User login

Polypharmacy in an Aging HIV Population

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2019

ARV Therapy: Current Issues and Controversies

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2019

Asymptomatic hypopigmented macules and patches

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, also known as Pityrosporum orbiculare or P. ovale. In its hyphal form, it produces skin lesions that appear as scaly, round or oval, hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or pink macules or patches. Lesions are asymptomatic. The condition is more commonly seen in warm climates or during the summer months. Malassezia requires an oily environment for growth. Typically, TV appears in sebum-producing areas on the trunk. However, other sites may be affected such as the scalp, groin, and flexural areas. Infants may have facial lesions. Hypopigmentation may persist for months, even after lesions are treated, and takes time to resolve.

The differential diagnosis of hypopigmented lesions of tinea versicolor includes vitiligo, hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH), secondary syphilis, and pityriasis alba. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations can be performed in the office for TV to reveal short, thick fungal hyphae with multiple spores, often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs.” Use of a Wood’s light may aid in diagnosis. In TV, lesions may fluoresce yellow-green in adjacent follicles, unlike PMH, which characteristically show orange-red follicular fluorescence. A skin biopsy is necessary to rule out hypopgimented mycosis fungoides or syphilis. Histologically in TV, hyphae and spores will be present in the stratum corneum or in hair follicles. These are readily seen with PAS or GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stains. There is usually no inflammation and skin appears “normal.” A biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed PAS positive hyphae.

Treatment for TV can be topical or systemic. Antifungal azole shampoo or creams, selenium sulfide shampoo, sulfur preparations, and allylamine creams have all been reported as useful treatments. Oral itraconazole or fluconazole are often given as systemic treatments. Monthly or weekly topical therapy may help prevent relapse.

This case and the photos were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Short-course DAA therapy may prevent hepatitis transmission in transplant patients

BOSTON – A short course of results of a recent study show.

The regimen, given right before transplantation and for 7 days afterward, reduced the cost of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy and allowed patients to complete hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy before hospital discharge, according to authors of the study, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

If confirmed in subsequent studies, this regimen could become the standard of care for donor-positive, recipient-negative transplantation, said lead study author Jordan J. Feld, MD, R. Phelan Chair in translational liver disease research at the University of Toronto and research director at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“Transplant recipients are understandably nervous about accepting organs from people with HCV infection,” said Dr. Feld in a press release. “This very short therapy allows them to leave hospital free of HCV, which is a huge benefit. Not only is it cheaper and likely safer, but the patients really prefer not having to worry about HCV with all of the other challenges after a transplant.”

Results of this study come at a time when the proportion of overdose death organ donors is on the rise, from just 1% in 2000 to 15% in 2016, according to Dr. Feld. Overdose deaths account for the largest percentage of HCV-infected donors, most of whom are young and often otherwise healthy, he added.

Recipients of HCV-infected organs can be cured after transplant as a number of studies have previously shown. However, preventing transmission would be better than cure, Dr. Feld said, in part because of issues with drug-drug interactions, potential for relapse, and issues with procuring the drugs after transplant.

Accordingly, Dr. Feld and colleagues sought to evaluate “preemptive” treatment with DAA therapy combined with ezetimibe, which they said has been shown to inhibit HCV entry blockers. The recipients, who were listed for heart, lung, kidney, or kidney-pancreas transplant, were given glecaprevir/pibrentasvir plus ezetimibe starting 6-12 hours prior to transplantation, and then daily for 7 days.

The median age was 36 years for the 16 donors reported, and 61 years for the 25 recipients. Most recipients (12 patients) had a lung transplant, while 8 had a heart transplant, 4 had a kidney transplant, and 1 had a kidney-pancreas transplant.

There were no virologic failures, according to the investigators, with sustained virologic response (SVR) after 6 weeks in 7 patients, and SVR after 12 weeks in the remaining 18. Three recipients did have detectable HCV RNA, though all cleared and had SVR at 6 weeks in one case, and SVR at 12 weeks in the other two, according to the investigators’ report.

