User login

HHS effort aims to end new HIV cases within 10 years

WASHINGTON – Leaders from five federal agencies came together to announce the framework for a bold new national initiative that aims to eliminate new cases of HIV infection in the United States within 10 years. The announcement came the day after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which highlighted the new effort.

“HIV has cost America too much for too long,” said Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health at the Department of Health & Human Services, in a press briefing. In addition to the 700,000 U.S. lives the disease has claimed since 1981, “We are at high risk of another 400,000 becoming infected over the next decade,” with about 40,000 new infections still occurring every year, he said.

Dr. Giroir will lead a coordinated effort among HHS, the Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Indian Health Service. The goals are to reduce new cases of HIV by 50% within 5 years, and by 90% within 10 years.

These 48 counties, together with Washington and San Juan, Puerto Rico, accounted for more than half of the new HIV diagnoses in 2016 and 2017, said Dr. Giroir.

“This is a laser-focused program targeting counties where infection is the highest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “We propose to deploy personnel, resources, and strategies” in these targeted areas to maximize not just diagnosis and treatment but also to reach those at risk for HIV to enroll them in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens, he said.

In addition to the targeted counties, seven states in the rural South as well as Native American and Alaskan Native populations also will receive intensified education, diagnostic, and treatment services. The targeted states are Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

George Sigounas, PhD, administrator or the Health Resources and Services Administration, said that existing community health centers will be especially important in reaching rural underserved and marginalized populations. Currently, he said, HRSA supports 12,000 service delivery sites across the country that are already delivering care to 27 million individuals. “These sites will play a major expanded role in providing PrEP to those who are at the greatest risk of contracting HIV,” said Dr. Sigounas.

Among the currently existing resources that will be leveraged are services provided by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, which already provides HIV primary medical care and support services through a network of grants to states and local government and community organizations. About half of the people currently diagnosed with HIV in the United States receive services through this program now.

The NIH maintains a geographically distributed network of Centers for AIDS Research that also will be folded into the new initiative.

In his remarks, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the NIH’s National Center for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, pointed out that, “Treatment and detection are wrapped together, because treated individuals can’t transmit HIV” if they are adherent to antiretroviral medication use and achieve an undetectable viral load, he said. “If you get everyone who’s infected on antiretrovirals and give those who need it PrEP, you can theoretically end the epidemic as we know it – and that is our goal.”

Dr. Fauci went on to say that implementation science will play a key role in achieving a targeted and coordinated approach. “We will work closely with our colleagues to make sure the implementation is done well. We have lessons learned; we will do better and better,” he said.

The nuts and bolts of the program include a four-pronged strategy to diagnose individuals as early as possible after infection, to initiate prompt, effective, and sustained treatment, to protect those at risk for HIV by proven means including PrEP, and to provide rapid response when new HIV clusters are identified. A reimagining of current and future personnel into an “HIV health force” will put teams on the ground in each jurisdiction to carry out the initiative.

Though the goal is to provide PrEP to every at-risk individual, Dr. Fauci said that current modeling shows that if PrEP reaches 50%-60% in the at-risk population, new infections can be reduced by 90%. He added, “PrEP works. The efficacy is well over 90%.”

Funding details were not released at the press briefing; Dr. Giroir said that figures will be released by the Office of Management and Budget as part of the 2020 budget cycle. He confirmed, however, that new funds will be allocated for the effort, rather than a mere reshuffling of existing fund and resources.

Several of the leaders acknowledged the problem of stigma and marginalization that many individuals living with or at risk for HIV face, since men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, and those with opioid use disorder all fall into this category.

“Every American deserves to be treated with respect and dignity. We will vigorously enforce all laws on the books about discrimination,” said Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, MD, principal deputy director of the Indian Health Service. This is especially important in Native American communities “where everybody knows everybody,” he said, and it’s vitally important to include individual and community education in the efforts.

Dr. Redfield concurred, adding that “Dr. Fauci and I have been engaged in HIV since 1981. We have witnessed firsthand the negative impact that stigma can have on our capacity to practice public health. The transgender population, in particular, needs to be reached out to. We need to be able to address in a comprehensive way how to destigmatize the HIV population.”

WASHINGTON – Leaders from five federal agencies came together to announce the framework for a bold new national initiative that aims to eliminate new cases of HIV infection in the United States within 10 years. The announcement came the day after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which highlighted the new effort.

“HIV has cost America too much for too long,” said Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health at the Department of Health & Human Services, in a press briefing. In addition to the 700,000 U.S. lives the disease has claimed since 1981, “We are at high risk of another 400,000 becoming infected over the next decade,” with about 40,000 new infections still occurring every year, he said.

Dr. Giroir will lead a coordinated effort among HHS, the Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Indian Health Service. The goals are to reduce new cases of HIV by 50% within 5 years, and by 90% within 10 years.

These 48 counties, together with Washington and San Juan, Puerto Rico, accounted for more than half of the new HIV diagnoses in 2016 and 2017, said Dr. Giroir.

“This is a laser-focused program targeting counties where infection is the highest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “We propose to deploy personnel, resources, and strategies” in these targeted areas to maximize not just diagnosis and treatment but also to reach those at risk for HIV to enroll them in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens, he said.

In addition to the targeted counties, seven states in the rural South as well as Native American and Alaskan Native populations also will receive intensified education, diagnostic, and treatment services. The targeted states are Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

George Sigounas, PhD, administrator or the Health Resources and Services Administration, said that existing community health centers will be especially important in reaching rural underserved and marginalized populations. Currently, he said, HRSA supports 12,000 service delivery sites across the country that are already delivering care to 27 million individuals. “These sites will play a major expanded role in providing PrEP to those who are at the greatest risk of contracting HIV,” said Dr. Sigounas.

Among the currently existing resources that will be leveraged are services provided by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, which already provides HIV primary medical care and support services through a network of grants to states and local government and community organizations. About half of the people currently diagnosed with HIV in the United States receive services through this program now.

The NIH maintains a geographically distributed network of Centers for AIDS Research that also will be folded into the new initiative.

In his remarks, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the NIH’s National Center for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, pointed out that, “Treatment and detection are wrapped together, because treated individuals can’t transmit HIV” if they are adherent to antiretroviral medication use and achieve an undetectable viral load, he said. “If you get everyone who’s infected on antiretrovirals and give those who need it PrEP, you can theoretically end the epidemic as we know it – and that is our goal.”

