User login

N.Y. governor declares state disaster emergency to boost polio vaccination

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Congenital cytomegalovirus declined in wake of COVID-19

Congenital cytomegalovirus cases declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with a period before the pandemic, based on data from nearly 20,000 newborns.

A study originated to explore racial and ethnic differences in congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) began in 2016, but was halted in April 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, wrote Mark R. Schleiss, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues. The study resumed for a period from August 2020 to December 2021, and the researchers compared data on cCMV before and during the pandemic. The prepandemic period included data from April 2016 to March 2020.

“We have been screening for congenital CMV infection in Minnesota for 6 years as a part of a multicenter collaborative study that I lead as the primary investigator,” Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “Our efforts have contributed to the decision, vetted through the Minnesota Legislature and signed into law in 2021 (the “Vivian Act”), to begin universal screening for all newborns in Minnesota in 2023. In the context of this ongoing screening/surveillance study, it was important and scientifically very interesting to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of congenital CMV infection,” he explained.

The findings were published in a research letter in JAMA Network Open. A total of 15,697 newborns were screened before the pandemic and 4,222 were screened during the pandemic period at six hospitals. The majority of the mothers participating during the prepandemic and pandemic periods were non-Hispanic White (71% and 60%, respectively).

Overall, the percentage screened prevalence for cCMV was 79% in the prepandemic period and 21% during the pandemic, with rates of 4.5 per 1,000 and 1.4 per 1,000, respectively.

Although the highest percentage of cCMV cases occurred in newborns of mothers aged 25 years and older (86%), the prevalence was highest among newborns of mothers aged 24 years and younger (6.0 per 1,000). The prevalence of cCMV overall was higher in infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers vs. non-Hispanic White mothers, but not significantly different (5.1 per 1,000 vs. 4.6 per 1,000) and among second newborns vs. first newborns (6.0 vs. 3.2 per 1,000, respectively).

Factors related to COVID-19, including reduced day care attendance, behavioral changes, and mitigation measures at childcare facilities such as smaller classes and increased hand hygiene and disinfection may have contributed to this decrease in cCMV in the pandemic period, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The comparable prevalence in newborns of non-Hispanic Black and White mothers contrasts with previous studies showing a higher prevalence in children of non-Hispanic Black mothers, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The study was limited by several factors, including the variation in time points for enrollment at different sites and the exclusion of families in the newborn nursery with positive COVID-19 results during the pandemic, they wrote. More research is needed on the potential effects of behavioral interventions to reduce CMV risk during pregnancy, as well as future CMV vaccination for childbearing-aged women and young children, they concluded.

However, the researchers were surprised by the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of cCMV, Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “We have had the knowledge for many years that CMV infections in young women are commonly acquired through interactions with their toddlers. These interactions – sharing food, wiping drool and nasal discharge from the toddler’s nose, changing diapers, kissing the child on the mouth – can transmit CMV,” he said. In addition, toddlers may acquire CMV from group day care; the child then sheds CMV and transmits the virus to their pregnant mother, who then transmits the virus across the placenta, leading to cCMV infection in the newborn, Dr. Schleiss explained.

Although the researchers expected a decrease in CMV in the wake of closures of group day care, increased home schooling, decreased interactions among children, hygienic precautions, and social isolation, the decrease exceeded their expectations, said Dr. Schleiss. “Our previous work showed that in the 5-year period leading up to the pandemic, about one baby in every 200 births was born with CMV. Between August 2020 and December 2021, the number decreased to one baby in every 1,000 births,” a difference he and his team found striking.

The message from the study is that CMV can be prevented, said Dr. Schleiss. “Hygienic precautions during pregnancy had a big impact. Since congenital CMV infection is the most common congenital infection in the United States, and probably globally, that causes disabilities in children, the implications are highly significant,” he said. “The hygienic precautions we all have engaged in during the pandemic, such as masking, handwashing, and infection prevention behaviors, were almost certainly responsible for the reduction in CMV transmission, which in turn protected mothers and newborns from the potentially devastating effects of the CMV virus,” he noted.