Of 22 serious adverse events noted in the study, 1 was considered treatment related, according to the report, and there were 2 deaths among lung transplant patients, caused by sepsis in 1 case to sepsis and subarachnoid hemorrhage in another.

It’s not clear whether ezetimibe is needed in this short-duration regimen, but in any case, it is well tolerated and inexpensive, and so there is “minimal downside” to include it, Dr. Feld and coinvestigators wrote in their report.

Dr. Feld reported disclosures related to Abbvie, Abbott, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

SOURCE: Feld JJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 38.

BOSTON – A short course of results of a recent study show.

The regimen, given right before transplantation and for 7 days afterward, reduced the cost of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy and allowed patients to complete hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy before hospital discharge, according to authors of the study, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

If confirmed in subsequent studies, this regimen could become the standard of care for donor-positive, recipient-negative transplantation, said lead study author Jordan J. Feld, MD, R. Phelan Chair in translational liver disease research at the University of Toronto and research director at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“Transplant recipients are understandably nervous about accepting organs from people with HCV infection,” said Dr. Feld in a press release. “This very short therapy allows them to leave hospital free of HCV, which is a huge benefit. Not only is it cheaper and likely safer, but the patients really prefer not having to worry about HCV with all of the other challenges after a transplant.”

Results of this study come at a time when the proportion of overdose death organ donors is on the rise, from just 1% in 2000 to 15% in 2016, according to Dr. Feld. Overdose deaths account for the largest percentage of HCV-infected donors, most of whom are young and often otherwise healthy, he added.

Recipients of HCV-infected organs can be cured after transplant as a number of studies have previously shown. However, preventing transmission would be better than cure, Dr. Feld said, in part because of issues with drug-drug interactions, potential for relapse, and issues with procuring the drugs after transplant.

Accordingly, Dr. Feld and colleagues sought to evaluate “preemptive” treatment with DAA therapy combined with ezetimibe, which they said has been shown to inhibit HCV entry blockers. The recipients, who were listed for heart, lung, kidney, or kidney-pancreas transplant, were given glecaprevir/pibrentasvir plus ezetimibe starting 6-12 hours prior to transplantation, and then daily for 7 days.

The median age was 36 years for the 16 donors reported, and 61 years for the 25 recipients. Most recipients (12 patients) had a lung transplant, while 8 had a heart transplant, 4 had a kidney transplant, and 1 had a kidney-pancreas transplant.

There were no virologic failures, according to the investigators, with sustained virologic response (SVR) after 6 weeks in 7 patients, and SVR after 12 weeks in the remaining 18. Three recipients did have detectable HCV RNA, though all cleared and had SVR at 6 weeks in one case, and SVR at 12 weeks in the other two, according to the investigators’ report.

Of 22 serious adverse events noted in the study, 1 was considered treatment related, according to the report, and there were 2 deaths among lung transplant patients, caused by sepsis in 1 case to sepsis and subarachnoid hemorrhage in another.

It’s not clear whether ezetimibe is needed in this short-duration regimen, but in any case, it is well tolerated and inexpensive, and so there is “minimal downside” to include it, Dr. Feld and coinvestigators wrote in their report.

Dr. Feld reported disclosures related to Abbvie, Abbott, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

SOURCE: Feld JJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 38.

BOSTON – A short course of results of a recent study show.

The regimen, given right before transplantation and for 7 days afterward, reduced the cost of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy and allowed patients to complete hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy before hospital discharge, according to authors of the study, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

If confirmed in subsequent studies, this regimen could become the standard of care for donor-positive, recipient-negative transplantation, said lead study author Jordan J. Feld, MD, R. Phelan Chair in translational liver disease research at the University of Toronto and research director at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“Transplant recipients are understandably nervous about accepting organs from people with HCV infection,” said Dr. Feld in a press release. “This very short therapy allows them to leave hospital free of HCV, which is a huge benefit. Not only is it cheaper and likely safer, but the patients really prefer not having to worry about HCV with all of the other challenges after a transplant.”

