User login

Short-term parenteral antibiotics effective for bacteremic UTI in young infants

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Urinary tract infection (UTI) recurrence and hospital reutilization was similar in infants with bacteremic UTIs, regardless of parenteral antibiotic treatment duration of 7 days or less or greater than 7 days prior to oral antibiotics.

Major finding: The adjusted risk difference for both infection recurrence and hospital reutilization was 3% and was nonsignificant in both cases.

Study details: A group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to an ED with a bacteremic UTI.

Disclosures: The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The funding of the study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant.

Source: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844.

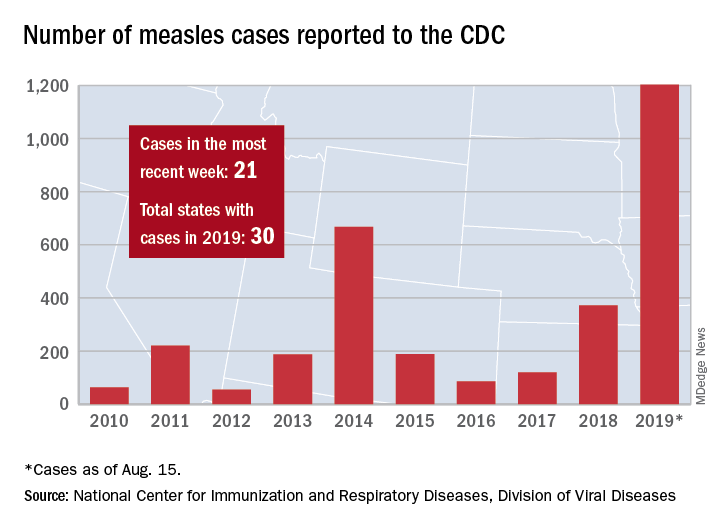

New measles outbreak reported in western N.Y.

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

Statins hamper hepatocellular carcinoma in viral hepatitis patients

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Lipophilic statin therapy significantly reduced the incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with viral hepatitis, based on data from 16,668 patients.

The mortality rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States and Europe have been on the rise for decades, and the risk may persist in severe cases despite the use of hepatitis B virus suppression or hepatitis C virus eradication, wrote Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that statins might reduce HCC risk in viral hepatitis patients, but evidence supporting one type of statin over another for HCC prevention is limited, they said.

In a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data from a national registry of hepatitis patients in Sweden to assess the effect of lipophilic or hydrophilic statin use on HCC incidence and mortality.

They found a significant reduction in 10-year HCC risk for lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (8.1% vs. 3.3%. However, the difference was not significant for hydrophilic statin users vs. nonusers (8.0% vs. 6.8%). The effect of lipophilic statin use was dose dependent; the largest effect on reduction in HCC risk occurred with 600 or more lipophilic statin cumulative daily doses in users, compared with nonusers (8.4% vs. 2.5%).

The study population included 6,554 lipophilic statin users and 1,780 hydrophilic statin users, matched with 8,334 nonusers. Patient demographics were similar between both types of statin user and nonuser groups.

In addition, 10-year mortality was significantly lower for lipophilic statin users compared with nonusers (15.2% vs. 7.3%) and also for hydrophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (16.0% vs. 11.5%).

In a small number of patients with liver disease (462), liver-specific mortality was significantly reduced in lipophilic statin users, compared with nonusers (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.76 vs. 0.98).

“Of note, our findings were robust across several sensitivity analyses and were similar in all predefined subgroups, including among men and women and persons with and without cirrhosis or antiviral therapy use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential confounding from variables such as smoking, hepatitis B viral DNA, hepatitis C virus eradication, stage of fibrosis, and HCC screening, as well as a lack of laboratory data to assess cholesterol levels’ impact on statin use, the researchers said. In addition, the study did not compare lipophilic and hydrophilic statins.

However, the results suggest potential distinct benefits of lipophilic statins to reduce HCC risk and support the need for further research, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The study was supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, Nyckelfonden, Region Orebro (Sweden) County, and the Karolinska Institutet.

SOURCE: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Use of lipophilic statins significantly reduced incidence and mortality of hepatocellular cancer in adults with viral hepatitis.

Major finding: The 10-year risk of HCC was 8.1% among patients taking lipophilic statins, compared with 3.3% among those not on statins.

Study details: The data come from a population-based cohort study of 16,668 adult with viral hepatitis from a national registry in Sweden.

Disclosures: Dr. Simon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but disclosed support from a North American Training Grant from the American College of Gastroenterology. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with multiple companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and MSD.

Source: Simon TG et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753.

