User login

‘We will get through this’: Advice for lessening your pandemic anxiety

The COVID-19 pandemic is an experience that is unprecedented in our lifetime. It is having a pervasive effect due to how mysterious, potentially dangerous, and sustained it is. We don’t know how bad it’s going to get or how long it’s going to last. We have natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes, but they are limited in time and scope. But this global pandemic is something we can’t put our arms around just yet, breeding uncertainty, worry, and fear. This is where mental health professionals need to come in.

The populations being affected by this pandemic can be placed into different groups on the basis of their mental health consequences and needs. First you have, for lack of a better term, “the worried well.” These are people with no preexisting mental disorder who are naturally worried by this and are trying to take appropriate actions to protect themselves and prepare. For such individuals, the equivalent of mental health first-aid should be useful (we’ll come back to that in a moment). Given the proper guidance and sources of information, most such people should be able to manage the anxiety, worry, and dysphoria associated with this critical pandemic.

Then there are those who have preexisting mental conditions related to mood, anxiety, stress, or obsessive tendencies. They are probably going to have an increase in their symptoms, and as such, a corresponding need for adjusting treatment. This may require an increase in their existing medications or the addition of an ad hoc medication, or perhaps more frequent contact with their doctor or therapist.

Because travel and direct visitation is discouraged at the moment, virtual methods of communication should be used to speak with these patients. Such methods have long existed but haven’t been adopted in large numbers; this may be the impetus to finally make it happen. Using the telephone, FaceTime, Skype, WebEx, Zoom, and other means of videoconferencing should be feasible. As billing procedures are being adapted for this moment, there’s no reason why individuals shouldn’t be able to contact their mental health provider.

Substance abuse is also a condition vulnerable to the stress effects of this pandemic. This will prompt or tempt those to use substances that they’ve abused or turned to in the past as a way of self-medicating and assuaging their anxiety and worry.

It’s possible that the pandemic could find its way into delusions or exacerbate symptoms, but somewhat paradoxically, people with serious mental illnesses often respond more calmly to crises than do individuals without them. As a result, the number of these patients requiring emergency room admission for possible exacerbation of symptoms is probably not going to be that much greater than normal.

How to Cope With an Unprecedented Situation

For the worried well and for the clinicians who have understandable fears about exposure, there are several things you can try to manage your anxiety. There are concentric circles of concern that you have to maintain. Think of it like the instructions on an airplane when, if there’s a drop in cabin pressure, you’re asked to apply your own oxygen mask first before placing one on your child. In the same way, you must first think about protecting yourself by limiting your exposure and monitoring your own physical state for any symptoms. But then you must be concerned about your family, your friends, and also society. This is a situation where the impulse and the ethos of worrying about your fellow persons—being your brother’s keeper—is imperative.

The epidemic has been successfully managed in some countries, like Singapore and China, which, once they got on top of it, were able to limit contagion in a very dramatic way. But these are authoritarian governments. The United States doesn’t work that way, which is what makes appealing to the principle of caring for others so crucial. You can protect yourself, but if other people aren’t also protected, it may not matter. You have to worry not just about yourself but about everyone else.

When it comes to stress management, I recommend not catastrophizing or watching the news media 24/7. Distract yourself with other work or recreational activities. Reach out and communicate—virtually, of course—with friends, family, and healthcare providers as needed. Staying in touch acts not just as a diversion but also as an outlet for assuaging your feelings, your sense of being in this alone, feeling isolated.

There are also cognitive reframing mechanisms you can employ. Consider that although this is bad, some countries have already gone through it. And we’ll get through it too. You’ll understandably ask yourself what it would mean if you were to be exposed. In most cases you can say, “I’m going to have the flu and symptoms that are not going to be pleasant, but I’ve had the flu or serious sickness before.”

Remember that there are already antiretroviral treatments being tested in clinical trials and showing efficacy. It’s good to know that before this pandemic ends, some of these treatments will probably be clinically applied, mostly to those who are severely affected and in intensive care.

Diagnose yourself. Monitor your state. Determine whether the stress is really having an impact on you. Is it affecting your sleep, appetite, concentration, mood? And if you do have a preexisting psychiatric condition, don’t feel afraid to reach out to your mental health provider. Understand that you’re going to be anxious, which may aggravate your symptoms and require an adjustment in your treatment. That’s okay. It’s to be expected and your provider should be available to help you.

Controlling this outbreak via the same epidemiologic infectious disease prevention guidance that works in authoritarian societies is not going to be applicable here because of the liberties that we experience in American society. What will determine our success is the belief that we’re in this together, that we’re going to help each other. We should be proud of that, as it shows how Americans and people around the world stand up in situations like this.

Let’s also note that even though everybody is affected and undergoing previously unimaginable levels of anticipated stress and dislocation, it’s the healthcare providers who are really on the frontlines. They’re under tremendous pressure to continue to perform heroically, at great risk to themselves. They deserve a real debt of gratitude.

We will get through this, but as we do, it will not end until we’ve undergone an extreme test of our character. I certainly hope and trust that we will be up to it.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Lieberman is chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University. He is a former president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Disclosure: Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Clintara; Intracellular Therapies. Received research grant from Alkermes; Biomarin; EnVivo/Forum; Genentech; Novartis/Novation; Sunovion. Patent: Repligen.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an experience that is unprecedented in our lifetime. It is having a pervasive effect due to how mysterious, potentially dangerous, and sustained it is. We don’t know how bad it’s going to get or how long it’s going to last. We have natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes, but they are limited in time and scope. But this global pandemic is something we can’t put our arms around just yet, breeding uncertainty, worry, and fear. This is where mental health professionals need to come in.

The populations being affected by this pandemic can be placed into different groups on the basis of their mental health consequences and needs. First you have, for lack of a better term, “the worried well.” These are people with no preexisting mental disorder who are naturally worried by this and are trying to take appropriate actions to protect themselves and prepare. For such individuals, the equivalent of mental health first-aid should be useful (we’ll come back to that in a moment). Given the proper guidance and sources of information, most such people should be able to manage the anxiety, worry, and dysphoria associated with this critical pandemic.

Then there are those who have preexisting mental conditions related to mood, anxiety, stress, or obsessive tendencies. They are probably going to have an increase in their symptoms, and as such, a corresponding need for adjusting treatment. This may require an increase in their existing medications or the addition of an ad hoc medication, or perhaps more frequent contact with their doctor or therapist.

