. “It’s known that about half of MS patients experience some degree of cognitive impairment,” she said. “Neurocognitive testing may help to identify particular areas of dysfunction that would be amenable to some kind of cognitive rehabilitation.”

Bladder symptoms also can impact postmenopausal patients, especially increasing bladder irritability and incontinence (stress and urge). In MS, “the baseline bladder dysfunction may be magnified,” Dr. Bove said. “If you’re trying to tease out whether the postmenopausal bladder symptoms are from menopause or MS, the MS relapses tend to have more urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, and the presentation will be more acute. Urodynamic testing can be used to tease this out. The big lifestyle piece that urologists like to hone in on is that people in America drink too much fluid. A practical guideline is that after 3 p.m. just drink for thirst; don’t worry that everything will fall apart if you don’t get your eight glasses of water per day in. If you’re not thirsty, you probably don’t need it.”

While postmenopausal women face an increased risk for osteoporosis, that risk is magnified for MS patients because of the cumulative effect of steroid use – particularly for those who were diagnosed in the pre–disease-modifying-therapy era – being sedentary, and being deconditioned. “Other MS issues such as balance, vision problems, strength or cognitive impairments may all impact gait and compound the risk of falls,” Dr. Bove said. “Osteoporosis prevention and screening should be encouraged in these patients.”

Dr. Bove concluded her presentation by noting that in general, women with disabilities are less likely to be up to date on Pap tests, mammograms, and other important preventive screening tests. “The magnitude of disparities is greater for women with complex limitations,” she said. “Women with MS may have a lower cancer risk, but a larger tumor size at diagnosis.” For example, “is this because the patient is uncomfortable getting on an exam table to get a Pap smear, or is the physician not thinking about other aspects of the person’s life because the focus is on the MS?”

Dr. Bove disclosed that she has received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the National Institutes of Health, and from the Harvard Clinical Investigator Training Program.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

INDIANAPOLIS – About 50% of women with multiple sclerosis are postmenopausal, but objective data about the impact of menopause on the course of multiple sclerosis are lacking.

“We don’t know anything about the impact of menopause on the MS course; there is wide variability in patient-reported outcomes, but nothing written about comorbidities or symptom management,” Dr. Riley Bove, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “We’ve been working on this. A lot of it is unknown.”

She described menopause is “an opportunity for providers to tackle symptoms and improve well-being and discuss meaningful quality of life and priorities with patients. It can be a good time to talk about these things.”

In a study that Dr. Bove conducted with the online patient-powered research platform PatientsLikeMe, female MS patients were asked to describe the impact of menopause on their disease. Among the themes that emerged were an occasional perimenopausal onset of MS (“menopause and MS symptoms were pretty much simultaneous,” one 58-year-old respondent said); the effect of hot flashes on MS symptoms (“I confused the two, especially hot flashes,” said a 53-year-old woman); and worsening of MS-related disability after menopause, particularly surgical (“Before I stopped taking birth control pills I was working and able to walk and house clean , etc.,” a 53-year-old respondent said. “I had the surgery, and I started to progress toward being completely wheelchair bound.”)

When it comes to solid recommendations for how to manage MS symptoms that overlap with menopause, “we’re in an evidence-free zone,” Dr. Bove said. “Symptoms in MS are kind of like dominoes: You have difficulty sleeping and then your day is off, fatigue is up and your mood is off, and everything can spiral. In the clinic, perimenopausal women often say things like, ‘I feel like I’m falling apart’ or ‘something has to give’ or ‘I need a change.’ ”

Common overlapping symptoms include vasomotor manifestations such as hot flashes, cold flashes, vascular instability, and rapid heartbeat. “The leading mechanistic explanation for the vasomotor symptoms is that abrupt hormone deprivation will result in the loss of negative feedback over hypothalamic NA [noradrenaline] synthesis,” Dr. Bove explained. “The proximity of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center to luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone-producing areas may also be involved.”

Sleep disturbances and insomnia in menopausal MS patients can impact fatigue and mood. Also, hot flashes can directly exacerbate the MS symptoms, fluctuating over the day or the week.

According to recommendations from the North American Menopause Society, estradiol is the most effective therapy for treating vasomotor symptoms. Other options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). “Probably the best studied SNRI is venlafaxine,” Dr. Bove said. “It seems to have modest effects on sleep quality and insomnia perimenopausally, as well as on hot flashes.”

