User login

LAIV doesn’t up asthmatic children’s risk of lower respiratory events

, according to an analysis published in Vaccine.

The data corroborate other research indicating that live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is safe for children with asthma older than 2 years and suggest that the choice of vaccination in this population should be based on effectiveness, according to James D. Nordin, MD, MPH, a clinical researcher at HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Children and adolescents with asthma have an increased risk of morbidity if they contract influenza. They represent a disproportionate number of pediatric influenza hospitalizations and have been a focus of efforts to vaccinate children against influenza. Since 2003, the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and the LAIV have been available. Research indicates that LAIV is more effective than IIV at preventing culture-confirmed influenza in children. Two studies found an increased risk of wheezing in children who received LAIV, but other studies failed to replicate these findings.

A retrospective cohort study

Dr. Nordin and associates conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to investigate whether use of a guideline recommending LAIV for children aged 2 years and older with asthma increased the risk of lower respiratory events within 21 or 42 days of vaccination, compared with standard guidelines to administer IIV in children with asthma. The investigators drew data from two large medical groups with independent clinical leadership that serve demographically similar populations in Minnesota. One group (the LAIV group) switched its preference for all children from IIV to LAIV in 2010. The control group continued using IIV for children with asthma throughout the study period. Each group operates more than 20 clinics.

The investigators included children and adolescents aged 2-17 years who presented during one or more influenza season from 2007-2008 through 2014-2015. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of asthma or wheezing, received one or more influenza vaccines, had continuous insurance enrollment, and had at least one primary care or asthma related subspecialty encounter. They excluded patients with contraindications for LAIV (e.g., pregnancy, malignancy, and cystic fibrosis) and those with any hospitalization, ED visit, or outpatient encounter for a lower respiratory event in the 42 days before influenza vaccination.

Dr. Nordin and colleagues used a generalized estimating equation regression to estimate the ratio of rate ratios (RORs) comparing events before and after vaccination between the LAIV guideline and control groups. The researchers examined covariates such as age, gender, race or ethnicity, Medicaid insurance for at least 1 month in the previous year, neighborhood poverty, and neighborhood rates of asthma.

No increased risk

The investigators included 4,771 children and 7,851 child-influenza records in their analysis. During the period from 2007 to 2010, there were 2,215 child-influenza records from children and adolescents included from the LAIV group and 735 from the IIV guideline group. From 2010 to 2015, there were 3,767 child-influenza records in children and adolescents from the LAIV group and 1,134 from the IIV guideline group. After the LAIV group adopted the new guideline, the proportion of patients receiving LAIV increased from 23% to 68% in the LAIV group and from 7% to 11% in the control group.

About 88% of lower respiratory events included diagnoses for asthma exacerbations. When the investigators adjusted the data for age, asthma severity, asthma control, race or ethnicity, and Medicaid coverage, they found no increase in lower respiratory events associated with the LAIV guideline. The adjusted ROR was 0.74 for lower respiratory events within 21 days of vaccination and 0.77 for lower respiratory events within 42 days of vaccination. The results were similar when Dr. Nordin and colleagues stratified the data by age group, and including additional covariates did not alter the ROR estimates. In all, 21 hospitalizations occurred within 42 days of influenza vaccination, and the LAIV guideline did not increase the risk for hospitalization.

“Findings from this study are consistent with several recent observational studies of LAIV in children and adolescents with asthma,” said Dr. Nordin and colleagues.

One limitation of the current study was that the data were restricted to the information available in electronic health care or claims records. The researchers therefore were able to observe only medically attended lower respiratory events. Furthermore, the exclusion of asthma management encounters and the classification of asthma severity were based on diagnoses, visits, and medication orders and fills. The estimates thus are prone to misclassification, which may have biased the results. Finally, information on important variables such as daycare attendance, presence of school-age siblings, and exposure to secondhand smoke was not available.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Nordin JD et al. Vaccine. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.081.

, according to an analysis published in Vaccine.

The data corroborate other research indicating that live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is safe for children with asthma older than 2 years and suggest that the choice of vaccination in this population should be based on effectiveness, according to James D. Nordin, MD, MPH, a clinical researcher at HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Children and adolescents with asthma have an increased risk of morbidity if they contract influenza. They represent a disproportionate number of pediatric influenza hospitalizations and have been a focus of efforts to vaccinate children against influenza. Since 2003, the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and the LAIV have been available. Research indicates that LAIV is more effective than IIV at preventing culture-confirmed influenza in children. Two studies found an increased risk of wheezing in children who received LAIV, but other studies failed to replicate these findings.

A retrospective cohort study

Dr. Nordin and associates conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to investigate whether use of a guideline recommending LAIV for children aged 2 years and older with asthma increased the risk of lower respiratory events within 21 or 42 days of vaccination, compared with standard guidelines to administer IIV in children with asthma. The investigators drew data from two large medical groups with independent clinical leadership that serve demographically similar populations in Minnesota. One group (the LAIV group) switched its preference for all children from IIV to LAIV in 2010. The control group continued using IIV for children with asthma throughout the study period. Each group operates more than 20 clinics.

The investigators included children and adolescents aged 2-17 years who presented during one or more influenza season from 2007-2008 through 2014-2015. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of asthma or wheezing, received one or more influenza vaccines, had continuous insurance enrollment, and had at least one primary care or asthma related subspecialty encounter. They excluded patients with contraindications for LAIV (e.g., pregnancy, malignancy, and cystic fibrosis) and those with any hospitalization, ED visit, or outpatient encounter for a lower respiratory event in the 42 days before influenza vaccination.

Dr. Nordin and colleagues used a generalized estimating equation regression to estimate the ratio of rate ratios (RORs) comparing events before and after vaccination between the LAIV guideline and control groups. The researchers examined covariates such as age, gender, race or ethnicity, Medicaid insurance for at least 1 month in the previous year, neighborhood poverty, and neighborhood rates of asthma.

No increased risk

The investigators included 4,771 children and 7,851 child-influenza records in their analysis. During the period from 2007 to 2010, there were 2,215 child-influenza records from children and adolescents included from the LAIV group and 735 from the IIV guideline group. From 2010 to 2015, there were 3,767 child-influenza records in children and adolescents from the LAIV group and 1,134 from the IIV guideline group. After the LAIV group adopted the new guideline, the proportion of patients receiving LAIV increased from 23% to 68% in the LAIV group and from 7% to 11% in the control group.

