User login

Monkeypox largely a mystery for pregnant people

With monkeypox now circulating in the United States, expecting mothers may worry about what might happen if they contract the infection while pregnant.

As of today, 25 cases of monkeypox have been confirmed in the United States since the outbreak began in early May, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although none of those cases has involved a pregnant person, the World Health Organization says monkeypox can pass from mother to fetus before delivery or to newborns by close contact during and after birth.

The case count could grow as the agency continues to investigate potential infections of the virus. In a conference call Friday, health officials stressed the importance of contact tracing, testing, and vaccine treatment.

As physicians in the United States are scrambling for information on ways to treat patients, a new study, published in Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, could help clinicians better care for pregnant people infected with monkeypox. The authors advise consistently monitoring the fetus for infection and conducting regular ultrasounds, among other precautions.

Asma Khalil, MBBCh, MD, a professor of obstetrics and fetal medicine at St. George’s University, London, and lead author of the new study, said the monkeypox outbreak outside Africa caught many clinicians by surprise.

“We quickly realized very few physicians caring for pregnant women knew anything at all about monkeypox and how it affects pregnancy,” Dr. Khalil told this news organization. “Clinicians caring for pregnant women are likely to be faced soon with pregnant women concerned they may have the infection – because they have a rash, for example – or indeed pregnant women who do have the infection.”

According to the CDC, monkeypox can be transmitted through direct contact with the rash, sores, or scabs caused by the virus, as well as contact with clothing, bedding, towels, or other surfaces used by an infected person. Respiratory droplets and oral fluids from a person with monkeypox have also been linked to spread of the virus, as has sexual activity.

Although the condition is rarely fatal, infants and young children are at the greatest risk of developing severe symptoms, health officials said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a monkeypox vaccine, Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic A/S), for general use, but it has not been specifically approved for pregnant people. However, a study of 300 pregnant women who received the vaccine reported no adverse reactions or failed pregnancies linked to the shots.

The new review suggests that women who have a confirmed infection during pregnancy should have a doctor closely monitor the fetus until birth.

If the fetus is over 26 weeks or if the mother is unwell, the fetus should be cared for with heart monitoring, either by a doctor or remotely every 2-3 days. Ultrasounds should be performed regularly to confirm that the fetus is still growing well and that the placenta is functioning properly.

Further into the pregnancy, monitoring should include measurements of the fetus and detailed assessment of the fetal organs and the amniotic fluid. Once the infection is resolved, the risk to the fetus is small, according to Dr. Khalil. However, since data are limited, she recommended an ultrasound scan every 2-4 weeks. At birth, for the protection of the infant and the mother, the baby should be isolated until infection is no longer a risk.

The Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists is preparing guidance on the management of monkeypox in pregnant people, Dr. Khalil said. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said it is “relying on the CDC for the time being,” according to a spokesperson for ACOG.

“There is a clear need for further research in this area,” Dr. Khalil said. “The current outbreak is an ideal opportunity to make this happen.”

Dr. Khalil has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With monkeypox now circulating in the United States, expecting mothers may worry about what might happen if they contract the infection while pregnant.

As of today, 25 cases of monkeypox have been confirmed in the United States since the outbreak began in early May, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although none of those cases has involved a pregnant person, the World Health Organization says monkeypox can pass from mother to fetus before delivery or to newborns by close contact during and after birth.

The case count could grow as the agency continues to investigate potential infections of the virus. In a conference call Friday, health officials stressed the importance of contact tracing, testing, and vaccine treatment.

As physicians in the United States are scrambling for information on ways to treat patients, a new study, published in Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, could help clinicians better care for pregnant people infected with monkeypox. The authors advise consistently monitoring the fetus for infection and conducting regular ultrasounds, among other precautions.

Asma Khalil, MBBCh, MD, a professor of obstetrics and fetal medicine at St. George’s University, London, and lead author of the new study, said the monkeypox outbreak outside Africa caught many clinicians by surprise.

“We quickly realized very few physicians caring for pregnant women knew anything at all about monkeypox and how it affects pregnancy,” Dr. Khalil told this news organization. “Clinicians caring for pregnant women are likely to be faced soon with pregnant women concerned they may have the infection – because they have a rash, for example – or indeed pregnant women who do have the infection.”

According to the CDC, monkeypox can be transmitted through direct contact with the rash, sores, or scabs caused by the virus, as well as contact with clothing, bedding, towels, or other surfaces used by an infected person. Respiratory droplets and oral fluids from a person with monkeypox have also been linked to spread of the virus, as has sexual activity.

Although the condition is rarely fatal, infants and young children are at the greatest risk of developing severe symptoms, health officials said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a monkeypox vaccine, Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic A/S), for general use, but it has not been specifically approved for pregnant people. However, a study of 300 pregnant women who received the vaccine reported no adverse reactions or failed pregnancies linked to the shots.

The new review suggests that women who have a confirmed infection during pregnancy should have a doctor closely monitor the fetus until birth.

If the fetus is over 26 weeks or if the mother is unwell, the fetus should be cared for with heart monitoring, either by a doctor or remotely every 2-3 days. Ultrasounds should be performed regularly to confirm that the fetus is still growing well and that the placenta is functioning properly.

Further into the pregnancy, monitoring should include measurements of the fetus and detailed assessment of the fetal organs and the amniotic fluid. Once the infection is resolved, the risk to the fetus is small, according to Dr. Khalil. However, since data are limited, she recommended an ultrasound scan every 2-4 weeks. At birth, for the protection of the infant and the mother, the baby should be isolated until infection is no longer a risk.

The Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists is preparing guidance on the management of monkeypox in pregnant people, Dr. Khalil said. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said it is “relying on the CDC for the time being,” according to a spokesperson for ACOG.

“There is a clear need for further research in this area,” Dr. Khalil said. “The current outbreak is an ideal opportunity to make this happen.”

Dr. Khalil has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With monkeypox now circulating in the United States, expecting mothers may worry about what might happen if they contract the infection while pregnant.

As of today, 25 cases of monkeypox have been confirmed in the United States since the outbreak began in early May, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although none of those cases has involved a pregnant person, the World Health Organization says monkeypox can pass from mother to fetus before delivery or to newborns by close contact during and after birth.

The case count could grow as the agency continues to investigate potential infections of the virus. In a conference call Friday, health officials stressed the importance of contact tracing, testing, and vaccine treatment.

As physicians in the United States are scrambling for information on ways to treat patients, a new study, published in Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, could help clinicians better care for pregnant people infected with monkeypox. The authors advise consistently monitoring the fetus for infection and conducting regular ultrasounds, among other precautions.

Asma Khalil, MBBCh, MD, a professor of obstetrics and fetal medicine at St. George’s University, London, and lead author of the new study, said the monkeypox outbreak outside Africa caught many clinicians by surprise.

“We quickly realized very few physicians caring for pregnant women knew anything at all about monkeypox and how it affects pregnancy,” Dr. Khalil told this news organization. “Clinicians caring for pregnant women are likely to be faced soon with pregnant women concerned they may have the infection – because they have a rash, for example – or indeed pregnant women who do have the infection.”

According to the CDC, monkeypox can be transmitted through direct contact with the rash, sores, or scabs caused by the virus, as well as contact with clothing, bedding, towels, or other surfaces used by an infected person. Respiratory droplets and oral fluids from a person with monkeypox have also been linked to spread of the virus, as has sexual activity.