Results of this study come at a time when the proportion of overdose death organ donors is on the rise, from just 1% in 2000 to 15% in 2016, according to Dr. Feld. Overdose deaths account for the largest percentage of HCV-infected donors, most of whom are young and often otherwise healthy, he added.

Recipients of HCV-infected organs can be cured after transplant as a number of studies have previously shown. However, preventing transmission would be better than cure, Dr. Feld said, in part because of issues with drug-drug interactions, potential for relapse, and issues with procuring the drugs after transplant.

Accordingly, Dr. Feld and colleagues sought to evaluate “preemptive” treatment with DAA therapy combined with ezetimibe, which they said has been shown to inhibit HCV entry blockers. The recipients, who were listed for heart, lung, kidney, or kidney-pancreas transplant, were given glecaprevir/pibrentasvir plus ezetimibe starting 6-12 hours prior to transplantation, and then daily for 7 days.

The median age was 36 years for the 16 donors reported, and 61 years for the 25 recipients. Most recipients (12 patients) had a lung transplant, while 8 had a heart transplant, 4 had a kidney transplant, and 1 had a kidney-pancreas transplant.

There were no virologic failures, according to the investigators, with sustained virologic response (SVR) after 6 weeks in 7 patients, and SVR after 12 weeks in the remaining 18. Three recipients did have detectable HCV RNA, though all cleared and had SVR at 6 weeks in one case, and SVR at 12 weeks in the other two, according to the investigators’ report.

Of 22 serious adverse events noted in the study, 1 was considered treatment related, according to the report, and there were 2 deaths among lung transplant patients, caused by sepsis in 1 case to sepsis and subarachnoid hemorrhage in another.

It’s not clear whether ezetimibe is needed in this short-duration regimen, but in any case, it is well tolerated and inexpensive, and so there is “minimal downside” to include it, Dr. Feld and coinvestigators wrote in their report.

Dr. Feld reported disclosures related to Abbvie, Abbott, Enanta Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

SOURCE: Feld JJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 38.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2019

Even low-dose steroids increase DMARD infection risk

ATLANTA – Concomitant use of even low-dose steroids increases the risk of serious infections with antirheumatic drugs, according to a review of 170,357 Medicare patients by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Infections are a well-known side effect of high-dose glucocorticoids, but there’s been debate about prednisone doses in the 5-10 mg/day range. Guidelines generally advise tapering RA patients off steroids after they start a biologic or methotrexate, but that doesn’t always happen because there’s a common perception that low-dose steroids are safe, said lead investigator Michael George, MD, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at the university.

“Many people continue low-dose steroids over the long term, but even low dose seems to be associated with infection. It’s a small risk, but it should be something you are aware of; for some patients, it might be quite important,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The team wanted to mimic real-world practice, so they compared infection incidence between the 53% of patients who were not on low-dose steroids with the 47% who were after at least 6 months of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. About 56% of patients were on methotrexate, with the rest on biologics or a targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD). Average follow up was an additional 6 months, but some people were followed for several years; prednisone 5 mg/day or less was the most common dose.

There were 20,630 serious infections requiring hospitalization, most often urinary tract infection, pneumonia, bacteremia/septicemia, and skin or soft-tissue infections. The crude incidence was 11 per 100 person-years.

After propensity-score weighting to balance out about 50 potential confounders, the predicted 1-year incidence of infection was 9.3% among patients not on steroids. Among those on up to 5 mg/day of prednisone, it was 12.5%; among those on 5-10 mg/day, 17.2%; and among those on more than 10 mg/day, 23.9%.

Glucocorticoids were associated with a 37% increased rate of serious infections, even with doses at or below 5mg/day. The effect “was really similar” whether people were on a biologic, tsDMARD, or methotrexate, which was “surprising,” Dr. George said.

“When I see a patient now who is on long-term, low-dose prednisone, I don’t just say ‘okay, that’s probably safe.’ I think really hard about how much benefit they’re getting. For some people, that means I try to get them off it,” he said. For those who flare otherwise, “I might continue them on it, but recognize there is likely some risk.”