About 88% of lower respiratory events included diagnoses for asthma exacerbations. When the investigators adjusted the data for age, asthma severity, asthma control, race or ethnicity, and Medicaid coverage, they found no increase in lower respiratory events associated with the LAIV guideline. The adjusted ROR was 0.74 for lower respiratory events within 21 days of vaccination and 0.77 for lower respiratory events within 42 days of vaccination. The results were similar when Dr. Nordin and colleagues stratified the data by age group, and including additional covariates did not alter the ROR estimates. In all, 21 hospitalizations occurred within 42 days of influenza vaccination, and the LAIV guideline did not increase the risk for hospitalization.

“Findings from this study are consistent with several recent observational studies of LAIV in children and adolescents with asthma,” said Dr. Nordin and colleagues.

One limitation of the current study was that the data were restricted to the information available in electronic health care or claims records. The researchers therefore were able to observe only medically attended lower respiratory events. Furthermore, the exclusion of asthma management encounters and the classification of asthma severity were based on diagnoses, visits, and medication orders and fills. The estimates thus are prone to misclassification, which may have biased the results. Finally, information on important variables such as daycare attendance, presence of school-age siblings, and exposure to secondhand smoke was not available.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Nordin JD et al. Vaccine. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.081.

, according to an analysis published in Vaccine.

The data corroborate other research indicating that live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is safe for children with asthma older than 2 years and suggest that the choice of vaccination in this population should be based on effectiveness, according to James D. Nordin, MD, MPH, a clinical researcher at HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, and colleagues.

Children and adolescents with asthma have an increased risk of morbidity if they contract influenza. They represent a disproportionate number of pediatric influenza hospitalizations and have been a focus of efforts to vaccinate children against influenza. Since 2003, the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and the LAIV have been available. Research indicates that LAIV is more effective than IIV at preventing culture-confirmed influenza in children. Two studies found an increased risk of wheezing in children who received LAIV, but other studies failed to replicate these findings.

A retrospective cohort study

Dr. Nordin and associates conducted a retrospective observational cohort study to investigate whether use of a guideline recommending LAIV for children aged 2 years and older with asthma increased the risk of lower respiratory events within 21 or 42 days of vaccination, compared with standard guidelines to administer IIV in children with asthma. The investigators drew data from two large medical groups with independent clinical leadership that serve demographically similar populations in Minnesota. One group (the LAIV group) switched its preference for all children from IIV to LAIV in 2010. The control group continued using IIV for children with asthma throughout the study period. Each group operates more than 20 clinics.

The investigators included children and adolescents aged 2-17 years who presented during one or more influenza season from 2007-2008 through 2014-2015. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of asthma or wheezing, received one or more influenza vaccines, had continuous insurance enrollment, and had at least one primary care or asthma related subspecialty encounter. They excluded patients with contraindications for LAIV (e.g., pregnancy, malignancy, and cystic fibrosis) and those with any hospitalization, ED visit, or outpatient encounter for a lower respiratory event in the 42 days before influenza vaccination.

Dr. Nordin and colleagues used a generalized estimating equation regression to estimate the ratio of rate ratios (RORs) comparing events before and after vaccination between the LAIV guideline and control groups. The researchers examined covariates such as age, gender, race or ethnicity, Medicaid insurance for at least 1 month in the previous year, neighborhood poverty, and neighborhood rates of asthma.

No increased risk

The investigators included 4,771 children and 7,851 child-influenza records in their analysis. During the period from 2007 to 2010, there were 2,215 child-influenza records from children and adolescents included from the LAIV group and 735 from the IIV guideline group. From 2010 to 2015, there were 3,767 child-influenza records in children and adolescents from the LAIV group and 1,134 from the IIV guideline group. After the LAIV group adopted the new guideline, the proportion of patients receiving LAIV increased from 23% to 68% in the LAIV group and from 7% to 11% in the control group.

About 88% of lower respiratory events included diagnoses for asthma exacerbations. When the investigators adjusted the data for age, asthma severity, asthma control, race or ethnicity, and Medicaid coverage, they found no increase in lower respiratory events associated with the LAIV guideline. The adjusted ROR was 0.74 for lower respiratory events within 21 days of vaccination and 0.77 for lower respiratory events within 42 days of vaccination. The results were similar when Dr. Nordin and colleagues stratified the data by age group, and including additional covariates did not alter the ROR estimates. In all, 21 hospitalizations occurred within 42 days of influenza vaccination, and the LAIV guideline did not increase the risk for hospitalization.

“Findings from this study are consistent with several recent observational studies of LAIV in children and adolescents with asthma,” said Dr. Nordin and colleagues.

One limitation of the current study was that the data were restricted to the information available in electronic health care or claims records. The researchers therefore were able to observe only medically attended lower respiratory events. Furthermore, the exclusion of asthma management encounters and the classification of asthma severity were based on diagnoses, visits, and medication orders and fills. The estimates thus are prone to misclassification, which may have biased the results. Finally, information on important variables such as daycare attendance, presence of school-age siblings, and exposure to secondhand smoke was not available.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Nordin JD et al. Vaccine. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.081.

FROM VACCINE

Uncomplicated appendicitis can be treated successfully with antibiotics

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: What is the late recurrence rate for patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics only?

Background: Short-term results support antibiotic treatment as alternative to surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. Long-term outcomes have not been assessed.

Study design: Observational follow-up.

Setting: Six hospitals in Finland.

Synopsis: The APPAC trial looked at 530 patients, aged 18-60 years, with CT confirmed acute uncomplicated appendicitis, who were randomized to receive either appendectomy or antibiotics. In this follow-up report, outcomes were assessed by telephone interviews conducted 3-5 years after the initial interventions. Overall, 100 of 256 (39.1%) of the antibiotic group ultimately underwent appendectomy within 5 years. Of those, 70/100 (70%) had their recurrence within 1 year of their initial presentation.

Bottom line: Patients with uncomplicated appendicitis treated with antibiotics have a 39% cumulative 5-year recurrence rate, with most recurrences occurring within the first year.