Although the condition is rarely fatal, infants and young children are at the greatest risk of developing severe symptoms, health officials said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a monkeypox vaccine, Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic A/S), for general use, but it has not been specifically approved for pregnant people. However, a study of 300 pregnant women who received the vaccine reported no adverse reactions or failed pregnancies linked to the shots.

The new review suggests that women who have a confirmed infection during pregnancy should have a doctor closely monitor the fetus until birth.

If the fetus is over 26 weeks or if the mother is unwell, the fetus should be cared for with heart monitoring, either by a doctor or remotely every 2-3 days. Ultrasounds should be performed regularly to confirm that the fetus is still growing well and that the placenta is functioning properly.

Further into the pregnancy, monitoring should include measurements of the fetus and detailed assessment of the fetal organs and the amniotic fluid. Once the infection is resolved, the risk to the fetus is small, according to Dr. Khalil. However, since data are limited, she recommended an ultrasound scan every 2-4 weeks. At birth, for the protection of the infant and the mother, the baby should be isolated until infection is no longer a risk.

The Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists is preparing guidance on the management of monkeypox in pregnant people, Dr. Khalil said. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said it is “relying on the CDC for the time being,” according to a spokesperson for ACOG.

“There is a clear need for further research in this area,” Dr. Khalil said. “The current outbreak is an ideal opportunity to make this happen.”

Dr. Khalil has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ECDC gives guidance on prevention and treatment of monkeypox

In a new risk-assessment document, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control summarizes what we currently know about monkeypox and recommends that European countries focus on the identification and management of the disease as well as contract tracing and prompt reporting of new cases of the virus.

Recent developments

From May 15 to May 23, in eight European Union member states (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden) a total of 85 cases of monkeypox were reported; they were acquired through autochthonous transmission. Current diagnosed cases of monkeypox have mainly been recorded in men who have sexual relations with other men, suggesting that transmission may occur during sexual intercourse, through infectious material coming into contact with mucosa or damaged skin, or via large respiratory droplets during prolonged face-to-face contact.

Andrea Ammon, MD, director of the ECDC, stated that “most current cases have presented with mild symptoms of the disease, and for the general population, the chance of diffusion is very low. However, the likelihood of a further spread of the virus through close contact, for example during sexual activities among people with multiple sexual partners, is considerably increased.”

Stella Kyriakides, European commissioner for health and food safety, added, “I am worried about the increase of cases of monkeypox in the EU and worldwide. We are currently monitoring the situation and, although, at the moment, the probability of it spreading to the general population is low, the situation is evolving. We should all remain alert, making sure that contact tracing and a sufficient diagnostic capacity are in place and guarantee that vaccines and antiviral drugs are available, as well as sufficient personal protective equipment [PPE] for health care professionals.”

Routes of transmission

Monkeypox is not easily spread among people. Person-to-person transmission occurs through close contact with infectious material, coming from skin lesions of an infected person, through air droplets in the case of prolonged face-to-face contact, and through fomites. So far, diagnosed cases suggest that transmission can occur through sexual intercourse.

The incubation period is 5-21 days, and patients are symptomatic for 2-4 weeks.

According to the ECDC, the likelihood of this infection spreading is increased among people who have more than one sexual partner. Although most current cases present with mild symptoms, monkeypox can cause severe disease in some groups (such as young children, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed people). However, the probability of severe disease cannot yet be estimated precisely.

The overall risk is considered moderate for people who have multiple sexual partners and low for the general population.

Clinical course

The disease initially presents with fever, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Within 3 days of the onset of the prodromal symptoms, a centrifugal maculopapular rash appears on the site of primary infection and rapidly spreads to other parts of the body. The palms of the hands and bottoms of the feet are involved in cases where the rash has spread, which is a characteristic of the disease. Usually within 12 days, the lesions progress, simultaneously changing from macules to papules, blisters, pustules, and scabs before falling off. The lesions may have a central depression and be extremely itchy.

If the patient scratches them, a secondary bacterial infection may take hold (for which treatment with oral antihistamines is indicated). Lesions may also be present in the oral or ocular mucous membrane. Either before or at the same time as onset of the rash, patients may experience swelling of the lymph nodes, which usually is not seen with smallpox or chickenpox.

The onset of the rash is considered the start of the infectious period; however, people with prodromal symptoms may also transmit the virus.

Most cases in people present with mild or moderate symptoms. Complications seen in endemic countries include encephalitis, secondary bacterial skin infections, dehydration, conjunctivitis, keratitis, and pneumonia. The death rate ranges from 0% to 11% in endemic areas, with fatalities from the disease mostly occurring in younger children.

There is not a lot of information available on the disease in immunosuppressed individuals. In the 2017 Nigerian epidemic, patients with a concomitant HIV infection presented with more severe disease, with a greater number of skin lesions and genital ulcers, compared with HIV-negative individuals. No deaths were reported among seropositive patients. The main sequelae from the disease are usually disfiguring scars and permanent corneal lesions.

Treatment

No smallpox vaccines are authorized for use against monkeypox, however the third-generation smallpox vaccine Imvanex (Modified Vaccinia Ankara) has been authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the EU market against smallpox and has demonstrated to provide protection in primates.

Old-generation smallpox vaccines have significant side effects, are no longer authorized, and should no longer be used. It is also important to note the lack of safety data for the use of Imvanex in immunocompromised people.

For this reason, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups have been asked to develop specific guidelines for vaccination in close contacts of patients with monkeypox. The use of a smallpox vaccine for preexposure prophylaxis cannot be considered now, when taking into account the risk-benefit ratio.

In regard to treatment, tecovirimat is the only antiviral drug with an EMA-authorized indication for orthopoxvirus infection.

Brincidofovir is not authorized in the EU but has been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration. However, availability on the European market is limited somewhat by the number of doses.

According to the ECDC, health care authorities should provide information about which groups should have priority access to treatment.

The use of antivirals for postexposure prophylaxis should be investigated further. Cidofovir is active in vitro for smallpox but has a pronounced nephrotoxicity profile that makes it unsuitable for first-line treatment.

The ECDC document also proposes an interim case definition for epidemiologic reporting. Further indications will also be provided for the management of monkeypox cases and close contacts. Those infected should remain in isolation until the scabs have fallen off and should, above all, avoid close contact with at-risk or immunosuppressed people as well as pets.

Most infected people can remain at home with supportive care.

Prevention

Close contacts for cases of monkeypox should monitor the development of their symptoms until 21 days have passed from their most recent exposure to the virus.

Health care workers should wear appropriate PPE (gloves, water-resistant gowns, FFP2 masks) during screening for suspected cases or when working with confirmed cases. Laboratory staff should also take precautions to avoid exposure in the workplace.

Close contacts of an infected person should not donate blood, organs, or bone marrow for at least 21 days from the last day of exposure.

Finally, the ECDC recommends increasing proactive communication of the risks to increase awareness and provide updates and indications to individuals who are at a greater risk, as well as to the general public. These messages should highlight that monkeypox is spread through close person-to-person contact, especially within the family unit, and also potentially through sexual intercourse. A balance, however, should be maintained between informing the individuals who are at greater risk and communicating that the virus is not easily spread and that the risk for the general population is low.

Human-to-animal transmission

A potential risk for human-to-animal transmission exists in Europe; therefore, a close collaboration is required between human and veterinary health care authorities, working together to manage domestic animals exposed to the virus and to prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife. To date, the European Food Safety Authority is not aware of any reports of animal infections (domestic or wild) within the EU.

There are still many unknown factors about this outbreak. The ECDC continues to closely monitor any developments and will update the risk assessment as soon as new data and information become available.