Other alternatives include clonidine and gabapentin.

“If a patient wants to use [hormone therapy] for menopausal symptoms, it has to be an individualized approach,” Dr. Bove said. “You have to communicate with the primary care physician to understand what else is going on in this woman’s medical history. The current recommendations are to treat the symptoms with as low a dose as possible for as short a duration as possible. Our MS patients are also at risk for neurodegeneration, for brain volume loss, for cognitive decline, and for worsening function over time.”

With respect to cognition, observational studies have demonstrated that during a certain window of opportunity – defined as within 5 years of the last menstrual period – hormone therapy (HT) may have protective effects against Alzheimer’s disease and against cognitive decline in general. “Beyond this window of time, perhaps due to estrogen receptor down regulation, HT can be harmful, with an increased risk of stroke and dementia reported later on,” she said.

Against this, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) looked at unopposed estrogen, and estrogen and progestin combination, compared with placebo. It found that in women who initiated HT at the age of 65 or older faced an increased risk of dementia from any cause, and of cognitive decline. “This study really put the kibosh on HT as a form of neuroprotection,” Dr. Bove said. “But perhaps it’s unfair to the many patients who are at risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration, because the WHIMS did not find an increased risk of adverse cognitive events in women in whom HT was started perimenopausally. Longitudinal, placebo-controlled trials of the effects of HT within the window of opportunity are required to either prove or refute the observational studies that already exist that suggest HT may be neuroprotective. This is an important point to discuss with patients.”

The impact of perimenopausal sleep disturbance on MS symptoms also is unknown. A practical approach to managing sleep disturbance in perimenopausal MS patients is to identify and assess the triggers. “If the bladder symptoms are the major trigger versus mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety, the intervention will be different,” she said. “Consider counseling and/or consultation with a sleep specialist.” Some patients may benefit from pharmacologic treatment to “get them over the hump and get them sleeping better for a little while, versus longer term management if they have a life history of insomnia,” she said. “If the problem is sleep management, you’ll need a drug with a longer half-life. Consider other comorbidities such as anxiety and restless leg syndrome.” Classes of medications to consider include benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs and SNRIs.

Mood symptoms commonly overlap in menopausal patients with MS, especially those related to depression and anxiety. “They may be underdiagnosed and undertreated,” Dr. Bove said. “It’s been shown that depression influences the perceived severity of other MS symptoms. Depression is a strong predictor of cognitive and sexual dysfunction, so our perimenopausal MS women have a vulnerability to more severe mood symptoms.” Managing mood symptoms “needs to be multifaceted” and may include psychotherapy to optimize coping abilities, antidepressants, support groups, fatigue and sleep optimization, and social work “to see how employment or financial stressors may be playing a role in a person’s mood.”

In addition, menopausal women may report changes in attention, executive function, multitasking, word finding difficulties, and memory problems, especially in the first year after the final menstrual period. “It’s known that about half of MS patients experience some degree of cognitive impairment,” she said. “Neurocognitive testing may help to identify particular areas of dysfunction that would be amenable to some kind of cognitive rehabilitation.”

Bladder symptoms also can impact postmenopausal patients, especially increasing bladder irritability and incontinence (stress and urge). In MS, “the baseline bladder dysfunction may be magnified,” Dr. Bove said. “If you’re trying to tease out whether the postmenopausal bladder symptoms are from menopause or MS, the MS relapses tend to have more urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, and the presentation will be more acute. Urodynamic testing can be used to tease this out. The big lifestyle piece that urologists like to hone in on is that people in America drink too much fluid. A practical guideline is that after 3 p.m. just drink for thirst; don’t worry that everything will fall apart if you don’t get your eight glasses of water per day in. If you’re not thirsty, you probably don’t need it.”

While postmenopausal women face an increased risk for osteoporosis, that risk is magnified for MS patients because of the cumulative effect of steroid use – particularly for those who were diagnosed in the pre–disease-modifying-therapy era – being sedentary, and being deconditioned. “Other MS issues such as balance, vision problems, strength or cognitive impairments may all impact gait and compound the risk of falls,” Dr. Bove said. “Osteoporosis prevention and screening should be encouraged in these patients.”

