User login

COVID-19 in children, pregnant women: What do we know?

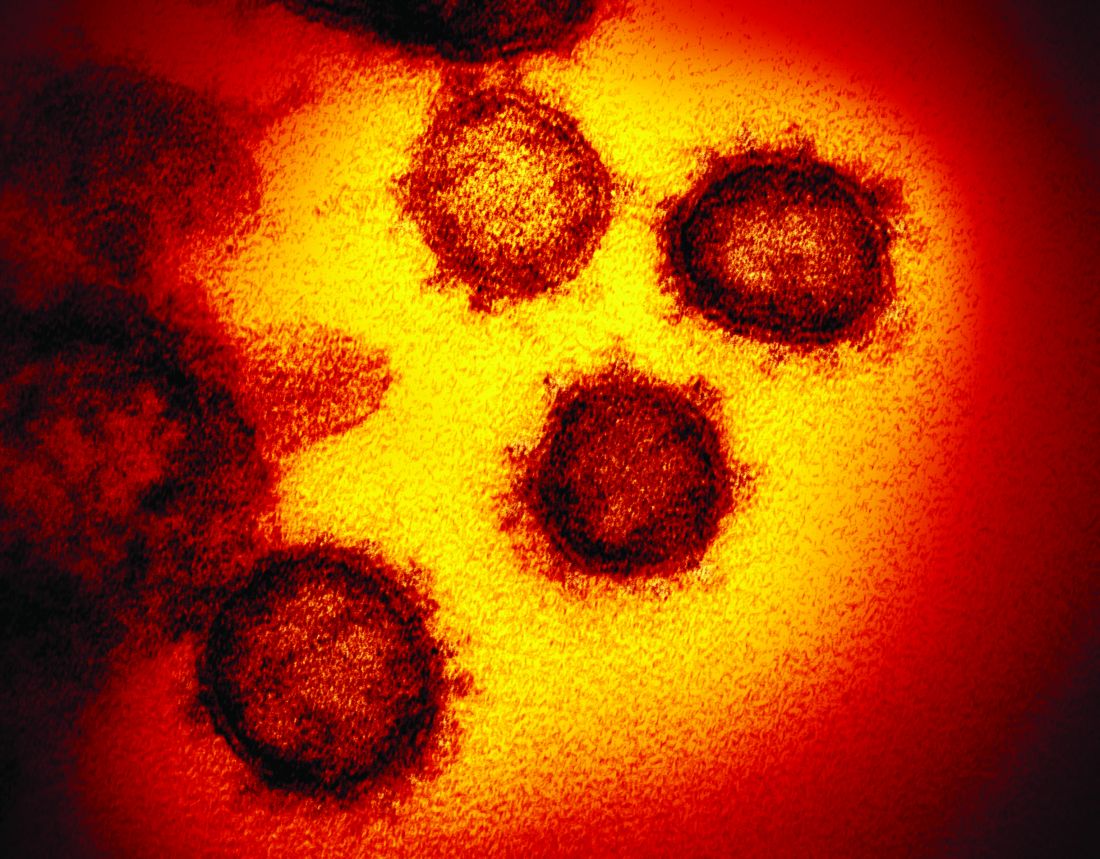

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

Detection of COVID-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical question: What were the clinical characteristics of children in Wuhan, China hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2?

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was recently described by researchers in Wuhan, China.1 However, there has been limited discussion on how the disease has affected children. Based on the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention report, Wu et al. found that 1% of the affected population was less than 10 years, and another 1% of the affected population was 10-19 years.2 However, little information regarding hospitalizations of children with viral infections was previously reported.

Study design: A retrospective analysis of hospitalized children.

Setting: Three sites of a multisite urban teaching hospital in central Wuhan, China.

Synopsis: Over an 8-day period, hospitalized pediatric patients were retrospectively enrolled into this study. The authors defined pediatric patients as those aged 16 years or younger. The patients had one throat swab specimen collected on admission. Throat swab specimens were tested for viral etiologies. In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the throat samples were retrospectively tested for SARS-CoV-2. If two independent experiments and a clinically verified diagnostic test confirmed the SARS-CoV-2, the cases were confirmed as COVID-19 cases. During the 8-day period, 366 hospitalized pediatric patients were included in the study. Of the 366 patients, 6 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, while 23 tested positive for influenza A and 20 tested positive for influenza B. The median age of the six patients was 3 years (range, 1-7 years), and all were previously healthy. All six pediatric patients with COVID-19 had high fevers (greater than 39°C), cough, and lymphopenia. Four of the six affected patients had vomiting and leukopenia, while three of the six patients had neutropenia. Four of the six affected patients had pneumonia, as diagnosed on CT scans. Of the six patients, one patient was admitted to the ICU and received intravenous immunoglobulin. The patient admitted to ICU underwent a CT scan which showed “patchy ground-glass opacities in both lungs,” while three of the five children requiring non-ICU hospitalization had chest radiographs showing “patchy shadows in both lungs.” The median length of stay in the hospital was 7.5 days (range, 5-13 days).