If human-to-animal transmission occurs and the virus spreads among animal populations, there is a risk that the disease could become an endemic in Europe. Therefore, human and veterinary health care authorities should work together closely to manage cases of domestic animals exposed to the virus and prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

In a new risk-assessment document, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control summarizes what we currently know about monkeypox and recommends that European countries focus on the identification and management of the disease as well as contract tracing and prompt reporting of new cases of the virus.

Recent developments

From May 15 to May 23, in eight European Union member states (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden) a total of 85 cases of monkeypox were reported; they were acquired through autochthonous transmission. Current diagnosed cases of monkeypox have mainly been recorded in men who have sexual relations with other men, suggesting that transmission may occur during sexual intercourse, through infectious material coming into contact with mucosa or damaged skin, or via large respiratory droplets during prolonged face-to-face contact.

Andrea Ammon, MD, director of the ECDC, stated that “most current cases have presented with mild symptoms of the disease, and for the general population, the chance of diffusion is very low. However, the likelihood of a further spread of the virus through close contact, for example during sexual activities among people with multiple sexual partners, is considerably increased.”

Stella Kyriakides, European commissioner for health and food safety, added, “I am worried about the increase of cases of monkeypox in the EU and worldwide. We are currently monitoring the situation and, although, at the moment, the probability of it spreading to the general population is low, the situation is evolving. We should all remain alert, making sure that contact tracing and a sufficient diagnostic capacity are in place and guarantee that vaccines and antiviral drugs are available, as well as sufficient personal protective equipment [PPE] for health care professionals.”

Routes of transmission

Monkeypox is not easily spread among people. Person-to-person transmission occurs through close contact with infectious material, coming from skin lesions of an infected person, through air droplets in the case of prolonged face-to-face contact, and through fomites. So far, diagnosed cases suggest that transmission can occur through sexual intercourse.

The incubation period is 5-21 days, and patients are symptomatic for 2-4 weeks.

According to the ECDC, the likelihood of this infection spreading is increased among people who have more than one sexual partner. Although most current cases present with mild symptoms, monkeypox can cause severe disease in some groups (such as young children, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed people). However, the probability of severe disease cannot yet be estimated precisely.

The overall risk is considered moderate for people who have multiple sexual partners and low for the general population.

Clinical course

The disease initially presents with fever, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Within 3 days of the onset of the prodromal symptoms, a centrifugal maculopapular rash appears on the site of primary infection and rapidly spreads to other parts of the body. The palms of the hands and bottoms of the feet are involved in cases where the rash has spread, which is a characteristic of the disease. Usually within 12 days, the lesions progress, simultaneously changing from macules to papules, blisters, pustules, and scabs before falling off. The lesions may have a central depression and be extremely itchy.

If the patient scratches them, a secondary bacterial infection may take hold (for which treatment with oral antihistamines is indicated). Lesions may also be present in the oral or ocular mucous membrane. Either before or at the same time as onset of the rash, patients may experience swelling of the lymph nodes, which usually is not seen with smallpox or chickenpox.

The onset of the rash is considered the start of the infectious period; however, people with prodromal symptoms may also transmit the virus.

Most cases in people present with mild or moderate symptoms. Complications seen in endemic countries include encephalitis, secondary bacterial skin infections, dehydration, conjunctivitis, keratitis, and pneumonia. The death rate ranges from 0% to 11% in endemic areas, with fatalities from the disease mostly occurring in younger children.

There is not a lot of information available on the disease in immunosuppressed individuals. In the 2017 Nigerian epidemic, patients with a concomitant HIV infection presented with more severe disease, with a greater number of skin lesions and genital ulcers, compared with HIV-negative individuals. No deaths were reported among seropositive patients. The main sequelae from the disease are usually disfiguring scars and permanent corneal lesions.

Treatment

No smallpox vaccines are authorized for use against monkeypox, however the third-generation smallpox vaccine Imvanex (Modified Vaccinia Ankara) has been authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the EU market against smallpox and has demonstrated to provide protection in primates.

Old-generation smallpox vaccines have significant side effects, are no longer authorized, and should no longer be used. It is also important to note the lack of safety data for the use of Imvanex in immunocompromised people.

For this reason, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups have been asked to develop specific guidelines for vaccination in close contacts of patients with monkeypox. The use of a smallpox vaccine for preexposure prophylaxis cannot be considered now, when taking into account the risk-benefit ratio.

In regard to treatment, tecovirimat is the only antiviral drug with an EMA-authorized indication for orthopoxvirus infection.

Brincidofovir is not authorized in the EU but has been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration. However, availability on the European market is limited somewhat by the number of doses.

According to the ECDC, health care authorities should provide information about which groups should have priority access to treatment.

The use of antivirals for postexposure prophylaxis should be investigated further. Cidofovir is active in vitro for smallpox but has a pronounced nephrotoxicity profile that makes it unsuitable for first-line treatment.

The ECDC document also proposes an interim case definition for epidemiologic reporting. Further indications will also be provided for the management of monkeypox cases and close contacts. Those infected should remain in isolation until the scabs have fallen off and should, above all, avoid close contact with at-risk or immunosuppressed people as well as pets.

Most infected people can remain at home with supportive care.

Prevention

Close contacts for cases of monkeypox should monitor the development of their symptoms until 21 days have passed from their most recent exposure to the virus.

Health care workers should wear appropriate PPE (gloves, water-resistant gowns, FFP2 masks) during screening for suspected cases or when working with confirmed cases. Laboratory staff should also take precautions to avoid exposure in the workplace.

Close contacts of an infected person should not donate blood, organs, or bone marrow for at least 21 days from the last day of exposure.

Finally, the ECDC recommends increasing proactive communication of the risks to increase awareness and provide updates and indications to individuals who are at a greater risk, as well as to the general public. These messages should highlight that monkeypox is spread through close person-to-person contact, especially within the family unit, and also potentially through sexual intercourse. A balance, however, should be maintained between informing the individuals who are at greater risk and communicating that the virus is not easily spread and that the risk for the general population is low.

Human-to-animal transmission

A potential risk for human-to-animal transmission exists in Europe; therefore, a close collaboration is required between human and veterinary health care authorities, working together to manage domestic animals exposed to the virus and to prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife. To date, the European Food Safety Authority is not aware of any reports of animal infections (domestic or wild) within the EU.

There are still many unknown factors about this outbreak. The ECDC continues to closely monitor any developments and will update the risk assessment as soon as new data and information become available.

If human-to-animal transmission occurs and the virus spreads among animal populations, there is a risk that the disease could become an endemic in Europe. Therefore, human and veterinary health care authorities should work together closely to manage cases of domestic animals exposed to the virus and prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

In a new risk-assessment document, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control summarizes what we currently know about monkeypox and recommends that European countries focus on the identification and management of the disease as well as contract tracing and prompt reporting of new cases of the virus.

Recent developments

From May 15 to May 23, in eight European Union member states (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden) a total of 85 cases of monkeypox were reported; they were acquired through autochthonous transmission. Current diagnosed cases of monkeypox have mainly been recorded in men who have sexual relations with other men, suggesting that transmission may occur during sexual intercourse, through infectious material coming into contact with mucosa or damaged skin, or via large respiratory droplets during prolonged face-to-face contact.

Andrea Ammon, MD, director of the ECDC, stated that “most current cases have presented with mild symptoms of the disease, and for the general population, the chance of diffusion is very low. However, the likelihood of a further spread of the virus through close contact, for example during sexual activities among people with multiple sexual partners, is considerably increased.”