Dr. Fauci went on to say that implementation science will play a key role in achieving a targeted and coordinated approach. “We will work closely with our colleagues to make sure the implementation is done well. We have lessons learned; we will do better and better,” he said.

The nuts and bolts of the program include a four-pronged strategy to diagnose individuals as early as possible after infection, to initiate prompt, effective, and sustained treatment, to protect those at risk for HIV by proven means including PrEP, and to provide rapid response when new HIV clusters are identified. A reimagining of current and future personnel into an “HIV health force” will put teams on the ground in each jurisdiction to carry out the initiative.

Though the goal is to provide PrEP to every at-risk individual, Dr. Fauci said that current modeling shows that if PrEP reaches 50%-60% in the at-risk population, new infections can be reduced by 90%. He added, “PrEP works. The efficacy is well over 90%.”

Funding details were not released at the press briefing; Dr. Giroir said that figures will be released by the Office of Management and Budget as part of the 2020 budget cycle. He confirmed, however, that new funds will be allocated for the effort, rather than a mere reshuffling of existing fund and resources.

Several of the leaders acknowledged the problem of stigma and marginalization that many individuals living with or at risk for HIV face, since men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, and those with opioid use disorder all fall into this category.

“Every American deserves to be treated with respect and dignity. We will vigorously enforce all laws on the books about discrimination,” said Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, MD, principal deputy director of the Indian Health Service. This is especially important in Native American communities “where everybody knows everybody,” he said, and it’s vitally important to include individual and community education in the efforts.

Dr. Redfield concurred, adding that “Dr. Fauci and I have been engaged in HIV since 1981. We have witnessed firsthand the negative impact that stigma can have on our capacity to practice public health. The transgender population, in particular, needs to be reached out to. We need to be able to address in a comprehensive way how to destigmatize the HIV population.”

WASHINGTON – Leaders from five federal agencies came together to announce the framework for a bold new national initiative that aims to eliminate new cases of HIV infection in the United States within 10 years. The announcement came the day after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which highlighted the new effort.

“HIV has cost America too much for too long,” said Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health at the Department of Health & Human Services, in a press briefing. In addition to the 700,000 U.S. lives the disease has claimed since 1981, “We are at high risk of another 400,000 becoming infected over the next decade,” with about 40,000 new infections still occurring every year, he said.

Dr. Giroir will lead a coordinated effort among HHS, the Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Indian Health Service. The goals are to reduce new cases of HIV by 50% within 5 years, and by 90% within 10 years.

These 48 counties, together with Washington and San Juan, Puerto Rico, accounted for more than half of the new HIV diagnoses in 2016 and 2017, said Dr. Giroir.

“This is a laser-focused program targeting counties where infection is the highest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “We propose to deploy personnel, resources, and strategies” in these targeted areas to maximize not just diagnosis and treatment but also to reach those at risk for HIV to enroll them in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) regimens, he said.

In addition to the targeted counties, seven states in the rural South as well as Native American and Alaskan Native populations also will receive intensified education, diagnostic, and treatment services. The targeted states are Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

George Sigounas, PhD, administrator or the Health Resources and Services Administration, said that existing community health centers will be especially important in reaching rural underserved and marginalized populations. Currently, he said, HRSA supports 12,000 service delivery sites across the country that are already delivering care to 27 million individuals. “These sites will play a major expanded role in providing PrEP to those who are at the greatest risk of contracting HIV,” said Dr. Sigounas.

Among the currently existing resources that will be leveraged are services provided by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, which already provides HIV primary medical care and support services through a network of grants to states and local government and community organizations. About half of the people currently diagnosed with HIV in the United States receive services through this program now.

The NIH maintains a geographically distributed network of Centers for AIDS Research that also will be folded into the new initiative.

In his remarks, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the NIH’s National Center for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, pointed out that, “Treatment and detection are wrapped together, because treated individuals can’t transmit HIV” if they are adherent to antiretroviral medication use and achieve an undetectable viral load, he said. “If you get everyone who’s infected on antiretrovirals and give those who need it PrEP, you can theoretically end the epidemic as we know it – and that is our goal.”

Dr. Fauci went on to say that implementation science will play a key role in achieving a targeted and coordinated approach. “We will work closely with our colleagues to make sure the implementation is done well. We have lessons learned; we will do better and better,” he said.

The nuts and bolts of the program include a four-pronged strategy to diagnose individuals as early as possible after infection, to initiate prompt, effective, and sustained treatment, to protect those at risk for HIV by proven means including PrEP, and to provide rapid response when new HIV clusters are identified. A reimagining of current and future personnel into an “HIV health force” will put teams on the ground in each jurisdiction to carry out the initiative.

Though the goal is to provide PrEP to every at-risk individual, Dr. Fauci said that current modeling shows that if PrEP reaches 50%-60% in the at-risk population, new infections can be reduced by 90%. He added, “PrEP works. The efficacy is well over 90%.”

Funding details were not released at the press briefing; Dr. Giroir said that figures will be released by the Office of Management and Budget as part of the 2020 budget cycle. He confirmed, however, that new funds will be allocated for the effort, rather than a mere reshuffling of existing fund and resources.

Several of the leaders acknowledged the problem of stigma and marginalization that many individuals living with or at risk for HIV face, since men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, and those with opioid use disorder all fall into this category.

“Every American deserves to be treated with respect and dignity. We will vigorously enforce all laws on the books about discrimination,” said Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, MD, principal deputy director of the Indian Health Service. This is especially important in Native American communities “where everybody knows everybody,” he said, and it’s vitally important to include individual and community education in the efforts.

Dr. Redfield concurred, adding that “Dr. Fauci and I have been engaged in HIV since 1981. We have witnessed firsthand the negative impact that stigma can have on our capacity to practice public health. The transgender population, in particular, needs to be reached out to. We need to be able to address in a comprehensive way how to destigmatize the HIV population.”

FROM A HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES BRIEFING

President Trump calls for end to HIV/AIDS, pediatric cancer

HIV/AIDS, pediatric cancer research, abortion, prescription drug prices, and preexisting conditions were among the health care highlights of President Donald Trump’s second State of the Union address Feb. 5.

