User login

Make the Diagnosis - March 2020

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

The patient’s biopsy showed sparse and grouped and slightly enlarged atypical stained mononuclear cells in mostly perifollicular areas with focal epidermotropism. CD30 staining was positive. She responded to potent topical steroids.

The etiology of LyP is unknown. It is unclear whether the proliferation of T-cells is a benign and chronic disorder, or an indolent T-cell malignancy.

In addition, 10% of LyP cases are associated with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), or Hodgkin lymphoma. Borderline cases are those that overlap LyP and lymphoma.

Patients typically present with crops of asymptomatic erythematous to brown papules that may become pustular, vesicular, or necrotic. Lesions tend to resolve within 2-8 weeks with or without scarring. The trunk and extremities are commonly affected. The condition tends to be chronic over months to years. The waxing and waning course is characteristic of LyP. Constitutional symptoms are generally absent in cases not associated with systemic disease.

Histopathologic examination reveals a dense wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes along with numerous eosinophils and neutrophils. Epidermotropism may be present and lymphocytes stain positive for CD30+. Vessels in the dermis may exhibit fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation. Histologically, LyP can be classified as Type A to E. These subtypes are determined by the size and type of atypical cells, location and amount of infiltrate, and staining of CD30 and CD8.

The differential diagnosis of LyP includes pityriasis lichenoides, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, folliculitis, arthropod assault, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and leukemia cutis. Treatment is symptomatic. Mild forms of LyP can many times be managed with superpotent topical corticosteroids. Bexarotene gel has been used for early lesions. For more widespread or persistent disease, intralesional corticosteroids, phototherapy (UVB or PUVA), tetracycline antibiotics, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective. Refractory cases may respond to interferon alpha or oral bexarotene. Routine evaluations are recommended as patients may be at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

FDA approves first treatment for advanced epithelioid sarcoma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to tazemetostat (Tazverik) for the treatment of adults and pediatric patients aged 16 years and older with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma not eligible for complete resection.

Approval was based on overall response rate in a trial enrolling 62 patients with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma. The overall response rate was 15%, with 1.6% of patients having a complete response and 13% having a partial response. Of the nine patients that had a response, six (67%) had a response lasting 6 months or longer, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most common side effects for patients taking tazemetostat were pain, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, vomiting, and constipation. Patients treated with tazemetostat are at increased risk of developing secondary malignancies, including T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute myeloid leukemia.

“Epithelioid sarcoma accounts for less than 1% of all soft-tissue sarcomas,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Oncologic Diseases in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Until today, there were no treatment options specifically for patients with epithelioid sarcoma. The approval of Tazverik provides a treatment option that specifically targets this disease.”

Tazemetostat must be dispensed with a patient medication guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks, the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to tazemetostat (Tazverik) for the treatment of adults and pediatric patients aged 16 years and older with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma not eligible for complete resection.

Approval was based on overall response rate in a trial enrolling 62 patients with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma. The overall response rate was 15%, with 1.6% of patients having a complete response and 13% having a partial response. Of the nine patients that had a response, six (67%) had a response lasting 6 months or longer, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most common side effects for patients taking tazemetostat were pain, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, vomiting, and constipation. Patients treated with tazemetostat are at increased risk of developing secondary malignancies, including T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute myeloid leukemia.

“Epithelioid sarcoma accounts for less than 1% of all soft-tissue sarcomas,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Oncologic Diseases in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Until today, there were no treatment options specifically for patients with epithelioid sarcoma. The approval of Tazverik provides a treatment option that specifically targets this disease.”

Tazemetostat must be dispensed with a patient medication guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks, the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to tazemetostat (Tazverik) for the treatment of adults and pediatric patients aged 16 years and older with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma not eligible for complete resection.

Approval was based on overall response rate in a trial enrolling 62 patients with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma. The overall response rate was 15%, with 1.6% of patients having a complete response and 13% having a partial response. Of the nine patients that had a response, six (67%) had a response lasting 6 months or longer, the FDA said in a press statement.

The most common side effects for patients taking tazemetostat were pain, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, vomiting, and constipation. Patients treated with tazemetostat are at increased risk of developing secondary malignancies, including T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, and acute myeloid leukemia.

“Epithelioid sarcoma accounts for less than 1% of all soft-tissue sarcomas,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Oncologic Diseases in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “Until today, there were no treatment options specifically for patients with epithelioid sarcoma. The approval of Tazverik provides a treatment option that specifically targets this disease.”

Tazemetostat must be dispensed with a patient medication guide that describes important information about the drug’s uses and risks, the FDA said.

February 2020

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a type of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may occur independently of or in combination with systemic lupus erythematosus. About 10%-15% of patients with SCLE will develop systemic lupus erythematosus. White females are more typically affected.

SCLE lesions often present as scaly, annular, or polycyclic scaly patches and plaques with central clearing. They may appear psoriasiform. They heal without atrophy or scarring but may leave dyspigmentation. Follicular plugging is absent. Lesions generally occur on sun exposed areas such as the neck, V of the chest, and upper extremities. Up to 75% of patients may exhibit associated symptoms such as photosensitivity, oral ulcers, and arthritis. Less than 20% of patients will develop internal disease, including nephritis and pulmonary disease. Symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and SCLE may overlap in some patients, and will portend higher risk for internal disease.

The differential diagnosis includes eczema, psoriasis, dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Histology reveals epidermal atrophy and keratinocyte apoptosis, with a superficial and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis. Interface changes at the dermal-epidermal junction can be seen. Direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin is positive in one-third of cases, often revealing granular deposits of IgG and IgM at the dermal-epidermal junction and around hair follicles (called the lupus-band test). Serology in SCLE may reveal a positive antinuclear antigen test, as well as positive Ro/SSA antigen. Other lupus serologies such as La/SSB, dsDNA, antihistone, and Sm antibodies may be positive, but are less commonly seen.

Several drugs may cause SCLE, such as hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, calcium-channel blockers, interferons, anticonvulsants, griseofulvin, penicillamine, spironolactone, tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors, and statins. Discontinuing the offending medications may clear the lesions, but not always.