Bottom line: COVID-19 causes moderate to severe respiratory illness in pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2, possibly leading to critical illness. During this time period of the Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak, pediatric patients were more likely to be hospitalized with influenza A or B, than they were with SARS-CoV-2.

Citation: Liu W et al. Detection of Covid-19 in Children in Early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of the Hospitalist.

References

1. Zhu N et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24 (Epub ahead of print).

From the Hospitalist editors: The pediatrics “In the Literature” series generally focuses on original articles. However, given the urgency to learn more about SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 pandemic and the limited literature about hospitalized pediatric patients with the disease, the editors of the Hospitalist thought it was appropriate to share an article reviewing this letter that was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

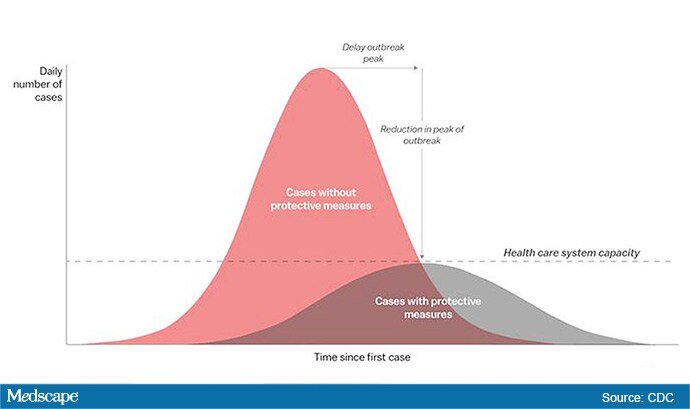

Flattening the curve: Viral graphic shows COVID-19 containment needs

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

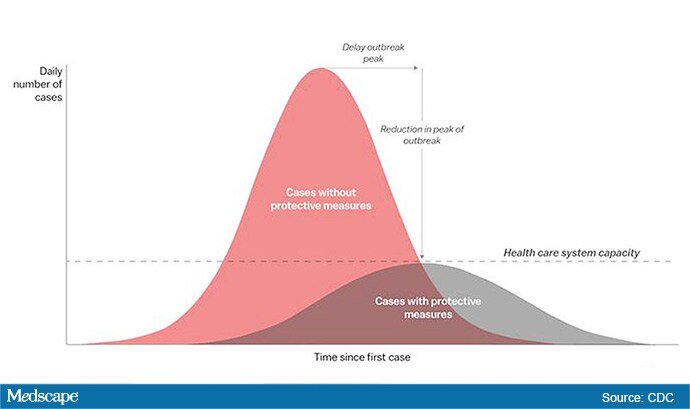

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

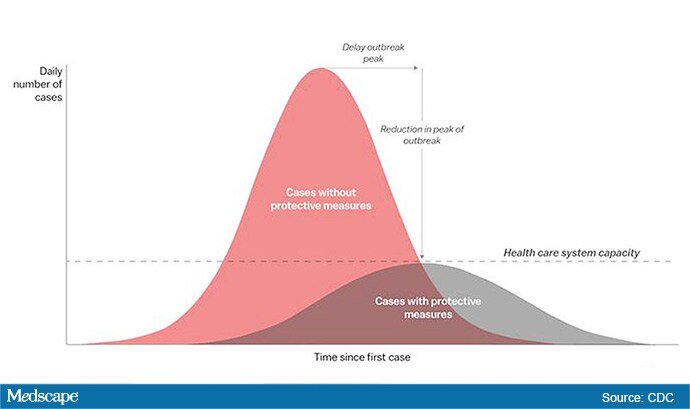

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”

The graphic was developed by visual-data journalist Rosamund Pearce, based on a graphic that had appeared in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) article titled “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza,” the Times reports.

Marrazzo and Grayson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com .