Dr. Bove concluded her presentation by noting that in general, women with disabilities are less likely to be up to date on Pap tests, mammograms, and other important preventive screening tests. “The magnitude of disparities is greater for women with complex limitations,” she said. “Women with MS may have a lower cancer risk, but a larger tumor size at diagnosis.” For example, “is this because the patient is uncomfortable getting on an exam table to get a Pap smear, or is the physician not thinking about other aspects of the person’s life because the focus is on the MS?”

Dr. Bove disclosed that she has received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the National Institutes of Health, and from the Harvard Clinical Investigator Training Program.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

INDIANAPOLIS – About 50% of women with multiple sclerosis are postmenopausal, but objective data about the impact of menopause on the course of multiple sclerosis are lacking.

“We don’t know anything about the impact of menopause on the MS course; there is wide variability in patient-reported outcomes, but nothing written about comorbidities or symptom management,” Dr. Riley Bove, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “We’ve been working on this. A lot of it is unknown.”

She described menopause is “an opportunity for providers to tackle symptoms and improve well-being and discuss meaningful quality of life and priorities with patients. It can be a good time to talk about these things.”

In a study that Dr. Bove conducted with the online patient-powered research platform PatientsLikeMe, female MS patients were asked to describe the impact of menopause on their disease. Among the themes that emerged were an occasional perimenopausal onset of MS (“menopause and MS symptoms were pretty much simultaneous,” one 58-year-old respondent said); the effect of hot flashes on MS symptoms (“I confused the two, especially hot flashes,” said a 53-year-old woman); and worsening of MS-related disability after menopause, particularly surgical (“Before I stopped taking birth control pills I was working and able to walk and house clean , etc.,” a 53-year-old respondent said. “I had the surgery, and I started to progress toward being completely wheelchair bound.”)

When it comes to solid recommendations for how to manage MS symptoms that overlap with menopause, “we’re in an evidence-free zone,” Dr. Bove said. “Symptoms in MS are kind of like dominoes: You have difficulty sleeping and then your day is off, fatigue is up and your mood is off, and everything can spiral. In the clinic, perimenopausal women often say things like, ‘I feel like I’m falling apart’ or ‘something has to give’ or ‘I need a change.’ ”

Common overlapping symptoms include vasomotor manifestations such as hot flashes, cold flashes, vascular instability, and rapid heartbeat. “The leading mechanistic explanation for the vasomotor symptoms is that abrupt hormone deprivation will result in the loss of negative feedback over hypothalamic NA [noradrenaline] synthesis,” Dr. Bove explained. “The proximity of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center to luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone-producing areas may also be involved.”

Sleep disturbances and insomnia in menopausal MS patients can impact fatigue and mood. Also, hot flashes can directly exacerbate the MS symptoms, fluctuating over the day or the week.

According to recommendations from the North American Menopause Society, estradiol is the most effective therapy for treating vasomotor symptoms. Other options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). “Probably the best studied SNRI is venlafaxine,” Dr. Bove said. “It seems to have modest effects on sleep quality and insomnia perimenopausally, as well as on hot flashes.”

Other alternatives include clonidine and gabapentin.

“If a patient wants to use [hormone therapy] for menopausal symptoms, it has to be an individualized approach,” Dr. Bove said. “You have to communicate with the primary care physician to understand what else is going on in this woman’s medical history. The current recommendations are to treat the symptoms with as low a dose as possible for as short a duration as possible. Our MS patients are also at risk for neurodegeneration, for brain volume loss, for cognitive decline, and for worsening function over time.”

With respect to cognition, observational studies have demonstrated that during a certain window of opportunity – defined as within 5 years of the last menstrual period – hormone therapy (HT) may have protective effects against Alzheimer’s disease and against cognitive decline in general. “Beyond this window of time, perhaps due to estrogen receptor down regulation, HT can be harmful, with an increased risk of stroke and dementia reported later on,” she said.

Against this, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) looked at unopposed estrogen, and estrogen and progestin combination, compared with placebo. It found that in women who initiated HT at the age of 65 or older faced an increased risk of dementia from any cause, and of cognitive decline. “This study really put the kibosh on HT as a form of neuroprotection,” Dr. Bove said. “But perhaps it’s unfair to the many patients who are at risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration, because the WHIMS did not find an increased risk of adverse cognitive events in women in whom HT was started perimenopausally. Longitudinal, placebo-controlled trials of the effects of HT within the window of opportunity are required to either prove or refute the observational studies that already exist that suggest HT may be neuroprotective. This is an important point to discuss with patients.”