Looking ahead, “Vaccines are moving forward in clinical trials that aim to confer immunity on young women of childbearing age to protect future pregnancies against transmission of CMV to the newborn infant; it would be very important to examine in future studies whether hygienic precautions would have the same impact as a potential vaccine,” Dr. Schleiss said. More research is needed to examine the effect of education of women about CMV transmission, he added. “We think it is very important to share this knowledge from our study with the pediatric community, since pediatricians can be important in counseling women about future pregnancies and the risks of CMV acquisition and transmission,” he noted.

Implications for other viruses

Although CMV poses minimal risk for healthy populations, irreversible complications for infants born with congenital CMV, especially hearing loss, are very concerning, said Catherine Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC/PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., in an interview.

“The study of viral transmission during a time of isolation, masking, and other mitigation procedures for COVID-19 assists in awareness that other viruses may also be limited with the use of these measures,” she said.

Dr. Haut was not surprised by the findings, given that CMV is transmitted primarily through direct contact with body fluids and that more than 50% of American adults have been infected by age 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she said.

The take-home message for pediatricians, Dr. Haut said, is measures to prevent transmission of viral infection can yield significant positive health outcomes for the pediatric population; however, the effect of isolation, which has been associated with a higher rate of mental health problems, should not be ignored.

“Despite appropriate statistical analyses and presentation of findings in this study, the population sampled during the pandemic was less than 30% of the pre-COVID sampling, representing a study limitation,” and conducting research in a single state limits generalizability, Dr. Haut noted. “I agree with the authors that additional study is necessary to better understand prevention measures and apply these methods to reduce CMV transmission. Pursuit of CMV immunization opportunities is also needed,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Vaccine Program Office, the Minnesota Department of Health Newborn Screening Program, and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center. Lead author Dr. Schleiss disclosed grants from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the DRDC during the conduct of the study; he also disclosed receiving personal fees from Moderna, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

Congenital cytomegalovirus cases declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with a period before the pandemic, based on data from nearly 20,000 newborns.

A study originated to explore racial and ethnic differences in congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) began in 2016, but was halted in April 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, wrote Mark R. Schleiss, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues. The study resumed for a period from August 2020 to December 2021, and the researchers compared data on cCMV before and during the pandemic. The prepandemic period included data from April 2016 to March 2020.

“We have been screening for congenital CMV infection in Minnesota for 6 years as a part of a multicenter collaborative study that I lead as the primary investigator,” Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “Our efforts have contributed to the decision, vetted through the Minnesota Legislature and signed into law in 2021 (the “Vivian Act”), to begin universal screening for all newborns in Minnesota in 2023. In the context of this ongoing screening/surveillance study, it was important and scientifically very interesting to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of congenital CMV infection,” he explained.

The findings were published in a research letter in JAMA Network Open. A total of 15,697 newborns were screened before the pandemic and 4,222 were screened during the pandemic period at six hospitals. The majority of the mothers participating during the prepandemic and pandemic periods were non-Hispanic White (71% and 60%, respectively).

Overall, the percentage screened prevalence for cCMV was 79% in the prepandemic period and 21% during the pandemic, with rates of 4.5 per 1,000 and 1.4 per 1,000, respectively.

Although the highest percentage of cCMV cases occurred in newborns of mothers aged 25 years and older (86%), the prevalence was highest among newborns of mothers aged 24 years and younger (6.0 per 1,000). The prevalence of cCMV overall was higher in infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers vs. non-Hispanic White mothers, but not significantly different (5.1 per 1,000 vs. 4.6 per 1,000) and among second newborns vs. first newborns (6.0 vs. 3.2 per 1,000, respectively).

Factors related to COVID-19, including reduced day care attendance, behavioral changes, and mitigation measures at childcare facilities such as smaller classes and increased hand hygiene and disinfection may have contributed to this decrease in cCMV in the pandemic period, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The comparable prevalence in newborns of non-Hispanic Black and White mothers contrasts with previous studies showing a higher prevalence in children of non-Hispanic Black mothers, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The study was limited by several factors, including the variation in time points for enrollment at different sites and the exclusion of families in the newborn nursery with positive COVID-19 results during the pandemic, they wrote. More research is needed on the potential effects of behavioral interventions to reduce CMV risk during pregnancy, as well as future CMV vaccination for childbearing-aged women and young children, they concluded.