Mr. Trump promised to push for funds to end HIV/AIDS and childhood cancer within in 10 years. “In recent years, we have made remarkable progress in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Scientific breakthroughs have brought a once-distant dream within reach,” he said to assembled members of Congress and leaders of the executive and judicial branches of government. “My budget will ask Democrats and Republicans to make the needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.”

Following the speech, Alex Azar, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, offered more details in a blog post on the agency’s website.

Funding for the initiative, dubbed “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America,” will have three components.

The first involves increasing investments in “geographic hotspots” though existing programs like the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and a new community health center–based program to provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to those at the highest risk of contracting the disease.

Second is the use of data to track where the disease is spreading most rapidly to help target prevention, care, and treatment at the local level. The third will provide funds for the creation of a local HIV HealthForce in these targeted areas to expand HIV prevention and treatment efforts.

A fact sheet on this initiative called for a 75% reduction in new cases of HIV infection in 5 years and at least a 90% reduction within 10 years.

President Trump called for similar efforts to address pediatric cancer.

“Tonight I am also asking you to join me in another fight that all American can get behind – the fight against childhood cancer,” he said, adding that his budget request will come with a line item of $500 million over 10 years to fund research. “Many childhood cancers have not seen new therapies in decades.”

President Trump also asked Congress to legislate a prohibition of late-term abortion.

“There could be no greater contrast to the beautiful image of a mother holding her infant child than the chilling displays our nation saw in recent days,” he said. “Lawmakers in New York cheered with delight upon the passage of legislation that would allow a baby to be ripped from the mother’s womb moments from birth. These are living, feeling beautiful babies who will never get the chance to share their love and their dreams with the world. ... Let us work together to build a culture that cherishes innocent life.”

He also touched on the recurring themes regarding lowering the cost of health care and prescription drugs, as well as protecting those with preexisting conditions, something he called a major priority.

“It’s unacceptable that Americans pay vastly more than people in other countries for the exact same drugs, often made in the exact same place. This is wrong. This is unfair and together we will stop it, and we will stop it fast,” he said.

He did not offer any specific policy recommendation on how to address prescription drug costs, other than a comment on the need for greater price transparency.

“I am asking Congress to pass legislation that finally takes on the problem of global freeloading and delivers fairness and price transparency for American patients,” he said.

“We should also require drug companies, insurance companies, and hospitals to disclose real prices to foster competition and bring costs way down.”

SOURCE: Trump D. State of the Union Address, Feb. 5, 2019.

HIV/AIDS, pediatric cancer research, abortion, prescription drug prices, and preexisting conditions were among the health care highlights of President Donald Trump’s second State of the Union address Feb. 5.

Mr. Trump promised to push for funds to end HIV/AIDS and childhood cancer within in 10 years. “In recent years, we have made remarkable progress in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Scientific breakthroughs have brought a once-distant dream within reach,” he said to assembled members of Congress and leaders of the executive and judicial branches of government. “My budget will ask Democrats and Republicans to make the needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.”

Following the speech, Alex Azar, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, offered more details in a blog post on the agency’s website.

Funding for the initiative, dubbed “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America,” will have three components.

The first involves increasing investments in “geographic hotspots” though existing programs like the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and a new community health center–based program to provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to those at the highest risk of contracting the disease.

Second is the use of data to track where the disease is spreading most rapidly to help target prevention, care, and treatment at the local level. The third will provide funds for the creation of a local HIV HealthForce in these targeted areas to expand HIV prevention and treatment efforts.

A fact sheet on this initiative called for a 75% reduction in new cases of HIV infection in 5 years and at least a 90% reduction within 10 years.

President Trump called for similar efforts to address pediatric cancer.

“Tonight I am also asking you to join me in another fight that all American can get behind – the fight against childhood cancer,” he said, adding that his budget request will come with a line item of $500 million over 10 years to fund research. “Many childhood cancers have not seen new therapies in decades.”

President Trump also asked Congress to legislate a prohibition of late-term abortion.

“There could be no greater contrast to the beautiful image of a mother holding her infant child than the chilling displays our nation saw in recent days,” he said. “Lawmakers in New York cheered with delight upon the passage of legislation that would allow a baby to be ripped from the mother’s womb moments from birth. These are living, feeling beautiful babies who will never get the chance to share their love and their dreams with the world. ... Let us work together to build a culture that cherishes innocent life.”

He also touched on the recurring themes regarding lowering the cost of health care and prescription drugs, as well as protecting those with preexisting conditions, something he called a major priority.

“It’s unacceptable that Americans pay vastly more than people in other countries for the exact same drugs, often made in the exact same place. This is wrong. This is unfair and together we will stop it, and we will stop it fast,” he said.

He did not offer any specific policy recommendation on how to address prescription drug costs, other than a comment on the need for greater price transparency.

“I am asking Congress to pass legislation that finally takes on the problem of global freeloading and delivers fairness and price transparency for American patients,” he said.

“We should also require drug companies, insurance companies, and hospitals to disclose real prices to foster competition and bring costs way down.”

SOURCE: Trump D. State of the Union Address, Feb. 5, 2019.

HIV/AIDS, pediatric cancer research, abortion, prescription drug prices, and preexisting conditions were among the health care highlights of President Donald Trump’s second State of the Union address Feb. 5.

Mr. Trump promised to push for funds to end HIV/AIDS and childhood cancer within in 10 years. “In recent years, we have made remarkable progress in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Scientific breakthroughs have brought a once-distant dream within reach,” he said to assembled members of Congress and leaders of the executive and judicial branches of government. “My budget will ask Democrats and Republicans to make the needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.”

Following the speech, Alex Azar, secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, offered more details in a blog post on the agency’s website.

Funding for the initiative, dubbed “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America,” will have three components.

The first involves increasing investments in “geographic hotspots” though existing programs like the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and a new community health center–based program to provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to those at the highest risk of contracting the disease.

Second is the use of data to track where the disease is spreading most rapidly to help target prevention, care, and treatment at the local level. The third will provide funds for the creation of a local HIV HealthForce in these targeted areas to expand HIV prevention and treatment efforts.

A fact sheet on this initiative called for a 75% reduction in new cases of HIV infection in 5 years and at least a 90% reduction within 10 years.

President Trump called for similar efforts to address pediatric cancer.