The impact of perimenopausal sleep disturbance on MS symptoms also is unknown. A practical approach to managing sleep disturbance in perimenopausal MS patients is to identify and assess the triggers. “If the bladder symptoms are the major trigger versus mood disturbances such as depression and anxiety, the intervention will be different,” she said. “Consider counseling and/or consultation with a sleep specialist.” Some patients may benefit from pharmacologic treatment to “get them over the hump and get them sleeping better for a little while, versus longer term management if they have a life history of insomnia,” she said. “If the problem is sleep management, you’ll need a drug with a longer half-life. Consider other comorbidities such as anxiety and restless leg syndrome.” Classes of medications to consider include benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs and SNRIs.

Mood symptoms commonly overlap in menopausal patients with MS, especially those related to depression and anxiety. “They may be underdiagnosed and undertreated,” Dr. Bove said. “It’s been shown that depression influences the perceived severity of other MS symptoms. Depression is a strong predictor of cognitive and sexual dysfunction, so our perimenopausal MS women have a vulnerability to more severe mood symptoms.” Managing mood symptoms “needs to be multifaceted” and may include psychotherapy to optimize coping abilities, antidepressants, support groups, fatigue and sleep optimization, and social work “to see how employment or financial stressors may be playing a role in a person’s mood.”

In addition, menopausal women may report changes in attention, executive function, multitasking, word finding difficulties, and memory problems, especially in the first year after the final menstrual period. “It’s known that about half of MS patients experience some degree of cognitive impairment,” she said. “Neurocognitive testing may help to identify particular areas of dysfunction that would be amenable to some kind of cognitive rehabilitation.”

Bladder symptoms also can impact postmenopausal patients, especially increasing bladder irritability and incontinence (stress and urge). In MS, “the baseline bladder dysfunction may be magnified,” Dr. Bove said. “If you’re trying to tease out whether the postmenopausal bladder symptoms are from menopause or MS, the MS relapses tend to have more urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, and the presentation will be more acute. Urodynamic testing can be used to tease this out. The big lifestyle piece that urologists like to hone in on is that people in America drink too much fluid. A practical guideline is that after 3 p.m. just drink for thirst; don’t worry that everything will fall apart if you don’t get your eight glasses of water per day in. If you’re not thirsty, you probably don’t need it.”

While postmenopausal women face an increased risk for osteoporosis, that risk is magnified for MS patients because of the cumulative effect of steroid use – particularly for those who were diagnosed in the pre–disease-modifying-therapy era – being sedentary, and being deconditioned. “Other MS issues such as balance, vision problems, strength or cognitive impairments may all impact gait and compound the risk of falls,” Dr. Bove said. “Osteoporosis prevention and screening should be encouraged in these patients.”

Dr. Bove concluded her presentation by noting that in general, women with disabilities are less likely to be up to date on Pap tests, mammograms, and other important preventive screening tests. “The magnitude of disparities is greater for women with complex limitations,” she said. “Women with MS may have a lower cancer risk, but a larger tumor size at diagnosis.” For example, “is this because the patient is uncomfortable getting on an exam table to get a Pap smear, or is the physician not thinking about other aspects of the person’s life because the focus is on the MS?”

Dr. Bove disclosed that she has received funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the National Institutes of Health, and from the Harvard Clinical Investigator Training Program.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

Hormone therapy helps mood, but not cognition, in younger menopausal women

For recently postmenopausal women, oral combined hormone therapy may help with symptoms of depression and anxiety. But hormone therapy did not produce any changes in cognition.

In a large, randomized controlled trial of oral and transdermal estrogens compared with each other and placebo, Carey Gleason, Ph.D., of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues found that exogenous estrogen had no effect on cognitive performance in recently postmenopausal women over a 4-year study period. For women taking low-dose oral conjugated equine estrogens, a small to moderate improvement in some mood symptoms occurred; women receiving estrogen via a transdermal patch did not see this improvement in mood.

The results were published in PLOS Medicine (PLoS. Med. 2015;12:e1001833 [doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833]).