The magnitude of the infection risk was similar to that reported with tumor necrosis factors inhibitors, which might reassure patients who are reluctant to switch to a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

“Now I can say you’ve been taking 10 mg prednisone a day, and that’s probably at least as risky,” Dr. George said.

Frequency of office visits, hospitalizations, and ED visits, as well as prior infections, comorbidities, nursing-home admissions, and use of durable medical equipment were among the potential confounders controlled for in the analysis. They stood in for direct markers of RA severity, which weren’t available in the data. “We spent a lot of time trying to make sure our groups were as similar as possible in every way except prednisone use,” he said.

Patients were in their late 60s on average, 71% white, and 81% were women. People with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, cancer, or HIV were excluded. Dr. George said the next step is to run the same analysis in a younger cohort.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. George disclosed relationships with AbbVie and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: George M et al. ACR 2019, Abstract 848

ATLANTA – Concomitant use of even low-dose steroids increases the risk of serious infections with antirheumatic drugs, according to a review of 170,357 Medicare patients by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Infections are a well-known side effect of high-dose glucocorticoids, but there’s been debate about prednisone doses in the 5-10 mg/day range. Guidelines generally advise tapering RA patients off steroids after they start a biologic or methotrexate, but that doesn’t always happen because there’s a common perception that low-dose steroids are safe, said lead investigator Michael George, MD, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at the university.

“Many people continue low-dose steroids over the long term, but even low dose seems to be associated with infection. It’s a small risk, but it should be something you are aware of; for some patients, it might be quite important,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The team wanted to mimic real-world practice, so they compared infection incidence between the 53% of patients who were not on low-dose steroids with the 47% who were after at least 6 months of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. About 56% of patients were on methotrexate, with the rest on biologics or a targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD). Average follow up was an additional 6 months, but some people were followed for several years; prednisone 5 mg/day or less was the most common dose.

There were 20,630 serious infections requiring hospitalization, most often urinary tract infection, pneumonia, bacteremia/septicemia, and skin or soft-tissue infections. The crude incidence was 11 per 100 person-years.

After propensity-score weighting to balance out about 50 potential confounders, the predicted 1-year incidence of infection was 9.3% among patients not on steroids. Among those on up to 5 mg/day of prednisone, it was 12.5%; among those on 5-10 mg/day, 17.2%; and among those on more than 10 mg/day, 23.9%.

Glucocorticoids were associated with a 37% increased rate of serious infections, even with doses at or below 5mg/day. The effect “was really similar” whether people were on a biologic, tsDMARD, or methotrexate, which was “surprising,” Dr. George said.

“When I see a patient now who is on long-term, low-dose prednisone, I don’t just say ‘okay, that’s probably safe.’ I think really hard about how much benefit they’re getting. For some people, that means I try to get them off it,” he said. For those who flare otherwise, “I might continue them on it, but recognize there is likely some risk.”

The magnitude of the infection risk was similar to that reported with tumor necrosis factors inhibitors, which might reassure patients who are reluctant to switch to a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

“Now I can say you’ve been taking 10 mg prednisone a day, and that’s probably at least as risky,” Dr. George said.

Frequency of office visits, hospitalizations, and ED visits, as well as prior infections, comorbidities, nursing-home admissions, and use of durable medical equipment were among the potential confounders controlled for in the analysis. They stood in for direct markers of RA severity, which weren’t available in the data. “We spent a lot of time trying to make sure our groups were as similar as possible in every way except prednisone use,” he said.

Patients were in their late 60s on average, 71% white, and 81% were women. People with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, cancer, or HIV were excluded. Dr. George said the next step is to run the same analysis in a younger cohort.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. George disclosed relationships with AbbVie and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: George M et al. ACR 2019, Abstract 848

ATLANTA – Concomitant use of even low-dose steroids increases the risk of serious infections with antirheumatic drugs, according to a review of 170,357 Medicare patients by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Infections are a well-known side effect of high-dose glucocorticoids, but there’s been debate about prednisone doses in the 5-10 mg/day range. Guidelines generally advise tapering RA patients off steroids after they start a biologic or methotrexate, but that doesn’t always happen because there’s a common perception that low-dose steroids are safe, said lead investigator Michael George, MD, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at the university.