“Tonight I am also asking you to join me in another fight that all American can get behind – the fight against childhood cancer,” he said, adding that his budget request will come with a line item of $500 million over 10 years to fund research. “Many childhood cancers have not seen new therapies in decades.”

President Trump also asked Congress to legislate a prohibition of late-term abortion.

“There could be no greater contrast to the beautiful image of a mother holding her infant child than the chilling displays our nation saw in recent days,” he said. “Lawmakers in New York cheered with delight upon the passage of legislation that would allow a baby to be ripped from the mother’s womb moments from birth. These are living, feeling beautiful babies who will never get the chance to share their love and their dreams with the world. ... Let us work together to build a culture that cherishes innocent life.”

He also touched on the recurring themes regarding lowering the cost of health care and prescription drugs, as well as protecting those with preexisting conditions, something he called a major priority.

“It’s unacceptable that Americans pay vastly more than people in other countries for the exact same drugs, often made in the exact same place. This is wrong. This is unfair and together we will stop it, and we will stop it fast,” he said.

He did not offer any specific policy recommendation on how to address prescription drug costs, other than a comment on the need for greater price transparency.

“I am asking Congress to pass legislation that finally takes on the problem of global freeloading and delivers fairness and price transparency for American patients,” he said.

“We should also require drug companies, insurance companies, and hospitals to disclose real prices to foster competition and bring costs way down.”

SOURCE: Trump D. State of the Union Address, Feb. 5, 2019.

Key clinical point: President Trump calls for an end to HIV/AIDS and pediatric cancer in 10 years.

Major finding: His budget will request $500 million for cancer research and as yet undisclosed amount for HIV/AIDS research.

Study details: More specific details on the proposals will likely come when the president makes his budget submission to Congress in the coming weeks.

Disclosures: There are no disclosures.

Source: Trump D. State of the Union Address, Feb. 5, 2019.

Rise in HCV infection rates linked to OxyContin reformulation

Public health experts have attributed the alarming rise in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection rates in recent years to the opioid epidemic, and a new Rand study suggests that an effort to deter opioid abuse – namely the 2010 abuse-deterrent reformulation of OxyContin – is partly to blame.

Between 2004 and 2015, HCV infection rates in the United States nearly tripled, but a closer look showed that states with above-median rates of OxyContin misuse prior to the reformulation had a 222% increase in HCV rates, compared with a 75% increase in states with below-median OxyContin misuse, said David Powell, PhD, a senior economist at Rand in Arlington, Va., and his colleagues, Abby Alpert, PhD, and Rosalie L. Pacula, PhD. The report was published in Health Affairs.

The coauthors found that hepatitis C infection rates were not significantly different between the two groups of states before the reformulation (0.350 vs. 0.260). But after 2010, there were large and statistically significant differences in the rates (1.128 vs. 0.455; P less than 0.01), they wrote, noting that the above-median states experienced an additional 0.58 HCV infections per 100,000 population through 2015 relative to the below-median states).

HCV infection rates declined during the 1990s followed by a plateau beginning around 2003, then rose sharply beginning in 2010, coinciding with the introduction of the release of the abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin, which is one of the most commonly misused opioid analgesics, the investigators said, explaining that the reformulated version was harder to crush or dissolve, making it more difficult to inhale or inject.

“Prior studies have shown that, after OxyContin became more difficult to abuse, some nonmedical users of OxyContin switched to heroin (a pharmacologically similar opiate),” they noted.

This led to a decline of more than 40% in OxyContin misuse but also to a sharp increase in heroin overdoses after 2010.

The investigators assessed whether the related increase in heroin use might explain the increase in HCV infections, which can be transmitted through shared needle use.

Using a quasi-experimental difference-in-differences approach, they examined whether states with higher exposure to the reformulated OxyContin had faster growth of HCV infection rates after the reformulations, and as a falsification exercise, they also looked at whether the nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin predicted post-reformulation HCV infection rate increases.

HCV infection rates for each calendar year from 2004 to 2015 were assessed using confirmed case reports collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and nonmedical OxyContin use was measured using self-reported data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which is the largest U.S. survey on substance use disorder.

The two groups of states had similar demographic and economic conditions, except that the above-median misuse states had smaller populations and a larger proportion of white residents.

Of note, the patterns of HCV infection mirrored those of heroin overdoses. There was small relative increase in HCV infection rates in 2010 in the above-median OxyContin misuse states, and the gap between above- and below-median misuse states widened more rapidly from 2011 to 2013. “This striking inflection point in the trend of hepatitis C infections for high-misuse states after 2010 mimics the inflection in heroin overdoses that occurred as a result of the reformulation,” they said, noting that heroin morality per 100,000 population was nearly identical in the two groups of states in the pre-reformulation period (0.859 and 0.847).

The falsification exercise looking at nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin in the two groups of states showed that after 2010 groups’ rates of hepatitis C infections grew at virtually identical rates.

“Thus, the differential risk in hepatitis C infections was uniquely associated with OxyContin misuse, rather than prescription pain reliever misuse more generally,” they said. “This suggests that it was the OxyContin reformulation, not other policies broadly affecting opioids, that drove much of the differential growth.”

The investigators controlled for numerous other factors, including opioid policies that might have an impact on OxyContin and heroin use, prescription drug monitoring programs and pain clinic regulations, as well as the role of major pill-mill crackdowns in 2010 and 2011.

The findings represent a “substantial public health concern,” they said, explaining that, while “considerable policy attention is being given to managing the opioid epidemic ... a ‘silent epidemic’ of hepatitis C has emerged as a result of a transition in the mode of administration toward injection drug use.”

In 2017, the CDC reported on this link between the opioid epidemic and rising HCV infection rates, as well.

Dr. Powell and his colleagues wrote.

Their findings regarding the unintended consequences of the OxyContin reformulation suggest that caution is warranted with respect to future interventions that limit the supply of abusable prescription opioids, they said, adding that “such interventions must be paired with polices that alleviate the harms associated with switching to illicit drugs, such as improved access to substance use disorder treatment and increased efforts aimed at identifying and treating diseases associated with injection drug use.”