Stella Kyriakides, European commissioner for health and food safety, added, “I am worried about the increase of cases of monkeypox in the EU and worldwide. We are currently monitoring the situation and, although, at the moment, the probability of it spreading to the general population is low, the situation is evolving. We should all remain alert, making sure that contact tracing and a sufficient diagnostic capacity are in place and guarantee that vaccines and antiviral drugs are available, as well as sufficient personal protective equipment [PPE] for health care professionals.”

Routes of transmission

Monkeypox is not easily spread among people. Person-to-person transmission occurs through close contact with infectious material, coming from skin lesions of an infected person, through air droplets in the case of prolonged face-to-face contact, and through fomites. So far, diagnosed cases suggest that transmission can occur through sexual intercourse.

The incubation period is 5-21 days, and patients are symptomatic for 2-4 weeks.

According to the ECDC, the likelihood of this infection spreading is increased among people who have more than one sexual partner. Although most current cases present with mild symptoms, monkeypox can cause severe disease in some groups (such as young children, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed people). However, the probability of severe disease cannot yet be estimated precisely.

The overall risk is considered moderate for people who have multiple sexual partners and low for the general population.

Clinical course

The disease initially presents with fever, myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Within 3 days of the onset of the prodromal symptoms, a centrifugal maculopapular rash appears on the site of primary infection and rapidly spreads to other parts of the body. The palms of the hands and bottoms of the feet are involved in cases where the rash has spread, which is a characteristic of the disease. Usually within 12 days, the lesions progress, simultaneously changing from macules to papules, blisters, pustules, and scabs before falling off. The lesions may have a central depression and be extremely itchy.

If the patient scratches them, a secondary bacterial infection may take hold (for which treatment with oral antihistamines is indicated). Lesions may also be present in the oral or ocular mucous membrane. Either before or at the same time as onset of the rash, patients may experience swelling of the lymph nodes, which usually is not seen with smallpox or chickenpox.

The onset of the rash is considered the start of the infectious period; however, people with prodromal symptoms may also transmit the virus.

Most cases in people present with mild or moderate symptoms. Complications seen in endemic countries include encephalitis, secondary bacterial skin infections, dehydration, conjunctivitis, keratitis, and pneumonia. The death rate ranges from 0% to 11% in endemic areas, with fatalities from the disease mostly occurring in younger children.

There is not a lot of information available on the disease in immunosuppressed individuals. In the 2017 Nigerian epidemic, patients with a concomitant HIV infection presented with more severe disease, with a greater number of skin lesions and genital ulcers, compared with HIV-negative individuals. No deaths were reported among seropositive patients. The main sequelae from the disease are usually disfiguring scars and permanent corneal lesions.

Treatment

No smallpox vaccines are authorized for use against monkeypox, however the third-generation smallpox vaccine Imvanex (Modified Vaccinia Ankara) has been authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the EU market against smallpox and has demonstrated to provide protection in primates.

Old-generation smallpox vaccines have significant side effects, are no longer authorized, and should no longer be used. It is also important to note the lack of safety data for the use of Imvanex in immunocompromised people.

For this reason, National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups have been asked to develop specific guidelines for vaccination in close contacts of patients with monkeypox. The use of a smallpox vaccine for preexposure prophylaxis cannot be considered now, when taking into account the risk-benefit ratio.

In regard to treatment, tecovirimat is the only antiviral drug with an EMA-authorized indication for orthopoxvirus infection.

Brincidofovir is not authorized in the EU but has been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration. However, availability on the European market is limited somewhat by the number of doses.

According to the ECDC, health care authorities should provide information about which groups should have priority access to treatment.

The use of antivirals for postexposure prophylaxis should be investigated further. Cidofovir is active in vitro for smallpox but has a pronounced nephrotoxicity profile that makes it unsuitable for first-line treatment.

The ECDC document also proposes an interim case definition for epidemiologic reporting. Further indications will also be provided for the management of monkeypox cases and close contacts. Those infected should remain in isolation until the scabs have fallen off and should, above all, avoid close contact with at-risk or immunosuppressed people as well as pets.

Most infected people can remain at home with supportive care.

Prevention

Close contacts for cases of monkeypox should monitor the development of their symptoms until 21 days have passed from their most recent exposure to the virus.

Health care workers should wear appropriate PPE (gloves, water-resistant gowns, FFP2 masks) during screening for suspected cases or when working with confirmed cases. Laboratory staff should also take precautions to avoid exposure in the workplace.

Close contacts of an infected person should not donate blood, organs, or bone marrow for at least 21 days from the last day of exposure.

Finally, the ECDC recommends increasing proactive communication of the risks to increase awareness and provide updates and indications to individuals who are at a greater risk, as well as to the general public. These messages should highlight that monkeypox is spread through close person-to-person contact, especially within the family unit, and also potentially through sexual intercourse. A balance, however, should be maintained between informing the individuals who are at greater risk and communicating that the virus is not easily spread and that the risk for the general population is low.

Human-to-animal transmission

A potential risk for human-to-animal transmission exists in Europe; therefore, a close collaboration is required between human and veterinary health care authorities, working together to manage domestic animals exposed to the virus and to prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife. To date, the European Food Safety Authority is not aware of any reports of animal infections (domestic or wild) within the EU.

There are still many unknown factors about this outbreak. The ECDC continues to closely monitor any developments and will update the risk assessment as soon as new data and information become available.

If human-to-animal transmission occurs and the virus spreads among animal populations, there is a risk that the disease could become an endemic in Europe. Therefore, human and veterinary health care authorities should work together closely to manage cases of domestic animals exposed to the virus and prevent transmission of the disease to wildlife.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

Pfizer asks FDA to authorize COVID vaccine for children younger than 5

The FDA has accepted Pfizer’s application for a COVID-19 vaccine for children under age 5, which clears the way for approval and distribution in June.

Pfizer announced June 1 that it completed the application for a three-dose vaccine for kids between 6 months and 5 years old, and the FDA said it received the emergency use application.

Children in this age group – the last to be eligible for COVID-19 vaccines – could begin getting shots as early as June 21, according to White House COVID-19 response coordinator Ashish Jha, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 cases are still high – an average of 100,000 cases a day – but death numbers are about 90% lower than they were when President Joe Biden first took office, Dr. Jha said.

The FDA’s advisory group, the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, is scheduled to meet June 14 and June 15 to discuss data submitted by both Pfizer and Moderna.

If the FDA gives them the green light, the CDC will then weigh in.

“We know that many, many parents are eager to vaccinate their youngest kids, and it’s important to do this right,” Dr. Jha said at a White House press briefing on June 2. “We expect that vaccinations will begin in earnest as early as June 21 and really roll on throughout that week.”

States can place their orders as early as June 3, Dr. Jha said, and there will initially be 10 million doses available. If the FDA gives emergency use authorization for the vaccines, the government will begin shipping doses to thousands of sites across the country.

“The good news is we have plenty of supply of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines,” Dr. Jha said. “We’ve asked states to distribute to their highest priority sites, serving the highest risk and hardest to reach areas.”

Pfizer’s clinical trials found that three doses of the vaccine for children 6 months to under 5 years were safe and effective and proved to be 80% effective against Omicron.

The FDA announced its meeting information with a conversation about the Moderna vaccine for ages 6-17 scheduled for June 14 and a conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines for young children scheduled for June 15.

Moderna applied for FDA authorization of its two-dose vaccine for children under age 6 on April 28. The company said the vaccine was 51% effective against infections with symptoms for children ages 6 months to 2 years and 37% effective for ages 2-5.