Treatment includes sunscreen and avoidance of sun exposure. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. If systemic treatment is indicated, antimalarials are first line.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Celebrating 50 years of Dermatology News

The first issue of Skin & Allergy News, now Dermatology News, was published in January 1970. One front-page story highlighted the "continued improvement and more widespread use of steroids" as the most important development of the 1960s in dermatology. Another covered the launch of a national program for dermatology "to design a pattern for its future instead of simply drifting and letting its fate be determined by others."

Throughout 2020, look for articles and features marking the publication's golden anniversary. And read the first ever issue in the PDF above.

The first issue of Skin & Allergy News, now Dermatology News, was published in January 1970. One front-page story highlighted the "continued improvement and more widespread use of steroids" as the most important development of the 1960s in dermatology. Another covered the launch of a national program for dermatology "to design a pattern for its future instead of simply drifting and letting its fate be determined by others."

Throughout 2020, look for articles and features marking the publication's golden anniversary. And read the first ever issue in the PDF above.

The first issue of Skin & Allergy News, now Dermatology News, was published in January 1970. One front-page story highlighted the "continued improvement and more widespread use of steroids" as the most important development of the 1960s in dermatology. Another covered the launch of a national program for dermatology "to design a pattern for its future instead of simply drifting and letting its fate be determined by others."

Throughout 2020, look for articles and features marking the publication's golden anniversary. And read the first ever issue in the PDF above.

Common drug with lots of surprising side effects

A 55-year-old woman comes to clinic for follow-up. She reports her family is worried that she isn’t getting enough sleep and is more tired than usual. The patient reports she is sleeping 8 hours a night and wakes up feeling rested, but she has noticed she has been yawning much more frequently than she remembers in the past.

Past medical history: gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, generalized anxiety disorder, hypothyroidism, and osteoporosis. Medications: amlodipine, lansoprazole, irbesartan, escitalopram, levothyroxine, and alendronate. Physical examination: blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg, pulse 60 bpm. Lower extremities: 1+ edema.

What is the likely cause of her increased yawning?

A. Amlodipine.

B. Alendronate.

C. Irbesartan.

D. Escitalopram.

E. Lansoprazole.

The correct answer here is escitalopram. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in general are well tolerated. Given how commonly these drugs are used, however, there are a number of lesser-known side effects that you are likely to see.

In the above case, this patient has yawning caused by her SSRI. Roncero et al. described a case of yawning in a patient on escitalopram that resolved when the dose of escitalopram was reduced.1 Paroxetine has been reported to cause yawning at both low and high doses.2

In a review of drug-induced yawning, SSRIs as a class were most frequently involved, and sertraline and fluoxetine were implicated in addition to paroxetine.3 The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine have also been associated with yawning.4,5

Hyperhydrosis has also been linked to SSRIs and SNRIs, and both yawning and hyperhidrosis may occur because of an underlying thermoregulatory dysfunction.6

SSRIs have been linked to increased bleeding risk, especially increased risk of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Laporte and colleagues showed an association of SSRI use and risk of bleeding in a meta-analysis of 42 observational studies, with an odds ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-1.57; P less than .0001).7 The risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is further increased if patients are also taking NSAIDs.

Anglin et al. looked at 15 case-control studies and 4 cohort studies and found an OR of 1.66 for UGI bleeding with SSRI use, and an OR of 4.25 for UGI bleeding if SSRI use was combined with NSAID use.8 The number needed to harm is 3,177 for NSAID use in populations at low risk for GI bleeding, but it is much lower (881) in higher-risk populations.8 Make sure to think about patients’ bleeding risks when starting SSRIs.

An issue that comes up frequently is: What is the risk of bleeding in patients on SSRIs who are also on anticoagulants? Dr. Quinn and colleagues looked at the bleeding risk of anticoagulated patients also taking SSRIs in the ROCKET AF trial.9 They found 737 patients who received SSRIs and matched them with other patients not on SSRIs in the trial. All patients in the trial were either receiving rivaroxaban or warfarin for stroke prophylaxis. They found no significant increase risk in bleeding in the patients on SSRIs and anticoagulants.

Take-home points:

- Yawning and hyperhidrosis are interesting side effects of SSRIs.

- Bleeding risk is increased in patients on SSRIs, especially when combined with NSAIDs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Neurologia. 2013 Nov-Dec;28(9):589-90.

2. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Apr;60(2):260.

3. Presse Med. 2014 Oct;43(10 Pt 1):1135-6.

4. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 15;33(4):747.

5. Ann Pharmacother. 2011 Oct;45(10):1297-301.

6. Depress Anxiety. 2017 Dec;34(12):1134-46.

7. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Apr;118:19-32.

8. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jun;109(6):811-9.

9. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Aug 7;7(15):e008755.

A 55-year-old woman comes to clinic for follow-up. She reports her family is worried that she isn’t getting enough sleep and is more tired than usual. The patient reports she is sleeping 8 hours a night and wakes up feeling rested, but she has noticed she has been yawning much more frequently than she remembers in the past.

Past medical history: gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, generalized anxiety disorder, hypothyroidism, and osteoporosis. Medications: amlodipine, lansoprazole, irbesartan, escitalopram, levothyroxine, and alendronate. Physical examination: blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg, pulse 60 bpm. Lower extremities: 1+ edema.

What is the likely cause of her increased yawning?

A. Amlodipine.

B. Alendronate.

C. Irbesartan.

D. Escitalopram.

E. Lansoprazole.

The correct answer here is escitalopram. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in general are well tolerated. Given how commonly these drugs are used, however, there are a number of lesser-known side effects that you are likely to see.