However, policy makers and medical professionals also must recognize that reducing opioid-related mortality and increasing access to drug treatment might not be sufficient to fully address all of the public health consequences associated with the opioid crisis. As additional reformulations of opioids are promoted and more policies seek to limit access to prescription opioids, “both the medical and the law enforcement communities must recognize the critical transition from prescription opioids to other drugs, particularly those that are injected, and be prepared to consider complementary strategies that can effectively reduce the additional harms from the particular mode of drug use,” they concluded.

The coauthors cited several limitations, including the possibility that true hepatitis C infection rates might have been underestimated in the study.

He and Dr. Pacula received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Powell also cited funding from the Rand Alumni Impact Award.

SOURCE: Powell D et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):287-94.

Increases have been seen not only in infectious diseases but also in cardiovascular diseases as intravenous opioid use has risen, Mark S. Gold, MD, said in an interview. “These emerging co-occurring diseases tend to lag behind drug deaths and other data,” he said.

The study by Powell et al. shows that drugs of abuse are dangerous, and that, with addictive use, we find consequences. “Each change appears to bring with it intended consequences we study, but over time, unintended consequences emerge,” he said. “It is important to remain vigilant.”

Dr. Gold is 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

Increases have been seen not only in infectious diseases but also in cardiovascular diseases as intravenous opioid use has risen, Mark S. Gold, MD, said in an interview. “These emerging co-occurring diseases tend to lag behind drug deaths and other data,” he said.

The study by Powell et al. shows that drugs of abuse are dangerous, and that, with addictive use, we find consequences. “Each change appears to bring with it intended consequences we study, but over time, unintended consequences emerge,” he said. “It is important to remain vigilant.”

Dr. Gold is 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

Increases have been seen not only in infectious diseases but also in cardiovascular diseases as intravenous opioid use has risen, Mark S. Gold, MD, said in an interview. “These emerging co-occurring diseases tend to lag behind drug deaths and other data,” he said.

The study by Powell et al. shows that drugs of abuse are dangerous, and that, with addictive use, we find consequences. “Each change appears to bring with it intended consequences we study, but over time, unintended consequences emerge,” he said. “It is important to remain vigilant.”

Dr. Gold is 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

Public health experts have attributed the alarming rise in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection rates in recent years to the opioid epidemic, and a new Rand study suggests that an effort to deter opioid abuse – namely the 2010 abuse-deterrent reformulation of OxyContin – is partly to blame.

Between 2004 and 2015, HCV infection rates in the United States nearly tripled, but a closer look showed that states with above-median rates of OxyContin misuse prior to the reformulation had a 222% increase in HCV rates, compared with a 75% increase in states with below-median OxyContin misuse, said David Powell, PhD, a senior economist at Rand in Arlington, Va., and his colleagues, Abby Alpert, PhD, and Rosalie L. Pacula, PhD. The report was published in Health Affairs.

The coauthors found that hepatitis C infection rates were not significantly different between the two groups of states before the reformulation (0.350 vs. 0.260). But after 2010, there were large and statistically significant differences in the rates (1.128 vs. 0.455; P less than 0.01), they wrote, noting that the above-median states experienced an additional 0.58 HCV infections per 100,000 population through 2015 relative to the below-median states).

HCV infection rates declined during the 1990s followed by a plateau beginning around 2003, then rose sharply beginning in 2010, coinciding with the introduction of the release of the abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin, which is one of the most commonly misused opioid analgesics, the investigators said, explaining that the reformulated version was harder to crush or dissolve, making it more difficult to inhale or inject.

“Prior studies have shown that, after OxyContin became more difficult to abuse, some nonmedical users of OxyContin switched to heroin (a pharmacologically similar opiate),” they noted.

This led to a decline of more than 40% in OxyContin misuse but also to a sharp increase in heroin overdoses after 2010.

The investigators assessed whether the related increase in heroin use might explain the increase in HCV infections, which can be transmitted through shared needle use.

Using a quasi-experimental difference-in-differences approach, they examined whether states with higher exposure to the reformulated OxyContin had faster growth of HCV infection rates after the reformulations, and as a falsification exercise, they also looked at whether the nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin predicted post-reformulation HCV infection rate increases.

HCV infection rates for each calendar year from 2004 to 2015 were assessed using confirmed case reports collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and nonmedical OxyContin use was measured using self-reported data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which is the largest U.S. survey on substance use disorder.

The two groups of states had similar demographic and economic conditions, except that the above-median misuse states had smaller populations and a larger proportion of white residents.

Of note, the patterns of HCV infection mirrored those of heroin overdoses. There was small relative increase in HCV infection rates in 2010 in the above-median OxyContin misuse states, and the gap between above- and below-median misuse states widened more rapidly from 2011 to 2013. “This striking inflection point in the trend of hepatitis C infections for high-misuse states after 2010 mimics the inflection in heroin overdoses that occurred as a result of the reformulation,” they said, noting that heroin morality per 100,000 population was nearly identical in the two groups of states in the pre-reformulation period (0.859 and 0.847).

The falsification exercise looking at nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin in the two groups of states showed that after 2010 groups’ rates of hepatitis C infections grew at virtually identical rates.

“Thus, the differential risk in hepatitis C infections was uniquely associated with OxyContin misuse, rather than prescription pain reliever misuse more generally,” they said. “This suggests that it was the OxyContin reformulation, not other policies broadly affecting opioids, that drove much of the differential growth.”

The investigators controlled for numerous other factors, including opioid policies that might have an impact on OxyContin and heroin use, prescription drug monitoring programs and pain clinic regulations, as well as the role of major pill-mill crackdowns in 2010 and 2011.

The findings represent a “substantial public health concern,” they said, explaining that, while “considerable policy attention is being given to managing the opioid epidemic ... a ‘silent epidemic’ of hepatitis C has emerged as a result of a transition in the mode of administration toward injection drug use.”

In 2017, the CDC reported on this link between the opioid epidemic and rising HCV infection rates, as well.

Dr. Powell and his colleagues wrote.

Their findings regarding the unintended consequences of the OxyContin reformulation suggest that caution is warranted with respect to future interventions that limit the supply of abusable prescription opioids, they said, adding that “such interventions must be paired with polices that alleviate the harms associated with switching to illicit drugs, such as improved access to substance use disorder treatment and increased efforts aimed at identifying and treating diseases associated with injection drug use.”