Differential monocytic HLA-DR expression prognostically useful in PICU

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – During their first 4 days in the pediatric ICU, critically ill children have significantly reduced human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–DR expression within all three major subsets of monocytes. The reductions are seen regardless of whether the children were admitted for sepsis, trauma, or after surgery, Navin Boeddha, MD, PhD, reported in his PIDJ Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The PIDJ Award is given annually by the editors of the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal in recognition of what they deem the most important study published in the journal during the prior year. This one stood out because it identified promising potential laboratory markers that have been sought as a prerequisite to developing immunostimulatory therapies aimed at improving outcomes in severely immunosuppressed children.

Researchers are particularly eager to explore this investigative treatment strategy because the mortality and long-term morbidity of pediatric sepsis, in particular, remain unacceptably high. The hope now is that HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets will be helpful in directing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma, and other immunostimulatory therapies to the pediatric ICU patients with the most favorable benefit/risk ratio, according to Dr. Boeddha of Sophia Children’s Hospital and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He reported on 37 critically ill children admitted to a pediatric ICU – 12 for sepsis, 11 post surgery, 10 for trauma, and 4 for other reasons – as well as 37 healthy controls. HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets was measured by flow cytometry upon admission and again on each of the following 3 days.

The impetus for this study is that severe infection, major surgery, and severe trauma are often associated with immunosuppression. And while prior work in septic adults has concluded that decreased monocytic HLA-DR expression is a marker for immunosuppression – and that the lower the level of such expression, the greater the risk of nosocomial infection and death – this phenomenon hasn’t been well studied in critically ill children, he explained.

Dr. Boeddha and coinvestigators found that monocytic HLA-DR expression, which plays a major role in presenting antigens to T cells, decreased over time during the critically ill children’s first 4 days in the pediatric ICU. Moreover, it was lower than in controls at all four time points. This was true both for the percentage of HLA-DR–expressing monocytes of all subsets, as well as for HLA-DR mean fluorescence intensity.

In the critically ill study population as a whole, the percentage of classical monocytes – that is, CD14++ CD16– monocytes – was significantly greater at admission than in healthy controls by margins of 95% and 87%, while the percentage of nonclassical CD14+/-CD16++ monocytes was markedly lower at 2% than the 9% figure in controls.

The biggest discrepancy in monocyte subset distribution was seen in patients admitted for sepsis. Their percentage of classical monocytes was lower than in controls by a margin of 82% versus 87%; however, their proportion of intermediate monocytes (CD14++ CD16+) upon admission was twice that of controls, and it climbed further to 14% on day 2.

Among the key findings in the Rotterdam study: 13 of 37 critically ill patients experienced at least one nosocomial infection while in the pediatric ICU. Their day 2 percentage of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes was 42%, strikingly lower than the 78% figure in patients who didn’t develop an infection. Also, the 6 patients who died had only a 33% rate of HLA-DR–expressing classical monocytes on day 3 after pediatric ICU admission versus a 63% rate in survivors of their critical illness.

Thus, low HLA-DR expression on classical monocytes early during the course of a pediatric ICU stay may be the sought-after biomarker that identifies a particularly high-risk subgroup of critically ill children in whom immunostimulatory therapies should be studied. However, future confirmatory studies should monitor monocytic HLA-DR expression in a larger critically ill patient population for a longer period in order to establish the time to recovery of low expression and its impact on long-term complications, the physician said.

Dr. Boeddha reported having no financial conflicts regarding the award-winning study, supported by the European Union and Erasmus University.

SOURCE: Boeddha NP et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Oct;37(10):1034-40.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Presepsin can rule out invasive bacterial infection in infants

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A point-of-care presepsin measurement in the emergency department displayed powerful accuracy for early rule-out of invasive bacterial infection in infants less than 3 months old presenting with fever without a source, based on results of a phase 3 multicenter Italian study.

“P-SEP [presepsin] is a promising new biomarker. P-SEP accuracy for invasive bacterial infection is comparable to procalcitonin, even though P-SEP, like procalcitonin, is probably not accurate enough to be used as a stand-alone marker to rule-in an invasive bacterial infection,” Luca Pierantoni, MD, said in presenting the preliminary study results at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The presepsin test is a rapid point-of-care test well-suited for the ED setting, with a cost equal to that of point-of-care procalcitonin.

Presepsin is a form of soluble CD14 that is released from the surface of macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils when these immune cells are stimulated by pathogens. “We think it may be a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker of sepsis in adults and neonates,” explained Dr. Pierantoni of the University of Bologna, Italy.

Indeed, studies in adults suggest presepsin has better sensitivity and specificity than other biomarkers for early diagnosis of sepsis, and that it provides useful information on severity and prognosis as well. But, Dr. Pierantoni and his coworkers wondered, how does it perform in febrile young infants?

The Italian study was designed to address an unmet need: Fever accounts for about one-third of ED visits in infants up to age 3 months, 20% of whom are initially categorized as having fever without source. Yet ultimately 10%-20% of those youngsters having fever without source are found to have an invasive bacterial infection – that is, sepsis or meningitis – or a severe bacterial infection such as pneumonia, a urinary tract infection, or an infected umbilical cord. The sooner these infants can be identified and appropriately treated, the better.