President declares national emergency for COVID-19, ramps up testing capability

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to allow for additional resources to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and announced increased testing capacity in partnership with private industry.

During a March 13 press conference, the president said the declaration would “open up access to up to $50 billion” for states and territories in combating the spread of the disease.

He also called on all states to “set up emergency operation centers, effective immediately” and for every hospital “to activate its emergency preparedness plan so that they can meet the needs of Americans everywhere.”

Additionally, he said the declaration will confer broad new authority on the Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that will allow him to “immediately waive provisions of applicable laws and regulations to give doctors, all hospitals, and health care providers maximum flexibility to respond to the virus and care for patients.”

Some of the powers he highlighted included the ability to waive laws to enable telehealth; to waive certain federal license requirements to allow doctors licensed in one state to offer services in other states; the ability to waive limits on beds in critical access hospitals; and to waive rules that hinder hospitals from hiring additional physicians.

The president also announced that more testing capacity will be made available within the next week, in partnership with private industry.

“We want to make sure that those who need a test can get a test very safely, quickly, and conveniently, but we don’t want people to take a test if we feel that they shouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

To help make that determination, a website, developed with Google, is expected to be launched the weekend of March 13 to will allow individuals to input their symptoms and risk factors to help determine if they should be tested. If certain criteria are met, the website will provide locations for drive-through testing facilities. Individuals will be tested using a nasal swab and will receive results within 24-36 hours.

The testing is being done in partnership with retailers, including Target and Walmart (who are providing parking lot space for the pop-up testing facilities) and testing companies LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

The new test was developed by Roche and just received emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration.

“We therefore expect up to a half-million additional tests will be available early next week,” President Trump said, adding that testing locations will “probably” be announced on Sunday, March 15.

A second application for a new test, submitted by Thermo Fisher, is currently under review at the FDA and is expected to be approved within the next 24 hours, he said. This would add an additional 1.4 million tests in the next week and 5 million within a month, according to the president.