“Many people continue low-dose steroids over the long term, but even low dose seems to be associated with infection. It’s a small risk, but it should be something you are aware of; for some patients, it might be quite important,” he said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The team wanted to mimic real-world practice, so they compared infection incidence between the 53% of patients who were not on low-dose steroids with the 47% who were after at least 6 months of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. About 56% of patients were on methotrexate, with the rest on biologics or a targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD). Average follow up was an additional 6 months, but some people were followed for several years; prednisone 5 mg/day or less was the most common dose.

There were 20,630 serious infections requiring hospitalization, most often urinary tract infection, pneumonia, bacteremia/septicemia, and skin or soft-tissue infections. The crude incidence was 11 per 100 person-years.

After propensity-score weighting to balance out about 50 potential confounders, the predicted 1-year incidence of infection was 9.3% among patients not on steroids. Among those on up to 5 mg/day of prednisone, it was 12.5%; among those on 5-10 mg/day, 17.2%; and among those on more than 10 mg/day, 23.9%.

Glucocorticoids were associated with a 37% increased rate of serious infections, even with doses at or below 5mg/day. The effect “was really similar” whether people were on a biologic, tsDMARD, or methotrexate, which was “surprising,” Dr. George said.

“When I see a patient now who is on long-term, low-dose prednisone, I don’t just say ‘okay, that’s probably safe.’ I think really hard about how much benefit they’re getting. For some people, that means I try to get them off it,” he said. For those who flare otherwise, “I might continue them on it, but recognize there is likely some risk.”

The magnitude of the infection risk was similar to that reported with tumor necrosis factors inhibitors, which might reassure patients who are reluctant to switch to a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

“Now I can say you’ve been taking 10 mg prednisone a day, and that’s probably at least as risky,” Dr. George said.

Frequency of office visits, hospitalizations, and ED visits, as well as prior infections, comorbidities, nursing-home admissions, and use of durable medical equipment were among the potential confounders controlled for in the analysis. They stood in for direct markers of RA severity, which weren’t available in the data. “We spent a lot of time trying to make sure our groups were as similar as possible in every way except prednisone use,” he said.

Patients were in their late 60s on average, 71% white, and 81% were women. People with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, cancer, or HIV were excluded. Dr. George said the next step is to run the same analysis in a younger cohort.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. George disclosed relationships with AbbVie and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: George M et al. ACR 2019, Abstract 848