However, policy makers and medical professionals also must recognize that reducing opioid-related mortality and increasing access to drug treatment might not be sufficient to fully address all of the public health consequences associated with the opioid crisis. As additional reformulations of opioids are promoted and more policies seek to limit access to prescription opioids, “both the medical and the law enforcement communities must recognize the critical transition from prescription opioids to other drugs, particularly those that are injected, and be prepared to consider complementary strategies that can effectively reduce the additional harms from the particular mode of drug use,” they concluded.

The coauthors cited several limitations, including the possibility that true hepatitis C infection rates might have been underestimated in the study.

He and Dr. Pacula received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Powell also cited funding from the Rand Alumni Impact Award.

SOURCE: Powell D et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):287-94.

Public health experts have attributed the alarming rise in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection rates in recent years to the opioid epidemic, and a new Rand study suggests that an effort to deter opioid abuse – namely the 2010 abuse-deterrent reformulation of OxyContin – is partly to blame.

Between 2004 and 2015, HCV infection rates in the United States nearly tripled, but a closer look showed that states with above-median rates of OxyContin misuse prior to the reformulation had a 222% increase in HCV rates, compared with a 75% increase in states with below-median OxyContin misuse, said David Powell, PhD, a senior economist at Rand in Arlington, Va., and his colleagues, Abby Alpert, PhD, and Rosalie L. Pacula, PhD. The report was published in Health Affairs.

The coauthors found that hepatitis C infection rates were not significantly different between the two groups of states before the reformulation (0.350 vs. 0.260). But after 2010, there were large and statistically significant differences in the rates (1.128 vs. 0.455; P less than 0.01), they wrote, noting that the above-median states experienced an additional 0.58 HCV infections per 100,000 population through 2015 relative to the below-median states).

HCV infection rates declined during the 1990s followed by a plateau beginning around 2003, then rose sharply beginning in 2010, coinciding with the introduction of the release of the abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin, which is one of the most commonly misused opioid analgesics, the investigators said, explaining that the reformulated version was harder to crush or dissolve, making it more difficult to inhale or inject.

“Prior studies have shown that, after OxyContin became more difficult to abuse, some nonmedical users of OxyContin switched to heroin (a pharmacologically similar opiate),” they noted.

This led to a decline of more than 40% in OxyContin misuse but also to a sharp increase in heroin overdoses after 2010.

The investigators assessed whether the related increase in heroin use might explain the increase in HCV infections, which can be transmitted through shared needle use.

Using a quasi-experimental difference-in-differences approach, they examined whether states with higher exposure to the reformulated OxyContin had faster growth of HCV infection rates after the reformulations, and as a falsification exercise, they also looked at whether the nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin predicted post-reformulation HCV infection rate increases.

HCV infection rates for each calendar year from 2004 to 2015 were assessed using confirmed case reports collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and nonmedical OxyContin use was measured using self-reported data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which is the largest U.S. survey on substance use disorder.

The two groups of states had similar demographic and economic conditions, except that the above-median misuse states had smaller populations and a larger proportion of white residents.

Of note, the patterns of HCV infection mirrored those of heroin overdoses. There was small relative increase in HCV infection rates in 2010 in the above-median OxyContin misuse states, and the gap between above- and below-median misuse states widened more rapidly from 2011 to 2013. “This striking inflection point in the trend of hepatitis C infections for high-misuse states after 2010 mimics the inflection in heroin overdoses that occurred as a result of the reformulation,” they said, noting that heroin morality per 100,000 population was nearly identical in the two groups of states in the pre-reformulation period (0.859 and 0.847).

The falsification exercise looking at nonmedical use of pain relievers other than OxyContin in the two groups of states showed that after 2010 groups’ rates of hepatitis C infections grew at virtually identical rates.

“Thus, the differential risk in hepatitis C infections was uniquely associated with OxyContin misuse, rather than prescription pain reliever misuse more generally,” they said. “This suggests that it was the OxyContin reformulation, not other policies broadly affecting opioids, that drove much of the differential growth.”

The investigators controlled for numerous other factors, including opioid policies that might have an impact on OxyContin and heroin use, prescription drug monitoring programs and pain clinic regulations, as well as the role of major pill-mill crackdowns in 2010 and 2011.

The findings represent a “substantial public health concern,” they said, explaining that, while “considerable policy attention is being given to managing the opioid epidemic ... a ‘silent epidemic’ of hepatitis C has emerged as a result of a transition in the mode of administration toward injection drug use.”

In 2017, the CDC reported on this link between the opioid epidemic and rising HCV infection rates, as well.

Dr. Powell and his colleagues wrote.

Their findings regarding the unintended consequences of the OxyContin reformulation suggest that caution is warranted with respect to future interventions that limit the supply of abusable prescription opioids, they said, adding that “such interventions must be paired with polices that alleviate the harms associated with switching to illicit drugs, such as improved access to substance use disorder treatment and increased efforts aimed at identifying and treating diseases associated with injection drug use.”

However, policy makers and medical professionals also must recognize that reducing opioid-related mortality and increasing access to drug treatment might not be sufficient to fully address all of the public health consequences associated with the opioid crisis. As additional reformulations of opioids are promoted and more policies seek to limit access to prescription opioids, “both the medical and the law enforcement communities must recognize the critical transition from prescription opioids to other drugs, particularly those that are injected, and be prepared to consider complementary strategies that can effectively reduce the additional harms from the particular mode of drug use,” they concluded.

The coauthors cited several limitations, including the possibility that true hepatitis C infection rates might have been underestimated in the study.

He and Dr. Pacula received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Powell also cited funding from the Rand Alumni Impact Award.

SOURCE: Powell D et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):287-94.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Key clinical point: Physicians and others must be “prepared to consider complementary strategies that can effectively reduce the additional harms from the particular mode of drug use.”

Major finding: HCV rates increased 222% in states that had above-median OxyContin misuse rates, compared with an increase of 75% in states with below-median misuse.

Study details: A review of data from 2004 to 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Powell and Dr. Pacula received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Powell also cited funding from the Rand Alumni Impact Award.

Source: Powell D et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):287-94.

No increase in severe community-acquired pneumonia after PCV13

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Despite concern about the rise of nonvaccine serotypes following widespread PCV13 immunization, cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remain nearly as low as after initial implementation of the vaccine and severe cases have not risen at all.

This was the finding of a prospective time-series analysis study from eight French pediatric emergency departments between June 2009 and May 2017.