Citation: Salminem P et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259-65.

Dr. Asuen is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

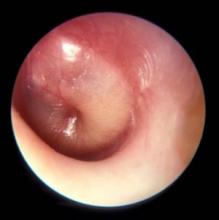

Can You Put Your Finger on the Diagnosis?

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

Flu vaccine succeeds in TNF inhibitor users

MADRID – Influenza vaccination is similarly effective for individuals taking a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor and healthy controls, but the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one case of influenza for patients taking a TNF inhibitor is much lower, according to data from a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one case of influenza among healthy control patients was 71, compared with an NNV of 10 for patients taking the TNF inhibitor adalimumab (Humira), reported Giovanni Adami, MD, and colleagues at the University of Verona (Italy).

While TNF inhibitors “are known to increase the risk of infection by suppressing the activity of the immune system,” it has not been clear whether the response to vaccination is impaired in patients treated with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami and colleagues reviewed data from 15,132 adult patients exposed to adalimumab in global rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials and 71,221 healthy controls from clinical trials of influenza vaccines. Overall, the rate of influenza infection was similarly reduced with vaccination in both groups. The rate in healthy individuals went from 2.3% for those unvaccinated to 0.9% for those vaccinated; for TNF inhibitor–treated patients, the rate was 14.4% for those unvaccinated versus 4.5% for those vaccinated.

“It is not surprising that the number needed to vaccinate is dramatically lower in patients treated with immunosuppressors, compared to healthy individuals,” Dr. Adami noted. “As a matter of fact, patients treated with such drugs are at higher risk of infections, namely they have a greater absolute risk of influenza. Nevertheless, [it] is quite surprising that the relative risk reduction is similar between TNF inhibitor–treated patients and healthy controls, meaning that the vaccination is efficacious in both the cohorts.”

The researchers also calculated the cost to prevent one case of influenza, using a cost of approximately 16.5 euro per vaccine. (Dr. Adami also cited an average U.S. cost of about $40/vaccine). Using this method, they estimated a cost for vaccination of 1,174 euro (roughly $1,340) to prevent one influenza infection in the general population, and a cost of about 165 euro (roughly $188) to vaccinate enough people treated with a TNF inhibitor to prevent one infection.

Dr. Adami advised clinicians to remember the low NNV for TNF inhibitor–treated patients with regard to influenza vaccination. “A direct disclosure of the NNV for these patients might help adherence to vaccinations,” he said.

Next steps for research should include extending the real-world effectiveness analysis to other medications and other diseases, such as zoster vaccination in patients treated with Janus kinase inhibitors, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Abiogen Pharma, Grünenthal, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

Mitchel L. Zoler contributed to this report.

SOURCE: Adami G et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):192-3. Abstract OP0230, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3088

MADRID – Influenza vaccination is similarly effective for individuals taking a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor and healthy controls, but the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one case of influenza for patients taking a TNF inhibitor is much lower, according to data from a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one case of influenza among healthy control patients was 71, compared with an NNV of 10 for patients taking the TNF inhibitor adalimumab (Humira), reported Giovanni Adami, MD, and colleagues at the University of Verona (Italy).

While TNF inhibitors “are known to increase the risk of infection by suppressing the activity of the immune system,” it has not been clear whether the response to vaccination is impaired in patients treated with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami and colleagues reviewed data from 15,132 adult patients exposed to adalimumab in global rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials and 71,221 healthy controls from clinical trials of influenza vaccines. Overall, the rate of influenza infection was similarly reduced with vaccination in both groups. The rate in healthy individuals went from 2.3% for those unvaccinated to 0.9% for those vaccinated; for TNF inhibitor–treated patients, the rate was 14.4% for those unvaccinated versus 4.5% for those vaccinated.

“It is not surprising that the number needed to vaccinate is dramatically lower in patients treated with immunosuppressors, compared to healthy individuals,” Dr. Adami noted. “As a matter of fact, patients treated with such drugs are at higher risk of infections, namely they have a greater absolute risk of influenza. Nevertheless, [it] is quite surprising that the relative risk reduction is similar between TNF inhibitor–treated patients and healthy controls, meaning that the vaccination is efficacious in both the cohorts.”

The researchers also calculated the cost to prevent one case of influenza, using a cost of approximately 16.5 euro per vaccine. (Dr. Adami also cited an average U.S. cost of about $40/vaccine). Using this method, they estimated a cost for vaccination of 1,174 euro (roughly $1,340) to prevent one influenza infection in the general population, and a cost of about 165 euro (roughly $188) to vaccinate enough people treated with a TNF inhibitor to prevent one infection.

Dr. Adami advised clinicians to remember the low NNV for TNF inhibitor–treated patients with regard to influenza vaccination. “A direct disclosure of the NNV for these patients might help adherence to vaccinations,” he said.

Next steps for research should include extending the real-world effectiveness analysis to other medications and other diseases, such as zoster vaccination in patients treated with Janus kinase inhibitors, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Abiogen Pharma, Grünenthal, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

Mitchel L. Zoler contributed to this report.

SOURCE: Adami G et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):192-3. Abstract OP0230, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3088

MADRID – Influenza vaccination is similarly effective for individuals taking a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor and healthy controls, but the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one case of influenza for patients taking a TNF inhibitor is much lower, according to data from a study presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

The number needed to vaccinate (NNV) to prevent one case of influenza among healthy control patients was 71, compared with an NNV of 10 for patients taking the TNF inhibitor adalimumab (Humira), reported Giovanni Adami, MD, and colleagues at the University of Verona (Italy).

While TNF inhibitors “are known to increase the risk of infection by suppressing the activity of the immune system,” it has not been clear whether the response to vaccination is impaired in patients treated with a TNF inhibitor, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami and colleagues reviewed data from 15,132 adult patients exposed to adalimumab in global rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials and 71,221 healthy controls from clinical trials of influenza vaccines. Overall, the rate of influenza infection was similarly reduced with vaccination in both groups. The rate in healthy individuals went from 2.3% for those unvaccinated to 0.9% for those vaccinated; for TNF inhibitor–treated patients, the rate was 14.4% for those unvaccinated versus 4.5% for those vaccinated.