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

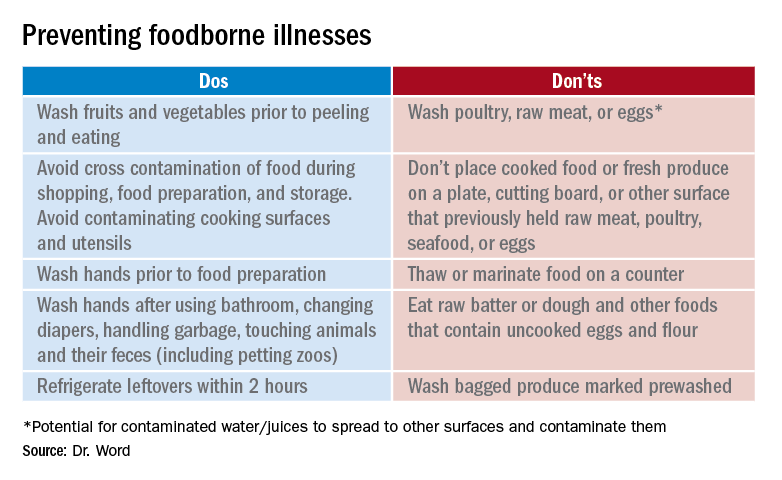

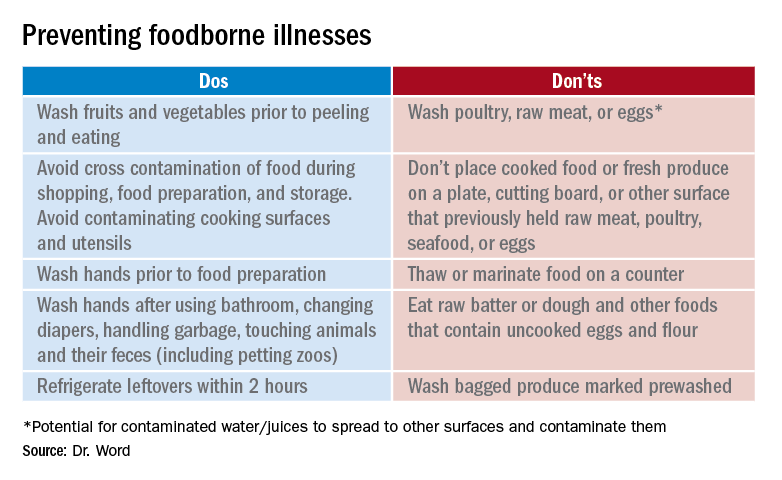

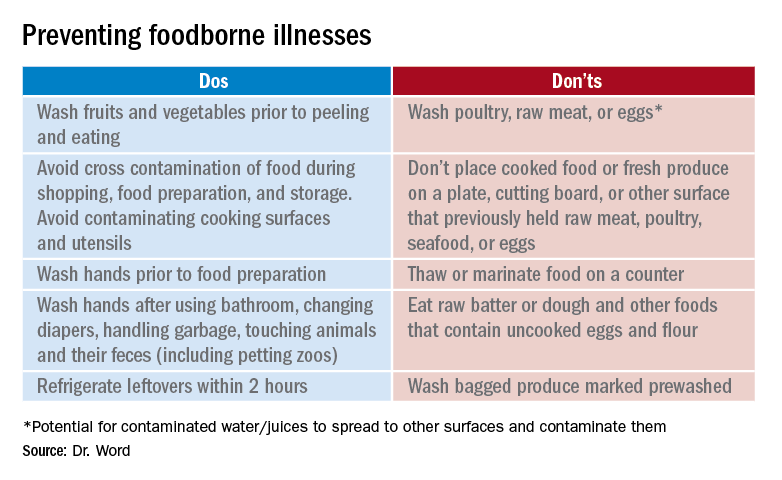

Don’t let a foodborne illness dampen the holiday season

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854

4. Appendix VII: Clinical syndromes associated with foodborne diseases, Red Book online, 31st ed. (Washington DC: Red Book online, 2018, pp. 1086-92).

5. Foodkeeper App available at the App store. Provides appropriate food storage information; food recalls also are available.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a foodborne disease occurs in one in six persons (48 million), resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths annually in the United States. The Foodborne Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program monitors cases of eight laboratory diagnosed infections from 10 U.S. sites (covering 15% of the U.S. population). Monitored organisms include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia. In 2018, FoodNet identified 25,606 cases of infection, 5,893 hospitalizations, and 120 deaths. The incidence of infection (cases/100,000) was highest for Campylobacter (20), Salmonella (18), STEC (6), Shigella (5), Vibrio (1), Yersinia (0.9), Cyclospora (0.7), and Listeria (0.3). How might these pathogens affect your patients? First, a quick review about the four more common infections. Treatment is beyond the scope of our discussion and you are referred to the 2018-2021 Red Book for assistance. The goal of this column is to prevent your patients from becoming a statistic this holiday season.

Campylobacter

It has been the most common infection reported in FoodNet since 2013. Clinically, patients present with fever, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea. However, bloody diarrhea maybe the only symptom in neonates and young infants. Abdominal pain can mimic acute appendicitis or intussusception. Bacteremia is rare but has been reported in the elderly and in some patients with underlying conditions. During convalescence, immunoreactive complications including Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, and erythema nodosum may occur. In patients with diarrhea, Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli are the most frequently isolated species.