In the above case, this patient has yawning caused by her SSRI. Roncero et al. described a case of yawning in a patient on escitalopram that resolved when the dose of escitalopram was reduced.1 Paroxetine has been reported to cause yawning at both low and high doses.2

In a review of drug-induced yawning, SSRIs as a class were most frequently involved, and sertraline and fluoxetine were implicated in addition to paroxetine.3 The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine have also been associated with yawning.4,5

Hyperhydrosis has also been linked to SSRIs and SNRIs, and both yawning and hyperhidrosis may occur because of an underlying thermoregulatory dysfunction.6

SSRIs have been linked to increased bleeding risk, especially increased risk of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Laporte and colleagues showed an association of SSRI use and risk of bleeding in a meta-analysis of 42 observational studies, with an odds ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-1.57; P less than .0001).7 The risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is further increased if patients are also taking NSAIDs.

Anglin et al. looked at 15 case-control studies and 4 cohort studies and found an OR of 1.66 for UGI bleeding with SSRI use, and an OR of 4.25 for UGI bleeding if SSRI use was combined with NSAID use.8 The number needed to harm is 3,177 for NSAID use in populations at low risk for GI bleeding, but it is much lower (881) in higher-risk populations.8 Make sure to think about patients’ bleeding risks when starting SSRIs.

An issue that comes up frequently is: What is the risk of bleeding in patients on SSRIs who are also on anticoagulants? Dr. Quinn and colleagues looked at the bleeding risk of anticoagulated patients also taking SSRIs in the ROCKET AF trial.9 They found 737 patients who received SSRIs and matched them with other patients not on SSRIs in the trial. All patients in the trial were either receiving rivaroxaban or warfarin for stroke prophylaxis. They found no significant increase risk in bleeding in the patients on SSRIs and anticoagulants.

Take-home points:

- Yawning and hyperhidrosis are interesting side effects of SSRIs.

- Bleeding risk is increased in patients on SSRIs, especially when combined with NSAIDs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Neurologia. 2013 Nov-Dec;28(9):589-90.

2. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Apr;60(2):260.

3. Presse Med. 2014 Oct;43(10 Pt 1):1135-6.

4. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 15;33(4):747.

5. Ann Pharmacother. 2011 Oct;45(10):1297-301.

6. Depress Anxiety. 2017 Dec;34(12):1134-46.

7. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Apr;118:19-32.

8. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jun;109(6):811-9.

9. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Aug 7;7(15):e008755.

A 55-year-old woman comes to clinic for follow-up. She reports her family is worried that she isn’t getting enough sleep and is more tired than usual. The patient reports she is sleeping 8 hours a night and wakes up feeling rested, but she has noticed she has been yawning much more frequently than she remembers in the past.

Past medical history: gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, generalized anxiety disorder, hypothyroidism, and osteoporosis. Medications: amlodipine, lansoprazole, irbesartan, escitalopram, levothyroxine, and alendronate. Physical examination: blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg, pulse 60 bpm. Lower extremities: 1+ edema.

What is the likely cause of her increased yawning?

A. Amlodipine.

B. Alendronate.

C. Irbesartan.

D. Escitalopram.

E. Lansoprazole.

The correct answer here is escitalopram. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in general are well tolerated. Given how commonly these drugs are used, however, there are a number of lesser-known side effects that you are likely to see.

In the above case, this patient has yawning caused by her SSRI. Roncero et al. described a case of yawning in a patient on escitalopram that resolved when the dose of escitalopram was reduced.1 Paroxetine has been reported to cause yawning at both low and high doses.2

In a review of drug-induced yawning, SSRIs as a class were most frequently involved, and sertraline and fluoxetine were implicated in addition to paroxetine.3 The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and venlafaxine have also been associated with yawning.4,5

Hyperhydrosis has also been linked to SSRIs and SNRIs, and both yawning and hyperhidrosis may occur because of an underlying thermoregulatory dysfunction.6

SSRIs have been linked to increased bleeding risk, especially increased risk of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Laporte and colleagues showed an association of SSRI use and risk of bleeding in a meta-analysis of 42 observational studies, with an odds ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval, 1.27-1.57; P less than .0001).7 The risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is further increased if patients are also taking NSAIDs.

Anglin et al. looked at 15 case-control studies and 4 cohort studies and found an OR of 1.66 for UGI bleeding with SSRI use, and an OR of 4.25 for UGI bleeding if SSRI use was combined with NSAID use.8 The number needed to harm is 3,177 for NSAID use in populations at low risk for GI bleeding, but it is much lower (881) in higher-risk populations.8 Make sure to think about patients’ bleeding risks when starting SSRIs.

An issue that comes up frequently is: What is the risk of bleeding in patients on SSRIs who are also on anticoagulants? Dr. Quinn and colleagues looked at the bleeding risk of anticoagulated patients also taking SSRIs in the ROCKET AF trial.9 They found 737 patients who received SSRIs and matched them with other patients not on SSRIs in the trial. All patients in the trial were either receiving rivaroxaban or warfarin for stroke prophylaxis. They found no significant increase risk in bleeding in the patients on SSRIs and anticoagulants.

Take-home points:

- Yawning and hyperhidrosis are interesting side effects of SSRIs.

- Bleeding risk is increased in patients on SSRIs, especially when combined with NSAIDs.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Neurologia. 2013 Nov-Dec;28(9):589-90.

2. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Apr;60(2):260.

3. Presse Med. 2014 Oct;43(10 Pt 1):1135-6.

4. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 15;33(4):747.

5. Ann Pharmacother. 2011 Oct;45(10):1297-301.

6. Depress Anxiety. 2017 Dec;34(12):1134-46.

7. Pharmacol Res. 2017 Apr;118:19-32.

8. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jun;109(6):811-9.

9. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018 Aug 7;7(15):e008755.

Recognize early window of opportunity in hidradenitis suppurativa

MADRID – Antonio Martorell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This distinction is critical in recognizing a window of opportunity in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): The period early in the disease course when medical therapy alone can be life-changing.

“The window of opportunity is an old concept in gastroenterology, but it’s a new idea in dermatology: It’s the moment in which the patient can have the best results with medical control of inflammation, before progression to tissue scarring has occurred,” explained Dr. Martorell, a dermatologist at the Hospital of Manises in Valencia, Spain, and coauthor of recent HS treatment recommendations by an international expert panel (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jan;33[1]:19-31).