The study enrolled 284 children less than 3 months old who had fever without cause of a mean 10.5 hours duration and presented to the emergency departments of six Italian medical centers. Children were eligible for the study regardless of whether they appeared toxic or well. Presepsin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein levels were immediately measured in all participants. Ultimately, 5.6% of subjects were diagnosed with an invasive bacterial infection, and another 21.2% had a severe bacterial infection.

Using a cutoff value of 449 pg/mL, P-SEP had good diagnostic accuracy for invasive bacterial infection, with an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 0.81, essentially the same as the 0.82 value for procalcitonin. P-SEP had a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 75%, respectively, placing it in the same ballpark as the 82% and 86% values for procalcitonin. The strong point for P-SEP was its 99% negative predictive value, as compared to 91% for procalcitonin. The positive predictive values were 17% for P-SEP and 20% for procalcitonin.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Pierantoni speculated that the best use for P-SEP in the setting of fever of unknown origin may be in combination with procalcitonin rather than as a replacement for it. The research team is now in the process of analyzing their study data to see if that is indeed the case.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A point-of-care presepsin measurement in the emergency department displayed powerful accuracy for early rule-out of invasive bacterial infection in infants less than 3 months old presenting with fever without a source, based on results of a phase 3 multicenter Italian study.

“P-SEP [presepsin] is a promising new biomarker. P-SEP accuracy for invasive bacterial infection is comparable to procalcitonin, even though P-SEP, like procalcitonin, is probably not accurate enough to be used as a stand-alone marker to rule-in an invasive bacterial infection,” Luca Pierantoni, MD, said in presenting the preliminary study results at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The presepsin test is a rapid point-of-care test well-suited for the ED setting, with a cost equal to that of point-of-care procalcitonin.

Presepsin is a form of soluble CD14 that is released from the surface of macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils when these immune cells are stimulated by pathogens. “We think it may be a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker of sepsis in adults and neonates,” explained Dr. Pierantoni of the University of Bologna, Italy.

Indeed, studies in adults suggest presepsin has better sensitivity and specificity than other biomarkers for early diagnosis of sepsis, and that it provides useful information on severity and prognosis as well. But, Dr. Pierantoni and his coworkers wondered, how does it perform in febrile young infants?

The Italian study was designed to address an unmet need: Fever accounts for about one-third of ED visits in infants up to age 3 months, 20% of whom are initially categorized as having fever without source. Yet ultimately 10%-20% of those youngsters having fever without source are found to have an invasive bacterial infection – that is, sepsis or meningitis – or a severe bacterial infection such as pneumonia, a urinary tract infection, or an infected umbilical cord. The sooner these infants can be identified and appropriately treated, the better.

The study enrolled 284 children less than 3 months old who had fever without cause of a mean 10.5 hours duration and presented to the emergency departments of six Italian medical centers. Children were eligible for the study regardless of whether they appeared toxic or well. Presepsin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein levels were immediately measured in all participants. Ultimately, 5.6% of subjects were diagnosed with an invasive bacterial infection, and another 21.2% had a severe bacterial infection.

Using a cutoff value of 449 pg/mL, P-SEP had good diagnostic accuracy for invasive bacterial infection, with an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 0.81, essentially the same as the 0.82 value for procalcitonin. P-SEP had a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 75%, respectively, placing it in the same ballpark as the 82% and 86% values for procalcitonin. The strong point for P-SEP was its 99% negative predictive value, as compared to 91% for procalcitonin. The positive predictive values were 17% for P-SEP and 20% for procalcitonin.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Pierantoni speculated that the best use for P-SEP in the setting of fever of unknown origin may be in combination with procalcitonin rather than as a replacement for it. The research team is now in the process of analyzing their study data to see if that is indeed the case.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A point-of-care presepsin measurement in the emergency department displayed powerful accuracy for early rule-out of invasive bacterial infection in infants less than 3 months old presenting with fever without a source, based on results of a phase 3 multicenter Italian study.

“P-SEP [presepsin] is a promising new biomarker. P-SEP accuracy for invasive bacterial infection is comparable to procalcitonin, even though P-SEP, like procalcitonin, is probably not accurate enough to be used as a stand-alone marker to rule-in an invasive bacterial infection,” Luca Pierantoni, MD, said in presenting the preliminary study results at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The presepsin test is a rapid point-of-care test well-suited for the ED setting, with a cost equal to that of point-of-care procalcitonin.

Presepsin is a form of soluble CD14 that is released from the surface of macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils when these immune cells are stimulated by pathogens. “We think it may be a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker of sepsis in adults and neonates,” explained Dr. Pierantoni of the University of Bologna, Italy.