The 12,587 children with CAP enrolled in the study between June 2009 and May 2017 were all aged 15 years or younger and came from one of eight French pediatric EDs.

Pediatric pneumonia cases per 1,000 ED visits dropped 44% after PCV13 was implemented, a decrease from 6.3 to 3.5 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2011 to May 2014, with a slight but statistically significant increase to 3.8 cases of CAP per 1,000 pediatric visits from June 2014 to May 2017. However, there was no statistically significant increase in cases with pleural effusion, hospitalization, or high inflammatory biomarkers.

“These results contrast with the recent increase in frequency of invasive pneumococcal disease observed in several countries during the same period linked to serotype replacement beyond 5 years after PCV13 implementation,” reported Naïm Ouldali, MD, of the Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne in France, and associates. The report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“This difference in the trends suggests different consequences of serotype replacement on pneumococcal CAP vs invasive pneumococcal disease,” they wrote. “The recent slight increase in the number of all CAP cases and virus involvement may reflect changes in the epidemiology of other pathogens and/or serotype replacement with less pathogenic serotypes.”

This latter point arose from discovering no dominant serotype during the study period. Of the 11 serotypes not covered by PCV13, none appeared in more than four cases.

“The implementation of PCV13 has led to the quasi-disappearance of the more invasive serotypes and increase in others in nasopharyngeal flora, which greatly reduces the frequency of the more severe forms of CAP, but could also play a role in the slight increase in frequency of the more benign forms,” the authors reported.

Among the study’s limitations was lack of a control group, precluding the ability to attribute findings to any changes in case reporting. And “participating physicians were encouraged to not change their practice, including test use, and no other potential interfering intervention.”

Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant.

Dr Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pediatric community-acquired pneumonia cases dropped from 6.3 to 3.5 cases per 1,000 visits from 2010 to 2014 and increased to 3.8 cases per 1,000 visits in May 2017.

Study details: The findings are based on a prospective time series analysis of 12,587 pediatric pneumonia cases (under 15 years old) in eight French emergency departments from June 2009 to May 2017.

Disclosures: Funding sources for this study included the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Group of the French Pediatrics Society, Association Clinique et Thérapeutique Infantile du Val-de-Marne, the Foundation for Medical Research, and a Pfizer Investigator Initiated Research grant. Dr. Ouldali has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and many of the authors have financial ties and/or have received nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and/or Sanofi Pasteur.

Source: Ouldali N et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5273.

Flu activity & measles outbreaks: Where we stand, steps we can take

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Resources

Measles (Robeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/index.html. Updated January 28, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Influenza (Flu). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm. Updated January 25, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019.

Click for Credit: Missed HIV screening opps; aspirin & preeclampsia; more

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the February issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Short-term lung function better predicts mortality risk in SSc

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RrRuIY

Expires November 26, 2019

2. Healthier lifestyle in midlife women reduces subclinical carotid atherosclerosis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2TvDH5G

Expires November 28, 2019

3. Three commonly used quick cognitive assessments often yield flawed results

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G1qkHn

Expires November 28, 2019

4. Missed HIV screening opportunities found among subsequently infected youth

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HGa8Nm

Expires November 29, 2019

5. Aspirin appears underused to prevent preeclampsia in SLE patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2G0dU2v

Expires January 2, 2019

Flu activity ticks up for second week in a row

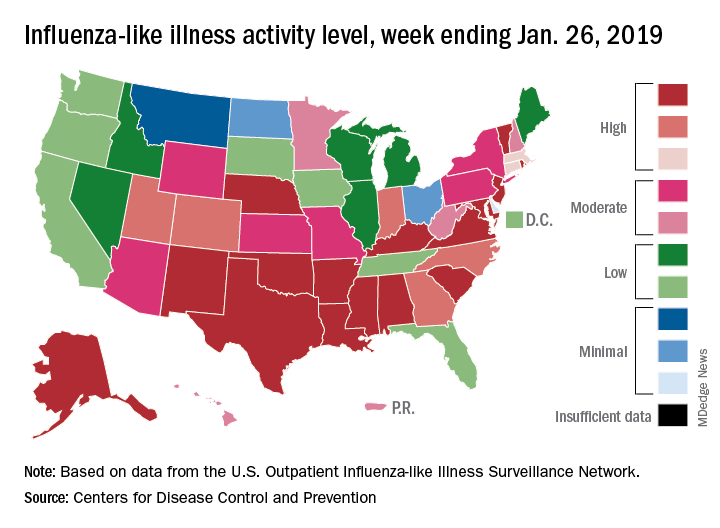

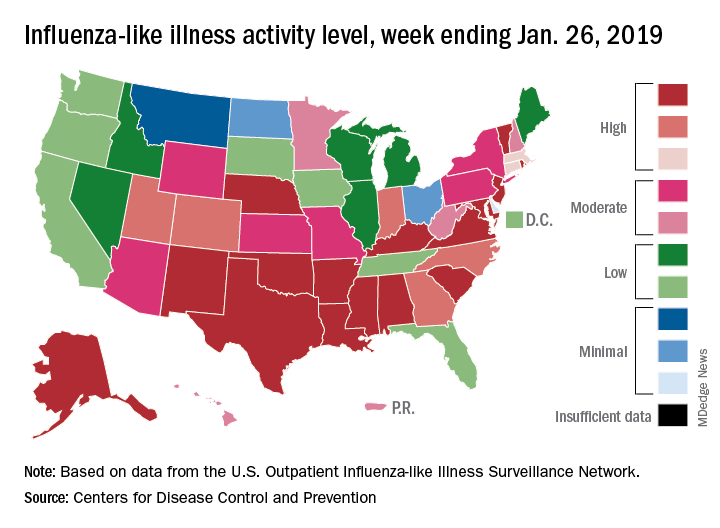

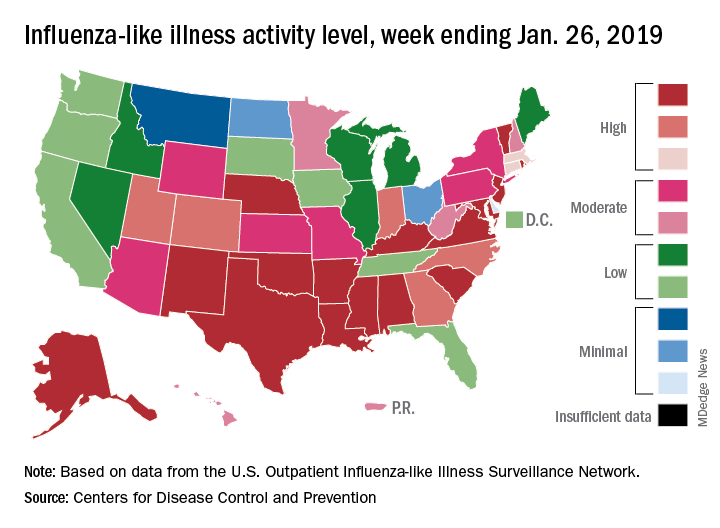

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Penicillin allergy

A 75-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and facial pain. He had an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks ago and has had persistent sinus drainage since. He has tried nasal irrigation and nasal steroids without improvement.