Symptoms in patients with HS can be caused by either dynamic or static lesions. Dynamic lesions arise directly from acute inflammation that can be treated with antibiotics and immunomodulatory therapy. Static lesions are associated with tissue scarring secondary to inflammatory activity and generally benefit only from surgery.

Dynamic lesions consist of nodules, abscesses, and some but not all fistulae. Although the traditional view among dermatologists has been that fistulae simply don’t respond to medical therapy and must be treated surgically, Dr. Martorell and coinvestigators have recently demonstrated in a retrospective study of 117 fistulae in 40 patients that ultrasound was useful in distinguishing four fistular subtypes, two of which responded reasonably well to medical management.

What the investigators call Type A or dermal fistulae are by definition not connected to tunnels. In Dr. Martorell’s study, they had a 95% complete resolution rate after 6 months of various medications. Dermoepidermal fistulae tunnel through the dermis to the epidermis; they had a 65% complete resolution rate. In contrast, Type C or complex fistulae, identified by the ultrasound finding of multiple tunnels extending through the dermis into underlying fat tissue, had no significant response to medical management. Neither did Type D fistulae, which are essentially Type C lesions with scarring (Dermatol Surg. 2019 Oct;45[10]:1237-44).

Thus, ultrasound can have an important impact on patient management and the decision to opt for a combined medical/surgical approach.

“It’s important to apply the HS severity scores and complete the clinical exam, but it’s also important to use ultrasound or another imaging technique,” Dr. Martorell concluded.

MADRID – Antonio Martorell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This distinction is critical in recognizing a window of opportunity in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): The period early in the disease course when medical therapy alone can be life-changing.

“The window of opportunity is an old concept in gastroenterology, but it’s a new idea in dermatology: It’s the moment in which the patient can have the best results with medical control of inflammation, before progression to tissue scarring has occurred,” explained Dr. Martorell, a dermatologist at the Hospital of Manises in Valencia, Spain, and coauthor of recent HS treatment recommendations by an international expert panel (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jan;33[1]:19-31).

Symptoms in patients with HS can be caused by either dynamic or static lesions. Dynamic lesions arise directly from acute inflammation that can be treated with antibiotics and immunomodulatory therapy. Static lesions are associated with tissue scarring secondary to inflammatory activity and generally benefit only from surgery.

Dynamic lesions consist of nodules, abscesses, and some but not all fistulae. Although the traditional view among dermatologists has been that fistulae simply don’t respond to medical therapy and must be treated surgically, Dr. Martorell and coinvestigators have recently demonstrated in a retrospective study of 117 fistulae in 40 patients that ultrasound was useful in distinguishing four fistular subtypes, two of which responded reasonably well to medical management.

What the investigators call Type A or dermal fistulae are by definition not connected to tunnels. In Dr. Martorell’s study, they had a 95% complete resolution rate after 6 months of various medications. Dermoepidermal fistulae tunnel through the dermis to the epidermis; they had a 65% complete resolution rate. In contrast, Type C or complex fistulae, identified by the ultrasound finding of multiple tunnels extending through the dermis into underlying fat tissue, had no significant response to medical management. Neither did Type D fistulae, which are essentially Type C lesions with scarring (Dermatol Surg. 2019 Oct;45[10]:1237-44).

Thus, ultrasound can have an important impact on patient management and the decision to opt for a combined medical/surgical approach.

“It’s important to apply the HS severity scores and complete the clinical exam, but it’s also important to use ultrasound or another imaging technique,” Dr. Martorell concluded.

MADRID – Antonio Martorell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This distinction is critical in recognizing a window of opportunity in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): The period early in the disease course when medical therapy alone can be life-changing.

“The window of opportunity is an old concept in gastroenterology, but it’s a new idea in dermatology: It’s the moment in which the patient can have the best results with medical control of inflammation, before progression to tissue scarring has occurred,” explained Dr. Martorell, a dermatologist at the Hospital of Manises in Valencia, Spain, and coauthor of recent HS treatment recommendations by an international expert panel (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jan;33[1]:19-31).

Symptoms in patients with HS can be caused by either dynamic or static lesions. Dynamic lesions arise directly from acute inflammation that can be treated with antibiotics and immunomodulatory therapy. Static lesions are associated with tissue scarring secondary to inflammatory activity and generally benefit only from surgery.

Dynamic lesions consist of nodules, abscesses, and some but not all fistulae. Although the traditional view among dermatologists has been that fistulae simply don’t respond to medical therapy and must be treated surgically, Dr. Martorell and coinvestigators have recently demonstrated in a retrospective study of 117 fistulae in 40 patients that ultrasound was useful in distinguishing four fistular subtypes, two of which responded reasonably well to medical management.

What the investigators call Type A or dermal fistulae are by definition not connected to tunnels. In Dr. Martorell’s study, they had a 95% complete resolution rate after 6 months of various medications. Dermoepidermal fistulae tunnel through the dermis to the epidermis; they had a 65% complete resolution rate. In contrast, Type C or complex fistulae, identified by the ultrasound finding of multiple tunnels extending through the dermis into underlying fat tissue, had no significant response to medical management. Neither did Type D fistulae, which are essentially Type C lesions with scarring (Dermatol Surg. 2019 Oct;45[10]:1237-44).

Thus, ultrasound can have an important impact on patient management and the decision to opt for a combined medical/surgical approach.