However, the researchers were surprised by the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of cCMV, Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “We have had the knowledge for many years that CMV infections in young women are commonly acquired through interactions with their toddlers. These interactions – sharing food, wiping drool and nasal discharge from the toddler’s nose, changing diapers, kissing the child on the mouth – can transmit CMV,” he said. In addition, toddlers may acquire CMV from group day care; the child then sheds CMV and transmits the virus to their pregnant mother, who then transmits the virus across the placenta, leading to cCMV infection in the newborn, Dr. Schleiss explained.

Although the researchers expected a decrease in CMV in the wake of closures of group day care, increased home schooling, decreased interactions among children, hygienic precautions, and social isolation, the decrease exceeded their expectations, said Dr. Schleiss. “Our previous work showed that in the 5-year period leading up to the pandemic, about one baby in every 200 births was born with CMV. Between August 2020 and December 2021, the number decreased to one baby in every 1,000 births,” a difference he and his team found striking.

The message from the study is that CMV can be prevented, said Dr. Schleiss. “Hygienic precautions during pregnancy had a big impact. Since congenital CMV infection is the most common congenital infection in the United States, and probably globally, that causes disabilities in children, the implications are highly significant,” he said. “The hygienic precautions we all have engaged in during the pandemic, such as masking, handwashing, and infection prevention behaviors, were almost certainly responsible for the reduction in CMV transmission, which in turn protected mothers and newborns from the potentially devastating effects of the CMV virus,” he noted.

Looking ahead, “Vaccines are moving forward in clinical trials that aim to confer immunity on young women of childbearing age to protect future pregnancies against transmission of CMV to the newborn infant; it would be very important to examine in future studies whether hygienic precautions would have the same impact as a potential vaccine,” Dr. Schleiss said. More research is needed to examine the effect of education of women about CMV transmission, he added. “We think it is very important to share this knowledge from our study with the pediatric community, since pediatricians can be important in counseling women about future pregnancies and the risks of CMV acquisition and transmission,” he noted.

Implications for other viruses

Although CMV poses minimal risk for healthy populations, irreversible complications for infants born with congenital CMV, especially hearing loss, are very concerning, said Catherine Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC/PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., in an interview.

“The study of viral transmission during a time of isolation, masking, and other mitigation procedures for COVID-19 assists in awareness that other viruses may also be limited with the use of these measures,” she said.

Dr. Haut was not surprised by the findings, given that CMV is transmitted primarily through direct contact with body fluids and that more than 50% of American adults have been infected by age 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she said.

The take-home message for pediatricians, Dr. Haut said, is measures to prevent transmission of viral infection can yield significant positive health outcomes for the pediatric population; however, the effect of isolation, which has been associated with a higher rate of mental health problems, should not be ignored.

“Despite appropriate statistical analyses and presentation of findings in this study, the population sampled during the pandemic was less than 30% of the pre-COVID sampling, representing a study limitation,” and conducting research in a single state limits generalizability, Dr. Haut noted. “I agree with the authors that additional study is necessary to better understand prevention measures and apply these methods to reduce CMV transmission. Pursuit of CMV immunization opportunities is also needed,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Vaccine Program Office, the Minnesota Department of Health Newborn Screening Program, and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center. Lead author Dr. Schleiss disclosed grants from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the DRDC during the conduct of the study; he also disclosed receiving personal fees from Moderna, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

Congenital cytomegalovirus cases declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with a period before the pandemic, based on data from nearly 20,000 newborns.

A study originated to explore racial and ethnic differences in congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) began in 2016, but was halted in April 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, wrote Mark R. Schleiss, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues. The study resumed for a period from August 2020 to December 2021, and the researchers compared data on cCMV before and during the pandemic. The prepandemic period included data from April 2016 to March 2020.

“We have been screening for congenital CMV infection in Minnesota for 6 years as a part of a multicenter collaborative study that I lead as the primary investigator,” Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “Our efforts have contributed to the decision, vetted through the Minnesota Legislature and signed into law in 2021 (the “Vivian Act”), to begin universal screening for all newborns in Minnesota in 2023. In the context of this ongoing screening/surveillance study, it was important and scientifically very interesting to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of congenital CMV infection,” he explained.