Campylobacter is present in the intestinal tract of both domestic and wild birds and animals. Transmission is via consumption of contaminated food or water. Undercooked poultry, untreated water, and unpasteurized milk are the three main vehicles of transmission. Campylobacter can be isolated in stool and blood, however isolation from stool requires special media. Rehydration is the primary therapy. Use of azithromycin or erythromycin can shorten both the duration of symptoms and bacterial shedding.

Salmonella

Nontyphoidal salmonella (NTS) are responsible for a variety of infections including asymptomatic carriage, gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and serious focal infections. Gastroenteritis is the most common illness and is manifested as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. If bacteremia occurs, up to 10% of patients will develop focal infections. Invasive disease occurs most frequently in infants, persons with hemoglobinopathies, immunosuppressive disorders, and malignancies. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species, S. enterica and S. bongori with S. enterica subspecies accounting for about half of culture-confirmed Salmonella isolates reported by public health laboratories.

Although infections are more common in the summer, infections can occur year-round. In 2018, the CDC investigated at least 15 food-related NTS outbreaks and 6 have been investigated so far in 2019. In industrialized countries, acquisition usually occurs from ingestion of poultry, eggs, and milk products. Infection also has been reported after animal contact and consumption of fresh produce, meats, and contaminated water. Ground beef is the source of the November 2019 outbreak of S. dublin. Diarrhea develops within 12-72 hours. Salmonella can be isolated from stool, blood, and urine. Treatment usually is not indicated for uncomplicated gastroenteritis. While benefit has not been proven, it is recommended for those at increased risk for developing invasive disease.

Shigella

Shigella is the classic cause of colonic or dysenteric diarrhea. Humans are the primary hosts but other primates can be infected. Transmission occurs through direct person-to-person spread, from ingestion of contaminated food and water, and contact with contaminated inanimate objects. Bacteria can survive up to 6 months in food and 30 days in water. As few as 10 organisms can initiate disease. Typically mucoid or bloody diarrhea with abdominal cramps and fever occurs 1-7 days following exposure. Isolation is from stool. Bacteremia is unusual. Therapy is recommended for severe disease.

Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC)

STEC causes hemorrhagic colitis, which can be complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. While E. coli O157:H7 is the serotype most often implicated, other serotypes can cause disease. STEC is shed in feces of cattle and other animals. Infection most often is associated with ingestion of undercooked ground beef, but outbreaks also have confirmed that contaminated leafy vegetables, drinking water, peanut butter, and unpasteurized milk have been the source. Symptoms usually develop 3 to 4 days after exposure. Stools initially may be nonbloody. Abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea occur over the next 2-3 days. Fever often is absent or low grade. Stools should be sent for culture and Shiga toxin for diagnosis. Antimicrobial treatment generally is not warranted if STEC is suspected or diagnosed.

Prevention

It seems so simple. Here are the basic guidelines:

- Clean. Wash hands and surfaces frequently.

- Separate. Separate raw meats and eggs from other foods.

- Cook. Cook all meats to the right temperature.

- Chill. Refrigerate food properly.

Finally, two comments about food poisoning:

Abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramping due to staphylococcal food poisoning begins 30 minutes to 6 hours after ingestion of food contaminated by enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus which is usually introduced by a food preparer with a purulent lesion. Food left at room temperature allows bacteria to multiply and produce a heat stable toxin. Individuals with purulent lesions of the hands, face, eyes, or nose should not be involved with food preparation.

Clostridium perfringens is the second most common bacterial cause of food poisoning. Symptoms (watery diarrhea and cramping) begin 6-24 hours after ingestion of C. perfringens spores not killed during cooking, which now have multiplied in food left at room temperature that was inadequately reheated. Illness is caused by the production of enterotoxin in the intestine. Outbreaks occur most often in November and December.

This article was updated on 11/12/19.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Information sources

1. foodsafety.gov

2. cdc.gov/foodsafety

3. The United States Department of Agriculture Meat and Poultry Hotline: 888-674-6854