Pfizer’s 3-microgram dose is one-tenth of its adult dose. Moderna’s 25-microgram dose is one-quarter of its adult dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA has accepted Pfizer’s application for a COVID-19 vaccine for children under age 5, which clears the way for approval and distribution in June.

Pfizer announced June 1 that it completed the application for a three-dose vaccine for kids between 6 months and 5 years old, and the FDA said it received the emergency use application.

Children in this age group – the last to be eligible for COVID-19 vaccines – could begin getting shots as early as June 21, according to White House COVID-19 response coordinator Ashish Jha, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 cases are still high – an average of 100,000 cases a day – but death numbers are about 90% lower than they were when President Joe Biden first took office, Dr. Jha said.

The FDA’s advisory group, the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, is scheduled to meet June 14 and June 15 to discuss data submitted by both Pfizer and Moderna.

If the FDA gives them the green light, the CDC will then weigh in.

“We know that many, many parents are eager to vaccinate their youngest kids, and it’s important to do this right,” Dr. Jha said at a White House press briefing on June 2. “We expect that vaccinations will begin in earnest as early as June 21 and really roll on throughout that week.”

States can place their orders as early as June 3, Dr. Jha said, and there will initially be 10 million doses available. If the FDA gives emergency use authorization for the vaccines, the government will begin shipping doses to thousands of sites across the country.

“The good news is we have plenty of supply of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines,” Dr. Jha said. “We’ve asked states to distribute to their highest priority sites, serving the highest risk and hardest to reach areas.”

Pfizer’s clinical trials found that three doses of the vaccine for children 6 months to under 5 years were safe and effective and proved to be 80% effective against Omicron.

The FDA announced its meeting information with a conversation about the Moderna vaccine for ages 6-17 scheduled for June 14 and a conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines for young children scheduled for June 15.

Moderna applied for FDA authorization of its two-dose vaccine for children under age 6 on April 28. The company said the vaccine was 51% effective against infections with symptoms for children ages 6 months to 2 years and 37% effective for ages 2-5.

Pfizer’s 3-microgram dose is one-tenth of its adult dose. Moderna’s 25-microgram dose is one-quarter of its adult dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA has accepted Pfizer’s application for a COVID-19 vaccine for children under age 5, which clears the way for approval and distribution in June.

Pfizer announced June 1 that it completed the application for a three-dose vaccine for kids between 6 months and 5 years old, and the FDA said it received the emergency use application.

Children in this age group – the last to be eligible for COVID-19 vaccines – could begin getting shots as early as June 21, according to White House COVID-19 response coordinator Ashish Jha, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 cases are still high – an average of 100,000 cases a day – but death numbers are about 90% lower than they were when President Joe Biden first took office, Dr. Jha said.

The FDA’s advisory group, the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, is scheduled to meet June 14 and June 15 to discuss data submitted by both Pfizer and Moderna.

If the FDA gives them the green light, the CDC will then weigh in.

“We know that many, many parents are eager to vaccinate their youngest kids, and it’s important to do this right,” Dr. Jha said at a White House press briefing on June 2. “We expect that vaccinations will begin in earnest as early as June 21 and really roll on throughout that week.”

States can place their orders as early as June 3, Dr. Jha said, and there will initially be 10 million doses available. If the FDA gives emergency use authorization for the vaccines, the government will begin shipping doses to thousands of sites across the country.

“The good news is we have plenty of supply of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines,” Dr. Jha said. “We’ve asked states to distribute to their highest priority sites, serving the highest risk and hardest to reach areas.”

Pfizer’s clinical trials found that three doses of the vaccine for children 6 months to under 5 years were safe and effective and proved to be 80% effective against Omicron.

The FDA announced its meeting information with a conversation about the Moderna vaccine for ages 6-17 scheduled for June 14 and a conversation about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines for young children scheduled for June 15.

Moderna applied for FDA authorization of its two-dose vaccine for children under age 6 on April 28. The company said the vaccine was 51% effective against infections with symptoms for children ages 6 months to 2 years and 37% effective for ages 2-5.

Pfizer’s 3-microgram dose is one-tenth of its adult dose. Moderna’s 25-microgram dose is one-quarter of its adult dose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TDF use in HBV-HIV coinfection linked with kidney, bone issues

Patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus who take tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) may have worsening renal function and bone turnover, according to a small, prospective cohort study in HIV Medicine.

“In this HBV-HIV cohort of adults with high prevalence of tenofovir use, several biomarkers of renal function and bone turnover indicated worsening status over approximately 4 years, highlighting the importance of clinicians’ awareness,” lead author Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc, assistant chair of research in the department of internal medicine of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization in an email.

TDF is a common component of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in adults coinfected with HBV and HIV. The drug is known to adversely affect kidney function and bone turnover, but few studies have evaluated these issues, the authors write.

Dr. Sterling and colleagues enrolled adults coinfected with HBV and HIV who were taking any type of ART in their study at eight sites in North America.

The authors assessed demographics, medical history, current health status reports, physical exams, and blood and urine tests. They extracted clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data from medical records, and they processed whole blood, stored serum at -70 °C (-94 °F) at each site, and tested specimens in central laboratories.

The researchers assessed the participants at baseline and every 24 weeks for up to 192 weeks (3.7 years). They tested bone markers from stored serum at baseline, week 96, and week 192. And they recorded changes in renal function markers and bone turnover over time.

At baseline, the median age of the 115 patients was 49 years; 91% were male, and 52% were non-Hispanic Black. Their median body mass index was 26 kg/m2, with 6.3% of participants underweight and 59% overweight or obese. The participants had been living with HIV for a median of about 20 years.

Overall, 84% of participants reported tenofovir use, 3% reported no HBV therapy, and 80% had HBV/HIV suppression. In addition, 13% had stage 2 liver fibrosis and 23% had stage 3 to 4 liver fibrosis. No participants reported using immunosuppressants, 4% reported using an anticoagulant, 3% reported taking calcium plus vitamin D, and 33% reported taking multivitamins.

Throughout the follow-up period, TDF use ranged from 80% to 92%. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) dropped from 87.1 to 79.9 ml/min/1.73m2 over 192 weeks (P < .001); but eGFR prevalence < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 did not appear to change over time (always < 16%; P = .43).

From baseline to week 192, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) dropped from 146.7 to 130.5 ng/ml (P = .001), osteocalcin dropped from 14.4 to 10.2 ng/ml (P < .001), and C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX-1) dropped from 373 to 273 pg/ml (P < .001).

Predictors of decrease in eGFR included younger age, male sex, and overweight or obesity. Predictors of worsening bone turnover included Black race, healthy weight, advanced fibrosis, undetectable HBV DNA, and lower parathyroid hormone level.

Monitor patients with HBV and HIV closely

“The long-term effects of TDF on renal and bone health are important to monitor,” Dr. Sterling advised. “For renal health, physicians should monitor GFR as well as creatinine. For bone health, monitoring serum calcium, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and phosphate may not catch increased bone turnover.”

“We knew that TDF can cause renal dysfunction; however, we were surprised that we did not observe significant rise in serum creatinine but did observe decline in glomerular filtration rate and several markers of increased bone turnover,” he added.

Dr. Sterling acknowledged that limitations of the study include its small cohort, short follow-up, and lack of control participants who were taking TDF while mono-infected with either HBV or HIV. He added that strengths include close follow-up, use of bone turnover markers, and control for severity of liver disease.