The findings were published in a research letter in JAMA Network Open. A total of 15,697 newborns were screened before the pandemic and 4,222 were screened during the pandemic period at six hospitals. The majority of the mothers participating during the prepandemic and pandemic periods were non-Hispanic White (71% and 60%, respectively).

Overall, the percentage screened prevalence for cCMV was 79% in the prepandemic period and 21% during the pandemic, with rates of 4.5 per 1,000 and 1.4 per 1,000, respectively.

Although the highest percentage of cCMV cases occurred in newborns of mothers aged 25 years and older (86%), the prevalence was highest among newborns of mothers aged 24 years and younger (6.0 per 1,000). The prevalence of cCMV overall was higher in infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers vs. non-Hispanic White mothers, but not significantly different (5.1 per 1,000 vs. 4.6 per 1,000) and among second newborns vs. first newborns (6.0 vs. 3.2 per 1,000, respectively).

Factors related to COVID-19, including reduced day care attendance, behavioral changes, and mitigation measures at childcare facilities such as smaller classes and increased hand hygiene and disinfection may have contributed to this decrease in cCMV in the pandemic period, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The comparable prevalence in newborns of non-Hispanic Black and White mothers contrasts with previous studies showing a higher prevalence in children of non-Hispanic Black mothers, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The study was limited by several factors, including the variation in time points for enrollment at different sites and the exclusion of families in the newborn nursery with positive COVID-19 results during the pandemic, they wrote. More research is needed on the potential effects of behavioral interventions to reduce CMV risk during pregnancy, as well as future CMV vaccination for childbearing-aged women and young children, they concluded.

However, the researchers were surprised by the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of cCMV, Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “We have had the knowledge for many years that CMV infections in young women are commonly acquired through interactions with their toddlers. These interactions – sharing food, wiping drool and nasal discharge from the toddler’s nose, changing diapers, kissing the child on the mouth – can transmit CMV,” he said. In addition, toddlers may acquire CMV from group day care; the child then sheds CMV and transmits the virus to their pregnant mother, who then transmits the virus across the placenta, leading to cCMV infection in the newborn, Dr. Schleiss explained.

Although the researchers expected a decrease in CMV in the wake of closures of group day care, increased home schooling, decreased interactions among children, hygienic precautions, and social isolation, the decrease exceeded their expectations, said Dr. Schleiss. “Our previous work showed that in the 5-year period leading up to the pandemic, about one baby in every 200 births was born with CMV. Between August 2020 and December 2021, the number decreased to one baby in every 1,000 births,” a difference he and his team found striking.

The message from the study is that CMV can be prevented, said Dr. Schleiss. “Hygienic precautions during pregnancy had a big impact. Since congenital CMV infection is the most common congenital infection in the United States, and probably globally, that causes disabilities in children, the implications are highly significant,” he said. “The hygienic precautions we all have engaged in during the pandemic, such as masking, handwashing, and infection prevention behaviors, were almost certainly responsible for the reduction in CMV transmission, which in turn protected mothers and newborns from the potentially devastating effects of the CMV virus,” he noted.

Looking ahead, “Vaccines are moving forward in clinical trials that aim to confer immunity on young women of childbearing age to protect future pregnancies against transmission of CMV to the newborn infant; it would be very important to examine in future studies whether hygienic precautions would have the same impact as a potential vaccine,” Dr. Schleiss said. More research is needed to examine the effect of education of women about CMV transmission, he added. “We think it is very important to share this knowledge from our study with the pediatric community, since pediatricians can be important in counseling women about future pregnancies and the risks of CMV acquisition and transmission,” he noted.

Implications for other viruses

Although CMV poses minimal risk for healthy populations, irreversible complications for infants born with congenital CMV, especially hearing loss, are very concerning, said Catherine Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC/PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., in an interview.

“The study of viral transmission during a time of isolation, masking, and other mitigation procedures for COVID-19 assists in awareness that other viruses may also be limited with the use of these measures,” she said.

Dr. Haut was not surprised by the findings, given that CMV is transmitted primarily through direct contact with body fluids and that more than 50% of American adults have been infected by age 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she said.

The take-home message for pediatricians, Dr. Haut said, is measures to prevent transmission of viral infection can yield significant positive health outcomes for the pediatric population; however, the effect of isolation, which has been associated with a higher rate of mental health problems, should not be ignored.