Previous studies had shown mixed findings of the effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cognition, largely depending on whether treatment was initiated early on or later in menopause.

The 693 participants in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study - Cognitive and Affective Study (KEEPS-Cog) were a mean 52.6 years old, and the average time since the last menstrual period was 1.4 years. Enrollees were randomized to one of three study arms where they received either a 0.45 mg/day oral conjugated equine estrogen tablet, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo skin patch; or a 50 microgram/day transdermal estradiol patch, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo tablet; or a placebo tablet, capsule and patch. Treatment lasted for 4 years.

Cognitive status was measured over the 4 years using the Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) exam and an additional battery of cognitive tests that assessed verbal learning, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental and linguistic flexibility. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) was used to evaluate mood. This test, designed to detect specific affective states in nondepressed individuals, assessed levels of tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue, vigor, and confusion-bewilderment.

Dr. Gleason and her colleagues found no improvement in cognitive function with either formulation of menopausal hormone therapy.

“Contrary to our hypothesis, treatment with t-E2 [transdermal estrogen] did not improve cognition in recently postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

For women taking oral estrogen, POMS subscores for tension-anxiety and depression-dejection showed significant improvement over time (for both, P < 0.001). The effect was not seen for transdermal estrogen; Dr. Gleason and her colleagues hypothesized that differences in the formulations of the two products, which resulted in different levels of estradiol versus estrone in participants, may have contributed to the result.

Most of the study’s enrollees were white women with low risk for cardiovascular disease, and most participants had at least a bachelor’s degree, so the generalizability of the KEEPS-Cog findings may be limited. Also, the study’s length and design did not permit assessment of dementia or other clinical diagnoses.

The KEEPS-Cog study, said Dr. Gleason and colleagues, can be incorporated into clinical decision making for women deciding whether to use menopausal hormone therapy. Using these results, a younger woman in good cardiovascular health “can weigh the known risks of [menopausal hormone therapy] against potential benefits for her unique symptom profile, and make an informed decision as to whether she would benefit from [menopausal hormone therapy] or whether she would prefer to manage symptoms through other means.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the parent KEEPS trial was also supported by the Aurora Foundation. Dr. Cedars, Dr. Asthana, Dr. Santoro, and Dr. Taylor reported grant support and other financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For recently postmenopausal women, oral combined hormone therapy may help with symptoms of depression and anxiety. But hormone therapy did not produce any changes in cognition.

In a large, randomized controlled trial of oral and transdermal estrogens compared with each other and placebo, Carey Gleason, Ph.D., of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues found that exogenous estrogen had no effect on cognitive performance in recently postmenopausal women over a 4-year study period. For women taking low-dose oral conjugated equine estrogens, a small to moderate improvement in some mood symptoms occurred; women receiving estrogen via a transdermal patch did not see this improvement in mood.

The results were published in PLOS Medicine (PLoS. Med. 2015;12:e1001833 [doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833]).

Previous studies had shown mixed findings of the effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cognition, largely depending on whether treatment was initiated early on or later in menopause.

The 693 participants in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study - Cognitive and Affective Study (KEEPS-Cog) were a mean 52.6 years old, and the average time since the last menstrual period was 1.4 years. Enrollees were randomized to one of three study arms where they received either a 0.45 mg/day oral conjugated equine estrogen tablet, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo skin patch; or a 50 microgram/day transdermal estradiol patch, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo tablet; or a placebo tablet, capsule and patch. Treatment lasted for 4 years.

Cognitive status was measured over the 4 years using the Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) exam and an additional battery of cognitive tests that assessed verbal learning, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental and linguistic flexibility. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) was used to evaluate mood. This test, designed to detect specific affective states in nondepressed individuals, assessed levels of tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue, vigor, and confusion-bewilderment.

Dr. Gleason and her colleagues found no improvement in cognitive function with either formulation of menopausal hormone therapy.

“Contrary to our hypothesis, treatment with t-E2 [transdermal estrogen] did not improve cognition in recently postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

For women taking oral estrogen, POMS subscores for tension-anxiety and depression-dejection showed significant improvement over time (for both, P < 0.001). The effect was not seen for transdermal estrogen; Dr. Gleason and her colleagues hypothesized that differences in the formulations of the two products, which resulted in different levels of estradiol versus estrone in participants, may have contributed to the result.