Because travel and direct visitation is discouraged at the moment, virtual methods of communication should be used to speak with these patients. Such methods have long existed but haven’t been adopted in large numbers; this may be the impetus to finally make it happen. Using the telephone, FaceTime, Skype, WebEx, Zoom, and other means of videoconferencing should be feasible. As billing procedures are being adapted for this moment, there’s no reason why individuals shouldn’t be able to contact their mental health provider.

Substance abuse is also a condition vulnerable to the stress effects of this pandemic. This will prompt or tempt those to use substances that they’ve abused or turned to in the past as a way of self-medicating and assuaging their anxiety and worry.

It’s possible that the pandemic could find its way into delusions or exacerbate symptoms, but somewhat paradoxically, people with serious mental illnesses often respond more calmly to crises than do individuals without them. As a result, the number of these patients requiring emergency room admission for possible exacerbation of symptoms is probably not going to be that much greater than normal.

How to Cope With an Unprecedented Situation

For the worried well and for the clinicians who have understandable fears about exposure, there are several things you can try to manage your anxiety. There are concentric circles of concern that you have to maintain. Think of it like the instructions on an airplane when, if there’s a drop in cabin pressure, you’re asked to apply your own oxygen mask first before placing one on your child. In the same way, you must first think about protecting yourself by limiting your exposure and monitoring your own physical state for any symptoms. But then you must be concerned about your family, your friends, and also society. This is a situation where the impulse and the ethos of worrying about your fellow persons—being your brother’s keeper—is imperative.

The epidemic has been successfully managed in some countries, like Singapore and China, which, once they got on top of it, were able to limit contagion in a very dramatic way. But these are authoritarian governments. The United States doesn’t work that way, which is what makes appealing to the principle of caring for others so crucial. You can protect yourself, but if other people aren’t also protected, it may not matter. You have to worry not just about yourself but about everyone else.

When it comes to stress management, I recommend not catastrophizing or watching the news media 24/7. Distract yourself with other work or recreational activities. Reach out and communicate—virtually, of course—with friends, family, and healthcare providers as needed. Staying in touch acts not just as a diversion but also as an outlet for assuaging your feelings, your sense of being in this alone, feeling isolated.

There are also cognitive reframing mechanisms you can employ. Consider that although this is bad, some countries have already gone through it. And we’ll get through it too. You’ll understandably ask yourself what it would mean if you were to be exposed. In most cases you can say, “I’m going to have the flu and symptoms that are not going to be pleasant, but I’ve had the flu or serious sickness before.”

Remember that there are already antiretroviral treatments being tested in clinical trials and showing efficacy. It’s good to know that before this pandemic ends, some of these treatments will probably be clinically applied, mostly to those who are severely affected and in intensive care.

Diagnose yourself. Monitor your state. Determine whether the stress is really having an impact on you. Is it affecting your sleep, appetite, concentration, mood? And if you do have a preexisting psychiatric condition, don’t feel afraid to reach out to your mental health provider. Understand that you’re going to be anxious, which may aggravate your symptoms and require an adjustment in your treatment. That’s okay. It’s to be expected and your provider should be available to help you.

Controlling this outbreak via the same epidemiologic infectious disease prevention guidance that works in authoritarian societies is not going to be applicable here because of the liberties that we experience in American society. What will determine our success is the belief that we’re in this together, that we’re going to help each other. We should be proud of that, as it shows how Americans and people around the world stand up in situations like this.

Let’s also note that even though everybody is affected and undergoing previously unimaginable levels of anticipated stress and dislocation, it’s the healthcare providers who are really on the frontlines. They’re under tremendous pressure to continue to perform heroically, at great risk to themselves. They deserve a real debt of gratitude.

We will get through this, but as we do, it will not end until we’ve undergone an extreme test of our character. I certainly hope and trust that we will be up to it.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Lieberman is chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University. He is a former president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Disclosure: Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Clintara; Intracellular Therapies. Received research grant from Alkermes; Biomarin; EnVivo/Forum; Genentech; Novartis/Novation; Sunovion. Patent: Repligen.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an experience that is unprecedented in our lifetime. It is having a pervasive effect due to how mysterious, potentially dangerous, and sustained it is. We don’t know how bad it’s going to get or how long it’s going to last. We have natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes, but they are limited in time and scope. But this global pandemic is something we can’t put our arms around just yet, breeding uncertainty, worry, and fear. This is where mental health professionals need to come in.

The populations being affected by this pandemic can be placed into different groups on the basis of their mental health consequences and needs. First you have, for lack of a better term, “the worried well.” These are people with no preexisting mental disorder who are naturally worried by this and are trying to take appropriate actions to protect themselves and prepare. For such individuals, the equivalent of mental health first-aid should be useful (we’ll come back to that in a moment). Given the proper guidance and sources of information, most such people should be able to manage the anxiety, worry, and dysphoria associated with this critical pandemic.

Then there are those who have preexisting mental conditions related to mood, anxiety, stress, or obsessive tendencies. They are probably going to have an increase in their symptoms, and as such, a corresponding need for adjusting treatment. This may require an increase in their existing medications or the addition of an ad hoc medication, or perhaps more frequent contact with their doctor or therapist.

Because travel and direct visitation is discouraged at the moment, virtual methods of communication should be used to speak with these patients. Such methods have long existed but haven’t been adopted in large numbers; this may be the impetus to finally make it happen. Using the telephone, FaceTime, Skype, WebEx, Zoom, and other means of videoconferencing should be feasible. As billing procedures are being adapted for this moment, there’s no reason why individuals shouldn’t be able to contact their mental health provider.

Substance abuse is also a condition vulnerable to the stress effects of this pandemic. This will prompt or tempt those to use substances that they’ve abused or turned to in the past as a way of self-medicating and assuaging their anxiety and worry.

It’s possible that the pandemic could find its way into delusions or exacerbate symptoms, but somewhat paradoxically, people with serious mental illnesses often respond more calmly to crises than do individuals without them. As a result, the number of these patients requiring emergency room admission for possible exacerbation of symptoms is probably not going to be that much greater than normal.