“It’s important to apply the HS severity scores and complete the clinical exam, but it’s also important to use ultrasound or another imaging technique,” Dr. Martorell concluded.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Oral lichen planus prevalence estimates go global

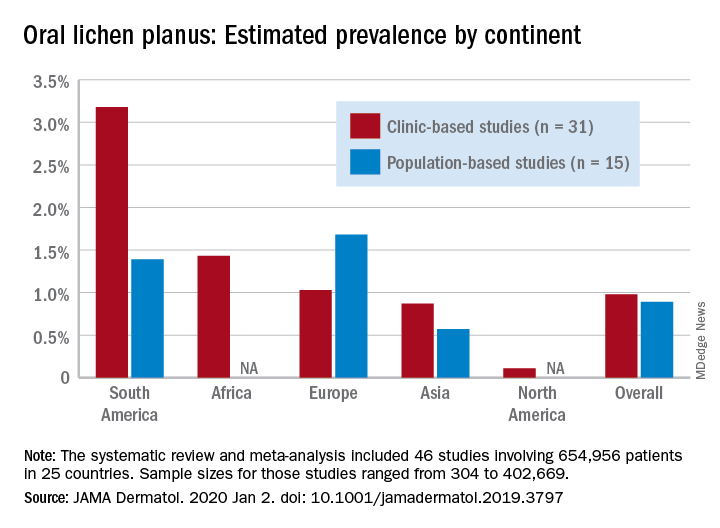

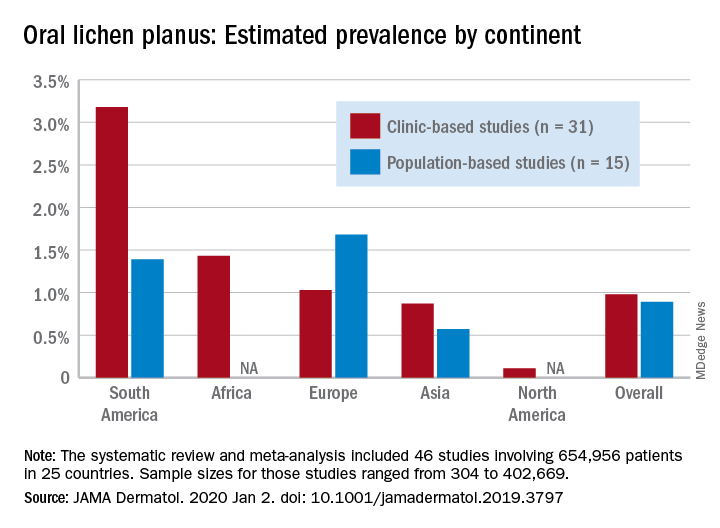

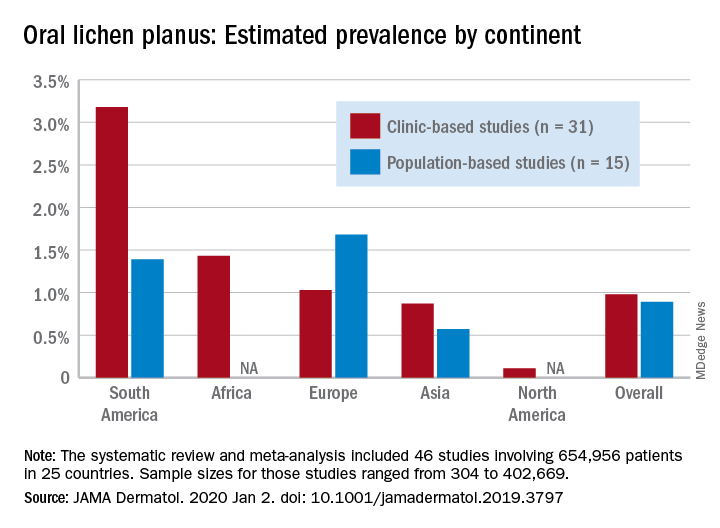

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

for the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.

Globally, oral lichen planus (OLP) appears to be more prevalent in women than men (1.55% vs. 1.11% in population-based studies; 1.69% vs. 1.09% in clinic-based), in those aged 40 years and older (1.90% vs. 0.62% in clinic-based studies), and in non-Asian countries (see graph), Changchang Li, MD, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Of the 25 countries represented among the 46 included studies, Brazil had the highest OLP prevalence at 6.04% and India had the lowest at 0.02%. “Smokers and patients who abuse alcohol have a higher prevalence of OLP. This factor may explain why the highest prevalence … was found in Brazil, where 18.18% of residents report being smokers and 29.09% report consumption of alcoholic beverages,” wrote Dr. Li of the department of dermatology at Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Wenzhou, China, and associates.

The difference in OLP prevalence by sex may be related to fluctuating female hormone levels, “especially during menstruation or menopause, and that different social roles may lead to the body being in a state of stress,” the investigators suggested.

The age-related difference in OLP could be the result of “longstanding oral habits” or changes to the oral mucosa over time, such as mucosal thinning, decreased elasticity, less saliva secretion, and greater tissue permeability. The higher prevalence among those aged 40 years and older also may be “associated with metabolic changes during aging or with decreased immunity, nutritional deficiencies, medication use, or denture wear,” they wrote.

The review and meta-analysis involved 15 studies (n = 462,993) that included general population data and 31 (n = 191,963) that used information from clinical patients. Sample sizes for those studies ranged from 308 to 402,669.

Statistically significant publication bias was seen among the clinic-based studies but not those that were population based, Dr. Li and associates wrote, adding that “our findings should be considered with caution because of the high heterogeneity of the included studies.”

The study was funded by the First-Class Discipline Construction Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, the Young Top Talent Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation in Special Support Plan for Training High-level Talents, and the Youth Research and Cultivation Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: C Li et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3797.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Oral BTK inhibitor shows continued promise for pemphigus

MADRID – A novel Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In pemphigus, we have a considerable unmet medical need. We could do with a treatment that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing or avoiding, safe for chronic administration, avoids chronic B cell depletion – which is an issue with rituxumab – is efficacious in both newly diagnosed as well as in our commonly relapsing patients, and is convenient to administer,” observed Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

In the phase 2 BELIEVE trial, the BTK inhibitor known for now only as PRN1008 appeared to check all the boxes. However, definitive evidence of the drug’s efficacy and safety must await the results of the ongoing, double-bind, placebo-controlled, pivotal phase 3 PEGASUS trial, which is enrolling a planned 120 patients with pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in 19 countries.