After weeks of decline, influenza activity increases slightly

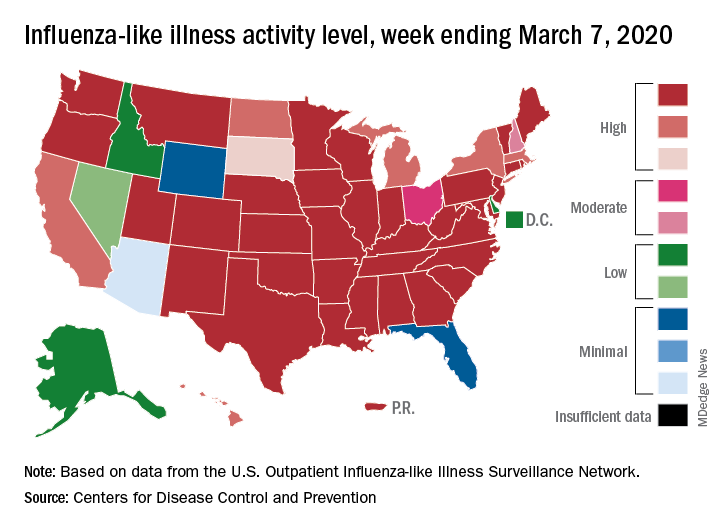

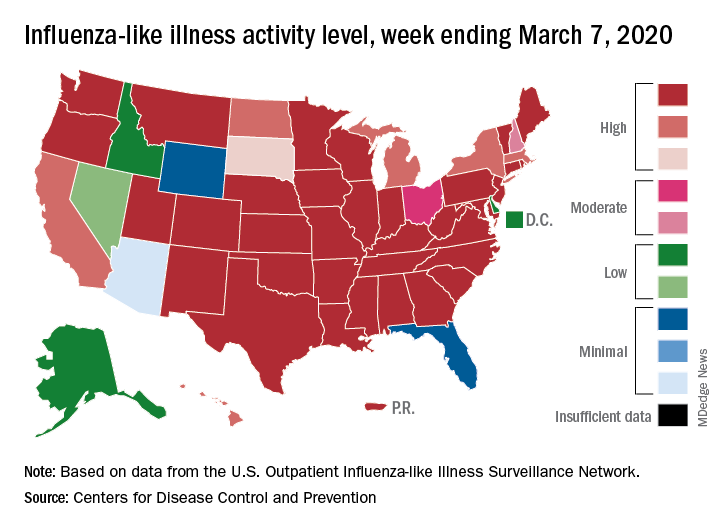

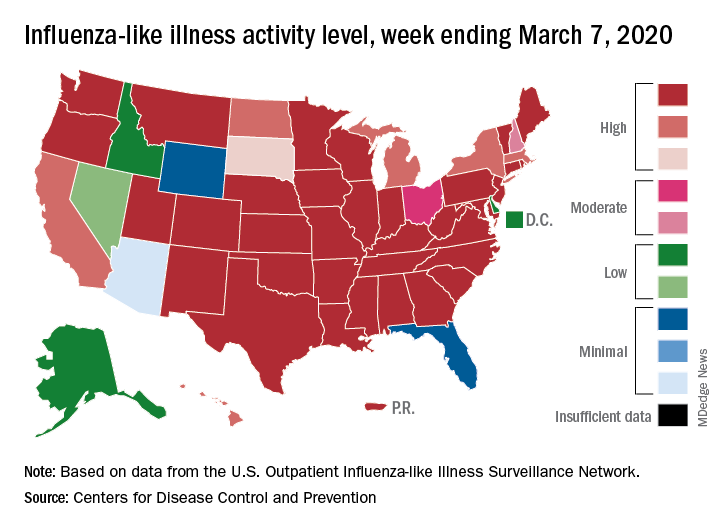

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

The two leading measures of influenza activity – the percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza and the proportion of visits to health care providers for influenza-like illness (ILI) – had been following a similar downward path since mid-February. But during the week ending March 7, their paths diverged, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza dropped for the fourth consecutive week, falling from 26.1% to 21.5%, while the proportion of visits to health care providers for ILI increased from 5.1% to 5.2%, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

One possible explanation for that rise: “The largest increases in ILI activity occurred in areas of the country where COVID-19 is most prevalent. More people may be seeking care for respiratory illness than usual at this time,” the influenza division said March 13 in its weekly Fluview report.

This week’s map puts 34 states and Puerto Rico at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, one more state than the week before, and 43 jurisdictions in the “high” range of 8-10, compared with 42 the previous week, the CDC said.

Rates of hospitalizations associated with influenza “remain moderate compared to recent seasons, but rates for children 0-4 years and adults 18-49 years are now the highest CDC has on record for these age groups, surpassing rates reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic,” the Fluview report said. Rates for children aged 5-17 years “are higher than any recent regular season but remain lower than rates experienced by this age group during the pandemic.”

The number of pediatric deaths this season is now up to 144, equaling the total for all of the 2018-2019 season. This year’s count led the CDC to invoke 2009 again, since it “is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-2005, except for the 2009 pandemic.”

For the 2019-2020 season so far there have been 36 million flu illnesses, 370,000 hospitalizations, and 22,000 deaths from flu and pneumonia, the CDC estimated.

FDA warns of serious infection risk after FMT

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Safety Alert warning of the potential risk of serious, life-threatening infection in patients who receive fecal microbiota transplant for Clostridioides difficile infection.

The FDA has received six reports of infection associated with fecal microbiota transplant from a stool bank company based in the United States: Two patients had enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infection, and four had shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). The two EPEC infections came from two separate donors, but the four STEC infections came from a single donor, according to the FDA.

In addition, two patients died after receiving fecal microbiota transplant from the donor associated with the STEC infections. These patients died before any of the STEC infections were reported to the FDA; as their stool was not tested for STEC, it is unclear whether it contributed to their deaths.

The use of fecal microbiota transplant is still investigational, and as such, patients should be made aware by health care providers of the risks, which include the potential for transmission of pathogenic bacteria and the resultant adverse events, the FDA said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Safety Alert warning of the potential risk of serious, life-threatening infection in patients who receive fecal microbiota transplant for Clostridioides difficile infection.

The FDA has received six reports of infection associated with fecal microbiota transplant from a stool bank company based in the United States: Two patients had enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infection, and four had shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). The two EPEC infections came from two separate donors, but the four STEC infections came from a single donor, according to the FDA.

In addition, two patients died after receiving fecal microbiota transplant from the donor associated with the STEC infections. These patients died before any of the STEC infections were reported to the FDA; as their stool was not tested for STEC, it is unclear whether it contributed to their deaths.

The use of fecal microbiota transplant is still investigational, and as such, patients should be made aware by health care providers of the risks, which include the potential for transmission of pathogenic bacteria and the resultant adverse events, the FDA said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a Safety Alert warning of the potential risk of serious, life-threatening infection in patients who receive fecal microbiota transplant for Clostridioides difficile infection.