Indeed, studies in adults suggest presepsin has better sensitivity and specificity than other biomarkers for early diagnosis of sepsis, and that it provides useful information on severity and prognosis as well. But, Dr. Pierantoni and his coworkers wondered, how does it perform in febrile young infants?

The Italian study was designed to address an unmet need: Fever accounts for about one-third of ED visits in infants up to age 3 months, 20% of whom are initially categorized as having fever without source. Yet ultimately 10%-20% of those youngsters having fever without source are found to have an invasive bacterial infection – that is, sepsis or meningitis – or a severe bacterial infection such as pneumonia, a urinary tract infection, or an infected umbilical cord. The sooner these infants can be identified and appropriately treated, the better.

The study enrolled 284 children less than 3 months old who had fever without cause of a mean 10.5 hours duration and presented to the emergency departments of six Italian medical centers. Children were eligible for the study regardless of whether they appeared toxic or well. Presepsin, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein levels were immediately measured in all participants. Ultimately, 5.6% of subjects were diagnosed with an invasive bacterial infection, and another 21.2% had a severe bacterial infection.

Using a cutoff value of 449 pg/mL, P-SEP had good diagnostic accuracy for invasive bacterial infection, with an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 0.81, essentially the same as the 0.82 value for procalcitonin. P-SEP had a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 75%, respectively, placing it in the same ballpark as the 82% and 86% values for procalcitonin. The strong point for P-SEP was its 99% negative predictive value, as compared to 91% for procalcitonin. The positive predictive values were 17% for P-SEP and 20% for procalcitonin.

In response to an audience question, Dr. Pierantoni speculated that the best use for P-SEP in the setting of fever of unknown origin may be in combination with procalcitonin rather than as a replacement for it. The research team is now in the process of analyzing their study data to see if that is indeed the case.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Key clinical point: A rapid point-of-care measurement of presepsin in the ED can rule out invasive bacterial infection with 99% accuracy in young infants with fever of unknown source.

Major finding: The negative predictive value of a presepsin level below the cutoff value of 449 pg/mL was 99%.

Study details: This was a multicenter Italian observational study of 284 infants less than 3 months old who presented to emergency departments with fever without source.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

Is your office ready for a case of measles?

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

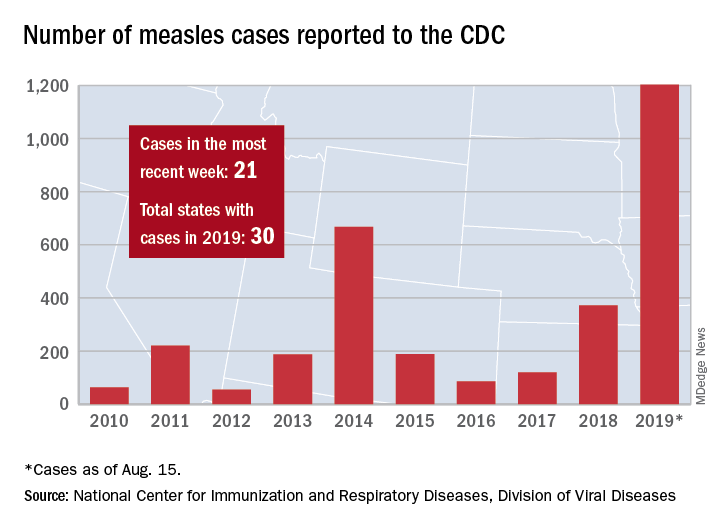

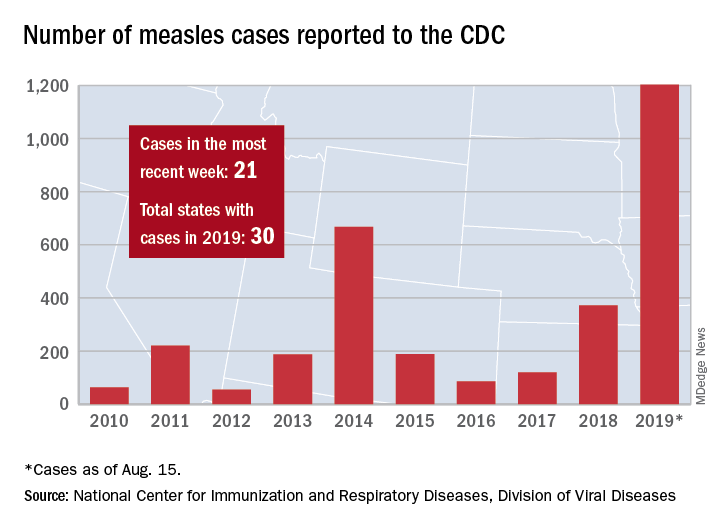

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

‘Substantial burden’ of enterovirus meningitis in young infants

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.