“It is not surprising that the number needed to vaccinate is dramatically lower in patients treated with immunosuppressors, compared to healthy individuals,” Dr. Adami noted. “As a matter of fact, patients treated with such drugs are at higher risk of infections, namely they have a greater absolute risk of influenza. Nevertheless, [it] is quite surprising that the relative risk reduction is similar between TNF inhibitor–treated patients and healthy controls, meaning that the vaccination is efficacious in both the cohorts.”

The researchers also calculated the cost to prevent one case of influenza, using a cost of approximately 16.5 euro per vaccine. (Dr. Adami also cited an average U.S. cost of about $40/vaccine). Using this method, they estimated a cost for vaccination of 1,174 euro (roughly $1,340) to prevent one influenza infection in the general population, and a cost of about 165 euro (roughly $188) to vaccinate enough people treated with a TNF inhibitor to prevent one infection.

Dr. Adami advised clinicians to remember the low NNV for TNF inhibitor–treated patients with regard to influenza vaccination. “A direct disclosure of the NNV for these patients might help adherence to vaccinations,” he said.

Next steps for research should include extending the real-world effectiveness analysis to other medications and other diseases, such as zoster vaccination in patients treated with Janus kinase inhibitors, Dr. Adami said.

Dr. Adami had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with companies including Abiogen Pharma, Grünenthal, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

Mitchel L. Zoler contributed to this report.

SOURCE: Adami G et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):192-3. Abstract OP0230, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3088

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Legislative, educational interventions influenced vaccine status of California kindergartners

After California lawmakers implemented policies to limit and eventually eliminate nonmedical exemptions for childhood vaccinations, the proportion of kindergartners who were not up to date for recommended vaccinations fell from 10% in 2013 to 5% in 2017.

At the same time, the

The findings come from an observational study that used cross-sectional school-entry data from 2000 to 2017 to calculate the rates of kindergartners attending California schools who were not up to date on required vaccinations.

“Large-scale vaccination programs that included school-entry mandates have been essential to maintaining high levels of immunization coverage and low rates of vaccine-preventable diseases,” researchers led by S. Cassandra Pingali, MPH, MS, wrote in JAMA. “However, an increasing number of parents are not vaccinating their children over concerns about potential adverse effects. These parental actions threaten the herd immunity established by decades of high vaccine uptake and increase the potential for disease outbreaks.”

Ms. Pingali, of the department of epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues conducted an observational analysis of California kindergartners who were not up to date on one or more of the required vaccinations during the course of three interventions implemented in the state. The first was Assembly Bill 2109 (AB 2109), which was passed in 2014. It required parents to show proof they had discussed the risks of not vaccinating their children with a health care practitioner before they obtained a personal belief exemption. The second intervention was a campaign carried out in 2015 by the California Department of Public Health and local health departments, designed to educate school staff on the proper application of the conditional admission criteria, which allowed students additional time to catch up on vaccination. The third intervention was the implementation of Senate bill 277 (SB 277), which banned all personal belief exemptions.

Between 2000 and 2017, the researchers reported that the yearly mean kindergarten enrollment in California was 517,962 and the mean number of schools was 7,278. Over this time, the yearly rate of students without up-to-date vaccination status rose from 8% during 2000 to 10% during 2013, before decreasing to 5% during 2017. Ms. Pingali and associates also found that average percentage chance of any within-school contact for a student without up-to-date vaccination status with another student with the same status was 19% during 2000, and increased steadily to 26% during 2014, the first year of AB 2109. The values decreased to 3% (the first year of SB 277), before increasing slightly to 5% during 2017.

“Across the interventions, the percentage of kindergartners attending schools with an up-to-date vaccination status percentage that was greater than the herd immunity threshold also increased for various vaccine-preventable diseases,” the researchers wrote. “Overall, the results suggest that the risk of disease outbreak via potential contact among susceptible children decreased over the course of the interventions.”

The way Matthew M. Davis, MD and Seema K. Shah, JD, see it, the current outbreak of measles in the United States is rooted in the failure of parents to vaccinate their children against the disease based on their beliefs rather than medical contraindications.

“The public health implications of such decisions are amplified because parents who share belief systems about childhood vaccinations tend to congregate socially and residentially, thereby forming clusters of unvaccinated children who are at elevated health risks when exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases,” the authors wrote in an accompanying editorial.

While the study reported by Pingali et al. did not measure actual outbreaks of disease, “reductions in children’s risk of contracting measles are a promising outcome in California resulting from policy changes,” wrote Dr. Davis and Ms. Shah, both of Northwestern University, Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[1]:33-4). “Yet, because of the ease of domestic and international travel, the mobile nature of young families, and the inability of all states to implement this approach, changes made in each state for nonmedical exemptions may not ensure sufficiently high protection against measles for children across all jurisdictions in the United States. Although states have historically made their own decisions about vaccination exemptions linked to day care or school entry because states exercise primary authority over educational matters, childhood vaccination is a national matter in many respects.”

The best way to remedy the current system failure regarding measles vaccination, they continued, may be to adopt a unified national approach to prohibit nonmedical exemptions. They pointed to the fact that the United States previously achieved virtual eradication of measles as recently as 2000. “Following that achievement, state-level policy changes relaxed immunization requirements and set the stage for progressively larger outbreaks in the United States in recent years. Such system failures result when the products, processes, and people (including the public) that comprise systems do not function or behave in ways that protect health optimally.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported having received consulting fees from Merck and grants from Pfizer and Walgreens. Another reported receiving grants from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Protein Science, Dynavax, and MedImmune. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The editorialists reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pingali SC et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7924.

After California lawmakers implemented policies to limit and eventually eliminate nonmedical exemptions for childhood vaccinations, the proportion of kindergartners who were not up to date for recommended vaccinations fell from 10% in 2013 to 5% in 2017.

At the same time, the

The findings come from an observational study that used cross-sectional school-entry data from 2000 to 2017 to calculate the rates of kindergartners attending California schools who were not up to date on required vaccinations.

“Large-scale vaccination programs that included school-entry mandates have been essential to maintaining high levels of immunization coverage and low rates of vaccine-preventable diseases,” researchers led by S. Cassandra Pingali, MPH, MS, wrote in JAMA. “However, an increasing number of parents are not vaccinating their children over concerns about potential adverse effects. These parental actions threaten the herd immunity established by decades of high vaccine uptake and increase the potential for disease outbreaks.”