The FDA has received six reports of infection associated with fecal microbiota transplant from a stool bank company based in the United States: Two patients had enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infection, and four had shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). The two EPEC infections came from two separate donors, but the four STEC infections came from a single donor, according to the FDA.

In addition, two patients died after receiving fecal microbiota transplant from the donor associated with the STEC infections. These patients died before any of the STEC infections were reported to the FDA; as their stool was not tested for STEC, it is unclear whether it contributed to their deaths.

The use of fecal microbiota transplant is still investigational, and as such, patients should be made aware by health care providers of the risks, which include the potential for transmission of pathogenic bacteria and the resultant adverse events, the FDA said in the press release.

A point-of-care urine test is on the way for PrEP adherence

A simple, quick point-of-care urine test for tenofovir adherence, similar to an OTC-pregnancy test, has an accuracy of 99.6% versus laboratory testing, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

A few drops of urine yield results in 5 minutes, and tell if patients have been taking tenofovir, a key component of HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medications, within the previous 4-7 days. Abbott Rapid Diagnostics is gearing up to market the test widely in the United States, and it won’t be very expensive, according to lead investigator Matthew Spinelli, MD, a clinical fellow and HIV/AIDS researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

It’s an alternative to the usual approach, measuring tenofovir levels in hair, blood, or urine by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. That approach is expensive and requires trained personnel, and the results can take a while. Dr. Spinelli and colleagues saw the need for a quicker, easier way for use in the clinic, since real-time adherence results are most likely to make a difference, he said at the meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but was held online instead this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

Self-report, meanwhile, is notoriously unreliable. Over 90% of people in two previous PrEP studies said they were taking their medications, but only about a quarter had tenofovir in their plasma.

The investigators identified a tenofovir antibody in urine that could be read by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and validated it for adherence accuracy against liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry; they then put the antibody on a test strip to create a lateral flow immunoassay.

After hearing the presentation, moderator Susan Buchbinder, MD, director of HIV prevention research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, called the work “important” and said it “really has the possibility of opening up a lot of new kinds of studies and new kinds of intervention for both prevention and treatment.”

Dr. Spinelli and colleagues pitted the test strip against their laboratory-based ELISA test using 684 stored urine samples from 324 men and women in disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) PrEP projects in Africa and the United States.

Overall, the 505 samples that were positive for tenofovir in the lab test were also positive on the urine strip, yielding 100% sensitivity. Of the 179 negative samples on the lab test, 176 were also negative with the strip, yielding a specificity of 98.3%. The results calculated into nearly perfect accuracy.

“We believe that” the urine test strip “is ready for field testing,” and that “point-of-care adherence testing” will be a boon to both PrEP and HIV treatment. A negative test, for instance, would signal the need for immediate counseling, and the patient would still be in the office to hear it. For HIV, high adherence but also high viral load would signal the need for resistance testing, Dr. Spinelli said.

A white-coat effect is possible; people might take their medication when they know they have an upcoming doctor’s appointment. “We will need to evaluate for [that] with additional studies” comparing point-of-care testing with longer-term metrics, such as drug levels in hair, he said.

The study was published to coincide with Dr. Spinelli’s report (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002322).

The funding source wasn’t reported. Dr. Spinelli had no disclosures. Two investigators were Abbott employees.

SOURCE: Spinelli MA et al. 2020 CROI abstract 91.

A simple, quick point-of-care urine test for tenofovir adherence, similar to an OTC-pregnancy test, has an accuracy of 99.6% versus laboratory testing, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

A few drops of urine yield results in 5 minutes, and tell if patients have been taking tenofovir, a key component of HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medications, within the previous 4-7 days. Abbott Rapid Diagnostics is gearing up to market the test widely in the United States, and it won’t be very expensive, according to lead investigator Matthew Spinelli, MD, a clinical fellow and HIV/AIDS researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

It’s an alternative to the usual approach, measuring tenofovir levels in hair, blood, or urine by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. That approach is expensive and requires trained personnel, and the results can take a while. Dr. Spinelli and colleagues saw the need for a quicker, easier way for use in the clinic, since real-time adherence results are most likely to make a difference, he said at the meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but was held online instead this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

Self-report, meanwhile, is notoriously unreliable. Over 90% of people in two previous PrEP studies said they were taking their medications, but only about a quarter had tenofovir in their plasma.