How to Cope With an Unprecedented Situation

For the worried well and for the clinicians who have understandable fears about exposure, there are several things you can try to manage your anxiety. There are concentric circles of concern that you have to maintain. Think of it like the instructions on an airplane when, if there’s a drop in cabin pressure, you’re asked to apply your own oxygen mask first before placing one on your child. In the same way, you must first think about protecting yourself by limiting your exposure and monitoring your own physical state for any symptoms. But then you must be concerned about your family, your friends, and also society. This is a situation where the impulse and the ethos of worrying about your fellow persons—being your brother’s keeper—is imperative.

The epidemic has been successfully managed in some countries, like Singapore and China, which, once they got on top of it, were able to limit contagion in a very dramatic way. But these are authoritarian governments. The United States doesn’t work that way, which is what makes appealing to the principle of caring for others so crucial. You can protect yourself, but if other people aren’t also protected, it may not matter. You have to worry not just about yourself but about everyone else.

When it comes to stress management, I recommend not catastrophizing or watching the news media 24/7. Distract yourself with other work or recreational activities. Reach out and communicate—virtually, of course—with friends, family, and healthcare providers as needed. Staying in touch acts not just as a diversion but also as an outlet for assuaging your feelings, your sense of being in this alone, feeling isolated.

There are also cognitive reframing mechanisms you can employ. Consider that although this is bad, some countries have already gone through it. And we’ll get through it too. You’ll understandably ask yourself what it would mean if you were to be exposed. In most cases you can say, “I’m going to have the flu and symptoms that are not going to be pleasant, but I’ve had the flu or serious sickness before.”

Remember that there are already antiretroviral treatments being tested in clinical trials and showing efficacy. It’s good to know that before this pandemic ends, some of these treatments will probably be clinically applied, mostly to those who are severely affected and in intensive care.

Diagnose yourself. Monitor your state. Determine whether the stress is really having an impact on you. Is it affecting your sleep, appetite, concentration, mood? And if you do have a preexisting psychiatric condition, don’t feel afraid to reach out to your mental health provider. Understand that you’re going to be anxious, which may aggravate your symptoms and require an adjustment in your treatment. That’s okay. It’s to be expected and your provider should be available to help you.

Controlling this outbreak via the same epidemiologic infectious disease prevention guidance that works in authoritarian societies is not going to be applicable here because of the liberties that we experience in American society. What will determine our success is the belief that we’re in this together, that we’re going to help each other. We should be proud of that, as it shows how Americans and people around the world stand up in situations like this.

Let’s also note that even though everybody is affected and undergoing previously unimaginable levels of anticipated stress and dislocation, it’s the healthcare providers who are really on the frontlines. They’re under tremendous pressure to continue to perform heroically, at great risk to themselves. They deserve a real debt of gratitude.

We will get through this, but as we do, it will not end until we’ve undergone an extreme test of our character. I certainly hope and trust that we will be up to it.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Lieberman is chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University. He is a former president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Disclosure: Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Clintara; Intracellular Therapies. Received research grant from Alkermes; Biomarin; EnVivo/Forum; Genentech; Novartis/Novation; Sunovion. Patent: Repligen.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance on management of acute CVD during COVID-19

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA issues EUA allowing hydroxychloroquine sulfate, chloroquine phosphate treatment in COVID-19

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

Flu activity measures continue COVID-19–related divergence

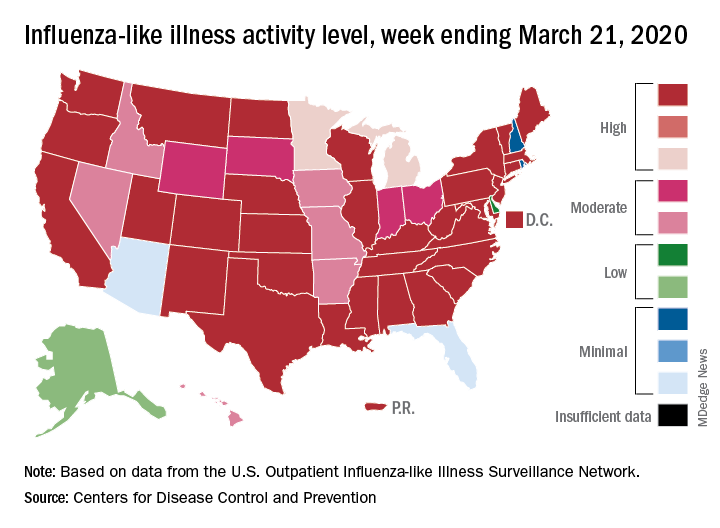

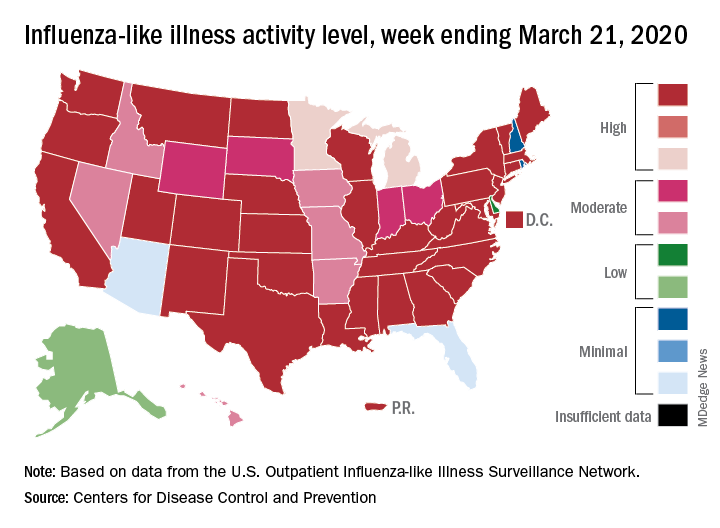

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

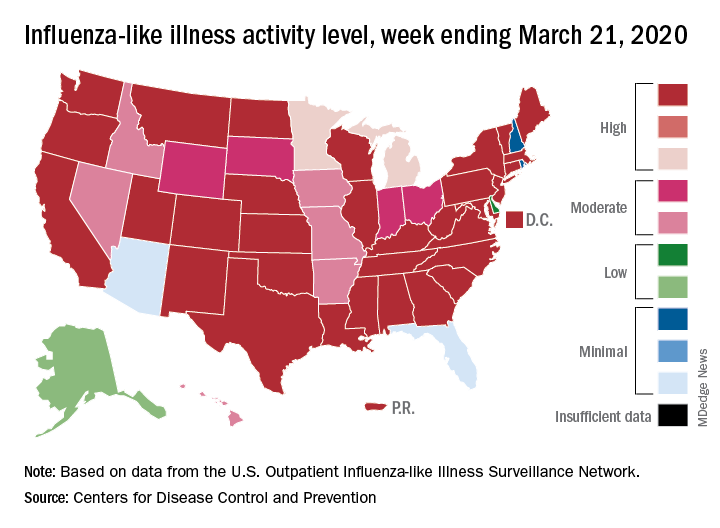

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

The 2019-2020 flu paradox continues in the United States: Fewer respiratory samples are testing positive for influenza, but more people are seeking care for respiratory symptoms because of COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