Joseph Alvarnas, MD, a hematologist and oncologist in the department of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplant at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California, told this news organization that he welcomes the rigor of the study. “This study provides an important reminder of the complexities of taking a comprehensive management approach to the care of patients with long-term HIV infection,” Dr. Alvarnas wrote in an email. He was not involved in the study.

“More than 6 million people worldwide live with coinfection,” he added. “Patients coinfected with HBV and HIV have additional care needs over those living with only chronic HIV infection. With more HIV-infected patients becoming long-term survivors who are managed through the use of effective ART, fully understanding the differentiated long-term care needs of this population is important.”

Debika Bhattacharya, MD, a specialist in HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection in the Division of Infectious Diseases at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, joined Dr. Sterling and Dr. Alvarnas in advising clinicians to regularly evaluate the kidney and bone health of their coinfected patients.

“While this study focuses the very common antiretroviral agent TDF, it will be important to see the impact of a similar drug, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) – which has been associated with less impact on bone and kidney health – on clinical outcomes in HBV-HIV coinfection,” Dr. Bhattacharya, who also was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Sterling has served on boards for Pfizer and AskBio, and he reports research grants from Gilead, Abbott, AbbVie, and Roche to his institution. Most other authors report financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Alvarnas reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhattacharya has received a research grant from Gilead Sciences, paid to her institution.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus who take tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) may have worsening renal function and bone turnover, according to a small, prospective cohort study in HIV Medicine.

“In this HBV-HIV cohort of adults with high prevalence of tenofovir use, several biomarkers of renal function and bone turnover indicated worsening status over approximately 4 years, highlighting the importance of clinicians’ awareness,” lead author Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc, assistant chair of research in the department of internal medicine of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization in an email.

TDF is a common component of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in adults coinfected with HBV and HIV. The drug is known to adversely affect kidney function and bone turnover, but few studies have evaluated these issues, the authors write.

Dr. Sterling and colleagues enrolled adults coinfected with HBV and HIV who were taking any type of ART in their study at eight sites in North America.

The authors assessed demographics, medical history, current health status reports, physical exams, and blood and urine tests. They extracted clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data from medical records, and they processed whole blood, stored serum at -70 °C (-94 °F) at each site, and tested specimens in central laboratories.

The researchers assessed the participants at baseline and every 24 weeks for up to 192 weeks (3.7 years). They tested bone markers from stored serum at baseline, week 96, and week 192. And they recorded changes in renal function markers and bone turnover over time.

At baseline, the median age of the 115 patients was 49 years; 91% were male, and 52% were non-Hispanic Black. Their median body mass index was 26 kg/m2, with 6.3% of participants underweight and 59% overweight or obese. The participants had been living with HIV for a median of about 20 years.

Overall, 84% of participants reported tenofovir use, 3% reported no HBV therapy, and 80% had HBV/HIV suppression. In addition, 13% had stage 2 liver fibrosis and 23% had stage 3 to 4 liver fibrosis. No participants reported using immunosuppressants, 4% reported using an anticoagulant, 3% reported taking calcium plus vitamin D, and 33% reported taking multivitamins.

Throughout the follow-up period, TDF use ranged from 80% to 92%. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) dropped from 87.1 to 79.9 ml/min/1.73m2 over 192 weeks (P < .001); but eGFR prevalence < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 did not appear to change over time (always < 16%; P = .43).

From baseline to week 192, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) dropped from 146.7 to 130.5 ng/ml (P = .001), osteocalcin dropped from 14.4 to 10.2 ng/ml (P < .001), and C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX-1) dropped from 373 to 273 pg/ml (P < .001).

Predictors of decrease in eGFR included younger age, male sex, and overweight or obesity. Predictors of worsening bone turnover included Black race, healthy weight, advanced fibrosis, undetectable HBV DNA, and lower parathyroid hormone level.

Monitor patients with HBV and HIV closely

“The long-term effects of TDF on renal and bone health are important to monitor,” Dr. Sterling advised. “For renal health, physicians should monitor GFR as well as creatinine. For bone health, monitoring serum calcium, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and phosphate may not catch increased bone turnover.”

“We knew that TDF can cause renal dysfunction; however, we were surprised that we did not observe significant rise in serum creatinine but did observe decline in glomerular filtration rate and several markers of increased bone turnover,” he added.

Dr. Sterling acknowledged that limitations of the study include its small cohort, short follow-up, and lack of control participants who were taking TDF while mono-infected with either HBV or HIV. He added that strengths include close follow-up, use of bone turnover markers, and control for severity of liver disease.

Joseph Alvarnas, MD, a hematologist and oncologist in the department of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplant at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California, told this news organization that he welcomes the rigor of the study. “This study provides an important reminder of the complexities of taking a comprehensive management approach to the care of patients with long-term HIV infection,” Dr. Alvarnas wrote in an email. He was not involved in the study.

“More than 6 million people worldwide live with coinfection,” he added. “Patients coinfected with HBV and HIV have additional care needs over those living with only chronic HIV infection. With more HIV-infected patients becoming long-term survivors who are managed through the use of effective ART, fully understanding the differentiated long-term care needs of this population is important.”

Debika Bhattacharya, MD, a specialist in HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection in the Division of Infectious Diseases at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, joined Dr. Sterling and Dr. Alvarnas in advising clinicians to regularly evaluate the kidney and bone health of their coinfected patients.

“While this study focuses the very common antiretroviral agent TDF, it will be important to see the impact of a similar drug, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) – which has been associated with less impact on bone and kidney health – on clinical outcomes in HBV-HIV coinfection,” Dr. Bhattacharya, who also was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Sterling has served on boards for Pfizer and AskBio, and he reports research grants from Gilead, Abbott, AbbVie, and Roche to his institution. Most other authors report financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Alvarnas reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhattacharya has received a research grant from Gilead Sciences, paid to her institution.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus who take tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) may have worsening renal function and bone turnover, according to a small, prospective cohort study in HIV Medicine.

“In this HBV-HIV cohort of adults with high prevalence of tenofovir use, several biomarkers of renal function and bone turnover indicated worsening status over approximately 4 years, highlighting the importance of clinicians’ awareness,” lead author Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc, assistant chair of research in the department of internal medicine of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, told this news organization in an email.

TDF is a common component of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in adults coinfected with HBV and HIV. The drug is known to adversely affect kidney function and bone turnover, but few studies have evaluated these issues, the authors write.

Dr. Sterling and colleagues enrolled adults coinfected with HBV and HIV who were taking any type of ART in their study at eight sites in North America.

The authors assessed demographics, medical history, current health status reports, physical exams, and blood and urine tests. They extracted clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data from medical records, and they processed whole blood, stored serum at -70 °C (-94 °F) at each site, and tested specimens in central laboratories.

The researchers assessed the participants at baseline and every 24 weeks for up to 192 weeks (3.7 years). They tested bone markers from stored serum at baseline, week 96, and week 192. And they recorded changes in renal function markers and bone turnover over time.

At baseline, the median age of the 115 patients was 49 years; 91% were male, and 52% were non-Hispanic Black. Their median body mass index was 26 kg/m2, with 6.3% of participants underweight and 59% overweight or obese. The participants had been living with HIV for a median of about 20 years.

Overall, 84% of participants reported tenofovir use, 3% reported no HBV therapy, and 80% had HBV/HIV suppression. In addition, 13% had stage 2 liver fibrosis and 23% had stage 3 to 4 liver fibrosis. No participants reported using immunosuppressants, 4% reported using an anticoagulant, 3% reported taking calcium plus vitamin D, and 33% reported taking multivitamins.