The investigators identified a tenofovir antibody in urine that could be read by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and validated it for adherence accuracy against liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry; they then put the antibody on a test strip to create a lateral flow immunoassay.

After hearing the presentation, moderator Susan Buchbinder, MD, director of HIV prevention research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, called the work “important” and said it “really has the possibility of opening up a lot of new kinds of studies and new kinds of intervention for both prevention and treatment.”

Dr. Spinelli and colleagues pitted the test strip against their laboratory-based ELISA test using 684 stored urine samples from 324 men and women in disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) PrEP projects in Africa and the United States.

Overall, the 505 samples that were positive for tenofovir in the lab test were also positive on the urine strip, yielding 100% sensitivity. Of the 179 negative samples on the lab test, 176 were also negative with the strip, yielding a specificity of 98.3%. The results calculated into nearly perfect accuracy.

“We believe that” the urine test strip “is ready for field testing,” and that “point-of-care adherence testing” will be a boon to both PrEP and HIV treatment. A negative test, for instance, would signal the need for immediate counseling, and the patient would still be in the office to hear it. For HIV, high adherence but also high viral load would signal the need for resistance testing, Dr. Spinelli said.

A white-coat effect is possible; people might take their medication when they know they have an upcoming doctor’s appointment. “We will need to evaluate for [that] with additional studies” comparing point-of-care testing with longer-term metrics, such as drug levels in hair, he said.

The study was published to coincide with Dr. Spinelli’s report (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002322).

The funding source wasn’t reported. Dr. Spinelli had no disclosures. Two investigators were Abbott employees.

SOURCE: Spinelli MA et al. 2020 CROI abstract 91.

A simple, quick point-of-care urine test for tenofovir adherence, similar to an OTC-pregnancy test, has an accuracy of 99.6% versus laboratory testing, according to a report at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

A few drops of urine yield results in 5 minutes, and tell if patients have been taking tenofovir, a key component of HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medications, within the previous 4-7 days. Abbott Rapid Diagnostics is gearing up to market the test widely in the United States, and it won’t be very expensive, according to lead investigator Matthew Spinelli, MD, a clinical fellow and HIV/AIDS researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

It’s an alternative to the usual approach, measuring tenofovir levels in hair, blood, or urine by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. That approach is expensive and requires trained personnel, and the results can take a while. Dr. Spinelli and colleagues saw the need for a quicker, easier way for use in the clinic, since real-time adherence results are most likely to make a difference, he said at the meeting, which was scheduled to be in Boston, but was held online instead this year because of concerns about spreading the COVID-19 virus.

Self-report, meanwhile, is notoriously unreliable. Over 90% of people in two previous PrEP studies said they were taking their medications, but only about a quarter had tenofovir in their plasma.

The investigators identified a tenofovir antibody in urine that could be read by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and validated it for adherence accuracy against liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry; they then put the antibody on a test strip to create a lateral flow immunoassay.

After hearing the presentation, moderator Susan Buchbinder, MD, director of HIV prevention research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health, called the work “important” and said it “really has the possibility of opening up a lot of new kinds of studies and new kinds of intervention for both prevention and treatment.”

Dr. Spinelli and colleagues pitted the test strip against their laboratory-based ELISA test using 684 stored urine samples from 324 men and women in disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) PrEP projects in Africa and the United States.

Overall, the 505 samples that were positive for tenofovir in the lab test were also positive on the urine strip, yielding 100% sensitivity. Of the 179 negative samples on the lab test, 176 were also negative with the strip, yielding a specificity of 98.3%. The results calculated into nearly perfect accuracy.

“We believe that” the urine test strip “is ready for field testing,” and that “point-of-care adherence testing” will be a boon to both PrEP and HIV treatment. A negative test, for instance, would signal the need for immediate counseling, and the patient would still be in the office to hear it. For HIV, high adherence but also high viral load would signal the need for resistance testing, Dr. Spinelli said.

A white-coat effect is possible; people might take their medication when they know they have an upcoming doctor’s appointment. “We will need to evaluate for [that] with additional studies” comparing point-of-care testing with longer-term metrics, such as drug levels in hair, he said.

The study was published to coincide with Dr. Spinelli’s report (J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020 Mar 10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002322).

The funding source wasn’t reported. Dr. Spinelli had no disclosures. Two investigators were Abbott employees.