Over the past 5 days, he has had thicker postnasal drip, the development of facial pain, and today fevers as high as 102 degrees. He has a history of giant cell arteritis, for which he takes 30 mg of prednisone daily; coronary artery disease; and hypertension. He has a penicillin allergy (rash on chest, back, and arms 25 years ago). Exam reveals temperature of 101.5 and tenderness over left maxillary sinus.

What treatment do you recommend?

A. Amoxicillin/clavulanate.

B. Cefpodoxime.

C. Levofloxacin.

D. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

I think cefpodoxime is probably the best of these choices to treat sinusitis in this patient. Choosing amoxicillin /clavulanate is an option only if you could give the patient a test dose in a controlled setting. I think giving this patient levofloxacin poses greater risk than a penicillin rechallenge. This patient is elderly and on prednisone, both of which increase his risk of tendon rupture if given a quinolone. Also, the Food and Drug Administration released a warning recently regarding increased risk of aortic disease in patients with cardiovascular risk factors who receive fluoroquinolones.1

Merin Kuruvilla, MD, and colleagues described oral amoxicillin challenge for patients with a history of low-risk penicillin allergy (described as benign rash, benign somatic symptoms, or unknown history with penicillin exposure more than 12 months prior).2 The study was done in a single allergy practice where 38 of 50 patients with penicillin allergy histories qualified for the study. Of the 38 eligible patients, 20 consented to oral rechallenge in clinic, and none of them developed immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Melissa Iammatteo, MD, et al. studied 155 patients with a history of non–life-threatening penicillin reactions.3 Study participants received placebo followed by a two-step graded challenge to amoxicillin. No reaction occurred in 77% of patients, while 20% of patients had nonallergic reactions, which were equal between placebo and amoxicillin. Only 2.6 % had allergic reactions, all of which were classified as mild.

Reported penicillin allergy occurs in about 10% of community patients, but 90% of these patients can tolerate penicillins.4 Patients reporting a penicillin allergy have increased risk for drug resistance and prolonged hospital stays.5

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommended more widespread and routine performance of penicillin allergy testing in patients with a history of allergy to penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics.6 Patients who have penicillin allergy histories are more likely to receive drugs, such as clindamycin or a fluoroquinolone, that may carry much greater risks than a beta-lactam antibiotic. It also leads to more vancomycin use, which increases risk of vancomycin resistance.

Allergic reactions to cephalosporins are very infrequent in patients with a penicillin allergy. Eric Macy, MD, and colleagues studied all members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan who had received cephalosporins over a 2-year period.7 More than 275,000 courses were given to patients with penicillin allergy, with only about 1% having an allergic reaction and only three cases of anaphylaxis.

Pearl: Most patients with a history of penicillin allergy will tolerate penicillins and cephalosporins. Penicillin allergy testing should be done to assess if they have a penicillin allergy, and in low-risk patients (patients who do not recall the allergy or had a maculopapular rash), consideration for oral rechallenge in a controlled setting may be an option. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Food and Drug Administration. “FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients,” 2018 Dec 20.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Nov;121(5):627-8.

3. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):236-43.

4. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;37(4):643-62.

5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Mar;133(3):790-6.

6. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Mar - Apr;5(2):333-4.

7. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135(3):745-52.e5.

A 75-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and facial pain. He had an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks ago and has had persistent sinus drainage since. He has tried nasal irrigation and nasal steroids without improvement.

Over the past 5 days, he has had thicker postnasal drip, the development of facial pain, and today fevers as high as 102 degrees. He has a history of giant cell arteritis, for which he takes 30 mg of prednisone daily; coronary artery disease; and hypertension. He has a penicillin allergy (rash on chest, back, and arms 25 years ago). Exam reveals temperature of 101.5 and tenderness over left maxillary sinus.

What treatment do you recommend?

A. Amoxicillin/clavulanate.

B. Cefpodoxime.

C. Levofloxacin.

D. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

I think cefpodoxime is probably the best of these choices to treat sinusitis in this patient. Choosing amoxicillin /clavulanate is an option only if you could give the patient a test dose in a controlled setting. I think giving this patient levofloxacin poses greater risk than a penicillin rechallenge. This patient is elderly and on prednisone, both of which increase his risk of tendon rupture if given a quinolone. Also, the Food and Drug Administration released a warning recently regarding increased risk of aortic disease in patients with cardiovascular risk factors who receive fluoroquinolones.1

Merin Kuruvilla, MD, and colleagues described oral amoxicillin challenge for patients with a history of low-risk penicillin allergy (described as benign rash, benign somatic symptoms, or unknown history with penicillin exposure more than 12 months prior).2 The study was done in a single allergy practice where 38 of 50 patients with penicillin allergy histories qualified for the study. Of the 38 eligible patients, 20 consented to oral rechallenge in clinic, and none of them developed immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Melissa Iammatteo, MD, et al. studied 155 patients with a history of non–life-threatening penicillin reactions.3 Study participants received placebo followed by a two-step graded challenge to amoxicillin. No reaction occurred in 77% of patients, while 20% of patients had nonallergic reactions, which were equal between placebo and amoxicillin. Only 2.6 % had allergic reactions, all of which were classified as mild.

Reported penicillin allergy occurs in about 10% of community patients, but 90% of these patients can tolerate penicillins.4 Patients reporting a penicillin allergy have increased risk for drug resistance and prolonged hospital stays.5