compared with 14.9% the week before, but outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) rose from 5.6% of all visits to 6.2% for third week of March, the CDC’s influenza division reported.

The CDC defines ILI as “fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza.” The outpatient ILI visit rate needs to get below the national baseline of 2.4% for the CDC to call the end of the 2019-2020 flu season.

This week’s map shows that fewer states are at the highest level of ILI activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale: 33 states plus Puerto Rico for the week ending March 21, compared with 35 and Puerto Rico the previous week. The number of states at level 10 had risen the two previous weeks, CDC data show.

“Influenza severity indicators remain moderate to low overall, but hospitalization rates differ by age group, with high rates among children and young adults,” the influenza division said.

Overall mortality also has not been high, but 155 children have died from the flu so far in 2019-2020, which is more than any season since the 2009 pandemic, the CDC noted.

Solitary Warty Mucosal Lesion on the Hard Palate

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

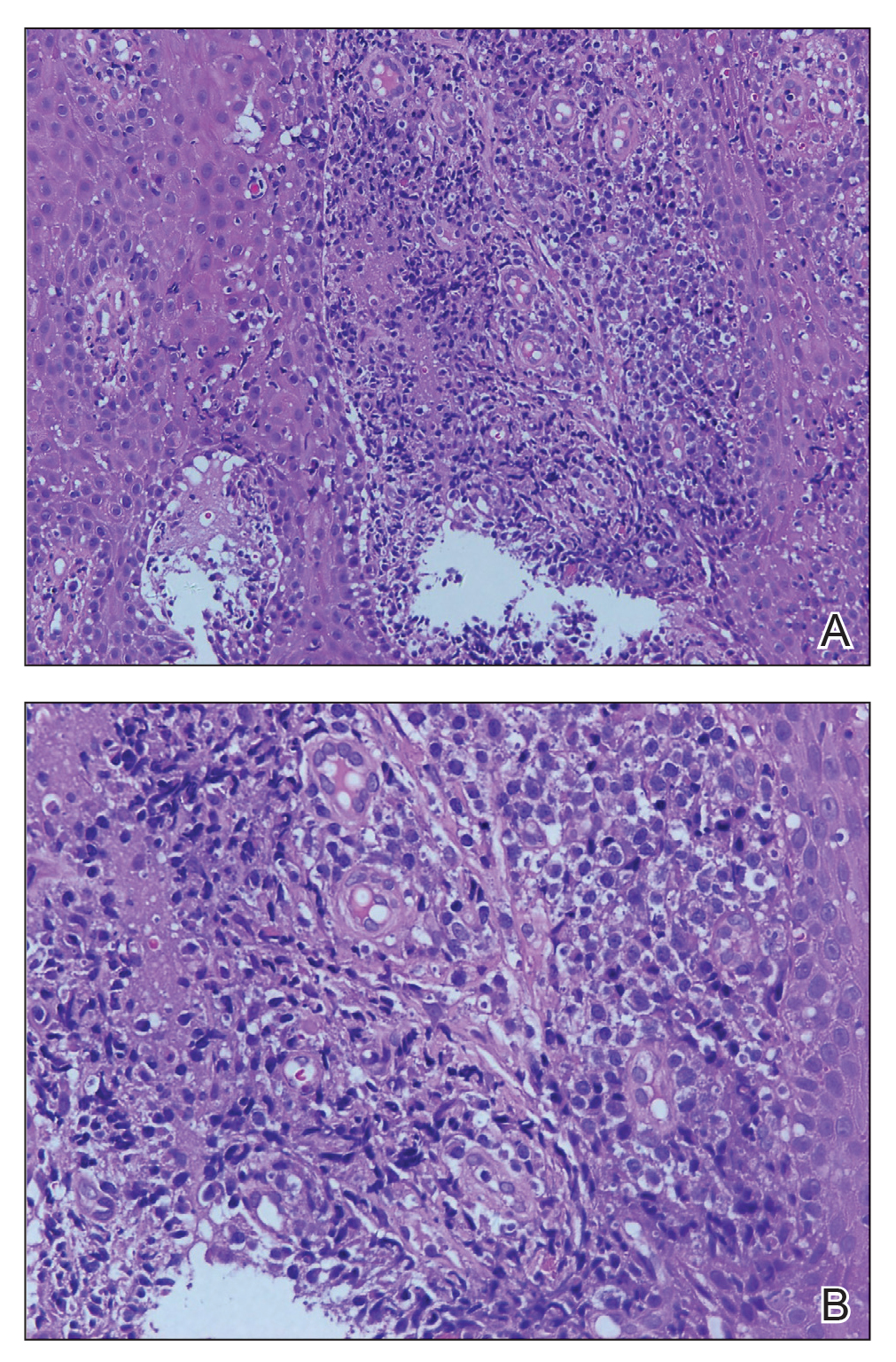

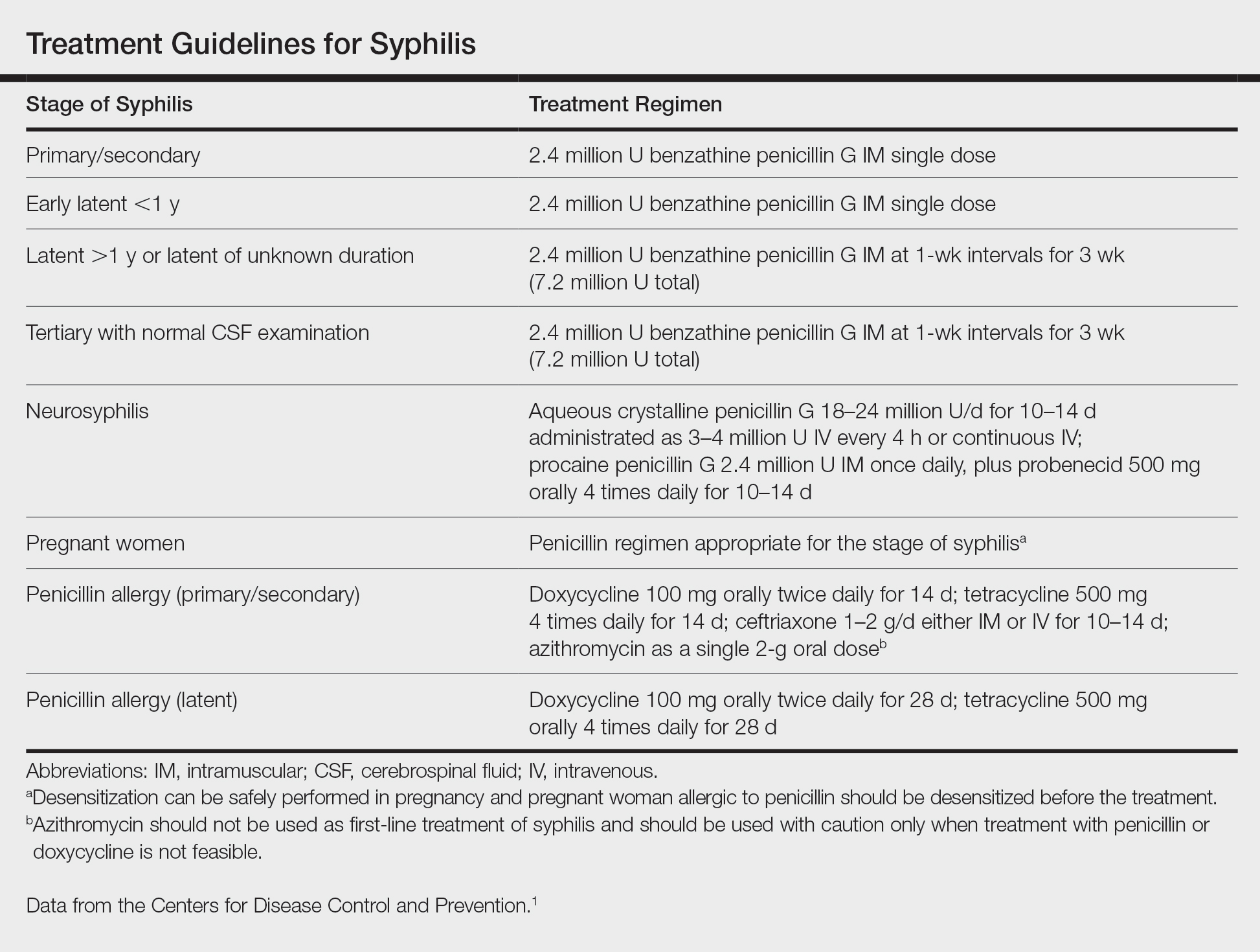

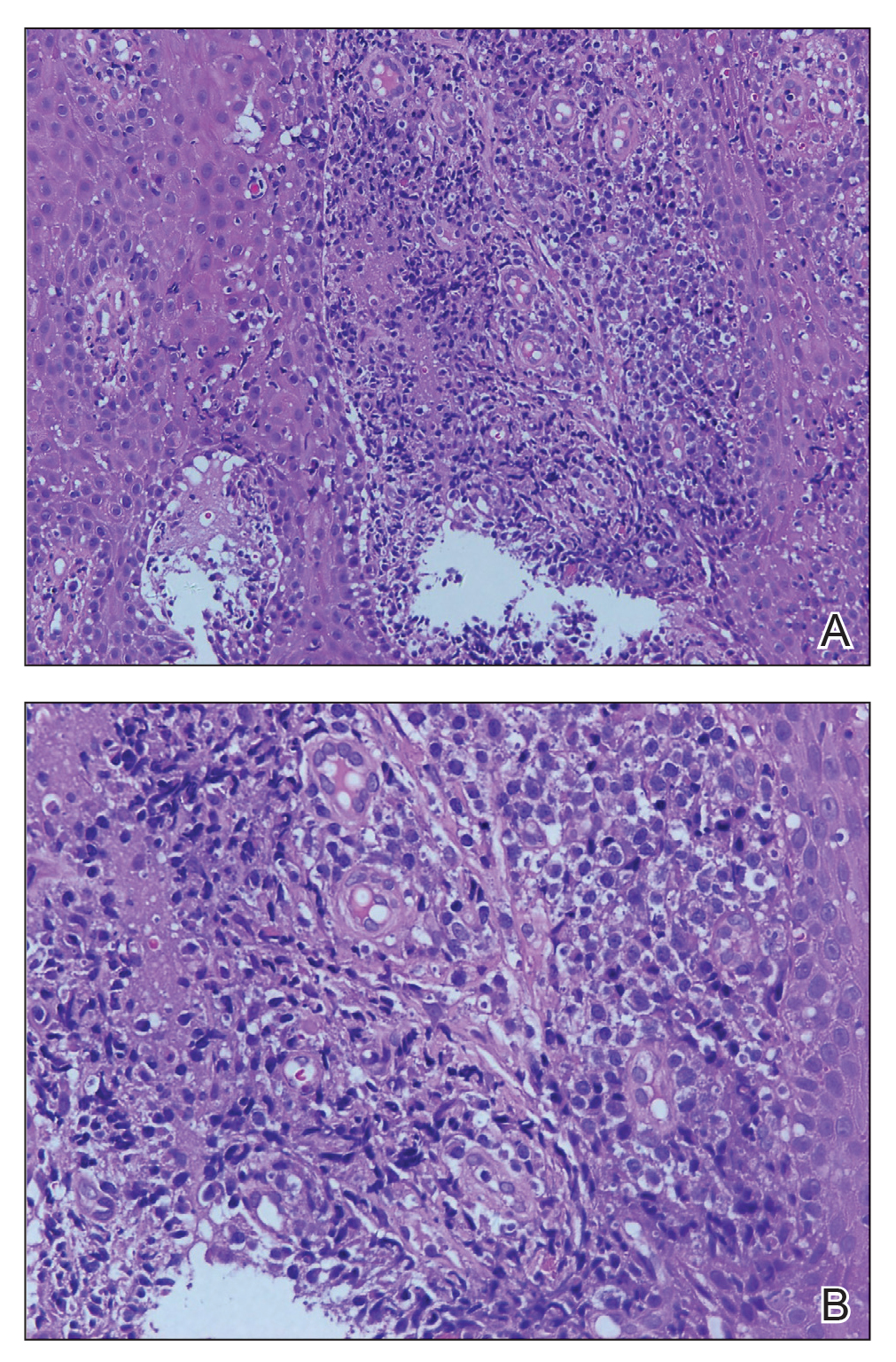

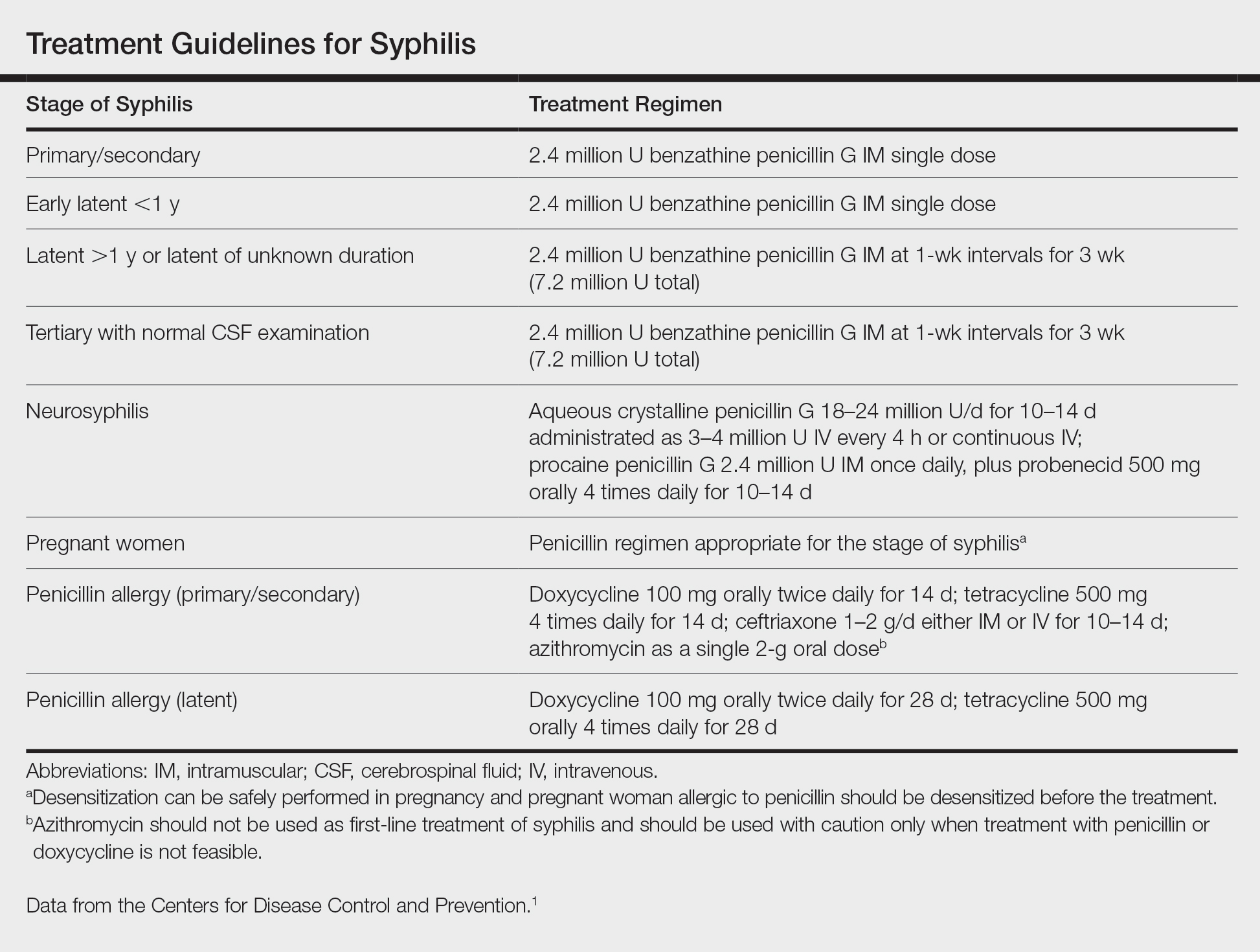