Pemphigus is driven by autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Even in contemporary practice, this blistering disease has roughly a 5% mortality rate. Current management of the disease with high-dose corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg per day or more with or without rituximab (Rituxan) is challenging because of the associated pronounced toxicities. And even when rituximab is utilized, patients need to be on high-dose steroids for at least 3-6 months before a rituximab response is achieved, Dr. Murrell said.

PRN1008 has three mechanisms of action targeting the drivers of pemphigus and other immune-mediated diseases, she explained. The drug blocks inflammatory B cells, neutrophils, and macrophages; eliminates downstream signalling by antidesmoglein autoantibodies; and prevents production of new autoantibodies. The drug has a double lock-and-key mechanism which makes it highly specific for its target, so treated patients are much less likely to experience bruising, diarrhea, and other off-target effects than is the case with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

“Also, PRN1008 is reversible. It comes off its target receptor after about 12 hours, at which point serum levels become low. So if any side effects do develop, the patient can recover quickly, unlike with rituximab, which involves ongoing inhibition of B cells for a long period of time,” the dermatologist noted.

BELIEVE was a phase 2 dose-ranging study of 27 patients with pemphigus treated open-label with PRN1008 for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, meaning no new lesions while established lesions showed some evidence of healing on no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. This outcome was achieved in 27% of participants at 2 weeks, 54% at 4 weeks, and 73% at 12 weeks. Autoantibody levels dropped by a mean of 65% at 12 weeks, with a median 70% reduction in Pemphigus Disease Activity Index scores while patients were on an average of just 12 mg of prednisone per day.

Phase 2b of BELIEVE included a separate group of 15 patients on PRN1008 for 24 weeks. Nine achieved a Pemphigus Disease Activity Index score of 0 or 1. Six patients had a complete response, meaning an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone. Another five patients were unable to achieve a complete response, and the jury was still out on another four still on treatment.

The side effect profile was benign in comparison with that of current standard therapies, she said. It consisted of a handful of cases of mild, transient nausea, headache, or upper abdominal pain and a few Grade 1 infections. There have been no severe treatment-related adverse events in BELIEVE participants.

Patients enrolled in the ongoing phase 3 PEGASUS trial start with a short course of high-dose corticosteroids, followed by double-blind randomization to PRN1008 at 400 mg twice a day or placebo, with a corticosteroid taper. The primary endpoint is durable complete remission at week 37, defined as no lesions being present for at least the previous 8 weeks while on no more than 5 mg/day of prednisone.

Secondary endpoints include cumulative corticosteroid dose through 36 weeks and patient-reported quality of life measures assessed out to 61 weeks. The trial is scheduled for completion in the spring of 2022.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to the study sponsor, Principia Biopharma, as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MADRID – A novel Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In pemphigus, we have a considerable unmet medical need. We could do with a treatment that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing or avoiding, safe for chronic administration, avoids chronic B cell depletion – which is an issue with rituxumab – is efficacious in both newly diagnosed as well as in our commonly relapsing patients, and is convenient to administer,” observed Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

In the phase 2 BELIEVE trial, the BTK inhibitor known for now only as PRN1008 appeared to check all the boxes. However, definitive evidence of the drug’s efficacy and safety must await the results of the ongoing, double-bind, placebo-controlled, pivotal phase 3 PEGASUS trial, which is enrolling a planned 120 patients with pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in 19 countries.

Pemphigus is driven by autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Even in contemporary practice, this blistering disease has roughly a 5% mortality rate. Current management of the disease with high-dose corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg per day or more with or without rituximab (Rituxan) is challenging because of the associated pronounced toxicities. And even when rituximab is utilized, patients need to be on high-dose steroids for at least 3-6 months before a rituximab response is achieved, Dr. Murrell said.

PRN1008 has three mechanisms of action targeting the drivers of pemphigus and other immune-mediated diseases, she explained. The drug blocks inflammatory B cells, neutrophils, and macrophages; eliminates downstream signalling by antidesmoglein autoantibodies; and prevents production of new autoantibodies. The drug has a double lock-and-key mechanism which makes it highly specific for its target, so treated patients are much less likely to experience bruising, diarrhea, and other off-target effects than is the case with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

“Also, PRN1008 is reversible. It comes off its target receptor after about 12 hours, at which point serum levels become low. So if any side effects do develop, the patient can recover quickly, unlike with rituximab, which involves ongoing inhibition of B cells for a long period of time,” the dermatologist noted.

BELIEVE was a phase 2 dose-ranging study of 27 patients with pemphigus treated open-label with PRN1008 for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, meaning no new lesions while established lesions showed some evidence of healing on no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. This outcome was achieved in 27% of participants at 2 weeks, 54% at 4 weeks, and 73% at 12 weeks. Autoantibody levels dropped by a mean of 65% at 12 weeks, with a median 70% reduction in Pemphigus Disease Activity Index scores while patients were on an average of just 12 mg of prednisone per day.

Phase 2b of BELIEVE included a separate group of 15 patients on PRN1008 for 24 weeks. Nine achieved a Pemphigus Disease Activity Index score of 0 or 1. Six patients had a complete response, meaning an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone. Another five patients were unable to achieve a complete response, and the jury was still out on another four still on treatment.

The side effect profile was benign in comparison with that of current standard therapies, she said. It consisted of a handful of cases of mild, transient nausea, headache, or upper abdominal pain and a few Grade 1 infections. There have been no severe treatment-related adverse events in BELIEVE participants.

Patients enrolled in the ongoing phase 3 PEGASUS trial start with a short course of high-dose corticosteroids, followed by double-blind randomization to PRN1008 at 400 mg twice a day or placebo, with a corticosteroid taper. The primary endpoint is durable complete remission at week 37, defined as no lesions being present for at least the previous 8 weeks while on no more than 5 mg/day of prednisone.