Ms. Pingali, of the department of epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues conducted an observational analysis of California kindergartners who were not up to date on one or more of the required vaccinations during the course of three interventions implemented in the state. The first was Assembly Bill 2109 (AB 2109), which was passed in 2014. It required parents to show proof they had discussed the risks of not vaccinating their children with a health care practitioner before they obtained a personal belief exemption. The second intervention was a campaign carried out in 2015 by the California Department of Public Health and local health departments, designed to educate school staff on the proper application of the conditional admission criteria, which allowed students additional time to catch up on vaccination. The third intervention was the implementation of Senate bill 277 (SB 277), which banned all personal belief exemptions.

Between 2000 and 2017, the researchers reported that the yearly mean kindergarten enrollment in California was 517,962 and the mean number of schools was 7,278. Over this time, the yearly rate of students without up-to-date vaccination status rose from 8% during 2000 to 10% during 2013, before decreasing to 5% during 2017. Ms. Pingali and associates also found that average percentage chance of any within-school contact for a student without up-to-date vaccination status with another student with the same status was 19% during 2000, and increased steadily to 26% during 2014, the first year of AB 2109. The values decreased to 3% (the first year of SB 277), before increasing slightly to 5% during 2017.

“Across the interventions, the percentage of kindergartners attending schools with an up-to-date vaccination status percentage that was greater than the herd immunity threshold also increased for various vaccine-preventable diseases,” the researchers wrote. “Overall, the results suggest that the risk of disease outbreak via potential contact among susceptible children decreased over the course of the interventions.”

The way Matthew M. Davis, MD and Seema K. Shah, JD, see it, the current outbreak of measles in the United States is rooted in the failure of parents to vaccinate their children against the disease based on their beliefs rather than medical contraindications.

“The public health implications of such decisions are amplified because parents who share belief systems about childhood vaccinations tend to congregate socially and residentially, thereby forming clusters of unvaccinated children who are at elevated health risks when exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases,” the authors wrote in an accompanying editorial.

While the study reported by Pingali et al. did not measure actual outbreaks of disease, “reductions in children’s risk of contracting measles are a promising outcome in California resulting from policy changes,” wrote Dr. Davis and Ms. Shah, both of Northwestern University, Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[1]:33-4). “Yet, because of the ease of domestic and international travel, the mobile nature of young families, and the inability of all states to implement this approach, changes made in each state for nonmedical exemptions may not ensure sufficiently high protection against measles for children across all jurisdictions in the United States. Although states have historically made their own decisions about vaccination exemptions linked to day care or school entry because states exercise primary authority over educational matters, childhood vaccination is a national matter in many respects.”

The best way to remedy the current system failure regarding measles vaccination, they continued, may be to adopt a unified national approach to prohibit nonmedical exemptions. They pointed to the fact that the United States previously achieved virtual eradication of measles as recently as 2000. “Following that achievement, state-level policy changes relaxed immunization requirements and set the stage for progressively larger outbreaks in the United States in recent years. Such system failures result when the products, processes, and people (including the public) that comprise systems do not function or behave in ways that protect health optimally.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported having received consulting fees from Merck and grants from Pfizer and Walgreens. Another reported receiving grants from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Protein Science, Dynavax, and MedImmune. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The editorialists reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pingali SC et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7924.

After California lawmakers implemented policies to limit and eventually eliminate nonmedical exemptions for childhood vaccinations, the proportion of kindergartners who were not up to date for recommended vaccinations fell from 10% in 2013 to 5% in 2017.

At the same time, the

The findings come from an observational study that used cross-sectional school-entry data from 2000 to 2017 to calculate the rates of kindergartners attending California schools who were not up to date on required vaccinations.

“Large-scale vaccination programs that included school-entry mandates have been essential to maintaining high levels of immunization coverage and low rates of vaccine-preventable diseases,” researchers led by S. Cassandra Pingali, MPH, MS, wrote in JAMA. “However, an increasing number of parents are not vaccinating their children over concerns about potential adverse effects. These parental actions threaten the herd immunity established by decades of high vaccine uptake and increase the potential for disease outbreaks.”

Ms. Pingali, of the department of epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues conducted an observational analysis of California kindergartners who were not up to date on one or more of the required vaccinations during the course of three interventions implemented in the state. The first was Assembly Bill 2109 (AB 2109), which was passed in 2014. It required parents to show proof they had discussed the risks of not vaccinating their children with a health care practitioner before they obtained a personal belief exemption. The second intervention was a campaign carried out in 2015 by the California Department of Public Health and local health departments, designed to educate school staff on the proper application of the conditional admission criteria, which allowed students additional time to catch up on vaccination. The third intervention was the implementation of Senate bill 277 (SB 277), which banned all personal belief exemptions.

Between 2000 and 2017, the researchers reported that the yearly mean kindergarten enrollment in California was 517,962 and the mean number of schools was 7,278. Over this time, the yearly rate of students without up-to-date vaccination status rose from 8% during 2000 to 10% during 2013, before decreasing to 5% during 2017. Ms. Pingali and associates also found that average percentage chance of any within-school contact for a student without up-to-date vaccination status with another student with the same status was 19% during 2000, and increased steadily to 26% during 2014, the first year of AB 2109. The values decreased to 3% (the first year of SB 277), before increasing slightly to 5% during 2017.

“Across the interventions, the percentage of kindergartners attending schools with an up-to-date vaccination status percentage that was greater than the herd immunity threshold also increased for various vaccine-preventable diseases,” the researchers wrote. “Overall, the results suggest that the risk of disease outbreak via potential contact among susceptible children decreased over the course of the interventions.”

The way Matthew M. Davis, MD and Seema K. Shah, JD, see it, the current outbreak of measles in the United States is rooted in the failure of parents to vaccinate their children against the disease based on their beliefs rather than medical contraindications.

“The public health implications of such decisions are amplified because parents who share belief systems about childhood vaccinations tend to congregate socially and residentially, thereby forming clusters of unvaccinated children who are at elevated health risks when exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases,” the authors wrote in an accompanying editorial.