“Despite appropriate statistical analyses and presentation of findings in this study, the population sampled during the pandemic was less than 30% of the pre-COVID sampling, representing a study limitation,” and conducting research in a single state limits generalizability, Dr. Haut noted. “I agree with the authors that additional study is necessary to better understand prevention measures and apply these methods to reduce CMV transmission. Pursuit of CMV immunization opportunities is also needed,” she said.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Vaccine Program Office, the Minnesota Department of Health Newborn Screening Program, and the University of South Carolina Disability Research and Dissemination Center. Lead author Dr. Schleiss disclosed grants from the CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the DRDC during the conduct of the study; he also disclosed receiving personal fees from Moderna, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Pediatric vaccines & infectious diseases, 2022

Introduction

ICYMI articles featuring 9 important developments of the past year – and COVID is still here

By Christopher J. Harrison, MD

Table of contents

Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

Commentary

Emerging tick-borne pathogen has spread to state of Georgia

Commentary

WHO, UNICEF warn about increased risk of measles outbreaks

Commentary

Babies die as congenital syphilis continues a decade-long surge across the U.S.

Commentary

Meningococcal vaccine shows moderate protective effect against gonorrhea

Commentary

Adolescents are undertested for STIs

Commentary

TB treatment can be shortened for most children: Study

Commentary

Nirsevimab protects healthy infants from RSV

Commentary

Norovirus vaccine candidates employ different approaches

Commentary

Introduction

ICYMI articles featuring 9 important developments of the past year – and COVID is still here

By Christopher J. Harrison, MD

Table of contents

Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

Commentary

Emerging tick-borne pathogen has spread to state of Georgia

Commentary

WHO, UNICEF warn about increased risk of measles outbreaks

Commentary

Babies die as congenital syphilis continues a decade-long surge across the U.S.

Commentary

Meningococcal vaccine shows moderate protective effect against gonorrhea

Commentary

Adolescents are undertested for STIs

Commentary

TB treatment can be shortened for most children: Study

Commentary

Nirsevimab protects healthy infants from RSV

Commentary

Norovirus vaccine candidates employ different approaches

Commentary

Introduction

ICYMI articles featuring 9 important developments of the past year – and COVID is still here

By Christopher J. Harrison, MD

Table of contents

Antibiotics use and vaccine antibody levels

Commentary

Emerging tick-borne pathogen has spread to state of Georgia

Commentary

WHO, UNICEF warn about increased risk of measles outbreaks

Commentary

Babies die as congenital syphilis continues a decade-long surge across the U.S.