Secondary endpoints include cumulative corticosteroid dose through 36 weeks and patient-reported quality of life measures assessed out to 61 weeks. The trial is scheduled for completion in the spring of 2022.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to the study sponsor, Principia Biopharma, as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MADRID – A novel Dedee F. Murrell, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“In pemphigus, we have a considerable unmet medical need. We could do with a treatment that has rapid onset, is steroid sparing or avoiding, safe for chronic administration, avoids chronic B cell depletion – which is an issue with rituxumab – is efficacious in both newly diagnosed as well as in our commonly relapsing patients, and is convenient to administer,” observed Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

In the phase 2 BELIEVE trial, the BTK inhibitor known for now only as PRN1008 appeared to check all the boxes. However, definitive evidence of the drug’s efficacy and safety must await the results of the ongoing, double-bind, placebo-controlled, pivotal phase 3 PEGASUS trial, which is enrolling a planned 120 patients with pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus in 19 countries.

Pemphigus is driven by autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Even in contemporary practice, this blistering disease has roughly a 5% mortality rate. Current management of the disease with high-dose corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg per day or more with or without rituximab (Rituxan) is challenging because of the associated pronounced toxicities. And even when rituximab is utilized, patients need to be on high-dose steroids for at least 3-6 months before a rituximab response is achieved, Dr. Murrell said.

PRN1008 has three mechanisms of action targeting the drivers of pemphigus and other immune-mediated diseases, she explained. The drug blocks inflammatory B cells, neutrophils, and macrophages; eliminates downstream signalling by antidesmoglein autoantibodies; and prevents production of new autoantibodies. The drug has a double lock-and-key mechanism which makes it highly specific for its target, so treated patients are much less likely to experience bruising, diarrhea, and other off-target effects than is the case with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

“Also, PRN1008 is reversible. It comes off its target receptor after about 12 hours, at which point serum levels become low. So if any side effects do develop, the patient can recover quickly, unlike with rituximab, which involves ongoing inhibition of B cells for a long period of time,” the dermatologist noted.

BELIEVE was a phase 2 dose-ranging study of 27 patients with pemphigus treated open-label with PRN1008 for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was control of disease activity, meaning no new lesions while established lesions showed some evidence of healing on no more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone. This outcome was achieved in 27% of participants at 2 weeks, 54% at 4 weeks, and 73% at 12 weeks. Autoantibody levels dropped by a mean of 65% at 12 weeks, with a median 70% reduction in Pemphigus Disease Activity Index scores while patients were on an average of just 12 mg of prednisone per day.

Phase 2b of BELIEVE included a separate group of 15 patients on PRN1008 for 24 weeks. Nine achieved a Pemphigus Disease Activity Index score of 0 or 1. Six patients had a complete response, meaning an absence of both new and established lesions while on no or a very low dose of prednisone. Another five patients were unable to achieve a complete response, and the jury was still out on another four still on treatment.

The side effect profile was benign in comparison with that of current standard therapies, she said. It consisted of a handful of cases of mild, transient nausea, headache, or upper abdominal pain and a few Grade 1 infections. There have been no severe treatment-related adverse events in BELIEVE participants.

Patients enrolled in the ongoing phase 3 PEGASUS trial start with a short course of high-dose corticosteroids, followed by double-blind randomization to PRN1008 at 400 mg twice a day or placebo, with a corticosteroid taper. The primary endpoint is durable complete remission at week 37, defined as no lesions being present for at least the previous 8 weeks while on no more than 5 mg/day of prednisone.

Secondary endpoints include cumulative corticosteroid dose through 36 weeks and patient-reported quality of life measures assessed out to 61 weeks. The trial is scheduled for completion in the spring of 2022.

Dr. Murrell reported serving as a consultant to the study sponsor, Principia Biopharma, as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

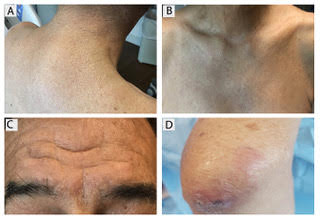

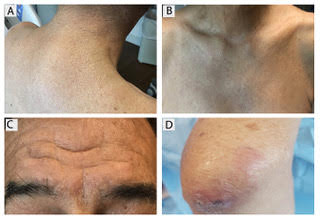

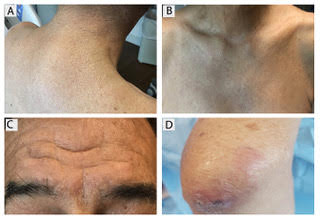

Progressive, pruritic eruption of firm, skin-colored papules

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Scleromyxedema, or generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a primary cutaneous mucinosis with unknown pathogenesis characterized by generalized firm, skin-colored papules and is commonly associated with an underlying monoclonal gammopathy (usually Ig-gamma paraproteinemia).

Scleromyxedema may have associated internal involvement, including neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, ophthalmological, or musculoskeletal. Histopathology demonstrates mucin in the dermis seen with Alcian blue staining, proliferation of fibroblasts, and increased collagen deposition.

The condition is chronic and progressive. Intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line treatment. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been reported to also be efficacious.

It is associated with hematologic disorders, including IgA monoclonal gammopathy, as well as myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, infections, and inflammatory bowel disease. Although its pathophysiology is not well understood, vascular immune complex deposition, repetitive inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis may play a role. On histology, there is leukocytoclastic vasculitis with polymorphonuclear cell infiltrate and fibrin deposition in the superficial and mid-dermis and onion-skin fibrosis.

EED often self-resolves within 5-10 years, although it can become chronic and recurrent. Dapsone, niacinamide, antimalarials, NSAIDs, tetracyclines, corticosteroids, colchicine, and plasmapheresis are reported treatments. This patient’s EED was recalcitrant to prednisone and responded to colchicine.

Scleromyxedema and EED are both rare, distinct cutaneous entities associated with different underlying paraproteinemias and to the best of our knowledge, have not been previously reported to coexist in a single patient.

This case and the photos were submitted by Rachel Fayne, BA; Yumeng Li, MD, MS; Fabrizio Galimberti, MD, PhD; and Brian Morrison, MD, of the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Dupilumab could be treatment option for chronic keloids

A new study has found that keloid formation may be driven by Th2 pathogenesis and, as such, Th2-targeting dupilumab may be useful in treating chronic keloids.