While the study reported by Pingali et al. did not measure actual outbreaks of disease, “reductions in children’s risk of contracting measles are a promising outcome in California resulting from policy changes,” wrote Dr. Davis and Ms. Shah, both of Northwestern University, Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[1]:33-4). “Yet, because of the ease of domestic and international travel, the mobile nature of young families, and the inability of all states to implement this approach, changes made in each state for nonmedical exemptions may not ensure sufficiently high protection against measles for children across all jurisdictions in the United States. Although states have historically made their own decisions about vaccination exemptions linked to day care or school entry because states exercise primary authority over educational matters, childhood vaccination is a national matter in many respects.”

The best way to remedy the current system failure regarding measles vaccination, they continued, may be to adopt a unified national approach to prohibit nonmedical exemptions. They pointed to the fact that the United States previously achieved virtual eradication of measles as recently as 2000. “Following that achievement, state-level policy changes relaxed immunization requirements and set the stage for progressively larger outbreaks in the United States in recent years. Such system failures result when the products, processes, and people (including the public) that comprise systems do not function or behave in ways that protect health optimally.”

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported having received consulting fees from Merck and grants from Pfizer and Walgreens. Another reported receiving grants from Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Protein Science, Dynavax, and MedImmune. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The editorialists reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Pingali SC et al. JAMA. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.7924.

FROM JAMA

New research in otitis media

New research was presented at the International Society for Otitis Media meeting in June 2019, which I attended. I would like to share a selection of new findings from the many presentations.

Transtympanic antibiotic delivery

Topical therapy has been used to treat only otitis externa and acute otitis media (AOM) with ear discharge. Giving antibiotics through the tympanic membrane could mitigate many of the concerns about antibiotic use driving antibiotic resistance of bacteria among children. Up to now, using antibiotics in the ear canal to treat AOM has not been considered because the tympanic membrane is highly impermeable to the transtympanic diffusion of any drugs. However, in recent years, a number of different drug delivery systems have been developed, and in some cases, animal studies have shown that noninvasive transtympanic delivery is possible so that drugs can reach high concentrations in the middle ear without damage. Nanovesicles and nanoliposomes that contain antibiotics and are small enough to pass through the eardrum have been developed and tested in animal models; these show promise. Ototopical administration of a drug called vinpocetine that was repurposed has been tested in mice and shown to reduce inflammation and mucus production in the middle ear during otitis media.

Biofilms

Antibiotic treatment failure can occur in AOM for several reasons. The treatment of choice, amoxicillin, for example may fail to achieve an adequate concentration because of poor absorption in the gastrointestinal tract or poor penetration into the middle ear. Or, the antibiotic chosen may not be effective because of resistance of the strain causing the infection. Another explanation, especially in recurrent AOM and chronic AOM, could be the presence of biofilms. Biofilms are multicellular bacterial communities incorporated in a polymeric, plasticlike matrix in which pathogens are protected from antibiotic activity. The biofilm provides a physical barrier to antibiotic penetration, and bacteria can persist in the middle ear and periodically cause a new AOM. If AOM persists or becomes a more chronic otitis media with effusion, the “glue ear” causes an environment in the middle ear that is low in oxygen. A low-oxygen environment is favorable to biofilms. Also one might expect that middle ear pus would have a low pH, but actual measurements show the pH is highly alkaline. Species of Haemophilus influenzae have been identified as more virulent when in an alkaline pH or the alkaline pH makes the H. influenzae persist better in the middle ear, perhaps in a biofilm. To eliminate biofilms and improve antibiotic efficacy, a vaccine against a protein expressed by H. influenzae has been developed. Antibodies against this protein have been shown to disrupt and prevent the formation of biofilms in an animal model.

Probiotics

The normal bacteria that live in the nasopharynx of children with recurrent AOM is now known to differ from that of children who experience infrequent AOM or remain AOM-free throughout childhood. The use of oral pre- and probiotics for AOM prophylaxis remains debated because the results of studies are conflicting and frequently show no effect. So the idea of using prebiotics or probiotics to create a favorable “microbiome” of the nose is under investigation. Two species of bacteria that are gathering the most attention are Corynebacterium species (a few types in particular) and a bacteria called Dolosigranulum pigrum. Delivery of the commensal species would be as a nose spray.

Vaccines

The use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) has reduced the frequency of AOM caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCVs are not as effective against AOM as they are against invasive pneumococcal disease, but they still help a lot. However, because there are now at least 96 different serotypes of the pneumococcus based on different capsular types, we see a pattern of replacement of disease-causing strains by new strains within a few years of introduction of a new formulation. We started with 7 serotypes (Prevnar 7) in year 2000, and it was replaced by the current formulation with 13 serotypes (Prevnar 13) in 2010. Replacements have occurred again so vaccine companies are making new formulations for the future that include more serotypes, up to 20 serotypes. But, technically and feasibility-wise there is a limit to making such vaccines. A vaccine based on killed unencapsulated bacteria has been tested for safety and immunogenicity in young children. There is no test so far for prevention of AOM. Another type of vaccine based on proteins expressed by the pneumococcus that could be vaccine targets was tested in American Navajo children, and it failed to be as efficacious as hoped.

Biomarkers.

Due to recurrent AOM or persistent otitis media with effusion, about 15% of children in the United States receive tympanostomy tubes. Among those who receive tubes, about 20% go on to receive a second set of tubes, often with adenotonsillectomy. To find a biomarker that could identify children likely to require a second set of tubes, the fluid in the middle ear was tested when a first set of tubes were inserted. If bacteria were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or if a profile of specific inflammatory cytokines was measured, those results could be used to predict a high likelihood for a second set of tubes.