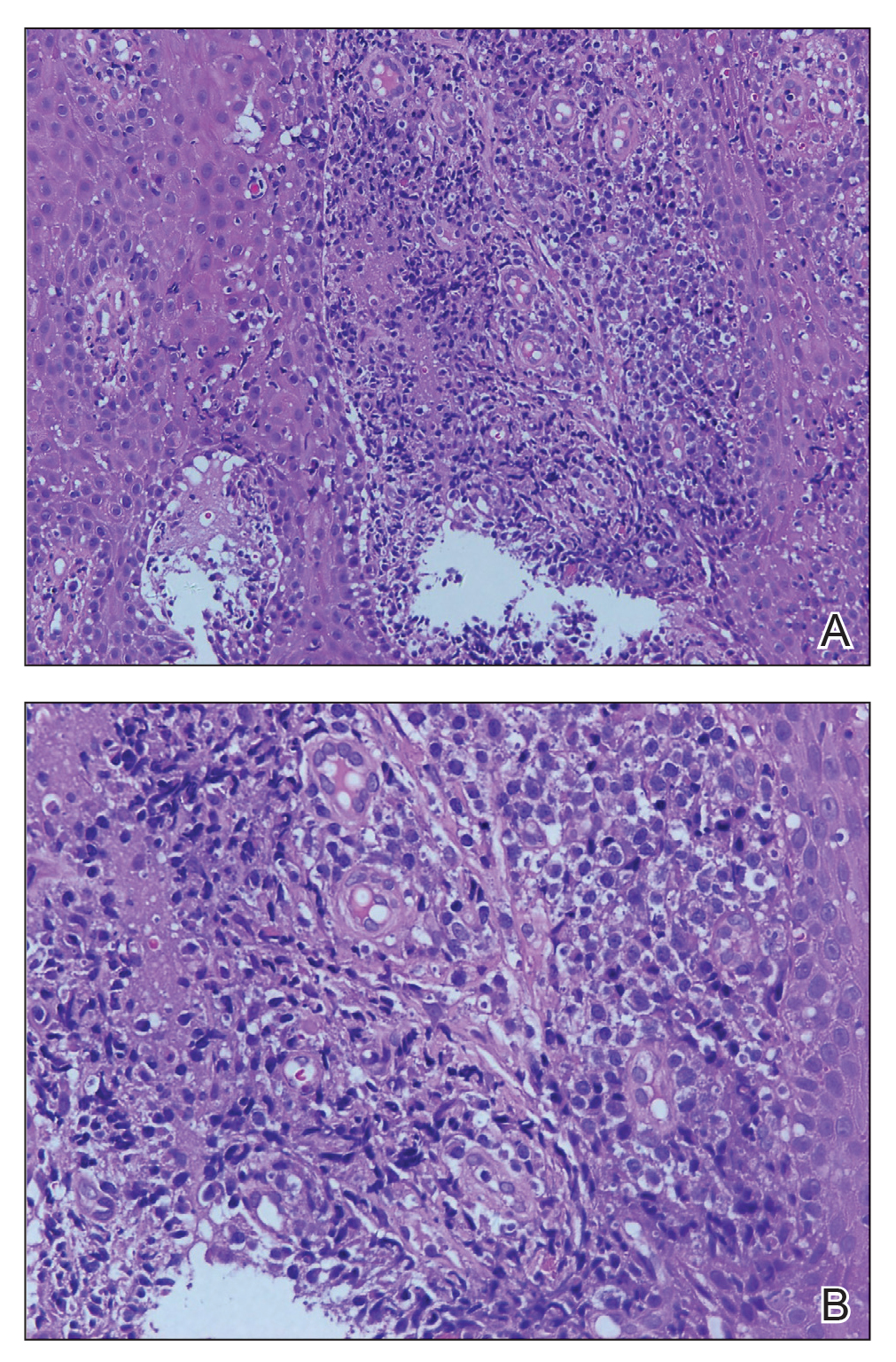

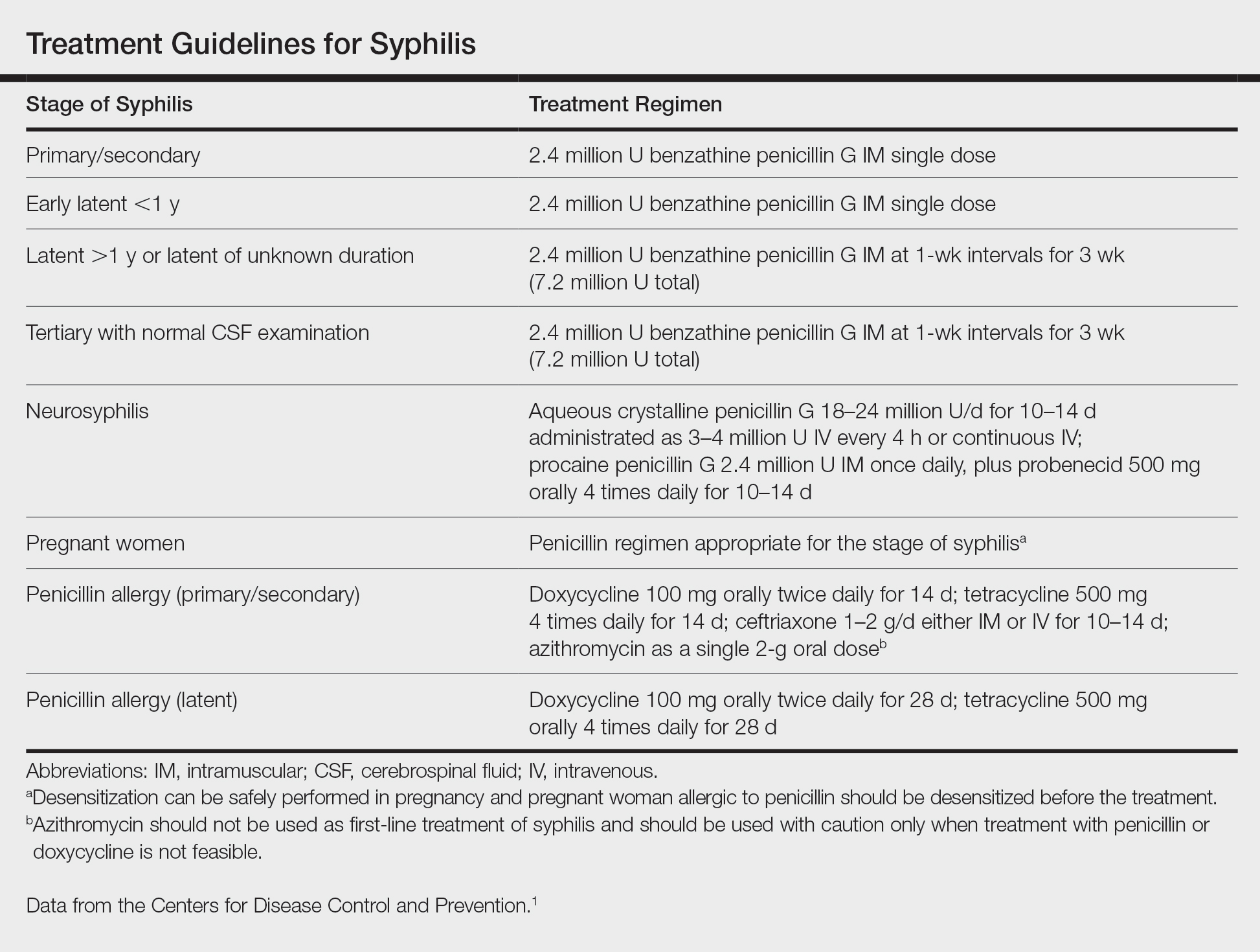

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

A 50-year-old Chinese woman presented with a painless, well-demarcated, nontender, elevated, flat-topped verrucous plaque on the hard palate of 1 month's duration. The lesion measured 2 cm in diameter. The patient reported no other dermatologic or systemic concerns, and no other skin or genital lesions were observed.