“This preliminary report demonstrates a novel use of dupilumab for chronic keloids, showing major reductions in skin fibrosis and keloidal scarring,” wrote Aisleen Diaz, from the department of dermatology and laboratory of inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. The study was published as a letter to the editor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The authors described a 53-year-old black male patient with severe atopic dermatitis and two keloids who, after 7 months of treatment with dupilumab for AD, had significant improvements in AD – as well as shrinkage of the larger keloid and “complete disappearance” of the smaller keloid.

As a follow-up, the researchers used real-time polymerase chain reaction testing to monitor Th2 gene expression in lesional and nonlesional keloid skin from three black patients (mean age, 47.3 years) with severe keloids and no AD. Five healthy black controls (mean age, 39.8 years) were also included for comparison. In addition, 6-mm whole-skin biopsy specimens were obtained from all patients.

Interleukin-4 receptors, directly targeted by dupilumab, were highly up-regulated in keloid lesions, compared with controls (P less than .1). The Th2 cytokine IL-13 was significantly increased in lesional and nonlesional keloids, compared with controls (P less than .05), and the TH2 cytokine CCL18 was also highly increased in keloids, chiefly in nonlesional skin (P less than .05).

With regard to genes involved in cartilage and bone development that have been recognized as highly expressed in keloids – such as cadherin 11 and fibrillin 2 – all were increased in keloid lesions, compared with both controls and to nonlesional skin (P less than .05), the researchers reported.

“Dupilumab and other Th2-targeting agents may provide treatment options for patients with severe keloids, warranting further studies,” they commented, adding that the patient they described was the first report of a keloid improving with dupilumab, which “blocks type 2 driven inflammation via IL-4/IL-13 signaling.”

Four authors, including Ms. Diaz, had no disclosures. Two authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants, research funds, and personal and consulting fees, from various pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and/or Sanofi.

SOURCE: Diaz A et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16097.

A new study has found that keloid formation may be driven by Th2 pathogenesis and, as such, Th2-targeting dupilumab may be useful in treating chronic keloids.

“This preliminary report demonstrates a novel use of dupilumab for chronic keloids, showing major reductions in skin fibrosis and keloidal scarring,” wrote Aisleen Diaz, from the department of dermatology and laboratory of inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. The study was published as a letter to the editor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The authors described a 53-year-old black male patient with severe atopic dermatitis and two keloids who, after 7 months of treatment with dupilumab for AD, had significant improvements in AD – as well as shrinkage of the larger keloid and “complete disappearance” of the smaller keloid.

As a follow-up, the researchers used real-time polymerase chain reaction testing to monitor Th2 gene expression in lesional and nonlesional keloid skin from three black patients (mean age, 47.3 years) with severe keloids and no AD. Five healthy black controls (mean age, 39.8 years) were also included for comparison. In addition, 6-mm whole-skin biopsy specimens were obtained from all patients.

Interleukin-4 receptors, directly targeted by dupilumab, were highly up-regulated in keloid lesions, compared with controls (P less than .1). The Th2 cytokine IL-13 was significantly increased in lesional and nonlesional keloids, compared with controls (P less than .05), and the TH2 cytokine CCL18 was also highly increased in keloids, chiefly in nonlesional skin (P less than .05).

With regard to genes involved in cartilage and bone development that have been recognized as highly expressed in keloids – such as cadherin 11 and fibrillin 2 – all were increased in keloid lesions, compared with both controls and to nonlesional skin (P less than .05), the researchers reported.

“Dupilumab and other Th2-targeting agents may provide treatment options for patients with severe keloids, warranting further studies,” they commented, adding that the patient they described was the first report of a keloid improving with dupilumab, which “blocks type 2 driven inflammation via IL-4/IL-13 signaling.”

Four authors, including Ms. Diaz, had no disclosures. Two authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants, research funds, and personal and consulting fees, from various pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and/or Sanofi.

SOURCE: Diaz A et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16097.

A new study has found that keloid formation may be driven by Th2 pathogenesis and, as such, Th2-targeting dupilumab may be useful in treating chronic keloids.

“This preliminary report demonstrates a novel use of dupilumab for chronic keloids, showing major reductions in skin fibrosis and keloidal scarring,” wrote Aisleen Diaz, from the department of dermatology and laboratory of inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. The study was published as a letter to the editor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The authors described a 53-year-old black male patient with severe atopic dermatitis and two keloids who, after 7 months of treatment with dupilumab for AD, had significant improvements in AD – as well as shrinkage of the larger keloid and “complete disappearance” of the smaller keloid.

As a follow-up, the researchers used real-time polymerase chain reaction testing to monitor Th2 gene expression in lesional and nonlesional keloid skin from three black patients (mean age, 47.3 years) with severe keloids and no AD. Five healthy black controls (mean age, 39.8 years) were also included for comparison. In addition, 6-mm whole-skin biopsy specimens were obtained from all patients.

Interleukin-4 receptors, directly targeted by dupilumab, were highly up-regulated in keloid lesions, compared with controls (P less than .1). The Th2 cytokine IL-13 was significantly increased in lesional and nonlesional keloids, compared with controls (P less than .05), and the TH2 cytokine CCL18 was also highly increased in keloids, chiefly in nonlesional skin (P less than .05).

With regard to genes involved in cartilage and bone development that have been recognized as highly expressed in keloids – such as cadherin 11 and fibrillin 2 – all were increased in keloid lesions, compared with both controls and to nonlesional skin (P less than .05), the researchers reported.

“Dupilumab and other Th2-targeting agents may provide treatment options for patients with severe keloids, warranting further studies,” they commented, adding that the patient they described was the first report of a keloid improving with dupilumab, which “blocks type 2 driven inflammation via IL-4/IL-13 signaling.”

Four authors, including Ms. Diaz, had no disclosures. Two authors reported numerous disclosures, including receiving grants, research funds, and personal and consulting fees, from various pharmaceutical companies, including dupilumab manufacturers Regeneron and/or Sanofi.

SOURCE: Diaz A et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16097.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY AND VENEREOLOGY