Overdiagnosis

Diagnosis of AOM is challenging in young children, in whom it most frequently occurs. The ear canal is typically about 3 mm wide, the child struggles during the examination, and diagnostic skills are not taught in training, resulting in a high overdiagnosis rate. I presented data that suggest too many children who are not truly otitis prone have been classified as otitis prone based on incorrect clinical diagnosis. My colleagues and I found that 30% of children reach the threshold of three episodes of AOM in 6 months or four within a year when diagnosed by community pediatricians, similar to many other studies. Validated otoscopists (trained by experts with diagnosis definitively proven as at least 85% accurate using tympanocentesis) classify 15% of children as otitis prone – half as many. If tympanocentesis is used to prove middle ear fluid has bacterial pathogens (about 95% yield a bacterial otopathogen using culture and PCR), then about 10% of children are classified as otitis prone – one-third as many. This suggests that children clinically diagnosed by community-based pediatricians are overdiagnosed with AOM, perhaps three times more often than true. And that leads to overuse of antibiotics and referrals for tympanostomy tube surgery more often than should occur. So we need to improve diagnostic methods beyond otoscopy. New types of imaging for the eardrum and middle ear using novel technologies are in early clinical trials.

Immunity

The notion that young children get AOM because of Eustachian tube dysfunction in their early years of life (horizontal anatomy) may be true, but there is more to the story. After 10 years of work, the scientists in my research group have shown that children in the first 3 years of life can have an immune system that is suppressed – it is poorly responsive to pathogens and routine pediatric vaccines. Many features resemble a neonatal immune system, beginning life with a suppressed immune system or being in cytokine storm from birth. We introduced the term “prolonged neonatal-like immune profile (PNIP)” to give a general description of the immune responses we have found in otitis-prone children. They outgrow this. So the immune maturation is delayed but not permanent. It is mostly resolved by age 3 years. We found problems in both innate and adaptive immunity. It may be that the main explanation for recurrent AOM in the first years of life is PNIP. Scientists from Australia also reported immunity problems in Aboriginal children and they are very otitis prone, often progressing to chronic suppurative otitis media. Animal model studies of AOM show inadequate innate and adaptive immunity importantly contribute to the infection as well.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Email him at [email protected].

New research was presented at the International Society for Otitis Media meeting in June 2019, which I attended. I would like to share a selection of new findings from the many presentations.

Transtympanic antibiotic delivery

Topical therapy has been used to treat only otitis externa and acute otitis media (AOM) with ear discharge. Giving antibiotics through the tympanic membrane could mitigate many of the concerns about antibiotic use driving antibiotic resistance of bacteria among children. Up to now, using antibiotics in the ear canal to treat AOM has not been considered because the tympanic membrane is highly impermeable to the transtympanic diffusion of any drugs. However, in recent years, a number of different drug delivery systems have been developed, and in some cases, animal studies have shown that noninvasive transtympanic delivery is possible so that drugs can reach high concentrations in the middle ear without damage. Nanovesicles and nanoliposomes that contain antibiotics and are small enough to pass through the eardrum have been developed and tested in animal models; these show promise. Ototopical administration of a drug called vinpocetine that was repurposed has been tested in mice and shown to reduce inflammation and mucus production in the middle ear during otitis media.

Biofilms

Antibiotic treatment failure can occur in AOM for several reasons. The treatment of choice, amoxicillin, for example may fail to achieve an adequate concentration because of poor absorption in the gastrointestinal tract or poor penetration into the middle ear. Or, the antibiotic chosen may not be effective because of resistance of the strain causing the infection. Another explanation, especially in recurrent AOM and chronic AOM, could be the presence of biofilms. Biofilms are multicellular bacterial communities incorporated in a polymeric, plasticlike matrix in which pathogens are protected from antibiotic activity. The biofilm provides a physical barrier to antibiotic penetration, and bacteria can persist in the middle ear and periodically cause a new AOM. If AOM persists or becomes a more chronic otitis media with effusion, the “glue ear” causes an environment in the middle ear that is low in oxygen. A low-oxygen environment is favorable to biofilms. Also one might expect that middle ear pus would have a low pH, but actual measurements show the pH is highly alkaline. Species of Haemophilus influenzae have been identified as more virulent when in an alkaline pH or the alkaline pH makes the H. influenzae persist better in the middle ear, perhaps in a biofilm. To eliminate biofilms and improve antibiotic efficacy, a vaccine against a protein expressed by H. influenzae has been developed. Antibodies against this protein have been shown to disrupt and prevent the formation of biofilms in an animal model.

Probiotics

The normal bacteria that live in the nasopharynx of children with recurrent AOM is now known to differ from that of children who experience infrequent AOM or remain AOM-free throughout childhood. The use of oral pre- and probiotics for AOM prophylaxis remains debated because the results of studies are conflicting and frequently show no effect. So the idea of using prebiotics or probiotics to create a favorable “microbiome” of the nose is under investigation. Two species of bacteria that are gathering the most attention are Corynebacterium species (a few types in particular) and a bacteria called Dolosigranulum pigrum. Delivery of the commensal species would be as a nose spray.

Vaccines

The use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) has reduced the frequency of AOM caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCVs are not as effective against AOM as they are against invasive pneumococcal disease, but they still help a lot. However, because there are now at least 96 different serotypes of the pneumococcus based on different capsular types, we see a pattern of replacement of disease-causing strains by new strains within a few years of introduction of a new formulation. We started with 7 serotypes (Prevnar 7) in year 2000, and it was replaced by the current formulation with 13 serotypes (Prevnar 13) in 2010. Replacements have occurred again so vaccine companies are making new formulations for the future that include more serotypes, up to 20 serotypes. But, technically and feasibility-wise there is a limit to making such vaccines. A vaccine based on killed unencapsulated bacteria has been tested for safety and immunogenicity in young children. There is no test so far for prevention of AOM. Another type of vaccine based on proteins expressed by the pneumococcus that could be vaccine targets was tested in American Navajo children, and it failed to be as efficacious as hoped.

Biomarkers.

Due to recurrent AOM or persistent otitis media with effusion, about 15% of children in the United States receive tympanostomy tubes. Among those who receive tubes, about 20% go on to receive a second set of tubes, often with adenotonsillectomy. To find a biomarker that could identify children likely to require a second set of tubes, the fluid in the middle ear was tested when a first set of tubes were inserted. If bacteria were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or if a profile of specific inflammatory cytokines was measured, those results could be used to predict a high likelihood for a second set of tubes.