Throughout the follow-up period, TDF use ranged from 80% to 92%. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) dropped from 87.1 to 79.9 ml/min/1.73m2 over 192 weeks (P < .001); but eGFR prevalence < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 did not appear to change over time (always < 16%; P = .43).

From baseline to week 192, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) dropped from 146.7 to 130.5 ng/ml (P = .001), osteocalcin dropped from 14.4 to 10.2 ng/ml (P < .001), and C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX-1) dropped from 373 to 273 pg/ml (P < .001).

Predictors of decrease in eGFR included younger age, male sex, and overweight or obesity. Predictors of worsening bone turnover included Black race, healthy weight, advanced fibrosis, undetectable HBV DNA, and lower parathyroid hormone level.

Monitor patients with HBV and HIV closely

“The long-term effects of TDF on renal and bone health are important to monitor,” Dr. Sterling advised. “For renal health, physicians should monitor GFR as well as creatinine. For bone health, monitoring serum calcium, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and phosphate may not catch increased bone turnover.”

“We knew that TDF can cause renal dysfunction; however, we were surprised that we did not observe significant rise in serum creatinine but did observe decline in glomerular filtration rate and several markers of increased bone turnover,” he added.

Dr. Sterling acknowledged that limitations of the study include its small cohort, short follow-up, and lack of control participants who were taking TDF while mono-infected with either HBV or HIV. He added that strengths include close follow-up, use of bone turnover markers, and control for severity of liver disease.

Joseph Alvarnas, MD, a hematologist and oncologist in the department of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplant at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California, told this news organization that he welcomes the rigor of the study. “This study provides an important reminder of the complexities of taking a comprehensive management approach to the care of patients with long-term HIV infection,” Dr. Alvarnas wrote in an email. He was not involved in the study.

“More than 6 million people worldwide live with coinfection,” he added. “Patients coinfected with HBV and HIV have additional care needs over those living with only chronic HIV infection. With more HIV-infected patients becoming long-term survivors who are managed through the use of effective ART, fully understanding the differentiated long-term care needs of this population is important.”

Debika Bhattacharya, MD, a specialist in HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection in the Division of Infectious Diseases at UCLA Health, Los Angeles, joined Dr. Sterling and Dr. Alvarnas in advising clinicians to regularly evaluate the kidney and bone health of their coinfected patients.

“While this study focuses the very common antiretroviral agent TDF, it will be important to see the impact of a similar drug, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) – which has been associated with less impact on bone and kidney health – on clinical outcomes in HBV-HIV coinfection,” Dr. Bhattacharya, who also was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. Dr. Sterling has served on boards for Pfizer and AskBio, and he reports research grants from Gilead, Abbott, AbbVie, and Roche to his institution. Most other authors report financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Alvarnas reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhattacharya has received a research grant from Gilead Sciences, paid to her institution.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

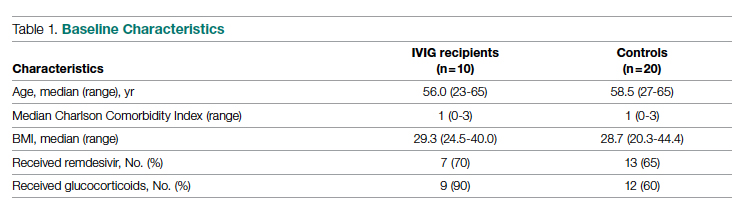

Meet the JCOM Author with Dr. Barkoudah: IVIG in Treating Nonventilated COVID-19 Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Hypoxia