Commentary

Meningococcal vaccine shows moderate protective effect against gonorrhea

Commentary

Adolescents are undertested for STIs

Commentary

TB treatment can be shortened for most children: Study

Commentary

Nirsevimab protects healthy infants from RSV

Commentary

Norovirus vaccine candidates employ different approaches

Commentary

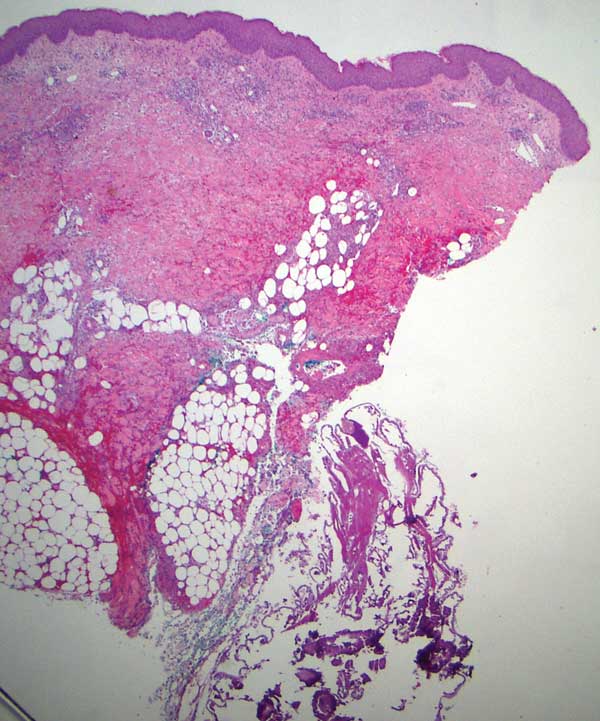

Catheter-Directed Retrieval of an Infected Fragment in a Vietnam War Veteran

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

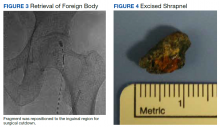

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

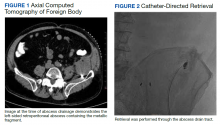

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

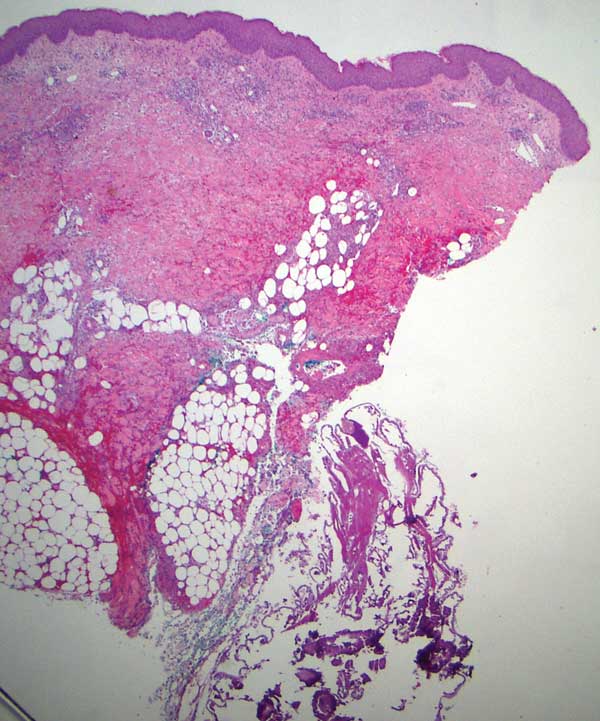

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

Texas district court allows employers to deny HIV PrEP coverage

Fort Worth, Tex. – A case decision made by Texas U.S. District Judge Reed Charles O’Connor that will allow employers to deny health care insurance coverage for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is already provoking HIV activists, medical associations, nonprofits, and patients.

As this news organization first reported in August, the class action suit (Kelley v. Azar) has a broader goal – to dismantle the Affordable Care Act using the argument that many of the preventive services it covers, including PrEP, violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

“Judge O’Connor has a long history of issuing rulings against the Affordable Care Act and LGBT individuals, and we expect the case to be successfully appealed as has been the case with his previous discriminatory decisions,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute in Washington, in a prepared statement issued shortly after the ruling.

“To single out PrEP, which are FDA approved drugs that effectively prevent HIV, and conclude that its coverage violates the religious freedom of certain individuals, is plain wrong, highly discriminatory, and impedes the public health of our nation,” he said.

PrEP is not just for men who have sex with men. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 1 million Americans could benefit from PrEP, and roughly 20% are heterosexual women – a fact both Mr. Schmid and the HIV Medicine Association pointed out in response to Judge O’Connor’s ruling.

“Denying access to PrEP threatens the health of more than 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from this potentially life saving intervention,” stated Marwan Haddad, MD, MPH, chair of the HIV Medicine Association, in a press release issued by the organization.

“This ruling is yet one more instance of unacceptable interference in scientific, evidence-based health care practices that must remain within the sanctity of the provider-patient relationship,” she said.

The ruling is also outside what is normally considered religious “conscientious objection.”

While the American Medical Association supports the rights of physicians to act in accordance with conscience, medical ethicists like Abram Brummett, PhD, assistant professor, department of foundational medical studies, Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., previously told this news organization that this ruling actually reflects a phenomenon known as “conscience creep” – that is, the way conscientious objection creeps outside traditional contexts like abortion, sterilization, and organ transplantation.

Incidentally, the case is not yet completed; Judge O’Connor still has to decide on challenges to contraceptives and HPV mandates. He has requested that defendants and plaintiffs file a supplemental briefing before he makes a final decision.

Regardless of how it plays out, it is unclear whether the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fort Worth, Tex. – A case decision made by Texas U.S. District Judge Reed Charles O’Connor that will allow employers to deny health care insurance coverage for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is already provoking HIV activists, medical associations, nonprofits, and patients.