Most of the study’s enrollees were white women with low risk for cardiovascular disease, and most participants had at least a bachelor’s degree, so the generalizability of the KEEPS-Cog findings may be limited. Also, the study’s length and design did not permit assessment of dementia or other clinical diagnoses.

The KEEPS-Cog study, said Dr. Gleason and colleagues, can be incorporated into clinical decision making for women deciding whether to use menopausal hormone therapy. Using these results, a younger woman in good cardiovascular health “can weigh the known risks of [menopausal hormone therapy] against potential benefits for her unique symptom profile, and make an informed decision as to whether she would benefit from [menopausal hormone therapy] or whether she would prefer to manage symptoms through other means.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the parent KEEPS trial was also supported by the Aurora Foundation. Dr. Cedars, Dr. Asthana, Dr. Santoro, and Dr. Taylor reported grant support and other financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For recently postmenopausal women, oral combined hormone therapy may help with symptoms of depression and anxiety. But hormone therapy did not produce any changes in cognition.

In a large, randomized controlled trial of oral and transdermal estrogens compared with each other and placebo, Carey Gleason, Ph.D., of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues found that exogenous estrogen had no effect on cognitive performance in recently postmenopausal women over a 4-year study period. For women taking low-dose oral conjugated equine estrogens, a small to moderate improvement in some mood symptoms occurred; women receiving estrogen via a transdermal patch did not see this improvement in mood.

The results were published in PLOS Medicine (PLoS. Med. 2015;12:e1001833 [doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833]).

Previous studies had shown mixed findings of the effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cognition, largely depending on whether treatment was initiated early on or later in menopause.

The 693 participants in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study - Cognitive and Affective Study (KEEPS-Cog) were a mean 52.6 years old, and the average time since the last menstrual period was 1.4 years. Enrollees were randomized to one of three study arms where they received either a 0.45 mg/day oral conjugated equine estrogen tablet, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo skin patch; or a 50 microgram/day transdermal estradiol patch, 200 mg/day cyclical progesterone capsule, and a placebo tablet; or a placebo tablet, capsule and patch. Treatment lasted for 4 years.

Cognitive status was measured over the 4 years using the Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) exam and an additional battery of cognitive tests that assessed verbal learning, auditory attention and working memory, visual attention and executive function, and mental and linguistic flexibility. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) was used to evaluate mood. This test, designed to detect specific affective states in nondepressed individuals, assessed levels of tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, fatigue, vigor, and confusion-bewilderment.

Dr. Gleason and her colleagues found no improvement in cognitive function with either formulation of menopausal hormone therapy.

“Contrary to our hypothesis, treatment with t-E2 [transdermal estrogen] did not improve cognition in recently postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

For women taking oral estrogen, POMS subscores for tension-anxiety and depression-dejection showed significant improvement over time (for both, P < 0.001). The effect was not seen for transdermal estrogen; Dr. Gleason and her colleagues hypothesized that differences in the formulations of the two products, which resulted in different levels of estradiol versus estrone in participants, may have contributed to the result.

Most of the study’s enrollees were white women with low risk for cardiovascular disease, and most participants had at least a bachelor’s degree, so the generalizability of the KEEPS-Cog findings may be limited. Also, the study’s length and design did not permit assessment of dementia or other clinical diagnoses.

The KEEPS-Cog study, said Dr. Gleason and colleagues, can be incorporated into clinical decision making for women deciding whether to use menopausal hormone therapy. Using these results, a younger woman in good cardiovascular health “can weigh the known risks of [menopausal hormone therapy] against potential benefits for her unique symptom profile, and make an informed decision as to whether she would benefit from [menopausal hormone therapy] or whether she would prefer to manage symptoms through other means.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the parent KEEPS trial was also supported by the Aurora Foundation. Dr. Cedars, Dr. Asthana, Dr. Santoro, and Dr. Taylor reported grant support and other financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Oral combined hormone therapy improved mood in recently postmenopausal women, but did not alter cognition.

Major finding: Oral estrogen therapy, but not transdermal estrogen given in combination with cyclical oral progesterone, provided a small to moderate improvement in mood, but not cognition, when compared with placebo for recently postmenopausal women.