Children & COVID: Rise in new cases slows

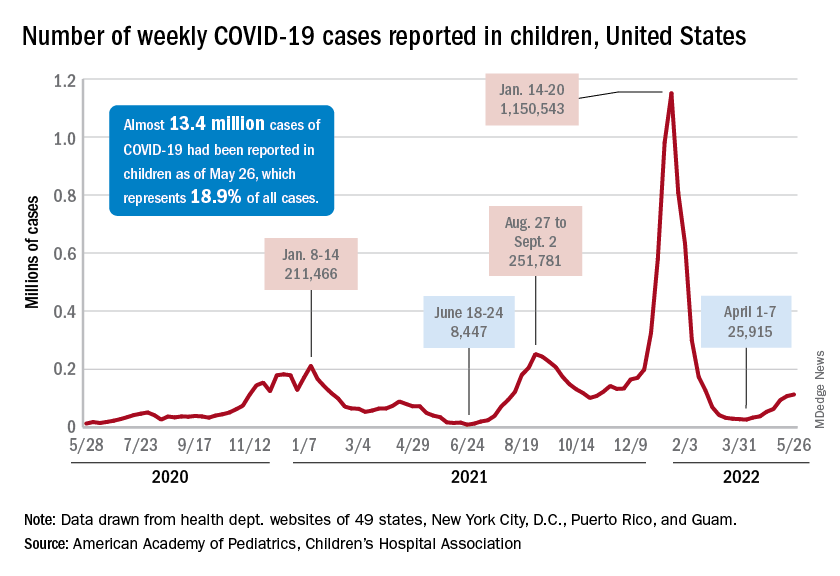

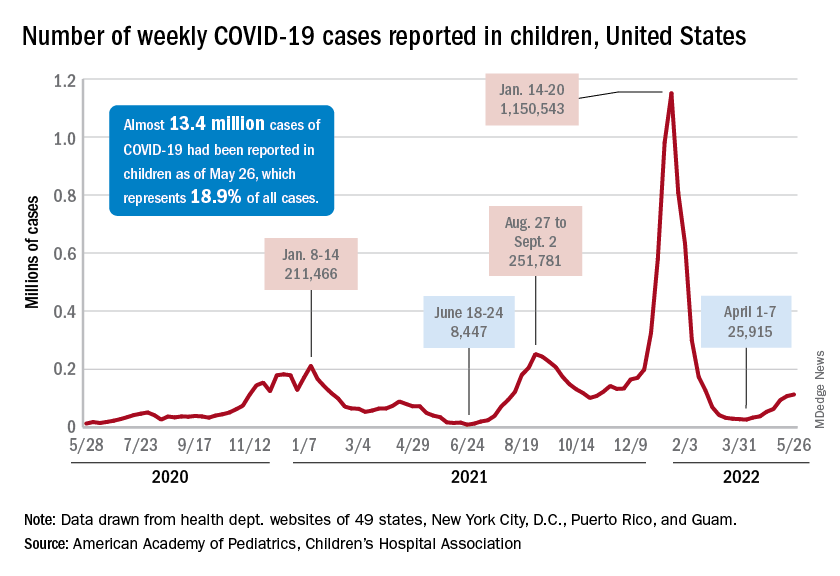

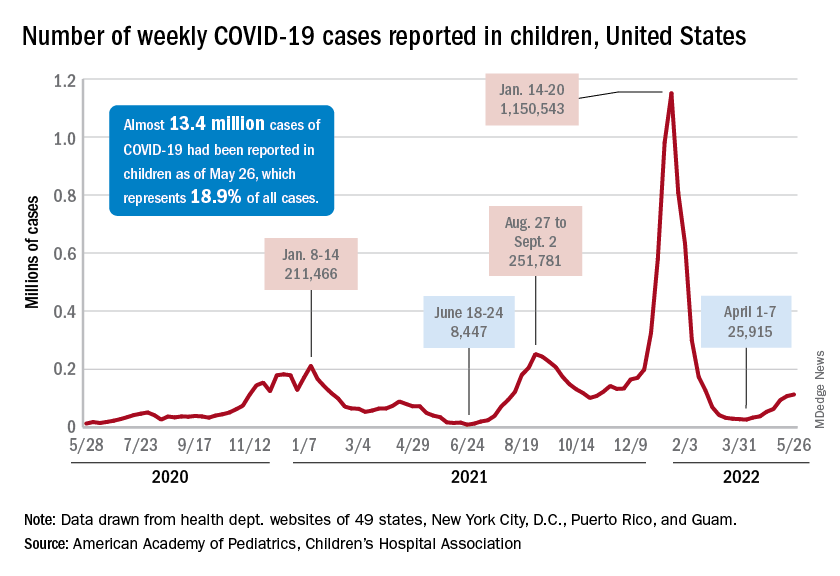

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

New cases of COVID-19 in children climbed for the seventh consecutive week, but the latest increase was the smallest of the seven, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Since the weekly total bottomed out at just under 26,000 in early April, the new-case count has risen by 28.0%, 11.8%, 43.5%, 17.4%, 50%, 14.6%, and 5.0%, based on data from the AAP/CHA weekly COVID-19 report.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is almost 13.4 million since the pandemic began, and those infected children represent 18.9% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said based on data from 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

That 18.9% is noteworthy because it marks the first decline in that particular measure since the AAP and CHA started keeping track in April of 2020. Children’s share of the overall COVID burden had been holding at 19.0% for 14 straight weeks, the AAP/CHA data show.

Regionally, new cases were up in the South and the West, where recent rising trends continued, and down in the Midwest and Northeast, where the recent rising trends were reversed for the first time. At the state/territory level, Puerto Rico had the largest percent increase over the last 2 weeks, followed by Maryland and Delaware, the organizations noted in their joint report.

Hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 have changed little in the last week, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting rates of 0.25 per 100,000 population on May 23 and 0.25 per 100,000 on May 29, the latest date available. There was, however, a move up to 0.26 per 100,000 from May 24 to May 28, and the CDC acknowledges a possible reporting delay over the most recent 7-day period.

Emergency department visits have dipped slightly in recent days, with children aged 0-11 years at a 7-day average of 2.0% of ED visits with diagnosed COVID on May 28, down from a 5-day stretch at 2.2% from May 19 to May 23. Children aged 12-15 years were at 1.8% on May 28, compared with 2.0% on May 23-24, and 15- to 17-year-olds were at 2.0% on May 28, down from the 2.1% reached over the previous 2 days, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

C. diff.: How did a community hospital cut infections by 77%?

Teamwork by a wide range of professional staff, coupled with support from leadership, enabled one academic community hospital to cut its rate of hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infections (HO-CDIs) by almost two-thirds in 1 year and by over three-quarters in 3 years, a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control reports.

C. diff. is a major health threat. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDIs, mainly linked with hospitals, caused an estimated 223,900 cases in hospitalized patients and 12,800 deaths in the United States in 2017.

“The interventions and outcomes of the project improved patient care by ensuring early testing, diagnosis, treatment if warranted, and proper isolation, which helped reduce C. diff. transmission to staff and other patients,” lead study author Cherith Walter, MSN, RN, a clinical nurse specialist at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta, told this news organization. “Had we not worked together as a team, we would not have had the ability to carry out such a robust project,” she added in an email.

Each HO-CDI case costs a health care system an estimated $12,313, and high rates of HO-CDIs incur fines from the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the authors write.

A diverse staff team collaborated

Emory Saint Joseph’s, a 410-bed hospital in Atlanta, had a history of being above the national CMS benchmark for HO-CDIs. To reduce these infections, comply with CMS requirements, and avoid fines, Ms. Walter and colleagues launched a quality improvement project between 2015 and 2020.

With the approval of the chief nursing officer, chief quality officer, and hospital board, researchers mobilized a diverse team of professionals: a clinical nurse specialist, a physician champion, unit nurse champions, a hospital epidemiologist, an infection preventionist, a clinical microbiologist, an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist, and an environmental services representative.

The team investigated what caused their hospital’s HO-CDIs from 2014 through 2016 and developed appropriate, evidence-based infection prevention interventions. The integrated approach involved:

- Diagnostic stewardship, including a diarrhea decision-tree algorithm that enabled nurses to order tests of any loose or unformed stool for C. diff. during the first 3 days of admission.

- Enhanced environmental cleaning, which involved switching from sporicidal disinfectant only in isolation rooms to using a more effective Environmental Protection Agency–approved sporicidal disinfectant containing hydrogen peroxide and peracetic acid in all patient rooms for daily cleaning and after discharge. Every day, high-touch surfaces in C. diff. isolation rooms were cleaned and shared equipment was disinfected with bleach wipes. After patient discharge, staff cleaned mattresses on all sides, wiped walls with disinfectant, and used ultraviolet light.

- Antimicrobial stewardship. Formulary fluoroquinolones were removed as standalone orders and made available only through order sets with built-in clinical decision support.

- Education of staff on best practices, through emails, flyers, meetings, and training sessions. Two nurses needed to approve the appropriateness of testing specific specimens for CDI. All HO-CDIs were reviewed and findings presented at CDI team meetings.

- Accountability. Staff on the team and units received emailed notices about compliance issues and held meetings to discuss how to improve compliance.

After 1 year, HO-CDI incidence dropped 63% from baseline, from above 12 cases per 10,000 patient-days to 4.72 per 10,000 patient-days. And after 3 years, infections dropped 77% to 2.80 per 10,000 patient-days.

The hospital’s HO-CDI standardized infection ratio – the total number of infections divided by the National Healthcare Safety Network’s risk-adjusted predicted number of infections – dropped below the national benchmark, from 1.11 in 2015 to 0.43 in 2020.

The hospital also increased testing of appropriate patients for CDI within the first 3 days of admission, from 54% in 2014 to 81% in late 2019.

“By testing patients within 3 days of admission, we discovered that many had acquired C. diff. before admission,” Ms. Walter said. “I don’t think we realized how prevalent C. diff. was in the community.”

Benjamin D. Galvan, MLS(ASCP), CIC, an infection preventionist at Tampa General Hospital and a member of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, welcomed the study’s results.

“Effective collaboration within the health care setting is a highly effective way to implement and sustain evidence-based practices related to infection reduction. When buy-in is obtained from the top, and pertinent stakeholders are engaged for their expertise, we can see sustainable change and improved patient outcomes,” Mr. Galvan, who was not involved in the study, said in an email.

“The researchers did a fantastic job,” he added. “I am grateful to see this important work addressed in the literature, as it will only improve buy-in for improvement efforts aimed at reducing infections moving forward across the health care continuum.”

Douglas S. Paauw, MD, a professor of medicine and chair for patient-centered clinical education at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said that the team’s most important interventions were changing the environmental cleaning protocol and using agents that kill C. diff. spores.

“We know that as many as 10%-20% of hospitalized patients carry C. diff. Cleaning only the rooms where you know you have C. diff. (isolation rooms) will miss most of it,” said Dr. Paauw, who was also not involved in the study. “Cleaning every room with cleaners that actually work is very important but costs money.”

Handwashing with soap and water works, alcohol hand gels do not

“We know that handwashing with soap and water is the most important way to prevent hospital C. diff. transmission,” Dr. Paauw noted. “Handwashing protocols implemented prior to the study were probably a big part of the team’s success.”

Handwashing with soap and water works but alcohol hand gels do not, he cautioned.