Critical care and COVID-19: Dr. Matt Aldrich

Matt Aldrich, MD, is an anesthesiologist and medical director of critical care at UCSF Health in San Francisco. Robert Wachter, MD,MHM, spoke with him about critical care issues in COVID-19, including clinical presentation, PPE in the ICU, whether the health system has enough ventilators for a surge, and ethical dilemmas that ICUs may face during the pandemic.

Matt Aldrich, MD, is an anesthesiologist and medical director of critical care at UCSF Health in San Francisco. Robert Wachter, MD,MHM, spoke with him about critical care issues in COVID-19, including clinical presentation, PPE in the ICU, whether the health system has enough ventilators for a surge, and ethical dilemmas that ICUs may face during the pandemic.

Matt Aldrich, MD, is an anesthesiologist and medical director of critical care at UCSF Health in San Francisco. Robert Wachter, MD,MHM, spoke with him about critical care issues in COVID-19, including clinical presentation, PPE in the ICU, whether the health system has enough ventilators for a surge, and ethical dilemmas that ICUs may face during the pandemic.

Before the COVID-19 surge hits your facility, take steps to boost capacity

, according to a physician leader and a health workforce expert.

Polly Pittman, PhD, is hearing a lot of concern among health care workers that it’s difficult to find definitive and accurate information about how best to protect themselves and their families, she said during a webinar by the Alliance for Health Policy titled Health System Capacity: Protecting Frontline Health Workers. “The knowledge base is evolving very quickly,” said Dr. Pittman, Fitzhugh Mullan Professor of Health Workforce Equity at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington.

Stephen Parodi, MD, agreed that effective communication is job one in the health care workplace during the crisis. “I can’t stress enough ... that communications are paramount and you can’t overcommunicate,” said Dr. Parodi, executive vice president of external affairs, communications, and brand at the Permanente Federation and associate executive director of the Permanente Medical Group, Vallejo, Calif.

“We’re in a situation of confusion and improvisation right now,” regarding protection of health care workers, said Dr. Pittman. The potential exists for “a downward spiral where you have the lack of training, the shortages in terms of protective gear, weakening of guidelines, and confusion regarding guidelines at federal level, creating a potential cascade” that may result in “moral distress and fatigue. ... That’s not occurring now, but that’s the danger” unless the personal protective equipment (PPE) situation is adequately addressed very soon, she said.

Dr. Pittman also pointed out the concerns that many of the 18 million U.S. health care workers have for their families should they themselves fall ill or transmit coronavirus to family members. “The danger exists of a mass exodus. People don’t have to show up at work, and they won’t show up at work if they don’t feel supported and safe.”

Dr. Parodi said that the Permanente organization is on a better footing than many workplaces. “We actually had an early experience because of the work that we did to support the Diamond Princess cruise ship evacuees from Yokahama in February.” That ship was quarantined upon arrival in Yokahama on Feb. 3 because a passenger had a confirmed test for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a quarter of the 428 Americans on board subsequently tested positive. Most of them were evacuated to California or Texas. “That actually gave us the experience for providing care within the hospital setting – and also for containment strategies,” he said.

“We quickly understood that we needed to move to a mitigation strategy,” said Dr. Parodi. Use of PPE has been “tailored for how the virus is spread.” In the absence of the risk of aerosol transmission from certain procedures, health care workers use gowns, gloves, surgical masks, and goggles.

Because of anticipated “supply chain shortfalls,” Dr. Parodi said that his organization implemented Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for reuse and extended use of N95 respirators early on. “Even if you’re not in a locale that’s been hit, you need to be on wartime footing for preserving PPE.”

Telehealth, said Dr. Parodi, has been implemented “in a huge way” throughout the Permanente system. “We have reduced primary care visits by 90% in the past week, and also subspecialty visits by 50%. … A large amount of the workforce can work from home. We turned off elective surgeries more than a week ago to reduce the number of patients who are requiring intensive care.” Making these changes means the organization is more prepared now for a surge they expect in the coming weeks.

Dr. Pittman voiced an opinion widely shared by those who are implementing large-scale telehealth efforts “We’re going to learn a lot. Many of the traditional doctor-patient visits can be done by telemedicine in the future.”

Knowledge about local trends in infection rates is key to preparedness. “We’ve ramped up testing, to understand what’s happening in the community,” said Dr. Parodi, noting that test turnaround time is currently running 8-24 hours. Tightening up this window can free up resources when an admitted patient’s test is negative.

Still, some national projections forecast a need for hospital beds at two to three times current capacity – or even more, said Dr. Parodi.

He noted that Permanente is “working hand in glove with state authorities throughout the country.” Efforts include establishing alternative sites for assessment and testing, as well as opening up closed hospitals and working with the National Guard and the Department of Defense to prepare mobile hospital units that can be deployed in areas with peak infection rates. “Having all of those options available to us is critically important,” he said.

To mitigate potential provider shortages, Dr. Pittman said, “All members of the care team could potentially do more” than their current licenses allow. Expanding the scope of practice for pharmacists, clinical laboratory staff, licensed practical nurses, and medical assistants can help with efficient care delivery.

Other measures include expedited licensing for near-graduates and nonpracticing foreign medical graduates, as well as relicensing for retired health care personnel and those who are not currently working directly with patients, she said.

Getting these things done “requires leadership on behalf of the licensing bodies,” as well as coordination with state regulatory authorities, Dr. Pittman pointed out.

Dr. Parodi called for state and federal governments to implement emergency declarations that suspend some existing health codes to achieve repurposing of staff. Getting these measures in place now will allow facilities “to be able to provide that in-time training now before the surge occurs. ... We are actively developing plans knowing that there’s going to be a need for more critical care.”

The game plan at Permanente, he said, is to repurpose critical care physicians to provide consultations to multiple hospitalists who are providing the bulk of frontline care. At the same time, they plan to repurpose other specialists to backfill the hospitalists, and to repurpose family medicine physicians to supplement staff in emergency departments and other frontline intake areas.

All the organizational measures being taken won’t be in vain if they increase preparedness for the long battle ahead, he said. “We need to double down on the work. ... We need to continue social distancing, and we’ve got to ramp up testing. Until we do that we have to hold the line on basic public health measures.”