As this news organization first reported in August, the class action suit (Kelley v. Azar) has a broader goal – to dismantle the Affordable Care Act using the argument that many of the preventive services it covers, including PrEP, violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

“Judge O’Connor has a long history of issuing rulings against the Affordable Care Act and LGBT individuals, and we expect the case to be successfully appealed as has been the case with his previous discriminatory decisions,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute in Washington, in a prepared statement issued shortly after the ruling.

“To single out PrEP, which are FDA approved drugs that effectively prevent HIV, and conclude that its coverage violates the religious freedom of certain individuals, is plain wrong, highly discriminatory, and impedes the public health of our nation,” he said.

PrEP is not just for men who have sex with men. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 1 million Americans could benefit from PrEP, and roughly 20% are heterosexual women – a fact both Mr. Schmid and the HIV Medicine Association pointed out in response to Judge O’Connor’s ruling.

“Denying access to PrEP threatens the health of more than 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from this potentially life saving intervention,” stated Marwan Haddad, MD, MPH, chair of the HIV Medicine Association, in a press release issued by the organization.

“This ruling is yet one more instance of unacceptable interference in scientific, evidence-based health care practices that must remain within the sanctity of the provider-patient relationship,” she said.

The ruling is also outside what is normally considered religious “conscientious objection.”

While the American Medical Association supports the rights of physicians to act in accordance with conscience, medical ethicists like Abram Brummett, PhD, assistant professor, department of foundational medical studies, Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., previously told this news organization that this ruling actually reflects a phenomenon known as “conscience creep” – that is, the way conscientious objection creeps outside traditional contexts like abortion, sterilization, and organ transplantation.

Incidentally, the case is not yet completed; Judge O’Connor still has to decide on challenges to contraceptives and HPV mandates. He has requested that defendants and plaintiffs file a supplemental briefing before he makes a final decision.

Regardless of how it plays out, it is unclear whether the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fort Worth, Tex. – A case decision made by Texas U.S. District Judge Reed Charles O’Connor that will allow employers to deny health care insurance coverage for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is already provoking HIV activists, medical associations, nonprofits, and patients.

As this news organization first reported in August, the class action suit (Kelley v. Azar) has a broader goal – to dismantle the Affordable Care Act using the argument that many of the preventive services it covers, including PrEP, violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

“Judge O’Connor has a long history of issuing rulings against the Affordable Care Act and LGBT individuals, and we expect the case to be successfully appealed as has been the case with his previous discriminatory decisions,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute in Washington, in a prepared statement issued shortly after the ruling.

“To single out PrEP, which are FDA approved drugs that effectively prevent HIV, and conclude that its coverage violates the religious freedom of certain individuals, is plain wrong, highly discriminatory, and impedes the public health of our nation,” he said.

PrEP is not just for men who have sex with men. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 1 million Americans could benefit from PrEP, and roughly 20% are heterosexual women – a fact both Mr. Schmid and the HIV Medicine Association pointed out in response to Judge O’Connor’s ruling.

“Denying access to PrEP threatens the health of more than 1.2 million Americans who could benefit from this potentially life saving intervention,” stated Marwan Haddad, MD, MPH, chair of the HIV Medicine Association, in a press release issued by the organization.

“This ruling is yet one more instance of unacceptable interference in scientific, evidence-based health care practices that must remain within the sanctity of the provider-patient relationship,” she said.

The ruling is also outside what is normally considered religious “conscientious objection.”

While the American Medical Association supports the rights of physicians to act in accordance with conscience, medical ethicists like Abram Brummett, PhD, assistant professor, department of foundational medical studies, Oakland University, Rochester, Mich., previously told this news organization that this ruling actually reflects a phenomenon known as “conscience creep” – that is, the way conscientious objection creeps outside traditional contexts like abortion, sterilization, and organ transplantation.

Incidentally, the case is not yet completed; Judge O’Connor still has to decide on challenges to contraceptives and HPV mandates. He has requested that defendants and plaintiffs file a supplemental briefing before he makes a final decision.

Regardless of how it plays out, it is unclear whether the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will appeal.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza vaccine may offer much more than flu prevention

in new findings that suggest the vaccine itself, and not just avoidance of the virus, may be beneficial.