Data source: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 693 recently postmenopausal women; participants drawn from the larger Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS).

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the parent KEEPS trial was also supported by the Aurora Foundation. Dr. Cedars, Dr. Asthana, Dr. Santoro, and Dr. Taylor reported grant support and other financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

2015 Update on menopause

As new options for managing menopausal symptoms emerge, so do data on their efficacy and safety. In this article, I highlight the following publications:

- long-term follow-up data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) on the benefits and risks of hormone therapy (HT)

- a randomized trial of testosterone enanthate to improve sexual function among hysterectomized women

- guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on the management of menopausal symptoms, including advice on individualization of therapy for older women

- a Swedish study on concomitant use of HT and statins.

After long-term follow-up of WHI participants, a “critical window” of HT timing is revealed

Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

After the initial 2002 publication of findings from the WHI trial of women with an intact uterus who were randomized to conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate or placebo, prominent news headlines claimed that HT causes myocardial infarction (MI) and breast cancer. As a result, millions of women worldwide stopped taking HT. A second impact of the report: Many clinicians became reluctant to prescribe HT.

Although it generated far less media attention, an October 2013 publication from the Journal of the American Medical Association, which details 13-year follow-up of WHI HT clinical trial participants, better informs clinicians and our patients about HT’s safety profile.

During the WHI intervention phase, absolute risks were modest

Although HT was associated with a multifaceted pattern of benefits and risks in both the estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT) and estrogen-only therapy (ET) arms of the WHI, absolute risks, as reflected in an increase or decrease in the number of cases per 10,000 women treated per year, were modest.

For example, the hazard ratio (HR) for coronary heart disease (CHD) during the intervention phase, during which participants were given HT or placebo (mean 5.2 years for EPT and 6.8 years for ET) was 1.18 in the EPT arm (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.95–1.45) and 0.94 in the ET arm (95% CI, 0.78–1.14). In both arms, women given HT had reduced risks of vasomotor symptoms, hip fractures, and diabetes, and increased risks of stroke, venous thromboembolism (VTE), and gallbladder disease, compared with women receiving placebo.

The results for breast cancer differed markedly between arms. During the intervention period, an elevated risk was observed with EPT while a borderline reduced risk was observed with ET.

Among participants older than 65 years at baseline, the risk of cognitive decline was increased in the EPT arm but not in the ET arm.

Post intervention, most risks and benefits attenuated

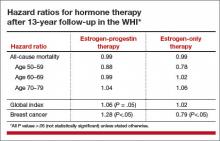

An elevation in the risk of breast cancer persisted in the EPT arm (cumulative HR over 13 years, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.11–1.48). In contrast, in the ET arm, a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer materialized (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65–0.97) (TABLE).

To put into perspective the elevated risk of breast cancer observed among women randomly allocated to EPT, the attributable risk is less than 1 additional case of breast cancer diagnosed per 1,000 EPT users annually. Another way to frame this elevated risk: An HR of 1.28 is slightly higher than the HR conferred by consuming 1 glass of wine daily and lower than the HR noted with 2 glasses daily.1 Overall, results tended to be more favorable for ET than for EPT. Neither type of HT affected overall mortality rates.

Age differences come to the fore

The WHI findings demonstrate a lower absolute risk of adverse events with HT in younger versus older participants. In addition, age and time since menopause appeared to affect many of the HRs observed in the trial. In the ET arm, more favorable results for all-cause mortality, MI, colorectal cancer, and the global index (CHD, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and endometrial cancer) were observed in women aged 50 to 59 years at baseline. In the EPT arm, the risk of MI was elevated only in women more than 10 years past the onset of menopause at baseline. Both HT regimens, however, were associated with increased risks of stroke, VTE, and gallbladder disease.

EPT increased the risk of breast cancer in all age groups. However, the lower absolute risks of adverse events in younger women, together with the generally more favorable HRs for many outcomes in the younger women, resulted in substantially lower rates of adverse events attributable to HT in the younger age group, compared with older women.

As far as CHD is concerned, the impact of age (or time since menopause) on the vascular response to HT in women and in nonhuman models has generated support for a “critical window” or timing hypothesis, which postulates that estrogen reduces the development of early stages of atherosclerosis while causing plaque destabilization and other adverse effects when advanced atherosclerotic lesions are present. Recent studies from Scandinavia provide additional support for this hypothesis (see the sidebar below).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Long-term follow-up of women who participated in the WHI clarifies the benefit-risk profile of systemic HT, underscoring that the benefit-risk ratio is greatest in younger menopausal women.