Overdiagnosis

Diagnosis of AOM is challenging in young children, in whom it most frequently occurs. The ear canal is typically about 3 mm wide, the child struggles during the examination, and diagnostic skills are not taught in training, resulting in a high overdiagnosis rate. I presented data that suggest too many children who are not truly otitis prone have been classified as otitis prone based on incorrect clinical diagnosis. My colleagues and I found that 30% of children reach the threshold of three episodes of AOM in 6 months or four within a year when diagnosed by community pediatricians, similar to many other studies. Validated otoscopists (trained by experts with diagnosis definitively proven as at least 85% accurate using tympanocentesis) classify 15% of children as otitis prone – half as many. If tympanocentesis is used to prove middle ear fluid has bacterial pathogens (about 95% yield a bacterial otopathogen using culture and PCR), then about 10% of children are classified as otitis prone – one-third as many. This suggests that children clinically diagnosed by community-based pediatricians are overdiagnosed with AOM, perhaps three times more often than true. And that leads to overuse of antibiotics and referrals for tympanostomy tube surgery more often than should occur. So we need to improve diagnostic methods beyond otoscopy. New types of imaging for the eardrum and middle ear using novel technologies are in early clinical trials.

Immunity

The notion that young children get AOM because of Eustachian tube dysfunction in their early years of life (horizontal anatomy) may be true, but there is more to the story. After 10 years of work, the scientists in my research group have shown that children in the first 3 years of life can have an immune system that is suppressed – it is poorly responsive to pathogens and routine pediatric vaccines. Many features resemble a neonatal immune system, beginning life with a suppressed immune system or being in cytokine storm from birth. We introduced the term “prolonged neonatal-like immune profile (PNIP)” to give a general description of the immune responses we have found in otitis-prone children. They outgrow this. So the immune maturation is delayed but not permanent. It is mostly resolved by age 3 years. We found problems in both innate and adaptive immunity. It may be that the main explanation for recurrent AOM in the first years of life is PNIP. Scientists from Australia also reported immunity problems in Aboriginal children and they are very otitis prone, often progressing to chronic suppurative otitis media. Animal model studies of AOM show inadequate innate and adaptive immunity importantly contribute to the infection as well.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Email him at [email protected].

New research was presented at the International Society for Otitis Media meeting in June 2019, which I attended. I would like to share a selection of new findings from the many presentations.

Transtympanic antibiotic delivery

Topical therapy has been used to treat only otitis externa and acute otitis media (AOM) with ear discharge. Giving antibiotics through the tympanic membrane could mitigate many of the concerns about antibiotic use driving antibiotic resistance of bacteria among children. Up to now, using antibiotics in the ear canal to treat AOM has not been considered because the tympanic membrane is highly impermeable to the transtympanic diffusion of any drugs. However, in recent years, a number of different drug delivery systems have been developed, and in some cases, animal studies have shown that noninvasive transtympanic delivery is possible so that drugs can reach high concentrations in the middle ear without damage. Nanovesicles and nanoliposomes that contain antibiotics and are small enough to pass through the eardrum have been developed and tested in animal models; these show promise. Ototopical administration of a drug called vinpocetine that was repurposed has been tested in mice and shown to reduce inflammation and mucus production in the middle ear during otitis media.

Biofilms

Antibiotic treatment failure can occur in AOM for several reasons. The treatment of choice, amoxicillin, for example may fail to achieve an adequate concentration because of poor absorption in the gastrointestinal tract or poor penetration into the middle ear. Or, the antibiotic chosen may not be effective because of resistance of the strain causing the infection. Another explanation, especially in recurrent AOM and chronic AOM, could be the presence of biofilms. Biofilms are multicellular bacterial communities incorporated in a polymeric, plasticlike matrix in which pathogens are protected from antibiotic activity. The biofilm provides a physical barrier to antibiotic penetration, and bacteria can persist in the middle ear and periodically cause a new AOM. If AOM persists or becomes a more chronic otitis media with effusion, the “glue ear” causes an environment in the middle ear that is low in oxygen. A low-oxygen environment is favorable to biofilms. Also one might expect that middle ear pus would have a low pH, but actual measurements show the pH is highly alkaline. Species of Haemophilus influenzae have been identified as more virulent when in an alkaline pH or the alkaline pH makes the H. influenzae persist better in the middle ear, perhaps in a biofilm. To eliminate biofilms and improve antibiotic efficacy, a vaccine against a protein expressed by H. influenzae has been developed. Antibodies against this protein have been shown to disrupt and prevent the formation of biofilms in an animal model.

Probiotics

The normal bacteria that live in the nasopharynx of children with recurrent AOM is now known to differ from that of children who experience infrequent AOM or remain AOM-free throughout childhood. The use of oral pre- and probiotics for AOM prophylaxis remains debated because the results of studies are conflicting and frequently show no effect. So the idea of using prebiotics or probiotics to create a favorable “microbiome” of the nose is under investigation. Two species of bacteria that are gathering the most attention are Corynebacterium species (a few types in particular) and a bacteria called Dolosigranulum pigrum. Delivery of the commensal species would be as a nose spray.

Vaccines

The use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) has reduced the frequency of AOM caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCVs are not as effective against AOM as they are against invasive pneumococcal disease, but they still help a lot. However, because there are now at least 96 different serotypes of the pneumococcus based on different capsular types, we see a pattern of replacement of disease-causing strains by new strains within a few years of introduction of a new formulation. We started with 7 serotypes (Prevnar 7) in year 2000, and it was replaced by the current formulation with 13 serotypes (Prevnar 13) in 2010. Replacements have occurred again so vaccine companies are making new formulations for the future that include more serotypes, up to 20 serotypes. But, technically and feasibility-wise there is a limit to making such vaccines. A vaccine based on killed unencapsulated bacteria has been tested for safety and immunogenicity in young children. There is no test so far for prevention of AOM. Another type of vaccine based on proteins expressed by the pneumococcus that could be vaccine targets was tested in American Navajo children, and it failed to be as efficacious as hoped.

Biomarkers.

Due to recurrent AOM or persistent otitis media with effusion, about 15% of children in the United States receive tympanostomy tubes. Among those who receive tubes, about 20% go on to receive a second set of tubes, often with adenotonsillectomy. To find a biomarker that could identify children likely to require a second set of tubes, the fluid in the middle ear was tested when a first set of tubes were inserted. If bacteria were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or if a profile of specific inflammatory cytokines was measured, those results could be used to predict a high likelihood for a second set of tubes.

Overdiagnosis