“We postulate that influenza vaccination may have a protective effect against stroke that may be partly independent of influenza prevention,” study investigator Francisco J. de Abajo, MD, PhD, MPH, of the University of Alcalá, Madrid, said in an interview.

“Although the study is observational and this finding can also be explained by unmeasured confounding factors, we feel that a direct biological effect of vaccine cannot be ruled out and this finding opens new avenues for investigation.”

The study was published online in Neurology.

‘Not a spurious association’

While there is a well-established link between seasonal influenza and increased ischemic stroke risk, the role of flu vaccination in stroke prevention is unclear.

In the nested case-control study, researchers evaluated data from primary care practices in Spain between 2001 and 2015. They identified 14,322 patients with first-time ischemic stroke. Of these, 9,542 had noncardioembolic stroke and 4,780 had cardioembolic stroke.

Each case was matched with five controls from the population of age- and sex-matched controls without stroke (n = 71,610).

Those in the stroke group had a slightly higher rate of flu vaccination than controls, at 41.4% versus 40.5% (odds ratio, 1.05).

Adjusted analysis revealed those who received flu vaccination were less likely to experience ischemic stroke within 15-30 days of vaccination (OR, 0.79) and, to a lesser degree, over up to 150 days (OR, 0.92).

The reduced risk associated with the flu vaccine was observed with both types of ischemic stroke and appeared to offer stroke protection outside of flu season.

The reduced risk was also found in subgroup comparisons in men, women, those aged over and under 65 years, and those with intermediate and high vascular risk.

Importantly, a separate analysis of pneumococcal vaccination did not show a similar reduction in stroke risk (adjusted OR, 1.08).

“The lack of protection found with the pneumococcal vaccine actually reinforces the hypothesis that the protection of influenza vaccine is not a spurious association, as both vaccines might share the same biases and confounding factors,” Dr. de Abajo said.

Anti-inflammatory effect?

Influenza infection is known to induce a systemic inflammatory response that “can precipitate atheroma plaque rupture mediated by elevated concentrations of reactive proteins and cytokines,” the investigators noted, and so, avoiding infection could prevent those effects.

The results are consistent with other studies that have shown similar findings, including recent data from the INTERSTROKE trial. However, the reduced risk observed in the current study even in years without a flu epidemic expands on previous findings.

“This finding suggests that other mechanisms different from the prevention of influenza infection – e.g., a direct biological effect – could account for the risk reduction found,” the investigators wrote.

In terms of the nature of that effect, Dr. de Abajo noted that, “at this stage, we can only speculate.

“Having said that, there are some pieces of evidence that suggest influenza vaccination may release anti-inflammatory mediators that can stabilize the atheroma plaque. This is an interesting hypothesis that should be addressed in the near future,” he added.

‘More than just flu prevention’

In an accompanying editorial, Dixon Yang, MD, and Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, agree that the findings point to intriguing potential unexpected benefits of the vaccine.

“This case-control study ... importantly suggests the influenza vaccine is more than just about preventing the flu,” they wrote.

Dr. Elkind said in an interview that the mechanism could indeed involve an anti-inflammatory effect.

“There is some evidence that antibiotics also have anti-inflammatory properties that might reduce risk of stroke or the brain damage from a stroke,” he noted. “So, it is plausible that some of the effect of the vaccine on reducing risk of stroke may be through a reduction in inflammation.”

Dr. Elkind noted that the magnitude of the reduction observed with the vaccine, though not substantial, is important. “The magnitude of effect for any one individual may be modest, but it is in the ballpark of the effect of other commonly used approaches to stroke prevention, such as taking an aspirin a day, which reduces risk of stroke by about 20%. But because influenza is so common, the impact of even a small effect for an individual can have a large impact at the population level. So, the results are of public health significance.”

The study received support from the Biomedical Research Foundation of the Prince of Asturias University Hospital and the Institute of Health Carlos III in Madrid. Dr. Elkind has reported receiving ancillary funding but no personal compensation from Roche for a federally funded trial of stroke prevention.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in new findings that suggest the vaccine itself, and not just avoidance of the virus, may be beneficial.

“We postulate that influenza vaccination may have a protective effect against stroke that may be partly independent of influenza prevention,” study investigator Francisco J. de Abajo, MD, PhD, MPH, of the University of Alcalá, Madrid, said in an interview.