Because the safety of HT is greater in women nearer the onset of menopause, as well as in those at lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), individualized risk assessment may improve the benefit-risk profile and safety of HT. One approach to decision-making for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms is the MenoPro app, a free mobile app from the North American Menopause Society, with modes for both clinicians and patients.

Further evidence that HT is safe when initiated soon after menopause

Tuomikoski P, Lyytinen H, Korhonen P, et al. Coronary heart disease mortality and hormone therapy before and after the Women’s Health Initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):947–953.

In Finland, all deaths are recorded in a national register, in which particular attention is paid to accurately classifying those thought to result from coronary heart disease (CHD). In addition, since 1994, all HT users have been included in a national health insurance database, enabling detailed assessment of HT use and coronary artery disease. Investigators assessed CHD mortality from 1995 to 2009 in more than 290,000 HT users, comparing them with the background population matched for year and age.

Use of HT was associated with reductions in the CHD mortality rate of 18% to 29% (for ≤1 year of use) and 43% to 54% (for 1–8 years of use). Similar trends were noted for EPT and ET. The HT-associated protection against CHD mortality was more pronounced in users younger than 60.

Tuomikoski and colleagues concluded, and I concur, that the observational nature of their data does not allow us to recommend HT specifically to prevent CHD. Nonetheless, these findings, along with long-term follow-up data from the WHI, make the case that, for menopausal women who are younger than 60 or within 10 years of the onset of menopause, clinicians may consider initiating HT to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms, a safe strategy with respect to CHD.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

In hysterectomized women, supraphysiologic doses of testosterone improve parameters of sexual function

Huang G, Basaria S, Travison TG, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in hysterectomized women with or without oophorectomy: effects on sexual function, body composition, muscle performance, and physical function in a randomized trial. Menopause. 2014;21(6):612–623.

No formulation of testosterone is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in women. Nonetheless, in the United States, many menopausal women hoping to boost their sexual desire are prescribed, off-label, testosterone formulations indicated for use in men, as well as compounded formulations.2

Investigators randomly allocated women who had undergone hysterectomy to 12 weeks of transdermal estradiol followed by 24 weekly intramuscular injections of placebo or testosterone enanthate at doses of 3.0 mg, 6.0 mg, 12.5 mg, or 25.0 mg while continuing estrogen. At the outset of the trial, all women had serum free testosterone levels below the range for healthy premenopausal women.

Among the 62 women who received testosterone, serum testosterone levels increased in a dose-related fashion. Among those allocated to the highest dose, serum total testosterone levels at 24 weeks were 5 to 6 times higher than values in healthy premenopausal women. Compared with women who received placebo, those who received the highest testosterone dose had better measures of sexual desire, arousal, and frequency of sexual activity. Excess hair growth was significantly more common in women who received the 2 highest doses of testosterone.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Although this well-executed study was small and short-term, it confirms that, in menopausal women receiving estrogen, testosterone can enhance parameters of sexuality. It is unfortunate that the dose needed to achieve this benefit results in markedly supraphysiologic serum testosterone levels.

One important caveat raised by this trial: It did not specifically recruit participants with low sexual desire. Therefore, it remains unknown whether lower doses of testosterone might provide benefits in women with low baseline libido. Regrettably, no randomized trials have addressed the long-term benefits and risks of use of testosterone among menopausal women.

ACOG offers valuable guidance on management of menopausal symptoms

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216.

Despite findings from new studies, optimal management of menopausal symptoms remains controversial. In January 2014, ACOG issued guidance regarding conventional systemic and vaginal HT, recently approved treatments, and compounded HT.

For the management of vasomotor symptoms, ACOG indicated that systemic HT (including oral and transdermal routes), alone or combined with a progestin, is the most effective treatment for bothersome menopausal vasomotor symptoms. The ACOG Practice Bulletin also pointed out that systemic EPT increases the risk for VTE and breast cancer and that, compared with oral estrogen, transdermal estrogen may carry a lower risk for VTE.

Some insurers deny coverage of HT for women older than 65 years